Abstract

To make a business case for corporate sustainability, firms must be able to sell their sustainable products. The influence that firm engagement with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) may have on consumer adoption of sustainable products has been neglected in previous research. We address this by embedding corporate sustainability in a cosmopolitan framework that connects firms, consumers, and civil society organizations based on the understanding of responsibility for global humanity that underlies both the sustainability and cosmopolitanism concepts. We hypothesize that firms’ sustainability engagement and their NGO engagement influence consumer adoption of sustainable products. Empirically, we investigate the adoption of sustainable Eco-circle products made from recycled fibers marketed by Li Ning, a China-based global sportswear brand. We apply a stepwise regression approach to test our hypotheses with paper-and-pencil survey data from 217 Chinese consumers. We find adoption to be positively associated with consumers’ sustainability attitude but not with firms’ sustainability engagement. For firm–NGO engagement, these relationships are reversed: Adoption is positively associated with firm–NGO engagement, but not with consumers’ related attitude. Our results present a picture of the Chinese context in which there is a business case for corporate sustainability if firms’ words about sustainable product strategies are supported by signals from civil society about firm deeds. The results imply that in a Chinese context, firms need to be particularly aware of the role of NGOs when hoping to be rewarded for sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) translate the so-called triple bottom line of social, environmental, and economic goals (Dyllick and Hockerts 2002; Elkington 1999) into 17 specific “goals to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all” (United Nations 2016) and further specify that “for the goals to be reached, everyone needs to do their part: governments, the private sector, civil society and people like you.” This cosmopolitan approach highlights the interconnectedness of various social and economic actors, implying that sustainable solutions require effective relationships between actors such as consumers (“people like you”), firms (“the private sector”), and non-governmental organizations (“civil society”).

We add to work that connects these three groups and investigate how firms’ general sustainability engagement and their engagement with civil society influence consumers’ response to sustainable products. Specifically, we ask two questions: (A) Does a firm’s sustainability engagement influence consumers’ choice to adopt sustainable products? (B) Does a firm’s engagement with non-governmental organizations influence consumers’ choice to adopt sustainable products? To answer these questions, we use a cosmopolitan lens (Appiah 2006; Held 2010) to argue for a set of shared cosmopolitan values underlying sustainability perspectives at consumer, firm, and NGO levels. We then build on the established understanding of adoption theory that shared values may reduce consumers’ perceived uncertainty and drive product adoption (Rogers 1962, 2003). In doing so, we contribute to three ongoing debates in this journal.

First, we make a contribution to the sustainable consumption debate that explores relationships between consumers’ attitudes and behaviors (Govind et al. 2017). We connect work on consumption of products with sustainable characteristics such as organic food and recycled textiles (Jung et al. 2016; Luchs and Kumar 2017; Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen 2017) with work that explores consumer responses to sustainable firm behaviors such as supporting gender equality and making corporate donations (Choi and Ng 2011; Deng and Xu 2017; Romani et al. 2016; Van Quaquebeke et al. 2017). Our findings particularly inform discussions about consumers whose attitudes are inconsistent with their purchase behaviors (Gruber and Schlegelmilch 2014), often described as the intention–behavior gap (Caruana et al. 2016; Devinney et al. 2010). The contradictions between attitudes, intentions, and behaviors have been explained by conceptually distinguishing a general attitudinal from a more concrete behavioral level of intentions—what Carrington et al. (2010) call “implementation intentions.” Empirically based on two longitudinal studies, Govind et al. (2017) show how explicit, verbalized attitudes differ from implicit, behaviorally relevant sustainability attitudes. We contribute to this debate by distinguishing consumers’ response to firm sustainability from their response to product sustainability. We thereby contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the behavioral relevance of sustainability attitudes.

Second, we contribute to the debate on sustainability reporting and assurance. Studies in this area discuss both the internal challenge firms face when deciding what sustainability information to provide (Comyns 2016; Haller et al. 2016; Searcy et al. 2016) and the external challenge of how to assure quality of the reported information (Boiral et al. 2017; Hummel et al. 2017; Junior et al. 2014; Perego and Kolk 2012). NGOs are often attributed a mediating role between firms and consumers in assuring the quality of sustainability information (Manetti and Toccafondi 2012; Sethi et al. 2017) and in interpreting this information to make it useful to consumers, e.g., in NGO publications and materials or by participating in sustainability labeling schemes (Darnall et al. 2016; Dendler 2014). In addition, NGOs have a watchdog role that involves criticizing firms’ unsustainable practices (Dubbink et al. 2008; Yaziji and Doh 2009), as well as a more cooperative role when working with firms to solve these problems (Baur and Schmitz 2012; Frig et al. 2016). The general assumption about the consumer–NGO relationship is that while consumers lack the competence to understand and evaluate complex sustainability information (Longo et al. 2017), NGOs act as impartial intermediaries who can provide comprehensible information that consumers can trust (Sethi et al. 2017). While most of this literature considers NGOs’ informational role and their influence on consumers’ ideas about sustainable firms, we argue that NGOs influence consumers in ways that go beyond their traditional watchdog role. Namely, we contribute by considering the shared cosmopolitan values in the relationships between consumers, firms, and NGOs that make the social relationships that consumers perceive between firms and NGOs also extremely relevant.

Third, we make a contribution to the stream of publications that explores cosmopolitan engagement in China, the empirical context of our study. In Chinese corporate sustainability contexts, firms have generally not been expected to display cosmopolitan behaviors such as engaging with civil society or with organizations such as NGOs (Yin and Zhang 2012). Moreover, there may be a tendency for firms to perform symbolic actions in order to create positive public perceptions, rather than undertaking measures to effectively improve social and environmental conditions (Li et al. 2017). Some have argued that local Confucian values that prioritize personal relationships over the common good run counter to cosmopolitan values of equality and concern for the other (Ip 2009). Nevertheless, recent research has found that some Chinese consumers do seem to care about the sustainability of brands they patronize (Deng and Xu 2017) and products they purchase (Jung et al. 2016). We contribute to this stream by suggesting a more fine-grained view of Chinese consumers’ responses to cosmopolitan initiatives, suggesting that they may respond to specific aspects of the relationships between firms and NGOs.

The paper continues as follows: First, we develop our cosmopolitan framework that includes the roles of consumers, firms, and civil society. Next, we develop hypotheses and present our model that explains adoption of sustainable products. We then introduce our empirical context and method, a consumer survey in a Chinese second-tier city exploring adoption of Li Ning’s Eco-circle line, a sustainable innovation by a major Chinese sportswear brand. We then present the results of stepwise hierarchical regression analyses. Finally, we discuss our results and relate them to the existing streams of research on sustainable consumption and sustainability reporting and assurance, and consumer responses to sustainability in China before we close with a reflection on limitations and on implications for research, ethics, and business practice.

Theoretical Framework: Moral Cosmopolitanism

We develop our theoretical framework in this section. First, we introduce cosmopolitanism as a theoretical foundation that posits global interconnectedness and responsibilities to others that override the international boundaries that divide people (Hayden 2005; Holton 2009). Second, we explore how cosmopolitanism can be conceptualized for consumers (Cannon and Yaprak 2002), firms (Crane et al. 2008; Garsten 2003; Ghemawat 2011; Maak and Pless 2009), and civil society groups (Kaldor et al. 2003; Maak 2009; Macdonald and Macdonald 2010; Scholte 2002).

Cosmopolitanism Defined

Cosmopolitanism denotes an attitude of openness to the other, a belief in the basic unity of humanity which surpasses the power of national boundaries and borders to divide, and an interest in cultural diversity and variety (Appiah 2006; Nussbaum 1994). It can be expressed in individual behaviors such as consumers’ decisions to travel globally or sample foreign food, or in political and economic projects to build supranational organizations (Szerszynski and Urry 2002; Woodward et al. 2008), with the United Nations being the most prominent example. On a moral level, the assumption of the basic unity of humanity leads to the development and application of global norms of behavior, and thus to greater global responsibility than traditional nationally oriented thinking. A cosmopolitan outlook is therefore often associated with a concern to ensure that people, no matter where they are in the world, enjoy certain basic standards, such as a clean environment, education, and economic security (Held 2009). This is exemplified in the United Nations SDG which we introduced as the starting point of our study.

On an individual level, cosmopolitanism implies that every human has obligations to others, independent of any personal ties he or she may have with them, or where they may be in the world (Hayden 2005). It is further characterized by a desire to address those global problems that may potentially undermine the foundations of human life, such as global environmental threats and poverty (Archibugi 2008). On a collective level, cosmopolitan thinking addresses the actors to be involved in the development of solutions to these problems and, as outlined in the introductory paragraph of this article, suggests that besides national states, non-state actors such as multinational firms (“the private sector”), and NGOs (“civil society”) have a role to play (Held 2009; Ruggie 2008; United Nations 2016). The connection of the various players on the individual and collective levels is conceptualized as a set of shared underlying cosmopolitan values (Beck 2006).

Cosmopolitanism thus connects well with the conceptual foundations of sustainability as it considers the needs of others, particularly others who may be located at a distance from ourselves, or who are very different and who may lack a voice with which to express their needs. Broadly defined, these “others” can include the environment and future generations (Beck 2006). Moreover, cosmopolitanism has been applied to analysis of consumers (Cannon and Yaprak 2002), firms (Ghemawat 2011), and NGOs (Kaldor et al. 2003), which we explore below.

Cosmopolitan Roles: Consumers, Firms, and Civil Society

A Cosmopolitan Perspective on Consumers

The idea of cosmopolitanism has been applied to the sphere of consumption (Cannon and Yaprak 2002; Thompson and Tambyah 1999; Woodward et al. 2008). Cosmopolitans may use consumption to express their preferences and aspirations, especially for sampling products from diverse cultures (Riefler et al. 2012). In consumer research, prior work typically seems to equate a cosmopolitan mindset with a global mindset and thus focuses on the purchase of culturally distinctive products. Along these lines, consumer cosmopolitanism is conceptually treated as the opposite of consumer ethnocentrism (Horn 2009). In the literature, cosmopolitan consumers have been defined as open-minded with an appreciation of diversity and consumption patterns that attribute less relevance to borders and to the claims of their peers and local preferences when making consumption decisions (Riefler et al. 2012).

Generally speaking, research on consumer cosmopolitanism has focused more on the aesthetic dimension of consumption, on the curiosity and openness of people interested in cultural products rather than on the moral sustainability-related concerns of these consumers. Aesthetic cosmopolitanism with its focus on consumers’ tastes for global products is a “narrow form of cosmopolitanism” (Bookman 2013, p. 56) and neglects the normative implications of consumption (Parts and Vida 2011) which are addressed in moral cosmopolitan perspectives (Emontspool and Georgi 2017) as developed in this paper.

Emontspool and Georgi (2017) explicitly conceptualize consumption as the means through which consumers put into practice their moral cosmopolitan values and beliefs. As this moral cosmopolitanism suggests concern for the other as well as an interest in and tolerance of difference, one might expect that cosmopolitan consumers are curious and willing to try new things, but will prefer products that are sustainable and not harmful to people or the environment. Sustainable consumption has in this context been specified as a means to express one’s values, beliefs, and ultimately one’s self as a moral cosmopolitan consumer (Naderi and Strutton 2015). Moreover, firms and civil society groups have been found to be important to consumers in their responses to sustainability concerns (Caruana and Chatzidakis 2014). We will next examine these two actors using a moral cosmopolitan lens.

A Cosmopolitan Perspective on Firms

In line with approaches to corporate sustainability that posit an increasingly political role for the firm (Crane et al. 2008; Scherer and Palazzo 2011), globally oriented firms have been conceptualized as potentially “cosmopolitan” (Garsten 2003; Ghemawat 2011; Maak 2009). This results from the role global firms play not simply via their economic activities, but also through the values they express and the social and environmental policies they support. Indeed, many firms have tried to position themselves as cosmopolitan. For instance, Moosmayer and Davis (2016) found evidence of “cosmopolitan discourse” in corporate sustainability reports. Although strikingly different subtypes of cosmopolitan discourse were found, there was evidence that firms attempted to align themselves with cosmopolitan values, such as respect for human rights norms and standards for environmental protection.

Corporate sustainability activities provide one way in which firms can demonstrate a cosmopolitan orientation. In their corporate sustainability engagements, firms typically address global social or environmental problems (Carroll 1998; Yin and Jamali 2016) and inform the global public through corporate sustainability reporting about the social and environmental impact of their activity (Comyns 2016; Haller et al. 2016). However, Kozlowski et al. (2015, p. 392) found “a wide variation in reporting practices” among different brands in the apparel industry and inconsistency among the corporate sustainability indicators reported. This finding is in line with the results of diverse studies suggesting that corporate sustainability may be understood quite differently in different firms and industries (Beschorner and Hajduk 2017).

Different understandings of sustainability, ethics, and responsibility may depend on context and apply at a national level as well (Hofman et al. 2017; Matten and Moon 2008; Moosmayer et al. 2016). For instance, the corporate sustainability policies of companies in more traditional societies, such as Bangladesh, may reflect the priorities of local political parties (Uddin et al. 2016) rather than expressing a cosmopolitan understanding of responsibility. Moosmayer and Davis (2016) identify differences between European-style reports as compared to American and Chinese reporting. Studies of Chinese corporate responsibility reports have found that they tend to emphasize charitable efforts, employee benefits, and adherence to local laws rather than a concern for more global issues such as environmental protection or sustainability in their supply chains (Tang and Li 2009; Yin and Zhang 2012). Along these lines, Xu and Yang (2010) find that local Chinese conceptions of corporate sustainability include dimensions such as promoting national and local economic development, paying taxes, and increasing employment opportunities.

Besides corporate sustainability engagement, firms can express their cosmopolitan orientations in other ways (Maak and Pless 2009; Maak 2009). One example of this could be firms’ attempt to develop products that provide solutions to social and environmental problems. They might further seek to engage with partners to address and resolve such problems (Hansen and Spitzeck 2011). This might take place in engagement with civil society groups such as NGOs (Grosser 2016; Høvring et al. 2016).

A Cosmopolitan Perspective on Civil Society

Civil society is the sphere of social life that is not organized by markets (where businesses operate), private households, or the state (Kaldor 2003). It is generally understood as being the home for NGOs and other nonprofit associations. Civil society is the social space in which people can engage with each other and discuss, coming together to form organizations to pursue common interests and goals. The size and scope of civil society varies, with some countries providing a great deal of free space for public involvement and organization, and others restricting this space. However, some suggest that a cosmopolitan global civil society is developing, providing a social space that connects people around the world, for example in NGOs (Kaldor 2003; Kaldor et al. 2003; Scholte 2002). NGOs can be understood as voluntary associations that represent the interests of those who cannot speak up for themselves (including non-humans, such as species, or the environment in general). “[NGOs’] activity on behalf of others is closely intertwined with systematically cultivating alliances across international borders and is, at least to a large extent, inspired by universalistic ideas” (Heins 2008, p. 19).

NGOs can apply collaborative and conflictual strategies. Collaborative strategies are often aimed at achieving mutual goals together with firms (Baur and Schmitz 2012; Frig et al. 2016), while conflictual strategies usually involve putting pressure on firms via “critical players” in order to cause changes in firm behavior (Dubbink et al. 2008; Yaziji and Doh 2009). Caruana and Chatzidakis (2014) argue that due to a lack of direct legislative power, NGOs may reach out to consumers, and the authors distinguish three types of NGO–consumer engagement: NGOs can use consumers instrumentally to exert pressure on firms to behave more sustainably, relationally in order to build connections with and among consumers, producers, and market intermediaries, and morally as their organizational purpose is often a morally motivated cause. In other words, NGOs may stimulate consumers based on a shared moral cosmopolitan understanding to make moral cosmopolitan decisions and purchase products that are in line with moral cosmopolitan ideas.

A Cosmopolitan Model of Sustainable Product Adoption

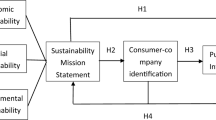

This study aims to explore whether (A) a firm’s sustainability engagement and (B) a firm’s engagement with NGOs influence consumers’ choice to adopt sustainable products. In line with these aims, we use sustainable product adoption as the dependent variable, which describes consumers’ willingness to purchase Li Ning’s sustainable Eco-circle sportswear products in our study. (For details, see section Method: Context of the Study—Li Ning as an Example of a Cosmopolitan Chinese Firm.) After developing our core construct sustainable product adoption, we conceptualize the relationships with sustainability engagement and firm–NGO engagement, and consumers’ corresponding attitudes as determinants of adoption. The model is depicted in Fig. 1.

Consumer Adoption of Sustainable Products

The focal concept of our study is sustainable product adoption, which describes consumers’ willingness to purchase a sustainable product, i.e., a product that may be provided by a known firm and that is socially and/or environmentally more sustainable than previously available options. The adoption of new products is crucial for turning toward more sustainable business practices and consumer lifestyles. Adoption theory (Rogers 1962, 2003) has established that consumers often adopt products for their additional benefits, but may be held back by a risk of uncertainty and the potential need to put effort into learning to use the product (Rogers 2003). Addressing these risks is crucial for product diffusion. This is particularly the case for sustainable products because consumers sometimes need to respond to trade-offs between sustainability and other valued attributes (Luchs and Kumar 2017) or may even associate sustainability with reduced quality (Rusinko and Faust 2016).

Product characteristics have been categorized by the extent to which they can be assessed by consumers. These include “search qualities,” which consumers can assess during the purchase process (e.g., the color of a shirt), “experience qualities,” which consumers can assess during the use of the product (e.g., its durability), and “credence qualities,” which consumers can usually not assess but have to believe (e.g., that production is free of child labor) (Darby and Karni 1973). For search qualities, consumers can reduce adoption risk by observation; for experience qualities, firms can offer free trials and a generous return policy (Iyengar et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2017). For credence qualities, however, trial use does not help, but third-party confirmation, e.g., through labels (Dendler 2014), could reduce adoption risk. Such certification is often provided and communicated through civil society groups, highlighting the potential importance that NGOs may have for the adoption of sustainable products (Baron 2011).

An additional driver of adoption is compatibility of a product and its producer with consumers’ values (Daghfous et al. 1999; Rogers 2003):

Compatibility is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters. An idea that is more compatible is less uncertain to the potential adopter, and fits closely with the individual’s life situation. Such compatibility helps the individual give meaning to the new idea so that it is regarded as familiar. (Rogers 2003, p. 224)

As we argued in our theoretical framework, this is particularly relevant due to the importance of the underlying understanding of shared cosmopolitan values to the sustainable business model. Moreover, previous research has linked product development and consumer adoption with cosmopolitan mindsets (Riefler et al. 2012; Robertson and Wind 1983). Consumers who are likely to adopt new products are “cosmopolitan in outlook, tend to be better educated, willing to take risks, and are more socially mobile than their peers” (Wright and Charlett 1995, p. 33). These conceptual connections between moral cosmopolitanism and adoption are based on shared underlying moral cosmopolitan values and beliefs as argued by Emontspool and Georgi (2017), who connect moral cosmopolitanism with the adoption of innovative food practices in a global qualitative study.

In the following section, we develop a hypothesis-based model of sustainable product adoption. The model introduces consumer perceptions of a firm’s sustainability engagement and its engagement with NGOs as determinants of adoption, and thereby considers the interactions of consumers, firms, and NGOs. As additional determinants, we consider consumers’ attitudes toward these two levels of engagement. In line with adoption theory, we argue that consumers may perceive sustainability engagement and NGO engagement as signals that reduce uncertainty regarding the product’s sustainable qualities and thus stimulate adoption. The corresponding attitudinal concepts positively influence adoption as they reflect value compatibility. We develop this in more detail in the following section.

Sustainability Engagement

Our theoretical framework suggests that cosmopolitan firms accept responsibility that extends beyond their own firm’s interest and beyond their local communities, considering the impact that the firm has through its activities on people and the environment anywhere on the globe, today and in the future (Held 2009). This understanding is in line with recent work that sees corporate sustainability as a global obligation (Arenas and Ayuso 2016; Brown et al. 2016; Jamali 2016). Cosmopolitan firms may perform activities that contribute to sustainability goals such as considering the social welfare of humans, protecting the planet, and contributing to prosperity for all. We thus consider consumer perceptions of a firm’s sustainability engagement (sustainability engagement) as a variable in our model.

One challenge for consumers in the process of adopting sustainable products is that the sustainability quality of the product is a credence quality, i.e., one that cannot be observed or experienced but needs to be believed. In line with this understanding, adoption theory suggests that measures that limit consumers’ uncertainty about the qualities of the new product may encourage adoption (Rogers 2003). We argue that firms’ sustainability engagement signals to consumers that claims regarding a product’s sustainability characteristics, such as its production conditions or its environmentally friendly product components, are credible. To the consumer it thus seems more plausible that the product in question actually has the promised cosmopolitan sustainability qualities. Such risk reduction may then lead to increased adoption. We expect that sustainability engagement reduces the risk that product-related sustainability claims are untrue and as a consequence, consumers are more likely to adopt. This argument is in line with research that has established that a firm may stimulate positive behavioral responses from consumers by engaging in corporate sustainability (Sen et al. 2016). We thus hypothesize:

H1

The stronger the sustainability engagement, the greater the sustainable product adoption.

In addition to consumers’ perception of sustainability engagement, we consider consumer attitudes toward firms’ sustainability engagement (sustainability attitudes). While sustainability engagement is a perception, sustainability attitude reflects consumers’ personal attitudes and values. Morally cosmopolitan consumers are likely to care about the impacts of their consumption on global humanity (Grinstein and Riefler 2015), and we thus assume that consumers’ sustainability attitudes reflect cosmopolitan values. Sustainable consumption has in this context been specified as a means to express one’s values, beliefs, and ultimately one’s self as a moral cosmopolitan consumer (Naderi and Strutton 2015). Considering that compatibility of values and beliefs is a driver of product adoption (Rogers 2003), one should thus assume a positive association between sustainability attitudes and sustainable product adoption. Moreover, the underpinnings of cosmopolitan values are in line with product adoption (Lim and Park 2013).

Our argument is in agreement with research that has identified consumer attitudes toward firm behaviors as important predictors of adoption (Moreau et al. 2001). More specifically, various studies have established that consumers with a positive attitude toward corporate sustainability and a willingness to reward good corporate sustainability performance are more likely to purchase sustainable products (Bhattacharya and Sen 2004; Meijer and Schuyt 2005; Moosmayer 2012; Paul et al. 1997). And more recently, Chipulu et al. (2015) have highlighted the importance of personal values for consumer response to firm behavior. This supports our consideration of congruent cosmopolitan values that underlie consumers’ attitude toward both sustainability engagement and a firm’s sustainable products as an important driver of adoption. We thus hypothesize:

H2

The stronger the sustainability attitude, the greater the sustainable product adoption.

Firm–NGO Engagement

From a cosmopolitan point of view, NGOs gain their relevance from voicing concerns in support of groups who may be unable to represent themselves effectively, including those who literally have no voice, such as non-human species, the environment, and future generations (Heins 2008). And firms, particularly those with a cosmopolitan mindset, might seek to engage with civil society partners who can help resolve sustainability challenges that are related to such groups without voice (Ruggie 2008). Firm–NGO engagement, as exemplified in multi-stakeholder dialogues (Grosser 2016; Høvring et al. 2016), may thus be an indicator for the credibility of sustainability claims that accompany sustainable products. Therefore, firm–NGO engagement may reduce consumer uncertainty regarding the sustainability of a product.

Moreover, civil society groups together with firms have been found to be important to consumers in their responses to sustainability concerns (Caruana and Chatzidakis 2014). NGOs are well known as “watchdogs” that monitor corporate behavior (Dubbink et al. 2008), often demanding greater corporate accountability, especially through highly publicized actions. By the same token, NGOs also work together collaboratively with firms to tackle social problems in actions that are similarly often publicized (Frig et al. 2016). Consumers pay attention to NGO criticisms of firms and to how firms respond to NGOs (Yaziji and Doh 2009). We thus consider consumer perceptions of a firm’s interaction with and responsiveness to NGOs (firm–NGO engagement) when exploring sustainable product adoption.

Firm–NGO engagement is important as it has been established that firms often perform symbolic actions, rather than undertaking substantive measures that effectively improve social and environmental conditions (Berrone et al. 2009; Li et al. 2017). This is particularly relevant as sustainability qualities are “credence qualities,” which consumers can usually not assess but have to believe (Darby and Karni 1973). In this context, Caruana and Chatzidakis (2014) described one important function of NGOs as mediators who improve the availability and quality of objective corporate sustainability information. Such third-party confirmation of the information could effectively reduce the adoption risk, for instance with a known label certifying that a product is free of child labor (De Chiara 2016; Gosselt et al. 2017). Such certification is often provided and communicated through civil society groups, highlighting the potential importance that NGOs may have for the adoption of sustainable products (Baron 2011; Darnall et al. 2016). We argue that based on NGOs’ critical as well as constructive function in interacting with firms, firms’ interaction with and responsiveness to NGOs is perceived by consumers as a signal that increases the credibility of product-related sustainability claims beyond the effects of specific labels. We hypothesize:

H3

The stronger the firm–NGO engagement, the greater the sustainable product adoption.

In addition to the influence of firm–NGO engagement, which we derived from the relevance of uncertainty reduction in adoption theory, we also consider consumer attitudes toward firms’ interaction with and responsiveness to NGOs (firm–NGO attitude), which as we will argue, may influence adoption through value compatibility. Research has identified consumer attitudes toward firm behaviors as important predictors of adoption (Moreau et al. 2001). We conceptualize this for firms’ engagement with NGOs. We connect to cosmopolitan consumer characterizations as open-minded with an appreciation of diversity and reduced ethnocentrism (Riefler et al. 2012). Similarly, research has connected product adoption to high cultural openness (Nijssen and Douglas 2008), which seems compatible with the idea of a global cosmopolitan community. By engaging with NGOs, firms can thus signal to consumers that they and their products are compatible with these cosmopolitan ideas. “Such compatibility helps the individual give meaning to the new idea so that it is regarded as familiar” (Rogers 2003, p. 224). The importance of compatibility in values and beliefs for the adoption of products is widely acknowledged (Daghfous et al. 1999) and may be particularly relevant for sustainable products. Rogers (2003)’s argument that value compatibility drives adoption is further supported by research establishing consumption as a means through which consumers exercise moral cosmopolitan values and beliefs (Emontspool and Georgi 2017; Naderi and Strutton 2015) and work by Lim and Park (2013) that positively connects cosmopolitanism with adoption in a sample of 350 South Korean consumers. We thus hypothesize:

H4

The higher the firm–NGO attitude, the greater the sustainable product adoption.

Controls: Satisfaction and Trust

To ensure that our results are not caused by the omission of traditional marketing variables, we control for the influence of satisfaction and trust (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002; Mittal and Kamakura 2001). Satisfaction can be generically understood as a comparison of consumers’ experiences with their expectations (Oliver 1980, 2014). Product expectations and experience are developed in relation to a products’ various characteristics (Cordell 1997), and brand purchase and willingness to buy have been connected to satisfaction with the brand (Cardozo 1965). Similarly, Kotler and Armstrong (2016) suggest that customer satisfaction is a key determinant of brand choice. Trust is a further factor that determines if consumers will consider the product of a brand that they have patronized before (Morgan and Hunt 1994). It has been found that trust leads to behavioral brand loyalty, i.e., a consumer’s intention to repurchase the brand in question (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001; Lau and Lee 1999). This also applies to choices of new models and products of the same brand. In addition to controlling for the influence of these two marketing concepts, we also include a consumer’s prior use of the product category and the socio-demographic variables: gender, age, and income as controls.

Methods

Context of the Study: Sustainable Sportswear in China

Cosmopolitan Values in China

China might at first glance seem an unlikely place for cosmopolitan values (Webb 2016). A large and internally extremely diverse country, it is well known for having a strong state that allows relatively little social space for other political actors. Civil society groups such as NGOs are heavily regulated (Johnson 2011), particularly foreign organizations (Wong 2016), as are the press and social media (deLisle et al. 2016). Nevertheless, there are signs of developing cosmopolitan values in China, most notably among consumers and civil society groups. As Chinese consumers become more affluent, many engage in aesthetic cosmopolitan consumption, including taking overseas trips and purchasing foreign products (Yu 2014). Moreover, there are also some indications of a growing environmental awareness among Chinese consumers (Kikuchi-Uehara et al. 2016), which may signal their moral cosmopolitan values.

In addition, expressions of cosmopolitan attitudes are not limited to consumer behavior. Most strikingly, Chinese people have in recent years become aware of NGOs and now overwhelmingly trust such groups. In the Edelman Trust (2016) global survey of trust in NGOs and other organizations, Chinese citizens were ranked the second-most trusting in NGOs globally. Particularly with regard to environmental issues, new and increasingly visible NGOs are working to educate Chinese consumers about the environmental impact of their consumption habits (Xie 2011; Yang 2010). Some of these groups have run many campaigns in China to inform the public about the environmental pollution records of many well-known Chinese and international brands and their suppliers (Lee et al. 2012).

Li Ning as an Example of a Cosmopolitan Chinese Firm

We test our hypotheses in the context of Chinese consumers’ adoption of a sustainable product introduced by Chinese sportswear brand Li Ning. This is in line with research that finds that cosmopolitan consumers use clothing to express themselves (Gonzalez-Jimenez 2016). It therefore seems justified to assume that cosmopolitan consumers may wear clothing and accessories that reflect their aspiration to be globally sustainable.

Li Ning is a brand named after its founder, the gold medal-winning Olympic gymnast who became a hero in China as a result of his performance in the 1984 Olympic Games. The firm has in recent years expressed an increasingly cosmopolitan orientation in its corporate sustainability discourse. Moreover, as the firm has risen in global prominence, it, along with competing sportswear brands such as Adidas and Nike, has attracted the criticism of environmental and labor rights NGOs for production processes that allegedly put the environment and workers at risk and violate their rights (Greenpeace 2011; Maquila Solidarity Network 2008). Greenpeace’s high-profile, industry-wide campaign to eliminate certain chemical inputs in the textile and garment industry addressed major brands including Li Ning and has been analyzed in various scholarly publications (Brennan and Merkl-Davies 2014; Brennan et al. 2013; Davis and Moosmayer 2014). In response to such campaigns, Li Ning has engaged with civil society groups (Friends of Nature et al. 2012a, b; Li Ning 2012, 2013; Tan 2011). Additionally, the company has joined industry initiatives aimed at improving environmental standards in the global textile industry by reducing the use of hazardous inputs (Li Ning 2011; Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemical Programme (ZDHC) 2012). Li Ning’s communication and engagement with environmental NGO groups has been evaluated positively [Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE) and Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) 2014], but some have argued that the firm has not gone far enough in releasing information to the public (Greenpeace 2016).

Parallel to its engagement with NGOs, the company has also addressed cosmopolitan concerns by extending its product lines to include sustainable products made from recycled fibers.Footnote 1 In 2009, Li Ning became the first Chinese firm to adopt the Eco-circle closed loop technology for production and use of recycled polyester fibers (Teijin 2013). That year, the firm introduced its Eco-circle line of products made with such recycled textiles. The firm has engaged in other efforts to introduce sustainable inputs into its products and has received industry awards for this work (e.g., Li Ning 2015). We use this context to test our hypotheses that aim to understand consumer adoption of sustainable products in a cosmopolitan framework.

Approach and Sample

In order to test our model of adoption and to understand what determines consumers’ willingness to purchase a sustainable product, we developed a paper-and-pencil-based survey study. We collected consumer data applying a mall intercept method (Bush and Hair 1985) in the city center of a Chinese costal second-tier city (5–10 million inhabitants, GDP per capita of around 12,000 USD p.a.). Respondents were invited to participate in the research and informed that there were no right or wrong answers, that non-participation had no negative consequences, and that participation was entirely voluntary. Moreover, anonymity was assured as no names or other identifying information was collected. This procedure is required by the ethical guidelines of the institution where the research was conducted and also is an important procedural remedy used to reduce evaluation apprehension and thereby control common method variance (CMV) (Podsakoff et al. 2003, p. 888).

We collected a total of 217 complete answers. Respondents had an average age of 30.7 years and reported an average income of 50,000 RMB (~ 7200 USD), and 48% were female. Given strong population growth followed by the one-child policy, this overrepresentation of men and people between 18 and 30 seems to reflect Chinese society well. Moreover, it seems to represent a relevant target group for sportswear purchases. In fact, 42% of the respondents reported participating in sports regularly (multiple times a week), while 30% said they engaged in sports about once a week and only 28% seldom did sports. We considered potential influences of these socio-demographic variables by using them as controls in the analyses below.Footnote 2

Measures

We measured sustainable product adoption by borrowing from the behavioral loyalty measure and applying it to sustainable products. The items that we apply refer to the scale by Baker and Churchill (1977) and capture both adoption by new users (e.g., “I would like to try this Eco-circle clothing series”) and also by consumers who may have purchased the brand before (“I would actively seek out this Eco-circle clothing series in Li Ning’s store in order to purchase it”). The attempt to integrate these two aspects in one measure is supported by the construct’s reliability. (See Cronbach’s alpha scores on the diagonal of Table 1.)

To measure sustainability engagement, we applied the “CSR associations” items by Brown and Dacin (1997) including “Li Ning has a concern for the environment.”Footnote 3 To measure sustainability attitude, we used the “willingness to reward” dimension by Creyer and Ross (1997; Items 2, 4, and 5), including the sample item “Given a choice between two firms, one ethical and the other not especially so, I would always choose to buy from the ethical firm.”

For firm–NGO engagement and firm–NGO attitude, we developed two measures reflecting consumers’ perception and expectation of companies’ engagement with NGOs. The scale concept and item wording were developed in discussion with three academic experts in the fields of organizational behavior, marketing, and political studies. Firm–NGO engagement was measured with the items “Li Ning is responding well to claims from non-governmental organizations (NGOs),” “Li Ning collaborates with non-governmental organizations,” and “Li Ning reacts responsibly when approached by non-governmental organizations.” Firm–NGO attitude was measured with the items “Companies should respond to non-governmental organizations,” “Companies have a responsibility to react to claims from non-governmental organizations,” and “When non-governmental organizations discover environmental violations by companies, these companies should collaborate with the NGOs to resolve them.”

Our satisfaction measure builds on Mano and Oliver (1993) and represents a global satisfaction measure, which we chose because the components of satisfaction were not of interest in the current study. An example of the four items used is: “I am satisfied with my decision to buy Li Ning’s sport clothing product.” We measured trust in the brand as proposed by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) using a four-item measure including sample items such as “I trust this brand” and “I can rely on this brand.”

The survey instrument was translated into Chinese applying back-translation (Johnson, 1998) followed by refinement using a team approach (Harkness and Schoua-Glusberg 1998) with the goal of producing items that were functionally equivalent to the original. During this process, great care was taken to ensure that translations were easy to understand and free of ambiguities in order to limit CMV (Podsakoff et al. 2012, p. 551). Chinese item wording is available from the authors. All measures are listed in Table 1 with their means, standard deviations, and correlations.

Analyses

An exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation using an eigenvalue of 1 as the cutoff criterion produced the expected 7-factor solution extracting 73.2% of variance in the data. Table 1 provides an overview of these seven constructs. The reliability measure Cronbach’s alpha of all latent constructs is displayed on the diagonal of Table 1. The measures exceeded the recommended .7 threshold except for the sustainability attitude measure that can still be considered acceptable at .67 (Hair 2009; Nunnally 1978). Acceptable fit criteria [χ2 (231, N = 217) = 437.9, p < .001; CFI = .93, TLI = .91; RMSEA = .064] in the confirmatory factor analysis provide further support for our measurement model. At this point, we applied Harman’s single-factor test, the first statistical measure suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003), in order to identify a potential effect of CMV on the measurement model. The single-factor solution extracted only 31% of the variance, i.e., less than half of the extracted solution, thus suggesting that CMV does not threaten the results (Harman 1976).

We established construct validity by applying the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion for discriminant validity that investigates whether the squared correlation of each pair of constructs is smaller than the product of these constructs’ average variance extracted. Moreover, significant path loadings of all items on their constructs (at p < .001) indicate convergent validity (Gerbing and Anderson 1988).

We tested our hypotheses performing a three-step hierarchical regression using SPSS 24.0 (Table 2). At step 1, we first tested influences of the controls. We then included sustainability-related constructs at step 2 and NGO-related constructs at step 3.

Results

At the first step, we found the marketing-related controls of satisfaction (b = .42; p < .001) and trust (b = .33; p < .001) are significantly positively associated with sustainable product adoption. Moreover, none of the four socio-demographic control variables of sportswear usage, gender, age, or income were significantly related to adoption. For the controls, this result was consistent at all steps. At the second step, we added sustainability engagement and sustainability attitude. In line with our hypotheses, sustainability attitude (b = .19; p < .01) had a significant positive influence on sustainable product adoption, thus supporting hypothesis 2. By contrast, sustainability engagement (b = .11; p > .05) was positively but not significantly associated with sustainable product adoption, thus suggesting rejection of hypothesis 1.

At step three of the analysis, we included perspectives on firm–NGO engagement. The structure of the results here was the reverse of that for sustainability engagement: Firm–NGO engagement (b = .30; p < .001) was significantly positively associated with sustainable product adoption, thus supporting hypothesis 3. In contrast, firm–NGO attitude (b = .001; p > .05) was not significantly associated with sustainable product adoption and had a regression coefficient marginally different from zero, thus not providing support for hypothesis 4. The variance in sustainable product adoption explained by our models increased from .38 at step 1 to .42 at step 2 and to .48 at step 3, and adjusted R2 increased accordingly. In order to assess the potential influence of CMV on our regression results, we modeled a single unmeasured latent method factor (excluding category usage, gender, and age) as suggested as a fourth statistical remedy by Podsakoff et al. (2003). We found that the inclusion of this factor did not have a substantive influence on our results: All significance levels were maintained and no regression weight changed by more than ten percent of its value.

Discussion

We explored how sustainability considerations regarding firms and NGOs influence the adoption of sustainable products. We asked (A) whether a firm’s sustainability engagement influences consumers’ choice to adopt sustainable products and (B) whether a firm’s engagement with non-governmental organizations influences consumers’ choice to adopt sustainable products. We found that sustainability attitude and firm–NGO engagement explain sustainable product adoption,Footnote 4 while sustainability engagement and firm–NGO attitude do not. In the following sections, we discuss the contributions of our study: (1) We contribute to the sustainable consumption debate by distinguishing between consumers’ response to product sustainability on the one hand and firm sustainability on the other. We thereby develop a more nuanced understanding of how attitudes and perceptions may or may not influence adoption behaviors that can help explain gaps between what consumers say and what they do. (2) We contribute to the sustainability reporting and assurance discussion by considering NGOs’ influence on consumers in ways that go beyond the watchdog role generally attributed to such organizations. We find that consumers may be influenced by the social relationships that they perceive between firms and NGOs which can operate independently of sustainability reporting. (3) We contribute to an understanding of cosmopolitan tendencies in business contexts in China. Our results indicate that Chinese consumers may respond to various aspects of the relationships between firms and NGOs, suggesting a more fine-grained view on Chinese actors’ responses to cosmopolitan initiatives. Finally, we discuss the limitations of our study and identify implications for research in general, the business ethical debate in particular, and for management.

Consumer Response to Firm and Product Sustainability: Understanding Different Kinds of Intentions

We connected to the debate about sustainable consumption and more specifically the question of whether consumers show a positive market response to sustainability. We identified two different types of market response explored in prior research: the adoption of products with sustainable characteristics (Luchs and Kumar 2017) and the willingness to reward firms that engage in sustainability more generally, or rather in forms that are less directly connected to a specific sustainable product, such as paying fair wages or engaging in corporate philanthropy (Van Quaquebeke et al. 2017). We connected these two types of market response by considering firms’ sustainability engagement and consumers’ related attitudes as determinants of sustainable product adoption.

We found that consumers who have a willingness to reward such engagement are more willing to adopt sustainable products. Interestingly, however, we did not find a direct influence of firm sustainability engagement on adoption. Put another way, consumers with a positive attitude toward sustainability reward sustainability by adopting sustainable products, but they do so independently of the producer’s sustainability engagement. These findings may contribute to a better understanding of the widely discussed intention–behavior gap in sustainable consumptionFootnote 5 (Devinney et al. 2010; Hassan et al. 2016). Our findings suggest that part of the gap might result from exploring excessively broad intentions. In our sample, consumer sustainability attitude explains adoption, but firms’ sustainability engagement does not. One may see this as the gap between consumers’ intention to reward sustainable firms and their failure to purchase more sustainable products when firms have strong sustainability engagement. However, a closer look clarifies that that it is firm–NGO engagement, i.e., a specific type of sustainability engagement, which is rewarded by consumers with purchase behaviors. This suggests two interpretations.

First, rather than supporting corporate sustainability in general, consumers may want to support cosmopolitan firm behaviors in line with their personal values and beliefs, e.g., a cosmopolitan-minded engagement with civil society rather than a donation to a cause determined by the firm. This value compatibility-related interpretation is in line with our theoretical cosmopolitan framework and corresponds with the analysis of Sen et al. (2016), who include the relevance of sustainability-firm fit in their review of consumer responsiveness to sustainability. It further supports Chipulu et al. (2015)’s finding that personal values are most influential for consumer behaviors toward companies.

Second, congruent with Carrington et al. (2010)’s conceptual distinction of generic “intentions” and more specific “implementation intentions,” and in line with Govind et al. (2017)’s view on “explicit” verbalized and “implicit” behaviorally relevant sustainability attitudes, consumers may form broad intentions, which translate into narrower implicit implementation intentions. For example, consumers’ intention to support sustainability engagement could translate into the intention to purchase a sustainable shirt (which is not the case in our study) or to specifically support firms that demonstrate sustainability through their engagement with NGOs (which is the case in our study). By explicitly distinguishing between consumers’ response to a sustainable product and to the producer’s engagement with sustainability in general and with NGOs in particular, we thus identified relevant nuances about how attitudes and perceptions may or may not influence adoption behaviors. Our interpretation suggests that the often-discussed intention–behavior gap might sometimes be better described as a gap between different levels of intentions.

Firm–NGO Relationships: A Neglected Influence in Sustainability Reporting and Assurance

We developed a moral cosmopolitan framework and pointed out that cosmopolitan thinking shares with sustainability an assumption of responsibility to others independent of their location and citizenship. Our framework integrates cosmopolitan views on consumers (Grinstein and Riefler 2015), firms (Crane et al. 2008; Ghemawat 2011), and civil society groups (Macdonald and Macdonald 2010), and we used it as a foundation to argue for a model that explores the influences of firms’ sustainability engagement and their engagement with civil society actors on consumer adoption of sustainable products.

We found that sustainability attitude and firm–NGO engagement were significantly positively associated with adoption. This supports the basic logic of adoption theory assuming the relevance of both risk reduction (which we used to argue for the engagement constructs) and value compatibility (which we used to argue for the influence of the attitudinal constructs). Moreover, increases in R2 from .38 to .42 and to .48 when adding the consideration of corporate sustainability and NGO engagement show that we actually understand adoption of sustainable products better when considering these characteristics. This is particularly noteworthy for NGO engagement, which has been broadly explored with regard to firms (Kourula and Delalieux 2016; Moosmayer and Davis 2016), but to the best of the authors’ knowledge, has rarely been integrated from a consumer perspective. It is therefore striking that the increase in both R2 and R 2ad when including civil society is greater than when including corporate sustainability.

A core issue discussed in the literature is that consumers find it difficult to obtain and interpret sustainability information provided by firms and translate it into sustainable purchase decisions (Longo et al. 2017). These challenges have resulted in research considering what sustainability information should be provided to consumers, and in what form (Comyns 2016; Haller et al. 2016; Lu and Abeysekera 2017). Because consumers often do not know if information is credible, prior research has suggested verification through reports and labels (Dendler and Dewick 2016; Hummel et al. 2017), with a role for NGOs as neutral players in assuring the quality of sustainability claims (Darnall et al. 2016; Hsueh 2016; Sethi et al. 2017). Our findings suggest an additional perspective: NGOs may also influence consumer perceptions through activities that do not involve monitoring firms or verifying firm claims. The fact that consumers perceive firms to engage effectively with NGOs is sufficient to positively influence consumers’ adoption of sustainable products. We argued that firms’ NGO engagement sends a signal that reduces consumers’ uncertainty regarding a product’s sustainable features. In other words, consumers may base their adoption decision on the social relationships that they perceive between firms and civil society players, suggesting that for these consumers, the actions or deeds of the company and NGO may be more important than their words.

Corporate Sustainability in China: Where Discerning Consumers Trust NGOs

With our study, we further contribute to understanding cosmopolitan engagement in China. We do not find a direct positive effect of sustainability engagement on product adoption (thus not supporting hypothesis 1), which could be seen as an expression of skepticism toward Chinese firms’ sustainability claims as these are often more symbolic than substantial (Li et al. 2017). As a result of such skepticism, consumers may seek signals that a firm’s efforts are genuine. These are the kinds of signals which may be provided by firms’ engagement with NGOs, thus resulting in support for hypothesis 3. This is further supported by prior research that describes a role for NGOs in increasing the availability of credible information (Darnall et al. 2016; Doorey 2011). This function may be particularly useful in China, where the substantive content and transparency of many Chinese corporate sustainability reports are rather limited (Gong et al. 2016; Marquis and Qian 2013).

The findings that Chinese consumers do respond to firm–NGO engagement but not to firms’ sustainability engagement suggest that Chinese consumers are discerning cosmopolitans. Prior research has established that consumers who are interested in sustainability are generally more willing to try new, cosmopolitan products (Emontspool and Georgi 2017; Riefler et al. 2012). However, Chinese cosmopolitans may feel that they must be particularly vigilant in order to distinguish true cosmopolitan claims from those of unethical firms. As a result, they are not focused on firms’ words and claims regarding sustainability in general. Instead, consumers may use their perceptions of firm engagement with civil society organizations as an indicator of firms’ deeds. This engagement is thus the more important factor influencing consumers’ willingness to purchase sustainable products. By engaging with NGOs, firms prove that their claims have substance, and provide a signal to consumers. This supports findings of Western research on sustainability reporting that suggest that NGOs may contribute to making firms more sustainable (Frig et al. 2016) and that NGOs’ impartiality may make them credible for consumers (Sethi et al. 2017). With regard to China, however, results suggest that earlier studies indicating little expectation of firm–NGO engagement (Chi 2011; Yin and Zhang 2012) need to be replaced with a more fine-grained view. Consumers’ response to firm–NGO engagement reflects developing cosmopolitan values in China that may be a cause and an effect of civil society groups. We find that NGOs help support cosmopolitan consumption decisions. Our results are thus in line with the Edelman Trust (2016) global survey of trust in NGOs and other organizations, which ranked Chinese citizens as second-most trusting in NGOs globally.

Limitations

We tested our model with single-source survey data, and results may thus be affected by CMV (MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2012). On the one hand, we applied procedural remedies to limit CMV in the design and data collection phase (e.g., comprehensible and unambiguous item wordings and assurances of respondent anonymity as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2012)). In addition to observing meaningful non-correlations in the data that indicate that CMV is unlikely (e.g., between sustainability engagement and sustainability attitude), we further applied statistical remedies such as Harman’s (1976) single-factor test and modeling a single unmeasured latent method factor in the regression model (Podsakoff et al. 2003). On the other hand, additional measures could be applied in future research to address the issue of CMV. While we consider some remedies such as balancing positive and negative items as not advisable in a Chinese context due to language characteristics, separating the collection of dependent and independent variables would certainly add value. In particular, it would be promising to connect attitudinal measures collected from consumers with behavioral data in order to strengthen the validity of the identified effects. This could, for example, be achieved by deriving the dependent variable through experimental manipulations, or, even better, by surveying consumers who have just bought an item of sportswear from either a sustainable or a traditional product line. An additional but related limitation is that all variables are self-reported. Answers may thus be subject to a social desirability bias (SDB) that occurs when questions are strongly normative. For instance, when respondents perceive strong normative pressure for environmental protection and use of recycled materials, they might over-report their intention to adopt sustainable products. Because we analyzed relational results, such effects would bias the results mainly if they differed between respondents. Future research might remedy SDB by measuring consumers’ tendency to provide biased answers [e.g., through the scale by Crowne and Marlowe (1960)]. In addition, Podsakoff et al. (2012) recommend including marker variables that are unrelated to the constructs of interest. Both SDB and marker scores can be used to apply covariance-based approaches to eliminate the biases from the data.

We collected data through a mall intercept procedure in a central shopping area in a second-tier city in China. While the city was chosen based on the location of the researchers’ academic institution, its population appears reasonably representative of those living in economically well-developed Chinese tier-one and tier-two cities. In addition, our mall intercept approach in the city center may have led to an overrepresentation of people who shop in central locations at stores targeting affluent populations. Furthermore, by inviting respondents to participate in a study about their sportswear purchases, self-selection may have biased our sample toward consumers with a stronger interest in the product category. Our sample may thus have a high portion of buyers as compared to non-buyers in the specific product category. However, we aimed to control for this influence with the “category usage” control variable, and while there was a positive influence (.107 at step 3), it remained insignificant at each step.

An additional limitation results from the choice of our empirical case of Li Ning. We chose this firm because the brand is ubiquitously known in China; it is a home brand and thus not influenced by respondents’ country-of-origin perceptions, and Li Ning has both been a target of NGO criticism and has worked cooperatively with NGOs in the past. Moreover, the brand offers both traditional sportswear and the more sustainable Eco-circle product line, thus making the choice to switch from a traditional to a sustainable product without the need to patronize a different brand very realistic. However, this specific case naturally could involve influences that may limit the generalizability of our research to different contexts.

Implications

Research Implications

A set of research implications results from the limitations mentioned above, including further studies that connect survey data with actual consumer behaviors, for instance by observing such behaviors. Moreover, future research might replicate similar studies in different contexts in order to explore the generalizability of our findings. Future research could therefore test a similar model in different empirical populations. This would contribute to our understanding of how context influences sustainable product adoption. In addition, a product’s country of origin, as well as the NGO’s country of origin may influence consumer expectations regarding NGO engagement. For instance, Chinese consumers’ feelings about NGO engagement might vary depending on whether a foreign firm engages with a local or foreign NGO, or further, whether a local firm engages with a local or foreign NGO.

Similarly, different product categories are associated with different types of sustainability-related problems and these may influence consumers’ response to different levels of NGO engagement. For example, garments in general, and sportswear products in particular, have been the focus of NGO campaigns for many years now, and consumers connect the products, NGOs, and various environmental and labor-related sustainability challenges. By contrast, firms in other industries that have not been the target of NGO criticism may not evoke such connections for consumers. Moreover, our findings result from a study in China, and future research should explore if the unexpected effect of NGOs also holds true in Western contexts, where consumers have access to better sustainability information.

In the sustainable consumption context, we found that consumers who say they are willing to reward sustainable firms will adopt sustainable products, but they do so independently of the general sustainability of the firm. This finding together with other work distinguishing specific aspects of consumer attitudes and intentions suggests that future research should consider how attitudes and intentions which may appear to be quite similar do or do not translate into corresponding behaviors. In the context of the sustainability reporting and assurance debate, we argued for the importance of social relationships between firms and NGOs in a sustainability context. Future research might investigate the influences of additional social relationships on sustainability, for example how social relationships between firms and other stakeholders in sustainability reporting and assurance such as local communities or even sustainability auditing organizations influence the perceptions of producer and product sustainability.

Finally, with regard to cosmopolitan engagement in China, our finding that NGOs may influence the consumer–firm relationship is in line with other research that has found that consumers trust in civil society organizations such as NGOs (Edelman Trust 2016). However, when referring to the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations 2016) as a motivation for our research, we neglected one very important actor: the government. Because of the special role the government plays in China, future studies should include a governmental perspective when exploring how firms, consumers, and civil society can support sustainability.

Implications for the Business Ethics Debate

In some ways, the positive impact of firms’ NGO engagement on consumers’ perceptions of firms is the converse of the negative impacts firms suffer when they are associated with the unethical actions of suppliers in their supply chains. Just as consumers may attribute negative qualities to a brand that is found to have an unethical supplier in its supply chain, they may similarly associate positive qualities with the same firm when it works effectively with a critical NGO. This suggests a sort of halo effect that can be achieved by fostering good social relations with critical organizations. This effect leads to various business ethical implications.

Many people find it difficult to make good ethical consumption choices (Longo et al. 2017). Even when consumers have a positive attitude toward sustainable products and want to consume responsibly, they may feel unable to do so independently as they lack the expertise to assess firm claims. Our results suggest that consumers may use firms’ engagement with NGOs as a means of deciding whom to support. For firms, this may open up an additional form of ethically questionable behavior, as managing consumer perceptions of effective firm–NGO engagement could be seen as a new type of green-washing that allows firms to achieve business success without sincere attempts to operate more sustainably.

For NGOs, this result may suggest ethical dilemmas and may place additional obligations on these organizations to carefully consider which firms to work with. This might be obvious with regard to collaborative actions such as firm–NGO partnerships: When an NGO works cooperatively with a firm, NGO activity may appear to be an endorsement of the firm’s values and behavior (Baur and Schmitz 2012). However, this caution may also be necessary when NGOs engage in more critical, watchdog-like activities (Yaziji and Doh 2009). This is because even conflictual NGO actions such as negative publicity campaigns could potentially be perceived as effective firm–NGO engagement if the firm appears to respond appropriately to NGO criticism. Put another way, NGO criticisms that provide an opportunity for firms to engage with the organizations could ultimately benefit the companies if consumers perceive that the firms are working well with their NGO critics. This may suggest the need for clearer ethical guidelines for firms on how to work with NGOs. Industry-wide self-regulation of business–NGO engagement may be just one potential way to structure this field for the future.

Practical Implications

For firms, our observation that consumers respond to the “deeds” of sustainable products rather than “words” about general firm sustainability engagement has an interesting and promising implication: Firms may benefit from their sustainability initiatives, even if they have had a generally poor sustainability record in the past. In addition, firms need to better understand how to effectively work together with NGOs as such engagement sends a relevant signal to consumers. In particular, a lack of responsiveness to NGOs or arguing with them should be avoided as acknowledging claims and taking a collaborative stance is more likely to be rewarded by consumers. More broadly, our results support the findings of research suggesting that in order to successfully bring sustainable products to market, firms need effective non-market strategies (Doh et al. 2015) that define firm relationships with civil society groups.

For civil society organizations, the results imply on the one hand that NGOs should reflect more carefully on how consumers perceive their collaboration with firms. By giving consumers the impression that they are working with a particular firm, NGOs might appear to endorse a firm’s behaviors even though their general stance toward the firm is critical. On the other hand, NGOs can use our findings to encourage firms to be more collaborative, as we provide evidence that firms benefit from behaviors that signal to consumers an effective engagement with civil society groups.

Conclusion

Although perhaps not widespread, cosmopolitan orientations can be observed in some Chinese firms and in consumer attitudes. However, given the recent history of corporate scandals and unsustainable behavior, Chinese consumers may be more discerning of sustainability claims than expected. Chinese cosmopolitans may feel that they must be particularly vigilant in order to distinguish true cosmopolitan claims from those of unethical firms.

In such a context, firms might aim to signal sustainability through reporting initiatives. However, as noted above, such reporting in China may not be characterized by as much transparency as in some other contexts, and consumers may feel that the words in reports alone may not allow them to judge firms’ cosmopolitan engagement. By contrast, consumers in China may be willing to use firms’ NGO engagement as a crucial indicator of their cosmopolitan deeds.

Notes

While environmental concerns may initially appear to be relatively local, choices about materials and other conditions in textile and garment production actually do affect the global environment. For example, Greenpeace has shown that chemicals used in Chinese factories may be released in rivers elsewhere in the world when the Chinese-produced imported clothing is washed in the countries of consumption (Greenpeace 2011). In other words, certain persistent chemicals are exported to global waterways together with clothing exports.

For the purpose of analysis, we coded this variable 1 (less than once per week), 2 (about once per week), and 3 (multiple times per week) and treated it as a continuous variable for further analyses. We did so as it did not influence the results, but the precise treatment as an ordinal variable would have substantially limited the analytical methods we could apply.

We applied measures that in their item wording cover the broad array of issues that are reflected in our understanding of sustainability, particularly the fields of ethics and responsibility, and integrating aspects of economic, social, and environmental sustainability.

One might argue that neglected moderation effects could explain these results, i.e., that engagement (sustainability engagement and firm–NGO engagement) affects adoption, but only if there is a positive attitude (sustainability attitude or firm–NGO attitude). However, we explored this possibility in additional analyses and considered potential moderation effects by including the product term of the related constructs (Baron and Kenny 1986; Edwards and Lambert 2007). To do so, we normalized all latent construct variables in order to avoid effects of resulting nonessential multicollinearity (Cohen et al. 2013). However, the influences of both product terms: sustainability engagement x sustainability attitude and firm–NGO engagement x firm–NGO attitude, were not significant and adding these did not change the significance level or magnitude of the results presented in Table 2.

The theory of reasoned action (Fishbein 1980) established the predictive power of attitudes for behavior. The theory of planned behavior improved this relationship by including intentions as mediators between attitudes and behavior (Ajzen 1991). We discuss the intention–behavior gap which suggests that consumers form intentions but may not subsequently perform the corresponding behavior. This gap thus also increases the distance between attitudes and behaviors as attitudes may not be followed by corresponding behaviors. Consistent with common terminology, we discuss the “intention–behavior gap” although strictly speaking our study refers to an attitude–behavior gap.

Abbreviations

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- CMV:

-

Common method variance

- M:

-

Variable mean

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- RMSEA:

-

Root-mean-square error of approximation

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis index

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a world of strangers. New York: WW Norton.

Archibugi, D. (2008). The global commonwealth of citizens: Toward cosmopolitan democracy (Vol. 6). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press.

Arenas, D., & Ayuso, S. (2016). Unpacking transnational corporate responsibility: Coordination mechanisms and orientations. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(3), 217–237.

Baker, M. J., & Churchill, G. A. J. (1977). The impact of physically attractive models on advertising evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(4), 538–555.

Baron, D. P. (2011). Credence attributes, voluntary organizations, and social pressure. Journal of Public Economics, 95(11), 1331–1338.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Baur, D., & Schmitz, H. P. (2012). Corporations and NGOs: When accountability leads to co-optation. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 9–21.

Beck, U. (2006). The cosmopolitan vision. Cambridge: Polity.

Berrone, P., Gelabert, L., & Fosfuri, A. (2009). The impact of symbolic and substantive actions on environmental legitimacy. In IESE research papers (Vol. No D/778). Barcelona: IESE Business School Universidad de Navarra.

Beschorner, T., & Hajduk, T. (2017). Responsible practices are culturally embedded: Theoretical considerations on industry-specific corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(4), 635–642.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review, 47(1), 9–24.

Boiral, O., Heras-Saizarbitoria, I., & Brotherton, M.-C. (2017). Assessing and improving the quality of sustainability reports: The auditors’ perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3516-4.

Bookman, S. (2013). Branded cosmopolitanisms: ‘Global’ coffee brands and the co-creation of ‘cosmopolitan cool’. Cultural Sociology, 7(1), 56–72.

Brennan, N., & Merkl-Davies, D. (2014). Rhetoric and argument in social and environmental reporting: The dirty laundry case. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 27(4), 602–633.

Brennan, N. M., Merkl-Davies, D. M., & Beelitz, A. (2013). Dialogism in corporate social responsibility communications: Conceptualising verbal interaction between organisations and their audiences. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(4), 665–679.