Abstract

This study examines how the accounting profession disciplines its members for professional misconduct in periods of increased public scrutiny. We conjecture and find that increased public scrutiny of the Canadian accounting profession, marked by the establishment of the Canadian Public Accountability Board in 2003, is positively associated with the severity of punitive sanctions administered by the profession’s disciplinary committees. We find that disciplinary committees are more likely to also demand rehabilitation outcomes and greater future monitoring for offenders. Finally, reporting of discipline outcomes has increased in outlets internal to the accounting profession, but not in publications targeted outside to the public. This latter finding is consistent with the private interest theoretical model of professional ethics developed by Parker (Acc Organ Soc 19:507–525, 1994) as evidence of a latent motivation of the profession to protect its professional private interests. Exploratory analyses indicate that punishment, rehabilitation, and reporting in external publications significantly influence whether offenders return to good standing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Regulatory oversight of the accounting profession underwent dramatic changes in the early 2000s in both the United States and Canada. In the United States, the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 established the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to protect investors and further the public interest (US House of Representatives 2002). In Canada, the Canadian Public Accountability Board (CPAB) was established in 2003 to enhance the transparency of the accounting profession’s activities by providing external scrutiny and oversight (e.g., Canadian Securities Administrators 2014). Although the threat of eroding professional self-regulation differed between the United States and Canada by nature of the different authorities bestowed on the PCAOB and CPAB (Baker et al. 2014), both accountability boards increased the external public scrutiny of the accounting profession (Ben-Ishai 2008). At the same time, professional accounting bodies continued to operate disciplinary processes to address individual member’s violations of professional conduct codes. This study compares disciplinary sanctions given to individual members guilty of professional misconduct before and after the introduction of Canada’s accountability board to determine how the accounting profession responds to increased public scrutiny.

An important characteristic of a profession is its relationship with the public it serves (Cohen and Pant 1991). To serve the public interest, professions establish codes of professional conduct to influence the ethical behavior of its members (Higgs-Kleyn and Kapelianis 1999) and to demonstrate the “profession’s desire and responsibility” (Cohen and Pant 1991, p. 45) to self-regulate. A component of that self-regulation is the responsibility to establish processes for complaints, investigations, and disciplinary sanction for the professional misconduct of its members (e.g., Beets and Killough 1990). In this context, external accountability boards such as the PCAOB and CPAB may be perceived as a threat to the self-regulation of the accounting profession (e.g., Anantharaman 2012; Hilary and Lennox 2005). Presently, it is unclear how the profession has responded to the threat of diminished self-regulation in the very matter that caused the accountability boards to be established in the first place—individual member professional misconduct. This study provides evidence of the profession’s response.

To investigate the profession’s response, we draw on the private interest theoretical model of professional accounting ethics developed by Parker (1994) as a basis of our hypotheses. This model predicts that the increased external scrutiny of the accounting profession impacts the professional authority of the profession. In response, the profession will increase the discipline sanctions administered by the professional accounting bodies to signal that it is capable of self-regulating and protecting the public interest so as to minimize future interference from external bodies. To examine whether disciplinary committees have responded in this manner, we hand collect all the publicly available disciplinary cases from the database of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Ontario (ICAO).Footnote 1 The ICAO database contains discipline information for our sample of 403 disciplinary cases involving individual member misconduct. Three primary analyses are conducted: first we examine whether disciplinary punishment, rehabilitation demands, and subsequent monitoring are greater in the period after the establishment of the CPAB than the period before the CPAB. Second, we examine whether the discipline sanctions are disproportionately more pronounced for private interest code violations than for public code violations after the establishment of the CPAB. Third, we examine whether reporting of discipline sanctions is disproportionally skewed to outlets internal, rather than external, to the profession after the establishment of the CPAB.

The analyses document that discipline sanctions administered by the ICAO increased in regard to the severity of discipline sanctions, rehabilitation demands, and subsequent monitoring after the increased public scrutiny of the Canadian accounting profession in 2003. Based on the private interest theoretical model of professional accounting ethics developed by Parker (1994), these findings are interpreted as the profession signaling that it is capable of self-regulation to minimize interference from external bodies, and maintain the profession’s ability to self-regulate and protect the public interests. We also find that reporting of discipline sanctions has changed under the increased public scrutiny. Specifically, the extent of internal reporting has increased, but the level of external reporting has not. This latter finding suggests a latent motivation of the profession to protect its professional private interests.

This study makes four contributions to the literature. This study is the first to document that the increased public scrutiny by the accountability boards is associated with how a professional accounting body disciplines its members. Focusing on the year 2003 in which the Canadian Public Accountability Board was established, marking an increase in public scrutiny, we find that the severity of discipline sanctions against individual members of the accounting profession increased after 2003. By focusing on sanctions that provide both general and specific deterrence to the membership of the ICAO, we find that punishment severity has increased across both public and private interest code violations.

Second, this study contributes to the literature by differentiating between disciplinary sanctions that punish offenders and those that rehabilitate and monitor them. We find that certain rehabilitation and monitoring efforts were greater after 2003 than during the period before. By extending the focus of prior research on the severity of punishment to include rehabilitative and monitoring actions, we are able to demonstrate that the profession has been increasingly using rehabilitation tactics to protect the public interest and monitoring sanctions to protect the accounting profession’s private interest.

Third, we find that the outlets used to report discipline sanctions have changed in the period after 2003 compared to the period before. Specifically, the extent of disclosure of the discipline sanction has increased after 2003 internally within the membership, whereas the extent of discipline sanction reporting in external sources has not increased. Prior research has suggested that a lack of public external transparency is self-serving to the profession because it aims to avoid further reputational costs and erosion of public confidence in self-regulation (e.g., Canning and O’Dwyer 2001; Bédard 2001). Accordingly, the finding of increased internal, but not external, reporting is consistent with a latent motivation for the profession to emphasize protection of its private interest over that of the public interest.

The fourth contribution of this paper is preliminary evidence we present on the ultimate effectiveness of punishment, rehabilitation, and reporting outcomes in returning members to good standing. Using a subset of data in which offenders are subsequently reported as having returned to being a member in good standing, we find that more severe punishment and greater rehabilitation efforts are positively associated with a member’s successful remediation, with rehabilitation generating a greater effect. Threats of future punishment appear to have no significant effect and greater external reporting is associated with less successful remediation outcomes, providing preliminary evidence for disciplinary committees to consider when determining future sanctions and for scholars to examine through future research.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. The following section provides an overview of the professional discipline literature and offers hypotheses based on the private interest theoretical model of professional accounting ethics developed by Parker (1994). The subsequent sections then discuss the research method followed by the empirical results. The final section concludes with a discussion of professional discipline and oversight of the accounting profession.

Background and Hypothesis Development

Professional Discipline: A Manifestation of Professional Ethics

Professional discipline and sanctions are perceived to be important by the accounting profession (e.g., Peytcheva and Warren 2013) and have been found to influence individual member behavior (Ugrin and Odom 2010). Loeb (1972) conducted one of the first studies to examine professional discipline by focusing on discipline cases in the United States considered by the state society and state board of one Midwestern state between 1905 and 1969. A key contribution of Loeb’s study, which influenced the subsequent literature, was distinguishing among offenses against clients, the public, and colleagues.Footnote 2 Loeb documented that the majority of offenses resulting in sanctions were offenses against colleagues (rather than against the public or clients). Although fewer in number, offenses against the public and clients were sanctioned more severely compared to sanctions for offenses against colleagues; a survey conducted by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants confirmed that this relationship generalized across state boards. Finally, Loeb found that, after holding constant the nature of the offense, the severity of the sanction was greater when the discipline case received notoriety (for example, public inquiries, publicity in mass media).Footnote 3

Extending Loeb’s findings, subsequent research examining the professional accounting bodies’ codes of ethical conduct and related discipline processes has documented an underlying tension: protection of the public interest versus protection of the profession’s private interest. Historical analyses in Canada (Neu and Saleem 1996), the United States (Preston et al. 1995), and Australia (Parker 1987) have determined that the emergence and evolution of codes of conduct in the accounting profession have not necessarily occurred solely for the often-expressed protection of the public interest. Rather, these historical analyses claim the accounting profession’s codes of conduct have emerged and evolved as a result of external threats to the profession, implying that the codes serve the often-unstated, self-interested goal of legitimizing and privileging the profession and its members.

Accordingly, research on disciplinary enforcement of the professional code of conduct has differentiated between public and private interests. This research defines the public interest as the “manifest and latent motivation of ethical codes to protect the economic interests of professional members’ clients and of third parties who place reliance on the pronouncements and advice delivered by both the professional body and its members” (Parker 1994, p. 509). In contrast, the private interest is defined as the “latent motivation of ethical codes to protect the interests of the professional accounting body corporate and its member…[including]…the professional body’s social status, political power, and influence over economic and business activity…[and]…the social standing and income-generating capacity of the members” (Parker 1994, p. 509). To incorporate the greater voice given to the private interests of the accounting profession and its members, Parker (1994) developed a private interest theoretical model of professional accounting ethics that highlighted how the accounting profession’s ethical codes not only segregate the accounting profession from the business community, but also enable it to control and protect its members. Parker’s argument is that professional insulation minimizes interference from external parties and promotes the profession’s ability to self-control, ultimately leading to an enhancement of professional authority. Stated differently, by defining the jurisdiction of accounting practices, the profession secures sole rights to those practices. This professional authority then influences and is influenced by factors that impact the members’ socio-economic status because the profession will react to preserve and enhance such status (see also Canning and O’Dwyer 2003).

Recognizing that the discipline process and sanction outcomes provide an insight into the profession’s private interests in the code of ethical conduct, Parker applies the theoretical model to discipline cases in Australia by categorizing each case as a private interest offense or a public interest offense. Parker finds support for the theoretical model as private interest offenses were prosecuted more often and tended to receive harsher sentences compared to public interest offenses. Parker also interpreted other observations in the data (e.g., lack of offenders’ name disclosed in the published discipline cases, nature of cases, and nature of sanctions) as being consistent with the private interest model of professional accounting ethics. The current study extends beyond the general observations noted by Parker (1994) by examining the association between a change in the accounting institutional context (i.e., establishment of an accountability board) and changes in professional decision making as evidenced by disciplinary actions.

The Accounting Profession’s Enforcement of Ethical Behavior Through Disciplinary Action

In response to corporate failures and financial misreporting in the early 2000s, major institutional changes were undertaken to remedy perceived deficiencies in the accounting profession (Baker et al. 2014). In the United States, the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 increased external scrutiny of the profession and the authority and mandate given to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) threatened to end the self-regulatory privileges previously bestowed on the profession (e.g., Anantharaman 2012; Hilary and Lennox 2005; Lennox and Pittman 2010; DeFond 2010). In Canada, the Canadian Public Accountability Board (CPAB) was established in 2003, pursuing a vision of “[e]ffective regulation—proactively identifying current and emerging risks to the integrity of financial reporting in Canada, assessing how auditors effectively respond to those risks, and engaging those charged with governance, regulators, and standard setters to develop sustainable solutions” (CPAB 2012).Footnote 4 Although differences exist in the authority of the PCAOB in the United States and the CPAB in Canada (Baker et al. 2014; Ben-Ishai 2008; Canadian Securities Administrators 2014), both accountability boards provide oversight to the accounting profession and, through the lens of Parker’s private interest theoretical model of professional accounting ethics, impact professional authority through increased scrutiny.Footnote 5 Whereas the PCAOB has already limited some of the self-regulatory privileges of the accounting profession in the United States, in Canada the profession “…has largely been able to retain its ability to regulate itself based on an appeal to professional responsibility which is largely accepted by the Canadian public and government” (Baker et al. 2014, p. 386). This appeal to professional responsibility, coupled with an ongoing vulnerability to losing self-regulatory privileges, makes the Canadian context appropriate for investigating whether disciplinary behaviors have changed throughout the period of increased scrutiny that follows the establishment of the CPAB.

Previous research has found that when the accounting profession’s authority is threatened (for example, by means of external interference or the profession’s ability to self-control), the profession’s enforcement of its code of conduct changes as evident in the profession’s discipline cases. Specifically, Fisher et al. (2001) examined a unique time period in the United Kingdom when there was increased public scrutiny of the profession and legislation impacting the profession’s ability to self-regulate. Fisher et al. (2001) documented that in the face of external threats to its professional status, the rate of disciplinary action involving members increased. The current study differs from Fisher et al. (2001) in significant ways: first, this study involves greater uncertainty about the initial and ongoing actions of a newly established accountability board in Canada in contrast to Fisher et al. (2001), who examined a setting in which defined changes to U.K. corporate law were made that gave the Ministry the power to determine auditing practice rights. The potential impact of establishing an accountability board on the accounting profession’s discipline outcomes is an open research question. Second, the current study examines the decisions reached by disciplinary boards rather than the number of discipline cases brought to those boards. This distinction is important because the accounting profession has limited ability to influence the number of complaints received but it does have significant discretion in determining the sanctioning of its members.

Complementing Fisher et al.’s (2001) investigation of the rate of disciplinary action, Bédard (2001) considered the characteristics of the punishments administered through Quebec’s disciplinary process. Specifically, he identified factors associated with four levels of increasing punishment severity: reprimand, fine and reprimand, temporary suspension, and permanent suspension. He also characterized punishments by the amount of fines and length of temporary suspensions. We aim to expand this characterization of available sanction options by considering additional aspects of punishment (e.g., charging the offender for investigation costs, threatening suspension for future violations, and disallowing future services). Also, we consider the possibility that punishment is not the only means by which the accounting profession controls its members and serves the public interest. As in the medical profession (e.g., Alm et al. 2013), the accounting profession’s disciplinary committees also can require members to complete additional professional education in efforts to rehabilitate them and can subject them to subsequent monitoring. A final dimension we consider, through which the accounting profession influences member behavior and public perceptions, is reporting disciplinary actions in publications of the profession and in other outlets directed to the general public. Prior research has examined the reporting of accounting disciplinary actions in only a limited fashion because the avenues through which such actions can be (Canning and O’Dwyer 2001) and are selected (Bédard 2001) have been restricted.

Punishment Severity: H1

Parker’s (1994) private interest model of professional accounting ethics predicts that the accounting profession responds to threats that potentially undermine the authority and self-regulation of the accounting profession through actions that preserve and enhance its status. Fisher et al. (2001) provide initial evidence of such action in the U.K., as measured by the rate of disciplinary action. This model and evidence lead us to hypothesize that increased scrutiny of the Canadian accounting profession marked by the establishment of CPAB is likely to increase the severity of discipline actions within the profession. The increased severity would serve as a signal that the profession is capable of self-regulation to minimize interference from external bodies and maintain the profession’s ability to self-regulate.

H1

Severity of disciplinary punishments is greater in the period after 2003 than the period before 2003.

Private Versus Public Interests: H2

By examining discipline sanctions (e.g., Loeb 1972; Parker 1994; Mitchell et al. 1994; Canning and O’Dwyer 2001) and the profession’s complaint processes (e.g., O’Dwyer and Canning 2008), prior research has identified that professional discipline may be focused more on protecting the private interest of the profession than on protecting the public interest. However, these results are not entirely conclusive (e.g., Fisher et al. 2001; Bédard 2001). For example, Fisher et al. (2001) did not find a difference in the proportion of private versus public disciplinary cases in the presence of public scrutiny. Fisher et al.’s (2001) inability to detect such a relationship may have arisen from their use of a measure (number of discipline cases filed) that was too coarse; as discussed previously, our sanction measures are more likely to detect such a relationship should it exist. Bédard (2001) also observed that private interests were not always favored over public interests. Instead, he showed that the balance between private interest and public interest can vary depending on the degree of regulation and public involvement (i.e., external interference and self-control using the terminology of Parker’s theoretical model). Specifically, by examining the unique disciplinary process in Québec, Bédard discovered that during the inquiry stage of the discipline process, when the extent of government regulation and public participation is low, greater voice is afforded to the private interest of the profession. But, in contrast during the trial stage, which involves greater government regulation and public participation, greater voice is afforded to the public interest of the profession.

As discussed by Bédard (2001), the province of Québec’s public participation in the disciplinary process is unique and unlike other Canadian provinces such as Ontario.Footnote 6 Accordingly, we base our hypotheses about the relative emphasis of private versus public interests on Parker’s (1994) private interest model of professional accounting ethics and Fisher et al. (2001)’s hypothesized, but unsupported, difference in the proportion of private versus public disciplinary cases in the presence of public scrutiny. Specifically, we expect the increase in the severity of punishment after 2003, predicted in H1, to be more pronounced for conduct that violated the private interest as compared to conduct that violated the public interest.

H2a

Increased severity of disciplinary punishments after 2003 is more pronounced for private interest code violations than for public interest code violations.

In a variety of disciplines ranging from medicine, nursing, and dentistry (e.g., Strong 2011; Pande and Maas 2013) to accounting (e.g., Brooks 1989; Canning and O’Dwyer 2001), the literature has questioned the transparency of reporting the disciplinary process and sanction outcomes of professional bodies. Transparent reporting promotes member education of professional misconduct and serves as a deterrent mechanism (Parker 1994; Brooks 1989); however, public disclosure may also erode the public’s faith in the self-regulatory profession. When deciding how to disclose discipline sanction outcomes, the accounting profession may choose to publish the results internally to the membership (e.g., internal reports and newsletters) and/or in external sources (e.g., newspapers). Consistent with the preceding theory, we hypothesize that after the introduction of Canada’s accountability board, the reporting of discipline actions will increase within the profession. Analogous to the reasoning underlying H1, the increased reporting would serve as a signal that the profession is capable of self-regulation to minimize future interference from external bodies, and specific to Canada, maintain the profession’s ability to self-regulate.Footnote 7 Moreover, distinguishing between internal and external publication venues allows us to determine whether the profession’s relative attention to private versus public interests has shifted since CPAB’s introduction in 2003. Consistent with the reasoning underlying H2a, and augmented by the profession’s desire to avoid further reputational costs and erosion of public confidence in self-regulation, we expect the increased reporting of discipline sanctions after 2003 to be more pronounced for internal reporting than external reporting.

H2b

Increased reporting of discipline sanctions after 2003 is more pronounced for internal reporting than external reporting.

Rehabilitation and Monitoring: H3 and H4

As compared to discipline sanctions that are focused on deterring unethical behavior through subsequent punishment, sanctions that focus on rehabilitation aim to improve the substandard competencies of an individual member. Rehabilitation is a distinct strategy (Robinson 2008) that is, “…a targeted intervention inculcating self-controls, reducing danger, enhancing the security of the public” (Garland 2001, p. 176). As such, sanctions in the form of mandated continuing professional education are, presumably, intended to rehabilitate the individual member and bring his or her membership status back to good standing.

Moriarity (2000) examined rehabilitation and other AICPA discipline sanctions before and after the adoption of the 1988 Code of Professional Conduct. Similar to the context for the present study, Moriarity noted the 1988 code reform was precipitated by numerous events that called into question the accounting profession’s self-regulation and ability to protect the public interest. Focusing on substandard professional service offenses (e.g., relating to independence, competence, etc.), Moriarity documented that the 1988 reform was followed by an increase in the extent of rehabilitation in the form of continuing professional education (CPE) courses. Moriarity’s empirical analysis showed that rehabilitation did not substitute for punishment; the number and severity of these sanctions also increased following the 1988 reform. Thus, consistent with the theory underlying H1, we propose that increased scrutiny of the Canadian accounting profession marked by the establishment of CPAB will increase the likelihood that the profession’s disciplinary committees require rehabilitation. Increased likelihood of rehabilitation would serve as a signal that the profession is capable of self-regulation to minimize interference from external bodies and maintain the profession’s ability to self-regulate.

H3

Likelihood of rehabilitation sanction is greater in the period after 2003 than the period before 2003.

To our knowledge, the prior literature has not yet examined the extent to which discipline committees demand that offenders subject themselves to ongoing supervision and subsequent reinvestigation—a sanction we refer to as monitoring. As in the case of rehabilitation, monitoring can be required in addition to any punishment or other sanctions but its nature differs from rehabilitation (e.g., continuing professional education courses) because it occurs in a more private setting (e.g., reviews and supervision of work performed). Consistent with the theory underlying H1 and H3, we propose that increased scrutiny of the Canadian accounting profession marked by the establishment of CPAB will increase the likelihood of subsequent monitoring within the profession. The increased likelihood of a subsequent monitoring sanction, again, would serve as a signal that the profession is capable of self-regulation to minimize interference from external bodies and maintain the profession’s ability to self-regulate.Footnote 8

H4

The likelihood of being subjected to subsequent monitoring is greater in the period after 2003 than the period before 2003.

Research Method

Data

We hand collected records of all the discipline cases published by the ICAO from 1984 to August 2014. The data are publicly available on the ICAO’s website. A research assistant, who did not know the study’s hypotheses, was trained to code each discipline case using a pre-determined coding key developed by one of the authors (see Appendix 1 for coded measures relevant to the analyses reported in this paper). Although coding involved little judgment, one of the authors verified the assistant’s coding for a sample of 80 cases representing 20 % of the final sample. Zero discrepancies were noted, suggesting that the assistant’s initial coding was reliable.

Sample

We initially identified 425 cases but data were missing for 22 cases, so we are left with a final sample of 403 discipline cases. Nearly one-half of the cases (47.0 %) involved multiple violations of the rules of professional conduct. Appendix 2 reports the distribution of cases across the various rules of professional conduct, classified as relating to private or public interests based on Parker’s (1987) analysis. For a large majority of cases, these violations led to reprimand (95.8 %) and fines (88.8 %); suspensions were less common outcomes (20.0 %) and were only slightly more frequent than mandatory rehabilitation through CPE training (18.0 %). Subsequent monitoring was recommended in fewer than 10 % of cases.

Research Design

Tests of hypotheses employ both univariate and multivariate methods. Univariate analyses provide initial evidence pertaining to changes in punishment severity (H1 and H2a), reporting outlets (H2b), rehabilitation (H3), and monitoring (H4) around the period of CPAB’s establishment in 2003.Footnote 9 The univariate analyses are presented in Table 1. Data pertaining to punishment severity (H1 and H2a) indicate punishment severity at an aggregate level (SEVERITY) and also show details of specific punishments grouped as minor punishments (REPRIMAND, FINE and DOLLARS_OF_FINE), threat of severe punishment, and major punishments (SUSPENDED, MONTHS_OF_SUSPENSION and DISALLOWED_SERVICES). These analyses encompass Bédard’s (2001) dimensions of punishment (e.g., reprimand, fine, suspensions), as well as other aspects of punishment not previously reported in the literature (e.g., charging the offender for investigation costs, threatening suspension, and disallowing future services). The univariate analyses also consider two measures of rehabilitation, including the existence of a requirement to complete CPE training and the extent of training (as measured by number of required courses), and three dimensions of monitoring, including the requirement to submit to ongoing supervision, subsequent reinvestigation, and other future actions required of the offender. Finally, univariate analyses indicate the extent to which disciplinary information is made available to the general public in outlets internal to the membership beyond being restricted solely to the member newsletter CheckMark, versus external outlets such as The Toronto Star or other newspapers.

The multivariate analyses use an ordered logit regression to test H1, H3, and H4, by estimating the following equation:

where discipline is measured as one of the three ways:

-

(1)

PUNISHMENT SEVERITY (for H1) is measured as

-

a.

SEVERITY Based on Bédard’s (2001) sanction level, modified to include threat of suspension, resulting in a 5-point scale where reprimand = 1, fine = 2, threat of suspension = 3, temporary suspension = 4, and indefinite suspension = 5.

-

b.

DOLLARS_OF_FINE Equal to the specific dollar value of the fine.Footnote 10

-

c.

MONTHS_OF_SUSPENSION Equal to the number of months the member was suspended.

-

a.

-

(2)

REHABILITATION (for H3) is measured as

-

a.

CPE_CLASS Equal to 1 if the member is required to complete CPE; 0 otherwise.

-

a.

-

(3)

MONITORING (for H4) is measured as

-

a.

SUPERVISION Equal to 1 if the member is required to be supervised in the future; 0 otherwise.

-

b.

FUTURE_ACTION Equal to 1 if future actions other than CPE training are required of the member; 0 otherwise.

-

a.

- POST_CPAB :

-

Equal to 1 if the discipline was assigned after 2003; 0 otherwise

- PUBLIC_TRI :

-

Equal to 0 if all violations were identified as private interest code violations, 1 if the case involved both private and public code violations, and 2 if all violations were identified as public interest code violations

- MULTIPLE_VIOLATIONS :

-

Equal to 1 if the action involved more than one violation; 0 otherwise

- GUILTY_PLEA :

-

Equal to 1 if the member pleaded guilty and accepted full responsibility for the violation; 0 otherwise

- YEAR :

-

A series of indicator variables by year

H1 predicts that POST_CPAB will have a positive effect on PUNISHMENT SEVERITY, so we expect a positive coefficient on this variable. H3 predicts that POST_CPAB will have a positive effect on REHABILITATION, so we expect a positive coefficient on POST_CPAB in this specification. Lastly, H4 predicts a positive coefficient on POST_CPAB when MONITORING is the dependent measure. Equation (1) controls for three characteristics of the cases. First, because Bédard (2001) shows public interest code violations result in more severe punishments, we include PUBLIC_TRI for which we expect a positive coefficient.Footnote 11 Second, because 47 % of cases involve multiple violations, we include MULTIPLE_VIOLATION to identify cases involving greater potential violation. This control variable allows us to estimate Eq. (1) using the entire dataset of 403 cases.Footnote 12 Third, following Bédard (2001), we control for the certainty of the case against each offender. Bédard measured case uncertainty by coding objective and subjective case facts as favoring or opposing the offender. Because we did not have these data available, we proxy for the certainty of the offender’s case with GUILTY_PLEA, reasoning that offenders are more likely to plead guilty when the case against them is more certain. To control for differences in the composition of the discipline committee over the 30-year sample period, we include indicator variables for year. Lastly, for specifications estimating DOLLARS_OF_FINE, we include a control for the cost of the investigation as this is likely to impact the magnitude of the fine.

H2a is tested by modifying Eq. (1) to include an interaction between PUBLIC_TRI and POST_CPAB, as follows:

H2a predicts the POST_CPAB effect to be stronger for private interest code violations, so we expect a negative coefficient on the interaction variable (POST_CPAB x PUBLIC_TRI).

H2b is tested by modifying Eq. (1) to model the use of two different measures of reporting, as follows:

where REPORTING is measured as one of the two ways:

-

(1)

PUBLISHED_INTERNALLY Equal to 1 if the order is published for the public in a form and manner determined by the Discipline Committee to all members of the Institute (i.e., not solely restricted to the member newsletter CheckMark); 0 otherwise.

-

(2)

PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY Equal to 1 if the order is published for the public in newspapers and other external avenues; 0 otherwise.

H2b predicts the POST_CPAB effect to be positive and larger when modeling PUBLISHED_INTERNALLY, the decision to publish discipline outcomes internally, so we expect a positive coefficient on the variable (POST_CPAB) and we expect that the coefficient will be larger than the coefficient on POST_CPAB when modeling PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY.Footnote 13

Results

Univariate Mean Analysis

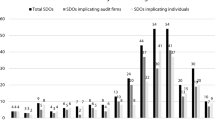

Each of H1, H3, and H4 provides a directional prediction in regard to different sanction options: H1 considers punishment severity, H3 addresses rehabilitation use, and H4 relates to subsequent monitoring.Footnote 14 Table 1 provides evidence in support of all three hypotheses. Panel A of Table 1 presents the results of the univariate mean analysis of disciplinary sanctions in the pre- and post-CPAB periods across the sample of the 215 cases that involved only a single public or single private code violation; these data also are subdivided into private and public interest code violations.Footnote 15 Panel B provides pre-PCAB/Post-PCAB analysis of the entire population of 403 cases.

Punishment Severity (H1)

The pre- and post-CPAB comparisons in Table 1 are generally consistent with H1 suggesting that punishment sanctions have increased in the post-CPAB era. Specifically, the evidence suggests that in the post-CPAB environment we find increased severity overall using our aggregate measure based on Bédard (2001). The mean SEVERITY (measured on a 5-point scale) increased from 2.614 in the PRE_CPAB era to 2.920 in the POST_CPAB era, a difference that is statistically significant at a 5 % level of significance. Additionally, the DOLLARS_OF_FINE (measured using inflation-adjusted 2012 constant dollars) increased from an average of $6,021 to $9,559, which is statistically significant at a 5 % level of significance.

If a disciplinary committee decides that a violation does not warrant a major punishment, the committee may add to a minor punishment the threat of more severe punishment should the offender commit violations in the future. The results in Panel A of Table 1 show that for both private and public interest code violations, the disciplinary committee is more likely to threaten major punishment in the post-CPAB environment than the pre-CPAB environment. This likelihood increased from 43.1 % (27.7 %) to 61.9 (47.4 %) for private (public) code violations. Both increases are statistically significant in one-tailed tests with a 10 % level of significance, providing additional evidence consistent with H1's prediction of increased punishment severity in the post-CPAB era. Panel B of Table 1 also shows an increase in threat of severe punishment.

In the Major Punishment section of Table 1, the evidence suggests that the disciplinary committee is more likely to forbid offenders from providing specific services to the public in the future; this denial of future services is evident overall for the single violation sample, the total sample in Panel B and, specifically for public violations in Panel A.

Although many of the punishment severity measures in both panels of Table 1 are consistent with H1, the table does identify one exception. The results in Panel A suggest a lower rate of suspensions for single violation cases with a private code violation. This evidence is not consistent with H1 as it suggests a decrease in the severity of sanctions in the post-CPAB era. It appears that rather than suspending the offender altogether, the profession has come to favor restricting the offender’s ability to provide future services, which has risen from 1.6 to 6.8 % of single infraction cases.

Rehabilitation (H3)

H3 predicts rehabilitation sanctions will be more likely in the post-CPAB period. The evidence reported in this section of Table 1 suggests that, for the single violation cases, total population of cases, and single public internal code violations in the post-CPAB environment, the discipline committee is more likely to retrain and attempt to rehabilitate the offender through increases in the likelihood of requiring additional CPE training. In the case of a single public violation there is also an increase in the extent of CPE training (measured by number of classes) at a 10 % level of statistical significance.

Monitoring (H4)

Discipline committees can require offenders to propose a plan for ongoing supervision, submit to that supervision, and allow subsequent reinvestigation by the profession’s professional conduct committee. Table 1 Panel B, which provides evidence of the overall sample of 403 cases, suggests that there was an increase in the likelihood of required supervision from 4.8 to 11.4 % of cases resulting in a difference statistically significant at a 5 % level. Table 1 Panel A also suggests a statistically significant increase in the probability of the disciplinary committee requiring an offender of private interest codes to submit to monitoring of his or her future actions, including making available or delivering examples of the offender’s work to the professional conduct committee. The likelihood of such actions for private interest code violations increased from 20.4 % during the pre-CPAB era to 42.8 % in the post-CPAB era. Other monitoring mechanisms, such as submitting to ongoing supervision and periodic reinvestigation, were rarely applied to private interest code violations during the sample period (less than 4.7 %). In terms of single violation public interest code violations, the evidence in Table 1 does not suggest an increase in the likelihood of monitoring sanctions.

Reporting Outlets (H2b)

Another decision of the discipline committee is the ability to communicate to the public the details of the offense, the offender, and the disciplinary action. Communication has the potential to provide important transparency to the public regarding the profession’s disciplinary process, which is important in a self-regulating system. Communication to the public however can be made through either internal or external sources. Internal sources benefit the profession’s private motives of dissuading other members from similar offenses by making the case visible to the membership; however, internal outlets are more difficult for the non-membership public to access. External sources have the benefit of being highly visible to the non-membership public but have the potential to draw negative attention to the profession itself. Table 1 presents evidence that the profession has increased reporting in the post-CPAB environment for both private and public interest code violations but has chosen to do so by making the information available to the public primarily through internal sources. This observation is consistent with H2b and the profession’s private interests to protect itself and its members.

Other: Investigation Costs

Table 1 provides some evidence that, in addition to increased severity of punishment and greater likelihood of rehabilitation and monitoring, disciplinary committees incurred greater costs of investigation in the post-CPAB environment. The average cost of investigating a public code violation (in inflation-adjusted 2012 dollars) increased from $1089 to $24,470 in the post-CPAB environment and the average cost of investigating a private code violation increased from $428 to $3,019. This evidence suggests that, in the post-CPAB era, the profession is incurring significantly greater costs presumably because it is devoting greater effort when investigating offenses.

Summary

Overall, the mean analysis in Table 1 provides evidence in support of H1 indicating more severe punishment sanctions in the post-CPAB era. It also provides evidence that rehabilitation is increasing in the post-CPAB period, consistent with H3. Limited support is provided for the prediction in H4 of greater monitoring; SUPERVISION has increased for the overall sample post-CPAB and monitoring of offender’s future actions also has increased following private interest code violations. Lastly, the evidence indicates an increase in internal reporting consistent with H2b.

Multivariate Analysis

Punishment Severity (H1)

Although the univariate means analysis reported in Table 1 provides evidence consistent with the hypotheses, we conducted multivariate analysis to provide robust tests that control for important factors identified in previous research as influencing professional discipline decisions, such as degree of public interest, violation severity, and case certainty. We estimate Eq. (1) using an ordered logit for SEVERITY, ordinary least squares for DOLLARS_OF_FINE and MONTHS_OF_SUSPENSION, and logistical regression for each of CPE_CLASS, SUPERVISION, and FUTURE_ACTION, each with robust standard errors clustered by year. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the data used in these analyses, which includes all ICAO disciplinary cases in the sample period. Table 3 presents, by year, the three measures of SEVERITY used to test H1. These data suggest an increase in severity in the years following CPAB’s introduction in 2003 and, importantly, do not provide evidence of a linear increase over the entire sample period suggesting that the post-CPAB increase in SEVERITY is not part of a longer term continuous trend. Figure 1, which charts the mean measure of SEVERITY in each year, shows that the pre-CPAB period trends slightly downward, whereas the post-CPAB period trends upward. Although these data are indicative of a change following the establishment of CPAB, Table 3 and Fig. 1 do not control for factors such as degree of public interest, violation severity, and case certainty, so multivariate analysis is warranted.

Column (1) of Table 4 reports results from estimating Eq. (1) using Bédard’s (2001) punishment severity index, modified to include the threat of future suspension. This column provides evidence consistent with H1; the coefficient on POST_CPAB is positive (5.135) and statistically significant at a 1 % level using a two-tailed test. This evidence suggests that the post-CPAB era is associated with increasingly severe punishment. Following Bédard (2001), we estimate two alternative measures of punishment severity, DOLLARS_OF_FINE and MONTHS_OF_SUSPENSION in Columns (3) and (5) respectively. Again the coefficients on POST_CPAB for models with these two alternative measures are positive and significant at 10 and 1 % levels of significance, respectively, using two-tailed tests. On average, offenders are given a $864 larger fine and 1.4 more months of suspension in the POST_CPAB environment, after controlling for the public/private nature of the code violation, the existence of multiple violations, and whether the offender pleaded guilty.Footnote 16 Table 5 provides an alternative specification controlling for public interest using a continuous measure as opposed to the trichotomous measure used in Table 4. The results are substantively similar across columns (1), (3), and (5) as the coefficients on POST_CPAB are positive and statistically significant at 1, 10, and 1 % levels, respectively. The coefficients in column (3) and Column (5) of Table 5 suggest slightly higher point estimates where, on average, offenders are given a $961 larger fine and 1.5 more months of suspension in the POST_CPAB environment, after controlling for the public/private nature of the code violation, the existence of multiple violations, and whether the offender pleaded guilty. Together with the univariate results in Table 1 and Fig. 1, the multivariate results across Columns (1), (3), and (5) of Tables 4 and 5 provide evidence that punishment severity has increased in the post-CPAB era, consistent with H1.Footnote 17

Increasing Punishment Severity in Private Versus Public Code Violations (H2a)

The test of H2a, estimated by Eq. (2), is reported in Columns (2), (4), and (6) of Table 4. The hypothesis predicts that the increase in punishment severity in the post-CPAB period will be greater for private interest code violations than public interest code violations. We therefore expect the coefficient on the interaction between POST_CPAB and PUBLIC_TRI to be negative and statistically significant. The results in Columns (2), (4), and (6) show that the coefficient is not different from zero at a statistically significantly level in any of the specifications, failing to support H2a.

We measure public interest using an alternative specification in Table 5 as a continuous measure rather than the trichotomous measure used in our main specification in Table 4. The results are substantially similar across the specifications in Columns (2), (4), and (6) corroborating the results of Table 4 showing no support for H2a. Although the multivariate evidence for punishment severity is not consistent with the theory suggested by Parker (1994), these findings are consistent with the empirical results of Fisher et al. (2001) who find no evidence in their direct tests of Parker’s theory.Footnote 18

Reporting of Discipline Sanctions (H2b)

Building on Bédard’s (2001) finding that Parker’s theory may manifest itself differently across different stages of the discipline process, H2b investigates whether Parker’s theory of private interest may manifest itself in the decision of how to disclose the outcome of the discipline process. Table 6 provides the results of estimating Eq. (3). Column (1) reports the results of estimating Eq. (3) using a logistical regression with PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY as the dependent measure. The coefficient on POST_CPAB (0.232) indicates that there was not a statistically significant increase in the use of external publishing for disclosing the outcomes of the discipline process. The coefficient on PUBLIC_TRI (1.069) is positive and statistically significant at a 1 % level, suggesting that when the infraction involves a public code violation the discipline committee is more likely to disclose the outcome through external sources.

Column (2) of Table 6 reports the results of estimating Eq. (3) using a logistical regression with PUBLISHED_INTERNALLY as the dependent measure. The results suggest that there was a statistically significant increase in the use of communicating discipline outcomes internally post-CPAB as the coefficient on POST_CPAB was positive (5.35) and statistically significant at a 1 % level. Using simultaneous estimation to test for a difference in the POST_CPAB coefficient across the two specifications in Columns (1) and (2), we find a Chi-Squared of 55.46 resulting in a difference in the coefficients that is statistically significant at a 1 % level. These results are consistent with H2b and Parker’s theory of private interest manifesting itself in the discipline committees’ decisions of how to disclose the results of the disciplinary outcomes. Specifically, the evidence suggests that the profession protects its self-interest by reporting more disciplinary outcomes internally in the post-CPAB environment than in the pre-CPAB environment relative to the use of external forms of disclosure.

Increasing use of Rehabilitation and Monitoring Post-CPAB (H3 and H4)

Column (1) of Table 7 presents the results of testing H3’s assertion of an increased use of rehabilitation as a course of action by the disciplinary committee post-CPAB by estimating Eq. (1) using a logistical regression with CPE_CLASS as the dependent measure.Footnote 19 The coefficient on POST_CPAB is positive (13.716) and statistically significant at a 1 % level suggesting that the discipline committee was more likely to attempt to rehabilitate the offender through retraining in the post-CPAB era than the pre-CPAB era. The coefficient on PUBLIC_TRI is positive (0.981) and statistically significant at a 1 % level suggesting that the discipline committee was more likely to recommend rehabilitation when the violation was more public in nature. Table 8 provides the results of estimating Eq. (1) using an alternative continuous measure of public interest (PUBLIC_PERCENTAGE). The results in Table 8 are consistent with the evidence in Table 7 suggesting the results are robust to alternative measures of public interest. Collectively, these multivariate results are consistent with the univariate results in Table 1 and support H3.

To explore whether the increase in likelihood of recommending CPE classes post-CPAB differs between public and private code violations, Column (2) of Table 7 (Table 8) reports the interaction between PUBLIC_TRI (PUBLIC_PERCENTAGE) and POST_CPAB. This interaction was not statistically different from zero at conventional levels of significance, suggesting that the likelihood of recommending CPE classes does not differ between public and private code violations.

H4 test results are reported in Columns (3) and (5) of Table 7, based on estimating Eq. (1) using logistic regression with SUPERVISION and FUTURE_ACTION as dependent measures, respectively. The results are consistent with H4 as the coefficient on POST_CPAB is 12.518 and 8.741 when estimated using SUPERVISION and FUTURE_ACTION, respectively, both are statistically significant at a 1 % level. Interestingly, when the violation is more public in nature there is an increased likelihood of requiring future supervision but a decreased likelihood of requiring the firm to take other future actions, as the coefficient on PUBLIC_TRI is 0.847 for SUPERVISION and −4.417 for FUTURE_ACTION, significant at a 10 and 5 % level of significance, respectively. This result suggests that discipline committees favor future supervision for cases involving public code violations but require other future actions for cases involving private code violations. The results in Table 8 using the alternative continuous measure of public interest (PUBLIC_PERCENTAGE) are consistent with the findings of Table 7.Footnote 20 Collectively, the results provide support for H4 suggesting that discipline committees are more likely to recommend additional monitoring in the post-CPAB era.

Additional Exploratory Analysis

The evidence from Tables 1, 3, and 4 indicates that discipline committees adopted a variety of sanctions, including punishment, public reporting, rehabilitation, and monitoring. To our knowledge, prior research has not examined the effectiveness of these different sanctions in restoring members to good standing. To provide preliminary evidence of the role of sanction types on offender outcomes, we estimate the following equation:

where

- GOOD STANDING :

-

Equal to 1 if the disciplinary case presents a postscript indicating the offender later returned to being a member in good standing; 0 otherwise

- PUNISHMENT :

-

Bédard (2001)’s original sanction level, where reprimand = 1, fine = 2, temporary suspension = 3, and indefinite suspension = 4.Footnote 21

- THREAT_OF_PUNISHMENT :

-

Equal to 1 if the respondent receives either a threat of suspension or threat of expulsion; 0 otherwise

- REHABILITATION :

-

Equal to 1 if the member is required to take CPE courses; 0 otherwise

- MONITORING :

-

Equal to 1 if the member is required to be reinvestigated in the future, supervised in the future, or required to take other future actions; 0 otherwise

- PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY :

-

Equal to 1 if the order is published for the public in newspapers and other external avenues; 0 otherwise.Footnote 22

X represents a vector of control variables including

- PUBLIC_TRI :

-

Equal to 0 if all violations were identified as private interest code violations, 1 if the case involved both private and public code violations, and 2 if all violations were identified as public interest code violations

VIOLATION SEVERITY Measured as one of

- MULTIPLE_VIOLATIONS :

-

Equal to 1 if the action involved more than one violation; 0 otherwise

- VIOLATIONS :

-

The total number of violations identified in the action against the member

- LOG (VIOLATIONS):

-

The natural logarithm of 1 + total number of violations identified in the action against the member

- GUILTY_PLEA :

-

Equal to 1 if the member pleaded guilty and accepted full responsibility for the violation; 0 otherwise

- VIOLATION-TYPE :

-

A series of indicators variable by code number of violation

For a subset of observations (97 cases), the description included a follow-up section that described the outcome at a later period. Of these cases, 53 % resulted in the offender being described as returning to being a member in good standing. We use this sample to estimate Eq. (4).

The results of estimating Eq. (4) are presented in Tables 9 and 10. These results suggest that the severity of punishment and rehabilitation are positively related to a member returning to good standing. Importantly, THREAT OF PUNISHMENT does not have a statistically significant effect on the return to good standing; this finding may be notable for discipline committees because this form of sanction has become more common in the post-CPAB era (as shown in Table 1). Lastly, the coefficient on PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY is negative and statistically significant at a 1 % level using a two-tailed test across all specifications. This suggests that external publication may be an impediment to a member returning to good standing after an offense.

Anticipating that the severity of the underlying offense is an important factor to control when trying to estimate the role of sanctions on a return to good standing, we estimate four specifications using alternative controls for VIOLATION_SEVERITY. In addition to PUBLIC_TRI and PUBLIC_PERCENTAGE used in Table 9 and Table 10, respectively, which controls for a qualitative aspect of the offense, we include an indicator variable representing whether the case involves more than one violation, the total number of violations, the natural logarithm of the number of violations, and indicator variables for types of violations to provide a within–violation type analysis.Footnote 23 The results described above hold across the specifications in Table 9 and specifications in Table 10.

The results of these additional exploratory analyses should be used with caution because they are subject to some important limitations. First, the analyses use only a subset of sample cases, so they may not represent the overall sample. Although we verified that no offender’s name appeared in subsequent disciplinary cases, we do not know the regularity and diligence with which postscript updates are added to each case file. The possibility exists that updates of successful remediation are more often reported for cases involving severe punishment and rehabilitation.

Summary and Discussion

This study examined changes in disciplinary sanctions for Canadian accounting professionals over a 30-year sample period. We focused on changes arising during the period of increased public scrutiny of accounting professionals, marked by the 2003 introduction of the Canadian Public Accountability Board (CPAB), because it provided an opportunity to test Parker’s (1994) model of private interest professional accounting ethics. Parker’s model predicted that the accounting profession would respond with greater enforcement of ethical practices when faced with threats to self-regulation, such as those posed by the introduction of the CPAB. According to Parker’s (1994) model and Bédard’s (2001) empirical findings, these responses will be particularly evident in violations of professional conduct codes that relate to the private interests of the accounting profession and its members more so than those that relate to public interests.

Our examination of a hand-collected sample of 403 disciplinary cases heard by the largest society of Chartered Accountants in Canada led to several important observations. First, we noted that disciplinary punishments and threats of even more severe punishments were greater in the post-CPAB era than in the pre-CPAB era. These punishments tended to be financial in nature, resulting in more frequent fines, of greater (constant dollar) amounts, and with added charges that would allow the profession to recover costs of investigating the misconduct. We found that this increase in punishments was not more severe for violations of private interest codes than public interest codes, contrary to Parker’s private interest theory but consistent with Fisher et al.’s (2001) empirical results. However, support for Parker’s private interest theory was evident in the reporting decisions of the profession’s disciplinary committees; disciplinary actions and outcomes were more likely in the post-CPAB era than in the pre-CPAB era to be reported in publications and outlets aimed internally within the profession. Reporting in externally targeted communications, such as newspapers, did not increase with greater public scrutiny during the post-CPAB era.

We contributed to the literature on professional accounting ethics by examining disciplinary outcomes not previously studied. These new measures revealed greater propensity in the post-CPAB era to recommend rehabilitation through continuing professional education for offenders of conduct codes aimed at protecting public interests. Violations of private interest codes were met more frequently in the post-CPAB era with additional subsequent monitoring by professional conduct committees. That the profession has been increasingly using rehabilitation tactics to protect the public interest versus monitoring sanctions to protect the accounting profession’s private interest is a question to explore in future research. Another contribution from incorporating these new disciplinary sanctions is that we were able to conduct exploratory analyses that began to address previously unanswered questions about the relative effectiveness of various disciplinary sanctions. Using a subset of discipline cases that commented on whether offenders later returned to being members in good standing, we found that both punishment and rehabilitation sanctions were effective. In contrast, although the threat of severe punishment for repeated violation is more common in the post-CPAB era, the exploratory analyses suggest it is ineffective in influencing disciplinary outcomes and external reporting may actually impede a return of the member to good standing.

Our findings are subject to several limitations that provide directions for future research. First, we examine the disciplinary practices of one regional institute of professional accountants in Canada. As Bédard (2001) has discussed, these findings may not generalize to other regions or countries. For example, accountability boards across countries have impacted the accounting profession in different ways (Baker et al. 2014) which may impact the generalizability of these findings. Future research should examine a broader sample than we have considered in this study. Second, our sample includes accountants engaged in public practice as well as those working in industry. Future research should explore disciplinary actions of a broader group of practicing accountants. The recent unification of the accounting profession in Canada provides an ideal opportunity to examine whether punishment, remediation, and monitoring are similarly prevalent in and effective with this more diverse group. Finally, the design of this study prevents us from making causal claims. Our contention is not that CPAB caused changes in disciplinary sanctions. Rather, the threat to self-regulation from public outcry and operating through greater regulatory scrutiny is likely to have been felt by members of disciplinary committees and reflected in their sanctions. We encourage research into these and other potential factors that influence the actions of committees responsible for maintaining accounting professionalism in the post-CPAB era.

Notes

We focus on the ICAO because, for the period of our study, it was the largest provincial Chartered Accountant institute in Canada. Prior to the unification of the three accounting bodies in Canada, ICAO had 38,278 members (ICAO 2014); the next largest provincial society was the Ordre des Comptables agréés du Québec at 18,477 members (Ordre 2012). Differences in the disciplinary processes among provinces, particularly between Ontario and Québec (Bédard 2001), complicate sample expansion to other jurisdictions. Further, with the country’s major stock exchanges and regulators based in Ontario, we anticipated that the greatest public scrutiny would be felt in Ontario, thereby increasing our ability to detect the profession’s responses to such increased public scrutiny. We encourage future research that extends the current study to other Canadian (and foreign) jurisdictions.

See Jamal and Bowie (1995) for comparable categorization of codes of conduct from a theoretical level.

At the same time CPAB was being established, the Ontario accountancy profession also was undergoing change. On December 5, 2002, the Ontario Legislature unanimously passed the Justice Statute Law Amendment Act, 2002, which proposed to reconstitute the Public Accountants Council (PAC) and give each of the three accounting bodies in Ontario (CAs, CGAs, and CMAs) the authority to issue public accounting licenses directly to their own qualified members. However, the 2002 Act stopped short of specifying the standard of practice that would be expected of public accountants. This uncertainty was clarified on August 29, 2003, when the Ontario government announced the PAC would adopt the CA profession’s standards for qualification and enforcement of its rules of professional conduct (ICAO 2003).

The impact of an accountability board such as CPAB is felt not only by auditors. This broader impact is evident in CPAB’s mandate to improve financial reporting integrity by also engaging those charged with governance, regulators, and standard setters. Viewed through Parker’s (1994) private interest theoretical model of professional accounting ethics, establishment of an accountability board signals an external threat to self-regulation that undermines the authority of the accounting profession.

This is especially pertinent in the Canadian context given CPAB’s strategic emphasis on “judicious transparency” (CPAB 2012, p. 9).

In contrast to H2a and H2b, we only specify main effects for H3 and H4 given the lack of theory permitting higher order effect predictions pertaining to rehabilitation and monitoring.

For tabulated results, 2003 is included in the pre-CPAB period. To determine the sensitivity to this grouping, all analyses were re-run after excluding data from 2003. The statistical significances of these sensitivity analyses are unchanged from the tabulated univariate and multivariate tests of hypotheses. As an even more conservative test, we also re-ran univariate and multivariate analyses after excluding data from 2002 through 2004. The results of these more conservative tests were materially similar to those tabulated; the few instances of statistical significance loss that arise only for selected punishment measures are presented in footnotes 17 and 18.

All dollars are adjusted for inflation and are presented using a common base of 2012 dollars.

We also provide results using an alternative continuous measure of public interest PUBLIC_PERCENTAGE.

In subsequent untabulated analyses, we replace the indicator variable MULTIPLE_VIOLATION with the continuous measure VIOLATION (the number of violations in the case); results were substantively similar.

Unlike Eq. ( 2 ), Eq. ( 3 ) does not include Year controls because PUBLISHED_INTERNALLY and PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY are not evenly distributed across years. Estimation of the Logistical Regression with Year dummies results in a reduction of sample for each specification, leaving a resulting sample of 337 observations for the estimation of PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY and 108 observations for PUBLISHED_INTERNALLY. Despite this reduction in sample size, when we run our analysis including Year dummies, we find substantively similar results. With these reduced samples we continue to find a coefficient (18.91) on POST_CPAB when estimating INTERNALLY_PUBLISHED that is statistically significant at a 1 % level and statistically larger than the coefficient on PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY at a 5 % level of statistical significance.

H2a and H2b require multivariate analysis so they are addressed in the “Multivariate Analysis” section that follows.

Because subsequent analyses compare private versus public interest code violations where the offender has committed only one violation, we restrict the initial tabulation in Table 1 to this same subsample. This restriction resulted in a loss of 46 % of the sample. To offset this loss of power and also recognize that hypotheses are directional, we report statistical significance in Table 1 using one-tailed tests. All other tables report two-tailed tests.

The $864 represents 2012 dollars, as all dollars are adjusted for inflation to a common base.

As indicated in footnote 9, all analyses were re-run after excluding data from 2003 and from 2002 through 2004. The statistical significances of all results reported in Tables 4 and 5 remain unchanged when excluding only 2003 data. When excluding the 53 observations (13 % of the sample) from 2002 to 2004 data, all results reported remain unchanged with the exception that the coefficient on POST_CPAB reported in column (3) of Tables 4 and 5 is no longer positive and statistically significant at conventional levels.

In additional analyses, the statistical significances of all results reported in columns (2), (4), and (6) of Tables 4 and 5 remain unchanged when excluding only 2003 data. When excluding the 53 observations (13 % of the sample) from 2002 to 2004 data, the results remain unchanged with the exception that the coefficients on PUBLIC_TRI in Table 4 and PUBLIC_PERCENTAGE in Table 5 are no longer statistically significant in column (6).

Note that there is a reduction of the sample from the total sample of 403 observations because CPE_CLASS is not evenly distributed across years and estimation of the Logistical Regression with Year dummies results in a reduction of sample to 371 observations as some years cannot be estimated. When we remove the year dummies and estimate the model on the entire sample of 403 observations the results are substantively similar. The coefficient on POST_CPAB is 0.55 and statistically significant at a 5 % level.

Untabulated multivariate analysis also finds that, consistent with the shifts in SUPERVISION and FUTURE_ACTION, the likelihood of receiving a REINVESTIGATION sanction increases in the post-CPAB era.

Bédard (2001)’s sanction measure is used rather than SEVERITY as we wanted to measure the role of threats as a separate sanction and SEVERITY encompasses THREAT_OF_PUNISHMENT. When we run the analysis replacing PUNISHMENT wtih SEVERITY and omitting THREAT_OF_PUNISHMENT, the results are substantively similar.

Within the restricted sample of 97 cases there were no observations of PUBLISHED_INTERNALLY, therefore transparency was limited to only PUBLISHED_EXTERNALLY actions.

The number of observations in the within-violation type analysis in Column (4) drops to 66 because there must be more than one case within violation type to perform the analysis.

References

Alam, A., Khan, J., Liu, J., Klemensberg, J., Griesman, J., & Bell, C. M. (2013). Characteristics and rates of disciplinary findings amongst anesthesiologists by professional colleges in Canada. Canadian Journal of Anesthesiology, 60, 1013–1019.

Anantharaman, D. (2012). Comparing self-regulation and statutory regulation: Evidence from the accounting profession. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37, 55–77.

Badawi, I. M. (2002). Accounting codes of conduct, violations and disciplinary actions. Review of Business, 23(1), 72–76.

Baker, C. R., Bédard, J., & Prat dit Hauret, C. (2014). The regulation of statutory auditing: An institutional theory approach. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(5), 371–394.

Bédard, J. (2001). The disciplinary process of the accounting profession: Protecting the public or the profession? The Québec experience. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 20, 399–437.

Beets, S. D., & Killough, L. N. (1990). The effectiveness of a complaint-based ethics enforcement system: Evidence from the accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(2), 115–126.

Ben-Ishai, S. (2008). Sarbanes-Oxley five years later: A Canadian perspective. Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, 39(3), 469–491.

Brooks, L. J. (1989). Ethical codes of conduct: Deficient in guidance for the Canadian accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 8(5), 325–335.

Canadian Public Accountability Board (CPAB). (2012). 2013–2015 strategic plan: Meeting the regulatory challenge in a global environment. Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.cpab-ccrc.ca/Documents/About/CPAB%20_Strategic_Plan_2013_2015_EN_FNL.pdf.

Canadian Securities Administrators. (2014). National Instrument 52–108 Auditor Oversight. Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category5/rule_20041009_52-108-aud-oversight.pdf.

Canning, M., & O’Dwyer, B. (2001). Professional accounting bodies’ disciplinary procedures: Accountable, transparent and in the public interest? The European Accounting Review, 10(4), 725–749.

Canning, M., & O’Dwyer, B. (2003). A critique of the descriptive power of the private interest model of professional accounting ethics: An examination over time in the Irish context. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 16(2), 159–185.

Cohen, J. R., & Pant, L. W. (1991). Beyond bean counting: Establishing high ethical standards in the public accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(1), 45–56.

DeFond, M. L. (2010). How should the auditors be audited? Comparing the PCAOB inspections with the AICPA peer reviews. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 49, 104–108.

Fisher, J., Gunz, S., & McCutcheon, J. (2001). Private/public interest and the enforcement of a code of professional conduct. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(3), 191–207.

Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Higgs-Kleyn, D., & Kapelianis, D. (1999). The role of professional codes in regulating ethical conduct. Journal of Business Ethics, 19(4), 363–374.

Hilary, G., & Lennox, C. (2005). The credibility of self-regulation: Evidence from the accounting profession’s peer review program. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40, 211–229.

Institute of Chartered Accountants of Ontario (ICAO). (2003). CAs back Ontario commitment to highest public accounting standards. August 29, 2003. Retrieved February 4, 2015, from http://www.icao.on.ca/MediaRoom/MediaReleases/2004mReleases/1009page1462.aspx.

Institute of Chartered Accountants of Ontario (ICAO). (2014). Annual Report 2014. Toronto, ON: ICAO.

Jamal, K., & Bowie, N. W. (1995). Theoretical considerations for a meaningful code of professional ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 14(9), 703–714.

Lennox, C., & Pittman, J. (2010). Auditing the auditors: Evidence on the recent reforms to the external monitoring of audit firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 49, 84–103.

Loeb, S. E. (1972). Enforcement of the code of ethics: A survey. The Accounting Review, 47(1), 1–10.

Mitchell, A., Puxty, T., Sikka, P., & Willmott, H. (1994). Ethical statements as smokescreens for sectional interests: The case of the UK accountancy profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(1), 39–51.

Moriarity, S. (2000). Trends in ethical sanctions within the accounting profession. Accounting Horizons, 14(4), 427–439.

Neu, D., & Saleem, L. (1996). The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Ontario (ICAO) and the emergence of ethical codes. The Accounting Historians Journal, 23(2), 35–68.

O’Dwyer, B., & Canning, M. (2008). On professional accounting body complaints procedures: Confronting professional authority and professional insulation within the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Ireland (ICAI). Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(5), 645–670.

Ordre des Comptables Agréés du Québec. (2012). Together in Excellence: 2011–2012 Annual Report. Montreal, QC: Ordre.

Pande, V., & Maas, W. (2013). Physician medicare fraud: Characteristics and consequences. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 7(1), 8–33.

Parker, L. D. (1987). An historical analysis of ethical pronouncements and debate in the Australian accounting profession. Abacus, 23(2), 122–140.

Parker, L. D. (1994). Professional accounting body ethics: In search of the private interest. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(6), 507–525.

Peytcheva, M., & Warren, D. E. (2013). How auditors perceive sanction severity and the detection of violations: Insights into professional vulnerabilities. Accounting and the Public Interest, 13, 1–13.

Preston, A. M., Cooper, D. J., Scarbrough, D. P., & Chilton, R. C. (1995). Changes in the code of ethics of the U.S. accounting profession, 1917 and 1988: The continual quest for legitimation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(6), 507–546.

Quick, R., & Warming-Rasmussen, B. (2002). Disciplinary observance and sanctions on German and Danish auditors. International Journal of Auditing, 6, 133–153.

Robinson, G. (2008). Late-modern rehabilitation. Punishment & Society, 10(4), 429–445.

Schaefer, J., & Welker, R. B. (1994). Distinguishing characteristics of certified public accountants disciplined for unprofessional behavior. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 13, 97–119.

Strong, D. E. (2011). Access to enforcement and disciplinary data: Information practices of state health professional regulatory boards of dentistry, medicine and nursing. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 33(4), 534–570.

Ugrin, J. C., & Odom, M. D. (2010). Exploring Sarbanes-Oxley’s effect on attitudes, perceptions of norms, and intentions to commit financial statement fraud from a general deterrence perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 29, 439–458.

US House of Representatives. (2002). The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Public Law 107-204 [H.R. 3763] (Vol. 3763). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Acknowledgments