Abstract

Acquisition and purchase of counterfeit and pirated products are illicit and morally questionable consumer behaviors. Nonetheless, some consumers engage in such illicit behavior and seem to overcome the moral dilemma by justification strategies. The findings on morality effects on consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products are diverse, and the underlying theories provide no clear picture of the process that explains how morality and justification lead to particular consumer responses or why consumers differ in their responses. This study presents a meta-analysis of 788 effect sizes from 207 independent samples provided in 196 manuscripts that synthesizes the research on the influence of morality on attitudes, intentions, and behavior toward counterfeit and pirated products. The meta-analysis tests competing theoretical models that describe the morality-justification processes, and identifies the deontological–teleological model as the superior one. The meta-analysis further shows that the institutional and social context of consumers explains the differences in morality effects on justifications and responses to counterfeit and pirated products, and provides evidence for the context-sensitivity of the underlying theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent figures indicate that counterfeiting and piracy have become an extensive global economic issue. Imports of counterfeit and pirated goods are worth nearly half a trillion dollars a year, or around 2.5% of global imports (OECD and EUIPO 2016). The adverse effects on businesses and economies are numerous. For example, counterfeiting and piracy are responsible for the loss of $77.5 billion in tax revenues and the loss of over 2.5 million jobs in G20 countries each year. Even with legislation in place, governments struggle to tackle this global problem and despite their efforts, piracy is at a high level and continues to increase (Business Software Alliance 2014).

In an attempt to explain why consumers would engage in behavior that often violates laws and can raise ethical issues and concerns, the purchase of counterfeit and pirated products has often been investigated from an ethical or morality perspective. Some consumers of counterfeit and pirated products are at least somewhat aware that acquiring counterfeit and pirated goods is illegal or unacceptable from a societal point of view (Morris and Higgins 2009), and one would expect that they despise counterfeit and pirated products. However, some consumers do not hold negative views of counterfeiting or piracy, and even claim that it is a victimless crime (Lysonski and Durvasula 2008). These consumers seem to overcome a possible moral dilemma by using justification strategies (Bian et al. 2016). The apparent contradiction in morality effects on consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products is reflected in the diverse findings of prior studies. Some researchers have found evidence that more strongly held moral beliefs that acquiring counterfeit and pirated products is wrong, unethical, or immoral negatively influences attitudes toward such products, intentions to acquire them, as well as actual behavior (e.g., Higgins 2005; Cesareo and Pastore 2014). However, other researchers could not find support for the effects of morality on purchases of counterfeit and pirated products (e.g., Al-Rafee and Cronan 2006; Higgins et al. 2007) or could find support only in certain conditions or samples (e.g., Tjiptono et al. 2016; Shoham et al. 2008). The diversity in findings resembles the theoretical approaches that provide different explanations of the effect of morality on consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products. A dissonance theory-based account suggests that morality increases the perception of negative consequence, thus enhancing justification attempts, which in turn positively influence consumer responses. At the same time, an ethical decision-making account suggests that morality tends to decrease justification efforts that in turn reduce the perception of negative outcomes and increase the perception of positive outcomes, thus influencing consumer responses.

In an attempt to explain the diverse findings in prior research, to provide a clear picture of the theory and the underlying mechanism of how morality and justification influence consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products, and to clarify why consumers differ in their responses, a meta-analysis of 788 effect sizes from 207 independent samples provided in 196 manuscripts was conducted. The meta-analysis synthesizes the research on the influence of morality on attitudes, intentions, and behavior toward counterfeit and pirated products, and tests alternative morality-justification processes that explain how consumers respond to pirated and counterfeit product purchases. The meta-analysis further shows how the institutional and social context of consumers explains why morality can either increase or decrease justification and lead to differences in responses to ethical concerns regarding counterfeit and pirated products.

The findings provide several contributions. First, the meta-analysis tests competing theories that provide explanations for how morality and justification work together in influencing attitudes, intentions, and behaviors toward pirated and counterfeit products. This knowledge guides further research by identifying the theoretical approach that provides the highest explanatory power for morality effects. Second, the study explains how morality effects differ depending on institutional and social context factors. These insights add to the debate about the context-sensitivity and generalizability of theories that have been developed and tested in a Western context by showing that the theoretical explanations have to be adapted to specific cultural contexts. The moderators also provide an explanation for the variation in morality effects observed in prior studies and in counterfeiting and piracy incidents across countries. Third, the insights provide practical implications for anti-counterfeiting and anti-piracy measures by showing how justifications can be used as a lever to enhance morality effects that reduce counterfeit purchases and piracy. The best means of triggering these justification processes depend on institutional and social context factors.

The remainder of the article is organized into three sections. First, the conceptual background for the meta-analysis is developed by defining counterfeiting and piracy, by elaborating on the different theories and models that explain the role of morality and justification in consumption of counterfeit and pirated products, and by discussing the contextual factors that moderate the major effects of morality. Then, the meta-analytic method is described and the findings are presented. Finally, the findings on the relationship between morality and consumer response to counterfeit and pirated products are discussed, thus showing how they enrich theory, explain prior findings, and provide guidance for researchers and practitioners.

Conceptual Background

Counterfeiting and Piracy

A counterfeit product is an unauthorized imitation of a branded product (i.e., a product bearing a trademark) that is offered on the (black) market, while a pirated product is an unauthorized exact copy—not just a simple imitation—of an original product that is protected by intellectual property rights (Bian et al. 2016). Piracy is usually limited to the technological categories of music, movies, software, and any other copy-protected digital materials that are often downloaded online without payment, while counterfeiting refers to a variety of tangible products, such as luxury clothes, jewelry, watches, shoes, car parts, and medication, that are bought mostly on the black market. The research on morality in counterfeiting and piracy relates to non-deceptive counterfeiting, which involves consumers knowingly purchasing or acquiring a counterfeit product or pirated product instead of an original product (Grossman and Shapiro 1988).

Previous research on counterfeiting and piracy has largely applied the same determinants to explain consumption of both types of illicit products (Lee and Yoo 2009). From a consumer’s perspective, the distinction between counterfeiting and piracy is sometimes impossible to comprehend (e.g., when a consumer purchases a pirated movie DVD in a jewel case). The effects of morality are comparable for both types of products, and they show the same mechanisms and direction of effects (though they might differ in the strength of effects) because both counterfeiting and piracy are types of illicit consumption behavior. Acquiring either counterfeit or pirated products can raise ethical issues and concerns, leading to similar consumer responses.

Consumer Responses to Counterfeit and Pirated Products

Prior research applied three dependent variables to capture consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products: attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Attitude refers to consumers’ evaluation of counterfeit and pirated products, and of the act of purchasing these products. Intention indicates consumers’ willingness and likelihood to acquire these products. Behavior refers to the acquisition, purchase, and consumption of these products. These constructs tap into different stages of the consumption process, although they are highly correlated. In particular, behavior can be accurately predicted from behavior-compatible measures of attitudes and intentions (Ajzen and Fishbein 2005).

Morality, Justification, and Outcome Perceptions: Alternative Explanatory Models

Morality refers to the specific ethical beliefs regarding counterfeiting and piracy in general, and to specific counterfeit and pirated products in particular. It covers all concepts arising from the consumer’s ethical dilemma when faced with acquisition or purchase of counterfeit or pirated products, such as ethical beliefs, ethical concerns, moral attitude, moral obligation regarding counterfeiting and piracy, and moral judgment. To use justification processes to explain the relationship between morality and attitudes, intentions, and behavior, the present study focused on the variables that are most commonly investigated in the context of explaining individual responses to morality issues: justification, negative social outcomes, and positive individual outcomes. Other studies that have investigated morality have also considered variables such as subjective or social norms (e.g., Al-Rafee and Cronan 2006; Chen et al. 2009); however, these variables were either used as independent variables in models where they were not directly related to morality, or were used as moderators, and hence could not be used in a process model. Several studies have looked at negative individual outcomes, such as the perceived risk of punishment or of the low quality of counterfeit and pirated products, but findings on the relationships between risk, justification, and social outcomes are scarce and were insufficient to be used for this meta-analysis.

Justification refers to strategies and techniques used to give grounds for the acquisition and purchase of counterfeit and pirated products (e.g., coping strategies and neutralization techniques). Both morality and justification are related to the perception of consequences for deviant behaviors. Negative consequences that are related to morality are consumers’ perceptions of negative social and economic outcomes of the acquisition and purchase of counterfeit and pirated products (e.g., harm to business or loss of taxes). Positive consequences that refer to justification are the perceived individual outcomes of the acquisition of and purchase of counterfeit and pirated products (e.g., reduced prices or improved price-quality relationships) and cover concepts such as expected outcomes, gratification, positive consequences, and benefits.

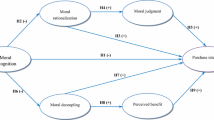

The influence of morality on consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products can be explained by three different theoretical accounts. These accounts are reflected in three conceptual models that can be modeled by altering the relationship between morality, justification, positive individual outcomes, and negative social outcomes, as depicted in Fig. 1. The models are the justification model, the deontological–teleological model, and the perception model.

The relationships between justification, morality, perceptions of positive and negative outcomes on the one side, and attitudes, intentions, and behavior on the other side, are identical in all three models. Morality and the perceptions of negative social outcomes negatively influence attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Justification and perceptions of positive individual outcomes positively influence attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. The direct effects of morality, justification, and perceptions on consumer responses are based on the assumption that certain perceptions and beliefs can influence behavior and intentions directly without prior evaluation (Ajzen 1991). The indirect relationships between attitudes, intentions, and behavior are in line with attitude formation models such as the theory of reasoned action. The following describes how the three models are theoretically embedded and how they can be described by altering the relationship between morality, justification, positive individual outcomes, and negative social outcomes.

Justification Model

The main assumption of the justification model is that because of their ethical concerns over acquiring counterfeit and pirated products, consumers need to generate justifiable reasons for their behavior. The justification model has been proposed in the context of piracy and counterfeiting as an explanation of how consumers deal with ethical dilemmas that arise when purchasing counterfeit products (Eisend and Schuchert-Güler 2006). The model is rooted in the theory of cognitive dissonance that states that people strive for consistencies of their cognitions (Festinger 1957). If relevant cognitions are in conflict (e.g., purchasing a desirable counterfeit product while obeying the law and not harming the society), some form of psychological discomfort arises, and consumers are motivated to strive for actions that reduce discomfort and cognitive dissonance, for instance, by applying coping and justification strategies.

The justification model is backed by empirical evidence. Kim et al. (2012) found in their study that consumers with strong moral beliefs were less likely to make a purchase decision about a counterfeit product when their cognitive resources were constrained, because they were unable to justify the purchase. Moral dilemmas lead to justifications, that is, strategies and techniques with which people rationalize and justify their deviant actions as normal, and people are more likely to engage in immoral behaviors when the justification succeeds (Schweitzer and Hsee 2002; Mazar et al. 2008). This way, individuals avoid the guilt of violating their ethical beliefs (Mitchell and Dodder 1983), and make these actions possible by justifying them before performing them (Sykes and Matza 1957). Justification helps to reduce the perceptions of negative social consequences that arise from moral beliefs, for instance, by denial of responsibility (Leisen and Nill 2001; Bian et al. 2016), which increases favorable consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products. Justification further succeeds by focusing on perceptions of benefits resulting from deviant behavior, which in turn positively influence attitudes, intentions, and behavior related to counterfeit and pirated products (Goles et al. 2008).

Based on the theory of cognitive dissonance and related empirical findings, the justification model suggests that morality increases the perceptions of negative social outcomes, which trigger justification processes. Justification increases the perception of positive individual outcomes. All four variables (morality, justification, positive perceptions, and negative perceptions) influence attitudes, intentions, and behavior.

Deontological–Teleological Model

The deontological–teleological model is theoretically embedded in ethical decision-making theories. In particular, it builds on the model of ethical decision-making in business research by Hunt and Vittell (1986) that suggests that ethical dilemmas are solved as a function of deontological evaluation (concerned with right vs. wrong) and teleological evaluation (considering consequences of the act). The model shows that individuals make decisions involving ethical issues by relying on both ethical norms (deontology) and perceived consequences of behavior (teleology), but oftentimes to different degrees. The model has found empirical support in different decision contexts such as consumer decision making (Vitell et al. 2001) and decision making by managers (Cole et al. 2000). The model has been applied in prior counterfeiting and piracy research, too, and researchers have examined the ethics of purchasing counterfeit and pirated products from both deontological and teleological perspectives (e.g., Gupta et al. 2004; Wagner and Sanders 2001).

From a teleological point of view, moral beliefs regarding piracy and counterfeiting are linked to the perceptions of negative consequences for society and others (Li and Seatton 2015). The deontological perspective asks whether the act of acquiring counterfeit or pirated products is right or wrong, and suggests simple rules to follow. Simple rules about what is wrong or right render any justifications irrelevant.

Hence, by referring to ethical decision-making theories and by combining deontological and teleological evaluations, the model suggests the following relationship between the variables. Morality decreases justification attempts (due to deontological evaluation) and increases the perception of negative social outcomes (due to teleological evaluation). Justification, in turn, increases the perception of positive individual outcomes, and all four variables (morality, justification, positive perceptions, and negative perceptions) influence attitudes, intentions, and behaviors regarding counterfeit and pirated products.

Perception Model

The perception model is theoretically embedded in the economic concepts of cost–benefit analysis and utility maximizing. It considers consumer behavior toward counterfeit and pirated products to be a simple utility-maximizing decision about whether illegal activities will pay off (i.e., whether the benefits outweigh the costs). This neo-classical approach to crime has been introduced by Becker (1968) and the cost–benefit approach has been widely applied in the study of criminal behavior (McCarthy 2002). People differ in their assessments of crime’s costs and benefits, in their preferences, perceptions, and strategies, and therefore they vary in their decisions to choose crime to satisfy their preferences. The approach has also been used in prior research that has developed economic models to explain decisions of consumers to acquire counterfeit or pirated products (e.g., Kobus and Krawzyk 2013). To come up with such a decision, consumers must weigh both the negative and positive outcomes of the acquisition of counterfeit or pirated products. Perceptions of negative social consequences intensify the moral beliefs and the dilemma that results from possible acquisition of counterfeit and pirated products. Perceptions of both positive individual consequences and negative social consequences enable a justification process that weighs both consequences against each other.

By referring to cost–benefit analysis and utility maximizing, the perception model is characterized by the perception of negative social outcomes, which trigger morality and justification, and the perception of positive individual outcomes, which trigger justification processes. All four variables (morality, justification, positive perceptions, and negative perceptions) influence attitudes, intentions, and behaviors regarding counterfeit and pirated products.

Figure 1 presents the three competing models. Because the relationship between attitude, intention, and behavior remains the same in all three models, the upper part in the figure presents the partial models that focus on the relationships between the four other constructs (morality, justification, positive perceptions, and negative perceptions) which vary in terms of order and signs, thereby addressing competing theoretical explanations. The lower part of the figure shows the full models. In the meta-analysis conducted for the present study, these full models were tested by means of meta-analytic path analysis, and the resulting model fits were compared to identify the model that best fits the empirical data.

Institutional and Social Context as Moderators of Morality Effects

Counterfeiting and piracy rates vary largely across countries. While reliable figures for counterfeit purchases are scant, the origin of these products indicates considerable variation in the availability of such products across countries, with 64% of all counterfeit brands originating from China (OECD and EUIPO 2016). The figures for software piracy are easier to generate, and they show that the piracy rate in the United States was as low as 18% in 2013, while it reached 90% in countries such as Zimbabwe, Georgia, and Moldova (Business Software Alliance 2014). The specific conditions in countries provide facilitators or inhibitors of counterfeit and pirate consumption, and can also explain why morality has a weaker or stronger influence on consumers depending on the differences in consumers’ moral engagement.

The theory of moral disengagement postulates that individuals restructure their understanding of their actions as less harmful or redefine their responsibility for certain behaviors depending on the social context (Moore 2008; Bandura 2002) because an individual’s ethical orientation and moral behavior are socially learned (Kohlberg 1984). Social and institutional factors therefore shape moral identities, increase moral identity salience and moral awareness, and, as such, influence responses to moral dilemmas (Weaver 2006). If an illicit behavior is common in a society, social learning theory (Bandura 1986) suggests that consumers acquire positive attitudes about these behaviors, which increases social acceptance of the behaviors in society. The more frequently that illicit behavior occurs, and the more likely it is to be socially accepted, the more likely consumers are to be morally disengaged, and the easier they will find justifications for moral dilemmas, which in turn makes it more likely that they will develop positive responses toward counterfeit and pirated products even if the purchase of these products is an illicit behavior.

The particular indicators used to capture the social and institutional context in this study are piracy rate and the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). The piracy rate is an estimate of the percentage of software titles in private business obtained illegally in a country in a particular year. It indicates the occurrence and, thus, social acceptance of such illicit behavior. The CPI ranks countries by the perceived levels of corruption, and it indicates the institutional context that facilitates or hinders illicit behavior through the acceptance of illicit behaviors.

Moderator Hypothesis

The negative influence of morality on (a) justification, (b) attitude, and (c) intentions becomes weaker the more frequently illicit behavior occurs in a society (i.e., with increasing piracy rate in a country) and the more likely it is to be accepted (i.e., with decreasing CPI).

Method

Meta-analysis is a way of combining results of many individual studies that address the same research question but provide different and even potentially conflicting findings. Meta-analysis can be applied as a tool for research synthesis that aggregates research findings in a quantitative way. Meta-analysis can further be applied as a tool to explain variations in findings by substantive or methodological variables that describe differences between studies. Meta-analysis can be used as an effective instrument for model development and testing by means of path analysis that is based on aggregated correlations. In the following, the sample of studies used for the meta-analysis, the coding procedure, and the analytical approach is described.

Data Collection and Coding

An exhaustive search of published and unpublished studies that deal with counterfeiting and piracy and that provide estimates for the relationships between the variables in the conceptual models was conducted. To identify relevant studies, review articles by Eisend and Schuchert-Güler (2006), Lee and Yoo (2009), Liang and Yan (2005), Peitz and Waelbroeck (2006), and Staake et al. (2009) were searched. Next, an ancestry tree search was applied by searching all articles referring to these review papers in the Web of Science database and on Google Scholar. Then, a keyword search of various electronic databases (e.g., Google Scholar, Business Source Complete, JSTOR, PsyINFO, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses) was performed using counterfeit*, pirate*, fake, and illicit combined with any of the labels of the variables in the conceptual models as keywords. Once a study was identified, its references were examined in a search for further studies. In addition, the CVs of major scholars in the area were reviewed and additional web searches were conducted. This study retrieval approach is consistent with recommendations in the literature, and it closely follows the steps taken in earlier meta-analyses published in the consumer and ethics research literature (e.g., Spangenberg et al. 2016; Simons et al. 2015). The search period covered all the manuscripts available as of May 2016. Because the oldest study was published in 1994, the studies cover 22 years of research on counterfeiting and piracy.

All the empirical studies that used consumer samples and that quantitatively measured any of the relationships between variables described in the conceptual models in the context of counterfeiting and piracy as defined above were included. This leads to the exclusion of the following types of papers and studies: Conceptual and theoretical papers (e.g., Peitz and Waelbroeck 2006), qualitative studies (e.g., Sinclair and Green 2016), or economic modeling studies (e.g., Vernik et al. 2011); studies that used samples other than consumer samples such as newspaper reports (e.g., Zamoon and Curley 2008); studies that investigated aggregate data instead of individual data, such as piracy rates per country (e.g., Andrés and Asongu 2013); and studies that did not provide appropriate or sufficient data for the purpose of the meta-analysis and for which necessary data could not be retrieved from authors (e.g., Taylor 2004). Apart from these exclusions, the meta-analysis was open to including any manuscripts written in English that provided appropriate empirical data. While this did not guarantee that all available studies were included, for several reasons (e.g., some journals are not listed in the major electronic databases), the literature search lead to a quite exhaustive list of papers with both published and unpublished studies, thus reducing the risk of a publication bias (see Appendix 3) and leading to an unbiased representation of the state of research in this area.

The search resulted in 196 usable manuscripts (see Appendix 1). Because some manuscripts provided more than one study, and others used the same sample, 207 independent samples were identified and used. The 207 samples provided in these manuscripts reported on 797 effect sizes describing any of the relationships between the concepts in the conceptual models. Two coders independently assigned the variables in each study to the concepts as defined above. Coding consistency was high (95%), and inconsistencies were resolved by discussion.

Effect Size Computation

The effect size metric selected for the meta-analysis was the correlation coefficient; positive coefficients indicate a positive relationship between two variables (e.g., a positive relationship between attitude and intention) and negative coefficients indicate a negative relationship (e.g., a negative relationship between morality and intention). The size of the coefficient indicates the strength of the relationship between any two variables. For studies that reported other measures, such as Student’s t or mean differences, those measures were converted to correlation coefficients following common guidelines for meta-analysis (e.g., Borenstein et al. 2009). If multivariate beta coefficients were provided, they were transformed according to recommendations by Peterson and Brown (2005). To control for biases due to these transformation procedures, differences between the outcomes of different transformation procedures were tested. The results did not indicate any significant differences. All correlations were adjusted for unreliability according to the procedures suggested in the literature (Hunter and Schmidt 2004). For studies that did not report the reliability or that used a single-item measure, the mean reliability for that construct across all samples was used.

Data Analysis

Effect Size Integration and Moderator Analysis

For the integration of effect sizes, the effect sizes were weighted by the inverse of their variance. Some papers reported multiple, relevant tests from a single sample, which can lead to dependencies among effect sizes from a single sample. These dependencies were accounted for by using a mixed-effects multilevel model to perform the meta-analytic procedures (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). By using a mixed-effects multilevel model, potential dependencies among effect sizes as well as the nested structure of meta-analytic data (i.e., multiple effect sizes from one study) could be addressed (Bijmolt and Pieters 2001). Because the variance of the error term is given, this is called a variance-known model for meta-analysis. The unconditional model (or intercept-only model) reflects a random-effects model for meta-analysis.

A model including moderators is termed a conditional model. The conditional model is a mixed-effects model because fixed effects for the moderators are considered in addition to random components. The indicators used to capture the social and institutional context in the model were piracy rate and the CPI. The piracy rate was gathered from the Business Software Alliance and is an estimate of the percentage of software titles in private business obtained illegally in a country in a particular year, generated by the sampling of actual business computers in each country (Business Software Alliance 2014). It indicates the occurrence and, thus, social acceptance of such illicit behavior. The CPI ranks countries by the perceived levels of corruption as assessed by experts and opinion surveys on a scale from 100 (very clean) to 0 (highly corrupt) every year (Transparency International 2015), and it indicates the institutional context that facilitates or hinders illicit behavior through the acceptance of illicit behaviors. Both piracy rate and CPI were assigned by the country and year of the study.Footnote 1 As a control variable, a dummy variable was added that distinguishes between counterfeiting and piracy as defined above. The specification of the conditional model is described in Appendix 2.

Path Model

To investigate the suggested models, a meta-analytic correlation matrix was constructed. All variable relationships in the meta-analysis were based on at least three estimates, which is in line with most other meta-analytic path model studies that also required three or more estimates for each relationship (e.g., Palmatier et al. 2006). This correlation matrix was applied as input to structural equation modeling analyses using the maximum likelihood method. All constructs were measured by a single indicator, and error variances for the indicators were fixed at zero because measurement errors had already been considered by reliability adjustments. The precision of parameter estimates was tested through the harmonic mean (N = 2049), which was determined by using the cumulative sample comprising each entry in the correlation matrix, following recommendations in the literature (Bergh et al. 2016). The mediation effects of morality on consumer response variables were assessed using the procedures that Iacobucci et al. (2007) outlined for evaluating mediation in structural equation models. To this end, the proportion of indirect to total effects of morality on attitudes, intentions, and behavior was computed.

Results

Table 1 presents the meta-analytic correlation matrix with the number of effect sizes and the cumulative sample size for each entry. The matrix is based on 797 correlations.

Path Models

Table 2 present the results for the alternative path models. Modification indices suggested the addition of a direct path from attitude to behavior for all three models, which theoretically makes sense; the idea of a mediating effect of attitude on behavior via intentions has been criticized for ignoring important factors such as habits and emotions (Ortiz de Guinea and Markus 2009). In fact, research has shown that the effect of attitude on behavior can be direct, and that the mediation via intention depends on the behavior domain (e.g., Bentler and Speckart 1981). Attitudes can stimulate an action with little or no reasoning, such as in routine response behavior (Bagozzi et al. 1989; Rook 1987).

The models are not nested, and thus it could not be tested how the models fit against each other. However, the fit indices clearly indicate that the deontological–teleological model fits the data best (χ2/df = 2.661/1, p = .103, CFI = 1.000, GFI = 1.000, AGFI = .990, RMSEA = .028), while both other models show low to unacceptable model fit. Hence, the deontological–teleological model represents the best and most generalizable theoretical account for explaining the relationship between morality and consumer responses.

Figure 2 depicts the best-fitting model. All reported paths are significant at p < .05, except for the relationships between justification and intentions, negative social outcomes and intentions, and morality and behavior (indicated by path coefficients in italics). As suggested by the model, morality increases the perceptions of negative social outcomes (due to teleological evaluation) and decreases justification (due to deontological evaluation). Justification reduces the perception of negative social outcomes and increases the perception of positive individual outcomes. All four variables influence attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Morality influences attitudes and intentions directly and indirectly, but the influence of morality on behavior is not direct, and is mediated via justification, perceptions, attitudes, and intentions. The proportion of indirect to total effects of morality on attitudes, intentions, and behavior indicates that 81% of the effect of morality on attitudes is indirect, while 48% of the effect on intentions and 97% of the effect on behavior is indirect. That is, a considerable amount of the effect of morality on the outcome variables is explained by the suggested mediating processes via justification and perceptions.

Results for the deontological–teleological model. Standardized path coefficients are provided. The coefficients are significant at p < .05 (two-tailed), except for the coefficients in italics (paths from justification to intention, from negative social outcomes to intention, and from morality to behavior). Model fit: χ2/df = 2.661/1, p = .103, CFI = 1.000, GFI = 1.000, AGFI = .990, RMSEA = .028

As for the effects of perceptions, the results are mainly in line with the predictions of the model. Perceptions of negative outcomes reduce consumer responses, and perceptions of positive outcomes increase intentions and behavior, but perceptions of positive outcomes decrease attitudes. This negative effect on attitudes might be due to another justification process (i.e., positive individual outcomes need to be justified against negative social outcomes, leading to stated negative evaluations); but even after considering this surprising negative effect of perceived positive outcomes on attitudes, the total effects (i.e., direct and indirect) of positive individual outcomes on intentions and behavior remain positive and significant.

Moderator Analysis

Table 3 presents the results of the moderator analysis. The findings reveal three significant interaction effects that provide partial support for the hypotheses about the moderating effects of the institutional and social context. For illustration purposes, the interaction effects are presented in Fig. 3. The figures show how the effect sizes related to attitude, intention, and justification change (i.e., become smaller or bigger) when piracy rates or CPI increase. The straight line in each figure indicates the changes for the focal dependent variable (attitude, intention, or justification), while the dotted line indicates the changes for the set of remaining dependent variables.

As expected, the effects of morality on attitude becomes less negative (i.e., weaker) with an increasing piracy rate. The negative effects on intention become stronger with increasing CPI (note that low levels of CPI indicate high corruption in a country and vice versa). The overall negative effect of morality on justification becomes less negative with lower CPI and can even turn positive in countries with very low CPI. The control variable shows that CPI and piracy rate have the same influences for both counterfeit and pirated products. These findings partly support the moderator hypothesis: The negative influence of morality on attitude becomes weaker the more frequently illicit behavior occurs in a society (i.e., with increasing piracy rate in a country). The negative influence of morality on justification and intentions becomes weaker the more likely illicit behavior is to be accepted in a society (i.e., with decreasing CPI) (Table 3).

Discussion and Implications

This meta-analysis synthesizes the research on the influence of morality on attitudes, intentions, and behavior toward counterfeit and pirated products. It tests competing morality-justification processes that explain how consumers respond to pirated and counterfeit product purchases in light of ethical concerns, and it shows how the institutional and social context of consumers explains the differences in consumer responses to morality issues raised by counterfeit and pirated products. The findings provide both theoretical and practical implications.

Explaining Morality Effects

Several theories have been used to explain how morality influences consumer responses to counterfeit and pirated products. The meta-analytic findings show that the major mechanism that explains morality effects, that is, the model that is best in line with empirical findings, is based on the deontological–teleological model (Hunt and Vitell 1986). The teleological element in the model refers to the fact that morality leads to perceptions of social consequences of counterfeiting and piracy that influence consumer responses. Morality reduces justification because deontological rules render justification as irrelevant. The findings are relevant to future research on morality in piracy and counterfeiting because they indicate the theoretical perspective that provides the highest degree of generalizability and that promises high explanatory power for empirical findings.

The justification model has been applied in prior research, but the meta-analysis findings in the present study suggest that morality does not always increase the need for justification that is proposed in the justification model. However, moderator analysis shows that the effects of morality on justification depend on the institutional and social context, and that under certain circumstances, morality can in fact increase justification through moral disengagement and social learning (Moore 2008; Bandura 2002; Kohlberg 1984). The perception that corruption is widespread reduces the deontological effect of morality, makes justifications more likely, and reduces the negative effect of morality on intentions. In societies where illicit behavior is socially accepted (as indicated by high levels of corruption), consumers become morally disengaged, they find justifications for moral dilemmas easier, and they show less negative or even positive responses toward counterfeit and pirated products. Hence, while the meta-analytic findings provide overall support for the deontological–teleological model, the justification model might apply in certain cultural contexts. The meta-analytic data set cannot be used for testing these competing models for subgroups of country data. Further cross-cultural research studies should therefore investigate the culture-dependent fit of the competing models to answer the questions whether the deontological–teleological model does indeed not work as well in societies where corruption is rife and piracy rates are high and whether the justification model works better in these societies.

The Moderating Effect of the Institutional and Social Context

The findings in the present study regarding the context-sensitivity of the justification model contribute to the ongoing debate about the applicability of scientific knowledge that has been developed and tested in a Western context (Burgess and Steenkamp 2006) and the context-sensitivity of indigenous theorizing (Whetten 2009). The deontological–teleological model has been developed and empirically tested mostly in a Western context, that is, in countries with low corruption and piracy rates. With the increasing globalization of scholarship, researchers have started to question whether theories developed in Western contexts are valid and generalizable across the globe or are contingent on cultural contexts (Burgess and Steenkamp 2006; Steenkamp 2005). The global applicability of a theory can be assessed by the overall fit of the theoretical model to the data and the strength and direction of the effects of structural relations within the model. The findings of this meta-analysis show that the deontological–teleological model is a comprehensive model that can describe morality effects with a high degree of generalizability. However, the model should not be generalized to societies that significantly differ from Western cultures without considering alternative theoretical explanations of morality effects.

The moderator results provide an additional explanation for the variation in prior morality effects. Some researchers have found evidence that more-strongly-held moral beliefs that acquiring counterfeit and pirated products is wrong, unethical, or immoral negatively influences attitudes toward such products, intentions to acquire them, as well as actual behavior (e.g., Higgins 2005; Cesareo and Pastore 2014). However, other researchers could not find support for the effects of morality on purchases of counterfeit and pirated products (e.g., Al-Rafee and Cronan 2006; Higgins et al. 2007) or could find support only for certain conditions or samples (e.g., Tjiptono et al. 2016; Shoham et al. 2008). In line with the theory of moral disengagement and social learning, the more frequently illicit behavior occurs in a society and the more likely it is to be socially accepted, the more likely consumers will be morally disengaged, the easier they will find justifications for moral dilemmas, and the more likely they will be to develop positive responses to counterfeit and pirated products. To understand the counterfeiting and piracy behavior of consumers more thoroughly, future researchers should therefore consider context variables and cultural moderators. These variables explain why prior findings of morality effects vary: justifications and their responses are conditional on the particular cultural context. Such context-dependent facilitators and inhibitors of justifications can explain variations in morality effects beyond variations in individual moral propensity (Kohlberg 1984). As a result, the varying outcomes of morality can further explain the variation in incidents of counterfeiting and piracy across countries. In countries with high piracy rates and high corruption, consumers more easily find justifications to deal with morality issues. Next to the moderating effects on justifications, the high proportion of mediation via justification processes in the meta-analysis further suggests that moral consumer behavior should be investigated together with possible justifications of consumers in order to enhance the explanatory power of future research studies.

Practical Implications

A practical implication of these findings for anti-counterfeiting and piracy measures is that justifications can be used as a lever to support morality effects. Depending on the institutional and social context, morality effects can be enhanced by either increasing the perceptions of negative social consequences in a context where counterfeiting and piracy is less socially accepted (e.g., by providing information about the harm to the economy and society) or by disturbing the justification process in an environment where the social acceptance of counterfeiting and piracy is high (e.g., by emphasizing risk and low quality and thus reducing the perceived individual benefits).

Limitations and Future Research

The study has some limitations common to meta-analytic techniques that both benefit and suffer from a high degree of generalization. One particular limitation that is worthwhile to mention in the context of this meta-analysis arises from restricting the sample to studies published in English. While such language bias is broadly accepted in meta-analysis for practical and substantial reasons, the use of country-related moderator variables (here: CPI and piracy rates) brings about the question whether the meta-analytic sample is indeed representative for all countries in the world or whether it over-represents countries from the Western hemisphere, in particular English-speaking countries. Although such bias does not necessarily negate the results of this meta-analysis, it might affect the power of test results.

A related problem refers to the assumed measurement invariance across countries, which is required in order to explain the observed differences in effect sizes as culture-dependent instead of depending on the way measures (e.g., attitude and morality) perform across countries (Steenkamp and Baumgartner 1998). As a consequence of the level of data aggregation in meta-analysis, meta-analytic effect sizes do not allow testing for measurement invariance. This problem has so far been ignored in meta-analyses that test for differences across countries. Future meta-analytic studies should take this problem into account when applying country moderator variables to explain the variance in effect sizes.

Notes

Considering only studies that could be assigned to a single country, the meta-analytic data were collected for 44 different countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, China, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Russia, Saudi-Arabia, Serbia, Singapore, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Sudan, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, and Vietnam.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracin, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 173–221). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Al-Rafee, S., & Cronan, T. P. (2006). Digital piracy: Factors that influence attitude toward behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(3), 237–259.

Andrés, A. R., & Asongu, S. A. (2013). Fighting software piracy: Which governance tools matter in Africa? Journal of Business Ethics, 118(3), 667–682.

Bagozzi, R. P., Baumgartner, J., & Yi, Y. (1989). An investigation into the role of intentions as mediators of the attitude-behavior relationship. Journal of Economic Psychology, 10, 35–62.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31(2), 101–119.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217.

Bentler, P. M., & Speckart, G. (1981). Attitudes ‘cause’ behaviors: A structural equation analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(2), 226–238.

Bergh, D. D., Aguinis, H., Heavey, C., Ketchen, D. J., Boyd, B. K., Su, P., et al. (2016). Using meta-analytic structural equation modeling to advance strategic management research: Guidelines and an empirical illustration via the strategic leadership-performance relationship. Strategic Management Journal, 37(3), 477–497.

Bian, X., Wang, K.-Y., Smith, A., & Yannopoulo, N. (2016). New insights into unethical counterfeit consumption. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 4249–4258.

Bijmolt, T. H. A., & Pieters, R. G. M. (2001). Meta-analysis in marketing when studies contain multiple measurements. Marketing Letters, 12(2), 157–169.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Computing effect sizes for meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley.

Burgess, S. M., & Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M. (2006). Marketing renaissance: How research in emerging markets advances marketing science and practice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(4), 337–356.

Business Software Alliance. (2014). The compliance gap. BSA global software survey. Washington, DC: Business Software Alliance.

Cesareo, L., & Pastore, A. (2014). Consumers’ attitude and behavior towards online music piracy and subscription-based services. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(6/7), 515–525.

Chen, M.-F., Pan, C.-T., & Pan, M.-C. (2009). The joint moderating impact of moral intensity and moral judgment on consumer’s use intention of pirated software. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(3), 361–373.

Cole, D., Sirgy, J. M., & Bird, M. M. (2000). How do managers make teleological evaluations in ethical dilemmas? testing part of and extending the Hunt–Vitell model. Journal of Business Ethics, 26(3), 259–269.

Eisend, M., & Schuchert-Güler, P. (2006). Explaining counterfeit purchases—A review and preview. Academy of Marketing Science Review. Rerieved February 28, 2007 from www.amsreview.org/articles/eisend12-06.pdf.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Goles, T., Jayatilaka, B., George, B., Parsons, L., Chambers, V., Taylor, D., et al. (2008). Softlifting: Exploring determinants of attitude. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(4), 481–499.

Grossman, G. M., & Shapiro, C. (1988). Foreign counterfeiting of status goods. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102, 79–100.

Gupta, P. B., Gould, S. J., & Pola, B. (2004). ‘To pirate or not to pirate’: A comparative study of the ethical versus other influences on the consumer’s software acquisition-mode decision. Journal of Business Ethics, 55(3), 255–274.

Higgins, G. E. (2005). Can low self-control help with the understanding of the software piracy problem? Deviant Behavior, 26(1), 1–24.

Higgins, G. E., Fell, B. D., & Wilson, A. L. (2007). Low self-control and social learning in understanding students’ intentions to pirate movies in the United States. Social Science Computer Review, 25(3), 339–357.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6(1), 5–16.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis. Correcting error and bias in research findings (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Iacobucci, D., Saldanha, N., & Deng, X. (2007). A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 139–152.

Kim, J., Kim, J.-E., & Park, J. (2012). Effects of cognitive resource availabiltiy on consumer decision in involving counterfeit products: The role of perceived justification. Marketing Letters, 23(3), 869–881.

Kobus, M., & Krawzyk, M. (2013). Piracy as an ethical decision. Working Paper No. 22/2013. Faculty of Economic Sciences, University of Warsaw, Warsaw.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development: Moral stages and the life cycle (Vol. 2). San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Lee, S.-H., & Yoo, B. (2009). A review of the determinants of counterfeiting and piracy and the proposition for future research. Korean Journal of Policy Studies, 24(1), 1–38.

Leisen, B., & Nill, A. (2001). Combating Product Counterfeiting: An Investigation into the Likely Effectiveness of a Demand-Oriented Approach. Paper presented at the American Marketing Association Winter Educators’ Conference.

Li, T., & Seatton, B. (2015). Emerging consumer orientation, ethical perceptions, and purchase intention in the counterfeit smartphone market in China. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 27(1), 27–53.

Liang, Z., & Yan, Z. (2005). Software piracy among college students: A comprehensive review of contributing factors, underlying processes, and tackling strategies. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32(2), 115–140.

Lysonski, S., & Durvasula, S. (2008). Digital piracy of MP3s: Consumer and ethical predispositions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(3), 167–178.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A self-concept maintenance theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

McCarthy, B. (2002). New economics of sociological criminology. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 417–442.

Mitchell, J., & Dodder, R. A. (1983). Types of neutralization and types of delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 12(4), 307–318.

Moore, C. (2008). Moral disengagement in processes of organizational corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(1), 129–139.

Morris, R. G., & Higgins, G. E. (2009). Neutralizing potential and self-reported digital piracy. Criminal Justice Review, 34(2), 173–195.

OECD & EUIPO. (2016). Trade in counterfeit and pirated goods. Mapping the economic impact. Paris: OECD.

Ortiz de Guinea, A., & Markus, M. L. (2009). Why break the habit of a lifetime? rethinking the roles of intention, habit, and emotion in continuing information technology use. MIS Quarterly, 33(3), 433–444.

Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., Grewal, D., & Evans, K. R. (2006). Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing, 70(October), 136–153.

Peitz, M., & Waelbroeck, P. (2006). Piracy of digital products: A critial review of the theoretical literature. Information Economics and Policy, 18, 449–476.

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 175–181.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models. Application and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rook, D. W. (1987). The buying impulse. Journal of Consumer Research, 14, 189–199.

Schweitzer, M., & Hsee, C. K. (2002). Stretching the truth: Elastic justification and motivated communication of uncertain information. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 25(2), 185–201.

Shoham, A., Ruvio, A., & Davidow, M. (2008). (Un)Ethical consumer behavior: Robin Hoods or plain hoods? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(4), 200–210.

Simons, T., Leroy, H., Collewaert, V., & Masschelein, S. (2015). How leader alignment of words and deeds affects followers: A meta-analysis of behavioral integrity research. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(4), 831–844.

Sinclair, G., & Green, T. (2016). Download or stream? Steal or buy? Developing a typology of today’s music consumer. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15, 3–14.

Spangenberg, E. R., Kareklas, I., Devezer, B., & Sprott, D. E. (2016). A meta-analytic synthesis of the question-behavior effect. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 26(3), 441–458.

Staake, T., Thiesse, F., & Fleisch, E. (2009). The emergence of counterfeit trade: A literature review. European Journal of Marketing, 43(3/4), 320–349.

Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M. (2005). Moving out of the U.S. silo: A call to arms for conducting international marketing research. Journal of Marketing, 69, 6–8.

Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 78–90.

Sykes, G., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 664–670.

Sutton, A. J. (2009). Publication bias. In H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed., pp. 435–452). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Taylor, S. L. (2004). Music piracy—Differences in the ethical perceptions of business majors and music business majors. Journal of Education for Business, 79(5), 306–310.

Tjiptono, F., Aril, D., & Aril, V. (2016). Gender and digital privacy: Examining determinants of attitude toward digital piracy among youths in an emerging market. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(2), 168–178.

Transparency International. (2015). Corruption Perceptions Index 2015. Brussels: Transparency International.

Vernik, D. A., Purohit, D., & Desai, P. S. (2011). Music downloads and the flip side of digital rights management. Marketing Science, 30(6), 1011–1027.

Vitell, S. J., Singhapakdi, A., & Thomas, J. (2001). Consumer ethics: An application and empirical testing of the Hunt–Vitell theory of ethics. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(2), 153–178.

Wagner, S. C., & Sanders, L. G. (2001). Considerations in ethical decision making and software piracy. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(1), 161–167.

Weaver, G. R. (2006). Virtue in organizations: Moral identity as a foundation for moral agency. Organization Studies, 27(3), 341–368.

Whetten, D. A. (2009). An examination of the interface between context and theory applied to the study of chinese organizations. Management and Organization Review, 5(1), 29–55.

Zamoon, S., & Curley, S. P. (2008). Ripped from the headlines: What can the popular press teach us about software piracy? Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 515–533.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Appendices

Appendix 1: List of Studies Included in the Meta-analysis

-

1.

Abid, M., & Abbasi, M. (2014). Antecedents and Outcomes of Consumer Buying Attitude: The Case of Pakistani Counterfeit Market. Indian Journal of Science Research, 8(1), 169–176.

-

2.

Abkulut, Y. (2014). Exploration of the Antecedents of Digital Piracy Through a Structural Equation Model. Computers & Education, 78(9), 294–305.

-

3.

Al-Jabri, I., & Abdul-Gader, A. (1997). Software Copyright Infringements: An Exploratory Study of the Effects of Individual and Peer Beliefs. Omega—International Journal of Management Science, 25(3), 335–344.

-

4.

Al-Rafee, S. (2002). Digital Piracy: Ethical Decision Making. Unpublished Thesis, University of Arkansas,

-

5.

Al-Rafee, S., & Cronan, T. P. (2006). Digital Piracy: Factors that Influence Attitude Toward Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(3), 237–259.

-

6.

Alam, S. S., Ahmad, A., Ahmad, M. S., & Hashim, N. M. H. N. H. (2011). An Empirical Study of an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour Model for Pirated Software Purchase. World Journal of Management, 3(1), 1–11.

-

7.

Albarq, A. N. (2015). Counterfeit Products and the Role of the Consumer in Saudi Arabia. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 5(12), 819–827.

-

8.

Alfadl, A. A., Ibrahim, M. I. M., & Hassali, M. A. (2012). Consumer Behaviour Towards Counterfeit Drugs in a Developing Country. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research, 3(3), 165–172.

-

9.

Ali, M., & Jamal, M. F. (2013). Exploring Relationship Among Factors of Willingness of Consumer Toward Counterfeit Products in Pakistan. International Journal of Management & Organizational Studies, 2(1), 66–72.

-

10.

Ang, S. H., Cheng, P. S., Lim, E. A. C., & Tambyah, S. K. (2001). Spot the Difference: Consumer Responses Towards Counterfeits. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(3), 219–235.

-

11.

Bateman, C. R., Valentine, S., & Rittenburg, T. (2013). Ethical Decision Making in a Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Situation: The Role of Moral Absolutes and Social Consensus. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(2), 229–240.

-

12.

Bhardwaj, V. (2010). The Effects of Consumer Orientations on the Consumption of Counterfeit Luxury Brands. Unpublished Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville,

-

13.

Bilal, A., Khan, M. A., Ahmad, N., & Ahmed, W. (2012). Influence of Personality Traits on Consumers’ Intention to Buy the Fashion Counterfeits: An Empirical Investigation with Special Reference to Young Consumers in Pakistan. Asian Journal of Business Management, 4(3), 303–309.

-

14.

Blake, R. H., & Kyper, E. S. (2013). An Investigation of the Intention to Share Media Files over Peer-to-peer Networks. Behaviour & Information Technology, 32(4), 410–422.

-

15.

Budiman, S. (2012). Analysis of Consumer Attitudes to Purchase Intentions of Counterfeiting Bag Product in Indonesia. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences, 1(1), 1–12.

-

16.

Butt, A. (2006). Comparative Analysis of Software Piracy Determinants among Pakistani and Canadian University Students: Demographics, Ethical Attitudes and Socio-Economic Factors. Unpublished Thesis, Simon Fraser University,

-

17.

Carpenter, J. M., & Edwards, K. E. (2013). U.S. Consumer Attitudes toward Counterfeit Fashion Products. Journal of Textile and Apparel, Technology and Management, 8(1), 1–16.

-

18.

Cesareo, L., & Pastore, A. (2014). Consumers’ Attitude and Behavior Towards Online Music Piracy and Subscription-Based Services. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(6/7), 515–525.

-

19.

Chaipoopirutana, S., & Combs, H. (2011). An Empirical Study of Consumer Attitudes Toward Software Piracy. Asian Pacific Advances in Consumer Research, 9(1), 327–380.

-

20.

Chang, M. K. (1998). Predicting Unethical Behavior: A Comparison of the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1825–1834.

-

21.

Chaudhry, P. E., Hill, R. P., Stumpf, S. A., & Yalcinkaya, G. (2011). Consumer Complicity Across Emerging Markets. Advances in International Marketing, 22(1), 223–239.

-

22.

Chaudhry, P. E., & Stumpf, S. A. (2008). The Role of Ethical Ideologies, Collectivism, Hedonic Shopping Experience and Attitudes as Influencers of Consumer Complicity with Counterfeit Products.

-

23.

Chaudhry, P. E., & Stumpf, S. A. (2011). Consumer Complicity with Counterfeit Products. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(2), 139–151.

-

24.

Chen, M.-F., Pan, C.-T., & Pan, M.-C. (2009). The Joint Moderating Impact of Moral Intensity and Moral Judgment on Consumer’s Use Intention of Pirated Software. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(3), 361–373.

-

25.

Chiou, J.-S., Huang, C.-y., & Lee, H.-h. (2005). The Antecedents of Music Piracy Attitudes and Intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(2), 161–174.

-

26.

Chiou, W.-B., Wan, P.-H., & Wan, C.-S. (2012). A New Look at Software Piracy: Soft Lifting Primes an Inauthentic Sense of Self, Prompting Further Unethical Behavior. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 70(2), 107–115.

-

27.

Chiu, W., Lee, K.-Y., & Won, D. (2014). Consumer Behavior Toward Counterfeit Sporting Goods. Social Behavior and Personality, 42(4), 615–624.

-

28.

Chiu, W., & Leng, H. K. (2016). Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Sporting Goods in Singapore and Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(1), 23–36.

-

29.

Chok, M. (2008). Consumers Behaviours and Pirated Products. Unpublished Thesis, University of Malaysia,

-

30.

Cockrill, A., & Goode, M. M. H. (2012). DVD Pirating Intentions: Angels, Devils, Chancers and Receivers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(1), 1–10.

-

31.

Coyle, J. R., Gould, S. J., Gupta, P., & Gupta, R. (2009). ‘To Buy or To Pirate’: The Matrix of Music Consumers’ Acquisition-Mode Decision Making. Journal of Business Research, 62(10), 1031–1037.

-

32.

Cronan, T. P., & Al-Rafee, S. (2008). Factors that Influence the Intention to Pirate Software and Media. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(4), 527–545.

-

33.

Cuevas, F. (2010). Student Awareness of Instituional Policy and It’s Effect on Peer to Peer File Sharing & Piracy Behavior. Unpublished Thesis, Florida State University,

-

34.

d’Astous, A., Colbert, F., & Montpetit, D. (2005). Music Piracy on the Web - How Effective Are Anti-Piracy Arguments? Evidence from the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Consumer Policy, 28(3), 289–310.

-

35.

De Cat, D. (2010). Counterfeiting and Consumer Behavior. Unpublished Thesis, University of Ghent,

-

36.

De Matos, C. A., Ituassu, C. T., & Rossi, C. A. V. (2007). Consumer Attitudes Toward Counterfeits: A Review and Extension. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(1), 36–47.

-

37.

Debby, L. H. M. (2007). Internet Piracy - A User Behavioral Perspective. Unpublished Thesis, City University of Hong Kong,

-

38.

Dionísio, P., Leal, C., Pereira, H., & Salgueiro, M. F. (2013). Piracy Among Undergraduate and Graduate Students: Influences on Unauthorized Book Copies. Journal of Marketing Education, 35(2), 191–200.

-

39.

Dwiyanto, M. Y. (2011). The Influence of Ethics and Materialism of Consumer Buying Interest in Counterfeit Fashion Goods. Padjadjaran University.

-

40.

Eisend, M., & Schuchert-Güler, P. (2008). Do Consumers Mind Buying Illicit Goods? The Case of Counterfeit Purchases. European Advances in Consumer Research, 8(1), 124–125.

-

41.

Faria, A. A. (2013). Consumer Attitudes Towards Counterfeit Goods: The Case of Canadian and Chines Consumers. Unpublished Thesis, University of Guelph,

-

42.

Fernades, C. (2013). Analysis of Counterfeit Fashion Purchase Behaviour in UAE. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 17(1), 85–97.

-

43.

Fetscherin, M. (2009). Importance of Cultural and Risk Aspects in Music Piracy: A Cross-National Comparison Among University Students. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 10(1), 42–55.

-

44.

Forman, A. E. (2009). An Exploratory Study on the Factors Associated with Ethical Intention of Digital Piracy. Unpublished Thesis, Nova Southeastern University,

-

45.

Francis, J. E., Burgess, L., & Lu, M. (2015). Hip to Be Cool: A Gen Y View of Counterfeit Luxury Products. Journal of Brand Management, 22(7), 588–602.

-

46.

Furnham, A., & Valgeirsson, H. (2007). The Effect of Life Values and Materialism on Buying Counterfeit Products. Journal of Socio-Economics, 36(5), 677–685.

-

47.

Glass, R. S., & Wood, W. A. (1996). Situational Determinants of Software Piracy: An Equity Theory Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(1), 1189–1198.

-

48.

Goles, T., Jayatilaka, B., George, B., Parsons, L., Chambers, V., Taylor, D., et al. (2008). Softlifting: Exploring Determinants of Attitude. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(4), 481–499.

-

49.

Gopal, R. D., & Sanders, L. G. (1997). Preventive and Deterrent Controls for Software Piracy. Journal of Management Information Systems, 13(4), 29–47.

-

50.

Gopal, R. D., & Sanders, L. G. (1998). International Software Piracy: Analysis of Key Issues and Impacts. Information Systems Research, 9(4), 380–397.

-

51.

Gopal, R. D., Sanders, L. G., Bhattacharjee, S., Agrawal, M., & Wagner, S. C. (2004). A Behavioral Model of Digital Music Piracy. Journal of Organizational Computing & Electronic Commerce, 14(2), 89–105.

-

52.

Ha, S., & Lennon, S. J. (2006). Purchase Intent for Fashion Counterfeit Products: Ethical Ideologies, Ethical Judgments, and Perceived Risks. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 24(4), 297–315.

-

53.

Hamelin, N., Nwankwo, S., & El Hadouchi, R. (2013). ‘Faking Brands’: Consumer Responses to Counterfeiting. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 12(3), 159–170.

-

54.

Haque, A., Rahman, S., & Khatibi, A. (2010). Factors Influencing Consumer Ethical Decision Making of Purchasing Pirated Software: Structural Equation Modeling on Malaysian Consumer. Journal of International Business Ethics, 3(1), 30–40.

-

55.

Harrington, S. J. (1996). The Effects of Codes of Ethics and Personal Denial of Responsibility on Computer Abuse Judgments and Intentions. MIS Quarterly, 20(3), 257–278.

-

56.

Harrington, S. J. (2000). Software Piracy: Are Robin Hood and Responsibility Denial at Work? Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2000 IRMA International Conerence, Anchorage, Alaska, USA,

-

57.

Harrington, S. J. (2002). Software Piracy: Are Robin Hood and Responsibility Denial at Work? In A. Salehnia (Ed.), Ethical Issues of Information Systems (pp. 177–188). Hershey: IRM Press.

-

58.

Hashim, M. J. (2011). Nudging the Digital Pirate: Piracy and the Conversion of Pirates to Paying Customers. Unpublished Thesis, Purdue University,

-

59.

Heidarzadeh Hanzaee, K., & Taghipourian, M. J. (2012). Attitudes toward Counterfeit Products and Generation Differentia. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, 4(9), 1147–1154.

-

60.

Hendriana, E., Mayasari, A. P., & Gunadi, W. (2013). Why Do College Students Buy Counterfeit Movies? International Journal of e-Education, e-Management and e-Learning, 3(1), 62–67.

-

61.

Hendricks, K. (2013). An Empirical Investigation of Internet Piracy Among College Students. Unpublisehd Thesis, Texas A&M University,

-

62.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Henning, V., & Sattler, H. (2007). Consumer File Sharing of Motion Pictures. Journal of Marketing, 71(4), 1–18.

-

63.

Hidayat, A., & Diwasari, A. H. A. (2013). Factors Influencing Attitudes and Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Luxury Brands among Indonesian Consumers. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 5(4), 143–151.

-

64.

Higgins, G. E. (2005). Can Low Self-Control Help with the Understanding of the Software Piracy Problem? Deviant Behavior, 26(1), 1–24.

-

65.

Higgins, G. E. (2007). Digital Piracy: An Examination of Low Self-Control and Motivation Using Short-term Longitudinal Data. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10(4), 523–529.

-

66.

Higgins, G. E., Fell, B. D., & Wilson, A. L. (2007). Low Self-Control and Social Learning in Understanding Students’ Intentions to Pirate Movies in the United States. Social Science Computer Review, 25(3), 339–357.

-

67.

Higgins, G. E., Wilson, A. L., & Fell, B. D. (2005). An Application of Detterence Theory to Software Piracy. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 12(3), 166–184.

-

68.

Hinduja, S. (2000). Broadband Connectivity and Software Piracy in a University Setting. Unpublished Thesis, Michigan State University,

-

69.

Hinduja, S. (2001). Correlates of Internet Software Piracy. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 17(4), 369–382.

-

70.

Hinduja, S. (2003). Trends and Patterns Among Online Software Pirates. Ethics and Information Technology, 5(1), 49–61.

-

71.

Hinduja, S. (2007). Neutralization Theory and Online Software Piracy: An Empirical Analysis. Ethics and Information Technology, 9(3), 187–204.

-

72.

Hinduja, S. (2008). Deindividuation and Internet Software Piracy. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11(4), 391–398.

-

73.

Huang, C.-Y. (2005). File Sharing as a Form of Music Consumption. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 9(4), 37–55.

-

74.

Huang, J.-H., Lee, B. C. Y., & Ho, S. H. (2004). Consumer Attitude toward Gray Market Goods. International Marketing Review, 21(6), 598–614.

-

75.

Huang, Y.-M. (2009). The Effects of Unethical Beliefs and Counterfeit Attitudes on Purchase Intentions of Non-deceptive Counterfeit Luxury Brands: A Cross-cultural Comparison Between United States and Taiwan. Unpublished Thesis, Alliant International University,

-

76.

Hymel, J. P. (2013). An Investigation of Consumer Sentiments Regarding Counterfeit Luxury Apparel and Personal Electronics Goods. Unpublished Thesis, Lawrence Tech University,

-

77.

Jirotmontree, A. (2013). Business Ethics and Counterfeit Purchase Intention: A Comparativ Study on Thais and Singaporeans. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 25(4), 281–288.

-

78.

Joji, A. N., & Joseph, J. C. (2015). Attitude and Purchase Intention Towards Counterfeit Products: An Enquiry among Consumers in India. Vilakshan: XIMB Journal of Management, 12(2), 21–40.

-

79.

Jun, S., Liang, S., Qiong, W., & Jian, W. (2012). The Relationship Between the Willingness of Buying Counterfeit Goods and Consumer Personality Traits. Paper presented at the 2012 International Conference on Public Management,

-

80.

Kampmann, M. W. (2010). Online Piracy and Consumer Affect. To Pay or Not to Pay. Unpublished Thesis, University of Twente,

-

81.

Khalid, M., & Rahman, S. U. (2015). Word of Mouth, Perceived Risk and Emotions, Explaining Consumers’ Counterfeit Products Purchase Intention in a Developing Country: Implications for Local and International Original Brands. Advances in Business-Related Scientific Journal, 6(2), 145–160.

-

82.

Kim, H., & Karpova, E. (2010). Consumer Attitudes Toward Fashion Counterfeits: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 28(2), 79–84.

-

83.

Kim, J.-E. (2009). The Influence of Moral Emotions in Young Adulty’ Moral Decision Making: A Cross-Cultural Examination. Unpublished Thesis, University of Minnesota,

-

84.

Kim, J.-E., Cho, H. J., & Johnson, K. K. (2009). Influence of Moral Affect, Judgment, and Intensity on Decision Making Concerning Counterfeit, Gray-Market, and Imitation Products. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 27(3), 211–226.

-

85.

Kim, J., Kim, J.-E., & Park, J. (2012). Effects of Cognitive Resource Availabiltiy on Consumer Decision in Involving Counterfeit Products: The Role of Perceived Justification. Marketing Letters, 23(3), 869–881.

-

86.

King, B., & Thatcher, A. (2014). Attitudes Towards Software Piracy in South Africa: Knowledge of Intellectual Property Laws as a Moderator. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33(3), 209–223.

-

87.

Kirkwood-Mazik, H. (2014). An Inquiry Into the Antecedents of Consumer Purchase of Non-Deceptive Counterfeit Goods: Theory, Practice and Problems. Unpublished Thesis, Cleveland State University,

-

88.

Koklic, M. K. (2011). Non-Deceptive Counterfeiting Purchase Behavior: Antecedents of Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. Journal of Applied Business Research, 27(2), 127–138.

-

89.

Koklic, M. K., Bajde, D., Culiberg, B., & Vida, I. (2012a). The Role of Subjective Knowledge and Perceived Consequences in Shaping Attitude and Intention Toward Digital Piracy. Economic Research, 25(2), 21–32.

-

90.

Koklic, M. K., Bajde, D., Culiberg, B., & Vida, I. (2012b). The Role of Subjective Knowledge and Perceived Consequences in Shaping Attitude and Intention Toward Digital Piracy. Paper presented at the 2012 European Marketing Academy Conference, Lisbon, Portugal,

-

91.

Koklic, M. K., Kukar-Kinney, M., & Vida, I. (2016). Three-Level Mechanism of Consumer Digital Piracy: Development and Cross-Cultural Validation. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(1), 15–27.

-

92.

Koklic, M. K., Vida, I., Bajde, D., & Culiberg, B. (2014). The Study of Perceived Adverse Effects of Digital Piracy and Involvement: Insights from Adult Computer Users. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33(3), 224–235.

-

93.

Koklic, M. K., & Vida, I. O. (2009). A Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Determinants of Consumer Willingness to Purchase Non-Deceptive Counterfeit Products. Paper presented at the Fourteenth Cross-Cultural Research Conference, Puerto Vallarta,

-

94.

Kwan, S. S. K. (2007). End-User Digital Piracy: Contingency Framework, Affective Determinants and Response Distortion. Unpublished Thesis, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology,

-

95.

Kwong, K. K., Yau, O. H. M., Lee, J. S. Y., Sin, L. Y. M., & Tse, A. C. B. (2003). The Effects of Attitudinal and Demographic Factors on Intention to Buy Pirated CDs: The Case of Chinese Consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 47(3), 223–235.

-

96.

Kwong, K. K., You, W. Y. P., Leung, J. W., & Wang, K. (2009). Attitude Toward Counterfeits and Ethnic Groups: Comparing Chinese and Western Consumers Purchasing Counterfeits. Journal of Euromarketing, 18(3), 157–168.

-

97.

Kwong, T. C. H., & Lee, M. K. O. (2002). Behavioral Intention Model for the Exchange Mode Internet Music Piracy. Paper presented at the 35th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii,

-

98.