Abstract

Childhood health disparities by race have been found. Neighborhood disadvantage, which may result from racism, may impact outcomes. The aim of the study is to describe the distribution of mental health (MH) and developmental disabilities (DD) diagnosis across Child Opportunity Index (COI) levels by race/ethnicity. A cross-sectional study using 2022 outpatient visit data for children < 18 years living in the Louisville Metropolitan Area (n = 115,738) was conducted. Multivariable logistic regression analyses examined the association between diagnoses and COI levels, controlling for sex and age. Almost 18,000 children (15.5%) had a MH or DD (7,905 [6.8%]) diagnosis. In each COI level, the prevalence of MH diagnosis was lower for non-Hispanic (N–H) Black than for N–H White children. In adjusted analyses, there were no significant associations between diagnoses and COI for non-White children for MH or DD diagnoses. The odds of receiving a MH [OR: 1.74 (95% CI: 1.62, 1.87)] and DD [OR: 1.69 (95% CI: 1.51, 1.88)] diagnosis were higher among N–H White children living in Very Low compared to Very High COI areas. Current findings suggest that COI does not explain disparities in diagnosis for non-White children. More research is needed to identify potential multi-level drivers such as other forms of racism. Identifying programs, policies, and interventions to reduce childhood poverty and link children and families to affordable, family-centered, quality community mental and physical health resources is needed to ensure that families can build trusting relationships with the providers while minimizing stigma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

While much has been written about child health and developmental disparities associated with poverty and/or race/ethnicity, much remains unknown about the mechanisms through which these disparities occur or the role that racism plays as a social determinant of health [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The concept of race and, thus, racism in the United States emerged as the nation emerged [7]. The European settlers were dependent on enslaved Africans to maintain the economic well-being [7]. In order to maintain their power differential, they created legal categories of people, primarily Black and Native American, who were deemed to be inferior in many ways to those who were white [7]. Although now discredited, scientific theories and studies were developed on the premise that race was a biological construct that was fixed in nature at birth [7]. From these basic assumptions, systems of white supremacy and privilege emerged while non-White groups, especially those of African descent were oppressed [7]. The literature refers to different types of discrimination and racism, but structural racism is most often studied in relation to adult and child health outcomes [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Structural racism refers to inequalities in multiple overlapping societal systems such as housing, education, employment, distribution of resources, health care access and quality, criminal justice, salaries, etc. [5, 6, 8,9,10]. Neighborhood quality or residential segregation has been one area that has been shown to be associated with disparities in mortality and morbidity across multiple systems or disorders [9, 11,12,13,14].

Previous work has focused on maternal, child, and environmental factors at the individual level [2, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Recent literature suggests that the effects of racism on health and developmental outcomes can best be understood by examining a broader range of influences including structural racism and discrimination (SRD) [5, 8, 25,26,27].

Neighborhood and environmental quality differences have a long history in the U.S. that were exacerbated by the practice of “redlining” [14, 28,29,30]. “Redlining” was a practice that was first documented in the U.S. around 1930 and continued through 1968 [30]. The practice originated to inform loan officers, appraisers, and real estate professionals of the risk of providing loans to individuals in certain geographic areas [30]. Maps were created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in major cities throughout the country [30]. The HOLC sent workers out to rank the neighborhoods “based on criteria related to the age and condition of housing, transportation access, closeness to amenities such as parks or disamenities like polluting industries, the economic class and employment status of residents, and their ethnic and racial composition” [30]. Once the assessment was completed, neighborhoods were color-coded on maps such that green was the “most desirable;” blue was “still desirable;” yellow was “definitely declining;” and red was “hazardous.” Thus, the term “redlining” emerged [29, 30]. The significance of this practice is that individuals in these areas were unable to get mortgage or small business loans, which resulted in the areas remaining poor, underserved, and largely occupied by those of minority status [30]. [30] These practices represent a systemic level of structural racism creating segregated and impoverished communities by restricting loans to homeowners and businesses based on the HOLC grading classifications of neighborhoods [14, 28, 30, 31]. Currently, many of the “redlined” areas remain economically and racially segregated [30, 32]. In a recent study including cities for which HOLC maps were available, Louisville, Kentucky was one of five cities that remain highly segregated and still have the lowest increase in income and housing values among previously “redlined” areas [30].

To date, two studies specifically mapped birth outcomes to areas of historic redlining [14, 31]. Two others used a similar construct of structural racism using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) [33, 34]. Bishop-Royse et al. found that infant mortality rates in Chicago were related to structural racism as measured by the ICE after controlling for socio-economic marginalization, hardship, family support, and healthcare access [33]. Similarly, Chambers et al. found preterm birth and infant mortality rates in California were related to extreme income, race, and income + race concentrations and that Black women were more likely to live in zip codes with greater extreme income concentrations and moderate extreme race + income concentrations [34].

Health disparities have been associated with race and ethnicity [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], but little is known about the effects of racism [3, 45]. Williams and Mohammed [4] warn that more research is needed to ensure that inaccurate conclusions are not drawn for the relationship between race and health disparities. Conclusions from some studies that present racial/ethnic differences in outcomes across multiple domains have led to the misconception that the disparities have a biological basis due to race. However, it is important to note that race is a social construct. Research is needed to identify the root causes for these disparities [10, 11, 46, 47].

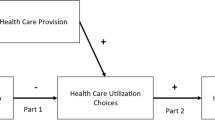

The Child Opportunity Index (COI) [48, 49] is another measure of neighborhood quality, which uses 29 indicators from census tract data to measure neighborhood resources and conditions relevant to children’s health and development [49]. Indicators are ranked from very low opportunity to very high opportunity (5 levels) for 3 subscales (education, health environment, and social and economic) as well as an overall score. Family home addresses are used to link to locally or nationally normed COI datasets. Based on previous literature, we hypothesized that low levels of neighborhood child opportunity would be associated with higher levels of risk for adverse child health outcomes.

Recent literature demonstrates the need to elucidate the effects of racism and its multiple levels on specific health outcomes [4, 9, 45]. Two recent papers found that present day risk for preterm birth was associated with “redlining” in New York City [14] even after controlling for maternal covariates such as age, educational attainment, and measures of current poverty, and was associated with multiple adverse birth outcomes in California [31]. More data are needed to examine the effects of environmental adversity on pregnant and parenting women as well as child outcomes beyond birth. The COI captures factors related to neighborhood disadvantage that are often related to racist practices and policies. Previous studies have found racial differences in the rates of and treatment for mental health disorders in adults and children [50,51,52] and developmental disabilities [35, 50, 53,54,55,56]. The purpose of the current study is to describe rates of mental health and developmental disability diagnoses in children by COI levels and race/ethnicity and to examine their associations after controlling for age and sex. As described above, data are not available that examine the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on children beyond infancy. Knowing that neighborhood quality is rooted in structural racism practices, we hypothesize that COI levels will be associated with increased mental health and developmental disability diagnoses in children.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

In this cross-sectional analysis, we retrieved the sample cohort from the electronic health record for outpatient visits, which included emergency department and primary care visits, in 2022 from a large children’s health system in an urban setting (n = 181,887). Unique children < 18 years of age with valid addresses living in the KY-IN Louisville Metropolitan Statistical Area (CBSA 31140) were included (n = 115,738).

The cohort (n = 115,738) was predominantly non-Hispanic White (57.3%) followed by non-Hispanic Black (25.2%) with the remainder being Hispanic (9.3%), Other race/ethnicity (4.7%), or unknown (3.7%). The local population demographic is 66% non-Hispanic White, 22% non-Hispanic Black, 6% Hispanic, and 6% other races/ethnicities. Almost 18,000 children (15.5%) had a MH diagnosis and 7,905 (6.8%) had a DD (Table 1).

The primary independent variable was the most recent version of the overall metro-normed Child Opportunity Index 2.0 (COI 2.0) levels (from “very low” to “very high”) updated in 2015. The patients’ home addresses were geocoded and linked by census tract in the KY-IN Louisville Metropolitan Statistical Area (USA). Our outcomes were mental health diagnoses and developmental disorder diagnoses (See Online Resource Table S1 for diagnosis codes.). Diagnoses were retrieved from encounter diagnoses, past medical histories, problem lists, professional charge transaction diagnoses, and final coded diagnoses. If the child had multiple visits or multiple diagnoses, they were only included once for each category. Developmental diagnoses and substance related disorders were excluded from mental health diagnoses and mental health diagnoses and substance related disorders were excluded from developmental disability diagnoses. Children under 2 years of age were excluded from the mental health disorder diagnosis group but not from the developmental disability diagnosis group. Substance use disorders are, generally, reported in the literature separate from other mental health disorders although there is significant co-morbidity [57,58,59]. Additionally, substance use disorders are tracked for children 12–17 years of age only in national databases [60]. Race and ethnicity were extracted from the electronic medical record, which, at our institution, is not standardized. The variable combines race and ethnicity and allows only one option. Multivariable logistic regression models were performed to examine the association between the specific diagnosis groups and COI levels, controlling for sex and age.

The sample was first stratified by race, and a univariate analysis was conducted among each race group to determine whether the binary outcome (mental health: yes/no; developmental disorder: yes/no) was associated with the predictor (COI levels), age (continuous variable in years), and sex (male/female). In order to identify potential confounding variables or effect modifiers, the Wald Chi-Square p-value of univariate logistic regression was employed using the SAS's PROC LOGISTIC procedure. The independent variable was initially assessed to determine whether it was an effect modifier with the interaction term achieving bivariate significance at p < 0.05. If there was no significant interaction term, we considered it a confounder and, thus, we included age and sex in the multivariable model. Patients with missing data were not included in the logistic regression analysis but were included in Table 1. Missing data was minimal and missing at random.

The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Louisville. The study was also approved by the Research Office at the Norton Children’s Hospital. A data-sharing agreement is in place through an affiliation agreement between the two institutions. Data were stored and analyzed on a secure HIPAA-compliant network.

Results

Non-Hispanic White children make up 28.9% of the children living in the Very Low Opportunity level neighborhoods compared to 77.5% living in the Very High Opportunity level neighborhoods (Table 1). In contrast, 53.8% of the non-Hispanic (N–H) Black children live in Very Low Opportunity level neighborhoods compared to 7.6% living in the Very High Opportunity level neighborhoods.

Figure 1 depicts the overall prevalence rates of MH diagnoses & DD diagnoses by COI levels. In Fig. 2, the prevalence rates were displayed for N–H Black and N–H White children as they constituted the two largest groups in our sample. MH diagnosis was lower for N–H Black children than for N–H White children in each COI level. DD were diagnosed slightly less for N–H White children than N–H Black children.

In multivariable logistic regression, COI was associated with MH diagnosis for N–H White children only (Table 2) with an adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of receiving a MH diagnosis for children living in a Very Low compared to a Very High COI area of 1.74 (1.62, 1.87; Table 2). Similarly, for N–H White children only, the adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of receiving a DD diagnosis for children living in a Very Low compared to a Very High COI area was 1.69 (1.51, 1.88; Table 3). There were no significant associations between diagnoses and COI for children who were N–H Black, Hispanic, or Other race/ethnicity for MH or DD diagnoses.

Across all races/ethnicities except “other,” males had a higher adjusted odds ratio of receiving a mental health diagnosis and older children across all racial/ethnic groups had a higher adjusted odds ratio of receiving a mental health diagnosis. Similarly, males had a higher odds ratio of receiving a developmental disability diagnosis across all racial/ethnic groups and younger children were more likely to get the diagnosis. For both diagnostic categories, Hispanic male children had the highest adjusted odds ratio of receiving a diagnosis.

Discussion

The current findings present new information on the relationships among COI, race/ethnicity, and mental health and developmental disability diagnoses in an urban area in a southern state in the U.S. Contrary to our expectations, neighborhood disadvantage did not explain disparities in diagnosis for non-White children. More research is needed to determine the complex array of factors beyond neighborhood disadvantage that are operating to create differences for children of color. Our findings suggest that there are factors that impact the prevalence of or the diagnosis of mental health and developmental disorders across all levels of neighborhood quality.

As expected from previous literature, we also found that Black children are disproportionately represented in the very low opportunities neighborhoods compared to non-Hispanic White children (54% vs 29%, respectively). Likewise, White children make up 78% of the children living in very high opportunity neighborhoods, while only 8% are Black, 4% are Hispanic, 6% are listed as other, and 5% are of unknown race/ethnicity.

The effects of toxic stress on parents and children have been studied for more than a decade [60,61,62,64]. More recently, researchers are looking at chronic and cumulative stress in relation to health equity and differences in child development [64,65,66,67,69]. Neighborhood disadvantage, which is related to poverty, is only one stressor families may face. Since poverty and neighborhood disadvantage are more often associated with being of minority status, more attention is needed on the effects of racism-related cumulative stressors [46, 68,69,71].

One explanation for increased rates of developmental disabilities in Black children may be prenatal exposure to cumulative stressors, especially stressors caused by structural racism and discrimination (SRD) at multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, community, and societal) [26]. Similarly, exposure of both caregivers and children to racism-related cumulative stress may increase the prevalence of mental health disorders in children [71]. Research has shown that stress is associated with adverse outcomes for adults and children [71,72,74]. However, less is known about stress that is specifically caused by racism and discrimination [75]. Conversely, lower rates of mental health diagnoses in minoritized groups may result from caregivers’ lack of help-seeking behavior due to fear of stigmatization, lack of access to care, or provider bias in diagnosing [75,76,77,78,79,80,82].

More research is needed to identify root causes such as provider bias, caregivers’ medical mistrust, and other potential forms of interpersonal and structural racism. Additionally, the identification of protective factors may inform interventions. It is not enough to identify an issue, but the information must be used to inform interventions to improve health equity. Some protective factors that have previously been studied include racial socialization [82,83,84,86], racial identity [83, 86,87,89], parental social support [90], neighborhood cohesion [89,90,91,93], parenting self-efficacy [90, 94, 95], and spirituality/religiosity [96,97,98]. Developing interventions to promote these protective factors has potential to, at least partially, mitigate the effects of SRD. Additionally, identifying ways to minimize provider bias and enhance parent and child trust in the health care system has potential to reduce inequities. Strengthening community and school resources has the potential to increase access and minimize stigma [99, 100]. Health information exchanges could be strengthened by expanding the system to include school and community-based diagnosis and treatment [101], which could be used to provide case management and service utilization. Expanded public and private insurance coverage for family-centered mental health promotion interventions is needed [102, 103].

Although the study contributes new information to the literature, there are limitations. First, the collection of race and ethnicity within the electronic medical record is not ideal. The methods are not standardized, are not consistently parent-reported, and include a combined race/ethnicity variable with no option for selecting more than one group. Second, the COI does not include access to health care, which could also influence the receipt of a diagnosis. Third, data were collected from the EHR only, which would exclude diagnoses that may have been made at community mental health agencies or through the school system which may not be accessed equally among children from all levels of COI. However, the use of the problem list in addition to the visit diagnosis may have captured this. Fourth, the data for these analyses came from a single healthcare system, therefore, generalizability to other locations may be limited. Lastly, COI measures neighborhood quality from census data, which does not capture individual-level factors. Relatedly, measures of multi-level exposures to SRD are emergent [102,103,106]. More research is needed to examine the effects of the complex array of factors that may be associated with differences in the prevalence and/or diagnosis of mental health and developmental disabilities in childhood. The cumulative and intergenerational effects of SRD on health disparities have yet to be fully captured [106].

Despite the limitations, the study highlights important findings. If neighborhood differences do not explain racial/ethnic differences in diagnosis, what are the root causes? The effects of racism-related cumulative stressors on parents and children seem like a promising direction. Additionally, the study of protective factors to support positive outcomes in the face of such stressors is critical. Lastly, identifying programs, policies, and interventions to reduce childhood poverty and link children and families to affordable, quality community mental and physical health resources is needed. These programs must be developed with input from the communities they serve to ensure that care is provided in such a way that the families can build trusting relationships with the providers and that stigma toward the parents and the children can be avoided.

Summary

Neighborhood disadvantage has its roots in racist policies and practices and has been identified as a potential source of disparities in adult health and pregnancy outcomes. The current study aimed to identify patterns of childhood diagnosis of mental health and developmental disabilities by race/ethnicity and neighborhood characteristics as measured by the Child Opportunity Index (COI). COI was related to the rate of diagnosis for non-Hispanic White children only. Based on the findings, it appears that non-White children across COI levels may have other factors contributing to racial/ethnic differences in diagnosis rates. More research is needed to better understand the complex array of factors responsible for the disparate outcomes such as racism-related cumulative stressors.

Data Availability

Data are not publicly available due to a data use agreement. A de-identified dataset may be available upon request.

References

Liu SR, Kia-Keating M, Nylund-Gibson K (2018) Patterns of adversity and pathways to health among White, Black, and Latinx youth. Child Abuse Negl 86:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.007

Marcus Jenkins JV, Woolley DP, Hooper SR, De Bellis MD (2013) Direct and indirect effects of brain volume, socioeconomic status and family stress on child IQ. J Child Adolesc Behav 1(2):29. https://doi.org/10.4172/2375-4494.1000107

Whiteside-Mansell L, McKelvey L, Saccente J, Selig JP (2019) Adverse childhood experiences of urban and rural preschool children in poverty. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Electronic Resource] 16(14):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142623

Williams DR, Mohammed SA (2009) Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 32(1):20–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0

Williams DR, Mohammed SA (2013) Racism and health I: pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci 57(8):1152–1173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487340

Williams DR, Mohammed SA (2013) Racism and health II: a needed research agenda for effective interventions [Article]. Am Behav Sci 57(8):1200–1226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487341

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT (2017) Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet 389(10077):1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

Williams DR, Cooper LA (2019) Reducing racial inequities in health: Using what we already know to take action. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Electronic Resource] 16(4):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040606

Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA (2019) Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health 40:105–125. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750

Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB (1997) Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol 2(3):335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305

King CJ, Buckley BO, Maheshwari R, Griffith DM (2022) Race, place, and structural racism: a review of health and history in Washington D.C. Health Affairs 41(2):273–280. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01805

Krager MK, Puls HT, Bettenhausen JL, Hall M, Thurm C, Plencner LM, Markham JL, Noelke C, Beck AF (2021) The Child opportunity index 2.0 and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-032755

Krieger N (2000) Epidemiology, racism, and health: the case of low birth weight. Epidemiology 11(3):237–239

Krieger N, Van Wye G, Huynh M, Waterman PD, Maduro G, Li W, Gwynn RC, Barbot O, Bassett MT (2020) Structural racism, historical redlining, and risk of preterm birth in New York City, 2013–2017. Am J Public Health 110(7):1046–1053. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305656

Poehlmann J, Fiese BH (2001) Parent-infant interaction as a mediator of the relation between neonatal risk status and 12-month cognitive development. Infant Behav Dev 24:171–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-6383(01)00073-X

Polanska K, Krol A, Merecz-Kot D, Jurewicz J, Makowiec-Dabrowska T, Chiarotti F, Calamandrei G, Hanke W (2017) Maternal stress during pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes of children during the first 2 years of life. J Paediatr Child Health 53(3):263–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13422

Ramey CT, Campbell FA (1991) Poverty, early childhood education, and academic competence: The Abecedarian experiment. In: Huston A (ed) Children reared in poverty. Cambridge University Press, pp 190–221

Robinson JB, Burns BM, Davis DW (2009) Maternal scaffolding and attention regulation in children living in poverty. J Appl Dev Psychol 30:82–91

Shah R, Sobotka SA, Chen YF, Msall ME (2015) Positive parenting practices, health disparities, and developmental progress. Pediatrics 136(2):318–326. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3390

Treat AE, Sheffield Morris A, Hays-Grudo J, Williamson AC (2020) The impact of positive parenting behaviors and maternal depression on the features of young children’s home language environments. J Child Lang 47(2):382–400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030500091900062X

Ward KP, Lee SJ (2020) Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress, responsiveness, and child wellbeing among low-income families. Children Youth Serv Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105218

Weisleder A, Cates CB, Harding JF, Johnson SB, Canfield CF, Seery AM, Raak CD, Alonso A, Dreyer BP, Mendelsohn AL (2019) Links between shared reading and play, parent psychosocial functioning, and child behavior: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr 213:187-195.e181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.06.037

Zeng S, Corr CP, O’Grady C, Guan Y (2019) Adverse childhood experiences and preschool suspension expulsion: a population study. Child Abuse Negl 97:104149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104149

Zvara, B. J., Mills-Koonce, W. R., Garrett-Peters, P., Wagner, N. J., Vernon-Feagans, L., Cox, M., & Family Life Project Key, C. (2014). The mediating role of parenting in the associations between household chaos and children's representations of family dysfunction. Attachment & Human Development, 16(6), 633-655. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2014.966124

Alvidrez J, Castille D, Laude-Sharp M, Rosario A, Tabor D (2019) The national institute on minority health and health disparities research framework. Am J Public Health 109(S1):S16–S20

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. (2017). NIMHD Research Framework. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved March 1 from https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework.html

Wang D, Choi JK, Shin J (2020) Long-term neighborhood effects on adolescent outcomes: mediated through adverse childhood experiences and parenting stress. J Youth Adolesc 49(10):2160–2173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01305-y

Jacoby SF, Dong B, Beard JH, Wiebe DJ, Morrison CN (2018) The enduring impact of historical and structural racism on urban violence in Philadelphia. Soc Sci Med 199:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.038

McClure E, Feinstein L, Cordoba E, Douglas C, Emch M, Robinson W, Galea S, Aiello AE (2019) The legacy of redlining in the effect of foreclosures on Detroit residents’ self-rated health [journal article]. Health Place 55:9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.10.004

Mitchell, B., & Franco, J. (2018). HOLC "redlining" maps: The persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality. N. C. R. Coalition. https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/02/NCRC-Research-HOLC-10.pdf

Nardone AL, Casey JA, Rudolph KE, Karasek D, Mujahid M, Morello-Frosch R (2020) Associations between historical redlining and birth outcomes from 2006 through 2015 in California [Article]. PLoS ONE 15(8):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237241

Dyer Z, Alcusky MJ, Galea S, Ash A (2023) Measuring the enduring imprint of structural racism on American neighborhoods. Health Aff 42(10):1374–1382. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00659

Bishop-Royse J, Lange-Maia B, Murray L, Shah RC, DeMaio F (2021) Structural racism, socio-economic marginalization, and infant mortality. Public Health 190:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.10.027

Chambers BD, Baer RJ, McLemore MR, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL (2019) Using index of concentration at the extremes as indicators of structural racism to evaluate the association with preterm birth and infant mortality-California, 2011–2012. J Urban Health 96(2):159–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0272-4

Davis DW, Jawad K, Feygin Y, Creel L, Kong M, Sun J, Lohr WD, Williams PG, Le J, Jones VF, Trace M, Pasquenza N (2021) Disparities in ADHD diagnosis and treatment by race/ethnicity in youth receiving Kentucky Medicaid in 2017. Ethn Dis 31(1):67–76. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.31.1.67

El-Menyar A, Abuzaid A, Elbadawi A, McIntyre M, Latifi R (2019) Racial disparities in the cardiac computed tomography assessment of coronary artery disease: does gender matter. Cardiol Rev 27(1):14–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0000000000000206

Fiscella K, Kitzman H (2009) Disparities in academic achievement and health: the intersection of child education and health policy [Review]. Pediatrics 123(3):1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0533

Ganguly S, Mailankody S, Ailawadhi S (2019) Many shades of disparities in myeloma care [Review]. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 39:519–529. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_238551

Gudino OG, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL (2009) Understanding racial/ethnic disparities in youth mental health services: do disparities vary by problem type? J Emot Behav Disord 17(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000365

Howell E, Decker S, Hogan S, Yemane A, Foster J (2010) Declining child mortality and continuing racial disparities in the era of the medicaid and SCHIP insurance coverage expansions. Am J Public Health 100(12):2500–2506. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.184622

Lipson SK, Kern A, Eisenberg D, Breland-Noble AM (2018) Mental health disparities among college students of color. J Adolesc Health 63(3):348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.014

Morgan PL, Hillemeier MM, Farkas G, Maczuga S (2014) Racial/ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis by kindergarten entry. J Child Psychol Psychiat 55(8):905–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12204

Weisleder A, Cates CB, Dreyer BP, Berkule Johnson S, Huberman HS, Seery AM, Canfield CF, Mendelsohn AL (2016) Promotion of positive parenting and prevention of socioemotional disparities. Pediatrics 137(2):e20153239. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3239

Whitney DG, Peterson MD (2019) US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr 173(4):389–391. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399

Myers HF (2009) Ethnicity-and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: an integrative review and conceptual model. J Behav Med 32(1):9–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4

Iruka IU, Gardner-Neblett N, Telfer NA, Ibekwe-Okafor N, Curenton SM, Sims J, Sansbury AB, Neblett EW (2022) Effects of racism on child development: advancing antiracist developmental science. Annu Rev Dev Psychol 4(1):109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121020-031339

Kirby JB, Taliaferro G, Zuvekas SH (2006) Explaining racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Med Care 44(5 Suppl):I64-72. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000208195.83749.c3

Acevedo-Garcia D, McArdle N, Hardy EF, Crisan UI, Romano B, Norris D, Baek M, Reece J (2014) The child opportunity index: improving collaboration between community development and public health. Health Aff 33(11):1948–1957. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0679

Noelke, C., McArdle, N., Baek, M., Huntington, N., Huber, R., Hardy, E., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2020). Child Opportunity Index 2.0 Technical Documentation. diversitydatakids.org. Retrieved March 3 from diversitydatakids.org/research-library/research-brief/how-we-built-it

Lohr WD, Creel L, Feygin Y, Stevenson M, Smith MJ, Myers J, Woods C, Liu G, Davis DW (2018) Psychotropic polypharmacy among children and youth receiving Medicaid, 2012–2015. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 24(8):736–744

Parker A (2021) Reframing the narrative: Black maternal mental health and culturally meaningful support for wellness. Infant Ment Health J 42(4):502–516

Vance MM, Wade JM, Brandy M Jr, Webster AR (2023) Contextualizing Black women’s mental health in the twenty-first century: gendered racism and suicide-related behavior. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 10(1):83–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01198-y

Aylward BS, Gal-Szabo DE, Taraman S (2021) Racial, ethnic, and sociodemographic disparities in diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr 42(8):682–689. https://doi.org/10.1097/dbp.0000000000000996

Davis DW, Feygin Y, Creel L, Kong M, Jawad K, Sun J, Blum NJ, Lohr WD, Williams PG, Le J, Jones VF, Pasquenza N (2020) Epidemiology of treatment for preschoolers on Kentucky Medicaid diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 30(7):448–455

Davis DW, Feygin Y, Creel L, Williams PG, Lohr WD, Jones VF, Le J, Pasquenza N, Ghosal S, Jawad K, Yan X, Liu G, McKinley S (2019) Longitudinal trends in the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and stimulant use in preschool children on Medicaid. J Pediatr 207:185-191.e181

Magaña, S., & Vanegas, S. B. (2021). Culture, race, and ethnicity and intellectual and developmental disabilities. In APA handbook of intellectual and developmental disabilities: Foundations, Vol. 1 (pp. 355–382). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000194-014

Bukten A, Virtanen S, Hesse M, Chang Z, Kvamme TL, Thylstrup B, Tverborgvik T, Skjærvø I, Stavseth MR (2024) The prevalence and comorbidity of mental health and substance use disorders in Scandinavian prisons 2010–2019: a multi-national register study. BMC Psychiat 24(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05540-6

Han B, Compton, WM, Blanco C, & Colpe LJ (2017) Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of U.S. adults with mental health and substance use disorders (Health Affairs Project Hope), Vol 36, U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, p 1739–1747

Kazemitabar M, Nyhan K, Makableh N, Minahan-Rowley R, Ali M, Wazaify M, Tetrault J, Khoshnood K (2023) Epidemiology of substance use and mental health disorders among forced migrants displaced from the MENAT region: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. PLoS ONE 18(10):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292535

Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, Black LI, Jones SE, Danielson ML, Hoenig JM, Davis Jack SP, Brody DJ, Gyawali S, Maenner MJ, Warner M, Holland KM, Perou R, Crosby AE, Blumberg SJ, Avenevoli S, Kaminski JW, Ghandour RM (2022) Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Suppl 71(2):1–42. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

Blair C (2010) Stress and the development of self-regulation in context. Child Dev Perspect 4(3):181–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00145.x

Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood Adoption and Dependent Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Garner, A. S., Shonkoff, J. P., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., & Wood, D. L. (2012). Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics, 129(1), e224-e231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2662

Doom JR, Gunnar MR (2013) Stress physiology and developmental psychopathology: past, present, and future [Review]. Dev Psychopathol 25(4 Pt 2):1359–1373

Evans, G. W., & Kim, P. (2013). Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Dempsey AG, Keller-Margulis MA (2020) Developmental and medical factors associated with parenting stress in mothers of toddlers born very preterm in a neonatal follow-up clinic. Infant Ment Health J 41(5):651–661

Kelly MM, Li K (2019) Poverty, toxic stress, and education in children born preterm. Nurs Res 68(4):275–284

Mayne SL, DiFiore G, Hannan C, Virudachalam S, Glanz K, Fiks AG (2022) Association of neighborhood social context and perceived stress among mothers of young children [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Academic Pediatrics 22(8):1414–1421

McClendon J et al (2021) Black-White racial health disparities in inflammation and physical health: cumulative stress, social isolation, and health behaviors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 131:105251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105251

Shonkoff JP, Slopen N, Williams DR (2021) Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the impacts of racism on the foundations of health. Annu Rev Public Health 42:115–134. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940

Acevedo-Garcia D, Noelke C, McArdle N, Sofer N, Hardy EF, Weiner M, Baek M, Huntington N, Huber R, Reece J (2020) Racial and ethnic inequities in children’s neighborhoods: evidence from the new child opportunity index 2.0 [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Health Affairs 39(10):1693–1701

Shen Y (2022) Race/ethnicity, built environment in neighborhood, and children’s mental health in the US. Int J Environ Health Res 32(2):277–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2020.1753663

Austin JL, Jeffries EF, Winston Iii W, Brady SS, Winston W 3rd (2022) Race-related stressors and resources for resilience: associations with emotional health, conduct problems, and academic investment among African American early adolescents [journal article]. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiat 61(4):544–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.05.020

Benson JE (2014) Reevaluating the “subjective weathering” hypothesis: subjective aging, coping resources, and the stress process. J Health Soc Behav 55(1):73–90

Buckner JD, Morris PE, Shepherd JM, Zvolensky MJ (2022) Ethnic-racial identity and hazardous drinking among black drinkers: a test of the minority stress model. Addict Behav 127:107218

Assari S, Mincy R (2021) Racism may interrupt age-related brain growth of African American children in the United States. J Pediatr Child Health Care 6(3):1047

Bouchard ME, Kan K, Tian Y, Casale M, Smith T, De Boer C, Linton S, Abdullah F, Ghomrawi HMK (2022) Association between neighborhood-level social determinants of health and access to pediatric appendicitis care. JAMA Netw Open 5(2):e2148865. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48865

Dempster, R., Davis, D. W., Jones, V. F., & Ryan, L. (2013). The role of stigma in parental help-seeking for child behavior problems among urban African American parents.

Dorsey BF, Cook LJ, Katz AD, Sapiro HK, Kadish HA, Holsti M (2023) Health care provider bias in estimating the health literacy of caregivers in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 39(12):e80–e85

Jackson JL, Grant V, Barnett KS, Ball MK, Khalid O, Texter K, Laney B, Hoskinson KR (2023) Structural racism, social determinants of health, and provider bias: Impact on brain development in critical congenital heart disease. Can J Cardiol 39(2):133–143

Okoro ON, Hillman LA, Cernasev A (2020) “We get double slammed! ”: healthcare experiences of perceived discrimination among low-income African-American women [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Women’s health 16:1745506520953348

Oluwoye O, Amiri S, Kordas G, Fraser E, Stokes B, Daughtry R, Langton J, McDonell MG (2022) Geographic disparities in access to specialty care programs for early psychosis in Washington State [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Adm Policy in Mental Health 49(1):5–12

Phillips D, Lauterbach D (2017) American Muslim immigrant mental health: the role of racism and mental health stigma. J Muslim Mental Health 11(1):39–56. https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0011.103

Butler-Barnes ST, Richardson BL, Chavous TM, Zhu J (2019) The importance of racial socialization: school-based racial discrimination and racial identity among African American adolescent boys and girls. J Res Adolesc 29(2):432–448

Byrd CM, Legette KB (2022) School ethnic-racial socialization and adolescent ethnic-racial identity. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 28(2):205–216

Gibson SM, Bouldin BM, Stokes MN, Lozada FT, Hope EC (2022) Cultural racism and depression in Black adolescents: examining racial socialization and racial identity as moderators [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Res Adolesc 32(1):41–48

Shen Y, Lee H, Choi Y, Hu Y, Kim K (2022) Ethnic-racial socialization, ethnic-racial identity, and depressive symptoms in Korean adolescents in the United States and China. J Youth Adolesc 51(2):377–392

Abuelezam NN, Cuevas AG, Galea S, Hawkins SS (2022) Contested racial identity and the health of women and their infants. Prev Med 155:106965

Adam EK, Hittner EF, Thomas SE, Villaume SC, Nwafor EE (2020) Racial discrimination and ethnic racial identity in adolescence as modulators of HPA axis activity. Dev Psychopathol 32(5):1669–1684

Butler-Barnes ST, Leath S, Williams A, Byrd C, Carter R, Chavous TM (2018) Promoting resilience among African American girls: racial identity as a protective factor [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Child Dev 89(6):e552–e571

Rhoad-Drogalis A, Dynia JM, Justice LM, Purtell KM, Logan JAR, Salsberry PJ (2020) Neighborhood influences on perceived social support and parenting behaviors. Matern Child Health J 24(2):250–258

Pasco MC, White RMB, Iida M, Seaton EK (2021) A prospective examination of neighborhood social and cultural cohesion and parenting processes on ethnic-racial identity among U.S. Mexican adolescents. Dev Psychol 57(5):783–795

Quinn CR, Hope EC, Cryer-Coupet QR (2020) Neighborhood cohesion and procedural justice in policing among Black adults: The moderating role of cultural race-related stress. J Community Psychol 48(1):124–141

Saleem FT, English D, Busby DR, Lambert SF, Harrison A, Stock ML, Gibbons FX (2016) The impact of African American parents’ racial discrimination experiences and perceived neighborhood cohesion on their racial socialization practices. J Youth Adolesc 45(7):1338–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0499-x

Coleman PK, Karraker KH (1997) Self-efficacy and parenting quality findings and future applications [Journal]. Dev Rev 18:47–85

Coleman PK, Karraker KH (2003) Maternal self-efficacy beliefs, competence in parenting, and toddlers’ behavior and developmental status. Infant Ment Health J 24:126–148

Drolet CE, Lucas T (2020) Perceived racism, affectivity, and C-reactive protein in healthy African Americans: do religiosity and racial identity provide complementary protection? [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. J Behav Med 43(6):932–942

Fetzer Institute & National Institute on Aging Working Group. (2003, 1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. In. Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute.

Walker RL, Salami TK, Carter SE, Flowers K (2014) Perceived racism and suicide ideation: mediating role of depression but moderating role of religiosity among African American adults. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behav 44(5):548–559

Baffsky R, Ivers R, Cullen P, Wang J, McGillivray L, Torok M (2023) Strategies for enhancing the implementation of universal mental health prevention programs in schools: a systematic review [Systematic Review Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Prev Sci 24(2):337–352

Ladegard K, Alleyne S, Close J, Hwang MD (2024) The role of school-based interventions and communities for mental health prevention, tiered levels of care, and access to care. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 33(3):381–395

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technologies. (2016). Health Information Exchange and Behavioral Health Care: What is it and How is it Useful? Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy/Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. Retrieved August 7 from https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/playbook/pdf/behavioral-health-care-fact-sheet.pdf

Burak EW, Wachino V (2023) Promoting the mental health of parents and children by strengthening medicaid support for home visiting. Psychiatr Serv 74(9):970–977

Constantino JN (2023) Bridging the divide between health and mental health: new opportunity for parity in childhood [Editorial Comment]. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiat 62(11):1182–1184

Hardeman RR, Homan PA, Chantarat T, Davis BA, Brown TH (2022) Improving the measurement of structural racism to achieve antiracist health policy. Health Aff 41(2):179–186. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01489

Harnois CE, Bastos JL, Campbell ME, Keith VM (2019) Measuring perceived mistreatment across diverse social groups: an evaluation of the everyday discrimination scale. Soc Sci Med 232:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.011

Kirkinis K, Pieterse AL, Martin C, Agiliga A, Brownell A (2021) Racism, racial discrimination, and trauma: a systematic review of the social science literature. Ethn Health 26(3):392–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1514453

Funding

No funding was acquired to support the study or the manuscript development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data analyses were performed by Dr. Kahir Jawad. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. Deborah Winders Davis. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Louisville and the Research Office of Norton Healthcare. No consent was obtained as clinical data were extracted for secondary data analysis of existing data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, D.W., Jawad, K., Feygin, Y.B. et al. The Relationships Among Neighborhood Disadvantage, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Diagnoses, and Race/Ethnicity in a U.S. Urban Location. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01751-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01751-w