Abstract

Guilt is a powerful emotion that is known to influence ethical decision-making. Nevertheless, the role of guilt cognitions in influencing restorative behaviour following an unethical action is not well understood. Guilt cognitions are interrelated beliefs about an individual’s role in a negative event. We experimentally investigate the joint impact of three guilt cognitions—responsibility for a decision, justification for a decision, and foreseeability of consequences—on a taxpayer’s decision to make a tax amnesty disclosure. Tax amnesties encourage delinquent taxpayers to self-correct to avoid severe penalties that would result if their tax evasion were discovered. Our findings suggest a three-way interaction effect such that taxpayers are likely to make tax amnesty disclosures when they foresee that they will be caught by the tax authority, unless they can diffuse responsibility for their evasion and justify their evasion. Implications for tax policy and tax professionals are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The worldwide cost of taxpayer non-compliance is staggering. For example, the estimated ‘tax gap’ due to underreported taxable income is $450 billion in the United States (Internal Revenue Service 2011) and $80 billion in Canada (Canadians for Tax Fairness 2014). Thus, there is considerable interest and practical importance associated with knowing how to encourage taxpayers’ voluntary compliance.

Tax compliance research tends to examine factors that can increase tax adherence and prevent tax evasion. Tax compliance consists of correctly reporting all items of income and deductions as mandated by law, whereas tax evasion is the intentional disregard of tax laws (Slemrod 2007). Typically, sanctions and penalties are used to prevent tax evasion, and while effective, this deterrence approach is very costly, resulting in significant reliance on voluntary reporting. Consequently, tax authorities are interested in cost-effective procedures to improve compliance. Tax amnesties, which are synonymous with voluntary disclosure programmes, are relatively low-cost compliance initiatives in which taxpayers are given the opportunity to self-correct errors on previously filed tax returns. By self-correcting, taxpayers pay the taxes that would have resulted had the amounts been correctly reported, but often avoid the penalties and/or sanctions that would have been imposed if the tax authority had discovered the errors.

Tax authorities are increasingly turning to tax amnesties as a way to increase tax revenues. Since 2000, more than half of the U.S. states have offered tax amnesty programmes one or more times (Weinreb 2009). In the past 50 years, many developed countries (e.g. Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) and developing countries (e.g. Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, India, Philippines, and Turkey) have offered tax amnesties in response to economic problems such as recessions or public debt (Baer and Le Borgne 2008; Torgler and Schaltegger 2005a). Although empirical studies have addressed two main ways that amnesties can affect tax revenue collected—direct gains from participation in the amnesty (Alm and Beck 1991; Fisher et al. 1989; Hasseldine 1998), and indirect effects on tax compliance following an amnesty (Alm et al. 1990; Alm and Beck 1993; Andreoni 1991; Christian et al. 2002; Luna et al. 2006; Malik and Schwab 1991; Marceau and Mongrain 2000; Torgler and Schaltegger 2005b)—these economics-based studies suggest that tax amnesties are not particularly effective at encouraging participation in tax amnesties, and net revenue gains from amnesty programmes are only modest at best. For example, Hasseldine (1998) analysed a number of state tax amnesties in the United States, and found that amnesty revenues range from just 0.008 to 2 % of state tax revenues. Consequently, by better understanding how to encourage greater participation in tax amnesties, tax authorities may be able to increase tax revenues collected from amnesties, and improve subsequent compliance.

Much remains to be learned about the phenomenon of self-correcting in the tax context. In particular, prior literature has not explicitly considered the underlying impetus for an individual’s decision to make a tax amnesty disclosure. A better understanding of taxpayers’ motivations in amnesty situations has the potential to inform and improve amnesty policy, and perhaps increase the effectiveness of tax amnesty programmes. Since taxpayers make decisions for economic and non-economic reasons (Coricelli et al. 2010; Maciejovsky et al. 2012), perhaps tax amnesty programmes would be more effective if tax authorities considered appeals to a non-economic factor, such as guilt.

In this study, we examine the role of guilt as an intrinsic motive that may encourage participation in tax amnesties. Guilt is a moral emotion (Tangney et al. 2007) that we expect will have a powerful impact on tax amnesty decisions, since guilt is known to influence both ethical decision-making (Steenhaut and Van Kenhove 2006) and reparative behaviour (Ghorbani et al. 2013; Ilies et al. 2013). Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to investigate the role of guilt in motivating an individual’s tax amnesty decision.

Guilt is an agitation-based emotion of regretting a wrong decision or action (Ferguson and Stegge 1998). Guilt occurs in response to an actual or imagined moral transgression (Dulleck et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2002). When people feel guilty, they perceive their actions as wrong, assume responsibility for their decisions, and desire to find ways to either undo the wrongs or punish themselves (Eisenberg 2000). In a tax setting, this suggests that an individual who evaded taxes, and felt guilty about doing so, may be motivated to voluntarily disclose the error as a means of assuming responsibility and atoning for the transgression.Footnote 1

We used an experimental approach to investigate how guilt influences a taxpayer’s decision to make a tax amnesty disclosure. An experiment is able to manipulate the relevant factors of interest while controlling for other factors that are outside of the scope of the study. Kubany and Watson (2003) developed a multidimensional model of guilt cognitions. Guilt cognitions are interrelated beliefs about an individual’s role in a negative event. We conducted an experiment on 239 Canadian taxpayers to examine how three guilt cognitions—responsibility for a decision, justification for a decision, and foreseeability of consequences—jointly influence tax amnesty decisions. A strength of the study is that our participants were adult taxpayers, rather than students, which increases the reliability of our findings.

Participants were given a scenario in which a taxpayer, who was given an inheritance, transferred the proceeds to a bank account in the Cayman Islands, unbeknownst to the tax authority. The taxpayer never reported any of her subsequent investment income on her tax return. After manipulating responsibility, justification, and foreseeability, we asked participants whether they thought that the taxpayer would make a tax amnesty disclosure. Our results show an interactive effect of the three guilt cognitions, such that taxpayers are more likely to make tax amnesty disclosures once they foresee that they will be caught, unless they can justify their tax evasions and diffuse responsibility for their behaviour by blaming tax advisors.

Our results suggest practical implications for tax authorities, as well as tax and other financial professionals. Appealing to taxpayers’ guilt through efforts to increase the foreseeability of the possible negative consequences of tax evasion may be a promising strategy in encouraging non-compliers to self-correct. Tax and other financial professionals could emphasize legal and ethical reporting options to their non-compliant clients, which should result in a greater likelihood of them making a tax amnesty disclosure. Also, since our results suggest that taxpayers can diffuse personal responsibility for unethical reporting just by hearing an unethical inference from a tax advisor, tax advisors should be prudent when discussing tax reporting options.

Several contributions emerge from our study. First, we find causal evidence that appeals to guilt are effective in increasing the likelihood that taxpayers will make tax amnesty disclosures. We therefore contribute to the tax compliance literature by demonstrating the importance of guilt in encouraging tax compliance. Prior tax research (Cho et al. 1996; Coricelli et al. 2010; Dulleck et al. 2012; Erard and Feinstein 1994a; Grasmick and Scott 1982) has not directly examined the direct relation between guilt and compliance. Furthermore, these tax research scholars conceptualize guilt rather broadly, without considering the nuances of this construct. Therefore, our second contribution is that we provide empirical support for Kubany and Watson’s (2003) multidimensional model of guilt by showing that responsibility, justification, and foreseeability interact to influence restorative behaviour. In so doing, we advance the theoretical understanding of guilt in the tax literature. Thirdly, we contribute to the restorative justice literature by finding that voluntary disclosures, which are a form of restorative behaviour (Wenzel et al. 2008), are directly influenced by appeals to guilt.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we formulate our hypothesis. Section three describes our experiment, and section four reports our results. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of our findings for tax policy makers, tax or other financial professionals, and tax ethics researchers.

Hypothesis Development

Tax researchers have generally found a positive association between tax amnesty programmes and subsequent compliance (Alm et al. 1990; Alm and Beck 1993; Christian et al. 2002; Fisher et al. 1989; Luna et al. 2006; Torgler and Schaltegger 2005b). These economics-based studies implicitly assume that a taxpayer’s motivation for making a tax amnesty disclosure arises as a result of a cost–benefit analysis. However, there is evidence that taxpayers are also motivated by non-economic reasons when making compliance decisions (Alm and Torgler 2011; Baldry 1986). Coricelli et al. (2010) find that there is an emotional cost to tax evasion, such that emotional arousal increases when tax evasion is initially detected. Schwartz and Orleans (1967) find that moral suasion has a stronger impact on compliance than threats of punishment, and Smith and Stalans (1991) argue that positive emotional incentives by the taxing authority are more effective at encouraging tax compliance than are financial incentives.

Overall, this discussion suggests that models that focus only on economic motivations are inadequate at explaining taxpayer behaviour. Consequently, tax ethics researchers have concluded that tax ethics requires a multifaceted policy approach that includes cognitive and affective aspects of human behaviour (Coricelli et al. 2010; Maciejovsky et al. 2012). Accordingly, we use three guilt cognitions to explain tax amnesty behaviour.

Several tax studies consider guilt to be an important motivating factor in influencing tax decision-making. Grasmick and Scott (1982) found that of sanctions, social stigma, and guilt feelings, the deterrence mechanism with the greatest inhibitory effect on non-compliance was guilt feelings. Erard and Feinstein (1994a) develop a model of tax compliance that includes guilt, and suggest that guilt can bias taxpayer perceptions of audit probability. Cho et al. (1996) suggest that the ‘psychic costs’ of tax evasion may be high enough to prevent any economic gains from tax evasion. Similarly, Dulleck et al. (2012) found a positive correlation between psychic stress and tax compliance, and discovered that psychic stress outweighed the excitement of possible gains from tax evasion. Coricelli et al. (2010) suggest that guilt may be high if taxpayers are non-compliant and are audited. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the direct relationship between guilt and tax amnesty disclosures.

Furthermore, the theoretical basis for guilt in the five studies cited above is minimal, and the measurement of guilt is very basic. Cho et al. (1996), Dulleck et al. (2012), and Coricelli et al. (2010) suggest that guilt may be a ‘psychic cost’, ‘psychic stressor’, or ‘emotion’, respectively, without actually measuring guilt. Grasmick and Scott (1982, p. 218) measure guilt by asking respondents if they thought tax evasion was “always wrong, usually wrong, sometimes wrong, seldom wrong, or never wrong”, whereas Erard and Feinstein (1994a) measure guilt with a single parameter in an economic model. None of these studies have a theoretical model of guilt, and none has a comprehensive measurement of guilt. Thus, tax compliance literature on guilt lacks a rigorous theoretical basis, despite the fact that guilt is a multifaceted construct (Kubany and Watson 2003) and is much more nuanced than presented in these studies.

There appears to be a similar trend in the broader ethical decision-making literature, where studies that examine guilt tend to use a simple definition rather than a theoretically based construct (e.g. Brockner et al. 1986; Ghorbani et al. 2013; Maitlis and Ozcelik 2004). We were able to find just one study (Bohns and Flynn 2013) in which antecedents to guilt were considered. They suggest that there are three broad categories of guilt antecedents: perceptions of control, context specificity, and negative outcomes for others. However, Bohns and Flynn (2013) is not an empirical study, and since these three categories were formulated when distinguishing guilt from shame, as such it is not specific to guilt. Thus, our review of the broader ethical decision-making literature suggests that, similar to the tax compliance literature, research on guilt is limited by a lack of theoretical rigour.

Tax researchers explicitly acknowledge that the tax compliance literature lacks a theoretically robust model of guilt (Alm 2012). Consequently, we adopt insights from Kubany and Watson’s (2003) multidimensional model since it is, to the best of our knowledge, the most comprehensive model of guilt. Kubany and Watson (2003) state that theoretical discussions of guilt tend to be brief, that there is no consensus about the determinants of guilt, and that there has been little effort to test competing conceptualizations of guilt. Accordingly, their model was developed to address these shortcomings. Although their model has not yet received empirical support, it appears relevant for this study, since it was formulated to account for guilt that occurs in response to common guilt-evoking events.

Kubany and Watson (2003) propose that guilt is a function of five factors: distress, responsibility for a decision, justification for a decision, foreseeability of the consequences arising from a decision, and personal values. In order for guilt to be perceived, there must be distress (unpleasant feelings associated with a negative outcome), as well as cognitions that the individual played a role in the negative outcome. Thus, guilt would be highest when an individual is distressed, takes full responsibility for causing the negative outcome, cannot justify the decision, foresaw the negative consequences arising from the decision, and the act violated the individual’s personal values. Kubany and Watson (2003) suggest that any social circumstance that produces distress and heightens the likelihood that an individual will perceive himself or herself as playing a role in a negative event is expected to heighten the probability of guilt. When extended to the tax context, it follows that a taxpayer who has committed tax evasion will be distressed, and is likely to experience guilt if she takes full responsibility for her choice to evade, cannot justify the decision to evade, foresaw that the evasion would be detected, and the act violated her personal values.

This study focuses on three guilt cognitions: responsibility for a decision, justification for a decision, and foreseeability of the possible consequences.Footnote 2 These three cognitions are likely to be relevant for taxpayer decision-making, since a taxpayer assumes a degree of responsibility for his or her tax reporting decision, has to be able to justify a tax reporting decision, and understands the possible negative consequences of an inaccurate tax reporting decision. There is also empirical evidence for the influence of each of responsibility, justification, and foreseeability on individual behaviour. For example, Curtis (2006) found a significant and positive main effect of personal responsibility on personal reporting intentions in a public accounting context. There is also a broad psychology literature showing that personal responsibility assumed for one’s behaviour affects behavioural outcomes for a variety of situations (Mulilis et al. 2001). Shalvi et al. (2011) found that the degree of lying depends on the extent to which self-justifications are available: the greater the degree of justification, the greater the incidence of lying. Crawford et al. (1990) found that higher foreseeability was significantly associated with rape victim blaming, while Lagnado and Channon (2008) found a strong influence of foreseeability on blameworthy behaviour, such that actions that were foreseeable were more likely to be considered blameable.

Although researchers have found that each of responsibility, justification, and foreseeability influences behaviour, we are unaware of any empirical studies that have investigated the joint effect of these three factors. Kubany and Watson’s (2003) model of guilt predicts that these three guilt cognitions will jointly influence behaviour. Consequently, we predict an interaction effect of responsibility, justification, and foreseeability on tax amnesty disclosure decisions.

Hypothesis

Responsibility, justification, and foreseeability will jointly influence the likelihood of making a tax amnesty disclosure.

We do not specify the form of an interaction because Kubany and Watson’s (2003) model does not predict the form of an interaction.Footnote 3

Methodology

Design

We employ a 2 (responsibility for the decision: high, low) × 2 (justification of the decision: high, low) × 2 (foreseeability of the consequences: high, low) fully crossed between-subject design.

Participants

Participants were Canadian taxpayers recruited from a consumer research firm that has a database of 200,000 Canadians. To be representative of a typical taxpayer population, we requested our participants be randomly selected using two parameters: gender and age. We restricted our sample participants to taxpayers between the ages of 25–80, evenly distributed across age groups, with a 50/50 gender split. All participants were from the same province (Ontario). A total of 10,166 invitations were sent out in the summer of 2014, and after we received 254 responses we terminated the data collection. Fifteen of these responses contained missing data, leaving us with 239 responses. Demographic data are reported in Table 1.

Experimental Procedures

Potential participants received an email invitation from the consumer research firm to participate in a questionnaire about income taxes. Individuals willing to participate in the experiment clicked on a web link and were automatically directed to one of the experimental conditions. Participants had a unique user ID and password provided by the firm, which ensured that they could not respond to the survey more than once. Participants were incentivized using a point system specific to the firm. After random assignment to experimental conditions, participants in all conditions read an experimental scenario.

We manipulated conditions within a hypothetical scenario or vignette. Vignettes are commonly used in experimental research, since they provide selective, concrete information that is systematically varied to create conditions of high internal validity (Hughes and Huby 2004). The use of vignettes is also an important way to minimize social desirability bias in sensitive contexts (Hughes and Huby 2004). Since prior research has not manipulated guilt cognitions, nor has previous experimental tax research investigated tax amnesty decision-making, we followed the suggestions outlined in Hughes and Huby (2004) and Weber (1992) when constructing the scenario. For instance, as explained below, participants were given background information to familiarize themselves with tax amnesties, and we chose an international context with offshore bank accounts to create relevance.

The scenario described a taxpayer named Mary who received a large inheritance, transferred the proceeds to a bank account in the Cayman Islands, but did not report the subsequent taxable investment income to the tax authority. We chose an international context with offshore bank accounts to enhance realism, given the recent efforts of various governments to publicly address the problem of international tax evasion (OECD 2015). In Canada, as in other countries, taxpayers must report their worldwide income from all sources on their annual tax return. Consequently, the taxpayer in the scenario was required by law to report her offshore income.

In the experiment, participants read background information about the Voluntary Disclosure Program offered by the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). They learned that under this programme, a taxpayer could correct a previous error, would still have to pay income tax on the previously unreported amount, plus interest, but would neither be penalized nor prosecuted. Participants were also informed that if the CRA discovered the error before the taxpayer made a tax amnesty disclosure, the consequences would be more severe: in addition to the income taxes and interest owed, there would be penalties, and the taxpayer could be jailed if the error was intentional. Participants then read the second part of the scenario, which included the three manipulations about responsibility for tax reporting, justification for not reporting the taxable income, and foreseeability of the possible negative consequences for not reporting the taxable income. They also answered follow-up manipulation check questions and demographic questions. The wording for all experimental manipulations is contained in Appendix.

Dependent Variable

Our primary dependent measure was whether participants thought that Mary would make an amnesty disclosure (yes or no) about the previously unreported taxable investment income that she earned in the Cayman Islands. We used a binary dependent variable, consistent with past tax amnesty studies (Alm et al. 1990; Christian et al. 2002; Marceau and Mongrain 2000). Because taxation is a socially sensitive topic, and in order to minimize the effects of social desirability bias (Hughes and Huby 2004), participants responded to questions about Mary rather than about themselves.

Independent Variables

There are three independent variables: responsibility for the decision, justification for the decision, and foreseeability of consequences. We operationalized responsibility according to the extent to which Mary was influenced by an external source, consistent with Zhang et al. (2009), and notwithstanding the fact that Mary is ultimately answerable for her tax reporting choice. In the high responsibility condition, Mary never consulted with external sources regarding her initial tax reporting decision, whereas in the low responsibility condition, a tax advisor provided insights that Mary considered when making her initial tax reporting decision. We operationalized justification according to whether Mary had a viable or a poor reason for not reporting the investment income, following Haines and Jost (2000). In the high justification condition, Mary used the cash that would have been paid in taxes to purchase cancer medication for her young daughter, whereas in the low justification condition she made renovations to her house. We operationalized foreseeability as the degree to which Mary anticipated negative consequences from her decision (Griffin et al. 1996) based on her expectation of being caught by the CRA. In the high foreseeability condition, Mary learned that the CRA was working on an information sharing agreement with the Cayman Islands bank so that the CRA would obtain the names of all Canadian investors. In the low foreseeability condition, Mary learned that it would be virtually impossible for the CRA to obtain information about Canadians who had investments in the Cayman Islands.

Control Variables

Kubany and Watson’s (2003) model involves five guilt factors: responsibility, justification, foreseeability, distress, and personal values. Responsibility, justification, and foreseeability were the independent variables in our model. As mentioned (in footnote 2), it was impossible for us to manipulate feelings of distress about tax evasion as well as to manipulate individual attitudes concerning the ethicality of tax evasion. Consequently, we controlled for both distress and personal values. We measured distress by asking participants to rate their level of agreement on a 7-point scale with the statement, Mary would feel distressed by what she did, consistent with Masten et al. (2011). We measured personal values by asking participants to rate their level of agreement on a 7-point scale with two statements about the morality of tax evasion, it is morally wrong to engage in tax evasion behaviour, and My close friends believe it is unethical to engage in tax evasion behaviour. We used an average score of these items in our analysis (Cronbach alpha = 0.76). These two statements were adopted from Bobek et al. (2013).

We controlled for demographic variables (age, gender, tax preparer, income, and education) consistent with Bobek et al. (2013) and Chung and Trivedi (2003). Finally, we asked whether or not the participant had ever been audited by the CRA, since a prior audit experience may have influenced the responses to the questions.

Results

Manipulation Effectiveness

We performed manipulation checks for responsibility, justification, and foreseeability of consequences. Our manipulation check for responsibility asked participants to rate their agreement with the statement, Mary has only herself to blame for not reporting the investment income. Our manipulation check for justification asked participants to rate their agreement with the statement, Mary has a good reason for not reporting the investment income. Our manipulation check for foreseeability of consequences asked participants to rate their agreement with the statement, The CRA will find out that Mary had underreported her investment income. All statements were measured with 7-point Likert scales, with ‘1’ being ‘strongly agree’ and ‘7’ being ‘strongly disagree’. Responsibility (F = 6.45, p = 0.01), justification (F = 14.80, p < 0.01), and foreseeability (F = 23.90, p < 0.01) manipulation checks were supported, and all in the expected direction.

Test of the Hypothesis

We hypothesized a three-way interaction effect of responsibility, justification and foreseeability on the likelihood of making a tax amnesty disclosure. To test our hypothesis, we used binary logistic regression analysis, since our dependent variable and independent variables are dichotomous (Jaccard 2001). We used dummy variables of ‘0’ for the ‘low’ conditions and ‘1’ for the ‘high’ conditions. We also used dummy variables of ‘0’ if the participant said that Mary would not make an amnesty disclosure and ‘1’ if the participant said that Mary would make an amnesty disclosure.

We entered all independent variables and control variables simultaneously. Following Field (2009), we first checked for multicollinearity using variance inflation factor analysis (VIF), and found no evidence of multicollinearity in the logistic regression model.Footnote 4 The model fit statistics indicated an acceptable fit to the data, given the Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic (χ 2 = 5.66, p = 0.69) was not significant (Field 2009). We also inspected the standardized residuals and deviance statistics (Cook’s distance). No standardized residuals exceeded 3, and no Cook’s distance exceeded 1, which also indicated an acceptable model fit (Field 2009). Regression results are reported in Table 2A.

Support for our hypothesis would be evidenced by a significant and positive interaction term between responsibility, justification, and foreseeability. As per Table 2A, this interaction term was positive and significant (p = 0.03). Consequently, our hypothesis was supported. Responsibility, justification, and foreseeability jointly influence the likelihood of making a tax amnesty disclosure.

The independent variables—responsibility, justification, and foreseeability—were, respectively, not significant (p = 0.28), marginally significant (p = 0.07), and statistically significant (p = 0.03) in the full model. However, we are unable to interpret these results because there was a statistically significant three-way interaction among these variables. According to Maxwell and Delaney (2004, p. 376), “When a significant three-way interaction is obtained, it is generally preferable to consider effects within such individual levels of other factors instead of interpreting the main effects themselves”. Therefore, we only analysed the predicted interaction.

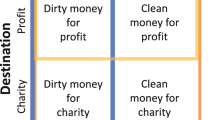

Second-Stage Analysis

To interpret the significant three-way interaction, we followed the approach suggested by Jaccard (2001). First, we specified a focal independent variable, foreseeability, since it was the only statistically significant main effect (p = 0.03 per Table 2). We then identify a first-order moderator variable. The significant two-way interaction was between foreseeability and justification (p = 0.02 per Table 2). Therefore, justification became the first-order moderator variable. The remaining independent variable (responsibility) became the second-order moderator variable. Using this classification of focal independent variable, first-order moderator variable, and second-order moderator variable, we graphed the interaction. The graph of the interaction is presented in Fig. 1. We also tabulated results from a statistical analysis in Table 3, in which we show the probabilities of making an amnesty disclosure, as well as the odds ratios of making a tax amnesty disclosure, across experimental conditions.

Results from the graph indicated that, in general, participants thought that a taxpayer was more likely to make a tax amnesty disclosure if the taxpayer foresaw that she would be caught by the tax authority. This trend was consistent across all experimental conditions, except for the high justification, low responsibility condition, in which the likelihood of making a voluntary disclosure actually decreased as the experimental conditions moved from low foreseeability to high foreseeability.

Sensitivity Analysis

To check the robustness of our results, we ran the regression without any control variables. The results of this regression are reported in Table 2B. The three-way interaction term remains significant (p = 0.04). We also ran the regression with distress and personal values as the only control variables (not tabulated), since Kubany and Watson’s (2003) model has five factors (the three independent variables, plus distress and personal values). The three-way interaction term was again significant (p = 0.03). These sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of our results.

Discussion of Results

Participants were most likely to say that Mary would make an amnesty disclosure when she foresaw that the tax authority was likely to detect her tax evasion, when she assumed sole responsibility for her tax reporting decision, and when she had a good justification for her erroneous tax reporting decision. As per Table 3, the odds ratio in this condition was 1.81, which meant that for every 100 individuals who said that Mary would not make an amnesty disclosure, 181 said that Mary would make an amnesty disclosure. Results also showed that participants were least likely to say that Mary would make an amnesty disclosure when she did not foresee that the tax authority was likely to detect her tax evasion, when she did not assume full responsibility for her tax reporting decision, and when she had a poor justification for her erroneous tax reporting decision. The odds ratio in this condition was 0.161, which meant that for every 100 individuals who said that Mary would not make an amnesty disclosure, only 16 said she would make a disclosure. Thus, the highest probability of amnesty disclosures occurred when each of the three guilt cognitions were high, and the lowest probability of amnesty disclosures occurred when each of the three guilt cognitions were low.

The trend from the graph was upward sloping in three of the four conditions of justification and responsibility (the high justification and low responsibility condition being the exception). Thus, as Mary moved from low to high foreseeability, even if she could not justify her tax evasion, and irrespective of her perceived responsibility, participants said that the probability of her making an amnesty disclosure increased. Also, as Mary moved from low to high foreseeability, even if she could justify her tax evasion and took sole responsibility for her tax reporting decisions, participants said that the likelihood of her making an amnesty disclosure increased. However, when Mary moved from low to high foreseeability, and she could justify her tax evasion but did not accept full responsibility for her erroneous tax reporting, participants said that the probability of her making an amnesty disclosure decreased. Specifically, the odds ratio in the low foreseeability, high justification, and low responsibility condition was 0.522, whereas the odds ratio in the high foreseeability, high justification, and low responsibility condition was 0.291. Thus, participants were about half as likely to say that Mary would make an amnesty disclosure if she thought that her tax evasion would be detected.Footnote 5

Implications

Tax ethics researchers have not examined the impact of affective aspects of human behaviour, such as guilt, on tax amnesties, despite suggestions that guilt feelings can motivate taxpayer decision-making (Alm 2012; Cho et al. 1996; Grasmick and Scott 1982; Hasseldine 1998). Our study extends prior tax compliance research by predicting and finding a positive relation between guilt cognitions and taxpayers’ amnesty disclosure decisions. Furthermore, unlike many studies that used students, our respondents were adult taxpayers, which strengthens the reliability of our findings. We find an interactive impact of three guilt cognitions—responsibility for a decision, justification for a decision, and foreseeability of consequences—on restorative behaviour following a transgression. We also provide partial empirical support for Kubany and Watson’s (2003) multidimensional model of guilt, since we find that three guilt cognitions act in tandem to influence behaviour. Finally, our research makes a contribution to the restorative justice literature.

Retributive justice tends to focus on punishment, whereas restorative justice involves a bilateral process that reaffirms shared values (Wenzel et al. 2008). “Restorative justice involves repairing and restoring relationships damaged through unethical behavior, focusing in particular on actions taken by offenders to make amends” (Goodstein and Butterfield 2010, pp. 453–454). Specifically, restorative justice involves “having offenders (a) accept responsibility and accountability, (b) engage in respectful dialogue with those affected by the wrongdoing, (c) feel remorse, and (d) offer apologies and/or restitution” (Goodstein and Butterfield 2010, p. 456). In a tax amnesty programme, the offending taxpayer feels remorse and guilt, accepts responsibility for engaging in the tax evasion, and makes restitution by paying the taxes on the previously unreported taxable income. Thus, tax amnesty programmes help re-establish a taxpayer–tax authority relationship that has been damaged through tax evasion. Even though we make no comment on whether or not the dialogue with the tax authority is respectful, it appears, nevertheless, that guilt cognitions may be effective at encouraging restorative justice.

Tax evasion is both an ethical issue (Baldry 1986) as well as an emotional one (Mason and Calvin 1984), from the viewpoint of both tax evaders and compliant taxpayers. From the compliant taxpayers’ perspective, there is a perceived social norm concerning fairness such that taxpayers have a strong negative emotional response to tax evaders; they think that they should be punished (Lévy-Garboua et al. 2009). For the evader, Coricelli et al. (2010) find that emotional arousal increases, from a feeling of guilt when the evasion is detected by the tax authority, to a feeling of shame when the tax evasion is made public. There are a variety of reasons why people engage in tax evasion: perceptions that tax rates are too high; beliefs that the government wastes tax dollars; and participation in the underground economy (Molero and Pujol 2012). While we expect cheating and amnesty disclosure decisions to have similar motivations, we find that not making an amnesty disclosure is related to a strong justification for cheating in the first place, which is contrary to what we expected. Instead, the participants thought that the likelihood of making a tax amnesty disclosure would increase when the taxpayer could justify the evasion. This suggests that justification may interact differently than expected when combined with responsibility and foreseeability, perhaps because of the emotional nature of justification. We leave it to future researchers to examine in more detail the impact of an emotional justification on tax evasion.

Economics-based research suggests that tax amnesty programmes have minimal effects on improving tax revenue collection, and will not influence the majority of tax evaders to come forward (Alm et al. 1990; Alm and Beck 1991, 1993; Andreoni 1991; Christian et al. 2002; Fisher et al. 1989; Luna et al. 2006; Malik and Schwab 1991; Marceau and Mongrain 2000; Torgler and Schaltegger 2005b). Therefore, it is important for tax amnesty policy makers to consider additional ways to motivate delinquent taxpayers to self-correct. Some researchers have suggested that appeals to emotions may be more effective at securing compliance than simply using sanctions (Coricelli et al. 2010; Mason and Calvin 1984). Others find that taxpayers are motivated by ethical considerations, such as honesty (Erard and Feinstein 1994b), moral suasion (Schwartz and Orleans 1967), tax morale (Torgler 2007), as well as positive incentives from the taxing authority (Smith and Stalans 1991). Our results support this line of thought. Tax authorities could consider making appeals to guilt, an intrinsic motivation, in addition to extrinsic motivators such as threats and penalties. For example, when a tax amnesty is implemented, slogans could be crafted with a message that combines the three guilt cognitions in this study. Furthermore, this sort of guilt slogan could appear directly on a tax return, with very little cost, so that taxpayers who were contemplating tax evasion might have second thoughts by reading words which could invoke feelings of guilt.

Smith and Stalans (1991) argue that positive incentives offered by taxing authorities, such as respectful treatment and thank you letters, are more effective at encouraging tax compliance than are financial incentives. However, more recently, Torgler (2004, 2013) finds that positive incentives have very little impact on taxpayer behaviour. Consequently, tax authorities could consider negative pleas, such as appeals to the intrinsic motivator of guilt. Guilt messages could be promoted through marketing initiatives such as advertising campaigns, perhaps using the tax authority’s online tax return submission portal, or television. Previous tax research suggests that public service messages delivered via television are effective at influencing taxpayers’ attitudes towards compliance (Roberts 1994). Given that a fundamental problem in business is how to motivate people to do what they already know is right (Hamilton and Strutton 1994), our findings suggest that an amnesty may be a practical solution to this broad problem, especially if appeals to guilt are part of the amnesty. Guilt appeals may motivate people to ‘do the right thing’. The combination of guilt appeals and a tax amnesty programme may have the potential to be an administratively cost-effective means of increasing tax revenues.

The results may have implications for professionals who have opportunities to provide tax-related advice. In our experiment, the probability of making a tax amnesty disclosure decreased when Mary did not take personal responsibility for the initial decision to evade taxes because she learnt about the benefits of evasion from her tax advisor. Although the tax advisor never suggested that Mary engage in evasion, the advisor did mention that she would not receive any tax forms, and could save a lot of money in taxes. Thus, just by providing informal information or inferences, without providing actual advice, a tax advisor may diffuse the personal responsibility of the client for tax reporting purposes. A broader implication is that any professionals who are engaged in providing counsel and advice should refrain from mentioning the existence of unethical options, since the mere mention of a questionable alternative, even if not formally construed as advice, may be enough to diffuse the client’s personal responsibility. Professional standards could consider expanding guidance on this topic, and accounting firms and universities could emphasize the importance of personal responsibility during training.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the results from this research are specifically tested on Canadian taxpayers. Since we randomly assigned participants to conditions, we have no reason to believe that the results would not generalize to taxpayers from other countries, but we nonetheless suggest caution. Second, due to the sensitive nature of tax evasion, it is possible that participants’ responses were biased. We attempted to mitigate this concern by assuring participants of anonymity and by asking them what they thought the hypothetical taxpayer in the scenario would do, rather than what the participants themselves would do in similar circumstances. Prior research indicates that respondents project their same feelings and attitudes when asked indirect questions instead of direct questions (Fisher 1993), and that vignettes can minimize effects of social desirability bias (Hughes and Huby 2004).

Conclusion

The purpose of our study is to examine the impact of guilt on tax amnesty disclosure decisions. We find that the likelihood of a taxpayer making an amnesty disclosure is greatest when the individual assumes personal responsibility for the transgression, can justify the transgression, and can foresee the negative consequences arising from the transgression. Conversely, the likelihood of a taxpayer making an amnesty disclosure is lowest when the individual can diffuse personal responsibility for the transgression, cannot justify the transgression, and does not anticipate being caught.

Tax amnesties are administratively low-cost programmes that generate only modest amounts of tax revenue. Our results indicate that these programmes may be improved, and more taxes collected, if they are linked to guilt appeals. Guilt is a powerful emotion that may encourage delinquent taxpayers to self-correct. An emotional appeal for taxpayers to amend their previously erroneous tax returns and pay the taxes that should have been remitted may increase tax revenue.

We encourage further research on guilt cognitions and their influence on restorative behaviour in other tax and non-tax contexts. Future research could extend this study in other national tax contexts or could consider other aspects of tax amnesties. For example, does varying the incentives to make amnesty disclosures affect the incidence of voluntary disclosures? Researchers could also consider trade-offs between guilt and extrinsic motivation, or other moderating influences on guilt cognitions, such as personality traits.

Notes

Guilt and shame are the two emotions most relevant to ethical decision-making (Tangney et al. 2007). Shame is a dejection-based emotion arising from public exposure (Ferguson and Stegge 1998) and is not relevant to the tax amnesty decision, since a taxpayer who makes an amnesty disclosure is known only to a tax authority and would not be publicly exposed.

The other two aspects of guilt, in Kubany and Watson’s (2003) model, are distress and personal values. Distress is an affective state involving feelings of unhappiness, depression, and anxiety (Hardy et al., 2003) that can result in emotional exhaustion (Tepper et al. 2007). It is impossible for us to manipulate these emotional feelings in an experimental context, and so we controlled for distress in our experiment. The other guilt cognition is personal values. “A personal value system is viewed as a relatively permanent perceptual framework which shapes and influences the general nature of an individual’s behavior. Values are similar to attitudes but are ingrained, permanent, and stable in nature” (England 1967, p. 54). In a tax situation, personal values refer to beliefs about the ethics of tax evasion. Since there is variation in personal values (England 1967), it is not possible for us to operationalize these in our experiment, and so we also controlled for attitudes concerning the ethicality of tax evasion.

We do not predict main effects because main effects should not be tested if there is a significant interaction effect (Maxwell and Delaney 2004, p. 331).

For any variables, a VIF value greater than 10 may indicate multicollinearity (Field 2009). The highest VIF value in the model was 3.5, and all but two values were below 1.2.

As with any experiment, the results should be interpreted with caution. While we expect directional differences across conditions to hold in a different setting, factors unique to our scenarios may result in different magnitudes of amnesty participation.

References

Alm, J. (2012). Measuring, explaining, and controlling tax evasion: lessons from theory, experiments, and field studies. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 54–77.

Alm, J., & Beck, W. (1991). Wiping the slate clean: Individual response to state tax amnesties. Southern Economic Journal, 57(4), 1043–1053.

Alm, J., & Beck, W. (1993). Tax amnesties and compliance in the long run: A time series analysis. National Tax Journal, 46(1), 53–60.

Alm, J., McKee, M., & Beck, W. (1990). Amazing grace: Tax amnesties and compliance. National Tax Journal, 43(1), 23–37.

Alm, J., & Torgler, B. (2011). Do ethics matter? Tax compliance and morality. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(4), 635–651.

Andreoni, J. (1991). The desirability of a permanent tax amnesty. Journal of Public Economics, 45(2), 143–159.

Baer, K., & Le Borgne, E. (2008). Tax amnesties: Theory, Trends, and some alternatives. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Baldry, J. (1986). Tax evasion is not a gamble. Economics Letters, 22(1), 333–335.

Bobek, D., Hageman, A., & Kelliher, C. (2013). Analyzing the role of social norms in tax compliance behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(3), 451–468.

Bohns, V., & Flynn, F. (2013). Guilt by design: Structuring organizations to elicit guilt as an affective reaction to failure. Organizational Science, 24(4), 1157–1173.

Brockner, J., Greenberg, J., Brockner, A., Bortz, J., Davy, J., & Carter, C. (1986). Layoffs, equity theory, and work performance: Further evidence of the impact of survivor guilt. Academy of Management Journal, 29(2), 373–384.

Canadians for Tax Fairness (2014). Tackle tax havens. http://www.taxfairness.ca/action/tackle-tax-havens.

Cho, J., Linn, S., & Nakibullah, A. (1996). Tax evasion with psychic costs and penalty renegotiation. Southern Economic Journal, 63(1), 172–190.

Christian, C., Gupta, S., & Young, J. (2002). Evidence on subsequent filing from the state of Michigan’s income tax amnesty. National Tax Journal, 55(4), 703–721.

Chung, J., & Trivedi, V. (2003). The effect of friendly persuasion and gender on taxpayers’ compliance behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 47(2), 133–145.

Coricelli, G., Joffily, M., Montmarquette, C., & Villeval, M. (2010). Cheating, emotions, and rationality: An experiment on tax evasion. Experimental Economics, 13(2), 226–247.

Crawford, J., McCaul, K., Veltum, L., & Bouechko, V. (1990). Understanding attributions of victim blame for rape: Sex, violence, and foreseeability. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20(1), 1–26.

Curtis, M. (2006). Are audit-related ethical decisions dependent upon mood? Journal of Business Ethics, 68(2), 191–209.

Dulleck, U., Fooken, J., Newton, C., Ristl, A., Schaffner, M., & Torgler, B. (2012). Tax compliance and psychic costs: Behavioral experimental evidence using a physiological marker. CREMA Working Paper Series 2012–2019. http://www.crema-research.ch/papers/2012-19.pdf.

Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 665–697.

England, G. (1967). Personal value systems of American managers. Academy of Management Journal, 10(1), 53–68.

Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. (1994a). The role of moral sentiments and audit perceptions in tax compliance. Public Finance, 49(Supplement), 70–89.

Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. (1994b). Honesty and evasion in the tax compliance game. RAND Journal of Economics, 25(1), 1–19.

Ferguson, T., & Stegge, H. (1998). Measuring guilt in children: A rose by any other name still has thorns. In J. Bybee (Ed.), guilt in children (pp. 19–74). New York: Academic Press.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fisher, R. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 303–315.

Fisher, R., Goddeeris, J., & Young, J. (1989). Participation in tax amnesties: The individual income tax. National Tax Journal, 42(1), 15–27.

Ghorbani, M., Liao, Y., Çayköylü, S., & Chand, M. (2013). Guilt, shame, and reparative behavior: The effect of psychological proximity. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 311–323.

Goodstein, J., & Butterfield, K. (2010). Extending the horizon of business ethics: Restorative justice and the aftermath of unethical behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(3), 433–480.

Grasmick, H., & Scott, W. (1982). Tax evasion and mechanisms of social control: A comparison with grand and petty theft. Journal of Economic Psychology, 2(3), 213–230.

Griffin, M., Babin, B., & Attaway, J. (1996). Anticipation of injurious consumption outcomes and its impact on consumer attributions of blame. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24(4), 314–327.

Haines, E., & Jost, J. (2000). Placating the powerless: Effects of legitimate and illegitimate explanation on affect, memory, and stereotyping. Social Justice Research, 13(3), 219–236.

Hamilton, J., & Strutton, D. (1994). Two practical guidelines for resolving truth-telling problems. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(11), 899–912.

Hardy, G., Woods, D., & Wall, T. (2003). The impact of psychological distress on absence from work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 306–314.

Hasseldine, J. (1998). Tax amnesties: An international review. Bulletin for International Fiscal Documentation, 52(7), 303–310.

Hughes, R., & Huby, M. (2004). The construction and interpretation of vignettes in social research. Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 11(1), 36–51.

Ilies, R., Peng, A., Savani, K., & Dimotakis, N. (2013). Guilty and helpful: An emotion-based reparatory model of voluntary work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 1051–1059.

Internal Revenue Service (2011). Tax gap “map” tax year 2006. http://www.irs.gov/pub/newsroom/tax_gap_map_2006.pdf.

Jaccard, J. (2001). Interaction effects in logistic regression. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kubany, E., & Watson, S. (2003). Guilt: Elaboration of a multidimensional model. The Psychological Record, 53(1), 51–90.

Lagnado, D., & Channon, S. (2008). Judgments of cause and blame: The effects of intentionality and foreseeability. Cognition, 108(3), 754–770.

Lévy-Garboua, L., Masclet, D., & Montmarquette, C. (2009). A behavioral Laffer curve: Emergence of a social norm of fairness in a real effort experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 147–161.

Luna, L., Brown, M., Mantzke, R., Tower, R., & Wright, L. (2006). State tax amnesties: Forgiveness is divine—and possible profitable. State Tax Notes, 48(8), 497–511.

Maciejovsky, B., Schwarzenberger, H., & Kirchler, E. (2012). Rationality vs. emotions: The case of tax ethics and compliance. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(3), 339–350.

Maitlis, S., & Ozcelik, H. (2004). Toxic decision processes: A study of emotion and organizational decision making. Organizational Science, 15(4), 375–393.

Malik, A., & Schwab, R. (1991). The economics of tax amnesties. Journal of Public Economics, 46(1), 29–49.

Marceau, N., & Mongrain, S. (2000). Amnesties and co-operation. International Tax and Public Finance, 7(3), 259–273.

Mason, R., & Calvin, L. (1984). Public confidence and admitted tax evasion: Abstract. National Tax Journal, 37(4), 489–498.

Masten, C., Telzer, E., & Eisenberger, N. (2011). An fMRI investigation of attributing negative social treatment to racial discrimination. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(5), 1042–1051.

Maxwell, S., & Delaney, H. (2004). Designing experiments and analyzing data: A model comparison perspective (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Molero, J., & Pujol, F. (2012). Walking inside the potential tax evader’s mind: Tax morale does matter. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(2), 151–162.

Mulilis, J.-P., Duval, T., & Rombach, D. (2001). Personal responsibility for tornado preparedness: Commitment or choice? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(8), 1659–1688.

OECD (2015). Global forum on transparency and exchange of information for tax purposes. http://www.oecd.org/tax/transparency/.

Roberts, M. (1994). An experimental approach to changing taxpayers’ attitudes towards fairness and compliance via television. The Journal of the American Taxation Association, 16(1), 67–86.

Schwartz, R. D., & Orleans, S. (1967). On legal sanctions. University of Chicago Law Review, 34, 282–300.

Shalvi, S., Dana, J., Handgraaf, M., & De Dreu, C. (2011). Justified ethicality: Observing desired counterfactuals modifies ethical perceptions and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 181–190.

Slemrod, J. (2007). Cheating ourselves: The economics of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 25–48.

Smith, K., & Stalans, L. (1991). Encouraging tax compliance with positive incentives: A conceptual framework and research directions. Law and Policy, 13(1), 35–53.

Smith, R., Webster, J., Parrott, W., & Eyre, H. (2002). The role of public exposure in moral and nonmoral shame and guilt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 138–159.

Steenhaut, S., & Van Kenhove, P. (2006). The mediating role of anticipated guilt in consumers’ ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(3), 269–288.

Tangney, J., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 345–372.

Tepper, B., Moss, S., Lockhart, D., & Carr, J. (2007). Abusive supervision, upward maintenance communication, and subordinates’ psychological distress. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1169–1180.

Torgler, B. (2004). Moral suasion: An alternative tax policy strategy? Evidence from a controlled field experiment in Switzerland. Economic of Governance, 5, 235–253.

Torgler, B. (2007). Tax compliance and tax morale: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Torgler, B. (2013). A field experiment on moral suasion and tax compliance focusing on underdeclaration and overdeduction. FinanzArchiv: Zeitschrift für das Gesamte Finanzwesen, 69(4), 393–411.

Torgler, B., & Schaltegger, C. (2005a). An exploration of tax amnesties around the world with a special focus on Switzerland. Tax Notes International, 38, 1193–1203.

Torgler, B., & Schaltegger, C. (2005b). Tax amnesties and political participation. Public Finance Review, 33(3), 403–431.

Weber, J. (1992). Scenarios in business ethics research: Review, critical assessment, and recommendations. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2(2), 137–160.

Weinreb, A. (2009). Tax amnesty programs and voluntary compliance initiatives: A way to mitigate declining state revenues. The Tax Adviser, 40(6), 396–400.

Wenzel, M., Okimoto, T., Feather, N., & Platow, M. (2008). Retributive and restorative justice. Law and Human Behavior, 32(5), 375–389.

Zhang, H.-J., Zhou, L.-M., & Luo, Y.-J. (2009). The influence of responsibility on regret intensity: An ERP study. Acta Psychological Sinica, 41(5), 454–463.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Centre for Accounting Ethics, University of Waterloo. We appreciate helpful comments received from Colin Boyd, Amy Hageman, Daryl Koehn, Ioana Moca, and the two anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Scenario Screen with Manipulations

Mary is a taxpayer who lives in Ontario. Three years ago, she received a large inheritance and transferred the proceeds to a bank account in the Cayman Islands, but transferred them back to Canada this year. The CRA does not know about this bank account and these investments. The investments generated $83,400 annually. Her total annual income for each of the last 3 years was $97,500.

Responsibility Manipulation

-

High Mary researched this investment opportunity, discovered that she would not receive any tax reporting forms from the Cayman Islands, and realized that she could save a lot of money in taxes.

-

Low Mary researched this investment opportunity, learned from her tax advisor that she would not receive any tax reporting forms from the Cayman Islands, and was told by her tax advisor that she could save a lot of money in taxes.

Justification Manipulation

-

High Mary has never reported any of this investment income on her Canadian tax return because she used the cash she would have paid in taxes on this investment income to pay for experimental drugs for her 4-year-old daughter, who was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive form of cancer.

-

Low Mary has never reported any of this investment income on her Canadian tax return because she used the cash she would have paid in taxes for home renovations.

Foreseeability Manipulation

-

High Last week Mary saw a news broadcast about the importance of paying taxes. The broadcast also reported that the CRA is working on an information sharing agreement with her bank in the Cayman Islands so that the CRA could obtain the names of Canadian investors.

-

Low Last week Mary saw a news broadcast about the importance of paying taxes. The broadcast also reported that it would be virtually impossible for the CRA to obtain information about Canadians who had investments in the Cayman Islands.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dunn, P., Farrar, J. & Hausserman, C. The Influence of Guilt Cognitions on Taxpayers’ Voluntary Disclosures. J Bus Ethics 148, 689–701 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3031-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3031-z