Abstract

Subclinical symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder (i.e., obsessive compulsive symptoms, or “OCS”) cause functional impairment, including for youth without full-syndrome OCD. Further, despite high rates of OCS in youth with anxiety disorders, knowledge of OCS in the context of specific anxiety disorders is limited. The present study seeks to: (1) compare OCS in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders and healthy youth, (2) determine which categorical anxiety disorder(s) associate most with OCS, and (3) determine relationships between OCS with anxiety severity and impairment. Data on OCS, anxiety, and functional impairment were collected from 153 youth with anxiety disorders and 45 healthy controls, ages 7–17 years (M = 11.84, SD = 3.17). Findings indicated that patients had significantly more OCS than healthy controls. Among patients, GAD was a significant predictor of OCS as well as OCD risk. These results suggest that OCS should be a primary diagnostic and treatment consideration for youth who present in clinical settings with GAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a heterogenous, chronic, and impairing psychiatric disorder with a prevalence rate of 1–2% in pediatric populations [15, 60]. Prior work has shown that symptoms of OCD are dimensional and heterogeneous, and large community studies have found that obsessions and/or compulsions occur across a range of sub-clinical severity in up to 38% of youth [3, 11]. These subclinical manifestations of obsessive–compulsive symptoms, referred to as OCS, have potential to result in functional impairment, even in those who never cross diagnostic threshold for full-syndrome OCD [7, 15, 26]. Furthermore, OCS interact with other childhood psychopathology (e.g., separation anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity, or tic disorders), such that comorbidity influences the manifestation and course of later onset OCD [19]. Despite negative long-term outcomes for youth with OCD or subclinical OCS, obsessions and compulsions are frequently overlooked in children, often going undetected and untreated [65]. One challenge for the detection of OCD and OCS in childhood may be that symptoms overlap with more widely recognized symptoms of other disorders, particularly anxiety disorders [17], which affect up to 33% of youth by adolescence [50]. Distinguishing OCS in the context of anxiety disorders can be challenging but may have important implications for clinical conceptualization (e.g., understanding the nature and extent of impairment which may arise from OCS above and beyond anxiety symptoms and treatment (e.g., understanding degrees to which exposure and response prevention should be incorporated into evidence-based interventions [45, 51], in anxiety-affected youth.

Anxiety and OCS: Differential Diagnosis

OCS occur commonly in youth sampled from the general population [11], and their occurrence is even more pronounced among those with anxiety disorders. One study of adults reported that the presence of an anxiety disorder increased the odds for endorsing at least one OC symptom by 2.34 [27]. In a separate study, children ages 6–12 with an anxiety disorder were 3.68 times likelier than healthy controls to meet OCS levels indicative of being “at risk for OCD” [61]. Finally, in a community sample of 9937 children ages 6–12 with subclinical-to-clinical anxiety symptoms, 68.9% of those who endorsed anxiety symptoms at least one OC symptom [7]. Of note, different questionnaires and threshold criteria for symptoms were used in different studies, so direct comparisons should be made with caution. What is clear, however, is that OCS prevalence is notably higher in samples that report symptoms of anxiety. This aligns with comorbidity rates observed in pediatric OCD. Anxiety disorders are the most frequent comorbidity in childhood OCD, co-occurring in 50–70% of cases [28, 39, 55].

High rates of reported comorbidity between childhood anxiety and OCD may in part be inflated by diagnostic confusion as a result of phenomenological proximity between the two disorders; repetitive negative thinking and associated anxiety characterizes both worry (i.e. anxiety) and obsessions (i.e. OCD; [17, 30]. However, work on common genetic, brain and/or psychosocial mechanisms underlying both anxiety and OCD provides support for genuine co-occurrence [22, 44]. Distinguishing between anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorders is warranted given (1) the distinction made between OCD and anxiety disorders in the DSM-5 [8], and (2) the implications for treatment. For example, although exposure is the most active treatment component for both OCD and anxiety in youth [6, 12, 57, 73], the treatment manuals remain distinct, with OCD-focused manuals including more emphasis on identifying and eliminating compulsions (exposure and response prevention), whereas exposure-focused CBT for anxiety tends to incorporate more cognitive treatment elements [57, 73]. Moreover, up to 40–50% of pediatric anxiety patients undergoing therapy still experience clinically significant symptoms or experience later relapse [32, 56]. Novel CBT treatment augmentations which target core constructs underlying the co-occurrence anxiety and OCD may be more appropriate for children with high levels of OCS in anxiety [30, 68]. The current study provides an opportunity to observe how OCS manifest in anxiety disorders, rather than the reverse (i.e., quantifying anxiety symptoms in OCD), which may inform the clinical conceptualization, and potentially management, of patients with anxiety disorders who present with co-morbid OCS.

Indexing OCS

Given the high prevalence of OCS in anxiety disorders and OCS-related risk for future impairment, early, accurate screening for OCS in anxiety-affected youth has the potential to help inform treatment and prognosis. OCS should be assessed along a non-clinical to clinical continuum of severity in youth to capture the range of subclinical experiences. A number of dimensional OCS scales have been validated for use with children, including two that were used in the present study: the Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory–Revised (OCI-R; [24]) and the OCS subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL-OCS; [5]).

OCS Within Specific Pediatric Anxiety Disorders

Among anxiety disorders, comorbid OCD has been reported to occur most commonly with generalized anxiety (GAD) and separation anxiety disorders [15, 18, 28, 29, 39, 47, 49, 59, 66], but whether or not subclinical OCS selectively associate with any specific anxiety disorder(s) remains unknown. Further insight into which anxiety diagnoses are associated with OCS may facilitate the identification of clinically anxious groups who are most likely to benefit from OCS screening and consideration of OCS in treatment planning. Moreover, distinguishing OCS from the various types of anxiety may guide identification of common versus distinct mechanisms of illness, as suggested by the Research Domain Criteria framework for understanding psychopathology across dimensions of human behavior [33, 38].

OCS Impact on Anxiety Severity and Related Impairment

Implications of OCD and subclinical OCS for anxiety severity and functional impairment in youth with anxiety disorders remain poorly understood. Pediatric patients with OCD and comorbid anxiety have more impairment than those without comorbid anxiety [66, 72] and are more refractory to treatment [68]. Moreover, in community samples of youth, subclinical OCS appeared to associate with distress and functional impairment [15], as well as history of depression, psychosis, and suicidal ideation [11]. Longitudinal studies show that subclinical OCS in childhood not only increase risk for later onset OCD, but also for impairment in those who never meet criteria for OCD [26]. Taken together, these studies indicate that OCS appear to generally induce impairment, though it remains unclear whether OCS elevate impairment when co-occurring with an anxiety disorder.

Current Study

To better characterize OCS in the context of pediatric anxiety disorders, we applied dimensional OCS screening in youth with and without anxiety disorders. First, we sought to measure OCS in patients compared to healthy controls. Next, among patients, we sought to determine which categorical anxiety disorder(s) are most associated with OCS, and whether OCS relate to greater severity of non-OCD anxiety symptoms and/or more functional impairment. Structured clinical interviews were used to establish anxiety disorder(s) and other diagnoses, anxiety symptom severity, and overall functional impairment. Youth self-report was used to measure OCS and risk for OCD using the OCI-R [2], and parent report on the CBCL-OCS served as a secondary measure of OCS and risk for OCD [61]. We hypothesized significantly higher OCS scores in youth with an anxiety disorder diagnosis as compared to healthy controls. Among clinically anxious youth, we hypothesized that GAD and SAD would selectively associate with OCS severity and OCD risk status. We also predicted that more severe OCS would associate with greater severity of non-OCD anxiety symptoms and greater functional impairment.

Materials and Methods

Participants

A total of 206 youth participants were recruited through community clinics and online advertisements as part of a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study of neural mechanisms of CBT effect [58]. The recruited sample included 158 participants who met criteria for an anxiety disorder (75.2% female, aged 11.69 ± 3.07) and 48 healthy controls (55.6% female, aged 12.36 ± 3.49). Inclusion required that anxiety disorders were the primary source of interference and distress, established on clinician-administered interview with the DSM-5 version of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; [40]). Comorbid diagnosis of OCD was only allowed if secondary (i.e., less interfering, less severe) to the primary anxiety disorder(s). Other allowable secondary diagnoses included attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional disorder. Exclusion criteria included current psychotropic medication, current psychotherapy, current major depression or substance/alcohol abuse/dependence, lifetime diagnoses of bipolar and psychotic disorders, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and acute suicidal risk. Healthy control subjects had no lifetime history of any psychiatric disorder. As part of the larger functional neuroimaging study, standard fMRI inclusion/exclusion criteria also applied (e.g., no metal implants). All participants and respective guardians provided informed assent/consent in compliance with the policies of the Michigan Medicine Institutional Review Board (HUM00118950). Of note, the sample of anxious youth was predominantly female, which is noted as a limitation for generalizability in this paper. While this uneven sampling was unintentional, potential explanations for the female-biased sample are: 1) anxiety is more common in girls in this age range, at almost twice the rate as boys [47] and 2) this sample is composed of baseline data from a randomized clinical trial (RCT) for anxiety treatment of two gender-matched treatment groups, thus amplifying the overall mismatch between girls and boys in the sample (Table 1).

Measures

Baseline measures established patient eligibility, specific anxiety disorder diagnoses, anxiety severity, OCS severity, global severity of illness, and overall impairment. The same measures were delivered to youth participants in the anxiety disorder and healthy groups (Table 2).

Anxiety Diagnoses

Anxiety diagnoses were determined through structured clinical interviews using the K-SADS, a reliable and validated instrument based on DSM-5 criteria [8]. Assessments were completed by a master’s level clinician trained to reliability on the measure. Both the child and caregiver were present, either separately or together. In our sample, K-SADS anxiety diagnoses for which criteria was met included generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and unspecified anxiety disorder (i.e., Anxiety Disorder NOS). As in previously reported clinical samples [41], many patients met diagnostic criteria for ≥ 2 or anxiety disorders (Table 3). Thus, to assess which individual anxiety disorder(s) most associated with OCS, each anxiety disorder was considered a feature of the patient’s overall anxiety disorder phenotype. For example, a participant who met criteria for social anxiety disorder and specific phobia was counted as having both social anxiety and specific phobia.

OCS Symptoms

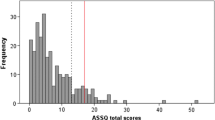

The primary measure of OCS was youth self-report on the Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory–Revised (OCI-R; [24]). The OCI-R has been validated in OCD and anxiety samples [2, 24] and assesses symptoms of OCD along a clinical to non-clinical range of severity. There are 18 questions scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4 for each item). The possible range of scores is 0–72, calculated by summing the scores of each item, with higher scores indicating more OCS. Scores greater than or equal to 21 suggest current OCD [24].

OCS were also assessed by parent report on youth on the OCS subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL-OCS; [5]. The CBCL-OCS is a validated instrument that allows for the assessment of OCS dimensionally in children [37]. It is comprised of 4 items each from the CBCL-Anxious/Depressed and Thought Problems syndrome scales, summed to compose the CBCL-OCS score. Items are rated as 0 (“absent”), 1 (“occurs sometimes”), or 2 (“occurs often”), allowing for a continuous range of OCS scores from 0 to 16. Scores greater than or equal to 5 suggest being at risk for OCD [37, 61].

Anxiety Severity

Anxiety severity was assessed using the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS), a validated instrument delivered through structured clinical interview [35]. Ratings were completed by a master’s level clinician trained to reliability on the measure. Both the child and caregiver were present for PARS ratings, either separately or together. The PARS includes a checklist to ascertain anxiety symptom type(s) (e.g., generalized, separation, social, etc.), and then collapses across types to generate an overall severity score [35]. PARS scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflecting higher anxiety severity. The reported optimum cutoff score to discriminate youth with and without anxiety disorders is 17.5 [31].

Global Severity of Illness

Global severity of illness was assessed using the Clinical Global Impressions Severity scale (CGI-S; [14]), a well-established and validated research rating tool rated by a clinician. The instrument asks the clinician: “Considering your total clinical experience with this particular population, how mentally ill is the patient at this time?” Ratings are based upon observed and reported symptoms, behavior, and function across the past 7 days: 1 = normal, not at all ill, 2 = borderline mentally ill; 3 = mildly ill; 4 = moderately ill; 5 = markedly ill; 6 = severely ill; 7 = among the most extremely ill patients. The CGI-S was administered by an independent evaluator at baseline clinical assessment.

Overall Impairment

Overall functioning was assessed using the Clinical Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; [62]), a validated instrument rated by a clinician. Scores range from 1 to 100, with lower scores indicating impairments in functioning across settings (home, school, with peers), activities and interests. The scale is divided into 10-point intervals, each headed with a description of the level of functioning (e.g., “60–51—Variable functioning with sporadic difficulties or symptoms in several but not all social areas). Psychiatric impairment is indicated by scores of 60 or less [52].

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

Demographic and descriptive characteristics were summarized for youth with and without anxiety disorders. Means, standard deviations, and range of OCI-R, CBCL-OCS, PARS, CGI-S and CGAS scores were calculated for each anxiety disorder (i.e., including scores for all participants meeting K-SADS criteria for that diagnosis) and for healthy controls.

Comparison to Healthy Controls

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare OCI-R and CBCL-OCS scores between youth with and without anxiety disorders.

Anxiety Disorders that Most Predict OCS Severity

Multiple linear regression was used to test which anxiety disorders most associate with OCI-R scores. Assumptions of linear regression were checked, with no multicollinearity existing between independent variables. A separate linear regression tested the same anxiety disorder predictors to determine which anxiety disorders most associated with CBCL-OCS. Analyses were conducted in R, using the linear model function within the “stats” package (version 4.0.2). Additionally, a stepwise multiple linear regression was conducted to confirm the most relevant anxiety disorder diagnosis for predicting OCI-R score. The “olsrr” package (version 0.5.3) in R was used to calculate AIC values for models with each combination of anxiety disorder predictors. The model with the lowest AIC, indicating the model of best fit for the prediction of OCI-R score, was selected and interpreted. Finally, sensitivity analyses testing each anxiety disorder as the predictor in a univariate regression analysis were conducted to better understand the effects (or lack thereof) of anxiety disorder comorbidity on the relationship of anxiety disorders to OCS.

Anxiety Disorders that Most Predict Categorical Risk for OCD

Previously established cutoff scores for the OCI-R (14; [2]) and CBCL-OCS (4 [61]), were used to identify participants with heightened risk for developing OCD. Binary logistic regressions were used to test for the anxiety disorder(s) most associated with risk for developing OCD (binary cutoff point of OCI-R ≥ 14 or CBCL-OCS ≥ 5).

Of note, age and gender were covaried in all regression models.

Effect of OCS on Anxiety Severity and Functional Impairment

Bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for total OCI-R score, total CBCL-OCS score, total PARS score, CGI-S score, and CGAS score. Each correlation test was useful for a distinct research question related to how functionally impairing OCS might be. The correlation between OCS (both as OCI-R and CBCL-OCS) and PARS score was conducted to assess whether greater obsessive–compulsive symptoms were associated with greater severity of anxiety overall. Correlations between OCS (both as OCI-R and CBCL-OCS) and CGI-S and CGAS were conducted to assess whether greater obsessive–compulsive symptoms were associated with greater global severity of illness and/or greater overall functional impairment. Additionally, post-hoc analyses were conducted to assess the correlation between OCI-R score and score on the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), which was a self-report measure of depressive symptomology collected from youth as part of the study. The aim of this follow-up analysis was to evaluate whether greater OCS associated with greater depressive symptoms, potentially indicating increased impairment through depressed mood.

Results

Descriptives

Of the 206 total participants enrolled (158 with anxiety disorders; 48 healthy controls), 153 participants with anxiety disorders and 45 healthy controls were retained in the final analyses (5 anxiety disorder participants and 4 healthy control participants were excluded due to incomplete data). Ethnicity, race, and socioeconomic status of the sample are reported in Table 1. All participants with anxiety disorders met criteria for at least one of the following: generalized anxiety disorder (n = 122), social anxiety disorder (n = 73), specific phobia (n = 48), separation anxiety (n = 43), or unspecified anxiety disorder (n = 8). Of the anxiety group, 101 subjects (66% of the sample) met criteria for more than one anxiety disorder diagnosis. Seven participants with a primary anxiety disorder diagnosis (4.6%) also met diagnostic criteria for OCD (Table 3).

Comparison to Healthy Controls

Independent samples t-tests indicated that the anxiety group had significantly higher OCS scores than the healthy control group when OCS was indexed with both the OCI-R and the CBCL-OCS (Table 2).

Anxiety Disorders that Predict OCS

Of the anxiety disorder predictors, only the presence of GAD significantly predicted OCI-R scores (b = 6.74, SE = 2.14, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.08) in the multiple linear regression model (F(7, 145) = 2.562, p = 0.02, R2 = 0.07; Table 4). By contrast, no anxiety disorders significantly predicted CBCL-OCS scores, our secondary measure of OCS. Neither age or gender interacted with an anxiety disorder to predict OCI-R or CBCL-OCS scores. In follow-up sensitivity analyses, GAD positively predicted OCS at trend-level (b = 0.88, SE = 0.45, p = 0.05), but only unspecified anxiety significantly predicted OCS, though the association was negative (b = − 1.62, SE = 0.82, p = 0.049).

Anxiety Disorders that Predict OCD Risk

The presence of GAD significantly predicted being at risk for OCD in a logistic regression analysis using the OCI-R “at risk” cutoff of 14 [2]. Results showed that, holding other predictors constant, being at risk for OCD (as defined by CBCL-OCS scores > 4) increased by a factor of 4.66 for those with GAD versus those without GAD (Table 5). The presence of GAD also associated with OCD risk status when measured using the CBCL-OCS “at risk” cutoff of 5 [61]. When defined using the CBCL-OCS cutoff, OCD risk status increased by a factor of 4.81 for those with GAD versus those without GAD (Table 6).

Correlations

Scores on the OCI-R positively correlated with number of comorbid anxiety disorders, but not with anxiety severity (PARS), illness severity (CGI-S), or overall impairment (CGAS; Table 7). OCI-R score was significantly positively correlated with CDI score, such that greater OCS associated with greater depressive symptoms (r = 0.51, p < 0.001). Positive correlation of scores on the OCI-R and CBCL-OCS were also observed.

Discussion

As expected, mean OCS scores were significantly higher in the anxiety disorder group than the healthy control group when measured with both the OCI-R and the CBCL-OCS. This aligns with recent work emphasizing the maladaptive impact of OCS [7, 15, 26, 61]. It possible that, due to phenomenological proximity, symptoms characteristic of childhood anxiety disorders are diagnostically blurred with those of OCD in measurement. The significant presence of OCS detected in youth with anxiety disorders may warrant a return to closer proximity of anxiety and OCD (i.e., a shared chapter) in diagnostic manuals such as the DSM, which changed OCD to be classified as diagnostically distinct from anxiety disorders in its fifth edition [4].

Within categorical anxiety predictors, there was no relationship between separation anxiety and OCS, which deviated from our hypothesis and prior results published by Voltas et al. [71], who found separation anxiety to be a significant predictor of “obsessiveness” (i.e., OCS). Consistent with our hypothesis, GAD significantly predicted OCS when using the OCI-R, and GAD symptoms significantly predicted binary (i.e., “at risk” vs. “not at risk”) OCD-risk status when indexed via both the OCI-R and CBCL-OCS. Importantly, the effect size for the overall multiple linear regression model was small, and GAD showed no linear relationship with OCS when using the CBCL-OCS, so findings should be interpreted with caution. However, it should be noted that the OCI-R is based on child report whereas the CBCL-OCS uses parent report; thus, it is possible that parents are less aware of the presence of OCS in their children than are children themselves.

Association Between GAD and OCS

The relationship between GAD and OCS in these data align with previous work linking GAD and OCD both etiologically and phenotypically. For instance, GAD has been found to co-occur with OCD in patients as well as their non-OCD-affected relatives, suggesting common familial etiology [53]. GAD and OCD also have similar early ages of onset [48], share similar patterns of co-morbidity with other disorders [34], and were demonstrated in one study to possess similar abnormalities in the frequency of a serotonin neurotransmitter gene pattern (distinct patterns which did not occur in panic or phobic disorders[54]. From a phenotypic lens, symptom profiles are similar, particularly in pediatric populations. Worry about future events and repetitive negative thoughts which patients recognize as excessive and difficult to control are hallmark features of both GAD and OCD [13, 17, 25, 30, 46, 67, 69, 74], leaving some to wonder whether GAD and OCD are manifestations of the same disorder [30, 63]. Clinicians often attempt to distinguish GAD from OCD based on thought content (i.e., GAD worries are more realistic, everyday concerns whereas OCD worries are more bizarre and ego-dystonic); however, in practice, types of worries occur along a continuum and can be particularly difficult to distinguish in youth who lack the cognitive ability to describe their thoughts or readily identify them as unrealistic [17, 22, 30].

Evidence for shared etiology and causal pathways supports a genuine selective association of OCS with GAD, while examples of phenotypic proximity may be more reflective of measurement overlap or expressions of the same disorder. Regardless of which leads to the relationship observed in our data, understanding traits common to both OCS and GAD can inform specific treatment augmentations which may improve outcomes for children who meet criteria for GAD and score high in OCS. One example of such a trait common to both is “intolerance of uncertainty,” or low tolerance for situations involving ambiguous or unknown outcomes (IU; [30, 63]. In a 2010 study, Fergus and Wu demonstrated that IU, perfectionism, negative problem orientation, and responsibility/threat estimation all showed significant overlap between GAD and OCD, with IU emerging as the unique predictor of both disorders above other cognitive processes [23]. Symptomatically, feeling anxious as a result of uncertainty in patients with GAD may lead to excessive worry which, if unaddressed, may develop into OCS-like compulsions aimed at reducing uncertainty [17, 30].

Association Between OCS and Functional Impairment

Contrary to our hypotheses, the presence of OCS was not associated with anxiety severity on the PARS, or global severity/impairment on the CGI-S or CGAS in our clinically anxious sample. This may suggest that subclinical OCS do not impact functional impairment or severity when a primary anxiety disorder is already present. This finding could also be explained by the phenomenological proximity between OCS and anxiety symptoms (especially GAD, which may “mask” true OCS symptoms, eliminating any OCS-related effects on PARS; [1, 13, 17]. It is possible that for some patients, symptoms that were part of the GAD diagnosis registered as OCS on the OCI-R and/or CBCL-OCS scales rather than constituting their own unique OCS in addition to GAD.

While OCS did not relate to PARS, CGI-S, or CGAS severity, it did show a significant positive correlation with the number of comorbid anxiety diagnoses (with OCS indexed via OCI-R; see Table 7). That is, the more distinct anxiety diagnoses for which a patient met criteria, the more OC symptoms they reported on the OCI-R. Prior studies have found that greater amounts of concurrent anxiety disorders associate with more impairment [43, 66, 70]. Our own data replicate these findings, with number of concurrent anxiety diagnoses associating with all measures of severity (PARS, CGI-S, and CGAS; see Table 7). With this knowledge in mind, our finding that OCS relates to number of anxiety disorders indicates that OCS may in fact be associated with greater impairment, even if too subtle to be detected by scales such as the PARS, CGI-S, and CGAS.

Also of note, post-hoc analyses revealed a significant positive correlation between OCS and depressive symptoms, indicating further support for OCS associating with clinical impairment. While depressive symptoms in youth were not a primary aim for this paper, the clear relationship between OCS and CDI warrants further research on OCS in the context of depression.

Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment

Our findings that GAD predicts both severity of OCS across a clinical to non-clinical range as well as OCI-R-measured and CBCL-measured risk for OCD impart several clinical implications. First, comprehensive assessment of children who endorse symptoms of GAD should include screening for comorbid OCS or OCD. If a patient presents with GAD symptoms (or ambiguous symptoms related to excessive worry), it may be worthwhile to spend time normalizing more “unrealistic” worries that are unique to OCD (versus GAD) and which patients, especially youth, may be more hesitant to share with the clinician out of fear of judgement [34]. This approach may prove beneficial for achieving the correct diagnoses for a patient and individualizing treatment. In the context of treatment, our findings bolster the importance of exposure and response prevention relative to other components of CBT (e.g., cognitive restructuring and relaxation) often included in treatment manuals for childhood GAD [12], even if a full OCD diagnosis is not formally detected at intake. Children with GAD may also benefit from novel interventions designed to target intolerance of uncertainty, a core predictor of both OCD and GAD. One example of this type of psychotherapeutic intervention is the “No Worries! Program” [36], which targets IU that manifests via obsessions in patients with OCD and worry in those with GAD [17, 30].

Limitations & Future Directions

Our results should be interpreted considering a few important limitations. First, aligned with past work demonstrating high comorbidity in child psychopathology [64], there were few “pure” anxiety diagnoses in our sample (66% were comorbid with at least one other anxiety and/or OCD diagnosis). This compromised our ability to examine OCS in one specific anxiety disorder compared to another (i.e., GAD only vs. separation anxiety only, etc.). However, sensitivity analyses assessing each anxiety disorder predictor in univariate regression models demonstrated the same pattern of results. Relatedly, a high proportion of individuals in our sample endorsed GAD (79.7% whereas all other anxiety diagnoses were endorsed by < 50%) and some diagnoses were endorsed by only a few patients (e.g., unspecified anxiety disorder). To address this imbalance, we integrated a hypothesis-driven inverse probability weighting (IPW) analysis to balance variability in the number of participants who met criteria for each anxiety disorder [10]; the results of this analysis were consistent with the original models. Additionally, our exclusion criteria were such that we did not allow patients with OCD to enroll in the study unless an anxiety diagnosis was primary. This may have limited our sampling of higher severity OCS, potentially explaining why OCS did not correlate with impairment in our analyses. Another limitation is that this sample of youth spanned a large age range, encompassing a period of pubertal development. Age was included as a covariate in the analyses to mitigate some of these effects, though the sample lacked enough power to stratify analyses by age. This study capitalized on baseline data from a RCT of CBT for anxiety, with fMRI, to characterize the relationship between OCS and anxiety in a sample of youth with diagnosed anxiety disorders. Despite the complexity of a longitudinal fMRI clinical trial study, the sample size is still comparable to other non-neuroimaging clinical studies of anxiety [9, 20, 42], and is also predominantly female. It is possible that the results from these analyses will not generalize to boys, though when analyses were stratified by gender, the pattern of the primary results was the same (i.e., GAD was the strongest positive predictor of OCS), though this predictor was not significant when evaluated only within boys, likely due to smaller sample size. Additionally, it is important to acknowledge that rates of OCS development in the context of anxiety disorders may vary by gender, especially in cases such as early-onset OCD which affects boys more than girls [21]. Therefore, future studies should assess the developmental trajectories of OCS in anxious youth, by gender.

There is also room for future studies to evaluate other ways of identifying OCS, or OCD risk, within a sample of youth with anxiety disorders. For instance, Chacon and colleagues [15] have shown that coercive behaviors, when assessed in first-degree relatives of patients diagnosed with OCD, associated with OCS and worse prognosis due to increased parental accommodation. Those findings indicate that coercive behaviors may reflect OCS and could be assessed in youth with anxiety disorders as a proxy for OCS and those who might be at risk for developing OCD [16, 66]. Further, future studies can examine the neural correlates associated with OCS, with respect to anxiety disorders, within this dataset. Finally, we note that our sample is quite homogenous in terms of demographic characteristics; data is derived from participants who are predominantly White American, non-Hispanic/Latino, and from non-low-socioeconomic-status backgrounds. Future work will aim to recruit more diverse samples to strengthen the generalizability of overall findings and increase the relevance of our research to more diverse communities.

Summary

To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to explore OCS prevalence and impact in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders. Findings indicate that patients with anxiety had significantly more OCS than healthy controls. Among patients, GAD was a significant predictor of OCS as well as OCD risk, which may reflect shared etiological pathways or phenotypic proximity between GAD and OCSOCS did not relate to higher anxiety severity or global severity/impairment, indicating that additional impairment may not be conferred by subclinical OCS when anxiety is already present. These results suggest that OCS should be a primary diagnostic and treatment consideration for youth who present in clinical settings with GAD, including use of specific OCS screening tools and treatments which target constructs shared by both OCS and GAD.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

References

Abramowitz JS, Foa EB (1998) Worries and obsessions in individuals with obsessive–compulsive disorder with and without comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther 36(7–8):695–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00058-8

Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ (2006) Psychometric properties and construct validity of the obsessive-compulsive inventory–revised: replication and extension with a clinical sample. J Anxiety Disord 20(8):1016–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.001

Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, Olatunji BO, Wheaton MG, Berman NC, Losardo D, Timpano KR, Mcgrath PB, Riemann BC, Adams T, Storch EA, Hale LR (2010) Assessment of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions: development and evaluation of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale. Psychol Assess 22(1):180–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018260

Abramowitz J, Jacoby R (2014) The use and misuse of exposure therapy for obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rev 10(4):277–283. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573400510666140714171934

Achenbach TM (1999) The child behavior checklist and related instruments. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp 429–466

Ale CM, McCarthy DM, Rothschild LM, Whiteside SPH (2015) Components of cognitive behavioral therapy related to outcome in childhood anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 18(3):240–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-015-0184-8

Alvarenga PG, Cesar RC, Leckman JF, Moriyama TS, Torres AR, Bloch MH, Coughlin CG, Hoexter MQ, Manfro GG, Polanczyk GV, Miguel EC, do Rosario MC (2015) Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions in a population-based, cross-sectional sample of school-aged children. J Psych Res 62:108–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.01.018

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association

Arch JJ, Eifert GH, Davies C, Plumb Vilardaga JC, Rose RD, Craske MG (2012) Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 80(5):750–765. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028310

Austin PC (2011) An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res 46(3):399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

Barzilay R, Patrick A, Calkins ME, Moore TM, Wolf DH, Benton TD, Leckman JF, Gur RC, Gur RE (2019) Obsessive-compulsive symptomatology in community youth: typical development or a red flag for psychopathology? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 58(2):277–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.038

Bilek E, Tomlinson RC, Whiteman AS, Johnson TD, Benedict C, Phan KL, Monk CS, Fitzgerald KD (2021) Exposure-focused CBT outperforms relaxation-based control in an RCT of treatment for child and adolescent anxiety. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 51(4):410–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2021.1901230

Brown TA, Moras K, Zinbarg RE, Barlow DH (1993) Diagnostic and symptom distinguishability of generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Ther 24(2):227–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80265-5

Busner J, Targum SD (2007) The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry 4(7):28–37

Canals J, Hernández-Martínez C, Cosi S, Voltas N (2012) The epidemiology of obsessive–compulsive disorder in Spanish school children. J Anxiety Disord 26(7):746–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.06.003

Chacon P, Bernardes E, Faggian L, Batistuzzo M, Moriyama T, Miguel EC, Polanczyk GV (2018) Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in children with first degree relatives diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 40(4):388–393. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2321

Comer JS, Kendall PC, Franklin ME, Hudson JL, Pimentel SS (2004) Obsessing/worrying about the overlap between obsessive–compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in youth. Clin Psychol Rev 24(6):663–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.004

Coskun M, Zoroglu S, Ozturk M (2012) Phenomenology, psychiatric comorbidity and family history in referred preschool children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 6(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-6-36

De Mathis MA, Diniz JB, Hounie AG, Shavitt RG, Fossaluza V, Ferrão Y, Leckman JF, De Bragança Pereira C, Do Rosario MC, Miguel EC (2013) Trajectory in obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidities. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23(7):594–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.08.006

Dugas MJ, Brillon P, Savard P, Turcotte J, Gaudet A, Ladouceur R, Leblanc R, Gervais NJ (2010) A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther 41(1):46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.004

Eichstedt JA, Arnold SL (2001) Childhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: A tic-related subtype of OCD? Clin Psychol Rev 21(1):137–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00044-6

Fitzgerald KD, Schroder HS, Marsh R (2021) Cognitive control in pediatric obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders: brain-behavioral targets for early intervention. Biol Psychiat 89(7):697–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.11.012

Fergus TA, Wu KD (2010) Do symptoms of generalized anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder share cognitive processes? Cogn Ther Res 34(2):168–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-009-9239-9

Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, Salkovskis PM (2002) The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess 14(4):485–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/10403590.14.4.485

Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R (1994) Why do people worry? Personality Individ Differ 17(6):791–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90048-5

Fullana MA, Mataix-Cols D, Caspi A, Harrington H, Grisham JR, Moffitt TE, Poulton R (2009) Obsessions and compulsions in the community: prevalence, interference, help-seeking, developmental stability, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions. Am J Psychiatry 166(3):329–336. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08071006

Fullana MA, Vilagut G, Rojas-Farreras S, Mataix-Cols D, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Haro JM, de Girolamo G, Lépine JP, Matschinger H, Alonso J (2010) Obsessive–compulsive symptom dimensions in the general population: results from an epidemiological study in six European countries. J Affect Disord 124(3):291–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.11.020

Geller DA, Biederman J, Griffin S, Jones J, Lefkowitz TR (1996) Comorbidity of juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder with disruptive behavior disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35(12):1637–1646. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199612000-00016

Geller DA, Biederman J, Faraone S, Agranat A, Cradock K, Hagermoser L, Kim G, Frazier J, Coffey BJ (2001) Developmental aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder: findings in children, adolescents, and adults. J Nerv Ment Dis 189(7):471–477. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200107000-00009

Gillett CB, Bilek EL, Hanna GL, Fitzgerald KD (2018) Intolerance of uncertainty in youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: a transdiagnostic construct with implications for phenomenology and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev 60:100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.01.007

Ginsburg GS, Keeton CP, Drazdowski TK, Riddle MA (2011) The Utility of clinicians ratings of anxiety using the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS). Child Youth Care Forum 40(2):93–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9125-3

Ginsburg GS, Becker EM, Keeton CP, Sakolsky D, Piacentini J, Albano AM, Compton SN, Iyengar S, Sullivan K, Caporino N, Peris T, Birmaher B, Rynn M, March J, Kendall PC (2014) Naturalistic follow-up of youths treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiat 71(3):310. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4186

Goodwin GM (2015) The overlap between anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 17(3):249–260

Grados MA, Leung D, Ahmed K, Aneja A (2005) Obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: a common diagnostic dilemma. Primary Psychiatry 12(3):40–46

Group (2002) The pediatric anxiety rating scale (PARS): development and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41(9):1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006

Holmes MC, Donovan CL, Farrell LJ (2015) A disorder-specific, cognitively focused group treatment for childhood generalized anxiety disorder: development and case illustration of the No Worries! program. J Cogn Psychother 29(4):275–301. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.29.4.275

Hudziak JJ, Althoff RR, Stanger C, Beijsterveldt CEM, Nelson EC, Hanna GL, Boomsma DI, Todd RD (2006) The obsessive-compulsive scale of the child behavior checklist predicts obsessive-compulsive disorder: a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47(2):160–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01465.x

Insel TR (2014) The NIMH research domain criteria (RDoC) project: precision medicine for psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 171(4):395–397. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020138

Ivarsson T, Melin K, Wallin L (2008) Categorical and dimensional aspects of co-morbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(1):20–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-007-0626-z

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(7):980–988. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

Kendall PC, Brady EU, Verduin TL (2001) Comorbidity in childhood anxiety disorders and treatment outcome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(7):787–794. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200107000-00013

Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C (2008) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: a randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. J Consult Clin Psychol 76(2):282–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282

Kendall PC, Compton SN, Walkup JT, Birmaher B, Albano AM, Sherrill J, Ginsburg G, Rynn M, McCracken J, Gosch E, Keeton C, Bergman L, Sakolsky D, Suveg C, Iyengar S, March J, Piacentini J (2010) Clinical characteristics of anxiety disordered youth. J Anxiety Disord 24(3):360–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.009

Kessler RC, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Wittchen HU (2010) Epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2:21–35

Krebs G, Isomura K, Lang K, Jassi A, Heyman I, Diamond H, Advani J, Turner C, Mataix-Cols D (2015) How resistant is ‘treatment-resistant’ obsessive-compulsive disorder in youth? Br J Clin Psychol 54(1):63–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12061

Langlois F, Freeston MH, Ladouceur R (2000) Differences and similarities between obsessive intrusive thoughts and worry in a non-clinical population: study 2. Behav Res Ther 38(2):175–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00028-5

Lewinsohn PM, Zinbarg R, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn M, Sack WH (1997) Lifetime comorbidity among anxiety disorders and between anxiety disorders and other mental disorders in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 11(4):377–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(97)00017-0

de Lijster JM, Dierckx B, Utens EMWJ, Verhulst FC, Zieldorff C, Dieleman GC, Legerstee JS (2017) The age of onset of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry Revue Can Psychiatrie 62(4):237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716640757

Masi G, Millepiedi S, Perugi G, Pfanner C, Berloffa S, Pari C, Mucci M, Akiskal HS (2010) A naturalistic exploratory study of the impact of demographic, phenotypic and comorbid features in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychopathology 43(2):69–78. https://doi.org/10.1159/000274175

Merikangas KR, He J-P, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J (2010) Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(10):980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

Micali N, Heyman I, Perez M, Hilton K, Nakatani E, Turner C, Mataix-Cols D (2010) Long-term outcomes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: follow-up of 142 children and adolescents. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 197(2):128–134. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075317

Milne JM, Garrison CZ, Addy CL, McKeown RE, Jackson KL, Cuffe SP, Waller JL (1995) Frequency of phobic disorder in a community sample of young adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34(9):1202–1211. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199509000-00018

Nestadt G, Samuels J, Riddle MA, Liang K-Y, Bienvenu OJ, Hoehn-Saric R, Grados M, Cullen B (2001) The relationship between obsessive–compulsive disorder and anxiety and affective disorders: results from the Johns Hopkins OCD Family Study. Psychol Med 31(3):481–487. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701003579

Ohara K, Suzuki Y, Ochiai M, Tsukamoto T, Tani K, Ohara K (1999) A variable-number-tandem-repeat of the serotonin transporter gene and anxiety disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 23(1):55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-5846(98)00091-8

Peris TS, Rozenman M, Bergman RL, Chang S, O’Neill J, Piacentini J (2017) Developmental and clinical predictors of comorbidity for youth with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 93:72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.05.002

Piacentini J, Bennett S, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Albano AM, March J, Sherrill J, Sakolsky D, Ginsburg G, Rynn M, Bergman RL, Gosch E, Waslick B, Iyengar S, McCracken J, Walkup J (2014) 24- and 36-week outcomes for the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53(3):297–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.010

POTS Team (2004) Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the pediatric OCD treatment study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 292(16):1969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.16.1969

Premo JE, Liu Y, Bilek EL, Phan KL, Monk CS, Fitzgerald KD (2020) Grant report on anxiety-CBT: dimensional brain behavior predictors of CBT outcomes in pediatric anxiety. J Psychiatry Brain Sci 5:e200005. https://doi.org/10.20900/jpbs.20200005

Riddle MA, Scahill L, King R, Hardin MT, Towbin KE, Ort SI, Leckman JF, Cohen DJ (1990) Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: phenomenology and family history. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29(5):766–772. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199009000-00015

Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC (2010) The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry 15(1):53–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2008.94

Saad LO, do Rosario MC, Cesar RC, Batistuzzo MC, Hoexter MQ, Manfro GG, Shavitt RG, Leckman JF, Miguel EC, Alvarenga PG (2017) The child behavior checklist—obsessive-compulsive subscale detects severe psychopathology and behavioral problems among school-aged children. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 27(4):342–348. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2016.0125

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S (1983) A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 40(11):1228–1231. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010

Sharma P, Rosário MC, Ferrão YA, Albertella L, Miguel EC, Fontenelle LF (2021) The impact of generalized anxiety disorder in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Psychiatry Res 300:113898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113898

Siegel RS, Dickstein DP (2012) Anxiety in adolescents: update on its diagnosis and treatment for primary care providers. Adolesc Health Med Ther 3:1–16. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S7597

Stengler K, Olbrich S, Heider D, Dietrich S, Riedel-Heller S, Jahn I (2013) Mental health treatment seeking among patients with OCD: impact of age of onset. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48(5):813–819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0544-3

Storch EA, Larson MJ, Merlo LJ, Keeley ML, Jacob ML, Geffken GR, Murphy TK, Goodman WK (2008) Comorbidity of pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder and anxiety disorders: impact on symptom severity and impairment. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 30(2):111–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-007-9057-x

Tallis F, de Silva P (1992) Worry and obsessional symptoms: a correlational analysis. Behav Res Ther 30(2):103–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(92)90132-Z

Turner C, O’Gorman B, Nair A, O’Kearney R (2018) Moderators and predictors of response to cognitive behaviour therapy for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res 261:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.034

Turner SM, Beidel DC, Stanley MA (1992) Are obsessional thoughts and worry different cognitive phenomena? Clin Psychol Rev 12(2):257–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(92)90117-Q

Verduin TL, Kendall PC (2003) Differential occurrence of comorbidity within childhood anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 32(2):290–295. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_15

Voltas N, Hernández-Martínez C, Arija V, Aparicio E, Canals J (2014) A prospective study of paediatric obsessive–compulsive symptomatology in a Spanish community sample. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45(4):377–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0408-4

Weidle B, Jozefiak T, Ivarsson T, Thomsen PH (2014) Quality of life in children with OCD with and without comorbidity. Health Q Life Outcomes 12(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0152-x

Whiteside SPH, Sim LA, Morrow AS, Farah WH, Hilliker DR, Murad MH, Wang Z (2020) A Meta-analysis to guide the enhancement of CBT for childhood anxiety: exposure over anxiety management. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 23(1):102–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00303-2

Zinbarg RE, Barlow DH (1996) Structure of anxiety and the anxiety disorders: a hierarchical model. J Abnorm Psychol 105(2):181–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.105.2.181

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health under Grant 5R01MH107419-05.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR and HB contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript. AI provided statistical support. All authors carefully reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

This work was conducted in compliance with the Michigan Medicine Institutional Review Board (HUM00118950). All participants and respective guardians provided informed assent/consent to participate.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rueppel, M., Becker, H.C., Iturra-Mena, A. et al. Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms: Baseline Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Implications in a Clinically Anxious Pediatric Sample. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01658-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01658-y