Abstract

Admission of a preterm or sick full-term infant to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a stressful experience for parents. Indeed, the ‘NICU experience’ may constitute a traumatic event for parents, distinct from other birth-related trauma, leading to significant and ongoing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. However, the rates at which this outcome occurs are not well understood. This review aimed to identify the prevalence of PTSD in mothers and fathers of high-risk infants admitted to the NICU, specifically focusing on the NICU experience as the index trauma. The PRISMA-P: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols were used to conduct this review. We searched PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses databases, and reference lists of included articles (1980–2021). Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts and conducted the full-text screening assessment. Of the 707 records identified, seven studies met the inclusion criteria. In this systematic review, PTSD symptomatology was assessed by self-report measures rather than a clinical interview. We identified significant variations in the methodologies and quality between studies, with a wide variation of reported prevalence rates of PTSD of 4.5–30% in mothers and 0–33% in fathers. Overall, the findings indicate that up to one-third of parents experience PTSD symptomatology related to the NICU experience. These results emphasize the importance of universal routine antenatal and postnatal screening for symptoms of PTSD to identify parents at risk of distress during the NICU experience and after discharge.

Trial registration: The study protocol was registered with Prospero registration number CRD42020154548 on 28 April 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Having a high-risk infant admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) immediately after childbirth may be an unexpected, stressful and potentially traumatic event for parents (Aftyka et al., 2014; Shaw et al., 2013). The term ‘high-risk infant’ broadly defined includes preterm and full-term infants characterized by either complex medical problems that require dependence on technology or uncertainty of survival (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008). For parents, high-risk pregnancy (Kim et al., 2015) childbirth (Galea et al., 2021; Sanders & Hall, 2018) and having an infant admitted to the NICU have been recognized as potentially traumatic events; that is, a physical or emotional response to a single or series of events that have long-term adverse impacts (Chang et al., 2016; Hynan et al., 2013). More importantly, the subsequent trauma associated with the NICU experience can have lasting consequences on parents and their family’s mental health (Chang et al., 2016; Hynan et al., 2013; Roque et al., 2017), increased levels of parent stress (Christie et al., 2019), parent–infant closeness (Feeley et al., 2016), and infant outcomes (Clottey & Dillard, 2013; Wilcoxon et al., 2021). For instance, many parents experience recurring and persistent thoughts or fears related to their infant’s life and potential death during the NICU experience (Hodek et al., 2011). For some parents, this may constitute a traumatic event over and above the trauma related to childbirth (an event that occurs during labor and delivery Beck, 2004). In general, the literature on parental posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including trauma related to childbirth and the NICU experience, describes ‘parents’ as mothers and fathers. Therefore, caregivers and others will not be discussed in this review.

Among parents, the NICU experience and childbirth exemplify a particular type of stressor recognied in the newest (5th) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2013) as meeting Criterion A, ‘exposure to actual or threatened death or serious injury’ via ‘witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurs to others’ or ‘learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member.’ For a proportion of parents, the trauma of the NICU experience and childbirth may lead to posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptoms that constitute a mental health diagnosis of acute stress disorder (ASD) and/or PTSD (Barr, 2010; Shaw et al., 2006; Vanderbilt et al., 2009).

Research exploring trauma in parents of infants admitted to the NICU is relatively new, as studies have primarily focused on mothers’ PTSD reactions to birth trauma (Andersen et al., 2012; Bailham & Joseph, 2003; Cook et al., 2018; Horesh et al., 2021; Yildiz et al., 2017). Further, researchers have only recently begun to recognize the importance of the father’s role in childbirth (Alio et al., 2013) and that they, too, may experience PTSD symptoms after a traumatic birth (Heyne et al., 2022). However, fathers’ traumatic childbirth experiences are strongly underrepresented in the literature compared to mothers’ (Ayers et al., 2006; Ghorbani et al., 2014). The research investigating the prevalence of parental PTSD in the NICU focuses mainly on the mother–infant dyad of preterm infants (Rizvydeen & Feltman, 2022). Despite this extensive work, very few studies have examined PTSD in parents of infants of all gestational ages admitted to the NICU (Lean et al., 2018), and there is still a significant gap in understanding trauma related to the father and the father–child dyad in research examining birth experiences and the NICU experience (Rizvydeen & Feltman, 2022; Salomè et al., 2022).

While it is clear that not all parents will have PTSD, two studies in the current literature that examined PTSD in parents in the NICU report variable prevalence rates ranging from 4.5 to 55% in mothers and 0 to 20% in fathers (Barr, 2012; Salomè et al., 2022). In contrast, the estimated lifetime prevalence rates of PTSD in the general population are much lower: 10–12% for women and 5–6% for men (Olff, 2017). These results suggest that mothers have an increased risk of PTSD compared to fathers and highlight that parents in the NICU may have a fourfold risk of developing PTSD compared to the general population (Malin et al., 2022; Ouyang et al., 2020; Roque et al., 2017). However, despite these results, many studies only examine childbirth trauma and do not distinguish between the two distinct traumas of ‘childbirth’ and the ‘NICU experience.’ Therefore, we do not know the true prevalence of PTSD in parents with NICU trauma, nor do we understand the full extent of the impact PTSD has on the parents, their infant, and their family.

Understanding the prevalence of PTSD and early detection of parents who have suffered NICU-related trauma (Forcada-Guex et al., 2011) may prove critical in identifying infants at risk of poor parent-infant attachment. Although the impact of PTSD related to the NICU experience on parents and their infant is scarce, it may be helpful to look at the consequences of childbirth-related trauma. For instance, a systematic review examining mothers with childbirth-related PTSD reports that mothers with PTSD were less likely to breastfeed their infants, and their infants had difficulty sleeping and eating (Cook et al., 2018). There is also evidence that childbirth-related PTSD has a severe and lasting impact on the mother’s relationships with their partner and child (Ayers et al., 2006). The same study also highlighted the significant effects of PTSD, as mothers reported feelings of anger, blame, depression, and suicidal thoughts and did not feel attached to their child until 1–5 years after birth (Ayers et al., 2006).

Clear and well-documented evidence supports the strong association between PTSD and adverse outcomes in early mother–infant attachment and child development (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2017). For example, one study found that mothers of preterm infants and PTSD followed a controlling parent–infant attachment pattern of interaction (Forcada-Guex et al., 2011) associated with feeding, hearing and language problems by 18 months of age (Forcada-Guex et al., 2006). Another study found significant associations between mothers’ PTSD related to traumatic childbirth and postpartum PTSD and poor social–emotional development at age two (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2017). These studies emphasize the potential for infants to suffer from poor maternal–infant attachment related to trauma after childbirth and, in this instance, the NICU experience.

Clinicians must understand the prevalence of PTSD in all parents of high-risk infants admitted to the NICU to provide parents with appropriate and timely psychosocial support—during the hospitalization and follow-up visits (Hynan et al., 2015). As a result, early detection and treatment may reduce the severity and symptoms of PTSD, improve parent–infant attachment and the infant’s long-term growth and development (Clottey & Dillard, 2013; Wilcoxon et al., 2021), and identify signs of possible child abuse (Hynan et al., 2015). This systematic review aims to review the literature on the prevalence of PTSD in mothers and fathers of high-risk infants admitted to the NICU, where the NICU experience was the index trauma. This review advances the theoretical understanding of PTSD in parents following NICU experiences. In addition, it informs clinical practice by providing insight into the extent of the problem and the need for strategies to identify and support parents.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

The diagnostic criteria for PTSD have been clearly outlined in mental health classification systems such as the DSM-5 and the International Classification of Diseases 11th edition (ICD-11) (World Health Organization, 2019a, b). However, among NICU research studies, references to PTSD use many different terms interchangeably, frequently without clear definitions, including ‘posttraumatic stress’ (PTS), ‘trauma,’ ‘PTSD diagnosis,’ ‘PTSD symptoms,’ ‘PTSD symptomatology,’ and ‘probable PTSD.’ In the context of this systematic review, the term ‘PTSD’ will refer to studies reflecting a diagnosis of probable PTSD according to the DSM, DSM-IV to DSM-5 and the ICD-11.

The diagnostic criteria of PTSD have been updated since first introduced in the third edition of the DSM-III (APA, 1980) as an anxiety disorder. Changes to the revised fourth edition of the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) included posttraumatic symptoms labeled as two separate anxiety disorders: ASD and PTSD. The most recent revision, the DSM-5, reclassified ASD and PTSD as trauma and stressor-related disorders. While the diagnostic symptomology of ASD and PTSD is similar and overlap (Shaw et al., 2009), the two diagnoses are distinguished according to the duration of symptoms. ASD includes early PTS symptoms lasting greater than 3 days and no more than 4 weeks immediately after the traumatic event. In contrast, persistent PTS symptoms lasting more than 1 month indicate PTSD (APA, 2013). Diagnosis of ASD and PTSD requires exposure to a traumatic event, as described above, and must also meet symptoms in the following categories: intrusion (e.g., flashbacks, intrusive upsetting memories, dreams), avoidance (e.g., efforts to avoid people, places, thoughts and feelings related to the trauma), negative cognitions and mood (e.g., negative beliefs about oneself, shame, anger, fear), and changes to arousal and reactivity (e.g., hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, sleep disturbance) (APA, 2013).

The index trauma of interest for this review is parents’ NICU experience. Since the definition of PTSD varies among researchers, studies must clarify the index trauma event (Criterion A) related to the symptoms in the diagnosis and assessment of PTSD (Priebe et al., 2018). While studies suggest that a diagnosis of ASD predicts PTSD in NICU parents (Lefkowitz et al., 2010), the literature has mainly focused on trauma symptoms in mothers (Shaw et al., 2013) in the NICU. This review focuses on the longer-term experiences of PTSD, examining studies that report the prevalence of PTSD diagnoses rather than the early symptoms (ASD) in NICU parents.

Parental PTSD in the NICU Experience

The distinction between childbirth and a NICU experience as an index event for PTSD is important. There are specific stressful, traumatic factors that are distinctly different in the context of PTSD related to the NICU experience compared to childbirth. For instance, the term ‘traumatic childbirth’ includes a single event specific to the birth of the infant (which may relate to the parent’s own health or the health of their infant), unlike postpartum birth-related events (Leinweber et al., 2022) or multiple traumatic events that may occur during the NICU experience. The repeated trauma of witnessing one’s own infant’s emergency events and the vicarious trauma from watching the emergency events of other parents’ infants (Fowler et al., 2019) increase the risk of parents developing PTSD. The NICU trauma may occur for weeks or months during hospital admission and continue long after discharge (Grunberg et al., 2019). The NICU experience may initiate an emotional roller coaster (Grunberg et al., 2019; Stacey et al., 2015) of mixed emotions of guilt (Barr, 2012), fear, frustration, and helplessness (Obeidat et al., 2009). The associated parental stress about their infant’s life and death, long-term disabilities and how this may impact their family’s future (Yee & Ross, 2006) can be overwhelming. Subsequently, parents may not be able to feel positive emotions of happiness or love (DSM-5; APA, 2013) toward their infant (Brand & Brennan, 2009). In addition, the smells (e.g., soaps) (Clottey & Dillard, 2013), sights (e.g., their infant stopping breathing, turning blue, or experiencing pain), and the sounds (e.g., noisy alarms) associated with the NICU may trigger PTSD reactions for parents (Grosik et al., 2013).

Family-Centered and Family Integrated Care (FIC) Models of care were developed to address the associated negative impacts of the NICU experience (Waddington et al., 2021). Broadly speaking, the principles of family-centered models of care involve parents as equal caregivers and decision-makers in the NICU to promote parent–infant attachment and have been shown to decrease parental stress (Skene et al., 2019; Soni & Tscherning, 2021). However, despite the introduction of family-centered care, there remain many challenges to supporting normal parent–infant attachment.

The parent–infant attachment relationship between the parent and the infant is important as it begins during pregnancy and continues throughout the first year of life (Benoit, 2004; Birmingham et al., 2017). Parents who respond positively to the infant’s cues and distress in typically developing infants lead to secure attachment and self-regulation (Benoit, 2004; Goulet et al., 1998). Unfortunately, in some instances, infants admitted to the NICU are separated from their parents for weeks and months. It is now understood that parents’ separation from their infant during the NICU experience and subsequent PTSD symptoms of avoidance and numbing can negatively impact parent–infant attachment and infant self-regulation (Birmingham et al., 2017; Garthus-Niegel et al., 2017). Further, the infant’s capacity for self-regulation may, in turn, influence their long-term health (cognitive and emotional) and developmental outcomes throughout childhood and adolescence (Brand & Brennan, 2009; Lean et al., 2018). Indeed, the presence of PTSD among NICU parents significantly impacts the quality of life (emotional, physical, and financial) and parental well-being (Galea et al., 2021). In addition, for some NICU parents, studies have shown that the challenges and trauma of having a sick infant admitted to the NICU increase the risk of marital problems (Goutaudier et al., 2011).

Emerging evidence from a meta-analysis of studies that examined the prevalence of PTSD in parents of infants admitted to the NICU reports variable prevalence rates. One meta-analysis identified 35 studies examining parental PTSD in the context of the NICU experience. This meta-analysis reported high prevalence rates of 27.6% among mothers and 16.1% in fathers from 1 month to 1 year postpartum (Malouf et al., 2022). However, in their meta-analysis, Malouf et al. (2022) did not specify the index trauma as the NICU experience. In another meta-analysis, Heyne et al. (2022) aimed to examine the prevalence and risk factors of birth-related PTSD among parents 1–14 months postpartum. While this meta-analysis included studies using the NICU experience as the risk factor, the index trauma was described as childbirth. As a result, their meta-analysis reported a lower prevalence rate of 4.7% in mothers and 1.2% in fathers (Heyne et al., 2022). These results suggest that NICU experiences, including traumatic childbirth, increase the risk of PTSD. However, in most cases, researchers do not specify the traumatic event when using self-reports to report PTSD (Sharp et al., 2021). In addition, previous studies have mainly focused on mothers’ PTSD symptoms at different time points and lack a clear description of the index trauma (Heyne et al., 2022). Therefore, these overall PTSD prevalence rates of the single trauma of childbirth may not compare to the potentially severe and often repetitive events parents (mothers, fathers, and other carers) experience in the context of the NICU.

Rationale

Despite the extensive knowledge in the field of maternal PTSD related to childbirth (McKenzie-McHarg et al., 2015), the prevalence of PTSD in parents of high-risk infants admitted to the NICU is not fully understood. Typically, researchers have not distinguished between the two distinct traumas of ‘childbirth’ and the ‘NICU experience,’ and few studies have clearly defined the index trauma (Criterion A of the DSM-IV to DSM-5). Therefore, to understand the true prevalence of PTSD in parents in the NICU, it is crucial to understand the index trauma of childbirth and the NICU experience as separate traumas; specifically, the NICU experience is unique and distinct from a single traumatic event of childbirth. Further, unlike childbirth trauma, the potential trauma of the NICU experience is not a single traumatic event (Barthel et al., 2020). Instead, the recurring, severe, and complex trauma of the NICU experience and the challenges of having a sick infant can persist for many months and years after discharge (Kersting et al., 2004). Unfortunately, most research examining parental trauma related to the NICU experience focuses on maternal PTSD associated with the birth of a preterm infant. In addition, few studies have examined PTSD in fathers and parents of all gestational ages of high-risk infants admitted to the NICU. This means the true prevalence of parental PTSD in the NICU is unknown. This systematic review aims to address the knowledge gap in identifying and understanding the prevalence of parents of all high-risk infants admitted to the NICU. This work will advance theoretical understanding, inform clinical practice, and help clinicians identify parents at risk of PTSD. In particular, early identification and referral for probable PTSD diagnosis in the hospital and follow-up visits in the NICU may reduce the risk of devastating long-term consequences for the parent and the infant’s long-term cognitive and emotional development (Clottey & Dillard, 2013).

Aim of the Review

This systematic review aimed to answer the research question:

-

(i)

What is the prevalence of PTSD in mothers and fathers of high-risk infants admitted to the NICU where the NICU experience is the index trauma?

Method

Protocol and Registration

The study protocol was registered with Prospero (a prospective international register of systematic reviews)—registration number CRD42020154548 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/). Amendments to the protocol were submitted in 2020 and 2021. This review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA (2020) Statement (Page et al., 2021; Table S1).

Search Strategy

The initial literature search was conducted on 15 January 2020 using PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global electronic databases (1980–2021). The following search terms were used with the assistance of the librarian (LE) from the University of Queensland: (‘posttraumatic stress disorder’/exp OR ‘ptsd’/exp) AND (‘Intensive Care’/exp OR ‘neonatal intensive care’/exp OR ‘Intensive Care Units’/exp OR ‘nicu’/exp) AND (‘infant’/exp OR ‘infant’/exp OR infant OR ‘newborn’/exp OR ‘neonate’/exp OR ‘prematurity’/exp OR ‘low birth weight’/exp OR ‘Hospitalised infant’/exp). The search was limited to articles published in English. An update of the database search using the full search methods from inception was conducted on 6 January 2021 and 26 November 2021 (Bramer et al., 2018). Refer to the full list of the search terms provided in “Appendix 1.”

Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review considered studies for inclusion if they specified the traumatic event as the ‘NICU experience’ one month after childbirth and the NICU admission. Inclusion criteria included (1) one parent (of any age and ethnicity) of infants admitted to NICU, (2) both parents (of any age and ethnicity) of infants admitted to NICU, (3) quantitative or mixed designs, (4) any duration of follow-up, (5) all validated DSM-III to DSM-5 and ICD-9 to ICD-11 criteria measures of screening for PTSD by a self-report and clinician, (6) NICU experience as the index trauma, (7) measures of screening for PTSD by a self-report or a structured clinical interview where a diagnosis of PTSD is likely, (8) published, full text, English studies, and (9) prospective and retrospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, longitudinal and intervention studies.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria included (1) measures that do not have a clinical cutoff score, (2) childbirth as the index trauma (this review will examine the trauma related specifically to the NICU experience), (3) studies describing trauma resulting from warfare, terrorism, natural disaster or medical illness, (4) narrative review articles, (5) books, (6) book chapters, (7) conference abstracts, (8) commentaries or letters to the editor and dissertations, and (9) publication date prior to 1980 (as PTSD was not formally recognized by the DSM until 1980). Studies were also excluded where the prevalence was not calculated as a percentage.

Studies where it was impossible to determine which medical event was being responded to (e.g., the NICU experience versus the childbirth experience) were excluded. Including only studies with the NICU experience as the traumatic event was to avoid the confounding variable of the birth experience. For instance, studies measuring traumatic symptoms, including questions related to the birth experience, such as the Perinatal Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire (PPQ; DeMier et al., 1996), were excluded.

Study Selection

The process for the study selection included several stages. First, search results were imported into the Endnote software with duplicates removed. Second, studies were exported to the Covidence software (screening and data extraction tool) for screening, with any identified duplicates removed. Third, two reviewers (LM, HK) independently screened titles and abstracts using Covidence (and any disputes were discussed until consensus was reached). Fourth, two reviewers (LM, HK) screened full-text articles according to the study protocol eligibility criteria, with a third reviewer used to resolve any disagreements (VC, LC). Where multiple articles were identified using the same data, the articles were selected based on those with the most information or meeting the eligibility criteria. Fifth, information was sought from some study authors by email where the eligibility was unclear. One study author responded and confirmed that the trauma measurement did not include a clinical cutoff score, and the article was subsequently excluded for not meeting eligibility. Articles were excluded if the authors did not confirm eligibility in response to the email. Finally, one reviewer (LM) conducted hand searches of the reference lists to identify additional studies (note: this process was completed again with two updated searches added).

Data Extraction

One reviewer (LM) independently extracted data from Covidence using an Excel spreadsheet, and a second reviewer (KF) assessed the accuracy of the data with input from an additional two reviewers (VC and HK). The data that were extracted included (1) author/year, (2) study design, (3) country, (4) sample characteristics including the number of participants, mean age of parents, mean gestation age and mean infants’ weight, (5) diagnostic classification system and version used (e.g., DSM-IV), (6) outcome measure; including instrument for traumatic stress and clinical cutoff score, (7) PTSD Event description of trauma [e.g., hospital (NICU) and birth and hospital (NICU) experience], (8) time point (i.e., time of assessment), (9) prevalence of probable PTSD, and (10) findings.

Data Synthesis

The characteristics were tabulated and, where possible, the prevalence was categorized into the following groups: (1) one parent (mother), (2) one parent (father), (3) couples and (4) parents (mothers and fathers), (5) sample size, and (6) type of measure (diagnostic interview and self-reports). The PTSD-specified trauma event was assessed and tabulated into subgroups of the definition of the index trauma and outcome measures. PTSD prevalence rates among studies reporting the NICU experience as the index trauma were manually calculated using the last time point (e.g., the last time of assessment at 30 days or greater) after the NICU admission. Studies where the index trauma was not verified by the author or specified as the NICU experience were not included in the overall prevalence and narrative synthesis. Lastly, due to the high heterogeneity (e.g., variability in the infants’ gestational ages, time of trauma assessment, and outcome measures) and significant variations of the study methodology of the included studies, the overall findings were presented in a narrative format.

Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (LM, LC) independently assessed the quality of each included study using the risk of bias tool developed by Hoy et al. (2012). This risk of bias tool was designed for systematic reviews of prevalence studies and includes four domains plus a summary risk of bias assessment. The template consists of a 10-item assessment: items 1–4 assess external validity, items 5–9 assess internal validity, and item 10 assesses analysis bias (Hoy et al., 2012). Studies were assigned a rating of their risk of bias with scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 deemed low, moderate, and high risk, respectively. Any discrepancies between reviewers were discussed until a consensus was reached. Studies were not excluded based on any of the above factors.

Results

Study Selection

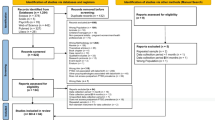

In total, 707 records were imported for screening using the Covidence screening tool for conducting systematic reviews. Following the removal of duplicates, 252 records were screened for the title and abstract review, with 156 records excluded. The remaining 96 full-text records identified nine records through hand searches of the reference list. These were screened against the inclusion criteria, and 89 records were excluded. Seven articles met the inclusion criteria in reporting PTSD prevalence. Across studies, the most common reasons for exclusion were studies that included PTSD related to childbirth and those in which the index traumatic events were not reported. Refer to the PRISMA Diagram as shown in Fig. 1.

Study Characteristics

Studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 5), Australia (n = 1) and the United Kingdom (n = 1). All studies were published between 2009 and 2020. Study designs were primarily prospective and longitudinal, and no studies included a control group. There were 526 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 18 to 134 participants. Five studies recruited mothers and fathers; two studies focused on mothers’ PTSD only. The mean age of mothers ranged between 29 and 34 years and fathers from 31 to 37 years. Mean gestational age ranged from less than 28 weeks to term. The infants’ mean birth weight ranged from 1500 to 3500 g, with four studies not reporting weight and one including the range only. All studies included parents across the subcategories of preterm birth, including extremely preterm (< 28 weeks), very preterm (< 32 weeks), and moderate to late preterm (32 weeks to 37 weeks) (World Health Organisation, WHO, 2022). One study analyzed parents of infants across all gestational age categories, including full-term infants. All studies included parents of high-risk infants admitted to the highest levels of neonatal care (levels 3 to 4). Refer to the summary of characteristics of the included studies as shown in “Appendix 2”.

Among studies, PTSD assessment was based on self-report measures using the DSM-IV criteria, with no studies using the DSM-5, ICD-9, ICD-11 or structured clinical interviews. Within the reviewed studies, five different self-report measures were used to measure probable PTSD. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-IV (PCL) is the most commonly used self-report, such as the PCL (n = 2), PCL-S (n = 1), and PCL-C (n = 1). The PCL developed by the US National Center for PTSD is used to screen for PTSD and make a provisional PTSD diagnosis (Weathers et al., 2013). The DSM-IV PCL includes 17 items and has three different versions: C(ivilian), M(ilitary), and S(pecific) (Bliese et al., 2008). The other measures used to examine PTSD included the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) (n = 1) and the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) (n = 2). However, even when the same measure was used between studies, there were differences in the cutoff scores. For example, the IES-R cutoff scores were (33 and ≥ 33), the DTS (38 to ≥ 40), and the PCL (38 and ≥ 1 re-experiencing symptoms, ≥ 3 avoidance symptoms, and ≥ 2 arousal symptoms).

Regarding trauma, this review identified six terms to describe the index trauma: (1) the NICU experience (Barr, 2012; Schecter et al., 2020), (2) the experience of having a premature baby hospitalised in the neonatal ward (Galpin, 2013), (3) their infant’s admission to the NICU (Lefkowitz et al., 2010), (4) during the NICU hospitalization (Lotterman et al., 2019), (5) their reactions to having an infant hospitalised in the NICU (Shaw et al., 2009), and (6) during or after having an infant in the NICU (Shaw et al., 2013).

Prevalence

Overall, the prevalence rates of PTSD in parents following their high-risk infant’s admission to the NICU varied from 0 to 33%. One study, including mothers (n = 11) and fathers (n = 7), reported a higher PTSD prevalence in fathers (33%) compared to mothers (9%) (Shaw et al., 2009). The highest PTSD prevalence in a sample of mothers only (n = 50) was 30% (Shaw et al., 2013), with another study reporting on mothers only demonstrating a PTSD rate of 15.8% (n = 76) (Lotterman et al., 2019). The lowest prevalence rates were demonstrated in a study of couples (n = 67), with a PTSD prevalence rate of 0% in fathers and 4.5% in mothers (Barr, 2012).

PTSD prevalence rates also differed according to the infant’s mean gestational age. For example, two studies demonstrated higher prevalence rates of 33% and 30% among parents of infants with a mean gestational age of 30.89 and 31.9 weeks, respectively (Shaw et al., 2009, 2013). In contrast, two studies reported no significant difference in PTSD rates between parents of infants of < 28 weeks gestation and full-term infants (24% and 29%, respectively) (Schecter et al., 2020).

This review identified several risk factors for a diagnosis of probable PTSD. For instance, four studies identified a prior history of ASD as a strong predictor of PTSD (Barr, 2012; Lefkowitz et al., 2010; Shaw et al., 2009, 2013). Other studies demonstrated that symptoms significantly correlated with PTSD included chronic guilt, guilt-proneness, fear of death (Barr, 2012), depression and anxiety (Lefkowitz et al., 2010).

Screening for parents’ symptoms of PTSD related to the NICU experience was administered by self-report measures at a one-time point only. The shortest screening time was 30 days after the NICU admission (Lefkowitz et al., 2010), and the longest assessment time for PTSD symptoms was 12–13 months (Barr, 2012; Schecter et al., 2020). One study screened parents for PTSD 1 month after discharge (Shaw et al., 2013) and another at 1 to 2 months after discharge (Galpin, 2013). Other studies conducted screening ranging from 4 to 6 months postpartum (Lotterman et al., 2019; Shaw et al., 2009).

Overall Quality

Of the seven included studies, six were rated as having a moderate risk of bias and one having a low risk of bias. However, all seven studies were rated as having a high risk of bias in items representing the target population. For example, population bias included studies recruiting only mothers (n = 2), indicating significant bias within samples. In addition, most of the studies did not adequately report the response rate (n = 6). Refer to the risk of bias summary as shown in Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary. Tool developed by Hoy et al. (2012)

Discussion

This systematic review is the first we are aware of to synthesise the existing literature on the prevalence of PTSD among mothers and fathers specifically related to the ‘NICU experience’ as the index trauma. Overall, across studies included, widely variable PTSD prevalence rates were reported (0% to 33%). Consistent with other studies, our review confirms that mothers were more likely to develop PTSD in relation to the NICU experience than fathers (Malouf et al., 2022). Previous reviews have focused on PTSD prevalence in mothers but not fathers of preterm infants admitted to the NICU (Beck & Woynar, 2017; Gondwe & Holditch-Davis, 2015). Given that one of the included studies in our review showed that fathers were four times more likely to experience PTSD than mothers (Shaw et al., 2009), this is an important area for further study. However, the results of this review do not allow us to draw firm conclusions about the prevalence rates of NICU-related PTSD in mothers compared to fathers. This review identifies the specific gaps in understanding the prevalence of PTSD related to the potential impact of the repeated and complex trauma parents may experience in the NICU. It may be useful for future studies to examine trauma associated with caregivers, grandparents, or other infants admitted to the NICU.

The results of this review indicate that no studies report probable PTSD based on the DSM-5 and four criteria of symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and arousal). These results suggest that most research in the NICU has relied on self-reports of the DSM-IV criteria rather than the DSM-5 criteria and excludes symptoms of negative cognitions and moods. This is critical in determining actual PTSD prevalence as the exact impact and prevalence of PTSD using the new diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5 criteria is unknown (McKenzie-McHarg et al., 2015).

One of the key findings from this review is that the prevalence of parental PTSD in the NICU is difficult to interpret. For example, the use of different measures and cutoffs with the same measures across studies may overestimate rates of PTSD (Hynan et al., 2013; Wilcoxon et al., 2021; Yildiz et al., 2017). However, Wilcoxon et al. (2021) argue that self-report measures could be more likely to identify parental PTSD than a clinician-administered interview. While it is unclear how best to understand parental PTSD in the NICU, the literature confirms that there is no definition of what constitutes a self-reported diagnosis of probable PTSD.

While the self-report does not replace a clinically administered interview, it is a pragmatic risk assessment tool (Bernardo et al., 2021) and can be of practical value in the NICU to identify parents who may be suffering from PTSD (Grunberg et al., 2019). It would be helpful to clarify the relationship between self-report and clinical interview determined PTSD in this cohort of parents. Agreed and consistent self-report tools would improve the consistency of future studies, which would help us better understand this important topic.

The variability in study design, types of measures and their clinical cutoff scores, sample size, population (e.g., differences in the infants’ gestational ages) and timing of screening contribute to the significant variations in the prevalence of PTSD. In addition, similar to the results of this review, a recent meta-analysis in which the index trauma was childbirth rather than the NICU experience also found a high degree of heterogeneity between studies (Malouf et al., 2022).

Further studies are needed to understand the impact and true prevalence of parental PTSD in the context of the NICU experience. For example, research must include longitudinal studies with universal screening, multiple time points and consistent definitions, measures, and cutoff scores (Roque et al., 2017). In addition, given the variability in the types of measures and cutoff scores used to report probable PTSD, studies can be improved by using validated and agreed DSM-5 measures, including all parents, with an emphasis on fathers and parents of infants of all gestational age categories, including full-term infants (Moreyra et al., 2021).

Although there has been much interest in the psychological impact on parents in the NICU, this review highlights the lack of consensus on what describes the exact definition of the index trauma (Criterion A of the DSM-IV to DSM-5) as the ‘NICU experience.’ More work needs to be done to understand the differences between the trauma of the NICU experience and childbirth in parents. The trauma of the NICU experience is a distinct and separate event from childbirth and can result in recurring, severe and complex factors that continue for years after discharge. Future studies must clearly define the index trauma and understand if the measures used to assess PTSD are accurate. Therefore, we propose that the definition of the ‘NICU experience trauma’ is the parent’s response following the admission of a high-risk infant admitted to the NICU.

This review’s results have several important clinical implications for future practice. For example, universal screening of all parents in the NICU is a well-recognized issue (Hynan & Hall, 2015; Moreyra et al., 2021). However, despite the recommendations from a National Perinatal Association Working Group (Hall & Hynan, 2015) for universal standardised screening for all parents in the NICU, standardised screening is not common practice (Bloyd et al., 2022; Moreyra et al., 2021). For example, a study in the United States examined parents’ mental health screening practices in the NICU. They found that only 3% of NICUs routinely screen parents of high-risk infants for symptoms of PTSD, with only 22% of NICUs providing psychosocial support (Bloyd et al., 2022). Given that some studies have found that up to a third of parents are at risk of serious psychiatric sequelae from their infant’s NICU admission, the benefits and risks of standardised screening protocols need to be better understood.

There are significant risks in not understanding the prevalence of PTSD in parents. For example, unrecognized and untreated PTSD is negatively associated with parent–infant attachment and may impact the infant’s growth and development (Wilcoxon et al., 2021). Given the high prevalence of parental PTSD, clinicians need to understand which parents might benefit from a comprehensive clinical interview for an accurate diagnosis, how referral processes are embedded into NICU workflows, and how best to intervene to ensure quality outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

This review’s strength is examining PTSD prevalence in studies that clearly describe the index trauma (Criterion A of the DSM-IV to DSM-5) as the ‘NICU experience.’ Our study highlights the importance of clearly distinguishing the extent to which traumatic medical events (the NICU experience versus childbirth) influence or compound the risk of PTSD. We also highlight that mothers and fathers are not equally represented in studies to date. While most of the literature focuses on mothers’ experiences, it may be helpful for further research to include the impact of the parent–infant dyad or caregiver-dyad (grandparent or other). Further, this review did not include a review of the measures available and is something for further study.

Several limitations must be considered. The NICU experience is a unique and complex event with specific traumas that also need to be considered. For example, the NICU experience is often associated with additional traumas relating to childbirth or maternal medical illness. Priebe et al. (2018) argue that multiple-index traumas influence PTSD severity scores. Most of the literature includes self-reports, and none of the studies identified a clinical diagnosis of PTSD. In addition, given the high heterogeneity in the studies examined, a meta-analysis was not possible. Finally, this review only included articles published in English and conducted in high-income countries. Thus, the results may not apply to culturally and linguistically diverse populations.

Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to understand the prevalence rates of PTSD among mothers and fathers of high-risk infants admitted to the NICU, explicitly focusing on the ‘NICU experience’ as the index trauma. The results highlight the importance of better understanding the prevalence to determine an appropriate response for parents. NICU-related PTSD in parents needs to be clearly defined, more consistently measured and better understood, particularly in fathers.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

References

Aftyka, A., Rybojad, B., Rozalska-Walaszek, I., Rzoñca, P., & Humeniuk, E. (2014). Post-traumatic stress disorder in parents of children hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU): Medical and demographic risk factors. Psychiatria Danubina, 26(4), 347–352. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84909647121&partnerID=40&md5=9cd5bb49e85a6ab997c5590d0f60f048

Alio, A. P., Lewis, C. A., Scarborough, K., Harris, K., & Fiscella, K. (2013). A community perspective on the role of fathers during pregnancy: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-60

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Andersen, L. B., Melvaer, L. B., Videbech, P., Lamont, R. F., & Joergensen, J. S. (2012). Risk factors for developing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: A systematic review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(11), 1261–1272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01476.x

Ayers, S., Eagle, A., & Waring, H. (2006). The effects of childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder on women and their relationships: A qualitative study. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 11(4), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600708409

Bailham, D., & Joseph, S. (2003). Post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A review of the emerging literature and directions for research and practice. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 8(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354850031000087537

Barr, P. (2010). Acute traumatic stress in neonatal intensive care unit parents: Relation to existential emotion-based personality predispositions. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15(2), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903373128

Barr, P. (2012). A dyadic analysis of negative emotion personality predisposition effects with psychological distress in neonatal intensive care unit parents. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(4), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024228

Barthel, D., Göbel, A., Barkmann, C., Helle, N., & Bindt, C. (2020). Does birth-related trauma last? Prevalence and risk factors for posttraumatic stress in mothers and fathers of VLBW preterm and term born children 5 years after birth. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.575429

Beck, C. T. (2004). Post-traumatic stress disorder due to childbirth: The aftermath. Nursing Research, 53(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200407000-00004

Beck, C. T., & Woynar, J. (2017). Posttraumatic stress in mothers while their preterm infants are in the newborn intensive care unit: A mixed research synthesis. Advances in Nursing Science, 40(4), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/ans.0000000000000176

Benoit, D. (2004). Infant–parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome. Paediatric Child Health, 9(8), 541–545. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/9.8.541

Bernardo, J., Rent, S., Arias-Shah, A., Hoge, M. K., & Shaw, R. J. (2021). Parental stress and mental health symptoms in the NICU: Recognition and interventions. NeoReviews, 22(8), e496–e505. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.22-8-e496

Birmingham, R. S., Bub, K. L., & Vaughn, B. E. (2017). Parenting in infancy and self-regulation in preschool: An investigation of the role of attachment history. Attachment and Human Development, 19(2), 107–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2016.1259335

Bliese, P. D., Wright, K. M., Adler, A. B., Cabrera, O., Castro, C. A., & Hoge, C. W. (2008). Validating the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen and the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist with soldiers returning from combat. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.76.2.272

Bloyd, C., Murthy, S., Song, C., Franck, L. S., & Mangurian, C. (2022). National cross-sectional study of mental health screening practices for primary caregivers of NICU infants. Children, 9(6), 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060793

Bramer, W. M., Rethlefsen, M. L., Mast, F., & Kleijnen, J. (2018). Evaluation of a new method for librarian-mediated literature searches for systematic reviews. Research Synthesis Methods, 9(4), 510–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1279

Brand, S. R., & Brennan, P. A. (2009). Impact of antenatal and postpartum maternal mental illness: How are the children? Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 52(3), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b52930

Chang, H. P., Chen, J. Y., Huang, Y. H., Yeh, C. J., Huang, J. Y., Su, P. H., & Chen, V. C. (2016). Factors associated with post-traumatic symptoms in mothers of preterm infants. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(1), 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.08.019

Christie, H., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Alves-Costa, F., Tomlinson, M., & Halligan, S. L. (2019). The impact of parental posttraumatic stress disorder on parenting: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1550345. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1550345

Clottey, M., & Dillard, D. M. (2013). Post-traumatic stress disorder and neonatal intensive care. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 28(3), 23–29. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-neonatal-intensive/docview/1412227235/se-2?accountid=14723

Cook, N., Ayers, S., & Horsch, A. (2018). Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.045

DeMier, R. L., Hynan, M. T., Harris, H. B., & Manniello, R. L. (1996). Perinatal stressors as predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress in mothers of infants at high risk. Journal of Perinatology, 16(4), 276–280. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8866297/

Feeley, N., Genest, C., Niela-Vilén, H., Charbonneau, L., & Axelin, A. (2016). Parents and nurses balancing parent–infant closeness and separation: A qualitative study of NICU nurses’ perceptions. BMC Pediatrics, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0663-1

Forcada-Guex, M., Borghini, A., Pierrehumbert, B., Ansermet, F., & Muller-Nix, C. (2011). Prematurity, maternal posttraumatic stress and consequences on the mother–infant relationship. Early Human Development, 87(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.09.006

Forcada-Guex, M., Pierrehumbert, B., Borghini, A., Moessinger, A., & Muller-Nix, C. (2006). Early dyadic patterns of mother–infant interactions and outcomes of prematurity at 18 months. Pediatrics, 118(1), e107-114. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1145

Fowler, C., Green, J., Elliott, D., Petty, J., & Whiting, L. (2019). The forgotten mothers of extremely preterm babies: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(11–12), 2124–2134. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14820

Galea, M., Park, T., & Hegadoren, K. M. (2021). Improving mental health outcomes of parents of infants treated in neonatal intensive care units: A scoping review. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2017.02.005

Galpin, J. (2013). Posttraumatic stress and growth symptoms in parents of premature infants: The role of rumination type and social support (10058369). https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/49596/

Garthus-Niegel, S., Ayers, S., Martini, J., von Soest, T., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2017). The impact of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms on child development: A population-based, 2-year follow-up study. Psychological Medicine, 47(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329171600235x

Ghorbani, M., Dolatian, M., Shams, J., & Alavi-Majd, H. (2014). Anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and social supports among parents of premature and full-term infants. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 16(3), e13461. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.13461

Gondwe, K. W., & Holditch-Davis, D. (2015). Posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of preterm infants. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 3, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2015.05.002

Goulet, C., Bell, L., St-Cyr, D., Paul, D., & Lang, A. (1998). A concept analysis of parent–infant attachment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(5), 1071–1081. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00815.x

Goutaudier, N., Lopez, A., Séjourné, N., Denis, A., & Chabrol, H. (2011). Premature birth: Subjective and psychological experiences in the first weeks following childbirth, a mixed-methods study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29(4), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2011.623227

Grosik, C., Snyder, D., Cleary, G. M., Breckenridge, D. M., & Tidwell, B. (2013). Identification of internal and external stressors in parents of newborns in intensive care. The Permanente Journal, 17(3), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-105

Grunberg, V. A., Geller, P. A., Bonacquisti, A., & Patterson, C. A. (2019). NICU infant health severity and family outcomes: A systematic review of assessments and findings in psychosocial research. Journal of Perinatology, 39(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-018-0282-9

Hall, S. L., & Hynan, M. T. (2015). Interdisciplinary recommendations for the psychosocial support of NICU parents. Nature Publishing Group, NPG. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.147

Heyne, C.-S., Kazmierczak, M., Souday, R., Horesh, D., Lambregtse-van den Berg, M., Weigl, T., Horsch, A., Oosterman, M., Dikmen-Yildiz, P., & Garthus-Niegel, S. (2022). Prevalence and risk factors of birth-related posttraumatic stress among parents: A comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 94, 102157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102157

Hodek, J.-M., von der Schulenburg, J. M., & Mittendorf, T. (2011). Measuring economic consequences of preterm birth—Methodological recommendations for the evaluation of personal burden on children and their caregivers. Health Economics Review, 1(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-1991-1-6

Horesh, D., Garthus-Niegel, S., & Horsch, A. (2021). Childbirth-related PTSD: Is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 39(3), 221–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

Hoy, D., Brooks, P., Woolf, A., Blyth, F., March, L., Bain, C., Baker, P., Smith, E., & Buchbinder, R. (2012). Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: Modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(9), 934–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014

Hynan, M. T., & Hall, S. L. (2015). Psychosocial program standards for NICU parents. Journal of Perinatology, 35(1), S1–S4. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.141

Hynan, M. T., Mounts, K. O., & Vanderbilt, D. L. (2013). Screening parents of high-risk infants for emotional distress: Rationale and recommendations. Journal of Perinatology, 33(10), 748–753. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2013.72

Hynan, M. T., Steinberg, Z., Baker, L., Cicco, R., Geller, P. A., Lassen, S., Milford, C., Mounts, K. O., Patterson, C., Saxton, S., Segre, L., & Stuebe, A. (2015). Recommendations for mental health professionals in the NICU. Journal of Perinatology, 35(1), S14–S18. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.144

Kersting, A., Dorsch, M., Wesselmann, U., Lüdorff, K., Witthaut, J., Ohrmann, P., Hörnig-Franz, I., Klockenbusch, W., Harms, E., & Arolt, V. (2004). Maternal posttraumatic stress response after the birth of a very low-birth-weight infant. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(5), 473–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.011

Kim, W., Lee, E., Kim, K., Namkoong, K., Park, E., & Rha, D. (2015). Progress of PTSD symptoms following birth: A prospective study in mothers of high-risk infants. Journal of Perinatology, 35(8), 575–579. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.9

Lean, R. E., Rogers, C. E., Paul, R. A., & Gerstein, E. D. (2018). NICU hospitalization: Long-term implications on parenting and child behaviors. Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics, 4(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-018-0112-5

Lefkowitz, D. S., Baxt, C., & Evans, J. R. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17(3), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-010-9202-7

Leinweber, J., Fontein-Kuipers, Y., Thomson, G., Karlsdottir, S. I., Nilsson, C., Ekström-Bergström, A., Olza, I., Hadjigeorgiou, E., & Stramrood, C. (2022). Developing a woman-centered, inclusive definition of traumatic childbirth experiences: A discussion paper. Birth. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12634

Lotterman, J. H., Lorenz, J. M., & Bonanno, G. A. (2019). You can’t take your baby home yet: A longitudinal study of psychological symptoms in mothers of infants hospitalized in the NICU. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-018-9570-y

Malin, K. J., Johnson, T. S., Brown, R. L., Leuthner, J., Malnory, M., White-Traut, R., Rholl, E., & Lagatta, J. (2022). Uncertainty and perinatal post-traumatic stress disorder in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Research in Nursing and Health. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.22261

Malouf, R., Harrison, S., Burton, H. A. L., Gale, C., Stein, A., Franck, L. S., & Alderdice, F. (2022). Prevalence of anxiety and post-traumatic stress (PTS) among the parents of babies admitted to neonatal units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 43, 101233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101233

McKenzie-McHarg, K., Ayers, S., Ford, E., Horsch, A., Jomeen, J., Sawyer, A., Stramrood, C., Thomson, G., & Slade, P. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: An update of current issues and recommendations for future research. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 33(3), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2015.1031646

Moreyra, A., Dowtin, L. L., Ocampo, M., Perez, E., Borkovi, T. C., Wharton, E., Simon, S., Armer, E. G., & Shaw, R. J. (2021). Implementing a standardized screening protocol for parental depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Early Human Development, 154, 105279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105279

Obeidat, H. M., Bond, E. A., & Callister, L. C. (2009). The parental experience of having an infant in the newborn intensive care unit. Journal of Perinatal Education, 18(3), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1624/105812409x461199

Olff, M. (2017). Sex and gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder: an update. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup4), 1351204. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1351204

Ouyang, J. X., Mayer, J. L. W., Battle, C. L., Chambers, J. E., & Inanc Salih, Z. N. (2020). Historical perspectives: Unsilencing suffering: Promoting maternal mental health in neonatal intensive care units. NeoReviews, 21(11), e708–e715. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.21-11-e708

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Priebe, K., Kleindienst, N., Schropp, A., Dyer, A., Krüger-Gottschalk, A., Schmahl, C., Steil, R., & Bohus, M. (2018). Defining the index trauma in post-traumatic stress disorder patients with multiple trauma exposure: Impact on severity scores and treatment effects of using worst single incident versus multiple traumatic events. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1486124

Rizvydeen, S., & Feltman, D. M. (2022). What happened to dad? The complexity of paternal trauma and ethical care. The American Journal of Bioethics, 22(5), 74–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2022.2055213

Roque, A. T. F., Lasiuk, G. C., Radünz, V., & Hegadoren, K. (2017). Scoping review of the mental health of parents of infants in the NICU. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Neonatal Nursing, 46(4), 576–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2017.02.005

Salomè, S., Mansi, G., Lambiase, C. V., Barone, M., Piro, V., Pesce, M., Sarnelli, G., Raimondi, F., & Capasso, L. (2022). Impact of psychological distress and psychophysical wellbeing on posttraumatic symptoms in parents of preterm infants after NICU discharge. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 48(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01202-z

Sanders, M., & Hall, S. (2018). Trauma-informed care in the newborn intensive care unit: Promoting safety, security and connectedness. Journal of Perinatology, 38(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2017.124

Schecter, R., Pham, T., Hua, A., Spinazzola, R., Sonnenklar, J., Li, D., Papaioannou, H., & Milanaik, R. (2020). Prevalence and longevity of PTSD symptoms among parents of NICU infants analyzed across gestational age categories. Clinical Pediatrics, 59(2), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819892046

Sharp, M., Huber, N., Ward, L. G., & Dolbier, C. (2021). NICU-specific stress following traumatic childbirth and its relationship with posttraumatic stress. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 35(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/jpn.0000000000000543

Shaw, R. J., Bernard, R. S., De Blois, T., Ikuta, L. M., Ginzburg, K., & Koopman, C. (2009). The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unit. Psychosomatics, 50(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.2.131

Shaw, R. J., Bernard, R. S., Storfer-Isser, A., Rhine, W., & Horwitz, S. M. (2013). Parental coping in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 20(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-012-9328-x

Shaw, R. J., Deblois, T., Ikuta, L., Ginzburg, K., Fleisher, B., & Koopman, C. (2006). Acute stress disorder among parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care nursery. Psychosomatics, 47(3), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.47.3.206

Skene, C., Gerrish, K., Price, F., Pilling, E., Bayliss, P., & Gillespie, S. (2019). Developing family-centred care in a neonatal intensive care unit: An action research study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 50, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2018.05.006

Soni, R., & Tscherning, C. (2021). Family-centred and developmental care on the neonatal unit. Paediatrics and Child Health, 31(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2020.10.003

Stacey, S., Osborn, M., & Salkovskis, P. (2015). Life is a rollercoaster…What helps parents cope with the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)? Journal of Neonatal Nursing, 21(4), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2015.04.006

Vanderbilt, D., Bushley, T., Young, R., & Frank, D. A. (2009). Acute posttraumatic stress symptoms among urban mothers with newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit: A preliminary study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e318196b0de

Waddington, C., Van Veenendaal, N. R., O’Brien, K., Patel, N., & International Steering Committee for Family Integrated Care. (2021). Family integrated care: Supporting parents as primary caregivers in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatric Investigation, 5(2), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/ped4.12277

Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

Wilcoxon, L. A., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Burgess, A. (2021). Post-traumatic stress disorder in parents following their child’s single-event trauma: A meta-analysis of prevalence rates and risk factor correlates. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(4), 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-021-00367-z

World Health Organization. (2019a). ICD-11: International classification of diseases. WHO. https://icd.who.int/

World Health Organization. (2019b). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). WHO. https://icd.who.int/

World Health Organisation. (2022). Preterm birth. WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth

Yee, W., & Ross, S. (2006). Communicating with parents of high-risk infants in neonatal intensive care. Paediatrics and Child Health, 11(5), 291–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009

Yildiz, P. D., Ayers, S., & Phillips, L. (2017). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009

Funding

This review was supported by a University of Queensland Research Scholarship, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Foundation Grant and Postgraduate Scholarship and contributes to a Doctor of Philosophy Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We would like to thank academic librarian Mr. Lars Eriksson from the University of Queensland for developing this review's search strategy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Search Terms

(Information Sources PsycINFO, 1980 to November to 26 November 2021) | ||

|---|---|---|

Search number | Query | Results |

4 | ((("Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic"[Mesh] OR "PTSD"[tiab] OR "post-traumatic stress disorders"[tiab] OR "post-traumatic stress disorder"[tiab] OR "posttraumatic stress disorders"[tiab] OR "posttraumatic stress disorder"[tiab] OR PTSS[tiab] OR "post-traumatic stress symptomatology"[tiab])) AND ((('Intensive Care'[tiab] OR 'neonatal intensive care’[tiab] OR 'Intensive Care Units[tiab] OR 'nicu'[tiab])) AND (('Intensive Care'[tiab] OR 'neonatal intensive care’[tiab] OR 'Intensive Care Units[tiab]OR 'nicu'[tiab])))) AND (('infant'[tiab] OR ‘newborn’[tiab] OR ‘neonate’[tiab] OR ‘prematurity’[tiab] OR ‘low birth weight’[tiab] OR ‘Hospitalised infant’[tiab])) | 67 |

3 | ('infant'[tiab] OR ‘newborn’[tiab] OR ‘neonate’[tiab]OR ‘prematurity’[tiab] OR ‘low birth weight’[tiab] OR ‘Hospitalised infant’[tiab]) | 406,709 |

2 | (('Intensive Care'[tiab] OR 'neonatal intensive care’[tiab] OR 'Intensive Care Units[tiab]OR 'nicu'[tiab])) AND (('Intensive Care'[tiab] OR 'neonatal intensive care’[tiab] OR 'Intensive Care Units[tiab]OR 'nicu'[tiab])) | 171,848 |

1 | ("Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic"[Mesh] OR "PTSD"[tiab] OR "post-traumatic stress disorders"[tiab] OR "post-traumatic stress disorder"[tiab] OR "posttraumatic stress disorders"[tiab] OR "posttraumatic stress disorder"[tiab] OR PTSS[tiab] OR "post-traumatic stress symptomatology"[tiab]) | 51,250 |

Appendix 2: Summary of Characteristics of Studies

First Author/Year/Country/Design | Sample (n) size | Parents age (mean) | Gestational age weeks (mean) | Infant’s weight g (mean) | Outcome measures | Clinical cut-off | PTSD event specified | Timepoints (postpartum) | Prevalence of probable PTSD (n, %) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Barr, 2012, Australia; Prospective cohort study | Couples (n = 67) | Fathers 33.5 Mothers 31.0 | > 34 | NR | PCL-S DSM-IV (Self-report) | ≥ 44 | NICU Experience re-experiencing (“Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of your NICU experience?”); avoidance (“Avoid thinking about or talking about your NICU experience or avoid having feelings related to it?”); and hyperarousal (“Being ‘super alert’ or watchful on guard?”) | 13 months | Nil (0) Fathers 6 (4.5%) Mothers | 4.5% of mothers and no fathers met clinical cut-off for PTSD. Mothers who met the clinical cut-off for PTSD had a previous history of ASD. There was a relationship between PTSD and chronic guilt with guilt-proneness and fear of death as a predictor of psychological distress |

Galpin, 2013, United Kingdom; Cross-sectional Correlational study | Fathers (n = 30) Mothers (n = 53) | Fathers 31 Mothers 31 (Median) | Range 30–36 | Range 1500–3500 | IES-R DSM-IV (Self-report) | 33 | The experience of having a premature baby hospitalized on the neonatal unit | 4–8 weeks post-discharge | 1 (3%) Fathers 10 (19%) Mothers | 19% of mothers and 3% of fathers met the clinical cut-off for probable PTSD. This study demonstrated positive correlations between PTSD and Post traumatic growth |

Lefkowitz, 2010, United States of America; Prospective study | Fathers (n = 25) Mothers (n = 60) | Fathers 33 Mothers 29 | Range < 30 and ≥ 30 | NR | PCL DSM-IV (Self-report) | One or more re-experiencing symptoms, three or more avoidance symptoms, and two or more arousal symptoms over the past month | Their infant's admission to the NICU | T2— ≥ 30 days post-admission (Median days 33) | 2 (8%) Fathers 9 (15%) Mothers | 15% of mothers and 8% of preterm infants' fathers met the clinical cut-off for PTSD. Positive correlations of PTSD included a family history of depression, anxiety, serious mental illness, and ASD |

Lotterman, 2019, United States of America; Longitudinal study | Mothers (n = 76) | 32.45 | 33.53 | NR | PCL DSM-IV (Self-report) | 38 | During hospitalization | T2—6 months | 15.8% Mothers | At 6 months, 15.8% of mothers of preterm infants met the clinical cut-off for symptoms of PTSD. There were no differences in symptoms at baseline and again at 6 months |

Schecter, 2020, United States of America; Longitudinal prospective study | Mothers Fathers (n = 80) | NR | 29% Extremely Preterm (< 28) 33% Very Preterm (28 to < 32) 38% Moderate to Late Preterm (33 to 37 weeks) 9% Full-term (> 37 weeks) | NR | PCL-C DSM-IV (Self-report) | > 30 | First day in the NICU and first week in the NICU | < 1 year and > 1 year | 9% Fathers 17% Mothers | 17% of mothers and 9% of fathers met the clinical cut-off for symptoms of PTSD at 12 months follow-up. There were no statistical differences in PTSD symptoms across gestational age or in mothers or fathers |

Shaw, 2009, United States of America; Prospective study | Mothers Fathers (n = 18) | Fathers 37 Mothers 33.96 | 30.89 | 1664.39 | DTS DSM-IV (Self-report) | 38 and 39 | Their reactions to having an infant hospitalized in the NICU | T2—4 months | 2 (33%) Fathers 1 (9%) Mothers | 33% of fathers and 9% of mothers met the clinical cut-off for symptoms of PTSD at 4 months. Significant correlations were found between ASD and PTSD |

Shaw, 2013, United States of America; Longitudinal study | Mothers (n = 50) | Mothers 32.7 | 31.9 | 1757 | DTS DSM-IV (Self-report) | ≥ 40 | During or after having an infant in the NICU | T2—1 month after discharge from hospital | 15 (30%) Mothers | 30% of mothers of preterm infants met the clinical cut-off for probable PTSD. Correlations of PTSD include ASD, dysfunctional coping, and years of education |

Appendix 3: PRISMA 2020 Checklist

Section and topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

|---|---|---|---|

TITLE | |||

Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review | 1 |

ABSTRACT | |||

Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist | 1 |

INTRODUCTION | |||

Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge | 4 |

Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses | 5 |

METHODS | |||

Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses | 5 and 7 |

Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted | 5 |

Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used | Appendix 1 |

Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | 6 |

Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | 6–7 |

Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect | 6–7 |

10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information | 6–7 | |

Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | 7 |

Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results | 6–7 |

Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)) | 6–7 |

13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions | 6–7 | |

13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses | 6–7 | |

13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used | N/A | |

13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression) | N/A | |

13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results | N/A | |

Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases) | 7 |

Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome | N/A |

RESULTS | |||

Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram | 7 and Fig. 1 |

16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded | 7 | |

Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics | Table 1 |

Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study | 7 |

Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots | N/A |

Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarize the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies | |

20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect | N/A | |

20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results | 8 | |

20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results | N/A | |

Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed | Figure 2 |

Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed | N/A |

DISCUSSION | |||

Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence | 9 |

23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review | 10 | |

23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used | 10 | |

23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research | 9–10 | |

OTHER INFORMATION | |||

Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered | 1, 5 |

24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared | 5 | |

24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol | 5 | |

Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review | 10 |

Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors | 10 |

Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review | 10 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKeown, L., Burke, K., Cobham, V.E. et al. The Prevalence of PTSD of Mothers and Fathers of High-Risk Infants Admitted to NICU: A Systematic Review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 26, 33–49 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00421-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00421-4