Abstract

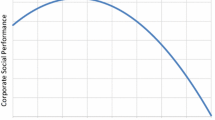

This study examines whether the chief executive officer’s (CEO’s) poverty experience has an impact on firms’ corporate social responsibility (CSR). We find that firms’ CSR performance increases with CEOs’ poverty experience; specifically, firms with CEOs who experienced early-life poverty are associated with more socially responsible activities and fewer socially irresponsible activities, such as on-the-job consumption, and are more associated with key stakeholder-related rather than community-related CSR. We further find that the positive relationship between the CEO’s poverty experience and CSR strengthens for well-educated or powerful CEOs. Our evidence is consistent with our conjecture that CEOs who experienced early-life poverty have stronger compassion and prosocial psychology. Consequently, these CEOs are more willing to make long-term investments in socially beneficial activities, leading to better CSR performance, which further confirms the altruistic motivation of CSR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Much of the literature has increasingly recognized that “an effective nonmarket strategy, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy, is of vital importance to firm survival, organizational performance, and possibly sustainable competitive advantage” (Al-Shammari et al., 2019; Mellahi et al., 2016; Planer-Friedrich & Sahm, 2020). Given CSR’s strategic importance, an important research topic in accounting and management literature involves understanding why different enterprises perform their social responsibilities differently, that is, what drives CSR. One influential explanation is that CSR is a conscious, self-interested action for the sake of seeking economic interests by establishing “reputation capital” or seeking political resources that parallel institutional norms (Dai et al., 2014). The differences in such self-interested demands either directly or indirectly lead to differences in CSR. Early scholarly work observed antecedents to CSR that include not only external drivers, such as external stakeholders’ salience, stakeholder activism, or institutional pressures (Lin et al., 2013; Mohammad & Husted, 2019; Tang et al., 2018b), but also such internal drivers as executive incentives, board characteristics, financial performance, and the chief executive officer’s (CEO’s) political ideologies (Hu et al., 2018). However, regardless of whether CSR activities are conducted under external pressures or driven by internal economic factors, involuntary and formal CSR activities may occur.

Previous literature often evades or ignores the altruistic motivation, as it is difficult to separate it from other motivations; however, CSR activities often unconsciously occur due to sympathy which stems from a moral emotion obtained through personal experience (Hahn & Gawronski, 2015). In fact, compared with the need for financial performance, institutional constraints, or external pressures, CSR activities that are derived only from personal values and moral emotion can be considered voluntary, altruistic behaviors in the true sense (Batson et al., 1991). As a public firm’s most powerful figure and in a position to shape and influence, CEOs significantly influence their organizations (Chen et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2011; Hambrick & Mason, 1984). According to the upper echelons theory, executives often inject their personal values, beliefs and dispositions formed by their personal experience into their firms’ decision (Zhu & Chen, 2015). The heterogeneity in CEOs’ managerial styles reflects the variation in their individual life experiences (Benmelech & Frydman, 2015; Chin et al., 2013; Harbrick & Mason, 1984). While as the primary decision-maker and actual executor of CSR activities, CEOs also form their CSR cognition based on moral feelings gained from personal experience (Fabrizi et al., 2014). Considering adverse life experience, such as poverty, can make people more sensitive to others’ needs and more distressful to others’ painful lives, and thus more in a position to think of others and concern about others’ welfare, which leads to individual differences in empathy-related responses as sympathy and prosocial behavior (Côté et al., 2013; Eisenberg, 2000; Xu & Li, 2016). Thus, this paper asks: Does the values and moral emotions brought by the CEOs’ early-life poverty experience affect their CSR cognition, and then compel enterprises to conduct altruistic CSR activities? Notwithstanding the fruitful findings regarding the relationship between firm’s CSR decision-making and CEOs’ demographic, psychological characteristics and other factors, the role of the CEO’s experience in corporate social actions remains understudied.

Therefore, this paper answers this question using a sample of Chinese-listed companies with data spanning 2006–2017 and follows this line of research by discussing the influence of CEOs’ early-life poverty experiences on their later CSR activities. We try to interpret the mechanism of the impact of CEO’s early-life experience of adversity on enterprise decision-making from an altruistic perspective. This research contributes to and fills several gaps in previous literature given the following primary contributions: First, this work expands on previous research on the motivations of CSR strategies. Scholars have devoted significant effort to understanding why companies facing similar pressures exhibit heterogeneous responses to CSR. This line of work suggests that diverse CSR actions are a function of macro- and organizational-level factors, including stakeholder or institutional pressures, legal mandates, and economic benefits, among others (Becchetti et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2013; Mohammad & Husted, 2019; Planer-Friedrich & Sahm, 2020; Tang et al., 2018b). While Literature on the upper echelons theory also reveals that firms’ CSR is significantly influenced by CEOs’ demographic (Lewis et al., 2014) and psychological characteristics (Al-Shammari et al., 2019; Borghesi et al., 2014; McCarthy et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2018a), turnover (Bernard et al., 2018; Oh et al., 2018), power (Muttakin et al., 2018; Walls & Berrone, 2017), ability (Yuan et al., 2019), and education (Rego et al., 2017). These findings notwithstanding, the impact of the CEO’s early-life poverty experience on CSR remains understudied compared to other organizational or personal factors. We discuss the impact of CEOs’ early-life poverty experience on CSR, which will effectively expand literature on the selection of CEOs’ characteristic dimensions and provide a new perspective of individual characteristics on altruistic CSR motivations.

Second, we also expand research on the high echelons theory by responding to the calls to open the “black box” between executives’ characteristics and organizational results. Although existing studies have explored the impact of various CEO characteristics on CSR, discussions on the mechanism for facilitating such effects are limited due to the difficulty in obtaining data about CEOs’ cognition and behavioral motivations. Consequently, this paper not only examines the mechanism of CEOs’ poverty experiences’ impacts on CSR, but also selects multiple characteristics—such as power and educational background—as regulatory factors to explore the conditional boundaries of this impact. This paper then opens the “black box” regarding the influence of executives’ characteristics on organizational actions.

Third, we further expand related research on the influence of CEOs’ early-life experience on organizational actions. Previous literature focused primarily on some events that have been proven significance and lasting influence on people’s beliefs and preferences. This includes self-selection experiences, such as joining the army (Benmelech & Frydman, 2015) or work experience (Bamber et al., 2010; Graham et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2017); and external, non-human experiences, such as experiences with war (Malmendier et al., 2011), severe economic downturns (Graham et al., 2011), and natural disasters (Bernile et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2019). Discussing the influence of such experiences—and CEOs’ early-life experience in particular—on executives’ psychology, logical thinking, risk attitudes, and morality can explain a large part of the variation in corporate financial decisions, such as capital structure, investments, compensation, and disclosure policies. We extend this research from the CSR performance perspective, which reveals the long-term consequences of CEOs’ early-life experiences.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

CSR Antecedents

Petrenko et al. (2016) classified CSR antecedents into two categories: internal drivers (such as ethical concerns, compliance, culture, and key organizational members’ ideologies) and external drivers (such as the institutional environment and major stakeholders’ concerns). The majority of theoretical and empirical works focused on such contextual factors as the institutional environment (Surroca et al., 2013), government regulations (Campbell, 2007; Tang et al., 2018b), shareholder and stakeholder pressures (Lin et al., 2013), social legitimacy and goodwill signaling (Mohammad & Husted, 2019; Perks et al., 2013), and the access to external resources, such as funding and institutional investors (Wang et al., 2016). Although this perspective might reveal that firms’ environmental responses are similar if the firms face similar pressures, evidence suggests that firms’ CSR responses can differ substantially (Berrone et al., 2013; Walls & Berrone, 2017). It is difficult to establish exactly why different organizational responses occur in the context of shared institutional pressures (Berrone et al., 2013).

Part of the answer is thought to involve within-firm factors that the levels and types of CSR activities might at least partially depend on the characteristics or the priorities of a company’s senior executives (Bear et al., 2010; Hemingway & Maclagan, 2004; Yuan et al., 2019). A well-established argument in strategic management research is that senior executives, and particularly CEOs, are central in formulating firm strategies (Haynes & Hillman, 2010). The upper echelons theory (Briscoe et al., 2014; Harbrick & Mason, 1984) argues that the personal values, experiences, and psychological characteristics of firms’ key decision-makers largely influence firm-level strategic decisions. This school of thought builds heavily on Harbrick and Mason’s (1984) seminal work, which depicted organizations as a reflection of their senior management teams. Much of the previous research involving the upper echelons theory used demographic variables as proxies for executives’ subjective beliefs and values to study the effect of these characteristics on corporate strategies and outcomes (Lewis et al., 2014; Yim, 2013). However, scholars have recently begun to explore senior executives’ personality traits to explain their CSR decisions and actions, including their education (Lewis et al., 2014; Rego et al., 2017), psychological characteristics (Al-Shammari et al., 2019; Borghesi et al., 2014; McCarthy et al., 2017; Reimer et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2018a), tenure (Bernard et al., 2018; Oh et al., 2018), power (Muttakin et al., 2018; Walls & Berrone, 2017), and ability (Yuan et al., 2019). Given that CSR is largely a discretionary activity (Chin et al., 2013), and that little consensus exists regarding CSR’s outcomes (Xu et al., 2015), it is important to explain the substantial heterogeneity in companies’ CSR profiles by considering senior executives’ personality traits.

Managerial Experience and Corporate Actions

Research on executives’ early-life experiences involves managers’ heterogeneity as well as behavioral finance research. However, due to the difficulty describing early-life experiences, current research has primarily examined events that have significant, lasting impacts on people’s beliefs and preferences, such as joining the army (Benmelech & Frydman, 2015) or work experience (Bamber et al., 2010; Graham et al., 2013). These types of experiences can allow CEOs to accumulate social resources or professional experience, thus affecting their financial decisions in a company (Graham et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2019). For example, Zhou et al. (2017) noted that academic experiences from teaching at colleges and universities or working at scientific research institutions increases CEOs’ risk aversion and reduces agency risks between managers and investors, thus reducing companies’ debt.

However, these experiences are problematic, in that it is difficult to distinguish whether these experiences affect the CEOs’ behaviors or their internal characteristics make them choose these experiences. Consequently, some scholars selected external non-human events as a proxy for executives’ early-life experiences. For example, Malmendier et al. (2011) used war experiences to replace military experiences and discovered that CEOs who had experienced war would adopt radical financial policies; they also found that CEOs born during the Great Depression preferred internal to external debt financing. Similarly, Cain and McKeon (2016) posited that previous economic shocks have long-term, sustained impacts on individuals’ risk preferences; for example, they would be repelled from investing in such risky financial products as stocks. Graham et al. (2011), Zhang (2017), and Hu et al. (2019) demonstrated that CEOs who had worked during the Great Depression or during the most recent global recession were deeply affected by the capital market’s collapse. Bernile et al. (2017), Hanaoka et al. (2018), and Chen et al. (2019) examined the link between CEOs’ disaster experience and firms’ risk and capital costs. They proposed that CEOs who experienced fatal disasters without extremely negative consequences lead more aggressive firms, while CEOs who witnessed extreme disasters behave more conservatively. These patterns manifest in various corporate policies, including leverage, cash holdings, and acquisition activities. Generally, recent research on managers’ experience and organizational actions still focuses on financial decisions, while ignoring any discussion of CSR.

The CEO’s Early-Life Poverty Experience and CSR

Previous studies on behavior found that early-life experiences directly affect adults’ behavioral patterns, and childhood is the most important stage in forming individuals’ modes of thinking and values (Elder, 1974; Locke, 1974). Childhood experiences, and in particularly, painful life events (such as poverty or family disharmony), will lead to particular adult behaviors (Currie & Almond, 2011). Poverty is considered structural violence (Vollhardt, 2009). Experiencing the adversity of existential poverty means living in or near persistent material shortage. People in such an environment are not only threatened by survival but also be socially excluded, marginalized, or disadvantaged. However, a common aphorism states: “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” From a positive psychology perspective, poverty experience can best be understood as a unique set of material circumstances that exposes people to violence and social stigma and presents obstacles to fulfilling basic needs but which also fosters perspective-taking, empathy tendency and self-efficacy, and establishes life meaning and resilience, thereby engendering compassion and presenting opportunities for happiness (Biswas-Diener & Patterson, 2011; Mancini, 2019).

Regarding a mechanism for increasing compassion, a sense of efficacy to help and empathy play a role (Stellar et al., 2017). Staub and Vollhardt (2008) and Hayuni et al. (2019) proposed that empathy consists of three parts—perspective-taking, empathic concern, and personal distress—and exists as a type of psychological reaction that places an individual in a position to understand others’ feelings and projects previous important feelings on others. Individuals generally experience distress when witnessing others’ suffering (Cialdini et al., 1987), particularly, this personal distress may be enhanced among those who have suffered in the past. Influenced by long-term living environment, CEOs who have lived in poor environment can more personally experience difficult living due to poverty. Even if their own family conditions are not necessarily poor, visual shock that witness others in material needs can also aggravate their moral and emotional experiences and cognitive stimulation (Vollhardt, 2009), which not only make them more sensitive to others’ painful lives and feel more empathy toward individuals harmed by utilitarian judgment, but also have increased understanding of others (Luthar et al., 2000). Growth after experiencing difficulties is a process, in which individuals may increase their tendencies not only to adopt others’ perspectives, but also feel a sense of responsibility for others’ welfare. Sharma and Morwitz (2016), Cameron et al. (2019) and Lim and DeSteno (2019) further demonstrated that when adversity (such as poverty and natural disaster experiences) enhances people’s beliefs about their efficacy to recognize others’ suffering and think about others, it mediates greater levels of compassion.

Additionally, individuals living in poverty are exposed to more of the sort of threats to health and well-being that are common in resource-poor environments; however, these individuals possess fewer resources (e.g., money) to cope with these threats. Given their more threatening environments and relative lack of material resources, individuals in poverty also respond adaptively to threats in their environments by building supportive, interdependent networks which they can draw on to confront threats when they arise (Stellar et al., 2012). Poor people orient to the social environment in explaining social events and depend on others to achieve desired outcomes (Piff et al., 2010). Thus, compared with the rich, the desire for spontaneous resource sharing and helping each other is stronger for urban poor (Côté et al., 2013). In one investigation, lower-class students endorsed more interdependent motives (e.g., helping their families, giving back to their communities) for attending university than upper-class students (Stephens et al., 2012). To facilitate the development of supportive, interdependent bonds, lower-class individuals exhibit stronger sense of efficacy to help in the social environment, which can subsequently help them deal with the threats posed by resource-poor environments, and in turn, leads to more sympathetic behaviors.

In summary, surviving past adversity leads people to feel empathy to others’ painful lives, apprehend the state of people in need, and believe they will be effective in helping others, which allows them to upregulate their feelings of compassion not only toward others who are experiencing a malady or tragedy similar to their own but also to all others. While compassion toward another in need reduces perceived psychological distance and is central motivator for many prosocial behaviors that underlie the social exchange and support necessary for building social capital (Crocker & Canevello, 2013; DeSteno, 2015). In conditions where the immediate costs of a prosocial act are high, socially oriented emotions such as compassion might play a more prominent role in motivating seemingly selfless behaviors (DeSteno et al., 2016). “Altruism born of suffering” proposed by Staub (2005) can be used to describe that having successfully faced various previous difficult experiences in life might enable people to extend their compassion more readily that, in turn, leads to altruistic and prosocial behavior, such as CSR activities.

Moreover, Midlarsky (1991) emphasized that meaning in life can create or enhance altruism and prosocial behavior. He identified life meaning and purpose as perhaps the crucial element for surviving extreme situations. After all, purpose involves an intention to contribute to meaningful causes outside the self, which may involve “acting in the larger world on behalf of others” (Cotton Bronk et al., 2009). The insecurity associated with living in a poor environment threatens people’s immediate physiological and safety needs, which challenges an individual’s fundamental assumptions. The poverty environment makes people lose their previous meaning systems. A central task for individuals healing from a difficult life is to restore their “shattered assumptions” about the world and find new meaning and value in their lives (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). To survive, an individual must be able to make larger sense of the otherwise senseless suffering and change his or her worldview, thus returning to a state of cognitive equilibrium (Frankl, 1984; Schwartz, 2009). People living in poverty who do not have a broad purpose to motivate their goals might struggle to engage in effortful, future-oriented activities (Machell et al., 2016). While the drive to make a difference and contribute to the world is central to purpose in life. Engaging in altruistic acts and protect others from poverty can help the poor find a new meaning in life and get out of the suffering. Thus, it is possible that individuals who have lived in poverty and other harsh living conditions become additionally motivated to restore their cognitive equilibrium by ensuring positive events through prosocial behavior (Zoellner & Maercker, 2006). By establishing meaning and purpose in life, people can survive in the adversity of material shortage, which also provides a path toward the promotion of prosocial attitudes and behaviors.

Therefore, CEOs’ poverty experiences in their early years are not only a type of historical memory but also have a profoundly impact on their future behavioral patterns. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

A firm with a CEO who experienced the adversity of poverty in his or her early life exhibits higher levels of CSR performance.

The Moderating Effect of the CEO’s Educational Background

Life adversity, such as poverty, not only can promote prosocial behavior but also might have a negative impact on human psychology and behavior. Without proper guidance, poverty and other adversity can lead to a variety of negative consequences, including symptoms that decrease individual well-being (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance abuse, stress, and sleep disorders) and those that have destructive consequences interpersonally, such as violent behavior and aggression (Santiago et al., 2011). Whether post-adversity growth is positive or negative depends largely on various of interventions (Betancourt & Khan, 2008). Vollhardt (2009) presented a comprehensive motivational process model to show that bad living conditions may motivate different forms of prosocial outcomes depending on how those processes are affected by various volitional and environmental factors. These factors include social support, education, intelligence, effective coping, determination, and flexible attitudes (Joseph & Linley, 2006).

Ghailian (2013) proposed that education can create new interventions that help poor individuals develop resilience, employ their strengths, and otherwise flourish relative to their circumstances. Through systematically professional education and ideological and moral education, people in poverty can get the right guidance in behavior and ideology and thus, derive various kinds of benefits, including increased skills, increased confidence and self-esteem, better moral cultivation and increased social participation. In addition, education can enrich people’s cognition of the world and understanding of life and help people in poverty establish more meaningful life goals (Coles, 2000), which makes them no longer sink in the immediate suffering. Therefore, compared with the uneducated poor, the educated poor are more likely to get out of the predicament and get rebirth, their negative emotions can be more effectively guided and alleviated, and moral sensibility will be more strengthened. This will lead them to possess a stronger awareness of and motivation for prosocial behavior, such as CSR behavior.

Furthermore, poverty is characterized by a lack of various resources, especially educational resources, which is a luxury for the poor. Santiago et al. (2011) proposed that children who grow up in poverty face educational disadvantages. Education is often a critical way for people growing up in poor families to change their fate (Hoynes et al., 2016). However, without the support of their relatives, friends, and people from all walks of life, the poor cannot access education, especially higher education, due to the lack of sufficient funds. While social support is one of the most important protective factors which contribute to resilience (Staub & Vollhardt, 2008). Receiving help from others and experiencing caring and supportive relationships can promote the poor’s altruism by exposing people to helping role models, enabling them to learn from observation and identify with the helpers (Puvimanasinghe et al., 2014). Therefore, the poor who have the opportunity to receive a good education through the help of all walks of life are more likely to get out of the adversity of poverty and in turn, have a stronger sense of efficacy to help and repay society due to the power of models. This suggests that good education can strengthen the formation and development of the poor’s positive psychology, such that the positive impact of CEO’s poverty experience on CSR will be strengthened for firms with well-educated CEOs. We thus propose and test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

A CEO’s early-life poverty experience has a stronger positive effect on CSR performance among well-educated CEOs.

The Moderating Effect of the CEO’s Power

Power is a tool that not only can be used to influence others to do or believe something that they otherwise would not but also allows CEOs to mobilize resources to direct a strategic action (Walls & Berrone, 2017). Power can regulate the relationship between poverty experience and CSR by influencing CEO’s autonomy to decision-making, meaning in life, and social expectation.

As proposed before, the pursuit of the life meaning of “acting on behalf of others in the large world” and the promotion of self-efficacy that should help others are the crucial elements for the poor to escape extreme material shortage and help them to gradually become successful (Cotton Bronk et al., 2009). With their own efforts, the once-poor CEOs have gained more and more power, which has already changed their fates and enabled them to gradually satisfy their physiological, safety-based, emotional belonging, and respect needs. At this time, only by meeting their higher-level incentive needs can realize their life ideals and aspirations. Based on their emotional experience of getting out of woods and achieving success, developing their roles as anticipated by society and actively engaging in prosocial activities as they did in hard times of those years is the most familiar and effective way for CEOs who have experienced poverty to further meet their need for self-realization in a broader scope (Hofstede, 1984). Thus, power, in turn, will stimulate and deepen the emotions of CEOs who have experienced poverty to realize the meaning of life through prosocial behavior as before.

In addition, the poor are at the bottom of society and have long been at an absolute disadvantage in terms of money, power and social status. CEOs born in poverty need to make much more efforts to gain present power and achievements than those well born CEOs. More intense life contrasts make once-poor CEOs more aware of the difficulty of gaining power and more afraid of losing because they have experienced the pain after losing, which makes them more appreciative of their current life. While with increasing power, CEOs are more likely to be concerned by the public, and thus face higher social expectation and pressure to prosocial behaviors (Singh, 2009). When once-poor CEOs expect to follow their personal moral and emotional experiences to fulfill more CSR, then, not only the reputation pressure brought by the enhancement of power can further intensify this belief for the purpose of maintaining their hard-won social status, but also the expectation from the public will make CEOs feel a strong sense of social mission, which further deepens their prosocial psychology of serving the society formed by early-life poverty experience (Jirsaraie et al., 2019).

Furthermore, according to the principal-agent theory, the CEO, as the agent of the shareholders, needs to serve shareholders’ interests. Although CEOs are the final decision-makers, their personal decision-making is not entirely based on their own will. However, sufficient power makes the CEOs more likely to direct the firm toward specific goals according to their “way” and emotions (Greve & Mitsuhashi, 2007). Therefore, only when the power of CEOs is large enough, they have the ability to inject the prosocial emotions and values formed by early-life poverty experience into the company’s decision-making, otherwise such prosocial decisions are likely to be denied by other members of the senior management team (SMT) and the board of directors. On the one hand, informal power—which results from their personal, superior knowledge and expertise—can compel other senior managements to believe that the CEO’s decision-making of CSR is based on professional experience and determined after rational consideration, which will be beneficial to the interests of the company rather than just out of personal emotion (Lines, 2007). On the other hand, formal power—which is derived from the CEOs’ ability to reward or coerce others by way of their formal position, charter, and hierarchy in the organization—allows CEOs to control the flow and distribution of specific resources in a top-down manner (Peiró & Meliá, 2003), and thus gives CEOs more freedom to engage in CSR activities in accordance with their prosocial moral feelings caused by their poverty experience. This suggests that the slight power reduces the influence of COEs’ personal emotions in company’s decision-making, resulting in the positive impact of CEOs’ poverty experience on corporate social actions will be weakened. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

A CEO’s power positively moderates the association between his or her poverty experience and CSR.

The Different Impacts of Poverty Experience on Key Stakeholder- and Community-Related CSR

Traditionally, researchers examining the antecedents and consequences of CSR have treated them as an aggregate variable, encompassing all of a firm’s CSR activities. However, CSR is a multi-faceted construct, with various types, such as environment, product, diversity, corporate governance, and employee-based socially responsible efforts (Mishra & Modi, 2016). Each social dimension has its defining features, an aggregate CSR score may not accurately depict a firm’s engagement in CSR activities (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). Wang et al. (2016) and Al-Shammari et al. (2019) posited that the size, proximity, activism, and importance to the firm of stakeholders vary; their visibility and magnitude of effects also vary. The upper echelons theory describes senior leaders’ characteristics as useful in inferring the stimuli to which they are most sensitive, the opportunities they recognize, their interpretations of task-related discussions, and the stakeholders they prioritize (Carpenter et al., 2004; Heyden et al., 2017; Reimer et al., 2018). Thus, firms may emphasize different dimensions of CSR based on the characteristics of CEOs and their SMTs.

A firm’s CSR can be categorized in terms of its stakeholders, or specifically, key stakeholder-based CSR, such as employee-, environment-, consumer-, and investor-oriented activities, and community-based CSR, such as philanthropic contributions and community-oriented activities. These stakeholders more easily determine the dynamics of the relationships between a particular dimension of CSR and its determinants. Lim and DeSteno (2019) demonstrated that considering the sometimes aversive and costly nature of empathy and compassion, people are selective about whom they choose to show sympathy to. Effective responses are more likely to be evoked when information is presented in a visual form (i.e., directly and individualized) (Vollhardt, 2009). Key stakeholder-based CSR appears to be directed at specific stakeholder groups that are directly related to the enterprises and even have frequent contact with the CEOs; however, community-based CSR in general is less focused and has no direct contact with the CEOs (Mishra & Modi, 2016). Compared with an external stakeholder, such as the community, the stakeholders directly related to the enterprises are more likely to be paid attention by the CEOs and more likely to cause a visual impact on CEOs’ emotion, which leads to the stronger empathy of the CEOs for key stakeholders. Additionally, Piff et al. (2010) proposed that although lower-class individuals may report less trust in others in general, in interpersonal situations involving actual behavior directed at specific individuals, especially those belonging to the same group, lower-class individuals are more concerned with others’ welfare and exhibit more trust and prosociality. People volunteer more when they have strong social ties to the people they serve (Eckstein, 2001).

Moreover, because community-based CSR can garner greater attention from larger audiences (Wang et al., 2008), the type of CSR is usually used as a tool to improve an enterprise’s image and ease its financial constraints (Petrenko et al., 2016), especially in China, where the mindset of corporate donation differs from that of Western countries. For example, on May 12, 2008, China experienced a massive earthquake in Wenchuan County, which cost many lives and caused much damage. One of the largest and most profitable real estate firms in China, Vanke, donated only RMB 2 million. Shi Wang, the chairman of the board of Vanke, in responding to public criticism that the donation was too small, defended the company’s behavior by arguing that “RMB 2 million is sufficient.” Not only the stock price dropped 12% in the following 5 days, but Wang’s ethics were also widely questioned by the public (Su et al., 2020). Therefore, community-based CSR can be impure altruism, as even a charitable corporate donation is likely to enhance managers’ self-interests. According to the ingroup or familiarity, if CEOs who have experienced poverty take on CSR activities because of empathy, they are more likely to impose their true feelings on the stakeholders to whom they are directly connected, such as family members, friends, partners, and their own ethnic group. These arguments lead to our next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

A CEO’s poverty experience has a greater impact on key stakeholder-oriented than community-oriented CSR.

Research Design

Sample and Data

We test the hypotheses by sampling Chinese-listed companies representing all sectors except for financial services for the period from 2006 to 2017, as Chinese-listed companies first disclosed CSR information in 2006. We began with a list of CEOs derived from the Wind and China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) databases, and merged the data from various sources, such as news interviews, CEOs’ autobiographies, and websites. Data on firms’ CSR measures were obtained from Hexun.net. The CSMAR and Wind databases provided financial and industry affiliation data, and data on poorer and wealthier areas are derived from the National Bureau of Statistics.

We exclude firms with missing information on the CEO’s poverty experience, CSR scores, and control variables. Because some enterprises fail to disclose CSR reports, some of the CSR dimensions of these firms cannot be evaluated and are assigned a value of zero, which may affect the validity of the CSR construction in this paper. Therefore, we eliminate the samples with a stakeholder dimension assigned 0. Additionally, we control for outlier effects by trimming all the variables at the top and bottom 1%. This procedure leads to a final sample of 5921 firm-year observations from 1035 unique firms with non-missing control variables.

Measures

CSR Score

There are several methods for estimating CSR, including analysis of annual reports, reputation indices, the toxics release inventory (TRI), generosity indices, questionnaires, and CSR databases. However, the reputation index has always been criticized for its subjectivity and fairness (Fryxell & Wang, 1994), and the TRI and the generosity index reflect only a few of the factors that constitute CSR (Walker, 2010). In addition, questionnaire respondents tend to be the internal staff of firms, who may have motives for magnifying the CSR of their own firms (Ruf et al., 2001). Measuring CSR based on a widely accepted database, i.e., KLD, is typically preferred because of the database’s objectivity and comprehensiveness. In China, CSR scores from Hexun.net, which is a financial and economic website specialized in financial information data analysis, are widely accepted. Based on stakeholder theory, an index assessing CSR reagarding five stakeholder groups, including investors, employees, community, customers and suppliers, and the environment, was developed by Hexun. The five indicators are subdivided into 13 secondary and 37 third-level indicators, for example, investor-oriented CSR consists of profitability, solvency, return, credit and innovation, employee-oriented CSR consists of performance, safety and caring for employees, supplier- and customer-related CSR includes product quality, after-sale service, integrity and reciprocity, environment-oriented CSR includes environmental governance, and community-oriented CSR consists of contributing value. Moreover, according to the difference in the importance of the responsibilities of each stakeholder in different industries, Hexun.net also constructs heterogeneous weights for the five stakeholders for different industries.Footnote 1 Based on information disclosure data and a network survey, the weighted average method is used to measure the CSR scores of listed companies. The summed scores for CSR regarding the five stakeholder groups constitute our CSR proxy.

The CEO’s Experience with Poverty and Wealth

-

(1)

Poverty in the CEO’s hometown (CEO_Poverty). We measure the economic situation in the CEO’s hometown using a list of key counties for national poverty alleviation from the State Council’s Poverty Alleviation Office. The State Council has updated the list three times—in 1994, 2001, and 2012—with a relatively stable total maintained in 592 counties, including county-level administrative unit districts, banners, and county-level cities.Footnote 2 We compare the CEO’s birthplace information with the latest list of poverty counties, from 2012. The CEO_Poverty dummy variable equals one if the CEO was born in a poor county, and zero otherwise. In addition, by searching for biographies, interviews, resumes and other online news for each CEO in the chosen sample, we further exclude CEOs who explicitly mentioned that they had left their birthplace before adulthood. The first revised list of poor counties in 1994 is used for a robustness test later.

-

(2)

The CEO’s childhood experience with famine (CEO_Famine). An old proverb states that “three years look big; seven watch the old.” Paulus and Moore (2012) and Machell et al. (2016) proposed that prosocial disposition tends to formalize before adulthood and can even be found in the first year of life. Thus, childhood and adolescence are critical times in understanding the world, preserving permanent memories, and forming one’s character. China’s Great Famine (1959–1961) was one of the most devastating catastrophes in human history, as millions of people, many of whom were young children, died of starvation, malnutrition, and diseases related to food shortages. As the period of this famine also overlaps some CEOs’ lives, we further consider whether the CEO experienced the Great Famine before adulthood as another proxy for poverty experience.

Considering the continuity of individual psychological development, we choose a range from birth to age 18 years as the time range. Additionally, as noted by Benmelech and Frydman (2015), age may be of particularly important in the correlation between personal experiences and firm outcomes. The relationships between poverty experience and prosocial behavior have been proved to be influenced by the timing of the poverty experience. To separate the effect of having experienced poverty from a pure age effect, according to Feng and Johansson (2018), we divide the age range of CEOs who experienced the Great Famine into four groups: 0 to 2 years old, 3 to 5 years old, 6 to 12 years old, and 13 to 18 years old. Specifically, the CEO_Famine0–2 equals one if the CEO’s date of birth is between 1958 and 1961, and zero otherwise. CEO_Famine3–5 equals one if the CEO’s date of birth is between 1955 and 1957, and zero otherwise. CEO_Famine6-12 equals one if the CEO’s date of birth is between 1948 and 1954, and zero otherwise. CEO_Famine13–18 equals one if the CEO’s date of birth is between 1942 and 1947, and zero otherwise. In addition, it could be argued that the Great Chinese Famine primarily took place in rural areas and that this in turn, may affect the findings. Therefore, we drop all CEOs we identified as born in urban areas.

-

(3)

The CEO’s early life in a wealthy environment (CEO_Rich). We determine whether the CEO’s hometown is in one of the top 100 counties in China, a list selected and released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) before 2006, and then by the Zhongjun Research Institute. The comprehensive social and economic development of the top 100 counties is measured in terms of three aspects, including development level, development vitality, and development potential. We consider the list authoritative and use the latest data on China’s top 100 counties as issued by the NBS in 2005 to measure whether a CEO’s hometown is wealthy. The CEO_Rich variable equals one if the CEO was born in a top 100 county, and zero otherwise. Additionally, by searching for the information on CEOs’ birthplace that we obtain from news sources, we also exclude CEOs who explicitly mentioned that they left their birthplace before adulthood.

Moderating Variables

-

(1)

The CEO’s power (CEO_Power). Previous studies use different dimensions as proxies of CEO power, such as CEOs’ duality (Jackling & Johl, 2009), ownership (Veprauskaite & Adams, 2013), tenure (Bernard et al., 2018), and remuneration (Jiraporn & Chintrakarn, 2013). Although no single measure is likely to capture every possible dimension of CEO power, we developed an index to measure this power based on work by Finkelstein (1992) and Muttakin et al. (2018). Our CEO power index is comprised of four different dimensions to test the influence of CEO power on the level of CSR. Our approach to developing a CEO power index to capture different dimensions is consistent with Veprauskaite and Adams’ (2013) work. The index’s dimensions include the CEO’s duality, ownership, tenure, and status.

We developed the power index by first creating scores for each of the four power dimensions using a dichotomous procedure. For example, a dummy variable equals one if a firm’s CEO is also a chairperson, and zero otherwise. Similarly, a dummy variable equals one if the largest shareholder ownership of a firm is below the median ownership, and zero otherwise. A dummy variable equals one if the CEO’s tenure is above the median, and zero otherwise. A dummy variable also equals one if the CEO is a delegate of the National People’s Congress (NPC)Footnote 3 or the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC),Footnote 4 or was formerly a government official, and zero otherwise.

Considering the influence of a single indicator focuses on one aspect of power, it may not only fully reflect the CEO power but also face the endogenous problem caused by the omission of important variables. However, if more power variables are put into the model for a more comprehensive multi-dimensional study of the impact of CEO power, it is very likely to produce multicollinearity problems. Therefore, we further use principal component analysis (PCA) to calculate the comprehensive score of CEO power in the sample. The common factors are determined based on the eigenvalue that is greater than or equal to one, and the variance contribution rate of each principal component is set as the weight.

-

(2)

The CEO’s educational background (CEO_Edu). We follow Xu and Li’s (2016) work by using a dummy variable that equals one if the CEO graduated from a 985 collegeFootnote 5 or an overseas college, and zero otherwise.

Control Variables

To control for various factors that can confound the relation between CEO experiences and CSR performance, we include a number of firm- and CEO-level controls in the tests. We briefly discuss these variables below and their detailed definitions are provided in Appendix Table 12. The firm-level control variables include size (Size), return on assets (Roa), leverage (Lev), advertising expenditure (Sellsexp), and market-to-book ratio (MB). We also control for R&D expenses (RD) and cash flow from operations (Cash_flow), because firms with higher R&D expenses invest more in CSR and firms with more cash can afford to conduct more CSR activities (Lys et al., 2015). We also control for the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) because previous studies found that market competition could stimulate firms to engage in CSR to attract customers (Deng et al., 2013). Additionally, we control for the level of marketization of the province where the company is located, measured by the marketization index (Market) based on Fan et al. (2011). For CEO-level controls, we include the proportion of outside directors (Outdir) and a gender dummy (Female), which equals one if the CEO is female. Previous literature shows that firms with female CEOs are associated with better CSR performance (Manner, 2010; Tang et al., 2015).

Research Model

We use a regression analysis to test the effect of a poor or wealthy environment experienced by CEOs in their early years on the level of CSR. We test assumptions underlying the regression model for multicollinearity based on a correlation matrix and the variance inflation factor. None of the variables has a variance inflation factor in excess of 5, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a problem in interpreting the regression results. The regression is specified as follows:

We then test the effects of the CEO power and educational level by separately adding the interaction between CEO_Power and CEO_Edu to Model 1, as follows:

where CEO is defined as several proxies for a poor or wealthy environment experienced by CEOs, including CEO_Poverty, CEO_Famine, and CEO_Rich. The CSR Score is defined as a firm’s overall CSR performance and all aspects of CSR. The regression includes a firm’s CSR Score in the previous year to avoid any forward-looking bias, as previous studies suggested that CSR activities are serially correlated. The current CSR Score may be partially determined by its previous levels (Tang et al., 2015). The other control variables are as previously discussed. We consider year-, firm-, and industry-fixed effects to control for any common trends in the CSR Score over time and between firms or industries.

Additionally, a key problem in regression analyses involves overcoming variables’ endogeneity, which may occur with omitted variables and simultaneous causality. A CEO who has experienced poverty may lead to a higher CSR score. However, there is a distinct possibility that a company that is more socially responsible is likely to hire a CEO who came from a poor community. Moreover, although we have added as many control variables as possible to measure CSR, in many cases, some important enterprise characteristics may be difficult to be captured. Therefore, we adopt the two-stage least squares method (2SLS) for all models, which allows us to control for endogeneity by using instrument variables (IVs). Specially, the average level of the CEO’s poverty or wealth experience of other enterprises in the same industry (IV1) and the average GDP of the region in which the CEO lived before adulthood (IV2) are used as instruments in the equations.

Descriptive Statistics

Panel A in Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the key variables used in the main test. The variable CSR Score has a mean of 0.978 and a standard deviation of 0.242. Among the entire sample, 11.9% of CEOs were born in poor counties, 7.1% grew up in wealthy environments, and 55.4% experienced the Great Famine before adulthood. The other variables’ descriptive statistics appear to be within reasonable ranges and are comparable with those in previous studies (e.g., Al-Shammari et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2019).

Panel B in Table 1 compares the descriptive statistics of CSR for CEOs who experienced poor or wealthy environments. The T test and Wilcoxon Z test results indicate that the levels of CSR for CEOs from poor counties are statistically significantly higher than those of other CEOs, and the level of CSR from CEOs who experienced the Great Famine is also higher. However, whether the CEO is from the top 100 counties has no statistically significant impact on the level of CSR. The descriptive statistical results support Hypothesis 1.

Table 2 reports the main variables’ univariate correlations. The correlation matrix demonstrates that the CEO’s experiences with poverty (CEO_Poverty and CEO_Famine) and wealth (CEO_Rich) positively and negatively correlate with the CSR performance level (CSR Score), respectively. In addition, CSR Score is negatively correlated with leverage (Lev) and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) and is positively correlated with all other variables.

Results

The CEO’s Poverty Experience and Socially Responsible Activities

Hypothesis 1 predicts a positive relationship between CEOs’ experiences of living in a poor environment and CSR performance. Table 3 displays the results of the second stage from regressing the hypothesized variables on the level of CSR performance. All columns control for year-, firm-, and industry-fixed effects to avoid any common trends in the CSR score over time or between firms or industries. As shown in Table 3, not all of the results of the Sargan test and the Basmann test are significant at the 10% level, whereas all the results of the Wu–Hausman test and the Durbin–Wu–Hausman are significant at the 1% level, suggesting that an endogeneity problem exists between CEOs’ experiences of poverty or wealth and CSR performance, and that at least one instrument is an exogenous variable. Additionally, the Gragg-Donald Wald F values of the first stage are all > 10, and the coefficients of the instruments are all significant at least at the 5% level, suggesting that the two instruments are effective and highly correlated with the endogenous variables.

Model 1 explores the effect of the CEO’s birth in poor counties (CEO_Poverty) on CSR performance. Consistent with our prediction, a statistically significant, positive relationship exists between CEO_Poverty and CSR performance. The coefficient of CEO_Poverty is 0.447, which is significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the CEO’s birth in poor counties is significantly and positively associated with the firm’s CSR performance. Additionally, according to the age at which the CEOs experienced the Great Famine, Models 2 use an alternative definition for CEOs’ poverty experience; specifically, we replace CEO_Poverty with CEO_Famine0–2, CEO_Famine3–5, CEO_Famine6–12, and CEO_Famine13–18. We again document a positive and significant coefficient for CEO_Famine6–12 and CEO_Famine13–18 at the 1% level (0.399 and 0.487); however, the coefficients of CEO_Famine0–2 and CEO_Famine3–5 are positive, but not significant (0.068 and 0.070). The results suggest that for firms managed by CEOs who were between 6 and 18 years old at the time of the Great Famine exhibit a statistically significant and positive relationship between experience of the famine and CSR performance. These findings support the hypothesis that CEOs who lived in a poor environment during their younger years tend to make more altruistic decisions. However, due to immature awareness of the world and limited memory, the CEOs who lived through the Great Famine when they were very young (under 6 years old) are less likely to carry out prosocial behavior. These results are consistent with our Hypothesis 1 and suggest that having lived through a poverty experience such as a severe famine during one’s younger years seems to affect individuals’ value system. The experience promotes integrity and ethical behavior, such as engaging in more socially responsible activities.

This paper primarily focuses on whether CEOs who used to live in poverty have a stronger awareness of CSR. However, one compelling question differs from the poverty experience: Will CEOs who grow up in a relatively affluent environment exhibit better CSR performance? Model 3 further investigates the effect of the CEO’s experience with wealth (CEO_Rich) on CSR performance (CSR Score). We document a negative coefficient for the CEO’s wealthy experience variable (− 0.038), but it is not significant at the 10% level. The results indicate that CEOs who grew up in a wealthier environment differ from CEOs who experienced poverty; whether they were raised in a wealthy environment has no significant impact on their later CSR awareness. We interpret this result by combining the comparison tests as noted in Table 1 to determine that CEOs born in wealthier areas react less intensely to all emotional stimuli and often lack a deeper understanding of the hardships of life. Consequently, they lack the real moral and emotional experience and the internal altruistic motivation to fulfill their social responsibilities. The decision they make are more rational based on the balance of interests (Côté et al., 2013). Therefore, their CSR behaviors are driven by external rather than altruistic motivations, such as establishing reputation capital to seek economic benefit, or in line with institutional norms to seek political resources (Dai et al., 2014).

Additionally, all models’ coefficients of CSR Score in year (t − 1) are positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that a firm’s previous CSR performance significantly impacts the firm’s current CSR performance. The coefficients of the remaining control variables are consistent with our expectations.

Are CEOs Who Experienced Poverty Generous to Themselves?

As we proposed, the motivation of CSR activities is multi-dimensional, which may be motivated by altruism, or it may be based on the balance of interests. Our previous empirical results revealed that CEOs who experienced poverty focus more on other stakeholders’ rights and interests and are more generous than other CEOs, thus resulting in more prosocial behaviors. But is this generosity really altruistic? Altruism involves respecting others’ interests and not sacrificing others’ interest for one’s own, which leads to an increase in prosocial behaviors and a decrease in antisocial behaviors. Individuals with high altruism are not only willing to assist others but are more reluctant to engage in harmful behaviors (Swap, 1991). Thus, to test that the positive relationship between poverty experience and various prosocial behaviors is caused by altruism, we further investigate whether CEOs who experienced poverty are generous to themselves as well as to others. Further, we take the level of CEO perks as a dependent variable, which includes travel expenses (ENT_revt, measured as the sum of travel, automobile, and business entertainment expenses) and the management team’s expense rate (Adminexp_revt). Table 4 presents the results of the second stage.

As Table 4 reveals, the coefficients of CEO_Poverty, CEO_Famine6–12, and CEO_Famine13–18 are all negative and significant at the 5% level. However, the coefficients of CEO_Famine0–2 and CEO_Famine3–5 are all negative, but not statistically significant, indicating that except for the CEOs who experienced the Great Famine before the age of 6, the other CEOs who experienced poverty had lower on-the-job consumption. That is, CEOs who experienced poverty are more frugal to themselves than generous. In summary, the early life poverty experience aroused the CEOs’ awareness of CSR; this not only makes them more compassionate and more aware of helping others but also reduces their probability of engaging in corporate socially irresponsible (CSiR) activities, such as on-the-job consumption, further confirming the altruistic motivation toward CSR for CEOs who have experienced poverty.

The Moderating Effect of CEO Educational Background and Power

We test Hypotheses 2 and 3 by using Eq. (2) and add an interaction variable between CEO_Edu (CEO_Power) and the proxy variables for poverty experience in the analysis. Table 5 illustrates the results. Consistent with the previous results, except for CEO_Famine0–2 and CEO_Famine3–5, we also document a positive (0.203, 0.302, and 0.347, respectively) and significant coefficient (at the 5% level) for the proxy variables for poverty experience. Additionally, regarding this model’s key variables, we find that the coefficients of CEO_Poverty × CEO_Edu, CEO_Famine6–12 × CEO_Edu, CEO_Famine13–18 × CEO_Edu, CEO_Poverty × CEO_Power, CEO_Famine6–12 × CEO_Power, and CEO_Famine13–18 × CEO_Power are all positive (0.298, 0.231, 0.279, 0.143, 0.153, and 0.211) and significant at the 5% level. However, other interaction variables are positive but not significant, suggesting that except for experiencing the Great Famine before 6 years old, CEO power and education positively moderate the relationship between CEOs’ poverty experience and CSR performance. In other words, CEO power and a good educational background strengthen the effect CEOs’ poverty experience on CSR performance. Thus, Hypotheses 2 and 3 are supported.

These results also indicate that CEO power is negatively (− 0.025 and − 0.043, respectively) and significantly (at least at the 10% level) associated with CSR performance. This suggests that firms with more powerful CEOs engage in fewer socially responsible activities. Further, this is consistent with work by Walls and Berrone (2017) and Muttakin et al. (2018), which posited that the self-benefitting, rational CEO has greater power. This may enable him or her to make decisions that do not consider stakeholders’ interests, resulting in reduced attention to and involvement in social or community activities. However, when the CEOs have a strong altruistic tendency, the power they have can help them to better engage in prosocial behaviors.

The Different Impacts of CEOs’ Poverty Experience on Community- and Key Stakeholder-Oriented CSR

Disaggregating CSR into different categories in terms of stakeholders enables an easier determination of the dynamics of relationships between a particular dimension of CSR and its determinants. Thus, we follow the work by Mishra and Modi (2016) and divide the overall CSR scores into two broad categories: community-oriented CSR (including community responsibility) and key stakeholder-oriented CSR (including investors, employees, environment, customers, and supplier responsibilities). We then recount the scores for each of the two CSR aspects to test Hypothesis 4 and further examine the effects of CEOs’ poverty experience on each of these aspects. To compare the impact of poverty experience on the two types of social responsibilities, we standardized all the coefficients before the regression. Table 6 presents the results of the second stage. Models 1–2 display the results for the regressions of various CEO poverty experiences on community-based CSR, while Models 3–4 report the results for key stakeholder-based CSR.

Consistent with our previous findings, a statistically significant and positive relationship exists between CEO poverty experience and CSR performance, regardless of the key stakeholder- or community-oriented aspect. However, the coefficients for CEO poverty experience are all small for community-oriented CSR (0.737, 0.302, 0.366, 0.869, and 0.902, respectively) than key stakeholder-oriented CSR (0.798, 0.363, 0.412, 0.929, and 1.003, respectively). Except for CEO_Famine0–2 and CEO_Famine3–5, the coefficients for the other independent variables are all significant at least at the 10% level. This suggests that CEOs’ poverty experience is more related to key stakeholder-oriented CSR activities, confirming what we proposed in Hypothesis 4: that individuals who have experienced poverty are more likely to show compassion and prosocial behaviors toward those who are more closely related to them and are more likely to have emotional impact on them.

Robustness Test

-

(1)

An Alternative Proxy for CEO Poverty Experience

Considering that the National Bureau of Statistics has adjusted its authoritative lists of national poor counties and top 100 counties several times, the previous regression models adopt the latest versions (2005 and 2012, respectively). We select the earliest list that can be found at present—or the 1994 and 2004 versions of the poor and top 100 counties, respectively—to re-identify the economic situation surrounding the CEO’s birthplace. We also eliminate the CEOs who left their hometown before they reached adulthood. Additionally, we readjust the judgment of CEOs’ early-life Great Famine experience. As metropolitan areas were less affected by the Great Chinese Famine, political or economic centers, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin, were likely supplied with more grain to maintain social stability. As a result, people living in these areas were less affected by the famine. In the previous study, we eliminated the sample of CEOs who were born in an urban area; therefore, in the robustness test we exclude CEOs born in these three municipalities. In addition, as the length of the CEO’s poverty period affects his or her tendency toward empathy in adulthood, we set a new independent variable: CEO_Intersection, which equals 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively, representing that the CEO has not experienced (or experienced 1, 2, and 3 years) of the Great Famine before adulthood (0–18 years old). Table 7 reports the results.

Table 7 Robust tests: alternative proxy for CEOs’ poverty experience Confirming the previous results, except for CEO_Famine0–2 and CEO_Famine3–5, the coefficients of all variables proxies for CEO poverty are positive and significant at the 5% level, although this is still negative but not significant for CEO_Rich. The results support the hypothesis and suggest that CEO poverty experienced is positively related to a firm’s CSR performance. Additionally, the longer the CEO experienced poverty, the better the firm’s CSR performance.

-

(2)

Perceived Poverty

Poverty can be divided into two categories: de facto and perceived poverty (Koczan, 2016). Our previous measurement of CEO’s poverty experience was based on de facto poverty. We use perceived poverty as a proxy variable to examine the robustness of the results. We capture the CEO’s perceived poverty by regarding the top 10 provinces in terms of annual average GDP as wealthy provinces and the bottom 10 provinces as poor. We use mean comparison and nonparametric tests to compare the differences in CSR between CEOs born in poor counties in wealthy provinces and in poor counties in poor provinces. We reorganized the samples to ultimately gain 3962 observations, including 933 CEOs from poor counties in wealthy areas and 3029 CEOs from poor counties in poor areas. Table 8 displays the comparison test results.

Table 8 Robust tests: comparison tests of feeling poor We find that although the environmental contrast is stronger, CEOs born in poor counties in wealthy provinces do not have a stronger sense of poverty than CEOs who were born in poor counties in poor provinces. Therefore, this will not significantly impact their CSR decision-making in adulthood.

-

(3)

An Alternative Proxy for CSR

Although Hexun.net has developed a measure of firms’ commitment to CSR, the CSR scores primarily depend on firm disclosures, and the measurement process may be insufficiently objective. Therefore, we also examine the results’ robustness using Rankins’ CSR ratings, which are provided by an independent third-party organization offering research and consulting services to investors interested in integrating social responsibility features in their investment decisions. Similar to Hexun.net, Rankins’ data also mainly come from the information disclosed by the enterprise itself and Internet public data, such as CSR reports, environmental reports, annual reports, articles of association, etc. However, different from Hexun’s measurement of CSR from the perspective of stakeholders, Rankins measures CSR performance based on the Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) index, which includes environment (E, 11 key issues, such as climate change, wastewater discharge, and poisonous and harmful gas emissions, among others), society (S, 11 key issues, such as employee labor management, human resource management, supply chain management, product safety, and charity, among others), and corporate governance (G, including board effectiveness, executive compensation, ESG risk management, and business ethics). Although the Rankins CSR ratings are based only on CSR reports, do not later adjust their data according to reliable news from other sources, and ignore the difference in the weight of each responsibility, many in China nevertheless accept these scores. The results reported in Table 9 are consistent with our main findings and conclusions.

Table 9 Robust tests: alternative proxy for CSR -

(4)

Self-selection Bias

We proposed that having a CEO with a poor background leads to a higher CSR score. There is a distinct possibility, however, that a company that is more socially responsible is likely to hire a CEO with a poor background. Although we used 2SLS and controlled for firm-fixed effects, to further examine that the self-selection bias does not affect the validity of our main conclusion, we choose 2 years before and after the CEO changes (− 2, 2) to examine changes in CSR. We set two new variables, including one to indicate newly hired CEOs who have experienced poverty (CEO_New) and one to indicate fired CEOs who experienced poverty (CEO_Quit). Further, Post is a dummy variable that equals one during the current and subsequent year of CEO changes, and zero during the 2 years before the CEO changes. We also use the propensity score-matching method to construct a control group with similar characteristics for the treatment sample of new CEOs who experienced poverty and fired CEOs who experienced poverty, respectively. We then use the difference-in-differences method to compare the CSR Score before and after the change. Table 10 reports the results.

Table 10 Robust tests: self-selection bias We find that except for newly hired CEOs who experienced the Great Famine before they were 6 years old, the coefficients of CEO_New × Post are all positive and significant at the 5% level, suggesting that the company’s CSR Score improves significantly when the company changes its CEO to one who experienced poverty. In contrast, except for CEO_Famine0–2 and CEO_Famine3–5, the coefficients of CEO_Quit × Post are all significantly negative at least at the 5% level, suggesting that CSR Scores declines significantly when the company changes its CEO to one without poverty experience. Additionally, regardless of examining the moderating effect of CEO power and educational background, or the difference between community- and key stakeholder-oriented CSR, our conclusions are consistent with the previous findings. We discover that after controlling the self-selection bias, the results from CEO changes further support the previous results.

-

(5)

Endogeneity with Other Regression Method

A key problem in regression analyses involves overcoming variables’ endogeneity. Although we adopted 2SLS as the main regression model, the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test shows that the generalized method of moments (GMM) may be more efficient as it rejects the original hypothesis at the significant level of 1%. To overcome the influence of heteroscedasticity on the results, we reselect GMM to analyze the models. Table 11 reports the results. We also find that except for CEO_Famine0–2 and CEO_Famine3–5 the coefficients of the proxies for CEO poverty are all positive and significant at least at the 5% level; and still negative but not significant for CEO_Rich. Moreover, the coefficients of interaction variables between CEO_Power (or CEO_Education) and various proxies for CEO poverty are still significantly positive at least at the level of 10%. By classifying social responsibility, we also find that the coefficients of independent variables are larger when the dependent variable is key stakeholder-oriented CSR, which further confirms our previous findings. Thus, the results still robustly control for endogeneity using a GMM specification.

Table 11 Robust tests: GMM

Discussion and Conclusion

Personal experience, especially adverse life experience, often has an important impact on CEOs’ psychology, cognition, and behavior long after the event, which cannot be ignored. This study aimed to examine the effects of CEO’s early-life poverty experiences on CSR performance in China. The findings reveal that CSR performance is positively associated with CEOs’ early-life experience in poverty, but we find no significant relationship between the CEO’s wealth experience and CSR. Additionally, the CEO power and education positively affect the relationship between the CEO’s poverty experience and CSR performance. Thus, although the CEO’s poverty experience can improve CSR practices, CEO power and a better educational background can further strengthen this possible improvement by guiding individual positive psychology and making CSR decisions more convincing. We also observed that CEOs who have experienced poverty are more likely to focus on key stakeholder-based than on community-based CSR activities. Moreover, the likelihood of socially irresponsible activities, such as on-the-job consumption, decreases for CEOs with painful poverty experiences, suggesting that once-poor CEOs engage in more socially responsible activities and fewer socially irresponsible activities, leading to better CSR performance.

The focus of extant literature on CSR motives has largely centered on the external determinants of CSR (Al-Shammari et al., 2019). Although external drivers are important in explaining a firm’s CSR, this exclusive focus on external drivers provides at best an incomplete picture of the drivers of a firm’s CSR activities. This paper addresses this gap in the literature and suggests that we should emphasize the motives of the organization’s key decision-maker—or specifically, the CEO—to explain not only the extent to which a firm engages in CSR but also the types of CSR activities a firm should emphasize. Additionally, this study demonstrated innovative ways to capture senior executives’ psychological traits, which are unobtrusive yet powerful. Given the difficulty of obtaining a sufficient number of truthful direct survey responses from CEOs using established inventories, examining the psychological impacts of CEOs’ early-life poverty experiences could possibly provide additional valid measurements among larger populations of CEOs. These findings provide additional support for works by Staub and Vollhardt (2008), Hayuni et al. (2019), and Lim and DeSteno (2016), among others, regarding the relationship between CEO experience and psychology. This study also verified what Biswas-Diener and Patterson’s (2011) and Vollhardt and Staub’s (2011) proposed, that a painful experience with poverty will also positively influences people’s psychology. This is indicated by people living in poverty are more likely to foster empathy tendency and a sense of efficacy to help, and establishes lofty life meaning, such that they engender compassion and altruism, which is characterized by exhibiting more prosocial behaviors and behavioral responses meant to assist others. When they have decision-making power, their specific experience and psychology compel their companies to engage in more CSR activities, which further demonstrates the potential altruistic motivation of CSR.

Extant research is characterized by inconclusive or contradictory results regarding the relationship between CSR and corporate financial performance (CFP). Although this study did not directly examine the performance implications of CSR, we believe this study provides important new insights regarding the CSR–CFP relationship. First, the results suggest that CEOs’ poverty experiences significantly drive firms’ CSR. Therefore, a firm may pursue CSR neither as a result of financial motivation nor out of a moral compulsion, but to satisfy the CEO’s psychological needs. CEOs may pursue CSR goals and commit excessive resources to CSR activities to satisfy a sympathetic need even if faced with negative performance implications, an explanation that transcends pure monetary considerations. Second, previous studies mostly used aggregate measures of CSR; disaggregating CSR into its components not only responds to the growing calls to unpack the dimensions of CSR (Wang & Choi, 2013; Wang et al., 2016) but also prove helpful in clarifying the conflicting results regarding CSR–firm performance relationships. CSR should be treated as a multi-dimensional construct, and that studies that use aggregate measures may not sufficiently capture the construct’s richness and complexity. We contend that conceptualizing CSR strategies as inherently multi-faceted explains why firms differ not only in their levels of CSR but also in their specific patterns of CSR strategies, such as which dimensions are emphasized. It could also balance the interests of those who matter to the organization instead of emphasizing some stakeholders and neglecting others, and spur discussions on the governance mechanisms needed to make necessary changes in a firm’s CSR strategies (Reimer et al., 2018).

Moreover, the upper echelons theory has been a major theoretical lens used to study CEOs and SMTs, and their effects on organizations. This research stream has significantly advanced our understanding of senior executives’ actions. In recent years, researchers of the upper echelons theory have increasingly emphasized psychological traits rather than their demographic proxies. Researchers have made significant advances in capturing important CEO characteristics, such as hubris (Tang et al., 2018a), political ideology (Briscoe et al., 2014), charisma (Wowak et al., 2016), and narcissism (Al-Shammari et al., 2019). Our research indirectly tests CEOs’ sympathy from the poverty experience perspective, which can provide an addition to this relatively new but growing research field.

It is noteworthy that our sample CEOs have roughly the same likelihood of experiencing poverty during their childhood as a typical member of China’s population. Thus, the likelihood of becoming a CEO seems to exist independent of one’s poverty experience, which suggests that these results may have broader implications beyond CEOs’ CSR. In this regard, the results may be important for research on the effects of life experiences on capital market participants’ behavior. In advocating for the positive outcomes of negative life events, such as living in poor environment; however, we in no way argue that adversity is good, or that one way to enhance compassion in society is to make more people suffer early in life. To the contrary, the whole function of compassion is to nudge people to reduce others’ suffering. Designing interventions and finding ways (e.g., education and social support) to guide more individuals from adverse experience to prosocial engagement may not only benefit disadvantaged members of society, but also help to build healthier communities and societies. When mobilizing governments and businesses to work together to address critical social issues such as poverty, the government should continue to advocate the concept of “helping the poor needs to help the heart first”, strengthen ideological and moral education and encourage social assistance, so as to help the poor, especially the children in poor, get rid of poverty ideologically and solve the problem of consciousness poverty at the source. This may greatly alleviate the negative impact of the lack of wealth and status in childhood on adults’ psychological cognition.

Additionally, our study is also relevant to firms that emphasize on their CSR performance. On the one hand, the choice of CEO plays a decisive role in a company’s development. Properly considering the social background and early-life experience in the appointment and assessment of CEOs is helpful for improving the selection and appointment system of senior managers. On the other hand, we also provide suggestions for the improvement of corporate governance mechanism. The deviation in belief and preference caused by managers’ early-life experience cannot be ignored when motivating CEOs; otherwise, the incentive mechanism is not optimal, which will further affect the company’s policy making and implementation. For example, it may be useful to link managers’ performance to some CSR indicators and employ incentive programs that have high tolerance of early failure and reward CEOs on their long-term successes so that their value in the labor market can also incorporate their ability to enhance CSR performance. This may be more motivating for CEOs with poverty experience, because their decisions are win–win that not only for the company’s interests, but more in line with their own personal moral feelings.