Abstract

This study sought to discover which atherosclerotic plaque components co-localize with enhanced [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in carotid positron emission tomography (PET) images. Although in vivo PET currently lacks the resolution, high-resolution ex vivo FDG-microPET with histology validation of excised carotid plaque might accomplish this goal. Thirteen patients were injected with FDG before carotid endarterectomy. After excision, the plaque specimens were scanned by microPET and magnetic resonance imaging, and then serially sectioned for histological analysis. Two analyses were performed using generalized linear mixed models: (1) a PET-driven analysis which sampled high and low FDG uptake areas from PET images to identify their components in matched histology specimens; and (2) a histology-driven analysis where specific plaque components were selected and matched to corresponding PET images. In the PET-driven analysis, regions of high FDG uptake were more likely to contain inflammatory cells (p < 0.001) and neovasculature (p = 0.008) than regions of low FDG uptake. In the histology-driven analysis, regions with inflammatory cells (p = 0.001) and regions with loose extracellular matrix (p = 0.001) were associated with enhanced FDG uptake. Furthermore, areas of complex inflammatory cell infiltrate (co-localized macrophages, lymphocytes and foam cells) had the highest FDG uptake among inflammatory subgroups (p < 0.001). In conclusion, in carotid plaque, regions of inflammatory cell infiltrate, particularly complex one, co-localized with enhanced FDG uptake in high-resolution FDG-microPET images. Loose extracellular matrix and areas containing neovasculature also produced FDG signal. This study points to the potential ability of FDG-PET to detect the cellular components of the vulnerable plaque.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a leading cause of cardiovascular disease [1]. Beyond restriction of flow due to luminal stenosis, the composition of the plaque has been shown to be a critical component in the diagnosis of vulnerable plaque and in disease management [2]. Vulnerable plaques are characterized by active inflammation, increased neovasculature, intraplaque hemorrhage, a thin fibrous cap and a large lipid core [2–4].

[18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) has shown promise in detecting metabolically active inflammatory cell infiltrates associated with vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque [4–7]. In a prospective clinical study of FDG-PET in atherosclerosis, Rudd et al. [5] demonstrated that symptomatic, unstable carotid plaques accumulated more FDG than asymptomatic lesions. Another group found a strong association between FDG uptake in carotid plaque and macrophage density, suggesting that in vivo FDG-PET imaging can be used to assess severity of inflammation in carotid plaques in vivo [8]. However, there is controversy regarding which components of the plaque are responsible for FDG-PET uptake [9, 10]. The limited resolution of in vivo FDG-PET does not provide accurate co-localization information of FDG uptake with specific plaque components. High-resolution imaging techniques have also been utilized to explore this question. In Rudd’s study [5], accumulated deoxyglucose in macrophage-rich areas were detected using autoradiography in three plaque specimens. Another ex vivo study used FDG-microPET to investigate associations between FDG uptake and macrophages [11]. However, these ex vivo studies incubated plaque specimens with FDG after excision, which may not accurately reflect in vivo FDG uptake in plaques fed via the bloodstream.

To address this limitation, we utilized high-resolution microPET on carotid plaques excised from patients injected with FDG just prior to carotid endarterectomy (CEA). Our aim was to investigate which plaque components contribute to enhanced FDG uptake in vivo.

Materials and methods

Patient population

Fourteen patients scheduled for elective CEA were recruited after providing informed consent (12 men, 2 women, age 54–83). The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. The inclusion criteria for carotid endarterectomy was that patients either be asymptomatic with >80 % carotid stenosis or symptomatic with >50 % carotid stenosis.

Image acquisition

Approximately 1 h before CEA, patients were injected with FDG (9.1 ± 1.7 mCi) intravenously. The carotid plaques were excised intact with special effort taken to minimize disruption of lesion. The ex vivo plaque specimens were scanned within 4 h after injection using microPET (Siemens Inveon, Knoxville, TN). Images were reconstructed into 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.8 mm3 voxels using the vendor 3D MAP algorithm with a spatial resolution specification of 2.5 mm full width at half maximum. Specimens were then imaged by T1-weighted MRI (3T Philips Achieva, Best, Netherlands): TR/TE = 550/12.3 ms, resolution = 0.16 × 0.16 mm2, and slice thickness = 1 mm. After imaging, the intact CEA specimens were fixed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin, decalcified in 10 % formic acid, and processed to paraffin en bloc. Serial sections were taken at every millimeter in the common carotid and at every 0.5 mm throughout the bulb and the internal carotid to the end of the specimen. Sections from each level were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

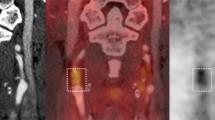

Image co-registration

MRI was used to facilitate matching between PET images and histology, an approach previously described by Kerwin et al. [12]. The axial PET images were first manually co-registered to axial MR images (Fig. 1), which was carefully performed by two reviewers using lumen and out wall boundary and bifurcation location information. Two histologists, blinded to the PET image findings, matched the histology slices to the MR cross-sectional images by referring to the bifurcation location and plaque anatomy. Once matched, regions of interest on the PET images were automatically mapped to the corresponding region on MRI and vice versa. This allowed histology readers to remain blinded to the corresponding PET information and the PET analysis to be blinded to histology.

Matched carotid FDG-microPET/MRI and histology images. Axial matched carotid images of FDG-micro PET (a), MRI (b), fused PET/MRI (c) and histology image stained with hematoxylin and eosin (d). Plaque components were identified by histology and marked (yellow cross) in the corresponding MRI image. The averaged SUV in the ROI (2 mm × 2 mm, red square) centered at the cross were calculated from the matched PET image. Accumulated foam cells (red arrowhead), three types of inflammatory cells with co-localized hemorrhage (blue arrowhead) showed enhanced FDG uptake, while calcification (red arrow) showed low FDG uptake. PET images shown here were normalized by the maximize intensity of the plaque. ROI region of interest, SUV standard uptake value

PET-driven analysis

To investigate sources of enhanced PET signal, a bidirectional analysis approach was adopted. First, in the PET-driven analysis, 1 mm2 regions of high and low FDG uptake were automatically identified on PET images with signal either in excess of 200 % of averaged FDG uptake of dense fibrous tissue (high uptake) or below the 150 % threshold (low uptake), where dense fibrous tissue was identified in histology in advance to get the corresponding averaged FDG uptake. Histologists then recorded all plaque components shown proximately within each sample square in the corresponding matched histologic sections. The recorded plaque components included fibrous tissue, calcification, loose extracellular matrix, lipid core, lipid pool, intraplaque hemorrhage, organizing/organized thrombus, granulocytes, neovasculature and inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes and/or foam cells). The total number of co-localized inflammatory cell types were also recorded.

Histology-driven analysis

In a second, histology-driven analysis, regions with specific components were first identified by a histologist blinded to PET. The reader selected points on histology and recorded the components present in that region (Fig. 1). Components were limited to those found to be associated with uptake in the PET-driven analysis (p < 0.2). Fibrous tissue (as the reference) and calcification (as the negative control) were also carefully selected as to not be too close to other components, while other areas were permitted to have multiple co-localized components (e.g. co-localized macrophages and neovasculature).

For each point identified on histology, the mean standard uptake value (SUV) for each 2 mm × 2 mm region of interest (ROI) centered at each identified point (red square in Fig. 1b) was recorded automatically using the matched PET images. Pixels outside the artery wall boundary were excluded from the averaging. The SUV of each pixel was calculated as

Statistical analysis

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used for the PET-driven and histology-driven analyses (SPSS, version 21). For the PET-driven analysis, regions with high and low FDG uptake were analyzed using a logistic GLMM with high/low uptake as the dependent variable and plaque components as the independent variables. Each region could contain 0, 1 or more plaque components. For the histology-driven analysis, the dependent variable was meanSUV (a continuous variable), so a linear mixed model (LMM) was used. As with the PET-driven analysis, each region could contain multiple plaque components on histology. In all models, a random intercept term was included for each plaque to adjust for the overall uptake of the plaque and account for the repeated measurements per plaque. In the PET-driven analysis, all observations were included in each model. In the histology-driven analysis, each model included only observations with either fibrous tissue (the reference or fixed model intercept) or the other plaque components in the model. The significance level was set as 0.05.

For both analyses, univariate models were analyzed first by only including one plaque component as the independent variable one time. Then multivariate models were analyzed which included all plaque components as independent variables (except fibrous tissue) found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis. For the PET-driven analysis, the resulting regression coefficients correspond to odds ratios (OR) of having high versus low FDG uptake based on the presence or absence of each component. For the histology-driven analysis, the regression coefficients correspond to the mean increase or decrease in meanSUV seen when each component was present compared to the meanSUV of fibrous tissue.

As an exploratory analysis, the inflammatory cell infiltrate was divided into subgroups by cell type (macrophages, lymphocytes, and foam cells) and by the number of cell types present (INF1, INF2 or INF3), where INF3 represents the most complex type of inflammatory cell infiltrate with all three types of inflammatory cells co-localized. In a multivariate model, the single overall inflammation variable was replaced by these separate inflammatory subgroup variables to determine whether uptake associations varied by subtype.

Results

All fourteen subjects successfully underwent FDG injection and carotid endarterectomy. All plaques were imaged by MRI and microPET imaging. At histology examination one specimen was found to have a prominent xanthoma and was excluded from further analysis. FDG injections occurred 1.37 ± 0.38 h prior to endarterectomy and the time interval between FDG injection and PET scanning was 2.45 ± 0.52 h.

PET-driven analysis

Three plaques that did not contain any high uptake samples on PET were excluded due to model requirements. They were however used for the subsequent histology driven analysis.

Within the ten remaining plaques, there were 131 high uptake regions and 98 low uptake regions. Table 1 summarizes the plaque components found in both groups (only shows components with more than five counts). In the univariate GLMM models, only regions of inflammatory cell infiltrate (OR = 6.93, p < 0.001) and neovasculature (OR = 5.57, p < 0.001) were significantly more likely to be present in high uptake regions compared with low FDG uptake regions, while calcification (OR = 0.54, p = 0.044) and fibrous tissue (OR = 0.56, p = 0.043) were more likely to be in low uptake regions. All inflammatory cell subgroups tended to be positively associated with high uptake regions. Based on a multivariate model, regions of inflammatory cell infiltrate (OR = 5.95, p < 0.001) and neovasculature (OR = 4.09, p = 0.008) were independently associated with high FDG uptake.

Histology-driven LMM analysis

Based on the PET-driven analysis, inflammatory cell infiltrates, neovasculature, loose extracellular matrix were chosen as possible features associated with high FDG uptake. Therefore, these features, as well as fibrous tissue and calcification were identified in the histology-driven portion of the analysis. In total, 319 ROIs from 13 patients were selected.

Table 2 summarizes the histology-driven analysis results. The univariate analysis found that all components were significantly associated with meanSUV. The multivariate analysis found that regions of inflammatory cell infiltrate (p = 0.001) and loose extracellular matrix (p = 0.001) were independently associated with enhanced FDG uptake while neovasculature (p = 0.157) was no longer significant after adjusting for the other components. In addition, calcification (p = 0.004) was negatively associated with FDG uptake.

Further subgroup analysis of the inflammatory cell groups showed that meanSUV tended to be higher than fibrous tissue when either macrophages (p = 0.020), foam cells (p = 0.007) or lymphocytes (p = 0.065) were present (Table 3). In addition, meanSUV tended to increase intensively when all three inflammatory cell types were present (p < 0.001; Fig. 2). Elevation of meanSUV was not significant when only a single inflammatory cell type was present (p = 0.325).

Increased meanSUV of inflammatory cells subgroups. The increased meanSUV of inflammatory cells subgroups compared with fibrous tissue (meanSUV = 1.21) in multivariate histology-driven analysis (Table 3). INF3 (complex inflammatory cell infiltrates) had the highest FDG uptake among these groups. INFn means n types of inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes and foam cells) were co-localized in one ROI. *p < 0.001

Discussion

The primary finding of this study largely confirms prior reports that inflammatory cells (macrophages and foam cells) lead to enhanced FDG uptake in atherosclerotic plaque. The study further establishes the specificity of this relationship as it showed a one-to-one relationship between regions with inflammatory cell infiltrate and regions with enhanced FDG uptake. Additionally, the study showed that complex inflammatory cell infiltrates with co-localized macrophages, lymphocytes and foam cells, had the highest FDG signal.

This study included several unique aspects beneficial for furthering the link between inflammation and FDG uptake. First, ex vivo microPET allowed accurate localization of PET signals. Second, injection of the PET tracer immediately prior to surgery allowed in vivo delivery of the FDG agent. Third, the use of a bidirectional analysis allowed us to establish that areas of inflammatory cell infiltrate showed enhanced FDG uptake, and the corollary, that regions of enhanced uptake were more likely to contain inflammatory cell infiltrates than areas of low uptake.

Physiologically, macrophages have much higher rate of glucose uptake than neighboring cell types [13]. Our study, which co-localized macrophages with enhanced FDG uptake areas, confirmed previously observed positive correlations between FDG uptake and macrophages both in vivo and in vitro [5, 6, 8, 14]. For instance, Tawakol et al. [8] demonstrated a significant correlation (r = 0.70, p < 0.0001) between FDG-PET signal of carotid plaque and the presence of macrophages (CD 68 positive) in corresponding histology specimens from seventeen patients; Rudd et al. [5] found the majority of deoxyglucose accumulated in macrophage-rich areas in excised carotid plaque specimens incubated with deoxyglucose in vitro.

Furthermore, our finding that foam cells have enhanced FDG uptake is as expected, considering that foam cells are formed by macrophages internalizing modified LDL which is energy consuming [15]. This is also supported by a previous in vitro study which demonstrated that early stages of foam cell formation had enhanced FDG uptake by using cultured mouse peritoneal macrophages [16]. Foam cell accumulation at an early stage of atherosclerosis, known as the “fatty streak” [15, 17], is a hallmark of atherosclerosis. The co-localization of foam cells with regions of enhanced FDG uptake may explain the observation of focal enhanced FDG uptake areas in arteries without obvious vessel wall thickening, and also suggests the potential ability of FDG-PET in detecting initial plaque lesions.

In this study, complex inflammatory cell infiltrates with co-localization of lymphocytes, macrophages and foam cells had significantly higher FDG-PET signal than areas with only one or two types of inflammatory cells. This is as expected, as the presence of all three types of inflammatory cells would be presumed to have more activity [15]. For example, activated macrophages can activate T lymphocytes and activated T lymphocytes secrete cytokines, which can further recruit and activate more macrophages. Activated inflammatory cells are very energy-consuming [15].

Regions of calcification had reduced FDG uptake, although one would expect there to be no uptake at all. However, calcification in the carotid plaque is often fragmented containing live cells between the calcium fragments which may account for the signal. Furthermore, there has been controversy regarding the FDG non-specific binding with calcification. For example, Laitinen et al. [9] found that FDG uptake in calcified area in LDLR/ApoB48 knockout mice was significantly higher than healthy arteries using autoradiography and that FDG co-localized with calcification in human plaque samples in vitro. But these findings contradict numerous observations in humans demonstrating the rare overlap of FDG uptake and calcification in both in vivo studies [18–20] and ex vivo studies [11]. In addition, the in vitro result from Laitinen et al. is not conclusive due to the small human sample size and in vitro incubation environment.

Loose extracellular matrix was associated with enhanced FDG uptake independently in the histology-driven analysis, due to the presence of active smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts which produce extracellular matrix. Although normal smooth muscle cells are not associated with enhanced FDG uptake in many studies [6], it has been noted that smooth muscle cells have increased glucose uptake when exposed to pro-inflammatory cytokines [21]. In atherosclerosis, the inflammatory response can stimulate the migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells [15], which is an energy-consuming process.

Regions of neovasculature were found to have a significant independent positive association with high FDG uptake in the PET-driven analysis and the univariate histology-driven analysis. Enhanced FDG uptake in regions of neovasculature may be related to endothelial cells lining the neovessels [22] which are known to have an increased rate of glucose uptake caused by atherogenic stimuli [21], in addition to the increased density of inflammatory cells often observed surrounding the neovessels [23].

Although the association of loose extracellular matrix and neovasculature with enhanced FDG uptake were not always significant in both PET-driven and histology-driven analyses, perhaps due to the small sample size, they consistently showed association with enhanced FDG uptake.

Our study further promoted the clinical application of FDG-PET in vulnerable plaque assessment by localizing enhanced FDG signal with plaque components. FDG has been shown to bind to a variety of activated cells. Identifying these activated cells in a plaque may point to activity which may lead to vulnerablility. Based on our bidirectional analysis, bright FDG signal in clinical FDG-PET scans can be attributed to inflammation, especially complex inflammation, with possible contribution from loose extracellular matrix and neovasculature. Active inflammation and neovasculature are key features for vulnerable plaques [15]; the co-localization of loose extracellular matrix and enhanced FDG uptake is also probably due to exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines [21]. Therefore, enhanced FDG uptake in FDG-PET represent the co-localized vulnerable plaque components. And the higher FDG uptake, the more aggressive therapy methods may be required. However, further research using a clinical PET scanner and standardized protocol [24] is needed to quantify the FDG uptake for treatment decision making.

Study limitations

While significant effort was taken to register the PET, MRI and histology specimens, mis-registration may have contributed to error, particularly in areas of more subtle FDG uptake. MeanSUV over a 2 mm × 2 mm region was utilized for each ROI to minimize the mis-registration effect. The study sample size was relatively small. Nonetheless, significant associations between specific plaque features and patterns of FDG uptake were observed. Lastly, although multivariate linear mixed models were introduced to analyze the independent FDG contribution of components, the fact that components are co-localized did not allow for the complete exclusion of effects from adjacent cells.

Conclusions

This study, using generalized linear mixed models, showed that in vivo uptake of FDG corresponded to regions of inflammatory cell infiltrate in human carotid atherosclerotic plaque, particularly, complex inflammatory cell infiltrates with co-localized macrophages, lymphocytes and foam cells. The use of high-resolution microPET also revealed FDG uptake in other plaque components such as loose extracellular matrix and neovasculature. The overlay of FDG-PET signal with serially sectioned and matched histology validated that FDG uptake had good correlation with the active components of the human atherosclerotic plaque.

References

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S (2014) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation 129(3):e28–e292. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80

Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J, Badimon JJ, Stefanadis C, Moreno P, Pasterkamp G, Fayad Z, Stone PH, Waxman S, Raggi P, Madjid M, Zarrabi A, Burke A, Yuan C, Fitzgerald PJ, Siscovick DS, de Korte CL, Aikawa M, Juhani Airaksinen KE, Assmann G, Becker CR, Chesebro JH, Farb A, Galis ZS, Jackson C, Jang IK, Koenig W, Lodder RA, March K, Demirovic J, Navab M, Priori SG, Rekhter MD, Bahr R, Grundy SM, Mehran R, Colombo A, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne C, Insull W Jr, Schwartz RS, Vogel R, Serruys PW, Hansson GK, Faxon DP, Kaul S, Drexler H, Greenland P, Muller JE, Virmani R, Ridker PM, Zipes DP, Shah PK, Willerson JT (2003) From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: part I. Circulation 108(14):1664–1672. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000087480.94275.97

McCarthy MJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM, Jones L, London NJM, Bell PRF, Naylor AR, Brindle NPJ (1999) Angiogenesis and the atherosclerotic carotid plaque: an association between symptomatology and plaque morphology. J Vasc Surg 30(2):261–268. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(99)70136-9

Figueroa AL, Subramanian SS, Cury RC, Truong QA, Gardecki JA, Tearney GJ, Hoffmann U, Brady TJ, Tawakol A (2012) Distribution of inflammation within carotid atherosclerotic plaques with high-risk morphological features a comparison between positron emission tomography activity, plaque morphology, and histopathology. Circ-Cardiovasc Imaging 5(1):69–77. doi:10.1161/Circimaging.110.959478

Rudd JHF (2002) Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation 105(23):2708–2711. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000020548.60110.76

Tawakol A, Migrino R, Hoffmann U, Abbara S, Houser S, Gewirtz H, Muller J, Brady T, Fischman A (2005) Noninvasive in vivo measurement of vascular inflammation with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Nucl Cardiol 12(3):294–301. doi:10.1016/j.nuclcard.2005.03.002

Tarkin JM, Joshi FR, Rudd JH (2014) PET imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 11(8):443–457. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2014.80

Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Bashian GG, Bedri S, Vermylen D, Cury RC, Yates D, LaMuraglia GM, Furie K, Houser S, Gewirtz H, Muller JE, Brady TJ, Fischman AJ (2006) In vivo 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 48(9):1818–1824. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.076

Laitinen I, Marjamaki P, Haaparanta M, Savisto N, Laine VJ, Soini SL, Wilson I, Leppanen P, Yla-Herttuala S, Roivainen A, Knuuti J (2006) Non-specific binding of [18F]FDG to calcifications in atherosclerotic plaques: experimental study of mouse and human arteries. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 33(12):1461–1467. doi:10.1007/s00259-006-0159-6

Sheikine Y, Akram K (2010) FDG-PET imaging of atherosclerosis: do we know what we see? Atherosclerosis 211(2):371–380. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.002

Masteling MG, Zeebregts CJ, Tio RA, Breek JC, Tietge UJ, de Boer JF, Glaudemans AW, Dierckx RA, Boersma HH, Slart RH (2011) High-resolution imaging of human atherosclerotic carotid plaques with micro 18F-FDG PET scanning exploring plaque vulnerability. J Nucl Cardiol 18(6):1066–1075. doi:10.1007/s12350-011-9460-2

Kerwin W, Alessio A, Ferguson M, Hatsukami T, Caldwell J, Miyaoka R, Kohler T, Yuan C (2012) High-resolution [18]fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography and coregistered magnetic resonance imaging of atherosclerotic plaque from a patient undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Circ-Cardiovasc Imaging 5(5):683–684. doi:10.1161/Circimaging.112.975144

Leppanen O, Bjornheden T, Evaldsson M, Boren J, Wiklund O, Levin M (2006) ATP depletion in macrophages in the core of advanced rabbit atherosclerotic plaques in vivo. Atherosclerosis 188(2):323–330. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.017

Deichen JT, Prante O, Gack M, Schmiedehausen K, Kuwert T (2003) Uptake of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in human monocyte-macrophages in vitro. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30(2):267–273. doi:10.1007/s00259-002-1018-8

Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340(2):115–126. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901143400207

Ogawa M, Nakamura S, Saito Y, Kosugi M, Magata Y (2012) What can be seen by F-18-FDG PET in atherosclerosis imaging? The effect of foam cell formation on F-18-FDG uptake to macrophages in vitro. J Nucl Med 53(1):55–58. doi:10.2967/jnumed.111.092866

Libby P (2012) Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32(9):2045–2051. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179705

Dunphy MP, Freiman A, Larson SM, Strauss HW (2005) Association of vascular 18F-FDG uptake with vascular calcification. J Nucl Med 46(8):1278–1284

Tatsumi M, Cohade C, Nakamoto Y, Wahl RL (2003) Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the aortic wall at PET/CT: possible finding for active atherosclerosis. Radiology 229(3):831–837. doi:10.1148/radiol.2293021168

Menezes LJ, Kotze CW, Agu O, Richards T, Brookes J, Goh VJ, Rodriguez-Justo M, Endozo R, Harvey R, Yusuf SW, Ell PJ, Groves AM (2011) Investigating vulnerable atheroma using combined (18)F-FDG PET/CT angiography of carotid plaque with immunohistochemical validation. J Nucl Med 52(11):1698–1703. doi:10.2967/jnumed.111.093724

Folco EJ, Sheikine Y, Rocha VZ, Christen T, Shvartz E, Sukhova GK, Di Carli MF, Libby P (2011) Hypoxia but not inflammation augments glucose uptake in human macrophages: Implications for imaging atherosclerosis with 18fluorine-labeled 2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 58(6):603–614. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.044

Doyle B, Caplice N (2007) Plaque neovascularization and antiangiogenic therapy for atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 49(21):2073–2080. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.089

Kumamoto M, Nakashima Y, Sueishi K (1995) Intimal neovascularization in human coronary atherosclerosis—its origin and pathophysiological significance. Hum Pathol 26(4):450–456. doi:10.1016/0046-8177(95)90148-5

Gholami S, Salavati A, Houshmand S, Werner TJ, Alavi A (2015) Assessment of atherosclerosis in large vessel walls: A comprehensive review of FDG-PET/CT image acquisition protocols and methods for uptake quantification. J Nucl Cardiol 22(3):468–479. doi:10.1007/s12350-015-0069-8

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jie Sun for his valuable discussions of pathology, and Zach Miller for his help on the manuscript. This study was funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant Number R21HL106061). This material is the result of work supported by resources from the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Kerwin is an employee of Presage Biosciences. Mr. Hippe has received grants from GE Healthcare. Dr. Alessio has received research support from GE Healthcare. Dr. Hatsukami has received grants from Philips Healthcare. Dr. Yuan holds grants from the NIH and Philips Healthcare. He also serves as a Member of Radiology Advisory Network, Philips. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships to disclose.

Ethical standard

All human and animal studies have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Kerwin, W.S., Caldwell, J.H. et al. High resolution FDG-microPET of carotid atherosclerosis: plaque components underlying enhanced FDG uptake. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 32, 145–152 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-015-0739-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-015-0739-2