Abstract

Recently ethical implications of human resource management have intensified the focus on care perspectives in management and organization studies. Appeals have also been made for the concept of organizational care to be grounded in philosophies of care rather than business theories. Care perspectives see individuals, especially women, as primarily relational and view work as a means by which people can increase in self-esteem, self-develop and be fulfilled. The ethic of care has received attention in feminist ethics and is often socially construed as a feminine ethic. Although well developed in the caring professions there remains no model or definition of the care ethic in management literature with little care research undertaken. This paper develops the concept of the care ethic using Heidegger’s philosophy, namely, care is fundamental to human being. To show Heideggerian care, an individual notices, pays attention to another and responds in ways to empower and enable. In a study which aimed to analyze women’s lived experience of career, we applied the philosophically grounded methodology hermeneutic phenomenology. Findings revealed the power of Heideggerian care, Sorge, as a key factor in creating meaning. From this, we propose that care has potential as a theoretical and philosophically based construct with strong practical implications. It provides a way of understanding the care ethic, lies at the heart of our being, and is essential to meaning in our grelationships and undertakings. Crucially, it can provide reprieve from the existential angst that trademarks our being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years global concerns around the ethics of human resource management have intensified the focus on care perspectives in management and organization studies (Delios 2010; Dutton et al. 2006; Islam 2013; McAllister and Bigley 2002; Tronto 1993, 2010). Care perspectives see individuals, especially women, as primarily relational (Gilligan 1982) and view work as a means by which people can increase self-esteem, self-develop and be fulfilled (Islam 2013; McAllister and Bigley 2002). Such perspectives stand in contrast to a “human capital” view on employees (Foss 2008; Ployhart and Moliterno 2011).

Although the care construct has been well established in the context of the caring professions (e.g., Boykin and Schoenhofer 2001; Skovholt 2005), it has only recently received emphasis in the organizational and management literature (Rynes et al. 2012). There are appeals for organizational care to be grounded in philosophies of care rather than business theories alone (Kroth and Keeler 2009; Tomkins and Simpson 2015). Further, some writers have expressly linked the care ethic with Heideggerian care and proposed philosophical approaches that draw on existentialism and phenomenology to better understand the care ethic (Reich 2014; Tomkins and Simpson 2015). Empirical studies are essential for theory development and the care ethic is no exception. Yet empirical research on the ethic of care remains limited. We seek to address this gap. Further, we note with others the lack of philosophically informed discussions of the care ethic in organizations (Kroth and Keeler 2009; Tomkins and Simpson 2015) and the need to study care in everyday experiences (Lawrence and Maitlis 2012).

Additionally, feminist philosophies have criticized the care ethic, reasoning that it limits choices for women. It was Gilligan’s aim, through her comprehensive work on a women’s ethic of care, to value and celebrate the feminine as central to moral theory development for women (1982). Critics of an ethic of care suggest that a feminine ethic is often combined with feminist ethics and reinforces a pervasive biological view of women and motherhood; care should not be conflated with the gendered nature of the ‘carers’ (Tronto 2010). If ‘caring’ limits an individual’s autonomy and agency then it warrants further criticism from a feminist perspective (Clement 2018). Theoretical discussion and empirics confirm that a benefit of a universal ethic of care reinforces the value of a care ethic for dominant groups, women, and minorities (Held 2006); recognizing all as relational interdependent beings.

In response, we propose a philosophically inspired analysis of an ethic of care in organizations focused on women’s experiences drawing on Heidegger’s philosophy of care. In contrast to an essentialized view care with traits of compassion, empathy and kindness, Heidegger’s philosophy of care requires self-control, attention to another, and a deliberate response that empowers and enables. Rather than kindness and niceness, it has been more aligned with agency and self-organization (Tomkins and Simpson 2015). We suggest viewing the care ethic through Heideggerian philosophy can provide a more nuanced understanding of the care ethic.

Our phenomenological study focused on women’s experiences, specifically the meanings of their career. Phenomenology, the study of lived experience, is underpinned by philosophical concepts such as the positive impact of an ethic of care. As a methodology, it provides a way to determine what it means for an individual to experience a phenomenon through a subjective view. Heidegger saw care as fundamental to human being. His philosophy of care is based on the enactment of care in positive ways that nurture and care for others and the world (1927/2011).

Phenomenology questions how the meaning of an experience arises; phenomenological meaning emerges through the subjective view of lived experience. Our study sought to answer the question: “How does Heideggerian care provide a way to understand the meaning women make of their career?” Our empirical findings revealed the empowering function of an ethic of care to create meaning and aid individuals to gain autonomy and career agency. These “meaning structures” within women’s career narratives analyzed through the Heideggerian concept of care add to our theoretical understandings of the care ethic (van Manen 2016, p. 38).

Our paper is organized as follows. We review three strands of scholarly discussion relevant to our study of the ethic of care: recent developments in organization care; the historical evolution of the care construct to contemporary constructs of care; and Heidegger’s philosophy of care. We then examine Heideggerian care reflected against these literatures. We introduce the methodology of hermeneutic phenomenology and outline the processes used to conduct the interpretive research study. Heideggerian care in action is illustrated by examples of women’s experience of care using excerpts from a phenomenological analysis; anecdotes crafted from interview transcripts.

The Role of an Ethic of Care in the Organization

Three streams of scholarship provide a context for our examination of Heideggerian care. Positioned within a relational care ethic (first developed by Gilligan 1982), Tronto (1993, 2010) considers care within organizations arguing for care as social practice rather than disposition, a deliberate activity which shows concern for and is tailored to the individual. She emphasizes a feminist care ethic that values and legitimizes shared power, rather than restricts power to existing dominant cohorts. Tronto argues for a care ethic including the “values traditionally associated with women” (p. 3) yet, she urges a shift from a separate women’s morality.

Exploring an ethic of care in organizations and in work teams, Lawrence and Maitlis (2012) argue that despite an emphasis on close, long-term relationships in the ethic of care literature, this scholarship has centered more on theory than action. Compassion and care are positioned as the triggered response to others’ suffering or pain for either employees or organizations. They suggest research attention needs to be directed to ordinary, everyday discursive practices within longstanding work relationships. They link an ethic of care to an “ontology of possibility” and contend that care within organizations may have significant effects for both individuals and groups (p. 653).

Islam (2013) situates his work within organization studies and draws from Honneth’s (1995) recognition theory. Recognition can be “pre-cognitive” as it comes before worldviews, crosses cultural boundaries and satisfies the human need for affirmation (Honneth and Margelit 2001). Recognition differs from sympathy or “support for a cause” (Islam 2013, p. 242), having more in common with ‘solidarity.’ Therefore, Islam argues recognition supports the care perspective in management. Further, he contrasts recognition with social relationships within workplaces. While recognition is reified by human resource policies and work processes it is partial, directed towards work goals rather than relationships, compromising worker dignity. In contrast, a caring organization is ideally a workplace for becoming, where workers can recognize their potential through work (Islam 2013).

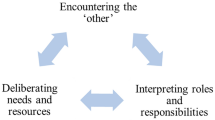

Although these perspectives on the ethic of care have different emphases: care as social practice (Tronto 1993, 2010); care in relationships through discursive practice (Lawrence and Maitlis 2012); and care as recognition which promotes flourishing (Islam 2013); they do share a common thread. They view care as a deliberate activity which involves paying attention to an individual’s needs. Further, they connect with several themes in contemporary organization studies: humane relationships (Hodson and Roscigno 2004); work as enrichment and existential engagement (Honneth 1995; McAllister and Bigley 2002; Sayer 2007); ethics (Gabriel and Casemore 2009); and career meaningfulness (Lips-Wiersma 2002). Various theoretical opportunities have also been expressed, for example, Tomkins and Simpson (2015) encourage philosophical approaches that draw on existentialism and phenomenology; an approach focused on “the grounded, the mundane, and the experiential” (p. 1015). In addition, Kroth and Keeler (2009) appeal for progress on the concept of organizational care grounded on philosophies of care. Our work adds to these perspectives of care as relational and as recognition (Tronto 1993, 2010; Lawrence and Maitlis 2012; Islam 2013) and responds to calls for philosophical approaches to organizational care (Kroth and Keeler 2009; Tomkins and Simpson 2015).

Evolution of the Concept of Care

Before we discuss philosophies of care, it is germane to provide an historical background to the ethics of care. The contemporary struggle between two contrasting meanings of care emerged in Greco-Roman times; care as burden, and care as solicitude. This aetiology led to two interpretations of care: first as worries and anxieties and second as concern for a person’s well-being (Burdach 1923). Philosophers such as Seneca did not view care so much as a burden, rather as the way to become truly human; he espoused, “the good is perfected by care (cura)” (trans. 1953, pp. 443–444). Seneca defined care as solicitude, which suggests extreme devotion and attentiveness (Burdach 1923; Seneca 1953).

Possibly the greatest influence on the perception of the care concept was the Greco-Roman myth of the goddess Cura, an ancient narrative that reveals positive aspects of care including “the primordial role of Care is to hold the human together in wholeness while cherishing it” (Ryle 1949, p. 350).Footnote 1 Danish philosopher and religious theorist, Søren Kierkegaard incorporated discussions on Cura, in his writing; he proposed care as key to understanding human life and the pathway to authenticity (Reich 2014).

Contemporary Constructs of ‘Care’

Historically, one meaning of care has been attention, to pay heed to, and this remains a crucial component of care. Simone Weil (1909–1943), a significant thinker on care as central for ethics, viewed attention is an integral to care. She defined attention as suspending thought and being prepared to engage with the person. For Weil, to care for a person means to give them full attention.

With Carol Gilligan’s ground-breaking text “In a different voice” (1982), scholarly discussions on care gained momentum. Gilligan sought to progress a systematic philosophical ethic of care in the context of moral development. Her perspective, which she called ‘the care perspective’, identified vital concerns: to avoid hurting and alienating individuals and to foster and protect attachments between them (Gilligan 1982). Her ethic of care is rooted in the view of persons as “relational and interdependent, morally and epistemologically,” rather than autonomous, self-sufficient beings (Held 2006, p. 13).

Gilligan contends that women exist in a moral universe, embedded in “a world of relationships and psychological truths where an awareness of the connection between people gives rise to a recognition of responsibility for one another, a perception of the need for response” (1982, p. 30). Further, she argues that an ethic of care had been ignored since women were overlooked in early studies of moral development (e.g., Kohlberg 1981). When applied to women, these male-based theories categorized women as deficient (Gilligan 1982). Consequently, Gilligan’s primary motive to develop a women’s ethic of care was based on valuing and celebrating the feminine within a ‘sex difference’ construction of gender. Compared with men, women are more predisposed to recognize moral dilemmas in terms of personal attachment versus detachment. Based on her own psychological research, Gilligan moved the ethic of care from the periphery to the center of a moral theory development for women (Clement 2018).

Concurrent with Gilligan research (Brown and Gilligan 1992; Gilligan et al. 1988) were developments in feminist ethics. Held (2006) expanded a philosophical understanding of the care ethic from feminist philosophy that criticized an ethic of care which disempowers women. But Held’s account of care is valid for everyone, not just women and other minorities, but also those for dominant groups and men. She describes the ethics of care as a normative theory with focus on relationships based on the universal experience of caring; a type of virtue ethics (Hursthouse 1999). Held recognizes similarities between these two theories but explains ethics of care as based on caring relationships, whereas virtue ethics has dispositions as its primary focus. Along with other feminist thought where relational experience is key, the ethic of care centers on the needs of other people for whom we have responsibility. This leads to a view of people and society as interdependent and relational rather than one element in a collection of virtues (2006).

Due to its association with women, the care ethic is frequently seen as a feminine ethic with feminist ethics, feminine ethics, and care ethics often conflated. The long-held view of a feminine ethic of care is rooted in women’s biological capacity and motherhood expectations, resulting in all women being essentialized with ‘feminine’ traits such as compassion, empathy, and kindness. The pervasive view, care is feminine, has lingered although women are diverse, with some women not exhibiting care, and some men displaying strong tendencies to care.

Feminine and feminist ethics are differentiated by the extent to which they engage in critical analysis of the association between women and care, and power-related consequences. Writers such as Tronto (1993, 2010), Held (2006) argue convincingly for overlaps between care and feminist theory, whilst challenging the associations of care with women. Traditional ethical theories have been based on men’s experiences. Ethics and the ethic of care cannot solely be viewed from the standpoint of either women or men exclusively and still be considered ethics but must be applied to all rational beings.

Heideggerian Care: Sorge

These developments in organizational care and history of the care ethic set the scene for Heidegger’s philosophy of care, a core concept for this paper. German existential philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) was strongly influenced by Kierkegaard’s teaching on care as the pathway to authenticity. Heidegger acknowledged his theorizing of care arose from and added to the “Cura” tradition and alluded to the Myth of Care as the primal explanation of his argument (Reich 2014). The German word “Sorge” translates as “care for” or “concern for” even “anxiety for” (others). While Heidegger’s philosophy of being has many facets such as moods, authenticity and angst, care is a preeminent part of his being-in-the-world. In fact, he argued that the question of being is central, and care addresses the need for humans “to be.” Existentially care lies at the heart of the structure of being; it signifies our existence and gives it meaning.

Indeed, Heidegger argues Sorge encapsulates the two elementary actions of human existence: towards others and towards the future and has been described as “an existential-ontological state characterized by both ‘anxiety’ about the future and the desire to ‘attend to’ or ‘care for’ the world” (Shields 2013, p. 89). Existing and ‘being-with’ others implies some degree of care, emotional and practical involvement; it includes caring-for and being-cared-for. Care also implies a future orientation; part of being human is projecting ourselves and moving forward. Heidegger’s care structure of future-past-present reveals what is most important to us as human beings, what possibilities are chosen, revealing what we truly care and are concerned about (1927/2011).

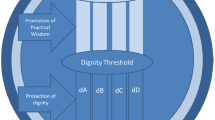

As in Greco-Roman times, Heideggerian care can have a double meaning: anxiety and solicitude. The first represents our struggle for existence and often involves immersing ourselves in trivia to avoid facing up to the questioning of our being. The second meaning (Fursorge) we give primary attention in this paper means nurturing and caring for both the earth and our fellow beings. FursorgeFootnote 2—solicitous care—is characterized by consideration and self-control and can be seen on a day-to-day basis in a positive mode in two ways. Firstly, care is described as ‘leaping-in’ as out of concern, a care-giver takes over another person and solves the problem on the other’s behalf. This kind of care creates inequality between the two. The person receiving care can be controlled and dependent, with restricted agency.

Secondly, another kind of positive Sorge is described as “leaping ahead” (p. 159) translated as “intervene ” or “stand in for him/her.” The person receiving this kind of care experiences freedom, increased meaningfulness, new insights, and consequently feels more fully human. Leaping ahead might involve listening rather than offering advice and asking questions rather than trying to problem solve (Gardiner 2016). Instead of being results-driven the effect is to open up possibilities. The person can find their own solution, rather than being molded into an ideal. Further, they can experience an ontological shift and choose the possibility of a different ‘way-to-be’ (Heidegger 1927/2011).

Tomkins and Simpson (2015) suggest three facets to ‘leaping-ahead’ namely anticipation, autonomy, and advocacy. Anticipation alludes to the future-oriented aspect of care that is predictive and forward-thinking. Autonomy reflects the space that leaping-ahead provides the care-recipient and enables them to move forward independently. Advocacy resonates with Macann’s (1993) idea of ‘standing up for’ and contrasts with the translation of leaping-in or ‘standing in for.’ Tomkins and Simpson (2015) further suggest ‘empowerment’ can be used as a synonym for ‘leaping-ahead.’

In everyday life, care reveals itself between these two extremes of positive (solicitous) care, care that “leaps in and dominates,” and care that “leaps forth and liberates” (Heidegger 1927/2011, p. 159). Although both are positive, the first results in a person becoming dependent and dominated whereas the second results in a person being enabled and experiencing meaningfulness. ‘Leaping-in’ tends to be concerned with the present, whereas ‘leaping-ahead’ has a greater sense of possibility and future-focus.

While care can be directed by consideration and attentiveness, more typically it is also found in imperfect states described as “deficient and indifferent” (Heidegger 1927/2011, p. 158). So often we are busy with everyday activities without much thought for others. For instance, we may not even notice the person who is with us, we can become preoccupied with something on our phone rather than someone in the room. What this can mean is we adopt an instrumental approach to life where people and things become commodified, objects to be used and discarded. If we want to act in non-instrumental ways, then we must think about how our behaviors affect others which necessitates we recognize “the importance of care” (p. 88). Subsequently when we don’t experience care, or experience it in an imperfect or negative state, we feel inconspicuous, we don’t “matter” to others and can become disillusioned and purposeless (Gardiner 2016).

Further, because we live most of our lives just getting on with the ‘norms’ and with others, we forget what it means to be authentic. Heidegger (1927/2011) argues that to be authentic we must do two things: we must be resolute and then we must be open both towards others and to the world around us. On the other hand, authenticity means standing up for what matters to us and being decisive; aligning with those things that matter and distancing ourselves from those things that don’t. This is the type of authenticity we might define as care.

Arendt (1981) further expands on Heidegger’s explanation of authenticity as care. She contends it arises from conversing and working with others; it develops from our caring commitment to others and to the world and is demonstrated by our readiness to be involved in our communities. Arendt argues that a world that is built around the self is insufficient to ensure that we genuinely care and respond to each other’s needs; what matters most is being aware of our responsibilities for each other. Arendt therefore fleshes out the Heideggerian view of authenticity as care and provides a view of relationships that focuses on our mutual responsiveness to one another. For Arendt, this responsiveness is central to being ethical (1958, as cited in Gardiner 2015).

Various writers have expressly linked the care ethic with Heideggerian care (e.g., Reich 2014; Tomkins and Simpson 2015) and expressed surprise, that while care is so central to Heidegger’s work and relevant for organizational scholars, it has not been taken up (Reich 2014). Indeed, writings on care and the care ethic have clear resonance with the Heideggerian concept of care, have a strong relational focus (Gilligan 1982), and pay attention to and consider the individual’s needs (Liedtka 1996). Yet, as Lawrence and Maitlis (2012) note discussions on the care ethic have been sporadic and limited and have concentrated on scholarship and life outside rather than inside organizations. We seek to address this gap. Our discussion now moves to consider evidence of Heideggerian care in action, from an empirical phenomenological study set in the education sector.

This Research Study

We first explain the methods used, then present findings from our empirical study, that used Heideggerian hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate women’s career meanings (van Manen 2016). A phenomenological research methodology is the study of lived experience. It seeks to answer the question: “What is this experience like?” (Gill 2014; Ehrich 2005; Gibson and Hanes 2003) and reveals the experience participants have of a phenomenon and how they make sense of their lived experience of that phenomenon.

Specifically, this present study employed van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenology (1990) which spans descriptive and interpretive phenomenology and was initially developed within the discipline of pedagogy (Gill 2014). Differentiating itself from other types of phenomenology, van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenology is both “descriptive”, attending to “how things appear” and interpretive, because “there is no such thing as uninterpreted phenomena” (van Manen 1990, p. 180). For simplicity, we use the term ‘phenomenology’ to encompass van Manen’s (1990) ‘definitions.

Phenomenology reflects the epistemological view that theory is inductively generated and does not involve propositions for research (Creswell 2007); it provides a way of revealing the meaning participants make of the phenomenon from their accounts. Phenomenological understanding is subtle and appears from “the ordinary emergences of human experience and meaning” (p. 47). It asks, “How does the meaning of this experience arise?” (van Manen 2016, p. 38). The rewards of phenomenology are that it offers moments of “seeing meaning” into the heart of a phenomena (p. 60). Through phenomenology we can deconstruct phenomena such as love to “thoughtfully and tactfully aim for the perfection” of love in our lives (van Manen 2016, p. 62).

In spite of frequent exhortations about its potential to provide a deep understanding of human experience, the application of phenomenology to organizational research is rare (Ehrich 2005; Gibson and Hanes 2003). Ehrich argues it provides a way to explore a range of complex interpersonal activities involved with the “human side” (2005, p. 8). Her work has been influential in encouraging phenomenological studies using small numbers of participants (e.g., Roter (2011), n = 18; Train (2015), n = 11; Martin (2015), n = 10). These studies aimed to gain deep understanding of the phenomenon of interest and to maximize the richness of the data.

The focus of this study was women’s careers and hence the methodological approach required the participant exercise reflexivity in her career accounts. The research sought to answer the question: “How does Heideggerian care provide a way to understand the meaning women make of their career?” Key selection criteria were women who have experienced a career and were willing to talk about these experiences. The education sector was chosen as women involved in education were likely to have good communication skills. It was also a context with which the authors were familiar. Purposive sampling was used to recruit and select women who met the primary criteria. The aim was also to have diversity of age and experience amongst the participants to increase the possibilities of “rich and unique stories of the particular experience” (Laverty 2003, p. 18). Advertising for participants was firstly through a popular women’s magazine and then through snowballing from contacts of the researcher(s). The resulting sample consisted of 14 women participants, all professionally trained as educators, and aged between 34 and 61 years. Details are contained in Table 1 below.

In phenomenological methodologies, the challenge for the researcher is to stay as close as possible to the participant’s experience. Consequently, the interview aimed to gather rich in-depth accounts by engaging with participants in ‘conversational interviewing’ (van Manen 1990). This technique enables participants to reconnect with their original experiences. Typically, the interview began with an introduction to the research and an invitation for the participant to talk about what she was currently doing. As the interview progressed prompts and probes were used, to encourage her to go deeper into an issue while fostering a relationship of trust, where safety and openness is critical. Only a few direct questions were used, including: “What about finding meaning and purpose: do you think your work has helped you find out who you are?” “What has driven or impelled you to achieve the things you have: has there been a need for frequent change and/or re-invention?”

Reflexivity is crucial in the interview process and van Manen (1990) warns the researcher not to be tempted to reach an understanding too quickly, to remain ‘open’ and to consider any influences that might hinder the exploration of the phenomenon. Accordingly, the researcher kept a journal throughout the interview process and notes taken after each interview enabled the interview to be brought back to life during the interpretation of transcripts. These notes recorded impressions, perceptions, and reflections of the researcher as well as the mood and emphasis the participant gave to aspects of the interview.

From the transcripts, anecdotes were crafted to describe key aspects of a woman’s career using a process outlined by van Manen (2016). A total of between four and eight anecdotes were written for each participant. These “lived experience descriptions.” sometimes had a narrative shape in the interview but more often they were constructed by the first researcher through a piecemeal editing process from the transcripts; each contained a powerful element of a woman’s lived experience. Essentially, each anecdote is a short story, describes a single incident, has some concrete details, and several quotes, and closes quickly after the incident often with a final ‘punchy’ last line encapsulating the point of the anecdote (van Manen 2016). An example of a punchline is from participant Miriama who, when describing the early influence of two high-school teachers said, “and they really believed in me; they said, ‘you can be something else.’”

Thus, an anecdote can be a captivating narrative with phenomenological power which stirs us and pushes beyond the constraints of what we already know from our own experience in a “radical yet disciplined way of seeing with fresh, curious, eyes” (Finlay 2014, p. 122). When read aloud, listeners can connect with the phenomenon being recounted (van Manen 2016). These anecdotes are how the essence of the phenomenon can be grasped, emotions evoked, and meanings uncovered, and their effect is to make experiences close and intense. An anecdote is a narrative device taken from lived experience that steps back from and reflects on experience. However, the anecdote used phenomenologically should not be confused with factual empirical accounts; its value is for its powerful, effective conceptualization of things that resist ready definition (van Manen 2016).

Once the anecdotes were complete, they were sent to participants to review for accuracy and intent. After all participants gave their permission, data analysis proceeded inductively interpreting themes. The anecdotes were then hermeneutically interpreted using the philosophical tenets of Heidegger (1927/2011). Broad themes were developed through an interpretive process which employed both selective and wholistic reading approaches (van Manen 2016). Rather than a mechanical application of a frequency count of coding of terms, analysis induced the themes dramatized in the evolving of meaning of the text. Phenomenological themes are structures of experience, metaphorically speaking van Manen (2016) describes them as knots in the webs of our experiences around which certain lived experiences are spun and lived as meaningful wholes.

Findings

As discussed earlier, our guide for this interpretive study was the Heideggerian care construct of Sorge. It provides a way to understand the meaning of ‘being’ (1927/2011) and to reveal what is most important to study participants. To interpret how participants found meaning in their career, an integral part of the process involved understanding how their ‘way-to-be’ shifted and changed throughout their career journey. These ontological shifts were described by participants as due to being shown care by key people. Therefore, as meanings of experience were uncovered, the care structure was a means by which data analysis took place and women’s experience of what was important to them was exposed. Thus ‘being-in-the-world-with-others’ or ‘being-with’ stories came together as a key theme that revealed an ethic of care was significant in women’s sense of meaningfulness in their work and career direction.

The following sections provide examples of how an ethic of care is lived, illustrated by excerpts from the phenomenological anecdotes. Several qualities or characteristics of being shown an ethic of care emerged: long-lasting impact in everyday situations; paying attention; identity formation; and to alleviate stress.

Leaping Ahead: Long-Lasting Impact in Everyday Situations

Women’s construction of meaning in situations where they experienced an ethic of care was a description of care expressed through everyday practices or events (Lawrence and Maitlis 2012). Women described incidents where something quite ordinary happened, yet through these routine exchanges they gained greater self-understanding and more confidence.

One participant, Kiri, an Indigenous (Māori) school principal commented about the influence of two Pakeha (white) teachers: “it wasn’t that they knew Te Reo Māori [language] or anything about Māori culture. It was rather than on a human level they were people who could see potential. They simply encouraged me.” Kiri describes an incident where other students teasingly asked if she cheated because she got such a good mark in a test and one of the teachers stepped in and stood up for her, and from then on, she thought, “I can do this.” She comments,

It wasn’t much to her, but what she did for me, in my head as time has gone on, was very significant. I can put my finger on those times and the things that she said. Even though language and culture counts, what also counts is people who believe in you. And if you can do nothing else as a teacher for Māori it is to believe in them and to encourage them. Look it must’ve been significant, I’m still telling that story to this day. (Kiri)

The power of a phenomenological approach is it can expose everyday things not seen from the outside (Laverty 2003). Participants attested that quite simple things had long-lasting impacts on them. Kiri comments “when I’ve spoken to Māori about that kind of thing happening, some people have shaken their heads and said “I think you’re putting too much on it, romanticising it. It was other things as well.”” Heidegger attests, this kind of care, makes us feel more human, and Kiri is adamant, “on a human level” these acts of teachers noticing, reinforced her potential.

Carol, a primary school teacher who trained as a teacher in her thirties, describes feeling constrained and held back by her background as an adopted child. She felt disenfranchised and struggled to find her own identity. A teacher in her first teaching practicum who looked at her and commenting on her readiness to teach said: “I don’t know why you didn’t go [teaching] years ago.” Carol goes on:

I was blown away. Later, when I would be thinking about what to do, it was her comments that came back to me. (Carol)

Women described how a few prescient words spoken at a key time, enabled them to find meaning and direction. These interactions were not as a response to a traumatic or significant event, they occurred within the context of established work relationships (Lawrence and Maitlis 2012). Although seemingly unremarkable, they were described by participants as key career moments that retained their intensity over time; as Miriama commented “their voices are still in my head.”

Leaping Ahead: Paying Attention

The notion of being watched, noticed, or having someone pay close attention (Weil 1977) featured in participants’ descriptions of people who showed care to them. Miriama, mentioned above, is a young Indigenous (Māori) teacher and now manager in a secondary school. She came from a small town where “not many people left. …I was probably more likely to become a teenage Mum, than to leave that town”. She describes how two teachers noticed and paid attention to her, anticipating what her pathway should be and said “of course you should be looking at plans for university. Your path isn’t to work in the supermarket, because you’re really talented.” Miriama comments: “They made me think I definitely could go to university that I could move out of that small town and that I could do other things.” The teachers directed attention and recognition of her needs enabled Miriama to become someone who was different from other young women in her town. They constantly expected her to succeed. She expresses deep emotion as she recalls “I don’t think they realised what an impact they had on a young girl living in a small town.” The teachers’ attentive care had a humanizing effect that enhanced self-esteem (Islam 2013).

For Tina, a young academic, having someone pay close attention to her impacted career agency and confidence which led to a career transition. She recalls the short, but timely and profound influence of a visiting Professor:

Three years ago, we had an Associate Professor join us from the UK, and he just instilled this extra confidence in me. He’d say to me, “Oh yes, you could quite easily do this” or “Why don’t you apply, this would be quite good for you.” And, he would also say, “You know, you’re quite ready to apply for Associate Professor.” (Tina)

The Professor, who worked in the department for 6 months, exhibited behavior different from Tina’s other colleagues: “I haven’t found that other people take the time to actually know what your strengths are, to take an interest in you.” A mark of inattentive care is people are often too preoccupied with their own things and fail to notice and pay attention to others around them (Gardiner 2016). Tina goes on:

And I did apply for Associate Professor. By then he had left. If it wasn’t for him, I don’t think I would have applied. When he came, I felt “Oh here is somebody who actually understands me, who takes time to know what I research or what my strengths are.” (Tina)

The Professor took time to know Tina and to consider her “just as she is” (Weil 1977). “He got to know me” as an individual with potential (Islam 2013) and anticipated Tina’s next career move. Leaping-ahead has been suggested idiomatically as “standing up for” (Macann 1993). Rather than control, or diminish, it anticipates so the care-recipient can exercise autonomy in making their next steps (Tomkins and Simpson 2015). It has a transformative quality that helps a care-recipient to “grow and develop” (Bass and Riggio 2006, p. 3). Through this interaction Tina sought and gained promotion to Associate Professor.

Leaping Ahead: Identity Formation

Another characteristic of leaping ahead is it can contribute to the development of identity. Miriama, as a young Māori teacher describes how she used to watch three older senior Māori women on the staff whom she admired and wanted to emulate. She thought: “That’s the sort of teacher I want to be, strong and well respected and making a difference.” However, the “watching” was reciprocal as Miriama relates:

In my first year there was a whole group of first year teachers and several of us were Māori, but we weren’t doing things like Kapa Haka.Footnote 3 One of those three women was like the kuiaFootnote 4 of the school. And 1 day, she said to me, “Whether you like it or not, the kids view you as Māori. So, you have to represent us in a really positive way.” I was really shocked. “Oh my gosh, who is this lady telling me this? I know I’m Māori.”

The kuia went on:

“The students look at you and they see a Māori face and a Māori name. So, you need to make sure that at all times, you represent us in a way so that they will look up to you.” And I realised it was true. I’d been a bit shy, a bit reticent about being Māori. About standing up and saying what I thought. But I did want the kids to look at me and say, “I could be like her, she’s not afraid.” It made me think I shouldn’t always be the person at the back, such a wallflower. It was really defining. (Miriama)

Tomkins and Simpson (2015) contend, care is not to do with kindness or being nice, rather it is linked to agency and self-organization. In fact, they argue, “in a Heideggerian world, compassion, kindness and niceness are neither necessary nor sufficient for care” (p. 1023). Miriama’s initially confronting expression of the care ethic in action confirms this view. She comments, “At the time I thought she was a grumpy old lady, a little terrifying, but that’s because she cared. She’d give you a hug but also tell you off.” Honneth (2008) comments on the dominating effect of management processes that involve watching people in order to monitor or measure, to scrutinize. Yet, in this situation the kuia watched and paid close attention to Miriama not to monitor but to care for her. She saw Miriama for who she was: a young Māori woman unsure of her own cultural identity. The incident happened over ten years before the interview when: “I wasn’t even that Māori” But now:

I bring a different perspective…. I’m Māori and the students are forming opinions about themselves by the way that I act and behave…. the students are watching. I want them to see someone who’s proud of who she is. (Miriama)

Heidegger contends ‘leaping-ahead’ (1927/2011) has the effect of helping the care-recipient become more authentically who they are. Through the kuia’s intervention Miriama was empowered to take more responsibility for her actions, to speak up, and become a role-model for her students (Tomkins and Simpson 2015). Aware of her timidity and lack of connection with her Māori heritage, this interchange increased her confidence: she became “a strong Māori presence who teaches at this school.”

This early-career incident was the forerunner of later choices Miriama made, to surround herself with other key people to be in a school where she could build on her strengths as a subject teacher and to respond to a head of department’s call to “come on board, then you can be promoted.” She recounts she learnt the importance of surrounding herself with people who believed in her potential and who cared about her future, people who believed she could “do anything.” She comments, “You have to surround yourself with people who are positive. Because if you don’t have them; it’s too easy to make other choices. People who believe in you, that you can achieve more, that you can do anything.”

Heideggerian scholar Harman describes how our lives can become interwoven with these different influences, “all parts of her world are fused into a colossal web of meaning in which everything refers to everything else” (2011, p. 63). These “key people” had a compounding effect and became part of Miriama’s lived experience, described as a kind of “heritage” of care for Miriama throughout her career (Harman 2011). It could be argued this incident might be described as a combination of mentoring and role modelling. Yet, Miriama does not describe having a mentor or role models. Instead she tells how these people, involved themselves in her career, paid her attention and enabled her to become more autonomous. In the situations described above, there was no formal intervention or practice; rather the interaction occurred in the context of an everyday workplace relationship (Islam 2013; McAllister and Bigley 2002).

Leaping-Ahead: To Alleviate Stress

At times leaping-ahead can involve intervening or standing up for a care-recipient at a time of stress (Macann 1993). Sally, a senior manager in a secondary school, describes how she ‘stood up’ for Lara, a young teacher who was:

I thought, pretty close to having a breakdown. I said (to my principal) I think this teacher is going to fall over unless you do something. I could use my life coach and you could get this girl back on her feet again. Without spending a huge amount of money, you can make a huge difference to her.” The boss wore it and Lara got what she needed. I didn’t have any conversation with Lara, but I picked up that she was at breaking point and that was my solution. (Sally)

Sally’s own career had been difficult over the past several years before the interview and she comments:

I think maybe, that I am a little nicer than I was…a little softer. I’ve been knocked down, but I’ve picked myself up and made myself better than I was before. I think when you really get knocked around; you are a little kinder about other people because you know what it feels like to be knocked yourself. (Sally)

Writing on recognition theory, Honneth and Margalit (2001) state when individuals feel their self-worth has been ignored, they feel alienated or invisible. Sally has sometimes felt “passed over” and “inconspicuous” resulting in a temporary lack of meaning. She has experienced the results of being shown inattentive care, often more typical in our everyday lives (Gardiner 2016). Yet, she exhibits what Erikson says is “the generational task of cultivating strength in the next generation” (1963, p. 274) validating Heidegger’s central tenet that exercising care is part of what it means to be human; we are compelled to care. Honneth (2008) notes recognition of another colleague’s need can be a ‘struggle’. Yet, it is this kind of caring recognition that acknowledges us in our humanity and impels us to move towards future possibilities (Heidegger 1927/2011).

Discussion

For women in this study, being shown Heideggerian care had long-lasting effects, was meaningful, and empowering. They sought to pass on the benefits of receiving care to the next generation, with findings having clear implications for care in education. In particular the benefits of care were potent for women of color. These groups still face obstacles in accessing career benefits (e.g., pay, power, prestige), due to sexism and racism and glass-ceiling effects (e.g., Cook et al. 2002; Worthington et al. 2005). For example, Kiri and Miriama are Indigenous (Māori) and Tina is Middle-eastern. Miriama, the young Māori teacher, had a head of department who was a gate opener; he could see what might potentially be in the future and made a pathway for her, saying “Come on board, and you can be promoted to these other positions.” Bosley et al. (2009) identify the function of a gatekeeper in their typology of “career shapers,” people who helped direct an individual’s career.

Returning to Tina, the academic who experienced care from the Associate Professor, exemplifies other participants who commented they were developed by being shown care, subsequently they were predisposed to show care for others (Seneca 1953). It was of particular note that as educators, they sought to “pass it on” to ensure the next generation were also improved by care. Tina comments on the importance of recognizing what other (younger) colleagues need “I try and do that (now) with younger people in our department.” Carol the primary teacher who trained in her thirties talked about passing on care: I think I pass that [confidence] onto the children I’m teaching. Someone did it for me, I’m going to do it for you.” (Carol)

These practical implications of Heideggerian care have particular relevance in the education sector. Owens and Ennis (2005) argue that inclusion of the ethic of care as pedagogical content would enhance novice teachers’ ability to care for themselves, create a caring environment for learning, and establish caring relationships with their students. Agne’s research (1999) found with the development of deep caring comes a high level of dedication and attention prevalent among expert teachers. Such caring has a leavening function as a small quantity can cause growth in the cared-for; thus, care has potential to spread as expert teachers model attention to student-other rather than teacher-self (Agne 1999). While there is a growing body of writing on the importance of teachers care-for-others in education, neither Owens and Ennis (2005), nor Agne (1999) mention the importance of care-for the teacher. Our participants did express a need to be with people who recognized and paid attention to their needs. They related how they deliberately ‘chose’ people who verified their sense of identity so they could maintain harmony with themselves (Harter 2002). The leavening effects of care can be clearly seen in these accounts of Miriama, for example, who learned to surround herself with key people and in others like Carol, who sought to ‘pass it on.’

Contributions and Conclusions

Reflecting on our study, we identify clear contributions to extend ethic of care theory and practice through the lens of Heideggerian care. Although the concept of Heideggerian care is complex and difficult to fully grasp, we can realize its benefits particularly in the interventions of ‘leaping ahead.’ Interestingly, when participants were asked about how meaning occurred in their career experience, they described the effects of being shown care. Their accounts reveal the power of an ethic of care and its ability to open up possibilities, rather than find solutions or results. The examples they gave were future-focused and empowering, effects that align with ‘leaping-ahead.’ The subtle insights gained through phenomenology provide a way to “see” meaning as it appears at the core of a phenomenon. We suggest a phenomenological approach has enabled the deconstruction of the care ethic so that a more holistic view of care in action has been gained (van Manen 2016).

Only a few scholars have discussed the care ethic in the context of working relationships and organizations, and Heideggerian care is novel in organization studies. Our findings from an interpretive phenomenological study contribute to this emergent literature. Participants affirmed the significance and meaning provided by relationships where an ethic of care was shown to them. These relationships were not structural formal interventions, rather they were naturally occurring, spontaneous interactions, and did not necessarily evolve over a long period. Yet, by receiving care, the recipient gains a temporary reprieve from the angst that trademarks human existence. Heideggerian care in action enables an ontological shift that transforms and energizes; the effects of being shown an ethic of care are anything but temporary.

As researchers we wonder what it is about Heideggerian care that effects this kind of life-long impact? The positive interactions described in the interviews shared a common feature, namely the person showing care exercised genuine concern for the other. There is an organic, unrehearsed sense about these simple acts of recognizing, paying attention, and taking responsibility. These interactions merely involve the care-giver consciously paying attention to the care-recipient, watching them, and ‘leaping.’ Heidegger argues we are all predisposed to care; it is at the heart of our being and essential to our relationships and ventures. However, he also notes we are often preoccupied with the prosaic and ordinary; therefore, we fail to notice and pay attention to the needs of others, to take responsibility for them in empowering ways. Inattentiveness and a lack of concern by others was commonly expressed by study participants. Essentially being shown a positive ethic of care is rare.

While Heidegger conceptualized care as an elemental predisposition, contemporary theorizing and our empirical study provides preliminary evidence that Heideggerian care may have the potential to be developed. Our empirical study extends previous theorizing by providing evidence from everyday experiences. Heidegger’s account of care provides a humanistic model can be used to benefit organizations and employees, due to its multi-faceted nature and its emphasis on relationality and responsibility. Within organizations it may be possible for people to learn how to operate in this way and so create an organizational culture of caring.

Tronto (1993, 2010) argues for deliberate expressions of care that are personally tailored, and gender neutral; Lawrence and Maitlis (2012) contend more action and less theorizing is needed and not just care that is triggered by a crisis, or motivated by a cause, while Islam’s (2013) treatise on care as recognition provides a viewpoint on care as precognitive and responsive. We see alignment between our work and these scholars. Their lively discussion of the care ethic as including recognition, social practice, and everyday discursive practices converge in Heideggerian care. Along with Tronto, Lawrence and Maitlis, and Islam, we argue for a more relational and ‘personal’ view of the care ethic, one that occurs within the context of naturally occurring relationships, thereby providing a different twist to previous interpretations of the care ethic (Gilligan 1982; Noddings 2003).

We further argue that Heideggerian care is a promising theoretical construct because it is undergirded by a strong philosophy. It avoids rule-based, impersonal interventions and helps individuals to gain increased agency and meaningfulness in their careers. This paper contributes to literature on the care ethic in two major ways. Firstly, our empirical findings illustrate Heideggerian care in action using excerpts from a phenomenological analysis. Secondly, we argue that recent interpretations of the care ethic (Gilligan 1982; Held 2006; Tronto 2010) can be positioned alongside Heideggerian care to expand theoretical understandings of the care ethic.

Viewing care through the lens of a Heideggerian care construct resists the temptation to essentialize and constrain the care ethic to empathy, niceness, and kindness. A Heideggerian care ethic involves self-management and agency, a deliberate response that is not driven by sympathy for a cause or a person. This involvement eliminates the gendered perception of care, that has historically risked being seen as a women’s morality and subject to feminist critique (Held 2006). This perception has been argued to trivialize the value of the care ethic by continuing to be aligned with values and virtues culturally associated with women, thus providing a deficiency model of care (Tronto 2006). Rather, care viewed through a Heideggerian lens is concerned with meeting individual human needs. It is neither the result of a process of moral development aligned with women, nor is it justice or rule based and associated with masculine development.

In addition, hermeneutic phenomenology not only uncovers meanings of human experience but also provides a means of understanding the ontological power of Heideggerian care. For Heideggerian care in action is not just about doing, it also impacts on our way of being. Our findings reinforce Heidegger’s supposition of care as an essential condition for existence and strengthen our understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of an ethic of care.

We contend hermeneutic phenomenology has provided an apposite methodology to investigate how the care ethic can provide meaningfulness and career agency for women. We suggest future research opportunities springing from our work. By design, phenomenological research studies involve a small number of participants, the primary aim being to access rich and deep human experiences. The study participants were from the education sector, an area seen as ideally suited to this type of research. However, future hermeneutic phenomenology research could explore careers in other contexts and industries, using a greater diversity of participants. For example, a comparative study using both men and women would add to existing research on the gendered differences in careers. Studies investigating other professions and work sectors would add to the findings.

Our empirical findings reveal the power of an expressed care ethic. We contend that research that seeks to develop the care ethic in individuals and organizations is crucial to build on these findings. We encourage research that extends our knowledge of care-in-action and the ethic of care.

All ethics are based on a view of the human condition: the care ethic is impelled by a vision of our capacity to show care. We argue the care ethic, manifest as Heideggerian Sorge can provide a valuable theoretical and philosophical construct. It also guides a practice through which individuals in organizations might gain more understanding and meaning from their work, increase their career agency, and recognize ‘good’ ways of working together.

Notes

A full discussion of the development of the history of the notion of care can be found in the classic article in the Encyclopedia of Bioethics by Warren T. Reich. [Revised edition. Edited by Warren Thomas Reich. 5 Volumes. New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 2014, 4th ed., pp. 319–331].

Heidegger used two other German words along with Sorge to describe care. Besorgen, translates as to get or obtain something for oneself or someone, and Fursorge, translates as actively caring for someone who needs help, also known as solicitude. Sorge is the root for care made manifest: Fursorge and Besorgen. Sorge is concerned with being: “ontology” (Tomkins and Simpson 2015). In this paper, for simplicity we use the root word Sorge for solicitous care—Fursorge.

Māori performing arts.

Māori woman elder.

References

Agne, K. (1999). Caring: The way of the master teacher. In R. Lipka & T. Brinthaupt (Eds.), The role of self in teacher development (pp. 165–188). Albany: State University of New York.

Arendt, H. (1981). The life of the mind. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. (2006). Transformational leadership. London: Erlbaum.

Bosley, S. L., Arnold, J., & Cohen, L. (2009). How other people shape our careers: A typology drawn from career narratives. Human Relations, 62(10), 1487–1520.

Boykin, A., & Schoenhofer, S. O. (2001). Nursing as caring: A model for transforming practice. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Brown, L. M., & Gilligan, C. (1992). Meeting at the crossroads: Women’s psychology and girls’ development Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press.

Burdach, K. (1923). Faust und die Sorge. Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte, 1(160), 1.

Clement, G. (2018). Care, autonomy, and justice: Feminism and the ethic of care. London: Routledge.

Cook, E. P., Heppner, M. J., & O’Brien, K. M. (2002). Career development of women of color and white women: Assumptions, conceptualization, and interventions from an ecological perspective. The Career Development Quarterly, 50(4), 291–305.

Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Delios, A. (2010). How can organizations be competitive but dare to care? The Academy of Management Executive, 25(3), 25–37.

Dutton, J. E., Worline, M. C., & Frost, P. J. (2006). Explaining compassion organizing. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 59–96.

Ehrich, L. C. (2005). Revisiting phenomenology: Its potential for management research.

Erikson, E. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton.

Finlay, L. (2014). Engaging phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(2), 121–141.

Foss, N. J. (2008). Human capital and transaction cost economics. Center for Strategic.

Gabriel, L., & Casemore, R. (Eds.). (2009). Relational ethics in practice: Narratives from counselling and psychotherapy. London: Routledge.

Gardiner, R. (2016). Gender, authenticity and leadership: Thinking with Arendt. Leadership, 12(5), 632–637.

Gibson, S. K., & Hanes, L. A. (2003). The contribution of phenomenology to HRD research. Human Resource Development Review, 2(2), 181–205.

Gill, M. J. (2014). The possibilities of phenomenology for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), 118–137.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gilligan, C., Ward, J. V., & Taylor, J. M. (Eds.). (1988). Mapping the moral domain: A contribution of women’s thinking to psychological theory and education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harter, S. (2002). Authenticity.

Harman, G. (2011). Heidegger explained. Chicago: Open Court.

Heidegger, M. (1927/2011). Sein und Zeit [Being and Time] (J. MacQuarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). New York, NY: Harper and Row. (Original work published 1927).

Held, V. (2006). The ethics of care: Personal, political, and global. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hodson, R., & Roscigno, V. J. (2004). Organizational success and worker dignity: Complementary or contradictory? American Journal of Sociology, 110(3), 672–708.

Honneth, A. (1995). The Struggle for recognition, trans. Joel Anderson.

Honneth, A. (2008). Reification: A new look at an old idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Honneth, A., & Margalit, A. (2001). Recognition. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 75, 111–139.

Hursthouse, R. (1999). On virtue ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Islam, G. (2013). Recognizing employees: Reification, dignity and promoting care in management. Cross Cultural Management, 20(2), 235–250.

Kohlberg, L. (1981). The philosophy of moral development: Moral stages and the idea of justice. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Kroth, M., & Keeler, C. (2009). Caring as a managerial strategy. Human Resource Development Review, 8(4), 506–531.

Laverty, (2003). Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: A comparison of historical and methodological considerations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(3), 21–35.

Lawrence, T. B., & Maitlis, S. (2012). Care and possibility: Enacting an ethic of care throug narrative practice. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 641–663.

Liedtka, J. M. (1996). Feminist morality and competitive reality: A role for an ethic of care? Business Ethics Quarterly, 6(2), 179–200.

Lips-Wiersma, M. (2002). The influence of spiritual “meaning-making” on career behavior. Journal of Management Development, 21(7), 497–520.

Macann, C. (1993). Four phenomenological philosophers: Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty. Abingdon: Routledge.

Martin, R. M. (2015). The application of positive leadership in a New Zealand law enforcement organisation. https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/11348.

McAllister, D. J., & Bigley, G. A. (2002). Work context and the definition of self: How organizational care influences organization-based self-esteem. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 894–904.

Noddings, N. (2003). Happiness and education. Cambridge University Press.

Owens, L. M., & Ennis, C. D. (2005). The ethic of care in teaching: An overview of supportive literature. Quest, 57(4), 392–425.

Ployhart, R. E., & Moliterno, T. P. (2011). Emergence of the human capital resource: A multilevel model. Academy of management review, 36(1), 127–150.

Reich, W. T. (2014). History of the notion of care. In W. T. Reich (Ed.), Encylopedia of bioethics (4th ed., pp. 319–331). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Roter, A. B. (2011). The lived experiences of registered nurses exposed to toxic leadership behaviors. Doctoral dissertation, Capella University.

Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. London: Hutchinson.

Rynes, S. L., Bartunek, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Margolis, J. D. (2012). Care and compassion through an organizational lens: Opening up new possibilities.

Sayer, A. (2007). Dignity at work: Broadening the agenda. Organization, 14(4), 565–581.

Seneca. (trans. 1953). Seneca ad Lucilium Epistulae (R. M. Gummere, Trans., Vol. 3). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shields, J. (2013). Zange and Sorge: Two models of ‘concern’ in comparative philosophy of religion. In J. Kanaris (Ed.), Polyphonic thinking and the divine (pp. 89–96). Amsterdam/Leiden: Rodopi/Brill.

Skovholt, T. M. (2005). The cycle of caring: A model of expertise in the helping professions. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 27(1), 82–93.

Tomkins, L., & Simpson, P. (2015). Caring leadership: A Heideggerian perspective. Organization Studies., 36(8), 1013–1031.

Train, K. J. (2015). Compassion in organizations: Sensemaking and embodied experience in emergent relational capability. A phenomenological study in South African human service organizations, Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town.

Tronto, J. C. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge.

Tronto, J. (2006). Women and caring: What can feminists learn about morality from caring? In V. Held (Ed.), Justice and care: Essential readings in feminist ethics (pp. 101–115). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Tronto, J. C. (2010). Creating caring institutions: Politics, plurality, and purpose. Ethics and Social Welfare, 4(2), 158–171.

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience. Ontario: The Althouse Press.

van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing, Taylor & Francis Group. ProQuest Ebook sCentral, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aut/detail.action?docID=4693331.

Weil, S. (1977). The Simone Weil Reader. New York: David McKay.

Worthington, R. L., Flores, L. Y., & Navarro, R. L. (2005). Career development in context: Research with people of color. Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work, 225–252.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Both authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standard of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elley-Brown, M.J., Pringle, J.K. Sorge, Heideggerian Ethic of Care: Creating More Caring Organizations. J Bus Ethics 168, 23–35 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04243-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04243-3