Abstract

The effect of authentic leadership and leader competency on employee job performance has received growing attention in the past decades; however, few studies have simultaneously integrated these two leadership perspectives. We have thus developed a mediated moderation model to test the interactive effect of authentic leadership and competency on followers’ job performance through work engagement. Based on a sample of 248 subordinate–supervisor pairs, hierarchical regression analyses reveal that (1) authentic leadership positively relates to followers’ task performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB); (2) leader competency moderates the relationship between authentic leadership and OCB; (3) and followers’ work engagement mediates the main effect of authentic leadership and the interactive effect of authentic leadership and competency on followers’ task performance and OCB. All the three results are consistent with our hypotheses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Economic, geo-political, and technological developments over the past decade have required the leaders of organizations to be transparent and aware of their values, and guide their organizations from a moral/ethical perspective (Clapp-Smith et al. 2009). Therefore, the past decade has witnessed a dramatic increase in scholarly interest in the topic of authentic leadership, which focuses on leaders being guided by sound moral convictions and acting in accordance with deeply held values (Avolio et al. 2009; Gardner et al. 2011). There is growing evidence that authentic leadership has a positive effect on new venture performance (Hmieleski et al. 2012) and employees’ outcomes, including followers’ job performance (Leroy et al. 2012; Wong and Cummings 2009), voice behavior (Hsiung 2012), job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Giallonardo et al. 2010; Avolio et al. 2004; Jensen and Luthans 2006; Peus et al. 2012), work engagement (Hassan and Ahmed 2011; Hsieh and Wang 2015), turnover intention (Azanza et al. 2015), and trust in leadership (Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Wong and Cummings 2009; Wong et al. 2010).

However, few studies have considered the extent to which contextual and individual difference variables moderate authentic leader–follower relationships. According to George and Sims (2007), authentic leaders are genuine people who are true to themselves and to what they believe in. They do not try to coerce or even rationally persuade associates, but rather the leader’s authentic values, beliefs, and behavior serve to model the development of associates (Luthans and Avolio 2003). Such a definition implies that authentic leadership does not directly produce high-level management capability; instead, the effectiveness of authentic leaders relies on boundary conditions such as leader competency. For example, researchers have suggested that the effectiveness of supportive leader behavior depends on the level of leader competence (House and Baetz 1979; Podsakoff et al. 1983). Following this research stream, our paper focuses on leaders’ competency, which has been neglected in the existing literature on authentic leadership, and examines whether supervisors’ competency enhances or attenuates the relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ performance.

In addition, recent research has indicated that the effect of authentic leadership on followers’ performance can be transmitted by the leader’s behavioral integrity and predictability (Leroy et al. 2012; Peus et al. 2012), and followers’ affect and trust in leadership (Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Hassan and Ahmed 2011; Hmieleski et al. 2012; Hsieh and Wang 2015; Leroy et al. 2012; Wong et al. 2010). Despite these encouraging findings, relatively little attention has been devoted to followers’ work engagement. Work engagement is a state of mind characterized by vigorous attention and dedication to work and a high level of enthusiasm while at work (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004), which represents the simultaneous work-focused investment of cognitive, affective, and physical energies into job performance (Kahn 1990; Rich et al. 2010). Based on self-enhancement theory (Sedikides and Strube 1997), we propose that work engagement can explain the effectiveness of authentic leadership and the interactive effect of authentic leadership and competency on followers’ job performance.

We structure this paper as follows. First, from the self-enhancement perspective, we clarify how authentic leadership influences followers’ work engagement, which in turn has a positive effect on job performance. We then discuss why competent authentic leaders are perceived as having a stronger influence on the relationship between authentic leadership and job performance and suggest followers’ work engagement as a potential mediator in this interactive relationship. Finally, we present our methodology and results, and discuss the theoretical and practical implications and limitations.

Theory and Hypotheses

Authentic Leadership, Job Performance, and Self-Enhancement Theory

Authentic leaders are “persons who have achieved high levels of authenticity in that they know who they are, what they believe and value, and they act upon those values and beliefs while transparently interacting with others” (Avolio et al. 2004, p. 802). According to Ilies et al. (2005), authentic leaders display four types of behavior: self-awareness, balanced processing, internalized moral perspective, and relational transparency. Self-awareness refers to understanding one’s strengths and weaknesses and the multifaceted nature of the self. Balanced processing refers to objectively analyzing all relevant information before coming up with a ‘fair’ decision. Internalized moral perspective, or authentic behavior, refers to self-regulation guided by internal moral standards and values, as opposed to behavior based on external societal pressures. Relational transparency refers to an active process of self-disclosure, including showing one’s authentic self, true thoughts, and feelings to followers and developing mutual intimacy and trust. Authentic leadership can motivate followers to engage in self-enhancement.

The self-enhancement motivation has been regarded as a fundamental drive that influences individual cognition and behavior across cultures (Jordan and Audia 2012; Kruglanski 1980; Liu et al. 2013). The self-enhancement theory assumes that “people are motivated by the desire to elevate the positivity of their self-conceptions and to protect their self-concepts from negative information” (Sedikides and Strube 1997, p. 212). Self-enhancement behavior can occur either by devoting more time and effort to enhance the positivity of one’s self-views, or by avoiding threatening situations to reduce the negativity of one’s self-views (Arkin 1981). Korman (2001) has suggested that self-enhancement motivation is most likely to be elicited by providing career development opportunities and encouraging followers to attain their goals.

Given that authentic leaders foster the positive emotional and cognitive development of their followers (Avolio and Gardner 2005), employees’ self-worth perceptions and self-esteem will be enhanced as they acquire a more positive evaluation of self (Dutton et al. 1994). In addition, perceptions of authentic leadership signal to followers that they are special and worthy of employers’ special treatment and trust, which promotes their positive sense of self; followers then seek to maintain this positive self-image by increased effort and goal-directed behavior (Chen et al. 2013). In contrast, employees’ self-enhancement motive is accentuated by perceptions of threat to their self-view (Baumeister et al. 1996; Gramzow 2011). Thus, when leaders treat their followers unauthentically, self-enhancing followers may retrospectively reduce the level of their effort to align more closely with the existing interpersonal relationship. Moreover, some empirical supports have recently emerged (Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Hmieleski et al. 2012; Leroy et al. 2012, 2015; Wong and Cummings 2009). For example, Clapp-Smith et al. (2009) report that authentic leadership is positively related to work performance as measured by sales growth. Leroy et al. (2012, 2015) find that authentic leadership is positively related to followers’ affective organizational commitment and work role performance. Wang et al. (2014) also find that authentic leadership is positively related to followers’ task performance. Wong and Cummings (2009) suggest that authentic leadership improves followers’ self-rated job performance. Based on the arguments above, it can be assumed that authentic leadership can positively influence followers’ job performance. Furthermore, as Hsieh and Wang (2015)’s cross-level study has shown, authentic leadership is positively related to employee trust and work engagement.

Authentic Leadership and Work Engagement

Work engagement is a positive, affective–motivational state of fulfillment that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al. 2002). Vigor is the willingness to persistently put effort into one’s work. Dedication refers to a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and challenge from work. Absorption captures the characteristics of attention and complete engagement in the work. Engaged individuals are generally described as being willing to invest their effort and sense of self in their job (Kahn 1990; Salanova and Schaufeli 2008).

Authentic leaders enhance followers’ work engagement for the following reasons. First, given that autonomy and opportunities for development have been considered fundamental for engagement (Markos and Sridevi 2010), authentic leaders provide incentives that encourage followers to invest themselves into their work. These incentives may appear in the form of something they value, such as stimulating positive personal growth or being given the opportunity to become leaders (Luthans and Avolio 2003). For example, in an interactive process, authentic leaders emphasize norms of openness and honesty not only by demonstrating such qualities themselves, but also by displaying expectations that followers do the same (May et al. 2003). By leading from the front, openly discussing their vulnerabilities and followers’ vulnerabilities, and constantly emphasizing the growth of followers, authentic leaders develop their followers (Avolio et al. 2004). Similarly, Chen et al. (2013) suggest that workplace interactions characterized by dignity and respect and supportive communication promote a sense of engagement from employees. As a result, followers are motivated by an authentic leader to exhibit positive behavior, engagement, and a willingness to reciprocate (e.g., Ilies et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2014; Yukl 2002).

Second, authentic leaders may free followers from unnecessary psychological concerns, protecting their self-views from harm. Authentic leaders stress openness, honesty, and respect by striving for these qualities in interactions with their followers, and openly discussing their own vulnerabilities and transparently sharing their perceptions and feelings about their colleagues (Avolio et al. 2004; Luthans and Avolio 2003; May et al. 2003). Because they have the courage to show their humanness and express their true emotions and limitations to followers, rather than maintaining a “perfect leader” image, an authentic leader can help followers build openness, free them from the burden of concealing their own limitations, and engage them in genuine self-expression (Owens and Hekman 2012; Yagil and Medler-Liraz 2014). Hence, mutual trust and respect can be easily developed between authentic leaders and their followers in transparent interaction.

Furthermore, Kahn (1990) argues that when individuals experience psychological meaningfulness and safety in specific situations, they are more engaged in their work. Moreover, Robinson (2006) suggests that employee engagement can be achieved through the creation of a supportive organizational environment. Because authentic leaders shape a climate of mutual trust and foster positive expectations, self-image, and status among followers, such followers will be more engaged in their work (Algera and Lips-Wiersma 2012; Yagil and Medler-Liraz 2014). Empirically, a positive relationship between authentic leadership and work engagement has also been found in previous research (e.g., Hassan and Ahmed 2011; Hsieh and Wang 2015; Penger and Černe 2014). Therefore, authentic leadership is positively related to followers’ work engagement.

Work Engagement and Job Performance

It is assumed that individuals who have invested their sense of self in a role will enhance their sense of self through improving their job performance (Chen et al. 2013; Ferris et al. 2010). In this study, we suggest that engaged employees might not only work harder to maintain high levels of task performance, but also engage in organizational citizenship behavior.

Task performance is regarded as a reflection of an employee’s talents, capability, and competence (Yun et al. 2007). Yun et al. (2007) suggest that employees who achieve higher levels of performance are likely to be viewed more favorably by others, which would satisfy their positive self-views. In contrast, poor performance is likely to threaten employees’ positive self-views. Therefore, engaged employees will seek to improve their task performance given the close linkage with their sense of self (Chen et al. 2013).

Organizational citizenship behavior is defined as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Organ 1988, p. 4). Because organizational citizenship behavior (OCBs) exceed individuals’ formal job requirements, those who engage in more OCBs are more valued and viewed more favorably by others. Individuals will acquire a more positive self-evaluation, given that OCBs provide them with opportunities to show their friendship, talents, and knowledge (Stevens 1997). As a result, engaged employees will seek to engage in more OCBs. Indeed, this reasoning is consistent with empirical research showing positive relationships between job engagement, task performance, and organizational citizenship behavior (Christian et al. 2011; Sulea et al. 2012; Rich et al. 2010; Salanova and Schaufeli 2008).

Based upon the above discussion, we suggest that authentic leaders will elicit higher levels of work engagement from followers, which in turn improves job performance. Thus, we propose and test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

The effect of authentic leadership on follower task performance is mediated by follower work engagement.

Hypothesis 2

The effect of authentic leadership on follower organizational citizenship behavior is mediated by follower work engagement.

The Moderating Role of Leader Competency

It is generally believed that authentic leadership emphasizes improving performance by indirectly fostering positive emotions and attitudes among followers, rather than by directly relying on their own direction and competency (Gardner et al. 2011). The essence of authenticity is to know, accept, and remain true to one’s self (Avolio et al. 2004; May et al. 2003), which means that they are willing to present their genuine self, and objectively evaluate and accept their own positive and negative attributes, including skill deficiencies, suboptimal performance, and negative emotions. However, this does not mean that authentic leaders are competent to make decision, establish work procedures, increase functional specialization, organize around the strategy, et al.

Competency is defined as a combination of tacit and explicit knowledge, behavior, skills, and abilities, which gives someone the potential for effectiveness in task performance (Draganidis and Mentzas 2006). Examples of leaders’ competency include problem awareness, strategic planning, decision making, goal setting, coordinating with subordinates, and monitoring them as they carry out a plan. Although leader competence is an important factor in improving followers’ job performance (Kim et al. 2009; Levenson et al. 2006; O’Boyle et al. 2011), many leadership scholars suggest that highest performance can be reached only when the leaders are both task- and relationship-motivated (e.g., Hooijberg and Choi 1999; Yukl and Lepsinger 2005).

There is evidence that employees are influenced more by ideas expressed by experts than non-experts (Bass 1960; Mausner 1953, 1954; Evan and Zelditch 1961). For example, Podsakoff et al. (1983) suggest that we generally place more value on and are more satisfied with supportive behavior provided by an expert than by a non-expert. Justis et al. (1978) also suggest that if an employee perceives his/her leader to be relatively competent, he/she will be more motivated and willing to accept influence from the leader than if the leader is perceived as incompetent. At the same time, the study assumes that subordinates learn to follow the relevant behavior of a competent leader more rapidly than the behavior of a less competent leader.

These arguments are all concerned with the moderating effect of the leadership situation on the effect of leader attributes on followers’ performance. Therefore, when subordinates regard their authentic leader as competent, they place more value on and are more willing to accept the leader’s influence. So, the positive influence of authentic leadership on subordinates’ performance will be enhanced. However, if the authentic leader is seen as less competent, they will be more reluctant to accept their leader’s positive influence.

Based on the above reasoning, we therefore make the following prediction:

Hypothesis 3

Leader competency moderates the relationship between authentic leadership and follower task performance and organizational citizenship behavior, such that authentic leadership will have a stronger positive effect on follower performance when leaders are competent than incompetent.

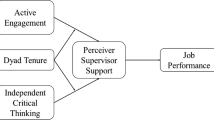

Combining Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, we further propose a mediated moderation model (see Fig. 1), such that authentic leadership and leader competency interactively influence followers’ work engagement, which in turn relates positively to followers’ task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4

The interactive effects of authentic leadership and leader competency on follower task performance and organizational citizenship behavior are mediated by follower work engagement.

Method

Sample and Procedure

A total of 320 followers and their immediate leaders from a large Chinese company in Shanghai were invited to participate in our survey. The company’s human resources managers gave us a list of potential participants’ names and positions, and we randomly selected 320 subordinates and their 320 supervisors. A cover letter attached to each questionnaire explained the objectives and procedures of the survey, and anonymity and confidentiality were assured. Subordinates were asked to complete a survey on their supervisors’ competency and authentic leadership and their own work engagement; supervisors were asked to complete a survey on followers’ task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. A total of 248 valid supervisor–subordinate dyads were returned with complete data (77.5% response rate).

Fifty-three percent of the employees were male. Ninety percent have college, bachelor’s, or master’s degrees. The average age was 28.4 years (SD = 5.9), and the average job tenure was 37.8 months (SD = 38.3). For the supervisors, 72% were male, 89% have college, bachelor’s, or master’s degrees, the average age was 33.2 years (SD = 5.3), and the average job tenure was 72.8 months (SD = 47.8).

Measures

The original questionnaire was written in English and translated into Chinese by academic scholars bilingual in Mandarin and English. We used the conventional method of back-translation (Brislin 1980) several times until the English and Mandarin versions were highly similar.

Authentic Leadership

We measured engagement with a 16-item authentic leadership scale developed by Walumbwa et al. (2008). Followers were asked to rate their leader on a five-point Likert scale ranging from never to almost always. Sample items include “he/she is eager to receive feedback to improve interactions with others” (self-awareness), “he/she makes decisions based on his/her core beliefs” (internalized moral perspective), “he/she is willing to admit mistakes when they are made” (relational transparency), and “he/she solicits views that challenge his or her deeply held positions” (balanced processing). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Leader Competency

We measured leader competency with the 13-item measure of managerial competency developed by Tett et al. (2000). On a six-point Likert scale, the followers were asked to assess their supervisor’s competencies on problem awareness, decision making, directing, decision delegation, short-term planning, strategic planning, goal setting, monitoring, motivating others with authority or persuasion, and team building. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Work Engagement

We measured engagement on a six-point Likert scale, using the nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale developed by Schaufeli and Bakker (2004). The scale reflects three types of energy (vigor, absorption, and dedication) that people may invest in their roles. Sample items include “At my work, I feel bursting with energy” (vigor); “I am enthusiastic about my job” (dedication), and “I am immersed in my work” (absorption). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Job Performance

We asked the supervisors to evaluate their subordinates’ task performance with the four-item scale developed by Williams and Anderson (1991). On a six-point Likert scale, supervisors indicated the extent to which they agreed with statements such as “… adequately completes his/her assigned duties” and “…fulfills responsibilities specified in his/her job descriptions.” Subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior was measured with three items developed by Chen et al. (1998). Sample items include “This employee helps orient new employees even though it is not required.” Cronbach’s alphas for task performance and OCB were 0.74 and 0.81, respectively.

Control Variables

We controlled for five demographic variables of employees (age, gender, education level, organization tenure, and dyadic tenure), because previous research has found that they are significantly related to job performance and/or work engagement (e.g., Breevaart et al. 2015; Sosik et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2014).

Results

Measurement Model

Although we measured data from both employees and their supervisors, our results might be affected by common method variance, because all variables were rated by the respondents in the same period of time. Therefore, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis using LISREL 8.7 to assess whether these five variables can be differentiated from each other. Results of the model fit show that the five-factor model provides a better fit (χ2 (935) = 1723.23, RMSEA = 0.06, RMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.97, NFI = 0.93) than all possible alternative models, for example, the four-factor model combining task performance and OCB (χ 2 (939) = 1884.05, RMSEA = 0.06, RMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.93), the three-factor model combining task performance and OCB into one factor and competency and authentic leadership into another (χ 2 (935) = 4851.96, RMSEA = 0.13, RMR = 0.09, CFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.89), and the single-factor model (χ 2 (945) = 7762.46, RMSEA = 0.17, RMR = 0.14, CFI = 0.87, NFI = 0.83). In addition, following Podsakoff et al. (2003), we also use the Harman’s single-factor technique (Harman 1960) to check the common method variance. The exploratory factor analysis results show that there is no general factor in the unrotated factor structure, with the first factor accounting for only 31% of the total variance.

Descriptive Statistics

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among all the study variables are presented in Table 1. Each study variable has an acceptable degree of internal consistency reliability. As expected, authentic leadership and competency were significantly and positively related to followers’ work engagement, which in turn was positively and significantly related to followers’ task performance and OCB.

Hypothesis Testing

We use regression-based mediation analysis (Baron and Kenny 1986) to test Hypotheses 1 and 2. Table 2 shows the results. Model 4 shows that work engagement relates positively to task performance (β = 0.34, p < 0.01) and OCB (β = 0.43, p < 0.01), and when it enters into the equation, the positive relationships between authentic leadership and task performance (from β = 0.19, p < 0.01 to β = 0.12, n.s.) and OCB (from β = 0.13, p < 0.05 to β = 0.04, n.s.) are reduced significantly. These results indicate that work engagement fully mediates the authentic leadership–job performance relationship. Thus, Hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported.

To test Hypothesis 3, we conduct multiple hierarchical regression analyses. Model 1 in Table 2 shows that authentic leadership significantly predicts followers’ task performance (β = 0.30, p < 0.01) and OCB (β = 0.21, p < 0.01). Model 3 shows that leader competency moderates the link between authentic leadership and OCB (β = 0.18, p < 0.01) but does not moderate the relationship between authentic leadership and task performance (β = 0.08, n.s.), partially supporting H3.

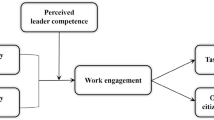

To interpret the demonstrated moderating effects, we solve for regression equations at low and high leader competency (defined as the mean minus and plus one standard deviation). It was inferred from Fig. 2 that the pattern of interactions is as predicted in Hypothesis 3: the positive association between authentic leadership and OCB is stronger when leader competency is higher.

Hypothesis 4 suggests that work engagement mediates the interactive effect of authentic leadership and leader competency on job performance. Model 4 in Table 2 shows that the interaction term of authentic leadership and leader competency and task performance (from β = 0.08, p < 0.10 to β = 0.04, n.s.) and OCB (from β = 0.18, p < 0.01 to β = 0.13, p < 0.05) are reduced significantly when work engagement enters into the equation, offering support for Hypothesis 4.

Because the bootstrapped confidence interval approach generates a more accurate estimation of the indirect relationship than traditional methods (Gong et al. 2013; MacKinnon et al. 2004), we perform a bootstrap analysis to further test Hypothesis 4 (Preacher et al. 2007). We examine the conditional indirect effects of authentic leadership on followers’ job performance through work engagement for three values of leader competency (one standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and one standard deviation below the mean). As shown in Table 3, at mean level and one standard deviation above the mean of leader competency, bootstrapping reveals that 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for task performance (0.01 → 0.12; 0.03 → 0.16) and OCB (0.02 → 0.15; 0.04 → 0.21) do not contain zero, so the indirect effect of authentic leadership on job performance is statistically significant. The indirect effect is not significant at one standard deviation below the mean, because the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for task performance (−0.02 → 0.08) and OCB (−0.03 → 0.11) contain zero. Therefore, when leader competency is low, work engagement does not mediate the effects of authentic leadership on subordinate job performance. At average or high levels of leader competency, work engagement does mediate the effects of authentic leadership on job performance. Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Discussion

The performance literature has long noted the importance of authentic leadership and competencies (e.g., Goldstein et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2009; Leroy et al. 2012; Levenson et al. 2006; O’Boyle et al. 2011; Wong and Cummings 2009). However, few studies have examined the joint effect of the two leadership characteristics and the work-focused mechanism on followers’ job performance. This study develops a mediated moderation model in which a leader’s authenticity and competencies have an interactive effect on the follower’s performance through the mediation of work engagement. The results suggest that authentic leadership has a positive effect on followers’ performance, which are consistent with the results from previous studies (e.g., Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Hmieleski et al. 2012; Leroy et al. 2012, 2015; Wang et al. 2014; Wong and Cummings 2009), and that the effect is stronger when leaders are more competent. In addition, the main and interactive effects are mediated by the follower’s work engagement.

Theoretical Implications

The current study provides several theoretical implications for researchers. First, our results contribute to both the authentic leadership and the competency literature by showing that the effect of authentic leadership on employee job performance can vary as a function of the leader’s competencies. Although the effect of authentic leadership on employee job performance has received increasing attention in organizational behavior research (e.g., Leroy et al. 2012; Walumbwa et al. 2008; Wong and Cummings 2009), the literature is also replete with scholars who warn that the effectiveness of supportive leader behavior depends on the level of the leader’s competence (House and Baetz 1979; Podsakoff et al. 1983). Therefore, it is important to understand when authentic leadership is more or less likely to lead to performance improvement. Our findings extend current studies (e.g., Leroy et al. 2012; Levenson et al. 2006) from an interactional approach by providing a more accurate realization of the relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ performance. We hope that our study will also encourage leadership researchers to pay more attention to the boundary conditions of leader competency in future leadership studies.

Second, our results provide support for our prediction that work engagement mediates the effect of authentic leadership on followers’ performance, particularly for highly competent leaders. Although studies of the process and mechanisms by which authentic leadership influences followers’ performance have examined the leader’s behavioral integrity and predictability (e.g., Leroy et al. 2012; Peus et al. 2012) and the follower’s affect and trust in the leader (e.g., Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Hassan and Ahmed 2011; Hmieleski et al. 2012; Hsieh and Wang 2015; Leroy et al. 2012; Wong et al. 2010), little attention has been paid to the follower’s comprehensive work-focused characteristics including cognitive, affective, and physical aspects, and none to the mediated moderation effect. In focusing on both moderating and mediating effects together, our model helps explain both how authentic leadership influences followers’ performance, and for whom authentic leadership has the greatest effect on job performance. In so doing, our study provides evidence that authentic leadership can have a positive effect on followers’ performance through work engagement, and also extends our understanding of how such a relationship works.

Furthermore, because work engagement represents the simultaneous investment of one’s cognitive, affective, and physical energies in work (Kahn 1990; Rich et al. 2010), we argue that the mediating role of work engagement provides a more work-focused, comprehensive explanation of mediation from a self-enhancement perspective than other mechanisms that only take account of the leader’s perspective (e.g., Leroy et al. 2012; Peus et al. 2012) or the cognitive or affective aspects of the self (e.g., Hmieleski et al. 2012; Hsieh and Wang 2015; Leroy et al. 2012; Peus et al. 2012).

Practical Implications

Our study also offers some practical implications. First, our results suggest that leaders’ authenticity may play an important role in improving followers’ job performance, and these performance improvements are in the form of both task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. However, although the relevance of authentic leadership to job performance may be important, what may be more noteworthy is the moderating effect of leader competencies. This pattern of findings suggests that authentic leadership should be especially encouraged when the leader is competent.

Secondly, our results also suggest that work engagement may play an important role in the influence of authentic leaders on their followers’ performance. The finding that engagement directly affects followers’ work performance shows that it is possible to increase work engagement by other means than authentic leadership, and in the process improve followers’ job performance. For example, previous research has found that work engagement may be increased by job resources (i.e., job control, feedback, and variety), perceived value congruence, organizational support, and core self-evaluations (e.g., Rich et al. 2010; Salanova and Schaufeli 2008).

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, the generalizability of our findings is unknown. Our participants were the employees in a large company in Shanghai, so the generalizability of our findings needs to be assessed and reconfirmed in other organizational backgrounds, city environments, and national cultures. Second, because our research was cross-sectional, we are unable to draw strong causal inferences regarding the variables’ relationships. Although we had strong theoretical and logical reasons for causality, alternative causal models may be plausible. Therefore, longitudinal research designs are needed in future research. Third, although we obtained predictor and criterion variable data from different sources in this study, and we asked respondents to indicate their opinions on a six-point Likert scale to avoid the use of bipolar numerical scale values in most of the items (e.g., Tourangeau et al. 2000; Podsakoff et al. 2003); there was still a risk of common method bias, because the data collection procedure is cross-sectional in nature and the antecedent and mediating variables were rated by the same-source followers. However, we believe that common method biases should not be a main problem in the current study, because both confirmatory factor analysis and a single-factor technique test found no serious threat to our results. Future research should use longitudinal research designs and multiple raters to access different variables.

References

Algera, P., & Lips-Wiersma, M. (2012). Radical authentic leadership: Co-creating the conditions under which all members of the organization can be authentic. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 118–131.

Arkin, R. M. (1981). Self-presentation styles. In J. Tedeschi (Ed.), Impression management theory and research (pp. 311–333). New York: Academic Press.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338.

Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 801–823.

Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 421–449.

Azanza, G., Mariano, J. A., Molero, F., & Mangin, J.-P. L. (2015). The effects of authentic leadership on turnover intention. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 36(8), 955–971.

Bass, B. M. (1960). Leadership, psychology and organizational behavior. New York: Harper.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review, 103, 5–33.

Breevaart, K., Bakker, A., Demerouti, E., & van den Heuvel, M. (2015). Leader-member exchange, work engagement, and job performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(7), 754–770.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Chen, X.-P., Hui, C., & Sego, D. J. (1998). The role of organizational citizenship behavior in turnover: Conceptualization and preliminary tests of key hypotheses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(6), 922–931.

Chen, Y., Ferris, D. L., Kwan, H. K., Yan, M., Zhou, M., & Hong, Y. (2013). Self-love’s lost labor: A self-enhancement model of workplace incivility. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 1199–1219.

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136.

Clapp-Smith, R., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Avey, J. B. (2009). Authentic leadership and positive psychological capital: The mediating role of trust at the group level of analysis. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 15(3), 227–240.

Draganidis, F., & Mentzas, G. (2006). Competency based management: A review of systems and approaches. Information Management & Computer Security, 14(1), 51–64.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 57–88.

Evan, W., & Zelditch, M. (1961). A laboratory experiment on bureaucratic authority. American Sociological Review, 26, 883–893.

Ferris, D. L., Lian, H., Brown, D. J., Pang, F. X. J., & Keeping, L. M. (2010). Self-esteem and job performance: The moderating role of self-esteem contingencies. Personnel Psychology, 63, 561–593.

Gardner, W. L., Cogliser, C. C., Davis, K. M., & Dickens, M. P. (2011). Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1120–1145.

George, W., & Sims, P. (2007). True north: Discover your authentic leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Giallonardo, L. M., Wong, C. A., & Iwasiw, C. L. (2010). Authentic leadership of preceptors: Predictor of new graduate nurses’ work engagement and job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(8), 993–1003.

Goldstein, H. W., Yusko, K. P., & Nicolopoulos, V. (2001). Exploring black–white subgroup differences of managerial competencies. Personnel Psychology, 54(4), 783–807.

Gong, Y., Kim, T. Y., Zhu, J., & Lee, D. R. (2013). A multilevel model of team goal orientation, information exchange, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 56, 827–851.

Gramzow, R. H. (2011). Academic exaggeration: Pushing self-enhancement boundaries. In M. D. Alicke & C. Sedikides (Eds.), Handbook of self-enhancement and self-protection (pp. 455–471). New York: Guilford.

Harman, H. H. (1960). Modern factor analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hassan, A., & Ahmed, F. (2011). Authentic leadership, trust and work engagement. International Scholarly and Scientific Research & Innovation, 5(8), 1036–1042.

Hmieleski, K. M., Cole, M. S., & Baron, R. A. (2012). Shared authentic leadership and new venture performance. Journal of Management, 38, 1476–1499.

Hooijberg, R., & Choi, J. (1999). From Austria to the United States and from evaluating therapists to developing cognitive resources theory: An interview with Fred Fiedler. The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 653–665.

House, R. J., & Baetz, J. L. (1979). Leadership: Some empirical generalizations and new research directions. Research in Organizational Behavior, 1, 341–423.

Hsieh, C., & Wang, D. (2015). Does supervisor-perceived authentic leadership influence employee work engagement through employee-perceived authentic leadership and employee trust? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(18), 1–20.

Hsiung, H.-H. (2012). Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: A multi-level psychological process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 349–361.

Ilies, R., Morgeson, F. P., & Nahrgang, J. D. (2005). Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader–follower outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 373–394.

Jensen, S. M., & Luthans, F. (2006). Entrepreneurs as authentic leaders: Impact on employees’ attitudes. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 27(8), 646–666.

Jordan, A. H., & Audia, P. G. (2012). Self-enhancement and learning from performance feedback. Academy of Management Review, 37, 211–231.

Justis, R. T., Kedia, B. L., & Stephens, D. B. (1978). The effect of position power and perceived task competence on trainer effectiveness: A partial utilization of Fiedler’s contingency model of leadership. Personnel Psychology, 31(1), 83–93.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

Kim, T.-Y., Cable, D., Kim, S., & Wang, J. (2009). Emotional competence and work performance: The mediating effect of proactivity and the moderating effect of job autonomy. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 90, 983–1000.

Korman, A. K. (2001). Self-enhancement and self-protection: Toward a theory of work motivation. In M. Erez, U. Kleinbeck, & H. Thierry (Eds.), Work motivation in the context of a globalizing economy (pp. 121–130). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1980). Lay epistemologic process and contents: Another look at attribution theory. Psychological Reviews, 87, 70–87.

Leroy, H., Anseel, F., Gardner, W. L., & Sels, L. (2015). Authentic leadership, authentic followership, basic need satisfaction, and work role performance: A cross-level study. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1677–1697.

Leroy, H., Palanski, M. E., & Simons, T. (2012). Authentic leadership and behavioral integrity as drivers of follower commitment and performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 255–264.

Levenson, A. R., Van der Stede, W. A., & Cohen, S. G. (2006). Measuring the relationship between managerial competencies and performance. Journal of Management, 32(3), 360–380.

Liu, J., Lee, C., Hui, C., Kwan, H. K., & Wu, L. Z. (2013). Idiosyncratic deals and organizational contribution: The mediating roles of social exchange and self-enhancement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 832–840.

Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Authentic leadership development. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 241–261). San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

Markos, S., & Sridevi, M. S. (2010). Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(12), 89–97.

Mausner, B. (1953). Studies in social interaction: Effect of variation in one partner’s prestige on the interaction of observer pairs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 37(5), 391–393.

Mausner, B. (1954). The effect of one partner’s success in a relevant task on the interaction of observer pairs. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49(4), 557–560.

May, D. R., Chan, A., Hodges, T., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Developing the moral component of authentic leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 32(3), 247–260.

O’Boyle, E. H., Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., Hawver, T. H., & Story, P. A. (2011). The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 788–818.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Owens, B., & Hekman, D. R. (2012). Modeling how to grow: An inductive examination of humble leader behaviors, outcomes, and contingencies. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 787–818.

Penger, S., & Černe, M. (2014). Authentic leadership, employees’ job satisfaction, and work engagement: A hierarchical linear modelling approach. Economic Research, 27(1), 508–526.

Peus, C., Wesche, J. S., Streicher, B., Braun, S., & Frey, D. (2012). Authentic leadership: An empirical test of its antecedents, consequences, and mediating mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 331–348.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., Todor, W. D., & Schuler, R. (1983). Leader expertise as a moderator of the effects of instrumental and supportive leader behaviors. Journal of Management, 9, 173–185.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Rich, B. L., LePine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635.

Robinson, I. (2006). Human resource management in organisations. London: CIPD.

Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). Job resources, engagement and proactive behaviour. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(1), 116–131.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., Gonzalez-Roma, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout and: A confirmative analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92.

Sedikides, C., & Strube, M. J. (1997). Self-evaluation: To thine ownself be good, to thine own self be sure, to thine own self be true, and to thine own self be better. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 209–269.

Sosik, J. J., Juzbasich, J., & Chun, J. (2011). Effects of moral reasoning and management level on ratings of charismatic leadership, in-role and extra-role performance of managers: A multi-source examination. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 434–450.

Stevens, C. K. (1997). Effects of preinterview beliefs on applicants’ reactions to campus interviews. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 947–966.

Sulea, C., Virga, D., Maricutoiu, L. P., Schaufeli, W., Dumitru, C. Z., & Sava, F. A. (2012). Work engagement as mediator between job characteristics and positive and negative extra-role behaviors. Career Development International, 17(3), 1–32.

Tett, R. P., Guterman, H. A., Bleier, A., & Murphy, P. J. (2000). Development and content validation of a hyper dimensional taxonomy of managerial competence. Human Performance, 13(3), 205–251.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89–126.

Wang, H., Sui, Y., Luthans, F., Wang, D., & Wu, Y. (2014). Impact of authentic leadership on performance: Role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 5–21.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617.

Wong, C. A., & Cummings, G. G. (2009). The influence of authentic leadership behaviors on trust and work outcomes of health care staff. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(2), 6–23.

Wong, C. A., Spence Laschinger, H. K., & Cummings, G. G. (2010). Authentic leadership and nurses’ voice behaviour and perceptions of care quality. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(8), 889–900.

Yagil, D., & Medler-Liraz, H. (2014). Service employees’ trait authenticity and customer satisfaction. In W. J. Zerbe, N. M. Ashkanasy, & C. E. J. Härtel (Eds.), Individual sources, dynamics, and expressions of emotion (pp. 169–185). Bingley: Emerald Group.

Yukl, G., & Lepsinger, R. (2005). Why integrating the leading and managing roles is essential for organizational effectiveness. Organizational Dynamics, 34(4), 361–375.

Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in organizations (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Yun, S., Takeuchi, R., & Liu, W. (2007). Employee self-enhancement motives and job performance behaviors: Investigating the moderating effects of employee role ambiguity and managerial perceptions of employee commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 745–756.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 1509093); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71102028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, F., Li, Y., Zhang, Y. et al. The Interactive Effect of Authentic Leadership and Leader Competency on Followers’ Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. J Bus Ethics 153, 763–773 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3379-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3379-0