Abstract

Interest in corporate citizenship (CC) has been burgeoning in the academic and managerial realms for decades. While a psychological CC climate has been conceptualized and has received empirical support for its relationship with employee outcomes, the organizational climate perspective of CC has not yet been explored. In the present study, we develop and examine a mediated moderation model that elaborates the underlying psychological process and the contingency of organizational CC climate and its individual outcomes. We follow 539 employees in 26 firms for approximately one year in Taiwan. We find that organizational CC climate is positively related to employees’ organizational identification (OI) and that the firm’s high-commitment work system (HCWS) can augment the effect of CC on employees’ OI. In addition, employees’ OI plays a psychological process role in mediating the interactive effect of the firm’s CC and HCWS on employees’ workplace outcomes, including their job satisfaction (JS) and turnover intention. The findings shed light on the alignment of CC and human resource functions and argue that the Confucian Asian context may act as a stepping stone for the impact of CC on employees’ attitudes. The study offers valuable implications for both researchers and practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent decades, corporate citizenship (CC), which refers to discretionary actions on the part of a firm that appear to advance economic, societal and stakeholders’ well-being (Lin et al. 2010; Vlachos et al. 2013), has attracted the attention of both scholars and practitioners. Burgeoning academic research on this topic reflects the fact that a growing number of companies engage in CC and view it as a strategic anchor for the sustainability of an organization’s operations (Newman et al. 2015). CC that introduces socially responsible policies and processes has been proven to benefit companies not only by minimizing the negative impact of business operations on environment and communities, but also by satisfying primary stakeholders’ (i.e., employees) psychological needs and bolstering their positive work attitudes and behaviors (Bauman and Skitka 2012). Empirical studies also show evidence that CC is positively associated with workplace outcomes of individual employees, such as task performance, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB), perceived organizational justice and organizational commitment (e.g., Hofman and Newman 2014; Moon et al. 2014; Rupp et al. 2013, 2015; Wong and Gao 2014; Zhang et al. 2014).

Despite the growing attention given to CC by academics and practitioners, there still remain challenges for exploring the relationship between CC and employees’ outcomes. First, in the human resource management (HRM) and organizational behavior (OB) disciplines, most scholars conceptualize CC as a psychological climate based on the assumption that employees’ perceptions of the extent to which their organizations fulfill CC have implications for individual outcomes (e.g., Chen and Lin 2014; Newman et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2013). Although prior literature supports this psychological climate assumption, these results are unable to establish firm and solid relationships between CC and employee consequences, since the nature of CC should be considered a “corporation’s” or an “organization’s” attribute that is beneficial for important stakeholders and social needs (Duane Hansen et al. 2016; Newman et al. 2015), rather than the limited view of “employees’” psychological perception. Prior studies focusing too heavily on the psychological CC climate may overlook the shared assignment of employee perceptual agreement (Schneider et al. 2013) and leave CC out of a higher level of organizational phenomenon. To expand on prior studies, the present research, based on business ethics and strategic HRM literature, conceptualizes CC as an organizational climate theoretically and investigates the influence of organizational CC climate on individual subsequent workplace attitudes empirically.

Second, even if scholars have recognized some outcomes of CC’s impact on employees’ attitudes and behaviors, the underlying mechanism that drives employees’ desired responses to CC remains little examined (De Roeck and Delobbe 2012). Social identity theory is usually embraced as a focal theory in explaining CC issues (Bauman and Skitka 2012). However, most prior research is only theoretically rooted in social identity and does not empirically verify its intermediating role in the CC–employee outcomes linkage (e.g., Evans and Davis 2011; Lin et al. 2010; Moon et al. 2014; Newman et al. 2015), which makes the actual identity mechanism difficult to support. Thus, to fill this deficiency, the present study draws on social identity theory to discuss the CC phenomenon through mechanisms of inter-organizational distinctiveness and intra-organizational similarity (Bauman and Skitka 2012) and empirically ascertains the intermediating effect by examining the psychological process of OI through which the organizational CC climate relates to employees’ JS and turnover intention.

Third, the path between CC and employee outcomes should include not only the underlying process but also the contingency effect (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). However, we find that most prior research simply adopts one of the two effects when discussing how employees respond to CC (e.g., Evans and Davis 2011; Lin et al. 2010; Rupp et al. 2013), which may block our thorough understanding of the important facts in terms of how CC results in desired employee work outcomes. Unlike prior research, we not only propose that the impact of CC on employee outcomes occurs by way of employees’ OI but also that it is conditioned by the extent of a firm’s investment in HCWS. That is, a firm’s investment in a well-functioning HR system may act as a complement to CC by leaning on its human capital-, motivation- and opportunity-enhancing processes (Jamali et al. 2015; Voegtlin and Greenwood 2016; Yeh et al. 2014) and cooperative norms (Shen and Benson 2014). Our third objective is to present a thorough model, which is a mediated moderation framework that considers the underlying process effect of OI and the contingency effect of HCWS together to explore the influence of CC on employees’ subsequent reactions.

Finally, CC has been noteworthy in the West; however, the awareness of its importance still remains relatively low in Confucian Asia (Kang and Liu 2014). Some scholars indicate that Confucian culture has a positive influence on business ethics due to its focus on collectivism, nature worship and social harmony (e.g., Lam 2003; Chung et al. 2008; Wei et al. 2014). However, some offer an opposite view that Confucianism may bring about crony capitalism, which can wreak havoc in the ethical foundation of CC because resource distributions overwhelmingly hinge on personal opportunism or affective guanxi (Ip 2008). Accordingly, whether Confucian culture causes an upward lift or a downward plunge for the impact of CC on employees’ attitudes should be determined by more extensive research in Asian Confucian societies. Taiwan, though deep nurtured by traditional Confucian culture, is characterized by a Western civilization and free market system, which is a context that contributes to the effectiveness of CC (Wei et al. 2014). The Taiwanese sample used in the current study can therefore be seen as appropriate and valid representative for investigating whether Confucian culture is a burden or a catalyzer for the impact of CC on employees’ outcomes.

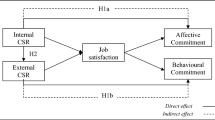

By integrating the aforementioned arguments, the present study conducts a time-lagged multilevel examination in Taiwan to prove a mediated moderation model regarding whether and how organizational CC climate can interact with an organization’s HCWS to impact employees’ JS and turnover intention through employees’ personal identification with their organizations. Figure 1 outlines the proposed research model of this study.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Corporate Citizenship

Although CC has become a significant issue, the concept has continued to evolve for decades. As far back as the 1930s, CC has been introduced to corporations to educate businessmen regarding the need for concern for social welfare (Carroll 1979). By the 1950s, after Bowen’s (1953) Social Responsibility of the Businessman was published, discussions of CC were publicized widely, marking the arrival of the modern era of CC. During the period between the 1960s and 1970s, scholars proposed numerous definitions of CC. In this period, a fierce critique began when Friedman (1962) asserted that social responsibility is a “fundamentally subversive doctrine.” He claims that the only social responsibility for businesses is to use their resources to maximize their economic profits (Friedman 1962, 1970). McGuire (1963) and Backman (1975) admit the primary economic concerns that Friedman mentions but accommodate a broader view that corporations should have certain social responsibilities beyond economic and legal obligations. Other scholars regard CC as simply involving purely voluntary activities, thus defining it as something corporations consider over economic and legal criteria (e.g., Manne and Wallich 1972). Sethi (1975) takes a different path in defining CC. He puts forward a three-state schema (i.e., social obligation, social responsibility and social responsiveness) to classify how corporations respond to social needs. Social obligation implies the adaptation of corporation behavior to market forces or legal constraints. Social responsibility involves corporate behavior that accords with social norms, values and expectations. Social responsiveness, the third state of the schema, elaborates the philosophy of corporate behavior in response to social dynamism rather than the kinds of social issues that corporations should address. Therefore, corporations have to be “anticipatory” and “preventive” (Sethi 1975).

Considering various views on what CC defines, Carroll (1979) proposes a social performance model that elaborates the full range of corporations’ obligations to society. The model conceptualizes CC as comprising four main social responsibilities of corporations, including economic, legal, ethical and discretionary responsibilities, which are partly consistent with some of the antecedent definitions but in a more exhaustive manner. Discretionary responsibility, the fourth category of CC, is termed philanthropic responsibility by Carroll (1998), but is exactly synonymous with his definition in 1979. Specifically, economic responsibility implies that corporations have to be profitable and produce goods and services that are needed in society. Legal responsibility requires that corporations meet their economic targets within the requirements of laws and regulations. Ethical responsibility suggests that corporations must meet the modes of conduct and moral expectations that are above and beyond legal requirements. Finally, discretionary responsibility reflects the desire to see corporations voluntarily involved in prosocial activities beyond previous former three responsibilities. These four types of responsibilities are not mutually exclusive; rather, they always exist simultaneously in business organizations (Carroll 1979). Carroll’s comprehensive definition of CC helps us to understand the trends of CC over time and provides a whole classification scheme for corporations’ different types of social obligations.

The conceptualization of CC has progressively evolved as the public’s expectations of economics, legality, social norms and philanthropy have changed over time (Lee and Carroll 2011). In its initial stage, a narrow economic and legal view of CC is dominant, which upholds that corporations are socially responsible when they maximize their profits and comply with the law (e.g., Easterbrook and Fischel 1996; Friedman 1962, 1970). From this perspective, economic exchange is socially desirable because profitable corporations can deliver profitability that their stakeholders seek and need (Bauman and Skitka 2012; Matten and Crane 2005). In the late 1970s, the idea of corporations as social actors began to emerge, welcoming the new era of the equivalent view of CC (Lee and Carroll 2011; Matten and Crane 2005). Proponents of the equivalent view contend that corporations should use their resources for the betterment of broad social ends and not simply for the economic bottom line of private firms (Bauman and Skitka 2012). This perspective is especially evident in Carroll’s (1979, 1998) articles, which integrate economic performance and legal requirements into social performance, in addition to placing ethical and discretionary expectations into a self-interested economic and legal approach. Nowadays, the four dimensions of CC are generally considered essential obligations that firms should fulfill and perform (Lee and Carroll 2011). In a variety of CC or corporate social responsibility studies, scholars also adopt the four-faceted definition to discuss the business–society relationship (e.g., Boddy et al. 2010; Evans and Davis 2014; Lee and Carroll 2011; Maignan and Ferrell 2000).

Corporate Citizenship and Individual Level of Analysis

Prior academic efforts to comprehend the antecedents and consequences of CC have mostly focused on the organizational level of analysis in recent years (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). That is, burgeoning empirical studies indicate that CC can lead to positive firm reputation and financial performance, causing many to believe and espouse the notion that CC benefits firm-level outcomes (e.g., Margolis and Walsh 2003; Orlitzky and Benjamin 2001; Orlitzky et al. 2003; Peloza 2009). Nevertheless, some researchers address some limitations with regard to these organization-level studies; for instance, crucial control variables are missing, thus confounding the association between CC and firm outcomes; mediating or moderating variables are absent, making it difficult to clarify through what processes or under what conditions the effect of CC occurs; and theoretical arguments to account for the relationship between CC and organizational performance are lacking (Aguilera et al. 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Bauman and Skitka 2012). Moreover, there is doubt regarding whether these existing studies well-operationalize the CC construct (Bauman and Skitka 2012; Margolis and Walsh 2003; Peloza 2009). Previous organization-level studies therefore respond to questions about CC with equivocal answers.

A relatively underutilized method of understanding the potential advantages of CC for firms is to explore the influence of CC on employee work outcomes (Bauman and Skitka 2012). While research often addresses the impact of CC on a firm’s important stakeholders, such as investors and consumers (e.g., Graves and Waddock 1994; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), the critical role that CC plays in employee consequences is rarely discussed (Aguilera et al. 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2012). Based on the content analysis, Aguinis and Glavas (2012) reveal that only 4% of their reviewed articles publish CC research at the individual level of analysis, including micro-OB, micro-HRM, and industrial/organizational (IO) psychology. Therefore, scholars could make a great contribution in CC research if they found employee attitudes and behaviors would be far-reaching consequences of CC. If CC could help firms to attract candidates, increase firm members’ job satisfaction and retain talented employees, firms that possess CC activities or climate would operate better than those that do not. Moreover, the individual level of analysis of how employees conceptualize their alignment with firms can help to complement existing organizational-level studies by exploring missing psychological processes and boundary conditions and by explaining additional variance in how employees respond to CC (Bauman and Skitka 2012). Therefore, it is of great importance for the individual level of analysis to accede to CC research.

Organizational Climate Perspective of Corporate Citizenship

Taking an overview of past studies analyzing individual-level CC research, we find that most of them regard CC as a psychological climate (e.g., Chen and Lin 2014; Evans and Davis 2014; Newman et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2013). The psychological climate view of CC refers to an individual’s interpretation and evaluation of situational occurrences (e.g., events, policies and organizational emphases) that create the meaning of CC for an individual (Evans et al. 2011a, b). Based on Carroll’s (1979, 1998) social performance model, researchers have conceptualized the psychological CC climate as an individual’s perception of the degree to which the organization fulfills processes, activities and policies typified by economic, legal, ethical and discretionary responsibilities (Evans and Davis 2011; Maignan and Ferrell 2000). Specifically, perceived economic CC is concerned with an individual’s interpretation of whether a firm meets the obligation to maintain operational efficiency and economic competitiveness. Perceived legal CC is related to an individual’s interpretation of the degree to which a firm meets the obligation to comply with government policies and regulations. Perceived ethical CC considers the extent to which an individual perceives a firm as complying with moral rules. Finally, perceived discretionary CC refers to the extent to which an individual perceives a firm as encouraging non-mandated activities to promote the well-being of employees and society. Since organizations are typically engaged in CC activities that are multidimensional and amalgamated, perceptions of the four CC dimensions are united to form one’s evaluation of the organization (e.g., Evans et al. 2011a, b; Evans and Davis 2011, 2014; Moon et al. 2014).

Empirical work has also shown the impact of psychological CC climate on the workplace outcomes of individual employees. For example, employees’ perceived CC is found to be positively related to their OCB (Lin et al. 2010; Evans and Davis 2014; Evans et al. 2011b; Rupp et al. 2013) and negatively related to their deviance (Evans and Davis 2014; Evans et al. 2011b) and organizational cynicism (Evans et al. 2011b). It is also proven to be a crucial antecedent of organizational commitment and OI (Turker 2009; Wong and Gao 2014). Moreover, scholars reveal that psychological CC climate plays a role in the formation of work engagement (Lin et al. 2010) and organizational trust (Lin et al. 2010; De Roeck and Delobbe 2012), and conclude that psychological CC climate can effectively reinforce employees’ perception of organizational prestige (De Roeck and Delobbe 2012). However, despite these rich findings, we still cannot answer with certainty the pivotal question of “Do CC-accompanied firms contribute to positive employee consequences?”, since psychological climate is an individual-differences-oriented attribute rather than a unit or organizational phenomenon (Schneider et al. 2013). Prior studies overly emphasizing psychological climate may ignore the term “organizational” and leave the “sharedness” nature of individuals’ perceptions aside (Patterson et al. 2005; Schneider et al. 2013). To compensate for this deficiency, the organizational climate view of CC can be an antidote.

Organizational climate refers to employees’ shared perceptions of organizational events, practices and procedures, which form an aggregate unit of analysis (Patterson et al. 2005). Its rationale is perceptual agreement which implies that a shared assignment of psychological meaning enables individual perceptions to be aggregated and to serve as a higher-level construct (Patterson et al. 2005). Climate researchers indicate that organizational climate is conceptually appropriate, since collectives have their own unique climate and individual perceptions can yield improved consensus when aggregated (LeBreton and Senter 2008; Patterson et al. 2005; Schneider et al. 2013). Therefore, most studies now focus on organizational climate instead of psychological climate (Patterson et al. 2005; Schneider et al. 2000, 2013).

CC is a term adopted to capture an “organizational” intent, beyond the pursuit of financial profit, to achieve positive social welfare through “organizational” policies and actions (Duane Hansen et al. 2016). Since it is viewed as comprising “organizational” actions and policies that are beneficial for the sustainability of business operations (Newman et al. 2015), as well as “organizational” obligations that corporations should fulfill for important stakeholders and social needs (Carroll 1979, 1998), the essence of CC is seen as more similar to an organizational phenomenon or context (i.e., organizational climate) than to an individual attribute (i.e., psychological climate). The organizational climate perspective of CC can signal a social information process (Schneider et al. 2013), which helps to explain how the collective meaning that employees attach to CC processes and activities influences their subsequent attitudes and behaviors.

In addition, the organizational climate perspective echoes the concept of legitimacy—a chief principle for defining CC and determining its successful implementation in firms (Lee and Carroll 2011). Legitimacy is described as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions” (Suchman 1995). Legitimacy is socially constructed because it connotes congruence between social values of organizational activities and shared beliefs of stakeholders (Suchman 1995), which accordingly implies that firms can achieve success in CC when their CC activities meet the social norms and expectations of their stakeholders, including their employees (Lee and Carroll 2011). On the other hand, organizational climate refers to the shared meaning attached to the activities and processes employees experience and certain behaviors they observe being supported and expected (Schneider et al. 2013), which hints that firms can build a strong CC climate when employees collectively perceive that involvement in CC activities is accompanied by support and anticipation. According to these definitions, the concept of organizational climate has in common with legitimacy within corporations and may serve as one of the root causes of legitimacy. First, the two concepts stand for the higher-level context, which focuses on employees’ generalized or shared perception of whether CC activities and processes are appropriate or expected. Second, both concepts can be used as organizational strategic resources to achieve support and approval from employees, which then translates into positive employee satisfaction and long-term sustainability (Bowen and Ostroff 2004; Zhang et al. 2015). De Roeck and Delobbe (2012) argue that organizations’ strong engagement in CC activities can support organizational legitimacy, which in turn encourages employees to identify with their organizations and improve organizational performance. In this vein, firms with a sound organizational CC climate signify that they have the capability to achieve higher internal legitimacy with their employees, which can further boost favorable workplace consequences for employees. Based on these discussions, we argue that the organizational climate perspective is more responsive to the nature of CC and should be more applicable to expound the association between CC and the outcomes of individual employees, than psychological climate is.

Although the organizational climate perspective reflects the essence of CC, and its significance for employee outcomes is addressed in previous research (Morgeson et al. 2013), empirical studies exploring the influence of organizational CC climate on employees’ reactions are noticeably missing. While some terms, such as ethical climate and collective OCB, are seemingly similar to CC, and although prior studies have extensively examined their influences on employee behaviors and attitudes (e.g., Nedkovski et al. 2017; Wang and Hsieh 2012, 2013), these results do not analogize the impact of organizational CC climate, since they are conceptually different from CC climate. First, the focus of ethical climate, defined as “the shared perception of what is correct behavior and how ethical situations should be handled in an organization” (Victor and Cullen 1987, p. 51), is somewhat narrow, considering merely the ethicality of the policies and procedures existing within the organization while disregarding the economic, legal and discretionary responsibilities for internal and external stakeholders. Second, OCBs are defined as discretionary behaviors that cannot be directly spurred by a formal reward system and that, in aggregate, can promote the functioning of the organization (Organ 1988). Despite the fact that the voluntary nature of OCB is similar to CC, its voluntary subject is restricted to employees’ affiliated organization (OCB-O) and within-organizational members (OCB-I) (Williams and Anderson 1991). Moreover, collective OCB mainly focuses on employees’ discretionary actions, excluding Carroll’s (1979, 1998) other three dimensions of CC. Compared with ethical climate and collective OCB, organizational CC climate emerges as a more comprehensive term, involving broad intra- and inter-organizational social roles and widely responding to far-flung requirements of stakeholders. Consequently, organizational CC climate should be considered as distinct from organizational ethical climate and collective OCB and in fact can act as an important antecedent of the two (Chun et al. 2013; Duane Hansen et al. 2016).

Based on the above discussion, in the study we conceptualize CC as the organizational climate, which serves as the means to help to achieve positive employee outcomes. It is the right time to provide empirical evidence of the association between organizational CC climate and consequences of individual employees and to investigate when, why and how this association occurs. The present study accordingly develops a mediated moderation model that simultaneously considers an important boundary condition of HCWS and the psychological process of OI in order to fill prior research gaps, arguing that the interactive effect of CC and HCWS can be mediated by employees’ OI, which further influences two critical employee attitudes, JS and turnover intention.

Corporate Citizenship and Organizational Identification

The relationship between CC and OI can be viewed through the lens of social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986). Social identity theory suggests that the self may be defined in social groups to a greater or lesser degree (Tajfel and Turner 1986). The self-conception with regard to “we” rather than “I”, in which social group membership becomes self-referential, is referred to as social identity (Tajfel and Turner 1986). Accordingly, social identity implies a psychological merging of the self and social groups that leads individuals to perceive themselves as belonging to a certain group (Turner et al. 1987). Two primary mechanisms, intergroup distinctiveness and intra-group similarity, can explain why relationships with groups are essential to people’s self-concept (Bauman and Skitka 2012). First, group membership is important for people to define themselves and understand their social environment, including the surrounding in which they work (Tajfel and Turner 1979). They may feel a sense of connectedness with the group to which they belong and view its fate as their personal fate (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994; Tajfel and Turner 1979). Therefore, they may care deeply about the question of “Who are we?” and “How good are we?” in comparison with other groups (Ashforth et al. 2008). In short, people attempt to build positive social identity through affiliating with admirable groups (referred to as “basking in reflected glory” by Cialdini et al. 1976), which reflects the implication of intergroup distinctiveness. Second, intra-group similarity refers to how similar employees perceive between themselves to be to the group (Bauman and Skitka 2012). Self-categorization theory, a part of social identity perspective, explains how and when people regard themselves as members of the group (Turner et al. 1987, 1994). According to this theory, people may see organizations as prototypes, which are used to judge the amount of similarity between the self and the group (Turner 1987). When people perceive that they are prototypical, they may feel safe and secure about their self-concept and be more likely to identify with the group (Dutton et al. 1994; Hogg and Terry 2000). In contrast, once they feel that they are not prototypical, they may experience a sense of uncertainty about their self-concept and have less social identification. On the whole, intra-group similarity implies that people desire to affiliate with a group that resembles themselves.

Ashforth and Mael (1989) argue the organizational identification is one of the specific forms of social identification and that, therefore, social identity theory can be applied to the organizational context to elucidate why employees are willing to affiliate with certain organizations. OI occurs when employees perceive a sense of oneness with their organizations, as a result of which their beliefs about the organization become self-referential or self-defined (Ashforth and Mael 1989). Through OI, employees may perceive themselves as psychologically intertwined with the organization’s success or failure, and they are intrinsically motivated to sacrifice for the collective (Ashforth and Mael 1989). Grounded in social identity theory, CC can be associated with positive OI, since it provides employees with a source of pride and also engenders a sense of belongingness and social validation of important beliefs and values, with the former specifically reflecting inter-organizational comparisons and the latter mirroring intra-organizational similarity (Bauman and Skitka 2012). With regard to inter-organizational distinctiveness, employees can regard CC as a source of organizational distinctiveness that promotes the firm’s image relative to others and makes membership in the organization more desirable (Bauman and Skitka 2012). Employees affiliated with a socially responsible organization are therefore more likely to build up their perceived external prestige, feel a sense of pride at being part of the organization, and experience increased identification with the organization (Turker 2009). In sum, CC provides employees with opportunities to classify themselves into a salient organizational demographic through social comparisons, which enhances their self-esteem and organizational identification (Newman et al. 2015). Regarding intra-organizational similarity, CC may affect OI through perceived prototypicality (Bauman and Skitka 2012). CC projects that leading employees to participate in socially responsible activities together may affect OI by reinforcing employees’ sense that they are like others in the organization (Bartel 2001; Bauman and Skitka 2012). To the extent that CC transmits the company’s values and affects employees’ prototypes of their corporations, it may result in value congruence between employees and organizations and increase the sense of belongingness (Bauman and Skitka 2012). Therefore, CC satisfying employees’ needs for belongingness and promoting feelings of organizational fit should be positively associated with employees’ OI.

In summary, the social identity perspective can help to illustrate why CC facilitates employees’ OI. CC can serve as a source of inter-organizational comparisons and of a sense of esteem. Besides, it also shapes perceived similarity and the sense of belongingness between employees and the organization. As a means to achieve favorable inter-distinctiveness and intra-similarity, CC can increase the extent to which employees identify with their organizations. Following the above discussion, we advance the following hypothesis:

H1

Corporate citizenship is positively related to employees’ organizational identification.

High-Commitment Work System

HCWS refers to a certain kind of employment mode that is implemented to elicit employees’ commitment to their organizations (Xiao and Tsui 2007). Relative to a control-oriented people management system, HCWS emphasizes internal development and long-term relationships with employees (Kim and Wright 2010; Xiao and Tsui 2007). Thus, HCWS underlies an employment relationship that is clan-like and is imbued with strong norms of cooperation and reciprocity (Xiao and Tsui 2007). The conceptual and empirical understanding of HCWS includes a bundle of internally consistent HR practices, such as selective staffing, comprehensive training, compensation management, developmental performance appraisal, internal promotion, team-based work and employee participation (Chang et al. 2014; Chiang et al. 2014; Lepak and Snell 2002; Takeuchi et al. 2007).

Selective staffing and comprehensive training are designed to increase employees’ knowledge, skills and abilities (KSAs), which affect employees’ human capital (Chang et al. 2014; Jlang et al. 2012; Subramony 2009). These practices promote desired employee outcomes by attracting and selecting highly qualified applicants capable of ongoing learning, as well as by ensuring that those applicants keep their task-related and organization-relevant KSAs after they are hired in order to maintain high levels of performance (Batt 2002; Jlang et al. 2012; Subramony 2009). Compensation, developmental performance appraisal and internal promotion are implemented to direct employees’ endeavors to accomplish work objectives and provide them with inducements to promote work motivation (Chang et al. 2014; Chiang et al. 2014). These practices motivate employees to achieve desired outcomes by signaling what behaviors are expected, supported and rewarded (Chiang et al. 2014). In addition, team-based work and employee participation are designed to encourage participation among employees and empower them to improve their job objectives (Chang et al. 2014; Chiang et al. 2014; Subramony 2009). These HR practices are intended to delegate decision-making authority and responsibility to the employees, thus enhancing employee outcomes by restructuring and reprogramming work to increase the frequency of employee involvement (Huselid 1995; Mathieu et al. 2006; Subramony 2009). Since all of these HR practices influence employees by simultaneously enabling, motivating and empowering them, they are expected to be complementarily amalgamated together to form HCWS (Chang et al. 2014; Chiang et al. 2014; Lepak and Snell 2002).

The value of a commitment system lies in employee well-being and the belief that employees are capable, empowered and intrinsically motivated (Mossholder et al. 2011). Since employees in HCWS-embedding organizations are controlled through reciprocal culture and role expectations rather than rigid rules of job descriptions, there is an atmosphere of trust and strong norms of collaboration to bolster favorable employee attitudes (Xiao and Tsui 2007). For example, various socialization mechanisms such as information sharing, participation in decision making and social gathering may promote employees’ identification with their organizations because HCWS strengthens employees’ common identity by involving them in collaborative relationships (Xiao and Tsui 2007). Moreover, this clan-like work system values human attachment, affiliation, collaboration and support, which produces positive affective attitudes such as employee satisfaction and commitment to the organization (Hartnell et al. 2011; Xiao and Tsui 2007). The mutual commitment between organizations and employees blurs the line between self and others, thus minimizing the need for control mechanisms such as external motivation and monitoring (Mossholder et al. 2011). To embrace a long-term orientation toward employees, therefore, firms therefore have to rely on this commitment-oriented management system.

The Moderating Role of High-Commitment Work System

Although the interface and convergence between CC and HRM remains underdeveloped, this area of research has been conceptually argued in recent studies (Branco and Rodrigues 2006; Greenwood 2013; Morgeson et al. 2013). The contribution of HRM to CC may benefit from a better understanding of how organizations interpret and translate CC principles into managerial actions through the systematic leveraging of organizational resources. While HRM has traditionally been inwardly focused and CC has been externally focused, the two domains overlap in terms of some key issues of CC, such as employee motivation and engagement, diversity and equal opportunity, security practices and human rights awareness (Jamali et al. 2015, 2008). HR functions equipped with well-developed human capital, motivational and empowerment mechanisms in relation to employee engagement, organizational learning and culture change are indispensable for CC. In addition, HRM and CC share a common concern with responsible employment practices (Jamali et al. 2015) as well as individual and organizational growth and revitalization (Collier and Esteban 2007). Therefore, CC and HCWS may complement each other, thus further generating favorable outcomes that are essential to an organization.

Selective staffing and comprehensive training can add to the values of CC by attending to workforce diversity and selecting employees with sensitivity toward and appreciation of CC issues (Gully et al. 2013). Moreover, they can help to develop employees’ KSAs in effective stakeholder engagement and communication (Degli Antoni and Portale 2011). Within compensation practices, developmental performance appraisal and internal promotion, they can contribute to CC by formulating criteria based on both economic and social performance, as well as by providing employees with inducements for their behaviors consistent with CC values (Becker 2011; Davies and Crane 2010; Voegtlin and Greenwood 2016). Team design and employee participation help to facilitate the organization’s internal social structure (Combs et al. 2006), which leads to better communication and cooperation in CC projects (Degli Antoni and Portale 2011). In addition, work teams, employee participation and upward feedback systems can promote the values of CC by providing employees with the autonomy to engage in socially responsible events or innovation. Taken together, all these interventions of HCWS functions can help to ensure the alignment of human capital, motivational and opportunity perspectives with espoused CC goals.

In this research, we argue that the complementary effects of CC and HCWS may enhance employees’ identification with their organizations. As discussed above, the role of HCWS in internalizing the values of CC in the organizational culture is immense. Functions of HCWS’s capabilities and incentives in executing organizational strategies, participating in change management facilitation and enhancing managerial responsibility can facilitate the integration of CC within the climate and fabric of the organization (Jamali et al. 2015). A stronger CC climate accentuated by HCWS signals the organization’s willingness to fulfill processes and policies typified by CC responsibilities, which raises the levels of employees’ psychological needs for inter-organizational distinctiveness and intra-organizational similarity and further promotes employees’ identification with their organizations (Bauman and Skitka 2012).

Furthermore, HCWS features largely in cooperative norms, which may function as the glue that facilitates the consolidation of group cohesion (Shen and Benson 2014; Xiao and Tsui 2007). In organizations with strong group cohesion, employees will be more likely to define themselves in terms of their organizations (Farooq et al. 2014; Xiao and Tsui 2007). Therefore, when organizations possess sound cooperation-featured HCWS, employees’ OI should be upheld by CC. On the other hand, researchers argue that employees are important stakeholders who create demand for CC programs, which implies that CC does act as an employee participation mechanism, encouraging employees to perform socially responsible services (Jones 2010). HCWS that involves cooperative norms naturally facilitates this employee participation mechanism and strengthens the relationship between CC and OI, as it helps employees to engender greater interdependence and membership when they engage in citizenship activities. The above discussion suggests that the strength of the relationship between CC and employees’ OI may vary depending on HCWS.

In summary, with the assistance of HCWS, organizations may form a climate of CC in their business management and create awareness of the need to achieve business goals in a moral and ethical manner (Jamali et al. 2015), which accounts for employees’ OI by increasing their perceptions of self-esteem stemming from a positive social identity and feelings of belongingness and the social validation of important social values (Bauman and Skitka 2012). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2

High-commitment work system positively moderates the relationship between corporate citizenship and employees’ organizational identification, such that higher high-commitment work system is associated with a more positive relationship.

Organizational Identification, Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention

Based on social identity theory, employees with high OI are inclined to incorporate the organizations’ norms and values into their own self-concept, making them psychologically intertwined with their organizations (Tajfel and Turner 1986). In this vein, employees who strongly identify with their organizations tend to take pride in their organizational membership and to be predisposed to evaluate their jobs in a positive manner, which should be positively associated with JS (Loi et al. 2014). Moreover, researchers propose that OI should promote JS, since identified employees are likely to view their job as a proof of their membership, and a positive evaluation of their job will thus be in accord with their organizational identity (Loi et al. 2014; Van Dick et al. 2004). Similarly, self-categorization theory suggests that identified employees have higher perceived value similarity and a higher sense of belongingness with their organizations (Bauman and Skitka 2012), which may result in a strong intention to stay with the organization (De Moura et al. 2009; Van Dick et al. 2004). Consequently, withdrawal from the organization may violate one’s self-concept because it symbolizes a loss of a part of one’s self (Van Dick et al. 2004). Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a

Employees’ organizational identification is positively related to their job satisfaction.

H3b

Employees’ organizational identification is negatively related to their turnover intention.

Organizational Identification as the Mediating Variable

In this study, we contend that OI may mediate the relationships between CC and employees’ JS and turnover intention. As noted in the previous paragraphs, CC is expected to be associated with OI because it causes employees to derive esteem from inter-organizational comparisons and to be reassured by intra-organization similarity (Bauman and Skitka 2012). In addition, accumulating evidence shows that highly identified employees tend to perceive their job circumstances more positively and to be more likely to stay with their organizations, because doing so is viewed as a proof of their organizational membership (De Moura et al. 2009; Loi et al. 2014; Van Dick et al. 2004). For this reason, OI can lead to increased JS and reduced turnover intention. Social identity theory therefore explicates the mediating effect of OI on the relationship between CC and JS/turnover intention.

Although CC is believed to have a positive effect on desired organizational attitudes, the boundary condition that can accentuate this effect is rarely discussed. Prior research suggests that the allocation and investment of organizational resources can facilitate the effect of CC on employees’ attitudes and behaviors; moreover, among various organizational resources, HR practices in particular are addressed (Jamali et al. 2015; Morgeson et al. 2013; Voegtlin and Greenwood 2016). HCWS as an organization’s internal managerial function can help to gauge the social and moral benefits introduced by CC; in addition, it plays an important role in creating supportive conditions under which missions and objectives of CC can be successfully implemented and further lead to employee outcomes that are appreciated (Jamali et al. 2015). Drawing on social identity theory, we argue that CC actions and climate of change, as translated by HCWS, may strengthen the bond between employees and their organizations, especially at the OI level. That is, the integration of CC with HCWS strengthens employees’ membership by satisfying their psychological needs for inter-organizational distinctiveness and intra-organizational similarity, and it can thus contribute to building JS and diminishing employees’ intention to leave. As a result, we further contend that the interaction between CC and HCWS influences employees’ OI, which in turn has an impact on their JS and their propensity to leave. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a

Employees’ organizational identification mediates the interactive effect of corporate citizenship and high-commitment work system on their job satisfaction.

H4b

Employees’ organizational identification mediates the interactive effect of corporate citizenship and high-commitment work system on their turnover intention.

Method

Corporate Citizenship in Taiwan

Taiwan is deeply nurtured by Confucian culture. In the Taiwanese context, the traditional Confucian culture is alive and is deeply rooted in organizational and individual behaviors (Ip 2008; Kang and Liu 2014). However, CC is not a novel concept in Taiwan. The government of Taiwan continues to lead enterprises to adopt CC-oriented principles. Some nonprofit organizations also function as an influential business voice regarding the CC field. In addition, Taiwanese firms have started to disclose their CSR reports which are usually in accordance with GRI (Global Report Initiative) G4 and with AA1000 Type II third-party verification. Some firms have even established the CSR committee to fulfill and implement their CC policies. CC is therefore increasingly accepted and legitimized in Taiwanese enterprises. Overall, the business ethos in Taiwan is a blend of Western civilization and Eastern Confucianism, which gives Taiwanese enterprises an appropriate context for investigating whether Confucian culture is an stumbling block or a stepping stone for the impact of CC on employees’ attitudes.

Participants and Procedures

This study was conducted in Taiwan’s publicly listed firms. We collected data via questionnaire survey in two waves. At time 1, we collected data regarding the firm’s HCWS and human capital. At time 2, we collected employees’ perceptions of CC, OI, JS and turnover intention.

In the first wave, we contacted firms that consistently engaged in CC activities gathered from the alumni directory of an Executive MBA in Northern Taiwan and invited them to participate in this research. Fifty-seven firms listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange (TWSE) acknowledged their willingness to participate in the time 1 survey. We contacted these firms in advance, explained the purpose of the study and then distributed a survey package containing questionnaires to each firm. A cover letter attached to each questionnaire explained the objective of the survey and assured participants of the confidentiality of their responses. To avoid single-informant bias, two HR managers for each firm were invited to participate in our time 1 survey. Thus, from the 57 firms, we asked 114 HR managers to rate the items related to the firm’s HCWS and human capital. Each participant received a gift certificate to thank them for their participation. Ultimately, a total of 86 valid questionnaires from the 57 firms were returned, representing a response rate of 75.4%.

Approximately one year later, we implemented the second wave survey. We contacted the 57 firms that had participated in the time 1 survey, explained the purpose of the time 2 survey to them and invited them to participate in this research. Potential participants were informed that they would be given a gift certificate to thank them for their participation. Ultimately, 26 firms responded that they were willing to participate in the time 2 survey. For each firm, 25 randomly selected employees from different departments were asked to rate items related to the perception of CC, OI, JS and turnover intention. Thus, we asked a total of 650 employees to participate in the time 2 survey. All participants were informed about the objective of the survey and assured of the confidentiality of their responses. We ultimately collected 539 valid questionnaires (for a response rate of 82.9%) from the 26 firms.

After matching the respondent firms from time 1 and time 2, we ultimately retained 52 HR manager samples from the 26 firms. Of the 26 firms, the average firm assets amounted to US$12.8 million, and the average firm size was 5343 employees. Of the 539 employees, 45.8% were male, the average age was 34.8 years, and the average firm tenure was 10.4 years. More precise profiles of the background characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Measures

This study focused on five major variables: CC, HCWS, OI, JS and turnover intention. All variables in the study were measured using established scales proposed by antecedent studies. All items apart from participants’ demographic characteristics were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Perceived Corporate Citizenship

We adopted the 15-item scale from Maignan and Ferrell (2000) to assess employees’ perceptions of the four sub-dimensions of CC: economic (3 items), legal (3 items), ethical (5 items) and discretionary (4 items) citizenship. The Cronbach’s alpha for the 15-item scale was .92.

To assess the appropriateness of aggregating the individual-level perceived CC to the organization-level CC, we calculated within-group agreement (rwg; James et al. 1993), intra-class correlations (ICC[1]) and the reliability of the means (ICC[2]) (Bliese 2000). The mean value of rwg was .94, and the ICC[1] and ICC[2] coefficients were .45 and .89, respectively, providing empirical justification for creating the organization-level CC via aggregation.

High-Commitment Work System

We adopted 21 HR practice items from Lepak and Snell’s (2002) commitment-oriented HR configuration. This HCWS scale was chosen for the present study because antecedent studies have adopted this scale in research in the Asian context (e.g., Chiang et al. 2014; Takeuchi et al. 2007), which can ensure the survey’s external validity across similar cultures. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .90.

Human Capital

Youndt and colleagues’ human capital scale (e.g., Subramaniam and Youndt 2005; Youndt et al. 2004) was used to evaluate the average level of human capital in the organization. The Cronbach’s alpha for the five-item scale was .90.

Organizational Identification

We adopted the 6-item scale from Mael and Ashforth (1992) to assess organizational identification. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .89.

Job Satisfaction

We adopted the 3-item scale from Seashore et al. (1982) to assess job satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .90.

Turnover Intention

A 3-item version of the turnover intention scale from Colarelli (1984) was used in the present study. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .89.

Control Variables

In the study, some firm-level variables, such as firm size, firm assets and human capital were controlled for by capturing organizational resources related to the implementation of HCWS, CC and individual variables. In addition, some employees’ demographic variables were also controlled, including gender (male = 1; female = 0), age, education, firm tenure, managerial position (yes = 1, no = 0) and working hours per week (e.g., Shen and Benson 2014; Takeuchi et al. 2007).

Results

Based on Anderson and Gerbing’s (Anderson and Gerbing 1988) suggestion, we first implemented CFA to verify the construct validity before testing the hypotheses. For individual-level variables, the results indicated that the hypothesized 3-factor measurement model (OI, JS and turnover intention) fit the data (χ2(51, N = 539) = 157.26, p < .01, NNFI = .98, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .04). The second-order CFA of perceived CC was also examined. The result met the model-fit indices (χ2(86, N = 539) = 395.10, p < .01, NNFI = .97, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .05) as well. Factor loadings of all the items were above .50 and significant on the corresponding factors. Moreover, none of the confidence intervals of the correlations covered the value of 1 for each pair of factors. All these results revealed that convergent and discriminant validities were both supported.

For firm-level variables, given the small sample size (N = 52) and the large number of items included in HCWS and human capital, we could not use CFA to test construct validity; instead, we performed the factor analysis with the principal axis method by imposing a single-factor solution (e.g., Takeuchi et al. 2007). The 5 items of human capital had factor loadings ranging between .84 and .89, and this factor explained 72.32% of the variance. All 21 of the items of HCWS had factor loadings ranging between .33 and .82 on a single factor, and this factor explained 36.03% of the variance, which is higher than Takeuchi et al.’s (2007) 35.82%. The scale had a reliability of .90, which is comparable to that Lepak and Snell (2002) and Takeuchi et al. (2007) obtained for their commitment-based HR system scale (α = .89 and α = .90, respectively).

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics, internal consistency coefficients and correlations among the variables. At the individual level (Level 1), OI was positively correlated with JS (r = .44, p < .01) and negatively correlated with turnover intention (r = −.35, p < .01). At the firm level (Level 2), human capital was found to be positively correlated with CC (r = .63, p < .01) and HCWS (r = .63, p < .01). In addition, CC was positively correlated with HCWS (r = .60, p < .01). The Cronbach’s α coefficients among the factors ranged between .89 and .92, exceeding the .70 threshold recommended by Hair et al. (1998).

In this study, our hypothesized model is multilevel in nature, with constructs spanning both the individual level (OI, JS and turnover intention) and the firm level (CC and HCWS) of analysis. Therefore, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was suggested to test our hypotheses (Bryk and Raudenbush 1992).

Before testing our hypotheses, we determined whether HLM was appropriate to analyze our data by examining three null models. The results indicated 6.80% of variance in OI that resided between firms (\(\chi_{(25)}^{2} = 62.93\), p < .01, ICC[1] = .07) and 8.21% of variance in JS that resided between firms (\(\chi_{(25)}^{2} = 70.77\), p < .01, ICC[1] = .08). Analyses also identified 5.20% of variance in turnover intention that resided between firms (\(\chi_{(25)}^{2} = 53.37\), p < .01, ICC[1] = .05). These results provided justification for using HLM for hypothesis estimation (Hofmann 1997).

The Main Effect of Corporate Citizenship

Hypothesis 1 posits that CC is positively related to OI. As shown by Model 1 in Table 4, CC had a positive relationship with OI (γ = .33, p < .01). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

The Moderating Effect of High-Commitment Work System

Hypothesis 2 proposes that HCWS positively moderates the effect of CC on OI. Model 2 in Table 4 showed support for this hypothesis as well (γ = .19, p < .05). We plotted the significant moderating effect in Fig. 2.

The Effect of Organizational Identification on Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention

Hypotheses 3a and 3b suggest that OI is positively related to JS and negatively related to turnover intention. Results from Models 4 and 6 in Table 4 reveal a positive relationship between OI and JS (γ = .45, p < .01) and a negative relationship between OI and turnover intention (γ = −.33, p < .01), thus supporting Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

The Mediating Effect of Organizational Identification

Mediated moderation is formed when the interaction between the independent and moderating variables influences the mediating variable, which in turn has an impact on the dependent variable (Muller et al. 2005; Preacher et al. 2007). Hypotheses 4a and 4b predict two mediated moderation effects, namely OI mediates the interactive effect of CC and HCWS on employees’ JS and turnover intention. Following the suggestions of Preacher et al. (2007) and previous studies (e.g., Liu and Fu 2011; Kirkman et al. 2009), we first tested Hypotheses 4a and 4b based on Mathieu and Taylor’s (2007) procedure to test the cross-level mediation. Next, the Sobel (1982) test was applied to confirm the support of the indirect effect of the interaction on the dependent variable via the mediator.

Cross-level mediation is supported if four conditions are met (Mathieu and Taylor 2007): (1) the independent variable (i.e., the interaction of CC with HCWS) significantly relates to the mediator (i.e., OI); (2) the independent variable significantly relates to the dependent variable (i.e., turnover intention); (3) the mediator significantly relates to the dependent variable; and (4) the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable becomes weaker or is no longer significant.

Since the previous result supported Hypothesis 1, the first condition was met. Results from Model 3 and Model 5 in Table 4 revealed that the interaction between CC and HCWS was positively related to employees’ JS (γ = .20, p < .01) and negatively related to turnover intention (γ = −.25, p < .01), which satisfied the second condition. As Hypotheses 3a and 3b were supported by the previous data analysis, the third condition was also satisfied. In the last step, with the inclusion of OI in Model 4 and Model 6 of Table 4, the interactive effect of CC with HCWS on JS (γ = .05, n.s.) and turnover intention (γ = −.16, p < .01) became weaker. Furthermore, the Sobel (1982) test yielded support for the indirect effect of the interaction between CC and HCWS on JS (Z = 2.71, p < .01) and turnover intention through OI (Z = −2.65, p < .01). Accordingly, Hypotheses 4a and 4b were supported.

Discussion

In support of the social identity theoretical framework, the present study reveals that organizational CC climate is positively associated with employees’ identification with their organizations, and this association is accentuated by organizations’ commitment-oriented employment mode. Overall, employees’ OI translated the interplay between organizations’ CC and HCWS into their JS and turnover intention. These findings also suggest that HR does not simply play the role of administrative management. Rather, it appears to be a strategic lever that internalizes the values of social responsibility within the organizational climate and catalyzes the social identity mechanism that connects CC with employees’ work outcomes. On the other hand, the current study reveals that CC can yield positive employee work consequences in the context of the Taiwanese business ethos as in that of Western societies. This may imply that CC is not a luxury in Confucian Asia, but, rather, is imperative in order to encourage employees to intertwine their self-concept with the organization, respond positively to their jobs and remain in their firms. Our study offers an integration of the business ethics, strategic HRM and OB literature to extend the existing CC research with valuable insights and implications.

Theoretical Implications

The first contribution of the present study is in applying the organizational climate perspective to CC research. Although CC has attracted many researchers’ attention, previous research has focused heavily on individuals’ psychological CC climate (e.g., Evans et al. 2011a; Evans and Davis 2011, 2014; Moon et al. 2014), whereas little is known about whether and how the organizational climate perspective of CC influences employees’ outcomes (Rupp et al. 2013). Excessive emphasis on individual psychological climate may fail to capture the richness of the organizational context (Schneider et al. 2013) and is unable to reflect the legitimacy of organizations’ implementation of CC strategies. In contrast, organizational CC climate ensures the shared assignment of employees’ CC perceptions and confirms the appropriateness of aggregating the psychological CC climate to a higher organizational level of analysis (Morgeson et al. 2013), which enables us to take a more macro-perspective on the CC topic. Moreover, conceptualizing CC as the organizational climate responds to the concept of legitimacy, which ensures that CC can be desirable and proper in organizations (Lee and Carroll 2011) and manifests the value of CC more than psychological climate does. Because of this multilevel research approach, our study also helps bridge the macro–micro-divide in the field of ethics and HRM.

Second, the present study helps to ascertain the underlying psychological process between CC and employees’ outcomes. Social identity theory is theoretically applied to expound the association between CC and employees’ attitudes; however, prior research has seldom actually examined its mediating role (e.g., Lin et al. 2010; Moon et al. 2014; Newman et al. 2015). Even if OI is treated as the mediator, most research operationalizes CC in terms of individual psychological climate (e.g., Brammer et al. 2015; Evans and Davis 2014), which may inflate CC’s effect on individual variables and keep CC within an individual attribute only. Our research compensates for these deficiencies by unpacking OI’s pivotal mediating role in aligning organizational CC climate with employees’ JS and turnover intention. This study provides empirical evidence that OI through mechanisms of inter-organizational distinctiveness and intra-organizational similarity can mediate the relationships between the consensus of employees’ CC perceptions and employees’ JS and propensity to leave.

Third, the study extends prior work by elaborating on a certain contingency, a firm’s HCWS, under which the social identity mechanism embedded in CC can be facilitated and further can boost employees’ outcomes. Some scholars, based on samples of TWSE and GreTai Securities Market (GTSM) listed companies, find that the shortage of human resources is the chief obstacle for CC implementation in Taiwan (Yeh et al. 2014). The success of CC in Taiwanese corporations is thus contingent on effective HR system. HCWS, a vital contingency discussed in the study, is argued to play a strategic role in bolstering CC policies and translating CC vision and aspiration to members of the organization. Many HCWS functions, such as human capital-, motivation- and opportunity-enhancing practices, can reinforce the CC–employee outcomes relationship by fostering the shared values of social responsibility toward employees (Jamali et al. 2015; Voegtlin and Greenwood 2016). The internal foundations and dynamics of CC, bolstered and translated by HCWS, strengthen the bond between employees and the organization, thus fostering individual commitment to and identification with the organization (Jamali et al. 2015). On the other hand, in a commitment-oriented HR system, employees and their organizations are regarded as holding high regard for one another (Mossholder et al. 2011). The cooperative norm developed by HCWS produces a sense of communal sharing and feelings of solidarity that blur the employee–organization distinction (Mossholder et al. 2011; Shen and Benson 2014), which then reinforces the association between CC and OI. Under circumstances of high HCWS, employees may be more responsive to the organizational CC climate and thus encouraged to bring forth more OI, which influences subsequent employee attitudes, JS and turnover intention. Our time-lagged mediated moderation study not only sheds light on the promise of applying social identity theory to ethics research but also advances our understanding by verifying the fact that HCWS can facilitate the strength of social identity by complementing organization-level CC, as strategic HRM theory implies.

Finally, an important contribution of the study is that the hypotheses are proved by a Taiwanese sample, which implies that corporations in this Confucian society can also benefit from CC devotion, just as the Western society does. Though Chinese Confucian culture may expose corporations to crony capitalism (Ip 2008), the upward-lift elements of integrity, loyalty and cooperation in Confucian culture seem superior and thus invulnerable to the downward pull of self-serving personal relationships and rent-seeking behaviors. Our study therefore helps to ensure the scientific validity and explain the variation of CC in the Asian context. Moreover, these empirical findings identify that the Confucian context may stand on a bright force of CC efforts.

Managerial Implications

The present study gives rise to some important managerial implications. We suggest that, in addition to pursuing profit-oriented activities, firms should recognize the benefits of investing in CC since it is a crucial precursor to cultivating employees’ strong identification with their organizations, which brings about their satisfaction with their jobs and attenuates their intention to leave. To strengthen the organizational climate of CC, firms can consider devoting themselves to socially responsible activities directed toward economic, legal, ethical and discretionary aspects. For example, firms should seek to maximize their profitability under the condition of complying with laws and regulations. In addition, firms may consider investing in environmentally protected activities and charitable initiatives in the communities where they are located. Firms can also endeavor to improve the organization–employee relationship by balancing work and personal life and ensuring job security. These practices help to bring forth an organizational CC climate that makes membership in the organization more desirable, which in turn leads to favorable employee outcomes that are beneficial for business operations.

In addition, the study implies that it is important for firms to formulate and implement CC strategies based on the HRM perspective. As the findings demonstrate, firms should not simply focus on CC alone but should give heed to the soundness of their HCWS functions in order to facilitate the impact of CC on employee OI. Thus, organizations should endeavor to strengthen integration and alignment between HR and CC departments and make the best use of the HR profession to internalize prosocial norms in employees’ daily work. To cultivate highly identified employees and further encourage their enjoyment of their jobs, HR management needs to leverage and strengthen internal consistencies of HCWS in relation to CC strategy development and implementation. The co-creation perspective that nurtures the involvement of HCWS in CC provides managers with a road map to understand how social responsibility is integrated into management systems and employee relationships.

Finally, though CC in Asia is not as mature or taken for granted as in the West, we suggest that multinational corporations approaching the Confucian Asian market should include the adoption of CC policies. Our findings reveal that the organizational CC climate in a Confucian Asian context is associated with enhanced employees’ OI and job satisfaction and decreased employees’ turnover intention. Consequently, multinational corporations investing in Confucian Asia have to be aware of the influence of the societal context on the implementation of culturally fitted CC policies. Moreover, they should regard CC involvement as a critical business strategy, because CC does not necessarily conflict with their economic growth but, rather, can pave the way for their employee retention.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While the present study makes notable contributions, it also has some limitations, which provide directions for future research. First, the present study was conducted in a single country, and the data analyzed in the study were from 26 organizations, both of which limit the generalizability of our research to other geographic contexts. Future research can replicate this research framework in cross-cultural contexts over a larger number of organizations.

Second, although we infer the presence of the social identity perspective, some other theories may also be applicable to explain the CC phenomenon. For example, organizational CC climate delivers a clear message to employees that firms will no longer take advantage of them but will be willing to satisfy their needs for work safety and security (Bauman and Skitka 2012), which may lead employees to engage in positive attitudes in a reciprocal manner. Accordingly, social exchange theory might be considered as an alternative theory for future research to discuss the association between CC and employee outcomes.

Third, in the study, we used a subjectively based scale to measure CC, which may have stronger implications for employees’ subsequent reactions than the firm’s actual CC behaviors do. This raises the question of to what extent the psychological ratings from employees respond to the actual CC actions of the firms (Morgeson et al. 2013). To overcome the dilemma of measurement choices, future research can adopt different measurement approaches ranging from subjective to objective indices, as well as experimental designs, in order to clarify the conceptualization of CC.

References

Aguilera, R., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the s back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38, 932–968.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34, 325–374.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39.

Backman, J. (1975). Social responsibility and accountability. New York: New York University Press.

Bartel, C. A. (2001). Social comparisons in boundary-spanning work: Effects of community outreach on members’ organizational identity and identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46, 379–413.

Batt, R. (2002). Managing customer services: Human resource practices, quit rates, and sales growth. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 587–597.

Bauman, C. W., & Skitka, L. J. (2012). Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 63–86.

Becker, W. S. (2011). Are you leading a socially responsible and sustainable human resource function? People & Strategy, 34, 18–23.

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Boddy, C. R., Ladyshewsky, R. K., & Galvin, P. (2010). The influence of corporate psychopaths on corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment to employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 1–19.

Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the strength of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29, 203–221.

Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. New York: Harper & Row.

Brammer, S., He, H., & Mellahi, K. (2015). Corporate social responsibility, employee organizational identification, and creative effort: The moderating impact of corporate ability. Group and Organization Management, 40, 323–353.

Branco, M., & Rodrigues, L. (2006). Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 111–132.

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4, 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1998). The four faces of corporate citizenship. Business and Society Review, 100(101), 1–7.

Chang, S., Jia, L., Takeuchi, R., & Cai, Y. (2014). Do high-commitment work systems affect creativity? A multilevel combination approach to employee creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 665–680.

Chen, M., & Lin, C. (2014). Modelling perceived corporate citizenship and psychological contracts: A mediating mechanism of perceived job efficacy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23, 231–247.

Chiang, Y., Shih, H., & Hsu, C. (2014). High commitment work system, transactive memory system, and new product performance. Journal of Business Research, 67, 631–640.

Chun, J. S., Shin, Y., Choi, J., & Kim, M. (2013). How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Management, 39, 853–877.

Chung, K. Y., Eichenseher, J. W., & Taniguchi, T. (2008). Ethical perceptions of business students: Differences between East Asia and the USA and among “Confucian” cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 79, 121–132.

Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 366–375.

Colarelli, S. M. (1984). Methods of communication and mediating processes in realistic job previews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 633–642.

Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16, 19–33.

Combs, J., Liu, Y., Hall, A., & Ketchen, D. (2006). How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Personnel Psychology, 59, 501–528.

Davies, I. A., & Crane, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in small- and medium-size enterprises: Investigating employee engagement in fair trade companies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 19, 126–139.

Degli Antoni, G., & Portale, E. (2011). The effect of corporate social responsibility on social capital creation in social cooperatives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40, 566–582.

De Moura, G. R., Abrams, D., Retter, C., Gunnarsdottir, S., & Ando, K. (2009). Identification as an organizational anchor: How identification and job satisfaction combine to predict turnover intention. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 540–557.

De Roeck, K., & Delobbe, N. (2012). Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 397–412.

Duane Hansen, S., Dunford, B. B., Alge, B. J., & Jackson, C. L. (2016). Corporate social responsibility, ethical leadership, and trust propensity: A multi-experience model of perceived ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 649–662.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–263.

Easterbrook, F. H., & Fischel, D. R. (1996). The economic structure of corporate law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Evans, W. R., & Davis, W. D. (2011). An examination of perceived corporate citizenship, job applicant attraction, and CSR work role definition. Business and Society, 50, 456–480.

Evans, W. R., & Davis, W. (2014). Corporate citizenship and the employee: An organizational identification perspective. Human Performance, 27, 129–146.

Evans, W. R., Davis, W. D., & Frink, D. D. (2011a). An examination of employee reactions to perceived corporate citizenship. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 938–964.

Evans, W. R., Goodman, J. M., & Davis, W. D. (2011b). The impact of perceived corporate citizenship on organizational cynicism, OCB, and employee deviance. Human Performance, 24, 79–97.

Farooq, M., Farooq, O., & Jasimuddin, A. M. (2014). Employees response to corporate social responsibility: Exploring the role of employees’ collectivist orientation. European Management Journal, 32, 916–927.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase profits. New York Times Magazine, 32–33, 122–126

Graves, S. B., & Waddock, S. A. (1994). Institutional owners and corporate social performance. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1034–1046.

Greenwood, M. (2013). Ethical analyses of HRM: A review and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 114, 355–366.

Gully, S. M., Phillips, J. M., Castellano, W. G., Han, K., & Kim, A. (2013). A mediated moderation model of recruiting socially and environmentally responsible job applicants. Personnel Psychology, 66, 935–973.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Hartnell, C. A., Ou, A. Y., & Kinicki, A. (2011). Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework’ theoretical suppositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 677–694.