Abstract

This study examines the varying roles of power, status, and national culture in unethical decision-making. Most research on unethical behavior in organizations is grounded in Western societies; empirical comparative studies of the antecedents of unethical behavior across nations are rare. The authors conduct this comparative study using scenario studies with four conditions (high power vs. low power × high status vs. low status) in both China and Canada. The results demonstrate that power is positively related to unethical decision-making in both countries. Status has a positive effect on unethical decision-making and facilitates the unethical decisions of Canadian participants who have high power but not Chinese participants who have high power. To explicate participants’ unethical decision-making rationales, the authors ask participants to justify their unethical decisions; the results reveal that Chinese participants are more likely to cite position differences, whereas Canadian participants are more likely to cite work effort and personal abilities. These findings expand theoretical research on the relationship between social hierarchy and unethical decision-making and provide practical insights on unethical behavior in organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People hope and expect that appointees to high-ranking positions will use their authority wisely and for the betterment of their organizations—or at least act in ways that are not detrimental to others. However, there is ample evidence that high-ranking members of organizations often behave unethically (Aguilera and Vadera 2008; Kulik 2005; Pearce et al. 2008; Sims and Brinkmann, 2003). For example, John Thain, the ousted CEO of Merrill Lynch, spent US $85,000 on a carpet to redecorate his office at the same time that his near-bankrupt company was laying off employees (Rus et al. 2010). Such behavior, which pursues self-benefit rather than showing concern for other members of the organization, violates societal norms and has negative effects on organizations.

Researchers have asked why those in higher hierarchical positions are more likely than those in lower positions to make unethical decisions, though most of these investigations of the antecedents of unethical behavior have been theoretical and conducted in Western contexts (Dubois et al. 2015; Galperin et al. 2011; Piff et al. 2012). Galperin et al. (2011) use social cognitive theory to suggest that higher status creates social isolation, which renders ethical regulatory systems ineffective and results in more unethical behavior. Magee and Smith (2013) use the social distance theory of power to explain the unethical behavior of those in high-level positions, arguing that power reduces empathy.

Although these theories provide meaningful insights for understanding the positive relationship between social hierarchy and unethical behavior, no empirical studies explore the simultaneous effects of power and status with a cross-cultural comparative design. To address this research gap, we draw on Chinese and Canadian samples to investigate and compare the unethical decision-making processes of people in high-ranking positions. We conduct a scenario experiment, using a role-playing game to capture participants’ unethical decisions (Bendahan et al. 2015). This comparative study exploits rich cultural contexts to contribute to theoretical research on hierarchy and unethical decision-making and improve our understanding of the antecedents of higher-ranking members’ unethical behavior.

We thus extend research on unethical decision-making in organizations in three ways. First, we clarify the hierarchical nature of organizations and focus on the discrete main and interactive effects of power and status on individual tendencies to engage in unethical decision-making. Second, we ask participants to provide reasons for their unethical decisions, to determine how power and status affect unethical decision-making. Third, we investigate whether the effects of power and status on unethical decisions differ between China and Canada.

These findings can inform further theoretical and practical research related to power, status, and unethical behavior in organizations. We suggest that predictions regarding the association between social hierarchy and unethical decisions could be unsound unless they consider the discrete effects of power and status. Empirical distinctions between power and status help determine whether and under what conditions—particularly cultural conditions—these hierarchical characteristics increase the tendency to make unethical decisions.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

In this section, we identify the core construct of unethical decisions and use social cognitive theory as a conceptual framework to introduce the factors in our model. Next, we distinguish between power and status and construct hypotheses for the relationships among power, status, and unethical decisions. Finally, we describe the cultural differences between China and Canada, introduce previous research related to national culture and unethical decisions, and derive predictions about the differing effects of power and status in China and Canada.

Unethical Decisions and Social Cognitive Theory

The term “unethical decision” refers to an intention, perception, or behavior that is morally unacceptable by societal standards (Jones 1991). In organizational settings, the construct includes misuses of position, resources, or authority for personal or organizational gain (Galperin et al. 2011; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010; Piff et al. 2012; Treviño et al. 2006). In this study, we focus on unethical decisions with harmful effects on organizations, as opposed to decisions that aim to benefit organizations. By engaging in self-serving behavior instead of showing concern for group members, members may harm others and violate societal norms. Accordingly, we define unethical decision-making as the pursuit of personal gain at the cost of group benefit (Bendahan et al. 2015).

Social cognitive theory offers a psychosocial explanation of individual moral thought and actions (Bandura 1991). The theory posits that people develop internal moral standards according to the cognitive information available to them from observing the consequences of certain behaviors in their environments. They use these cognitive standards in self-regulatory systems that control unethical behavior (Fida et al. 2015; Gino et al. 2011). There are two important elements in the cognitive process. The first is social hierarchy position, which affects the cost of unethical behavior, in that both power and status can reduce the cost of engaging in unethical decision-making. The second relates to perceived social norms in various cultures and environments: Although internal moral beliefs are personal, their development and structures are culturally dependent. In turn, several authors use social cognitive theory to explore the antecedents of unethical decisions. For example, Galperin et al. (2011) propose a conceptual model to explain why higher-ranking members of organizations behave unethically. They argue that status differences cause higher-ranking members to be less sensitive to the feelings of lower-ranking members, muting their capacity to recognize that their decisions hurt others.

Such propositions provide theoretical insights for explaining unethical decisions, but they also are incomplete, because status is only one dimension of social hierarchy. The other dimension-power-must be addressed to understand the relationship between social hierarchy and unethical decisions. Despite evidence that indicates the need to distinguish the two dimensions (Blader and Chen 2012; Magee and Galinsky 2008), few empirical studies simultaneously explore their effects on unethical decisions; it is thus unclear which dimension functions as the dominant predictor of unethical decisions. We also need empirical evidence to specify the positive relationship between status and unethical decisions and to determine whether the relationship holds in differing cultural environments.

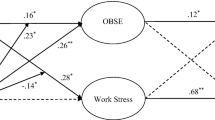

To address these questions, we use social cognitive theory as a foundation for a conceptual model that illustrates the antecedents of individual unethical decisions. We extend research by Galperin et al. (2011) by exploring the roles of power, status, and national culture in predicting unethical decisions. Consistent with previous research on social role enactment and the moralization of behavior (Bell and Hughes-Jones 2007), we expect the power and status facets of hierarchical positions to influence rationales for unethical decisions. Figure 1 shows our conceptual model.

Power and Status

Power is defined as an asymmetrical discretion in bestowing or withholding valuable resources or outcomes (Anderson and Brion 2014; Sturm and Antonakis 2015). It is associated mainly with formal rank and access to valuable resources, both of which enable power holders to have important and consequential impacts on others through activities such as resource allocation or punishment (Magee and Galinsky 2008).

Status is a relatively subjective concept; it is generally defined as the esteem and social worth that one has in others’ eyes (Piazza and Castellucci 2014; Wei et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018). Unlike power, perceived competence is the primary basis of status, such that the more competence a person displays, the more likely he or she will be conferred high status by others (Anderson and Kilduff 2009). Power cannot be conferred by others and is more independent; status relies on others’ evaluations (Blader et al. 2016; Cheng et al. 2013).

Although power and status have differing conceptualization and attainment processes, past research has tended to either conflate or confuse them (Fiske 2010; Fiske and Berdahl 2007), seemingly because they can reinforce each other (Magee and Galinsky 2008). For example, status may be associated with the accrual of discretion (Keltner et al. 2003), and power is often accompanied by the respect of others (Kilduff and Galinsky 2013). Nevertheless, there is evidence that power and status are distinct constructs, both conceptually and in practice (Anicich et al. 2015; Fast et al. 2012; Fragale et al. 2011). For example, a supervisor who controls the distribution of valuable resources to subordinates but does not satisfy performance expectations may have power but little respect in the social group, whereas employees who hold limited power may make important contributions to the group’s performance and become highly respected by others in the organization (Fragale et al. 2011). Extant evidence indicates that such differences between power and status are commonplace in organizations, so it appears necessary to distinguish the roles of power and status to understand why higher-ranking members of organizations behave unethically.

Power and Unethical Decision-Making

Power is a core property of high rank, which in turn is an antecedent of organizational unethical behavior (Dubois et al. 2015; Lammers et al. 2012; Rus et al. 2010, 2012). According to power approach theory (Keltner et al. 2003), those with high power control critical resources in organizations, which allows them to impose their will on others. Moreover, having more resources and independence from others causes people to prioritize their self-interest over others’ welfare and to perceive greed as positive and beneficial, thereby increasing unethical behavior (De Cremer and Van Dijk 2005). We predict that who have high power and more discretion about using that power are more likely than those with low power to engage in unethical decision-making.

Hypothesis 1

Power is positively related to unethical decision-making.

Status and Unethical Decision-Making

According to status characteristic theory (Berger et al. 1972), members of an organization earn respect from others when they display characteristics that are valued by and benefit that organization. Competence is a critical indicator of status (Anderson and Kilduff 2009; Li et al. 2016). Furthermore, people with the presumed potential to achieve high performance in the future are often assigned high status in organizations, whereas those who lack valued characteristics are assigned low status. According to expectation state theory (Berger et al. 1974), high-status organizational members can expect to receive more rewards from resource distributions. Moreover, some theoretical models indicate that status is positively related to unethical decision-making (Galperin et al. 2011; Kafashan et al. 2014), because the social isolation that accompanies high-status positions tends to decrease empathy and increase self-focused thoughts. Empirical evidence provided by Hays and Blader (2017) supports this argument from both status and legitimacy interaction perspectives; the authors demonstrate that feelings of entitlement increase in correspondence with people’s beliefs that their status is legitimate, resulting in increased self-interested behavior. Therefore, we assume that those with high status have a greater propensity to engage in unethical decision-making.

Hypothesis 2

Status is positively related to unethical decision-making.

According to the approach theory of power and status characteristic theory, we propose that power and status have an interactive effect on unethical decision-making. Power provides people with the freedom to pursue personal benefits and be less constrained in satisfying their personal goals. High status gives people reasons to be rewarded; it leads them to have less sensitivity to the needs of others and greater tendency to practice unethical behavior. Whether people take advantage of their asymmetrical power in a distribution process may vary according to people’s status positions. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Status moderates the positive relationship between power and unethical decision-making.

National Culture and Unethical Decisions

National culture refers to the collective beliefs or social norms that form in a certain society (Hofstede 1984; Tan 2002) and guide acceptable behavior. Literature related to national culture and ethics demonstrates that people’s perceptions of ethics vary culturally (Beekun et al. 2008; Eisenbeiß and Brodbeck 2014; Lehnert et al. 2015; Loe et al. 2000; O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005; Rashid and Ibrahim 2008). In our research, we use Hofstede’s (2001) culture typology as a framework to interpret the effect of national culture on individual unethical decisions and identify relevant differences between China and Canada (Vitell et al. 1993).

Hofstede’s Culture Dimensions and Unethical Decision-Making

According to Hofstede (2001), the main culture dimensions found worldwide are power distance (PD), individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance (UA), and Confucian dynamism (CD) (sometimes referred to as long-term orientation). The most well-validated cultural dimensions are PD and individualism (Arnold et al. 2007; Costigan et al. 2006; Curtis et al. 2011; Ralston et al. 2014; Westerman et al. 2007); these dimensions have strong associations with unethical decision-making (Alexandra et al. 2017; Craft 2013; Husted and Allen 2008; Ma 2010; Smith and Hume 2005). The PD dimension refers to the degree of acceptance of the inequality of power distribution in a society (House et al. 2004; Weaver 2001); those who are high-ranking in high-PD societies are more easily able to justify engaging in unethical self-serving behavior than those who are high-ranking in low-PD societies (Cohen et al. 1995; Rosenblatt 2012; Tsui 1996). The Individualism dimension represents a set of personal values or beliefs and prioritizes personal goals when making decisions that affect others (Hofstede 1984; Triandis et al. 1988; Tsui and Windsor 2001); it can result in unethical, self-serving behavior, because those in high-Individualism cultures are more concerned about their own benefits (Ralston et al. 2009).

In addition, high-Masculinity cultures emphasize competitiveness and material success, whereas high-Femininity cultures value relationships and are more concerned with the non-material qualities of life (Hofstede 1984). Members of high-Masculinity societies, especially men (Christie et al. 2003; Taras et al. 2010), exhibit less sensitivity to ethical issues (Husted 2000; Thorne and Saunders 2002); they are more likely to engage in unethical behaviors than members of high-Femininity cultures (Chang and Ding 1995; Vitell et al. 1993).

The dimension of UA is the extent to which a society avoids uncertainty; it represents an intolerance of deviation from policy and formal norms in societal institutions and organizations (Hofstede 1980; Vitell et al. 1993). Some literature suggests that a culture’s emphasis on responsibilities and rules increases as its UA score increases—and that those in low-UA cultures are more likely to engage in unethical decision-making because of poor enforcement of formal standards that guide specific conduct (Ferrell and Skinner 1988). However, other studies argue that high-UA cultures may induce more anxiety (Hofstede 2001), making it difficult for people to recognize moral issues, and therefore, to be less concerned about ethical business practices (Chen 2014; House et al. 2004).

Finally, the dimension of CD, added by Hofstede and Bond (1988), implies a long-term orientation; it has several traditional cultural characteristics that originate in East Asian countries such as China (Huang and Lu 2017; Zhang et al. 2012), but it can be generalized to non-Asian nations (Chung et al. 2008; Schwartz 1992; Tan and Chow 2009). Previous studies of CD and unethical decision-making reveal paradoxical findings (Ang and Leong 2000; Lu et al. 1999; Woodbine 2004; Wu 2001): Some suggest that members of high-CD cultures are less likely to harm the interests of others, because they value group harmony over personal gain (Ding 2006) and work to avoid the shame of hurting others (Lu et al. 1999), but others conclude that the societal CD level is a poor predictor of citizens’ unethical choices (Woodbine 2004).

National Culture Differences Between China and Canada

Table 1 displays the cultural dimension indexes for China and Canada (Hofstede and Hofstede 2005), showing that Chinese and Canadian cultures vary in their dimensions of PD, Individualism, and CD. China scores higher in PD and CD than Canada, whereas Canada has a higher Individualism score than China. The countries have no significant differences in either UA or Masculinity (Hofstede 2001; Triandis 2004).

Our research interest is in the national differences of individuals’ unethical decision-making in the reward distribution process, particularly in a decision context characterized by a trade-off between personal and group benefits. To gain clear insights into the role of national culture, we first focus on the cultural dimensions that differ most between China and Canada. Although Masculinity and UA are associated with unethical decision-making, the differences between their Chinese and Canadian scores are not so pronounced as to make them strong differentiators (see Table 1). We also consider the extent to which the dimensions of PD, Individualism, and CD provide explanatory insights into our power and status variables.

Previous literature on power and culture shows that the essence and goals of power are culturally patterned (Chiu and Hong 2006; Zhong et al. 2006). For example, Torelli and Shavitt (2010) propose that the self-oriented characteristics of power facilitate unethical behavior in high-PD nations because of the acceptance of inequality in power distributions and obedience to authority. Determinants of status also are context dependent; they vary among national cultures (Smith et al. 1996). For example, Torelli et al. (2014) find that the attainment of status through competence is more prevalent in individualist cultures than collectivist cultures.

National cultural dimensions, particularly PD and Individualism, also critically influence people’s perceptions and experiences of power and status and shape their consequent behaviors. Because PD and Individualism scores differ substantially between China and Canada, we adopt the two dimensions as the principal elements of our framework, to interpret the potentially different effects of power and status in the two countries.

Extensive research demonstrates that in societies characterized by high PD, those who have high power believe they are more entitled to privileges or resources than those who have low power (Davis and Ruhe 2003; Resick et al. 2006; Sanyal 2005); they also have less concern for others (Farh et al. 2007; Kirkman et al. 2009). In high-I societies, high status is associated with self-perceptions of personal competence (Torelli et al. 2014), which leads those with high status to believe they are more entitled than those with low status (Feather 1994; Galperin et al. 2011).

China is a society scoring high on PD, low on Individualism, whereas Canada is a society scoring low on PD, high on Individualism. In China, obedience to authority is a dominant norm. Those with high power are expected to be less dependent on subordinates and care less about whether subordinates respect them personally—in part because the positions themselves command respect (Hall 1976; Hofstede 1984). Therefore, in China, conferred status may have less effect than power on high-power people’s unethical decision-making. In addition, status may have a positive effect on unethical decisions, because those with high status are more self-focused and less sensitive to the needs and feelings of those with low status (Galperin et al. 2011). In this sense, the self-focus of the Canadian sample may be an amplifier of the relationship between status and unethical behavior. By integrating social cognitive theory and the cultural characteristics of China and Canada, we predict that Chinese power-holders are more likely to engage in unethical decision-making than their Canadian counterparts; we further predict that Canadians with high status demonstrate relatively greater unethical decision-making intentions compared with their Chinese counterparts.

Hypothesis 4

The positive effect of power on unethical decisions is stronger for Chinese participants than Canadian participants.

Hypothesis 5

The positive effect of status on unethical decisions is stronger for Canadian participants than Chinese participants.

Method

Participants and Design

Participants were university business students in China and Canada who completed a pen-and-paper survey. We developed the survey in English and used it in Canada. We translated the survey into Chinese, in line with established cross-cultural translation procedures (Brislin 1980) and a well-documented and validated precedent in China (Tan and Litschert 1994). We recruited 100 participants in China; their mean age was 20.82 years, with a standard deviation of 1.28 years; 57 (57%) were women, and all of them were undergraduate students. We recruited another 100 participants in Canada, 17 of whom were of Chinese origin, which might have had a confounding effect on our comparison with the Chinese sample. Therefore, we removed these respondents, resulting in a sample of 83 responses. The mean age of the Canadian participants was 20.60 years, with a standard deviation of 3.95 years; 41 were women, and 72 were undergraduate students. The study used of a 2 (high-power vs. low-power) × 2 (high-status vs. low-status) between-subjects design.

Procedure

Participants volunteered to join the study and were invited to a quiet location to complete the survey. We randomly assigned them to one of four conditions. According to role theory (Biddle 1979; McAllister et al. 2007), role priming has important effects on people’s decisions and behavior. We used role-playing materials to manipulate power and status (Bendahan et al. 2015; Blader and Chen 2012). Specifically, we asked each participant to imagine having the role of workgroup supervisor. We then asked them to allocate bonuses for their workgroup by choosing an option from a list of choices (Bendahan et al. 2015). After the participants completed the study, we paid each Canadian subject CDN$3 and rewarded each Chinese subject with a gift valued at about ¥10 RMB.

Measures

Independent Variables

We manipulated power according to (1) number of subordinates, (2) degree of resource control, and (3) discretion over reward distributions, according to the prior validated power manipulation method (Bendahan et al. 2015; Blader and Chen 2012). We provided participants with the information below. The manipulated information is in bold, with the information for the low power condition in parentheses.

You have been appointed to be the supervisor of your workgroup. You have 3 (1) subordinates. You have control over an unusually large amount (a relatively meager amount) of resources, compared with your peers who head other workgroups. After completing the task, you will have 4 (3) distribution options for bonus allocation.

We manipulated status according to workgroup evaluation scores and status level (Blader and Chen 2012; Tyler and Blader 2002) and provided the following information. The manipulated information is in bold, with the low status information in parentheses.

The HR manager interviews your subordinates to gauge their experience and have them assess your work. Your average score was 6.5 (2.5), out of a possible 7. The subordinates in your workgroup think of you as quite a high-status (low-status) person. They really hold you in high (low) regard, and you have a great deal of (very little) esteem and respect from them.

To verify the success of our experimental manipulations, we asked participants to respond to a series of manipulation check questions at the end of the survey. To check power (Blader and Chen 2012), we asked: “How much power did the role have as the supervisor of the workgroup?” and “Did the role (supervisor) have control over a lot of resources?” (China alpha = .69, Canada alpha = .68). To check status (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2008), we asked: “How much esteem or respect did the subordinates on the workgroup have for the role (supervisor)?” and “To what extent did the subordinates on the workgroup consider the role (supervisor) as a high status person?” (China alpha = .81, Canada alpha = .91). Participants answered all questions on a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (“very little”) to 7 (“a great deal”).

Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable was a participant’s unethical decision, which we operationalized through the choice of distribution options in the bonus allocation task. In the task, participants could select from three options: slight premium, equality, or unethical (Bendahan et al. 2015). We coded unethical decisions as a dummy variable, with 0 indicating “not unethical,” and 1 indicating “unethical.”

Table 2 provides a detailed illustration of the options. Option A gave the supervisors a slightly higher bonus than their subordinate(s). The higher bonus served as a premium for being a supervisor. Option B was the equality choice; it allocated equal bonuses for the supervisor and subordinate(s). Options C and D were the unethical choices, which we designed using a constant injury index (i.e., how much injury the individual participant’s decision inflicted on the group) that measured the individual participant’s personal gains and the group’s losses relative to option A. Using the Canadian participants as an example, in unethical option C, the supervisor gained $50 ($270–$220) over option A, whereas the group lost $60 ($190–$130). In unethical option D, the supervisor gained $150 ($370–$220) and the group lost $180 (which both reduced to 5:6).

Control Variables

We recorded participants’ age, gender, and, in Canada, their ethnic backgrounds at the end of the survey. Prior research implies that need for power is an important personality trait variable, highly related to unethical behavior such as corruption (McClelland 1975; Pearce et al. 2008; Pendse 2012), so we used a 3-item scale to measure the degree of individual participants’ need for power. A sample item is “I would want to be in control” (China alpha = .61, Canada alpha = .62).

Results

Manipulation Checks

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that both the power and status manipulations were successful. Participants assigned to the high-power conditions indicated that the role had more power (China: M = 4.17, SD = 1.33; Canada: M = 5.71, SD = .75) compared with those assigned to low-power conditions (China: M = 3.02, SD = 1.42; Canada: M = 3.86, SD = 1.37; China: F[1, 96] = 17.31, p < .001; η2 = .15, Canada: F[1, 79] = 63.82, p < .001, η2 = .44). In addition, participants in the high-status condition tended to have more status (China: M = 4.35, SD = .20; Canada: M = 5.93, SD = .18) than participants in the low-status condition (China: M = 3.65, SD = .20; Canada: M = 2.59, SD = .17; China: F[1, 96] = 5.97, p < .05, η2 = .06; Canada: F[1, 79] = 192.38, p < .001, η2 = .71).

Descriptive Analysis

Table 3 presents the summary descriptive statistics and correlations for Chinese and Canadian subjects. Preliminary analyses showed that power was positively related to unethical decisions in both China and Canada: Chinese participants showed a positive correlation between need for power and unethical decisions, and Canadian participants showed a positive correlation between status and unethical decisions. Unethical decisions were not correlated with age (r = .07, p = .51), gender (r = .01, p = .96), or, for the Canadian sample, program (r = .01, p = .92).

Hypotheses Tests

Main Effects of Power and Status Within Nations

We used binary logistic regression to predict the effects of power and status on individual participants’ unethical decisions. Table 4 presents the results. Among Chinese participants, power had a significant effect on unethical decisions, in support of H1. However, status had neither significant effects nor interactions. Therefore, H2 and H3 are not supported in the Chinese context.

Among Canadian participants, there was a significant main effect of power. Status related positively to unethical decisions, and the effect of power on unethical decisions varied as a function of status. Specifically, the tendency to make unethical decisions was stronger for participants in the high-status/high-power condition than the high-status/low-power condition (χ2[1] = 5.09, p < .05). No significant power effect emerged in the low-status condition (χ2[1] = .17, p = .68 > .10). Thus, the interaction of power and status produced a significant effect on unethical decisions; the positive effect of power on unethical decisions was stronger among participants whose status was high rather than low (b = 4.17, p < .05). Therefore, H1, H2, and H3 are supported in the Canadian context.

Comparison of China and Canada

Figure 2 presents Chinese and Canadian participants’ unethical propensities across power and status conditions. Chinese holders of high power were more likely to engage in unethical decision-making than their low-power counterparts (low 8%; high 42%; χ2[1] = 15.41, p < .001). Canadian holders of high power were also more likely to engage in unethical decision-making (low 10%; high 30%; χ2[1] = 5.20, p < .05). Therefore, H4 is not supported. Yet Canadian holders of high status were more likely to engage in unethical decision-making than their low-status counterparts (low 12%; high 27%; χ2[1] = 2.97, p < .10), whereas status was not significantly associated with Chinese participants’ unethical decisions (low 24%; high 26%; χ2[1] = .05, p =.82). Therefore, H5 is supported.

In addition, Chinese high power holders’ unethical decisions did not vary significantly between the high and low status conditions (high power/status 24%; high power/low status 18%; χ2[1] = .54, p = .46). Canadian high-power holders made significantly more unethical decisions when they also held high status (high power/status 26%; high power/low status 5%; χ2[1] = 7.44, p < .05). This further evidence affirms that status has a moderating effect on power and unethical decisions in Canada but not in China.

Choice Rationales

To explore the proposed rationale that national differences determine relationships among power, status, and unethical decisions, we asked participants to report their reasons for making unethical decisions. We then conducted a choice rationale analysis of their responses.

Procedures

Chinese participants’ rationales were provided in Mandarin, so two Chinese postgraduate students, fluent in both Mandarin and English, performed a translation/back-translation procedure. With these translations, we applied a four-step systematic coding method (Srnka and Koeszegi 2007; van Someren et al. 1994): (1) devising the coding scheme, (2) recruiting the coder, (3) starting the coding process, and (4) measuring inter-coder reliability. Thus, we used a deductive and inductive process to form the codes (Srnka and Koeszegi 2007). Initially, we deduced three basic coding categories from our theoretical framework (Berger et al. 1972; Galperin et al. 2011; Keltner et al. 2003) and various literature pertaining to motives for unethical decision-making:

-

(1)

Power: respondents used their manipulated power superiorities (e.g., asymmetrical discretions, resources) or the subjective deservingness of being in a powerful role as rationales for their unethical decisions.

-

(2)

Status: participants rationalized unethical decisions through the status associated with their manipulated privileged position (e.g., highly regarded by others) in the group or subjective entitlement as the result of their presumed competency (e.g., excellent performance, or ability).

-

(3)

Other: participants could also offer open-ended responses to identify other rationales. We offered this undefined category to accommodate themes that could emerge from the data and be identified during coding.

Next, we undertook an inductive process to develop and complete formal codes. We conducted preliminary coding of the qualitative data and defined seven distinct codes (Srnka and Koeszegi 2007), allowing for the elaboration and specification of the power and status categories and the identification of several new rationales. Table 5 presents definitions and descriptions for each code.

We asked two Canadian doctoral students, blind to our research objectives, to apply this coding system. In training these coders, we gave them examples to help them understand the code definitions. The coders then began to code participants’ reasons, using a standard process. The Cohen’s kappa (Cohen 1960; Srnka et al. 2007) coefficient of inter-coder agreement was .88, indicating that their agreement was high and reliable.

Findings and Discussions

Approximately, 90% of the participants (21 in the Chinese sample, 16 in the Canadian sample) provided rationales for their unethical decisions. A total of 47 codes resulted from these given rationales (some participants indicated more than one reason for their choices). Figure 3 depicts the code frequencies of Chinese and Canadian participants’ rationales, revealing the predominant reasons offered for unethical decisions.

With regard to the total number of codes, for Chinese participants, position difference (46%) and power empowerment (27%) appeared most frequently. In Canada, the most frequent rationales for unethical decisions were work effort (38%) and skill (24%). We combined the two power-related codes into one code, and similarly combined the two performance-related codes into one code, then ran Chi square tests. The Chinese participants mentioned position or power privileges more frequently than their Canadian counterparts, (China 72%; Canada 25%’ χ2[1] = 8.67, p < .05). Compared with their Chinese counterparts, Canadians were more likely to interpret their deservingness for greater outcomes as related to their burden of more work or skills (China 12%; Canada 75%; χ2[1] = 16.69, p < .001).

To interpret the positive effects of power and status on unethical decision-making through individual members’ superior positions in the social group, we further explore the rationales of participants subjected to the high-power or high-status manipulations. In the high-power condition, Chinese participants were more likely than Canadian participants to rationalize taking advantage of their discretionary power to gain personal benefit by citing position differences or superiority. In Canada, participants rationalized that their more powerful roles came with the cost of greater work, so supervisory responsibilities should be accounted for in the reward distribution. These findings suggest that though power has positive effects on both Chinese and Canadian participants’ unethical behaviors, the rationales for their unethical decisions differ between China and Canada.

Similarly, we compared Chinese and Canadian participants’ rationales in high-status conditions. Neither group substantially identified status superiority as a reason for unethical decisions (China 4%; Canada 5%). Chinese high-status holders frequently referenced power empowerment (50%), whereas Canadian high-status participants frequently mentioned skill (45%). These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies of subjective perceptions of status (Kuwabara et al. 2016; Torelli et al. 2014). In high-achievement cultures, status usually is determined by people’s recent accomplishments, whereas in cultures that tend more to ascription, status differences are considered incumbent to formal hierarchy positions (Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner 2011). These differences in the basis of status judgments can explain the effects of status in Canada but not in China.

In addition, participants in both China and Canada mentioned negative emotions produced from status deficiency as rationales for unethical decision-making (China 8%; Canada 10%). Although we did not predict a relationship between low status and unethical decision-making in our theoretical model, this finding is consistent with the previous literature on power and status, which has proposed that lack of status can be experienced as a threat and may accelerate the positive effect of power on self-benefit intentions, even at the cost of others (Williams 2014). All mentions of personality-based rationales occurred in the high-power and high-status conditions, consistent with previous findings that power enables people to be “who they are” (Chen et al. 2001). These codes corresponded to the main reasons for participants’ unethical decisions and provided greater insight into the roles of power, status, and national culture in the process of unethical decision-making.

General Discussion

Our goal in this research was to determine why high-position members of organizations make unethical decisions. To gain a better understanding of unethical behavior, we drew on social cognitive theory to develop a conceptual model of unethical decision-making and explore the roles of social hierarchy and culture in the unethical decision-making process. By testing our model with a scenario experiment in two distinct cultural contexts—China and Canada—we obtained meaningful results.

Theoretical Implications

A main contribution of our findings is that we provide greater understanding of unethical decision-making. Most previous literature attributes unethical decisions to psychological factors such as cognitive moral development (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). A few studies have noted the role of hierarchical characteristics in explaining unethical decisions. For example, Galperin et al. (2011) propose a theoretical model that predicts a positive association between social hierarchy and unethical decision-making. However, their model remains largely untested and lacks empirical support. Our study extends Galperin et al.’s (2011) work by providing empirical evidence for the impacts of these hierarchical factors on high-ranking members’ unethical decisions. Our findings make important contributions to the debate on the relationship between hierarchy and unethical decision-making (Aguilera and Vadera 2008; Kulik 2005; Pearce et al. 2008). We suggest that power approach theory explains the positive relationship between power and unethical decisions, and this effect holds in both China and Canada. Whereas status characteristic theory explains the expected positive effects of status, it holds only in Canadian samples. The results indicate that the association between status and unethical decision-making needs further exploration; in particular, it should be considered according to cultural and societal contexts.

Our second contribution relates to the distinction between power and status. Some scholars argue that the conflation of power and status in prior literature has led to paradoxical findings for the impacts of organizational hierarchy on unethical decision-making processes (Li et al. 2016). Consequently, there is a need to distinguish these two constructs when researching social hierarchy (Blader and Chen 2012; Magee and Galinsky 2008). Despite growing interest in identifying differences between power and status, little attention has been devoted to the potential role of culture and values. Our research addresses this gap by finding that power and status are less distinct in China but more distinct in Canada.

Other studies indicate the culturally dependent attributes of power and status. In particular, Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (2011) propose that status is accorded differently in achievement- and ascription-oriented cultures; previous work on cultural dimensions (e.g., Lee and Peterson 2000) implies that China is a high-ascription culture and Canada is more oriented toward achievement. Consistent with this ascribed-versus-achieved cultural effect, our research affirms that Chinese participants tend to associate status with differences in hierarchical position, whereas Canadian participants tend to rationalize their unethical decisions according to the perception that highly regarded positions entail more work. These findings suggest new routes to investigate power and status effects and point to the importance of cultural context in understanding the difference between power and status.

Practical Implications

Our research has several practical implications for understanding the phenomenon of unethical decision-making in different cultural contexts and for developing effective strategies to reduce unethical behavior in organizations. First, organizations should address the use of discretion by members who are in high-ranking positions, because more discretion provides greater opportunities to engage in unethical decision-making. Notably, this imbalance is present in both China and Canada. By developing clear regulations that address the use of discretion by higher-ranking members, organizations may be able to reduce the incidence of unethical behavior.

Second, our findings provide implications for managers who wish to formulate safeguards against unethical behavior. Organizational members, especially those who occupy high-ranking positions, should understand the critical factors of unethical decision-making processes. In particular, people’s behaviors are influenced by their relative power and status, and their actions might differ according to their national cultures. For example, an emphasis on position-based superiority or performance-based superiority could induce unnecessary entitlements in reward distribution and lead to deviance and unethical decisions. To regulate unethical behavior, managers must understand these antecedents of unethical behavior (Lu et al. 1999).

Third, the cultural differences we find suggest that organizations should adopt different strategies in different societies to discourage unethical behavior by higher-ranking members. For example, status has a positive effect on unethical decision-making in Canada but not in China. Previous research proposes that reminding people of their duties of honor can reduce their subsequent dishonest behavior (Mazar et al. 2008), and our findings suggest that organizations operating in highly individualistic societies should ask higher-ranking members to sign honor codes. In China, the rationales given by participants suggest that in such high-PD environments, individual members’ perceptions of hierarchy superiority likely are based on social roles or positions. Recent literature on status attainment suggests that superior ranks also can be gained and maintained through morality and virtue (Bai 2017). Organizations that operate in high-PD societies thus should guide higher-ranking members’ perceptions of their superior positions and their cognizance of their own behaviors and the effects on others.

Limitations and Research Directions

Several limitations to our study should be addressed. First, we used student samples to test our model of unethical decision-making. Although it is not unusual in experimental research to rely on student samples (Blader and Chen 2012; Bendahan et al. 2015; Köbis et al. 2017), their limited working experience could influence their ethical decisions (Fischer and Smith 2003; Lehnert et al. 2015; Pflugrath et al. 2007). Therefore, our study should be replicated in organizational environments. All participants in our study were business students though, so our findings remain relevant, in terms of the potential behaviors of future business managers. To improve the predictive power of our insights, longitudinal research that tracks decision makers over time could shed light on how they respond to external influences and whether and how their attitudes change over time (Tan and Tan 2005).

Second, our study relied on scenario surveys that did not involve real outcomes. Although scenario studies are commonly accepted in empirical research, multiple methods should be used, including an experimental approach to simulate the experience. Researchers could conduct laboratory studies in which participants engage in group activities, to test the relationships among power, status, and unethical decisions in more realistic environments.

Third, we based our predictions about national culture differences between China and Canada on Hofstede’s (1980) model of culture dimensions. Although we did not measure the Individualism or PD orientations of our Chinese and Canadian participants, decades of empirical research have validated Hofstede’s culture dimensions (Christie et al. 2003; Taras et al. 2010). Moreover, several studies have provided converging evidence for the emphasis on cultural dimensions in China and Canada. For example, Cui et al. (2008) demonstrates that Canadian participants have significantly higher average scores on the Individualism dimension than Chinese participants. Maznevski et al. (2002) find that the pattern of national average scores on a hierarchy dimension is consistent with Hofstede’s PD dimension. Research could address this issue by controlling for divergent cultural orientations within nations (Fok et al. 2016).

Fourth, though our study focuses on unethical decisions that have harmful effects on organizations or organizations’ group members, some studies note potentially positive outcomes of social hierarchy for organizations (Lee et al. 2019; van Dijke et al. 2018). Future studies could use other theories or disciplines to explain the positive relationship between social hierarchy and pro-organizational (but unethical) decision-making.

Fifth, we consider the effects of status on unethical behaviors according to a competence-centered perspective, but status also may be grounded in virtue (Bai 2017) and have positive outcomes for prosocial behaviors, such as generosity or perspective taking (Blader and Chen 2012; Blader et al. 2016). These findings indicate that there may be conditions that mitigate—or even reverse—the positive association between status and unethical decision-making. Researchers could study these potentially competing effects and explore how the double-edged sword of status shapes organizational contexts.

Conclusion

By drawing on social cognitive theory, we confirm that power and status have differing effects on unethical decision-making in Chinese and Canadian contexts. Power has a universally positive effect on unethical decision-making. Status has a positive effect on the unethical decisions of Canadian participants but not Chinese participants. It also affects the relationship between power and the unethical decisions of Canadian students. Accordingly, our theoretical development and findings with regard to power, status, culture, and unethical decision-making expands the literature on social hierarchy and unethical behavior and helps clarify the factors that drive people to engage in unethical decision-making.

References

Aguilera, R. V., & Vadera, A. K. (2008). The dark side of authority: Antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of organizational corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(4), 431–449.

Alexandra, V., Torres, M. M., Kovbasyuk, O., Addo, T. B., & Ferreira, M. C. (2017). The relationship between social cynicism belief, social dominance orientation, and the perception of unethical behavior: A cross-cultural examination in Russia, Portugal, and the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(3), 545–562.

Anderson, C., & Brion, S. (2014). Perspectives on power in organizations. Social Science Electronic Publishing, 1(1), 67–97.

Anderson, C., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009). The pursuit of status in social groups. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(5), 295–298.

Ang, S. H., & Leong, S. M. (2000). Out of the mouths of babes: Business ethics and youths in Asia. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(2), 129–144.

Anicich, E. M., Fast, N. J., Halevy, N., & Galinsky, A. D. (2015). When the bases of social hierarchy collide: Power without status drives interpersonal conflict. Organization Science, 27(1), 123–140.

Arnold, D. F., Bernardi, R. A., Neidermeyer, P. E., & Schmee, J. (2007). The effect of country and culture on perceptions of appropriate ethical actions prescribed by codes of conduct: A western European perspective among accountants. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(4), 327–340.

Bai, F. (2017). Beyond dominance and competence: A moral virtue theory of status attainment. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(3), 203–227.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development: Theory, research and applications (Vol. 1, pp. 71–129). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Beekun, R. I., Hamdy, R., Westerman, J. W., & HassabElnaby, H. R. (2008). An exploration of ethical decision-making processes in the United States and Egypt. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(3), 587–605.

Bell, C. M., & Hughes-Jones, J. (2007). Power, self-regulation, and the moralization of behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(3), 503–514.

Bendahan, S., Zehnder, C., Pralong, F. P., & Antonakis, J. (2015). Leader corruption depends on power and testosterone. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 101–122.

Berger, J., Cohen, B. P., & Zelditch, M., Jr. (1972). Status characteristics and social interaction. American Sociological Review, 37(3), 241–255.

Berger, J., Conner, T. L., & Fisek, M. H. (1974). Expectation states theory: A theoretical research program. Cambridge: Winthrop.

Biddle, B. J. (1979). Role theory: Expectations, identities, and behaviors. New York: Academic Press.

Blader, S. L., & Chen, Y.-R. (2012). Differentiating the effects of status and power: A justice perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(5), 995–1014.

Blader, S. L., Shirako, A., & Chen, Y. R. (2016). Looking out from the top: Differential effects of status and power on perspective taking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(6), 723–737.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross cultural psychology (pp. 398–444). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Chang, K., & Ding, C. G. (1995). The influence of culture on industrial buying selection criteria in Taiwan and mainland China. Industrial Marketing Management, 24(4), 277–284.

Chen, C. W. (2014). Are workers more likely to be deviant than managers? A cross-national analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(2), 221–233.

Chen, S., Lee-Chai, A. Y., & Bargh, J. A. (2001). Relationship orientation as a moderator of the effects of social power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 173–187.

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Kingstone, A., Foulsham, T., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103–125.

Chiu, C.-Y., & Hong, Y.-Y. (2006). Social psychology of culture. New York: Psychology Press.

Christie, P. M. J., Kwon, I. W. G., Stoeberl, P. A., & Baumhart, R. (2003). A cross-cultural comparison of ethical attitudes of business managers: India, Korea and the United states. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(3), 263–287.

Chung, K. Y., Eichenseher, J. W., & Taniguchi, T. (2008). Ethical perceptions of business students: Differences between East Asia and the USA and among “Confucian” cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1–2), 121–132.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46.

Cohen, J. R., Pant, L., & Sharp, D. (1995). An exploratory examination of international differences in auditors’ ethical perceptions. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 7(1), 37–64.

Costigan, R. D., Insinga, R. C., Berman, J. J., Ilter, S. S., Kranas, G., & Kureshov, V. A. (2006). The effect of employee trust of the supervisor on enterprising behavior: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(2), 273–291.

Craft, J. L. (2013). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 221–259.

Cui, G., Chan, T. S., & Joy, A. (2008). Consumers’ attitudes toward marketing: A cross-cultural study of China and Canada. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 20(3–4), 81–93.

Curtis, M. B., Conover, T. L., & Chui, L. C. (2011). A cross-cultural study of the influence of country of origin, justice, power distance, and gender on ethical decision making. Journal of International Accounting Research, 11(1), 5–34.

Davis, J. H., & Ruhe, J. A. (2003). Perceptions of country corruption: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(4), 275–288.

De Cremer, D., & Van Dijk, E. (2005). When and why leaders put themselves first: Leader behaviour in resource allocations as a function of feeling entitled. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(4), 553–563.

Ding, D. D. (2006). An indirect style in business communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 20(1), 87–100.

Dubois, D., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2015). Social class, power, and selfishness: When and why upper and lower class individuals behave unethically. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(3), 436–449.

Eisenbeiß, S. A., & Brodbeck, F. (2014). Ethical and unethical leadership: A cross-cultural and cross-sectoral analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(2), 343–359.

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729.

Fast, N. J., Halevy, N., & Galinsky, A. D. (2012). The destructive nature of power without status. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 391–394.

Feather, N. T. (1994). Attitudes toward high achievers and reactions to their fall: Theory and research concerning tall poppies. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 26, pp. 1–73). Orlando: Academic.

Ferrell, O. C., & Skinner, S. J. (1988). Ethical behavior and bureaucratic structure in marketing research organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(1), 103–109.

Fida, R., Paciello, M., Tramontano, C., Fontaine, R. G., Barbaranelli, C., & Farnese, M. L. (2015). An integrative approach to understanding counterproductive work behavior: The roles of stressors, negative emotions, and moral disengagement. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 131–144.

Fischer, R., & Smith, P. B. (2003). Reward allocation and culture: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(3), 251–268.

Fiske, S. T. (2010). Interpersonal stratification: Status, power, and subordination. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 941–982). Hoboken: Wiley.

Fiske, S. T., & Berdahl, J. (2007). Social power. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (Vol. 2, pp. 678–692). New York: Guilford.

Fok, L. Y., Payne, D. M., & Corey, C. M. (2016). Cultural values, utilitarian orientation, and ethical decision making: A comparison of US and Puerto Rican professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(2), 263–279.

Fragale, A. R., Overbeck, J. R., & Neale, M. A. (2011). Resources versus respect: Social judgments based on targets’ power and status positions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(4), 767–775.

Galperin, B. L., Bennett, R. J., & Aquino, K. (2011). Status differentiation and the protean self: A social-cognitive model of unethical behavior in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 407–424.

Ge, L., & Thomas, S. (2008). A cross-cultural comparison of the deliberative reasoning of Canadian and Chinese accounting students. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(1), 189–211.

Gino, F., Schweitzer, M. E., Mead, N. L., & Ariely, D. (2011). Unable to resist temptation: How self-control depletion promotes unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 191–203.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York: Doubleday.

Hays, N. A., & Blader, S. L. (2017). To give or not to give? Interactive effects of status and legitimacy on generosity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(1), 17–38.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1), 42–63.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1(2), 81–99.

Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1988). The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 5–21.

Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Huang, C. C., & Lu, L. C. (2017). Examining the roles of collectivism, attitude toward business, and religious beliefs on consumer ethics in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(3), 505–514.

Husted, B. W. (2000). The impact of national culture on software piracy. Journal of Business Ethics, 26(3), 197–211.

Husted, B. W., & Allen, D. B. (2008). Toward a model of cross-cultural business ethics: The impact of individualism and collectivism on the ethical decision-making process. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(2), 293–305.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Kafashan, S., Sparks, A., Griskevicius, V., & Barclay, P. (2014). Prosocial behavior and social status. In J. Cheng, J. Tracy, & C. Anderson (Eds.), The psychology of social status (pp. 139–158). New York: Springer.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284.

Kilduff, G. J., & Galinsky, A. D. (2013). From the ephemeral to the enduring: How approach-oriented mindsets lead to greater status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(5), 816–831.

Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J. L., Chen, Z. X., & Lowe, K. B. (2009). Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 744–764.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31.

Köbis, N. C., van Prooijen, J. W., Righetti, F., & Van Lange, P. A. (2017). The road to bribery and corruption: Slippery slope or steep cliff? Psychological Science, 28(3), 297–306.

Kulik, B. W. (2005). Agency theory, reasoning and culture at Enron: In search of a solution. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(4), 347–360.

Kuwabara, K., Yu, S., Lee, A. J., & Galinsky, A. D. (2016). Status decreases dominance in the West but increases dominance in the East. Psychological Science, 27(2), 127–137.

Lammers, J., Galinsky, A. D., Gordijn, E. H., & Otten, S. (2012). Power increases social distance. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(3), 282–290.

Lee, S. M., & Peterson, S. J. (2000). Culture, entrepreneurial orientation, and global competitiveness. Journal of World Business, 35(4), 401–416.

Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2019). Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(1), 109–126.

Lehnert, K., Park, Y. H., & Singh, N. (2015). Research note and review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: Boundary conditions and extensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(1), 195–219.

Li, H. J., Chen, Y. R., & Blader, S. L. (2016). Where is context? Advancing status research with a contextual value perspective. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 185–198.

Loe, T. W., Ferrell, L., & Mansfield, P. (2000). A review of empirical studies assessing ethical decision making in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 25(3), 185–204.

Lu, L. C., Rose, G. M., & Blodgett, J. G. (1999). The effects of cultural dimensions on ethical decision making in marketing: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(1), 91–105.

Ma, Z. (2010). The SINS in business negotiations: Explore the cross-cultural differences in business ethics between Canada and China. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(1), 123–135.

Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 351–398.

Magee, J. C., & Smith, P. K. (2013). The social distance theory of power. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 158–186.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

Maznevski, M. L., Gomez, C. B., DiStefano, J. J., Noorderhaven, N. G., & Wu, P. C. (2002). Cultural dimensions at the individual level of analysis: The cultural orientations framework. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 2(3), 275–295.

McAllister, D. J., Kamdar, D., Morrison, E. W., & Turban, D. B. (2007). Disentangling role perceptions: How perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1200–1211.

McClelland, D. C. (1975). Power: The inner experience. New York: Irvington-Halsted-Wiley.

O’Fallon, M. J., & Butterfield, K. D. (2005). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 1996–2003. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(4), 375–413.

Pearce, C. L., Manz, C. C., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (2008). The roles of vertical and shared leadership in the enactment of executive corruption: Implications for research and practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(3), 353–359.

Pendse, S. G. (2012). Ethical hazards: A motive, means, and opportunity approach to curbing corporate unethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 265–279.

Pflugrath, G., Martinov-Bennie, N., & Chen, L. (2007). The impact of codes of ethics and experience on auditor judgments. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(6), 566–589.

Piazza, A., & Castellucci, F. (2014). Status in organization and management theory. Journal of Management, 40(1), 287–315.

Piff, P. K., Stancato, D. M., Côté, S., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Keltner, D. (2012). Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(11), 4086–4091.

Ralston, D. A., Egri, C. P., de la Garza Carranza, M. T., Ramburuth, P., Terpstra-Tong, J., Pekerti, A. A., et al. (2009). Ethical preferences for influencing superiors: A 41-society study. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(6), 1022–1045.

Ralston, D. A., Egri, C. P., Furrer, O., Kuo, M. H., Li, Y., Wangenheim, F., et al. (2014). Societal-level versus individual-level predictions of ethical behavior: A 48-society study of collectivism and individualism. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(2), 283–306.

Rashid, M. Z., & Ibrahim, S. (2008). The effect of culture and religiosity on business ethics: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 907–917.

Resick, C. J., Hanges, P. J., Dickson, M. W., & Mitchelson, J. K. (2006). A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(4), 345–359.

Rosenblatt, V. (2012). Hierarchies, power inequalities, and organizational corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(2), 237–251.

Rus, D., Van Knippenberg, D., & Wisse, B. (2010). Leader power and leader self-serving behavior: The role of effective leadership beliefs and performance information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), 922–933.

Rus, D., van Knippenberg, D., & Wisse, B. (2012). Leader power and self-serving behavior: The moderating role of accountability. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 13–26.

Sanyal, R. (2005). Determinants of bribery in international business: The cultural and economic factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(1–2), 139–145.

Schwartz, S. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Orlando, FL: Academic.

Sims, R. R., & Brinkmann, J. (2003). Enron ethics (or: Culture matters more than codes). Journal of Business Ethics, 45(3), 243–256.

Smith, A., & Hume, E. C. (2005). Linking culture and ethics: A comparison of accountants’ ethical belief systems in the individualism/collectivism and power distance contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(3), 209–220.

Smith, P. B., Dugan, S., & Trompenaars, F. (1996). National culture and the values of organizational employees: A dimensional analysis across 43 nations. Behavior Analyst, 20(2), 109–119.

Srnka, K. J., & Koeszegi, S. T. (2007). From words to numbers: How to transform qualitative data into meaningful quantitative results. Schmalenbach Business Review, 59(1), 29–57.

Srnka, K. J., Gegez, A. E., & Arzova, S. B. (2007). Why is it (un-)ethical? Comparing potential European partners: A western Christian and an eastern Islamic country—On arguments used in explaining ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(2), 101–118.

Sturm, R. E., & Antonakis, J. (2015). Interpersonal power: A review, critique, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 41(1), 136–163.

Tan, J. (2002). Culture, nation, and entrepreneurial strategic orientations: Implications for an emerging economy. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 26(4), 95–111.

Tan, J., & Chow, H. S. (2009). Isolating cultural and national influence on value and ethics: A test of competing hypotheses. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 197–210.

Tan, J., & Litschert, R. S. (1994). Environment-strategy relationship and its performance implications: An empirical study of Chinese electronics industry. Strategic Management Journal, 15(1), 1–20.

Tan, J., & Tan, D. (2005). Environment–strategy coevolution and coalignment: A staged-model of Chinese SOEs under transition. Strategic Management Journal, 26(2), 141–157.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61(1), 37–68.

Taras, V., Kirkman, B. L., & Steel, P. (2010). Examining the impact of culture’s consequences: A three-decade, multilevel, meta-analytic review of Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(3), 405–439.

Thorne, L., & Saunders, S. B. (2002). The socio-cultural embeddedness of individuals’ ethical reasoning in organizations (cross-cultural ethics). Journal of Business Ethics, 35(1), 1–14.

Torelli, C. J., & Shavitt, S. (2010). Culture and concepts of power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(4), 703–723.

Torelli, C. J., Leslie, L. M., Stoner, J. L., & Puente, R. (2014). Cultural determinants of status: Implications for workplace evaluations and behaviors. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123(1), 34–48.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Triandis, H. C. (2004). The many dimensions of culture. The Academy of Management Executive, 18(1), 88–93.

Triandis, H. C., Bontempo, R., Villareal, M. J., Asai, M., & Lucca, N. (1988). Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(2), 323–338.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (2011). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global business. Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey International.

Tsui, J. S. L. (1996). Auditors’ ethical reasoning: Some audit conflict and cross cultural evidence. International Journal of Accounting, 31(1), 121–133.

Tsui, J., & Windsor, C. (2001). Some cross-cultural evidence on ethical reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 143–150.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2002). The influence of status judgments in hierarchical groups: Comparing autonomous and comparative judgments about status. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89(1), 813–838.

van Dijke, M., De Cremer, D., Langendijk, G., & Anderson, C. (2018). Ranking low, feeling high: How hierarchical position and experienced power promote prosocial behavior in response to procedural justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(2), 164–181.

Van Someren, M. W., Barnard, Y. F., & Sandberg, J. A. C. (1994). The think aloud method: A practical guide to modeling cognitive processes. Information Processing and Management, 31(6), 906–907.

Vitell, S. J., Nwachukwu, S. L., & Barnes, J. H. (1993). The effects of culture on ethical decision-making: An application of Hofstede’s typology. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(10), 753–760.

Weaver, G. R. (2001). Ethics programs in global businesses: Culture’s role in managing ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 30(1), 3–15.

Wei, X., Shao, J., Wang, A., & Jiang, N. (2017). Antecedents and consequences of organizational member status. Advances in Psychological Science, 25(11), 1972–1981.

Westerman, J. W., Beekun, R. I., Stedham, Y., & Yamamura, J. (2007). Peers versus national culture: An analysis of antecedents to ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(3), 239–252.

Williams, M. J. (2014). Serving the self from the seat of power: Goals and threats predict leaders’ self-interested behavior. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1365–1395.

Woodbine, G. F. (2004). Moral choice and the declining influence of traditional value orientations within the financial sector of a rapidly developing region of the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Business Ethics, 55(1), 43–60.

Wu, C. (2001). The study of global business ethics of Taiwanese enterprises in East Asia: Identifying Taiwanese enterprises in mainland China, Vietnam, and Indonesia as targets. Journal of Business Ethics, 33(2), 151–165.

Zhang, S., Liu, W., & Liu, X. (2012). Investigating the relationship between Protestant work ethic and Confucian dynamism: An empirical test in mainland China. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(2), 243–252.

Zhang, G., Zhong, J., & Ozer, M. (2018). Status threat and ethical leadership: A power-dependence perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3972-5.

Zhong, C. B., Magee, J., Maddux, W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, culture, and (in) action: Considerations in the expression and enactment of power in East Asian and Western society. In Y. Chen (Ed.), Research on managing groups and teams: National culture and groups (Vol. 9, pp. 53–73). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 71472131, 71732005, 71271219, 71771219, 71602080, 71790615), and by Central South University (2015zzts009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

We certify that all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approvals have been obtained from the Human Participants Review Sub-Committee.

Informed Consent

We further certify that informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Chen, S., Bell, C. et al. How Do Power and Status Differ in Predicting Unethical Decisions? A Cross-National Comparison of China and Canada. J Bus Ethics 167, 745–760 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04150-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04150-7