Abstract

Businesses have long been admonished for being unduly focused on the pursuit of profit. However, there are some organizations whose purpose is not exclusively economic to the extent that they seek to constitute common good. Building on Christian ethics as a starting point, our article shows how the pursuit of the common good of the firm can serve as a guide for humanistic management. It provides two principles that humanistic management can attempt to implement: first, that community good is a condition for the realization of personal good, and second, that community good can only be promoted if it is oriented towards personal good. To better understand which community good can favor personal good and how it can be achieved, we examine two recent humanistic movements—Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion—that strive to participate in the common good. From the analysis of these two movements, we identify a shared managerial willingness to adopt the two principles. Moreover, we also reveal that Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion present different ways of linking community good and personal good, and therefore, different means exist for firms to participate in the common good.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Business organizations have often been accused of excessive and uncompromised focus on the pursuit of profit and obscuring the social and spiritual dimensions of their members who seek to participate in a community and give meaning to their actions (Sandelands 2009). Yet there are some organizations and movements whose purpose is not exclusively economic (Abela 2001; Argandona 1998; O’Brien 2009; Sison 2007). Such organizations and movements might be associated with terms including social business, Conscious Capitalism, Economy of Communion, value-based organizations, liberation or transformational management, and so on. Unsurprisingly, these organizations and movements have very different orientations related to their values and history, with part of the reason why their leaders expand the focus beyond a purely utility-driven approach being a common humanistic desire to place the dignity of the individual above all other values.

Such organizations and movements do not only pursue a common interest, that could justify the sacrifice of the inalienable rights of individuals (Melé 2009, p. 235), or at least, could lead in taking measures for the survival of the company, even if the fundamental purpose of the business or its organizational conditions did not conform to the common good. They also endeavor to generate a common good that is not exclusively economic. Based on the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition and Catholic Social Thought (CST), the concept of common good is defined as “the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily” (Pontifical Commission of Justice and Peace 2004, para 164). The ethics literature adopts similar definitions of common good as a set of conditions, economic, social, moral and spiritual, that favors personal fulfillment. For instance, Messner defines the common good as “that order of society in which every member enjoys the possibility of realizing his true self by participating in the effects of the cooperation of all” (Messner 1965, p. 124). According to Finnis (1986, p. 165), the common good includes “such an ensemble of conditions which enhance the opportunity of flourishing for all members of a community.” Thus, regardless of the definition used, the concept of common good proposes a subtle interaction between community good and personal good.

Focusing specifically on organizations, Sison and Fontrodona (2012, 2013) use the notion of the common good of the firm to evoke this particular relationship between community good and personal good. When referring to the firm, common good is “intrinsic, social and practical” (Sison and Fontrodona 2013, p. 612), and these scholars define the common good of the firm as collaborative work (Sison and Fontrodona 2013, p. 614). Our article is based on this first theoretical concept, the common good of the firm, whereby humanistic firms seek to participate in community good since it allows each individual to also fully accomplish their personal good.

We also draw on a second theoretical concept, that of humanistic management (Acevedo 2012; Cortright and Naughton 2002; Melé 2003, 2009; Melé and Schlag 2015; Schlag 2012; Sison 2007; Spitzeck 2011), that is based on the same premise that humanistic firms pursue a continuous and permanent interaction between community development and personal development. Melé (2003) defines humanistic management “as a management that emphasizes the human condition and is oriented to the development of human virtue, in all its forms, to its fullest extent” (p. 79).

This article concurs with Sison and Fontrodona’s (2013) suggestion that research should show that the common good of the firm is not only an appealing idea but also a feasible and practical reality. Therefore, we seek to demonstrate how “an operational managerial paradigm (can) be designed based on the new anthropological, political, economic and ethical premises that the common good supplies” (Sison and Fontrodona 2012, p. 241). While this recommendation is challenging given the recognized difficulty in making common good a concrete principle for action (see Deissenberg and Alvarez 2002; De Bettignies and Lépineux 2009), we nonetheless consider it meritorious and worthy of investigation.

The research question informing this study is how can the common good of the firm serve as a guide for humanistic management? To help address this, we focus on two recent humanistic movements—Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion—to more clearly delineate how the common good of the firm can be implemented in practice. These two movements have been selected because they both try to contribute to the common good on various levels including economically, socially, morally, and spiritually. Our contribution is therefore to provide, firstly, some clear guidance to business leaders seeking to enact the notion of the common good in their firms, and secondly, to show that different pathways of implementing the common good are inherently plausible.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: The next section considers how the pursuit of the common good of the firm encourages managers to reflect on the question of the proximity and the interaction between community good and personal good. We then observe that the 2013 apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis entitled Evangelii Gaudium can assist business managers by giving them relevant managerial principles. To examine how humanistic management can in practice link community good and personal good, the following sections draw on the existing empirical and conceptual analyses of two humanistic movements—Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion—which seek to contribute to the common good in all its dimensions. We contend that humanistic management is necessarily confronted by the question of choosing the nature of the interaction between community good and personal good. We endeavor to better understand why the two different movements pursuing the common good provide a different response to this question. We conclude by identifying the implications of our study and some additional areas of future research.

Common Good of the Firm: Proximity and Interaction Between Community Good and Personal Good

Since the common good of the firm can guide managerial action by suggesting a judicious link between community good and personal good, we present in turn an analysis of the proximity and the interaction between these two concepts.

Proximity between Community Good and Personal Good

The common good of the firm is rooted in a personalist approach in which the individual cannot find fulfillment uniquely in him- or herself, and without regard to his being “with” and “for” others (Pontifical Commission of Justice and Peace 2004, para 165). In other words, it is based on the assumption that the flourishing of the community can also enhance the well-being of the individuals in that community (O’Brien 2009). The personalist approach is strongly supported by Mounier (1970). This philosopher denounces the rules of impersonality whereby the world of “he” is one of individualism, and the world of “one” is characterized by indifference, anonymity, lack of ideas, and opinions. In the realm of impersonality, there are no fellow human beings but only interchangeable individuals, who are centered only on themselves. The person is in fact both a center of initiatives and of freedom, and a decentralized being oriented towards other persons. Therefore, Mounier’s framework considers the collective context in which the person has to build him- or herself. All human phenomena are primarily collective. It is not that the “we” is the only object of analysis for the philosopher; rather, the “I” and the “you” described by Buber (1937) are capable of meeting in dialogue and communication. Together, they form the “we,” which is the community.

According to personalism, all existence is co-existence which means people exist fundamentally alongside and with others. The human being can find fulfillment not in the development of a “having for him- or herself,” but in the pursuit of a community good. Rooted in this anthropological reality, the common good of the firm involves active search for community good and personal good. These two concepts are not only close in proximity to each other, but they also interact as the following section illustrates.

Interaction Between Community Good and Personal Good

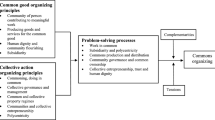

Based on the common good which is defined as a set of conditions allowing groups and individuals to reach fulfillment, the concept of the common good of the firm refers to the following two linkages between community good and personal good: (i) community good is a condition for the realization of personal good and (ii) community good can only be promoted if it favors personal good.

With regard to the first link—that community good is a condition for the realization of personal good—we refer to the work of Thomas Aquinas and Simone Weil. Both of these Christian philosophers have made the association between community good and personal good without opposing or separating them. Aquinas in the thirteenth century, and a follower of Aristotle’s ethics, highlighted how the production of goods and services ensuring the subsistence of human beings and of the societies in which they live helps “to remove idleness, to curb concupiscence and to help the poor” (Aquinas 1947, question 187, article 3). From producing goods and services that was previously considered an act of servitude, Aquinas moves towards visioning work as a source of freedom, since people free themselves from certain desires or learn to defer their accomplishments. In the early twentieth century, Weil, in her book entitled Gravity and Grace published only in 1952, emphasized that producing and distributing valued goods and services (through organizations) is a special opportunity for human beings to meet societal needs and thus constitutes a place of spiritual fulfillment (Weil 1952a). In Needs for Roots, also published in English in 1952, Weil explicitly establishes the link between community good and personal good by explaining that the human being can benefit from personal development and can even claim a properly human life if he or she is rooted in a community that pursues the common good (Weil 1952b). For Weil, as for Aquinas, the search for community good is the means of achieving personal good.

For the second link—that community good can only be promoted if it is oriented towards personal good—we again make the reference to Sison and Fontrodona (2012) who described the personal good of the different members of the organization as “the opportunity to acquire and develop skills, virtues and meaning” (p. 239). Thus, the personal good of the different members of the firm is not restricted to the development of their skills. To avoid such a reductionist view of personal good, these scholars also refer to the development of meaning and virtues. This does not mean, however, that managers have to achieve an “ethical dressage” by stating a predefined meaning of work or by imposing virtues that are considered to be essential. It only means that the process of giving meaning (May et al. 2004), like the exercise of virtues (MacIntyre 1981), may be the result not of an isolated managerial decision but of a habitual personal state fostered by management. This is precisely the objective of humanistic management that not only considers employees as well as managers in terms of skills, but also primarily as persons seeking meaning and virtue.

Humanistic Management and Evangelii Gaudium

Humanistic management initiates a virtuous cycle based on recognizing the existential and the moral need to participate in the common good of the firm by choosing a community good which is a means of achieving personal good and which is also oriented towards personal good. How is it possible to favor a dynamic and positive relationship between community good and personal good? Which forms of community good favor personal good? We refer to the 2013 apostolic exhortation entitled Evangelii Gaudium for helpful insights. Specifically, this exhortation proposes four principles to help managers to make the right choice of community good and to usefully draw the link between community good and personal good:

-

the principle of long-term commitment (time is greater than space);

-

the totality principle (the whole is greater than the part);

-

the principle of unity (unity prevails over conflict); and

-

the principle of reality (realities are more important than ideas).

That time is greater than space (the principle of long-term commitment) means that long-term commitments are greater than short-term actions. This principle invites managers “to work slowly but surely, without being obsessed with immediate results” (Evangelii Gaudium 2013, para 223). It deserves to be analyzed in the light of the dialectic of ends and means; that profit, and capital or technological development are explicitly posed as instruments for human development (Pontifical Commission of Justice and Peace 2004, para 277). Therefore, economic and technological development are not considered as an evil or a lesser evil but can be rehabilitated as necessary instruments to serve a transcendent purpose—the development and flourishing of the human person.

Secondly, the claim that the whole is greater than the part (the totality principle) invites human communities “to broaden our horizons and see the greater good which will benefit us” (Evangelii Gaudium 2013, para 235). Barnes (1984) has previously underlined the superiority of the whole to the part. This means that “the common good of any community is embedded in the common good of larger community (so that) the common good of a business firm should be consistent with the common good of society” (Melé 2009, p. 235). Consequently, managers can become more aware of the plurality of the dimensions of the common good—economic, social and ethical—previously highlighted by Fessard (1944). These include the sharing of the good (public service, commons); the commonality of the common good (equality of access to common goods); and the good of the common good (nature and balance of the relationship between the individual and the community). In his analysis, Melé (2009) added the environmental dimension and therefore relied on four dimensions to define the common good: the economic conditions that allows everyone to enjoy a reasonable level of well-being; organizational conditions which permit respect for human freedom, justice, and solidarity; socio-cultural values shared in a community, including respect for human dignity and human rights in connection with personalism; and environmental conditions that aim to maintain appropriate living conditions for current and future generations (see Melé 2009, p. 236). The common good concept has, for this reason, evolved during recent economic and environmental crises. It not only covers a consideration of the inalienable rights of human beings, but it is now also defined by strong consideration for equity and social justice, and environmental issues.

Thirdly, the idea that unity prevails over conflict (the principle of unity) shows that it is important to confront conflicts and to overcome them: “Conflict cannot be ignored or concealed. It has to be faced” (Evangelii Gaudium 2013, para 226). The risk highlighted by much contemporary business literature is to ignore conflict or to exacerbate conflict by focusing on personal and interpersonal issues. Rather, humanistic management seeks to resolve difficulties by looking for a unified vision of the common good.

Finally, the notion that realities are more important than ideas (the principle of reality) refutes the numerous denials of reality. The danger lies in focusing on profit or perceived corporate image on behalf of a community necessity by concealing the actual personal situation of relevant stakeholders. Managers can avoid this denial of reality by adopting a realistic outlook on what human beings really do and by fostering a dialogue between realities and ideas: “There has to be continuous dialogue between the two, lest ideas become detached from realities” (Evangelii Gaudium 2013, para 231).

Thus, we contend that Catholic Social Thought (CST) provides useful guidance to humanistic managers encouraging them to develop a long-term, broad, unified, and realistic vision of the common good. In practice, how can humanistic management adhere to this view and identify more precisely the interaction between community good and personal good? At this point, we turn to analyze two specific and recent movements in which managers have attempted to improve their participation in the common good.

Two Humanistic Movements: Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion

Both Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion seem highly capable of constituting common good in that these movements aspire to pursue long-term, broad, unified, and realistic objectives for the benefit of all stakeholders.

Conscious Capitalism, cited by some as a major trend for many years to come (Aburdene 2005) and popularized by John Mackey, founder of Whole Foods Market, is based on the level of consciousness of individuals who adopt higher goals and choose wiser and more effective operational practices oriented towards stakeholders. Southwest Airlines, Google, Costco, Nordstrom, and UPS are among many of the well-known and high-profile companies that are managed by the principles of Conscious Capitalism. In academic terms, it was originally structured through the Conscious Capitalism Institute within Bentley University in Boston (but has now extended well beyond this in terms of global influence), and there is a growing literature in the area (e.g., Sisodia 2011; Sisodia et al. 2011; Mackey and Sisodia 2013). Conscious Capitalism acknowledges the role of the spiritual dimension in the organization but does not specify any explicit connection to any particular religion and retains a sufficiently vague vocabulary to cover all types of personal convictions. Not based on dogma or an act of faith, the spirituality of Conscious Capitalism is rather a spirituality of immanence—or a feeling of eternity—(Sisodia 2011), although some writers do refer to a spirituality of transcendence—or relationship with God (see Aburdene 2005). Whatever the underlying religious or spiritual convictions, Conscious Capitalism has four tenets encouraging workers to give meaning to their work: spirituality-evolved, self-effacing servant leaders; a conscious culture; a stakeholder orientation; and a higher purpose, or one that transcends profit maximization.

The second movement that is examined—Economy of Communion—emerged from the intuition of Chiara Lubich, founder of Focolare Movement Christian, when confronted with glaring contrasts between extreme poverty and great wealth in the city of Sao Paulo in Brazil (Bruni 2002; Bruni and Zamagni 2004; Gold 2004, 2010; Lubich 2001; Pelligra and Ferrucci 2004). With clear and explicit reference to Catholic spirituality and the notion of communion (Bruni and Uelmen 2006; Bruni and Smerilli 2009), this movement has the objective, through the sharing of profits and an ethical and responsible system, of participating in the common good. Firms or companies adhering to Economy of Communion can today be found in many countries and across diverse sectors. Survey research conducted in Italy in 2009 (see Baldarelli 2011) and an in-depth case study (Argiolas et al. 2010) reveal its characteristic features. The Economy of Communion site provides a thorough analysis of managerial practices on the basis of leaders’ testimonies, theses, research papers, and conferences.Footnote 1 Managerial practices are described in a document entitled “Guidelines to Running an Economy of Communion Business” (GECB 2011), which is both an attempt to express the initial project and a synthesis of many Economy of Communion entrepreneurs’ practices. A recent book from Gallagher and Buckeye (2014) also addresses the business practices of the Economy of Communion.

These two movements—Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion—are forms of private governance and are only possible in a market economy. Consequently, neither movement has the goal of being generalized through coercion, and they are only possible if they ensure the economic survival and development of the firm. They result from a shared desire to target forms of good other than exclusively economic ones, and both movements seem to pursue (i) community good as a condition for the realization of personal good and (ii) personal good as the objective of community good. These two objectives are examined in turn. We then explore some particular tensions between forms of community good that the two movements are confronted with and how these might be overcome.

Community Good as a Condition for the Realization of Personal Good

Conscious Capitalism leaders pursue long-term, broad, unified and realistic objectives by responding to real societal needs through the choice and the quality of their products and services, and by practicing philanthropy. To respond to the actual needs of society, these firms make deliberate and carefully thought choices about the higher purpose they set themselves. They strive though their main activity to behave like responsible citizens addressing some of the problems that communities are struggling with on a local, national, and global basis. To ensure the quality of products and services, Conscious Capitalism managers affirm their adherence to sobriety which consists of choosing suppliers by giving great importance to the criteria of quality and minimizing marketing and communication expenses (Sisodia 2011; Sisodia et al. 2011). The reduction in marketing and communication expenses calls for a refocusing of marketing on the service to customers. According to Mackey and Sisodia (2013, p. 82), great marketing is about improving customers’ well-being by understanding and satisfying their most important life-affirming needs. For this reason, the well-being of customers is treated as an end and not just a means to profits, and customers are more thought of as friends or guests than consumers or clients (Mackey and Sisodia 2013, pp. 76–77). Philanthropy is also used to achieve broad organizational objectives and constitutes a major component of conscious business. Most Conscious Capitalism firms have a policy of donating from between 5 to 10 percent of their profits to non-profit organizations.

These two higher purposes—a contribution to societal needs through the choice and the quality of goods and services, and philanthropy—are also central in the Economy of Communion movement, which gives particular consideration to the choice of products or services and the way they are delivered, not only to respect contractual obligations but also “to evaluate the effects of its products on the well-being of people and the environment to which they are destined” (GECB 2011, note 3). The managers and leaders of Economy of Communion businesses have a vision of being good by offering products that are truly good and services that truly serve (Gallagher and Buckeye 2014).

Economy of Communion also makes profit the instrument of a larger and more active solidarity. Firms subscribing to Economy of Communion commit themselves to solving social problems, not only through their business operations but also by the profits they generate. Indeed, business profits are used for three goals: financing the development of the business itself; spreading the culture of communion by means of media or conferences; and helping people in need and reducing poverty, most often those living in close proximity to the Economy of Communion organization. The aid to the most deprived people is used to fund, for example, education scholarships, housing developments, emergency assistance for families in difficulty, and collective projects promoted by the most deprived themselves (Gold 2004, 2010). Recipients are encouraged to find a way to make sure that monies allocated to them will also help others, sharing with people who are more deprived than them or giving work to people around them. The movement refers less to philanthropy than to a culture of sharing in which each person gives and receives in equal dignity. As Lubich (2007) explicitly observed, the Economy of Communion “is not based upon the philanthropy of a few, but rather upon sharing, where each one gives and receives with equal dignity in the context of a relationship of genuine reciprocity” (p. 277).

Personal Good as the Objective of Community Good

Management of Conscious Capitalism is aimed at increasing employees’ trust (Aburdene 2005; Sisodia et al. 2011, pp. 48–65, 75, 87). The way used to improve employees’ confidence is to help them give meaning to their work. To do so, in addition to a deliberate approach to compensation based on internal equity (Mackey and Sisodia 2013, p. 93; Sisodia et al. 2011, pp. 79–80, 83), participative and delegative practices, informal leadership (Neville 2008; Mackey and Sisodia 2013, p. 240), flexible working time arrangements, and a culture of conciliation (Sisodia et al. 2011, pp. 79–80), these humanistic organizations stimulate not only extrinsic motivation symbolized by the carrot-and-stick approach but also intrinsic motivation. This means “hiring talented and capable people who are also personally committed to the company’s purpose and their work” (Mackey and Sisodia 2013, p. 89).

For Economy of Communion, the objective is to develop management practices consistent with the values of communion, and tools called “instruments of communion” (Argiolas 2009). Economy of Communion takes up many human resource management (HRM) and general management practices existing in other humanistic economies such as participative styles of management, development of training, quality of work life, low wage differentials, attention to all relevant stakeholders, respect for the environment, and priority to safeguarding and, where possible, the creation of employment. But Economy of Communion also refers to a specific purpose, one that promotes friendship as a virtue (Bruni and Uelmen 2006, p. 668). The development of friendship within these firms is fostered by a culture of giving that makes work a gift to receive and to offer.

Overcoming Tensions Between Forms of Community Good

The two humanistic movements are confronted with tensions between the different forms of community good: a contribution to societal needs through the choice and the quality of goods and services, and philanthropy. Indeed, Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion both seek to respond to customers’ real needs and to aid other communities through a redistribution of profit (see also Byron 1988, pp. 526–527). Tensions may therefore arise when firms choose to respond to customers’ real needs (for example, sustainable quality of products and services, and rigorous selection of suppliers), since they could run the risk of having less profit to redistribute in the short term. In the long term, this tension may be more easily overcome in the sense that sobriety also implies a reduction in marketing and communication expenses and in staff turnover rates, leading to increased profit. If, in some cases, being too philanthropic would put the business firm at risk, our analysis of the two humanistic movements reveals a common conviction that intelligent corporate philanthropy can be beneficial to the corporation, its stakeholders, and wider society. Both movements propose one specific way of overcoming this tension: giving priority to the correct functioning of the firm and to its core activity (Mackey and Sisodia 2013, p. 125), or what the Economy of Communion refers to as the primacy of wealth creation over redistribution (Gallagher and Buckeye 2014, p. 186). The Economy of Communion business firms specifically involve its workers in community projects they can support and benefit from (Bruni and Uelmen 2006, pp. 653–657).

Discussion

The above analysis has demonstrated that there is no single humanistic managerial model, nor even a single way of expressing the common good of the firm. Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion adopt different ways of linking community good and personal good. We propose a number of explanations that helps account for this diversity in pathways towards the common good.

First, Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion concern structures of different sizes, cultures, and characteristics. Conscious Capitalism can be found mainly in pre-existing large organizations in which the leadership typically wishes to raise meaning, confidence and spiritual conscience among its members. Economy of Communion, on the other hand, tends to concern small structures, usually in the area of craft work or services, and whose leadership seeks to enhance the logic of gift in the context of business (for a discussion of gift, see Frémeaux and Michelson 2011).

Another part of the explanation in their difference lies in the choice of stakeholders. Argandona (1998) found it important “to consider what kind of social relations the company (and its internal members) maintain with the various internal and external stakeholders, in order to identify the common of the society thus defined, and the rights and duties that emanate from the common good” (p. 1099). Certainly, the two movements adopt the broadest conception of stakeholders: that they are any group or individual who may affect or be affected by the obtainment of the company’s goals (Freeman 1984, p. 25), stakeholders no longer with an interest in the company (Argandona 1998), and those who participate in the good. In other words, this approach by humanistic organizations is based less on an “economism-based business ethos” than on a “humanist business ethos, which tries to see business enterprises in their human wholeness” (Melé 2012, p. 90), which revolves around growing human communities. Thus, Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion consider shareholders, managers, employees, suppliers, customers, and competitors as relevant stakeholders. In these two movements, even competitors are thought of as allies in striving for a win–win relationship and mutual excellence (Gallagher and Buckeye 2014; Mackey and Sisodia 2013). However, some of the Economy of Communion organizations extend the firm’s responsibility to the most deprived members of society. We do not infer that the gift to competitors (mergers, acquisitions or other agreements) or the gift to the poor (sharing of profits and employment possibilities for disadvantaged persons) constitute duties for all firms that choose to participate in the common good, but they may be key components of the common good of the firm.

Table 1 synthesizes the main features of Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion. It does not reflect the diversity and inherent complexity of the actual economic and social situation of each organization, but it does underline the main trends that can be identified from extant literature, conferences, reports, and testimonies.

Therefore, by explicitly showing that there are alternative pathways of contributing to the common good, we also observe that humanistic management seeking common good is necessarily confronted with the question of identifying the exact interaction between community good and personal good. This inherent tension in seeking common good complements other tensions that affect all the firms.

Firstly, all business leaders can be divided between the model of a rational definition of objectives centered on productivity and efficiency, and the model of human relationships focused on the development of human resources and internal harmony (Abela 2001; Denison et al. 1995; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1981). Secondly, all firms may face the tensions that oppose ethics expressed by the founders and ethical standards that are implemented within the subscribing organizations. Fyke and Buzzanell (2013), for example, explain the phenomenon not only by a lack of awareness of ethical dilemmas but also by noting that ethical consciousness does not necessarily generate ethical behavior.

As we have contended, firms seeking the common good also confront tensions between the different forms of community good, responding to societal needs through the production of goods and services, and philanthropy. When firms are not capable of including all the relevant stakeholders, the priority might be to strengthen internal community dynamics that respond at the same time to the employees’ needs to be useful to society and to their need to fulfill themselves.

Conclusion

Our position is that the common good of the firm helps scholars and practitioners to think positively about the role of business in society. Whereas corporate social responsibility (CSR) might lead us to consider the social and environmental indicators as moderators of an economic logic, the common good of the firm integrates this economic logic more easily since it attributes an instrumental function to it. Avoiding the dominant anthropological inversion that profit is the purpose and restoring human development is the goal (Abela 2001; O’Brien 2009), the common good of the firm helps managers to move away from an exclusive view of profit. But at the same time, it enables them to give value to the economic dimension and to connect it with the social, ethical, and environmental dimensions. The concept of the common good of the firm may be more demanding and consistent than corporate social responsibility, insofar as it implies that business organizations’ main activity is to contribute to a real societal good as opposed to an apparent good (Alford and Naughton 2002). The common good of the firm may be also different from liberation management (Laloux 2014; Peters 1992) as the former positions community development as a means of liberating persons within organizations, whereas the latter often considers personal liberation as a means of achieving community development. Therefore, we do not restrict the common good of the firm to collaborative work. We propose a broader definition of this concept. We suggest that the common good of the firm gives the possibility for a human community of all relevant stakeholders to collaborate, through the realization of humanistic management that makes the community good the means of the personal development of each member.

The two humanistic movements discussed in this article are relatively recent, and, as such, our analysis was primarily based on the founders’ discourses and other sources. This may inadvertently have led to a focus on the entrepreneurial and managerial intention and not the real and full consequences of the action. It would be unwise to consider intentionality as the only criterion for analyzing the common good of the firm. In our view, however, there would be an even greater danger in making the common good of the firm a guide for managerial action but overlooking the primary role of the firm’s leaders. Middle and lower-level managers as well as other employees could suffer from some of the tensions we have highlighted especially in cases when the most senior leaders of the firm would not be supportive. That is why we propose more research that could provide in-depth case studies to help us better understand the character but also the intentions of the humanistic firms’ leaders. In this article, we have demonstrated that the peculiarity of humanistic management lies in the ability to identify more precisely the nature of the interaction between community good and personal good. Thus, future research could investigate what types of humanistic leadership practices and styles help managers to link community good and personal good, and therefore fully participate in the common good.

Notes

Our coverage of data included eight entrepreneurs’ testimonies, one academic thesis and 51 research theses, 27 conference presentations (Brasilia, 25–29 May 2011; Paris, 10 September 2011; Paris, 17 October 2013; Aix-en-Provence, 21 January 2012), 20 presentations at the UNESCO conference (2008), four reports on the Economy of Communion, and three essays.

References

Abela, A. V. (2001). Profit and more: Catholic social teaching and the purpose of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 107–116.

Aburdene, P. (2005). Megatrends 2010: The rise of conscious capitalism. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads.

Acevedo, A. (2012). Personalist business ethics and humanistic management: Insights from Jacques Maritain. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(2), 197–219.

Alford, H., & Naughton, M. (2002). Beyond the shareholder model of the firm: Working toward the common good of a business. In S. A. Cortright & M. J. Naughton (Eds.), Rethinking the purpose of business: Interdisciplinary essays from the Catholic social tradition (pp. 27–47). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Aquinas, St. T. (1947) [1273]. Summa theologica. New York: Benziger Bros.

Argandona, A. (1998). The stakeholder theory and the common good. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(9/10), 1093–1102.

Argiolas, G. (2009). Economia di comunione e management: un modello di lettura [Economy of communion and management: A model of reading]. Revue Impresa Sociale, 78(3), 122–140.

Argiolas, G., Baldarelli, M.-G., Ferrone, C., & Parolin, G. (2010). Spirituality and economic democracy: The case of Loppiano Prima. In L. Bouckaert & P. Arena (Eds.), Respect and economic democracy (pp. 155–172). Antwerp: Garant.

Baldarelli, M.-G. (2011). Le aziende dell’economia di comunione. Mission, governance e accountability. Rome: Città Nuova.

Barnes, J. (1984). The complete works of Aristotle. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bruni, L. (Ed.). (2002). The economy of communion. New York: New City Press.

Bruni, L., & Smerilli, A. (2009). The value of vocation: The crucial role of intrinsically motivated people in value-based organisations. Review of Social Economy, 67(3), 271–288.

Bruni, L., & Uelmen, A. (2006). Religious values and corporate decision making: The economy of communion project. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, 11(3), 645–680.

Bruni, L., & Zamagni, S. (2004). The ‘economy of communion’: Inspirations and achievements. Revue Finance et Bien Commun, 20, 91–97.

Buber, M. (1937). I and thou. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Byron, W. J. (1988). Twin towers: A philosophy and theology of business. Journal of Business Ethics, 7(7), 525–530.

Cortright, S. A., & Naughton, M. (Eds.). (2002). Rethinking the purpose of business: Interdisciplinary essays from the Catholic social tradition. Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press.

De Bettignies, H.-C., & Lépineux, F. (2009). Can multinational corporations afford to ignore the global common good? Business and Society Review, 114(2), 153–182.

Deissenberg, C. G., & Alvarez, G. (2002). Cheating for the common good in a macroeconomic policy game. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 26(9/10), 1457–1479.

Denison, D., Hoojberg, R., & Quinn, R. (1995). Paradox and performance: Toward a theory of behavioral complexity in managerial leadership. Organization Science, 6(5), 524–540.

Evangelii Gaudium. (2013). Available at https://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium.html.

Fessard, G. (1944). Autorité et bien commun. Paris: Aubier.

Finnis, J. (1986). Natural law and natural rights. Oxford: Clarendon.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Frémeaux, S., & Michelson, G. (2011). ‘No strings attached’: Welcoming the existential gift in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(1), 63–75.

Fyke, J. P., & Buzzanell, P. M. (2013). The ethics of conscious capitalism: Wicked problems in leading change and changing leaders. Human Relations, 66(12), 1619–1643.

Gallagher, J., & Buckeye, J. (2014). The business practices of the economy of communion. New York: New City Press.

Gold, L. (2004). The ‘economy of communion’: A case study of business and civil society in partnership for change. Development in Practice, 14(5), 633–644.

Gold, L. (2010). New financial horizons: The emergence of an economy of communion. New York: New City Press.

Guidelines to running an Economy of Communion Business (GECB) (2011). Available at http://www.edc-online.org/en/businesses/guidelines-for-conducting-a-business.html.

Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations. Belgium: Nelson Parker.

Lubich, C. (2001). L’economia di comunione, storia e profezia. Rome: Città Nuova.

Lubich, C. (2007). Essential writings: Spirituality, dialogue, culture (compiled and edited by M. Vandeleene). London: New City Press.

MacIntyre, A. (1981). After virtue. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Mackey, J., & Sisodia, R. (2013). Liberating the heroic spirit of business: Conscious capitalism. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37.

Melé, D. (2003). The challenge of humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(1), 77–88.

Melé, D. (2009). Integrating personalism into virtue-based business ethics: The personalist and the common good principles. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 227–244.

Melé, D. (2012). The firm as a community of persons: A pillar of humanistic business ethos. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 89–101.

Melé, D., & Schlag, M. (Eds.). (2015). Humanism in economics and business: Perspectives of the Catholic social tradition. Dordrecht: Springer.

Messner, J. (1965). Social ethics: Natural law in the modern world. Saint Louis, MO: Herder.

Mounier, E. (1970). Personalism (P. Mairet, Trans.). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Neville, M. G. (2008). Positive deviance on the ethical continuum: Green mountain coffee as a case study in conscientious capitalism. Business and Society Review, 113(4), 555–576.

O’Brien, T. (2009). Reconsidering the common good in a business context. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(1), 25–37.

Pelligra, V., & Ferrucci, A. (2004). Economia di comunione, una cultura nuova. Rome: Quaderni di Economia di Comunione.

Peters, T. (1992). Liberation management: Necessary disorganization for thenanosecond nineties. New York: Random House.

Pontifical Commission of Justice and Peace. (2004). Compendium of the social doctrine of the church. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice.

Quinn, R., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). A competing values approach to organizational effectiveness. Public Productivity Review, 5(2), 122–140.

Sandelands, L. (2009). The business of business is the human person: Lessons from the Catholic social tradition. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(1), 93–101.

Schlag, M. (2012). The encyclical Caritas in Veritate, Christian tradition and the modern world. In M. Schlag & J. A. Mercado (Eds.), Free markets and the culture of the common good (pp. 93–109). Dordrecht: Springer.

Sisodia, R. (2011). Conscious capitalism, a better way to win: A response to James O’Toole and David Vogel’s ‘Two and a half cheers for conscious capitalism’. California Management Review, 53(3), 98–108.

Sisodia, R., Wolfe, D. B., & Sheth, J. N. (2011). Firms of endearment: How world-class companies profit from passion and purpose. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Sison, A. J. G. (2007). Toward a common good theory of the firm: The Tasubinsa case. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 471–480.

Sison, A. J. G., & Fontrodona, J. (2012). The common good of the firm in the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(2), 211–246.

Sison, A. J. G., & Fontrodona, J. (2013). Participating in the common good of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(4), 611–625.

Spitzeck, H. (2011). An integrated model of humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(1), 51–62.

Weil, S. (1952a). Gravity and grace. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Weil, S. (1952b). The need for roots. London: Routledge Kegan Paul.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful suggestions. We also thank Anouk Grevin and Luigino Bruni, members of GRACE, and Julie Bayle-Cordier for their expertise in this research area. The article also benefitted from feedback when first presented at the 4th International Colloquium on Christian Humanism in Economics and Business, Barcelona, April 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frémeaux, S., Michelson, G. The Common Good of the Firm and Humanistic Management: Conscious Capitalism and Economy of Communion. J Bus Ethics 145, 701–709 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3118-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3118-6