Abstract

This study investigated how supportive relationships with peers and parents protect children against ongoing victimization, internalizing problems and depression. The longitudinal data set tracked progress of 111 children recruited for the trial of Resilience Triple P, and previously bullied by peers. Informants included children, parents and teachers. Higher levels of facilitative parenting (warm parenting that supports peer relationships) and peer acceptance predicted lower later levels of both depression and victimization over time. Higher levels of child friendedness predicted lower levels of child reports of internalizing problems. Children’s friendships, acceptance by same sex peers and facilitative parenting all played moderating roles in protecting against ongoing victimization and internalizing problems. Peer acceptance mediated the relationships between facilitative parenting and victimization. Facilitative parenting mediated the relationship between peer acceptance and depression. It was concluded that supportive relationships with parents and peers play important and complementary roles in protecting children against ongoing victimization and depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children who are victimized by peers are at heightened risk for a wide range of psychosocial problems, and especially for depression [1]. Being bullied at primary school increases risk of depression 2 years later [2], into adolescence, and decades later well into adulthood [3, 4]. Children who have been previously victimized are also at greater risk for ongoing victimization. For frequently bullied children, victimization is quite stable from year to year [5, 6], meaning the same children may suffer victimization over many years. Depression and other internalizing problems are not only consequences of being bullied; they are also risk factors for further victimization [7], resulting in both worsening victimization and depression over time. However, supportive relationships may protect children from this downward spiral. Previous research shows that positive relationships with peers and parents are associated with better outcomes for children bullied by peers [8, 9], but the specific mechanisms through which relationships protect children from victimization and internalizing problems over time are not clear. The current study investigates the role of supportive peer and parent relationships in mitigating later depression, internalizing problems and victimization in the sample of children who had been bullied by peers at school.

We will first examine how supportive relationships might influence later internalizing problems, and then turn to how they might affect risk of victimization. Figure 1 illustrates several mechanisms through which supportive relationships might protect children from internalizing problems following victimization, some of which have been explored by previous theory and research. Rutter [10, 11] theorized that positive relationships with family and peers could strengthen resilience, and protect children against the negative impacts of adversity. Victimization by peers at school is a salient form of adversity in the developmental period [12]. Cohen and Wills [13] hypothesized two possible mechanisms through which social support could reduce stress and promote wellbeing following adversity. The direct effects model states that positive relationships directly reduce future stress, thus compensating for the impact on adversity, as depicted by Mechanism 1 (M1) in Fig. 1. Alternatively, the stress buffering model states that positive relationships interact with the stressor to moderate the detrimental impact of the stressor on future stress (M2). A third possibility, the mediational model (M3), is that positive relationships mediate the impact of adversity on future stress; so, in the case of school bullying, victimization may erode children’s friendships which in turn affects future depression and internalizing problems (M3). Given that depression is quite stable over time for children and early adolescents [14, 15], supportive relationships may also influence the ongoing trajectory of depression in these same three ways; they could impact future internalizing directly (M1), moderate impact of past on future stress (M4), or mediate between past and future stress (M5).

There are very few studies investigating how supportive peer relationships protect children against internalizing problems. A study with 7–9-year-old children [16] found that children’s friendships moderated the impact of social isolation on risk of later internalizing problems, consistent with M2. A study of children aged 9–12 years [17] found that self-reported loneliness mediated subsequent depressed mood associated with negative peer experiences, consistent with M3. Similarly, little is known about the mechanisms through which parenting protects children against internalizing problems. A large scale longitudinal study [9] found that warm, responsive parenting buffers children from the internalizing consequences of victimization over time, consistent with the stress buffering hypothesis (M2). However, another large three-wave longitudinal study [18] specifically designed to test Cohen and Will’s [13] model, found that supportive parenting had a direct impact on depression over time (M1), but did not moderate the impact of victimization on depression (~ M2).

Turning to the impact on victimization, there are several ways in which supportive relationships may protect children from future victimization, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (M6–M10). Supportive relationships may have a direct effect on victimization (M6); for instance, children who bully may be less likely to target a child amongst friends. Alternatively, supportive relationships could buffer the impact of depression and internalizing problems to ongoing victimization; after Cohen and Wills, we call this the “victimization buffering hypothesis” (M7). Another option is that supportive relationships mediate between internalizing problems and victimization (M8). Given that past victimization tends to predict future victimization, all three of these mechanisms could also apply to the relationship between past and future victimization (M6, M9, M10).

Previous research suggests that friendships protect children against ongoing risk of victimization from their own social behavior [19, 20], consistent with M6. Two previous longitudinal studies have found that the number and peer status of friends protect children by buffering the impact of risk earlier personal and familial risk factors on victimization [19, 21]. One study [8] found that having a best friend marginally moderated the impact of internalizing on victimization, consistent with M7, and that having a “protective friendship” (i.e. someone who stood up for the child) mediated the impact of internalizing on victimization, consistent with M8. Another study [17] found that self-reported loneliness mediated subsequent depressed mood associated with negative peer experiences, also consistent with M8. Even less is known about how supportive parenting protects children against victimization.

A recent meta-analysis [22] confirmed that positive parenting behaviors (including high parental involvement and support, and warm and affectionate relationships) were associated with lower levels of victimization and were likely to protect against victimization. However, very little is known about how this occurs. Bowes et al. [23] found that warm parenting protects children against an ongoing trajectory of victimization in the transition from primary to secondary school, consistent with M9. To our knowledge there are no other directly relevant studies.

The current study investigates mechanisms through which supportive relationships with peers and parents affect the ongoing trajectory of victimization and depression in children bullied by peers. We utilized the longitudinal data set from the RCT of Resilience Triple P, which recruited children with a history of peer victimization [24]. Resilience Triple P is a targeted cognitive behavioral family intervention for children bullied by peers combining social and emotional skills training for children, with training of parents in a particular kind of supportive parent, called facilitative parenting. Facilitative parenting draws together parenting behaviors from all three paths found by McDowell and Parke [26] to predict positive peer skills and relationships over time: warm responsive parenting (e.g. warm relating), direct instruction (e.g. coaching children to manage peer problems), and provision of opportunities to develop peer relationships (e.g. supporting friendships through playdates). Previous cross-sectional studies showed that facilitative parenting differentiated children reported by teachers as victimized from those who were not [25], and was negatively associated with depression [27]. The RCT found that Resilience Triple P (involving facilitative parenting) lead to greater reductions in victimization and depressive symptom, and greater improvements in peer acceptance over 9 months than reported for control families [24]. However, no previous study has investigated the mechanisms through which facilitative parenting apparently influences victimization and depression.

This study investigates the mechanisms through which supportive peer and parent relationships affect victimization and depression in children over time. On the basis of previous research and theory, we hypothesized that supportive peer relationships would: (1) have a direct negative impact on victimization i.e. reduce victimization (M6); (2) moderate (reduce) the impact of victimization on later internalizing problems (M2); (3) mediate (negatively) between victimization and later internalizing problems (M3); (4) moderate (reduce) the impact of internalizing problems on later victimization (M7); and (5) mediate (negatively) the impact of internalizing problems on victimization (M8). Based on previous research on the role of warm, responsive parenting in protecting children against victimization and internalizing problems [18, 23], we hypothesized that facilitative parenting would (6) have a direct negative impact on children’s internalizing problems (M1) rather than moderate the impact of victimization on internalizing problems (~ M2); (7) moderate (negatively) the impact of victimization on future victimization (M9). Unlike peers, parents are usually not present when victimization occurs so may be less likely to influence victimization directly. Facilitative parenting includes direct coaching and instruction, and provision of opportunities to develop peer relationships, which have been shown to predict improved peer relationships and peer acceptance over time [26]. We therefore also hypothesize that (8) rather than influencing victimization directly, the effect of facilitative parenting on victimization will be mediated by supportive peer relationships.

Method

This study utilized the longitudinal data set generated by the RCT of Resilience Triple P [24]. Children involved had a history of being bullied at school by peers, according to their parents. They were tracked through three assessments over 9 months, involving children, parents and teachers as informants. Families were randomly allocated to intervention and control conditions. As the effectiveness of the intervention was not the focus of this study, we controlled for this in all analyses.

Participants

The participants included 111 children, their parents and teachers. To be eligible to participate, children needed to be (1) aged between 6 and 12 years, (2) living at home, (3) attending a regular elementary school, and (4) bullied at school according to the parent. Bullying was defined behaviorally as “hurtful behavior which was typically repeated, and could be physical or verbal or indirect social, and carried out in person or through technology”. The parent needed to verify that the child had experienced either (a) ongoing bullying for at least the past month and/or (b) a recurrent problem with being bullied over > 1 year. The sample consisted of 61% boys and 39% girls ranging from 6 to 12 years with a mean age of 8.72 years (SD = 1.68 years). Almost one quarter (24%) of children had a pre-existing diagnosis affecting learning or behavior, including 8% diagnosed with Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Most primary caregivers (95%) were mothers and consisted of 73% born in Australia. Just over half the primary caregivers (54%) had completed a university degree, 34% an adult certificate or diploma, and the remaining 12% Grade 10 or 12 of school.

Measures

Data were collected from parents, children and teachers through assessments at 0, 3 and 9 months from recruitment. Measures relevant to the current study are reported below.

Children’s Depression and Internalizing Measures

Child Depressive Symptoms

The Preschool Feelings Checklist [28] is a 16-item parent checklist of symptoms of depression. Parents answer “yes” or “no” for each question (e.g. “Frequently appears sad or says he/she feels sad”). This measure correlates well with established depression measures [29] and has discriminated primary school aged children (7–12 years) reported by teachers to be bullied from those who were not [25]. This measure demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in this sample (α = .73).

Child Internalizing Response to Peer Behavior

The Internalising Feelings scale from the Sensitivity to Peer Behaviour Interview (SPBI) [30] measures children’s reports of internalizing responses to six hypothetical scenarios of negative peer behavior (e.g., “A child calls you stupid”). After the child designs a character for him- or herself, a felt board and characters are used to demonstrate scenarios. Children report how upset they would feel in each situation from ‘not upset’, ‘a bit upset’, or ‘very upset’. This scale has previously discriminated bullied from non-bullied children [12] and had good internal consistency in this sample (α = .84).

Children’s Victimization by Peers

Overt and Relational Victimization

The Preschool Peer Victimization Measure (PPVM) is a brief nine-item teacher report of peer treatment of the child [31], previously shown to have reasonable test–retest reliability with children from 3 to 5 years (r = .37 to .76) [32]. All items are appropriate for 6- to 12-year-old children. Teachers rate items from 0 (never or almost never true) to 5 (always or almost always true). Subscales include overt victimization, comprising physical and verbal items (e.g., “This child is called a mean name”) and Relational Victimization (e.g., “This child gets ignored by playmates when they are mad at him/her”). Both subscales demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .77, α = .83) with this sample.

Child Report of Victimization

Things Kids Do (TKD) [33] asks children to rate the frequency of aversive peer behaviors in the last 4 or 5 school days on a 5-point scale from “not at all” to “heaps”. The TKD Bullying subscale includes 14 items about verbal, physical or relational behaviors (e.g. “Did other kids at school give you mean looks?”). It demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .91) in a general sample of children aged 5–12 years, and in this sample (α = .91).

Supportive Peer Relationships

Friendedness

The Loneliness Questionnaire [34] includes 24 statements on friendedness (e.g. “I can find a friend when I need one”), which children rate from 5 (always true) to 1 (not true at all). It has previously demonstrated very good internal consistency (α = .90) with children between Grade 3 and 6 of school [35], and was previously extended to children as young as 5 years, through use of concrete materials representing levels of agreement [25]. The same materials produced good internal consistency with this sample (α = .93).

Acceptance by Peers

We used two single item scales of children’s peer acceptance from The Preschool Social Behavior Scale—Teacher (PSBS-T) [32]. Teachers rated children from 1 (never or almost never true) to 5 (always or almost always true) on acceptance by peers of the same and opposite sex (e.g. “This child is well-liked by peers of the same sex”).

Facilitative Parenting

Facilitative Parenting Scale

The Facilitative Parenting Scale (FPS) [36] is a self-report measure of parenting which is supportive of children’s peer skills and relationships. Parent rate 58 statements from 1 (not true) to 5 (extremely true) over the last few weeks. There are items about warm relating (e.g. “My child and I enjoy time together”); parental coaching of social skills (e.g. “I help my child practise standing up for him/herself”); support of children’s friendships (e.g. “I arrange for my child to see friends out of school”); enabling appropriate child independence (e.g. “I tend to baby my child” [reverse scored]); and communication with the school (e.g. “I can calmly discuss any concerns that might arise with my child’s teacher”). This scale previously demonstrated good internal consistency and low scores have discriminated children rated by teachers as being bullied from children who are not bullied [25]. Internal consistency of the scale was good for this study (α = .88).

Procedure

Ethical clearance was obtained from university (UQ BSSERC Project No. 2010000536) and school authorities. Families visited a child and family clinic to complete assessments. Parents completed written questionnaires whilst research assistants interviewed their child. Families were randomly allocated to the intervention condition (Resilience Triple P) or control condition at the end of the initial assessment. Families were contacted for a second assessment at 3 months and a third assessment at 9 months after the initial assessment. Teachers completed questionnaires at the same three timepoints. Further details of the RCT are described elsewhere [24].

Statistical Analyses

We conducted basic data screening and missing data analysis. Before calculating scale scores, we imputed missing data points through Expectation Maximization, on each scale separately as recommended [37]. We then used hierarchical multiple regression (HMR) from the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) to test main effects and mediated effects of supportive relationship measures at 3 months (Time 2) on the outcome variables at 9 months (Time 3) after controlling for the corresponding outcome variables at 0 months (Time 1). In all regression analyses, we controlled for experimental condition by including it as a covariate at the first step.

Preliminary analyses revealed that several measures of children’s adjustment were non-normally distributed, which is common for psychological measures [38]. HMR assumes normality [39], so we replicated analyses using the bootstrapping through SPSS [40]. Bootstrapping involves repeated resampling from the data set to calculate a sampling distribution; it is recommended to reduce the impact of non-normality on reliability of regression models [41]. We checked whether the sample size was sufficient to detect effects using G-power [42]. Achieved power (.96) was sufficient to detect medium effect sizes (f2 = .15) but achieved power for small effect sizes was poor (.24).

We tested whether supportive relationships mediated between other variables when the necessary pre-conditions were met. Baron and Kenny [43] defined the following pre-conditions for mediation: the IV significantly predicts the DV; the IV significantly predicts the proposed mediator; the proposed mediator significantly predicts the DV. If all these conditions are met and the effect of the IV on the DV is no longer significant after controlling for the mediator, we can conclude that the mediating variable completely mediates the relationship between IV and DV [44]. We tested the significance of the indirect affect through a bootstrap estimation approach with 5000 samples using the PROCESS macro [45, 46] (Model 4), currently recommended as the most accurate method for testing indirect effects [47]. We also utilized PROCESS (Model 1) to test significance of supportive relationship variables as moderators. PROCESS centres all variables before calculating product terms so avoids problems of multicollinearity.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

A missing data analysis (including that due to attrition) revealed 10.59% of total values were missing. Little’s test indicated that data points were missing completely at random, χ2 (4642) = 3342.93, p > .999, confirming that data imputation through Expectation Maximization was appropriate [37]. Re-analyses using bootstrapping did not change any patterns of significance; the regression coefficients and confidence intervals reported have been adjusted by bookstrapping. Levels of tolerance for all predictors were within acceptable limits; however, the correlation between the two peer acceptance variables was high (r = .77), which affected performance when the two scales were included in the same analysis. We therefore used separate regressions for the two peer acceptance measures, but, to prevent type 1 errors due to replication of a similar analysis, we adjusted alpha levels to p < .025 consistent with conservative Bonferroni corrections.

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations and correlations between outcome and predictor variables. All outcome measures at Time 3 (9 months) had significant positive correlations with the corresponding measure at Time 1 (0 months). There were mixed results for associations between victimization measures at Time 1 and internalizing measures at Time 3. Child internalizing feelings at Time 3 had a significant positive association with child reports of victimization at Time 1. However, child depression at Time 3 was not significantly associated with any Time 1 victimization measures. Most associations between child internalizing measures at Time 1 and victimization measures at Time 3 were not significant. Teachers’ reports of victimization at Time 3 were not significantly associated with either the child depression or child internalizing measure at Time 1. The child report of victimization at Time 3 was significantly positively associated with internalizing feelings at Time 1.

As shown in Table 1, outcome measures of children’s depression and internalizing problems at Time 3 had significant positive correlations with supportive relationship measures at Time 2. Child depression at Time 3 had a significant negative association with facilitative parenting, and with child acceptance by same and opposite sex peers. Child internalizing feelings at Time 3 had a significant negative association with child friendedness. All measures of victimization at Time 3 had significant negative associations with friendedness and acceptance by same and opposite sex peers. Overt victimization at Time 3 also had a significant negative association with facilitative parenting.

Main Effects of Supportive Relationships on Depression and Internalizing Responses

Table 2 displays HMRs testing whether supportive relationships at Time 2 predicted depression and internalizing problems at Time 3. After controlling for experimental condition and Time 1 depression, higher levels of facilitative parenting predicted lower levels of Time 3 depression (p < .001). Acceptance by same and opposite sex peers (p = .021; p = .023) also predicted lower depression, meeting the Bonferroni adjusted alpha of p < .025. After controlling for experimental condition and Time 1 internalizing responses, friendedness predicted lower levels of Time 3 internalizing responses (p = .003).

Table 3 displays HMRs testing whether Time 2 supportive relationships predicted Time 3 victimization. After controlling for experimental condition and overt victimization at Time 1, all four supportive relationships variables predicted lower levels of overt victimization at Time 3. For the corresponding regression on relational victimization, high levels of peer acceptance and facilitative parenting predicted lower Time 3 victimization. For the child report of victimization, higher levels of friendedness and peer acceptance at Time 2 predicted lower Time 3 victimization.

Supportive Relationships as Moderators of Relationship Between Victimization and Internalizing

We tested for the recursive relationship between victimization and internalizing problems reported in previous research [7] and whether supportive relationships moderated this relationship. We first tested whether Time 1 victimization predicted Time 3 internalizing measures. After controlling for experimental condition and depression at Time 1, overt victimization at Time 1 did not predict depression at Time 3 (F [2, 105] = 0.16, p = .853); neither overt (β = − .02, p = .858) nor relational victimization (β = .06, p = .583) accounted for significant variance. Facilitative parenting did not moderate this relationship (p = .987); nor did acceptance by same sex (p = .223) or opposite sex peers (p = .234) or friendedness (p = .933). Similarly, the relationship between relational victimization and later depression was not moderated by facilitative parenting (p = .107), nor acceptance by same sex or opposite sex peers (p = .719; p = .733), nor friendedness (p = .533). Child reports of victimization at Time 1 did not predict child internalizing responses at Time 3 (F [1, 106] = 2.28, p = .134, β = .15) after controlling for experimental condition and Time 1 internalizing responses. Facilitative parenting did not moderate the relationship (p = .311); nor did acceptance by same or opposite sex peers (p = .859; p = .637). However, friendedness moderated this relationship (p = .035); conditional effects modelling showed that victimization predicted later internalizing responses for lower levels of friendedness (p = .003) but not for medium (p = .089) or high levels of friendedness (p = .954).

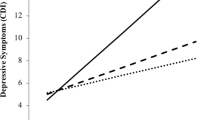

We tested if measures of Time 1 internalizing problems predicted Time 3 victimization and whether Time 2 supportive relationships moderated this relationship. After controlling for experimental condition and overt victimization at Time 1, child depression at Time 1 did not predict overt victimization (F [1, 106] = 1.54, p = .218, β = .11) or relational victimization (F [1, 106] = 0.42, p = .519, β = .06) at Time 3. Tests of moderational effects indicated that acceptance by same sex peers moderated the relationship between depression and later overt victimization (p = .021); depression predicted overt victimization for low levels of peer acceptance (p = .023) but not for medium (p = .133) or high levels of peer acceptance (p = .130). Neither acceptance by opposite sex peers (p = .294), facilitative parenting (p = .623), nor friendedness (p = .759) were significant moderators. None of the supportive relationship measures moderated the relationship between depression and relational victimization. Child reports of internalizing responses at Time 1 did not predict child reports of victimization at Time 3 (F [1, 106] = 2.72, p = .102, β = .16). However, friendedness moderated the relationship (p = .021); victimization predicted internalizing responses for lower levels (p = .024) but not for medium (p = .182) or high levels of friendedness (p = .482). Facilitative parenting also marginally moderated the relationship (p = .055); victimization predicted internalizing responses for low (p = .001) and medium (p = .001), but not for high levels of facilitative parenting (p = .466). Acceptance by same sex peers also marginally moderated the relationship (p = .026); victimization predicted internalizing responses for lower (p = .010) but not medium (p = .068) or high levels of peer acceptance (p = .766). Acceptance by opposite sex peers was not a significant moderator (p = .112).

Supportive Relationships as Moderators of Ongoing Victimization

After controlling for experimental condition, overt victimization at Time 1 predicted overt victimization at Time 3 (F [1, 107] = 13.01, p < .001, β = .33). Neither facilitative parenting (p = .261), nor acceptance by same sex or opposite sex peers (p = .538; p = .735) moderated this relationship. Child friendedness did marginally moderate the relationship (p = .078); Time 1 overt victimization significantly predicted Time 3 overt victimization at low (p = .001) and medium levels (p < .001), but not at high levels of friendedness (p = .236). After controlling for experimental condition, relational victimization at Time 1 predicted relational victimization at Time 3 (F [1, 107] = 8.81, p = .004, β = .28). Neither facilitative parenting (p = .330), nor acceptance by same sex (p = .085), acceptance by opposite sex peers (p = .574) or friendedness (p = .647) moderated the relationship. After controlling for experimental condition, children’s reports of victimization at Time 1 predicted their Time 3 reports (F [1, 107] = 20.22, p < .001, β = .40). Facilitative parenting moderated the relationship between Time 1 and Time 3 child reports of victimization (p < .001); Time 1 victimization predicted Time 3 victimization for low (p < .001) and medium levels (p < .001) but not at high levels of facilitative parenting (p = .599). Peer acceptance by same sex peers also moderated the relationship (p = .003); Time 1 victimization predicted Time 3 victimization at low (p < .001) and medium levels (p < .001) but not at high levels of acceptance by same sex peers (p = .467). Peer acceptance by opposite sex peers was not a significant moderator (p = .134).

Supportive Relationships as Moderators of Ongoing Internalizing Problems

After controlling for experimental condition, Time 1 depression predicted Time 3 depression (F [1, 107] = 23.48, p < .001, β = .41). Facilitative parenting did not moderate this relationship (p = .168); nor did acceptance by same or opposite sex peers (p = .873; p = .748). After controlling for experimental condition, internalizing responses at Time 1 predicted internalizing responses at Time 3 (F [1, 107] = 20.54, p < .001, β = .40). Child friendedness moderated the relationship between Time 1 and Time 3 internalizing responses (p = .013); Time 1 internalizing predicted Time 3 internalizing at low (p < .001) and medium (p = .002) but not at high levels of friendedness (p = .467).

The Mediating Role of Supportive Relationships for Depression and Victimization

Pre-conditions were met for examining whether facilitative parenting mediated the relationship between acceptance by peers and depression. Table 4 displays regressions predicting child depression at Time 3 by acceptance of same sex peers, with and without facilitative parenting as a mediator. When facilitative parenting was included at Step 2, acceptance by same sex peers no longer significantly predicted child depression. This suggests that facilitative parenting mediated the impact of acceptance by same sex peers on later depression. The indirect regression coefficient was significant, B = − .24, SE = .10, 95% CI = − .49, − .09. The mediation model is illustrated in Fig. 1. When the above analyses were replicated using acceptance by opposite sex peers, the pattern of results was identical. When facilitative parenting was included at Step 2, acceptance by opposite sex peers no longer significantly predicted child depression at Time 3 (F [1, 105] = 2.24, β = − .12, p = .138). The indirect coefficient was significant, B = − .19, SE = .07, 95% CI = − .38, − .07.

We tested the other logical possibility: that peer acceptance mediates the effect of facilitative parenting on child depression. Facilitative parenting still predicted depression at 9 months after accounting for same sex peer acceptance (F [1, 105] = 10.27, β = − .28, p = .002), and after accounting for opposite sex peer acceptance (F [1, 105] = 11.13, β = − .28, p = .001). This suggests the impact of facilitative parenting on depression is not mediated by peer acceptance; rather facilitative parenting impacts depression directly.

Pre-conditions were met for testing whether peer acceptance mediated the relationship between Time 2 facilitative parenting and Time 3 overt victimization. Table 4 shows that after controlling for experimental condition and overt victimization at Time 1, facilitative parenting predicted overt victimization. However, after controlling for acceptance by same sex peers, facilitative parenting no longer significantly predicted victimization (F [1, 105] = 2.84, β = − .15, p = .095). When opposite sex peer acceptance was substituted, facilitative parenting still marginally predicted victimization (F [1, 105] = 5.09, β = − .20, p = .026). This suggests that acceptance by same sex peers mediated the relationship between facilitative parenting and later overt victimization. The indirect effect was significant for acceptance by same sex peers, B = − .21, SE = .10, 95% CI = − .46, − .06, and marginal for acceptance by opposite sex peers B = − .10, SE = .08, 95% CI = − .29, − .01. Figure 2 shows the mediation model for same sex peers. We tested the other logical (although theoretically implausible) possibility: that facilitative parenting mediated the impact of peer acceptance on overt victimization. Acceptance by same sex peers still significantly predicted overt victimization at Time 3 after controlling for facilitative parenting (F [1, 105] = 11.69, p = .001, β = − .31); the same was true for acceptance by opposite sex peers (F [1, 105] = 4.80, p = .031, β = − .20). This suggests that peer acceptance impacted overt victimization directly rather than being mediated by facilitative parenting (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study investigated how supportive relationships influence ongoing victimization, depression and internalizing problems in children bullied by peers. Consistent with hypotheses, both facilitative parenting and supportive peer relationships predicted ongoing victimization and internalizing problems through multiple mechanisms. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, supportive peer relationships in the form of peer acceptance directly predicted victimization, and also had a significant indirect effect on depression through facilitative parenting. Consistent with Hypotheses 6 and 9, facilitating parenting directly impacted depression, and had a significant indirect effect on victimization through peer acceptance. Consistent with Hypotheses 2 and 4 and previous research [16, 19, 21], friendships moderated the impact of victimization on internalizing problems on each other over time; additional to hypotheses, peer acceptance moderated the course of internalizing problems (M5), and the course of victimization (M9) over time. Consistent with Hypothesis 7 and previous research about warm parenting [18], facilitative parented moderated change in victimization over time. Contrary to Hypotheses 3 and 8 and previous research [10, 17], supportive peer relationships did not mediate the relationship between victimization and internalizing over time, due to the non-significant associations between victimization and internalizing. Overall, these results confirm that support from parents and peers protect children from ongoing victimization and internalizing problems. We will discuss consistencies and inconsistencies to hypotheses, starting with how supportive relationships impact depression and internalizing problems, and then victimization.

Children who are bullied at school are at heightened risk for ongoing internalizing problems, and in particular for depression [1]. Consistent with hypotheses, facilitative parenting, peer acceptance and friendships predicted changes in depression over time, with higher levels of supportive relationships predicting lower levels of later depression. Consistent with previous research [8], child friendedness protected children from the internalizing impacts of victimization; only children with low levels of friendedness were at risk for worsening internalizing problems due to victimization. Child friendedness also moderated the course of internalizing problems, with high levels of friendedness ameliorating the risk associated with previous internalizing problems. Despite very little research in this area, at least two other studies support the importance of children’s friendships to the progression of internalizing problems: one study [16] found that children’s friendships moderated the impact of social isolation on later internalizing, and another [48] found that lower levels of friendedness in middle childhood predicted higher adolescent internalizing. Together, these finding suggest that children’s friendships play an important role in safeguarding children’s emotional health.

Results of mediational analyses provided some insight into the mechanisms through which facilitative parenting and peer support function together to impact depression. Our findings suggest that facilitative parenting primarily impacts depression directly, consistent with previous findings that experiencing warm parenting support has a direct effect in ameliorating depression [18]. Facilitative parenting also fully mediated the impact of peer acceptance on depression, suggesting that the impact of peer acceptance on children’s depression is through the parental-child relationship. Facilitative parenting involves coaching children in social and emotional skills; so, following a situation in which a child is distressed by lack of peer support, a parent may be able to assist the child to reinterpret the situation, and plan how to address the situation, which may change how the child feels about the situation. Facilitative parenting also includes parents as gatekeepers for children’s access to peer relationships, so the mediating role of facilitative parenting may reflect the parental influence on children’s access to peers who are likely to be supportive. These findings suggest that facilitative parenting plays an important role in influencing the progression of children’s depressive symptoms. This is consistent with previous studies linking depression and facilitative parenting [27, 49].

Children involved in this study were at risk of further victimization, due to their history of previous victimization [50]. Having friends, being accepted by peers and receiving facilitative parenting all predicted reduced risk of further victimization. Children’s acceptance by same sex peers protected children from victimization in several different ways. As well as impacting victimization directly, medium or high levels of acceptance by same sex peers effectively buffered children from the risk of victimization due to previous internalizing problems or depression. Children’s victimization takes place in the peer context, so peer acceptance is likely to influence whether other children encourage, tolerate or discourage victimization. This is consistent with previous findings that students are more likely to assist when they have a positive attitude towards the victim [51]. The particular relevance of same sex relationships is consistent with same sex relationships being generally more important for support and companionship during primary school [52].

Friendships protected children from risk of ongoing victimization. For children who experienced high levels of friendships, previous overt victimization did not predict future victimization. Having medium or high levels of friendedness protected children from the risk of ongoing victimization posed by internalizing problems. So, consistent with the victimization buffering hypothesis, children’s friendships mitigated the trajectory of ongoing victimization predicted from both previous victimization and internalizing problems. This supports previous findings that friendships ameliorate increased risk of victimization predicted by previous internalizing problems [8] or children’s own social behavior [19].

Facilitative parenting also protected children from risk of ongoing victimization through several distinct mechanisms. Consistent with the victimization buffering hypothesis, children who experienced high levels of facilitative parenting were protected from increased risk in self-reported victimization due to previous victimization, or internalizing problems. This extends findings of a previous meta-analysis that supportive parenting is concurrently associated with lower rates of victimization [22]. So how might facilitate parenting influence children’s victimization in the school environment where parents are not present? The mediational analysis, with victimization as the outcome, provides some insight into the probable mechanisms of change. The impact of facilitative parenting on overt victimization was fully mediated by children’s acceptance by peers. In other words, facilitative parenting affected victimization through its positive affect on children’s peer acceptance. Facilitative parenting involves parental coaching of children’s peer skills and active support of children’s friendships, following previous findings that these are both paths to better peer acceptance [26]. The findings that facilitative parenting mainly influences victimization through its positive influence on peer relationships can be understood in terms of opportunities for parents to influence victimization. Parents are not present when victimization occurs in the school setting; this is why they often rely on school staff to address bullying. However, findings of this study show that parents can effectively influence their child’s victimization through working with their child to improve relationships with peers.

Although most findings of this study were consistent with hypotheses and previous research, some were not. Hypotheses 3 and 5 predicted that supportive peer relationships would mediate relationships between internalizing and victimization. This was based on previous findings that loneliness mediated later depression following negative peer experiences [17], and that having a friend who stood up for the child mediated the impact of internalizing on victimization [8]. However, a lack of significant longitudinal associations between internalizing and victimization variables in this study precluded mediation. A recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies [7] concluded that victimization and internalizing problems significantly predicted increases in each other over time. However, amongst studies included, some did not find significant results for the impact of victimization on internalizing problems [53], or the impact of internalizing problems to victimization [54]. Furthermore, the overall effect sizes reported were small for the impact of internalizing on victimization (r = .08 equivalent to d = .16) and small to moderate for the effect of victimization on internalizing (r = .18 equivalent to d = .37). The current study was not powered to detect small effect sizes. The meta-analysis also reported stronger effects for studies using the same respondent for internalizing and victimization. This is consistent with the current study in that, on child report measures, the association between victimization and internalizing feelings was close to significance. Another contributing factor to the lack of association between measures of victimization and internalizing problems in the current study may be the nature of the sample. The current sample was distinctive from most other studies in that all children had previously been bullied.

This study was the first to investigate the mechanisms through which facilitative parenting impacts internalizing problems and depression, and was also the first study, to our knowledge to investigate mechanisms through which supportive parenting in general influences peer victimization over time. It also contributed to the small number of studies investigating how friendships and positive peer relationships protect children from victimization and internalizing problems. Strengths of this study include a longitudinal design, theoretically based hypotheses which extended previous research questions, and the use of multiple informants. Future research on this topic could test the generalizability of these results using a larger and more diverse sample and different measures including diagnostic measures of anxiety as well as depression.

This study identified several mechanisms through which facilitative parenting influenced children’s victimization and depression. Firstly, facilitative parenting appears to have a direct effect on depression, as well as an indirect effect through it enhancement of peer acceptance which in turn protects children from ongoing depression. Secondly, facilitative parenting impacts victimization primarily through its positive influence on supportive peer relationships. Third, high levels of facilitative parenting negate the risk of further victimization that would be expected due to previous victimization or internalizing problems.

This study builds on previous research on how children’s friendships and positive relationships with peers influence their ongoing outcomes. Consistent with previous research, the stress buffering hypothesis and the victimization buffering hypothesis, children’s friendships were found to mitigate risk of internalizing problems from both previous victimization and previous internalizing problems. Friendships also buffered children from the risk of future victimization associated with past victimization. Children’s acceptance by same sex peers was found to protect children from the risk of victimization due to previous internalizing problems and depressive symptoms.

In conclusion, this study confirmed the importance of supportive relationships with both parents and peers for children bullied by peers. This reinforces the importance of, not only addressing bullying in schools, but enabling children who are victims of bullying to build ongoing effective relationships with peers. Typically, the onus on supporting children who are victims is on schools. This study shows that parents also have a very important role to play in enabling this peer support.

Summary

Children who are bullied by peers have increased risk of ongoing victimization, internalizing problems and depression. Supportive relationships may protect children from these risks. Previous research has investigated some of the mechanisms through which supportive peer relationships buffer children from ongoing victimization and internalizing problems. Despite evidence that parenting can also protect against both depression and victimization, little is known about the mechanisms behind this. This study investigated how facilitative parenting and supportive peer relationships mitigated peer victimization and depressive symptoms over time for 111 children who were bullied by peers at school and participated in the RCT of Resilience Triple P. Higher levels of facilitative parenting and peer acceptance predicted lower later levels of both depression and victimization. The relationship between facilitative parenting and victimization was fully mediated by peer acceptance, meaning that facilitative parenting affects victimization primarily through its positive influence on children’s relationships with peers. The relationship between peer acceptance and depression was fully mediated by facilitative parenting; this was attributed to parental support compensating for different levels of peer support, as well as the gatekeeper role played by parents in influencing children’s opportunities to develop relationships and gain support of peers. Children’s friendships, acceptance by same sex peers and facilitative parenting all played roles in moderating children’s ongoing risk of victimization and internalizing problems. It was concluded that supportive relationships with both parents and peers play complementary and important roles in protecting children against ongoing victimization and internalizing problems. Better support could be provided to children who are bullied by peers at school by engaging parents as well as schools in providing emotional support, coaching and encouraging supporting peer relationships.

References

Hawker DS, Boulton MJ (2000) Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41:441–455

Arseneault L, Milne BJ, Taylor A, Adams F, Delgado K, Caspi A, Moffitt TE (2008) Being bullied as an environmentally mediated contributing factor to children’s internalizing problems: a study of twins discordant for victimization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162:145–150

Sourander A, Jensen P, Rönning JA, Niemelä S, Helenius H, Sillanmäki L et al. (2007) What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” study. Pediatrics 120:397–440

Farrington DP, Loeber R, Stallings R, Ttofi MM (2011) Bullying perpetration and victimization as predictors of delinquency and depression in the Pittsburgh Youth Study. J Aggress Confl Peace Res 3(2):74–81

Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Burr JE, Cullerton-Sen C, Jansen-Yeh E, Ralston P (2006) A longitudinal study of relational and physical aggression in preschool. J Appl Dev Psychol 27(3):254–268

Boulton MJ, Smith PK (1994) Bully/victim problems in middle-school children: stability, self-perceived competence, peer perceptions and peer acceptance. Br J Dev Psychol 12(3):315–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.1994.tb00637.x

Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ (2010) Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse Negl 34:244–252

Hodges EVE, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM (1999) The power of friendship: protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Dev Psychol 35:94–101

Bowes L, Maughan B, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L (2010) Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: evidence of an environmental effect. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:809–817

Rutter M (1985) Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry 147:598–611

Rutter M (1987) Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry 57:316–331

Olweus D (1993) Victimization by peers: antecedents and long-term outcomes. In: Rubin KH, Asendorpf JB (eds) Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Hillsdale, pp 315–341

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98:310–357

McLaughlin KA, King K (2015) Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43(2):311–323

Weeks M, Ploubidis GB, Cairney J, Wild TC, Naicker K, Colman I (2016) Developmental pathways linking childhood and adolescent internalizing, externalizing, academic competence, and adolescent depression. J Adolesc 51:30–40

Laursen B, Bukowski WM, Aunola K, Nurmi JE (2007) Friendship moderates prospective associations between social isolation and adjustment problems in young children. Child Dev 78:1395–1404

Boivin M, Hymel S, Bukowski WM (1995) The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and victimization by peers in predicting loneliness and depressed mood in childhood. Dev Psychopathol 7:765–785

Bilsky SA, Cole DA, Dukewich TL, Martin NC, Sinclair KR, Tran CV et al (2013) Does supportive parenting mitigate the longitudinal effects of peer victimization on depressive thoughts and symptoms in children? J Abnorm Psychol 122:406–419

Fox CL, Boulton MJ (2006) Friendship as a moderator of the relationship between social skills problems and peer victimisation. Aggress Behav 32:110–121

Lamarche V, Brendgen M, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Pérusse D, Dionne G (2006) Do friendships and sibling relationships provide protection against peer victimization in a similar way? Soc Dev 15(3):373–393

Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE (2000) Friendship as a moderating factor in the pathway between early harsh home environment and later victimization in the peer group. Dev Psychol 36:646–662

Lereya ST, Samara M, Wolke D (2013) Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: a meta-analysis study. Child Abuse Negl 37:1091–1108

Bowes L, Maughan B, Ball H, Shakoor S, Ouellet-Morin I, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. (2013) Chronic bullying victimization across school transitions: the role of genetic and environmental influences. Dev Psychopathol 25:333–346

Healy KL, Sanders MR (2014) Randomized controlled trial of a family intervention for children bullied by peers. Behav Ther 45:760–777

Healy KL, Sanders MR, Iyer A (2015) Parenting practices, children’s peer relationships and being bullied at school. J Child Fam Stud 24:127–140

McDowell DJ, Parke RD (2009) Parental correlates of children’s peer relations: an empirical test of a tripartite model. Dev Psychol 45(1):224–235

Healy KL, Sanders MR, Iyer A (2015) Facilitative parenting and children’s social, emotional and behavioral adjustment. J Child Fam Stud 24:1762–1779

Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, Hildebrand T (1999) Preschool Feelings Checklist. Unpublished instrument, Washington University, St. Louis, USA

Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught AL, Brown K, Spitznagel E (2004) The preschool feelings checklist: a brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:708–717

Healy KL, Sanders MR (2008) Sensitivity to peer behaviour interview. Unpublished instrument, Parenting and Family Support Centre, The University of Queensland, Australia

Crick NR, Casas JF, Mosher M (1997) Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Dev Psychol 33:579–588

Crick NR, Casas JF, Ku HC (1999) Relational and physical forms of peer victimization in preschool. Dev Psychol 35:376–385

Healy KL, Sanders MR (2008) Things Kids Do. Unpublished instrument, Parenting and Family Support Centre, The University of Queensland, Australia

Asher SR, Wheeler VA (1985) Children’s loneliness: a comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. J Consult Clin Psychol 53:500–505

Asher SR, Hymel S, Renshaw PD (1984) Loneliness in children. Child Dev 55:1456–1464

Healy KL, Sanders MR (2008) Facilitative parenting scale. Unpublished instrument, Parenting and Family Support Centre, The University of Queensland, Australia

Gold MS, Bentler PM (2000) Treatments of missing data: a Monte Carlo comparison of RBHDI, iterative stochastic regression imputation, and expectation-maximization. Struct Equ Model 7:319–355

Blanca MJ, Arnau J, López-Montiel D, Bono R, Bendayan R (2013) Skewness and kurtosis in real data samples. Methodology 9:78–84

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using multivariate statistics, 5th edn. Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education, Boston

IBM (2017). SPSS Bootstrapping. http://www-03.ibm.com/software/products/en/spss-bootstrapping

Field A (2017) Bootstrapping. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNrxixgwA2M

Erdfelder E, Faul F, Buchner A (1996) GPOWER: a general power analysis program. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 28:1–11

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Kenny DA (2016) Mediation. http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm#BK

Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York

Hayes AF (2017). PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. http://afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html. Retrieved 27 Jan 2017

Mackinnon SP (2015) Mediation in health research. Presentation at Crossroads Interdisciplinary Health Conference. http://www.slideshare.net/smackinnon/introduction-to-mediation

Pedersen S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Borge AI (2007) The timing of Middle-Childhood peer rejection and friendship: linking early behavior to Early-Adolescent adjustment. Child Dev 78:1037–1051

Healy KL, Sanders MR (2016) Antecedents of treatment resistant depression in children victimized by peers. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 8:1–3

Paul JJ, Cillessen AHN (2003) Dynamics of peer victimization in early adolescence: results from a four-year longitudinal study. J Appl Sch Psychol 19:25–43

Rigby K, Johnson B (2006) Expressed readiness of Australian schoolchildren to act as bystanders in support of children who are being bullied. Educ Psychol 26:425–440

Buhrmester D, Furman W (1987) The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Dev 1:1101–1113

Schwartz D, McFadyen-Ketchum SA, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE (1998) Peer group victimization as a predictor of children’s behaviour problems at home and in school. Dev Psychopathol 10:87–99

Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, Rubin K, Klein RG (2001) Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ 323:480–484

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the children and families who participated in the RCT of Resilience Triple P, which provided the data base for this study, and for funding by the Australian Research Council, supplemented by philanthropic donations by the Butta and Filewood families. We thank Dr. Michael Ireland and Dr. Jamin Day for statistical advice. The Parenting and Family Support Centre is partly funded by royalties stemming from published resources of the Triple P—Positive Parenting Program, which is developed and owned by The University of Queensland (UQ). Royalties are also distributed to the Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences at UQ and contributory authors of published Triple P resources. Triple P International (TPI) Pty Ltd is a private company licensed by Uniquest Pty Ltd on behalf of UQ, to publish and disseminate Triple P worldwide.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors of this paper have no share or ownership of TPI. The authors of this paper, Drs Healy and Sanders are both contributory authors of Resilience Triple P and may in future receive royalties from TPI and/or consultancy fees from TPI. TPI had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or writing of this report. Drs Healy and Sanders are employees at UQ.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Healy, K.L., Sanders, M.R. Mechanisms Through Which Supportive Relationships with Parents and Peers Mitigate Victimization, Depression and Internalizing Problems in Children Bullied by Peers. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 49, 800–813 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-018-0793-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-018-0793-9