Abstract

Background

Global research has found that prevalence rates of child sexual abuse suggest that this is a significant ongoing public health concern. A recent Australian study, for example, revealed that more than three girls and almost one in five boys reported experiencing sexual abuse before the age of 18. Self-reported rates of abuse, however, far exceed official figures, suggesting that large numbers of children who experience sexual abuse do not come to the attention of relevant authorities. Whether and how those children have tried to tell their stories remains unclear.

Objective

The goal of the review was to explore scholarly literature to determine what was known about what enables or constrains children to disclose their experience of sexual abuse.

Method

A systematic scoping review was undertaken to better understand the current state of knowledge in the scholarly literature on child sexual abuse disclosure. Thirty-two scholarly publications were included for analysis following a rigorous process of sourcing articles from five databases and systematically screening them based on transparent inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ecological systems and trauma-informed theoretical paradigms underpinned an inductive thematic analysis of the included manuscripts.

Results

Three multi-dimensional themes were identified from the thirty-two publications. These themes were: factors enabling disclosure are multifaceted; barriers to disclosure include a complex interplay of individual, familial, contextual and cultural issues; and Indigenous victims and survivors, male survivors, and survivors with a minoritised cultural background may face additional barriers to disclosing their experiences of abuse.

Conclusions

The literature suggests that a greater understanding of the barriers to disclosures exists. Further research that supports a deeper understanding of the complex interplay of enablers and the barriers to disclosure across diverse populations is needed. In particular, future research should privilege the voices of victims and survivors of child sexual abuse, mobilising their lived experiences to co-create improved practice and policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of child sexual abuse is a matter of critical interest for researchers, policymakers and practitioners working with children, young people and their families. Worldwide estimates of child sexual abuse (CSA) prevalence are alarming, with an average of 18–20% of females and 8–10% of males reporting experiences of abuse (Pereda et al., 2009). A recent study in the USA, drawing from a sample of 2639 respondents aged 18–28, concluded that the overall prevalence rate of child sexual abuse was 21.7%. For females, this rate was found to be 31.6% and for males, 10.8% (Finkelhor et al., 2024). In Australia, the recently published Australian Child Maltreatment Study collected nationally representative data on rates of abuse and neglect and found that 37.3% of girls and 18.8% of boys had experienced child sexual abuse (Matthews et al., 2023).

Self-reported rates of abuse far exceed official figures, suggesting that large numbers of children who experience sexual abuse do not come to the attention of relevant authorities. As an example of the discrepancy between official statistics versus reports by survivors, offender conviction rates appear to be far lower than reported abuse. One study, for example, found that police did not lay charges in more than half of 659 cases where child sexual abuse was reported to them (Christensen et al., 2016). The two reasons provided were, first, insufficient evidence, and second, aspects of the child’s disclosure, particularly timing and detail, were inadequate for successful prosecution. In another example, a study based on an analysis of administrative data over a fourteen-year timeframe found that only one in five reported child sexual abuse matters proceeded further than the initial investigation phase. In this study, only 12% of reported offences resulted in a conviction, with the authors claiming that their findings were consistent with other studies (Cashmore et al., 2020). Further research to enable a better understanding of “how these (prosecution) decisions are made, over and above the characteristics of the complainant, suspect and type of offence” was recommended (Cashmore et al., 2020, p. 93).

In another example, a meta-analysis that combined estimates of prevalence rates of child sexual abuse across 217 studies, then comparing these rates with official data from sources such as the police and child protection, found that analyses based on self-reports of victims and survivors revealed prevalence rates of up to 30 times greater than official reports (Stoltenborgh et al., 2015), indicating a sizeable gap between self-reported experiences of child sexual abuse by survivors and rates recorded by official authorities. Such a sizable gap suggests that further investigation into research that examines the process of disclosure is much needed, with a focus on what factors enable and constrain children and young people from talking about the abuse that they have experienced.

Child sexual abuse disclosure is theorised as a multifaceted, iterative and contextualised phenomenon that interacts directly or indirectly across a range of ecological variables. Both ecological (Bronfenbrenner., 1979) and trauma theories (Alaggia et al., 2019) consider a child victim within their context by considering the micro, meso and macro implications issues faced by children who have experienced the trauma of child sexual abuse.

In summary, the rationale for this review emerges from the child sexual abuse research literature, which reports very high prevalence rates of abuse, particularly where research participants are offered anonymity as young adults to recall their experiences (Finkelhor et al., 2024; Matthews et al., 2023). Evidence of these high rates of abuse, drawn from research, are not matched by official administrative data published in government reports, with research outcomes reporting on child sexual abuse prevalence up to 30 times greater than official statistics from relevant authorities (Stoltenborgh et al., 2015).

These issues raise serious and urgent questions about how children and young people who have experienced child sexual abuse are listened to, heard and responded to. Children and young people may raise their concerns in attempts to tell, only to meet with barriers that prevent them from feeling supported and safe.

This scoping review aimed to address that gap by examining the literature reporting on disclosures of child sexual abuse by examining the literature reporting on disclosures of child sexual abuse by considering the question: What do we know about what influences or enables children and young people to disclose their experience of child sexual abuse, and what are the barriers to disclosure?

Methods

A Systematic Scoping Review

Using the framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), a systematic scoping review methodology was used to identify the available research literature on the disclosure of child sexual abuse. To clarify the use of the term ‘systematic’ in the context of a scoping review, we adopted a methodologically sound process for searching the literature to scope the current state of knowledge concerning child sexual abuse disclosure (Allagia et al., 2019). The purpose of this review was to map the literature on child sexual abuse disclosure, identify key concepts that hinder or enable disclosure, and highlight gaps in the research. Scoping studies are particularly well-suited for complex topics, as they provide valuable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and future research (McPherson et al., 2019). Mapping the literature involved a five-stage sequential process as follows: developing a research question, systematically identifying potentially relevant studies, screening and selecting relevant studies based on identified inclusion and exclusion criteria, charting the data and collating, summarising and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005, p. 8). This five-stage approach emphasises the importance of building a credible critique when investigating a largely unexplored topic (Munn et al., 2018).

Theoretical Frame

This review took a multi-theoretical approach. Drawing on ecological systems and trauma-informed theoretical paradigms provided a robust framework for understanding the complex barriers to disclosing childhood sexual abuse. By integrating these two theories, we gained an understanding of how, at the individual level, trauma symptoms like shame, guilt, and fear can inhibit disclosure and, additionally, how relational dynamics (microsystems) and broader systemic and societal factors at the exo-system and macrosystem levels, can either support or hinder disclosure. CSA disclosure is often not a one-off event but rather a dynamic process reflecting the trauma of the abuse that may take place over time and can include incidents of retraction where survivors recant their stories (Alaggia et al., 2019). This phenomenon was first theorised by Roland Summit in 1983 and was revisited some decades later as child victims of abuse were reported to ‘accommodate’ abuse to the extent that disclosure was often delayed, conflicted and ultimately retracted (McPherson et al., 2017).

An ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) considers a child contextually by taking into account the “ontogenic, micro-system, exo-system and macro-system” layers that inform childhood experiences (Alaggia, 2010. p. 36). At the micro level, family dynamics can obstruct disclosure due to concerns about not being believed or feelings of loyalty to the abuser. In a different study, Alaggia (2004) points out that although children disclose in many different ways, the closer the familial relationship between the child and the perpetrator, the more difficult disclosure gets. CSA disclosure within a mesosystem encompasses the interactions among different components of the microsystem, such as churches, schools, and neighbourhoods, which can impede the disclosure process. In such interacting systems, the child who discloses can be placed in a liminal place, on the boundaries of the systems that the family is situated in, leading to demands for “compromise” for the “purposes of damage limitation” (Gardner, 2012, p. 102). The exosystem, encompassing broader social systems like social services, can introduce complexities in the disclosure process due to inadequate reporting structures and limited interagency collaboration and resources for investigating child sexual abuse claims and frameworks of support to children who disclose. Gardner (2012, p. 105) refers to these as “anxiety-provoking institutional dilemmas” wherein institutions respond with procedures that contain anxiety rather than through a trauma-informed practice of prioritising safety to reduce the risk of re-traumatisation. The macro-system envelopes the societal norms, laws, and policies, which influence the stigma and cultural taboos around child sexual abuse, potentially affecting how authorities or the adults in a child’s life respond to disclosures of child sexual abuse. Child sexual abuse disclosure is, therefore, a multifaceted, iterative and contextualised phenomenon that interacts directly or indirectly across all these ecological variables (Alaggia et al., 2019).

Five-Phased Approach

Phase One: Developing the Research Question

The following research question framed the systematic scoping review:

What do we know about what influences or enables children and young people to disclose their experience of child sexual abuse, and what are the barriers to disclosure?

Phase Two: The Framework for Systematically Identifying Relevant Studies

A search strategy that aimed to identify peer-reviewed literature was developed. With the support of a research librarian, five electronic databases (InfoRMIT; Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection; APA PsycInfo; Academic Search Premier; ProQuest) were searched using a combination of carefully selected keywords: Child*ren, youth, AND Sexual Abuse OR Sexual Assault AND Disclosure OR Telling OR Sharing AND Barriers OR Hindrance OR Facilitators OR Enablers. Searches were run from 2013 to (July) 2023.

Inclusion criteria The search was restricted to peer-reviewed academic journal articles published in English between 2013 and 2023. Articles focusing on what helped or hindered disclosure that helped to better understand children’s experience of disclosing were included. The inclusion criteria included both articles about children and young people (aged under 18) and articles about adults with lived experience of child sexual abuse who were recalling their experiences of disclosure.

Exclusion criteria Articles were excluded if published before 2013, were not published in a peer-reviewed scholarly journal or did not address the research question. Therefore, articles reporting rates and prevalence, prevention literature (unless it addressed responses to disclosure), diagnostic tools, practice frameworks, and legislative requirements were excluded. Non-English articles were also excluded due to the resources required for translation.

Grey literature was excluded due to quality, reliability, and publication bias concerns. Additionally, challenges in standardising and accessing globally available grey literature made it difficult to ensure evidence-based verification and reproducibility in the review (Mahood, 2014). Only peer-reviewed scholarly articles were included to maintain a systematic and transparent methodology.

Phase Three: Selection of Relevant Studies and Charting of the Data

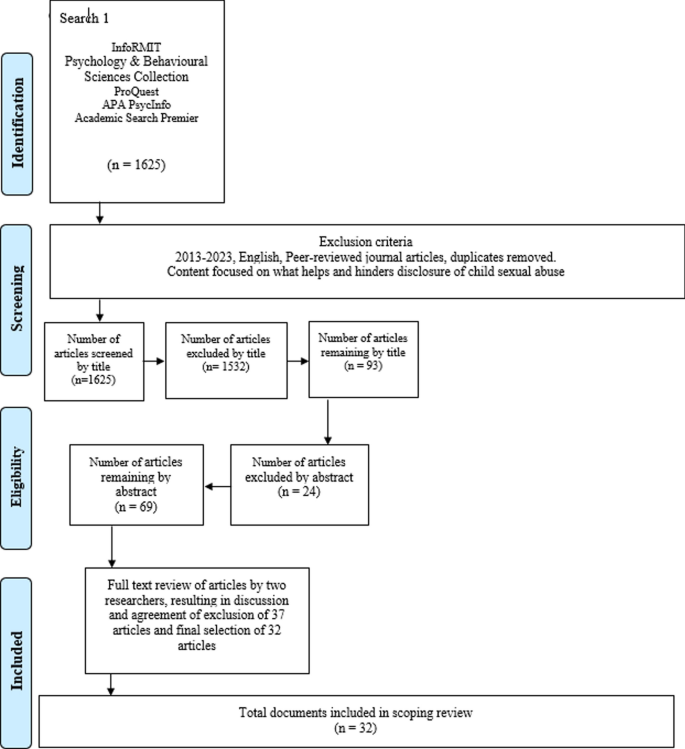

Two researchers applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to all the citations that the search strategy identified, continually reflecting on search strategies and methodological choices at each stage of sifting, charting and sorting (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Initial searches from the databases with the date, source and language criteria applied provided a list of 1625 publications. Titles were screened to ensure broad relevance to the research question and duplicates, with 1532 articles excluded. A review of abstracts was then undertaken for the remaining 93 articles, which led to a further 24 articles being removed.

Full-text articles (n = 69) were retrieved for those articles that had been included. Authors 1 and 4 examined these articles independently to decide if the articles confirmed the inclusion criteria. Author 2 resolved disagreement, resulting in 32 articles being included in the scoping review for inclusion in a thematic analysis. See Fig. 1 for the PRISMA that charts the screening process.

Prisma flow chart. Moher et al. (2009)

Phases 4 and 5: Collating and Analysing the Results

Two researchers (Researchers 1 and 2) reviewed the selected thirty-two articles using Braun and Clarke’s (2021) ‘reflexive thematic analysis’ framework to code and identify emerging themes in the data. The six-phase process includes 1) data familiarisation and writing familiarisation notes; 2) systematic data coding; 3) generating initial themes from coded and collated data; 4) developing and reviewing themes; 5) refining, defining and naming themes; and 6) writing the report (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

As part of phase one, two researchers familiarised themselves with the data using a ‘descriptive-analytical’ method to consistently describe and categorise the key findings relevant to the research question, which formed the basis of the analysis (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Through this process, the researchers mapped the types, locations and key findings of included studies. The final set of 32 publications was collated and presented as a first-level analysis in Table 1. There was no attempt to ‘weigh’ or assess the quality of each study as it is not the purpose of a scoping review, which seeks to present an overview of the material reviewed and, consequently, enable the identification of gaps in existing literature (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005, p. 17).

In phases 2 and 3, the two researchers began reviewing and generating initial codes to “identify and make sense of patterns of meaning across a dataset” (Braun & Clarke, 2021, p. 331) before organising the data thematically using the database program Excel. In phases 4 and 5, the researchers continued to refine and develop themes, encompassing the reflexive qualitative skills of the researchers as analytic resources. The themes were reviewed carefully together and independently by the broader research team to evolve the analysis, an “analytic process involving immersion in the data, reading, reflecting, questioning, imagining, wondering, writing, retreating, returning.” (Braun & Clarke, 2021, p. 332).

Results and Thematic Discussion

The researchers undertook reflexive consultation together and independently to enhance the overall research process. This critical process involved two researchers screening, charting, and collating data. By incorporating this reflexive consultative approach, the researchers ensured they continually reflected on search strategies and methodological choices. This method is not linear but iterative and requires the researchers to engage with each stage of the scoping review reflexively (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

The researchers “made sense of” the data by summarising and interpreting key themes, patterns, and gaps using various frameworks, including a ‘descriptive-analysis’ (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) and ‘reflexive thematic analysis’ (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Preliminary themes and findings were then developed, reported and refined with the broader research team of eight academic researchers and practitioners as subject matter experts to gather their insights, perspectives, and feedback on the preliminary findings. Using a ‘reflexive thematic analysis’ to gather insights, perspectives, and feedback, the researchers enhanced and evolved understandings of child sexual abuse disclosure (Braun & Clarke, 2021). This ‘consultation exercise’ is supported by other researchers who have recognised the value of consultation in enriching and confirming research outcomes (Oliver, 2001).

Following the research team's engagement with the ‘reflexive thematic analysis’ process in the analysis phase, the researchers continued to workshop emergent themes concerning the research question and theoretical framework. Three core themes were identified in the analyses of the 32 articles: (i) Factors enabling disclosure are multifaceted; (ii) Barriers to disclosure include a complex interplay of individual, familial, contextual and cultural issues; (iii) Indigenous victims and survivors, male survivors and survivors with a minoritised cultural background may face additional barriers to disclosing their experiences of abuse.

A summary of the multifaceted barriers and enablers impacting the disclosure of child sexual abuse across various domains is presented below in Table 2.

Within each theme, these factors are discussed below using a social-ecological and reflexive critical theoretical lens.

Factors Enabling Disclosure are Multifaceted

While most research in this review identified barriers to disclosure, some enabling influences were also identified. Disclosure is conceptualised as a process rather than a one-time event (Tat & Ozturk, 2019) that can be affected by personal (individual), interpersonal (mutual or related) and societal (socio-political) factors (Easton et al., 2014; Ullman, 2023). For example, strong personal factors that influence disclosure may be the desire to protect oneself and prevent further abuse, seek support, clarification, and validation, unburden themselves, seek justice, and document the abuse. (Easton et al., 2014; Kasstan, 2022; Lusky-Weisrose et al., 2022; Ullman, 2023). Often, the likelihood of disclosing increases with age (Wallis & Woodworth, 2020).

A trusted and supportive individual, such as a parent, friend, teacher, or counsellor, is a significant interpersonal factor that encourages disclosure. The perception of protectiveness and safety from ‘trusted adults’ is crucial, particularly from mothers, who are often recipients of disclosure (Russell & Higgins, 2023). According to Rakovec-Felser and Vidovič (2016), this is especially important for female child victims of sexual abuse. These researchers found that those with safe and supportive mothers needed about nine months to disclose the abuse, whereas those without such support took approximately 6.9 years to disclose.

Having safe or ‘trusted adults’ also appeared in other research as an enabler of what helps children to ‘tell’ or disclose instances of abuse or CSA-related concerns (Russell & Higgins, 2023). However, an important finding was that disclosures to ‘trusted adults’ primarily occurred when the perpetrator was also an adult. In instances when the perpetrators of CSA were peers, children and young people were less likely to ‘tell’ adults, professionals, or organisations and more likely to ‘tell’ a friend (Russell & Higgins, 2023).

Societal or environmental factors that enable disclosure were linked to ‘memorable life events’ by Allnock (2017). These events are significant moments that can change one's life, which Allnock (2017) calls ‘turning points’, critical moments where survivors feel motivated to disclose their experiences. Turning points could occur accidentally following discussions, conversations, or watching television programs where sexual abuse appeared as a theme, enabling awareness of abusive behaviours and acting as a catalyst to tell (Allnock, 2017). Turning points could also represent the escalation of the offender’s behaviour, survivors becoming aware of other victims, or interventions by police investigations or child protection that may mutually ‘help others’ (Ullman, 2023).

Barriers to Disclosure include a Complex Interplay of Individual, Interpersonal, and Contextual Issues

Reflecting previous research, barriers to disclosure were found to outweigh facilitators of disclosure and tend to be multifaceted (Collin-Vézina et al., 2015; Easton et al., 2014). Barriers involve a complex interplay of individual, familial, contextual, and cultural issues, with age and gender predictive of delayed disclosure for younger children and adolescents (Sivagurunathan et al., 2019).

Multiple studies identified barriers across three broad domains, including personal (internal) barriers, which may include not identifying the experience as sexual abuse, and internal emotions such as shame, self-blame, fear and hopelessness (Collin-Vézina et al., 2015; Devgun et al., 2021; Easton, 2013) or the ‘the normality/ambiguity of the situation’ (Wager, 2015). Young children, particularly preschoolers, often have specific fears and barriers to telling or disclosing even when asked by professionals, as they might not understand the purpose of the interview, the crime they have been victim to, or the consequences of disclosing (Magnusson et al., 2017). Interpersonal barriers, including dynamics with the perpetrator, the relationship between the perpetrator and family, and the fear of consequences or negative self-representation, were found to impact disclosure significantly (Allnock, 2017; Collin-Vézina et al., 2015; Devgun et al., 2021; Easton, 2013; Gemara & Katz, 2023; Gruenfeld et al., 2017; Halvorsen et al., 2020; Wager, 2015).

Social or environmental barriers including limited social networks, a lack of opportunities or access to safe adults to disclose to can also lead to disclosures being downplayed or ignored by those who received them, often reinforcing internalised victim-blaming (Collin-Vézina et al., 2015). These barriers may include social and cultural norms related to sex, misconceptions and stereotypes about child sexual abuse survivors and perpetrators, and a lack of viable services to respond to disclosures (Collin-Vézina et al., 2015; Devgun et al., 2021; Easton, 2013; Mooney, 2021). In fact, according to Easton (2013) and Marmor (2023), many survivors who disclosed their experiences of CSA were unable to receive help despite their disclosures. In some cases, the mishandling of disclosures by law enforcement officers, child protection specialists, medical staff, and mental health professionals also created further barriers to disclosing from a sense of hopelessness (Pacheco et al., 2023; Wager, 2015). Furthermore, a range of context-specific issues were identified in the literature as barriers to disclosure. These included the impact of colonisation, cultural issues, and gender, which are discussed below.

Indigenous Victims and Survivors, Male Survivors and Survivors with a Minoritised Cultural Background May Face Additional Barriers to Disclosing their Experiences of Abuse

Some authors highlighted the ongoing legacy of colonial violence as a personal and structural barrier to the disclosure of child sexual abuse (Braithwaite, 2018; Tolliday, 2016). For Australian First Nations Peoples who were victims and survivors, “child sexual abuse in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is a complex issue that cannot be understood in isolation from the ongoing impacts of colonial invasion, genocide, assimilation, institutionalised racism, and severe socio-economic deprivation. Service responses to child sexual abuse are often experienced as racist, culturally, financially, and/or geographically inaccessible” (Funston, 2013, p. 381). Consistent with these findings, Tolliday (2016) examines historical efforts to address sexual safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children, concluding that these problems cannot be resolved unless the underlying trauma experienced by First Nations Peoples is attended to. An additional barrier for Australian First Nations Peoples may be a level of mistrust in authorities such as police and child protection services, who were found to be involved in the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families (Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission, 1997).

In investigating delayed disclosure, Braithwaite (2018) found that for rural Alaskan Native survivors, the impact of colonisation may be a significant barrier to survivors disclosing abuse. The inability to trust authorities directly results from colonisation and systemic, intergenerational poverty, where disclosing abuse may negatively impact already impoverished families.

Cultural and Racial Issues

In reporting on these issues, it is important not to present child sexual abuse as an inherent racial, religious, or cultural concern. As Taylor and Norma (2013) argue, describing interpersonal barriers for women of culturally or racially diverse backgrounds in Australia to disclose childhood sexual abuse has often been described as “cultural”, but it is more a “familial culture” rather than an aspect of ethnic culture, wherein barriers to reporting sexual abuse are from wanting to protect their family and community from shame, stigma, or loss of dignity in a society where a community as a whole can be racially and culturally vilified for the actions of a few offenders.

In other contexts, researchers found that “familial culture” barriers were experienced by many survivors in other highly racialized contexts. For example, researchers found that in South Africa, the desire for families to preserve the dignity of the family and avoid shame in the community may have inhibited children from wanting to disclose sexual abuse, consequently prioritising the reputation of the family over disclosure (Ramphabana et al., 2019). Likewise, in East Asian communities in Canada, the concern that such a negative incident can ruin the family and the victim’s reputation and damage relationships with other community members can also dissuade disclosure from children and reporting from their families (Roberts et al., 2016). When living within cultural norms that promote self-scrutiny, children feel responsible for their actions and may blame themselves for the abuse or for the impacts of disclosing (Roberts et al., 2016).

Fear of family disruption or breaking up the family, including placement in foster care or the criminal justice system (Allnock, 2017), were also mentioned as barriers to disclosure. This was found particularly in contexts where perpetrators contribute financially to the family or are the breadwinners upon whom the children rely for survival. These fears may be compounded within cultures enshrined within strong patriarchal values, where male dominance over women and children is normalised or socially accepted. This has been witnessed in East Asian communities in Canada, which are greatly influenced by Confucian philosophy and patriarchal lineage and where societal and familial harmony is expected to outweigh personal needs. Taken together, this could contribute significantly to the low reporting rate of Asian child sexual abuse, which is disproportionate to that of Caucasian children in Canada (Roberts et al., 2016). Other factors for low disclosure are linked to fears of condemnation or desire to protect parents, family, and community from reprisal, including, in extreme circumstances, fear of ostracization, death threats, honour killings (Marmor, 2023), physical violence, the risk of being disowned by family or expelled from school, discrimination, isolation from social networks, and emotional abuse within the community (Obong'o et al., 2020). For already vulnerable, minoritised communities, this creates a double layer of vulnerability in broader society.

How a community views sex can also make it difficult for children, families, and communities to identify and disclose child sexual abuse, particularly in sexually conservative, religious-cultural contexts where sex may be taboo, stigmatising, or disrespectful to discuss with children (Ramphabana et al., 2019). In a study from Zimbabwe, stigma and discrimination from being labelled as having sexually transmitted diseases or for losing their virginity were expressed as a fear of disclosure (Obong'o et al., 2020). There are also religious prohibitions against reporting sexual abuse or violence to secular authorities (Marmor, 2023), as this would tarnish the religious image in secular contexts. This suggests that the emphasis on purity culture, silencing of discussions on sexuality, diminished reporting due to fear of the influence of secular values, and reliance on disclosing to religious authority figures rather than professionals act as religious and cultural barriers to reporting child sexual abuse (Lusky-Weisrose et al., 2022). When combined, it reduces survivors’ ability to identify and disclose child sexual abuse alongside institutional barriers and adds layers of possible isolation in cultural contexts that also serve as social protection for minoritised groups.

Gender Issues

The role of gender in child sexual abuse disclosure was identified as a noteworthy barrier. Researchers highlight the difference in disclosure patterns of male child sexual abuse survivors, which tend to be delayed for years or even decades compared to female survivors, and some male survivors were found to have lower rates of ever disclosing the abuse (Easton, 2013; Easton et al., 2014). Like many survivors of child sexual abuse, male survivors feared not being believed, justifiably, as historically there was a lack of awareness of the existence of male child sexual abuse, despite researchers finding that approximately 15% of adult men report being sexually abused during childhood (Easton et al., 2014). The mass media coverage of institutional abuse scandals, such as those at the Catholic Church, Boy Scouts of America, and Penn State University, have now raised public awareness of the sexual abuse of boys and how the impacts of child sexual abuse, such as deep-seated rage, shame, spiritual distress, and stigma (Easton, 2013) have influenced delayed or non-disclosure.

Gendered societal norms also strongly influence individual, group, and societal ideas and behaviours towards male sexual abuse (Sivagurunathan et al., 2019). These include, notably, ideas of male gender identity, masculinity, and masculine norms such as winning, emotional control, homophobia, and self-reliance, including negative attitudes towards victimhood and help-seeking. Additionally, as boys are often sexually abused by other males, many survivors fear the stigma of being labelled homosexual (Easton, 2013; Easton et al., 2014). Some survivors who self-identified as gay or bisexual also feared that others would use their abuse to explain their sexual orientation, saying it “made me gay” (Easton, 2013; Easton et al., 2014). Other survivors also questioned their sexual orientation due to their abuse experiences, blamed themselves, or feared being seen by others as having unconsciously invited the abuse (Sivagurunathan et al., 2019).

External barriers to disclosure were also identified regarding child protection workers, law enforcement, and clinicians (Easton, 2013), as well as religious institutions, such as churches and mosques, who were also found to have obstructed the identification and treatment of child sexual abuse in males due to societal attitudes about sex and the stigma of child sexual abuse. Additionally, there is a double standard when it comes to how sexual abuse among men is framed in mainstream media in a society that tends to glorify the sexual abuse of male children as a sexual initiation or sexual prowess if the perpetrator is an older woman. These double standards may, in turn, result in the further reluctance of male child sexual abuse survivors to disclose such experiences (Sivagurunathan et al., 2019), which is part of the reason why the helpfulness of responses to child sexual abuse disclosure across a male survivor’s lifespan is mixed (Easton, 2013). Combined, they all link to larger societal issues around gendered social expectations and how they impact child sexual abuse disclosure. If hegemonic masculinity and the conforming of traditional gendered roles lead to delayed disclosure or not disclosing at all for male survivors, a question arises concerning the child sexual abuse experiences of transgender and gender-diverse people, who are disproportionately affected by prejudice-motivated discrimination and violence.

Implications for Policy, Practice and Further Research

Thirty-two manuscripts were reviewed to respond to the question: What is known about what influences or enables children and young people to disclose their experience of child sexual abuse, and what are the barriers to disclosure?

This review found that a significant enabler for disclosure is the presence of a safe relationship. This finding is consistent with emerging knowledge about the impact of trauma, which suggests that children may first choose to disclose to a friend or person they trust. Another clear finding in the literature is that disclosure should not be conceptualised as a single event at a point in time. Disclosure is seen as multifaceted, contextual and likely to be iterative, taking place over time. This raises critical questions about the extent to which legislative, policy and practice frameworks are sensitised to this finding.

These findings should contribute to the design of policies that support practices enabling children to experience safe spaces and relationships within which they may feel able to disclose, in their own time, the abuse that they have experienced. Services designed to engage and support all children and young people, including schools, sports and recreation facilities, should give attention to various strategies to promote a sense of safety for their child participants. These services should be accompanied by clearly articulated policies to support children and young people through the process of disclosure. In addition, services designed to respond to child victims, such as statutory child protection and police, must be designed with children in mind. In practice, adult-centric forensic models of interviews conducted by police and child protection may be premised on a single contact with the child. This approach may not match the child’s need to reveal details of their experience over time in what we know to be an often iterative process. All children’s services should become familiar with the behavioural indicators that some children, particularly younger children, may demonstrate rather than using words to disclose.

The notable research gaps are of importance for future research. For example, critical questions are raised concerning the lack of studies on diverse cohorts, including LGBTQIA + survivors, Indigenous survivors or survivors living with a disability. Whilst the prevailing research does address the facilitators of disclosure to an extent, the volume of literature reporting on the barriers to disclosure is greater. A more in-depth understanding by policymakers, practitioners and researchers of some of the obstacles, including broader social and sociocultural barriers, is needed.

Further research to hear from a diverse cohort of survivors to explore their experiences of disclosing child sexual abuse is urgently needed. Overall, this review highlights the need to advance the understanding of the processes of child sexual abuse across diverse cohorts and contexts to improve service systems’ capacity to listen, hear, and respond appropriately to children and young people.

Overall, this review highlights the need to advance the understanding of the processes of child sexual abuse across diverse cohorts and contexts to improve service systems’ capacity to listen, hear, and respond appropriately to children and young people.

Limitations of the Study

Several methodological limitations apply to this analysis. This review has not identified all relevant literature due to the scope of databases searched and the likelihood that not all contemporary search terms were utilised, which might limit the comprehensiveness of the review. The research question sought information about disclosures of child sexual abuse; however, many practice responses to disclosure are likely unpublished in scholarly journals. As grey literature was excluded, potentially valuable insights from reports, theses, conference papers, and other non-peer-reviewed sources were not considered. This limitation is compounded by the inherent difficulty in drawing generalisable conclusions from scoping reviews, which encompass a variety of methodologies, populations, and contexts.

Another limitation is that only articles published in English were included, potentially resulting in the exclusion of crucial studies published in other languages. Additionally, the reliance on peer-reviewed journals may introduce publication bias, as studies with significant or positive results from the UK or North America are more likely to be published. There is also the possibility of subjective bias, as the identification and interpretation of themes depend on the researchers' perspectives.

Furthermore, as it is not within the remit of a scoping review to assess the quality of included studies, findings from lower-quality studies are considered alongside those from higher-quality studies without differentiation. However, the choice to include and conduct scholarly literature that undergoes independent double-blind peer review was made to reduce quality and publication bias risks.

Conclusion

Rather than simply being a one-off event, the disclosure of child sexual abuse is often a complex and ongoing process (Alaggia et al., 2019). More is known about barriers than enablers to disclosure, with barriers dominating the published literature sourced in this review. It is evident that, for children and young people, talking about the abuse that they have endured can be overwhelmingly challenging for them across personal, interpersonal and broader levels.

When children and young people begin to disclose, this review raised critical questions about how service systems respond to initial disclosure, particularly the extent to which policies and systems are designed to reflect children’s best interests.

Adults noticing when children and young people are distressed helps victims and survivors to disclose, as does creating trusting relationships to provide opportunities to tell their stories (Russell et al., 2023). To whom children elect to disclose is an important question, with recent research suggesting that when children and young people feel unsafe, they are more likely to tell a friend than an adult (Russell et al., 2023). Research is urgently required to develop a more robust understanding of the enablers of disclosure across diverse populations. This research needs to privilege the voices of victims and survivors with lived and living experiences of child sexual abuse.

References

*Denotes a reference included in this scoping review

Alaggia, R. (2004). Many ways of telling: Expanding conceptualizations of child sexual abuse disclosure. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(11), 1213–1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.016

Alaggia, R. (2010). An ecological analysis of child sexual abuse disclosure: Considerations for child and adolescent mental health. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(1), 32–39.

Alaggia, R., Collin-Vézina, D., & Lateef, R. (2019). Facilitators and barriers to child sexual abuse (CSA) disclosures: A research update (2000–2016). Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(2), 260–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017697312

*Allnock, D. S. (2017). Memorable life events and disclosure of child sexual abuse: Possibilities and challenges across diverse contexts. Families, Relationships and Societies, 6(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674317X14866455118142

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

*Braithwaite, J. (2018). Colonized silence: Confronting the colonial link in rural Alaska native survivors’ non-disclosure of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(6), 589–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1491914

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Reality and research in the ecology of human development. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 119(6), 439–469.

Cashmore, J., Taylor, A., & Parkinson, P. (2020). Fourteen-year trends in the criminal justice response to child sexual abuse reports in New South Wales. Child Maltreatment, 25(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559519853042

Christensen, L. S., Sharman, S. J., & Powell, M. B. (2016). Identifying the characteristics of child sexual abuse cases associated with the child or child’s parents withdrawing the complaint. Child Abuse & Neglect, 57, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.05.004

*Collin-Vézina, D., De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M., Palmer, A. M., & Milne, L. (2015). A preliminary mapping of individual, relational, and social factors that impede disclosure of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 43, 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.010

*Devgun, M., Roopesh, B. N., & Seshadri, S. (2021). Breaking the silence: Development of a qualitative measure for inquiry of child sexual abuse (CSA) awareness and perceived barriers to CSA disclosure. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 57, 102558–102558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102558

*Easton, S. D. (2013). Disclosure of child sexual abuse among adult male survivors. Clinical Social Work Journal, 41(4), 344–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-012-0420-3

*Easton, S. D., Saltzman, L. Y., & Willis, D. G. (2014). “Would you tell under circumstances like that?”: Barriers to disclosure of child sexual abuse for men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034223

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Colburn, D. (2024). The prevalence of child sexual abuse with online sexual abuse added. Child Abuse & Neglect, 149, 106634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106634

*Funston, L. (2013). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander worldviews and cultural safety transforming sexual assault service provision for children and young people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(9), 3818–3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10093818

Gardner, F. (2012). Defensive processes and deception: An analysis of the response of the institutional church to disclosures of child sexual abuse. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 28(1), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0118.2011.01255.x

Gemara, N., & Katz, C. (2023). “It was really hard for me to tell”: The gap between the child’s difficulty in disclosing sexual abuse, and their perception of the disclosure recipient’s response. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 2068–2091. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221099949

*Gruenfeld, E., Willis, D. G., & Easton, S. D. (2017). “A very steep climb”: Therapists’ perspectives on barriers to disclosure of child sexual abuse experiences for men. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(6), 731–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2017.1332704

*Halvorsen, J. E., Tvedt Solberg, E., & Hjelen Stige, S. (2020). “To say it out loud is to kill your own childhood: an exploration of the first person perspective of barriers to disclosing child sexual abuse. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104999

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. (1997). Bringing them home: Inquiry into the separation of indigenous children from their families. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

*Kasstan, B. (2022). everyone’s accountable? Peer sexual abuse in religious schools, digital revelations, and denominational contests over protection. Religions (Basel), 13(6), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060556

*Lusky-Weisrose, E., Fleishman, T., & Tener, D. (2022). “A little bit of light dispels a lot of darkness”: online disclosure of child sexual abuse by authority figures in the Ultraorthodox Jewish community in Israel. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37, NP17758–NP17783. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211028370

*Magnusson, M., Ernberg, E., & Landström, S. (2017). Preschoolers’ disclosures of child sexual abuse: Examining corroborated cases from Swedish courts. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.05.018

Mahood, Q., Eerd, D. V., & Irvin, E. (2014). Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1106

*Marmor, A. (2023). “I never said anything. I didn’t tell anyone. What would I tell?” Adults’ perspectives on disclosing childhood sibling sexual behavior and abuse in the Orthodox Jewish communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38, 10839–10864. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605231175906

Mathews, B., Pacella, R., Scott, J. G., Finkelhor, D., Meinck, F., Higgins, D. J., Erskine, H. E., Thomas, H. J., Lawrence, D. M., Haslam, D. M., Malacova, E., & Dunne, M. P. (2023). The prevalence of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from a national survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 218(S6), S13–S18. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51873

McPherson, L., Gatwiri, K., Cameron, N., & Parmenter, N. (2019). The evidence base for therapeutic group care: a systematic scoping review. Centre for excellence in therapeutic care. https://www.cetc.org.au/the-evidence-base-for-therapeutic-group-care-a-systematic-scoping-review-research-brief/

McPherson, L., Long, M., Nicholson, M., Cameron, N., Atkins, P., & Morris, M. E. (2017). Secrecy surrounding the physical abuse of child athletes in Australia. Australian Social Work, 70(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1142589

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement: e1000097. PLoS Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

*Mooney, J. (2021). How adults tell: a study of adults’ experiences of disclosure to child protection social work services. Child Abuse Review, 30(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2677

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143–143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

*Obong’o, C. O., Patel, S. N., Cain, M., Kasese, C., Mupambireyi, Z., Bangani, Z., Pichon, L. C., & Miller, K. S. (2020). Suffering whether you tell or don’t tell: Perceived re-victimization as a barrier to disclosing child sexual abuse in Zimbabwe. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 29(8), 944–964. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2020.1832176

Oliver, S. (2001). Marking research more useful: integrating different perspectives and different methods. In S. Oliver & G. Peersman (Eds.), Using research for effective health promotion (pp. 167–179). Open University Press.

*Pacheco, E. L. M., Buenaventura, A. E., & Miles, G. M. (2023). “She was willing to send me there”: Intrafamilial child sexual abuse, exploitation and trafficking of boys. Child Abuse & Neglect, 142(Pt 2), 105849–105849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105849

Pereda, N., Guilera, G., Forns, M., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2009). The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse: A continuation of Finkelhor (1994). Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(6), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.007

*Rakovec-Felser, Z., & Vidovič, L. (2016). Maternal perceptions of and responses to child sexual abuse. Zdravstveno Varstvo, 55(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjph-2016-0017

*Ramphabana, L. B., Rapholo, S. F., & Makhubele, J. C. (2019). The influence of socio-cultural practices amongst Vhavenda towards the disclosure of child sexual abuse: Implications for practice. Gender & Behaviour, 17(4), 13948–13961.

*Roberts, K. P., Qi, H., & Zhang, H. H. (2016). Challenges facing East Asian immigrant children in sexual abuse cases. Canadian Psychology Psychologie = Canadienne, 57(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000066

*Romano, E., Moorman, J., Ressel, M., & Lyons, J. (2019). Men with childhood sexual abuse histories: Disclosure experiences and links with mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.12.010

*Rothman, E. F., Bazzi, A. R., & Bair-Merritt, M. (2015). “I’ll do whatever as long as you keep telling me that I’m important”: a case study illustrating the link between adolescent dating violence and sex trafficking victimization. The Journal of Applied Research on Children. https://doi.org/10.58464/2155-5834.1238

*Russell, D. H., & Higgins, D. J. (2023). Friends and safeguarding: Young people’s views about safety and to whom they would share safety concerns. Child Abuse Review, 32(3), e2825. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2825

*Sivagurunathan, M., Orchard, T., MacDermid, J. C., & Evans, M. (2019). Barriers and facilitators affecting self-disclosure among male survivors of child sexual abuse: The service providers’ perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 455–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.015

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R. A., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2353

Summit, R. C. (1983). The child sexual abuse accommodation syndrome. Child Abuse & Neglect, 7(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(83)90070-4

*Swain, S. (2015). Giving voice to narratives of institutional sex abuse. The Australian Feminist Law Journal, 41(2), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.2015.1077554

*Tat, M. C., & Ozturk, A. (2019). Ecological system model approach to self-disclosure process in child sexual abuse. Current Approaches to Psychiatry, 11(3), 363–386. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.455511

*Taylor, S. C., & Norma, C. (2013). The ties that bind: Family barriers for adult women seeking to report childhood sexual assault in Australia. Women’s Studies International Forum, 37, 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2012.11.004

*Tolliday, D. (2016). “Until we talk about everything, everything we talk about is just whistling into the wind”: An interview with Pam Greer and Sigrid (‘Sig’) Herring. Sexual Abuse in Australia and New Zealand, 7(1), 70–80.

*Ullman, S. E. (2023). Facilitators of sexual assault disclosure: A dyadic study of female survivors and their informal supports. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 32(5), 615–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2023.2217812

*Wager, N. M. (2015). Understanding children’s non-disclosure of child sexual assault: Implications for assisting parents and teachers to become effective guardians. Safer Communities, 14(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/SC-03-2015-0009

*Wallis, C. R. D., & Woodworth, M. D. (2020). Child sexual abuse: An examination of individual and abuse characteristics that may impact delays of disclosure. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107, 104604–104604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104604

*Weiss, K. G. (2013). “You just don’t report that kind of stuff”: Investigating teens’ ambivalence toward peer-perpetrated, unwanted sexual incidents. Violence and Victims, 28(2), 288–302. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.11-061

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Centre for Action on Child Sexual Abuse. The findings and views reported within are those of the authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McPherson, L., Gatwiri, K., Graham, A. et al. What Helps Children and Young People to Disclose their Experience of Sexual Abuse and What Gets in the Way? A Systematic Scoping Review. Child Youth Care Forum (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-024-09825-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-024-09825-5