Abstract

This study empirically examines the proposition that ethical leadership may affect individuals’ task performance through enhancing employees’ promotive voice. Our theoretical model was tested using data collected from employees and supervisors in a high-tech company located in South China. Analyses of multisource three-wave data from 37 team supervisors and 176 employees showed that ethical leadership could significantly affect individuals’ task performance through promotive voice. Further, it was found that the relationship between ethical leadership and promotive voice was moderated by leader–leader exchange. Specifically, ethical leadership may significantly enhance employees’ promotive voice when leader–leader exchange is low. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ethical leadership has emerged as an important topic for understanding the effects of leadership within organizations (Chen and Hou 2015). Ethical leaders may successfully impose ethical behavior on employees’ behavior and performance by “demonstrating normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and promoting such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005). However, relatively few studies have examined how and why ethical leadership relates to an individual’s task performance (Zhu et al. 2015). With a sample of 312 supervisor–subordinate dyads, (Liu et al. 2013) found that ethical leadership may positively enhance employees’ task performance through reciprocity. When employees are treated in an ethical manner, they are inclined to view the relationships with their supervisors in terms of social exchange. A relatively common theme observed in previous studies is that employees’ task performance improves when they experience a high quality of social exchange with their immediate ethical supervisors (Gu et al. 2015; Masterson et al. 2000). However, relationship building (LMX) in the supervisor–employee dyad is not the only way an employee can reciprocate for an ethical supervisor’s good will (e.g., Detert and Burris 2007). A supervisor is in a certain sense the team’s representative (Blanc and Gonzalez-Roma 2012). His/her actions are usually perceived as being driven by the team’s decisions (Eisenberger et al. 2002). Thus, employees under the supervision of ethical leaders may not just respond to their supervisors; they may also reciprocate by providing the focal team with constructive ideas and suggestions about team-related issues to improve the team’s existing practices and procedures, rather than maintaining an ineffective or inefficient status quo (e.g., Liang et al. 2012; Maynes and Podsakoff 2014; Van Dyne and LePine 1998; Zhu et al. 2015).

This study focuses on promotive voice targeted at the team, highlighting opportunities for better work practices and improved performance (Liang et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2015). As opposed to prohibitive voice, (which primarily calls attention to factors that have harmed the status quo by reporting incidents and stopping harmful behavior), promotive voice places a stronger ethical emphasis on visualizing future ideal situations and proposing solutions that guide the individuals and the entire team toward such possibilities. In this way, promotive voice may also lead to personal benefits such as improving individual performance (Liang et al. 2012). Hence, the first goal of this study is to examine promotive voice as an important social exchange-based mechanism between employees and the focal team that their supervisor represents, which helps facilitate the effect of ethical leadership on employees’ task performance.

Despite the fact that the dyadic exchange relationship between employees and supervisors exists within an organization’s broader network of exchange relationships, few studies have paid attention to the effect of the exchange relationship between supervisors and their upward leaders (leader–leader exchange, LLX) (Tangirala et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2012). Recent leadership research has suggested that LLX essentially reflects the mutual trust and commonality of goals between a supervisor and his/her upward leader (Zhou et al. 2012). A supervisor with a higher LLX may obtain important organizational resources such as extra time, money, and support. In this situation, employees are more likely to have access to those resources to achieve their collective objectives. In contrast, employees are expected to receive limited organizational resources and support when their supervisors maintain lower LLX (Eisenberger et al. 2002). The affect theory of social exchange posits that different types of exchanges affect the solidarity and identification that an individual feels with his/her exchange partner and group (Lawler 2001). The strongest affective attachments can be produced when both exchange partners strive to contribute so that either one of them can benefit (Berg 1984; Lawler 2001). Accordingly, when a supervisor has comparatively limited organizational resources but still offers care and support sufficient for team employees to achieve their collective goals and objectives, employees in such a team are likely to contribute their constructive ideas and suggestions to the team as a way of accumulating additional resources for the supervisor and for the future of the entire team. In this regard, we try to answer an important question pertaining to the circumstances under which ethical leadership behavior is more likely to be valued and reciprocated by employees. Thus, the second goal of this study is to address this important yet relatively understudied issue by examining the affect of LLX as a boundary condition on the relationship between ethical leadership and employee voice in a cross-level framework.

This study makes several contributions to theory and practice. First, past research on ethical leadership has mainly argued that employees reciprocate for the favors given to them by their ethical supervisors in the process of relationship building (LMX) in employee–supervisor dyads. This study provides an important extension by highlighting promotive voice as an important exchange mechanism targeted at the focal team. Second, this study integrates the affect theory of social exchange with the ethical leadership and voice literature to deepen our understanding of when ethical leadership is the most influential for the enactment of lower level employees’ voice behavior and performance. Finally, this study has implications for how to maximize the effectiveness of ethical leadership for practitioners.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Ethical Leadership, Promotive Voice, and Task Performance

Ethical leaders (e.g., moral person and moral manager) are seen as principled decision makers who care more about the greater good of the employees and the organization (Brown and Trevino 2006a; Brown et al. 2005; Treviño et al. 2003). In line with social exchange theory (Blau 1964), ethical leadership provides an ethical and reciprocal framework, which facilitates favorable conditions in the relationship-building processes with employees (Chan and Mak 2012). Under the supervision of ethical leaders, employees are likely to receive more individualized care and support. Subsequently, they are more likely to reciprocate by developing and expressing attitudes valued by their supervisors (Tangirala et al. 2007). In other words, by proactively taking on the role of being an ethical leader, a supervisor may receive more respect from, and thus have more high-quality exchange relationships (LMX) with, his or her employees. The previous literature, in fact, has primarily concluded that ethical leaders can influence employees’ behavior and performance by building mutual interpersonal relationships (Gu et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2013; Masterson et al. 2000).

Relationship building (LMX), however, is not the only way for employees to requite ethical supervisors. In a certain sense, a supervisor is a team’s representative (Blanc and Gonzalez-Roma 2012). Employees understand that a supervisor’s decisions and actions are often in line with the team’s objectives, further contributing to the employees’ perception that supervisor care and support is associated with team support (Eisenberger et al. 2002). Thus, when employees are treated well and supported by their supervisor, they may reciprocate by providing the entire team with constructive suggestions and ideas about future team development (e.g., Liang et al. 2012; Maynes and Podsakoff 2014; Van Dyne and LePine 1998; Van Dyne et al. 2003). Essentially, promotive voice is a form of employees’ prosocial behavior aimed at improving existing work practices and procedures instead of working within an ineffective or inefficient status quo (Liu et al. 2015; Morrison 2011; Van Dyne and LePine 1998). As a type of exchange-based prosocial action, it also has ethical implications (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009). Thus, we suggest that ethical leadership can enhance employees’ promotive voice for the following two reasons.

First, ethical supervisors usually treat employees with care, respect, and fairness. As the team’s representative, they publicly advocate for the team’s ethical values, develop an ethical climate, and reward employees who take the appropriate courses of action. Within this environment, the employees’ concerns about the potential risks of speaking up are largely minimized (Gao et al. 2011; Hsiung, 2012). They are more likely to identify with the supervisor and the focal team and as a result make proactive suggestions regarding not only team ethics but also innovative methods and procedures that enhance team efficiency.

Second, ethical supervisors tend to provide team employees with virtuous resources, such as collective trust, in addition to psychological and physical support (Chen and Hou 2015; Maynes and Podsakoff 2014; Van Dyne and LePine 1998). With such resources, employees are more able to implement new ideas that are potentially beneficial to the collective. That is, when they realize that the current work processes and procedures can be further improved, they are more likely to reciprocate with constructive suggestions for the team (Chen and Hou 2015).

Therefore, we propose that in addition to improving the quality of dyadic relationships with employees, ethical leadership can positively enhance an individual employee’s promotive voice targeted at the team.

H1

Ethical leadership may positively enhance an individual’s promotive voice.

From a social exchange perspective, the previous literature on ethical leadership has mainly indicated that ethical leaders can improve the quality of the employee–leader dyadic relationship, leading to better individual performance (e.g., Zhu et al. 2015). Employees may reciprocate not only by developing interpersonal relationships with their ethical leaders but by contributing to the entire team (Maynes and Podsakoff 2014; Zhu et al. 2015). Promotive voice is a typical means through which employees help their teams and themselves adapt to dynamic change to achieve innovative and successful work outcomes (Van Dyne et al. 2003). We have already proposed that in a team having an ethical supervisor who creates a caring climate and provides important resources, employees are likely to help the team by providing constructive ideas and suggestions for its improvement. Such promotive voice behavior encourages active new ways of thinking through which employees instrumentally acquire additional organizational resources they can use to accelerate individual task performance (Fuller et al. 2007; Seibert et al. 2001). Further, employees who actively engage in promotive voice are more likely to obtain positive feedback and superior performance evaluations from their supervisors (Fuller et al. 2007), thereby leading to better work outcomes (Chen and Hou 2015).

Thus, in this study, we further propose that employee voice is an important exchange-based mechanism through which ethical leadership promotes individual task performance.

H2

Promotive voice mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and an individual’s task performance.

LLX Facilitates the Effectiveness of Ethical Leadership

The affect theory of social exchange posits that different types of exchange affect the solidarity and identification that an individual feels with their exchange partner and group (Lawler 2001). The strongest affective attachment can be produced when people perceive that their exchange partner strives to contribute so that either one of them can benefit (Berg 1984; Lawler 2001). In other words, people are more willing to develop high-quality interpersonal relationships with individuals or organizations they identify as using their best abilities to provide psychological and physical support (Berg 1984; Lawler 2001). In organizations, the relationship between a supervisor and his or her employees is nested within the relationship between that supervisor and his/her upward leader, termed the leader–leader exchange (LLX) (Tangirala et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2012). Supervisors maintaining a mutual exchange relationship with their upward leader may have greater access to organizational resources such as task times, research funds, and external support (Tangirala et al. 2007). Thus, LLX is an indicator of the amount of resources a supervisor obtains within the hierarchical exchange system (Likert 1967; Zhou et al. 2012).

In accordance with the foregoing, we further propose that LLX relates to employee behavior and outcomes by facilitating the individual-level relationship between ethical leadership and promotive voice. Specifically, for supervisors who lack upward resources and mutual support (LLX) compared with their peers, ethical leadership behavior may be extremely helpful to stimulating employees’ promotive voice. Employees’ reciprocal motivation and behavior can be significantly enhanced when they understand that their supervisor and team ethically strive to provide care and support for them under unfavorable conditions and limited organizational resources (e.g., Berg 1984; Lawler 2001). They may develop even greater identification and affective attachment with a team in which people ethically sacrifice their limited resources to achieve collective goals. Under such circumstances, employees are more likely to actively participate in team development by providing constructive ideas and suggestions, and changing currently ineffective work practices to accumulate additional and potential resources that benefit the ethical supervisor and the future of the team (Ng and Feldman 2012). In contrast, when a supervisor obtains higher LLX, i.e., more organizational resources than other teams, employees are likely to develop a perception that their supervisor’s ethical and supportive behavior is simply standard leadership protocol using organizational resources that arise from the upward exchange relationship. Less affective attachment between employees and the focal supervisor may occur in this type of exchange. Hence, we propose the following Hypothesis 3.

H3

LLX moderates the effect of ethical leadership on an individual’s promotive voice. Specifically, when LLX is low, ethical leadership may have a stronger effect on an individual’s promotive voice.

Again, promotive voice behavior can foster the individual learning process through which employees grasp new skills and make fewer mistakes, enhancing routine tasks (Burris 2012; Van Dyne and LePine 1998). In addition, employees may obtain more resources when their suggestions are accepted, leading to better individual performance. Therefore, we propose a moderated mediation hypothesis as follows:

H4

LLX moderates the effect of ethical leadership on an individual’s promotive voice which subsequently leads to task performance. Specifically, when LLX is low, ethical leadership may have a stronger effect on an individual’s promotive voice which subsequently leads to task performance.

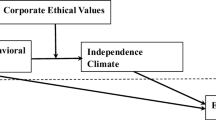

All of the hypotheses are summarized in Fig. 1.

Method

Sample and Procedures

The data in this study were collected from respondents working in a high-tech company located in South China. Questionnaires were distributed to 198 employees who worked in 39 R&D teams. There was one supervisor for each team. The main responsibility of the employees was to develop high-tech software products. To raise the standards of quality and competitiveness of the products, employees were expected to constantly communicate with their supervisors who provided suggestions and feedback, and sought organizational resources, such as research funding and expert support from the upward leader. At the very beginning of data collection, respondents were informed that all of their individual responses would be used only for academic purposes, and they were asked to complete the questionnaires during work time.

The final sample size comprises 176 employees (response rate was 88.9 %). The average age of the employees was 27.63 years (SD = 2.90). Among them, 55 were female (31.3 %). The average tenure was 37.13 months (SD = 28.22). With respect to education, 6.3 % had graduate degrees, 91.4 % had bachelor degrees, and 2.3 % had 3-year diplomas. We also collected data from 37 supervisors. The average age of the supervisors was 29.38 (SD = 3.08). Among them, 6 were female (16.2 %). The average tenure was 51.99 months (SD = 29.91). The average team size was 5.62 (SD = 2.39).

Data were collected at three points in time with 2 months in between to warrant sufficient time lag to separate the measurement of the predictors and mediators from the outcome variables (c.f. Zhou et al. 2012). Specifically, at Time 1, the respondents were required to report their demographic information, such as age, gender, and work tenure. The employee respondents evaluated ethical leadership, whereas their supervisors reported the quality of the exchange relationships with their direct upward leader (LLX). In accordance with previous LLX research (c.f., Tangirala et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2012), the supervisors were asked to rate the quality of the leader–leader exchange relationship (LLX). At Time 2, the supervisors assessed the promotive voice behavior of each employee in their team and the employees were asked to evaluate the quality of the exchange relationship with their supervisor (LMX). At Time 3, the supervisors rated each employee in terms of his or her individual task performance. All of the surveys were translated from English to Chinese, using Brislin’s (1980) recommended translation–back translation procedure.

Measures

Well-established scales were used to measure the constructs of this study, which are summarized as follows.

Ethical Leadership

We assessed ethical leadership using Brown et al.’s (2005) unidimensional 10-item ethical leadership scale. The respondents were asked to evaluate their direct supervisor’s ethical leadership by answering statements such as “He/she makes fair and balanced decisions” and “He/she sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics.” A Seven-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) was used. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75.

LLX

Graen and Uhl-Bien’s (1995) seven-item leader–member exchange (LMX) scale was used to measure the quality of leader–leader exchanges (LLX) in this study (e.g., “Your supervisor understands your job problems and needs” and “Regardless of how much formal authority he/she has built into his/her position, your supervisor would use his/her power to help you solve problems in your work”). A seven-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) was used. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79.

Promotive Voice

We measured employees’ promotive voice behavior using a 5-item scale developed by Liang et al. (2012). Sampling items were “Make constructive suggestions to improve the team’s operation” and “Proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the team.” We also applied a seven-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.98.

Task Performance

We measured the employees’ task performance using the scale of (Zhang et al. 2014). Four items were included in this scale, such as “This employee adequately completes his/her assigned duties.” Supervisors were asked to evaluate their employees’ task performance with these items using a seven-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Control Variables

We included individual-level variables, such as the employees’ gender, age, and work tenure with the current supervisor, and a team-level variable, team size, as control variables in our hypotheses testing. Previous research has noted that these variables are influential to the focal relationships we are interested in (Brown et al. 2005; Brown and Trevino 2006a; Pearce and Herbik 2004). LMX was also controlled for in this study. As mentioned in the literature review, LMX was found to be an important mediator which links upper-level leadership behavior with lower level employee responses (for example, Gu et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2012). (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995) seven-item leader–member exchange (LMX) scale was used. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to assess whether both the employees’ scores on their self-reported measures (i.e., ethical leadership and LMX) and the supervisor-rating measures (i.e., promotive voice and task performance) captured distinctive constructs. The hypothesized four-factor model was specified by loading indicators onto their respective latent variables, and the correlations among the latent variables were freely estimated. The results showed that the four-factor model fit the data well, χ 2 (293, N = 176) = 438.80, comparative fit index (CFI) = .94, standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) = .06, and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .05. The indicators all significantly loaded onto their respective latent factors. Considering that the item contents in the measures of ethical leadership and LMX were similar, an alternative three-factor model was specified by constraining the variances of and covariance between the ethical leadership and LMX factors to make them equal (their correlation equaled 1), and constraining the co-variances between these two factors and other variables to make them equal. The three-factor model (combining ethical leadership and LMX) fit the data significantly worse than the four-factor model, △χ 2 (31, N = 176) =2436.01, p < .01. Therefore, the measures reported by the employees and the supervisors captured distinctive constructs in this study.

Analytic Strategy

In this study, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were proposed at the employee level (level 1), and Hypotheses 3 and 4 were proposed as cross-level moderated mediation effects (level 2). Accordingly, the present data contained a hierarchical structure in which the responses of the employee-level variables were nested within teams. To accommodate this, multilevel modeling was performed to simultaneously estimate the hypothesized multilevel relationships using Mplus6.0 software (Muthen and Muthen 2007). Specifically, ethical leadership, gender, age, and work tenure were level 1-variables, whereas LLX and team size were level-2 variables. Both the mediator and dependent variables (i.e., promotive voice, LMX, and task performance) had variances at both level 1 and level 2. We also used the Monte Carlo method recommended by (Preacher et al. 2010) to estimate the confidence intervals for the hypothesized multilevel effects to determine their significance.Footnote 1

Results

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among the studied variables are shown in Table 1. At the individual level, ethical leadership was positively correlated with promotive voice (r = 0.36, p < .01) and LMX (r = 0.39, p < .01). Meanwhile, both promotive voice and LMX were positively correlated with task performance (r = 0.47, p < .01, and r = 0.62, p < .01, respectively).

Model Estimation

To estimate the hypothesized model (Fig. 1), we included individual-level variables gender, age, and work tenure and team-level variable team size as the control variables with fixed effects on employee’s task performance. Then, we specified the cross-level moderated mediation relationship between ethical leadership, LLX, and promotive voice, which subsequently leads to task performance. We also considered the mediating mechanism of LMX in this model to demonstrate how the social exchange-extended voice mechanism we proposed contributed to the existing knowledge.

To facilitate the interpretation of the research model, individual-level gender, age, and work tenure were group mean centered, and team size, ethical leadership, and LLX were grand mean centered. The results showed that all of the hypothesized relationships were well supported, as shown in Fig. 2.

Path coefficients from the selected model. Note N 176 for individual-level variables, N = 37 for team-level variables. Path coefficients and standard deviations from the selected model. For the sake of brevity, we did not present the effects of all control variables on individual-level and team-level variables. Interested readers may contact the corresponding author for estimates of these effects. ** p < .01, * p < .05

Hypotheses Testing

Hypothesis 1

We proposed that ethical leadership would positively promote an employees’ promotive voice. Figure 2 indicates that ethical leadership was positively related to promotive voice (γ = 0.30, p < .01). Hence, Hypothesis 1 was well supported.

Hypothesis 2

We proposed that promotive voice would mediate the relationship between ethical leadership and an employee’s task performance (ethical leadership → promotive voice → task performance). Figure 2 indicates that promotive voice was positively related to task performance (γ = 0.26, p < .05). To estimate the hypothesized cross-level indirect relationship, we used a parametric bootstrap procedure (Preacher et al. 2010), with 20,000 Monte Carlo replications. The results demonstrated that there was a positive indirect relationship between ethical leadership and task performance via promotive voice (indirect effect = 0.078, 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap CI [.004, .201]). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was well supported.

Hypothesis 3

We proposed that LLX would moderate the relationship between ethical leadership and an employee’s promotive voice. Figure 2 indicates that there is a significant moderating effect of LLX on the relationship between ethical leadership and promotive voice (γ = −0.33, p < .05). Following Cohen and colleagues’ recommendations, we plotted this interaction as conditional values of LLX (one standard deviation above and below the mean) in Fig. 3. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was well supported.

Hypothesis 4

We proposed that LLX would moderate the effect of ethical leadership on promotive voice, which subsequently leads to task performance. Again, with 20,000 Monte Carlo replications, the results indicated that there was a significant moderated mediation effect (indirect effect = −0.087, 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap CI [−.240, −.001]). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was well supported.

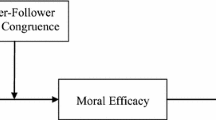

Supplementary Analysis

To explore the important exchange-extended mechanism of promotive voice in the effectiveness processes of ethical leadership, we controlled for the LMX mechanism based on the previous ethical leadership research (e.g., Gu et al. 2015). All of the hypothesized relationships were well supported. However, it is possible that the effect size of the voice mechanism was exaggerated when LMX was entered into the research model. Thus, we also tested an alternative model (shown in Fig. 4). The results indicated that all of the hypothesized relationships were still well supported. Taken together, the supplementary analysis confirms our theoretical model and indicates that our findings are very robust.

An alternative model. Note N = 176 for individual-level variables. N = 37 for team-level variables. Path coefficients and standard deviations from the selected model. For the sake of brevity, we did not present the effects of all control variables on individual-level and team-level variables. Interested readers may contact the corresponding author for estimates of these effects. **p < .01, *p < .05

Discussion

There has been a growing interest in understanding how ethical leadership may enhance employees’ task performance (Zhu et al. 2015). In contrast to the existing literature emphasizing the LMX mechanism, this study contributes to this research stream by examining promotive voice as a new exchange-based mechanism targeted at the team and illustrating the effect of LLX on the relationship between ethical leadership and promotive voice from a social exchange perspective. As hypothesized, we found that ethical leadership is positively related to employees’ promotive voice, which subsequently leads to individual task performance. There is no significant direct effect of ethical leadership on task performance, which means that ethical leadership influences individual task performance mainly through two exchange mechanisms: promotive voice and LMX.

LLX significantly moderated the positive indirect relationship of ethical leadership on individual task performance via promotive voice, such that the positive indirect relationship of ethical leadership with employees’ performance was stronger when LLX was lower. However, the moderating effect of LLX on the relationship between ethical leadership and LMX was not significant. LLX mainly captured the amount of resources a supervisor could obtain from his or her upward leaders to provide for the entire team rather than for the individual employees.

Employees usually tend to feel that they work in a reliable and supportive team when they receive sufficient work and life resources from their team supervisor. This is especially so when they understand that the supervisor, as the team representative, still offers sufficient care and support for the team to achieve its collective goals and objectives even when there are comparatively limited organizational resources. Thus, relationship building (LMX) between employees and supervisors mainly develops and is maintained within the employee–supervisor dyadic relationship, regardless of whether the focal supervisor has a favorable relationship with or obtains resources from his or her upward manager. LLX is an important boundary condition for the relationship between leadership behavior and employees’ reciprocal actions toward the entire team but it is less important to exchanges within the leader–employee dyad.

Theoretical Implications

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, it contributes to social exchange theory and the ethical leadership literature by examining a new social exchange mechanism, the voice mechanism, which facilitates the effect of supervisors’ ethical leadership behavior on employees’ performance outcomes. Contrary to the previous ethical leadership literature emphasizing relationship building between leaders and members (e.g., Gu et al. 2015), this study extends our understanding of the social exchange nature of ethical leadership by highlighting that employees may choose to reciprocate ethical leadership by not only developing dyadic mutual exchange relationships with ethical supervisors, but also by providing constructive ideas and suggestions that are essential to achieving team improvement and their own task goals.

Second, this study provides an important integration between the prior theories of ethical leadership and leader–leader exchange within a cross-level social exchange framework. Specifically, this study demonstrates a substitution effect between ethical leadership and LLX. In the existing ethical leadership literature, researchers have mainly discussed the positive affect of ethical leadership on employee voice (e.g., Brown et al. 2005; Zhu et al. 2015). Less effort has been made with regard to the contextual factors that influence leadership effectiveness in teams. Thus, our research addresses an important question that has not been well considered, regarding when ethical leadership matters more in the workplace.

Managerial Implications

Our findings provide several managerial implications. First, it is important for organizations to identify, select, and promote people who present ethical values and the commitment to become leaders within an organization (Mo and Shi 2015). Ethical leaders provide their followers with psychological trust, care, and support (Brown et al. 2005). Under the supervision of ethical leaders, employees are more willing to provide constructive suggestions and show concern. The findings from our study suggest that organizations should educate supervisors to become aware of the positive effects to be derived from encouraging employees to speak up about their individual performance. Second, supervisors should practice ethical leadership behavior particularly when they have limited upward relationships and resources compared with their peer supervisors within the organization. We strongly recommend that organizations train supervisors to understand that becoming the most powerful link within the organization is not the only way to encourage employees to actively participate in team development. Ethical behavior matters when trying to convince employees within a team, particularly when supervisors have less access to organizational resources.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

This study has a number of strengths. First, whereas past research has generally focused on either individual-level or team-level leadership processes, we examine the relationships between ethical leadership and LLX and employee’s task performance within a cross-level framework. Second, data were collected from multiple sources at three different points in time, which significantly reduces potential common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2012). Third, the proposed research model was estimated following a general path-analytic framework such that all of the hypothesized relationships were examined at the same time (Preacher et al. 2010). As a result, the problems found in piecemeal and causal step approaches for testing mediation (Bauer et al. 2006) were significantly alleviated in this study.

Despite the strengths mentioned above, several limitations remain. First, we did not include prohibitive voice in this study. We suggest that it is reasonable to focus only on promotive voice because in the workplace, constructive suggestions rather than prohibitive reports are more commonly valued as positive reciprocal responses by both employees and supervisors. Nevertheless, we encourage future research to further explore the potential influencing mechanisms of the two types of voice.

Second, we did not capture the detailed mediating mechanisms between LLX and employee voice. For example, supervisors who receive sufficient resources from their upward leaders and provide such resources to employees are likely to develop an empowerment climate, which is essential for employee voice (Zhou et al. 2012). Under the supervision of a high-LLX supervisor, employees are more likely to identify with such a supervisor and the focal team, thereby providing constructive suggestions. We encourage future endeavors in this area to test these potential mechanisms and deepen our understanding of how the effect of the exchange relationship flows from one organizational level to the next.

Third, the research sample was collected in China, which may limit the generalizability of our results. In China, the population has a collectivist view and thus may be more aware of various interpersonal relationships existing within organizations (Mo et al. 2012). As a result, the value of ethical leadership and LLX could be more salient in the Chinese context. In future, research examining the implications from this study in different cultural contexts is recommended.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on an important question regarding multiple social exchange mechanisms that link ethical leadership to employee task performance from a multilevel perspective. Our results show that ethical leadership may enhance employees’ promotive voice which subsequently leads to task performance. Further, LLX moderates the relationship between ethical leadership and promotive voice. Specifically, ethical leadership may significantly enhance employees’ promotive voice when leader–leader exchange is low. Thus, this study extends our understanding of the social exchange nature of ethical leadership by demonstrating the voice link. Moreover, this study responds to an important question regarding the boundary of ethical leadership effectiveness by introducing cross-level LLX from an affective perspective of social exchange.

Notes

More information about the R program can be found at http://www.quantpsy.org.

References

Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11, 142–163.

Berg, J. H. (1984). Development of friendship between roommates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 346–356.

Blanc, P. M., & Gonzalez-Roma, V. (2012). A team level investigation of the relationship between leader-member exchange (LMX) differentiation, and commitment and performance. Leadership Quarterly, 23, 534–544.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 398–444). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Trevino, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Burris, E. R. (2012). The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 851–875.

Chan, S. C. H., & Mak, W. M. (2012). Benevolent leadership and follower performance: The mediating role of leader-member exchange (LMX). Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29, 285–301.

Chen, A. S., & Hou, Y. H. (2015). The effects of ethical leadership, voice behavior and climates for innovation on creativity: A moderated mediation examination. Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 1–13.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 869–884.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoads, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 565–573.

Fuller, J. B., Barnett, T., Hester, K., Relyea, C., & Frey, L. (2007). An exploratory examination of voice behavior from an impression management perspective. Journal of Managerial Issues, 29, 134–151.

Gao, L. P., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2011). Leader trust and employee voice: The moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 787–798.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219–247.

Gu, Q. X., Tang, T. L. P., & Jiang, W. (2015). Does moral leadership enhance employee creativity? Employee identification with leader and leader-member exchange (LMX) in the Chinese context. Journal of Business Ethics, 126, 513–529.

Hsiung, H. H. (2012). Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: A multi-level psychological process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 349–361.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Detert, J. R., Trevino, L. K., & Edmondson, A. C. (2009). Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163–193.

Lawler, E. J. (2001). An affect theory of social exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 321–352.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 71–92.

Likert, R. (1967). The human organization: Its management and value. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., Fu, P. P., & Mao, Y. (2013). Ethical leadership and job performance in China: The roles of workplace friendships and traditionality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86, 564–584.

Liu, W., Tangirala, S., Lam, W., Chen, Z. G., Jia, R. T., & Huang, X. (2015). How and when peers’ positive mood influences employees’ voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100, 976–989.

Masterson, S. S., Lewis, K., Goldman, B. M., & Taylor, M. S. (2000). Integrating justice and social exchange: The differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 738–748.

Maynes, T. D., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2014). Speaking more broadly: An examination of the nature, antecedents, and consequences of an expanded set of employee voice behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 87–112.

Mo, S. J., & Shi, J. Q. (2015). Linking ethical leadership to employee burnout, workplace deviance and performance: Testing the mediating roles of trust in leader and surface acting. Journal of Business Ethics, online first.

Mo, S. J., Wang, Z. M., Akrivou, K., & Booth, S. (2012). Look up, look around: Is there anything different about team-level OCB in China? Journal of Management & Organization, 18, 833–844.

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5, 373–412.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2007). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Author.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 216–234.

Pearce, C. L., & Herbik, P. A. (2004). Citizenship behavior at the team level of analysis: The effects of team leadership, team commitment, perceived team support, and team size. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144, 293–310.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 539–569.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233.

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Crant, J. M. (2001). What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel Psychology, 54, 845–874.

Tangirala, S., Green, S. G., & Ramanujam, R. (2007). In the shadow of the boss’s boss: Effects of supervisors’ upward exchange relationships on employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 309–320.

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56, 5–37.

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1359–1392.

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 108–119.

Zhang, Y. W., LePine, J. A., Buckman, B. R., & Wei, F. (2014). It’s not fair…or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor-job performance relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 675–697.

Zhou, L., Wang, M., Chen, G., & Shi, J. Q. (2012). Supervisors’ upward exchange relationships and subordinate outcomes: Testing the multilevel mediation role of empowerment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 668–680.

Zhu, W. C., He, H. W., Trevino, L. K., Chao, M. M., & Wang, W. Y. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower voice and performance: The role of follower identifications and entity morality beliefs. Leadership Quarterly, 26, 702–718.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Grant No. 71302102 awarded to Shenjiang Mo and Grant No. 71425004 awarded to Junqi Shi from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mo, S., Shi, J. The Voice Link: A Moderated Mediation Model of How Ethical Leadership Affects Individual Task Performance. J Bus Ethics 152, 91–101 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3332-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3332-2