Abstract

Although previous research has examined the effectiveness of various levels of punitive reactions to misconduct, researchers have given leader leniency relatively inadequate attention. Prior studies consistently suggest the beneficial effects of reacting less punitively toward misconduct. The current research challenges this notion by delineating a mixed effect of leader leniency on subordinate psychological and behavioral reactions. Building on social exchange theory (i.e., reciprocity norm and rank equilibration norm) and motive attribution literature, the authors argue that when subordinates hold high levels of instrumental motive attribution, leader leniency relates positively to subordinate psychological entitlement, which in turn leads to workplace deviance. In contrast, when subordinates develop high levels of value-expressive motive attribution, leader leniency is positively associated with their felt obligation toward leaders, which positively influences their subsequent organizational citizenship behavior. The results of a field study, a scenario experiment, and a recall experiment conducted to test these hypotheses confirm the double-edged effects of leader leniency. These findings have important implications for theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employee misconduct that violates moral principles or performance standards is ubiquitous in organizations (Treviño, 1992), and the managerial role of leaders requires them to exert influence to mitigate these undesirable behaviors (Podsakoff et al., 2006; Sims, 1977). Accordingly, some leaders take punitive measures to inhibit inappropriate subordinate behaviors. However, in line with recent research that has emphasized less punitive reactions toward subordinate misconduct as a kind of leader virtue and responsibility (Caldwell & Dixon, 2010; Cameron & Caza, 2002; Ferch & Mitchell, 2001), other leaders engage in leniency—“the act of lessening or even removing the prescribed negative consequences for misconduct” (Zipay et al., 2021, p. 351). Considering that leader behaviors should serve as a reinforcer to modify subordinates’ undesirable conduct (Podsakoff, 1982; Podsakoff et al., 2006), understanding how subordinates who engage in misconduct (i.e., wrongdoers) react to leniency is particularly necessary. However, extant literature largely employs the grantor perspective and recommends kindhearted reactions to employee misconduct (e.g., Bies et al., 2016; Zipay et al., 2021), perhaps neglecting wrongdoers’ reactions to these less punitive decisions (Adams et al., 2015).

Another small literature stream has posited that reacting less punitively toward employee misconduct can generate a host of benefits for wrongdoers. For example, managers’ less punitive responses can evoke wrongdoers’ prosocial perceptions or emotions (e.g., perspective taking, guilt), facilitate their interpersonal citizenship behaviors and physical health, and help wrongdoers reintegrate into their work units (Bertels et al., 2014; Fehr & Gelfand, 2012; Hannon et al., 2012). This imbalanced investigation of benefits has led to a dearth of studies investigating the potential drawbacks of managers’ less punitive measures. But research shows that being punitive can rectify wrongs and inhibit future misconduct (Ball et al., 1994; Butterfield et al., 1996; Podsakoff & Todor, 1985; Treviño & Ball, 1992), so reacting less punitively might encourage wrongdoers’ continued activity. However, few studies address whether leader leniency leads to negative outcomes for subordinates charged with wrongdoing and, if so, when and why this leniency can be beneficial versus detrimental. Developing a balanced theory of implications of leader leniency from the wrongdoer’s perspective can offer more nuanced answers to the aforementioned questions, as well as challenge the prevailing premise that leaders’ less punitive actions are always beneficial (Bies et al., 2016). Practically, we advise practitioners to take the costs of being lenient into account and accordingly take appropriate steps to alleviate these negative effects.

To this end, this research integrates social exchange theory with motive attribution literature to investigate the mixed effects of leader leniency on wrongdoers’ outcomes. We theorize that subordinates charged with wrongdoing develop distinct psychological and behavioral reactions toward leader leniency, depending on their interpretations of it. Building on motive attribution literature (Heider, 1958) and the functional theory of attitudes (Katz, 1960), we differentiate instrumental versus value-expressive motive attributions to leader leniency. Instrumental motive attribution is the extent to which subordinates ascribe leader leniency to instrumental ends (e.g., benefit maximization, loss minimization; Qin et al., 2018), whereas value-expressive motive attribution refers to the extent to which subordinates perceive leader leniency as a result of value expression (e.g., core value reflection, maintenance of principles; Qin et al., 2018).

When subordinates attribute high levels of instrumental motives to their leaders, they believe that leaders show leniency to achieve certain goals; thus, they understand their relative importance and value to their leaders’ achievement of benefits. In turn, they tend to develop perceptions of exaggerated self-worth; in line with rank equilibration norm (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Meeker, 1971), they then experience high levels of psychological entitlement and exhibit more workplace deviance that reflects their entitlement feelings. In contrast, when subordinates display high levels of value-expressive motive attribution, they tend to understand leader leniency as a sign of leaders’ inner selves and thus perceive kindheartedness and benevolence. These subordinates are more likely to acknowledge the value associated with leader leniency and obey reciprocity norms (Gouldner, 1960), then experience a sense of felt obligation, which leads to increased organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) to return the favor of leniency. Therefore, we suggest that leader leniency has a double-edged sword effect on subordinate deviance and OCB, through two distinct mechanisms, contingent on whether subordinates attribute instrumental or value-expressive motives to leader leniency (see Fig. 1).

Our research contributes to leniency literature in several ways. First, researchers have examined less punitive reactions, such as forgiveness and compassion (e.g., Bies et al., 2016; Dutton et al., 2014), but these responses differ substantially from leader leniency because forgiveness depict one’s psychological state whereas leniency is behavior (Zipay et al., 2021). Few studies consider wrongdoers’ reactions to leniency either. By adopting the subordinate’s (i.e., wrongdoer’s) perspective, we seek to uncover the consequences of leader leniency. Second, prior research exclusively identifies the beneficial outcomes of reacting less punitively (Bies et al., 2016), perhaps unintentionally neglecting its potential costs. With more nuanced theory, we seek to capture both the benefits and perils of leader leniency and provide a more fine-grained picture of leader leniency. Third, we propose instrumental and value-expressive motive attributions as a way to reconcile contrasting subordinate reactions to leader leniency, which not only highlights the important role of subordinates’ understanding of leader behaviors in their reactions to leader leniency but also explains paradoxical subordinate reactions. Fourth, drawing on the reciprocity norm (Gouldner, 1960) and rank equilibration norm (Meeker, 1971), we identity felt obligation and psychological entitlement as two pathways that can explain the positive and negative effects of leader leniency. In so doing, we offer novel insights into wrongdoers’ psychological states when they encounter leader leniency. Fifth, our research contributes to social exchange theory, which we leverage to develop our model. Previous studies mostly use reciprocity norms to explain organizational phenomena, leaving other exchange norms neglected (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). By simultaneously introducing reciprocity and rank equilibration norms to explore a single organizational phenomenon (i.e., wrongdoers’ reactions to leader leniency), we hope to inspire scholars pay more attention to other exchange norms in their efforts to understand organizational management phenomena.

Theory Development and Hypotheses

Motive Attributions for Leader Leniency

Leadership literature suggests that how subordinates react to leader behaviors is determined by the motives they attribute to these behaviors (Martinko et al., 2007). Across a variety of research domains, pertaining to leader justice behavior (e.g., Matta et al., 2020), abusive supervision (e.g., Yu & Duffy, 2021), and humble leadership (Qin et al., 2020) for example, scholars increasingly focus on the role of subordinate motive attributions to explain reactions to leaders’ behaviors. Subordinates infer why leaders treat them in a specific way, then use these inferences to interpret and understand observable leader behaviors (Leung et al., 2001). Therefore, it is meaningful to examine how subordinates’ attribution of leader leniency influences their psychological and behavioral responses to leader lenient behaviors.

The functional theory of attitudes (Katz, 1960) indicates that people engage in certain behaviors to either benefit themselves in an economic manner (i.e., instrumental motivation) or signal their core values and self-concepts (i.e., value-expressive motivation). This theoretical framework provides a motivational foundation for understanding behaviors like justice (Qin et al., 2018) or volunteering (Clary et al., 1998). We argue that leader leniency is driven by either instrumental or value-expressive motivations, and subordinates can perceive and assess these motivations. As Heider (1958) describes, people also attempt to attribute motives to interpret beneficial (or harmful) interpersonal interactions. Although they often have difficulty precisely capturing others’ intentions, they can leverage informational clues provided by observable behaviors to understand others’ motives (Maierhofer et al., 2000); people tend to behave in alignment with their motives (Muir et al., 2022). Consequently, we conclude that subordinates care about and look for cues to make causal inferences about leader leniency.

In detail, we propose that subordinates make two forms of leniency motive attributions: instrumental and value-expressive. An instrumental motive attribution assumes that leader leniency is a way for leaders to achieve their own personal self-interests. Leaders usually rely on important employees (e.g., high performers) to achieve personal goals (e.g., completing management tasks, high performance), and they might offer preferential treatment, such as additional resources and favors (Kim & Glomb, 2014; Wayne & Ferris, 1990), in exchange for their commitment and hard work. Less punitive reactions to misconduct also can contribute to wrongdoers’ reintegration into work units, positive emotions, and appropriate behaviors (e.g., Bertels et al., 2014; Fehr & Gelfand, 2012). Thus, leaders likely exhibit leniency toward high-value employees to maximize benefits (Boise, 1965; Rosen & Jerdee, 1974). People with instrumental values may provide cues, based on the nature or timing of their behaviors (Grant & Mayer, 2009; Hui et al., 2000), and subordinates may use such information to interpret leader leniency as a way to achieve instrumental ends (i.e., instrumental motive attribution).

With a value-expressive motive attribution, subordinates instead ascribe leader leniency to expressions of inner values and ideals. Some philosophers underscore the righteousness and nobleness of leniency (Rainbolt, 1990), and several religions highlight the moral value of responding less punitively to misconduct (McCullough & Worthington, 1999); in this sense, leniency can help signal a leader’s care and virtuousness (Butterfield et al., 1996). Moreover, being lenient can be influenced by beliefs and self-concepts (Bies et al., 2016), such that some people’s beliefs about justice cause them to react less punitively to others’ misconduct (Karremans & Van Lange, 2005), and leaders may withhold punishments out of concern for subordinates (Butterfield et al., 1996). During daily encounters, subordinates have many opportunities to interact with their leaders, and these interactions help them judge whether leniency is an expression of their inner self. As a result, subordinates might form value-expressive motive attributions for leader leniency.

Social Exchange Perspective on Leader Leniency

Social exchange theory suggests how people engaged in repeated exchanges behave when they are bestowed with benefits by their exchange partners (Blau, 1964). Multiple norms (i.e., reciprocity, rationality, altruism, rank equilibration, or competition) govern interpersonal exchanges, and these norms can operate simultaneously but independent of one another (Meeker, 1971). In the case of leader leniency, we predict that reciprocity and rank equilibration norms serve as underlying drivers to help subordinates counterbalance their psychological and behavioral responses toward leader leniency. Moreover, social exchange theory highlights that people rely on informational cues to determine their reactions to exchange partners and thereby maximize the utility of their continued exchanges (Lawler & Thye, 1999; Wetzel et al., 2014). To this end, we integrate subordinate motive attribution literature with social exchange norms to tell two diverging tales about leader leniency.

Following reciprocity norms (Gouldner, 1960), people should repay and return benefits supplied by interactional partners. When subordinates see leniency as an expression of leader core values and self-concepts, they tend to perceive leaders as benevolent and accordingly develop obligation feelings, which motivates subordinates to display OCB to reciprocate leader leniency. In contrast, the rank equilibration norm suggests that benefits are allocated according to relative standing, without considering investments (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Meeker, 1971). When subordinates interpret leader leniency as motivated by instrumental reasons, they tend to realize their relative importance to their leaders’ interests. Consequently, these subordinates develop exaggerated feelings of self-worth and accordingly experience psychological entitlement, which causes them to display deviant behaviors to reflect their entitlement.

Rank Equilibration Norm: From Leader Leniency to Subordinate Deviance

We propose that when subordinates attribute leader leniency to instrumental motives, they develop perceptions of psychological entitlement. The term “psychological entitlement” captures a person’s sense that he or she “deserves more and is entitled more than others” (Vincent & Kouchaki, 2016, p. 1462). That is, entitled subordinates believe they should be treated uniquely and specially in social settings (Snow et al., 2001). When subordinates view their leaders’ lenient behaviors as stemming from a desire to benefit the leaders themselves, they see their significance and value in promoting leaders’ interests and thereby experience a sense of psychological entitlement.

Although leniency usually conveys benevolence information, considering that wrongdoers receive fewer negative consequences for their misconduct than might be expected (Zipay et al., 2021), subordinates’ perceptions of the underlying motivations play an important role in shaping their subsequent reactions. Because leaders often react less punitively toward high-value subordinates (Boise, 1965; Podsakoff, 1982; Rosen & Jerdee, 1974) who can help maximize their interests, subordinates should realize their importance in facilitating leaders’ interests when they perceive leader leniency as driven by instrumental reasons (i.e., promoting benefits or reducing losses). In addition, extant literature suggests that high-value relationships and high levels of power can predict grantors’ less punitive reactions (Bies et al., 2016; Fincham et al., 2006; Radulovic et al., 2019). Therefore, subordinates may interpret leader leniency as a signal of their relatively high value and power, which induces their inflated sense of power and amplified feelings of self-worth.

According to the rank equilibration norm of social exchange theory (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Meeker, 1971), perceptions of relatively higher value and power cause subordinates who engage in misconduct to interpret leader leniency as a special and deserved treatment. If these employees hold the belief that they deserve unique treatment based on their significance and relative power, they are more likely to experience psychological entitlement (Wetzel et al., 2014). However, when subordinates attribute a low level of instrumental motives to their leaders, they are less likely to attach leader leniency to their importance or value to the leader. In this case, they would not develop a sense that they should be treated uniquely and are less likely to experience psychological entitlement. Building on these arguments, we propose:

Hypothesis 1

The positive relationship of leader leniency and subordinate psychological entitlement is stronger when subordinate instrumental motive attribution is high (versus low).

Subordinate psychological entitlement also may lead to workplace deviance, which violates organizational norms and threatens the organization and its members’ wellbeing (Robinson & Bennett, 1995). In line with rank equilibration norms, entitled employees believe they deserve a better compensation or reward in consideration of their actual effort and contribution to organizations (Miller, 2009). When these unrealistic and amplified expectations for preferential treatment are not satisfied, entitled subordinates display negative responses and prioritize their own needs over others’ (Harvey & Martinko, 2009; Qin et al., 2020). For example, entitled subordinates are inclined to display deviant behaviors toward the organization (e.g., harm to its reputation) or its members (e.g., embarrassing coworkers) to satisfy their skewed notion of reciprocity and offset unmet needs. Consistent with these arguments, prior studies have indicated that psychological entitlement can cause employees to act selfishly (Zitek et al., 2010), display incivility toward others (Campbell et al., 2004), and engage in unethical or deviant behaviors in organizations (Qin et al., 2020; Yam et al., 2017). Together with our prediction that leader leniency interacts with subordinate instrumental motive attribution to influence psychological entitlement, we argue:

Hypothesis 2

The positive indirect effect of leader leniency on subordinate workplace deviance as mediated by subordinate psychological entitlement is stronger when subordinate instrumental motive attribution is high (versus low).

Reciprocity Norm: From Leader Leniency to Subordinate OCB

We argue that leader leniency also can evoke subordinates’ felt obligation, if they attribute leader leniency to value-expressive motives. Felt obligation refers to a feeling that one should care about others’ wellbeing and help others reach their goals (Eisenberger et al., 2001), which underlies the give-and-take norm and serves as an important ingredient in high-quality exchange relationships (Mossholder et al., 2005). As a prescriptive belief, felt obligation is elicited by others’ provision of favorable treatments (Gouldner, 1960). When subordinates attribute leader leniency to expressed value, they perceive benevolence and also likely experience feelings of obligation.

Felt obligation lies in the central tenet of reciprocity norms in social exchange theory, which is generated by exchanges of benefits and serves as an automatic reminder to reciprocate the good deed in social exchanges (Gouldner, 1960; Simmel, 1950). Leader leniency benefits subordinates by removing or lessening the punishment for their misconduct (Zipay et al., 2021), which should be viewed as a form of benevolence and facilitate subordinates’ felt obligation. However, not all received benefits engender positive reciprocity; recipients’ attributions of genuine action tendencies strongly shape their reciprocal intentions (Belmi & Pfeffer, 2015; Schopler & Thompson, 1968; Weinstein et al., 2010). Therefore, whether leader leniency evokes felt obligation among subordinates depends on the extent to which subordinates perceive it as motivated by sincere reasons. To this end, we take subordinates’ value-expressive motive attribution into consideration when investigating their reactions to leader leniency.

When subordinates ascribe leader lenient behaviors to leaders’ expressive values, they perceive leniency as driven by their leaders’ genuine care for subordinates (Butterfield et al., 1996) and regard it as a sign of leaders’ inner values and beliefs (e.g., benevolence, forgiveness; Bies et al., 2016). In such circumstances, subordinates tend to acknowledge leniency as generous and valuable and see lenient leaders as helpful and caring. As a result, the feeling of obligation is a likely response. In contrast, subordinates who attribute low levels of value-expressive motive to leniency are less likely to perceive genuine and altruistic motivations underlying lenient behaviors. The absence of sincere intention attribution causes subordinates to be less likely to recognize and value leader leniency, thereby discouraging their feelings of obligation. In support of these arguments, prior evidence shows that inferred instrumental motivations of helper can reduce recipients’ intention to reciprocate (Belmi & Pfeffer, 2015). Taken together, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3

The positive relationship of leader leniency and subordinate felt obligation is stronger when subordinate value-expressive motive attribution is high (versus low).

We next turn to the relationship between subordinates’ felt obligation and their OCB, which refers to discretionary behaviors that are not explicitly recognized by a formal reward system but that promote organizational efficiency, including behaviors directed at the organization and coworkers (Organ et al., 2006). According to reciprocity norms (Gouldner, 1960), felt obligation can function as a prescriptive belief to govern the reciprocal rules in social exchange relationships (Gouldner, 1960; Simmel, 1950). That is, felt obligation should propel individuals to “pay back” others’ favorable treatment to maintain a give-and-take balance, avoid violations of reciprocal norms, and preserve the high-quality exchange relationships (Mossholder et al., 2005). As a result, when subordinates experience feelings of obligation toward leader leniency, they are more likely to act beyond their role responsibilities and display OCB (Eisenberger et al., 2001; Thompson et al., 2020). Because leaders are agents of the organization and responsible for team outputs, thereby subordinates’ obligation feelings toward leaders can be a powerful linkage between subordinates and organizations or members in organizations (Zhang & Chen, 2013). As such, subordinates should display obligation through OCB directed at both the organization and coworkers to help leaders fulfill their role requirements. Corroborating these arguments, previous research notes that employees with more felt obligation would conduct general OCB directed at both leaders and coworkers/organizations to reciprocate leaders (e.g., Newman et al., 2017; Thiel et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2005). Combining this reasoning with Hypothesis 3, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4

The positive indirect effect of leader leniency on subordinate organizational citizenship behavior as mediated by subordinate felt obligation is stronger when subordinate value-expressive motive attribution is high (versus low).

Study 1: A Field Study

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected from a pharmaceutical company in eastern China. To ensure confidentiality, we used identification codes to match subordinates’ survey response across three waves and leader–subordinate responses. At Time 1, we invited subordinates to rate leader leniency and provide their demographic information. Two weeks later (Time 2), subordinates rated instrumental and value-expressive motive attributions of leader leniency, psychological entitlement, and felt obligation toward their leaders. At Time 3 (2 weeks after Time 2), we invited subordinates to report workplace deviance and their leaders to rate subordinates’ OCB. We invited a total of 248 employees and their direct leaders to participate voluntarily and distributed surveys to the 248 employees across three waves, after which we retained a final sample of 217 leader–subordinate dyads (i.e., 217 subordinates and 44 leaders), after pairing the surveys. Among the subordinates, 70.05% were male, they averaged 33.24 years of age (SD = 7.08), and they had worked with their leader for an average of 2.79 years (SD = 2.11). Among the leaders, 77.27% were male, they averaged 36.23 years of age (SD = 5.09), and they had an average of 5.34 years of managerial experience (SD = 4.71).

Measures

Following standard translation and back-translation procedures (Brislin, 1980), we translated the English-version scale into Chinese. Participants rated all measures using a five-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”).

Leader Leniency

To measure leader leniency, we adopted Zipay et al.’s (2021) three-item scale. A sample item was “My leader has given me at work a lighter punishment for my misconduct than he/she could have” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85). We explained misconduct and listed as examples lying, disrespectful treatment, and negligence, and then asked participants to report leader leniency toward their misconducts at work (Zipay et al., 2021).

Instrumental Motive Attribution of Leader Leniency

We adapted Qin et al.’s (2018) six-item measure of instrumental motive of justice behavior to assess subordinates’ instrumental motive attribution of leader leniency. Specifically, we framed the items as follows: “My leader engaged in lenient behaviors toward me because…,” and a sample item read “…because it enables him/her to maximize his or her own interests” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95).

Value-Expressive Motive Attribution of Leader Leniency

To measure value-expressive motive attribution of leader leniency, we adapted Qin et al.’s (2018) six-item measure of value-expressive motive of justice behavior. Similar to the instrumental motive attribution, we framed the items as follows: “My leader engaged in lenient behaviors toward me because…,” and a sample item was “…because it reflects his/her core values and beliefs” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93).

Psychological Entitlement

To measure psychological entitlement in Chinese contexts, we adopted Yam et al.’s (2017) four-item scale. A sample item was “I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

Felt Obligation

We assessed subordinates’ felt obligation using the four-item scale developed by Methot et al. (2016). A sample item was “I dedicate a significant amount of my energy to thinking about obligations I have to my leaders for his/her leniency” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89).

Workplace Deviance

We asked subordinates to report their deviant behaviors in the workplace using Bennett and Robinson’s (2000) nineteen-item scale. Sample items were “I made fun of someone at work” and “I took property from work without permission” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.99).

OCB

We adopted Lee and Allen’s (2002) sixteen-item scale to measure OCB. Sample items were “This subordinate helped others who have been absent” and “This subordinate attended functions that are not required but that help the organizational image” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97).

Control Variables

Following previous research, we controlled for employee age, gender, and leader–subordinate dyadic tenure, because these variables may affect subordinate deviance and OCB (Berry et al., 2007; Organ & Konovsky, 1989).

Analytic Strategy

Leaders reported subordinates’ OCB, and the data have a nested structure; therefore, a sandwich estimator strategy was used to analyze the data, as Muthén and Muthén (2017) suggest. Following Hayes (2013) and Preacher et al. (2007), we conducted a path analysis with robust maximum likelihood estimation to test the proposed relationships simultaneously. The independent and moderating variables were grand-mean centered to generate the interactive term. In addition, we used a Monte Carlo simulation (20,000 replications) in R software to construct the confidence intervals of the moderated mediation effects.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables and controls are displayed in Table 1. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to examine the distinctiveness of seven focal variables (i.e., leader leniency, instrumental motive attribution, value-expressive motive attribution, psychological entitlement, felt obligation, workplace deviance, and OCB). Considering the relatively small sample size (Bandalos, 2002), an item-to-construct balance method were applied to create eight parcels for OCB and nine parcels for workplace deviance (Little et al., 2002). The seven-factor model (i.e., three raw items for leader leniency, six raw items for instrumental motive attribution, six raw items for value-expressive motive attribution, four raw items for psychological entitlement, four raw items for felt obligation, eight parcel items for OCB, and nine parcel items for workplace deviance) exhibited a good fit with the data, χ2[719] = 1,682.40, p < 0.001, comparative fit index (CFA) = 0.91, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.08, which fit better than any alternative models with two of the seven factors combining into one factor (Δχ2[Δd.f. = 6] = 338.95 to 3798.89, ps < 0.001).

Hypotheses Tests

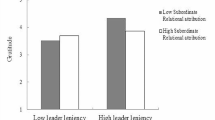

We employed a path analytic method to test the proposed model, and Table 2 contains the results. The interactive effect of leader leniency and instrumental motive attribution on psychological entitlement was significant (γ = 0.30, p < 0.01). As Aiken and West (1991) suggest (see Fig. 2), we conducted simple slope tests, which further revealed that this relationship was significant and positive when subordinates’ instrumental motive attribution of leader leniency was high (simple slope = 0.14, p < 0.05) and significant and negative when subordinates’ instrumental motive attribution of leader leniency was low (simple slope = − 0.23, p < 0.01). Thus, our data support Hypothesis 1. In support of Hypothesis 3, the interactive effect of leader leniency and value-expressive motive attribution on subordinates’ felt obligation toward leader was significant (γ = 0.26, p < 0.05). Simple slope tests (see Fig. 3) further indicated that this relationship was significant and positive when subordinates’ value-expressive motive attribution of leader leniency was high (simple slope = 0.17, p < 0.05) but was not significant when subordinates’ value-expressive motive attribution was low (simple slope = − 0.11, p > 0.05).

The Monte Carlo simulation (20,000 replications) results are presented at Table 3. Leader leniency had a negative indirect effect on workplace deviance through psychological entitlement when subordinate instrumental motive attribution was low (indirect effect = − 0.030, 95% CI = [− 0.08224, − 0.00037]), and had no effect on deviance when instrumental motive attribution was high (indirect effect = 0.018, 95% CI = [− 0.0238, 0.0457]). The difference of these effects included zero (indirect effect = 0.058) at the level of 95% CI ([− 0.0043, 0.1123]) but excluded zero at the level of 90% CI ([0.0032, 0.0693]). The indirect effect of leader leniency on OCB via felt obligation to leader was insignificant when subordinate value-expressive motive attribution was low (indirect effect = − 0.013, 95% CI = [− 0.0508, 0.0236]) and high (indirect effect = 0.020, 95% CI = [− 0.0117, 0.0655]), and the difference of these effects included zero (indirect effect = 0.032) at the level of 95% CI ([− 0.0007, 0.0803]) but excluded zero at the level of 90% CI ([0.0042, 0.1002]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 4 were almost supported.

Discussion

Study 1 uncovers the entitlement and obligation mechanisms translating leader leniency into subordinate deviance and OCB and highlights the role of different motive attributions in these processes. Although high in external validity of our field study, the field study design has data with the correlational nature, limiting the possibility to make causal inferences. To this end, a scenario experiment was conducted in Study 2 to address this limitation and examine the causality of our focal variables.

Study 2: A Scenario Experiment

Participants and Procedures

We conducted a scenario experiment via Prolific platform. A total of 290 full-time employees from United States and England completed the experiment and was paid $1.10 for each participant. We excluded 14 responses in the final analysis because these participants failed the two attention checks. Finally, we retained 276 participants; 48.55% were male, most of them (35.51%) had a bachelor degree, their average age was 39.49 years (SD = 11.23), and their work experience was 18.54 years (SD = 11.55). These participants worked in various industries, including manufacturing, finance, education, information technology and others.

We designed a 2 × 3 between-participants experimental design, with two levels of leader leniency (leniency vs. non-leniency) and three levels of attributions (instrumental motive attribution vs. value-expressive motive attribution vs. nonmanipulated attribution). As we cannot meaningfully manipulate attributions outside of leader leniency contexts, we followed the procedure in prior studies (see Leslie et al., 2012; Yu & Duffy, 2021) to create four conditions for the design (leader leniency + instrumental motive attribution, leader leniency + value-expressive motive attribution, leader leniency + nonmanipulated attribution, and no leader leniency + nonmanipulated attribution). Then, we randomly assigned participants to one of four conditions.

Our manipulations of leader leniency were based on the conceptualization, measurement and the open-ended survey results of leader leniency.Footnote 1 Specifically, we designed a work mistake incident vignette to manipulate leader leniency. And participants were instructed to read a short statement designed to manipulate instrumental motive attribution and value-expressive motive attribution of leader leniency (for similar research designs, see Qin et al., 2020; Skarlicki & Rupp, 2010). Experimental material could be found in the Appendix.

Measures

All scale measures were rated using 5-point Likert scales (from “1” = “strongly disagree” to “5” = “strongly agree”).

Felt Obligation

We used the same measures from Study 1 to measure felt obligation. We asked participants to report their current feelings toward the leader in the scenario. A sample item was “I dedicate a significant amount of my energy to thinking about obligations I have to the leader for his/her leniency” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92).

Psychological Entitlement

We used nine items developed by Campbell et al. (2004) to assess psychological entitlement (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). Also, participants were asked to report their current feelings after reading the scenario. A sample item was: “I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others”.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

OCB was rated using the same measures as in Study 1. We asked participants how likely they would engage in OCB. Sample items include “I would help others who have been absent” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93).

Workplace Deviance

Workplace deviance was rated with a ten-item scale used by Qin et al. (2020). We asked participants how likely they would display deviance behaviors. A sample item was: “I would insult someone about their job performance” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91).

Manipulation Checks

Employing manipulation checks in the main experiment might result in additional manipulations (Fayant et al., 2017; Tröster & Van Quaquebeke, 2021), thus we used an independent sample on Prolific to conduct manipulation checks. We randomly assigned participants to the four conditions as in our main experiment. We used three-item scale of leader leniency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94), six-item of instrumental motive attribution (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83), and six-item of value-expressive motive attribution (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) as in Study 1 to conduct our manipulation checks. Among the 73 participants, 65.75% were female, average age was 38.21 years (SD = 12.18). The results showed that participants reported more leniency in the leniency condition (M = 4.20, SD = 0.62) than in the non-leniency condition (M = 2.59, SD = 0.79), F(1,71) = 87.80, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.55, more instrumental motive attribution in the instrumental motive attribution condition (M = 3.78, SD = 0.44) than in other conditions (M = 3.16, SD = 0.65), F(1,71) = 15.31, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.18, and more value-expressive motive attribution in the value-expressive motive attribution condition (M = 4.05, SD = 0.57) than in other conditions (M = 3.50, SD = 0.55), F(1,71) = 11.15, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.14.

Results

We conducted a CFA on our measures of psychological entitlement, felt obligation to leader, workplace deviance, and OCB. An item-to-construct balance method was applied to create four parcels for OCB and three parcels for workplace deviance (Little et al., 2002). The four-factor model had exhibited a good fit to with the data (χ2[164] = 470.64, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.08), which fit better than all any alternative models, with two of the four factors combining to one factor (Δχ2[Δd.f. = 3] = 586.97 to 1082.91, ps < 0.001).

Descriptive statistics and correlations for Study 2 variables are presented in Table 1. Means and standard deviations by condition for our focal variables are shown in Table 4. To test Hypotheses 1 and 3, an ANOVA was conducted and the results indicated an overall significant effect of conditions on subordinate reactions—for psychological entitlement, F(3, 272) = 3.24, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.04, and for felt obligation, F(3, 272) = 4.08, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.04. In support of Hypothesis 1, subordinates in the leader leniency with instrumental motive attribution condition experienced significantly more psychological entitlement (M = 1.87, SD = 0.78) than did subordinates in the leader leniency with nonmanipulated attribution condition (M = 1.59, SD = 0.64), p < 0.05, or subordinates in the leader leniency with value-expressive motive condition (M = 1.55, SD = 0.62), p < 0.01, but subordinates in the leader leniency with instrumental motive attribution condition did not report significantly more entitlement than those in the no leader leniency condition (M = 1.79, SD = 0.82), p > 0.05. In support of Hypothesis 3, subordinates in the leader leniency with value-expressive motive attribution condition experienced significantly more felt obligation (M = 2.58, SD = 1.08) than did subordinates in the leader leniency with nonmanipulated attribution condition (M = 2.18, SD = 0.93), p < 0.05, or subordinates in the leader leniency with instrumental motive condition (M = 2.04, SD = 1.05), p < 0.01, or subordinates in the no leader leniency condition (M = 2.08, SD = 1.02), p < 0.01.

To test Hypotheses 2 and 4, we regressed deviance and OCB, respectively, on psychological entitlement and felt obligation, after controlling for the leader leniency and attribution conditions. The results suggest that psychological entitlement was significantly related to workplace deviance (b = 0.24, p < 0.01), but insignificantly related to OCB (b = − 0.08, p > 0.05), whereas felt obligation was significantly related to OCB (b = 0.19, p < 0.01), but insignificantly related to workplace deviance (b = − 0.03, p > 0.05). We then employed PROCESS macro to test our Hypotheses 2 and 4 and calculated 5000 bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. The results suggested that the indirect effect for the instrumental motive attributions through psychological entitlement was significant for deviance (indirect effect = 0.054, 95% CI = [0.007, 0.125]) and the indirect effect for the value-expressive motive attributions through felt obligation was significant for OCB (indirect effect = 0.084, 95% CI = [0.033, 0.149]). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 and 4 were supported.

Discussion

Study 2 further replicates Study 1 results and reinforces the notion that leader leniency can be both a benevolence and an indulgence for employees who have conducted wrongdoings. Despite that the controlled design can enhance causal patterns, it limits the type of misconduct to performance (i.e., the experimental context). Given misconduct involves different behaviors, a recall experiment was conducted in Study 3 to capture distinct types of real leader leniency behavior to enhance our results.

Study 3: A Recall Experiment

Participants and Procedures

We conducted a recall experiment via Prolific platform. We invited 228 full-time employees from England and the United States to participate in the experiment and paid each participant $1.05. Participants were asked to write a short essay to describe their leaders’ lenient reactions (high or low) toward their misconduct. We excluded 13 responses in the final analysis because these participants did not follow our instructions to write the essay about their leniency experience (e.g., some only type some numbers). Finally, we retained 215 participants; 39.53% were female, almost half of them (44.65%) had a bachelor’s degree, their average age was 40.43 years (SD = 15.10), and their work experience was 17.71 years (SD = 13.74). These participants worked in various industries, including real estate, health care, construction, information technology and others.

We randomly assigned participants to one of two conditions in which they were required to recall a recent high leader leniency event versus a low leader leniency event occurred in the workplace. A sample of high leader leniency response was: “One day, I was working as a nurse in a hospital, and I forgot to follow up on a patient’s request, which resulted in a delay in their treatment. When my supervisor found out about the mistake, instead of reprimanding me, she displayed lenient behavior towards my negligence. She listened to my explanation and offered me some tips on how to manage my workload better, which helped me to feel supported and motivated to do better in the future”. A sample of low leader leniency sample was: “I was heavily reprimanded and punished for letting someone leave without paying by accident. I was scolded and put on temporary suspension and this upset me greatly as I did not believe that it was completely my fault”. Following the recall task, participants completed our measures and manipulation checks.

Measures

All scale measures were rated using 5-point Likert scales (from “1” = “strongly disagree” to “5” = “strongly agree”). All motive attributions (i.e., instrumental and value-expressive motive attributions) and follow-up responses (i.e., entitlement, obligation, deviance, and OCB) were rated based on their recalled leader leniency experiences at that moment. Specifically, we added an instruction as follows: “Considering your leader’s behaviors you described above, please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements at that moment”.

We used the same measures from Study 2 for instrumental motive attribution (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92), value-expressive motive attribution (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86), psychological entitlement (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94), and felt obligation to leader (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

To reduce participants’ response burden after the writing task, we used the short-version of eight items developed by Dalal et al. (2009) to assess OCB (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85). A sample item was: “I went out of my way to be a good employee”.

Workplace Deviance

Similar to measures of OCB, we also used the short-version of eight items developed by Dalal et al. (2009) to assess deviance behavior. A sample item was: “I talked badly about people behind their backs” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86).

Manipulation Check

Three-item scale of leader leniency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93) as in Study 2 was used to conduct our manipulation check. Participants in the high leader leniency rated their described events more lenient (M = 3.99, SD = 0.86) than those in the low leader leniency condition (M = 2.15, SD = 0.94), F(1, 213) = 225.95, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.52. Therefore, these results suggested our manipulation were success.

Results

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and correlations of Study 3. We conducted a CFA on our focal variables before testing our hypotheses. An item-to-construct balance method was applied to create three parcels for value-expressive motive attribution, three parcels for instrumental motive attribution, three parcels for psychological entitlement, three parcels for OCB, and three parcels for workplace deviance (Little et al., 2002). The six-factor model had exhibited a good fit to with the data (χ2[137] = 314.24, p < 0.001,CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.08), which fit better than all any alternative models, with two of the six factors combining to one factor (Δχ2[Δd.f. = 5] = 248.75 to 557.93, ps < 0.001).

Path analyses were conducted to test our proposed moderation and moderated mediation effects. As shown in Table 6, leader leniency interacted with instrumental motive attribution to positively influence psychological entitlement (γ = 0.37, p < 0.05), and leader leniency interacted with value-expressive motive attribution to positively affect felt obligation to leader (γ = 0.32, p < 0.05). Simple slope analyses (see Fig. 4) further shown that the effects of leader leniency on psychological entitlement was positive and significant when instrumental motive attribution was high (simple slope = 0.86, p < 0.01) but not significant when instrumental motive attribution was low (simple slope = 0.20, p > 0.05). The effects of leader leniency on felt obligation to leader (see Fig. 5) was significant when value-expressive motive attribution was high (simple slope = 0.88, p < 0.01) but not significant when value-expressive motive attribution was low (simple slope = 0.36, p > 0.05). These results supported Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Furthermore, we employed 20,000 bootstrapping draws using Mplus version 7.4 to test our moderated mediation hypotheses. The results suggested that the indirect effect of leader leniency on deviance via entitlement was insignificant at low (indirect effect = 0.039, 95% CI = [− 0.048, 0.126]) levels of instrumental motive attribution, but was significant at high (indirect effect = 0.166, 95% CI = [0.035, 0.298]) levels of instrumental motive attribution, and the difference of these effects included zero (indirect effect = 0.127) at the level of 95% CI ([− 0.016, 0.271]) but excluded zero at the level of 90% CI ([0.007, 0.248]). And the indirect effect of leader leniency on OCB via felt obligation to leader was insignificant at both low (indirect effect = 0.042, 95% CI = [− 0.012, 0.096]) and high (indirect effect = 0.101, 95% CI = [− 0.001, 0.203]) levels of value-expressive motive attribution, and the difference of these effects was also not significant (indirect effect = 0.060, 95% CI = [− 0.024, 0.143]). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was almost supported but Hypothesis 4 was not supported.

General Discussion

For subordinates charged with wrongdoing, is leader leniency the “right” thing or “wrong” thing to do? To clarify this question, this research integrates social exchange theory with motive attribution literature to investigate the mixed effects of leader leniency on subordinate outcomes. Using a field study, a scenario experiment, and a recall experiment, we determined that leader leniency interacts with subordinate instrumental motive attribution and thereby engenders psychological entitlement, which in turn gives rise to workplace deviance. In contrast, when subordinates make value-expressive motive attributions of leniency, leader leniency contributes to subordinates’ felt obligation, which translates into OCB. Our findings have important theoretical implications related to leniency literature and practical implications for organizations.

Theoretical Implications

The current research contributes to leniency literature in several ways. First, compared with other less punitive reactions to misconduct, like forgiveness and compassion (e.g., Adams et al., 2015; Bies et al., 2016), leniency has received inadequate attention in work settings. Although Zipay et al. (2021) employ a grantor perspective to explore both the perils and benefits of leniency for grantors’ energy state, their research only partially answers the question of whether leniency is an effective tactic. Extending this line of research, we shift the focus from the grantor’s perspective to the wrongdoer’s perspective and specify leniency phenomena in leader–subordinate exchange contexts to examine how wrongdoers (i.e., subordinates) react to leader leniency. By addressing the concept of leader leniency, we also open new avenues for leniency research, which can enrich understanding of leniency in organizational contexts and especially leader–member encounters. Relatedly, this research employs a subordinate (i.e., wrongdoer) perspective to uncover the consequences of leader leniency, such that it complements previous studies of less punitive reactions, which predominantly center on grantors’ perspectives (Adams et al., 2015).

Second, we enrich leniency literature by uncovering the double-edged sword effects of leader leniency. Prior work on less punitive reactions to misconduct has captured a series of benefits for wrongdoers’ reactions, such as enhanced prosocial perceptions and emotions, increased interpersonal citizenship behaviors, and rehabilitation (Bertels et al., 2014; Fehr & Gelfand, 2012). Focusing on leader leniency, our work challenges the implicit premise that reacting less punitively is always beneficial. In addition, our model simultaneously examines both positive and negative subordinate reactions toward leader leniency. Drawing on social exchange theory (Gouldner, 1960; Meeker, 1971), we identify psychological entitlement and felt obligation toward leaders as diverging pathways that link leader leniency with subordinate workplace behaviors (i.e., deviance and OCB). By investigating the mixed-blessing effects of leader leniency on subordinate outcomes, we provide a more nuanced, balanced understanding of whether leader leniency should be encouraged or discouraged.

Third, our research contributes to theory on leniency by introducing motive attribution to leniency literature and identifying subordinate motive attribution as a boundary condition to explain subordinates’ differing reactions to leader leniency. Studies have emphasized that motives for being lenient strongly influence the outcomes and called for further investigations of leniency intentions (Zipay et al., 2021). To answer this call and develop our theory of subordinate reactions to leader leniency, this study goes a step further and applies functional theories of attitudes (Katz, 1960), such that we distinguish two forms of subordinate motive attributions for leader leniency: instrumental and value-expressive. A host of leadership literature has made use of this motive attribution approach, in relation to leader justice behaviors and abusive supervision (e.g., Matta et al., 2020; Yu & Duffy, 2021). We apply this approach to examine conditions in which subordinates react differently to leader leniency. In summary, our work answers previous calls to investigate leniency motivation and also emphasizes that the reasons behind leniency treatment are key to understanding subordinates’ reactions.

Fourth, the current research contributes to social exchange theory in work settings. Although it mostly has been leveraged to explain organizational phenomena, most studies center on reciprocity norms (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005), even though social exchange theory suggests that multiple rules govern exchange relationships, including negotiated, rationality, altruism, rank equilibration, and competition factors (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Meeker, 1971). We introduce felt obligation and psychological entitlement pathways that are rooted in reciprocity and rank equilibration norms to explain how subordinates develop counterbalancing psychological and behavioral reactions toward leader leniency. By doing so, we not only uncover two distinct sides of social exchanges for explaining subordinates’ reactions toward leader leniency but also identify a novel norm of social exchange (i.e., rank equilibration norm), which should be in organizational scholars’ interest.

Finally, our investigation of leader leniency contributes to moral psychology and business ethics literature. Leniency represents a benevolent reaction to misconducts, and the righteousness and nobleness of leniency have been acknowledged by many religion doctrines (e.g., Christianity and Islam) and philosophers (Rainbolt, 1990). As a result, the moral psychology view appraises leniency behaviors as congruent with moral bench mark, thereby praising leniency as a benevolent action. Zipay et al. (2021) supported this idea and found that being lenient to others’ misconducts can elicit the grantors’ pride that enhances engagement. Our research, adopting a wrongdoer’s perspective, further supports that leader leniency can serve as benevolence that induces employee OCBs through employee felt obligation. However, our research also suggests that leader benevolence can activate wrongdoers’ entitlement (i.e., a moral credentialing process, Yam et al., 2017), which in turn increase their workplace deviance behavior. Taken together, our research employs the wrongdoer approach to discuss whether leader leniency results in more prosocial behavior (i.e., employee OCB) or unethical behavior (i.e., workplace deviance), which would further promote our understanding of the righteousness of leniency. Moreover, our investigation of felt obligation and psychological entitlement represent two opposite moral psychology processes (i.e., moral obligation and moral credential), which enrich our understanding of double sword effects of leader leniency.

Practical Implications

Building on prior studies that suggest both punitive treatment and less punitive treatment to mitigate misconduct in organizations (e.g., Bies et al., 2016; Treviño, 1992), we provide a more fine-grained view about the complex effects of being less punitive following subordinate misconduct. Our results suggest that leader leniency can lead to either subordinate deviance or OCB through distinct pathways. Therefore, we advise organizations and leaders to employ a dialectical perspective to understand leader leniency when encountering subordinate misconduct events. That is, leaders can continue exhibiting leniency to reap its benefits (e.g., subordinate satisfaction, relationship effort), but they should be aware of the potential risk that leniency sometimes can become a kind of indulgence.

In addition, leader leniency can give rise to subordinate OCB by evoking their feelings of obligation when subordinates attribute leader leniency to value-expressive motivation, but it also induces subordinate deviance when it activates their psychological entitlement, because subordinates regard leader leniency as a result of instrumental motivation. These findings remind organizations and leaders to pay more attention to subordinates’ sensemaking of leader behaviors. To this end, organizations should launch training program to improve managers’ leadership and communication skills (Yu & Duffy, 2021), so they can effectively communicate their intentions. For example, leaders should be encouraged to take steps to communicate their values and moral responsibility to subordinates, to convey their internal self-concepts (Qin et al., 2018), but they should minimize the release of instrumental cues for their behaviors as much as possible. As a result, subordinates can interpret leaders’ lenient behaviors in a more positive light (e.g., value-expressive motive attribution) instead of negatively (e.g., instrumental motive attribution).

Limitations and Further Research

Our research has several limitations, which should be addressed in continued research. First, we have theorized and tested the role of motive attribution for leader leniency in affecting subordinates’ psychological and behavioral responses, but we still know little about why these attributions form. Perhaps individual characteristics and leader–subordinate relationships can shape these attribution processes. Subordinates whom leaders heavily depend on Kipnis (1972) and who are narcissistic (Treadway et al., 2019) tend to attach inflated personal value and importance to positive outcomes and accordingly anticipate highly instrumental motivations of leader leniency. In contrast, subordinates who trust their leaders are more likely to see leader leniency as an expression of inner values and self-concepts. Prior research indicates how a positive leader–subordinate relationship can contribute to subordinates’ positive attributions (Oh & Farh, 2017). Furthermore, we employ a wrongdoer (e.g., subordinate) perspective to develop theory and therefore emphasize subordinate motive attributions for leader leniency, but we cannot confirm the accuracy of subordinates’ motive attributions. In other words, we have not clarified whether leaders display lenient behaviors for the same reasons that subordinates attribute to them. A fruitful area for research would be to explore the alignments between leaders’ motives for leniency and subordinates’ attribution of these motives.

Second, because we adopt a wrongdoer perspective to depict how subordinates who engage in misconduct react to leader leniency in different motive attribution conditions, we fail to take observers’ reactions into consideration. Research on punishment literature has explored how observers (e.g., other team members) react to leader punishment (e.g., Atwater et al., 1998; Ball et al., 1994), but we find no such investigations in leniency research. Considering how observers develop emotions or perceptions toward grantors (e.g., leaders) and the leniency event would be worthwhile. For example, observers may perceive leaders who engage in leniency as powerless (or benevolent), thereby reducing (or increasing) their compliance or commitment to their leaders. A social justice perspective (Miller & Vidmar, 1981) suggests that observers also might sense anger or injustice when they see a coworker receive leniency, which could reduce their job satisfaction and performance (Ball et al., 1994).

Third, this research mainly focuses on the outcomes of leader leniency, and we encourage further research into its antecedents, from varying perspectives. From an instrumental perspective, subordinate performance or ingratiation (Liden & Maslyn, 1998), organizational rewards for leniency, and a lenient culture may motivate leaders to display lenient behaviors (Meyer et al., 2010); however, the requirements of their leadership role may restrain their lenient behaviors, considering that they are expected to address subordinates’ undesirable behaviors (Butterfield et al., 1996). Using a relationship lens, leader–member exchange quality can be a driver of leader leniency (Bauer & Green, 1996). Taking a morality approach, being lenient could be considered both a burden and a blessing for leaders. Studies have shown that being lenient can increase grantors’ pride and guilt experiences, which respectively replenish and deplete their energy resources (Zipay et al., 2021). Choosing between being a fair leader and being a benevolent leader might place leaders in a difficult misconduct management dilemma.

Fourth, an additional study could investigate how reactions to leader leniency change over time. Subordinates may feel obligated when their leaders mitigate or remove negative consequences of their first-time misconduct, but after a series of lenient actions, subordinates might develop some adaptions to these actions. According to adaption level theory, people combine prior stimuli to form adaption levels, which then sets a frame of reference for subsequent stimuli and induces them to respond indifferently (Helson, 1948). Therefore, subordinates may experience less obligation as the lenient treatment continues. In addition, an appropriateness framework suggests that employees’ interpretation of their social environment determines their psychological states and behaviors (Messick, 1999; Tenbrunsel & Messick, 1999). A series of leniency acts could lead employees to develop a knowledge structure that organizations will always ignore negative consequences and forgive misconduct. Consequently, leader leniency may encourage subordinates’ further deviant behaviors over time.

Conclusion

Integrating reciprocity and rank equilibration norms of social exchange theory with motive attribution literature, we develop and test the perils and benefits of leader leniency on subordinates’ psychological and behavioral reactions when they are charged with wrongdoing. We introduce instrumental and value-expressive motive attributions for leader leniency as boundary conditions that affect subordinate reactions to leader leniency. Accordingly, we identify psychological entitlement and felt obligation as two distinct pathways through which leader leniency can lead to subordinates’ deviance or OCB, contingent on their different motive attributions.

Data availability

The original data are not available to protect the anonymity of the participants of this study.

Notes

We collected an open-ended survey on Prolific to ask 139 participants recall their most recent experience with receiving leniency from their leaders, and we finally retained 117 incidents. Among these incidents, the most common incidents were work mistake (i.e., 35.04%), and other incidents involved late for work, longer break, organizational rules violation, and interpersonal offense.

References

Adams, G. S., Zou, X., Inesi, M. E., & Pillutla, M. M. (2015). Forgiveness is not always divine: When expressing forgiveness makes others avoid you. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 126, 130–141.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE.

Atwater, L. E., Dionne, S. D., Camobreco, J. F., Avolio, B. J., & Lau, A. (1998). Individual attributes and leadership style: Predicting the use of punishment and its effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(6), 559–576.

Ball, G. A., Treviño, L. K., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (1994). Just and unjust punishment: Influences on subordinate performance and citizenship. Academy of Management Journal, 37(2), 299–322.

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(1), 78–102.

Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1996). Development of leader–member exchange: A longitudinal test. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1538–1567.

Belmi, P., & Pfeffer, J. (2015). How “organization” can weaken the norm of reciprocity: The effects of attributions for favors and a calculative mindset. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1(1), 36–57.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360.

Berry, C. M., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 410–424.

Bertels, S., Cody, M., & Pek, S. (2014). A responsive approach to organizational misconduct: Rehabilitation, reintegration, and the reduction of reoffense. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(3), 343–370.

Bies, R. J., Barclay, L. J., Tripp, T. M., & Aquino, K. (2016). A systems perspective on forgiveness in organizations. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 245–318.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

Boise, W. B. (1965). Supervisors’ attitudes toward disciplinary actions. Personnel Administration, 28(3), 24–27.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Butterfield, K. D., Treviño, L. K., & Ball, G. A. (1996). Punishment from the manager’s perspective: A grounded investigation and inductive model. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1479–1512.

Caldwell, C., & Dixon, R. D. (2010). Love, forgiveness, and trust: Critical values of the modern leader. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 91–101.

Cameron, K., & Caza, A. (2002). Organizational and leadership virtues and the role of forgiveness. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 33–48.

Campbell, W. K., Bonacci, A. M., Shelton, J., Exline, J. J., & Bushman, B. J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29–45.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516–1530.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Dalal, R. S., Lam, H., Weiss, H. M., Welch, E. R., & Hulin, C. L. (2009). A within-person approach to work behavior and performance: Concurrent and lagged citizenship-counterproductivity associations, and dynamic relationships with affect and overall job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 1051–1066.

Dutton, J. E., Workman, K., & Hardin, A. E. (2014). Compassion at work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 277–304.

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42–51.

Fayant, M. P., Sigall, H., Lemonnier, A., Retsin, E., & Alexopoulos, T. (2017). On the limitations of manipulation checks: An obstacle toward cumulative science. International Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 125–130.

Fehr, R., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). The forgiving organization: A multilevel model of forgiveness at work. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 664–688.

Ferch, S. R., & Mitchell, M. M. (2001). Intentional forgiveness in relational leadership: A technique for enhancing effective leadership. Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(4), 70–83.

Fincham, F. D., Hall, J., & Beach, S. R. (2006). Forgiveness in marriage: Current status and future directions. Family Relations, 55(4), 415–427.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Grant, A. M., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Good soldiers and good actors: Prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 900–912.

Hannon, P. A., Finkel, E. J., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. E. (2012). The soothing effects of forgiveness on victims’ and perpetrators’ blood pressure. Personal Relationships, 19(2), 279–289.

Harvey, P., & Martinko, M. J. (2009). An empirical examination of the role of attributions in psychological entitlement and its outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(4), 459–476.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Heider, F. (1958). Psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley.

Helson, H. (1948). Adaptation-level as a basis for a quantitative theory of frames of reference. Psychological Review, 55(6), 297–313.

Hui, C., Lam, S. S. K., & Law, K. K. S. (2000). Instrumental values of organizational citizenship behavior for promotion: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 822–828.

Karremans, J. C., & Van Lange, P. A. (2005). Does activating justice help or hurt in promoting forgiveness? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(3), 290–297.

Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2), 163–204.

Kim, E., & Glomb, T. M. (2014). Victimization of high performers: The roles of envy and work group identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 619–634.

Kipnis, D. (1972). Does power corrupt? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(1), 33–41.

Lawler, E. J., & Thye, S. R. (1999). Bringing emotions into social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1), 217–244.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142.

Leslie, L. M., Manchester, C. F., Park, T. Y., & Mehng, S. A. (2012). Flexible work practices: A source of career premiums or penalties? Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1407–1428.

Leung, K., Su, S., & Morris, M. W. (2001). When is criticism not constructive? The roles of fairness perceptions and dispositional attributions in employee acceptance of critical supervisory feedback. Human Relations, 54(9), 1155–1187.

Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of leader–member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24(1), 43–72.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173.

Maierhofer, N. I., Griffin, M. A., & Sheehan, M. (2000). Linking manager values and behavior with employee values and behavior: A study of values and safety in the hairdressing industry. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(4), 417–427.

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Douglas, S. C. (2007). The role, function, and contribution of attribution theory to leadership: A review. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(6), 561–585.

Matta, F. K., Sabey, T. B., Scott, B. A., Lin, S. H. J., & Koopman, J. (2020). Not all fairness is created equal: A study of employee attributions of supervisor justice motives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(3), 274–293.

McCullough, M. E., & Worthington, E. L., Jr. (1999). Religion and the forgiving personality. Journal of Personality, 67(6), 1141–1164.

Meeker, B. F. (1971). Decisions and exchange. American Sociological Review, 36(3), 485–495.

Messick, D. M. (1999). Alternative logics for decision making in social settings. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 39(1), 11–28.

Methot, J. R., Lepine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & Christian, J. S. (2016). Are workplace friendships a mixed blessing? Exploring tradeoffs of multiplex relationships and their associations with job performance. Personnel Psychology, 69(2), 311–355.

Meyer, R. D., Dalal, R. S., & Hermida, R. (2010). A review and synthesis of situational strength in the organizational sciences. Journal of Management, 36(1), 121–140.

Miller, B. K. (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis of the equity preference questionnaire. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(4), 328–347.

Miller, D. T., & Vidmar, N. (1981). The social psychology of punishment reactions. In M. J. Lerner & S. C. Lerner (Eds.), The justice motive in social behavior (pp. 145–172). Plenum.

Mossholder, K. W., Settoon, R. P., & Henagan, S. C. (2005). A relational perspective on turnover: Examining structural, attitudinal, and behavioral predictors. Academy of Management Journal, 48(4), 607–618.

Muir, C. P., Sherf, E. N., & Liu, J. T. (2022). It’s not only what you do, but why you do it: How managerial motives influence employees’ fairness judgments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(4), 581–603.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Newman, A., Schwarz, G., Cooper, B., & Sendjaya, S. (2017). How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 49–62.

Oh, K. J., & Farh, C. (2017). An emotional process theory of how subordinates appraise, experience, and respond to abusive supervision over time. The Academy of Management Review, 42(2), 207–232.

Organ, D. W., & Konovsky, M. (1989). Cognitive versus affective determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(1), 157–164.

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (2006). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature, antecedents, and consequences. SAGE.

Podsakoff, P. M. (1982). Determinants of a supervisor’s use of rewards and punishments: A literature review and suggestions for further research. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 29(1), 58–83.

Podsakoff, P. M., Bommer, W. H., Podsakoff, N. P., & MacKenzie, S. B. (2006). Relationships between leader reward and punishment behavior and subordinate attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors: A meta-analytic review of existing and new research. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99(2), 113–142.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Todor, W. D. (1985). Relationships between leader reward and punishment behavior and group processes and productivity. Journal of Management, 11(1), 55–73.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Qin, X., Chen, C., Yam, K. C., Huang, M., & Ju, D. (2020). The double-edged sword of leader humility: Investigating when and why leader humility promotes versus inhibits subordinate deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(7), 693–712.

Qin, X., Ren, R., Zhang, Z. X., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Considering self-interests and symbolism together: How instrumental and value-expressive motives interact to influence supervisors’ justice behavior. Personnel Psychology, 71(2), 225–253.

Radulovic, A. B., Thomas, G., Epitropaki, O., & Legood, A. (2019). Forgiveness in leader–member exchange relationships: Mediating and moderating mechanisms. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(3), 498–534.

Rainbolt, G. W. (1990). Mercy: An independent, imperfect virtue. American Philosophical Quarterly, 27(2), 169–173.

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 555–572.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, T. H. (1974). Factors influencing disciplinary judgments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(3), 327–331.

Schopler, J., & Thompson, V. D. (1968). Role of attribution processes in mediating amount of reciprocity for a favor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10(3), 243–250.

Simmel, G. (1950). The sociology of Georg Simmel. Free Press.

Sims, H. P., Jr. (1977). The leader as a manager of reinforcement contingencies: An empirical example and a model. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership: The cutting edge. Southern Illinois University Press.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Rupp, D. E. (2010). Dual processing and organizational justice: The role of rational versus experiential processing in third-party reactions to workplace mistreatment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 944–952.

Snow, J. N., Kern, R. M., & Curlette, W. L. (2001). Identifying personality traits associated with attrition in systematic training for effective parenting groups. The Family Journal, 9(2), 102–108.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (1999). Sanctioning systems, decision frames, and cooperation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 684–707.

Thiel, C. E., Hardy, J. H., III., Peterson, D. R., Welsh, D. T., & Bonner, J. M. (2018). Too many sheep in the flock? Span of control attenuates the influence of ethical leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(12), 1324–1334.

Thompson, P. S., Bergeron, D. M., & Bolino, M. C. (2020). No obligation? How gender influences the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1338–1350.

Treadway, D. C., Yang, J., Bentley, J. R., Williams, L. V., & Reeves, M. (2019). The impact of follower narcissism and LMX perceptions on feeling envied and job performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(7), 1181–1202.

Treviño, L. K. (1992). The social effects of punishment in organizations: A justice perspective. Academy of Management Review, 17(4), 647–676.

Treviño, L. K., & Ball, G. A. (1992). The social implications of punishing unethical behavior: Observers’ cognitive and affective reactions. Journal of Management, 18(4), 751–768.

Tröster, C., & Van Quaquebeke, N. (2021). When victims help their abusive supervisors: The role of LMX, self-blame, and guilt. Academy of Management Journal, 64(6), 1793–1815.

Vincent, L. C., & Kouchaki, M. (2016). Creative, rare, entitled, and dishonest: How commonality of creativity in one’s group decreases an individual’s entitlement and dishonesty. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1451–1473.

Wang, H., Law, K. S., Hackett, R. D., Wang, D., & Chen, Z. X. (2005). Leader-member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 420–432.

Wayne, S. J., & Ferris, G. R. (1990). Influence tactics, affect, and exchange quality in supervisor–subordinate interactions: A laboratory experiment and field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(5), 487–499.