Abstract

This research contributes to an improved understanding of authentic leadership at the work–life interface. We build on conservation of resources theory to develop a leader–follower crossover model of the impact of authentic leadership on followers’ job satisfaction through leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance. The model integrates authentic leadership and crossover literatures to suggest that followers perceive authentic leaders to better balance their professional and private lives, which in turn enables followers to achieve a positive work–life balance, and ultimately makes them more satisfied in their jobs. Data from working adults collected in a correlational field study (N = 121) and an experimental study (N = 154) generally supported indirect effects linking authentic leadership to job satisfaction through work–life balance perceptions. However, both studies highlighted the relevance of followers’ own work–life balance as a mediator more so than the sequence of leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance. We discuss theoretical implications of these findings from a conservation of resources perspective, and emphasize how authentic leadership represents an organizational resource at the work–life interface. We also suggest practical implications of developing authentic leadership in organizations to promote employees’ well-being as well as avenues for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the Gallup Engagement Index, many employees feel disengaged on their jobs and dislike them (Gallup 2014). This finding is not surprising given the fact that due to recent corporate scandals (e.g., Enron, Worldcom) public trust in business organizations has largely suffered (Rosenthal 2012). Moreover, the modern working population is faced with adverse conditions including high and rising rates of job loss (Strully 2009), and increasing polarization into high-wage and low-wage employment (Autor and Dorn 2013). The negative impact of adverse working conditions is particularly detrimental as on average workdays, employees spend the largest share of their time working (8.8 h), only paralleled by sleeping (7.7 h), with much less time dedicated to leisure and sports (2.6 h; Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014).

Many organizations strive to enhance the work–life balance of their employees (e.g., through flexible working practices, family-friendly policies; Fleetwood 2007; Morganson et al. 2014; Munn 2013; Wang and Verma 2012) with the aim of promoting satisfaction and productivity. In line with the practical demand, psychological research at the work–life interface has flourished (e.g., DiRenzo et al. 2011; Haar et al. 2014; Koch and Binnewies 2015; Michel et al. 2011; Shaffer et al. 2011; Syrek et al. 2013). In particular, scholars seek to explain how social and psychological resources buffer negative effects of adverse working conditions (e.g., Demerouti et al. 2012; Odle-Dusseau et al. 2012; Paustian-Underdahl and Halbesleben 2014).

Conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2002) posits that individuals are motivated to “obtain, retain, and protect resources” (Hobfoll 2002, p. 312), and that perceptions of stress result from resource threat or loss. In line with this reasoning, research has established supervisory support (Kossek et al. 2011; McCarthy et al. 2013) and role modeling (Koch and Binnewies 2015) as antecedents to positive work–life experiences. Moreover, leadership appears to buffer or exacerbate potential negative effects of organizational stressors on work–life balance (Carlson et al. 2012; Syrek et al. 2013).

This research builds on conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2002) to develop a model that links authentic leadership to followers’ job satisfaction through leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance. In doing so, we propose a crossover process of work–life balance perceptions. Crossover concerns inter-individual transmission of stress and strain from one individual to another when they share the same social environment (Bolger et al. 1989). Crossover is said to occur due to common stressors, indirect mediating processes (e.g., coping strategies, social support, social undermining), or direct empathic crossover (Westman and Vinokur 1998).

According to Westman (2001), crossover within the work domain develops between co-workers at the same level (e.g., in work teams; Bakker et al. 2006; van Emmerik and Peeters 2009), but also at different hierarchical levels (e.g., supervisors and subordinates; Carlson et al. 2011; ten Brummelhuis et al. 2014). With regard to future crossover research, according to Westman (2001), top-down transmission processes from supervisors to their subordinates and positive crossover need to be considered more carefully. Just as well as stress and strain transfer from one individual to another, positive experiences at work may cross over (Bakker et al. 2009). The concept of top-down crossover of positive experiences is a main driver of our research. Specifically, we seek to explore whether work–life balance perceptions cross over from leaders to followers, whether authentic leadership facilitates this process, and whether it in turn positively impacts job satisfaction.

Thereby, we contribute to current literature in the following ways: First, we conceptually connect authentic leadership and work–life balance. With its roots in positive psychology, authentic leadership has been said to instill hope and optimism (Avolio et al. 2004), positive health (Macik-Frey et al. 2009), and eudemonic well-being (Ilies et al. 2005). While empirical findings relate authentic leadership positively to psychological capital (Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Rego et al. 2012), positive working relations (Wang et al. 2014), well-being (Toor and Ofori 2009), empowerment (Wong and Laschinger 2013), and negatively to adverse health outcomes (e.g., burnout, stress; Laschinger and Fida 2014a, b; Laschinger et al. 2012; Rahimnia and Sharifirad 2014), there is no research that links it to leaders’ or followers’ work–life balance. In the face of organizational initiatives and government policies for employee well-being (Fleetwood 2007; Morganson et al. 2014; Munn 2013; Wang and Verma 2012), and a range of positive outcomes that work–life balance holds (e.g., job satisfaction, life satisfaction, mental health; Haar et al. 2014; career advancement potential; Lyness and Judiesch 2008), we believe that analyzing this relationship is an important endeavor. Empirical insights from our research will extend the current scientific understanding of authentic leadership as an antecedent to healthy and productive work environments (Ilies et al. 2005; Macik-Frey et al. 2009).

Second, we empirically test the proposed relations in a leader–follower crossover model. In this model, we focus on the followers’ perspective and analyze their perceptions of their own and their leaders’ work–life balance. Due to its relational nature, authentic leadership fosters open, trusting relations between leaders and followers (Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Peus et al. 2012b; Wang et al. 2014). We argue that crossover occurs through an indirect crossover mechanism. While initial empirical evidence highlights the relevance of leadership for crossover processes (Carlson et al. 2011; Koch and Binnewies 2015; ten Brummelhuis et al. 2014) to our best knowledge, we provide the first study including authentic leadership as an antecedent to crossover. Empirical insights from our research will extend the current scientific understanding of authentic leadership as an antecedent to crossover.

Third, the scholarly study of crossover is lacking empirical evidence from non-correlational research designs (Bakker et al. 2007; Westman 2001). The same concern has been voiced for authentic leadership (Gardner et al. 2011). We therefore add methodological breadth to research in both fields by integrating empirical evidence from a field study and a controlled experimental design, both conducted with working adult samples.

To summarize, with this work we address two overarching research problems. The first problem is that to date too little is known about how authentic leadership fuels positive outcomes related to health and well-being in organizations (Ilies et al. 2005; Laschinger et al. 2012; Rahimnia and Sharifirad 2014). The second problem addressed by this research is that current empirical work provides only initial insights into positive crossover of work–life experiences from leaders to followers (ten Brummelhuis et al. 2014), and it remains unclear how authentic leadership fuels these processes. Our research is therefore needed in order to integrate models of authentic leadership and crossover, thereby contributing to an advanced understanding of both concepts. Further, there is a practical necessity for this research. Organizations need to understand better how authentic leadership contributes to satisfaction through positive work–life experiences of leaders and followers (O’Neill et al. 2009).

Authentic Leadership

While many modern theories of leadership are bound to understanding human functioning from the perspective of homo economicus (Lawrence and Pirson 2014), this is not the case for authentic leadership. Authentic leadership finds its conceptual roots in positive psychology, and especially so in the concepts of positive growth and self-fulfillment. Leadership scholars built upon these roots to further develop the construct. Authenticity is referred to as “the unobstructed operation of one’s true, or core, self in one’s daily enterprise” (Kernis 2003, p. 1) or, as Harter (2002) put it, acting “in accord with the true self, expressing oneself in ways that are consistent with inner thoughts and feelings” (p. 382). The components of authenticity as described by Kernis (2003), that is, awareness, unbiased processing, action, and relational orientation, were picked up to define the four dimensions of authentic leadership (Walumbwa et al. 2008): (1) self-awareness (i.e., being aware of one’s own strengths and weaknesses), (2) relational transparency (i.e., emphasizing open and transparent communication), (3) internalized moral perspective (i.e., acting in accordance with strong moral convictions and values), and (4) balanced processing (i.e., considering multiple perspectives prior to decision-making). Authentic leaders “know who they are, what they believe and value, and […] act upon those values and beliefs while transparently interacting with others” (Avolio et al. 2004, p. 802).

Authentic leadership is thought to foster positive self-development of leaders and followers (Avolio and Gardner 2005), and thus to drive health and well-being in organizations (Gardner et al. 2011). According to a theoretical model by Ilies et al. (2005), authentic leadership can be mapped onto the six dimensions of well-being (Keyes et al. 2002): (1) autonomy (i.e., self-determined and self-regulated action), (2) environmental mastery (i.e., managing and shaping the environment in accordance with personal needs), (3) personal growth (i.e., living up to one’s full potential), (4) positive relations with others (i.e., trusting and identified relationships), (5) purpose in life (i.e., an underlying meaning to one’s actions and efforts), and (6) self-acceptance (i.e., feeling good about oneself and knowing one’s limitations).

To summarize, in this paragraph we argued that existing theory from humanistic and positive psychology links authentic leadership to well-being in organizations. Next, we apply conservation of resources theory to frame leadership as an organizational resource, and then link authentic leadership to positive perceptions of work–life balance.

Conservation of Resources

Conservation of resources theory’s basic assumption is that individuals “strive to retain, protect, and build resources and that what is threatening to them is the potential or actual loss of these valued resources” (Hobfoll 1989, p. 516). Originally, different kinds of resources according to the theory included the following: object resources that are valued by their physical nature, such as the physical work environment, conditions that individuals find themselves in, such as terms of employment, personal characteristics that aid stress resistance, such as self-esteem or resilience, and energies for acquisition of other resources (e.g., money).

Drawing from conservation of resources theory, ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012) formulated a work–home resources model. It classifies the origins of a resource, contextual (outside of the individual) or personal (within the individual), and the extent to which a resource is transient, namely volatile (temporal) or structural (durable). Social support from superiors is considered a contextual, volatile resource (ten Brummelhuis and Bakker 2012).

We concur with this resource view of leadership at the work–life interface for the following reasons. First, supervisor supportiveness of work–life balance practices has been shown to positively affect employees’ uptake of such programs and related outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction; McCarthy et al. 2013). Supervisor support of work–family integration is a stronger negative predictor of work–family conflict than general supervisor support (Kossek et al. 2011). Supervisors act as role models at the work–life interface (Koch and Binnewies 2015), and supervisory work–family enrichment creates a family-friendly work environment (Carlson et al. 2011).

Second, leadership styles buffer or exacerbate potential negative effects of organizational stressors on work–life balance. Transformational leadership reduces the negative impact of time pressure on work–life balance (Syrek et al. 2013), while abusive supervision increases followers’ work–family conflict (Carlson et al. 2012). Moreover, drawing from positive psychology, authentic leadership has been proposed to shape leaders’ and followers’ health and well-being in organizations (Ilies et al. 2005; Macik-Frey et al. 2009).

To summarize, in this paragraph we characterized leadership as a resource in the face of stress and strain at the work–life interface. We next transfer these arguments to authentic leadership suggesting that it is a resource in organizations, which promotes work–life balance.

Authentic Leadership and Work–life Balance

Work–life balance is used as an umbrella term for an array of different constructs (Jones et al. 2006) between which the terminology varies (i.e., combinations of the terms ‘work,’ ‘life,’ ‘home,’ ‘family,’ ‘conflict,’ ‘balance,’ ‘fit,’ ‘interface,’ ‘integration,’ ‘enrichment’). Work–life balance goes beyond work–family conflict, because it covers the entire private life (including family) and focuses on balance, that is, an intended “harmony or equilibrium between work and life domains” (Chang et al. 2010, p. 2382). Specifically, work–life balance is defined as the perceived accord between the arrangement of different areas, roles, and goals in life that one targets and its actual realization (Syrek et al. 2011). Employees feel that their private and professional life domains are in balance when they perceive themselves to be effective and satisfied in the multiple roles that they are faced with.

Drawing from conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2002) and work–home resources model (ten Brummelhuis and Bakker 2012), we argue that authentic leadership is a resource for work–life balance. With reference to three major characteristics—self-reflective capacities, moral values, and individual growth through interpersonal consideration—we assume that authentic leaders are capable of promoting their own and others' work–life balance.

First, notions of self-reflective capacities (i.e., the authentic self) are inevitably intertwined with authentic leadership (Koole and Kuhl 2003). Authentic leaders who know themselves well are transparent about their own needs, expectations, and values, which guide their behaviors “every day, in each and every interaction” (May et al. 2003, p. 248). Authentic leadership is based on a self-awareness component on the one hand, and a self-regulation component on the other hand (Gardner et al. 2005). Authentic leaders gain self-awareness through self-reflection and introspection. Self-regulation is a means of self-control that authentic leaders exert based on internal standards. External pressures and expectations determine the actions of authentic leaders to a much lesser extent than their internal frame of reference. Accordingly, Peus et al. (2012b) demonstrated leaders’ self-knowledge and self-consistency as antecedents to authentic leadership. Due to their self-reflective and self-regulative capacities, we assume that authentic leadership allows leaders to successfully balance their own needs at the work–life interface. In line with this reasoning, initial evidence from a small sample of 32 managers in the construction industry in Singapore suggests that authentic leadership correlates positively with leaders’ psychological well-being (Toor and Ofori 2009).

Second, in modern organizations, where values are “both difficult to know and difficult to realize” (Freeman and Auster 2011, p. 16), it is particularly challenging for leaders and followers to reach clarity about their personal values and to translate them into everyday actions. We regard authentic leadership as a value-based leadership style, characterized by a higher moral capacity and resiliency (May et al. 2003). Authentic leadership encompasses positive self-transcendent values, that is, concern for the enhancement of all (e.g., well-being), as well as benevolent values, that is, concern for immediate others (e.g., responsibility). These values contrast self-enhancement values of achievement, power, and hedonism (Schwartz 1994). Michie and Gooty (2005) argued that authentic leaders prioritize self-transcendent over self-enhancement values. In line with this view, recent research confirmed that authentic leaders are attributed higher levels of behavioral integrity (Leroy et al. 2012b). Accordingly, we propose that authentic leaders who are driven by values will accept responsibility for their own and others' well-being, and that one way of doing so is to promote a positive work–life balance.

Third, authentic leaders nurture “open, transparent, trusting and genuine relationships” with their followers (Avolio and Gardner 2005, p. 322). It has been demonstrated that through these relational processes (e.g., leader–member exchange, trust) authentic leadership fosters followers’ psychological capital (Wang et al. 2014) and gives others voice in decision processes (Hsiung 2012). Further, close relationships with authentic leaders promote follower authenticity (Algera and Lips-Wiersma 2012). For example, Yagil and Medler-Liraz (2014) found that authentic leadership mitigated followers’ concerns about negative consequences of authentic emotional expressions. Based on these findings, we suggest that through positive relationship building, authentic leaders support followers who seek to establish a positive balance between needs of their private and professional life domains.

Empirical research on the relationships between authentic leadership and constructs at the work–life interface is scarce. Hitherto published studies generally support the notion that authentic leadership fosters health-related outcomes in organizations. In a sample of 212 health care providers from five Iranian hospitals, authentic leadership was significantly related to three well-being measures. Positive relations with job satisfaction were obtained as well as negative relations with perceived work stress and stress symptoms (Rahimnia and Sharifirad 2014). Furthermore, authentic leadership was related negatively to turnover intentions mediated by perceptions of bullying and burnout of 205 new graduate nurses working in acute care settings (Laschinger and Fida 2014a).

To summarize, in this paragraph we proposed three main characteristics—self-reflective capacities, moral values, and individual growth through interpersonal consideration—to link authentic leadership and work–life balance perceptions. The purpose of the following paragraph is to derive three hypotheses on the relations between authentic leadership on the one hand and followers’ job satisfaction as well as leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance on the other hand in a crossover model.

Hypotheses

Followers’ satisfaction with their jobs belongs to the best-studied outcomes of leadership and relates to manifold desirable consequences, among them helping behaviors, work engagement, improved health (i.e., reduction of sick days), and reduced turnover intentions (Spector 1997). Moreover, job satisfaction and life satisfaction have been shown to be significantly and reciprocally correlated (Judge and Watanabe 1993).

Since authentic leaders build trusting relationships with their followers (Hassan and Ahmed 2011), take followers’ perspectives and opinions into account (e.g., voice), and act based on moral values (e.g., fairness, transparency), it is viable to assume that they instill satisfaction in followers. Furthermore, authentic leaders have been posited to create positive emotional states in the workplace and therefore to foster followers’ positive attitudes and behaviors, for instance, their satisfaction (Avolio et al. 2004). We seek to replicate earlier research indicating a positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (Giallonardo et al. 2010; Jensen and Luthans 2006; Neider and Schriesheim 2011; Peus et al. 2012b). Thus, our first hypothesis posits:

Hypothesis 1

Authentic leadership is positively related to followers’ job satisfaction.

Theoretical models link authentic leadership to positive health (Macik-Frey et al. 2009) and eudemonic well-being (Ilies et al. 2005). According to empirical insights, authentic leadership relates positively to positive psychological capital (Clapp-Smith et al. 2009; Rego et al. 2012) and psychological well-being (Toor and Ofori 2009), and negatively to adverse health outcomes (e.g., stress; Rahimnia and Sharifirad 2014; Laschinger and Fida 2014b; Laschinger et al. 2012). As outlined above, we believe that there are three main drivers of followers’ work–life balance in authentic leadership: self-reflection and self-regulation (Gardner et al. 2005; Peus et al. 2012b), leaders’ value-based behavior (e.g., Leroy et al. 2012b; Michie and Gooty 2005), and the open and trusting relationships they build with followers (Hsiung 2012; Wang et al. 2014). A positive work–life balance, in turn, has been shown to lead to a range of desirable outcomes, among them job and life satisfaction (Haar et al. 2014). In essence, when followers feel that they are able to balance demands from private and professional life domains, they will be more satisfied at work. Thus, our second hypothesis posits:

Hypothesis 2

Followers’ work–life balance mediates the positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction.

Finally, we suggest a crossover mechanism between perceptions of leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance, which links authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction. Drawing from common conceptualizations of crossover (Bakker et al. 2009; Bakker and Demerouti 2009; Bakker and Xanthopoulou 2009; Westman and Etzion 2005; Westman 2001), we suggest that perceptions of work–life balance will cross over from leaders to followers.

Research of crossover in leader–follower relations is relatively scarce. Koch and Binnewies (2015) established a crossover effect of work–home segmentation behavior mediated by perceptions of supervisory role modeling in a sample of 75 leaders and 237 followers. This finding corresponds to an indirect mediating process of crossover (Westman and Vinokur 1998). Similarly, crossover of leaders’ to followers’ work–family enrichment has been demonstrated: In a sample of 48 leaders and 161 followers, a crossover effect occurred due to greater perceived schedule control (Carlson et al. 2011). Finally, ten Brummelhuis et al. (2014) showed that leaders’ well-being, determined by work–family conflict and enrichment, shaped followers’ well-being (i.e., burnout and engagement).

As indicated above, authentic leaders have the self-reflective capacities (Peus et al. 2012b) and strong transcendent values (Leroy et al. 2012b; Michie and Gooty 2005) to guide them in the quest for work–life balance. In line with conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2002), authentic leadership is a personal resource for leaders themselves (Toor and Ofori 2009). Their internal frame of reference is stronger than external pressures. Furthermore, authentic leaders are “positive behavioral models for personally expressive and authentic behaviors” (Ilies et al. 2005, p. 383), and enhance followers’ self-determination and self-regulated action (i.e., authentic followership; Leroy et al. 2012a) for the management of work–life balance.

Authentic leaders are role models for their followers because they openly share opinions and emotions in trusting relationships (Hsiung 2012; Wang et al. 2014). Thus, followers will be aware of their authentic leaders’ work–life balance and can take it as an inspiration for their own management of the work–life interface. Yet, authentic leaders are unlikely to impress their subjective understanding of a good work–life balance onto their followers. Rather, authentic leadership encourages authentic followership (Leroy et al. 2012a). It is through this positive crossover effect that followers of authentic leaders are ultimately more satisfied in their jobs. Thus, our third hypothesis posits:

Hypothesis 3

Leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance sequentially mediate the positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction.

Finally, note that we do not expect mediation to occur between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction through leaders’ work–life balance only. It is unlikely that leaders’ positive work–life balance will automatically increase followers’ positive feelings about their jobs. Rather, we expect followers to be more satisfied when authentic leadership and leaders’ positive work–life balance foster their own positive experiences at the work–life interface.

To summarize, we hypothesize that authentic leadership positively affects followers’ job satisfaction (Hypothesis 1). We assume that followers’ work–life balance mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (Hypothesis 2). We hypothesize that leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance constitute a sequential crossover mechanism through which authentic leaders promote followers’ job satisfaction (Hypothesis 3).

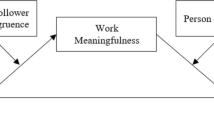

Figure 1 presents the research model of the hypothesized relations.

Study 1

The first study was designed to test the proposed crossover model of authentic leadership in a field setting. Specifically, we sought to examine if authentic leadership predicts followers’ job satisfaction through leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Data were collected in a field survey of 121 employees from different organizations in Germany. The sample consisted of 72 men and 46 women (3 missing) who were between 21 and 60 years old (M = 34.03, SD = 9.86, Med = 30.00). Participants in the sample covered a wide range of work experience: up to 2 years (20.7 %), between 3 and 5 years (31.4 %), between 6 and 10 years (17.4 %), between 11 and 20 years (10.7 %), and 21 years or more (17.4 %) with 2.5 % missing. They represented organizations of different sizes: up to ten employees (7.4 %), up to 50 employees (14.0 %), up to 250 employees (14.0 %), up to 500 employees (12.4 %), and more than 500 employees (47.1 %) with 5.0 % missing. The organizations represented different sectors with a majority being in manufacturing (28.1 %) and services (24.8 %), followed by social, education, and health (14.9 %), research and science (6.6 %), public administration (4.1 %), retail (2.5), other sectors (14.9 %), with 4.1 % missing.

Participants were recruited by means of mailings and postings in personal and online networks (e.g., Facebook), and were invited to take part in an online survey. Participants rated their leaders’ authentic leadership and perceived work–life balance. Moreover, they indicated their own work–life balance, job satisfaction, job involvement, and leader–member exchange. Completion of the survey took approximately 10–15 min. They were informed that participation in the study was voluntary. As an incentive, we offered a donation of five Euros per participant to a social project.

Measures

Authentic Leadership

We measured authentic leadership with 15 items (α = .95) from a validated German translation (Peus et al. 2012b) of the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (Walumbwa et al. 2008) covering authentic leadership as a second-order factor comprising the four first-order factors: (1) self-awareness (e.g., “My supervisor knows when it is time to re-evaluate his or her positions on important issues”), (2) relational transparency (e.g., “My supervisor says exactly what he or she means”), (3) internalized moral perspective (e.g., “My supervisor makes difficult decisions based on high standards of ethical conduct”), and (4) balanced processing (e.g., “My supervisor listens carefully to different points of view before coming to conclusions”). The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“frequently, if not always”). Based on earlier results testing the factorial structure of the German ALQ (Peus et al. 2012b), we used a composite score of authentic leadership as a second-order factor comprising the four first-order factors. This approach is in line with the original factorial solution proposed by Walumbwa et al. (2008).

Leaders’ Work–Life Balance

We measured leaders’ work–life balance with three items (α = .76) from a work–life balance scale (Syrek et al. 2011). The items were adapted to fit followers’ perceptions of their leaders’ work–life balance. Sample item included “It seems to me that it is difficult for my supervisor to combine his/her professional and private life” (reverse coded). The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Followers’ Work–Life Balance

We measured followers’ work–life balance with the same three items (α = .87) from the work–life balance scale (Syrek et al. 2011) that were used to measure leaders’ work–life balance. Sample items included “It is difficult for me to combine professional and private life” (reverse coded). The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Followers’ Job Satisfaction

We measured followers’ job satisfaction with five items (α = .86) from a validated index of job satisfaction (Brayfield and Rothe 1951). The items were translated into German following a standard procedure of translation and independent back-translation (Brislin 1970). Items included “I feel fairly satisfied with my present job,” “Most days I am enthusiastic about my work,” “Each day of work seems like it will never end” (reverse coded), “I find real enjoyment in my work,” and “I consider my job rather unpleasant” (reverse coded). The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Control Variables

To eliminate potential alternative explanations and demonstrate the unique relationships between the study variables of interest, we considered the following control variables: participants’ age (in years), sex, job involvement, and perceptions of leader–member exchange. We measured job involvement with three items (α = .70) from Kanungo’s (1982) Job Involvement Questionnaire (“I consider my job to be very central to my existence,” “Most of my personal life goals are job-oriented,” “I am very much involved personally in my job”). The items were translated into German following a standard procedure of translation and independent back-translation (Brislin 1970). The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“fully disagree”) to 5 (“fully agree”). We further employed one item from a validated German translation (Schyns 2002) of the leader–member exchange scale (“How would you characterize your working relationship with your supervisor?”; Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995). The item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“extremely ineffective”) to 5 (“extremely effective”).

Analyses

First, we conducted descriptive and correlational analyses of the data. Second, we analyzed the model structure with confirmatory factor analysis implemented in the lavaan package (Rosseel 2012) in the open-source environment R. Third, we tested the hypothesized relationships in a mediation model based on a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Hayes 2013). This model is distinct from other (multiple) mediator models because it investigates the direct and indirect effects of the independent variable X on the dependent variable Y modeling a process in which X causes a first mediator M 1, which in turn causes a second mediator M 2, which in turn causes the dependent variable Y.

Accordingly, authentic leadership (X) is linked to followers’ job satisfaction (Y) in four ways: a direct effect from authentic leadership to job satisfaction, an indirect effect through leaders’ work–life balance (M 1), an indirect effect through followers’ work–life balance (M 2), and an indirect effect through leaders’ work–life balance (M 1) and followers’ work–life balance (M 2) in sequential order. This approach isolates the indirect effects of both mediators as well as their serial indirect effect. Three of the described pathways are directly related to our hypotheses. For reasons of transparency, we decided to also report the additional indirect effect (i.e., through leaders’ work–life balance only).

Results

Correlational Analyses

Data pertaining to our hypotheses at a correlational level indicated that the hypothesized predictor authentic leadership was significantly positively related to the hypothesized mediators leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance as well as to the hypothesized outcome variable followers’ job satisfaction. Leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance were significantly positively related to each other as well as to followers’ job satisfaction. Leader–member exchange correlated positively with authentic leadership, leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance, and followers’ job satisfaction.

Table 1 displays means, standard deviations, and correlations of all study variables.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

We applied statistical remedies to account for common method biases (Podsakoff et al. 2012) that may undermine the empirical validity of results. Three a priori models of the variables included in our hypotheses were compared: a one-factor model, in which all items loaded on a common factor, was tested against a full measurement four-factor model, in which the items loaded on their respective factor (i.e., authentic leadership, leader work–life balance, follower work–life balance, job satisfaction), and a five-factor model, in which all items were further constrained to load equally on an unmeasured latent method factor. For each model, we report the χ 2 value, degrees of freedom, and probability value, as well as one index to describe incremental fit (i.e., the comparative fit index, CFI) and one residual-based fit index (i.e., the root mean square error of approximation, RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Approximate fit indices are used for evaluative model comparisons as indicated in the literature (Goffin 2007). The following standards were applied: CFI greater than .90, RMSEA equal to or lower than .06, SRMR equal to or lower than .08 (Nye and Drasgow 2011; Hu and Bentler 1998, 1999), and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) with lower values indicating better fit (Preacher and Merkle 2012).

CFA with maximum likelihood estimation yielded the following results. Comparing the one-factor model (χ 2(299, 121) = 1031.717, p < .001, RMSEA = .142, SRMR = .108, CFI = .650, BIC = 8656.249) to the four-factor model (\(\chi^{ 2}\)(293, 121) = 534.490, p < .001, RMSEA = .083, SRMR = .066, CFI = .885, BIC = 8187.796), indicators point to the fact that overall the four-factor model fits the data better (\(\chi^{ 2}_{\text{diff}}\) = 497.23, p < .001). Comparing the four-factor model and the five-factor model with an unmeasured latent method factor (\(\chi^{ 2}\)(288, 121) = 475.396, p < .001, RMSEA = .073, SRMR = .073, CFI = .910, BIC = 8152.682), the five-factor model showed a better fit (\(\chi^{ 2}_{\text{diff}}\) = 59.093, p < .001). Overall, we acknowledge that an unmeasured latent method factor influenced our data. However, the theoretically derived four-factor model was only slightly inferior to the five-factor model, and was clearly better suited to fit the data than a one-factor model, which did not differentiate between the variables of interest. Based on the empirical evidence and our theoretical reasoning, we conclude that data related to the four factors provide meaningful information.

Finally, we followed recommendations (Barrett 2007) to examine whether the data conformed to multivariate normality as an assumption for applying Maximum Likelihood estimation, and employed Satorra–Bentler scaled test statistic (Satorra and Bentler 1994) to estimate the four-factor model, which provides an effective correction of the maximum likelihood-based \(\chi^{ 2}\) test statistic with non-normal data even in small to moderate samples.

Three tests of multivariate normality were calculated in the MVN package in R (Korkmaz et al. 2014): Mardia’s test statistic based on multivariate skew and kurtosis, Henze–Zirkler’s test based on Mahalanobis distances, and Royston’s test based on the Shapiro–Wilk and Shapiro–Francia statistic. Results indicated violations of the multivariate normality assumption: both skew (ϒ 1,p = 200.9643, p < .001) and kurtosis (ϒ 2,p = 775.0091, p < .001), Henze–Zirkler’s statistic (HZ = 1.001274, p < .001) as well as Royston’s test (H = 818.59, p < .001).

Accordingly, the four-factor model was re-analyzed with the Satorra–Bentler scaled test statistic and robust standard errors. The adjusted fit indices slightly improved (χ 2(293, 120) = 471.224, p < .001, RMSEA = .071, SRMR = .065, CFI = .898). Therefore, the theoretically derived four-factor model was applied to the following hypothesis tests based on a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with the PROCESS macro in SPSS.

Serial Multiple Mediation

We tested the direct effect of authentic leadership on followers’ job satisfaction (Hypothesis 1), the indirect effect of authentic leadership on job satisfaction through followers’ work–life balance (Hypothesis 2), as well as the indirect crossover effect of leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance (Hypothesis 3). We report unstandardized coefficients below.

Contrary to Hypothesis 1, authentic leadership was not directly related to followers’ job satisfaction (b = .07, SE = .10). The confidence interval included zero (CI −.138, .273). However, as predicted in Hypothesis 2, a significant indirect effect occurred between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction through followers’ work–life balance (b = .09, SE = .06). The confidence interval did not include zero (CI .001, .216). As predicted in Hypothesis 3, leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance sequentially mediated the positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (b = .04, SE = .02). The confidence interval did not include zero (CI .006, .107). That is, authentic leadership was associated with positive perceptions of leaders’ work–life balance, which were associated with positive perceptions of followers’ own work–life balance, and in turn related to followers’ job satisfaction. Note that leaders’ work–life balance alone did not mediate the positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (b = .03, SE = .04). The confidence interval included zero (CI −.027; .132).

The indirect effects occurred independent of the inclusion or exclusion of control variables (followers’ job involvement, sex, age, and leader–member exchange). However, exclusion of control variables resulted in a significant direct relationship between authentic leadership and job satisfaction (b = .23, SE = .08; CI .083, .380).

Table 2 displays estimates of the path coefficients and indirect effects along with bias-corrected 95 % confidence intervals.

Discussion

Results of Study 1 revealed a significant indirect relation between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction through followers’ perceptions of their leaders’ and their own work–life balance. In short, authentic leaders appear to transmit positive views of how they balance demands from professional and private life domains, which in turn inspires and encourages followers to achieve a meaningful balance between their professional and private lives, and finally makes them more satisfied with their jobs. However, the primary pathway from authentic leadership to followers’ job satisfaction seemed to occur through followers’ work–life balance only rather than through the sequence of leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance. This finding required further exploration. Moreover, the leader–member exchange relationship appeared to dilute the relations of interest. In order to overcome these restrictions and to draw causal conclusions, we conducted a second study based on an experimental design.

Study 2

The second study was designed to test the proposed crossover model in an experiment. Specifically, we sought to examine if authentic leadership has a positive causal effect on perceptions of leaders’ work–life balance, which in turn would influence followers’ work–life balance and job satisfaction.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Study 2 was based on data from 154 German-speaking adults with work experience. The sample consisted of 72 men and 78 women (4 missing) who were between 17 and 70 years old (M = 33.89, SD = 14.39, Med = 27.00). They covered a wide range of work experience ranging from one to 50 years (M = 12.96, SD = 12.99, Med = 7.00). The majority of participants (74.0 %) indicated that they were employed at the time of participating in the study. The minority of participants (20.1 %) indicated that they held a leadership position at the time of participating in the study. The participants had working backgrounds in different sectors with a majority being in services (29.2 %) and social, education, and health (28.6 %), followed by manufacturing (7.1 %), retail (4.5 %), public administration (1.9 %), and other sectors (1.9 %), with 26.6 % missing.

Participants were recruited by means of mailings and postings in personal and online networks (e.g., Xing, Facebook), and were invited to take part in an online survey. Completion of the study took approximately 15–20 min. Participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary. As an incentive, we offered the participation in a raffle of three vouchers for Amazon with a value of 40 Euros each.

Participants were asked to assume the role of an employee working with his/her direct supervisor. They were provided with a written description of the supervisor’s typical behaviors corresponding to one of three study conditions (i.e., high authentic leadership, low authentic leadership, neutral control condition). After reading the description, participants indicated how they perceived the leader’s work–life balance, and how they would estimate their own work–life balance and job satisfaction when working for this leader. Participants indicated how well they identified with the described scenario, and their perceptions of the leader’s competence (control variables). At the end of the questionnaire, participants evaluated authentic leadership (manipulation check) and provided demographic data (e.g., sex, age, professional experience).

Design and Manipulations

In a one-factor between-subject experimental design, participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: high authentic leadership, low authentic leadership, or a neutral control condition with no information about the leadership style. Manipulations were adapted from a validated manipulation of authentic leadership (Cianci et al. 2014), which was translated into German for the purpose of this research following a standard procedure of independent translation and back-translation (Brislin 1970).

The manipulation was presented in a written vignette format. The text first informed all participants that their direct supervisor, like most typical managers, was concerned with meeting targets for increasing profits and market share. In the high authentic leadership condition, it was then described how the supervisor frequently acted in line with the four dimensions of authentic leadership (Walumbwa et al. 2008), that is, (1) self-awareness (e.g., the supervisor regularly seeks feedback from followers), (2) relational transparency (e.g., the supervisor frequently displays his own true emotions), (3) internalized moral perspective (e.g., the supervisor makes decisions based on his core values), and (4) balanced processing (e.g., the supervisor listens to different points of view). In contrast, in the low authentic leadership condition, it was described how the supervisor’s behavior was rarely based on the four dimensions of authentic leadership. The neutral control condition did not provide any further information about the supervisor’s leadership style. The full text of the original English version of the vignettes is available in Cianci et al. (2014).

Measures

Authentic Leadership

We measured authentic leadership with 16 items (α = .97) from the validated German translation (Peus et al. 2012b) of the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (Walumbwa et al. 2008) as described for Study 1. The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“frequently, if not always”).

Leaders’ Work–Life Balance

We measured leaders’ work–life balance with five items (α = .81) from a work–life balance scale (Syrek et al. 2011). The items were adapted to fit followers’ perceptions of their leaders’ work–life balance. Sample items included “It is difficult for this supervisor to combine his professional and private life” (reverse coded). The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Followers’ Work–Life Balance

We measured followers’ work–life balance with same five items (α = .90) from the work–life balance scale (Syrek et al. 2011) that were used to measure leaders’ work–life balance. The items were adapted to fit the experimental scenario. Sample items included “When working for this supervisor, it would be difficult for me to combine professional and private life” (reverse coded). The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Followers’ Job Satisfaction

We measured followers’ job satisfaction with the same five items (α = .94) from a validated index of job satisfaction (Brayfield and Rothe 1951) as in Study 1. Item formulations were slightly adapted to fit the experimental scenario. The items were rated on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Control Variables

To eliminate potential alternative explanations and demonstrate the unique relationships between the study variables of interest, we included the following control variables: participants’ age (in years) and sex, perceptions of the leader’s competence, and the extent to which participants identified with the written vignette scenario. Participants rated the leader’s competence with three items (“How do you evaluate this supervisor’s success?” “How do you evaluate this supervisor’s competence?” “How do you evaluate this supervisor’s leadership skills?”; α = .75) on 5-point Likert scales from 1 (“very low”) to 5 (“very high”). Participants rated their identification with the scenario (“To what extent do you identify with the role of an employee working for this supervisor?”) on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”).

Analyses

First, we conducted a manipulation check of the authentic leadership manipulation. Second, we conducted correlational analyses between study variables. Third, we employed multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) to test the impact of authentic leadership on leaders’ work–life balance, followers’ work–life balance, and followers’ job satisfaction. Fourth, as in Study 1, we tested the hypothesized relationships in a serial multiple mediator model (Hayes 2013) with high and low authentic leadership as a dichotomous predictor, and included four control variables (i.e., participants’ age (in years) and sex, leader’s competence, and the extent to which participants identified with the described scenario). Analyses were performed using the statistics software SPSS and the macro PROCESS (Hayes 2013).

Results

Manipulation Check

Confirming the results of Cianci et al. (2014), our analyses revealed a significant main effect of the experimental condition on authentic leadership ratings, F(2,151) = 187.11, p < .001. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction and 95 % confidence intervals revealed that authentic leadership was rated significantly higher in the high authentic leadership condition (M = 3.95, SD = .53) than in the low authentic leadership condition (M = 1.86, SD = .38; 95 % CI 1.84, 2.36), and than in the neutral control condition (M = 2.87, SD = .76; 95 % CI .81, 1.36). Thus, the manipulation of authentic leadership was successful.

Correlational Analyses

Data pertaining to our hypotheses at a correlational level indicated that the hypothesized predictor authentic leadership was significantly positively related to the hypothesized mediators leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance as well as to the hypothesized outcome variable followers’ job satisfaction. Leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance were significantly positively related to each other as well as to followers’ job satisfaction. Perceptions of the leader’s competence correlated positively with authentic leadership, leaders’ work–life balance, followers’ work–life balance, and job satisfaction as well as negatively with participants’ age.

Table 3 displays means, standard deviations, and correlations of all study variables.

MANOVA and Post Hoc Tests

Multivariate analysis of variance for the dependent variables leaders’ work–life balance, followers’ work–life balance, and followers’ job satisfaction revealed a significant main effect of authentic leadership, F(6,298) = 23.68, p < .001, η 2 = .323. This main effect occurred for all three dependent variables: leaders’ work–life balance (F(2,151) = 18.42, p < .001, η 2 = .196), followers’ work–life balance (F(2,151) = 25.07, p < .001, η 2 = .249), and followers’ job satisfaction (F(2,151) = 73.79, p < .001, η 2 = .494).

Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction and 95 % confidence intervals revealed that leaders’ work–life balance was rated significantly higher in the high authentic leadership condition (M = 3.96, SD = .79) than in the low authentic leadership condition (M = 3.03, SD = .75; 95 % CI .56, 1.31), and than in the neutral control condition (M = 3.38, SD = .88; CI .19, .97). Similarly, followers’ work–life balance was rated significantly higher in the high authentic leadership condition (M = 4.19, SD = .76) than in the low authentic leadership condition (M = 3.06, SD = .79; CI .72, 1.55), and than in the neutral control condition (M = 3.21, SD = 1.11; CI .54, 1.42). Finally, followers’ job satisfaction was rated significantly higher in the high authentic leadership condition (M = 3.91, SD = .61) than in the low authentic leadership condition (M = 2.12, SD = .68; CI 1.43, 2.15), and than in the neutral control condition (M = 2.99, SD = .99; CI .54, 1.30). The finding that authentic leadership was significantly positively related to followers’ job satisfaction provided initial evidence supporting Hypothesis 1, which was further corroborated in a serial multiple mediator model in the following analyses.

Table 4 displays means and standard deviations for dependent variables by experimental condition (i.e., high authentic leadership, low authentic leadership, neutral control condition).

Serial Multiple Mediator Model

We tested the hypothesized serial multiple mediator model in order to analyze the direct effect of authentic leadership on followers’ job satisfaction (Hypothesis 1), the indirect effect of followers’ work–life balance separately (Hypothesis 2), as well as the indirect crossover effect through leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance in sequence (Hypothesis 3). Following the example of Hayes (2013), we used high and low authentic leadership as a dichotomous predictor, wherein high authentic leadership was coded 1 and low authentic leadership was coded 0. Since the positive effects of high authentic leadership compared to the neutral control condition had already been established in the MANOVA, we did not test a second model with high authentic leadership and the neutral control condition. We report unstandardized coefficients below.

As predicted in Hypothesis 1, authentic leadership was significantly positively related to followers’ job satisfaction (b = .95, SE = .19). The confidence interval did not include zero (CI .569, 1.331). As predicted in Hypothesis 2, followers’ work–life balance mediated the positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (b = .40, SE = .13). The confidence interval did not include zero (CI .184, .726). As predicted in Hypothesis 3, leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance sequentially mediated the positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (b = .08, SE = .06). The confidence interval did not include zero (CI .018, .264). That is, authentic leadership was associated with a positive perception of the leaders’ work–life balance, which was associated with a better work–life balance of the follower, and in turn related to higher degrees of followers’ job satisfaction. Notably, while statistically significant, the sequential indirect effect was smaller than the indirect effect through followers’ work–life balance only. As in Study 1, perceptions of leaders’ work–life balance alone did not mediate the positive relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (b = −.02, SE = .06). The confidence interval included zero (CI −.159, .081). The direct and indirect effects occurred independent of the inclusion or exclusion of control variables.

Table 5 displays estimates of the path coefficients and indirect effects along with bias-corrected 95 % confidence intervals.

Discussion

Results of Study 2 confirmed and further expanded our initial findings. First, the experimental design allowed us to draw causal inferences about the positive impact of authentic leadership on all three dependent variables: participants in the high authentic leadership condition indicated more positive perceptions of leaders’ work–life balance, and followers’ work–life balance and job satisfaction than participants in both low authentic leadership and neutral control conditions. Furthermore, calculation of the crossover model confirmed the proposed indirect relations. As in the first study, results highlighted the primary relevance of followers’ own work–life balance as a mediator between authentic leadership and job satisfaction. Finally, the experimental study design allowed a more focused view of the variables of interest, and results confirmed the proposed direct effect of authentic leadership on followers’ job satisfaction.

General Discussion

We designed this research to explore authentic leadership at the work–life interface. Specifically, we tested a crossover model in which perceptions of leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance were assumed to mediate the relationship between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction. We applied conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2002) and the work–home resources model (ten Brummelhuis and Bakker 2012) to suggest that authentic leadership is a resource for the health and well-being of leaders and followers.

To summarize, our two studies yielded the following results. In Study 1, findings confirmed the proposed indirect relations between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction through followers’ perceptions of their leaders’ and their own work–life balance, as well as through followers’ work–life balance only. The latter indirect effect appeared to be the primary pathway from authentic leadership to followers’ job satisfaction. Moreover, results from Study 1 revealed that followers’ job involvement and leader–member exchange diluted the hypothesized direct relationship between authentic leadership and job satisfaction. Study 2 confirmed the two indirect relationships between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction through leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance in sequence, and for followers’ work–life balance only. Again, followers’ work–life balance showed a stronger mediating effect than leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance in sequence.

Contributions

With regard to theoretical contributions, we provide initial empirical evidence supporting earlier theoretical claims to link authentic leadership and followers’ well-being (Ilies et al. 2005), namely their perceived work–life balance and job satisfaction. The contribution of this research lies also within the application of conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2002) and the work–home resources model (ten Brummelhuis and Bakker 2012), indicating authentic leadership as an external resource for followers’ health and well-being. It appears that authentic leaders create conditions under which leaders and followers are seen as authentically balancing demands from their professional and private life domains. Thus, the findings from this research concur with the view that authentic leadership creates the conditions for authentic followership (Leroy et al. 2012a). This research also corresponds to the finding that authentic leaders build positive, trusting relations with their followers and therefore influence followers’ attitudes and behaviors (Wang et al. 2014). Importantly, our research goes beyond earlier studies of authentic leadership and negative health-related measures, such as burnout (e.g., Laschinger and Fida 2014a), by taking the positive side of health and well-being into consideration.

Regarding crossover research, our approach contributes to the broadened scope of this important field of inquiry to include top-down transmission processes from leaders to followers as well as positive crossover (Westman 2001). In line with earlier findings, our research supports the notion that positive emotions and behaviors can be inter-individually transmitted (Bakker and Demerouti 2009; Bakker et al. 2009), and that leaders play an important role in the crossover process (Carlson et al. 2011; Koch and Binnewies 2015; ten Brummelhuis et al. 2014). Beyond the earlier research, our findings establish a specific leadership style, namely authentic leadership, as an antecedent to crossover (Westman et al. 2009).

Finally, while previous research demonstrated that due to persistent gender stereotypes managers view women as being more susceptible to family–work conflict than men (Hoobler et al. 2009), we did not find significant relations between participants’ sex and work–life balance perceptions. Given that these kinds of perceptions can negatively affect the extent to which women are seen as fitting their jobs and organizations, as well as ratings of women’s performance and promotability, this null result should be considered and explored further in the gender and management literature.

With regard to practical implications, the current findings underline leaders’ responsibilities as gatekeepers of organizational well-being. First, we therefore recommend systematic training and development programs covering authentic leadership. We agree that such programs should focus on self-awareness and self-regulation as the “key pillars” (Kinsler 2014, p. 92) of authentic leadership. By raising leaders’ awareness of their impact on followers’ work–life balance, the organizational culture can be shaped. Importantly, leaders must reflect their role modeling function in combining professional and private lives. That is, if leaders refrain from a positive work–life balance, they may also put their followers’ health and well-being at risk. Second, we encourage the training of authentic followership, that is, rather than relying on their leaders, followers need to learn how to express themselves authentically in leader–follower interactions and beyond. Balancing one’s professional and private roles and goals authentically could also be part of such training programs.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths of this research. The methodological approach combines field and experimental research with working adult samples, which advances previous research in several respects. First, the integration of field and experimental research designs advances the study of authentic leadership, which has largely employed cross-sectional field studies, thereby precluding insights into causal relations between authentic leadership and outcome variables of interest (Gardner et al. 2011). Second, the same holds true for the study of crossover, where hitherto published research almost exclusively relies on correlational designs, with few notable exceptions (see Bakker et al. 2007). Third, employing the two different methodological approaches together is advantageous because constraints of one approach are canceled out by the other approach. Specifically, our experimental study employs a vignette methodology, which “results in high levels of confidence regarding internal validity but is challenged by threats to external validity,” as compared to non-experimental field research, which “maximizes external validity but whose conclusions are ambiguous regarding causal relationships” (Aguinis and Bradley 2014, p. 351). The multi-method approach of our research addresses this dilemma and strengthens the validity of results. Finally, due to its strength in increasing internal validity, the complementation of field and experimental research allowed us to isolate the mechanisms of interest. Specifically, while in Study 1 followers’ involvement in their jobs and the leader–member exchange relationship seemed to dilute the empirical relations of interest, Study 2 excluded these mechanisms. Subsequent results confirmed the proposed direct effect of authentic leadership on followers’ job satisfaction.

We further introduced several control variables in this research, among them followers’ involvement in their jobs, perceptions of leader–member exchange (both Study 1), and perceptions of the leader’s competence (Study 2). With the inclusion of these variables, we address calls for improved control variable usage in organizational research to include not only demographic variables, but also additional theoretically meaningful variables that might contaminate the relations between variables of interest (Bernerth and Aguinis 2015). This approach increases the validity of our findings. While the first study suggests that job involvement and leader–member exchange are relevant variables to be considered at the work–life interface, the second study demonstrates the relations between authentic leadership, work–life balance, and job satisfaction more specifically. Thus, while job involvement and the general relationship with one’s supervisor play a role for job satisfaction (Janssen and Van Yperen 2004), this research reveals how work–life balance perceptions function as mediating mechanisms. We acknowledge that limitations must be taken into account when interpreting our results. They also provide avenues for future research. While we carefully outlined the theoretical underpinnings of this research, arguing why authentic leadership should be related to perceptions of leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance, serious criticism of the unclear boundaries between leadership style constructs in the same conceptual space has been voiced (e.g., van Knippenberg and Sitkin 2013). Several leadership styles (e.g., transformational or ethical leadership) show overlapping features with authentic leadership (Gardner et al. 2011), and thus we cannot rule out empirically that also other leadership styles impact leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance perceptions and their subsequent effects on job satisfaction. The unique relations for authentic leadership as compared to related leadership constructs require further empirical testing. The prevalence of common method variance in our data aggravates the concern outlined above. Our studies were based on single-source measurement (i.e., follower ratings), and thus positive relations may be partly evoked by this common factor. Notably, we applied statistical remedies to control method biases (Podsakoff et al. 2012), and found that a four-factor model that differentiated all study variables displayed a better fit than a one-factor model. A five-factor model with an unmeasured latent method factor proved only slightly superior to the theoretically derived four-factor model. Nevertheless, to validate our results we advise future research to take leaders’ ratings of their work–life balance into account, as well as ratings from significant others (e.g., spouses, friends) for external perceptions of work–life balance, and finally also objective measures (e.g., sick days).

Moreover, we suggest that future research examines the proposed crossover model between leaders’ and followers’ work–life balance in further detail. In line with our theoretical arguments, perceptions of authentic leaders’ work–life balance may impact followers’ work–life balance through multiple mediating mechanisms such as role modeling, relationship building, or empowerment. For example, additional field research could explore whether followers who believe their leaders have a positive work–life balance take them as role models, and as a consequence adopt specific behaviors to respond to demands in professional and private life domains. Work–life balance could also be divided into more specific constructs, such as work–life conflict and work–life enrichment (Westman 2001), impacted by authentic leadership. Furthermore, while job satisfaction is a theoretically and practically relevant outcome of authentic leadership (Giallonardo et al. 2010; Jensen and Luthans 2006; Neider and Schriesheim 2011; Peus et al. 2012b), systematic reviews point to the importance of manifold criteria to appropriately evaluate the effects of leadership in general (Hiller et al. 2011). Therefore, for the further advancement of this research, multiple outcome criteria above and beyond job satisfaction such as leaders’ and followers’ performance, organizational commitment, well-being, burnout, and physical health must be taken into consideration.

In future research endeavors, our model should also be extended from individual leader–follower relationships to team and organizational levels. It is viable to assume that through social and emotional contagion processes (Peus et al. 2012a) a general climate of authenticity can spread in organizations (Hannah et al. 2011), and that norms or standards of managing the work–life interface are set between employees at the same hierarchical levels.

Finally, we would like to encourage future research on authentic leadership and work–life balance to take leaders’ and followers’ gender into account. Gender role expectations have been shown to influence perceptions of both, authentic leadership (Monzani et al. 2014) and conflicts at the work–life interface (Hoobler et al. 2009). For example, it would be fruitful to expand our experimental study design, and to systematically vary manager gender to detect whether female managers are more likely than their male counterparts to be perceived as role models for work–life integration (e.g., conflict or enrichment; Westman, 2001).

Conclusion

Overall, this research underlines how authentic leadership represents the much-needed approach to promote health and well-being in organizations. With these findings, we hope to inspire future conceptual and empirical work strengthening the understanding of leadership styles for crossover between leaders and followers.

References

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371. doi:10.1177/1094428114547952.

Algera, P. M., & Lips-Wiersma, M. (2012). Radical authentic leadership: Co-creating the conditions under which all members of the organization can be authentic. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 118–131. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.010.

Autor, D. H., & Dorn, D. (2013). The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. The American Economic Review, 103(5), 1553–1597. doi:10.1257/aer.103.5.1553.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001.

Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 801–823. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2009). The crossover of work engagement between working couples. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(3), 220–236. doi:10.1108/02683940910939313.

Bakker, A. B., van Emmerik, H., & Euwema, M. C. (2006). Crossover of burnout and engagement in work teams. Work & Occupations, 33(4), 464–489. doi:10.1177/0730888406291310.

Bakker, A. B., Westman, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). Crossover of burnout: An experimental design. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 16(2), 220–239. doi:10.1080/13594320701218288.

Bakker, A. B., Westman, M., & van Emmerik, I. J. H. (2009). Advancements in crossover theory. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(3), 206–219. doi:10.1108/02683940910039304.

Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2009). The crossover of daily work engagement: Test of an actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1562–1571. doi:10.1037/a0017525.

Barrett, P. (2007). Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 815–824. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018.

Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2015). A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology,. doi:10.1111/peps.12103.

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Wethington, E. (1989). The contagion of stress across multiple roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(1), 175–183. doi:10.2307/352378.

Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35(5), 307–311. doi:10.1037/h0055617.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. doi:10.1177/135910457000100301.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014). Charts from the American Time Use Survey. http://www.bls.gov/tus/charts/home.htm. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

Carlson, D. S., Ferguson, M., Hunter, E., & Whitten, D. (2012). Abusive supervision and work–family conflict: The path through emotional labor and burnout. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, 849–859. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.05.003.

Carlson, D. S., Ferguson, M., Kacmar, K. M., Grzywacz, J. G., & Whitten, D. (2011). Pay it forward: The positive crossover effects of supervisor work–family enrichment. Journal of Management, 37(3), 770–789. doi:10.1177/0149206310363613.

Chang, A., McDonald, P., & Burton, P. (2010). Methodological choices in work–life balance research 1987 to 2006: A critical review. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(13), 2381–2413. doi:10.1080/09585192.2010.516592.

Cianci, A. M., Hannah, S. T., Roberts, R. P., & Tsakumis, G. T. (2014). The effects of authentic leadership on followers’ ethical decision making in the face of temptation: An experimental study. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(3), 581–594. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.12.001.

Clapp-Smith, R., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Avey, J. B. (2009). Authentic leadership and positive psychological capital: The mediating role of trust at the group level of analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 15(3), 227–240. doi:10.1177/1548051808326596.

Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C. W., & van der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2012). Work–family interface from a life and career stage perspective: The role of demands and resources. International Journal of Psychology, 47(4), 241–258. doi:10.1080/00207594.2012.699055.

DiRenzo, M. S., Greenhaus, J. H., & Weer, C. H. (2011). Job level, demands, and resources as antecedents of work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78(2), 305–314. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.10.002.

Fleetwood, S. (2007). Why work–life balance now? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(3), 387–400. doi:10.1080/09585190601167441.

Freeman, R. E., & Auster, E. R. (2011). Values, authenticity, and responsible leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 15–23. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1022-7.

Gallup (2014). Gallup Engagement Index. http://www.gallup.com/strategicconsulting/158162/gallup-engagement-index.aspx. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumbwa, F. (2005). “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 343–372. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.003.

Gardner, W. L., Cogliser, C. C., Davis, K. M., & Dickens, M. P. (2011). Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1120–1145. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.09.007.

Giallonardo, L. M., Wong, C. A., & Iwasiw, C. L. (2010). Authentic leadership of preceptors: Predictor of new graduate nurses’ work engagement and job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(8), 993–1003. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01126.x.

Goffin, R. D. (2007). Assessing the adequacy of structural equation models: Golden rules and editorial policies. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 831–839. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.019.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5.

Haar, J. M., Russo, M., Suñe, A., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2014). Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 361–373. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.010.

Hannah, S. T., Walumbwa, F. O., & Fry, L. W. (2011). Leadership in action teams: Team leader and members’ authenticity, authenticity strength, and team outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 64(3), 771–802.

Harter, S. (2002). Authenticity. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 382–394). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hassan, A., & Ahmed, F. (2011). Authentic leadership, trust and work engagement. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, 6(3), 164–170.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hiller, N. J., DeChurch, L. A., Murase, T., & Doty, D. (2011). Searching for outcomes of leadership: A 25-year review. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1137–1177. doi:10.1177/0149206310393520.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307.

Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Lemmon, G. (2009). Bosses’ perceptions of family-work conflict and women’s promotability: Glass ceiling effects. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 939–957. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2009.44633700.

Hsiung, H.-H. (2012). Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: A multi-level psychological process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 349–361. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1043-2.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Ilies, R., Morgeson, F. P., & Nahrgang, J. D. (2005). Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader-follower outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 373–394. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.002.

Janssen, O., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2004). Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 368–384. doi:10.2307/20159587.

Jensen, S. M., & Luthans, F. (2006). Entrepreneurs as authentic leaders: Impact on employees’ attitudes. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(8), 646–666. doi:10.1108/01437730610709273.

Jones, F., Burke, R. J., & Westman, M. (2006). Work–life balance: Key issues. In F. Jones, R. J. Burke, & M. Westman (Eds.), Work–life balance. A psychological perspective (pp. 1–9). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Judge, T. A., & Watanabe, S. (1993). Another look at the job satisfaction-life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(6), 939–948. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.6.939.