Abstract

Purpose

Several studies indicate that sexual minority (e.g., bisexual, lesbian) women may be at an increased risk for breast cancer. However, we know little about how risk factors, such as benign breast disease (BBD)—which can confer nearly a fourfold breast cancer risk increase—may vary across sexual orientation groups.

Methods

Among Nurses’ Health Study II participants followed from 1989 to 2013 (n = 99,656), we investigated whether bisexual and lesbian women were more likely than heterosexual women to have breast cancer risk factors including a BBD diagnosis (self-reported biopsy or aspiration confirmed, n = 11,021). Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Compared to heterosexuals, sexual minority participants more commonly reported certain breast cancer risk factors including increased alcohol intake and nulliparity. However, sexual minority participants were more likely than heterosexuals to have certain protective factors including higher body mass index and less oral contraceptive use. When evaluating age- and family history-adjusted rates of BBD diagnoses across sexual orientation groups, bisexual (HR 1.04, 95% CI [0.78, 1.38]) and lesbian (0.99 [0.81, 1.21]) women were just as likely as heterosexuals to have a BBD diagnosis. Results were similar after adjusting for other known breast cancer risk factors.

Conclusions

In this cohort of women across the U.S., sexual minorities were more likely than heterosexuals to have some breast cancer risk factors—including modifiable risk factors such as alcohol intake. Heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women were equally as likely to have a BBD diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Emerging research shows sexual minority (e.g., bisexual, lesbian) women are at an increased risk for breast cancer compared to heterosexual women [1]. Data have been limited to explore the origin of these disparities since sexual orientation measures are not collected in cancer registries [2, 3]. Recently, researchers have used different approaches to overcome this dearth of data. For example, researchers have documented that geographic areas with a greater density of lesbian women have a higher incidence of breast cancer [4]. Prediction models reveal lesbian women have a higher probability of developing breast cancer compared to their heterosexual sisters [5]. In regards to breast cancer mortality, women in same-sex households appear more likely to die from breast cancer compared to women in different-sex households [6].

Compared to heterosexual women, sexual minority women may have an adverse risk factor profile for breast cancer including more nulliparity, alcohol use, and obesity compared to heterosexual women [7,8,9,10,11,12]. However, it is unclear how these risk factors as well as others such as benign breast disease (BBD)—which can confer a significant breast cancer risk increase—may vary across sexual orientation groups. Certain BBD subtypes, such as proliferative BBD, are associated with nearly a fourfold increase in breast cancer risk [13]. Therefore, it is important that sexual orientation-related disparity research examine BBD, including different subtypes. Sexual minorities could be at an increased risk for BBD through a number of pathways. In part due to the stress of experiencing discrimination, sexual minority adolescents are more likely than heterosexuals to use alcohol [14] and less likely to be physically active [15,16,17], two risk factors for BBD [18, 19].

We used data from a large U.S. longitudinal cohort study to examine breast cancer risk factors and BBD diagnoses across sexual orientation groups. Longitudinal cohort studies with substantial statistical power and high-quality assessments of sexual orientation and cancer endpoints are the best way to fill existing research gaps. Such studies provide the empirical evidence needed to develop public health interventions and offer data that are difficult for cancer registries to collect, such as self-reported alcohol intake. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine sexual orientation in relation to the risk of BBD.

Methods

Study population

Data were drawn from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), a prospective cohort study that began in 1989 when female nurses aged 25 to 42 years completed questionnaires about their health. Follow-up questionnaires continue to be sent biennially. The cumulative follow-up on each questionnaire cycles is over 90%. Of the 116,429 participants at baseline, we excluded 14,716 participants who did not complete either questionnaire on which sexual orientation was assessed (described below), and we also excluded 1,655 participants who completed such a questionnaire but skipped the sexual orientation measure. Additionally, the current analysis was limited to participants who reported their sexual orientation as heterosexual, bisexual, or lesbian so we excluded 402 additional participants who endorsed other responses (e.g., “prefer not to respond”), resulting in a total sample size of 99,656. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required.

Measures

Sexual orientation

In 1995 and 2009, the following measure was included on the NHSII questionnaire, after being pilot tested [20]: “Whether or not you are currently sexually active, what is your sexual orientation or identity? (Please choose one answer). (1) Heterosexual, (2) Lesbian, gay, or homosexual, (3) Bisexual, (4) None of these, (5) Prefer not to answer.” For these analyses, we used the most recent report of sexual orientation from 2009 but if these data were missing, we imputed (e.g., carried forward) the 1995 response. Sexual orientation groups were modeled as heterosexual (reference), bisexual, or lesbian. To increase statistical power, we conducted sensitivity analyses by modeling sexual orientation in different ways such as combining bisexual and lesbian participants into a single sexual minority group.

Benign breast disease

Starting on the baseline questionnaire in 1989 and continuing on each subsequent questionnaire, participants reported any physician diagnosis of fibrocystic or other BBD as well as whether the diagnosis was confirmed by biopsy and/or aspiration. We also requested biopsy samples from a subsample of the participants with self-reported diagnoses between 1993 and 2003. Study pathologists conducted independent blinded review of the biopsy samples and classified BBD lesions according to the Dupont and Page criteria [21] as: non-proliferative, proliferative without atypia, and proliferative with atypia (atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia).

To maximize statistical power in the sexual orientation subgroups, the primary outcome for this analysis was self-reported biopsy and/or aspiration confirmed BBD. Within the subsample of participants who provided biopsy samples, we conducted secondary analyses of the biopsy-confirmed BBD categories (combined and separately) of: (1) non-proliferative; and (2) proliferative (with and without atypia). Secondary analyses also examined BBD among participants with and without a mammogram as well as among participants with and without a family history of breast cancer.

Covariates

Potential confounders included age (months) and family history of breast cancer in a mother or sister (assessed in 1989, 1997, 2001, 2005, and 2009). Sensitivity analyses were conducted that adjusted for other known BBD risk factors, which could lie on the causal pathway between sexual orientation and BBD (e.g., age at menarche [< 12, 12, 13, 14, > 14 years], body mass index [BMI] at age 18 years [< 18.5, 18.5–22.4, 22.5–24.9, 25–29.9, ≥ 30], weight change since age 18 years [pounds], alcohol intake [no alcohol, < 5, 5–10, > 10 g/day], adolescent alcohol intake [no alcohol, < 5, 5–10, > 10 grams/day], height [meters], oral contraceptive use [never, past, current], parity [i.e., pregnancies ≥ 20 weeks gestation; nulliparity, 1–2, ≥ 3 children], age at first birth [years], total duration of breastfeeding across all pregnancies [< 1, 1–3, 3–12, > 12 months], hormone therapy use [none, oral estrogen, oral estrogen plus progesterone, other formulations], and menopausal status [premenopausal, postmenopausal]). If any covariate data were missing, we imputed data from previous years.

Statistical analysis

Participants contributed person-time from baseline in 1989 until return of the most recent questionnaire in 2015. Women were then followed from entry into the cohort until biopsy and/or aspiration confirmed BBD or death. Cox proportional hazards models were stratified by calendar time with age (months) as the timescale to calculate the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of developing BBD. The Lunn and McNeil [22] approach was used to compare different BBD categories to account for competing risks. The proportional hazard assumption was assessed using a likelihood ratio test for the interaction between sexual orientation and age.

Results

Of the 99,656 participants in our sample, 98.7% (n = 98,315) identified as heterosexual, 0.4% (n = 415) as bisexual, and 0.9% (n = 926) as lesbian (see Table 1). Compared to heterosexuals, bisexual and lesbian participants more commonly reported certain breast cancer risk factors including taller height and higher alcohol intake (current and during adolescence, all p < 0.0008). The largest sexual orientation difference in breast cancer risk factors related to parity with bisexuals (51%) and lesbians (74%) being more likely than heterosexuals (30%) to be nulliparous. In contrast, bisexual and lesbian participants were more likely than heterosexuals to have certain protective factors against breast cancer including higher body mass index, less oral contraceptive use, and a younger age at first birth (all p < 0.0001). There were no sexual orientation differences (p > 0.05) in family history of breast cancer, weight change since age 18 years, age at menarche, menopausal status, or hormone therapy use. Additionally, there were no sexual orientation differences in breastfeeding duration (among parous women) but when parity is considered, sexual minorities have less of this protective factor.

A total of 11,021 participants self-reported they had biopsy or aspiration confirmed BBD (see Table 2). Study pathologists reviewed biopsy specimens from a subset of these cases (n = 2,004) to classify lesions as either non-proliferative (n = 671) or proliferative (including with and without atypia; n = 1,333).

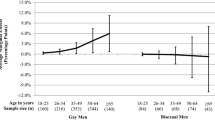

When evaluating rates of BBD diagnoses across sexual orientation groups, bisexual (HR 1.04, 95% CI [0.78, 1.38]) and lesbian (0.99 [0.81, 1.21]) women were just as likely as heterosexuals to have a BBD diagnosis. These estimates were consistent even after adjusting for known breast cancer risk factors. Additionally, there were no differences by sexual orientation in BBD subtype. These estimates were all similar in all sensitivity analyses where we combined bisexual and lesbian participants, where we restricted to participants with a mammogram, where we stratified by those with and without a family history of breast cancer, and where we adjusted for other known BBD risk factors.

Discussion

For almost 20 years, the Institute of Medicine [23, 24] has warned of a potential elevated breast cancer risk among sexual minorities. Without information on sexual orientation in cancer registries, researchers have had to apply novel methodological approaches to examine potential disparities. For the current analyses, we leveraged longitudinal cohort data from women across the U.S. and we found that bisexual as well as lesbian women were more likely than heterosexual women to have some breast cancer risk factors though also more likely to have some protective factors. However, heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women were equally as likely to have a BBD diagnosis.

A previous analysis in the NHSII cohort revealed that sexual minority participants appeared to be at an increased risk of breast cancer. Austin et al. used the Rosner–Colditz Risk Prediction Model to identify significantly elevated rates of breast cancer risk in both bisexual (mean predicted 1-year breast cancer incidence rate ratio, 1.10; 95% CI 1.10, 1.10) and lesbian women (1.06; 95% CI 1.06, 1.06) compared with heterosexual women [25]. It is now imperative that we identify contributing risk factors to these potential breast cancer disparities.

Research on other sexual orientation-related cancer disparities have focused on established risk factors like nulliparity, obesity, and alcohol [7,8,9]. One systematic review [8] pooled the prevalence estimates of risk factors from seven independent surveys of bisexual and lesbian women to compare with national estimates (likely based on samples predominantly of heterosexual women). In alignment with the current findings, bisexual and lesbian women in the NHSII sample had a higher prevalence of a number of breast cancer risk factors compared to heterosexual women.

Our study did not identify sexual orientation differences in BBD diagnoses. This could happen for a number of reasons. There truly may not be sexual orientation differences or we may not have been able to observe these differences due to methodological limitations. While the large sample size of NHSII was powerful, it may not have been large enough to detect small effect estimates. Second, our measure of sexual orientation was limited to capturing participants’ sexual orientation identity and did not assess the two other dimensions of sexual orientation (i.e., sex of sexual partners and sex of romantic attractions). As a result, participants who identify as heterosexual but who also have had same-sex partners or same-sex romantic attractions were included in the reference group, which may have biased our results towards the null. Future research should explore breast cancer risk factors, including BBD diagnoses, across all three dimensions of sexual orientation. Sexual minority women consistently report employment discrimination and less healthcare access than heterosexual women [26,27,28] but results have been mixed on sexual orientation-related mammography screening utilization; some results—including from NHSII [29]—indicate sexual minority women are less likely to undergo screening [8, 9, 30] while there are no sexual orientation differences in other samples [31, 32]. Given that BBD is often diagnosed through mammography, disparities in healthcare access may lead to an underestimate of BBD among sexual minority women. However, when we restricted our results to participants who reported mammography, the results did not substantially change.

Our study is the first to our knowledge to examine sexual orientation and BBD, but there are a number of limitations. This sample included only nurses and was limited in terms of racial/ethnic diversity. While our findings may not generalize to other populations, the homogeneous nature of this sample is also a strength in that confounding—such as by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity—is reduced. However, it is critical that future research examine sexual orientation differences among non-nursing populations who may have less access to healthcare as well as more racially/ethnically diverse populations, particularly given the known racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer [33]. While NHSII is a large cohort, we do not yet have enough cases to investigate disparities in breast cancer across sexual orientation groups. Future research on BBD and breast cancer should also explore protective factors that may be more or less common among sexual minorities such as chemoprevention and reduction mammoplasty, on which we had limited data. We also lacked detailed family history data other than breast cancer diagnoses among the participants’ mother or sisters; future work could explore a broader definition with the inclusion, for example, of daughters. These limitations were countered by the high-quality disease data including the role of experienced breast pathologists in defining BBD outcomes as well as the review of biopsy samples. Findings were also strengthened by various sensitivity analyses including restricting analyses to women with mammograms to address any potential sexual orientation disparities in screening and detection. In the first study to investigate the association between sexual orientation and risk of BBD, our approach was also strengthened by our ability to adjust for time-varying covariates.

While we did not identify disparities in BBD diagnoses between sexual minority and heterosexual women, a number of breast cancer risk factors were different between sexual orientation groups. Targeted interventions are needed to reduce the elevated breast cancer risk factors among sexual minorities including alcohol use, which may be contributing to breast cancer disparities. Additionally, sexual minorities face unique issues, such as employment discrimination, resulting in less access to health insurance which may result in less mammographic screenings compared to heterosexuals [26,27,28]. Therefore, more work is needed to help sexual minority women overcome the many barriers they face in accessing care and reducing their breast cancer risk. Without such changes, sexual minorities may continue to be disproportionately burdened by breast cancer.

References

Meads C, Moore D (2013) Breast cancer in lesbians and bisexual women: systematic review of incidence, prevalence and risk studies. BMC Public Health 13:1127

Bowen DJ, Boehmer U (2007) The lack of cancer surveillance data on sexual minorities and strategies for change. Cancer Causes Control 18:343–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-007-0115-1

Brown JP, Tracy JK (2008) Lesbians and cancer: an overlooked health disparity. Cancer Causes Control 19:1009–1020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-008-9176-z

Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Timm A (2011) County-level association of sexual minority density with breast cancer incidence: results from an ecological study. Sex Res Soc Policy 8:139–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-010-0032-z

Dibble SL, Roberts SA, Nussey B (2004) Comparing breast cancer risk between lesbians and their heterosexual sisters. Womens Heal Issues 14:60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2004.03.004

Cochran S, Mays V (2012) Risk of breast cancer mortality among women cohabiting with same sex partners: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2003. J Womens Heal 21:528–533. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.3134

Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ et al (2004) Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Womens Heal 13:1033–1047. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2004.13.1033

Cochran S, Mays V, Bowen D et al (2001) Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health 91:591–597

Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T et al (2000) Sexual orientation and health: comparisons in the women’s health initiative sample. Arch Fam Med 9:843–853

Zaritsky E, Dibble SL (2010) Risk factors for reproductive and breast cancers among older lesbians. J Women’s Heal 19:125–131. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2008.1094

Rankow EJ (1995) Breast and cervical cancer among lesbians. Womens Health Issues 5:123–129

Kavanaugh-Lynch MHE, White E, Daling JR, Bowen DJ (2002) Correlates of lesbian sexual orientation and the risk of breast cancer. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc 6:91–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOLA.0000011064.00219.71

Dyrstad SW, Yan Y, Fowler AM, Colditz GA (2015) Breast cancer risk associated with benign breast disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 149:569–575

Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R et al (2008) Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction 103:546–556

Mereish EH, Poteat VP (2015) Let’s get physical: sexual orientation disparities in physical activity, sports involvement, and obesity among a population-based sample of adolescents. Am J Public Health 105:1842–1848. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302682

Beach LB, Turner B, Felt D et al (2018) Risk factors for diabetes are higher among non-heterosexual US high-school students. Pediatr Diabetes 19:1137–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12720

Calzo JP, Roberts AL, Corliss HL et al (2014) Physical activity disparities in heterosexual and sexual minority youth ages 12–22 years old: roles of childhood gender nonconformity and athletic self-esteem. Ann Behav Med 47:17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9570-y

Liu Y, Tamimi RM, Berkey CS et al (2011) Adolescent intakes of alcohol and folate and risk of proliferative benign breast disease. J Clin Oncol 29:169–169. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.29.27_suppl.169

Berkey CS, Tamimi RM, Willett WC et al (2014) Adolescent physical activity and inactivity: a prospective study of risk of benign breast disease in young women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 146:611–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-3055-y

Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ et al (2006) Disclosure of sexual orientation and behavior in the Nurses’ Health Study II: results from a pilot study. J Homosex 51:13–31. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n01_02

Dupont WD, Page DL (1985) Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med 312:146–151. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198501173120303

Lunn M, McNeil D (1995) Applying cox regression to competing risks. Biometrics 51:524–532

Graham R, Berkowitz B, Blum R, Bockting W, Bradford J, de Vries B, Makadon H (2011) The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Institute of Medicine, Washington (DC)

Solarz AL (1999) Lesbian health: current assessment and directions for the future. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian Health Research Priorities, Washington (DC).

Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Rosner B et al (2012) Application of the Rosner-Colditz risk prediction model to estimate sexual orientation group disparities in breast cancer risk in a U.S. cohort of premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 21:2201–2208. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0868

Przedworski JM, McAlpine DD, Karaca-Mandic P, VanKim NA (2014) Health and health risks among sexual minority women: an examination of 3 subgroups. Am J Public Health 104:1045–1047. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301733

Austin EL, Irwin JA (2010) Health behaviors and health care utilization of southern lesbians. Womens Heal Issues 20:178–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2010.01.002

Buchmueller TC, Carpenter CS (2012) The effect of requiring private employers to extend health benefit eligibility to same-sex partners of employees: evidence from California. J Policy Anal Manage 31:388–403. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21603

Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Nichols LP et al (2013) An examination of sexual orientation group patterns in mammographic and colorectal screening in a cohort of U.S. women. Cancer Causes Control 24:539–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9991-0

Kerker BD, Mostashari F, Thorpe L (2006) Health care access and utilization among women who have sex with women: sexual behavior and identity. J Urban Health 83:970–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-006-9096-8

Brandenburg DL, Matthews AK, Johnson TP, Hughes TL (2007) Breast cancer risk and screening: a comparison of lesbian and heterosexual women. Women Heal 45:109–130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v45n04_06

Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ (2010) A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health 100:1953–1960. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169

DeSantis CE, Ma J, Goding Sauer A et al (2017) Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state. CA Cancer J Clin 67:439–448. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21412

Acknowledgments

Dr. Charlton was supported by Grant MRSG CPHPS 130006 from the American Cancer Society. Dr. Austin was supported by R01HD057368 and R01HD066963 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Austin was additionally supported by Grants T71MC00009 and T76MC00001 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. The Nurses’ Health Study II was supported by UM1CA176726 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study II for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charlton, B.M., Farland, L.V., Boehmer, U. et al. Sexual orientation and benign breast disease in a cohort of U.S. women. Cancer Causes Control 31, 173–179 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01258-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01258-z