Abstract

Ethical leadership research has primarily relied on social learning and social exchange theories. Although these theories have been generative, additional theoretical perspectives hold the potential to broaden scholars’ understanding of ethical leadership’s effects. In this paper, we examine moral typecasting theory and its unique implications for followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior. Across two studies employing both survey-based and experimental methods, we offer support for three key predictions consistent with this theory. First, the effect of ethical leadership on leader-directed citizenship behavior is curvilinear, with followers helping highly ethical and highly unethical leaders the least. Second, this effect only emerges in morally intense contexts. Third, this effect is mediated by the follower’s belief in the potential for prosocial impact. Our findings suggest that a follower’s belief that his or her leader is ethical has meaningful, often counterintuitive effects that are not predicted by dominant theories of ethical leadership. These results highlight the potential importance of moral typecasting theory to better understand the dynamics of ethical leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed growing interest in ethical leadership, defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005, p. 120). Spurred in part by high-profile scandals at Enron, Tyco, WorldCom, and other organizations, scholars have developed new measures of ethical leadership (Brown et al. 2005), conducted comprehensive theoretical reviews (Brown and Mitchell 2010; Brown and Treviño 2006), and examined ethical leadership’s effects on followers’ job satisfaction (Brown et al. 2005), willingness to report problems (Brown et al. 2005), organizational citizenship behavior (Kacmar et al. 2011; Mayer et al. 2009), job performance (Piccolo et al. 2010; Walumbwa et al. 2011), and many other outcomes (Brown et al. 2005; Fehr et al. 2015; Mayer et al. 2012, 2009; Schaubroeck et al. 2012; Walumbwa et al. 2011). All of these studies suggest that ethical leadership leads to beneficial outcomes for followers and organizations (for a review, see Ng and Feldman 2015).

To date, ethical leadership research has predominantly relied on two theoretical frameworks: social learning theory (Bandura 1986) and social exchange theory (Blau 1964). Social learning theory argues that ethical leaders influence their followers by demonstrating the types of activities and behaviors that are expected and rewarded (e.g., treating followers fairly; talking about how to do things the “right” way), encouraging followers to model these behaviors and act in kind (Brown et al. 2005; Mayer et al. 2012; Piccolo et al. 2010; Schaubroeck et al. 2012). Likewise, social exchange theory argues that ethical leaders engender feelings of indebtedness (Kacmar et al. 2011; Mayer et al. 2009) and generate feelings of trust (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009), which in turn spur followers to act prosocially and help the organization. For example, Mayer et al. (2009) suggested that ethical leaders “engender higher levels of trust [than other leaders] and are perceived as fair,” in turn obliging their followers to “reciprocate such treatment by behaving in ways that benefit the entire work group” (p. 3).

One limitation in using social learning and social exchange theories to understand ethical leadership is that these perspectives suggest that ethical leadership is uniformly positive in its effects (Brown and Mitchell 2010). Thus, social learning and social exchange theories preclude the investigation of any negative effects that ethical leadership may cause to either the follower or the leader. Therefore, the hegemony of these theories in the ethical leadership literature is not without risk. We suggest that an overreliance on these theories risks overlooking potential effects of ethical leadership inconsistent with social learning and social exchange perspectives. Moreover, scholars and practitioners have alluded that leadership can be a lonely process (Nohria and Khurana 2010) and ethical leaders in particular might not always enjoy positive outcomes (e.g., Rubin et al. 2010). In this paper, we draw from moral typecasting theory to theorize a set of effects of ethical leadership that is inconsistent with social learning and social exchange theories, yet has lasting implications for leader–employee interactions. In the parlance of Hollenbeck (2008), we aim to shift scholarly consensus on what ethical leadership does and does not do.

Briefly described, moral typecasting theory argues that morality is a fundamentally dyadic phenomenon, involving two distinct parties: a moral agent and a moral patient (Gray and Wegner 2009). Consistent with Aristotle’s classic distinction, moral agents are the causal force through which morally laden deeds occur, whether ethical or unethical, while moral patients are the beneficiaries or victims of the moral agents’ deeds (Gray et al. 2007). Moral agents relieve others’ suffering and fight for justice or, conversely, abuse other people and use them for personal gain. Moral patients are the recipients of these moral or immoral acts. As recent work by Gray and Wegner (2011) and Gray et al. (2012) suggests, moral patients experience positive emotions and outcomes when moral agents commit good deeds, and negative emotions and outcomes when moral agents commit bad deeds. Most relevant to the current research, moral typecasting theory argues that perceptions of moral agency and moral patiency are inversely related. Moral agents tend not to be perceived as moral patients—in other words, they tend to be perceived as relatively invulnerable to the effects of others’ actions (Gray and Wegner 2009; Gray et al. 2012). Similarly, moral patients tend not to be perceived as moral agents—their role in committing moral or immoral deeds tends to be downplayed (Gray and Wegner 2009).

Moral typecasting theory makes three interrelated predictions that are inconsistent with the social learning and social exchange perspectives. We briefly introduce these predictions here and further develop each one of them in the following section of the article. First, moral typecasting theory suggests that followers should help their leaders the least when they are highly unethical or highly ethical. Second, moral typecasting theory suggests that this curvilinear effect should be mediated by perceived prosocial impact—followers’ beliefs that they can have a positive influence on their leaders generally. Finally, moral typecasting theory suggests that these effects should only emerge in morally intense contexts, where followers are most likely to typecast their leaders into the role of moral agent.

To investigate these ideas, we begin with a field study of leader–follower dyads across a broad range of industries. In this field study, we examine the curvilinear effect of ethical leadership on leader-directed citizenship behavior, and the moderating role of moral intensity. In a follow-up experiment, we manipulate ethical leadership and moral intensity, and demonstrate that the moderated curvilinear effect is mediated by followers’ perceptions that they have the potential to help their leaders. Through these studies, we demonstrate that the effects of ethical leadership in organizations are more complex than often assumed. More importantly, ethical leadership may produce less desired effects along with its positive effects for leaders themselves, denying them valuable aid and assistance from their followers. In summary, by integrating moral typecasting theory into the ethical leadership literature, we advance scholars’ understanding of one impact of ethical leadership on leaders themselves, reveal a potential downside of ethical leadership, and highlight new avenues through which practitioners can accentuate the benefits of ethical leadership while mitigating its risks.

Moral Typecasting Theory and Its Implications for Ethical Leadership

A well-accepted tenet of social cognitive psychology is that we do not perceive the people around us in isolation. Rather, our perceptions are guided in part by relational schemas—“cognitive structures representing regularities in patterns of interpersonal relatedness” (Baldwin 1992, p. 461). Through these relational schemas we formulate behavioral scripts, allowing us to predict how social interactions will unfold over time (Baldwin 1992; Fiske 1992; Heider 1958; Wegner and Vallacher 1977). Some relational schemas are symmetrical. For example, we assume that if person A belongs with B, person B also belongs with A. Other relational schemas are asymmetrical. For example, we assume that if person A ostracizes person B, person B will feel ostracized. Moral typecasting theory argues that morally laden social interaction is associated with a distinct asymmetrical relational schema (Gray and Wegner 2009, 2011).

On one side of the relational schema is a moral agent. Whether heroes or villains, moral agents commit moral or immoral deeds, and through this role exert an impact on others. Moral agents are typically viewed in terms of invulnerability, independence, and responsibility (Gray et al. 2007; Waytz et al. 2010). Moral agents are afforded many responsibilities. It is their responsibility to treat others with kindness and compassion—violations of these responsibilities are viewed harshly (Gray and Wegner 2009).

On the other side of the relational schema is a moral patient. Whether beneficiaries or victims, moral patients are the targets of moral or immoral deeds, and through this role experience an array of feelings (e.g., pain and suffering; happiness and relief). Moral patients are typically viewed in terms of vulnerability, dependency, and rights (Gray et al. 2007; Waytz et al. 2010). Whereas moral agents are afforded many responsibilities, moral patients are afforded many rights. Moral patients have the right to be treated to kindness and compassion—violations of these rights are viewed harshly (Gray and Wegner 2009).

Due to the asymmetrical nature of this relational schema, individuals tend to be perceived as either moral agents or moral patients, but not both, at a given time. For example, Gray and Wegner (2009) found that small children are both likely to be perceived as vulnerable moral patients, and to be seen as lacking in responsibility for moral wrongdoing, when compared to adults. In the same way, moral agents tend not to be seen as moral patients. For example, research suggests that people in high power roles are less likely to be perceived as recipients of moral or immoral treatment (Gray and Wegner 2009). Thus, perceptions of moral agency dampen perceptions of moral patiency, and perceptions of moral patiency dampen perceptions of moral agency (Bastian et al. 2011; Gray and Wegner 2011). Empirical research provides support for the inverse relationship between moral agency and moral patiency. In one set of studies, Gray and Wegner (2009) found that participants denied moral patiency to both ethical (e.g., the Dalai Lama, Martin Luther King Jr.) and unethical (e.g., a serial killer) moral agents, perceiving them as more immune to external influence than a morally neutral target.

In short, moral typecasting theory suggests a fundamentally asymmetrical relationship between moral agents and moral patients, providing people with a mental roadmap to facilitate their understanding of dyadic, morally laden interactions. Delving more deeply, moral typecasting theory makes three distinct predictions regarding followers’ interactions with ethical leaders.

Prediction #1: The Effect of Ethical Leadership on Leader-Directed Helping is Curvilinear

Social learning and social exchange theories predict a linear effect of ethical leadership on leader-directed citizenship behavior. We define leader-directed citizenship behavior as a special form of interpersonal citizenship behavior (Settoon and Mossholder 2002) where the follower helps the leader. This helping is general in scope rather than specific to helping the leader to be ethical. According to social learning theory, ethical leaders teach their followers the importance of being helpful. Followers, in turn, display higher levels of citizenship behaviors (e.g., Mayer et al. 2009). Similarly, social exchange theory argues that ethical leadership should increase followers’ feelings of indebtedness, again implying a linear effect on leader-directed citizenship behavior (e.g., Kacmar et al. 2011). In contrast to social learning and social exchange theories, moral typecasting theory argues that reductions in leader-directed citizenship behavior should emerge at both low and high levels of ethical leadership.

Ethical and unethical leaders are both quintessential moral agents. Ethical leaders demonstrate moral agency by setting ethical guidelines (Kalshoven et al. 2011), making honest and fair decisions (Yukl et al. 2013), and being considerate of their followers’ needs (Brown et al. 2005). Unethical leaders demonstrate moral agency by acting in the opposite extreme. They ignore ethical guidelines, treat their followers unfairly, and ignore or contribute to their followers’ suffering (Tepper 2000). When leaders are typecast into the role of moral agents, their followers become moral patients—the recipients of leaders’ moral and immoral actions.Footnote 1

If highly ethical and highly unethical leaders tend to be typecast into the role of moral agent, how might this impact the way followers treat them? An interesting implication of moral typecasting theory is that both of these extremes should discourage followers from helping them in any way (e.g., by staying late to help them meet a deadline). Once typecast into the role of moral agent, followers should perceive ethical and unethical leaders as less susceptible to harm and suffering than other leaders, and therefore less in need of their help to succeed. Although ethical leaders are subject to work demands and therefore may need assistance, followers’ perceptions that a highly ethical or unethical leader is generally immune to harm would preclude them from believing that they can help the leader in his or her various work demands. Follower assistance can extend to all of the leader’s work demands generally (rather than only those demands with ethical implications). Thus, followers might recognize the trials of highly ethical and unethical leaders (e.g., heavy workloads), but presume that any help they might offer would be ineffectual.

Two meta-analyses provide indirect support for this hypothesis. The first finds that perceived victim dependency exhibits a moderate to strong effect on helping behavior, suggesting that people display significantly less helping behavior toward independent others (e.g., moral agents) than toward dependent others (e.g., moral patients; Bornstein 1994). The second finds that men, who are generally perceived as less vulnerable and dependent than women (Broverman et al. 1972), receive less help than women as a result of their gender role (Eagly and Crowley 1986). In a direct test of moral typecasting theory, Gray and Wegner (2009) used a forced-choice paradigm and found that participants were more likely to assign hypothetical pain-inducing pills to ethical or unethical exemplars with high levels of moral agency than to individuals with moderate levels of moral agency (e.g., teachers). Since the imposition of harm on leaders likely constitutes a rare occurrence in most organizations, we propose a more modest hypothesis—that followers will display less citizenship behavior toward highly ethical and highly unethical leaders when compared against leaders who fall between these two extremes.Footnote 2 Integrating moral typecasting theory with the ethical leadership literature, we posit the following hypothesis:

H1

There will be an inverted U-shaped relationship between ethical leadership and followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior.

At first glance, it might appear that our theorizing is inconsistent with extant research which demonstrates a positive, linear relationship between ethical leadership and follower citizenship behavior (e.g., Kacmar et al. 2011; Mayer et al. 2009; Schaubroeck et al. 2012). We note, however, two distinctions between our research and the existing research demonstrating the positive, linear effect. First, we ground our hypotheses in a novel theoretical framework specifically developed from moral psychology (Gray and Wegner 2009, 2011). As discussed above, we believe that drawing theories from the realm of moral psychology is most appropriate for ethical leadership research because of the unique characteristics of human morality (Haidt 2008). In fact, recent puzzling findings on ethical leadership challenge the traditional, linear predictions of social learning and social exchange theories. For example, researchers found that ethical leadership exhibits a curvilinear relationship with follower OCB, such that extremely ethical leaders actually elicit lower levels of follower OCB compared to moderately ethical leaders (Stouten et al. 2013), suggesting a need to consider alternative theoretical perspectives.

Second, our focus is on leader-directed citizenship, whereas prior research has focused on citizenship behavior directed toward individuals other than leaders themselves, or citizenship behavior toward every person in the organization, which may or may not include the leader. Like all people, leaders respond to positive and negative feedback, shifting toward behavior that is rewarded and away from behavior that is punished (Dvir and Shamir 2003, 2007). Therefore, it is important to develop a deeper understanding of how leaders’ ethical behavior might influence how leaders themselves are treated, and the extent to which ethical leadership is rewarded versus punished by the organization and its followers.

Prediction #2: The Curvilinear Effect Only Emerges in Morally Intense Contexts

Our first prediction, if supported, offers initial evidence for the validity of moral typecasting theory within the context of ethical leadership. However, there are reasons to expect that this prediction will be best supported in organizational contexts when ethics are particularly salient. Accordingly, we introduce moral intensity of the organizational context as a key moderating variable.

Jones (1991) defined moral intensity as “a construct that captures the extent of issue-related moral imperative in a situation” (p. 372). Jones (1991) originally theorized moral intensity as having six components (i.e., magnitude of consequences, probability of effect, temporal immediacy, proximity, social consensus, and concentration of effect). Empirical tests of moral intensity, however, have consistently found that the magnitude of consequences, the extent to which an individual believes harm (or benefit) may potentially occur due to a moral act, is the preeminent driver of ethical judgment. For example, after reviewing available studies using the various components of moral intensity, Frey (2000) noted that the magnitude of consequences component was “a particularly powerful determinant of a variety of outcome variables associated with ethical decision making” (p. 188). Magnitude of consequences is usually described as the utility of the moral issue or behavior that a focal person enacts. For example, killing a human being is of higher magnitude of consequence than killing an animal. Upon conducting factor analyses on the components of moral intensity, McMahon and Harvey (2006) found that magnitude of consequences, temporal immediacy, and probability of effect components loaded onto the same factor. They concluded that these three components were actually measuring the same construct, what they termed the “probable magnitude of consequences.” Adding further support to magnitude of consequences being a primary driver of moral intensity, when restricting their measure of moral intensity to one factor, McMahon and Harvey (2006) found that only the three components related to the probable magnitude of consequences were retained. Similarly, Tsalikis, Seaton, and Shepherd (2008) measured the relative importance of the original six moral intensity components using a conjoint experimental design and found the same three components (i.e., magnitude of consequences, temporal immediacy, and probability of effect, or what McMahon and Harvey (2006, 2007) refer to as probable magnitude of consequences) to be the most important components influencing ethical perceptions.

Taken together, these studies suggest that morally intense organizations are likely characterized by high-magnitude moral consequences for employees’ actions. For example, whereas doctors in a hospital can significantly impact the well-being of their patients, restaurant employees’ potential impact on the well-being of their customers is milder (Jones 1991). Research suggests that the moral intensity of different organizations and industries can vary dramatically (Kelley and Elm 2003). For instance, whereas grocery stores and restaurants are characterized by relatively low moral intensity, military bases, sub-prime mortgage lending institutions, hospitals, and fire departments are characterized by relatively high moral intensity.

A central tenet of moral typecasting theory is that the inverse relationship between agency and patiency is more likely to emerge in morally intense contexts. In the absence of moral content, the relationship is greatly reduced. For example, in one study, Gray and Wegner (2009, Study 7) demonstrated that amoral agency (i.e., agency without a moral component) has a very weak effect on perceptions of patiency. This aspect of moral typecasting theory suggests that followers will be much more likely to cast their leaders into the role of moral agents when the moral intensity of the organizational context is high. Support for this argument comes from research on moral awareness. Moral awareness is defined as “a person’s determination that a situation contains moral content and legitimately can be considered from a moral point of view” (Reynolds 2006, p. 233). Research supports the notion that the moral intensity of an action is directly and positively associated with an awareness of its moral content (Butterfield et al. 2000; May and Pauli 2002; Reynolds 2006). Thus, although leaders might act ethically or unethically in contexts of low moral intensity, followers may simply overlook the moral relevance of these behaviors, rendering the predictions of moral typecasting theory invalid due to a lack of salient moral content.

Consider a manager who vocally refuses to bribe a government official when doing business in a foreign country. Followers are more likely to recognize this action as morally relevant when the magnitude of consequences is high (e.g., firm loses $1,000,000 in revenue) rather than low (e.g., firm loses $1000 in revenue; Butterfield et al. 2000; Reynolds 2006). If leaders’ actions are not perceived as morally relevant in contexts of low moral intensity, then followers are unlikely to typecast them as moral agents. The proposed interactive effect of ethical leadership and moral intensity is also consistent with many anecdotal narratives. Whereas ethical business leaders that operate under highly morally intense conditions (e.g., James Burke following the Tylenol crisis; police captains in high-crime areas) frequently garner media attention, ethical business leaders that operate under conditions of low moral intensity are less frequently mentioned. In sum, we suggest that high levels of ethical or unethical leadership should influence leader-directed citizenship behavior when the follower believes that moral intensity is high, but not when it is low. In other words, highly ethical leaders will receive even less help when the follower believes that the moral intensity of the organizational context is high. Based upon this reasoning, we posit that:

H2

Moral intensity of the organizational context will moderate the inverted U-shaped relationship between ethical leadership and followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior, such that the relationship is strongest among leaders in morally intense organizational contexts.

Prediction #3: Potential for Prosocial Impact Mediates the Moderated Curvilinear Effect

Thus far, we have hypothesized a curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and followers’ leader-directed citizenship behaviors, moderated by moral intensity. Given the novelty of these hypotheses, it is important to explore the underlying mechanism of these effects in order to advance our theoretical understanding of ethical leadership and provide further support for the particular utility of moral typecasting theory. Toward this end, we argue that the moderated, curvilinear effect of ethical leadership on leader-directed citizenship will be mediated by followers’ beliefs that they can have a prosocial impact on their leaders.

Prosocial impact refers to “the subjective experience of benefiting others” (Grant and Campbell 2007, p. 667). By examining the perceived potential for prosocial impact, we focus on followers’ beliefs that they could benefit their leaders if they attempted to do so. Consistent with Grant and Campbell’s (2007) definition, we presume that this belief in the potential for benefitting the leader is broad in scope as opposed to relegated to one specific domain (e.g., ethical decision making). We also presume that followers are most likely to help others at work when perceived potential for prosocial impact is high, because such prosocial impact will confer their behavior with meaning. In contrast, employees are less likely to help others when the perceived potential for prosocial impact is low (Grant 2007).

As previously reviewed, both highly ethical leaders and highly unethical leaders should tend to be typecast as moral agents; these leaders are perceived as invulnerable, independent, and in need of little assistance to succeed. When leaders are typecast into this role, followers are unlikely to believe that they can meaningfully impact their leaders’ lives. A follower may feel sorry for a highly ethical or (less likely) a highly unethical leader faced with work-related hardships, but nonetheless fail to assist him or her due to a belief that any attempted assistance would have little effect on the leader’s well-being. Indeed, a recent experimental study reveals that those who do good or evil later appear more powerful (Gray 2010). Anecdotally, it is easier to imagine an ordinary person’s actions having a prosocial impact on an ordinary leader than on ethical exemplars such as Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Johnson and Johnson CEO James Burke, or on unethical exemplars such as Hitler, Mussolini, or Enron CFO Jeffrey Skilling. When followers do not believe that their efforts could exert a meaningful impact on their leaders, they are unlikely to engage in leader-directed citizenship behavior. Consistent with this notion, studies have found that low beliefs regarding one’s ability to have a prosocial impact are associated with reduced effort, persistence, and performance at work (Grant 2008a; Grant et al. 2007). We therefore posit the following:

H3

The curvilinear interactive effect between ethical leadership and moral intensity on leader-directed citizenship behavior is mediated by followers’ perceived potential to have a prosocial impact on their leaders.

Research Overview

We conducted two studies to test our theoretical model. In Study 1, we collected data from leader–follower dyads across a range of industries to test our fundamental arguments—that there will be an inverted U-shaped curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior (Hypothesis 1), moderated by the moral intensity of the organizational context (Hypothesis 2). Although Study 1 was high in external validity, we conducted a follow-up experiment that allowed us to establish causality while maintaining mundane realism (for recent experimental studies on leadership, see De Cremer et al. 2009; Stouten et al. 2013; van Knippenberg and van Knippenberg 2005). In Study 2, we conducted a leader scenario experiment to replicate and build upon the Study 1 findings. In a community sample of working adults, we manipulated both ethical leadership and moral intensity, and examined the interactive effects of these manipulations on a behavioral measure of leader-directed citizenship behavior. Study 2 also examined the mediating effect of perceived potential for prosocial impact toward the leader (Hypothesis 3), providing a complete test of our theoretical model.

Study 1

Participants and Procedure

For our first study, we aimed to collect data from leader–follower dyads across a wide range of industries and organizations with varying moral intensities. Toward this goal, we recruited our participants through the Study Response Project. The Study Response Project is a non-profit research database maintained by a large private university in the United States (see http://www.studyresponse.net for details; for recent examples of studies utilizing the Study Response data collection method for dyadic data, see Barnes et al. 2011; Yam et al. 2016). With the assistance of the Study Response administrators, we first pre-screened potential participants to select those who were working full-time and willing to invite their supervisors to participate in a study on workplace attitudes. Administrators from the Study Response Project then validated all leaders’ email addresses. We did not mention ethical leadership in the pre-screening procedure to minimize self-selection bias.

A total of 229 leader–follower dyads agreed to participate and were sent the surveys. The study was successfully completed by 175 matched dyads, yielding a response rate of 76.4%. The age of the focal employees (64% male; 79.4% White) ranged from 24 to 69 (M = 38.79, SD = 9.12). The age of the supervisors (69.7% male; 80% White) ranged from 24 to 77 (M = 42.57, SD = 9.24). Participants were from a wide array of industries (e.g., IT, sales, legal, tourism). We intentionally recruited participants from multiple industries to enhance the generalizability of our findings and ensure adequate variance in the moral intensities of participants’ organizations. All participants were compensated with $5 at the end of the survey.

Measures

Ethical Leadership

We measured leaders’ ethical behavior by asking their followers to complete Brown et al.’s (2005) ethical leadership scale. This ten item scale is the most widely used in the ethical leadership literature, and includes items that assess leaders’ ethics regarding both their managerial practices and how they behave toward others in general (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; α = 0.91). Recent studies have provided evidence for the scale’s validity across a wide range of settings and samples (e.g., Mayer et al. 2012). All scale items used in this research can be found in Appendix A.

Moral Intensity

Early theorizing on moral intensity proposed a six dimensional framework (Jones 1991). Empirical research, however, has provided mixed support for the six factor structure (Frey 2000). We thus adapted a scale from McMahon and Harvey (2006), which includes items rooted in three dimensions of moral intensity—magnitude of consequences, probability of effect, and temporal immediacy. These three dimensions form a higher-order factor (what McMahon and Harvey refer to as the probable magnitude of consequences) which explained the most variance in the moral intensity construct and has demonstrated good psychometric properties. Consistent with early theorizing on moral intensity (Jones 1991), we altered McMahon and Harvey’s (2006) items to ensure that they could apply equally well to contexts with positive vs. negative moral consequences. Followers were asked to complete this six-item scale measuring their beliefs regarding the moral intensity of their organization (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.85).

To further ensure that we have sufficient variance for moral intensity of the organizational context, we conducted the Shapiro–Wilk test to examine whether this construct is normally distributed. Results revealed that the construct moral intensity is indeed normally distributed (p = 0.22). On a percentage basis, 37.9% of participants reported below the mid-point (i.e., 4.00), whereas 62.1% reported above the mid-point. These results suggest that we have sufficient variance to detect moderation.

Leader-Directed Citizenship Behavior

In this research, our focus is on the helping behavior leaders receive from their followers, otherwise referred to as leader-directed interpersonal citizenship behavior. These behaviors are reported by the leader themselves about each of their followers. To measure this construct, we adapted an eight-item person-focused citizenship behavior scale from Settoon and Mossholder (2002). This person-focused citizenship behavior scale focuses on behaviors that an employee could direct toward a leader regardless of the employee’s task-focused competencies, and is thus well-suited for our diverse sample. Leaders were specifically asked to assess their agreement that the focal follower directs these behaviors toward them (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.90).Footnote 3

Control Variables

Research suggests that leader perceptions are influenced by age (Doherty 1997), gender (Eagly and Chin 2010), and race (Rosette et al. 2008). Similarly, research suggests that leader perceptions and leader-directed behavior are influenced by followers’ familiarity with their leaders and the length of the leader–follower relationship (Dulebohn et al. 2012). To ensure that these factors did not unduly influence our results, we controlled for leaders’ age, gender, and race (leader-reported), as well as the length of the leader–follower relationship and followers’ familiarity with their leaders (follower-reported). For these last two control variables, followers were specifically asked how long they have worked with their current leader (M = 4.34 years; SD = 1.00) and how well they know their leader (1 = not at all, 5 = very well; M = 4.02, SD = 0.73).

Results and Discussion

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the focal variables are presented in Table 1.

We used hierarchical regression analysis to test each of our hypotheses. According to Hypothesis 1, the quadratic ethical leadership term should exert an effect on leader-directed citizenship behavior above and beyond the control variables and the linear ethical leadership term (Cohen et al. 2003). We conducted this analysis in two steps. In Step 1, we entered the control variables and the linear ethical leadership term. In Step 2, we entered the quadratic ethical leadership term. The quadratic term was significant (β = −2.23, p < 0.01; see Table 2), resulting in a significant change in R2 (ΔR2 = 0.08, p < 0.01). This result provided support for Hypothesis 1. Because the coefficient was negative, the results furthermore suggest an inverted, U-shaped curvilinear effect. Followers displayed the least leader-directed citizenship behavior when their leaders displayed high levels of ethical behavior or high levels of unethical behavior.

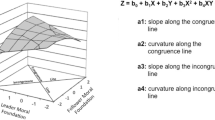

To test Hypothesis 2, we entered moral intensity in Step 3 of the regression model. The addition of moral intensity did not result in a significant change in R2 (ΔR2 = 0.01, p = 0.52). In Step 4, we entered both the linear and quadratic interaction terms into the regression model. The quadratic interaction term was significant (β = −2.43, p < 0.05; see Table 2), resulting in a significant change in R2 (ΔR2 = 0.03, p < 0.05). Again, the negative coefficient provided support for an inverted U-shaped curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and leader-directed citizenship behavior, moderated by moral intensity of the organizational context. We graphed this curvilinear interaction at one standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderator (see Fig. 1). Supporting Hypothesis 2, the decrease in followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior was steepest in morally intense organizational contexts.

Study 1 provides support for our theorized curvilinear model. Results revealed an inverted U-shaped relationship between ethical leadership and followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior. We also found that this curvilinear effect was strongest in morally intense organizational contexts. Although Study 1 provides support for Hypotheses 1 and 2, the mediating processes underlying the effect were not examined. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to make causal inferences. We therefore conducted a second study to test Hypothesis 3 and obtain stronger evidence for causality in our model by employing an experimental design with a behavioral measure of leader-directed citizenship behavior.

Study 2

Study 2 was conducted with three objectives in mind. First, we sought to establish causal inferences by employing an experimental design. Participants were asked to assume the role of a follower in a randomized leader scenario experiment (see Stouten et al. 2013 for a similar leader scenario experiment) in which ethical leadership and moral intensity were both manipulated rather than measured. Second, whereas previous research on citizenship behavior has often assessed self- or other-report citizenship behavior, we employed a behavioral measure of leader-directed citizenship behavior to avoid biases associated with survey-based measures (e.g., Podsakoff et al. 2013). Finally, we sought to examine the role of followers’ perceived potential for prosocial impact as a mediator of the curvilinear interactive effect of ethical leadership and moral intensity on leader-directed citizenship behavior.

Participants and Procedure

Because experiments are often criticized for a lack of generalizability (Highhouse 2009), we sought to maximize the current study’s external validity by recruiting a representative sample of working adults who are familiar with workplace dynamics. We recruited a total of 187 participants (Mage = 36.50; 56.1% female; 75.4% White) from a mid-sized city in the Western United States. The first author and a trained research assistant recruited participants from parks and shopping centers on various days throughout the week (both weekdays and weekends), and at various time throughout the day (both in the morning and in the afternoon) to maximize the representativeness of the sample. The researchers approached participants and advertised the survey as a study of “perceptions of leadership.” Participants were then provided with a description of the study. To avoid demand bias, we did not indicate a focus on ethics, ethical leadership, or helping behavior. All participants completed the study on a voluntary basis. During the recruitment process, we excluded participants who were unemployed or employed part-time to ensure that participants were familiar with leader–follower dynamics in organizational settings. On average, participants reported 15.70 years (SD = 8.08) of full-time work experience across a variety of industries (e.g., IT, sales).

We employed a 3 (ethical leadership vs. control vs. unethical leadership) × 2 (high vs. low moral intensity) between-subjects experiment to test our hypotheses. Participants were presented with a vignette detailing the actions of a leader at a mid-sized research laboratory. Then, participants were instructed to carefully read the vignette and imagine themselves, as vividly as possible, as followers of the leader. After reading the vignette, participants completed a measure of perceived potential for prosocial impact, followed by a behavioral measure of leader-directed citizenship behavior. Finally, participants completed basic demographic information and manipulation check items.

Manipulations and Measures

Ethical Leadership Manipulation

All participants were presented with information about a leader working at a mid-sized research laboratory. Participants were first provided with information about the leader’s background and work duties. In the ethical leadership condition, the leader was then described as a person who displays behaviors listed on a widely used ethical leadership scale (e.g., makes fair decision and defines success not just by results but also the way they are obtained; Brown et al. 2005). In the unethical leadership condition, the leader was described as a person who displays an opposite set of behaviors (e.g., makes unfair decisions and defines success by result, but is indifferent about the way they are obtained). In the control condition, no mention was made of ethically laden behavior. All vignettes used in this study are available in Appendix B.

Moral Intensity Manipulation

Among the six dimensions of moral intensity originally proposed by Jones (1991), magnitude of consequences has received the most attention, and is often characterized as the most central component of moral intensity (Frey 2000; McMahon and Harvey 2006). We therefore focused on manipulating participants’ beliefs regarding the magnitude of consequences in our moral intensity manipulation. In the high moral intensity condition, we described the organization as a medical research laboratory seeking to eradicate cancer. In the low moral intensity condition, we described the organization as a geological research laboratory seeking to understand unusual rock formations. We reasoned that whereas cancer research requires leaders to make high-impact decisions that could potentially influence millions of lives, research on rock formations requires leaders to make comparatively low-impact decisions (see Appendix B).

Perceived Potential for Prosocial Impact

We adapted a six-item measure of perceived prosocial impact (Grant 2008b; Grant and Campbell 2007). This measure captures the belief that the individual can have prosocial impact on his or her leader. Whereas the original measure focuses on perceived prosocial impact toward one’s job in general, we reworded the items to focus on the potential to exert a prosocial impact on one’s leader. One item from the original scale was omitted because it references the number of people impacted by one’s action, which does not apply to our research question and context. Sample items from the adapted scale include “I feel that I can make a positive difference in my leader’s life” and “I can have a positive impact on my leader on a regular basis” (1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree; M = 3.07, SD = 1.45, α = 0.97; see Appendix A for the full scale).

Leader-Directed Citizenship Behavior

At the end of the study, participants were told that the leader’s organization experienced a budget cut and needed to downsize its paid workforce. For this reason, the leader was actively seeking volunteers to assist the research lab with its daily tasks. Participants were then given the option to help the leader by screening potential volunteers’ resumes and making recommendations about who to bring in. We told participants that their efforts would help the leader tremendously because otherwise the leader would have to stay at work late into the evening to screen the resumes himself. We also told participants that it would take 2–3 min for them to screen a resume and make a recommendation. On average, participants agreed to screen 1.14 (SD = 1.59) resumes (for similar measures of prosocial behavior, see Greitemeyer and Osswald 2010; Twenge et al. 2007).

Manipulation Checks

To ensure that our manipulations were effective, participants were asked to indicate a if the leader they read about was ethical and b if the work being done by the organization had significant ethical implications (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

Results and Discussion

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the focal variables are presented in Table 3. Analyses of the manipulation checks suggested that both the moral intensity and ethical leadership manipulations were successful. Participants in the high moral intensity condition (M = 6.02, SD = 0.94) rated the work being done by the organization as having significantly more ethical implications than participants in the low moral intensity condition (M = 3.45, SD = 1.19), t(185) = 16.37, p < 0.01. Ratings of the leader’s ethicality also differed by condition, F(2, 184) = 308.64, p < 0.01. Post hoc analyses (Tukey’s HSD) revealed that participants in the ethical leadership condition rated the leader as being significantly more ethical (M = 6.28, SD = 0.85) than participants in the control (M = 4.95, SD = 1.35) or unethical leadership conditions (M = 1.55, SD = 1.06), p < 0.01. In addition, participants in the control condition rated the leader as being significantly more ethical than participants in the unethical leadership condition, p < 0.01.

To test Hypothesis 1, we conducted a 3 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the curvilinear effect of ethical leadership on leader-directed citizenship behavior. Results revealed a main effect of the leadership manipulation, F(2, 181) = 26.67, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.22, but not moral intensity, F(1, 181) = 0.63, p = 0.43. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD) suggested that participants in the control condition engaged in the more leader-directed citizenship behavior (M = 2.07, SD = 1.91) than participants in the ethical leadership (M = 1.13, SD = 1.42) or unethical leadership (M = 0.22, SD = 0.58) conditions, p < 0.01. In addition, participants in the ethical leadership condition engaged in more leader-directed citizenship behavior (M = 1.13, SD = 1.42) than participants in the unethical leadership condition (M = 0.22, SD = 0.58), p < 0.01. These results provided support for Hypothesis 1, suggesting that leader-directed citizenship behavior decreased when the leader displayed high levels of ethical or unethical leadership.

More importantly, results revealed the predicted interaction between ethical leadership and moral intensity of the organizational context, F(2, 181) = 5.06, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.06. As Fig. 2 reveals, participants in the ethical leadership/high moral intensity condition engaged in less leader-directed citizenship behavior (M = 0.62, SD = 0.85) than participants in the control/high more intensity condition (M = 2.27, SD = 1.98), F(2, 181) = 12.66, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.13. Leader-directed citizenship behavior did not differ between participants in the ethical leadership/low moral intensity condition (M = 1.67, SD = 1.69) and control/low moral intensity condition (M = 1.87, SD = 1.85), p = 0.64. As predicted, participants in the unethical leadership/high moral intensity condition engaged in less leader-directed citizenship behavior (M = 0.30, SD = 0.74) than participants in the control leader/high moral intensity condition (M = 2.27, SD = 1.98), F(2, 181) = 17.57, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.16. Likewise, participants in the unethical leadership/low moral intensity condition engaged in less leader-directed citizenship behavior (M = 0.13, SD = 0.35) than participants in the control leader/low moral intensity condition (M = 1.87, SD = 1.85), F(2, 181) = 14.16, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.14. Finally, leader-directed citizenship behavior did not differ between participants in the unethical leadership/high moral intensity condition (M = 0.30, SD = 0.74) and ethical leadership/high moral intensity condition (M = 0.62, SD = 0.85), p = 0.26, but differed between participants in the unethical leadership/low moral intensity condition (M = 0.13, SD = 0.35) and ethical leadership/low moral intensity condition (M = 1.67, SD = 1.69), F(2, 181) = 11.42, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.11. These findings provided support for the predicted curvilinear interactive relationship between ethical leadership and moral intensity of the organizational context on leader-directed citizenship behavior. Specifically, participants engaged in less leader-directed citizenship behavior when moral intensity of the organizational context and ethical leadership were high, but the same effect was not observed when moral intensity was low. In short, these results supported Hypothesis 2.

To test Hypothesis 3, we utilized the bootstrapping-based analytic approach of Edwards and Lambert (2007) and the statistical software of Hayes (2013) to test for conditional indirect effects at high versus low levels of moral intensity (with 1000 resamples). We first utilized a 3 × 2 ANOVA to examine whether or not the interactive effect of ethical leadership and moral intensity of the organizational context exhibited a similar curvilinear effect on perceived potential for prosocial impact. Results revealed the predicted interaction between the two factors, F(2, 181) = 20.08, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.18. As shown in Fig. 3, pattern of findings for perceived potential for prosocial impact was virtually identical to the pattern of findings for leader-directed citizenship behavior. Results suggested that participants in the ethical leadership/high moral intensity condition reported significantly lower levels of perceived potential for prosocial impact (M = 2.65, SD = 0.98) than participants in the control/high moral intensity condition (M = 4.74, SD = 0.71), F(2, 181) = 6.13, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.04. As predicted, perceived potential for prosocial impact did not differ between participants in the ethical leadership/low moral intensity condition (M = 3.68, SD = 0.91) and participants in the control leader/low moral intensity condition (M = 4.27, SD = 0.47), F(2, 181) = 2.92, p = 0.09. In short, these results suggested that the patterns of the curvilinear interactive effect between ethical leadership and moral intensity of the organizational on perceived potential for prosocial impact were similar to those on leader-directed citizenship behavior, providing initial evidence that perceived potential for prosocial impact might mediate the curvilinear interactive relationship.

To test H3 in an integrated fashion, we entered the quadratic ethical leadership term as the independent variable, moral intensity as the first-stage moderator, perceived potential for prosocial impact as the mediator, leader-directed citizenship behavior as the dependent variable, and controlled for the linear ethical leadership term using Hayes (2013)’s statistical software. The logic for controlling the linear predictor is the same as if the analyses were conducted via hierarchal regression (i.e., Study 1; Cohen et al. 2003). Results suggested that the conditional indirect effects of perceived potential for prosocial impact were significant in both models. When moral intensity was high, the indirect effect of perceived potential for prosocial impact was − 2.44 (SE = 0.33, 95% CI = − 3.12 to − 1.88). When moral intensity was low, the indirect effect of perceived potential for prosocial impact was − 1.05 (SE = 0.29, 95% CI = − 1.68 to − 0.54). However, the difference between the two indirect effects was also significant, t = 18.39, p < 0.01. These results suggested that perceived potential for prosocial impact mediated the curvilinear interactive effect between ethical leadership and moral intensity on leader-directed citizenship behavior, and that the mediating effect was stronger when moral intensity of the organizational context was high.

General Discussion

Recent research, drawing primarily from social learning theory and social exchange theory, has shown that ethical leadership can have broad and far-reaching positive effects (Brown and Mitchell 2010). Though useful, neither of these theories is specific to the moral domain but applies to the social contexts in general. Decades of research suggest that the moral relevance of an action dramatically influences how it is perceived and responded to (Haidt 2008), suggesting the need to understand ethical leadership through the lens of morality-specific theories. Drawing from moral typecasting theory, we found support for a curvilinear-moderated mediation model that explains when and why ethical leadership influences the amount of help leaders receive from their followers. First, we found that followers are least likely to help their leaders when they display high levels of unethical behavior or high levels of ethical behavior. Second, we found that this effect is most likely to emerge in morally intense organizational contexts. Third, we found that this interactive curvilinear effect is mediated by followers’ perceptions that they can exert a prosocial impact on their leaders. Below, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Theoretical Implications

Our research contributes to the ethical leadership literature in several ways. First, by invoking a theoretical perspective not used before to approach ethical leadership, we bring attention to one of ethical leadership’s potentially negative consequences for leaders. Within the ethical leadership literature, scholars have displayed a consistent focus on the positive effects of ethical leadership. Although useful, this focus is problematic to the extent that it ignores more nuanced implications of ethical leadership, including its potential negative effects. Research on transformational leadership and other prominent leadership styles has long acknowledged the potentially negative effects of generally desirable behaviors (for a review, see Tourish 2013), but ethical leadership scholars have remained unilaterally optimistic about the consequences of ethical leadership. Indeed, scholars have only recently begun to examine the potential negative effects of ethical leadership, demonstrating that highly ethical leaders can at times lead their followers to act unethically (Miao et al. 2013) or engage in less citizenship toward their peers (Stouten et al. 2013). Our results add a unique insight into this discussion by (a) emphasizing the negative implications of ethical leadership for leaders themselves, and (b) utilizing moral typecasting theory to identify key boundary conditions and mechanisms of this effect. Importantly, our findings are in sharp contrast with the predictions of social learning (e.g., Brown et al. 2005) and social exchange (e.g., Walumbwa et al. 2011) theories. Whereas these theories posit unilaterally positive effects of ethical leadership, moral typecasting theory offers a more nuanced set of implications consistent with our empirical findings. More generally, our findings also suggest that leaders need help from their followers to succeed (Fletcher 2004).

Second, we contribute to the ethical leadership literature by redirecting scholarly attention toward leaders themselves. Research on ethical leadership and leadership in general has tended to focus exclusively on leadership’s effects on leaders’ followers, work groups, and organizations (for a review, see Avolio et al. 2009). If leadership can be learned (Doh 2003), then the rewards and punishments leaders receive for their ethical actions might play a critical role in the continuance of ethical behavior. For example, perhaps some ethical leaders consistently display ethical behavior at work because it is valued by senior management (Rubin et al. 2010). Conversely, some leaders may not wish to be cast into the role of ethical leader if the role equates to fewer followers helping them through their own trials and tribulations as our study suggests. This theoretical implication leads to an even more fascinating question: does ethical leadership shape followers’ behaviors, or do followers’ behaviors shape ethical leadership? Whereas past research suggests that followers’ behaviors are outputs of ethical leadership, our findings suggest that followers’ behaviors can potentially be inputs for ethical leadership. Thus, the feedback leaders receive from their followers might partly explain why many leaders do not choose to explicitly discuss and demonstrate ethics at work (Bird and Waters 1989). Accordingly, this study provides a unique perspective on how moral typecasting, and its accompanying relational schema, allow followers to create or influence ethical leadership. This finding is consistent with a larger literature that identifies followers as co-creators of leader behavior (Uhl-Bien 2006; Uhl-Bien et al. 2014). We suggest that our research represents a promising first step in increasing our understanding of the formation of ethical leadership and hope to spark additional research in examining the role of followership in the development and sustainment of ethical leadership.

Our third contribution to the ethical leadership literature lies in our incorporation of context as a key boundary condition of ethical leadership’s effects. In recent years, scholars have called for greater attention to the role of the social context in leadership research (Avolio 2007). In both of our studies, we demonstrated that the curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and leader-directed citizenship behavior is strongest in morally intense organizational contexts. This finding suggests that the positive effects of ethical leadership on followers might also be strongest when leaders and followers are working in morally intense contexts. For example, ethical leaders might be most likely to encourage whistleblowing in morally intense organizational contexts, as the potential consequences of whistleblowing are particularly high (Jones 1991). From a practical perspective, the impact of moral intensity suggests that scholars should direct their efforts toward conducting ethical leadership research in morally intense contexts (e.g., military, healthcare) whenever possible.

Finally, our research contributes to the ethical leadership literature by highlighting the importance of followers’ beliefs regarding their potential for prosocial impact. Although previous research has demonstrated the powerful effect of prosocial impact on performance, effort, and persistence (Grant 2008a; Grant et al. 2007), a direct link between perceived potential for prosocial impact and citizenship behavior is lacking in the literature. Our research indicates that followers are less likely to engage in citizenship behavior when they do not think that their citizenship behavior can have a meaningful impact on their leaders. In light of this, it is possible that ethical leaders may be able to promote followers’ leader-directed citizenship behaviors by, as Grant and Gino (2010) suggest, explicitly acknowledging the importance of their help and ensuring that they possess the skills needed to exert a prosocial impact.

Practical Implications

Ethical leadership development and training is one of the most important pedagogies among contemporary leadership scholars (Ashforth et al. 2008).

Although ethical leadership is negatively associated with followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior, it is positively associated with leaders’ promotability to senior management positions (Rubin et al. 2010). Furthermore, from a utilitarian perspective, we expect that the aggregated positive effects of ethical leadership far outweigh the negative effects found in this research. Thus, we suggest that organizations can use the findings from this study to augment their training programs. By becoming aware that decreased leader-directed citizenship behavior as a potential downside to ethical leadership, organizations can protect against such negative effects by proactively training their leaders to express their own vulnerability and seek for their followers’ help.

Limitations and Future Directions

As with all research, our studies are not without their limitations, highlighting several fruitful avenues for future research. First, our studies are limited in their focus on moral intensity as the primary moderator of ethical leadership’s effects. In addition, when manipulating moral intensity experimentally in study 2, we were constrained to only manipulating one of the components of moral intensity, magnitude of consequences. Although research suggests that this is one of the most predictive components of moral intensity (Frey 2000; McMahon and Harvey 2006, 2007; Tsalikis et al. 2008), we do potentially sacrifice breadth. Future research should consider a much broader set of moderating factors to further enhance our understanding of ethical leadership and the boundaries of its effects. For example, a strong leader–follower exchange relationship might offset the negative effect of moral typecasting. In addition, because perceived potential for prosocial impact is the underlying mechanism that drives the curvilinear interactive effect we uncovered, perhaps followers who are higher in moral self-efficacy are also more confident with their abilities in exerting a meaningful prosocial impact on their leaders, thereby counteracting the moral typecasting effect (Caprara and Steca 2005).

Second, our study focuses solely on followers in the role of moral patient and leaders in the role of moral agent in a given leader–follower relationship. Although moral typecasting theory suggests followers and leaders would typically be typecast as such and that those roles would be fairly stable over time, the roles of moral agent/patient and leader/follower are independent of each other. Accordingly, future research should consider under what circumstances followers might be considered by onlookers as moral agents, including by their own leaders. For example, exogenous shocks such as the promotion of a follower to a higher status position might cause him or her to be seen as a moral agent. Changes to a leader’s status might also trigger a change in how he or she is typecast.

Third, another limitation of our research is our reliance on perceived potential for prosocial impact as our principle mediator (i.e., a follower belief). Notably, we only tested this mediator in the lab experiment and our results would be stronger if we had tested for it in the field study as well. In addition, moral typecasting theory suggests that other mediators might also be plausible. For example, perhaps followers are unable to empathize with highly ethical and unethical leaders’ suffering at work, but are able to empathize with leaders who are moderately ethical but flawed. Indeed, the emotional response that is hypothesized to be least associated with moral agency is sympathy—a moral emotion generally reserved for moral patients (Gray and Wegner 2010). It is therefore plausible that the current findings could be mediated by a lack of sympathy toward the highly ethical leadership. Similarly, future research can also examine positive emotions such as inspiration or elevation elicited by the highly ethical leader. Past research suggests that these positive emotions are not target specific (Vianello et al. 2010) and therefore ethical leader-elicited elevation might encourage followers to do good, but only toward others as moral typecasting theory would predict. Future research can further advance our understanding of the effects of moral typecasting on ethical leadership by exploring these underlying emotional processes, along with other potential mediating mechanisms.

Finally, although ethicality is especially emphasized in ethical leadership theories, it is also a component in many other leadership styles (Avolio et al. 2009). If ethicality is a shared component across many desirable leadership styles, our results suggest that the moral typecasting effect might also apply to other leadership styles, such as transformational leadership. In addition, consistent with dyadic or relational perspectives of leadership (i.e., relational leadership theory, Uhl-Bien 2006; LMX; Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995), research has shown that ethical leadership is positively related to the quality of the leader–follower relationship (Walumbwa et al. 2011). In light of the implications of moral typecasting theory, further research should explore how the quality of the leader–member relationship influences follower helpfulness toward the leader in morally intense contexts. In short, we believe that future research can greatly expand the applicability of moral typecasting theory to other leadership frameworks beyond ethical leadership.

Conclusion

In this research, we have introduced moral typecasting theory as a new framework in the study of ethical leadership, emphasizing the moderating role of the organizational context, focusing on one implication of ethical leadership for leaders themselves, and identifying a new mechanism for ethical leadership’s effects. Each of these extensions suggests new directions for ethical leadership research, moving beyond current theoretical frameworks and conceptualizations of ethical leadership’s nomological net. Although our results suggest that ethical leadership can have negative implications, we emphasize our hope that these findings do not discourage organizations from developing ethical leaders, but rather help organizations proactively manage its perils.

Notes

Although most leaders are themselves followers of higher level leaders, we suggest that in general a given follower will seldom experience this first-hand. For instance, a low-level employee will seldom directly observe high-level meetings between his leader and a top management team. In other words, on average, leaders are more likely to be perceived as moral agents than employees not in leadership positions.

Of course, unethical leaders are likely to receive less help from their followers for a wide variety of reasons. However, the curvilinear hypothesis is uniquely predicted by moral typecasting theory. For instance, social exchange theory might explain why unethical leaders receive little help from their followers, but it does not predict a curvilinear effect.

We did not use Settoon and Mossholder’s (2002) task-focused scale because the items imply that the follower is able to help the leader with his or her specific job duties, and many followers might lack the knowledge or ability to engage in this type of helping behavior.

References

Ashforth, B., Gioia, D., Robinson, S., & Treviño, L. (2008). Re-viewing organizational corruption. Academy of Management Review, 33, 670–684.

Avolio, B. (2007). Promoting more integrative strategies for leadership theory-building. American Psychologist, 62, 25–33.

Avolio, B., Walumbwa, F., & Weber, T. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 421–441.

Baldwin, M. (1992). Relational schema and processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 461–484.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barnes, C. M., Schaubroeck, J., Huth, M., & Ghumman, S. (2011). Lack of sleep and unethical conduct. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 169–180.

Bastian, B., Laham, S., Wilson, S., Haslam, N., & Koval, P. (2011). Blaming, praising, and protecting our humanity: The implications of everyday dehumanization for judgments of moral status. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 469 –483.

Bird, F., & Waters, J. (1989). The moral muteness of managers. California Management Review, 32, 73–88.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: John Wiley.

Bornstein, R. (1994). Dependency as a social cue: A meta-analytic review of research on the dependency—helping relationship. Journal of Research in Personality, 28, 182–213.

Broverman, I., Vogel, S., Broverman, D., Clarkson, F., & Rosenkrantz, P. (1972). Sex-role stereotypes: A current appraisal. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 59–78.

Brown, M., & Mitchell, M. (2010). Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20, 583-616.

Brown, M., & Treviño, L. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 91, 954–962.

Brown, M., Treviño, L., & Harrison, D. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Butterfield, K., Treviño, L., & Weaver, G. (2000). Moral awareness in business organizations: Influences of issue-related and social context factors. Human Relations, 53, 981–1018.

Caprara, G., & Steca, P. (2005). Self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of prosocial behavior conducive to life satisfaction across ages. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24, 191–217.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd edn.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

De Cremer, D., Mayer, D., van Dijke, M., Schouten, B., & Bardes, M. (2009). When does self-sacrificial leadership motivate prosocial behavior? It depends on followers’ prevention focus. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 887–899.

Doh, J. (2003). Can leadership be taught? Perspectives from management educators. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2, 54–67.

Doherty, A. (1997). The effect of leader characteristics on the perceived transformational/transactional leadership and impact of interuniversity athletic administrators. Journal of Sport Management, 11, 275–285.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38, 1715–1759.

Dvir, T., & Shamir, B. (2003). Follower developmental characteristics as predicting transformational leadership: A longitudinal field study. Leadership Quarterly, 14, 327–344.

Eagly, A., & Chin, J. (2010). Diversity and leadership in a changing world. American Psychologist, 65, 216–224.

Eagly, A., & Crowley, M. (1986). Gender and helping behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 283–308.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 21, 1–22.

Fehr, R., Yam, K. C., & Dang, C. T. (2015). Moralized leadership: The construction and consequences of ethical leader perceptions. Academy of Management Review, 2, 182–209.

Fiske, A. (1992). The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review, 99, 689–723.

Fletcher, J. K. (2004). The paradox of postheroic leadership: An essay on gender, power, and transformational change. Leadership Quarterly, 15(5), 647–661.

Frey, B. (2000). The impact of moral intensity on decision making in a business context. Journal of Business Ethics, 26, 181–195.

Graen, G., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi- level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219–247.

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32, 393–417.

Grant, A. M. (2008a). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 108–124.

Grant, A. M. (2008b). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 48–58.

Grant, A. M., & Campbell, E. M. (2007). Doing good, doing harm, being well and burning out: The interactions of perceived prosocial and antisocial impact in service work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80, 665–691.

Grant, A. M., Campbell, E. M., Chen, G., Cottone, K., Lapedis, D., & Lee, K. (2007). Impact and the art of motivation maintenance: The effects of contact with beneficiaries on persistence behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103, 53–67.

Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 98, 946–955.

Gray, H., Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2007). Dimensions of mind perception. Science, 315, 619.

Gray, K. (2010). Moral transformation: Good and evil turn the weak into the mighty. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1, 253–258.

Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2009). Moral typecasting: Divergent perceptions of moral agents and moral patients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 505–520.

Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2010). Dimensions of moral emotions. Emotion Review, 3, 258–260.

Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2011). Morality takes two: Dyadic morality and mind perception. In P. Shaver & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), The social psychology of morality (pp. 109–127). Washington, DC: APA Press.

Gray, K., Young, L., & Waytz, A. (2012). Mind perception is the essence of morality. Psychological Inquiry, 23, 101–124.

Greitemeyer, T., & Osswald, S. (2010). Effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 211–221.

Haidt, J. (2008). Morality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 65–72.

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and condition process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychological of interpersonal relationships. New York: Wiley.

Highhouse, S. (2009). Designing experiments that generalize. Organizational Research Methods, 12, 554–566.

Hollenbeck, J. R. (2008). The role of editing in knowledge development: Consensus shifting and consensus creation. In Y. Baruch, A. M. Konrad, H. Aguinis & W. H. Starbuck (Eds.), Opening the black box of editorship (pp. 16–26). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jones, T. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16, 366–395.

Kacmar, K., Bachrach, D., Harris, K., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 633 –642.

Kalshoven, K., Hartog, D., De Hoogh, D., A (2011). Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 51–69.

Kelley, P., & Elm, D. (2003). The effect of context on moral intensity of ethical issues: Revising Jones’s issue-contingent model. Journal of Business Ethics, 48, 139–154.

May, D., & Pauli, K. (2002). The role of moral intensity in ethical decision making: A review and investigation of moral recognition, evaluation, and intention. Business and Society, 41, 84–117.

Mayer, D., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151–171.

Mayer, D., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 1–13.

McMahon, J., & Harvey, R. (2006). An analysis of the factor structure of Jones’ moral intensity construct. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 381–404.

McMahon, J. M., & Harvey, R. J. (2007). The effect of moral intensity on ethical judgment. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 335–357.

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Yu, J., & Xu, L. (2013). The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Linear or curvilinear effects? Journal of Business Ethics, 116, 641–653.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). Ethical leadership: Meta-analytic evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 948–965.

Nohria, N., & Khurana, R. (2010). Handbook of leadership theory and practice. Harvard Business Press.

Piccolo, R., Greenbaum, R., Hartog, D., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 259–278.

Podsakoff, P., Whiting, S., Welsh, D., & Mai, M. (2013). Surveying for “artifacts”: The susceptibility of the OCB-performance evaluation relationship to common rater, item, and measurement context effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 863–874.

Reynolds, S. (2006). Moral awareness and ethical predispositions: Investigating the role of individual differences in the recognition of moral issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 233–243.

Rosette, A. S., Leonardelli, G. J., & Phillips, K. W. (2008). The White standard: Racial bias in leader categorization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 758–777.

Rubin, R., Dierdorff, E., & Brown, M. (2010). Do ethical leaders get ahead? Exploring ethical leadership and promotability. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20, 215–236.

Schaubroeck, J., Hannah, S., Avolio, B., Kozlowski, S., Lord, R., Treviño, L., Dimotakis, N., & Peng, A. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organizational levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1053–1078.

Settoon, R., & Mossholder, K. (2002). Relationship quality and relationship context as antecedents of person- and task-focused interpersonal citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 255–267.

Shamir, B. (2007). From passive recipients to active co-producers—The roles of followers in the leadership process. In B. Shamir, R. Pillai, M. Bligh & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), Follower-centered perspectives on leadership: A tribute to J. R. Meindl. Stamford, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Stouten, J., van Dijke, M. H., Mayer, D., De Cremer, D., & Euwema, M. (2013). Can a leader be seen as too ethical? The curvilinear effects of ethical leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 680–695.

Tepper, B. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 2, 178–190.

Tourish, D. (2013). The dark side of transformational leadership: A critical perspective. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Tsalikis, J., Seaton, B., & Shepherd, P. (2008). Relative importance measurement of the moral intensity dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 80, 613–626.