Abstract

In this article, we demonstrate that individuals use motivated reasoning to convince themselves that their self-serving behavior is justified, which in turn affects the distribution of resources in business situations. Specifically, we explore how ambiguous contextual cues and individual beliefs can jointly form motivated reasoning. Across two experimental studies, we find that whereas individual ideologies that endorse status hierarchies (i.e., social dominance orientation) can strengthen the relationship between contextual ambiguity and motivated reasoning, individual beliefs rooted in fairness and equality (i.e., moral identity) can weaken it. Our findings contribute to person–situation theories of business ethics and provide evidence that two ubiquitous factors in business organizations—contextual ambiguity and social dominance orientation—give rise to motivated reasoning, enabling decision makers to engage in self-serving distributions of resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Reasoning was designed by evolution to help us win arguments.

(Mercier & Sperber, 2011)

High-stake decisions in business involve some type of resource allocation. Even though decision makers strive to comply with fairness expectations when distributing resources (Allison and Messick 1990; Messick 1993; Rutte et al. 1987), there are myriad exceptions. Indeed, examples of employees taking more than their fair share are ubiquitous in modern organizational contexts. Some of the most notorious—such as the 2012 trader nicknamed the “London whale” who was responsible for a $2 billion loss—come from the housing bubble that arose during a period of market flux and high-risk, opaque hedging strategies. Perpetrators of these actions often claim that they were entitled to these resources (Rosenblatt 2012), and experimental research confirms that decision makers who take more resources for themselves at the expense of others believe that they have earned the right to do so (e.g., De Cremer and van Dijk 2005; Hoffman and Spitzer 1985; Samuelson and Allison 1994). We propose that feeling entitled to a larger share of a resource might come not from objective assessments of reality, but rather from motivated reasoning, which occurs when people “selectively notice, encode, and retain information that is consistent with their desires” (Grant and Berry 2011, p. 73).

In the last decade of research in behavioral business ethics, scholars have moved away from a “bad apples” approach in which only people with poor moral characteristics are likely to behave unethically, to approaches that consider how people can engage in self-serving behaviors while convinced of the rightness and fairness of doing so (Moore and Gino 2015; Shalvi et al. 2015; Treviño et al. 2006). As the opening quote suggests, people can use their reasoning to reach a conclusion that helps them support their self-serving beliefs. Few studies, however, have explored the circumstances in which motivated reasoning related to self-serving behavior is likely to arise. This is surprising given that individuals need to maintain the “illusion of objectivity,” and thus, their ability to reach the conclusion they want to reach is constrained by beliefs prior to the motivational factor (Kunda 1990).

Grounded in theories of situational strength (cf. Mischel 1973), we propose that the interaction of certain contextual and individual characteristics will facilitate motivated reasoning that is aimed at justifying self-serving decisions. We posit that contextual ambiguity (i.e., weak contextual cues that are represented by ambiguous claims to a resource) can lead to motivated reasoning. Moreover, we predict that an ideology possessed by individuals often in charge of distributing resources—that of social dominance orientation (SDO) (Sidanius and Pratto 1999; Pratto et al. 1999; Rosenblatt 2012)—enhances the relationship between weak contextual cues and motivated reasoning aimed at justifying self-serving behavior. In other words, because SDO is associated with superiority and entitlement, we expect it to heighten the relationship between contextual ambiguity and motivated reasoning. Finally, we posit that even though contextual ambiguity can drive motivated reasoning, this effect will be moderated by characteristics of the decision maker related to his or her moral identity (Aquino and Reed 2002). Specifically, we hypothesize that the decision maker’s moral identity can mitigate the effect of weak contextual cues on motivated reasoning.

Theoretical Rationale and Hypotheses

Motivated reasoning is the mostly unconscious process of cognitively reframing information to ensure consistency between one’s beliefs or desired outcomes and decisions (for reviews see Kunda 1990; Molden and Higgins 2005). Take, for example, a set of studies conducted by Ditto and colleagues (Ditto and Lopez 1992; Ditto et al. 1998, 2003) that purportedly tested participants’ health; the participants in these studies looked for evidence that would confirm, and rejected evidence that disconfirmed, healthy medical results. Some research also suggests that motivated reasoning can be used to mitigate the self-condemnation, dissonance, and/or guilt that would result from behavior with ethical and/or harmful implications for others (Tsang 2002), that is, self-serving behavior, which “results in benefits for the self at the expense of others” (Dubois et al. 2015, p. 437). For instance, people tend to rationalize sweatshop labor through motivated reasoning when their desires are self-serving, such as the need to purchase garments produced with sweatshop labor (Paharia et al. 2013).

Although self-serving behavior is not always considered unethical (Dubois et al. 2015), it has been linked to ethical standards in organizations (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014). For this reason, scholars have argued that more research should address this type of behavior, particularly the “thinking behind individuals’ self-interested pursuits” (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014, p. 267). It is interesting to note, in this regard, that the distribution of resources in which self-interest is involved presents two competing motives for decision makers. On the one hand, decision makers want to profit from being self-serving; on the other, they want to see themselves and be seen by others as fair and honest (Shalvi et al. 2015). Drawing on theories of motivated reasoning (Kunda 1990), we posit that decision makers can interpret the context in a way that justifies their self-serving behavior to maintain an image of themselves as good and selfless people (e.g., Ditto et al. 2009; Mazar et al. 2008; Shalvi et al. 2015).

In resource allocation dilemmas, we posit that individuals might come to view themselves as being entitled to a larger share of a resource due to, for example, having outperformed the other party, even if this is not the case. In the past, scholars have shown that when individuals believe a given trait leads to academic or business success, they come to view themselves as possessing that trait more than other people (Dunning et al. 1989; Kunda and Sanitioso 1989). Based on this literature, we posit that when decision makers contemplate the possibility of engaging in a self-serving resource allocation (i.e., keeping more for themselves at the expense of others), they will convince themselves they deserve a larger share of that resource than others, thereby justifying their self-serving behavior.

H1

Motivated reasoning that justifies deserving more than others will increase an individual’s tendency to engage in self-serving resource allocation.

We are referring here to motivated reasoning and not moral disengagement, although the two are theoretically related (Paharia and Dehspandé 2009; Paharia et al. 2013). Moral disengagement is generally viewed as a dispositional trait that reflects a tendency to reframe unethical/harmful acts to make them appear right (Detert et al. 2008; Moore et al. 2012). Some scholars have referred to situational moral disengagement to address moral disengaging rationalizations that arise due to self-interest in specific situations (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014); this is theoretically closer to the construct of motivated reasoning. We do not refer, however, to the rationalizations that individuals use to disengage their moral standards, but rather to the reasoning that decision makers use to convince themselves that they are entitled to a larger share of a resource. In other words, we refer to the process by which decision makers reconstrue information provided by the environment so as to make it fit their desired conclusion that they are more deserving than others.

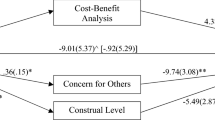

Next, we propose a person–situation interactionist perspective to examine the effects of certain contextual and individual characteristics on motivated reasoning. This approach has been unexplored in empirical research despite its recognized importance (e.g., Kish-Gephart et al. 2010; Treviño 1986). Specifically, we study motivated reasoning in the distribution of resources, a common activity performed by organizational members that has important ethical implications (Garcia et al. 2009; Keatings and Dick 1989; Reynolds et al. 2006). We posit that whereas motivated reasoning can arise from the combination of contextual ambiguity and individual characteristics such as SDO, other individual characteristics, such as the decision maker’s moral identity, can weaken the relationship between contextual ambiguity and motivated reasoning. Figure 1 summarizes our conceptual model.

The Effect of Contextual Characteristics on Motivated Reasoning

As Kunda (1990, p. 484) stated, motivated reasoning ensures that “attitudes can become more positive or somewhat more negative than the attitude that one would report in the absence of motivation, but it is unlikely to completely overturn existing attitudes.” In line with person–situation models of ethical behavior (Treviño 1986), we propose that motivated reasoning will be facilitated or constrained by the interaction of certain attitudes of the decision maker and contextual characteristics related to the distribution of resources. We apply the situational strength person–situation perspective (Mischel 1973; Meyer et al. 2010) to develop our hypotheses.

Situational strength is the notion that strong contextual cues restrict the expression of certain individual characteristics (Meyer et al. 2010). According to this theory, individual characteristics are more likely to manifest when the context is “weak” than when the context is “strong” (Mischel 1973). In the context of motivated reasoning, we propose that strong situations are those in which there is clear, unambiguous information about claims to a resource. Conversely, weak situations are those in which the information about claims to a resource is ambiguous and allows individuals to interpret that information in a self-serving manner.

When information about claims to a resource is ambiguous, decision makers need to engage in constructive, substantive information processing to determine how to use that information; in other words, they need to go beyond the information provided by the environment to reach a conclusion (Forgas 1995). For this reason, ambiguity has been found to lead to the interpretation of information in a manner that is congruent with the perceiver’s current mood (Forgas 1995) and to numerous decision-making biases (Camerer and Weber 1992).

Scholars have also found that the ability to engage in motivated self-assessments is possible only to the extent that relevant skills and behaviors are ambiguously defined. The more ambiguously these qualities are presented, the more individuals can adopt a definition that would allow them to convince themselves that they do or do not possess them (Dunning et al. 1989). Additionally, ambiguous performance credentials help individuals feel justified in rejecting applications of out-group members against whom they are prejudiced (Esses et al. 2014). Conversely, when information is unambiguous, decision makers should have less opportunity to reconstrue that information so as to arrive at self-serving conclusions. Thus, ambiguity represents a weak context, which we propose will give rise to motivated reasoning that justifies self-serving behavior in resource distribution dilemmas.

H2

Contextual ambiguity will increase motivated reasoning aimed at justifying a self-serving resource allocation.

The Moderating Role of SDO

Resource allocation decisions are often influenced by the ideologies of the decision maker (Pratto et al. 1999). Ideologies are “action schemas that influence social behavior, including resource allocation and social relations” (Pratto et al. 1999, p. 128). SDO captures “the degree to which individuals desire and support group-based hierarchy and the domination of ‘inferior’ groups by ‘superior’ groups” (Sidanius and Pratto 1999, p. 48). We focus on this ideology because people high in SDO tend to occupy positions of power, to study business and/or economics (Martin et al. 2015), and are often in charge of allocating resources (Rosenblatt 2012). For these reasons, it is important to understand the interaction of SDO with contextual ambiguity and motivated reasoning.

Previous research has linked SDO with the tendency of people to disengage from their moral obligations (Jackson and Gaertner 2010) and to be less likely to recognize that a situation involves a misuse of power and can harm others (Rosenblatt 2012). In resource allocation dilemmas, individuals who endorse SDO tend to allocate more resources to dominant than to subordinate groups (Pratto et al. 2006; Rosenblatt 2012) and to see performance claims as the most legitimate means to allocate resources (Pratto et al. 1999). Additionally, SDO represents the belief of individuals that they (and members of their in-group) are more deserving of and should have greater access to positive social values, such as power, recognition, and money (Rosenblatt 2012). As such, SDO has been linked to feelings of entitlement and to cognitive mechanisms that rationalize disparities between groups (Jost and Hunyady 2005). Extending these findings to the domain of motivated reasoning in self-serving behavior in resource allocation decisions, we propose that SDO will enhance individuals’ tendency to convince themselves that they deserve a larger share of a resource than others in the presence of ambiguous contextual cues.

H3

Social dominance orientation (SDO) will enhance the relationship between ambiguous contextual cues and motivated reasoning.

The Moderating Role of Moral Identity

Person–situation scholars in social psychology argue that the subjective interpretation of the same situation can differ depending on individual differences in construct accessibility (Higgins, King and Mavin 1982). For instance, research has demonstrated that only those people who previously held prejudiced beliefs tend to use contextual ambiguity to justify discriminatory hiring practices (Esses et al. 2014). In our research, we propose that the accessibility of constructs related to fairness and equality—made salient by the decision maker’s moral identity—will moderate the relationship of contextual ambiguity with motivated reasoning.

Moral identity is the degree to which people find that being moral and honest is an integral part of their identity (Aquino and Reed 2002; Blasi 1984). Scholars have conceptualized this as the mental representation of how individuals’ internal moral character is expressed externally through behavior (Aquino and Reed 2002; Winterich et al. 2013). In support of this definition, moral identity has been related to a variety of ethical behaviors, including reduced unethical and increased prosocial acts (see Shao et al. 2008 for a review). Decision makers who have a central moral identity also engage in equitable allocation of resources by, for example, favoring the out-group as much as the in-group (Reed and Aquino 2003). Finally, moral identity has been found to reduce at least some type of rationalizations, such as those related to the cognitive mechanisms that people use to justify war (Aquino et al. 2007). Overall, people with a central moral identity are likely to attend to cues related to the morality of a situation (Leavitt et al. 2016; Reynolds and Ceranic 2007; Xu and Ma 2016).

By making constructs related to equity and fairness accessible to individuals, we expect that moral identity will diminish the interpretation of contextual ambiguity to mean that one deserves a larger share of a resource than others, that is, to engage in self-serving motivated reasoning.

H4

Moral identity will moderate the relationship between contextual ambiguity and motivated reasoning.

Overview of Empirical Studies

We explore our hypotheses through two experimental studies: one using a hypothetical business decision-making scenario and the other using a behavioral task in the laboratory. To test our propositions, we experimentally manipulate contextual ambiguity by assigning participants to conditions in which they received either identical performance information with respect to another party (strong, unambiguous context), or in which they and the other party were favored by different performance criteria (weak, ambiguous context). In the latter case, participants can use motivated reasoning to convince themselves that their own performance criterion is more relevant for the task at hand, thereby convincing themselves they deserve a larger share of the resource. We measure their SDO and moral identity to test our moderating hypotheses.

Study 1

In Study 1, we placed our participants in a managerial role and asked them to advice on a bonus allocation decision. We manipulated contextual cues by giving participants different information about their own performance and that of another manager competing for the same resource (a bonus). Participants were then asked to report the perceived importance of each performance criterion and to recommend a resource distribution based on that information.

Sample and Procedure

Participants were 395 business students (52% women, Mage = 23.24, SD = 4.13, Mwork_experience = 2.68, SD = 3.60). Study 1 was conducted as a two-wave online experiment. Each wave lasted approximately 20 min, and participants were eligible to win a prize.

In the first wave, participants completed a questionnaire of construct scales including SDO, moral identity, and control variables. In the second wave, participants were presented with a case study (adapted from Diekmann et al. 1997) that contained our experimental manipulations and asked to make a decision about dividing a bonus between themselves and the other person. The case study described a scenario in which participants were newly appointed branch managers of KATA Bykes. They received information about the firm’s background and structure and were introduced to Mr. Bolen, another new branch manager. Participants were then told that they and Mr. Bolen would have to make a series of important decisions over the next two years that could determine how much of a €100,000 bonus they would receive. After reading background information on product focus, production area, and marketing (see Diekmann et al. 1997), participants were given information about their and Mr. Bolen’s performance in terms of net income and market share.

Participants were randomly assigned to one cell out of a 3 (Performance Conditions = Superior Market Share, Superior Net Profit, and Identical Claims) X 2 (Need Conditions = Equal Need, Higher Need) experimental design. Whereas the first condition was designed to manipulate contextual ambiguity in the claims to the resource, we included the latter condition to control for the possibility that financial needs would interact with any of our hypothesized relationships.

Performance Conditions: Manipulation of Context

In the Superior Market Share condition, participants were told that their branch had achieved a higher market share than the other division (9.4 vs. 6.6%), but a lower net income (€4.33 million vs. €5.33 million). In the Superior Net Income condition, participants were given the opposite statistics: they had achieved superior net income, but lower market share than Mr. Bolen. In the Identical Claims condition, participants were told that they and Mr. Bolen had achieved the same results for both market share and net profit.

The first two conditions represent weak/ambiguous contextual cues that facilitate motivated reasoning since participants can select the self-favoring criterion as the more important one to determine the allocation of the bonus. For instance, participants in the Superior Market Share condition could decide that market share is more important than net profit, and thus allocate a larger percentage of the bonus to themselves. Participants in the Superior Net Profit condition could instead reach the conclusion that net profit is a more important determinant of performance than market share. Thus, these two conditions together allow us to test for motivated reasoning since there is no reason to believe that participants randomly assigned to these two conditions would reach these conclusions about the superiority of the self-favoring criterion in the absence of motivation.Footnote 1 However, participants in the Identical Claims condition would not be able to convince themselves that they deserved a larger share of a resource, since claims to the resource are entirely unambiguous.

Need Condition

Previous research has shown that people allocate resources based on one of the two main criteria: performance and need concerns (Pratto et al. 1999). To control for the possibility that financial needs could play a role in the resource allocation decision and interact with our Performance Conditions, we included a manipulation of Mr. Bolen’s financial needs. As such, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two Need Conditions. Participants in the Equal Need Condition were told that both their branch and Mr. Bolen’s were in affluent areas of the country, and had plenty of resources available for future investments and bonuses. In the Higher Need Condition, participants were told that Mr. Bolen’s branch was operating in a rather poor area, with very limited resources for further investments and little possibility of future bonuses.

Allocation Recommendation

Participants were shown the following scenario: “You have just received a call from the president of the company, who has requested your input on how this year’s bonus pool should be allocated between you and Mr. Bolen. This year’s bonus pool for the two new branch managers is €100.000. You have known the president for many years and he trusts the objectivity of your opinion. You feel strongly that his decision will be based on your recommendation. In view of information previously provided about you and Mr. Bolen, please provide a recommendation to the president of the company on what percentage of the bonus to allocate to Mr. Bolen. (The rest of the bonus will then be allocated to you).”

Participants were then asked to choose the percentage of the bonus pool they would recommend Mr. Bolen should receive (from 0 to 100%), which constitutes our continuous measure of self-serving behavior.

Measures

Manipulation Checks

After participants made the allocation recommendation, a series of questions was asked to ascertain whether participants had correctly understood the case, including whether they had achieved a better market share, whether they had achieved a better net profit, and whether they had more financial resources than Mr. Bolen. Participants in the Superior Market Share condition understood that they had achieved a better Superior Market Share than Mr. Bolen, compared to participants in the other two conditions, F = 1145.08, p < .001. Similarly, participants in the Superior Net Profit understood that they had achieved a better net profit than Mr. Bolen, compared to participants in the other two conditions, F = 1175.44, p < .001. Finally, participants in the Higher Need Condition understood that they had better financial resources compared to Mr. Bolen, F = 548.59, p < .001. These results confirm that participants correctly understood the information provided in the case and their relative standing compared to Mr. Bolen.

Social Dominance Orientation

We assessed participants’ SDO with Pratto et al.’s (1994) 16-item scale (M = 2.83, SD = 0.97, Cronbach’s alpha = .89).

Moral Identity

We measured the centrality of participants’ moral identity with Aquino and Reed’s (2002) 10-item Self-Importance of Moral Identity Scale (M = 4.83, SD = 0.83, Cronbach’s alpha = .79).

Motivated Reasoning

In order to determine whether participants engaged in motivated reasoning, we assessed whether participants concluded that they had outperformed the other manager. Thus, we asked participants the degree to which they agreed with the following statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree): “My performance was superior to that of Mr. Bolen.” As compared to the Identical Claims condition, we expected participants in either of the conditions in which claims to the resource were ambiguous to conclude that they had performed better than Mr. Bolen. This would be evidence that they used motivated reasoning to convince themselves the self-favoring criterion was the most important to determine superior performance.

Control Variables

At the end of the study, participants completed a series of items including demographic questions (about gender, nationality, work experience, and age) and were debriefed. In addition to demographic questions, we controlled for participants’ tendency to morally disengage with Moore et al.’s (2012) 16-item scale (M = 2.79, SD = 0.88, Cronbach’s alpha = .88). We controlled for the possibility that participants’ tendency to disengage their moral standards when making decisions would affect our model given that moral disengagement has been previously related to self-interested reasoning (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014; Paharia et al. 2013) and to SDO (Jackson and Gaertner 2010).

Results

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics of motivated reasoning and self-serving behavior in Study 1. Motivated reasoning illustrates the degree to which people believed they performed better than the other party, which constitutes our measure of motivated reasoning. Self-Allocation is the amount that participants allocated to themselves (100% minus Mr. Bolen’s bonus).

Self-Serving Behavior

A 3 × 2 ANOVA revealed a main effect of Performance and Need Conditions on the bonus allocation decision. The Need Condition was included only to control for the possibility that it would interact with our main variables of interest; given that these interactions were not found to be significant, we account for Need as a covariate in the statistical analyses. The effect of the Performance Condition on self-serving behavior was significant; F(1, 385) = 10.65, p < .001, η 2p = .05. Planned contrasts revealed that having any type of ambiguous performance claims, provided by either the Superior Market Share or superior net income, significantly increased self-serving resource allocations as compared to the Identical Claims condition, in which claims were entirely unambiguous, t(306) = −3.40, p < .001. Being assigned to the any of the two conditions in which information was weak/ambiguous (Superior Market Share or Superior Net Profit) did not make a difference in participants’ allocation decision, t(256) = −0.07, p = .95. These results suggest that participants randomly assigned to any of the ambiguous conditions used motivated reasoning to justify a self-serving allocation. Next, we measured whether the Performance Condition indeed influenced these justifications.

Motivated Reasoning

There was a main effect of the Performance Condition on motivated reasoning; F(1, 385) = 200.82, p < .001, η 2p = .51. There were significant differences between participants in the “Identical Claims” with participants in both of the conditions in which claims to the resource were ambiguous (Superior Market Share, p < .001, and Superior Net Profit; p < .001). Conversely, there was no difference in motivated reasoning between participants who believed they had performed better in market share and participants who believed they had performed better in net profit (the two conditions representing ambiguous contexts); t(256) = .811, p = .42. These results provide evidence of motivated reasoning since, as previously discussed, there is no reason to believe that participants in these two conditions would find the self-serving criterion as more important to determine performance in the absence of motivation to behave self-servingly. Conversely, participants in the “Identical Claims” condition in which claims to the resource were entirely unambiguous did not reach the conclusion that they had outperformed the other party. This provides evidence for H2, in which we proposed contextual ambiguity to facilitate motivated reasoning aimed at justifying self-serving behavior.

In line with H1, we found that motivated reasoning about deserving more than others (self-better beliefs) made people feel entitled to a self-serving resource allocation, ß = .453, p < .001, and that such motivated reasoning mediated the relationship between contextual ambiguity and self-serving behavior; index = 3.23, 95% CI [2.49, 4–15]. Next, we explore the person–situation interactions that facilitated or prevented such motivated reasoning by testing for the interactions between contextual ambiguity and moral identity and SDO, respectively.

Person–Situation Interaction of Motivated Reasoning

We conducted a bootstrapping analysis with 5000 resamples to test the moderated mediation model entering SDO as the moderator (H3), as well as contextual ambiguity as the independent variable, motivated reasoning as the mediator, and self-serving behavior as the dependent variable (and controls and moral identity as covariates). As expected, the moderated mediated model was significant, index = 0.45, 95% CI [0.09, 0.87]. In line with H3, the interaction between contextual ambiguity and SDO in predicting motivated reasoning was significant, t = 2.87, p < .023. In short, SDO moderated the role of contextual ambiguity on motivated reasoning: the likelihood of people to use contextual ambiguity to convince themselves they had outperformed the other party increased as their SDO increased.

We conducted a second bootstrapping analysis with 5000 resamples (Preacher et al. 2007) to test the second moderated mediation model, entering the Performance Condition as the independent variable, motivated reasoning as the mediator, self-serving behavior as the dependent variable, and moral identity as the moderator (as well as the control variables and SDO as covariates). As expected, the moderated mediated model was significant, index = −0.56, 95% CI [−1.03, −0.17]. In line with H4, the interaction between contextual ambiguity and moral identity was significant in predicting motivated reasoning (t = −2.67, p = .008). These results reveal that the likelihood of people to use contextual ambiguity to convince themselves they had outperformed the other party decreased as the centrality of their moral identity increased.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 support our main propositions that motivated reasoning facilitates self-serving resource allocations, and that such motivated reasoning results from a dynamic interplay of contextual and individual characteristics. Specifically, we found that SDO enhanced the tendency to engage in self-serving motivated reasoning in the presence of contextual ambiguity. We also found that although contextual ambiguity enabled individuals to engage in motivated reasoning to feel entitled to take more resources for themselves at the expense of others, high moral identifiers were less likely to use contextual ambiguity to reach this self-favoring conclusion. Thus, Study 1 provides the initial support for predictions in a hypothetical decision-making scenario. Although behavioral intention often parallels actual behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975), we expand our findings in Study 2 by assigning a behavioral task to assess actual motivated reasoning and actual self-serving resource allocations to test our hypotheses.

Study 2

The main goal of Study 2 was to replicate the results obtained in Study 1 by using a real-life resource allocation dilemma to assess motivated reasoning that aims at justifying a self-serving distribution of resources. We again tested our person–situation models by manipulating weak (ambiguous) contextual cues and measuring participants’ characteristics related to SDO and moral identity.

Participants and Procedure

Study 2 was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, 239 business students participated; 11 students failed to complete the second phase of the study, leaving a final sample of 228 participants. More than half (52.2%) of participants were female; 22.4% of the 228 were graduate students. Their average age was 23.65 (SD = 3.19), and their average work experience was 2.05 years (SD = 2.94).

In phase 1 of the study, participants came to the laboratory and were paid €5 for their participation. After completing measures of SDO and moral identity, as well as a few filler items, participants completed a performance task composed of five verbal and five math exercises (similar to those found on the GMAT). Participants created a secret ID that was matched to their email address so that they could be contacted for the second phase of this study; participants also selected a token from a box that would assign them to a condition in the second phase online.

Two weeks after the performance task, participants completed phase 2 of the study online. All participants who had completed the performance task in phase 1 were split into three groups according to their performance and were informed that there would be a drawing for €100 for each group. Within each group, participants were randomly paired up with another participant, who remained anonymous to them. Participants received 14 points; the number of points was equivalent to the number of times their email address would be entered into the lottery (thus, the more points, the more chances to win). Participants were told they had been randomly assigned to the role of “allocators” according to their token number (all participants were assigned to this role). As allocators, they needed to decide how the points should be allocated between themselves and their partner based on their relative performance. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three “Performance” conditions:Footnote 2

Better Math

Participants were told that they and their partner had performed equally well, but that they had performed better in the math section, and their partner had performed better in the verbal section. For example, participants were told they had achieved 60% of right answers in the math section and their partner had achieved 60% of right answers in verbal; the opposite information was provided in the Better Verbal condition.

Better Verbal

Participants were told that they and their partner had performed equally well, but that they had performed better in the verbal section, and their partner had performed better in the math section.

Equal Performance

Participants were told they and their partner had the same scores in both the math and verbal tasks.

The two first conditions represent weak/ambiguous contexts, in which participants could choose the self-favoring criterion as the most important to determine performance and to subsequently feel justified to take more resources for themselves. So the first two conditions are equivalent to the two ambiguous conditions of Study 1 (Superior Market Share and Superior Net Profit).

Measures

SDO and Moral Identity

We used the same scales employed in Study 1 to assess SDO (Cronbach’s alpha = .89) and the self-importance of moral identity (Cronbach’s alpha = .79).

Motivated Reasoning

After participants were informed about their performance in relation to their partners and were given a short reminder of what the math and verbal problems looked like, participants were asked to assess the difficulty of the problems along a categorical scale (0 = both math and verbal were equally difficult, 1 = the math section was more difficult than the verbal section, 2 = the verbal section was more difficult than the math section). Thus, rather than assessing whether participants thought they had outperformed the other party in general terms, as done in Study 1, participants in Study 2 reported which criterion they found to be more difficult and relevant to determine the resource allocation. If participants selected the self-favoring criterion as the more difficult and relevant, we would have evidence of self-favoring motivated reasoning.

Allocation Decision

Our dependent variable was participants’ distribution of points between themselves and their partner. Participants could allocate any of the 14 points (between 0 and 14) to their partner and keep the rest.

Control Variables

As in Study 1, participants completed a few demographic measures (gender, nationality, age, work experience, and level of academic studies), and the moral disengagement scale employed in Study 1 (Cronbach’s alpha = .89) as a control. Accordingly, our analyses include demographic variables and moral disengagement as control variables.

Results

Motivated Reasoning

Given that Study 2 employed a categorical measure to assess motivated reasoning, we first examined the percentage of participants in each of our experimental conditions that chose one of the following optional statements: “verbal and math problems were equally difficult”; “verbal problems were more difficult than math problems”; “math problems were more difficult than verbal problems.” A partial Chi-square analysis revealed that the differences across Performance Conditions in the selection of these statements were significant, X2(4) = 61.63, p < .001. As shown in Table 2, 64.9% of the participants in the Equal Performance Condition chose the option that states that both verbal and math problems were equally difficult. Conversely, 61.3% of the participants in the Better Math condition chose the option that states math problems were more difficult than the verbal problems. Finally, 44.7% of the participants in the Better Verbal condition chose the statement that the verbal problems were more difficult than the math problems, providing further evidence of motivated reasoning.

To sum up, participants were likely to convince themselves that math problems were more difficult when favored by the math criterion, to convince themselves the verbal problems were more difficult when favored by the verbal criterion, and to show no preference when favored by neither criterion. Thus, the results of Study 2 provide more concrete evidence of the type of motivated process that is taking place. Whereas Study 1 demonstrated that participants believed they had outperformed the other party, Study 2 provided evidence that people selected the self-favoring criterion as the most difficult and subsequently most reflective of better performance, which is how they were able to convince themselves that they had outperformed the other party.

Self-Serving Behavior

There was a main effect of the Performance Condition on self-serving allocation of points; F(1,215) = 5.70, p = .004, η 2p = .05. Due to the categorical nature of the mediator in Study 2 (and in line with Herr, undated; MacKinnon and Dwyer 1993), we conducted a logistic regression to test whether the difficulty assessments (our measure of motivated reasoning) mediated the relationship between the Performance Condition and self-serving allocation. The logistic regression revealed that the effect of the Performance Condition became nonsignificant (t = 1.83, p = .068) when accounting for motivated reasoning (t = 4.14, p < . 001), which provides evidence of mediation (MacKinnon and Dwyer 1993). These results demonstrate that motivated reasoning generated real self-serving allocation of resources, thus complementing the findings obtained in Study 1 and providing further support for H1 in which we proposed that motivated reasoning about deserving more than others increases self-serving resource allocations. Next, we explore the person–situation interactions that facilitated or prevented such motivated reasoning by testing for the interactions between contextual ambiguity and SDO and moral identity, respectively.

Person–Situation Interaction of Motivation Reasoning

We conducted a bootstrapping analysis with 5000 resamples to test the moderated mediation model entering SDO as the moderator (H3), as well as contextual ambiguity as the independent variable, motivated reasoning as the mediator, and self-serving behavior as the dependent variable (and moral identity and controls as covariates). The results were in line with those obtained in Study 1: the moderated mediated model with SDO as a moderator was significant, index = 0.24, 95% CI [0.08, 0.47]. In line with H3, the interaction between contextual ambiguity and SDO in predicting motivated reasoning was significant, t = 4.13, p < .001. In line with Study 1, these results revealed that the likelihood of people to use contextual ambiguity to convince themselves they had outperformed the other party increased with SDO.

We conducted an additional bootstrapping analysis with 5000 resamples (Preacher et al. 2007) to test the second moderated mediation model (H4) entering the Performance Condition as the independent variable, motivated reasoning as the mediator, self-serving behavior as the dependent variable, and moral identity as the moderator (as well as the controls and SDO as covariates). Unlike Study 1, the moderated mediated model did not reach significance, index = −0.13, 95% CI [−0.40, 0.05]. When we included only the internalization subdimension of moral identity and excluded the symbolization subdimension (as also done in prior research, e.g., Winterich et al. 2013), the moderated mediation model became significant, index = −0.23, 95% CI [−0.46, −0.07]. The interaction between contextual ambiguity and internalized moral identity was significant in predicting motivated reasoning (t = −3.35, p = .001). In other words, the likelihood of contextual ambiguity to result in the decision maker’s beliefs that they had outperformed the other party (and thus deserved more resources) decreased as the internalized moral identity of those decision makers increased. This gives partial support to H4, while suggesting that it is the internalization (and not the symbolization) dimension is driving these results.

Discussion

Study 2 replicated the findings of Study 1 using a real decision-making scenario. We once again demonstrated that ambiguity—in this case, ambiguous and conflicting performance results after a real performance task—is a weak context in which individuals convince themselves that they deserve more resources than others, a form of motivated reasoning that in turn facilitated their self-serving behavior. Consistent with Study 1, we also demonstrated that SDO enhanced the tendency of individuals to engage in self-serving motivated reasoning in the presence of contextual ambiguity. In contrast to Study 1, in Study 2 we found high moral identity internalization mitigated the effect of contextual ambiguity on motivated reasoning, whereas high moral identity symbolization had not such attenuating effect. One explanation for this discrepancy is the use of a hypothetical task in Study 1 versus a real task in Study 2, which suggests that the lack of effect of the symbolization aspect of moral identity occurs when people have real stakes in the resource allocation. Because symbolization reflects the intention to appear moral and because motivated reasoning allows people to behave self-servingly while convinced of the fairness of their acts, it is possible that the people who have a high symbolized (but not internalized) moral identity are also likely to engage in motivated reasoning in the presence of ambiguity, particularly when the rewards of behaving self-serving are real and significant. For these reasons, we consider the results of Study 2 to be more reliable given the real nature of the resource allocation and estimate that the internalization dimension of moral identity is more likely to mitigate the effect of contextual ambiguity on motivated reasoning that justifies real self-serving behavior.

General Discussion

Our research demonstrates that people convince themselves they are more deserving than others in resource allocation dilemmas due to motivated reasoning. This type of reasoning results from a dynamic interplay of contextual and individual characteristics. We demonstrated that contextual ambiguity—a feature of many organizations (Leavitt et al. 2016)—facilitates the reinterpretation of information so that decision makers believe themselves entitled to take a larger share of a resource. Moreover, whereas ideologies possessed by people who are often in charge of the distribution of resources in organizations (SDO) can enhance this effect, characteristics of the decision maker related to his or her moral identity can attenuate this relationship. Taken together, our examination suggests that organizations may unwittingly promote motivated reasoning that convinces people of the fairness and rightness of their self-serving acts, a problem that can be addressed by increasing the centrality of the decision maker’s moral identity.

Theoretical Implications

Our paper advances person–situation models related to business ethics, which scholars have long argued hold the most promise for understanding phenomena related to ethics in organizations (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010; Knoll et al. 2016; Miska et al. 2016; Stahl and Sully de Luque 2014). Within the context of motivated reasoning and self-serving resource allocations, we demonstrated that contextual ambiguity constitutes a weak context that generates motivated reasoning in resource allocation dilemmas. We expand on models of situational strength (Mischel 1973) by showing that individual differences can exacerbate or compensate for weak contexts.

We also contribute to theory and research on moral identity, which has been found to be an important antecedent of ethical behavior (Shao et al. 2008). To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first to demonstrate that moral identity can mitigate the role of weak/ambiguous contexts on motivated reasoning that justifies a self-serving resource allocation. Additionally, our results suggest that this mitigating role is driven by the internalization dimension of moral identity, not by the symbolization dimension. Unlike the more private dimension of internalization, moral identity symbolization involves public displays of actions that convey a commitment to moral ideals and goals (Aquino and Reed 2002). It is thus possible that the symbolization dimension did not prevent motivated reasoning since motivated reasoning conveys the impression (to oneself and others) of being an ethical and fair person regardless of the selfishness of one’s (actual) behavior. These results also contribute to research finding that the internalization dimension of moral identity is a stronger predictor of moral behaviors than moral identity symbolization (e.g., Reynolds and Ceranic 2007; Winterich et al. 2013; Xu and Ma 2016).

More broadly, our research has significant implications on how the field of business ethics investigates contextual influences on decision making. Our theorizing is in line with the idea that individual morality is malleable and dynamic, and vulnerable to subtle contextual influences (Monin and Jordan 2009). In exploring how contextual ambiguities can prompt individuals to justify self-serving practices, we explain how and why situational cues can undermine fair allocation of resources even when decision makers strive to be fair and honest.

Practical Implications

This paper has important implications for organizations that intend to distribute its resources fairly, which is often expected and desired by both internal and external stakeholders (Reynolds et al. 2006). If we consider the centrality of a stakeholder management approach to business ethics (e.g., Freeman 1984; Dyer and Singh 1998), and the importance of balancing stakeholder interests when distributing resources (Reynolds et al. 2006), our findings underscore the need for managers to not only create systems and processes that incorporate a consideration of stakeholder needs and interests, but do so clearly, unambiguously, and consistently to prevent motivated reasoning from taking place. For instance, decision makers in organizations may be able to convince themselves that certain stakeholders are more deserving than others without realizing that they have reached such conclusions due to their motivated biases.

Our findings also suggest that organizations might inadvertently prompt employees to behave in self-serving ways given that the situations that are commonly present in organizations—contextual ambiguity and SDO—facilitate motivated reasoning that justifies those self-serving acts. Given that organizational realities are often fraught with ambiguity, our research offers a simple solution to prevent such ambiguity from resulting in motivated reasoning: ensuring that decision makers have a central (and internalized) moral identity. Additionally, given that previous research suggests that business and hierarchical organizations tend to place people with SDO in positions of power (Martin et al. 2015; Rosenblatt 2012), organizations need to realize that, by so doing, they may be inadvertently facilitating the relationship between contextual ambiguity and motivated reasoning.

It is also important to highlight that previous research has found that SDO and moral identity can be made more or less salient depending on the environment. For example, SDO was suggested to be enhanced by a competitive environment and beliefs (Cozzolino and Snyder 2008; Duckitt et al. 2002). Conversely, moral identity was found to be enhanced by a context that primes morality, but reduced by a context that emphasizes financial concerns (Aquino et al. 2009). These findings support our claim that organizations unwittingly facilitate motivated reasoning and self-serving behavior given that their environments emphasize competition and financial concerns. These findings are promising, however, in that organizations may not be limited to hire applicants with a central moral identity and low SDO, but may also focus on creating an environment in which SDO is reduced and moral identity is rendered salient.

Furthermore, our research has critically relevant implications to global, ethical business practices. The global context is recognized to increase ambiguity surrounding decision making and to present decision makers with more complex, multifaceted issues than domestic business contexts (Lane et al. 2004). As opposed to strong institutional environments existing in many economies at high levels of development, in many emerging and developing countries, institutional environments are weaker, involve arbitrary law enforcement, bureaucratic irregularities, and widespread corruption (Dobers and Halme 2009), all of which might reinforce the contextual ambiguity of situational cues. Organizations should give their employees clear guidelines for engaging in cross-cultural interactions to reduce contextual ambiguity, thereby producing a more holistic, comprehensive understanding of other global business contexts in which decisions are less susceptible to self-serving interpretations.

Limitations and Future Research

Our research suffers from the limitations of generalizability that are inherent in experimental design, which we selected due to the sensitive nature of our dependent variable and to address the hypothesized relationships in a controlled environment (cf. Griffin and Kacmar 1991). It is difficult to test interactions of this sort in a field setting (McClelland and Judd 1993), and the relationships between the variables addressed here had not been previously tested, for which reason it was important to set them apart from other confounding variables. Future research could benefit from addressing the interaction of managerial ideologies and moral identity with contextual cues related to the distribution of resources in field settings.

In this research, decision makers were tasked with a resource allocation decision in which they could claim part of the resources for themselves, which is in line with most of the research on resource allocation dilemmas (Diekmann et al. 1997; Messick 1993). Future research should explore our person–situation models in allocations that involve only third parties, since decision makers in organizations are often tasked with that type of resource allocations. In line with our findings, it is possible that contextual ambiguity leads people to resort to motivated reasoning by which they convince themselves their in-group deserves more resources than the out-group, and that moral identity diminishes this relationship, but SDO enhances it.

Furthermore, the present research investigated situations in which resources were distributed interpersonally, but not intertemporally. The addition of a temporal component could change the psychological dynamics of resource allocations (cf. Hernandez 2012). Research on intergenerational decision making has shown that individuals can be motivated to allocate resources to one or more people as a way to create a personal legacy (Wade-Benzoni et al. 2012). The desire to leave a positive legacy could serve as a different form of motivated reasoning such that when legacy motives are high, contextual ambiguity might prompt individuals to prioritize the needs of future others. The result would be less self-serving allocations and instead increased prosocial behavior.

Prior research has conceptualized strong contexts as those organizations that provide a solid ethical infrastructure, with clear and consistent ethical norms and cultures (e.g., Miska et al. 2016; Noval and Stahl 2017; Stahl and Sully de Luque 2014). We did not consider the ethical infrastructure as a strong contextual cue in the case of motivated reasoning, because the ethical infrastructure could only ensure that individuals do not knowingly commit ethical transgressions (Leavitt et al. 2016; Tenbrunsel and Messick 2004). Motivated reasoning, however, ensures that people transgress while convinced of the rightness of the transgressions. It would be worth exploring whether the contextual cues and individual characteristics we investigated in this research also interact with the organization’s ethical infrastructure in determining motivated reasoning that aims at justifying self-serving acts. If so, this would suggest that individuals remain at least partly aware that they are committing an act that might be disapproved of by the organization.

Finally, scholars should seek to explore whether the interaction of the variables we investigated in this paper between contextual ambiguity and individuals’ ideologies and identities determines other types of motivated reasoning. In this article, we focused on motivated reasoning aimed at rationalizing performance assessments, which served to convince decision makers that they were entitled to take more resources for themselves. Other forms of motivated reasoning have been found to facilitate self-serving behavior: for example, people are likely to use motivated reasoning to shift accountability for their actions (Ditto et al. 2009), to select moral principles that support desired conclusions for behavior (Uhlmann et al. 2009), and to convince themselves that others are different in order to feel comfortable behaving self-servingly at their expense (Noval et al. 2016). Future inquiry could explore whether an interaction between contextual ambiguity and individuals’ ideologies and/or identities also promotes or impairs such types of motivated reasoning.

Notes

Prior research (Diekmann et al. 1997) confirms that people, in the absence of motivation, see both of these conditions as equivalent in terms of performance.

Given that there was no significant interaction of the Need Condition with contextual ambiguity in Study 1, we did not manipulate the needs of the other party in Study 2.

References

Allison, S. T., & Messick, D. M. (1990). Social decision heuristics in the use of shared resources. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 3, 195–204.

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., Lim, V. G., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Aquino, K., Reed, A., Thau, S., & Freeman, D. A. (2007). A grotesque and dark beauty: How moral identity and mechanisms of moral disengagement influence cognitive and emotional reactions to war. Journal of Experiment and Social Psychology, 43, 385–392.

Blasi, A. (1984). Moral identity: Its role in moral functioning. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Morality, moral behavior and moral development (pp. 128–139). New York: Wiley.

Camerer, C., & Weber, M. (1992). Recent developments in modeling preferences: Uncertainty and ambiguity. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 325–370.

Cozzolino, P. J., & Snyder, M. (2008). Good Times, bad Times: How personal disadvantage moderates the relationship between social dominance and efforts to win. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1420–1433.

De Cremer, D., & van Dijk, E. (2005). When and why leaders put themselves first: Leader behavior in resource allocations as a function of feeling entitled. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 553–563.

Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 374–391.

Diekmann, K. A., Samuels, S. M., Ross, L., & Bazerman, M. H. (1997). Self-interest and fairness in problems of resource allocation: Allocators versus recipients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1061–1074.

Ditto, P. H., & Lopez, D. F. (1992). Motivated skepticism: Use of differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 568–584.

Ditto, P. H., Munro, G. D., Apanovitch, A. M., Scepansky, J. A., & Lockhart, L. K. (2003). Spontaneous skepticism: The interplay of motivation and expectation in responses to favorable and unfavorable medical diagnoses. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1120–1132.

Ditto, P. H., Pizarro, D. A., & Tannenbaum, D. (2009). Motivated moral reasoning. In B. H. Ross, D. M. Bartels, C. W. Bauman, L. J. Skitka, & D. L. Medin (Eds.), Moral judgment and decision making (pp. 307–338). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Ditto, P. H., Scepansky, J. A., Munro, G. D., Apanovitch, A. M., & Lockhart, L. K. (1998). Motivated sensitivity to preference-inconsistent information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 53–69.

Dobers, P., & Halme, M. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16, 237–249.

Dubois, D., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2015). Social class, power, and selfishness: When and why upper and lower class individuals behave unethically. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(3), 436–449.

Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., du Plessis, I., & Birum, I. (2002). The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual process model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 75–93.

Dunning, D., Meyerowitz, J. A., & Holzberg, A. D. (1989). Ambiguity and self-evaluation: The role of idiosyncratic trait definitions in self-serving assessments of ability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1082–1090.

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23, 660–679.

Esses, V. M., Bennett-Abuyyash, C., & Lapshina, N. (2014). How discrimination against ethnic and religious minorities contributes to the underutilization of immigrants’ skills. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 55–62.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The Affect Infusion Model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 39–66.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Garcia, S. M., Bazerman, M. H., Kopelman, S., Tor, A., & Miller, D. T. (2009). The price of equality: Suboptimal resource allocations across social categories. Harvard PON working paper No. 1442078. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1442078.

Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective-taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 73–96.

Griffin, R., & Kacmar, K. M. (1991). Laboratory research in management: Misconceptions and missed opportunities. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12(4), 301–311.

Hernandez, M. (2012). Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship. Academy of Management Review, 37(2), 172–193.

Herr, N. A. (undated). Mediation with dichotomous outcomes. Accessed on January 31, 2017 from http://www.nrhpsych.com/mediation/logmed.html.

Higgins, E. T., King, G. A., & Mavin, G. H. (1982). Individual construct accessibility and subjective impressions and recall. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(1), 35–47.

Hoffman, E., & Spitzer, M. L. (1985). Entitlements, rights, and fairness: An experimental examination of subjects’ concepts of distributive justice. Journal of Legal Studies, 14, 259–297.

Jackson, L. E., & Gaertner, L. (2010). Mechanisms of moral disengagement and their differential use by right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation in support of war. Aggresive Behavior, 36(4), 238–250.

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of system-justfying ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(5), 260–265.

Keatings, M., & Dick, D. (1989). Ethics and politics of resource allocation: The role of nursing. Journal of Business Ethics, 8, 187–192.

Kish-Gephart, J., Detert, J., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V., & Martin, S. (2014). Situational moral disengagement: Can the effects of self-interest be mitgated? Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 267–285.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31.

Knoll, M., Lord, R. G., Petersen, L. E., & Weigelt, O. (2016). Examining the moral grey zone: The role of moral disengagement, authenticity, and situational strength in predicting unethical managerial behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(1), 65–78.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

Kunda, Z., & Sanitioso, R. (1989). Motivated changes in the self-concept. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 272–285.

Lane, H., Maznevski, M., & Mendenhall, M. (2004). Globalization: Hercules meets Buddha. In H. V. Lane, M. L. Maznevski, M. E. Mendenhall, & J. McNett (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of global management: A guide to managing complexity (pp. 3–25). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Leavitt, K., Zhu, L., & Aquino, K. (2016). Good without knowing it: Subtle contextual cues can activate moral identity and reshape moral intuition. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 785–800.

MacKinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144–158.

Martin, D., Seppala, E., Heinberg, Y., Rossomando, T., Doty, J., Zimbardo, P., et al. (2015). Multiple facets of compassion: The impact of social dominance orientation and economic systems justification. Journal of Business Ethics, 129, 237–249.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 633–644.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390.

Mercier, H., & Sperber, D. (2011). Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34, 57–111.

Messick, D. M. (1993). Equality as a decision heuristic. In B. E. Mellers & J. Baron (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on justice (pp. 11–31). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, R. D., Dalal, R. S., & Hermida, R. (2010). A review and synthesis of situational strength in the organizational sciences. Journal of Management, 36(1), 121–140.

Mischel, W. (1973). Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review, 80(4), 252–283.

Miska, C., Stahl, G. K., & Fuchs, M. (2016). The moderating role of context in determining unethical managerial behavior: A case survey. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3374-5.

Molden, D. C., & Higgins, E. T. (2005). Motivated thinking. In K. Holyoak & B. Morrison (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 295–320). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Monin, B., & Jordan, A. H. (2009). The dynamic moral self: A social psychological perspective. In D. Narvaez & D. Lapsley (Eds.), Personality, identity, and character: Explorations in moral psychology (pp. 341–354). New York, NY: Cambridge University.

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65, 1–48.

Moore, C., & Gino, F. (2015). Approach, ability, and aftermath: A psychological process framework of unethical behavior at work. The Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 235–289.

Noval, L. J., & Stahl, G. K. (2017). Accounting for proscriptive and prescriptive morality in the workplace: The double-edged sword effect of mood on managerial ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2767-1.

Noval, L. J., Stahl, G. K., & Molinsky, A. (2016). Motivated dissimilarity construal and self-serving behavior. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Meeting. Anaheim, CA, USA.

Paharia, N., & Dehspandé, R. (2009). Sweatshop labor is wrong unless the jeans are cute: Motivated moral disengagement. Harvard Business School working paper No. 09-079.

Paharia, N., Vohs, K. D., & Deshpande, R. (2013). Sweatshop labor is wrong unless the shoes are cute: Cognition can both help and hurt moral motivated reasoning. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121, 81–88.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Bertram, F. M. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741–763.

Pratto, F., Tatar, D. G., & Conway-Lanz, S. (1999). Who gets what and why? Determinants of social allocations. Political Psychology, 20(1), 127–150.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European Review of Social Psychology (vol. 17, pp. 271–320).

Preacher, K., Rucker, D., & Hayes, A. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227.

Reed, A. I., & Aquino, K. (2003). Moral identity and the expanding circle of moral regard towards out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1270–1286.

Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2007). The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: An empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1610–1624.

Reynolds, S. J., Schultz, F. C., & Hekman, D. R. (2006). Stakeholder theory and managerial decision-making: Constraints and implications of balancing stakeholder interests. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 285–301.

Rosenblatt, V. (2012). Hierarchies, power inequalities, and organizational corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(2), 237–251.

Rutte, C. G., Wilke, H. A. M., & Messick, D. M. (1987). The effects of framing social dilemmas as give-some or take-some games. British Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 103–108.

Samuelson, C. D., & Allison, S. T. (1994). Cognitive factors affecting the use of social decision heuristics in resource-sharing tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 58, 1–27.

Shalvi, S., Gino, F., Barkan, R., & Ayal, S. (2015). Self-serving justifications: Doing wrong and feeling moral. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(2), 125–130.

Shao, R., Aquino, K., & Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(4), 513–540.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stahl, G. K., & Sully de Luque, M. (2014). Antecedents of responsible leader behavior: A research synthesis, conceptual framework, and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 235–254.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (2004). Ethical fading: The role of self-deception in unethical behavior. Social Justice Research, 17, 223–236.

Treviño, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situationist interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 111(3), 601–617.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. K., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Tsang, J. A. (2002). Moral rationalization and the integration of situational factors and psychological processes in immoral behavior. Review of General Psychology, 6(1), 25–50.

Uhlmann, E., Pizarro, D. A., Tannenbaum, D., & Ditto, P. H. (2009). The motivated use of moral principles. Judgment and Decision Making, 4(6), 476–491.

Wade-Benzoni, K. A., Tost, L. P., Hernandez, M., & Larrick, R. P. (2012). It’s only a matter of time: Death, legacies, and intergenerational decisions. Psychological Science, 23, 704–709.

Winterich, K. P., Aquino, K., Mittal, V., & Swartz, R. (2013). When moral identity symbolization motivates prosocial behavior: The role of recognition and moral identity internalization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 759–770.

Xu, Z. K., & Ma, H. K. (2016). How can deontological decision lead to moral behavior? The moderating role of moral identity. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 537–549.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Noval, L.J., Hernandez, M. The Unwitting Accomplice: How Organizations Enable Motivated Reasoning and Self-Serving Behavior. J Bus Ethics 157, 699–713 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3698-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3698-9