Abstract

We tested whether the impact of an organizational transgression on consumer sentiment differs depending on whether the organization is a nonprofit. Competing hypotheses were tested: (1) that people expect higher ethical standards from a nonprofit than a commercial organization, and so having this expectation violated generates a harsher response (the moral disillusionment hypothesis) and (2) that a nonprofit’s reputation as a moral entity buffers it against the negative consequences of transgressions (the moral insurance hypothesis). In three experiments (collective N = 1372) participants were told that an organization had engaged in fraud (Study 1), exploitation of women (Study 2), or unethical labor practices (Study 3). Consistent with the moral disillusionment hypothesis, decreases in consumer trust post-transgression were greater when the organization was described as nonprofit (compared to a commercial entity), an effect that was mediated by expectancy violations. This drop in trust then flowed through to consumer intentions (Study 1) and consumer word of mouth intentions (Studies 2 and 3). No support was found for the moral insurance hypothesis. Results confirm that nonprofits are penalized more harshly than commercial organizations when they breach consumer trust.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Nonprofit organizations play a unique role in sustaining the fabric of society: many have a core mission to increase inclusiveness, preserve equality, and protect the interests of society’s most vulnerable members. Furthermore, they deliver this mission in ways that cannot be substituted through commercial or government activity. It is through the provision of these services that nonprofits are viewed as “purveyors of good”, enabling them to develop a reservoir of community trust that fuels donations and volunteering (Bhattacharjee et al. 2017; Burt 2012; Lin-Hi et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2016).

As such, a threat to this sector—through trust breaches and the consequent reputational damage—represents a threat to the goal of constructing a fair society. It also represents a threat to the broader economy, given the sheer size and impact of the sector. In the U.S., for example, there are approximately 1.6 million registered nonprofits, which together employ 10% of the population. Furthermore, approximately 1 in 4 American adults do volunteer work within nonprofit contexts (Independent Sector 2018).

Obviously, the fact that an organization has a mission to serve and protect the community does not make them immune to scandal. Because the nonprofit sector faces significant pressure from the public to allocate their donations towards the delivery of goods and services, limited funds remain to ensure adequate regulation of their internal processes (Petrovits et al. 2011), leaving them vulnerable to fraud (Burt 2012; Holtfreter 2008). Furthermore, because nonprofits rely on donations from the public, they are more likely than commercial organizations to be held to high community standards in terms of fundraising practices (Gibelman and Gelman 2004), the handling and spending of donations (DiGangi 2016), and staff remuneration (Rahim 2005). Finally, because many nonprofits work with society’s most vulnerable, they may inadvertently attract people seeking opportunities to exploit others under a smokescreen of trust, for example through child sexual abuse (e.g., scandals surrounding the Catholic Church and Salvation Army), or the sexual exploitation of women and community members (e.g., Oxfam). These scandals have the potential to damage trust and, as a result, to impair the ability of the organizations to attract donations and to fulfill their mission.

A question that remains unanswered is whether the same trust breach has different consequences depending on whether it is conducted within a commercial organization or a nonprofit. Responding to calls for more psychological studies of business ethics (Islam 2019), the current paper reports three experiments that test whether (and why) the same transgression has a different effect when it is committed by a nonprofit compared to a commercial organization. Answering this question will enable nonprofits to better predict consumer responses to trust breaches, and so better equip them to know how to engage in trust repair efforts. Framing these studies are two competing sets of hypotheses, each supported by their own theoretical traditions. Both sets of hypotheses are predicated on the assumption that nonprofits will be seen as having a stronger moral reputation than commercial organizations, an assumption grounded in previous research (e.g., Aaker et al. 2010; Bhattacharjee et al. 2017). However, they differ in terms of what effects this moral reputation might have on news that trust has been breached. We review these hypotheses below.

The Moral Disillusionment Hypothesis

One theoretical position suggests that groups with strong moral reputations carry higher expectations of integrity, and thus nonprofits are held to higher moral benchmarks. Transgressions are particularly costly for them in terms of subsequent trust and consumer engagement because the moral injury is greater when it comes from an organization that “should know better”. We call this the moral disillusionment hypothesis.

Expectancy Violation Theory (EVT) offers a mechanism that might help explain the potential differential impact of trust breaches within commercial and nonprofit organizations. Initially used to analyze nonverbal communication processes, EVT has evolved, and has now been applied to violations of expectations in a range of contexts including organizational settings (e.g., Greitemeyer and Sagioglou 2018; Johnson 2012; Sohn and Lariscy 2015; Rhee and Haunschild 2006). EVT postulates that behaviors of an entity that deviate from existing expectations result in stronger negative re-evaluations of that entity (Burgoon and LePoire 1993). The theory also holds that the more the behavior deviates from initial expectations, the greater the perceived violation (Lin-Hi et al. 2014).

In the case of nonprofits, their moral reputations set clear expectations for how the public assume these organizations will behave. Therefore, in situations where nonprofits are involved in a transgression, EVT suggests that the public will experience a strong violation of expectations, resulting in more negative re-evaluations of such organizations. Because commercial organizations do not have the same moral reputations, their involvement in a transgression may not produce the same level of expectancy violation. As such, this theory lends support for the argument that following a transgression, nonprofits would experience greater damage to trust and consumer engagement than commercial organizations.

Some studies have drawn on EVT to account for evidence of “liability effects” or “boomerang effects” of good reputations. For example, Rhee and Haunschild (2006) found that highly reputed automobile firms suffered a greater market penalty after a product recall than did firms with a poor reputation. Using an experimental paradigm, Sohn and Lariscy (2015) examined trust in a game developing company after finding out the company had been charged with tax evasion and the selling of private information without permission. Although the results were mixed, there was some evidence that trust in the organization was lower when participants had been led to believe that the organization had a positive reputation. More recently, an analysis of U.S. media articles on oil spills from 1985 to 2016 showed that media are less likely to cover oil spills from organizations who are repeat offenders (i.e., organizations with a negative capability reputation in that context; Chandler et al. in press). The authors speculated that the effect is due to the media’s need for news to be “new”, ironically leading to more attention paid to oil spills from organizations with a reputation for integrity in that domain.

Suggestive evidence in favor of the moral disillusionment hypothesis has emerged on perceptions of sales techniques that could be considered high-pressure or manipulative. In two studies, Greitemeyer and Sagioglou (2018) showed that compliance techniques had a greater effect on the perceived morality of a nonprofit organization than when the same compliance techniques were used by a commercial entity. Consistent with EVT, these effects were mediated by perceptions of the sense that the compliance behaviors violated participants’ expectations of that organization.

In sum, based on EVT, we propose a moral disillusionment model of organizational transgressions. According to this model, when organizations (such as nonprofits) have a strong moral reputation, there is a higher expectancy that they will behave in ethical ways. Consequently, an ethical transgression will represent a greater expectancy violation when it is committed by a nonprofit than when the same transgression is committed by a commercial organization. This will result in a sharper decline in trust from pre- to post-transgression for the nonprofit, which in turn will flow through to a sharper decline in consumer intentions. These hypotheses are formalized as follows:

H1a

Decreases in trust and consumer intentions post-transgression (compared to pre-transgression) will be significantly greater for nonprofit than commercial organizations.

H1b

There will be a significant serial mediation model, such that the effects of organization type on (decreases in) trust will be mediated through expectancy violation, an effect that will then flow through to (decreases in) consumer intentions.

We note that the moral disillusionment model is agnostic about whether levels of trust and consumer intentions would differ between the nonprofit and the commercial organization post-transgression. Consistent with the perception of nonprofits as higher in integrity- and warmth-related traits (e.g., Aaker et al. 2010; Kinsky et al. 2014), it is likely that levels of trust and consumer intentions pre-transgression would be greater for a nonprofit compared to a commercial organization. Thus, depending on how dramatic the disillusionment effect is, the trust advantage that nonprofits enjoy prior to the transgression will be reduced, eliminated, or reversed, but the integrity of the disillusionment hypothesis does not rest on which of these outcomes emerges.

The Moral Insurance Hypothesis

An alternative possibility is that the strong moral reputation of nonprofits may protect them in the event of a transgression, acting as a “trust bank” that buffers them against the negative effects of scandal. Some support for this moral insurance hypothesis emerges from two parallel literatures: (1) on corporate social responsibility (CSR), and (2) on corporate reputation. Some studies have demonstrated that philanthropic and CSR activities help improve consumers’ responses to new product releases (Brown and Dacin 1997; Chernev and Blair 2015), improve future revenue and market value (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006), and help reduce losses when markets suffer a negative shock (Lins et al. 2017). Other research—mostly event studies that track the effects of events on the value of firms—suggests that CSR programs sometimes have insurance-like qualities: buffering firms from market backlash in the face of future negative events (Barnett et al. 2018; Flammer 2013; Godfrey et al. 2009; Janney and Gove 2011; Williams and Barrett 2000). Indeed, companies in controversial industries like tobacco, alcohol, or weapons manufacture can use CSR initiatives to offset financial or reputational penalties for their so-called “sinful” products (Cai et al. 2012). However, there is a significant caveat to these conclusions: where CSR efforts are seen as self-serving or insincere, there is evidence that the insurance-like qualities of CSR can be attenuated, eliminated, or even reversed (Chernev and Blair 2015; Oh et al. 2017; Yoon et al. 2006). We note that this research is focused exclusively on commercial organizations.

Related research points to corporate reputation as a valuable resource for buffering the company against an economic crisis (Jones et al. 2000). Furthermore, experimental work on post-scandal responses suggests that, if the company has a pre-existing reputation for product or service quality, people are more likely to trust the company after a scandal (Decker 2012), less likely to blame it for wrongdoing (Grunwald and Hempelmann 2010), and the company is less likely to lose brand equity (Dawar and Pillutla 2000; but see Folkes and Kamins 1999, for a counterpoint). Finally, consumers who have a stronger psychological commitment to a brand tend to be more loyal following a brand transgression (e.g., Ahluwalia et al. 2000; Sinha and Lu 2016), particularly when the transgression lies outside the implicit psychological contract consumers have with the brand (Montgomery et al. 2018). Extrapolating from this research, one could make the case that nonprofits’ commitment to social good—and the advantages that this brings in terms of moral reputation and consumer commitment—buffers such organizations against the negative consequences of trust breaches.

These studies evidence the notion that organizations’ good deeds can be stored as “trust deposits” and drawn on in times of crisis or scandal. The presumed psychological mechanisms for these effects have not been elaborated, and it is beyond the scope of this paper to examine them. However, extant theorizing in the social psychological literature suggests a number of processes can lead people to weight transgressions less heavily when the perceiver has a positive perception of—or loyalty toward—the transgressor. These processes include downplaying the harm caused by the transgression (Iyer et al. 2012), offering “benefit of the doubt” to the transgressor (Minto et al. 2016; Van Prooijen 2006), attributing the transgression to external factors rather than factors internal to the transgressor (Ariyanto et al. 2009), or by accelerating the process of forgiveness for a transgression (Barlow et al. 2015).

In sum, theory and research on CSR and corporate reputation lays the foundation for a moral insurance model of organizational transgressions. According to this model, the stronger an organization’s moral reputation, the more they will be protected from the negative effects of a one-off ethical transgression. As operationalized in the current context, this would mean that a nonprofit organization would see less of a decline in trust after a transgression than would a commercial organization that committed the same transgression. These effects of trust would then flow through to influence consumer intentions.

We formalize these predictions as follows:

H2a

Decreases in trust and consumer intentions post-transgression (compared to pre-transgression) will be significantly greater in commercial than nonprofit organizations.

H2b

Decreases in trust post-transgression (compared to pre-transgression) will mediate the effects of organization type on decreases in consumer intentions.

The Present Research

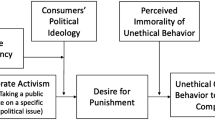

In three experiments, we exposed participants to a transgression and attributed it to either a commercial organization or a nonprofit. Transgressions included cases of fraud (Study 1), sexual exploitation of women (Study 2), and unethical labor practices (Study 3). In each study, we measured trust in the organization and consumer intentions to support the organization both before and after reading about the transgression. We also measured expectancy violation, a key mechanism that distinguishes the moral disillusionment model from the moral insurance model (see Fig. 1 for a conceptual model comparing the two sets of predictions).

As can be seen in Fig. 1, we also tested three potential moderators of the effects of organization type on downstream consequences of a transgression: the mission-relevance of the transgression (Study 2), the pre-existing reputation of the organization for competence (Study 3), and the extent to which the transgression implicated one or many people within the leadership team of the organization (Study 3). Theoretical reasoning for testing these moderators is discussed in the introduction sections of Studies 2 and 3 below.

Transparency Statement

Consistent with principles of research transparency, in each study we report all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures collected in the study. Sample size was prescribed in advance; there was no topping up of data after initial collection. Full stimulus materials for each study are available in the online supplementary file. Data and syntax files for each study can be accessed through the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/uawpv/?view_only=6054f8507e924c4babe269952ffa9662

Study 1

Study 1 provided an initial test of our competing hypotheses summarized above. Participants were introduced to an online fashion store, the profits for which were either privatized (commercial condition) or used for charitable purposes (nonprofit condition). After rating their levels of trust and intentions (pre-transgression), participants were then led to believe that senior people in the organization were guilty of fraud. We then re-measured trust and consumer intentions (post-transgression).

Participants and Design

U.S. participants (N = 341) were recruited through Prolific, an online crowdsourcing survey platform, in exchange for $1US. Embedded within the first bank of questions was an initial attention check measure (“To indicate you are reading these questions, click 2”). Five respondents who failed this check were excluded from analysis. A further six were removed from analysis as a result of failing a manipulation check (for details, see below). This resulted in a usable sample of 330 participants (Mage = 30.39 years, 50.3% male). Participants were randomly allocated to a 2 (Organization Type) × 2 (Time) mixed-groups design. The between-persons factors compared the Organization (nonprofit vs. commercial) and the within-person factor of Time compared responses immediately before the transgression information with responses immediately after the transgression information. The key outcome variables were trust in the organization’s integrity (trust), and intentions to engage with the organization’s products (consumer intentions).

Procedure and Materials

The survey was advertised to participants as being about online shopping preferences.

Manipulation of Organization Type

At the beginning of the survey, participants were presented with information about an online fashion store called GlobalDress (although GlobalDress is fictitious, it was presented to participants as real). Depending on the experimental condition, GlobalDress was described as either a commercial organization, or as a “charitable, not-for-profit” fashion store that matched “every item sold with a similar article of clothing to a person in need, for free.”

Manipulation Checks

Following this information, participants were asked a simple manipulation check. Those in the nonprofit condition answered “true” or “false” to the statement “GlobalDress is a charitable, not-for-profit organization”. Those in the commercial condition answered “true” or “false” to the statement “GlobalDress is an online fashion retailer”.

Transgression

After completing measures of trust and intentions (see below), participants were told that the CEO of GlobalDress and his former personal assistant had been found guilty of fraud, falsifying documents, misappropriating funds and giving false information. To reinforce the information, participants answered “true” or “false” to the statements “The CEO of GlobalDress stole $50,000 of the company's funds” and “The CEO of GlobalDress was found guilty of fraud”. Participants then completed the expectancy violation scale, before completing the trust and consumer intentions measures again. Trust and consumer intentions were presented in a randomized order both pre-transgression and post-transgression.

Measures

Trust was measured using a perceived integrity scale developed by Nakayachi and Watabe (2005). The items were: “this company is trustworthy”, “this company is honest”, “this company is reliable”, and “this company is irresponsible” (last item reverse scored; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).Footnote 1 This scale proved reliable both pre-transgression (α = 0.88) and post-transgression (α = 0.82).

Consumer Intentions

We measured consumer intentions using five items. The items were based on the “intention of usage” scale by Nakayachi and Watabe (2005), but adapted to refer to an online clothing store. Items were “I would buy their products”, “I would shop with them as long as they were comparable to others”, “If my family bought their products for me, I would use them”, “I would go to this company's website”, and “If my friends recommended their products, I would buy them” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). This scale was reliable both pre-transgression (α = 0.87) and post-transgression (α = 0.91).

Expectancy Violation

To measure expectancy violation, participants responded after the transgression to a 3-item measure adapted from Greitemeyer and Sagioglou (2018). The items were: “You expect this type of behavior from such an organization”, “This behavior matches the image you have of such an organization”, and “You find this behavior inconsistent with the image you have of such an organization” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The first two of these items were reversed such that high scores indicated greater expectancy violation (α = 0.84).

Demographics

At the end of the survey, participants were asked to report their age, their gender (1 = male, 2 = female, 3 = other), and the amount they had spent online shopping in the past year (1 = nothing, I do not buy online, 2 = $1—$99.99, 3 = $100—$999.99, 4 = $1000—$9999, 5 = more than $10,000).

Results and Discussion

Correlations among all variables—including the demographics—are summarized in Table 1. In the next section, we report the effects of our manipulation on trust and consumer intentions using 2 (Time) × 2 (Organization Type) mixed ANOVAs.Footnote 2

Trust

Unsurprisingly, trust was lower post-transgression (M = 2.14, SD = 1.04) than pre-transgression (M = 5.19, SD = 0.99), F(1,328) = 1521.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.82. There was also a significant main effect of Organization Type, F(1,328) = 35.24, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, but this was qualified by a significant Time × Organization Type interaction, F(1,328) = 27.59, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08 (see left-hand side of Fig. 2). Tests of simple main effects of Organization Type revealed that, pre-transgression, trust was higher when the organization was described as a nonprofit than when it was described as a commercial organization, F(1,328) = 73.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.18. Post-transgression, however, this effect of organization type disappeared, F(1,328) = 0.02, p = 0.88, ηp2 = 0.00. Another way of looking at this interaction is that the transgression caused a decrease in trust for both the commercial, F(1,328) = 576.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.64, and the nonprofit organization, F(1,328) = 967.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.75, but the effect size was significantly greater for the nonprofit. This pattern provides support for the moral disillusionment hypothesis H1a, but not the moral insurance hypothesis H2a.

Consumer Intentions

As for trust, consumer intentions were lower post-transgression (M = 2.88, SD = 1.41) than pre-transgression (M = 5.47, SD = 0.93), F(1,328) = 871.64, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.73, but this main effect was qualified by a significant interaction with Organization Type, F(1,328) = 4.58, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.01 (see right-hand side of Fig. 2). Consumer intentions were higher in the nonprofit than the commercial condition pre-transgression, F(1,328) = 13.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, an effect that disappeared after the transgression, F(1,328) = 0.00, p = 0.979, ηp2 = 0.00. As for trust, this reflected the fact that the transgression had a significant negative effect on consumer intentions for both the commercial, F(1,328) = 379.55, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.54, and the nonprofit organization, F(1,328) = 495.27, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.60, but the effect size was significantly greater for the latter. Again, this provides support for H1a but not for H2a.

In sum, these analyses provide preliminary support for the moral disillusionment hypothesis: the decrease in trust and consumer intentions pre- versus post-transgression was particularly strong for the nonprofit organization relative to the commercial organization that committed the same ethical transgression. In contrast, the findings speak against the moral insurance hypothesis: there was no evidence that the nonprofit was buffered from the negative effects of scandal by virtue of its initial trust advantage.

Testing the Moral Disillusionment Model of Organizational Transgressions

We next turned our attention to formally testing the moral disillusionment model of organizational transgressions. The predicted mechanism for the disillusionment hypothesis was that a transgression committed by a nonprofit violates expectations more than when the same transgression is committed by a commercial organization (H1b). In line with this, a between-groups ANOVA revealed that expectancy violation was greater in the nonprofit (M = 5.73, SD = 1.23) compared to the commercial condition (M = 4.89, SD = 1.41), F(1,328) = 32.65, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09.

To conduct the mediation analyses, Organization Type was coded such that commercial = 0 and nonprofit = 1. The criterion variables were calculated using difference scores. Specifically, the post-transgression scores were subtracted from the pre-transgression scores, such that the higher the score, the greater the drops in trust and consumer intentions post-transgression.Footnote 3

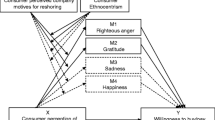

To test the model, we used Model 6 of Preacher and Hayes’ PROCESS macro, which tests for serial mediation (Hayes 2013). Analyses were conducted using 10,000 bootstrapped samples and 95% confidence intervals (CI). As can be seen in Fig. 3, expectancy violation mediated the different rate at which participants penalized the nonprofit and the commercial entity for the same transgression. Specifically, transgressions by the nonprofits violated expectations more than when the same transgressions were committed by a commercial organization, and it was through this effect that participants reported a greater drop in trust in the nonprofit organization. This in turn flowed through to greater decreases in consumer intentions. In sum, the data are consistent with the moral disillusionment model of organizational transgressions (H1b).

Study 2

Study 2 extends Study 1 in three ways. First, we sought to increase generalizability by using a different type of transgression: sexual exploitation of vulnerable women by employees. Second, we note that in Study 1 the nonprofit organization was only donating a portion of their profits to charitable causes. It is possible that this may have reduced the moral reputation of the nonprofit compared to if a full charity model was used, with potential implications for the likelihood of detecting moral disillusionment versus moral insurance effects. To avoid this ambiguity, in Study 2 we changed the stimulus material such that the nonprofit was described as donating all its profits to charitable causes. Third, we included two versions of the nonprofit condition: one in which the transgression directly violated their moral mission (i.e., the mission was to protect women), and one in which the transgression did not directly violate their moral mission (i.e., the mission was to protect the environment).

Based on Study 1, we expected support for the moral disillusionment hypothesis (H1a and 1b): that expectancy violation would be greater for the nonprofit than the commercial organizations, and that through this mechanism the decrease in trust will be greater for the nonprofit, which in turn will flow through to a greater decrease in supportive consumer intentions. As a secondary research question, we also examined the possibility that the expectancy violation will be stronger when the transgression is on a dimension that is relevant to the nonprofit’s mission. In other words, we tentatively hypothesized that the effects described in H1a will be more pronounced for the mission-relevant condition than for the mission-irrelevant condition.

Methods

Participants

Five hundred and fifty U.S. participants were recruited through Prolific, in exchange for $1US. Five respondents failed the attention check (“To ensure you are still reading this, please select ‘disagree’”) and were deleted from analyses. Another six participants were removed from analysis because they failed one of two manipulation checks (five pre-transgression; one post-transgression—see details below). This resulted in a usable sample of 539 participants (Mage = 37.07). The sample consisted of 303 males, 230 females, and 6 participants who identified as “other”.

Design

As in Study 1, we compared ratings of trust and consumer intentions immediately after the description of the organization type (pre-transgression) and immediately after the description of the transgression. Participants read that members of an organization had been involved in the sexual exploitation of women in developing countries. We also included a measure introduced for this study: consumer word of mouth intentions. In sum, the experiment used a 3 (Organization Type: Commercial vs. Nonprofit Environment vs. Nonprofit Women) × 2 (Time: pre- vs. post-transgression) mixed-groups design.

Procedure and Materials

Manipulation of Organization Type

In the Commercial condition, the text was similar to that used in the equivalent condition in Study 1. The two nonprofit conditions also used similar text to that used in Study 1, with the exception that the charity’s mission was manipulated: depending on condition, it was described as raising money for environmental causes or for women in need. Another difference between Study 1 and Study 2 is that the nonprofits were described as a full charity, with 100% of its profits going to its charitable causes.

Immediately after reading this information, participants were given a simple manipulation check: “What is the mission of GlobalDress?” Response options were: “to protect women”, “to protect the environment”, and “to become the #1 destination for fashion lovers”. Participants then completed measures of trust, consumer intentions, and word of mouth intentions. Next, participants completed a series of distractor questions (see details below) before being presented with the transgression.

Transgression

All participants were then presented with the following information describing an organizational transgression committed by GlobalDress.

The CEO of GlobalDress - along with several other company directors - have been found to have been purchasing sex services in multiple developing countries. Investigations showed that the CEO, the Chief Financial Officer, Director of Operations, and the Director of Community Affairs were purchasing services from sex workers while on business trips.

The investigation revealed that this occurred while the staff members were in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Rwanda. The investigation indicated that these individuals paid for sex at brothels, but they used personal funds, not company funds.

After reading this information, participants again completed the measures of trust, consumer intentions, word of mouth intentions, as well as a measure of expectancy violation. To ensure that information was internalized, participants were asked to respond to a simple True or False question post-transgression: “GlobalDress CEO and several company directors have been found to have purchased sex services in multiple developing countries”.

Dependent Measures

Trust was measured using the same scale used in Study 1. It again proved reliable at both time points (pre-transgression: α = 0.90; post-transgression: α = 0.92).

Consumer intentions were also measured using the same items used in Study 1, and proved reliable at both time points (pre-transgression: α = 0.88; post-transgression: α = 0.96).

Word of mouth intentions was measured by asking “How likely is it that you would recommend GlobalDress to a friend or colleague?” (0 = not at all likely, 10 = extremely likely). This item is based on the “net promoter index” popularized by Reichheld (2003).

Expectancy violation was measured using the same items used in Study 1 (α = 0.87). To reduce the possibility that the pre-transgression measures of trust were priming participants to view the transgression through a “trust lens”, we measured the demographics of age, gender, and past online shopping behavior after the information about organization type but before the introduction of the transgression information. We also included the following distractor questions: self-esteem (measured using the 16-item Rosenberg self-esteem scale), income (a 6-point scale anchored at 1 for “less than $20 000” and 6 for “more than $100 000”), and how much they had “donated to a charity in the past year” (a 5-point scale anchored at 1 for “none at all” and 5 for “over $1 000”).

Results

Trust

A 2 (Time) × 3 (Organization Type) ANOVA on trust revealed main effects of Time, F(1,536) = 848.44, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.61, and Organization Type, F(2,536) = 17.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, which were qualified by the predicted Time × Organization Type interaction, F(2,536) = 10.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, see Fig. 4. Simple main effects of Time showed that trust dropped significantly post-transgression across all three conditions. However, the effect size was stronger in the Nonprofit Women condition, F(1,536) = 380.69, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.42, than the Nonprofit Environment condition, F(1,536) = 306.49, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.36, which in turn was stronger than the Commercial condition, F(1,536) = 179.80, p < 0.001 ηp2 = 0.25. This pattern provides support for the moral disillusionment H1a but not for the moral insurance H2a.

Also informative was the analysis of the simple main effects of Organization Type across time. Consistent with Study 1, there was a significant effect of Organization Type at pre-transgression, F(2,536) = 42.11, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14, such that participants reported higher trust in the Nonprofit Environment and Nonprofit Women conditions compared to the Commercial condition (ps < 0.001). Post-transgression, however, the effect of Organization Type was only marginally significant, F(2,536) = 2.77, p = 0.064, ηp2 = 0.01. Trust was greater for the Nonprofit Environment condition compared to the Commercial condition (p = 0.040) and the Nonprofit Women condition (p = 0.045). The Commercial condition and the Nonprofit Women condition were equivalent (p = 0.967).

Consumer Intentions

As for trust, consumer intentions dropped considerably after the transgression (M = 3.65, SD = 1.63) compared to before the transgression (M = 5.34, SD = 1.00), F(1,536) = 540.97, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.50. There was also a main effect of Organization Type, F(2,536) = 4.19, p = 0.016, ηp2 = 0.02. Duncan’s posthoc tests revealed that consumer intentions overall were greater for the Nonprofit Environment condition (M = 4.68) compared to the Commercial condition (M = 4.39) and the Nonprofit Women condition (M = 4.42). However, the Time × Organization Type interaction was non-significant, F(2,536) = 1.93, p = 0.146, ηp2 = 0.01.

Word of Mouth Intentions

As for trust, analysis of the word of mouth scores revealed main effects of Time, F(1,536) = 606.95, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.53, and Organization Type, F(2,536) = 17.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, which were qualified by the predicted Time × Organization Type interaction, F(2,536) = 10.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, see Fig. 5. Decreases in word of mouth intentions were stronger in the Nonprofit Women condition, F(1,536) = 285.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.35, than the Nonprofit Environment condition, F(1,536) = 213.52, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.29, which in turn was stronger than the Commercial condition, F(1,536) = 125.26, p < 0.001 ηp2 = 0.19. This provides support for H1a but not for H2a.

When examining simple main effects of Organization Type across time, a significant effect of Organization Type emerged pre-transgression, F(2,536) = 22.56, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, such that participants reported higher word of mouth intentions in the Nonprofit Environment and Nonprofit Women conditions compared to the Commercial condition (ps < 0.001). Post-transgression, the effect of Organization Type was also significant, F(2,536) = 4.72, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.02, with a pattern of means that resembled that for trust. Specifically, word of mouth intentions were greater for the Nonprofit Environment condition compared to the Commercial condition (p = 0.008) and the Nonprofit Women condition (p = 0.008). The Commercial condition and the Nonprofit Women condition were equivalent (p = 0.987).

Testing the Moral Disillusionment Model of Organizational Transgressions

As for Study 1, the ANOVAs reveal no support for the moral insurance hypothesis (H2a), but preliminary support for the moral disillusionment hypothesis (H1a). Further supporting the moral disillusionment model, a three-level between-groups ANOVA revealed that expectancy violation was greater in the Nonprofit Women (M = 5.94, SD = 1.26) and the Nonprofit Environment condition (M = 5.81, SD = 1.26) compared to the Commercial condition (M = 5.20, SD = 1.43), F(2,536) = 16.36, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06. Although we expected that the expectancy violation might be stronger when the transgression was mission-relevant for the nonprofit organization, this trend was non-significant. As such, we turn our attention to testing the moral disillusionment hypothesis comparing the two nonprofit organizations with the commercial organization.

To do so, we again conducted serial mediation analyses using Model 6 of PROCESS. In this case, Organization Type was coded into two orthogonal contrasts. One contrast represented the difference between the two nonprofit conditions and the commercial organization (Nonprofit Children = 1, Nonprofit Women = 1, Commercial = -2), and this was treated as the key independent variable. The other contrast represented the difference between the two nonprofit conditions (Nonprofit children = -1, Nonprofit women = 1, Commercial = 0) and was added as a covariate in the design.

As can be seen in Fig. 6, expectancy violation mediated changes in participants’ trust decline post-transgression (versus pre-transgression), which in turn flowed through to changes in participants’ decline in word of mouth intentions post-transgression. This pattern is consistent with H1b.Footnote 4

Discussion

As in Study 1, the data were consistent with the moral disillusionment model. Specifically, transgressions by the nonprofits violated expectations more than when the same transgressions were committed by a commercial organization, and it was through this effect that participants reported greater drop in trust post-transgression for the nonprofits. This drop in trust then flowed through into a greater drop in participants’ supportive word of mouth intentions. Post-transgression, the advantage that the nonprofits initially held over the commercial organization was reduced when the transgression was mission-irrelevant, and eliminated altogether when the transgression was mission-relevant.

Although expectancy violation statistically explained much of the variance in how consumers responded to the nonprofit relative to the commercial organization, it could not explain the somewhat more negative reaction participants had to the nonprofit whose job it was to protect women compared to the nonprofit whose job it was to protect children. We can only speculate as to why differences emerged between the two nonprofit conditions on trust and consumer intentions when there was no significant difference in expectancy violation. One possibility is that participants were making a pragmatic decision to withdraw support from the nonprofit whose transgression was mission-relevant (in this case the Nonprofit Women condition). A nonprofit whose job it is to protect women from sexual exploitation would by definition have more contact with vulnerable women, and so may be at more risk of reoffending. It may also indicate a loss of confidence in the ability of a nonprofit to achieve its mission, given it was not able to prevent its own employees from engaging in mission-relevant transgressions. Thus, although participants may be no more shocked by the mission-relevant transgression than when the nonprofit’s transgression was mission-irrelevant, it may be that participants were especially motivated to withdraw support from the former organization.

Another issue to note—and one that sets the current study apart from Study 1—is that the predicted Organization Type × Time interaction emerged only on word of mouth intentions, not on consumer intentions. It is possible that this discrepancy emerged as a consequence of the changes in design from Study 1 to Study 2: specifically, the inclusion of a mission-relevance manipulation, and the transition from describing the nonprofit as a full charity as compared to a social entrepreneurship model in which a portion of profits were donated to charity. Before discussing this further, we first report Study 3, which also measured both consumer intentions and word of mouth intentions.

Study 3

Study 3 expanded on Studies 1 and 2 in two ways. First, we sought to further increase generalizability by using a new transgression: use of unethical labor practices. Second, we incorporated two exploratory moderators into the design. One of these is the reputation of the organization as capable. In the reputation literature, Brown and Dacin (1997) introduced the notion that there are two types of contextual cues for reputation: those relating to ability, and those related to CSR. Our theorizing regarding the effects of organization type on responses to scandal is based on moral reputation—an organization’s reputation as virtuous—which aligns with the CSR dimension. However, it remains to be seen whether these effects would interact with—or even be trumped by—an organization’s reputation for excellence in service, innovation, and product quality. Note that we examined this moderator as an exploratory research question rather than with an a priori prediction in mind. The logic of our hypotheses implies a matching effect—such that a moral reputation would influence responses to a moral transgression—rather than a cross-over effect in which reputation on a competence dimension would influence responses to transgressions committed on a moral dimension. However, we tested this question in the spirit of due diligence, and with a view to aligning the current program of research more closely with the broader literature on corporate reputation.

The other moderator that we tested was whether the transgression was committed by one or many members of the organization. It is likely that community responses to scandal would be less punitive if the transgression was committed by a “bad apple” within the organization than if the organization as a whole were implicated (a “bad barrel” situation). What is more relevant to the current research question is whether this would also moderate whether nonprofits are penalized more harshly than commercial organizations for the same transgression. In their examination of (competence-related) organizational transgressions, Coombs and Holladay (2006) argue that reputational halo effects can emerge for two reasons: (1) because a positive reputation operates as a “shield” from subsequent bad news, and (2) because a positive reputation leads consumers to offer the benefit of the doubt when the culpability of the organization as a whole is ambiguous. The bad apple vs. bad barrel manipulation in Study 3 was conducted with this in mind. In Studies 1 and 2, the transgressions were committed by a range of central figures in the organization, the implication of which is that the organization as a whole was culpable. This situation resembles the bad barrel condition in Study 3. The inclusion of a bad apple condition offers an exploratory test of the “benefit of the doubt” reasoning. If respondents are engaging in benefit of the doubt reasoning, it is plausible that the disillusionment effects reported in Studies 1 and 2 would be less pronounced in the bad apple condition than in the bad barrel condition.

Methods

Participants

Five hundred and twenty-three U.S. participants were recruited through Prolific, in exchange for $1.25US. Eleven respondents failed an attention check and an additional nine were removed from analysis as a result of failing one of three manipulation checks. This resulted in a usable sample of 503 participants (Mage = 33.14). The sample consisted of 269 females, 224 males, and 10 participants who identified as “other”.

Design

In Study 3, participants read that members of an organization had been sourcing products from a factory that had engaged in unethical labor practices. Adapting the same paradigm as in Study 2, participants were further led to believe that the organization responsible for the transgression was either a commercial organization or a nonprofit organization. In addition, we manipulated whether the organization had a strong versus a neutral reputation for competence, and we manipulated whether the transgression was conducted by a single individual within the organization (a “bad apple” situation) or whether the whole board of directors was complicit in the transgression (a “bad barrel” situation).

We compared ratings of trust, consumer intentions, and word of mouth intentions immediately after the description of the organization type and immediately after the description of the transgression. As such, the experiment used a 2 (Organization Type: commercial vs. nonprofit) × 2 (Reputation for competence: strong vs. neutral) × 2 (Responsibility: bad apple vs. bad barrel) × 2 (Time: pre-transgression vs. post-transgression) mixed-groups design. To undertake the mediation analysis, expectancy violation was measured post-transgression.

Procedure and Materials

Manipulation of Organization Type

Organization type was manipulated using similar text to that used in Study 2, with the exception that the nonprofit’s mission was described as “to raise money for people in need”. Immediately after reading this information, participants were given a simple manipulation check: “What is the mission of GlobalDress?” (options: “to protect people in need”, “to protect the environment”, and “to become the #1 destination for fashion lovers”).

Manipulation of Reputation for Competence

Previous research that has manipulated reputation have often done so by highlighting the organization’s outstanding performance, awards, and/or rankings (e.g., Grunwald and Hempelmann 2010; Sohn and Lariscy 2015). Consistent with this, immediately after the organization type information, participants were led to believe that the organization either had a strong reputation (“GlobalDress has a strong and long-standing reputation among consumers, with high ratings on numerous consumer websites. It has won multiple awards from the International Entrepreneurship Society for its innovative design and its reputation for excellence in service delivery”) or we were silent about its reputation (“GlobalDress is listed on numerous consumer websites. It is also a member of the International Entrepreneurship Society”). Immediately after this manipulation, participants were asked “Based on the information above, how would you rate the reputation of GlobalDress?” (1 = average reputation, 7 = excellent reputation). This was treated as a manipulation check.

Transgression

All participants were then presented with the following information describing an organizational transgression committed by GlobalDress.

Last week, an investigative journalism television program aired an episode which demonstrated that GlobalDress are using a manufacturing supplier in Bangladesh called ‘Desh Fashions’ to make some if its clothing.

The television program interviewed factory workers who reported working long hours, very small pay, and abuse if deadlines aren't met. In some of the worst cases there was even violence and threats of jail towards workers. Twelve year old children were also found to be working in the factory. Many of the workers are from rural areas and driven to work in the factory by poverty.

Manipulation of Responsibility

In the bad apple condition, participants were then told:

The documentary showed that only one person within GlobalDress was aware of the poor conditions—the site manager—and this person had not passed on those concerns to anyone else within GlobalDress. It appeared that the issue had been kept secret from the board of GlobalDress, which is why no action had been taken.

In the bad barrel condition, participants were told:

The documentary showed that the poor conditions were well known by the board. It appeared that the issue was an “open secret” within the board of GlobalDress but no action had been taken.

To ensure that the transgression information was internalized, participants were asked two questions: “What has GlobalDress been accused of?” (options: “Mistreating factory workers and employing children” and “polluting the surrounding environment”) and “Who knew about the transgression?” (options: “only the site manager” and “the entire GlobalDress board of directors”).

Measures

Immediately after the manipulation of Organization Type and Reputation, participants completed the same measures of trust (α = 0.88), consumer intentions (α = 0.89), and word of mouth intentions that were used in Study 2, with the exception that consumer intentions were measured on an 11-point scale rather than a 7-point scale. Post-transgression measures of trust (α = 0.89), consumer intentions (α = 0.95), and word of mouth intentions were collected immediately after the Responsibility manipulation, as well as the same expectancy violation that was used in previous studies (α = 0.88). As in Study 2, we included demographics and distractor questions between the organization type information and the transgression information.

Results and Discussion

Checking the Manipulation of Reputation

A 2 (Organization Type: commercial vs. nonprofit) × 2 (Reputation for competence: strong vs. neutral) × 2 (Responsibility: bad apple vs. bad barrel) ANOVA on the reputation manipulation check revealed the expected main effect of Reputation, F(1,495) = 42.84, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08. Consistent with the manipulation, participants reported the reputation of the organization in the strong reputation condition (M = 6.21, SD = 1.11) to be higher than that in the neutral reputation condition (M = 5.57, SD = 1.30). There were no main or interaction effects with responsibility (all ps > 0.187). However, there was a significant Reputation × Organization Type interaction, F(1,495) = 19.15, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04. Tests of simple main effects revealed that the main effect of Reputation reported above was sizable in the Commercial Organization condition, F(1,495) = 59.03, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.11, but was non-significant in the nonprofit condition, F(1,495) = 2.38, p = 0.124, ηp2 = 0.01. Inspection of means suggests ceiling effects in the nonprofit condition (strong reputation: M = 6.47; average reputation: M = 6.26), implying that the organization’s charity status communicated a strong reputation in participants’ minds, even in the absence of specific information that spoke to reputation.

Trust

A 2 (Organization Type: commercial vs. nonprofit) × 2 (Reputation for competence: strong vs. neutral) × 2 (Responsibility: bad apple vs. bad barrel) × 2 (Time) ANOVA on trust revealed main effects of Time, F(1,495) = 2451.39, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.83, and Organization Type, F(1,495) = 83.46, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14. However, these main effects were qualified by the predicted Time × Organization Type interaction, F(1,495) = 30.81, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, see Fig. 7.

Consistent with H1a, simple main effects of Time showed that the decline in trust post-transgression was more pronounced in the nonprofit condition, F(1,495) = 1531.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.76, than the commercial condition, F(1,495) = 956.59, p < 0.001 ηp2 = 0.66. Analyzing the simple effects the other way, there was a strong tendency for participants to trust the nonprofit organization (M = 6.01, SD = 0.77) more than the commercial organization pre-transgression (M = 5.06, SD = 0.99), F(1,495) = 151.69, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.24. Post-transgression, however, this effect had diminished considerably, although there was still a reliable tendency for participants to trust the nonprofit (M = 2.64, SD = 1.34) more than the commercial organization (M = 2.36, SD = 1.24), F(1,495) = 6.78, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.01.

There was also a main effect of reputation, F(1,495) = 18.96, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, signaling that participants trusted the organization with the strong reputation (M = 4.17) more than that with the neutral reputation (M = 3.89). However, Reputation did not feature in any significant 2-, 3-, or 4-way interactions with Time, Organization Type, or Responsibility (all ps > 0.079).

Finally, a main effect of responsibility, F(1,495) = 86.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.15, was qualified by a Responsibility × Time interaction, F(1,495) = 88.27, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.15. As might be expected, the decline in trust post-transgression was more pronounced in the bad barrel condition, F(1,495) = 1744.99, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78, than the bad apple condition, F(1,495) = 800.08, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.62. There was also a between-groups interaction between Responsibility and Organization Type, F(1,495) = 4.17, p = 0.042, ηp2 = 0.01, such that the tendency for people to trust the nonprofit more than the commercial organization was more pronounced in the bad apple condition, F(1,495) = 62.12, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.11, than the bad barrel condition, F(1,495) = 25.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05. Of more relevance to the current paper, however, this interaction was not moderated by Time (p = 0.567).

Consumer Intentions

Consumer intentions dropped dramatically after the transgression (M = 4.20, SD = 2.76) compared to before the transgression (M = 8.88, SD = 1.63), F(1,495) = 1395.26, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.74. As in Study 2, however, this effect was statistically equivalent regardless of whether the transgressor was a nonprofit or commercial organization [Organization Type × Time: F(1,495) = 0.97, p = 0.325, ηp2 = 0.00].

As for trust, participants expressed stronger consumer intentions for the organization with the strong reputation (M = 6.72) compared to that with the neutral reputation (M = 6.36), F(1,495) = 5.91, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.01. However, Reputation did not feature in any significant 2-, 3-, or 4-way interactions with Time, Organization Type, or Responsibility (all ps > 0.310).

Finally, a main effect of Responsibility, F(1,495) = 42.87, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, was qualified by a Responsibility × Time interaction, F(1,495) = 45.07, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08. Again, this simply reflected the fact that the decline in consumer intentions post-transgression was more pronounced in the bad barrel condition, F(1,495) = 976.51, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.66, than the bad apple condition, F(1,495) = 466.74, p < 0.001 ηp2 = 0.49. Of more relevance to the current paper, however, Responsibility did not feature in any significant 2-, 3-, or 4-way interactions with Organization Type (all ps > 0.310).

Word of Mouth Intentions

Main effects of Time, F(1,495) = 1305.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.73, and Organization Type, F(1,495) = 43.92, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, were qualified by the predicted Time × Organization Type interaction, F(1,495) = 15.63, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03, see Fig. 7. Consistent with H1a, simple main effects of Time showed that the decrease in word of mouth intentions post-transgression was particularly strong in the Nonprofit condition, F(1,495) = 811.75, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.62, than the Commercial condition, F(1,495) = 512.62, p < 0.001 ηp2 = 0.51. Another way of expressing the interaction is that the tendency for people to have stronger word of mouth intentions for the Nonprofit condition than the Commercial condition was greater pre-transgression, F(1,495) = 52.11, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, than post-transgression, F(1,495) = 9.27, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02.

As for the other measures, participants expressed stronger word of mouth intentions for the organization with the strong reputation (M = 5.46) compared to that with the neutral reputation (M = 4.75), F(1,495) = 5.91, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.01. However, Reputation did not feature in any significant 2-, 3-, or 4-way interactions with Time, Organization Type, or Responsibility (all ps > 0.068).

Testing the Moral Disillusionment Model of Organizational Transgressions

A three-level between-groups ANOVA on expectancy violation revealed only a main effect of Organization Type, F(1,495) = 119.58, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.20, such that expectancy violation was greater in the Nonprofit (M = 5.78, SD = 1.28) than the Commercial condition (M = 4.31, SD = 1.70). No other main or interaction effects emerged (all ps > 0.119).

To conduct the mediation analyses, we again used Model 6 through PROCESS (Organization Type was coded such that commercial = 0 and nonprofit = 1). As can be seen in Fig. 8, transgressions by the nonprofits violated expectations more than when the same transgressions were committed by a commercial organization, and it was through this effect that participants reported a greater drop in trust after a transgression for the nonprofits, which in turn flowed through to drops in word of mouth intentions. This effect is consistent with the moral disillusionment effect described in H1b.Footnote 5

General Discussion

The novel paradigm used in the current studies allowed us to compare the downstream consequences of the same trust breach for organizations that were run for charitable versus commercial purposes. This allowed us to test whether nonprofits are held to a different ethical standard than commercial organizations in terms of the consequences of trust breaches (and if so, why). We tested two competing hypotheses. The moral insurance hypothesis proposed that nonprofits would be penalized less harshly for transgressions, because their past moral deeds serve as an insurance policy. In contrast, the moral disillusionment hypothesis proposed that nonprofits would be penalized more harshly for transgressions because they violate expectations regarding how nonprofits should behave.

The studies showed that, prior to hearing about a transgression, nonprofits benefit from their reputations as moral: not only did consumers trust the nonprofits more than the commercial organizations, they also reported stronger intentions to engage with products from the nonprofits (Study 1) and to spread positive word of mouth about them (Studies 2 and 3). However, after hearing a nonprofit was guilty of financial corruption (Study 1), sexual exploitation of women (Study 2), or unethical labor practices (Study 3), participants reported more surprise than when the same transgressions were committed by a commercial organization. Consistent with EVT, this led to a more dramatic drop in trust when the transgression was committed by a nonprofit and, in turn, a steeper decline in consumer intentions. In short, the data supported the moral disillusionment hypothesis, but not the moral insurance hypothesis. Further, moral disillusionment was more pronounced when the transgression overlapped with the domain of the nonprofit’s mission (Study 2). However, the moral disillusionment effect was not moderated by either the nonprofit’s reputation for organizational competence, or whether the transgression was committed by an individual employee versus the entire leadership team (Study 3).

At first glance, the current findings appear contrary to past research on the insurance-like effects of CSR programs (see Flammer 2013; Godfrey et al. 2009; Janney and Grove 2011; Williams and Barrett 2000). In other words, although profit-oriented organizations may gain trust benefits from doing good deeds, our data show that mission-oriented organizations risk greater trust damage (after a transgression) because of their moral reputations. It is possible that the same mechanism that propels the moral disillusionment effect in nonprofits also underpins the insurance-like qualities of CSR in commercial organizations. When the organization is profit-oriented, apparently “selfless” work may violate expectations, leading to a greater weighting of this information than if the same good deeds were done by a nonprofit. These unexpected good deeds therefore lift commercial organizations to higher levels of trust, which can be used as insurance against future misdeeds—with a comparable fall from grace still leaving the commercial organization ahead of non-socially responsible competitors. This idea—that expectancy violation can generate a “trust bank” for commercial organizations in the same way that violated expectations can damage trust for nonprofits—remains to be tested in future research.

In Studies 2 and 3, the moral disillusionment effect emerged on word of mouth intentions, but not on consumer intentions. This is surprising, given that the effect on consumer intentions did emerge in Study 1. Interestingly, this anomaly seems to be partly attributable to the fact that in Study 1—but not in Studies 2 and 3—participants had a stronger intention to engage with the products from the nonprofit than the commercial organization pre-transgression. Why this consumer advantage did not emerge in Studies 2 and 3 may be attributable to the fact that the organization in Study 1 was a social enterprise that employed a “one-for-one” business model with product sales tied directly to in-kind donations (i.e., every piece of clothing bought would be donated). In comparison, in Studies 2 and 3 the organization was a pure nonprofit with all profits invested in charity projects. It may be that consumers are more motivated to support mission-based organizations when their contributions are tangible (i.e., when they know exactly what the contribution will be used for). Alternatively, it may be that business models that tie charitable support directly to consumer actions (i.e., cause-related marketing approaches; Varadarajan and Menon 1988) are more mobilizing for consumers than stricter charity models. These ideas remain to be tested. For now, we merely conclude that the evidence for the moral disillusionment effect was always consistent for trust, and more consistent on word of mouth intentions than on people’s intentions to engage with the organization’s products.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

A strength of the current study is its controlled, experimental approach, which allowed us to make like-for-like comparisons of the same organization, varying only whether the organization was run for charitable purposes or for profit. This level of control helps us make solid claims about causality and mechanism. However, the experimental approach comes with the usual limitations surrounding generalizability and external validity.

We aimed to minimize these concerns in the design phase. First, participants responded to what they believed was a real transgression in a real organization; they were not asked to reflect on an imagined scenario or a hypothetical situation. Doing this enabled us to create as real a psychological environment as possible, akin to the public reading about a transgression in the media. Second, we varied the transgression across the studies to encompass acts of fraud, exploitation of women, and unethical labor practices. However, care is required when generalizing beyond these types of transgressions: for example, we focused only on integrity transgressions. Future research could benefit from incorporating all three trustworthiness dimensions: integrity, benevolence, and competence (Mayer et al. 1995; see also Xie and Peng 2009). We also argue, however, that there is not necessarily a firewall separating these three categories of transgression in the community’s mind. In the nonprofit space in particular, it is possible that certain forms of incompetence are interpreted in people’s minds as a breach of integrity (i.e., part of the moral mission of the organization is to show competence in how they protect and support their constituents). Future research could investigate this tendency empirically.

We also acknowledge that we only have measures of self-reported consumer intentions. Although intentions are predictive of behaviors (Kraus 1995), it remains an empirical question the extent to which the sentiments and intentions reported here would translate into actual purchasing and word of mouth behaviors.

Finally, we accept that there may be conditions where the moral disillusionment effects may not emerge, or may even be reversed as per the moral insurance hypothesis. In the current studies we examined three potential moderators: the mission-relevance of the transgression (Study 2), the pre-existing reputation of the organization for competence (Study 3), and the extent to which the transgression implicated one or many people within the leadership team of the organization (Study 3). In none of these conditions did we find that the moral disillusionment effect was eliminated or reversed. But we do not rule out the possibility that future investigation of moderators will uncover such conditions. Rather than adjudicating in favor of moral disillusionment, we hope that the current studies will operate as a foundation on which future research will build and elaborate the conditions under which moral disillusionment effects emerge, and the conditions under which moral insurance effects might emerge.

Managerial Implications

Despite the limitations raised above, our findings have clear implications for management. First, our findings confirm that nonprofits benefit from having moral reputations: our pre-transgression data across three studies provide a useful empirical estimate of the extent to which they can trade on that goodwill, compared to commercial organizations. Second, our results powerfully demonstrate that nonprofits have more to lose from a trust breach than do commercial organizations: their fall from grace is steeper, resulting in an elimination of their trust advantage (and in some cases a reversal of it). Thirdly, our moderation results show that this is particularly the case when the transgression directly breaches the nonprofit’s mission. It is therefore especially important for nonprofit boards and managers to have in place a comprehensive range of governance, internal controls, and cultural mechanisms to prevent breaches occurring, with a particular focus on identifying and managing vulnerabilities directly related to the core mission of the nonprofit. This finding also implies that more effort and resources will be required to repair trust following a mission-relevant transgression.

Our findings further highlight the importance of nonprofits responding swiftly and comprehensively to trust breaches, to limit the damage to trust and consumer intentions, and restore trust as quickly and robustly as possible (Gillespie and Dietz 2009). The fact that breaches take a greater toll on trust in nonprofits suggests that nonprofits may need to augment and amplify their trust repair efforts in a way that is not required by commercial organizations. Robust trust repair will require gaining an accurate shared understanding of what caused the breach—so that the internal problems can be fixed and future violations prevented—as well as offering credible apologies and compensation where appropriate (Bachmann et al. 2015; Gillespie et al. 2014).

Our study helps nonprofit managers understand that a strong ‘trust bank’ of good deeds is not sufficient to protect their organization from a loss of trust after a violation. Rather, our findings indicate that the sharp breakdown of trust occurs because the transgression violates stakeholders’ expectations that nonprofits will act morally, leaving them disillusioned. An implication is that trust prevention and repair requires nonprofits to carefully manage the expectations stakeholders have of them, and to ensure they can reliably live up to and deliver against these expectations. This may require nonprofits confronting an inherent tension in their industry: the expectation that a high proportion of income and donations be channeled into achieving the charitable mission, leaving minimal resources to ensure robust internal governance and oversight. Nonprofits may need to shift stakeholders’ expectations of how donations are used, enabling sufficient resources to ensure appropriate systems, processes, structures, and cultures are in place to prevent transgressions, and to quickly detect and manage problems before they escalate into trust failures.

Notes

A fifth item from the original scale—“This company keeps promises”—was not seen to be a good fit for the current context and so was not included in the current studies.

The results of these analyses do not change when controlling for age, sex, and online spending. In Studies 2 and 3, we also measured these demographic variables, and again the effects of organization type remained the same regardless of whether or not we controlled for these variables. Consequently, all the analyses reported in this manuscript were conducted without controlling for demographics.

Although it is sometimes assumed that difference scores are a sub-optimal way of capturing change scores for regressions, the premise for this rule of thumb is that it is important to control for regression toward the mean, and associated spurious negative correlations. However, it has been established that for a simple experimental design such as the one used here, the most appropriate approach is usually to take the difference between pre- and post-transgression scores, and to treat that as the criterion variable (as elaborated by Allison 1990, the conventional approach of predicting post-transgression scores while controlling for pre-transgression scores “leads to inferences that are intuitively false”, p. 93).

It should be noted that the model was also significant when word of mouth intentions was replaced with consumer intentions, b = 0.11, SE = 0.02, 95%CI[0.065, 0.151]. This model should be interpreted with caution, however: although the indirect pathway is significant, lending support for the moral disillusionment model, it is important to remember that the direct effect of Organizational Type on the decline in consumer intentions pre- versus post-transgression was non-significant.

As for Study 2, the model was also significant when word of mouth intentions was replaced with consumer intentions, b = 0.75, SE = 0.11, 95% CI [0.539, − 0.988]. Interpretation of this model carries the same caveats as described in Footnote 4, given that the direct effect of Organizational Type on the decline in consumer intentions pre- versus post-transgression was non-significant.

References

Aaker, J., Vohs, K. D., & Mogilner, C. (2010). Nonprofits are seen as warm, and for-profits as competent: Firm stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 224–237.

Ahluwalia, R., Burnkrant, R., & Unnava, H. (2000). Consumer response to negative publicity: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 203. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.37.2.203.18734.

Allison, P. D. (1990). Change scores as dependent variables in regression analysis. Sociological Methodology, 20, 93–114.

Ariyanto, A., Hornsey, M. J., & Gallois, C. (2009). Intergroup attribution bias in the context of extreme intergroup conflict. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12, 293–299.

Bachmann, R., Gillespie, N., & Priem, R. (2015). Repairing Trust in Organizations and Institutions: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Organization Studies, 36(9), 1123–1142.

Barlow, F. K., Thai, M., Wohl, M. J. A., White, S., Wright, M.-A., & Hornsey, M. J. (2015). Perpetrator groups can enhance their moral self-image by accepting their own intergroup apologies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 60, 39–50.

Barnett, M. L., Hartmann, J., & Salomon, R. M. (2018). Have you been served? Extending the Relationship between corporate social responsibility and lawsuits. Academy of Management Discoveries, 4(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2015.0030.

Bhattacharjee, A., Dana, J., & Baron, J. (2017). Anti-profit beliefs: How people neglect the societal benefits of profit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(5), 671–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000093.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61, 68–84.

Burgoon, J., & Le Poire, B. (1993). Effects of communication expectancies, actual communication, and expectancy disconfirmation on evaluations of communicators and their communication behavior. Human Communication Research, 20(1), 67–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1993.tb00316.x.

Burt, C. D. (2012). The importance of trust to the funding of humanitarian work. In S. C. Carr, M. MacLachlan, & A. Furnham (Eds.), Humanitarian work psychology (pp. 317–358). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cai, Y., Jo, H., & Pan, C. (2012). Doing well while doing bad? CSR in controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(4), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1103-7.

Chandler, D., Polidoro, F., & Yang, W. (in press). When is it good to be bad? Contrasting effects of multiple reputations for bad behavior on media coverage of serious organizational errors. Academy of Management Journal.

Chernev, A., & Blair, S. (2015). Doing well by doing good: The benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1412–1425. https://doi.org/10.1086/680089.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2006). Unpacking the halo effect: Reputation and crisis management. Journal of Communication Management, 10, 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540610664698.

Dawar, N., & Pillutla, M. M. (2000). Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.37.2.215.18729.

Decker, W. H. (2012). A firm's image following alleged wrongdoing: Effects of the firm's prior reputation and response to the allegation. Corporate Reputation Review, 15(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2011.27.

DiGangi, C. (2016, January 14). 7 scandals from the not-for-profit world. Retrieved from https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/companies/7-scandals-from-the-nonprofit-world/ss-BBobXNE#image=5. Accessed Jan 2019.

Flammer, C. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 758–781. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0744.

Folkes, V. S., & Kamins, M. A. (1999). Effects of information about firms’ ethical and unethical actions on consumers’ attitudes. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 8, 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp0803_03.

Gibelman, M., & Gelman, S. (2004). A loss of credibility: Patterns of wrongdoing among nongovernmental organizations. Voluntas International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 15(4), 355–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-004-1237-7.

Gillespie, N., Dietz, G., & Lockey, S. (2014). Organizational reintegration and trust repair after an integrity violation: A case study. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(3), 371–410.

Gillespie, N., & Dietz, G. (2009). Trust repair after an organization-level failure. Academy of Management Review, 34(1), 127–145.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.750.

Greitemeyer, T., & Sagioglou, C. (2018). When positive ends tarnish the means: The morality of nonprofit more than of for-profit organizations is tainted by the use of compliance techniques. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 67–75.

Grunwald, G., & Hempelmann, B. (2010). Impacts of reputation for quality on perceptions of company responsibility and product-related dangers in times of product-recall and public complaints crises: Results from an empirical investigation. Corporate Reputation Review, 13(4), 264–283.

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Holtfreter, K. (2008). Determinants of fraud losses in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 19(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.204.

Independent Sector. (2018). The Charitable Sector. Retrieved from https://independentsector.org/about/the-charitable-sector/. Accessed Jan 2019.

Islam, G. (2019). Psychology and business ethics: A multi-level research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, online first.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04107-w.

Iyer, A., Jetten, J., & Haslam, S. A. (2012). Sugaring o’er the devil: Moral superiority and group identification help individuals downplay the implications of ingroup rule-breaking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 141–149.

Janney, J. J., & Gove, S. (2011). Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: Reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. Journal of Management Studies, 48(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00984.x.

Johnson, D. I. (2012). Swearing by peers in the work setting: Expectancy violation valence, perceptions of message, and perceptions of speaker. Communication Studies, 63(2), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2011.638411.

Jones, G. H., Jones, B. H., & Little, P. (2000). Reputation as reservoir: Buffering against loss in times of economic crisis. Corporate Reputation Review, 3(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540096.