Abstract

Pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic and impairing condition that can emerge early in childhood and persist into adulthood. The primary aim of this paper is to examine the characteristics of a large sample of young children with OCD (age range from 5 to 8). The sample will be described with regard to: demographics, OCD symptoms/severity, family history and parental psychopathology, comorbidity, and global and family functioning. The sample includes 127 youth with a primary diagnosis of OCD who participated in a multi-site, randomized control clinical trial of family-based exposure with response prevention. Key findings include moderate to severe OCD symptoms, high rates of impairment, and significant comorbidity, despite the participants’ young age. Discussion focuses on how the characteristics of young children compare with older youth and with the few other samples of young children with OCD. Considerations regarding generalizability of the sample and limitations of the study are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childhood-onset obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic disturbance that affects as many as 2–3 % of children [1]. As high as it is, this figure may underestimate the true magnitude of the problem in children under the age of 9 years (herein referred to as “early childhood onset OCD”) because until recently most people were not looking for OCD in children in this age range. To date, the term juvenile onset has been used to refer to cases that begin at any point in childhood or adolescence.

Most prior studies of juvenile OCD have reported a mean age of OCD onset of about 10 years (range 6–14 years) and have varied widely in terms of the mean chronological age of the sample at the time of assessment (range 9–19). These studies have suggested that, relative to adult cases, juvenile cases show: a male preponderance [2–5], familial aggregation of OCD and tic disorders [6–9], and high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, especially with disruptive behavior disorders, other anxiety disorders, and tic disorders [2, 5, 9–13]. Further, juvenile cases are more likely to present with compulsions only [2, 12–14], higher rates of aggressive obsessions, and higher rates of hoarding [13, 15]. In addition, their compulsions may be difficult to differentiate from tics [16].

Only recently have studies begun to investigate OCD in younger children. In a prior report by Garcia et al., using data from the pilot sample for the present investigation, our group examined developmental differences in phenotypic presentation among youth at the younger end of the juvenile age range (aged 4–8) [17]. Relative to most other samples, our pilot sample was younger at the time of assessment and had an earlier age of OCD onset. Results from the pilot sample suggested that children with early childhood onset OCD could have fully developed OCD, not just a prodromal phase or subthreshold version of the illness. Despite their young age, the majority of youth in our pilot sample had multiple diagnoses. Comorbidity rates for many of the anxiety disorders [i.e., generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), specific phobias, and social anxiety disorder] were comparable to those reported in older juvenile onset samples [4, 15]. Consistent with general developmental trends [18], and data about the age of onset of depression as a comorbid condition among youth with OCD [12], lower rates of comorbid depressive disorders were observed in our pilot sample than in older juvenile onset samples. The mean number of obsessions and compulsions reported were similar to those reported in older juveniles [3].

The only other studies to investigate this young age group include a pilot trial of family-based E/RP conducted by Lewin and colleagues [19] and a study focused on describing OCD in very young children [20] which includes the Lewin et al. [19], trial. Lewin and colleagues [19] compared family-based E/RP with treatment as usual among 31 youth (ages 3–8) with a primary diagnosis of OCD. Selles et al. [20] compared younger (ages 3–9) to older (ages 10–18) youth from a sample of 292 treatment seeking youth with a primary diagnosis of OCD. Results from these studies were largely similar to those of our pilot trial in that young children presented with obsessive and compulsive symptoms at similar severity levels to those seen in older youth and had high rates of comorbidity. In addition, Selles et al. [20] found that younger children (ages 3–9) were less likely to have comorbid depressive disorders and more likely to have comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and older youth were more likely to be taking antidepressants. Taken together, these few studies focused on young children with OCD point to both similarities and differences between younger and older groups of youth. Further description of early childhood onset OCD is needed to better understand the presentation and potentially unique characteristics of this group.

The present study provides a unique opportunity to describe the phenomenology of treatment-seeking youth with OCD who were 5–8 years of age when they presented for treatment. This sample is larger than our pilot sample [21] and presented to two other academic medical centers (University of Pennsylvania and Duke University) in addition to the site for the pilot study (Brown Medical School). By achieving a larger sample size and having assessments occur at multiple sites, the aim is to lend further credence to the case for recognizing OCD in very young children, and to shed light on the specifics of their clinical picture.

Method

Participants

The sample includes 127 children between the ages of 5–8 years. At study entry, each participant received a primary DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of OCD [22]. Participants were recruited from three collaborating academic sites: The University of Pennsylvania (n = 44; 34.6 % of sample), Duke University (n = 35; 27.6 %), and Brown Medical School (n = 48; 37.8 %). The Institutional Review Boards at each institution approved the study. Participant recruitment took place between 2006 and 2011.

A three-gate assessment procedure was used to screen for eligibility. Gate A consisted of screening interviews to assess patients’ preliminary eligibility, including a preliminary telephone screen with a research assistant (Gate A) and, for those interested and appearing eligible, an in-person intake assessment (Gate B1) with a doctoral level psychologist. If eligible, participants proceeded to Gate B2, which included (1) a systematic diagnostic assessment with the parent(s) and child and (2) a team meeting to review all available data to establish caseness and suitability for study entry. Patients determined to be eligible were invited back for Gate C, a baseline visit with an independent evaluator (IE) who was blind to treatment condition.

Inclusion criteria were: a) age 5–8 years at the start of treatment b) DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of primary OCD, (c) total CY-BOCS score of 16 or greater, (d) duration of OCD symptoms for at least 3 months, (e) appropriateness for outpatient treatment, and (f) presence of a parent, or guardian, who could participate in treatment. Exclusion criteria were: (a) other primary or co-primary psychiatric disorder requiring initiation of other active treatment, (b) pervasive developmental disorder(s) (PDD), (c) intellectual disability, (d) thought disorder or psychotic symptoms, (e) conduct disorder, (f) acute suicidality, (g) concurrent psychotherapy, (h) chronic medical illness precluding active participation in treatment, (i) treatment with psychotropic medication for depression or mood stabilization, (j) treatment with medication for OCD, ADHD &/or tic disorders that was not stable for more than 8 weeks, (k) prior failed trial of adequate CBT for OCD [(defined as ten sessions of formalized exposure with response prevention (E/RP)], and (l) pediatric autoimmune disorders associated with strep (PANDAS). Given that PANDAS is by definition a prepubertal phenomenon and that children with streptococcal precipitated OCD appear to have a more episodic symptom course, we considered carefully the implications of this diagnosis for the current study of early childhood onset OCD. Our decision to exclude children with PANDAS was guided by the state of the PANDAS literature in 2006 when our study was funded.

Assessment Measures

The baseline evaluation included ratings and assessments by the psychologist assessing the participant at gates B1 and B2, ratings by the IE assessing the participant at gate C, and self-and parent-report measures administered at gate C.

OCD Symptoms and Severity were measured using the Child Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) [23] and the Clinical Global Improvement scale (CGI) [24]. The CY-BOCS is a “gold standard” clinician interview yielding a combined obsessions and compulsions total score (0–40) and demonstrating adequate reliability and validity [23]. Developmentally sensitive anchors and probes were developed. The literature supports the use of the measure in children as young as 6 years [25] and it was used successfully in our prior studies with 5-year-olds [21]. Internal consistencies of the CYBOCS 10-item total severity scale in the current sample were adequate for child-report (α = 0.74) and strong for parent-report (α = 0.88). The CGI is a 7-point scale measuring clinician-rated improvement in treatment and shows adequate reliability and validity [26, 27].

General Functioning was measured using the Children’s OCD Impact Scale—Revised (COIS-R) [28] and the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) [29, 30]. The COIS-R provides a standardized format for assessing the impact of OCD on social, school, and home functioning and shows excellent internal consistency and adequate concurrent validity [28]. Item scores range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much) with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment. Clinical age and gender norms are available for this measure. Internal consistency in the current sample was strong (α = 0.90) based on 31 items. Two items (“going on a date;” “having a boyfriend or girlfriend”) were removed from the scale given the young age of the current sample and the fact that there was zero endorsement of these items. The CGAS measures global functioning, with scores over 70 indicating normal adjustment. It has been shown to have adequate reliability, validity, and internal consistency [30].

Quality of Life was measured using the Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q). The PQ-LES-Q is a 15-item scale measuring quality of life (QOL) in a variety of domains. The scale has solid psychometric properties with excellent internal consistency and adequate concurrent validity [31]. We used a parent report of this measure, based on the finding that close relatives are able to give accurate proxy ratings on QOL measures [32]. Internal consistency in the current sample was strong (α = 0.89).

Demographics were measured using the Conners March Developmental Questionnaire (CMDQ) [33], including age, grade level, gender, race, and socioeconomic status, and was completed by parents.

Comorbidity was assessed using several measures. The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-P/L) [34, 35] is a semi-structured, clinician-rated interview that yields DSM-IV diagnoses and has favorable psychometric properties. Interviews were administered to the parent(s) (or primary caretakers) regarding the child, and to children (although 5–6 year old children varied in their ability to participate actively in the interview). The K-SADS is routinely used to assess psychiatric diagnoses in children as young as 5 years [36, 37].

The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) [38] is a clinician-rated scale used to assess tic severity and impairment. The YGTSS has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties with solid internal consistency, excellent inter-rater reliability, and excellent convergent and divergent validity [38]. Tic status was determined by integrating information from the K-SADS and YGTSS in order to identify those with any past or current tics. The YGTSS checklist summary item, in which the clinician indicates whether the child has no tics, motor tics only, vocal tics only, or both motor and vocal tics, was the basis for identifying the type of tics present. The K-SADS was used as the basis for identifying the age of onset and duration of tics.

The Child Behavior Checklist—Parent Report Form (CBCL) [39] is a parent-rated scale that assesses an array of behavioral problems in children ages 6–18 years and has well established psychometric properties. For children aged 5 years, the CBCL 1.5–5-Parent Report form [40], an adaptation of the CBCL for preschool age children, was used. Internal consistencies for both the 6–18 and 1.5–5 year-old versions were strong in the current sample (α = 0.93 and α = 0.90, respectively).

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders—revised, parent version (SCARED-R) [41, 42] is a 66-item parent-reported scale of severity of anxiety symptoms in youth. The measure has demonstrated good internal consistency and concurrent and discriminant validity [43]. Internal consistency in the current sample was strong (α = 0.94).

Features of PDD were screened using the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) and the Social Responsiveness Questionnaire (SRS). The SCQ is a 40-item parent report that measures behaviors characteristic of autism spectrum disorders including communication skills and social functioning, with scores 15 or greater indicating a possible autism spectrum diagnosis (ASD). The measure has demonstrated good internal consistency and concurrent validity [44]. The SRS is a 65-item parent report that assesses abilities and deficits in social reciprocity in children ages 4–18 years. It has good internal consistency, temporal stability, and concurrent and discriminant validity [45]. In the current sample, internal consistencies for the SCQ and SRS were adequate to strong (α = 0.78 and α = 0.92, respectively).

Parent Psychopathology was assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) [46], a measure yielding scores for Depression (DASS-D), Anxiety (DASS-A), and Stress (DASS-S). The DASS has been shown to have excellent psychometric properties in clinical [47, 48] and non-clinical samples [49]. Parents also completed the Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R) [50], a brief (18 items) instrument measuring obsessive–compulsive symptoms in six domains. It has excellent discriminant validity, good convergent validity, and good test–retest reliability [50]. In the current sample, internal consistencies of the DASS-21 and OCI-R were strong (α = 0.90 and α = 0.95, respectively).

Family Functioning was assessed using the Family Assessment Measure-III Short Form (Brief FAM III) [51], which was independently administered to each parent and provides a global index of family dysfunction. The Brief FAM-III was derived from the original FAM-III, which possesses good psychometric performance in terms of both internal consistency and construct validity. Family Accommodation was measured using items from the Family Accommodation Scale—Self Rated Version (FAS-SR) [52] completed by parents. The FAS-SR has adequate reliability and validity. The internal consistency of the Brief FAM-III was adequate (α = 0.76) in the current sample. The internal consistency of the FAS-SR was strong (α = 0.85).

Quality Assurance To ensure consistent administration of the study interviews and rating scales, the IEs were trained to a reliable standard on the K-SADS, CY-BOCS, and CGI and were required to tape each interview conducted at every study time point. Tapes were randomly selected on a monthly basis and reviewed on a cross-site IE reliability call to ensure consistent, standardized administration of the IE battery. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between each rater and the consensus rating, with coefficients above 0.85 deemed acceptable. Summary statistics were kept on primary outcome measures and evaluated on a quarterly basis to identify potential problems with inter-rater reliability. In addition, tapes from 20 % of the sample were randomly selected and reviewed by a second trained evaluator at one of the study sites for diagnostic reliability on the K-SADS.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the POTS Jr. sample characteristics. Frequencies and percentages are presented for categorical data. Means, standard deviations, medians, and ranges are used to summarize the continuous variables. In most instances, descriptive statistics are based on N = 127, but in the event of missing data, n is the number of cases with data recorded.

Results

Recruitment and Screening

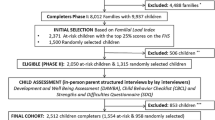

The flow of participants through the study is shown in Fig. 1. Some participants were excluded for multiple reasons; therefore, there are more reasons for exclusion than excluded participants at some gates. In total, of the 452 participants screened at gate A, 127 (28 %) were randomized into the study. Primary reasons for study exclusion included: OCD symptoms not severe enough, other primary diagnosis, concurrent treatment or prior CBT (with >10 sessions).

Demographic Characteristics

Sample demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Youth ranged in age from 5 to 8 years with an average age at presentation of 7.22 (SD = 1.12). Roughly half of the participants were female (52.8 %). With regard to ethnicity, 91 % of the sample described themselves as non-Hispanic, 5 % Hispanic/Latino, and 4 % did not endorse a category. In terms of race, the sample was 89.8 % White, 2.4 % Asian, 1.6 % African American/Black, 3.1 % multi-racial, and 3.1 % not endorsed/missing. The majority of parents reported a college degree or higher (70.9 % of fathers, 78.3 % of mothers). The majority of participants had parents living together (90.2 %) and modal yearly family income was above $100,000 (46.6 %), with 81.9 % making over $60,000. Almost one-third of cases had birth complications involving breathing problems/lack of oxygen (29.9 %), and 15.7 % were born preterm.

Treatment History

Although ten sessions or more of OCD-specific CBT including E/RP was an exclusion for entry into the study, 22.8 % of cases reported prior treatment for OCD symptoms, a small fraction of which identified that prior treatment as CBT (4.7 %). Almost 12 % (n = 15) of the sample had taken a psychiatric medication. At study entry, stable doses of the following medications were being taken by participants: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) (3.9 %), stimulants (1.6 %), Other (risperidone, atamoxetime, or guanfacine; 2.4 %).

OCD Severity, Course, and Symptoms

Information about OCD in this sample is presented in Table 1. By design, all participants met criteria for a primary diagnosis of OCD. Average age of onset of OCD symptoms was 5.06 (SD = 1.65, range 2–8), based on available data (n = 87) from parent report on the K-SADS. Average duration of illness ranged from 2.1 months to 5.96 years (M = 2.07, SD = 1.36).

The mean CYBOCS score was 25.55 (SD = 4.23), indicating severe OCD symptoms. Obsession and compulsion subscale totals represented roughly half of the total score (Obsessions M = 12.12, SD = 2.67; Compulsions M = 13.39, SD = 2.30). The majority of the sample (73 %) endorsed multiple obsessions with an average of 4.16 (SD = 3.30) obsessions. Ninety percent of the sample endorsed multiple compulsions, with an average of 5.76 (SD = 3.52) compulsions. About half of the sample (55 %) was classified as “markedly” or “severely” ill on the CGI-Severity scale. The COIS-R was used to assess the impact of OCD symptoms on child functioning from parent report. Mean scores for males and females from the COIS-R were calculated separately to allow for comparison with clinical age and gender norms. The mean total score for females was M = 21.27 (SD = 14.36), which is slightly lower than the available clinical norm (M = 26.26, SD = 13.60). The mean total score for males was M = 24.35 (SD = 13.74), which is comparable though slightly lower than the available clinical norm (M = 27.56, SD = 19.71). Overall, these scores suggest functional impairment similar to that reported by same aged peers.

Global Functioning, Family Functioning, and Quality of Life

Information about functioning is reported in Table 1. Clinician-rated and parent-report measures were used to assess global functioning. The mean score on the CGAS was in the “variable interference in functioning” range, M = 52.89 (SD = 8.78). Parent report on the Brief FAM-III showed significant impairment across most domains measured (Overall T = 77.46, SD = 8.68). The total score on the FAS-SR was M = 22.85 (SD = 14.14), which is higher than the mean reported in an adult sample using this measure [52], but since there are no other child studies to date that have used this measure it is not clear how it compares to other child samples. To aid interpretation, the item-level mean was 1.20 (SD = 0.75), which suggests that family members are accommodating symptoms between one and three days per week. The parents’ report on their child’s overall quality of life on the PQ-LES-Q was in the “fair” range, M = 3.71 (SD = 0.60).

Comorbidity

Psychiatric comorbidity data are presented in Table 2. Fifty-eight-percent of the sample had one or more comorbid diagnoses. Specific phobias, GAD, ODD, tic disorders, and ADHD were the most common comorbid conditions. In general, comorbid internalizing disorders were more common (71.7 %) than comorbid externalizing disorders (22.0 %).

Comorbidity was also assessed using parent-report measures. On the CBCL, the mean total T-scores for both the 6–18 year old version (T = 62.08, SD = 8.57) and the preschool version given to 5-year olds in this sample (T = 58.84, SD = 8.01) were below the clinical range, as were the Internalizing T-scores for the 6–9 year olds (T = 64.46, SD = 8.92) and the 5-year olds (T = 63.11, SD = 7.10). However, on a more anxiety-specific measure, the parent report on the SCARED-R was above the clinical cut-off of 25 (M = 39.27, SD = 18.29). Given the concern about possible overlap with an ASD, special attention was given to assessing social relatedness. On the SCQ, participants scored well below the cutoff score of 15 used as an indication of a possible ASD (M = 5.74, SD = 4.26). Interpersonal behavior assessed with the SRS was also in the normal range for this sample (T = 58.29, SD = 11.21). Twenty-nine children had current tics (motor only: n = 5, vocal only: n = 4, both motor and vocal: n = 14, transient tic disorder: n = 6, past tics only: n = 3) and YGTSS data was complete for 19 of these children. The mean scores for total tic severity (M = 13.33, SD = 9.20), motor tic severity (M = 6.95, SD = 6.20), and vocal tic severity (M = 7.21, SD = 5.81) fell in the mild range.

Family History and Parental Psychopathology

Family history data are reported in Table 1. Family histories in a 1st degree relative were as follows: 16.4 % OCD, 22.9 % other anxiety disorder, 3.3 % tic disorder, and 14.7 % depressive disorder. Maternal-self reports on the DASS-21 revealed normative levels of depression (M = 2.36, SD = 3.11) anxiety (M = 2.31 SD = 2.86) and stress (M = 6.81, SD = 4.57). Paternal self-reports on a smaller sample of fathers (n = 63) revealed the same pattern for depression (M = 2.00, SD = 2.59) anxiety (M = 1. 12 SD = 2.09) and stress (M = 5.16, SD = 3.70). Parent self-report of OC-symptoms on the OCI-R was: M = 11.35, SD = 11.19, which is below the level reported for the non-anxious control group in the OCI-R validation study [50].

Discussion

The present data provide a unique opportunity to further understand the phenomenology of OCD in young children. There are few other studies focused on this age group. The pilot sample for the present investigation [21] (details of the sample reported in Garcia et al. [17] ) and Lewin et al.’s [19] pilot trial are the only other clinical trials of E/RP for youth of this age group and Selles et al. [20] is the only other study focused on describing OCD in very young samples. Even studies that are focused on comparing younger to older groups of youth tend to only include children as young as six [21, 53, 54] or split age groups around age 10 or 12 [15, 55]. In general, the current results are similar to previous studies of both younger and older children in terms of symptom presentation and severity. However, this very young sample also demonstrated some differences from older samples.

Symptoms tended to be in the severe range (mean CYBOCS = 25.55), providing further evidence that young children present with fully developed OCD and not a prodromal or subthreshold version of the illness. This level of severity is notable given the very young age of the sample and is consistent with the few studies of young children [19, 56]. Importantly, results provide further evidence that severity levels in young children are similar to those observed in older youth samples [55–59]. Regarding specific symptoms, this sample endorsed a mean number of obsessions and compulsions similar to that of older juvenile samples [3] and slightly greater than that reported in younger juvenile samples [21, 56].

Overall functional impairment as measured with the COIS-R was comparable to available matched age and gender norms. Mean scores for males and females in the current sample were slightly lower than the available norms; however, norms for this age range (ages 6–8) were based on much smaller sample sizes than available in the current study. Means from the current sample may more accurately reflect typical scores for youth aged 6–8, though more research is needed to better understand the measurement of functional impairment in young children. Family functioning was quite impaired in this sample, especially levels of family accommodation, although, in contrast, parent self-report of mental health symptoms was in the non-clinical range. However, many parents disclosed a mental health history of OCD and other anxiety disorder as well as depressive disorders. Of note, the level of family impairment was very similar to what was reported in the POTS II study [60], a multi-site randomized clinical trial of youth (ages 7–17) with OCD who were partial responders to a full medication trial. This similarity is striking given that youth in the POTS II trial [60] were older (longer duration of illness) and considered quite severe given the need for treatment augmentation following partial response to a Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SRI). Quality of life scores in the current sample were also similar to those reported in the POTS II trial.

Consistent with very young OCD samples [17, 19] and with juvenile OCD samples in general [56, 60], comorbidities were the rule rather than the exception. The patterns of comorbidity in this sample provide some support for an early onset subtype of OCD and are both similar and different to comorbidity rates in other young samples. The most frequent comorbid disorders were specific phobia, GAD, ODD, ADHD, and tic disorders. There was a very low incidence of depressive disorders. Similar rates of comorbidity were found for many specific anxiety disorders in comparison to Mancebo et al. [54], though Lewin et al. [19] reported somewhat higher rates of GAD, separation anxiety, and social anxiety. The differences in rates reported by Lewin et al. [19] may be due in part to the fact that the mean age in their sample was approximately 1.5 years younger than either the current or Mancebo et al. [54] samples. Differences may also be related to specific confounds such as varying assessors and recruitment strategies. Though common, the current sample had slightly lower rates of ADHD and ODD than Garcia et al. [17] and Selles et al. [20]. Compared to older juvenile samples, findings confirm that younger OCD samples tend to have higher rates ODD and specific phobias [54, 55, 60] as well as tics [55, 60–62], and lower rates of depressive disorders. This pattern of comorbidities at different ages is in line with what would be expected developmentally.

Some have posited that there is an early onset subtype of OCD. Hypothesized features of this subtype include male preponderance, high rates of family history of OCD and/or tic disorder, and high rates of comorbidity with tic and disruptive behavior disorders. Garcia et al. [17] reported mixed support for this hypothesis and the current results mirror those findings by providing support for the familiarity and comorbidity features but not the male preponderance feature. Rates of comorbid ODD and tic disorders were high in the current sample and at rates similar to Garcia et al. [17]. The rate of first-degree relatives reporting a history of OCD (16.4 %) was also similar to the rate reported by Garcia et al. [17], though the rate of family history of tic disorders was lower. A male preponderance was not found, with the gender breakdown fairly evenly divided between males (47.2 %) and females (52.8 %). Though often included as a hypothesized feature of an early onset subtype, the pediatric OCD literature is somewhat split on the issue of gender. Many studies of treatment seeking youth have found a similarly even representation of males and females [17, 20, 53, 63] while others have found a male preponderance in OCD prior to age 18 [4, 5, 19]. Of studies with very young juvenile samples, only Lewin et al. [19] reported a male preponderance. In addition, there is some evidence that juvenile cases are more likely to present with compulsions only [2, 12–14]; however, this was not the case in the current sample. Not only did the majority of youth in the current sample endorse obsessions, but also most reported multiple obsessions.

In sum, the current sample provides further evidence that young children not only have fully developed OCD but that they present with a level of severity similar to their older juvenile counterparts. These youth are both similar to and different from the few other very young OCD samples; we see similarities in the frequencies of specific symptoms and pattern of comorbidities, yet this sample does not show the male preponderance reported in Lewin et al. [19]. Compared to older children, these children also present with high rates of comorbidities, but the incidence of specific comorbid disorders seems to differ between age groups. ODD, specific phobias, and tics were more common in the current sample and depression is more common in older juvenile samples. Support for an early onset subtype of OCD was mixed, with more similarities than differences between this very young cohort and older juvenile cohorts.

There are several limitations of this study that warrant mention. The first is in regards to the generalizability of our findings given the sample’s lack of racial/ethnic diversity. This trend towards low enrollment of ethnic and racial minorities is unfortunately consistent with the extant OCD literature across the developmental spectrum, and yet persists despite similar prevalence rates reported across different minority groups in multiple, large epidemiological studies [64]. These difficulties were anticipated, and yet despite substantial efforts to enhance the racial and ethnic diversity of our sample, our efforts still fell short in this regard. This is a significant weakness and leaves the applicability of our findings to a broader range of ethnic and racial groups in question. Similarly, the lack of socioeconomic diversity in the sample is a concern. Related, the sample was ascertained through specialty clinics well known in each site’s respective community for the treatment of OCD and may not be representative of the community.

Summary

The results presented provide a detailed picture of early childhood onset OCD. The severity of the OCD symptoms, number of comorbid diagnoses, and associated impairments, especially in family functioning, underscore the need for interventions targeted at this very young group of children. If left untreated, this group is likely at an increased risk for OCD to disrupt normative development and to extend into later childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. By characterizing these children in detail, we are in a good position to continue research on how to best treat this very young group of children with OCD.

References

Valleni-Basile LA, Garrison CZ, Jackson KL et al (1995) Frequency of obsessive–compulsive disorder in a community sample of young adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:128–129

Swedo SE, Rapoport JL, Leonard HL, Lenane M, Cheslow D (1989) Obsessive compulsive disorders in children and adolescents: clinical phenomenology of 70 consecutive cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:335–343

Hanna GL (1995) Demographic and clinical features of obsessive–compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:19–27

Masi G, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Bertini N, Milantoni L, Arcangeli FA (2005) Naturalistic study of referred children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:673–681

Masi G, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Bertini N, Pfanner C, Arcangeli F (2006) Cormorbidity of obsessive–compulsive disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in referred children and adolescents. Compr Psychiatry 47:42–47

Pauls D, Alsobrook JP, Goodman WK, Rasmussen SA, Leckman JF (1995) A family study of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 152:76–84

Nestadt G, Samuels J, Riddle M et al (2005) A family study of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:358–363

Lenane MC, Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Pauls D, Sceery W, Rapoport JL (1990) Psychiatric disorders in first degree relatives of children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29:407–412

Chabane N, Delorme R, Millet B, Mouren MC, Leboyer M, Pauls D (2005) Early-onset obsessive–compulsive disorder: a subgroup with a specific clinical and familial pattern? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46:881–887

Leonard HL, Lenane MC, Swedo SE, Rettew DC, Gershon ES, Rapoport JL (1992) Tics and Tourette’s disorder: a 2-to 7-year follow up of 54 obsessive–compulsive children. Am J Psychiatry 149:1244–1251

Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF, Curi M et al (2005) A family study of early-onset obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Genetics 136B:92–97

Geller DA, Biederman J, Griffin S, Jones J, Lefkowitz TR (1996) Comorbidity of juvenile obsessive–compulsive disorder with disruptive behavior disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:1637–1646

Geller DA, Biederman J, Jones J et al (1998) Is juvenile obsessive–compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:420–427

Rettew DC, Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Lenane MC, Rapoport JL (1992) Obsessions and compulsions across time in 79 children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:1050–1056

Geller DA, Biederman J, Faraone S et al (2001) Developmental aspects of obsessive compulsive disorder: findings in children, adolescents, and adults. J Nerv Ment Dis 189:471–477

Eischstedt JA, Arnold SL (2001) Childhood-onset obsessive–compulsive disorder: a tic-related subtype of OCD? Clin Child Fam Psych 21:137–158

Garcia AM, Freeman JB, Himle MB et al (2009) Phenomenology of early childhood onset obsessive compulsive disorder. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 31:104–111

Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A (2003) Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:837–844

Lewin AB, Park JM, Jones AM et al (2014) Family-based exposure and response prevention therapy for preschool-aged children with obsessive–compulsive disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 56:30–38

Selles RR, Storch EA, Lewin AB (2014) Variations in symptom prevalence and clinical correlates in younger versus older youth with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45:666–674

Freeman JB, Garcia AM, Coyne L et al (2008) Early childhood OCD: preliminary findings from a family-based cognitive-behavioral approach. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:593–602

American Psychological Assocation (2007) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR)

Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggan-Hardin M et al (1997) Children’s Yale-Brown obsessive–Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:844–852

Guy W (1976) The clinical global impression scale. The ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology-Revised (DHEW Publ No ADM 76-338) Rockville, MD, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs: 218–222

March J, Leonard HL (1998) Obsessive–compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. In: Swinson RP, Antony MM, Rachman S, Richter MA (eds) Obsessive–compulsive disorder: theory, research, and treatment. The Guildford Press, New York, pp 367–394

Garvey MA, Perlmutter SJ, Allen AJ et al (1999) A pilot study of penicillin prophylaxis for neuropsychiatric exacerbations triggered by streptococcal infections. Biol Psychiatry 45:1564–1571

Perlmutter SJ, Leitman SF, Garvey MA et al (1999) Therapeutic plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin for obsessive–compulsive disorder and tic disorders in childhood. Lancet 354:1153–1158

Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL, Chang S, Jaffer M (2007) Functional impairment in childhood OCD : development and psychometrics properties of the Child Obsessive–Compulsive Impact Scale–Revised (COIS-R). J Clin Child Adolesc 36:645–653

Green B, Shirk S, Hanze D, Wanstrath J (1994) The children’s global assessment scale in clinical practice: an empirical evaluation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33:1158–1164

Schaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. (1983) A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 40:1228–1231

Endicott J, Nee J, Yang R, Wohlberg C (2006) Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment And Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q): reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:401–407

Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, Detmar SB, Wever LD, Schornagel JH (1998) Comparison of patient and proxy EORTC QLQ-C30 ratings in assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol 51:617–631

Conners CK, March J (1996) The Conners/March Developmental Questionnaire. MultiHealth Systems Inc, Toronto

Chambers WJ et al (1985) The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: test–retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and Schizophrenia for school-age children, present episode version. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42:696–702

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U et al (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and Schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:980–988

Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J (2002) Rationale and principles for early intervention with young children at risk for anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 5:161–172

Youngstrom EA, Gracious BL, Danielson CK, Findling RL, Calabrese J (2003) Toward an integration of parent and clinician report on the Young Mania Rating Scale. J Affect Disorders 77:179–190

Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT et al (1989) The Yale global tic severity scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28:566–573

Achenbach T, Rescorla L. (2001) Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families, Burlington, VT

Achenbach T, Rescorla L (2000) Manual for ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families, Burlington, VT

Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D et al (1997) The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:545–553

Muris P, Merckelbach H, van Brakel A, Mayer B (1999) The revised version of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED-R): further evidence for its reliability and validity. Anxiety Stress Coping 12:411–425

Muris P, Steerneman P (2001) The revised version of the screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED–R): first evidence for its reliability and validity in a clinical sample. Brit J Clin Psychol 40:35–44

Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C (2003) Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ). Western Psychological Service, Los Angeles

Constantino JN, Gruber CP (2005) Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 33:335–343

Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP (1998) Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess 10:176–181

Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH (1997) Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther 35:79–89

Clara IP, Cox BJ, Enns MW (2001) Confirmatory factor analysis of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in depressed and anxious patients. J Psychopathol Behav 23:61–67

Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S et al (2002) The obsessive–complusive Inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess 14:485–495

Skinner H, Steinhauer P, Santa-Barbara J (1995) Family Assessment Measure-III (FAM-III). Multi-Health Systems, North Tonawanda

Pinto A, Van Noppen B, Calvocoressi L (2013) Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a self-rated version of the family accommodation scale for obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Obsess Compuls Rel 2:457–465

Farrell L, Barrett P, Piacentini J (2006) Obsessive–compulsive disorder across the developmental trajectory: clinical correlates in children, adolescents and adults. Behav Change 23:103–120

Mancebo MC, Garcia AM, Pinto A et al (2008) Juvenile-onset OCD: clinical features in children, adolescents and adults. Acta Psychiatr Scand 118:149–159

Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Chang S et al (2011) Controlled comparison of family cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation/relaxation training for child obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:1149–1161

Garcia AM, Sapyta JJ, Moore PS et al (2010) Predictors and moderators of treatment outcome in the pediatric obsessive compulsive treatment study (POTS I). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:1024–1033

Freeman J, Choate-Summers M, Garcia A et al (2009) The pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder treatment study II: rationale, design and methods. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 3:4

Storch EA, Bussing R, Small BJ et al (2013) Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy alone or combined with sertraline in the treatment of pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther 51:823–829

Farrell L, Waters A, Milliner E, Ollendick T (2012) Comorbidity and treatment response in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder: a pilot study of group cognitive-behavioral treatment. Psychiat Res 199:115–123

Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB et al (2011) Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder: the pediatric OCD treatment study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 306:1224–1232

Farrell L, Barrett P (2006) Obsessive–compulsive disorder across developmental trajectory: cognitive processing of threat in children, adolescents and adults. Brit J Psychol 97:95–114

Nakatani E, Krebs G, Micali N, Turner C, Heyman I, Mataix-Cols D (2011) Children with very early onset obsessive compulsive disorder: clinical features and treatment outcome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52:1261–1268

Storch EA, Geffken GR, Merlo LJ et al (2007) Family accommodation in peditric obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc 36:207–216

Williams M, Powers M, Yun Y, Foa E (2010) Minority participation in randomized controlled trials for obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 24:171–177

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skriner, L.C., Freeman, J., Garcia, A. et al. Characteristics of Young Children with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: Baseline Features from the POTS Jr. Sample. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 47, 83–93 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0546-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0546-y