Abstract

Many intervention programs, including physical activity programs, have been developed to deal with youth involvement in delinquency. The current study explored whether youth participation in sport and physical activity programs reduces their involvement in delinquent behaviors. It examined the interaction effects of the features of the sports program with participation in the sports program. The sample consisted of 126 Israeli adolescents aged 13–18 (M = 15.68, SD = 1.32) who completed questionnaires about involvement in delinquency at the beginning of their sports program and again 6 months later. We found significant reductions in adolescents’ involvement in all the delinquent acts explored: crimes against a person; crimes against property, and public disorder crimes. However, no interaction effects were found between program features (sport type; program intensity; training and supervision in the program; and interaction with community services) and participation in the sports program. The findings highlight the importance of including sports programs in the interventions provided for at-risk youth and call for further investigation of the factors that may increase the benefits provided by participation in physical activity programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Youth involvement in violence and delinquency is a significant problem and a major public concern (Armour, Sandford, & Duncombe, 2013; Slavin et al., 2013). Youth involvement in delinquency can lead to many psychological difficulties (McMahon & Washburn, 2003) and is associated with negative outcomes, such as internalizing symptoms, lower aspiration to pursue a college education (Foshee et al., 2016), interpersonal difficulties, and peer rejection (Coie, Lochman, Terry, & Hyman, 1992). In addition, youth delinquency has many societal and financial costs (Amodei & Scott, 2002; Limbos et al., 2007), both for individual victims and for society at large. As a result, many intervention and prevention programs have been developed to help decrease youth involvement in antisocial behaviors (Andrews & Andrews, 2003; Sandford, Duncombe, & Armour, 2008).

One of the intervention tools used to help youth at risk for involvement in delinquency is having them participate in sport programs (Sandford, Armour, & Duncombe, 2007; Spruit, van der Put, van Vugt, & Stams, 2017). The development of this intervention was based on the fundamental belief and research findings that demonstrated the potential of sports programs to instill positive attitudes, traits, and values in young people and re-engage them in education and society (Sandford, Armour, & Warmington, 2006).

In particular, it has been argued that engagement in physical activities, together with obvious physiological benefits, has a positive impact on youth development (Sandford et al., 2008). It has been found to improve individuals’ confidence and sense of self-worth (Nichols, 1997). It has also been found to help promote skills in problem solving, to teach youth how to work cooperatively with peers as a member of a team (Carmichael, 2008), to promote the capacity for collaborative work (Gass & Priest, 1997), and to facilitate positive socio-moral development (Danish, 2002; Larson & Silverman, 2005). Studies have shown that engaging in sports can increase feelings of success, euphoria, and competency (Biddle, 2006; Hans, 2000; Sandford et al., 2008).

These improvements can directly impact behavioral risk factors and, thus, sport may be a useful intervention strategy in reducing antisocial behavior (Makkai, Morris, Sallybanks, & Willis, 2003). However, the findings of previous research addressing the relationship between sports and antisocial behavior has left it unclear whether sports participation acts as a preventative measure or as a risk factor for delinquent behavior.

On the one hand, the positive effects of participation in sport and physical activity programs, including decreased levels of antisocial and delinquent behavior, have been extensively supported in previous research (Andrews & Andrews, 2003; Armour et al., 2013; Morris, Sallybanks, Willis, & Makkai, 2004; Rhea & Lantz, 2004). For example, a study of 10,992 Icelandic adolescents found that adolescents who participated in organized sports programs were less likely to use alcohol than those who did not participate. Similarly, Rhea and Lantz (2004) found that higher sports participation was associated with less involvement in assault among male youth (see also Armour et al., 2013; Begg, Langley, Moffitt, & Marshall, 1996). Although there has been little research on the contribution of sport and physical activity programs to the development specifically of at-risk youth, findings consistent with the studies cited above have been reported, showing a positive association between sport participation and decreased levels of involvement in anti-social behaviors (Andrews & Andrews, 2003; McKenney, 2001; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Morris et al., 2004). For example, in a longitudinal study of approximately 7000 disaffected students from the UK, Sandford et al. (2008) found that sport and physical activity had a positive impact on participants’ behavior and attendance disaffection. They found significant improvements in pupils’ outcomes after involvement in the activity.

On the other hand, some research has found a negative relationship between sports participation and delinquent behavior among young people (Endresen & Olweus, 2005; Kreager, 2007; Langbein & Bess, 2002). For instance, Burton and Marshall (2005) found that youth participation in sports was positively related with aggressive behaviors. They argued that the competitive nature of some sports might act to encourage antisocial behavior (Spruit, Van Vugt, van der Put, van der Stouwe, & Stams, 2016). A similar finding was reported by Farineau and McWey (2011) in their study of 117 at-risk youth. They found a positive association between involvement in extracurricular activities and delinquency among adolescents in out-of-home placements.

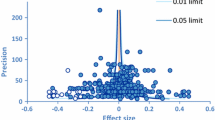

Contrary to these two trends indicating an association between sports participation and youth involvement in delinquency, some researchers have argued that sports participation is not associated with delinquency at all. In their meta-analysis of 51 studies, Spruit et al. (2016) found no significant association between sports participation and juvenile delinquency (see also Davis & Menard, 2013). This inconsistency among findings calls for further examination of the association between sports participation and youth involvement in delinquency.

The key aspects of sport and physical activity that are assumed to be behind their positive effects on youth are their ability to reduce boredom and decrease the amount of unsupervised leisure time (see, for example, Makkai et al., 2003). In the current study, we rely on the concepts of Hirschi’s social bond theory, as used by sport scholars to explain the expected contribution of participation in sport activities on youth developmental outcomes (Crosnoe, 2001; Kreager, 2007; Spruit et al., 2016). According to Hirschi’s theory (1969), participation in positive activities might increase adolescents’ bonds to conventional society and, as a result, decrease their involvement in delinquency. Kreager (2007) used the four elements of the theory—involvement, commitment, attachment, and beliefs—to explain how sport participation might result in positive youth developmental outcomes.

Regarding involvement, the theory assumes that a person who is busy participating in conventional activities, such as sport, will have less time available to commit antisocial behaviors, thus decreasing the opportunity for delinquency. With respect to the other three elements of the theory, Kreager (2007) argued that sport participation increases youth commitment to conventional activities, strengthens their attachment to significant others, such as teammates and coaches, and strengthens their beliefs in society’s values, because similar values, norms, and rules are practiced in the sports context (see also Spruit et al., 2016).

In addition to the direct effects of participation in sport and physical activity on adolescents’ behavior, studies have explored whether there are particular components or features of physical activity programs that may increase the effects of participation in sport on youth behaviors (Sandford et al., 2008; Spruit et al., 2017). We haven’t found studies exploring this interaction effect in previous works. Most studies that refer to sport type ask whether sport type makes a difference and whether the effect of participation in sports varies by sport type. Kreager (2007) found that high contact team and individual sports, such as football and wrestling, were significantly positively associated with involvement in violence. Kreager (2007) also found a negative association between individual noncontact sports, such as tennis, and involvement in violence, and an insignificant association between low contact team sports, such as basketball, and involvement in violence. However, whereas Morris et al. (2004) found a significant association between participation in sports in general and lower levels of involvement in delinquent behavior, they found an insignificant association between sport type (team, individual, high contact, and low or no contact) and youth delinquency.

Other components of physical activity programs have been studied, including the integration of community support services into the programs and the intensity and frequency of participation. For example, Morris et al. (2004) explored whether the integration of community support services into the design of sport programs had an effect on youth behaviors. It was assumed that this element might increase the benefits associated with participation in sports programs by ensuring the continuity of help and support beyond the sports activity (Morris et al., 2004). Also, staff supervision and training to work with young people on program activities, which emphasizes the need for qualification to work with the program’s population, was found to have a positive effect on youth behaviors (Armour et al., 2013; Morris et al., 2004). In addition, the intensity and frequency of participation affected the results of participation, not only on aspects of health and fitness, but also on the development of social skills, attitudes, and values (Bailey, 2006). As Hirschi’s social bond theory suggests, the more the youth spend time in these conventional activities the less time they have to be involved in antisocial behaviors.

Despite their contributions, previous studies of the advantages of sport participation on the behavioral outcomes of at-risk youth have limitations that are worth noting. For one, the definition of sport participation in these studies is often very general. For example, Fredricks and Eccles (2006) assessed involvement in organized sport with two yes-or-no questions, and did not examine the effect of the sport type. Other studies focus on specific of at-risk youth but pay little attention to the program features or components. For example, Farineau and McWey (2011) focused on youth in out-of-home placements and only examined the frequency of the activity as a program feature. Sandford et al. (2008) conducted one of the largest studies exploring the contribution of sports participation on the outcomes of at-risk youth. They examined several sports projects that included a range of sport activities, but they only included limited behavioral outcomes and did not investigate the interaction between youth participation in sports program and program features or components.

The current study expands on previous studies by exploring at-risk youth who participate in several sport and physical activity programs (horseback riding, football/soccer, basketball, tennis, and martial arts) and their involvement in various types of delinquency (crimes against a person, property crime, and public disorder crime). In addition, we explored the interaction effects of participation in sports programs and a wide range of program components or features (type of sport, intensity, team/staff training, and interaction with community services) on youth involvement in delinquency.

At-Risk Youth and Antisocial Behavior in Israel

In Israel, about 30% of the child population (about 240,000 children) are considered to be at risk (Zionit & Kosher, 2013). They live in extreme poverty and are exposed to violence, neglect, and many other social and economic difficulties (Schmid, 2007).

Studies have shown that youth at risk are more likely than youth not at risk to be involved in violence and other antisocial behaviors. For instance, a study of 115 at-risk boys aged 15–19 in Israel found that they were highly involved in antisocial behaviors: 87.8% had been involved in the previous year in at least one activity defined as an offense against public order; 71.3% had been involved in at least one offense against a person; and 65.2% reported that they had committed at least one property offense. These findings are similar to the results of other surveys performed in Israel and worldwide that report relatively high levels of involvement in different types of delinquency among male adolescents, especially in offenses against public order, people, property, and in drug use (Khoury-Kassabri, Khoury, & Ali, 2015; Morris et al., 2004).

Because of extensive research describing the many advantages of sport program participation, many social workers, counselors, and other professionals who work with at-risk youth are willing to refer young people in their treatment to sports programs aimed at at-risk youth (Kravets-Fenner, Khoury-Kassabri, Aszenstadt, & Amedi, 2013). These programs are perceived as an opportunity to engage young people in conventional activities, and sport is perceived as a tool that may help promote positive health, emotional, and behavioral development.

Methodology

Sample

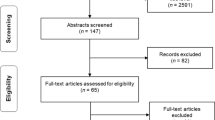

Using the convenience sampling method, 160 Jewish male adolescents from Israel, aged 13–18 (M = 15.68, SD = 1.32) who participated in one of five sports programs for youth at risk (horseback riding, football/soccer, basketball, tennis, or martial arts) completed a questionnaire at the beginning of their participation in the sports program. Six months later the participants were invited to fill out a follow-up questionnaire. Among the participants, 42.9% indicated that their parents were divorced or separated. Almost half of the participants reported their family economic status to be low or very low; 27% indicated their economic status to be medium–low. Of the 160 youth who participated in the baseline measurement, 126 participated in the follow-up measurement. A t-test analysis found no significant differences in the levels of involvement in delinquency of youth who dropped out of the study and those who remained. Therefore, we assumed that the dropout in the study was random.

Measurements

Delinquent Behavior

Delinquent behaviors were examined using the self-report delinquency scale originally developed by Elliott and Ageton (1980). The original reliability of this scale was between 0.80 and 0.99. For the present study, 22 items that had been used in previous studies of Jewish youth (Kravets-Fenner et al., 2013; Statland-Vaintraub, Khoury-Kassabri, Aszenstadt, & Amedi, 2012) were used to measure three types of crime: crimes against a person; crimes against property; and public disorder crimes. Responses were on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = 3–6 times, 4 = 7–10 times, 5 = more than 10 times). Crimes against a person (α = .70) included four items, such as “Have you ever attacked someone with the idea of seriously hurting or killing her/him?” Property crime (α = .83) included 13 items, such as “You have stolen or tried to steal something that was worth more than 100 NIS.” Public disorder crimes (α = .83) included five items, such as “You have been drunk in a public place.” All scales were based on the means of their items.

Program Features/Components

We used an adapted version of the questionnaire used in Morris et al.’s (2004) survey of Australian sport and organized physical activity programs, which was designed to measure the features of the programs in their study. For our study, the questionnaire was translated into Hebrew and back translated. The questionnaire was filled out by the program coordinator to include sport type (horseback riding, football/soccer, basketball, tennis, and martial arts) and program intensity (1 = once a week to 3 = more than twice a week). Based on the analysis of the responses of the sport program coordinators to a series of open- and closed-ended questions, two additional program features were included in the questionnaire: training and supervision (1 = no training and supervision in the program; 2 = training and supervision to some extent; 3 = training and supervision to a large extent); and interaction with community services (1 = no interaction with community services; 2 = basic interaction with community services; 3 = strong interaction with community services).

Study Procedure

After the study was approved by the Hebrew University Internal Review Board and the managers of each program, letters were sent to the parents of the boys who participated in these programs. Youth whose parents did not send a refusal form were asked to participate in the study. Youth were also given the option to decline to participate. Those who agreed to participate were provided an explanation of the study and its goals. Participants filled out an online anonymous questionnaire on laptops provided by the researcher at the first meeting of the sport program. Six months later they were asked to fill out a follow-up questionnaire the same way.

Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis of the programs’ features was explored (Table 1). A repeated measures analysis of variance was then conducted to test the following items: (1) individual changes in each of the antisocial and delinquent behaviors (see Table 2); (2) the main effects of each program component on level of delinquency, and (3) the interaction effects of each program component and change in youth level of involvement in delinquency over time (see Table 3).

Results

Program Components/Features

The results in Table 1 show that almost half of the boys participated in soccer programs (46.3%); about a fifth participated in horseback riding (21.9%); 14.4% participated in martial arts; and less than 10% participated in tennis and basketball. Most of the participants attended the sports program twice a week (63.8%); 31.9% attended at least three times a week. Program coordinators reported that more than a third of the programs (36.3%) had no supervision and training for the staff. In 17.5% of the programs there was extensive training and supervision. Most of the programs had basic (54.4%) to no (36.3%) interaction with community services.

Adolescents’ Involvement in Delinquency, Pre-program and 6 Months Later

Table 2 shows the mean scores of the delinquency measures. Using a repeated measures analysis, we explored whether juveniles’ reports of involvement in delinquency changed significantly 6 months after starting the sport program. The results showed a significant decrease in juveniles’ involvement in all the delinquent acts included in this study: crimes against a person [F (1,125) = 179.53, P < .001, CI 1.61–1.79, Eta2 = .590; M = 1.97 vs. M = 1.43]; crimes against property [F (1,125) = 88.41, P < .001, CI 1.30–1.42, Eta2 = .414; M = 1.52 vs. M = 1.20]; and public disorder crimes [F (1,125) = 96.12, P < .001, CI 2.28–2.55, Eta2 = .590; M = 2.70 vs. M = 2.13]. These findings show that youth participation in sports programs is significantly and negatively associated with youth involvement in delinquency.

Interaction Between Participation and Program Components

We investigated whether the effects of participation on level of involvement in delinquency were associated with the programs’ components (sport type; program intensity; training and supervision in the program; and interaction with community services). We explored also, whether under certain conditions the association between participating in sport programs and levels of antisocial behavior might be stronger or weaker.

As shown in Table 3, no interaction effects were found between any of the program components and participation in the sport program. These results emphasize that youth participation in the sports program, compared to other factors explored in the study, has the strongest associated with levels of youth involvement in delinquency.

Table 3 also shows that there were almost no significant associations between program components and level of youth involvement in delinquency. The one exception was the association between public disorder crime and both program level of training/supervision [F (2,123) = 3.13, P < .05] and interaction with community services [F (2,123) = 3.24, P < .05]. Post hoc analysis revealed that youth who are in sports programs with trained and supervised staff (M = 2.18, SD = 0.15) and in programs that interact with community services (M = 2.09, SD = 0.20) were significantly less involved in public disorder crime than those in programs with no training and supervision (M = 2.63, SD = 0.11) and no interaction with community services (M = 2.62, SD = 0.11).

Discussion

Participation in sports programs contributes positively to the physical and mental health of children and adolescents (Andrews & Andrews, 2003). We aimed to expand the literature in the field by focusing on youth at risk and exploring whether participation in sports programs affects their level of involvement in crimes against a person, property crime, and public disorder crime. In addition, we explored whether specific components or features of the program (sport type; program intensity; staff training and supervision; and interaction with community services) would make a difference in the effects that participation in physical activity programs had on youth. The main finding of the study was that participation in sport programs was associated with lower levels of delinquency among at-risk youth. This association was not affected by various program features and components.

Participation in Sport: Main and Interaction Effects on Delinquent Behaviors

The results of our study are consistent with previous findings that showed that participation in sports programs significantly decreases youth involvement in delinquency (Armour et al., 2013; Carmichael, 2008; Danish, Taylor, & Fazio, 2003; Donaldson & Ronan, 2006; Poinsett, 1996; Smith & Smoll, 1991). We found that youth at risk who participated in sports programs reported significantly lower levels of involvement in crimes against a person, property crimes, and public disorder crimes. These findings are in line with studies that highlight the role of sport as a tool to instill moral education, positive attitudes, traits, and values, and to improve physical and mental health (Armour et al., 2013; Eley & Kirk, 2002; Russell, 2005). These improvements in youths’ emotional and cognitive outcomes might also have an impact on behavioral risk factors, which in turn decreases youth involvement in delinquency (Morris et al., 2004).

The four components of Hirschi’s social bond theory—involvement, commitment, attachment, and beliefs—can be seen to offer an interpretation of the relationship between sport and delinquency reported in this study. First, regarding involvement, each activity a person chooses to do takes up a certain amount of time, giving him or her less time to do something else. According to this theory, when youth are involved in conventional activities, they have less time to engage in deviant behavior (Hirschi, 1969). Second, involvement in conventional activities helps youth develop a sense of commitment. According to this aspect of the theory, youth refrain from involvement in crime in order not to jeopardize their opportunity to participate in their sports program. Third, sport is seen to provide these youth with an opportunity to connect with and attach themselves to significant others outside the family. Positive relationships with teammates and coaches is especially important for youth at risk, who might not have sufficient opportunities for attachment with their parents and other family members. Youth who participate in sports programs might be discouraged from committing crime in order not to disappoint these significant others. Fourth, according to this theory, certain of society’s norms and values are reflected in organized physical activities. As a result, participation in sport might serve to strengthen young people’s belief in and adherence to society and its laws (Hirschi, 1969; Kreager, 2007; Spruit et al., 2016).

Another goal of the study was to explore whether the effect of sports participation on adolescents’ behavior was affected by the programs’ components or features. Previous studies that examined sport type as a possible interaction effect between sports participation and delinquent behavior have posed two interesting questions. One question is whether there are differences in levels of youth delinquency according to sport type. Our results found no significant difference in levels of delinquent behavior between youth who participated in high, low, and no contact sports. This is different from previous studies that found that youth who participate in heavy contact sports are involved in more violence and assault than those who participate in low contact sports (Davis & Menard, 2013; Endresen & Olweus, 2005; Spruit et al., 2016). Future studies should further examine these results, especially in light of the small number of our study’s participants who engaged in heavy contact sports.

The second question is whether certain aspects of sport type have a moderating effect on the relationship between participation in sport and delinquent behavior. In our study, we examined whether sport type had a moderating effect on the relationship between sports participation and juvenile delinquency. We found no interaction effects between sport type and participation in the sports program. The only significant effect that was found was the association between youth participation in a sports program and involvement in delinquent behavior. These results are consistent with findings reported by Morris et al. (2004), in which the level of involvement in delinquency among youth decreased as a result of participation in a sport program, regardless of the sport type (team, individual, high, low, or no contact). However, these findings are contrary to those reported by Spruit et al. (2016), in which sport type had a moderating effect on the relationship between sports participation and juvenile delinquency.

Insignificant interaction effects were found between participation in sports programs and the program features we examined (intensity; staff training and supervision; and program interaction with community services). These findings are contrary to previous studies that found that the protective effects of participation in sports programs against juvenile delinquency are maximized when the program includes elements that guarantee a positive and safe environment (Carmichael, 2008; Côté & Gilbert, 2009). On the one hand, it might be that the program features we explored in our study are not central to youth development or are not strong enough to have an effect on the change that resulted from participation. On the other hand, it might be that because the sports programs we examined were specifically designed to help youth at risk, participation in the program alone fulfills the required conditions for positive behavioral change. For these at-risk youth, participation in physical activity programs designed to meet their specific needs might be the important element, rather than the specific features of these programs. This interpretation needs to be further examined in future studies as it might help in the design of sport programs for at-risk youth.

Study Limitations and Recommendations

The current study used a before-and-after research design to study the effects of participation in sports programs on crime participation among at-risk youth. Because of this design and the lack of a control group, the causality of the relationships between participation and youth outcomes cannot be drawn. Future studies should use an experimental before-and-after research design with a control group in order to be able to make conclusions about a causal relationship between participation in sports programs and youth involvement in delinquency.

The sample used in this study was a convenience sample consisting only of boys. The generalizability of the results to all youth at risk in Israel is limited. Future studies should use a larger sample of both male and female adolescents who participate in sports programs. Also, future studies that include a wider variety of team, individual, high, low, and no contact sports might be better able to draw comparisons between sport types.

Additionally, the information on youth behavior used in this study was based solely on self-reports. Future studies should collect information from other data sources, such as coaches and peers.

Also, because the program features we explored had no effects on the benefits that participation in physical activity programs provided, future studies should explore additional program components that might affect the benefits of participation, such as relationships between teammates and with their coach. If program features are found that heighten the benefits afforded by participation in sports programs, they can be integrated into program designs in order to maximize the impact on youth behavior.

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

The finding that participation in sports programs is associated with lower levels of involvement in delinquency highlights the importance of sports participation among youth at risk in Israel. However, because youth at risk usually come from low socioeconomic status families (Schmid, 2007) (for example, > 50% of the study’s participants reported their family economic status to be low), efforts should be expanded to make these programs widely available and affordable for at-risk youth in Israel. This is critical because low economic status youth at risk often live in disadvantaged neighborhoods with a limited amount of extracurricular and leisure activities (Schmid, 2007). Even when these activities are available, at-risk youth often cannot afford the payment required to participate (Schneider & Shoham, 2017). Therefore, there is a clear need for funding to be allocated to such programs by the Israeli Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Social Affairs and Services. This is important because sports activities have been shown to improve young people’s feelings of competence, connectedness, empowerment, and responsibility (Eley and Kirk, 2002; France, Sutton, Sandu, & Waring, 2007; Russell, 2005), which all may result in helping to decrease their levels of involvement in delinquency (Carmichael, 2008; Morris et al., 2004).

References

Amodei, N., & Scott, A. A. (2002). Psychologists’ contribution to the prevention of youth violence. The Social Science Journal, 39, 511–526.

Andrews, J. P., & Andrews, G. J. (2003). Life in a secure unit: The rehabilitation of young people through the use of sport. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 531–550.

Armour, K., Sandford, R., & Duncombe, R. (2013). Positive youth development and physical activity/sport interventions: Mechanisms leading to sustained impact. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 18, 256–281.

Bailey, R. (2006). Physical education and sport in schools: A review of benefits and outcomes. Journal of School Health, 76, 397–401.

Begg, D. J., Langley, J. D., Moffitt, T., & Marshall, S. W. (1996). Sport and delinquency: An examination of the deterrence hypothesis in a longitudinal study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 30, 335–341.

Biddle, S. (2006). Defining and measuring indicators of psycho-social well- being in youth sport and physical activity. In Y. Vanden-Auweele, C. Malcom & B. Meulders (Eds.), Sports and development (pp. 163–184). Teuven: Lannoo Campus.

Burton, J. M., & Marshall, L. A. (2005). Protective factors for youth considered at risk of criminal behaviour: Does participation in extracurricular activities help? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 15, 46–64.

Carmichael, D. (2008). Youth sport vs. youth crime. Brockville, ON: Active Heathy Links.

Coie, J. D., Lochman, J. E., Terry, R., & Hyman, C. (1992). Predicting early adolescent disorder from childhood aggression and peer rejection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 783–792.

Côté, J., & Gilbert, W. (2009). An integrative definition of coaching effectiveness and expertise. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 4, 307–323..

Crosnoe, R. (2001). The social world of male and female athletes in high school. In D. A. Kinney (Ed.), Sociological studies of children and youth (pp. 89–110). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing..

Danish, S. J. (2002). Teaching life skills through sport. In M. Gatz, M. A. Messner & S. J. Ball-Rokeach (Eds.), Paradoxes of youth and sport (pp. 49–59). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Danish, S. J., Taylor, T. E., & Fazio, R. J. (2003). Enhancing adolescent development through sports and leisure. Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence, 12, 92–108..

Davis, B. S., & Menard, S. (2013). Long term impact of youth sports participation on illegal behavior. The Social Science Journal, 50, 34–44..

Donaldson, S. J., & Ronan, K. R. (2006). The effect of sports participation on young adolescents’ well-being. Adolescence, 41, 370–389.

Eley, D., & Kirk, D. (2002). Developing citizenship through sport: The impact of a sport-based volunteer programme on young sport leaders. Sport, Education and Society, 7, 151–166..

Elliott, D. S., & Ageton, S. S. (1980). Reconciling race and class differences in self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 45, 95–110.

Endresen, I. M., & Olweus, D. (2005). Participation in power sports and antisocial involvement in preadolescent and adolescent boys. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 468–478.

Farineau, H. M., & McWey, L. M. (2011). The relationship between extracurricular activities and delinquency of adolescents in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 963–968.

Foshee, V. A., Gottfredson, N. C., Reyes, H. L. M., Chen, M. S., David-Ferdon, C., Latzman, N. E., Tharp, A. T., & Ennett, S. T. (2016). Developmental outcomes ofusing physical violence against dates and peers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58, 665–671.

France, A., Sutton, L., Sandu, A., & Waring, A. (2007). Making a positive contribution: The implications for youth work of Every Child Matters. The National Youth Agency Research Programme Series. Retrieved June 15, 2010, from http://www.crsp.ac.uk/downloads/publications/alans_publications/making_a_positive_contribution.pdf.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42, 698–713.

Gass, M. A., & Priest, S. (1997). Effective leadership in adventure programming. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Hans, T. A. (2000). A meta-analysis of the effects of adventure programming on the locus of control. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 30, 33–60.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Khoury, N., & Ali, R. (2015). Arab youth involvement in delinquency and political violence and parental control: The mediating role of religiosity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85, 576–585.

Kravets-Fenner, Y., Khoury-Kassabri, M., Aszenstadt, M., & Amedi, S. (2013). Risk factors for delinquency and anti-social behavior among adolescents treated by the Division of At-Risk Youth. Journal of Welfare and Society, 33, 41–70 (Hebrew).

Kreager, D. A. (2007). Unnecessary roughness? School sports, peer networks, and male adolescent violence. American Sociological Review, 72, 705–724.

Langbein, L., & Bess, R. (2002). Sports in school: Source of amity or antipathy? Social Science Quarterly, 83, 436–454.

Larson, A., & Silverman, S. J. (2005). Rationales and practices used by caring physical education teachers. Sport, Education and Society, 10, 175–193.

Limbos, M. A., Chan, L. S., Warf, C., Schneir, A., Iverson, E., Shekelle, P., & Kipke, M. D. (2007). Effectiveness of interventions to prevent youth violence: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33, 65–74.

Makkai, T., Morris, L., Sallybanks, J., & Willis, K. (2003). Sport, physical activity and antisocial behaviour in youth. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology..

McKenney, A. (2001). Sport as a context for teaching prosocial behavior to adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. Retrieved October 20, 2017, from http://www.lin.ca.

McMahon, S. D., & Washburn, J. J. (2003). Violence prevention: An evaluation of program effects with urban African American students. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 24, 43–62.

Morris, L., Sallybanks, J., Willis, K., & Makkai, T. (2004). Sport, physical activity and antisocial behavior in youth. Youth Studies Australia, 23, 47–62.

Nichols, G. (1997). A consideration of why active participation in sport and leisure might reduce criminal behaviour. Sport, Education and Society, 2, 181–190.

Poinsett, A. (1996). The role of sports in young development. New York: Carnegie Corporation.

Rhea, D. J., & Lantz, C. D. (2004). Violent, delinquent, and aggressive behaviors of rural high school athletes and non-athletes. Physical Educator, 61, 170–176.

Russell, I. M. (2005). A national framework for youth action and engagement. London: HMSO.

Sandford, R. A., Armour, K. M., & Duncombe, R. (2007). Physical activity and personal/social development for disaffected youth in the UK: In search of evidence. In N. Holt (Ed.), Positive youth development through sport (pp. 97–109). London: Routledge.

Sandford, R. A., Armour, K. M., & Warmington, P. C. (2006). Re-engaging disaffected youth through physical activity programmes. British Educational Research Journal, 32, 251–271.

Sandford, R. A., Duncombe, R., & Armour, K. M. (2008). The role of physical activity/sport in tackling youth disaffection and anti-social behaviour. Educational Review, 60(4), 419–435.

Schmid, H. (2007). Children and youth at risk in Israel: Findings and recommendations to improve their wellbeing. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(8), 1114–1128.

Schneider, A., & Shoham, L. (2017). Informal education in Israel’s Arab society: From an overlooked field to a government priority. Inter-Agency Task Force on Israeli Arab Issues.

Slavin, M., Pilver, C. E., Hoff, R. A., Krishnan-Sarin, S., Steinberg, M. A., Rugle, L., & Potenza, M. (2013). Serious physical fighting and gambling related attitudes and behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2, 167–178.

Smith, R. E., & Smoll, F. L. (1991). Behavioral research and intervention in youth sports. Behavior Therapy, 22, 329–344.

Spruit, A., van der Put, C., van Vugt, E., & Stams, G. J. (2017). Predictors of intervention success in a sports-based program for adolescents at risk of juvenile delinquency. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X17698055.

Spruit, A., Van Vugt, E., van der Put, C., van der Stouwe, T., & Stams, G. J. (2016). Sports participation and juvenile delinquency: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 655–671.

Statland-Vaintraub, O., Khoury-Kassabri, M., Aszenstadt, M., & Amedi, S. (2012). Risk factors for involvement in delinquency among immigrants and native-born Israeli girls. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 2052–2060.

Zionit, Y., & Kosher, H. (2013). Children in Israel - An annual statistical abstract. Jerusalem: Center for Research and Public Education, National Council for the Child. (Hebrew).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the many young people and program managers and coordinators who generously gave their time and support to make this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Hebrew University research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Schneider, H. The Relationship Between Israeli Youth Participation in Physical Activity Programs and Antisocial Behavior. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 35, 357–365 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0528-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0528-y