Abstract

Purpose

To compare characteristics of patients with possible statin intolerance identified using different claims-based algorithms versus patients with high adherence to statins.

Methods

We analyzed 134,863 Medicare beneficiaries initiating statins between 2007 and 2011. Statin intolerance and discontinuation, and high adherence to statins, defined by proportion of days covered ≥80 %, were assessed during the 365 days following statin initiation. Definition 1 of statin intolerance included statin down-titration or discontinuation with ezetimibe initiation, having a claim for a rhabdomyolysis or antihyperlipidemic event followed by statin down-titration or discontinuation, or switching between ≥3 types of statins. Definition 2 included beneficiaries who met Definition 1 and those who down-titrated statin intensity. We also analyzed beneficiaries who met Definition 2 of statin intolerance or discontinued statins.

Results

The prevalence of statin intolerance was 1.0 % (n = 1320) and 5.2 % (n = 6985) using Definitions 1 and 2, respectively. Overall, 45,266 (33.6 %) beneficiaries had statin intolerance by Definition 2 or discontinued statins and 55,990 (41.5 %) beneficiaries had high adherence to statins. Compared with beneficiaries with high adherence to statins, those with statin intolerance and who had statin intolerance or discontinued statins were more likely to be female versus male, and black, Hispanic or Asian versus white. The multivariable adjusted odds ratio for statin intolerance by Definitions 1 and 2 comparing patients initiating high versus low/moderate intensity statins were 2.82 (95%CI: 2.42–3.29), and 8.58 (8.07–9.12), respectively, and for statin intolerance or statin discontinuation was 2.35 (2.25–2.45).

Conclusions

Definitions of statin intolerance presented herein can be applied to analyses using administrative claims data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The efficacy of statins for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) has been demonstrated in several randomized controlled trials [1, 2]. Based on these data, guidelines for the management of blood cholesterol recommend treatment with high-intensity statins for patients with high ASCVD risk [3, 4]. As a consequence, the use of statins has increased substantially over the past two decades [5, 6]. However, some patients initiating statins experience side effects that result in intolerance to this medication [7–9]. Intolerance can lead to discontinuation, down-titration or low adherence to statin therapy, thereby limiting the ASCVD risk reduction benefits from statins [10, 11].

Currently, there is no standard definition for statin intolerance [12, 13]. Furthermore, there are no validated algorithms to identify patients with statin intolerance in studies using administrative claims data. Identification and investigation of patients with statin intolerance in administrative claims data can provide estimates of ASCVD risk and identify risk factors associated with this condition. The objective of this study was to compare characteristics of patients with possible statin intolerance identified using different administrative claims-based algorithms versus patients with high adherence to statins.

Methods

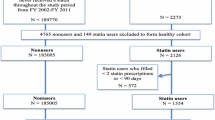

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a 5 % random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. Medicare is a program funded by the US government that provides health insurance to residents ≥65 years of age and those who are unable to work due to disability, or who have end-stage renal disease. Since 2006, Medicare also provides pharmacy benefits (i.e., Medicare Part D). We analyzed beneficiaries with a statin fill between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2011. We restricted the analysis to beneficiaries who initiated lipid-lowering therapy with a statin, defined by having no fills for statins, ezetimibe, niacin, fibrates, or bile acid sequestrants during the 365 days prior to the first or “index” statin fill (i.e., the “look-back” period). We required beneficiaries to be ≥65 years of age at the start of the look-back period (i.e., one year before initiating lipid-lowering therapy). We excluded Medicare beneficiaries <65 years of age because younger US adults with Medicare insurance coverage represent a select population who are either disabled or have end-stage renal disease. We also required Medicare beneficiaries to have continuous full Medicare fee-for-service coverage for the look-back period. We defined full Medicare fee-for-service coverage as having Medicare Parts A (inpatient), B (outpatient), and D (pharmacy) coverage. Medicare Part C (also known as Medicare Advantage) is a capitated program and beneficiaries with this coverage are not required to submit a claim for services received. Therefore, Medicare beneficiaries with Part C coverage during the look-back period were excluded. We further restricted the analysis to beneficiaries who were alive and had full Medicare fee-for-service coverage for 365 days after their statin fill (i.e., the assessment period). After these criteria were applied, 134,863 Medicare beneficiaries were included in the present analysis (Fig. 1). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved the study.

Medicare Data and Definitions

We obtained Medicare beneficiaries’ data for January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2012 from the CMS Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW). These data included enrollment information and inpatient, outpatient, carrier, skilled nursing facility, home health agency, durable medical equipment, hospice and Part D prescription drug claims. Outpatient and carrier claims identify ambulatory services submitted to Medicare by institutional (e.g., hospitals and clinics) and non-institutional (e.g., clinicians and nurse practitioners) providers, respectively. Statin fills were identified using generic names from Medicare Part D claims and included atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin. We defined the intensity of the statin fills in accordance with the 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) Cholesterol Guidelines as shown in Supplemental Table 1 [3]. Ezetimibe, niacin, fibrate, and bile acid sequestrant fills were also identified from Part D claims. As described above, beneficiaries with a fill for a statin, ezetimibe, niacin, a fibrate or a bile acid sequestrant during the look-back period were excluded from the analysis. We used Medicare enrollment information to obtain data on age at the time of statin initiation, sex and race/ethnicity. We used claims data during the look-back period to determine comorbid conditions including history of diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease and hypothyroidism (Supplemental Table 2). For each beneficiary, we calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index using Romano’s method [14].

We used generic names from Medicare Part D claims during the look-back period to calculate the number of medications filled by beneficiaries and to identify beneficiaries who filled cyclosporine and antihypertensive medication. Polypharmacy was defined by filling more than 10 medications during the look-back period. Use of antihypertensive medication was defined by having ≥2 claims for any of the following five medication classes during the look-back period: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics (Supplemental Table 3). These are the five antihypertensive medication classes most commonly used by US adults [15]. For each beneficiary, we calculated the proportion of days covered (PDC) for each antihypertensive medication class using the pharmacy-based method, as described previously [16, 17]. Days spent in the hospital did not contribute to the calculation of the PDC. The average PDC across the five classes of antihypertensive medication was calculated and used for the analyses, with high adherence to antihypertensive medication defined as a PDC ≥80 %.

Defining Statin Intolerance and High Adherence to Statins

We used two definitions to identify Medicare beneficiaries with possible statin intolerance in the year following initiation. These definitions are based on factors identified as adverse events indicating statin intolerance and factors associated with the clinical management of statin intolerance according to clinical practice guidelines [3, 18–21]. Definition 1 of statin intolerance included the following components:

-

Statin down-titration with initiation of ezetimibe

-

Statin discontinuation with initiation of ezetimibe

-

Rhabdomyolysis with statin down-titration or discontinuation

-

Other adverse events related to an antihyperlipidemic agent with statin down-titration or discontinuation

-

Switching between ≥3 types of statins

Many people with statin intolerance may down-titrate treatment without initiating ezetimibe or having a claim with a diagnosis code for rhabdomyolysis or an adverse effect of an antihyperlipidemic agent. Therefore, Definition 2 of statin intolerance included all components of Definition 1 plus down-titration of statin intensity. Components used as part of each of the two definitions of statin intolerance are described in Table 1. Intolerance is a frequent cause of statin discontinuation [18–20]. Therefore, we investigated the occurrence of statin discontinuation in the year following initiation. Discontinuation of statins was defined by having no days of supply for statins for the final 90 days in the year following statin initiation (from day 276 through day 365).

Among beneficiaries without statin intolerance by either of the two definitions, high adherence to statins over the year following initiation was defined by a PDC ≥80 % using the interval-based method [17]. Days spent in the hospital did not contribute to the calculation of the PDC.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the number and proportion of Medicare beneficiaries who had statin intolerance by Definitions 1 and 2, discontinued statins, had statin intolerance by Definition 2 or discontinued statins, and had high adherence to statins in the 365 days following initiation of lipid-lowering therapy. We also calculated the number and proportion of Medicare beneficiaries fulfilling each component of the definitions (i.e., those who down-titrated statins with initiation of ezetimibe, discontinued statins with initiation of ezetimibe, had rhabdomyolysis with statin down-titration or discontinuation, had an adverse event related to an antihyperlipidemic agent with statin down-titration or discontinuation, filled ≥3 types of statins during the assessment period, or down-titrated statins). Among Medicare beneficiaries who met Definition 1 of statin intolerance, we calculated the proportion fulfilling each component of this definition stratified by the intensity of the index statin fill.

We calculated the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries with statin intolerance by Definitions 1 and 2, and those who met Definition 2 or discontinued statins in the year following statin initiation. We also calculated the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries with high adherence to statins in the look-back period. We used logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for statin intolerance, using Definitions 1 and 2 separately, versus high adherence to statins associated with beneficiary characteristics. Characteristics investigated include age, sex, race/ethnicity, history of diabetes, myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease and hypothyroidism, Charlson Comorbidity Index, polypharmacy, use of cyclosporine, use of and adherence to antihypertensive medications, and statin fill intensity upon initiation. Hypothyroidism has been previously shown to be associated with muscular symptoms among patients taking statins [10]. Cyclosporine increases plasma levels of statins by inhibition of the CYP3A4 enzyme system, increasing the risk for statin-induced toxicity [22, 23]. We also used logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for statin intolerance by Definition 2 or statin discontinuation versus high adherence to statins associated with beneficiary characteristics. Logistic regression models included adjustment for all characteristics simultaneously. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and a two-sided alpha <0.05.

Results

Among the 134,863 beneficiaries included in the analysis, the prevalence of statin intolerance by Definitions 1 and 2 was 1.0 % (n = 1320) and 5.2 % (n = 6985), respectively (Fig. 2). When each component of the definitions was analyzed separately, 108 (0.1 %) beneficiaries down-titrated statins and initiated ezetimibe, 608 (0.5 %) discontinued statins and initiated ezetimibe, 155 (0.1 %) had rhabdomyolysis with statin down-titration or discontinuation, 49 (0.04 %) had an adverse event with statin down-titration or discontinuation, 432 (0.3 %) filled ≥3 types of statins, and 5948 (4.4 %) down-titrated statins in the year following initiation. Among beneficiaries meeting Definition 1 of statin intolerance, those who initiated low/moderate intensity statins were less likely to down-titrate their statin with ezetimibe initiation compared with those who initiated high intensity statins, but were more likely to discontinue statins with ezetimibe initiation (Table 2). Among Medicare beneficiaries included in the analysis, 39,868 (29.6 %) discontinued statins within 365 days after initiation. Overall, 45,266 (33.6 %) beneficiaries had statin intolerance by Definition 2 or discontinued statins in the year following initiation, and 55,990 (41.5 %) had high adherence to statins.

Compared with beneficiaries who had high adherence to statins, those with statin intolerance by each of the definitions were more likely to be female, black, Hispanic or Asian, have a history of coronary heart disease, polypharmacy, and initiate statins at high intensity (Table 3). Beneficiaries who met definitions of statin intolerance were less likely to take antihypertensive medication with high adherence compared with those with high adherence to statins. Medicare beneficiaries meeting Definition 2 of statin intolerance or discontinuing statins were more likely to be female, black, Hispanic and Asian versus white race-ethnicity and less likely to be taking antihypertensive medications and have high adherence to antihypertensive medication compared with those with high adherence to this medication.

After multivariable adjustment, older age was associated with a lower odds ratio for statin intolerance by each definition (Table 4). Female sex, black and Asian race and Hispanic ethnicity versus white race, a history of coronary heart disease, polypharmacy and initiating statins with high versus low/moderate intensity were associated with a higher multivariable adjusted odds ratio for statin intolerance. Not taking antihypertensive medication and taking antihypertensive medication with high adherence were associated with a lower odds ratio for statin intolerance by each definition compared with taking antihypertensive medication with low adherence. Also, a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index was associated with a lower odds ratio for statin intolerance by Definition 1, whereas a history of heart failure was associated with a lower odds ratio for statin intolerance by Definition 2. Female, black, Hispanic and Asian versus white race-ethnicity, a history of stroke and heart failure, Charlson Comorbidity index, polypharmacy, use of and adherence to antihypertensive medications, and statin intensity upon initiation were also associated with having statin intolerance by Definition 2 or discontinuing statins.

Discussion

In this study, we developed two algorithms to identify patients with possible statin intolerance in Medicare claims data. We found that the prevalence of statin intolerance ranged from 1.0 % for Definition 1 to 5.2 % for Definition 2. Overall, 33.6 % of Medicare beneficiaries had statin intolerance or discontinued statins in the year following initiation. Age, sex, race/ethnicity and polypharmacy were associated with statin intolerance by each definition. Also, beneficiaries initiating statins at high intensity were more likely to develop intolerance by each definition as compared to those initiating low/moderate intensity statins. Algorithms developed as part of this analysis represent an initial approach to investigate statin intolerance using claims data.

The occurrence of adverse events following statin initiation, particularly muscle problems, varies substantially across published studies. In a comparison of 26 randomized clinical trials of statins, the proportion of participants taking this medication who experienced muscle problems ranged from <1 % to >50 % [24]. This variation can be explained by differences in the definition of adverse muscle events being used in each study, which may identify different subpopulations of patients experiencing intolerance. For example, rates of muscle problems reported in the literature are lower when strict definitions based on objective laboratory measurements are used compared with definitions that also include self-reported symptoms [21]. In our study, the prevalence of statin intolerance varied across algorithms. Differences in prevalence estimates can be explained in terms of different degrees of sensitivity and specificity of the algorithms to detect statin intolerance. For example, sensitivity (i.e., the percentage of those with statin intolerance that are identified with the algorithm) is expected to be higher with Definition 2 because more patients are classified as intolerant compared with Definition 1. However, Definition 1 may have a high degree of specificity such that few people will be categorized as statin intolerant when they are not intolerant. Adding statin discontinuation to the algorithms could contribute to identify more patients with statin intolerance, increasing sensitivity. However, adding statin discontinuation may substantially decrease specificity. As a consequence of differences on sensitivity and specificity, populations identified as statin intolerant with each algorithm could also differ on the characteristics of adverse events experienced, including type and severity. Future studies should evaluate the performance of these algorithms, including their sensitivity and specificity, using for example patient medical charts and some of the clinical definitions of statin intolerance available in the literature [12, 21].

In this analysis, patients who initiated statins at high intensity were more likely to have intolerance versus high adherence to this medication as compared to those initiating low/moderate intensity statins. These results are consistent with randomized controlled trial data showing a higher risk for adverse events associated with high versus low/moderate intensity statins. In the Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in Cholesterol and Homocysteine (SEARCH), the risk for myopathy confirmed by laboratory or clinical evaluation among participants who were randomly assigned to simvastatin 80 versus 20 mg/daily was 0.9 % and 0.03 %, respectively (p-value <0.001) [25]. A higher risk for myopathy associated with simvastatin 80 versus 20 mg/daily was also found in the A to Z trial [26]. In addition, in the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 (PROVE IT-TIMI 22) study, high intensity therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg/daily was associated with an increased risk for liver enzyme elevation compared with moderate intensity treatment using pravastatin 40 mg/daily [27]. In our analysis, we also observed a higher likelihood of statin intolerance among Medicare beneficiaries with a history of coronary heart disease, which was consistent with a prior analysis of 315 patients referred to a Veterans Affairs lipid clinic [28]. In contrast, we found that a history of hypothyroidism or cyclosporine use was not associated with having statin intolerance as has been previously reported [10, 22, 23]. Clinicians prescribing low intensity therapy when initiating statins in populations known to have higher risk for intolerance could explain this observation.

Statins are effective in reducing ASCVD events [29–31]. Thus, patients with demonstrated statin intolerance who discontinue or down-titrate statin therapy or have low adherence to statins may have residual ASCVD risk [10, 11]. Observational studies and pragmatic clinical trials using claims data could characterize patients with statin intolerance, determine their residual ASCVD risk and identify factors that could be targets for interventions. However, these studies are currently limited because the lack of a standardized definition and algorithm to identify patients with statin intolerance using claims data [12, 13]. Following prior published recommendations for the assessment and management of statin intolerance in clinical practice [3, 18–21], we developed two algorithms that could be used in future claims-based studies to identify patients with this condition. However, results from these studies should be interpreted with caution until more information on the validity of these algorithms become available.

There are potential and known limitations to the current study. Our study does not include a gold standard definition for statin intolerance and sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predicted values of the algorithms we developed are unknown. Definitions of rhabdomyolysis, adverse effect of an antihyperlipidemic agent and comorbid conditions are based on diagnosis codes provided by treating clinicians for billing purposes and are not standardized. Another potential weakness of these algorithms is that they may not detect mild cases of statin intolerance that did not result in changes in the pattern of statin use. Specifically, some patients who experience side effects from statins may not down-titrate, discontinue or change statins [7]. Also, pharmacy claims identify beneficiaries who fill a drug using their pharmacy benefits, but not those who paid out-of-the pocket or received free samples. Pharmacy claims also do not provide information on whether beneficiaries actually took their medication [32]. Information on whether patients stopped filling a prescription medication following medical advice is not available in Medicare claims. Finally, the current results may not be generalized to younger adults as we included Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years of age at the start of look-back period.

In the current analysis, we describe two algorithms that can be used to identify and investigate statin intolerance using administrative claims data. These algorithms are expected to have different sensitivity and specificity, and the decision of which algorithm(s) use should be based on the objective(s) of the analysis. Ultimately, studies using these algorithms can provide useful information to develop specific interventions aimed to reduce residual ASCVD risk among patients with statin intolerance.

References

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78.

Taylor F, Ward K, Moore TH et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD004816.

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1–45.

Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421.

Mann D, Reynolds K, Smith D, Muntner P. Trends in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels among US adults: impact of the 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1208–15.

Muntner P, Levitan EB, Brown TM, et al. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of high low density lipoprotein-cholesterol among United States adults from 1999 to 2000 through 2009-2010. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:664–70.

Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:526–34.

Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding statin use in America and gaps in patient education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6:208–15.

Parker BA, Capizzi JA, Grimaldi AS, et al. Effect of statins on skeletal muscle function. Circulation. 2013;127:96–103.

Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients--the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:403–14.

Wei MY, Ito MK, Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA. Predictors of statin adherence, switching, and discontinuation in the USAGE survey: understanding the use of statins in America and gaps in patient education. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7:472–83.

Banach M, Rizzo M, Toth PP, et al. Statin intolerance - an attempt at a unified definition. Position paper from an international lipid expert panel. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:1–23.

Guyton JR, Bays HE, Grundy SM, Jacobson TA, The National Lipid Association Statin Intolerance Panel. An assessment by the statin intolerance panel: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:S72–81.

Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Presentation adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–9.

Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among United States adults with hypertension: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation. 2012;126:2105–14.

Muntner P, Yun H, Sharma P, et al. Ability of low antihypertensive medication adherence to predict statin discontinuation and low statin adherence in patients initiating treatment after a coronary event. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:826–31.

Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, et al. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:457–64.

Arca M, Pigna G. Treating statin-intolerant patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:155–66.

Bitzur R, Cohen H, Kamari Y, Harats D. Intolerance to statins: mechanisms and management. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 2):S325–30.

Fitchett DH, Hegele RA, Verma S. Cardiology patient page. Statin intolerance Circulation. 2015;131:e389–91.

Rosenson RS, Baker SK, Jacobson TA, Kopecky SL, Parker BA, The National Lipid Association's Muscle Safety Expert P. An assessment by the statin muscle safety task force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:S58–71.

Jamal SM, Eisenberg MJ, Christopoulos S. Rhabdomyolysis associated with hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase inhibitors. Am Heart J. 2004;147:956–65.

Law M, Rudnicka AR. Statin safety: a systematic review. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:52C–60C.

Ganga HV, Slim HB, Thompson PD. A systematic review of statin-induced muscle problems in clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2014;168:6–15.

Armitage J, Bowman L, Wallendszus K, et al. Intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol with 80 mg versus 20 mg simvastatin daily in 12,064 survivors of myocardial infarction: a double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1658–69.

de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Early intensive vs a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes: phase Z of the a to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307–16.

Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–504.

Harris LJ, Thapa R, Brown M, et al. Clinical and laboratory phenotype of patients experiencing statin intolerance attributable to myalgia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:299–307.

Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Berg K, et al. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S). Atheroscler Suppl. 2004;5:81–7.

Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–9.

The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349–57.

Colantonio LD, Kent ST, Kilgore ML, et al. Agreement between Medicare pharmacy claims, self-report, and medication inventory for assessing lipid-lowering medication use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016. doi:10.1002/pds.3970.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The design and conduct of the study, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and preparation of the manuscript, was supported through a research grant from Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA). The academic authors conducted all analyses and maintained the rights to publish this article.

Conflict of Interest

STK received research support from Amgen, Inc. KLM and AM work in the Center for Observational Research at Amgen, Inc. KLM and AM also have stock ownership in Amgen, Inc. MLK, RSR and PM receive research support from Amgen, Inc. RSR also receives research support from Medicines Company, Regeneron and Sanofi, and serves on Advisory Boards for Amgen, Inc., Regeneron and Sanofi. LDC, LH, LC and MCS have no disclosures.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 52 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colantonio, L.D., Kent, S.T., Huang, L. et al. Algorithms to Identify Statin Intolerance in Medicare Administrative Claim Data. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 30, 525–533 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-016-6680-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-016-6680-3