Abstract

Heightened academic stress in the final years of schooling is a common concern, yet little is known about how stress changes over time and what individual, school and family factors are associated with distress. We conducted a systematic review to examine the nature of distress in students in their final two years of secondary school. Sixty studies were eligible for inclusion. The main findings indicated severity of distress differed across the 17 countries sampled and measures used. There was some consistencies suggesting about 1 in 6 students experienced excessive distress. Female gender and anxiety proneness were consistently associated with increased distress, and freedom from negative cognitions with reduced distress. There was some evidence that individual characteristics (perfectionism, avoidance, coping, self-efficacy, resilience), lifestyle (sleep, homework), school, family and peer connectedness were associated with distress. Overall at-risk students can be predicted by theoretical models of anxiety and distress targeted with psychological interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Academic stress is a common concern for youth; with tests, homework and grades being the biggest stressors reported by secondary school students [1, 2]. Academic stress in the final years of high school has received particular attention and has been found to be associated with very high levels of distress in large samples in Australia [e.g. 3], the Netherlands [4], the United Kingdom [e.g. 5], and the United States of America [6]. In these countries and others (e.g. broader Europe, East and South Asia, Canada) the final year or two years of school involves a series of examinations and the performance on these examinations forms the basis for an educational certificate, pre-university program, or university entrance scores. Due to the large contribution of examination performance on the overall mark (for example over 50% in Australia), these examinations are often referred to as high stakes tests, and these examinations seem to be particularly relevant to increased levels of stress reported by students [7,8,9].

Although there are many reports of heightened levels of distress in students in the final years of secondary school, little is known about the nature of this distress, whether it is excessive and what individual, school-based or family factors exacerbate or lessen this distress. This is an important issue for educators who are responsible for the wellbeing of students, but also because research indicates that heightened distress can impede academic performance [10]. It is also unclear whether the distress is limited to the examinations per se, or is associated with other factors such as increases in workload, increased expectations for independence in learning, or personal, family or other school based factors. This is particularly unclear as most research has examined distress using measures of test anxiety. Although test anxiety refers to a fear of completing tests or exams [11]; common measures of test anxiety have been shown to capture anxiety more broadly with high scores overlapping with anxiety disorders (such as generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia), trait anxiety and general anxiety proneness [for reviews see: 12, 13]. It is therefore not clear whether the high levels of test anxiety found in senior school samples [e.g. 5] relates to examinations specifically, or perhaps reflects general high levels of distress associated with the academic pressures of the final years of schooling more broadly, or in fact, predominantly capture students with likely anxiety disorders.

Developmental models of psychopathology suggest biological by environment interactions play an important role in distress during the adolescent period [14, 15]. Environmental stressors associated with senior school and high stakes examinations may interact for biologically vulnerable students to exacerbate or trigger underlying stress vulnerability. These factors might be school based (e.g. increased learning requirements, pressure to perform), home based (e.g. pressure to perform, diet, sleep routines), peer group based (e.g. social evaluation concerns, social contagion of stress) or other. Developmental models of child anxiety [16, 17] highlight the role of individuals’ cognitive and behavioural responses to these stressors, as well as parental responses, in exacerbating or reducing the perceived threat of these environmental stressors. With adolescent distress showing clear trajectories for adult mental disorders [15], it is important to better understand the nature of the distress experienced by senior school students.

Given the importance of understanding the factors associated with heightened distress in senior students, the aim of this review was to examine the literature in order to understand the severity of the distress experienced by students in the final years of secondary school, how distress changes over time, and to understand the factors that contribute to or protect students from excessive distress. To the best of our knowledge this is the first review to examine this issue.

Method

Search Strategy and Selection of Studies

A systematic literature search was carried out using the Psycinfo (American Psychological Association) 1806 to April 2018 and Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC; Institute of Education Sciences) 1966 to April 2018 databases as they were considered to be the most relevant for the topic. The reference lists of relevant articles were also used to source additional articles relevant to the review. Keywords selected for the search terms were related to hypothesised predictors and outcomes of stress in final year high school students. The final search included terms related to high school (high school, secondary school, senior school, HSC, high school certificate), distress (anxiety, anxious, test anxiety, fear, stress, distress, coping, burnout, resilien$), and academic-related stress (exam$, examination$, test$, academic pressure, academic hardiness, academic buoyan$, fear appeal, perfectionis$).

Eligible articles were: published in English in peer-reviewed journals, reported distress or emotional wellbeing variables as related to academic stress in high school students in their final two years of schooling (e.g. Grade 10/11, 11/12, 12/13 depending on the country). For studies that included a broader school grade range they were included if they reported subgroup analyses related to senior students in the final two years of schooling. Articles were excluded if they primarily examined scale psychometrics, or were focused solely on special populations unrepresentative of the general population (e.g. deaf students, students with cystic fibrosis) and were not specifically related to understanding the distress associated the final years of school. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included.

Data Extraction and Analysis

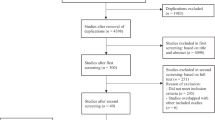

All articles retrieved from the database searches were uploaded into citation management software, EndNote. Duplicates were removed automatically. The inclusion and exclusion of articles based on their title, then abstract, then full-text was overseen by two authors (VA, TJ) with discrepancies discussed with VW. In addition, references from retrieved papers were checked for relevant studies. A total of 60 articles were eligible for the current systematic literature review. Data pertaining to the sample (participants, age, gender, type of school, country), study method (qualitative, quantitative, measures used, timing of measurement), and outcomes (ranges and means on relevant distress measures, relationships between key variables) were extracted. Quantitative data on mean distress scores over time on the same outcomes measures were used where possible to calculate overall mean distress for the total sample. Other findings were pooled to form a narrative review of the findings. Figure 1 outlines the search and selection process based on the PRISMA guidelines [18]. Table 1 summarises the studies included in the review.

The quality of the studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Cohort Study checklist [19] and Qualitative Study checklist [20]. The CASP checklists do not provide a scoring system so instead each study was rated against each of five study quality criteria as meeting/not meeting the criteria or rated as unclear. For Cohort studies the quality criteria were: (1) examined a focused issue, (2) appropriate sample, (3) unlikely measurement bias, (4) appropriate design/confounds considered, and (5) appropriate analysis/interpretation of results. Similarly, for Qualitative Studies the quality criteria were: (1) clear aims, (2) appropriate sample, (3) appropriate methodology, (4) confounds considered, (5) appropriate analysis/interpretation of results. Quality was assessed by two raters (VW, TJ) and disagreements were solved through discussion. See Table 2 for the quality ratings.

Results

Sixty articles were found that met eligibility criteria (see Table 1). They reported on qualitative and quantitative studies that investigated the distress experienced by students in the final two years of schooling as well as the factors that influenced their distress.

Study Characteristics

Studies were conducted across 17 countries: Australia (n = 12), United Kingdom (n = 15), Turkey (n = 11), United States of America (n = 7), Canada (n = 3), the Netherlands (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Brazil (n = 1), Nigeria (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), Malaysia (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), India (n = 1) and one study that compared cohorts in USA and Korea. Methodologies varied across studies: five studies used a longitudinal design, 55 were cohort studies, and five used qualitative analyses.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the 60 included studies varied considerably (see Table 2). Only 26 studies were rated highly on all categories. Most studies reported a clear study aim or described a focused issue of study. Most studies also had adequate samples for the study aims. Measurement bias was not a concern in the qualitative studies, with the risk of measurement bias mixed for the cohort studies, with common concerns related to the reliability and validity of measures used. Confounds were considered in only some studies, in particular confounds related to differences in timing of measurement in relation to the exams, differences in schools or students sampled were often ignored. Finally, the use of appropriate analysis and interpretation of results was consistently better in the qualitative studies, with very mixed quality ratings in the cohort studies. In consolidating the findings across studies, more emphasis is placed on the findings from the higher quality studies.

Outcomes

Distress Increases Over the Senior School Period

Cohort Studies

Comparisons between student cohorts across different grades generally found that the final year of high school was associated with more distress than the penultimate year [21, 22], and the penultimate year was associated with more distress than the earlier years [23,24,25,26] suggesting that distress is likely to increase through the senior years. Although the majority of studies found increased distress in later school years, not all did [e.g. 27, 28], and this may relate to differences in the timing of assessments or perceived stakes of the assessments. For example Locker and Cropley [28] assessed UK students in year 11 and year 9 twice, both at the same time prior to major exams and found no differences in distress. Therefore students might find all examination periods equally distressing (regardless of school year). However, it is important to note likely cohort effects between groups studied, as well as differences in the timing and type of distress measurement particularly in terms of the proximity and types of upcoming examinations. Longitudinal studies with repeated measurement in the same sample are needed to understand changes in distress over time.

Longitudinal Studies

Five studies sampled distress in the same students throughout the final year, with most finding increases in distress as major examinations approached [29,30,31,32,33], and decreased distress after the examination period [30]. Einstein, Lovibond and Gaston [29] measured distress using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales [DASS; 34] in Australian year 12 students on two occasions prior to upcoming major examinations; 10 weeks prior and again 10 days prior to the same exam period. They found mean student distress increased significantly from the first testing to the second testing from: moderate to severe anxiety, from severe to extremely severe stress, and remained in the severe range (but significantly increased) from first to second testing for depression. Similarly, Smith, Sinclair and Chapman [32] administered the DASS to 63 Australian students in February (term 1 year 12) in and again in August (term 3) just before the major trial examinations. Students’ group means for DASS measured stress, anxiety and depression increased significantly overall between the two testing occasions from mild to moderate depression, from mild to moderate anxiety; however, remained at a mild level for stress across both occasions.

Similar findings were found by Peluso et al. [31] in 154 Brazilian students using the Positive and Negative Affect Scale [PANAS; 35] administered three times during the last year of high school. They found negative affect scores increased over time, with no significant change in positive affect scores. Lay et al. [30] also found that mean state anxiety scores significantly increased from seven days prior, to one day prior to exams, and then decreased five days after the exam period in final year students in Canada. In contrast, Locker and Cropley [28] found no significant increases in distress in a sample of students in four UK high schools from six to eight week prior to exams, to one week prior to exams on the PANAS [35], Children’s Depression Inventory [CDI; 36], Revised Manifest Anxiety Scale [RCMAS; 37], or Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [38]. Although it is important to note that there was 21% attrition between the two testing periods and this may have led to missing data at the higher distress levels. In general studies have shown that stress is heightened in the senior years compared to lower years and increases in the lead up to the major exam period.

Severity of Distress

Across a wide range of measures and countries, most studies reported that students had high levels of distress with stronger similarities across samples when the same measure was used in the same country (see Table 1). Determining how “high” the distress was across the samples is difficult to ascertain as studies differed in the cut-offs used to define high distress, with many applying cut-offs from adult normative samples. For example interpretation of scores on the TAI were based on normative data from college students collected 40 years ago, and recent research suggests these cut-offs are out of date for college students [39]. Similarly, interpretation of scores on the DASS was based on normative data developed in adult samples, and despite its wide spread use with adolescents, there are no adolescent norms available. Further, although the three factor structure of the DASS (depression, anxiety, stress) has been generally supported in adolescent samples with minor modifications [40, 41], it has not consistently been supported [42], and so caution is needed in interpreting the results. It is also difficult to determine if the distress levels reported across studies related to distress prior to an examination or general distress across the senior school period. Studies differed in the timing of distress measurements to major examinations and timing was often was not reported.

Due to the range of measures used, comparisons between studies are difficult; however, the TAI was used in nine studies and the DASS in five studies enabling some comparisons across studies to be made. Across the nine studies that used the TAI (most from the UK), distress was consistently reported to be high in final year students [e.g. 5]; however, different authors used different definitions for “high” test anxiety. In the largest study, Putwain and Daly [5] administered the TAI to 2435 students from 11 UK secondary schools in the final two years of schooling (years 10 and 11; with a small sample in year 9 who were being accelerated) in the lead up to the final exam period. High test anxiety was defined as scoring in the top 1/3rd of the score range, that is students who reported experiencing anxiety somewhere from “often” to “almost always”. Using this definition, they found 16.4% reported high test anxiety, with females reporting significantly higher test anxiety than males (22.5% vs 10.3%). It is not clear whether the 16% of students reporting high levels of test anxiety is significantly more than in other years. Similar findings were reported by the other studies using the TAI.

Five studies (all Australian) reported on student levels of depression, anxiety and stress using the DASS [34] in either its full (42 item) or shortened (21 item) form [3, 9, 22, 29, 32]. In adult samples, scores can be interpreted as normal, mild, moderate, severe or extremely severe, with the severe and extremely severe categories suggestive of clinical levels of distress [34], although it is not known whether these cut-offs are applicable to adolescent samples. Robinson, Alexander, and Gradisar [9] sampled 195 final year (year 12) students in South Australia one month prior to the exams and found that male and female students (respectively) reported levels in the likely clinical range (severe or extremely severe on the DASS-21) for: depression (15%, 22%), anxiety (11.7%, 29.9%) and stress (18.3%, 22.3%). This is similar to the findings by McGraw, Moore, Fuller, and Bates [3] who surveyed 941 final year students (year 12) in term 3 in Victoria Australia and found the proportion of students who reported distress in the likely clinical range (severe or extremely severe on DASS-21) for: depression was 12.1%, anxiety (20.9%), and stress (11.3%). Smith and Sinclair [22] also measured DASS scores in term 3 for year 11 and year 12 students in New South Wales, Australia, and found the proportion of students reporting severe to extremely severe levels in the two cohorts (Year 11, Year 12) being: 12.5% vs 24% for stress, 11% vs 19% for anxiety and 13% vs 24% for depression with clear increased distress in the final year students.

Averaging across the five studies, final year (year 12) students’ mean level of distress likely to be in the clinical range (severe or extremely severe) was for stress 17.77% (means ranged from 11.39 to 21.07%), for anxiety 21.03% (means ranged from 17.90 to 24.30%), and for depression 18.12% (means ranged from 12.10 to 22.42%). Averaging the mean score across the scales, 19% of students reported distress in the severe to extremely severe range (as per adult norms). This is similar to the average of 16% with reported high test anxiety across 11 UK schools in the Putwain and Daly [5] study reported above. So about 1 in 6 final year students is likely to have very high levels of distress which might be of clinical concern.

The other studies examined distress severity using a range of other self-report symptom scales and generally reported high proportions of distress in the student samples (in most cases as indicated against adult norms). Two studies [21, 43] used the Global Health Questionnaire [GHQ: 44] in its full and short (12 item) form. Hodge, McCormick and Elliott [21] applied a conservative clinical cut-off (≥ 8) on the GHQ 30 item version to Year 11 and Year 12 students in New South Wales Australia and found 42.4% Year 11 and 56.7% Year 12 students reported distress in the clinical range (based on adult norms). Similarly, Lin and Yusoff [43] found 48% of senior students in Melaka scored in the clinical range on the GHQ 12 item (using a cut off of ≥ 4). One study examined depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9: 45] and found 26% of final year students in North-East USA scored above the clinical cut off of 10 based on adult norms [6], and one study used the Beck Depression Inventory Revised [BDI-R: 46] and reported 45% of a Turkish sample were in the clinical range for depression (based on adult norms using a cut off of > 16) two months prior to their major examinations [47]. Only three studies used a scale developed for children, the Children’s Depression Inventory [36], and the one study that reported scores in relation to clinical cut offs found that 36% of final year Korean students were above the cut-off for clinical depression, compared to 16% of American students [48]. Across these other measures the proportion of students experiencing very high distress ranged from 16 to 57% although the majority used normative cut-offs based on adult samples and so may not accurately reflect clinical distress.

Factors Associated with Increased Distress

Across the studies there was evidence that demographic, individual, family and school factors were associated with increased distress in students in the final two years of school.

Demographics

Demographic factors such as gender (discussed below), low socioeconomic status and studying in a second language were found to be associated with increased student distress in the final years of school although when reported the effect sizes for these effects were very small and difficult to differential as a range of demographic variables were often lumped together. Four studies [21, 27, 49, 50] found a significant difference in distress associated with lower socioeconomic status in Australia, United Kingdom and Portugal, but not Melaka [43], with only two studies reporting the unique variance of this effect as very small (R-squared change = 0.06–0.006 [21, 50]. Five studies (in Australian, UK and USA samples) found increased distress related to coming from a non-English speaking background [21, 29, 49,50,51], but not all [52], again with very small effects (R-square change = 0.002) [e.g. 21]. Three studies examined the impact of parental education and found no effect [9, 43, 53]; however, a protective effect was found for higher status of parental occupation in the UK [52] and Nigeria [54], but not in Melaka [43]. Other demographic effects were examined in only one or two studies making conclusions difficult. Birth order was not associated with distress [9]; however, having a sibling was associated with significantly reduced distress [55]. No effect was found for parental marital status [43] whilst one found an effect of parent divorce on males anxiety but not females [53], and increased anxiety in females with household stress but not males [53]. One study compared final year students living in Korea to students living in America and found that the Korean students had significantly higher depression [48].

Individual Differences

The relationship between distress and individual factors were investigated. The strongest evidence related to female gender, anxiety proneness and freedom from negative thoughts with emerging evidence for: perfectionism, academic buoyancy, student motivation and coping, hours of study and sleep.

Gender

Females reported significantly higher distress in the final years of high school than males across a wide range of distress measures and samples [3, 9, 13, 21, 22, 27, 28, 30, 52, 53, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. Overall, in the senior school samples females consistently had higher scores for anxiety symptoms than males [3, 22, 28, 53, 64, 65]. Similarly, females also had higher test anxiety scores across a range of senior school samples such as in the UK [5, 13, 50, 52], in Chinese students [58], American students [64, 65], Greek students [61], Iranian students [60], Portuguese students [27], Turkish students [56, 57, 62, 63, 66], but in one study male and female Nigerian students did not differ significantly on test anxiety [54]. Females had higher depression scores than males in some samples [22], but not in others [3, 28]. Females also had higher scores for DASS stress [3, 22]. These findings could relate to the higher emotionality of females and higher prevalence of anxiety (and depressive) disorders in adolescent female samples [67, 68], or gender differences in willingness to report emotional distress.

Anxiety Proneness

It was consistently found that greater distress in the final years of school was associated with or predicted by higher trait anxiety suggesting anxious prone students are more likely to experience distress. For example, higher state trait anxiety was found to predict 58% of variance in distress (measured on the GHQ) in senior students over and above demographics, school type, coping and gender [21]. Similarly, negative affect was shown to predict higher test anxiety in senior school students in New Zealand [69]. Studies have also reported that high test anxiety, which is a measure of trait anxiety [11] and hence anxiety proneness is associated with increased distress, lower self-efficacy and self-esteem in final year students [54, 56, 70], and lower examination performance [10, 71, 72]. Therefore, anxiety proneness is likely to be a significant predictor of senior school distress.

Negative Cognitions

Qualitative and quantitative studies across a number of different countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, Italy, Turkey, Melaka, United Kingdom, United States of America) found heightened distress in the final years of school was strongly associated with negative cognitions, fear of failure, fear of examinations, homework concerns and fear of not getting into university [6, 8, 30, 43, 73,74,75,76,77]. The significance of negative cognitions was particularly highlighted in a study of 195 year 12 students in South Australia [9], in which 12 internal and external factors associated with resilience were examined. In females, freedom from negative cognitions was the largest predictor of resilience to depression, anxiety and stress, with family connectedness and confidence also being important. For males, freedom from negative cognitions, confidence, family, peer and school connectedness were significant predictors of resilience.

Negative cognitions in test anxiety have also been shown to be strongly associated with distress. Test anxiety has been conceptualised as having a cognitive component (e.g. worry about failure) and an affective-physiological component (e.g. somatic symptoms of anxiety) [78]. The cognitive component of test anxiety has been specifically found to be associated with test performance in a range of studies [10, 50, 51, 79, 80], with higher scores being predictive of poorer test performance on major exams in senior students from the UK, New Zealand, USA, India, and Turkey [10, 50, 57, 69, 80, 81]. In a large study, 705 UK students in the final year of school (Year 11) completed measures of test anxiety and academic buoyancy (see below) four months prior and again two months prior to the final exams [10]. The worry component of test anxiety at baseline was associated with lower exam performance four months later. Similar findings in a number of UK studies have shown negative cognitions mediate the relationship between test anxiety and examination performance [79, 82]. Therefore, heighted negative cognitions and worry about tests appears to be particularly associated with student distress as well as reduced examination performance.

Perfectionism

Theoretically, perfectionism is conceptualised as having dimensions incorporating cognitions and behaviours associated with a need to do things perfectly [83, 84]. Hewitt and Flett [84] described perfectionism as being driven by personal desires for high standards for the self (self-oriented), for others (other-oriented), or a perception that others hold unrealistic standards for one’s behaviour (socially-prescribed). Perfectionism can be adaptive (high standards without excessive negative self-evaluation) or maladaptive (high standards coupled with excessive negative self-evaluation) and maladaptive perfectionism has been associated with distress and psychopathology [83]. A small number of studies have examined the impact of perfectionism on student distress in the final years of high school, and have generally found that higher levels of perfectionism were associated with increased distress and test anxiety [63, 85], mirroring findings in university students [86]. In an Australian sample, Einstein et al. [29] found socially-prescribed perfectionism (perceived perfectionistic standards expected by others e.g. parents) was associated with increased distress, but self-oriented and other-oriented perfectionism were not. Therefore, there is some evidence that perfectionistic standards which result in negative evaluation of self or perceived negative evaluation by others, is associated with increased distress in students. As discussed above, it is likely that the negative cognitions that drive maladaptive perfectionism are an important component in student distress, and more research is needed to examine this further.

Coping

Students who reported using more avoidant or non-adaptive coping styles (wishful thinking, self-blame, suppression) had higher distress and test anxiety scores [21, 30, 43, 66, 76, 87], with adaptive coping (problem solving, task orientation, reappraisal) associated with lower distress [21, 76, 81, 87]. Further, Italian final year students who reported decreased beliefs about their ability to cope with upcoming examinations had the highest distress [76]. These findings mirror other research showing that maladaptive coping, particularly avoidance, is associated with increased distress and psychopathology generally [88].

Motivation

Four studies looked at the impact of student motivation to approach or avoid performance tasks on distress severity in the final years of school. A performance-approach goal refers to the motivation to outperform peers, whereas a performance-avoidance goal refers to motivation to avoid demonstrating lack of ability. Smith and Sinclair [22] looked at the impact of performance-approach goal orientation, performance-avoidance goal orientation, as well as self-efficacy and self-handicapping coping strategies on levels of depression, anxiety or stress in year 11 and 12 students. They found higher performance-avoidance goal orientation was associated with higher depression and anxiety in year 11 males, and anxiety and stress in year 12 males, and depression in year 12 females. Similarly, Putwain and Symes [89] also found in 273 final year UK students that higher test anxiety was associated with more performance-avoidance and mastery-avoidance (avoidance of increasing competence). In a sample of Indian students in their penultimate year of high school, those who reported higher test anxiety also indicated poorer study habits and using self-handicapping coping strategies [80]. These findings are similar to the findings above related to greater distress being associated with using avoidance as a coping strategy, as well as negative beliefs about their ability and the consequence of poor performance.

Academic Self-efficacy

In qualitative interviews students reported that stress in the senior years related specifically to how confident and competent they felt about specific subject matter [8], with higher confidence in their competence for exam and assessment tasks relating to lower distress. The relationship between higher academic confidence and lower distress was also found in quantitative studies; Higher self-efficacy was associated with lower test anxiety scores in American [70], Australian [9], and Turkish senior school students [55], as well as higher self-esteem in Nigerian [54] and Turkish senior students [56] and lower depression levels in Canadian senior students [85]. However, test competence was not a significant predictor of unique variance in examination performance when tested in a model also containing test worry, academic buoyancy and perceived control, suggesting that it is test related worry that is most relevant [82].

Academic Buoyancy

Academic buoyancy is defined as the capacity to withstand routine types of academic setbacks, challenges, and pressures experienced by students during their education such as dealing with competing deadlines, poor grades and examination pressure [90]. It has been shown to be comprised of higher self-efficacy, higher planning ability, greater beliefs about control, persistence and low anxiety [91], and therefore includes many of the elements discussed above. Given that, it is perhaps not surprising that academic buoyancy has been found in a number of studies to be associated with lower test anxiety and distress, greater enjoyment of school, class participation, self-esteem, and better examination performance [10, 81, 87, 90, 92, 93]. Although academic buoyancy was found to explain unique variance (5–10%) in test anxiety in senior school students over and above coping [87], when the role of academic buoyancy was considered in conjunction with other predictors of examination performance, only worry about tests (strongest predictor) and perceived control (smaller predictor) were significant predictors of unique variance, with academic buoyancy and test competence being non-significant [82]. Therefore, academic buoyancy is an important concept in understanding senior school distress; however, it is unclear what the relationship is of academic buoyancy to the other main predictors of senior school distress such as the absence of negative cognitions and anxiety proneness, and further studies are needed to understand the specific and unique contribution of academic buoyancy on student distress.

Time Spent Studying

Four studies examined the relationship between the number of hours spent studying and student distress and found that more hours studying was associated with greater distress and negative mood [31, 48, 59, 94]. However, the causal relationship between distress and time spent studying is not clear. In an interesting cultural comparison, Lushington et al. [59] found the relationship between greater hours of study and greater distress was only evident in Caucasian-Australian senior students and not in Asian-Australian senior students, and that hours of study only related to stress levels and not depressed mood. Lee and Larson [48] found that increased time spent on homework was only related to increased depression in those students (Korean and American) who experienced increased negative affect during homework. This suggests that students’ attitudes or negative cognitions towards or during homework might be a mediating factor between hours of study and distress. Lee and Larson [48] also found that more time spent in active leisure was associated with reduced depression, suggesting that it might not be the amount the number of hours spent studying specifically, but the portion of hours studying compared to hours spent doing pleasant (mood enhancing) activities. Interestingly, a study with Turkish senior students found that poorer time management when completing school assignments was associated with increased anxiety [95]. More research is needed to understand the relationship between study time and distress, and to examine individual differences in study patterns, emotional wellbeing and academic performance.

Sleep

Three studies examined the relationship between sleep and stress in final year students and found links between increased stress and poorer sleep. In a small sample (n = 24) in the Netherlands, stress experienced in the final examination period was found to be associated with significantly reduced total sleep time (17.5 ± 8.2 min), sleep efficiency and increased wake bouts [96]. Similarly, in a large (n = 195) Australian sample final year students one month prior to their final exams reported high rates of inadequate sleep, with more distressed students reporting greater rates of daytime napping [9]. Also Lushington et al. [59] found that 20% of students (n = 398) had missed class in the previous month because they had overslept, and that increased daytime sleepiness was associated with increased stress and depressed mood. Across the studies, it is not clear whether sleep is a predictor of distress or a consequence of distress. Both are likely true as there is clear evidence that inadequate sleep is associated with increased anxiety and depressed mood [97,98,99], as well as anxiety and depression being associated with poorer quality sleep and fatigue [100, 101]. More research is needed to understand the link between distress and poor sleep in senior students, what role excessive study might play in the reduced hours of sleep, and whether it is chronic or acute sleep deprivation that is most significant.

Family, Peer and School Factors

The evidence related to the impact of school type, family, peer and school connectedness, perceived pressure, and fear appeals are examined in relation to distress in senior students.

Type of School

In general no significant differences were found in distress levels across different school types or boarding compared to day students [6, 62]. Two studies found significantly higher mean anxiety scores in single sex girls’ schools compared to coeducational and single six boys’ schools [25, 28], and one also found single sex girls’ schools had significantly greater negative affect scores [28]. This school type effect is likely to be accounted for by the findings that females scored higher on anxiety and depression measures, rather than the school type specifically. One Turkish study reported school based differences in test based anxiety [56]; however, how the school types differed was not clearly described and so it is difficult to draw conclusions. In general it appears that school based differences are minor, with the main differences related to single sex girls’ schools having higher distress, which likely reflects the strong effect of female gender on distress, although further research is needed to understand if female gender coupled with an all-female school environment increases the distress.

Family, Peer and School Connectedness

Student distress varied by how strongly connected students felt with their schools (sense of belonging to their school community), their peers (satisfaction with peer relationships) and with their family (satisfaction with care and support from family, family cohesion). All five studies found that a more positive relationship with school was associated with reduced distress in final year students [3, 9, 26, 63, 102]. Strong peer connectedness was also shown to be associated with reduced distress. For example, in a large study of 941 Year 12 Australian students in their final year of school, McGraw et al. [3] found after controlling for gender that connection with school, peers and family were associated with reduced depression (accounting for 42% of the variance), with the strongest predictor being connection with peers. Male gender, peer connectedness and family connectedness were all significant protective factors for anxiety and stress (explaining 21–22% of the variance respectively), with peer connectedness again being the strongest protective factor. Peer connectedness was also related to increased resilience in an Australian sample [102]. In Turkish senior students, perceived support from peers (and teachers) was associated with less test anxiety [63]. Robinson et al. [9] also found that peer, school and family connectedness were predictive of resilience to distress in males in the final year of school, while only family connectedness (and not peer or school connectedness) was protective of distress in female students. In an American sample, students in higher grades reported lower school connectedness and higher anxiety than younger students [26]. Therefore, a strong sense of connectedness with the school, family and peers is important for reduced distress in senior students.

Fear Appeals and Perceived Pressure

Fear appeals refer to attempts by teachers (or parents) to motivate students by highlighting the consequences of failing or doing poorly [103]. The impact of fear appeals on students’ levels of distress and on subsequent examination performance has been mixed and differs depending on how students’ interpret the fear appeals. For example, in a sample of 132 UK students in their final two years of schooling, fear appeals by teachers to year 10 students (penultimate year of high school) were found to be associated with increased worry and tension related to their major mathematics exam later in Year 11, but this was only true for students who perceived the fear appeals to be threatening [103]. For other students, perceived threat from fear appeals in year 10 was associated with increased fear of failure but also an increased motivation to improve their competence (mastery-approach), hence the fear appeals helped to increase their commitment to study. Similarly, in a sample of 273 final year UK students, Putwain and Symes [89] found that fear appeals by teachers that were perceived as threatened associated with a greater performance-avoidance approach, and resulted in poorer examination performance. Although research recently found that when fear appeals were used more frequently, the tendency to appraise them as threatening increased [104], with related research in university students suggesting that efficacy appeals (instead of fear appeals) resulted in reduced distress and increased examination performance [105]. More research is needed to understand the links between fear appeals, threat perception, and examination performance. The emerging research that efficacy appeals might produce better emotional outcome and test performance is particularly important.

Similarly, qualitative studies found students with perceived pressure from parents, teachers and peers reported higher distress [6, 8, 73, 75]. Çırak’s [73] study in Turkish senior students identified that the pressure from parents related to a desire by students to not disappoint their parents who had often made significant sacrifices to give them an educational opportunity. As reported earlier, Einstein et al. [29] found that higher socially-prescribed perfectionism, which captured perceived pressure to achieve unrealistic goals determined by significant others, was a significant predictor of distress (depression and anxiety) in final year students prior to a set of major exams. Therefore the findings suggest that perceived pressure by teachers to do academically well is predictive of heightened distress in the final years of school and mediated the impact on student distress and examination performance.

Discussion

This review aimed to understand the nature of, severity of, and correlates of distress in secondary students undergoing the final years of schooling. The global interest in this topic was demonstrated by studies represented student samples from 16 different countries, with the majority reporting high levels of distress in students. There was evidence that distress increased as examination periods approached, however, it is unclear whether the severity of distress experienced by these students is dissimilar to younger students approaching examinations that might be considered to be associated with lower academic stakes [4]. More research using longitudinal designs and carefully timed assessment of distress in examination and non-examination periods across grade levels is needed.

Given consistent reports that many students reported very high levels of distress, the question of whether distress experienced by students in their final years is too much is a topical one. This question is difficult to answer given the differences in measurement tools used and use of age appropriate normative cut-offs were generally absent. Examining the data from the two countries with the most research, using the TAI in the UK an average of 16% of students might be considered to have distress that was excessive, and using the DASS in the Australian data an average of 19% might be considered to have excessive distress. This equates to approximately one in six students. This rate of distress is very similar to the findings from two large Australian national surveys. In the Youth Mental Health Report [2] 21.2% of adolescents aged 15–19 years reported high levels of distress, and in the Australian National Survey of the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents [68] 19% of adolescents reported very high or high levels of distress. It is not clear if the distress captures in these national surveys predominately captures school based stress, or if the distress captured in the studies in this review capture distress that is different from normal. It is unclear what proportion of the one in six students with high levels of distress identified in this review had distress that was in the clinical range, and whether that was higher than expected. The recent Australian National Survey of the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents [68] found that 14.4% of 12–17 year olds met criteria for a mental disorder in the previous 12 months, and 7% met criteria for an anxiety disorder. Therefore it is likely that at least this proportion of students in the final years of school are likely to be clinically distressed. Although this distress might be transient, it is clear that some students are very distressed and would benefit from additional assistance to manage their distress. Establishing methods to identifying these students as soon as possible is an important direction for the future.

In addition, to the proximity of examinations, a number of other factors were found to be associated with increased distress in high school students in the final years. The most consistent effects related to individual differences such as female gender, anxiety proneness and freedom from negative cognitions. The higher prevalence of distress in females fits with gender based differences in emotionality and incidence rates of internalising mental disorders [67, 68]. Findings that greater anxiety proneness was associated with increased distress fits with longitudinal research that shows early child anxiety predicts later adolescent anxiety [106, 107]. It also fits theoretically with the Diathesis-Stress models [108] that assert that the combination of a diathesis or predispositional vulnerability coupled with a sufficient stressor results in psychological disorder or other poor psychological outcomes. As such the heightened stress associated with major exams or increased academic demands when coupled with a predisposing vulnerability towards distress, results in heightened distress that may be of clinical severity. Therefore, anxiety proneness is likely to be a significant predictor of senior school distress, and early identification of anxiety proneness in early school years could be used to predict students likely to experience excessive distress prior to the start of the senior years and thus be targeted for interventions prior to the senior school years.

The finding that freedom from negative thinking was a significant protective factor aligns with the findings that the cognitive elements of test anxiety and worry were the strongest predictors of student distress. The presence of negative cognitions are theorised to play a prominent role in the development and maintenance of child and adolescent anxiety disorders [16, 17]. For example, anxious students are likely to have the tendency to misinterpret ambiguous information (e.g. average marks), overinflate the likelihood and consequences of perceived negative events (e.g. “I will fail”, and “It will be a disaster if I fail”), and have poorer coping strategies for dealing with this heightened distress (e.g. avoidance, procrastination), exacerbating and maintaining distress. Furthermore, a number of studies demonstrated that students with greater worry about tests actually had poorer examination performance. This highlights the need to intervene with students who show high distress or report high levels of worry about tests early so that they are not disadvantaged educationally. Given the important role of negative cognitions in test anxiety, distress and subsequent examination performance, more attention needs to be paid to interventions that target negative cognitions particularly in the lead up to high stakes tests. There is some evidence that cognitive behavioural interventions are effective in reducing distress in senior years when delivered as prevention programs [109] or as targeted programs for those experiencing acute academic distress when delivered in school settings [110, 111], and perhaps even in single session universal interventions [112]. These cognitive behavioural interventions focus on teaching students how to manage negative cognitions, feelings of stress, and how to reduce avoidant behaviours, which are the key factors identified in this review as predictors of distress.

Given evidence for the impact of peer, family and school connectedness on student distress, future interventions might include strategies to bolster peer, school and family relationships. There was also emerging evidence for other significant predictors of distress including maladaptive perfectionism, poor sleep and excessive time spent on homework, with academic self-efficacy, academic buoyancy and resilience being protective factors. Although more research is needed to understand the unique contribution of these additional predictors over and above gender, anxiety proneness and freedom from negative cognitions, and how these factors interact with each other.

Finally, there was also emerging evidence for the role of perceived pressure from parents and teachers (through fear appeals) on student distress, although fear appeals were associated with increased distress and poorer examination performance only in some students. It is likely that anxious prone students are likely to interpret fear appeals or pressure from parents and teachers to perform as threatening and subsequently experience greater distress, although more research is needed to examine this relationship. Further research might also look at the underlying factors associated with the use of fear appeals by teachers and parents. It is likely that teacher/parental concerns related to suboptimal student performance drives this effect. As academic performance metrics are being used more frequently in the United Kingdom, Australia and elsewhere in accountability practices to judge school and teacher effectiveness [113], there is also emerging evidence for increasingly high levels of stress experienced by teachers who feel pressured to help their students get excellent results [114], this might result in teacher behaviours (such as the use of fear appeals that exacerbate student distress and reduce academic performance). Future research might track teacher stress and use of fear appeals and other teacher behaviours longitudinally to see how it relates to student’s distress in large studies. Strategies to reduce teacher distress might also prove a future target for interventions to relieve student distress.

Limitations of the study need to be considered. Firstly, the quality of the studies varied considerably with the majority being of lower quality. Secondly, studies varied in the measures used to measure distress as well as individual correlates of distress. Thirdly few studies had control or comparison groups and so it is difficult to determine the difference in distress and relationships with correlates as they compare to other age groups. Finally, the studies were generally cohort studies with only one measurement occasion such that most studies report on correlates of distress (and often grouping multiple factors together), such that individual contributions of factors or predictors of distress cannot be conclusively determined.

Summary

This systematic review examined the nature of and factors associated with student distress in the final two years of secondary school. The findings indicated academic stress during this period is a clear concern across a large number of countries with a significant number of students experiencing very high levels of distress. Research indicated distress was associated with individual differences in anxiety proneness, gender and freedom from negative cognitions, as well as connectedness to family, peer and school. Other factors also appear to be associated with increased distress, although more research is needed to understand their unique contributions. More methodologically rigorous research tracking distress over time is needed to better understand chronicity and severity of distress and moderating and mediating factors. Such information will assist endeavours to apply interventions preventatively or in a targeted fashion for at-risk students.

References

Huan VS, See YL, Ang RP, Har CW (2008) The impact of adolescent concerns on their academic stress. Educ Rev 60(2):169–178

Ivancic L, Perrens B, Fildes J, Perry Y, Christensen H (2014) Youth mental health report. Mission Australia and Black Dog Institute, AU

McGraw K, Moore S, Fuller A, Bates G (2008) Family, peer and school connectedness in final year secondary school students. Aust Psychol 43(1):27–37

Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bogels SM (2014) Adolescents' sleep in low-stress and high-stress (exam) times: a prospective quasi-experiment. Behav Sleep Med 12(6):493–506

Putwain D, Daly A (2014) Test anxiety prevalence and gender differences in a sample of English secondary school students. Educ Stud 40(5):554–570

Leonard NR, Gwadz MV, Ritchie A, Linick JL, Cleland CM, Elliott L, Grethel M (2015) A multi-method exploratory study of stress, coping, and substance use among high school youth in private schools. Front Psychol 6:1028–1044

Chamberlain S, Daly AL, Spalding V (2011) The fear factor: students’ experiences of test anxiety when taking A-level examinations. Pastor Care Educ 29(3):193–205

Putwain D (2009) Assessment and examination stress in Key Stage 4. Br Educ Res J 35(3):391–411

Robinson JA, Alexander DJ, Gradisar MS (2009) Preparing for Year 12 examinations: predictors of psychological distress and sleep. Aust J Psychol 61(2):59–68

Putwain D, Daly A, Chamberlain S, Sadreddini S (2015) Academically buoyant students are less anxious about and perform better in high-stakes examinations. Brit J Educ Stud 85(3):247–263

Spielberger CD (1980) Preliminary professional manual for the Test Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

King NJ, Ollendick TH, Prins PJ (2000) Test-anxious children and adolescents: psychopathology, cognition, and psychophysiological reactivity. Behav Chang 17(3):134–142

Putwain D (2008) Deconstructing test anxiety. Emot Behav Difficult 13(2):141–155

Gross C, Hen R (2004) The developmental origins of anxiety. Nat Rev Neurosci 5(7):545–552

Weems CF (2008) Developmental trajectories of childhood anxiety: Identifying continuity and change in anxious emotion. Dev Rev 28(4):488–502

Rapee RM (2001) The development of generalized anxiety. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR (eds) The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Oxford University Press, New York

Spence SH, Rapee RM (2016) The etiology of social anxiety disorder: an evidence-based model. Behav Res Ther 86:50–67

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

Critical Skills Appraisal Programme (2018) CASP Cohort Study Checklist [online]: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Critical Skills Appraisal Programme (2018) Qualitative Study Checklist [online]: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Hodge GM, McCormick J, Elliott R (1997) Examination-induced distress in a public examination at the completion of secondary schooling. Brit J Educ Psychol 67(2):185–197

Smith L, Sinclair KE (2000) Transforming the HSC: affective implications. Change 3(2):67–79

Akca F (2011) The relationship between test anxiety and learned helplessness. Soc Behav Pers 39(1):101–111

Guner-Kucukkaya P, Isik I (2010) Predictors of psychiatric symptom scores in a sample of Turkish high school students. Nurse Health Sci 12(4):429–436

Moulds JD (2003) Stress manifestation in high school students: an Australian sample. Psychol Schools 40(4):391–402

Wilkinson-Lee AM, Zhang Q, Nuno VL, Wilhelm MS (2011) Adolescent emotional distress: the role of family obligations and school connectedness. J Youth Adolesc 40(2):221–230

Cunha M, Paiva MJ (2012) Text anxiety in adolescents: the role of self-criticism and acceptance and mindfulness skills. Span J Psychol 15(2):533–543

Locker J, Cropley M (2004) Anxiety, depression and self-esteem in secondary school children. Sch Psychol Int 25(3):333–345

Einstein DA, Lovibond PF, Gaston JE (2000) Relationship between perfectionism and emotional symptoms in an adolescent sample. Aust J Psychol 52(2):89–93

Lay CH, Edwards JM, Parker JD, Endler NS (1989) An assessment of appraisal, anxiety, coping, and procrastination during an examination period. Eur J Person 3(3):195–208

Peluso MA, Savalli C, Curi M, Gorenstein C, Andrade LH (2010) Mood changes in the course of preparation for the Brazilian university admission exam—a longitudinal study. Rev Bras Psiquitr 32(1):30–36

Smith L, Sinclair KE, Chapman ES (2002) Students' goals, self-efficacy, self-handicapping, and negative affective responses: an Australian senior school student study. Contemp Educ Psychol 27(3):471–485

Yeni Palabiyik P (2014) A study of Turkish high school students' burnout and proficiency levels in relation to their sex. Novitas-ROYAL 8(2):169–177

Lovibond S, Lovibond P (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia, Sydney

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54(6):1063–1070

Kovacs M (1985) The children's depression inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacol Bull 21:995–998

Reynolds CR, Richmond BO (1978) What I think and feel: a revised measure of children's manifest anxiety. J Abnorm Child Psychol 6(2):271–280

Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Szafranski DD, Barrera TL, Norton PJ (2012) Test anxiety inventory: 30 years later. Anxiety Stress Coping 25(6):667–677

Szabó M (2010) The short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): factor structure in a young adolescent sample. J Adolesc 33(1):1–8

Willemsen J, Markey S, Declercq F, Vanhuele S (2011) Negative emotionality in a large community sample of adolescents: the factor structure and measurement invariance of the short version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21). Stress Health 27(3):120–128

Patrick J, Dyck M, Bramston P (2010) Depression Anxiety Stress Scale: is it valid for children and adolescents? J Clin Psychol 66(9):996–1007

Lin HJ, Yusoff MS (2013) Psychological distress, sources of stress and coping strategy in high school students. Int Med J 20(6):672–676

Goldberg DP (1972) The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. London University Press, London

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Group P (1999) Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. J Am Med Assoc 282(18):1737–1744

Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G (1979) Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford, New York

Yildirim I, Ergene T, Munir K (2007) High rates of depressive symptoms among senior high school students preparing for National University Entrance Examination in Turkey. IJSD 4(2):35–44

Lee M, Larson R (2000) The Korean "Examination Hell": long hours of studying, distress, and depression. J Youth Adolesc 29(2):249–271

Putwain D (2008) Do examinations stakes moderate the test anxiety–examination performance relationship? Educ Psychol 28(2):109–118

Putwain D (2008) Test anxiety and GCSE performance: the effect of gender and socio-economic background. EPIP 24(4):319–334

von der Embse NP, Witmer SE (2014) High-stakes accountability: student anxiety and large-scale testing. J Appl Sch Psychol 30(2):132–156

Putwain D (2007) Test anxiety in UK schoolchildren: prevalence and demographic patterns. Brit J Educ Psychol 77:579–593

Byrne B (2000) Relationships between anxiety, fear, self-esteem, and coping strategies in adolescence. J Adolesc 35(137):201–215

Chukwuorji JC, Nwonyi SK (2015) Test anxiety: contributions of gender, age, parent's occupation and self-esteem among secondary school students in Nigeria. J Psychol Afr 25(1):60–64

Ünal-Karagüven MH (2015) Demographic factors and communal mastery as predictors of academic motivation and test anxiety. J Educ Train Stud 3(3):1–12

Erzen E, Odacı H (2016) The effect of the attachment styles and self-efficacy of adolescents preparing for university entrance tests in Turkey on predicting test anxiety. Educ Psychol 36(10):1728–1741

Karatas H, Alci B, Aydin H (2013) Correlation among high school senior students' test anxiety, academic performance and points of University Entrance Exam. Educ Res Rev 8(13):919–926

Liu YY (2012) Students' perceptions of school climate and trait test anxiety. Psychol Rep 111(3):761–764

Lushington K, Wilson A, Biggs S, Dollman J, Martin J, Kennedy D (2015) Culture, extracurricular activity, sleep habits, and mental health: a comparison of senior high school Asian-Australian and Caucasian-Australian adolescents. Int J Ment Health 44(1–2):139–157

Rahafar A, Maghsudloo M, Farhangnia S, Vollmer C, Randler C (2016) The role of chronotype, gender, test anxiety, and conscientiousness in academic achievement of high school students. Chronobiol Int 33(1):1–9

Ringeisen T, Buchwald P (2010) Test anxiety and positive and negative emotional states during an examination. Special Issue Test Anxiety 14(4):431–447

Sari SA, Bilek G, Celik E (2018) Test anxiety and self-esteem in senior high school students: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry 72(2):84–88

Yildirim I, Ergene T, Munir K (2007) Academic achievement, perfectionism and social support as predictors of test anxiety. Hacet U J Educ 34:287–296

Manley MJ, Rosemier RA (1972) Developmental trends in general and test anxiety among junior and senior high school students. J Genet Psychol 120(2):219–226

Christensen H (1979) Test anxiety and academic achievement in high school students. Percept Mot Ski 49(2):648

Aysan F, Thompson D, Hamarat E (2001) Test anxiety, coping strategies, and perceived health in a group of high school students: a Turkish sample. J Genet Psychol 162(4):402–411

Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L et al (2010) Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(10):980–989

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven de Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J et al (2015) The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Australian Government Department of Health, Canberra

Chin E, Williams MW, Taylor JE, Harvey ST (2017) The influence of negative affect on test anxiety and academic performance: an examination of the tripartite model of emotions. Learn Individ Differ 54:1–8

Segool NK, von der Embse NP, Mata AD, Gallant J (2014) Cognitive behavioral model of test anxiety in a high-stakes context: an exploratory study. School Ment Health 6(1):50–61

Sarason IG (1963) Test anxiety and intellectual performance. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 66(1):73–75

McCann SJ, Meen KS (1984) Anxiety, ability, and academic achievement. J Soc Psychol 124(2):257–258

Çırak Y (2016) University entrance exams from the perspective of senior high school students. J Educ Train Stud 4(9):177–185

Kouzma NM, Kennedy GA (2004) Self-reported sources of stress in senior high school students. Psychol Rep 94(1):314–316

Putwain D (2011) How is examination stress experienced by secondary students preparing for their General Certificate of Secondary Education examinations and how can it be explained? Int J Qual Stud Educ 24(6):717–731

Schmidt S, Tinti C, Levine LJ, Testa S (2010) Appraisals, emotions and emotion regulation: an integrative approach. Motiv Emot 34(1):63–72

Smyth E, Banks J (2012) High stakes testing and student perspectives on teaching and learning in the Republic of Ireland. Educ Assess Eval Acc 24(4):283–306

Liebert RM, Morris LW (1967) Cognitive and emotional components of test anxiety: a distinction and some initial data. Psychol Rep 20(3):975–978

Putwain D, Connors L, Symes W (2010) Do cognitive distortions mediate the test anxiety–examination performance relationship? Educ Psychol 30(1):11–26

Sud A, Sujata (2006) Academic performance in relation to self-handicapping, test anxiety and study habits of high school children. Psychol Stud 51(4):304–309

Putwain D, Daly A, Chamberlain S, Sadreddini S (2016) ‘Sink or swim’: buoyancy and coping in the cognitive test anxiety—academic performance relationship. Educ Psychol 36(10):1807–1825

Putwain D, Aveyard B (2018) Is perceived control a critical factor in understanding the negative relationship between cognitive test anxiety and examination performance? Sch Psychol Q 33(1):65–74

Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R (1990) The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn Ther Res 14(5):449–468

Hewitt PL, Flett GL (1991) Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Pers Soc Psychol 60(3):456–470

Flett GL, Panico T, Hewitt PL (2011) Perfectionism, type A behavior, and self-efficacy in depression and health symptoms among adolescents. Curr Psychol 30(2):105–116

Eum K, Rice KG (2011) Test anxiety, perfectionism, goal orientation, and academic performance. Anxiety Stress Coping 24(2):167–178

Putwain D, Connors L, Symes W, Douglas-Osborn E (2012) Is academic buoyancy anything more than adaptive coping? Anxiety Stress Coping 25(3):349–358

Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP et al (2017) Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull 143(9):939–991

Putwain D, Symes W (2011) Perceived fear appeals and examination performance: facilitating or debilitating outcomes? Learn Individ Differ 21(2):227–232

Martin A, Marsh H (2009) Academic resilience and academic buoyancy: Multidimensional and hierarchical conceptual framing of causes, correlates and cognate constructs. Oxf Rev Educ 35(3):353–370

Martin A, Marsh H (2006) Academic resilience and its psychological and educational correlates: a construct validity approach. Psychol Schools 43(3):267–281

Putwain D, Daly A (2013) Do clusters of test anxiety and academic buoyancy differentially predict academic performance? Learn Individ Differ 27:157–162

Martin A, Colmar S, Davey L, Marsh H (2010) Longitudinal modelling of academic buoyancy and motivation: do the '5Cs' hold up over time? Br J Educ Psychol 80:473–496

Kouzma NM, Kennedy GA (2002) Homework, stress and mood disturbance in senior high school students. Psychol Rep 91(1):193–198

Akcoltekin A (2015) High school students’ time management skills in relation to research anxiety. Educ Res Rev 10(16):2241–2249

Astill RG, Verhoeven D, Vijzelaar RL, Van Someren EJ (2013) Chronic stress undermines the compensatory sleep efficiency increase in response to sleep restriction in adolescents. J Sleep Res 22(4):373–379

Baum KT, Desai A, Field J, Miller LE, Rausch J, Beebe DW (2014) Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55(2):180–190

Sarchiapone M, Mandelli L, Carli V, Losue M, Wasserman C, Hadlaczky G et al (2014) Hours of sleep in adolescents and its association with anxiety, emotional concerns, and suicidal ideation. Sleep Med 15(2):248–254

Short MA, Gradisar M, Lack LC, Wright HR, Dohnt H (2013) The sleep patterns and well-being of Australian adolescents. J Adolesc 36(1):103–110

Ramsawh HJ, Stein MB, Belik SL, Jacobi F, Sareen J (2009) Relationship of anxiety disorders, sleep quality, and functional impairment in a community sample. J Psychiatr Res 43(10):926–933

Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K (2005) Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry 66(10):1254–1269

Riekie H, Aldridge JM, Afari E (2017) The role of the school climate in high school students’ mental health and identity formation: a South Australian study. Br Educ Res J 43(1):95–123

Putwain D, Symes W (2011) Teachers' use of fear appeals in the mathematics classroom: worrying or motivating students? Br J Educ Psychol 81(3):456–474

Symes W, Putwain D, Remedios R (2015) The enabling and protective role of academic buoyancy in the appraisal of fear appeals used prior to high stakes examinations. Sch Psychol Int 36(6):605–619

von der Embse NP, Schultz BK, Draughn JD (2015) Readying students to test: the influence of fear and efficacy appeals on anxiety and test performance. Sch Psychol Int 36(6):620–637

Ollendick TH, King NJ (1994) Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of internalizing problems in children: the role of longitudinal data. J Consult Clin Psychol 62(5):918–927

Rapee RM (2014) Preschool environment and temperament as predictors of social and nonsocial anxiety disorders in middle adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53(3):320–328

Zuckerman M (1999) Diathesis-stress models. In: Zuckerman M (ed) Vulnerability to psychopathology: a biosocial model. American Psychological Association, Washington, US

Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H (2017) School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 51:30–47

Lowe C, Wuthrich VM, Hudson JL (2020) Randomised controlled trial of Study Without Stress: a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy group program to reduce academic stress in students in the final year of high school. In preparation

Wuthrich VM, Lowe C (2015) Study without stress program. Department of Psychology, Macquarie University, Sydney, AU, Centre for Emotional Health

Varlow M, Wuthrich V, Murrihy R, Remond L, Tuquiri R, Van Kessel J et al (2009) Stress literacy in Australian adolescents. Youth Stud Aust 28(4):29–34

Saeki E, Pendergast L, Segool NK, von der Embse NP (2015) Potential psychosocial and instructional consequences of the common core state standards: implications for research and practice. Contemp Sch Psychol 19(2):89–97

von der Embse NP, Pendergast LL, Segool N, Saeki E, Ryan S (2016) The influence of test-based accountability policies on school climate and teacher stress across four states. Teach Teach Educ 59:492–502

Daly AL, Chamberlain S, Spalding V (2011) Test anxiety, heart rate and performance in A-level French speaking mock exams: an exploratory study. Educ Res 53(3):321–330

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wuthrich, V.M., Jagiello, T. & Azzi, V. Academic Stress in the Final Years of School: A Systematic Literature Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 51, 986–1015 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00981-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00981-y