Abstract

The current study consists of a systematic review of the quantitative literature on siblings of individuals with mental illness (MI). Despite the prevalence of mental illness, little is known about how siblings are specifically affected in areas of psychosocial, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. The review yielded 56 studies that examined outcomes such as behavior problems, the sibling relationship, caregiving experiences, and knowledge of mental illness among siblings. The majority of studies from the initial search were focused on siblings-as-comparison group, examining siblings for risk factors for developing mental illness. In total, the study samples covered a sibling age range of 6–81 and a patient age range of 4–84. About half (k = 27) of the included studies had samples primarily composed of siblings of individuals with schizophrenia, leaving other MI diagnoses such as depression, anxiety, and mood disorders underrepresented. However, results from comparison studies were mixed—half found that the MI-Sibs had fewer negative outcomes than the comparison group, and half found that MI-Sibs had more negative outcomes. Multiple factors, including female sibling gender, greater severity of MI symptoms, and belief in the patient’s ability to control their own behavior, were all related to more negative outcomes for MI-Sibs. Future work will focus on expanding the representativeness of MI-Sibs samples and analyzing experiences of both the sibling and the individual with MI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although many researchers have examined the impact of mental illness on the family unit, many studies focus on parents or caregivers (e.g. Corrigan and Miller 2004) rather than siblings of individuals with mental illness (MI-Sibs). Among studies of MI-Sibs, many contain analyses of genetic or environmental risk and sub-clinical symptoms of MI (e.g. Sariaslan et al. 2016) to better identify etiology and early signs of various diagnoses. There are far fewer studies examining the experiences of MI-Sibs who do not have a diagnosis themselves. The current review will summarize the existing quantitative literature on the social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for siblings of individuals with mental illness across the lifespan. For purposes of the current study, classification of mental illness will exclude neurodevelopmental disorders, as defined by the DSM-V (e.g., intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, etc.; APA 2013).

Families of Individuals with Mental Illness

Families

The family literature shows that a diagnosis of MI can have broad, long-lasting impacts on non-diagnosed family members (e.g. Saunders 2003). Family members can experience increases in caregiving activities across the lifespan, stress from crisis situations, and stigma by association (Saunders 2003). Many studies focus on the challenges of mental illness, with families describing struggles and caution, coping and resilience (Flood-Grady and Koenig Kellas 2018; Zauszniewski et al. 2010). Most such studies use the framework of caregiving and provision of support, highlighting the different types of care and accommodation that family members provide for the individual with MI (McCann et al. 2015). From the perspective of the individual with MI, studies have also highlighted the importance of supportive family relationships on the health of the diagnosed individual (e.g., Waller et al. 2019). Together, the literature, on average, suggests that families are important sources of support for individuals with MI, especially when faced with a dearth of formal supports, but that caring for individuals with MI is a “difficult and demanding responsibility” (McCann et al. 2015, p. 203). Because many studies on families overall do not provide separate analyses for siblings, it is not clear to what extent MI-Sibs experience potential caregiving burden or provide support for the individual with MI. It is also not known if there are any benefits, perceived or otherwise, to having a brother or sister with MI.

Parents

In terms of individual family members of individuals with MI, the majority of research thus far has focused on the experience of parents or caregivers, particularly mothers (Corrigan and Miller 2004). Studies have shown that, compared to mothers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), mothers of individuals with MI report higher levels of burden and depressive symptoms (Greenberg et al. 1997). However, mothers with higher levels of optimism and flexibility tend to have fewer negative outcomes, such as depressive symptoms (Greenberg et al. 2004; Seltzer et al. 2004), showing that numerous individual factors can impact outcomes for family members of individuals with MI. Specifically, mothers’ stigmatized appraisals of mental illness (that is, how negatively the mothers view their children’s mental illness) significantly predicted both the child’s symptom severity and life satisfaction over time (Markowitz et al. 2011). Collectively, the literature on parents of individuals with MI suggests that parents can face numerous challenges, but that supportive traits and strategies, including individual appraisals and coping styles, can contribute to more positive outcomes.

Siblings

Although studies of parents and the entire family unit are important, siblings are likely to have different perspectives than the parents. The sibling relationship is typically the longest relationship a person will have in their lifetime (Cicirelli 1995), and siblings tend to navigate similar developmental stage of life concurrently (e.g. Goetting 1986). The life course perspective (e.g. Settersen 2003) therefore suggests that a large event, such as the diagnosis of MI, for one sibling, can result in life course alterations for all other siblings. These potential alterations are not well understood among siblings. Early literature focused on a deficit model, identifying increased risk for MI diagnosis among siblings in adulthood (e.g., Heston 1966; Lidz 1963) and increased risk for emotional, social, and behavioral impairments (e.g., DeLisi 1987; Weismann and Seigel 1972, both adult samples).

However, like many areas of human research, more recent studies have examined a broader sample of sibling experiences, with several studies collecting qualitative data from siblings themselves, discussing their own stories and opinions. Many adult siblings feel reluctant in regards to providing care for their brother or sister with MI, and the sibs’ tolerance of the brother or sister’s behavior could be related to the siblings’ interpretation of said behavior (Johnson 2000). That is, if the siblings believe that the individual with MI is being lazy or stubborn, then the siblings are less sympathetic toward their brother or sister, as opposed to siblings who interpret the behavior as part of the illness (Johnson 2000). Reflecting on their childhood experiences, some adult siblings have described physically removing themselves from difficult situations with their brother or sister with MI when they were children—keeping busy through extracurricular activities or simply going to their room at home (Kinsella et al. 1996). Siblings report similar distancing strategies in adulthood, particularly if the family is disorganized in response to the brother/sister’s mental health crises (Graves et al. 2020).

Kovacs et al. (2019) propose the theory of relational dialectics (Baxter 2004) and the concept of ambiguous loss to help understand the varied experiences of MI-Sibs. The dialectical tensions between stressors that arise from a brother or sister’s mental illness and the adjustment and resilience MI-Sibs develop can contribute to varying descriptions and results in studies of MI-Sibs (Kovacs et al. 2019) Additionally, ambiguous loss can be used to describe experiences with a family member who is still living, but whose mental illness can contribute to the loss of former roles and relationships (Kovacs et al. 2019). The theories results from such qualitative studies are enlightening and beneficial. The current review will examine quantitative studies of sibling outcomes to determine how much quantitative results from studies of MI-Sibs’ emotional, behavioral, and social outcomes align with the way siblings speak about their own experiences in qualitative research.

Factors that May Affect Sibling Experiences

Diagnosis

“Mental illness” is, in and of itself, an incredibly broad category. Therefore, the experiences of siblings of individuals with schizophrenia may be very different than the experiences of individuals with anorexia. Further, the experiences of two siblings of two different individuals with schizophrenia can be substantially different from each other. In the literature, many studies focus on “serious” or “severe” mental illness (SMI), categories that are defined in the United States as disorders that meet DSM criteria and result in impairment that interferes with at least one major life activity (National Institute of Mental Health 2013). Although the official definition does not exclude any specific diagnoses, studies of families of individuals with SMI often include individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or psychosis (e.g. Erickson et al. 1998; Greenberg et al. 1997). Thus, there seem to be fewer studies on family experiences of individuals with eating disorders, personality disorders, or major depressive disorder, despite the fact that such diagnoses can also result in impairment that meets the definition of “severe.” Studies may use the general definition of SMI as an inclusion criterion or may focus on families of individuals who have been hospitalized due to mental illness (e.g. Gerson and Rose 2012). Although such studies are certainly necessary to understand the sibling and family experience, they do not reflect the full spectrum of outcomes for siblings. Thus, it is important to also consider siblings of individuals with other MI diagnoses, including other symptoms and other levels of severity.

Demographics

Beyond diagnosis and severity, demographic factors can certainly also play a role in sibling outcomes. Studies have shown that African-American or Latino siblings tend to be more involved in caregiving due to the more communal cultural expectations (Guarnaccia and Parra 1996; Horwitz and Reinhard 1995, both adult samples). Gender also plays a role, as adult female siblings report providing more emotional support than male siblings (Greenberg et al. 1999), and greater overall perception of burden than male siblings (Greenberg et al. 1997). The gender of the brother or sister with MI may also play a role, as adult siblings of sisters with MI reported higher levels of psychological well-being than siblings of brothers with MI, as compared to siblings of individuals with IDD or siblings of typically-developing individuals (Taylor et al. 2008).

Interventions

Sibling support groups are one of the many areas in which services have outpaced literature. Across the country, variations on support groups and services for siblings of individuals with intellectual disability, chronic illness, or mental illness exist to provide information and opportunities for understanding from other siblings (e.g., Meyer and Vadasy 1994). Organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) provide peer-led activities for family members of individuals with MI (www.nami.org), and several organizations provide pamphlets and articles online (Griffiths and Sin 2013). However, a recent review found that the vast majority of empirical studies on such support groups for younger individuals (i.e., under 18) focus on siblings of individuals with physical illness or disability and/or intellectual and developmental disabilities rather than siblings of individuals with mental illness (Smith et al. 2018). The review concluded that such interventions resulted in improvements in behavior and knowledge of illness and disability (Smith et al. 2018), suggesting that the presence of support programs or interventions may be beneficial to MI-Sibs, as well. The availability of these programs could have a positive impact on the overall sibling experience.

The Current Study

The current study aims to review the extant quantitative literature on psychosocial and behavioral outcomes among typically-developing siblings of individuals with mental illness (e.g., siblings without a mental illness themselves), age 5 and older. The review will describe the demographics of the existing studies—gender and age of the siblings and individuals with MI, makeup of any comparison groups, nature of the brother/sister’s MI—as well as the outcomes being explored, covering all peer-reviewed studies available in English through 2019. The goal is to determine what is currently known about the experiences of typically-developing MI-Sibs and what are the gaps in the literature to help guide future sibling and family researchers.

Methods

The present study utilized Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al. 2009) guidelines to conduct a systematic review of all peer-reviewed articles published up through December of 2019. Because no such review of MI-Sibs has been published to date, there was no limit on the earliest date of publication.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria for the current review were defined as follows: (a) peer-reviewed, published articles, (b) available in English, (c) articles describe quantitative results from empirical studies, (d) article describes results for non-diagnosed siblings of individuals with MI (if the article included a mixed sample of MI-sibs and non-MI-Sibs, at least one of the results had to be described separately—that is, exclusively for MI-Sibs), (e) at least one of the results describes psychological, behavioral, or emotional outcomes for the MI-Sibs that were not diagnostic in nature. That is, studies the solely examined MI-Sibs for the purpose of assessing risk for developing MI or identifying sub-clinical symptoms or early signs of MI were not eligible. Studies were excluded if (a) the purpose of the study was to measure risk for developing MI among MI-Sibs, (b) the study did not report separate analyses for siblings (e.g. the sample included parents and/or other family members), or (c) “sibling” was only used as a single predictor variable in regression analyses. Several studies did include a subsample of siblings among the sample of family members in general, but exclusive reports of sibling outcomes were not given; “sibling” was only used as a categorical variable in regression analyses (e.g. comparing the predictive value of being a sibling as opposed to a parent, spouse, or child of the individual with MI).

Literature Search

Three large, online databases were searched: PsychInfo, EBSCOHost, and Web of Knowledge. The search was limited to peer-reviewed articles published through December of 2019 and used the following Boolean search terms: (sibling* OR brother OR sister) AND (“mental illness” OR “psychopatholog*” OR depression OR anxiety OR bipolar OR schizophrenia OR “self harm” OR “personality disorder” OR “axis 1” OR “axis 2” OR “OCD”).

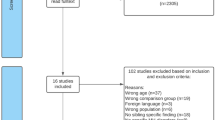

Titles were reviewed, yielding a total of 388 unique articles to be examined by abstract and/or full manuscript for further inclusion. Due to the broad range of potential MI diagnoses, the references of initially identified studies were examined for articles that may not have been included in the original search; this process yielded an additional 3 articles that were included in the review. Both authors reviewed the abstracts of the 391 total articles to determine if quantitative results were reported. This process narrowed down the list of eligible articles to 67; once coding was conducted, a further eleven manuscripts were excluded, either because “sibling” was only used as a predictor category in regression analyses or because the purpose of the study was to identify risk factors for MI, not understand the sibling experience. The final result was 56 eligible articles for inclusion. The flowchart for study inclusion can be found in Fig. 1.

Data Extraction

Studies that met all inclusion criteria were read by the authors to extract information pertinent to the review. Data extraction was based on the PICOS method (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study Design; Higgins et al. 2019); however, because the goal of the review was to synthesize all existing quantitative literature on MI-Sibs that did not exclusively assess MI risk, interventions (I) were not required. Coding manuals were completed for each of the 56 included articles with all available information on participant demographics (siblings, individuals with MI, and any comparison groups), study methods, and results. Because of the wide range of study methods and purposes, results were split into two categories: between-group results (results comparing MI-Sibs to other samples) and within-group results (descriptive analyses or analyses describing statistical relationships among two or more variables; this category included regression analyses). Each category included a wide range of outcome measures and related variables. The two authors met frequently to compare codes, and any discrepancies were discussed and examined until the authors reached a consensus.

To assess study quality, the assessment rubric for quantitative studies developed by Kmet et al. (2004) was used. The rubric includes 14 assessment items (e.g., “Design evident and appropriate to answer study question,” “Analysis described and appropriate”) that are each rated on a 3-point scale (0 = no, 1 = partial, 2 = yes). Average quality scores are calculated by summing the total score and dividing by the highest possible score (number of relevant items × 2); thus, each quality score is represented as a decimal between zero and one, with higher numbers indicating greater article quality.

Results

Our review yielded a total of 56 peer-reviewed, quantitative studies that analyzed social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for MI-Sibs, reporting on a variety of outcomes for siblings.

Population

The search yielded 30 studies that included a comparison group and 26 studies that had no comparison group (two of the 26 studies with no explicit comparison group compared the study sample to population norms of the included measures, and one compared its sample to data from a previously published study). Sample sizes for the MI-Sibs ranged from 9 to 746; sample sizes for the individuals with MI ranged from 11 to 746. The majority of studies (k = 41, 73.2%) focused on adult siblings and the studies had more female siblings than male siblings (as is common in general sibling research). Four studies (7.8%) described multiple sibling samples, either from different study locations or in different treatment groups. These samples are described on separate lines in the demographics tables (Tables 1 and 2). The majority of studies (62.5%; k = 35) included adult samples; eight studies (14.3%) reported on child samples (i.e., every sibling participant was under the age of 18), and eight (14.3%) reported on samples that included both child and adult sibling. The remaining five studies (8.9%) did not include sufficient information about the age range to determine whether individuals under 18 were included. However, the overall demographics of the total sample were difficult to obtain. Seven (12.5%) studies did not report the gender breakdown, and three (5.4%) of the studies did not report the age breakdown of the sibling samples; 18 (32.1%) did not report the gender of the individuals with MI, and 17 (30.4%) gave no information on the age of the individuals with MI.

In terms of the diagnoses of the individuals with MI, seventeen (30.4%) studies had samples focusing on a singular MI, while thirty-nine (69.6%) contained multiple MI diagnoses. The proportion of studies that were, at least in part, focused on siblings of individuals with schizophrenia was overwhelming. Nine (16.1%) reported schizophrenia as the singular MI in their study. Of those studies with mixed samples, eighteen (32.1%) reported schizophrenia as the majority sample in their article. Eleven (19.6%) reported schizophrenia as the minority or unspecified amount in their study, resulting in a total of 38 samples (67.9%) that included at least some siblings of individuals with schizophrenia. Other diagnoses reported in the studies included eating disorders, personality disorders, mood disorders, obsessive/compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

Methods

The included studies utilized a variety of methods, the most common of which was self-administered questionnaires (k = 42, 75.0%). Other methods included structured or semi-structured interviews (both in person or over the phone), clinical observations, use of data from medical records, neuropsychological test batteries, and secondary analysis of data from both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. Four (7.8%) of the studies reported on interventions for MI-Sibs and family members, analyzing change in measured variables from pre-intervention to post-intervention. Possibly because so many studies focused on adult siblings (rather than child or adolescent siblings), the majority of studies used sibling self-report (k = 52, 92.9%). Other methods included parent/caregiver report and researcher observation.

Study Results

Between-Group Results

Of the studies that compared MI-Sibs to another sample, nine found the MI-sibs to be “worse” than the comparison group, that is, the MI-Sibs had significantly higher scores on measures of ill-being [e.g., more depressive symptoms (Latzer et al. 2015); poorer sibling relationships (Tschan et al. 2019)], while four studies noted the MI-sibs results were not significantly different than the comparison group on measures of expressed emotion (Moulds et al. 2000), temperament (Kelvin et al. 1996), internalizing or externalizing problems (Hudson and Rapee 2002), or quality of life (Tatay-Montiega et al. 2019). Nine studies found that the MI-sibs were had “better” results that the comparison group [e.g., less emotional distress (Zauszniewski and Bekhet 2014), less sibling conflict (Jacoby and Heatherington 2016)]. However, the composition of these comparison groups was widely varied. Of the comparison groups that reported “worse” outcomes than MI-Sibs (that is, the sibs were doing “better” than the comparison group), three were comprised of MI-Parents (that is, the studies found that MI-Sibs were less severely affected than MI-parents), four were comprised of typically-developing siblings or community samples, and one was comprised of siblings of individuals with intellectual disability. The final group was an intervention study, which found that siblings in the treatment group fared better than siblings in the “treatment as usual” group. In contrast, the majority of comparison samples in which the comparison group was doing “better” than the MI-Sibs were composed of community samples (e.g. Barnett and Hunter 2012) or siblings of typically-developing individuals (TD-Sibs; e.g. Deal and MacLean 1995).

In terms of findings, the comparison results were decidedly mixed. Some studies found worse sibling relationships for MI-Sibs (Barak and Solomon 2005; Fox et al. 2002), while others found lower levels of negativity in the sibling relationship for MI-Sibs (Deal and Maclean 1995; Jacoby and Heatherington 2016). MI-Sibs were reported to have higher rates of behavior problems (Barnett and Hunter 2012; Deal and MacLean 1995) in some studies, but lower levels of internalizing behaviors (as reported by fathers, but not mothers) in another study (Barrett et al. 2005). Some studies found poorer emotional outcomes for MI-Sibs in relation to comparison groups (Latzer et al. 2015), while others found no differences on temperament (Kelvin et al. 1996). A full description of comparison results can be found in Table 3.

Within-Group Results

The single most common result from the included studies is that female MI-Sibs have more negative outcomes than male MI-Sibs (e.g. Bowman et al. 2014; Greenberg et al. 1997). A total of 11 studies examined gender as a contributing factor, and every one reported more negative outcomes for female MI-Sibs and/or more caregiving responsibility for female MI-Sibs. Additionally, severity of the brother/sister’s symptoms was consistently found to be related to higher rates of caregiving (e.g., Horowitz 1993) and poorer outcomes for MI-Sibs (e.g., Bowman et al. 2014; Tanaka 2011). Additionally, increased MI-Sib belief in the patients’ ability to control their behavior was related to more negative sibling outcomes (e.g. Greenberg et al. 1997; Smith et al. 2007).

Numerous outcomes were examined by within-group analyses, with the two most common being mental health of the MI-Sib and family functioning. Although the current review did not include studies that exclusively focused on rates of psychopathological diagnoses among MI-Sibs, many studies still included continuous measures of mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety (e.g. Barak and Solomon 2005; Lively et al. 1995). The MI-Sibs’ own mental health was related to the severity of the brother/sister’s symptoms (e.g., Lively et al. 1995), as well as the brother/sister’s duration of illness (van Langenberg et al. 2016). Seven studies measured aspects of family functioning, with most finding that poorer family functioning was related to more negative MI-Sib outcomes, including greater levels of internalizing behavior problems and overall impairment (Dia and Harrington 2006; Hoover and Franz 1972). Full summaries of within-group results can be found in Table 3.

Over Time Results

Most of the studies that reported results over time analyzed the impact of intervention programs, with one exception; Barak and Solomon (2005) had siblings report their own perceptions of how the sibling relationship had changed over time. MI-Sibs reported that their relationship with the patient had gotten worse, while TD-Sibs reported their sibling relationships had improved (Barak and Solomon 2005). Of the intervention studies, the results were mixed. Two studies reported positive outcomes of the interventions, with MI-Sibs in the treatment groups reporting increases in knowledge of MI (Amaresha et al. 2018; Landeen et al. 1992) and decreases in self-stigma (Amaresha et al. 2018). In contrast, the other two studies reported no effect of treatment (Barrett et al. 2004; van Langenberg et al. 2016), though both treatment and comparison groups in the Barrett et al. (2004) study reported decreases in depression and accommodation of the patient over time.

Article Quality

The article quality varied greatly, ranging from 0.364 to 0.955, with an average quality score of 0.674 (SD = 0.154). The middle 50% of values ranged from 0.556 to 0.788, and only 4 articles had quality scores greater than 0.90. Just over half of the studies (53.6%, n = 30) scored full points for “study design is evident and appropriate,” but only six studies (10.7%) adequately described “method of subject/comparison group selection.” Additionally, 11 studies (19.6%) did not control for confounding at all (i.e., were rated 0 for that item), and four studies (7.1%) did adequately define outcomes measures and/or report means of assessment measures.

Discussion

The current study consists of a systematic review of the literature on outcomes for siblings of individuals with mental illness. The majority of the research on MI-Sibs involves risk studies; that is, studies conducted to determine how at-risk MI-Sibs are for developing mental illness themselves or to identify subthreshold symptoms of a given MI to use for future diagnostics. Although these studies certainly have value for etiological and treatment purposes, they do little to illuminate the experiences of typically-developing siblings and how these siblings are affected by their brother or sister’s MI. The studies included in the current review identify several outcomes for MI-Sibs, but overall, the review highlights the numerous gaps in the sibling literature.

First, despite most reports of schizophrenia putting the prevalence below 1% (Moreno-Kustner et al. 2018), just under half of the included studies in our sample focused primarily or entirely on siblings of individuals with schizophrenia, with another eleven studies including a minority or unspecified percentage of schizophrenic patients. The impact of schizophrenia on the family unit and relationships in general can be profound and widespread, so it is important to understand the experiences of siblings. However, the current review revealed just how little is known about siblings of individuals with other diagnoses. Although symptoms of depression and anxiety may be less severe than those of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, it would be unwise to presume that the siblings of individuals with these diagnoses are unaffected. Additionally, far more research is needed about siblings of individuals with other less-prevalent diagnoses, such as eating disorders or personality disorders. We hope that this review will illustrate the importance of understanding siblings of individuals with MI and just how much work is still needed within this population.

Second, although the review included over two-dozen comparative studies (studies that compared MI-Sibs to another population), the results of these studies varied quite a bit. Some studies found that MI-Sibs reported more negative outcomes than comparison groups, while some found that MI-Sibs reported fewer negative (or more positive) outcomes. Because these studies included such a diverse set of outcomes (sibling relationship, behavior problems, temperament, etc.) and comparison groups (siblings of typically-developing individuals, other relatives of individuals with MI, etc.), it is challenging to make any generalizations about the results. Due to the variability in family constellation, severity of MI, differences across diagnoses, and many other potential contributory variables, it is likely that few conclusions overall can be drawn about MI-Sibs as an entire population. Therefore, while comparison studies are valuable and should be explored further, it is important to measure individual differences when researching experiences of MI-Sibs.

Despite the variability in measures and methods, the current review did yield a few consistent themes. In terms of outcomes, ten of the studies included continuous measures of sibling mental health. Although studies exclusively focusing on sibling diagnostic rates were not eligible for inclusion in the current review, studies that used quantitative measures of depression or anxiety to indicate more general fluctuations in mood were summarized. It is difficult to disentangle shared genetics from shared experience when it comes to analyzing mental health among MI-Sibs, but mental health is still a worthy concentration. Other family studies, including studies of families of individuals with IDD, assess mental health (e.g., Emerson 2003) as a way of understanding the impact of having a brother, sister, or child with a disability. Therefore, measures of mental health, especially continuous measures (i.e., not strictly diagnostic rates) should continue to be explored in MI-Sib studies as well.

More studies overlapped in their use of predictor or correlational variables, with multiple studies each examining the impacts of sibling gender, severity of MI, and sibling knowledge of mental illness. As is consistent with other populations, female MI-Sibs were more likely than male sibs to provide caregiving, and, when asked, female siblings reported more severe behavior problems for the brother/sister with MI than did male siblings (Lively et al. 2004). Additionally, studies that included measures of MI severity consistently linked a negative relationship between severity and sibling outcomes (i.e. greater symptom severity was related to poorer sibling outcomes). However, some studies also included measures of sibling knowledge of MI and sibling attributions of control over MI. The more siblings understood about the progression and etiology of mental illness, the less likely they were to make negative control attributions of their brother/sister’s illness. As MI in general is still largely misunderstood globally (Rüsch et al. 2005), many siblings may not have a comprehensive idea of what their brother or sister is going through; therefore, educational interventions for siblings and other family members may help buffer against negative consequences for both the sibling and the individual with MI.

Implications

The current review has numerous implications for research and practice. First, as mentioned above, the review clearly identifies gaps in the MI-Sib literature, the most prominent of which being the lack of studies on siblings of individuals with more commonly-diagnosed disorders, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and mood disorders. Because of the significant variability in symptoms, treatment, and societal perception, it is important to study sibling experiences among families of individuals with varying MI diagnoses. Additionally, very few studies included the perspective of the individual with MI. To more fully understand the sibling relationship and the impact of MI on family members, including reports from the patient is essential. In terms of study methods, researchers should explore practices beyond self-report (though self-report is certainly very valuable). Because certain events related to mental illness can be traumatic—hospitalizations, suicide attempts, etc.—it is important to understand how such events may impact the sibling. Methods such as biofeedback can help pinpoint the physiological impacts of recollection of such events. Additionally, to better understand the impact of MI on siblings, it is important to assess siblings across the lifespan. Adult siblings, who may not live with the individual with MI may have very different outcome than child or adolescent siblings who still live at home and are thus more directly present to symptoms of MI.

For families and service providers, one of the most important recommendations is to include siblings in support activities. As mentioned above, knowledge of mental illness may help improve both sibling outcomes and the sibling relationship, and even one-day workshops (e.g., Landeen et al. 1992) can significantly improve sibling’s understanding of MI. Media portrayals of mental illness are often skewed and inaccurate (e.g., Stuart 2006); therefore, promoting understanding among siblings may have to include debunking commonly-held, yet incorrect beliefs about people with MI. Additionally, simple awareness that siblings can be impacted by their brother or sister’s illness can help families prepare to seek out support systems for the siblings. Again, this process may look different at different stage of the lifespan—young children not understanding why their brother or sister with MI acts the way they do to adult siblings considering whether or not to have their own children, given the genetic linkage of mental illness. Several of the included studies found that more severe MI symptoms were related to more negative sibling outcomes (e.g., Bowman et al. 2014; Horowitz 1994); therefore, siblings who are exposed to more severe and traumatic behaviors and events may be more at risk for negative outcomes. Families and clinicians should take special care to address potential sibling outcomes, especially if the individual with MI is hospitalized or otherwise engaged in rehabilitation treatment.

Limitations

As with all literature reviews, the current manuscript is limited by the content of the included studies. A substantial barrier to general interpretation of the current review lies in the variance in the information studies provided. Not only did several studies not include basic demographic information, such as age and gender (e.g., Hudson and Rapee 2002; Tanaka 2008), but many published studies did not report statistics in a way that permitted interpretation of individual variables. For example, Jewell and Stein (2002) reported model fit indices for their regression models, but not beta values for individual variables. Therefore, we cannot determine which variables (e.g. sibling affection, parent support) independently contribute to variance in sibling caregiving (Jewell and Stein 2002). While severity of MI was consistently found to relate to sibling outcomes, the majority of included studies did not assess symptom severity. Additionally, some studies (e.g., Chen and Lukens 2011; Tatay-Montiega et al. 2019) did not specify which individuals with MI were related to the siblings in the sample. That is, the samples were reported collectively (e.g., relatives were listed separately—mothers, fathers, siblings—but demographic information about the entire MI group was reported together), or listed MI groups separately, but siblings collectively. Such presentation of demographics prevents researchers from determining which characteristics of the individuals with MI are related to sibling outcomes. Finally, it is important to note that the current review excluded samples in which the MI-Sib had a mental illness themselves. Due to the heritability of mental illness, this exclusion criteria leaves out a likely substantial proportion of MI-Sibs and thus, the results are not generalizable to all siblings of individuals with mental illness. These limitations in reporting not only hinder interpretation of the individual study, but it limits the potential of such studies being included in future meta-analyses.

Additionally, the current review attempts to summarize a wide range of potential outcomes for siblings. Thus, the included categories may have some redundancy across descriptions. That is, the categories are not necessarily clear-cut. Finally, when discussing family impacts of MI, it is always important to acknowledge the possibility of shared genetic variance. Although the current review was limited to siblings without a diagnosis of MI themselves, it is impossible to know how many of these siblings experience subthreshold MI symptoms or perhaps qualified for, but have not yet received, an MI diagnosis. Therefore, the classification of “typically-developing” siblings is, in and of itself, somewhat artificial.

Conclusion

The current study is the first review of its kind to summarize the quantitative literature on psychosocial and behavioral outcomes among siblings of individuals with mental illness. The included studies covered a wide range of measures and outcomes, allowing for few consistent areas of interpretation. However, the review makes several important contributions to the literature. First, the study highlights the gaps in knowledge regarding siblings of individuals with less-severe MI, such as depression or anxiety. Second, the review identifies the importance of knowledge and understand of MI for both the siblings themselves and the sibling relationship. Finally, the review calls attention to the needs of MI-Sibs in general. We hope that future researchers, families, and service providers can continue to explore ways to best support siblings of individuals with mental illness and promote positive family relationships across the life course.

References

*Indicates articles included in the review

*Amaresha, A. C., Kalmady, S. V., Joseph, B., Agarwal, S. M., Narayanaswamy, J. C., Venkatasubramanian, G., et al. (2018). Short term effects of brief need based psychoeducation on knowledge, self-stigma, and burden among siblings of persons with schizophrenia: A prospective controlled trial. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 32, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.030.

American Psychological Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Avcıoğlu, M. M., Karanci, A. N., & Soygur, H. (2019). What is related to the well-being of the siblings of patients with schizophrenia: An evaluation within the Lazarus and Folkman’s Transactional Stress and Coping Model. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65(3), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019840061.

*Barak, D., & Solomon, Z. (2005). In the shadow of schizophrenia: A study of siblings' perceptions. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 42(4), 234.

*Barnett, R. A., & Hunter, M. (2012). Adjustment of siblings of children with mental health problems: Behaviour, self-concept, quality of life and family functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(2), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9471-2.

*Barrett, P. M., Fox, T., & Farrell, L. J. (2005). Parent—Child interactions with anxious children and with their siblings: An observational study. Behaviour Change, 22(4), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.22.4.220.

*Barrett, P., Healy-Farrell, L., & March, J. S. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral family treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: A controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200401000-00014.

Baxter, L. A. (2004). A tale of two voices: Relational dialectics theory. Journal of Family Communication, 4(3–4), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327698jfc0403&4_5.

*Bowman, S., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Wade, D., Howie, L., & McGorry, P. (2014). The impact of first episode psychosis on sibling quality of life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(7), 1071–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0817-5.

Chen, W. Y., & Lukens, E. (2011). Well being, depressive symptoms, and burden among parent and sibling caregivers of persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Social Work in Mental Health, 9(6), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2011.575712.

Cicirelli, V. G. (1995). Sibling relationships across the life span. New York: Plenum Press.

Corrigan, P. W., & Miller, F. E. (2004). Shame, blame, and contamination: A review of the impact of mental illness stigma on family members. Journal of Mental Health, 13(6), 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230400017004.

*Deal, S. N., & MacLean, W. E., Jr. (1995). Disrupted lives: Siblings of disturbed adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65(2), 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079616.

DeLisi, L. E., Goldin, L. R., Maxwell, M. E., Kazuba, D. M., & Gershon, E. S. (1987). Clinical features of illness in siblings with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44(10), 891–896. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800220057009.

*Dia, D. A., & Harrington, D. (2006). What about me? Siblings of children with an anxiety disorder. Social Work Research, 30(3), 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/30.3.183.

Emerson, E. (2003). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00464.x.

Erickson, D. H., Beiser, M., & Iacono, W. G. (1998). Social support predict 5-year outcome in 1st-episode schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(4), 681–685. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.107.4.681.

Flood-Grady, E., & Koenig Kellas, J. (2018). Sense-making, socialization, and stigma: Exploring narratives told in families about mental illness. Health Communication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1431016.

*Fox, T. L., Barrett, P. M., & Shortt, A. L. (2002). Sibling relationships of anxious children: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(3), 375–383. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3103_09.

*Friedrich, R. M., Lively, S., & Rubenstein, L. M. (2008). Siblings' coping strategies and mental health services: A national study of siblings of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 59(3), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.3.261.

Gerson, L. D., & Rose, L. E. (2012). Needs of persons with serious mental illness following discharge from inpatient treatment: Patient and family views. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(4), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2012.02.002.

Goetting, A. (1986). The developmental tasks of siblingship over the life cycle. Journal of Marriage and the Family. https://doi.org/10.2307/352563.

Graves, J. M., Marsack-Topolewski, C. N., & Shapiro, J. (2020). Emerging adult siblings of individuals with schizophrenia: Experiences with family crisis. Journal of Family Issues. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x20905327.

*Greenberg, J. S., Kim, H. W., & Greenley, J. R. (1997). Factors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080226.

Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., Krauss, M. W., Chou, R. J. A., & Hong, J. (2004). The effect of quality of the relationship between mothers and adult children with schizophrenia, autism, or Down syndrome on maternal well-being: The mediating role of optimism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.74.1.14.

*Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., Orsmond, G. I., & Krauss, M. W. (1999). Siblings of adults with mental illness or mental retardation: Current involvement and expectation of future caregiving. Psychiatric Services, 50(9), 1214–1219. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.50.9.1214.

Griffiths, C., & Sin, J. (2013). Rethinking siblings and mental illness. The Psychologist, 26(11), 808–810.

Guarnaccia, P. J., & Parra, P. (1996). Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Mental Health Journal, 32(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02249426.

Heston, L. L. (1966). Psychiatric disorders in foster home reared children of schizophrenic mothers. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 112(489), 819–825. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.112.489.819.

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., et al., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley.

*Hoover, C. F., & Franz, J. D. (1972). Siblings in the families of schizophrenics. Archives of General Psychiatry, 26(4), 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750220044009.

*Horwitz, A. V. (1993). Adult siblings as sources of social support for the seriously mentally ill: A test of the serial model. Journal of Marriage and the Family. https://doi.org/10.2307/353343.

Horwitz, A. V. (1994). Predictors of adult sibling social support for the seriously mentally III: An exploratory study. Journal of Family Issues, 15(2), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x94015002007.

*Horwitz, A. V., & Reinhard, S. C. (1995). Ethnic differences in caregiving duties and burdens among parents and siblings of persons with severe mental illnesses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137221.

*Horwitz, A. V., Tessler, R. C., Fisher, G. A., & Gamache, G. M. (1992). The role of adult siblings in providing social support to the severely mentally ill. Journal of Marriage and the Family. https://doi.org/10.2307/353290.

Hudson, J. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2002). Parent–child interactions in clinically anxious children and their siblings. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(4), 548–555. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3104_13.

*Jacoby, R. J., & Heatherington, L. (2016). Growing up with an anxious sibling: Psychosocial correlates and predictors of sibling relationship quality. Current Psychology, 35(1), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9360-8.

*Jewell, T. C., & Stein, C. H. (2002). Parental influence on sibling caregiving for people with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 38(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1013903813940.

Johnson, E. D. (2000). Differences among families coping with serious mental illness: A qualitative analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087664.

*Kageyama, M., & Solomon, P. (2019). Physical violence experienced and witnessed by siblings of persons with schizophrenia in Japan. International Journal of Mental Health, 48(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2018.1563462.

*Kelvin, R. G., Goodyer, I. M., & Altham, P. M. E. (1996). Temperament and psychopathology amongst siblings of probands with depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(5), 543–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01440.x.

Kinsella, K. B., Anderson, R. A., & Anderson, W. T. (1996). Coping skills, strengths, and needs as perceived by adult offspring and siblings of people with mental illness: A retrospective study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 20(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095388.

Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Heslington: University of York.

Kovacs, T., Possick, C., & Buchbinder, E. (2019). Experiencing the relationship with a sibling coping with mental health problems: Dilemmas of connection, communication, and role. Health & social care in the community, 27(5), 1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12761.

*Landeen, J., Whelton, C., Dermer, S., Cardamone, J., Munroe-Blum, H., & Thornton, J. (1992). Needs of well siblings of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 43(3), 266–269. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.43.3.266.

*Laporte, L., Paris, J., Guttman, H., & Russell, J. (2011). Psychopathology, childhood trauma, and personality traits in patients with borderline personality disorder and their sisters. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(4), 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.448.

*Latzer, Y., Katz, R., & Berger, K. (2015). Psychological distress among sisters of young females with eating disorders: The role of negative sibling relationships and sense of coherence. Journal of Family Issues, 36(5), 626–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x13487672.

*Leith, J. E., Jewell, T. C., & Stein, C. H. (2018). Caregiving attitudes, personal loss, and stress-related growth among siblings of adults with mental illness. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(4), 1193–1206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0965-4.

*Leith, J. E., & Stein, C. H. (2012). The role of personal loss in the caregiving experiences of well siblings of adults with serious mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(10), 1075–1088. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21881.

Lidz, T., Fleck, S., Alanen, Y. O., & Cornelison, A. (1963). Schizophrenic patients and their siblings. Psychiatry, 26(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1963.11023334.

*Lively, S., Friedrich, R. M., & Buckwalter, K. C. (1995). Sibling perception of schizophrenia: Impact on relationships, roles, and health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 16(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612849509006937.

*Lively, S., Friedrich, R. M., & Rubenstein, L. (2004). The effect of disturbing illness behaviors on siblings of persons with schizophrenia. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 10(5), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390304269497.

*Lohrer, S. P., Lukens, E. P., & Thorning, H. (2002). Evaluating awareness of New York’s assisted outpatient treatment law among adult siblings of persons with mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 8(6), 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/00131746-200211000-00006.

*Lohrer, S. P., Lukens, E. P., & Thorning, H. (2007). Economic expenditures associated with instrumental caregiving roles of adult siblings of persons with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 43(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-005-9026-3.

Markowitz, F. E., Angell, B., & Greenberg, J. S. (2011). Stigma, reflected appraisals, and recovery outcomes in mental illness. Social Psychology Quarterly, 74(2), 144–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272511407620.

McCann, T. V., Bamberg, J., & McCann, F. (2015). Family carers' experience of caring for an older parent with severe and persistent mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12135.

Meyer, D. J., & Vadasy, P. F. (1994). Sibshops: Workshops for siblings of children with special needs. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Moreno-Küstner, B., Martin, C., & Pastor, L. (2018). Prevalence of psychotic disorders and its association with methodological issues. A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0195687. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195687.

*Moulds, M. L., Touyz, S. W., Schotte, D., Beumont, P. J., Griffiths, R., Russell, J., et al. (2000). Perceived expressed emotion in the siblings and parents of hospitalized patients with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 27(3), 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200004)27:3<288:aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-7.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2013, February 4). The numbers count: Mental disorders in America. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-numbers-count-mental-disorders-in-america/index.shtml.

*Oliver, J. M., Handal, P. J., Finn, T., & Herdy, S. (1987). Depressed and nondepressed students and their siblings in frequent contact with their families: Depression and perceptions of the family. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11(4), 501–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01175359.

*Östman, M., Wallsten, T., & Kjellin, L. (2005). Family burden and relatives' participation in psychiatric care: Are the patient's diagnosis and the relation to the patient of importance? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 51(4), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764005057395.

Rüsch, N., Angermeyer, M. C., & Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004.

*Samuels, L., & Chase, L. (1979). The well siblings of schizophrenics. American Journal of Family Therapy, 7(2), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187908250313.

*Sanders, A., & Szymanski, K. (2012). Emotional intelligence in siblings of patients diagnosed with a mental disorder. Social Work in Mental Health, 10(4), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2012.660304.

*Sanders, A., & Szymanski, K. (2013a). Having a mentally ill sibling: Implications for attachment with parental figures. Social Work in Mental Health, 11(6), 516–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2013.792312.

*Sanders, A., & Szymanski, K. (2013b). Siblings of people diagnosed with a mental disorder and posttraumatic growth. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(5), 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9498-x.

*Sanders, A., Szymanski, K., & Fiori, K. (2014). The family roles of siblings of people diagnosed with a mental disorder: Heroes and lost children. International Journal of Psychology, 49(4), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/e644732012-001.

Sariaslan, A., Larsson, H., & Fazel, S. (2016). Genetic and environmental determinants of violence risk in psychotic disorders: A multivariate quantitative genetic study of 1.8 million Swedish twins and siblings. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(9), 1251–1256. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.184.

Saunders, J. C. (2003). Families living with severe mental illness: A literature review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24(2), 175–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840305301.

Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., Floyd, F. J., & Hong, J. (2004). Accommodative coping and well-being of midlife parents of children with mental health problems or developmental disabilities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.187.

*Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., Krauss, M. W., Gordon, R. M., & Judge, K. (1997). Siblings of adults with mental retardation or mental illness: Effects on lifestyle and psychological well-being. Family Relations. https://doi.org/10.2307/585099.

Settersten, R. A. (2003). Age structuring and the rhythm of the life course. In R. H. Binstock & L. K. George (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 81–98). Boston, MA: Springer.

*Sin, J., Murrells, T., Spain, D., Norman, I., & Henderson, C. (2016). Wellbeing, mental health knowledge and caregiving experiences of siblings of people with psychosis, compared to their peers and parents: An exploratory study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(9), 1247–1255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1222-7.

*Smith, M. J., & Greenberg, J. S. (2008). Factors contributing to the quality of sibling relationships for adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 59(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.57.

*Smith, M. J., Greenberg, J. S., Sciortino, S. A., Sandoval, G. M., & Lukens, E. P. (2016). Life course challenges faced by siblings of individuals with schizophrenia may increase risk for depressive symptoms. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 12(1), 147–151. https://doi.org/10.25149/1756-8358.1201003.

*Smith, M. J., Greenberg, J. S., & Seltzer, M. M. (2007). Siblings of adults with schizophrenia: Expectations about future caregiving roles. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.29.

Smith, M. M., Pereira, S. P., Chan, L., Rose, C., & Shafran, R. (2018). Impact of well-being interventions for siblings of children and young people with a chronic physical or mental health condition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(2), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0253-x.

Stuart, H. (2006). Media portrayal of mental illness and its treatments. CNS Drugs, 20(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200620020-00002.

*Tanaka, K. (2008). Siblings of persons with serious mental illness: Resilience and support. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 3(7), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.18848/1833-1882/cgp/v03i07/52663.

*Tanaka, K. (2010). Resilience among siblings of persons with serious mental illness: A cross-national comparison. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 4(12), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.18848/1833-1882/cgp/v04i12/53045.

*Tanaka, K. (2011). Positive experiences of siblings of persons with major mental illness: Self development and support. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 5(11), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.18848/1833-1882/cgp/v05i11/51939.

*Tatay-Manteiga, A., Cauli, O., Tabarés-Seisdedos, R., Michalak, E. E., Kapczinski, F., & Balanzá-Martínez, V. (2019). Subjective neurocognition and quality of life in patients with bipolar disorder and siblings. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 283–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.012.

*Taylor, J. L., Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., & Floyd, F. J. (2008). Siblings of adults with mild intellectual deficits or mental illness: Differential life course outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 905–914. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012603.

*Tschan, T., Lüdtke, J., Schmid, M., & In-Albon, T. (2019). Sibling relationships of female adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury disorder in comparison to a clinical and a nonclinical control group. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0275-2.

*van Dijk, F. A., Schirmbeck, F., Boyette, L.-L., & de Haan, L. (2019). Coping styles mediate the association between negative life events and subjective well-being in patients with non-affective psychotic disorders and their siblings. Psychiatry Research, 272, 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.020.

*van Langenberg, T., Sawyer, S. M., Le Grange, D., & Hughes, E. K. (2016). Psychosocial well-being of siblings of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 24(6), 438–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2469.

Waller, S., Reupert, A., Ward, B., McCormick, F., & Kidd, S. (2019). Family-focused recovery: Perspectives from individuals with a mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12528.

Weissman, M. M., & Siegel, R. (1972). The depressed woman and her rebellious adolescent. Social Casework, 53(9), 563–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/104438947205300906.

*Wolfe, B., Song, J., Greenberg, J. S., & Mailick, M. R. (2014). Ripple effects of developmental disabilities and mental illness on nondisabled adult siblings. Social Science & Medicine, 108, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.021.

*Zauszniewski, J. A., & Bekhet, A. K. (2014). Factors associated with the emotional distress of women family members of adults with serious mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(2), 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2013.11.003.

Zauszniewski, J. A., Bekhet, A. K., & Suresky, M. J. (2010). Indicators of resilience in family members of persons with serious mental illness. Nursing Clinics, 45(4), 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2014.11.009.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sofia Ayala-Rodriguez and Maddie Toman for their assistance with this study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMS and ST: made substantial contributions to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shivers, C.M., Textoris, S. Non-psychopathology Related Outcomes Among Siblings of Individuals with Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 24, 38–64 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00331-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00331-3