Abstract

Although performance pressure has desirable consequences, there is evidence that it can produce unintended outcomes as employees tend to engage in dysfunctional and unethical behaviors to meet performance goals. Thus, the process through which employees think and behave unethically under performance pressure deserves more research attention. This study goes beyond the stress-appraisal perspective and investigates whether and when performance pressure influences individual work mindsets and behaviors from a moral reasoning perspective. Specifically, we contend that performance pressure is related to employee expediency through moral decoupling. We further hypothesize dialectical thinking and moral identity to be the boundary conditions of the proposed relationships. Analyses of data from a field study in three waves provide support for most of the hypotheses. In particular, we find that moral decoupling accounts for additional variance after we control for the stress-appraisal effect of performance pressure on employee expediency. The study offers several contributions to the literature on performance pressure and unethical behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Organizations are facing considerable pressure to stay one step ahead of competitors in today’s dynamic and competitive environment. To maintain competitiveness, organizations often require employees to elevate their performance because employees’ contribution is the cornerstone of organizational performance. As a result, performance pressure is an inexorable experience for employees and a ubiquitous phenomenon in the workplace (Gilley et al., 2010; Spoelma, 2021; Welsh & Ordóñez, 2014). Performance pressure refers to employees’ perceptions of “the urgency to achieve high performance levels because performance is tied to substantial consequences” (Mitchell et al., 2019, p. 532). Research shows that employees under performance pressure are more likely to engage in task proficiency, citizenship behavior, and creative performance (e.g., Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2019) to meet organizational expectation (Gardner, 2012).

Despite the desirable consequences of performance pressure, scholars have raised concerns about its potential to trigger misconduct (Cialdini et al., 2004). Thus, uncovering the hidden dangers of performance pressure is important, especially as “tying performance metrics to strategy has become an accepted best practice over the past few decades” at many organizations (Harris & Tayler, 2019, p. 64). In particular, firms need to understand whether employees use short-term and unethical behaviors to meet performance goals, as such behaviors can lead to significant organizational costs in the long run. Wells Fargo’s cross-selling scandal is a typical example of this problem. The bank created a pressure-cooker culture that set unrealistic performance goals for employees (Egan, 2016; Eisen, 2020). Before the scandal was publicly known, senior bank executives continuously raised sales goals to unrealistic levels, and bank employees who failed to achieve those goals often lost their jobs or were excluded from their work teams (Flitter, 2020). Under such pressure, many employees opted for shortcuts and issued additional credit cards to customers without their permission because this option seemed to be an effective way to be regarded as good performers. To cover up the practice, some employees even forged signatures and created personal identification numbers for fake accounts. These accounts temporarily boosted sales numbers but ultimately led to huge fines for Wells Fargo, the loss of its hard-earned reputation, and prolonged efforts to redeem itself (Eisen, 2020; Harris & Tayler, 2019).

Given the dark side of performance pressure, scholars have recently investigated the relationship between performance pressure and employees’ misconduct or unethical behavior. For example, studies have shown that high performance pressure leads to workplace incivility (e.g., Jensen et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2019) and cheating (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2018; Spoelma, 2021). Considering performance pressure as a threatening aspect for employees, these studies have found that decreased self-regulation or increased self-protection plays an important role in explaining the dark side of performance pressure. Their findings provide some insights into how employees cope with performance pressure.

To extend this line of inquiry, we examine performance pressure from a motivated moral reasoning perspective (Ditto et al., 2009). Prior studies (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2018, 2019; Spoelma, 2021) have implicitly assumed that performance pressure provokes employees to disregard their moral principles in the process of decreased self-regulation and increased self-protection. While the separation of ethics and performance may allow employees to cope with performance goals, such a possibility has not received attention in the literature on performance pressure. As a motivated moral reasoning strategy, moral decoupling captures an individual’s selective dissociation of performance from morality and allows individuals to support transgressors’ high performance (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013; Fehr et al., 2019). Given these considerations, we suggest that motivated moral reasoning can advance the literature by introducing a moral perspective of performance pressure. Such a perspective is necessary because morality is still deemed an indispensable element in the assessment of employee performance (Gatewood & Carroll, 1991).

Specifically, drawing from the motivated moral reasoning perspective (Ditto et al., 2009), we examine the impact of performance pressure on employees’ use of a moral reasoning strategy (i.e., moral decoupling), or a specific moral-related work mentality in which they dissociate the goals of being an “excellent performer” from being a “moral person” (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013). We investigate whether moral decoupling connects performance pressure with employee expediency, defined as the “use of unethical practices to expedite work for self-serving purposes” (Greenbaum et al., 2018, p. 525). Expediency allows employees to cut corners to complete tasks and to alter numbers so that they can appear more successful than they are (Eissa, 2020). In addition, we explore contingencies for the morality-related explanation of performance pressure, because boundary conditions are necessary for a sound conceptual model (Thatcher & Fisher, 2022; Whetten, 1989). Because some people can deploy moral decoupling reasoning more steadily and often than others (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013; Fehr et al., 2019), we propose dialectical thinking (i.e., a cognitive tendency to endorse seeming contradictions) and moral identity (i.e., a self-concept prompting one to emphasize morality) as two potential moderators for the mediating effect of moral decoupling. Taken together, we argue that focusing on the moral reasoning perspective of performance pressure provides an alternative lens to enrich understanding of how employees cope with such pressure by adjusting their work mentality and behavior.

Our research makes several contributions to the literature on performance pressure, moral decoupling, and unethical behavior. First, it sheds light on whether employees can decouple morality in their pursuit of performance goals, an implicit assumption in prior studies on performance pressure (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2018, 2019; Spoelma, 2021). By controlling for the threat-appraisal effect (Mitchell et al., 2019), we demonstrate moral decoupling as a unique mechanism through which performance pressure is related to employee expediency. Second, while expediency is not as overt as other unethical behaviors, such as lying, theft, and mistreatment, it can lead to serious consequences for organizations (Eissa, 2020; Greenbaum et al., 2018). Despite many theoretical and business discussions on employee expediency, empirical investigations into the topic remain limited. Our focus on performance pressure adds to existing knowledge by testing whether organization-related factors can be antecedents of expediency. Third, we advance the moral perspective of performance pressure by exploring which types of employees can work under pressure without behaving unethically. Such an understanding is important for managers when using personality measures to screen employees who will face performance pressure (Mitchell et al., 2019).

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Research on unethical behavior has its origins in motivated moral reasoning theory, which suggests that individuals are motivated to reach a desirable moral conclusion (Ditto et al., 2009). Moral judgment is complex, multifaced, and deeply evaluative (Ditto et al., 2009), especially in work-related settings in which “obedience to authority, conformity to group, and maintenance of status quo” (Treviño, 1992, p. 446) are salient considerations. To protect the good moral character of the self and advance in the workplace, however, employees may be tempted to disregard their moral principles and adopt certain moral reasoning processes to protect their self-interest (Matute et al., 2021). In this research, we focus on moral decoupling, a distinct moral reasoning strategy, and argue that performance pressure influences expediency through moral decoupling.

Performance Pressure

Performance pressure is employees’ perception of the urgency of achieving high performance (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009). Employees who face performance pressure have a strong desire to continuously improve performance because they believe that exceeding organizational expectations will result in gains (e.g., promotions, benefits) while failing to do so will be detrimental to their careers (e.g., punishment, termination) (Mitchell et al., 2018, 2019). Putting pressure on employees to achieve superior performance is considered an effective way for organizations to motivate employees. For example, studies have shown that performance pressure stimulates employees to apply more diverse and higher-order skills, exert more energy on tasks, and thereby contribute to greater creativity (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009). Similarly, other research has found that when employees evaluate performance as a challenge, they are likely to draw on heightened self-resources and elevate work engagement, which in turn facilitate their task proficiency and citizenship behavior (Mitchell et al., 2019). At the team level, performance pressure can improve team performance (Gardner, 2012) and make team members more responsive to inclusive leadership (Ye et al., 2019).

Despite the bright side of performance pressure, it also has a dark side. In addition to workplace incivility (e.g., Jensen et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2019) and cheating (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2018; Spoelma, 2021), high performance pressure can diminish team performance by weakening team members’ domain-specific expertise, mental models, and transactional memory (Ellis, 2006; Gardner, 2012). High performance pressure can also attenuate the positive relationship between autonomy and employee engagement (Zhang et al., 2017).

Performance pressure can be intimidating and discomforting to employees. First, employees who face performance pressure know that their performance will be scrutinized in a high-demand and high-stakes manner (Gutnick et al., 2012). On the one hand, failure to meet demands may endanger employees’ continued employment and job security; on the other hand, it may weaken their social standing in the organization, increasing their risk of being excluded (Mitchell et al., 2018). As performance pressure increases, employees’ apprehension of impending assessment and potential punishment will also increase (Gardner, 2012). Second, experiencing performance pressure is threatening to employees because it is associated with the perception of performance inadequacy (Mitchell et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2017). That is, employees under performance pressure tend to believe that their current resources and performance are less than desirable. To achieve what is expected, they may need to stretch their capabilities, which can be a laborious task. As such, heightened performance difficulties become threatening stressors (Mitchell et al., 2019) and can lead to both resource depletion and an unpleasant affective state characterized by uncertainty and unease (Welsh & Ordóñez, 2014; Welsh et al., 2020). Because performance pressure is threatening, employees may feel compelled to achieve the required performance goals.

Although research has treated performance achievement and ethical conducts as integrated rather than competing goals (Gatewood & Carroll, 1991), studies have found that performance accountability can lead to ethical violations (Greenbaum et al., 2012; Jones & Ryan, 1998; Mitchell et al., 2018; Welsh & Ordóñez, 2014; Welsh et al., 2019). Under pressure to meet performance goals, employees may be tempted to make up performance lags or gain advantages through unethical means, especially if their capabilities or resources fall short of expectations to get the job done (Barsky, 2008; Quade et al., 2017; Welsh et al., 2019). Furthermore, the pressure to win may draw employees’ attention to protecting their self-interest and thereby make them feel less bound to adhere to moral standards regarding fairness (Mitchell et al., 2018; Schwieren & Weichselbaumer, 2010). Next, we introduce moral decoupling to describe a plausible moral reasoning strategy of employees working under performance pressure.

Moral Decoupling

Prior research suggests that moral decoupling can be either temporarily primed by seeing others engaging in moral decoupling or chronically activated through contextual cues such as performance goals (Fehr et al., 2019). Through moral decoupling, people do not necessarily modify their judgment of the immorality of someone’s wrongful acts but, at the same time, still view the person as nonetheless a high performer (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013; Haberstroh et al., 2017; Lee & Kwak, 2016). The exceptionally high performance of Tiger Woods and Kobe Bryant in sports can help explain why they have won so much public support, despite their extramarital affairs. Unlike moral disengagement, in which people feel less accountable for their unethical behaviors through rationalization, such as displacement of responsibility and devaluing of victims (Detert et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2012), moral decoupling allows employees to pay less attention to ethics-related concerns, enabling them to focus more on plausible actions conducive to performance enhancement (Haberstroh et al., 2017; Tenbrunsel & Messick, 1999).

Performance Pressure and Moral Decoupling

Performance and ethics are two important goals for employees to pursue in organizations (Quade et al., 2017; Welsh et al., 2019). Ethics can also be an important part of performance evaluation (Choi et al., 2013; James, 2000; Mortensen et al., 1989). However, the number of recent transgressions implies that employees’ perceptions of performance are not always linked to ethics (Cialdini et al., 2004). Some business organizations have awarded prestige to and heaped praise on actors based on their economic success rather than ethical adherence (Jones & Ryan, 1998).

Through a cognitive process of moral decoupling, employees can selectively disassociate or separate their judgments of performance from judgments of morality (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013). As mentioned previously, performance accountability makes employees believe that their compensation and promotion depend on whether they meet their performance goals (e.g., sales quotas, profit targets). Because employees are appraised by how well they perform, they are expected to pay less attention to the means through which these performance goals are met (Jones & Ryan, 1998), especially if the goals are difficult and urgent (Barsky, 2008; Schwepker & Ingram, 1996; Welsh et al., 2019). For example, salespeople who strive to increase sales revenue quickly may care little about behaving honestly toward customers.

To meet high performance requirements, employees need to devote more energy and resources to a task (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009). However, prior research also suggests that when employees are burdened with pressure to perform, their attentional focus narrows (Baumeister & Showers, 1986; Elfering et al., 2013). According to goal-shielding theory, people do not consider alternative goals when they need to meet their most important and urgent goals (Shah et al., 2002). Cognitively, they can do so by splitting their work into different sections and then prioritizing them (i.e., compartmentalization). They will then be able to focus on the section with the highest priority so that they feel more efficacious in achieving the most important goal (Barsky, 2008; Greenbaum et al., 2020). Under high performance pressure, we argue that employees are more prone to use this cognitive control strategy to disassociate the achievement of performance goals from any moral consideration (i.e., moral decoupling). Doing so may allow employees to simplify their work in the pursuit of performance goals and disregard other goals such as the need to behave morally. In other words, what they do at work boils down to a monetary game in which rules of morality are just obstacles (Sims & Brinkmann, 2002). Consistent with our conjecture, prior research has found that employees primed with a business mindset cognitively block out their apprehension about ethical violations (Tenbrunsel & Messick, 1999). Thus:

Hypothesis 1

Performance pressure is positively related to moral decoupling.

We further argue that employees will strive for expediency under performance pressure because it offers a direct and efficient way to address difficult and urgent demands (McLean Parks et al., 2010). Expediency is characterized by employees’ acts of taking shortcuts by skipping important steps and stretching organizational rules (Eissa, 2020; Jonason & O'Connor, 2017). In other words, to achieve specific outcomes, “rules by which things ought to function become elastic, stretching to accommodate increasing pressures to perform” (McLean Parks et al., 2010, p. 702). Prior research indicates that employee expediency often occurs when work situations are highly demanding and efficiency is given the highest priority (Jonason & O’Connor, 2017). Employees who engage in expediency consider that “the means become secondary to the ‘ends’” (McLean Parks et al., 2010, p. 702) and believe it acceptable to enhance performance at the cost of ethical standards (Eissa, 2020). As such, employees may cope with increased performance pressure through expediency. Consistent with our contention, previous studies have shown that expediency represents a strategy for employees to cope with any potential losses in resources (e.g., time pressure, burnout, limited attention) triggered by certain work stress and demands (Eissa, 2020).

Expediency is considered undesirable because it involves skipping important work procedures, leading to failure and ignominy of organizations (Greenbaum et al., 2018). As an unethical behavior, it emphasizes self-interest enhancement at the expense of an organization’s rules and society’s moral expectations (McLean Parks et al., 2010; Treviño et al., 2006). We expect moral decoupling to foster employee expediency by adjusting employees’ thinking about performance and behavioral ethics.

Expediency represents the trade-offs that individuals make between means and ends (McLean Parks et al., 2010). As mentioned previously, employees who morally decouple tend to believe that ethicality is not relevant to performance evaluation (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013; Fehr et al., 2019), and the influence of moral decoupling is driven by judgments of performance but not by judgments of morality (Fehr et al., 2019; Haberstroh et al., 2017). Employees with a moral decoupling mindset are likely to focus on getting the work done and disregard the morality of the ways the tasks are being performed. Because it enables employees to pay attention to the positive effects of expediency (i.e., performance enhancement), moral decoupling allows them to believe it is appropriate to sacrifice any organizational procedure and ethical standard and, consequently, engage in expediency. Conversely, people low in moral decoupling tend to view morality as a critical dimension of performance and therefore are less likely to engage in expediency.

Taken together, we contend that employees under performance pressure will resort to expediency as a coping strategy through the cognitive strategy of moral decoupling. Moral decoupling enables employees who work under high performance pressure to prioritize and pursue performance goals without taking morality into account. Thus,

Hypothesis 2

Performance pressure is positively and indirectly related to employee expediency through moral decoupling.

Dialectical Thinking as a Moderator

Because some people tend to deploy moral decoupling reasoning more steadily and often than others (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013; Fehr et al., 2019), we expect the mediating role of moral decoupling to be contingent on certain individual differences. Extant research shows that a person’s thinking styles affect his or her ability to pursue multiple goals, and divergent and holistic thinking fosters more flexible and malleable processing to handle goal conflicts (Fischer & Hommel, 2012). This reason leads us to propose dialectical thinking, or an individual’s tolerance for seemingly contradictory beliefs (Hamamura et al., 2008; Peng & Nisbett, 1999), as a moderator of the previously proposed indirect relationship between performance pressure and expediency. Prior studies have shown that individuals high in dialectical thinking are particularly able to accept contradictions and tend to view them in a more dialectical manner (Choi et al., 2007; Hamamura et al., 2008). As we argued previously, performance pressure may put employees in a situation in which self-interest tempts them to disregard their moral principles. When presented with a situation of high performance pressure, employees who can think dialectically will more readily accept self-evaluations that are high in performance accomplishment but low in moral achievement and therefore will be more likely to adopt moral decoupling.

When facing controversial issues, individuals high in dialectical thinking tend to believe that opposite propositions can be taken simultaneously and will eventually be reconciled; by contrast, individuals low in dialectical thinking are less able to deal with the coexistence of two potentially contradictory arguments (Choi et al., 2007). In particular, empirical research has shown that such cognitive malleability influences self-concept evaluation so that people high in dialectical thinking can live with an ambivalent self-concept, incorporating both positive and negative evaluations (e.g., “I am extraverted but somewhat shy”) (e.g., Hamamura et al., 2008). Under the high pressure to perform, a high level of dialectical thinking in this case allows employees to be more comfortable with self-concepts such as “I am a good performer, though my behavior is morally questionable” and, therefore, enables them to make trade-offs in such situations by taking cognitive shortcuts. Conversely, employees low in dialectical thinking will have difficultly juggling the trade-off of moral consideration for performance and, thus, will separate getting ahead and acting ethically as two distinct work goals. Taken together, we argue that for employees encountering performance pressure, dialectical thinking may prompt them to engage in expediency through moral decoupling. Thus,

Hypothesis 3

Dialectical thinking moderates the positive indirect effect of performance pressure on employee expediency through moral decoupling, such that the effect is strengthened when dialectical thinking is high (vs. low).

Moral Identity as a Moderator

While employees high in dialectical thinking may be better able to maintain their moral self-concept despite the demand for performing well, there are also limits to doing so (Mazar et al., 2008). In addition to cognitive malleability, we posit that moral identity represents the threshold at which employees can reframe and categorize their behaviors without damage to the moral self. Moral identity captures the extent to which an individual identifies him- or herself as a moral person who is chronically accessible to a set of moral traits (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Gino et al., 2011; Skarlicki et al., 2008). It reflects the self-determined centrality of moral schemas to one’s self-concept and captures the tendency to adhere to moral standards and obligations (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Damon & Hart, 1992). A growing body of research suggests that moral identity plays a critical role in self-regulation by influencing the process through which people identify, interpret, and handle situations involving moral judgment (Aquino et al., 2011; Greenbaum et al., 2013; Shao et al., 2008). These reasons lead us to posit that employees’ moral identities may affect their responses to high performance pressure.

Employees high in moral identity often strive to use ethical ways to pursue goals even in difficult situations. When facing pressure to perform, moral identity will still compel them to improve their performance in a moral manner (Reynolds & Ceranic, 2007). As ethics is a crucial characteristic defining the self-concept among employees of high moral identity (Qin et al., 2018), they will be less prone to achieve the outcome (i.e., ends) without considering ways to do so (i.e., means). In addition, with a high level of moral self-regulation, employees are able to recognize and weigh the occasions of moral violation before making decisions about their actions (Gino et al., 2011; Skarlicki et al., 2008). As such, they will have difficultly engaging in moral decoupling even under high performance pressure. By contrast, employees low in moral identity do not define themselves in moral terms and tend to be less mindful of the adherence to moral principles. Thus, to cope with performance pressure, they can easily decouple ethical concerns from the achievement of performance and are more ready to engage in expedient behavior. Consistent with our conjecture, previous research has shown that individuals low in moral identity are less able to avoid the temptation to behave unethically (Gino et al., 2011). Thus:

Hypothesis 4

Moral identity moderates the positive indirect effect of performance pressure on employee expediency through moral decoupling, such that the effect is strengthened when moral identity is low (vs. high).

Method

Respondents and Procedure

We tested our model with a sample of claims adjusters from an insurance assessment company specialized in automotive traffic accidents in Southeast China. As the company’s frontline employees, after company’s orders are dispatched, these adjusters are expected to reach the traffic scenes soon after the accidents happen. The primary duty of claim adjusters is to work with clients to understand what happened and then to evaluate the damages quickly and accurately according to the company’s policies and procedures.

During our interviews, company managers informed us that the industry is very competitive, so to improve company performance, they set high targets and incentive plans to motivate employees to take as many orders as possible. Performance of claims adjusters’ number of completed orders is prominently displayed in the office. Some of the claim adjusters expressed experiencing heavy performance pressure also during the interview. For these reasons, this company provides an ideal research context for the investigation of performance pressure.

With the assistance of the company’s general manager and human resources manager, we invited all claims adjusters to participate in our three-wave survey. We informed them that their participation was voluntary and that they could drop out at any time. Respondents were compensated with a bonus of RMB 10.00 for completing each survey. In addition, those who attended three full rounds and submitted valid questionnaires had a chance to draw a lottery or raffle (the proportion of winners was 10% of the total number of respondents, and each winner received RMB 100.00).

We assured respondents that their personal information and questionnaire responses would be kept confidential. To do so, we employed an independent third-party research assistant who helped match the respondents’ responses in three waves to distribute incentives, recode each respondent by a unique number, and then delete all personal information. Data were analyzed with anonymity; therefore, neither the company nor the research team had access to respondents’ identifiable information.

At each phase, we distributed questionnaires to all claims adjusters of the company (340). At Time 1 (T1), the respondents rated their demographic information, performance pressure, dialectical thinking, and moral identity. Two hundred ninety-five respondents returned valid questionnaires, a response rate of 86.76%. Two weeks later (T2), respondents provided ratings on moral decoupling and challenge and threat appraisals (control variables), and 270 responded, for a response rate of 79.41%. Approximately another two weeks later (T3), respondents measured expediency, and 262 responded, for a response rate of 77.06%. Thus, 229 respondents finished all three phases of the surveys and submitted valid responses. Of the three-phase respondents, 96.9% were male, and 77.3% were aged 25 years or younger.

Measures

We used 5-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to measure all the items unless noted otherwise. All measurement scales were in Chinese and followed the back-translation process (Brislin, 1970).

Performance Pressure

To measure performance pressure, we used Mitchell et al.’s (2018) four-item scale. Sample questions are “I feel tremendous pressure to produce results” and “The pressures for performance in my workplace are high.” Cronbach's alpha was 0.76.

Dialectical Thinking

We adopted four of the six items of Choi et al.’s (2007) Holism scale to measure respondents’ dialectical thinking. A sample item is “It is more important to find a point of compromise than to debate who is right/wrong when one’s opinions conflict with others’ opinions.” Cronbach's alpha was 0.64.

Moral Identity

To measure moral identity, we used the ten-item scale created by Reed and Aquino (2003). We listed words such as “compassionate,” “fair,” “kind,” “generous,” “helpful,” “hard-working,” and “honest” and asked respondents to visualize the kind of person who has these characteristics. Then, respondents answered questions such as “It would make me feel good to be a person who has these characteristics” and “Being someone who has these characteristics is an important part of who I am.” Cronbach's alpha was 0.79.

Moral Decoupling

We measured moral decoupling with five items adapted from the measurement scale of Fehr et al. (2019). Sample questions are “Employees’ unethical actions do not change others’ assessments of their performance on work tasks” and “I believe that judgments of performance on work tasks should remain separate from judgments of morality.” Cronbach's alpha was 0.85.

Employee Expediency

We adopted a four-item measurement scale (1 = never, 5 = always) from Greenbaum et al. (2018). Employees responded to the question, “To what extent do you engage in the following behaviors?” Sample items are “cuts corners to complete work assignments more quickly” and “ignores company protocols in order to get what I want.” Cronbach's alpha was 0.93.

Control Variables

To check whether moral decoupling is a unique mediating mechanism, we controlled for challenge and threat appraisals in examining the indirect effect of performance pressure on expediency through moral decoupling. We measured these two types of appraisals at T2 using Drach-Zahavy and Erez’s (2002) 12-item scale. A sample item for challenge appraisal is “Performance pressure provides me opportunities to overcome obstacles,” and a sample item for threat appraisal is “I’m worried that performance pressure might reveal my weaknesses.” Cronbach's alpha for challenge appraisal was 0.89 and 0.94 for threat appraisal. Following previous research (Mitchell et al., 2018, 2019), we also controlled for several variables that might affect unethical behaviors and our hypothesized relationships, including gender, age and positive affectivity. To measure positive affectivity, we used Iverson et al.’s (1998) three-item scale. A sample item is “I usually find ways to liven up my day.” Cronbach's alpha was 0.86. The inclusion of gender, age and positive affectivity did not change the results of our model testing.

Analytical Strategy

We used SPSS 19.0 to test our hypotheses. Employing the PROCESS macro (Model 4), we estimated the indirect effects and obtained the bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) to establish the significance of the mediation (with 1000 bootstrap samples). When the CI does not contain zero, the indirect effect’s significance is established (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). We tested the moderating effects following Aiken and West’s (1991) procedures. To reduce multicollinearity, we first mean-centered the independent variables and the moderators (i.e., performance pressure, dialectical thinking, and moral identity). A moderating effect is evidenced when the interaction term is significant. We then plotted the interaction effect using a simple slope analysis. Furthermore, we employed the PROCESS macro (Model 7) to evaluate the moderated indirect effects (Edwards & Lambert, 2007).

Results

Before analyzing the hypotheses, we tested the distinctiveness of the constructs through a series of confirmatory factor analyses using Mplus 7. To reduce the complexity of the measurement model, we followed Brooke et al.’s (1988) procedures to generate three parcels of indicators for each variable. Specifically, we averaged the items with the highest and lowest loadings to establish the first indicator, then averaged the items with the second highest and lowest loadings to establish the second indicator, and so forth until all items were parceled into one of the three indicators (Mathieu & Farr, 1991). We assessed goodness-of-fit with the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). A reasonable model fit is demonstrated when the CFI and TLI are above 0.90 and the RMSEA and SRMR are below 0.08 (Byrne, 1998).

The CFA results showed that the eight-factor model (consisting of performance pressure, dialectical thinking, moral identity, moral decoupling, employee expediency, positive affectivity, challenge appraisal, and threat appraisal) displayed good model fit: χ2(224) = 323.57, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05, and SRMR = 0.06. Compared with the one-factor model in which we loaded the items of all variables on a single latent factor, the eight-factor model produced a significantly better fit: Δχ2 (28) = 1004.23, p < 0.001. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of all the variables.

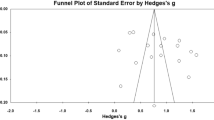

H1 predicted that high performance pressure would lead to moral decoupling. The results reveal that performance pressure was significantly and positively related to moral decoupling (b = 0.27, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), in support of H1. H2 proposed that moral decoupling would mediate the relationship between performance pressure and employee expediency. As Fig. 1 illustrates, performance pressure had a significant indirect effect on expediency through threat (indirect effect = 0.16, boot SE = 0.06, 95% CI: [0.06, 0.31]) rather than challenge appraisal (indirect effect = − 0.001, boot SE = 0.01, 95% CI: [− 0.04, 0.02]). More important, performance pressure had a positive effect on moral decoupling (b = 0.30, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001), and after we accounted for the stress-appraisal effect, moral decoupling remained positively and significantly related to employee expediency (b = 0.24, SE = 0.10, p = 0.02). The indirect effect of performance pressure on employee expediency through moral decoupling was also significant after we accounted for the mediating effect of challenge and threat appraisal (indirect effect = 0.07, boot SE = 0.04, 95% CI: [0.01, 0.15]). Therefore, H2 was supported.

H3 proposed that the indirect effect of performance pressure on employee expediency (through moral decoupling) would be stronger for employees with a high level of dialectical thinking. The interaction term between performance pressure and dialectical thinking was significant (b = 0.20, SE = 0.08, p = 0.02). We tested the conditional effect at high (one standard deviation above) and low (one standard deviation below) levels of dialectical thinking. Following Aiken and West’s (1991) procedure, we then plotted the interaction effect (see Fig. 2). The positive relationship between performance pressure and moral decoupling was significant for high dialectical thinking (b = 0.42, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) but not for low dialectical thinking (b = 0.10, SE = 0.10, ns).

More important, after we accounted for challenge appraisal and threat appraisal, the conditional indirect effect of performance pressure on employee expediency through moral decoupling remained significant at a high level of dialectical thinking (conditional indirect effect = 0.10, boot SE = 0.05, 95% CI: [0.01, 0.20]) rather than a low level of dialectical thinking (conditional indirect effect = 0.03, boot SE = 0.04, 95% CI: [− 0.03, 0.12]). The index of moderated mediation was also significant (index = 0.05, boot SE = 0.03, 95% CI: [0.002, 0.13]). Thus, H3 was supported.

H4 proposed that the indirect effect of performance pressure on employee expediency (through moral decoupling) would be stronger for employees low in moral identity. However, the interaction term between performance pressure and moral identity was not significant (b = 0.08, SE = 0.11, ns). Although the conditional indirect effect of performance pressure on employee expediency was significant both at high [conditional indirect effect = 0.08, boot SE = 0.05, 95% CI: (0.01, 0.19)] and low [conditional indirect effect = 0.05, boot SE = 0.04, 95% CI: (0.004, 0.16)] levels of moral identity, the index of moderated mediation was not significant [index = 0.03, boot SE = 0.04, 95% CI: (− 0.03, 0.12)]. Thus, H4 was not supported.

Discussion

With the business environment becoming increasingly competitive, removing performance pressure in organizations is impractical (Spoelma, 2021). Therefore, understanding why employees engage in unethical behavior to cope with performance pressure is imperative. From a moral reasoning perspective, we developed a moderated mediation model to address the questions of how and when employees react to performance concerns through immoral means. Our results reveal that, in addition to stress appraisal, performance pressure prompts moral decoupling among employees and has an indirect effect on employee expediency through the latter’s mediating mechanism. Furthermore, this indirect effect is strong and significant when employees have high levels of dialectical thinking. Our findings provide a deeper understanding of performance pressure, moral decoupling, and unethical behavior.

Theoretical Contributions

First, by introducing moral decoupling as a key mechanism, our research advances the literature on performance pressure by testing an implicit assumption in prior studies. Prior research suggests that threats resulting from performance pressure deplete one’s resources and “heighten states associated with a need for self-protection” (Mitchell et al., 2018, p. 56). Through decreased self-regulation and increased self-protection, employees experiencing performance pressure tend to disregard their moral principles in their pursuit of performance goals. Our study explicitly examines this implicit assumption by exploring whether performance pressure impels employees to engage in selective dissociation from morality (i.e., moral decoupling) to achieve performance. To test whether moral decoupling is a unique mechanism, in our study design and analyses we accounted for the stress-appraisal effect, which research has demonstrated is a key mediating mechanism of why employees may behave badly under performance pressure (Mitchell et al., 2019). In doing so, we show that performance pressure is more than a stressful experience, thus shedding more light on why employees may engage in dysfunctional behaviors when they are required to meet high performance targets (e.g., Babalola et al., 2020; Welsh et al., 2020).

Second, our study also extends research on moral decoupling by showing when employees will put morality aside in organizations. Fehr et al. (2019) found that supervisors adopting moral decoupling give higher performance evaluations to employees engaging in unethical pro-organizational behavior. In our study, we demonstrate that employees may deploy moral decoupling to evaluate their own performance and behavior. Perceived performance pressure prompts employees to engage in moral decoupling especially if they are high in dialectical thinking. These results not only reinforce the view that moral decoupling can be situationally or chronically activated (Fehr et al., 2019) but also address the important question of “who engages in decoupling and when it occurs” (Cowan & Yazdanparast, 2021, p. 116).

Third, prior studies have called for additional research to examine less morally intense unethical behaviors because these behaviors, which have been largely ignored in the literature, can also lead to costly outcomes (Eissa, 2020). Expediency is a covert and non-interpersonal behavior that is often conducted in the name of efficient task completion (Eissa, 2020; Greenbaum et al., 2018). Although it seems less morally intense than other unethical behaviors such as cheating and theft, multiple scandals (e.g., the defective automobile ignitions of General Motors, safety complaints of Boeing’s manufacturing issues) have shown the harm expediency causes to organizations and the public (Basu, 2014; Huddleston, 2019). Among the few studies investigating the antecedents of expediency, Greenbaum et al. (2018) found that employee expediency results from supervisor expediency, whereas Eissa (2020) found that employees engage in expediency as a result of feeling burned-out from their initiative behaviors. Our research shows that organizations can unintentionally induce their employees’ expediency. Ironically, while organizations often use performance pressure as a productive strategy to enhance work efficiency, employees may handle pressure by convenient means that will be counterproductive to organizations. Our focus on employee expediency reveals a specific way performance pressure produces faux “performance” that is detrimental to the long-term interest of organizations.

Fourth, although prior studies have examined how performance pressure negatively affects employees’ behavior (e.g., Ellis, 2006; Gardner, 2012; Mitchell et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2017), only some have investigated boundary conditions for the negative effect (Mitchell et al., 2019; Spoelma, 2021). Our work extends this line of inquiry and examines whether dialectical thinking is an important individual difference accounting for employees’ reactions to performance pressure. While Mitchell et al.’s (2019) study reveals that the aversive effect of performance pressure is more salient among employees low in trait resilience, we find that a high level of dialectical thinking activates moral decoupling when employees encounter performance pressure. The results of Mitchell et al.’s (2019) and our studies suggest that examining individual differences during the investigation of performance pressure is important.

Another notable finding is that, though we hypothesized that moral identity would affect the mediating role of moral decoupling, we did not find support for this hypothesis. This finding is surprising because it deviates from prior research that suggests that moral identity is effective in impeding unethical decision-making and antisocial behavior (e.g., Detert et al., 2008; Shao et al., 2008). However, a recent study indicates that moral identity is complex and multi-faceted, encompassing benevolence, justice, obligation, and integrity (Hannah et al., 2020). Moral identity also manifests in different roles, and therefore moral identity within a role does not predict deviance associated with other roles (Hannah et al., 2020). For example, individuals may have a moral identity as a son or daughter and another moral identity as a coworker. In our study, moral identity did not buffer the negative effect of performance pressure on employee expediency through moral decoupling. This result may be due to the existence of moral identity complexity, such that a general moral identity is not effective in explaining the relationship between performance pressure and expediency. We encourage future research to explore employees’ moral identities in different roles and examine how the identities in each role affect the mediating impact of moral decoupling.

Practical Implications

Our study has implications for organizations and managers, particularly those attempting to motivate employees through performance pressure. First, to discourage moral decoupling, organizations can consider articulating a corporate culture in which high performance and ethical behavior are not deemed contradictory. Instead, employees should be reminded that the two can go hand in hand and that it is important to achieve high performance without sacrificing morality. Managers should communicate this important message to every employee and keep an eye on those who attempt to put performance before ethics. In terms of performance evaluations, our research findings suggest that managers should take ethics into account when assessing their employees. While the goal of performance pressure is to motivate employees to contribute more, organizations and managers should make it clear that unethical behavior will not be tolerated even among the high performers.

Our second implication has to do with employee selection. Our results show that when employees experienced performance pressure, those high in dialectical thinking were more likely to separate performance achievements from ethicality and engaged in expediency. When recruiting and selecting employees, managers may hope to hire individuals high in dialectical thinking because a flexible mode of thinking can be useful in employees’ decision-making and multi-tasking (Fischer & Hommel, 2012; Laureiro-Martínez & Brusoni, 2018). Yet our study’s results suggest that managers should closely monitor employees high in dialectical thinking if their jobs require them to meet high performance goals. Doing so can ensure that these employees will not cut corners (i.e., expediency) to temporarily satisfy performance expectations.

In discussing these implications, it is important for us to note that ethics matter not only for performance evaluation; they are also important in domains outside performance. For example, organizational ethics can affect employees’ job satisfaction, turnover intention, and organizational commitment (Demirtas & Akdogan, 2015; Fu et al., 2011; Pettijohn, 2008). We believe that valuing ethics and adhering to moral standards is the right thing to do for both organizations and employees regardless of whether their behavior is related to performance. In addition, employees’ ethical behaviors have societal implications because such behaviors help create and maintain ethical environments at the societal level. Thus, while acting ethically is the right thing to do and “good ethics is good for business” (Davis, 1994, p. 873), we regard ethics as crucial in every aspect of business management.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that offer directions for future research. First, we cannot establish causality from our survey data. We took efforts to address this issue by measuring the predictor, mediator, and dependent variable in three waves. Because our study provides preliminary evidence for the morality-mechanism view of performance pressure, we recommend that future research replicate our study and simultaneously conduct experiments to validate our findings. Second, we asked employees to provide self-reports of expediency. Research shows that the use of self-rated counterproductive work behavior is a viable choice (Berry et al., 2012); however, an objective measure of employee expediency would be ideal. Thus, future research might try to validate our findings by obtaining company-recorded employee expediency. Third, our respondents were predominantly men. While previous research suggests that gender plays little role in the effect of performance pressure on employees (Mitchell et al., 2018), we still encourage future research to consider replicating our study in a sample with a more balanced gender composition.

In addition, research might test whether performance pressure has a curvilinear relationship to outcomes. For example, Baer and Oldam (2006) found that when creative time pressure was at an intermediate level, employees were the most optimally stimulated, resulting in the highest creativity. Future research could follow this line of thought to explore a potentially curvilinear relationship between performance pressure and employee performance.

Finally, future research might examine additional boundary conditions that may influence the moral decoupling process. For example, ethical expertise, or “the degree to which one is knowledgeable about and skilled at applying moral values within a given work context” (Dane & Sonenshein, 2015, p. 74), could be an interesting moderator. Employees high in ethical expertise are able to solve morality-related problems, such that they may not need to separate performance from ethics when encountering performance pressure.

Conclusion

The literature indicates that employees may cope with performance pressure through unethical means. We extend this literature stream by demonstrating the mediating role of moral decoupling in the relationship between performance pressure and expediency. Furthermore, we investigate the conditions under which employees are more likely to morally decouple to engage in expediency. In particular, our results reveal that employees with high levels of dialectical thinking are more likely to emphasize performance goals and overlook moral concerns. We hope this work will encourage scholars to explore effective interventions to manage the detrimental impacts of performance pressure.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions-institute for social and economic research (ISER). SAGE: Thousand Oaks.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A., II. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Aquino, K., McFerran, B., & Laven, M. (2011). Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 703–718.

Babalola, M. T., Greenbaum, R. L., Amarnani, R. K., Shoss, M. K., Deng, Y., Garba, O. A., & Guo, L. (2020). A business frame perspective on why perceptions of top management’s bottom-line mentality result in employees’ good and bad behaviors. Personnel Psychology, 73(1), 19–41.

Baer, M., & Oldham, G. R. (2006). The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: Moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 963–970.

Barsky, A. (2008). Understanding the ethical cost of organizational goal-setting: A review and theory development. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(1), 63–81.

Basu, T. (2014). Timeline: A history of GM's ignition switch defect. National Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2014/03/31/297158876/timeline-a-history-of-gms-ignition-switch-defect. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004242999_017.

Baumeister, R. F., & Showers, C. J. (1986). A review of paradoxical performance effects: Choking under pressure in sports and mental tests. European Journal of Social Psychology, 16(4), 361–383.

Berry, C. M., Carpenter, N. C., & Barratt, C. L. (2012). Do other-reports of counterproductive work behavior provide an incremental contribution over self-reports? A meta-analytic comparison. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 613–636.

Bhattacharjee, A., Berman, J. Z., & Reed, A. (2013). Tip of the hat, wag of the finger: How moral decoupling enables consumers to admire and admonish. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(6), 1167–1184.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216.

Brooke, P. P., Russell, D. W., & Price, J. L. (1988). Discriminant validation of measures of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(2), 139–145.

Byrne, D. (1998). Complexity theory and the social sciences: An introduction. Routledge.

Choi, I., Koo, M., & Choi, J. A. (2007). Individual differences in analytic versus holistic thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(5), 691–705.

Choi, B. K., Moon, H. K., & Ko, W. (2013). An organization’s ethical climate, innovation, and performance: Effects of support for innovation and performance evaluation. Management Decision, 51(6), 1250–1275.

Cialdini, R. B., Petrova, P. K., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). The hidden costs of organizational dishonesty. MIT Sloan Management Review, 45(3), 67–73.

Cowan, K., & Yazdanparast, A. (2021). Consequences of moral transgressions: How regulatory focus orientation motivates or hinders moral decoupling. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(1), 115–132.

Damon, W., & Hart., D. (1992). Self-understanding and its role in social and moral development. In M. H. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental psychology: An advanced textbook (pp. 421–464). Erlbaum.

Dane, E., & Sonenshein, S. (2015). On the role of experience in ethical decision making at work: An ethical expertise perspective. Organizational Psychology Review, 5(1), 74–96.

Davis, J. J. (1994). Good ethics is good for business: Ethical attributions and response to environmental advertising. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(11), 873–885.

Demirtas, O., & Akdogan, A. A. (2015). The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 59–67.

Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 374–391.

Ditto, P. H., Pizarro, D. A., & Tannenbaum, D. (2009). Motivated moral reasoning. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 50, 307–338.

Drach-Zahavy, A., & Erez, M. (2002). Challenge versus threat effects on the goal–performance relationship. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 88(2), 667–682.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22.

Egan, M. (2016). Wells Fargo’s new accountant openings plunge. CNN. Retrieved from https://money.cnn.com/2016/10/14/investing/wells-fargo-earnings-scandal-customers.

Eisen, B. (2020, February 22). Wells Fargo reaches settlement with government over fake-accounts scandal. The Wall Street Journal Eastern Edition, www.wsj.com/articles/wells-fargo-nears-settlement-with-government-over-fake-accounts-scandal.

Eisenberger, R., & Aselage, J. (2009). Incremental effects of reward on experienced performance pressure: Positive outcomes for intrinsic interest and creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(1), 95–117.

Eissa, G. (2020). Individual initiative and burnout as antecedents of employee expediency and the moderating role of conscientiousness. Journal of Business Research, 110, 202–212.

Elfering, A., Grebner, S., & de Tribolet-Hardy, F. (2013). The long arm of time pressure at work: Cognitive failure and commuting near-accidents. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(6), 737–749.

Ellis, A. P. (2006). System breakdown: The role of mental models and transactive memory in the relationship between acute stress and team performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 576–589.

Fehr, R., Welsh, D., Yam, K. C., Baer, M., Wei, W., & Vaulont, M. (2019). The role of moral decoupling in the causes and consequences of unethical pro-organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 153(4), 27–40.

Fischer, R., & Hommel, B. (2012). Deep thinking increases task-set shielding and reduces shifting flexibility in dual-task performance. Cognition, 123(2), 303–307.

Flitter, E. (2020, February 21). The price of Wells Fargo’s fake account scandal grows by $3 billion. New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/21/business/wells-fargo-settlement.html.

Fu, W., Deshpande, S. P., & Zhao, X. (2011). The impact of ethical behavior and facets of job satisfaction on organizational commitment of Chinese employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(4), 537–543.

Gardner, H. K. (2012). Performance pressure as a double-edged sword: Enhancing team motivation but undermining the use of team knowledge. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(1), 1–46.

Gatewood, R. D., & Carroll, A. B. (1991). Assessment of ethical performance of organization members: A conceptual framework. Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 667–690.

Gilley, K. M., Robertson, C. J., & Mazur, T. C. (2010). The bottom-line benefits of ethics code commitment. Business Horizons, 53(1), 31–37.

Gino, F., Schweitzer, M. E., Mead, N. L., & Ariely, D. (2011). Unable to resist temptation: How self-control depletion promotes unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 191–203.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Eissa, G. (2012). BLM as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 343–359.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., & Priesemuth, M. (2013). To act out, to withdraw, or to constructively resist? Employee reactions to supervisor abuse of customers and the moderating role of employee moral identity. Human Relations, 66(7), 925–950.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., Bonner, J. M., Webster, B. D., & Kim, J. (2018). Supervisor expediency to employee expediency: The moderating role of leader–member exchange and the mediating role of employee unethical tolerance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(4), 525–541.

Greenbaum, R. L., Bonner, J. M., Mawritz, M. B., Butts, M. M., & Smith, M. B. (2020). It is all about the bottom line: Group bottom–line mentality, psychological safety, and group creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(6), 503–517.

Gutnick, D., Walter, F., Nijstad, B. A., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2012). Creative performance under pressure: An integrative conceptual framework. Organizational Psychology Review, 2(3), 189–207.

Haberstroh, K., Orth, U. R., Hoffmann, S., & Brunk., B. (2017). Consumer response to unethical corporate behavior: A re-examination and extension of the moral decoupling model. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(1), 161–173.

Hamamura, T., Heine, S. J., & Paulhus, D. L. (2008). Cultural differences in response styles: The role of dialectical thinking. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(4), 932–942.

Hannah, S. T., Thompson, R. L., & Herbst, K. C. (2020). Moral identity complexity: Situated morality within and across work and social roles. Journal of Management, 46(5), 726–757.

Harris, M., & Tayler, B. (2019). Don’t let metrics undermine your business: An obsession with the numbers can sink your strategy. Harvard Business Review, 97(5), 63–69.

Huddleston Jr., T. (2019). Boeing’s Dreamliner jet is now facing claims of manufacturing issues. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/04/20/boeings-dreamliner-jet-now-facing-claims-of-manufacturing-issues-nyt-report.html.

Iverson, R. D., Olekalns, M., & Erwin, P. J. (1998). Affectivity, organizational stressors, and absenteeism: A causal model of burnout and its consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 52(1), 1–23.

James, H. S. (2000). Reinforcing ethical decision making through organizational structure. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(1), 43–58.

Jensen, J. M., Cole, M. S., & Rubin, R. S. (2019). Predicting retail shrink from performance pressure, ethical leader behavior, and store-level incivility. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(6), 723–739.

Jonason, P. K., & O’Connor, P. J. (2017). Cutting corners at work: An individual differences perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 146–153.

Jones, T. M., & Ryan, L. V. (1998). The effect of organizational forces on individual morality: Judgment, moral approbation, and behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(3), 431–445.

Laureiro-Martínez, D., & Brusoni, S. (2018). Cognitive flexibility and adaptive decision-making: Evidence from a laboratory study of expert decision makers. Strategic Management Journal, 39(4), 1031–1058.

Lee, J. S., & Kwak, D. H. (2016). Consumers’ responses to public figures’ transgression: Moral reasoning strategies and implications for endorsed brands. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(1), 101–113.

Mathieu, J. E., & Farr, J. L. (1991). Further evidence for the discriminant validity of measures of organizational commitment, job involvement, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(1), 127–133.

Matute, J., Sánchez-Torelló, J. L., & Palau-Saumell, R. (2021). The influence of organizations’ tax avoidance practices on consumers’ behavior: The role of moral reasoning strategies, political ideology, and brand identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 174(2), 369–386.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

McLean Parks, J., Ma, L., & Gallagher, D. G. (2010). Elasticity in the “rules” of the game: Exploring organizational expedience. Human Relations, 63(5), 701–730.

Mitchell, M. S., Baer, M. D., Ambrose, M. L., Folger, R., & Palmer, N. F. (2018). Cheating under pressure: A self-protection model of workplace cheating behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(1), 54–73.

Mitchell, M. S., Greenbaum, R. L., Vogel, R. M., Mawritz, M. B., & Keating, D. J. (2019). Can you handle the pressure? The effect of performance pressure on stress appraisals, self-regulation, and behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 62(2), 531–552.

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 1–48.

Mortensen, R. A., Smith, J. E., & Cavanagh, G. F. (1989). The importance of ethics to job performance: An empirical investigation of managers’ perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 8(4), 253–260.

Peng, K., & Nisbett, R. E. (1999). Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. American Psychologist, 54(9), 741–754.

Pettijohn, C., Pettijohn, L., & Taylor, A. J. (2008). Salesperson perceptions of ethical behaviors: Their influence on job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(4), 547–557.

Qin, X., Huang, M., Hu, Q., Schminke, M., & Ju, D. (2018). Ethical leadership, but toward whom? How moral identity congruence shapes the ethical treatment of employees. Human Relations, 71(8), 1120–1149.

Quade, M. J., Greenbaum, R. L., & Petrenko, O. V. (2017). “I don’t want to be near you, unless”: The interactive effect of unethical behavior and performance onto relationship conflict and workplace ostracism. Personnel Psychology, 70(3), 675–709.

Reed, A. I., & Aquino, K. F. (2003). Moral identity and the expanding circle of moral regard toward out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1270–1286.

Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2007). The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: An empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1610–1624.

Schwepker, C. H., & Ingram, T. N. (1996). Improving sales performance through ethics: The relationship between salesperson moral judgment and job performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(11), 1151–1160.

Schwieren, C., & Weichselbaumer, D. (2010). Does competition enhance performance or cheating? A laboratory experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(3), 241–253.

Shah, J. Y., Friedman, R., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2002). Forgetting all else: On the antecedents and consequences of goal shielding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1261–1280.

Shao, R., Aquino, K., & Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(4), 513–540.

Sims, R. R., & Brinkman, J. (2002). Leaders as moral role models: The case of John Gutfreund at Salomon Brothers. Journal of Business Ethics, 35(4), 327–339.

Skarlicki, D. P., van Jaarsveld, D. D., & Walker, D. D. (2008). Getting even for customer mistreatment: The role of moral identity in the relationship between customer interpersonal injustice and employee sabotage. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1335–1347.

Spoelma, T. M. (2021). Counteracting the effects of performance pressure on cheating: A self-affirmation approach. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000986

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (1999). Sanctioning systems, decision frames, and cooperation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 684–707.

Thatcher, S. M., & Fisher, G. (2022). From the editors—The nuts and bolts of writing a theory paper: A practical guide to getting started. Academy of Management Review, 47(1), 1–8.

Treviño, L. K. (1992). Moral reasoning and business ethics: Implications for research, education, and management. Journal of Business Ethics, 11, 445–459.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Welsh, D. T., & Ordóñez, L. D. (2014). The dark side of consecutive high performance goals: Linking goal setting, depletion, and unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123(2), 79–89.

Welsh, D., Bush, J., Thiel, C., & Bonner, J. (2019). Reconceptualizing goal setting’s dark side: The ethical consequences of learning versus outcome goals. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 150(1), 14–27.

Welsh, D. T., Baer, M. D., & Sessions, H. (2020). Hot pursuit: The affective consequences of organization-set versus self-set goals for emotional exhaustion and citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(2), 166–185.

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495.

Ye, Q., Wang, D., & Guo, W. (2019). Inclusive leadership and team innovation: The role of team voice and performance pressure. European Management Journal, 37(4), 468–480.

Zhang, W., Jex, S. M., Peng, Y., & Wang, D. (2017). Exploring the effects of job autonomy on engagement and creativity: The moderating role of performance pressure and learning goal orientation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(3), 235–251.

Funding

This research is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers: 71872135, 72102043, 7210020582).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J.N.Y., Lam, L.W., Liu, Y. et al. Performance Pressure and Employee Expediency: The Role of Moral Decoupling. J Bus Ethics 186, 465–478 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05254-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05254-3