Abstract

This paper reports on an exploratory study of the preferences of users of non-financial reporting for regulatory or voluntary approaches to integrated reporting (IR). While it is well known that companies prefer voluntary approaches to non-financial reporting, considerably less is known about the preferences of the users of non-financial information. IR is the latest development in attempts over 30 or more years to broaden organisational non-financial reporting and accountability to include the wider social and environmental impacts of business. It promises to provide a more cohesive and efficient approach to corporate reporting by bringing together financial information, operational data and sustainability information to focus only on material issues that impact an organisation’s ability to create value in the short, medium and long term. The study found more support for voluntary approaches to IR as the majority of participants thought that it was too early for regulatory reform. They suggested that IR will become the reporting norm over time if left to market forces as more and more companies adopt the IR practice. Over time IR will be perceived as a legitimate practice, where the actions of integrated reporters are seen as desirable, proper, or appropriate. While there is little appetite for regulatory reform, half of the investors support mandatory IR because, in their experience, voluntary sustainability reporting has not led to more substantive disclosures or increased the quality of reporting. There is also evidence that IR privileges financial value creation over stewardship, inhibiting IR from moving beyond a weak sustainability paradigm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper reports on an exploratory study of the preferences that users of non-financial reporting have for regulatory or voluntary approaches to integrated reporting (IR). While it is well known that companies prefer voluntary approaches to non-financial reporting (Fallan and Fallan 2009; Maltby 1997), considerably less is known about the preferences of the users of non-financial information (de Villiers and van Staden 2010).

Sustainability reporting in its various forms has attempted to address the increasing demands for non-financial reporting through increased disclosure of environmental and social performance (Simnett and Huggins 2015). Integrated reporting, the latest development in corporate reporting reform, promises to address criticisms and shortcomings of sustainability reporting.

The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) released the International <IR> Framework in December 2013, following multi-stakeholder input. The International <IR> Framework aims to simplify company reporting and improve its effectiveness by focusing on value creation “as the next step in the evolution of corporate reporting” (IIRC 2015). An integrated report communicates “how an organization’s strategy, governance, performance and prospects, in the context of its external environment, lead to the creation of value over the short, medium and long term” (IIRC 2013, p. 7). It enjoys cross-sector buy-in from global companies (e.g. Microsoft, HSBC, Nestle), standard setters [e.g. International Accounting Standards Board (IASB)], stock exchanges (e.g., Tokyo Stock Exchange Group), the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the World Economic Forum and Transparency International, and has led to legislative change in South Africa, Brazil, UK and France (Ernst and Young 2014).

The IIRC believes that integrated reporting is a more effective reporting approach because it focuses on value creation through the lens of the six capitals (financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural) rather than sustainability reporting’s focus on environmental and social impacts through the lens of stakeholder materiality (Nugent 2015). The IIRC does not propose that IR replaces sustainability reporting, but instead the aim of IR is to promote “a more cohesive and efficient approach to corporate reporting that draws on different reporting strands and communicates the full range of factors that materially affect the ability of an organization to create value over time” and to enhance “accountability and stewardship for the broad base of capitals … and promote understanding of their interdependencies” (IIRC 2013, p. 2). Nevertheless, the IIRC does expect that organisations will no longer produce “numerous, disconnected and static communications” (IIRC 2013, p. 2).

To drive universal adoption of the <IR> framework, the IIRC has developed as a quasi-regulatory body (de Villiers et al. 2014). The IIRC’s goal is for integrated reporting to become the corporate reporting norm, through voluntary mechanisms (IIRC 2013). However, there are arguments for and against mandatory (regulatory) and voluntary (self-regulation) approaches to implementing new reporting innovations. For example, the voluntary, unregulated nature of sustainability reporting has led to selective, incomplete and biased disclosure which can lead to ‘greenwash’ (Tschopp and Nastanski 2014). In addition, it can lead stakeholders to make erroneous assessments of organisations, resulting in ineffective action by firms to address escalating sustainability challenges (Cho et al. 2015a). While regulation may increase accountability of organisations to disclose their social and environmental impacts, it is argued that it only provides the minimum norms with which companies have to comply and little incentive for operating more sustainably and ethically (Thirarungrueang 2013). However, Cho et al. (2015b) argue that voluntary sustainability reporting is also not effective in going beyond minimum norms, as it is largely driven by concerns for corporate legitimacy. As a result, it fails to provide information that is relevant to financial capital providers for assessing firm value (Cho et al. 2015b) and it has not necessarily led to more substantive disclosures and accountability (Cho et al. 2015a) or increased the quality of reporting (Milne and Gray 2013). As a result, it may lead to greater levels of un-sustainability (Cho et al. 2015a; Gray 2006; Milne and Gray 2013). Hess concludes that as sustainability reports have their greatest focus on risk management and protecting the company’s reputation, sustainability reports can only operate within a “weak sustainability” paradigm that doesn’t “push corporations to radically rethink their operations (and even existence) and move towards sustainability in any meaningful way” (Hess 2014, p. 126).

With the emergence of IR as a credible solution to reporting problems (Burritt 2012) that aims to address critiques of company reporting and sustainability reporting (see Adams 2015), the aim of this paper is to explore stakeholders’ perspectives on the role of voluntary and regulatory approaches to integrated reporting in Australia. To date, research into IR has primarily focused on the preparers of integrated reports (companies), not the users of these reports (see, for e.g., Frías-Aceituno et al. 2013a, b, 2014; Higgins et al. 2014; Jensen and Berg 2012; Lodhia 2015; Stent and Dowler 2015; van Zyl 2013; Wild and van Staden 2013). A study by Stubbs and Higgins (2014) of Australian preparers of integrated reports found that the lack of standards was a major barrier to implementing IR, but there was a wariness about the desirability of regulation. This was reinforced by Robertson’s and Samy’s (2015) research that found that lack of clarity about how IR fits in with other reporting standards inhibits adoption and diffusion of IR. With the rapid development of IR public policy and organisational practices, it provides an opportunity to study the development of regulation and standards over a relatively short period of time (de Villiers et al. 2014).

We found only one study that has explored the perspectives of users of IR (investors and providers of financial capital) but not the perspectives of other relevant stakeholders (e.g., regulatory bodies, standard setters and industry associations/bodies). Atkins and Maroun (2015) explored the views of the South African institutional investment community on the first sets of integrated reports produced by companies listed on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange, while other studies have engaged with institutional investors on social and environmental reporting (SER) (see, for e.g., Atkins et al. 2015; de Villiers and van Staden 2010, 2012; Solomon et al. 2013). To address this absence of the users’ voices in the IR literature, we interviewed IR stakeholders in Australia to understand their perspectives on the role of regulatory and voluntary approaches in the adoption and spread of IR in Australia. The study offers a unique perspective by focusing on what the users of integrated reports expect from IR—especially what should be mandatory, and what is possible to be addressed through voluntary guidelines. Drawing on the insights from the users’ perspectives on regulatory reform, the paper also reflects on the potential for IR to lead to more substantive disclosures and accountability (Cho et al. 2015a).

This paper is structured as follows. The next section provides some background information on the evolution of sustainability reporting and integrated reporting. This is followed by a discussion of the literature on voluntary and mandatory approaches to sustainability reporting, which provides the theoretical lens for analysing the interview data. The lessons from the institutionalisation of the most widely utilised voluntary sustainability reporting framework, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), are discussed in this section. The paper then presents the research methods employed in the study, followed by a discussion of the research findings. The paper concludes with some reflections on the potential for IR to drive more substantive disclosures and accountability (Cho et al. 2015a), to move toward sustainability in a more meaningful way (Hess 2014).

Evolution of Sustainability Reporting and Integrated Reporting

Sustainability reporting emerged in the 1970s with an emphasis on social reports primarily from the USA and Western Europe (Fifka 2013; Kolk 2010). During the 1980s, there was a focus on environmental reports, with adoption of sustainability reporting by large multinational corporations (MNCs) accelerating in the 1990s. Early voluntary SER was more narrative in nature, focusing on selected environmental, community, and employee matters within the conventional annual report to shareholders (Milne and Gray 2013) and many of the early efforts failed due to the lack of common standards for content, measurement, and reporting format (Tschopp and Nastanski 2014). Separate, ‘stand-alone’, reports appeared during the 1990s. Since then, this type of reporting has steadily increased in most countries, mainly issued by large organisations in high environmental impact industries (such as chemicals, pulp and paper, utilities and mining) and more recently, large financial services organisations (such as banks and insurance) (Milne and Gray 2013). The rapid uptake of sustainability reporting has spurred a substantial body of research into sustainability disclosure and reporting (Cho et al. 2015a). This body of research encompasses social and environmental accounting (SEA), SER, corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting, triple bottom line (TBL) reporting and sustainability reporting. This paper uses the term ‘sustainability reporting’ to cover these various strands of research.

The uptake of stand-alone sustainability reports has led to a dramatic increase in the breadth of social and environmental disclosure (Cho et al. 2015b), particularly in large multinational corporations (MNCs), and this is anticipated to continue to increase (Aras and Crowther 2009). KPMG’s (2013) latest survey on sustainability reporting found that 93 % of the G250 and 71 % of the N100 now issue sustainability reports, up from 50 organisations in 1992 (KPMG et al. 2010). Corporate Register (2014)—the largest repository of sustainability reports with over 57000 reports (over 7,000 per year)—anticipates thousands more reports to be published from 2017 after The European Parliament passed a mandate in 2014 for non-financial reporting for European Union companies with over 500 employees. Nevertheless, this is only a fraction of the 82,000 MNCs in the world (KPMG et al. 2010; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development 2009), and sustainability reporting remains patchy outside of the G250 and the N100 (Higgins et al. 2015; Milne and Gray 2007; Stubbs et al. 2013).

Integrated reporting is the latest development in corporate reporting reform. Previous research has identified a number of benefits of integrated reporting, such as: it transforms corporate processes (Phillips et al. 2011); it breaks down operational and reporting silos resulting in improved systems and processes (Roberts 2011); it improves decision-making about resource allocation (Frías-Aceituno et al. 2013a); and it reduces reputational risk and enables companies to make better financial and non-financial decisions (Hampton 2012). Nevertheless, the meaning of IR is still widely contested (Rowbottom and Locke 2013). A number of criticisms have been levelled at IR, including: it focuses on financial capital providers to the detriment of other key stakeholders (Cheng et al. 2014; Flower 2015); there is a potential lack of ‘holistic transparency’ and a potential for opportunistic use of information by large monopolistic companies (Frías-Aceituno et al. 2014); the subjective concept of six capitals can lead to insubstantial narratives (Cheng et al. 2014); and there are issues with the assurance aspects of integrated reporting (Burritt 2012; Cheng et al. 2014).

Flower (2015) criticises the IIRC’s International <IR> Framework for its emphasis on ‘value for investors’ and not ‘value for society’, and argues that there is no obligation on firms to report harm inflicted on entities outside the firm (such as the environment) where there is no subsequent impact on the firm. The International <IR> Framework could potentially reframe unsustainable corporate practices as sustainable (Thomson 2015). Flower (2015) concludes that the framework will have little impact on corporate reporting practice and that the IIRC has been the victim of ‘regulatory capture’ due to IIRC’s governing council, which is dominated by the accountancy profession and multinational enterprises. As a consequence, integrated reporting “runs the risk of denunciation for privileging the powerful discourse of the market … at the expense of seriously advancing social and environmental justice” (van Bommel and Rinaldi 2014, p. 1160), echoing criticisms of sustainability reporting (see Cho et al. 2015a; Hess 2014; Milne and Gray 2013). The risk that integrated reporting gets captured by investors and accountants may result in it resembling “a local agreement among the few, rather than a legitimate compromise of many” (van Bommel and Rinaldi 2014, p. 1160).

Mandatory and Voluntary Approaches to Sustainability Reporting

Although little research has been conducted on IR, the role of regulatory and voluntary approaches to sustainability reporting has been debated in the literature. This literature is used as an analytical lens to examine the perspectives of the participants in the research study (see “Findings” section).

Denmark was the first country to adopt legislation in 1995 on mandatory public environmental reporting, covering approximately 3000 companies (Tschopp and Huefner 2015). This was followed by The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Spain, although there is significant variation in the legal approach to environmental reporting across these countries (Holgaard and Jorgensen 2005). More recently, France, the UK and the European Union introduced public mandates for sustainability reporting. In the French experience, mandatory reporting had a significant impact on uptake: the number of French sustainability reporters more than doubled in the three years after its mandate.

While there has been a slow but steady increase in sustainability reporting regulation, voluntary approaches still dominate (Buhr et al. 2014). Supporters of the voluntary approach argue that businesses will produce reports to respond to their stakeholders’ requirements, to ensure their licence to operate (Maltby 1997). By being transparent about their sustainability risks, voluntary reporters better manage their sustainability risks and will perform better financially (Doane 2002). Regulation is seen as an unnecessary burden. Fallan’s and Fallan’s (2009) research found support for the voluntary approach, that companies can meet the heterogeneous requirements of their stakeholders without regulation. Nevertheless, many criticisms have been levelled at voluntary sustainability reporting, including: the ad-hoc and arbitrary nature; it risks becoming a ‘public relations’ exercise providing only ‘good news’ stories; it is difficult to compare different companies’ information; it is a tool to avoid regulation; there is a lack of enforcement and accountability; and, it leads to rhetoric as corporations continue to cause many problems to civil society (Overland 2007; Thirarungrueang 2013). Voluntary sustainability reporting is of questionable reliability as the majority of reports are not independently verified or assured (Buhr et al. 2014). Mandatory sustainability reporting can address these issues by providing a defined reporting framework that helps eliminate manipulation to only include good news. It offers a greater degree of comparability, enabling stakeholders to more easily assess performance on environmental and social performance. This will enable investors to make more informed decisions (Overland 2007). Regulation is more effective due to its accountability (Bebbington and Thy 1999; Buhr et al. 2014). While many corporations include sustainability in their corporate practices, encouraged by market and social forces, there is still no accountability for failing to do so. This strengthens the case for regulatory approaches as enforceable rules can better ensure corporate compliance with social responsibility (Thirarungrueang 2013). By increasing transparency and the accountability of organisations to their stakeholders (Bebbington and Thy 1999; Larrinaga et al. 2002), mandatory reporting can improve democratic processes (Bebbington and Thy 1999).

While there is considerable support for mandatory sustainability reporting, the idea remains contested because of the lack of enforcement mechanisms and credible report assurance practices and standards. In addition, it is feared that this may lead to a loss of the sense of ownership by reporters—the “buy-in” power—and to a loss in innovative potential (Brown et al. 2009b). It is argued that there are high costs associated with complying with regulation and the potential for ‘tick-the-box’ culture of compliance reduces the participation of corporations to the minimal level required by law (Fallan and Fallan 2009). Legislation does not effectively influence corporations to adopt more socially responsible behaviour as regulations only provide the minimum norms with which corporations have to comply and little incentive for operating more ethically. It may also lead to an antagonistic mentality which negatively affects companies’ economic performance (Overland 2007; Thirarungrueang 2013). However, Ioannou and Serafeim’s (2014) study of the impact of mandatory sustainability reporting in China, Denmark, Malaysia and South Africa found that firms not only significantly increased sustainability disclosures after regulation was introduced but they sought to improve the credibility and comparability of the disclosures through assurance. Furthermore, while regulation imposes costs on some firms, the effect of regulation was value-enhancing rather than value-destroying for companies in these countries (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2014).

The voluntary approach to sustainability reporting is preferred by business, particularly MNCs. Gray and Milne (2002) argue that business is opposed to government “interference” (the regulation of corporate reporting) because of the belief that business organisations are best left to their own devices and voluntary regimes are always more effective. However, while business supports voluntary approaches, there is some evidence that users of sustainability reporting support mandatory approaches. A survey of Australian, UK and US shareholders on environmental disclosure found that mandated environmental disclosure is the preferred approach, with accounting standards more popular with US shareholders (de Villiers and van Staden 2011). In de Villiers’ and van Staden’s (2012) New Zealand study, 58 % of active retail shareholders preferred compulsory environmental disclosures—with a stronger preference for prescription by law over accounting standards or stock exchange rules—primarily for accountability reasons. Their study of South African retail shareholders found that 81 % supported compulsory environmental disclosures, with a stronger preference for legal means and/or stock exchange rules (de Villiers and van Staden 2010).

Nevertheless, voluntary regimes are supported by international organisations and developed states who promote various voluntary corporate codes of conduct containing standards recognised in international law. They provide corporations with a guide to the common norms concerning the right approach to setting their own policies and standards. MNCs are encouraged to comply with the principles, codes and standards that guide their responsible business conduct (Thirarungrueang 2013). Where the state cannot, or will not, provide a full framework of legislation, voluntary mechanisms can control corporate behaviour (Thirarungrueang 2013). Voluntary approaches to regulation (VAR) are seen as part of a new interplay between the state, business and civil society with companies taking on voluntary (self-)regulatory functions. This approach is also referred to as civil-private regulation (Brown et al. 2009b), where civil society groups are empowered to play a more active and assertive role in corporate governance. In environmental VAR the functional division of labour between the private and the public sector is blurred and companies take on authoritative roles and regulatory functions. Companies have technical expertise or extensive financial resources for solving global environmental problems and are therefore seen to have significant regulatory capacities to become political partners (Schwindenhammer 2013). Hess (2014) refers to this arrangement as New Governance regulatory approaches (or meta-regulation) and government regulation of self-regulation (Hess 2014; Parker 2007), where corporations are given a significant amount of freedom to develop their own ways of achieving certain goals. The government takes on the role of “orchestrator”, rather than standard setter, and this encourages firms to experiment on solutions (to find best practices that can be used by other organisations, and seek continual improvement), and stakeholders provide guidance and hold the corporation accountable. However, Turner et al.’ (2006) warn that in the resource-constrained environment of the twenty-first century, this approach may not be successful. They argue that business implementation of mandatory reporting requirements are given priority over voluntary approaches and businesses must have an economic reason, or a ‘business case’, for engaging in sustainability reporting.

A report by KPMG and partners (2010) suggest that the relationship between mandatory and voluntary sustainability reporting approaches is changing—they are not mutually exclusive but are highly complementary. This approach recognises that the law has an important role in fostering the active participation in sustainability policies, whereas a voluntary approach encourages company dedication and commitment to responsible corporate behaviour where the level of legal enforcement is weak (Thirarungrueang 2013). Viewing the relationship between mandatory and voluntary approaches as complementary, the challenge for governments then becomes to determine the appropriate minimum level of mandatory requirements as questions remain about the extent to which firms would be prepared to go beyond their compliance with mandatory requirements. There is some evidence of this shift as governments are becoming more active in issuing voluntary guidelines for sustainability and environmental reporting. Many of the voluntary standards identified by KPMG and partners (2010) at the national level were issued by governments as they often prefer to use “soft measures” first before they legislate. In this sense, voluntary standards are not only complementary, but they can also be a prerequisite to introducing mandatory regulation (Thirarungrueang 2013). Nongovernmental entities, such as industry associations or other private institutions, also issue voluntary guidelines and some governments incorporate these international guidelines into their national policy instruments rather than develop their own national standards. Where a voluntary mechanism fails, government can impose regulatory measures to rectify the situation (Thirarungrueang 2013).

In fact, the issue of voluntary versus mandatory sustainability reporting requirements currently being debated was mirrored approximately 100 years ago in relation to financial reporting regulations. National governments threatened to introduce reporting regulations to encourage companies to act voluntarily. However, these threats were not taken seriously by corporations or the accounting profession, leading to the 1933 and 1934 USA Securities Acts which required increased disclosure, and audited financial statements by public companies (Tschopp and Nastanski 2014). Tschopp and Huefner (2015, p. 565) suggest that while financial reporting is now a “comparable and reliable market-based resource”, sustainability reporting is still in its infancy. The ‘defining’ moments that reinforced the growth and development of financial reporting have not yet happened with sustainability reporting, such as a key event that legitimises a sustainability reporting standard or gives it global recognition (Tschopp and Huefner 2015).

Australian Context

The research study was conducted in Australia, where four organisations participated in the IIRC’s business pilot programme, six organisations participated in the investor network pilot programme, and over 30 submissions (direct or part of a global submission) were made to the IIRC’s 2013 Consultation Draft of the <IR> Framework. The current approach to sustainability reporting in Australia is now discussed, in order to provide some context for the research participants’ perspectives on IR and regulatory reform.

Two attempts were made in 2006 to change the Australian disclosure system to move towards mandatory sustainability reporting: the Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee (CAMAC) inquiry into The Social Responsibility of Corporations, and the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services (PJCFS) inquiry into Corporate Responsibility. The enquiries concluded that “there was no need to change the existing legal framework, because it is currently sufficiently open to allow companies to pursue a strategy of enlightened self interest”, which was the “the desire of companies to avoid regulation” (PJCFS 2006, p. xiv). The committees concluded that sustainability reporting should continue to be voluntary not legislated. Reinforcing arguments in the literature (Overland 2007; Thirarungrueang 2013), the committees argued that mandatory reporting was counterproductive as the financial costs of compliance would be too expensive and it would result in a superficial “box ticking” mentality leading to “an undesirable outcome and one that defeats the purpose behind the concept of corporate responsibility” (PJCFS 2006, p. xv).

More recent developments have further supported the voluntary reporting approach. The Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) released the third edition of its Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (CGPR) in 2013. The CGPR provide a suggested approach to corporate governance for listed corporations, which operates on the basis of “if not, why not?” compliance. A listed public company must disclose in its annual report the extent to which it has complied with these principles. A company may choose not to comply with a particular principle or recommendation, but if so it must explain in its annual report the extent of the failure to comply, and the reasons for this failure. This is commonly referred to as “comply, or explain” reporting (Overland 2007). Principle 7 includes the requirement that a listed entity’s risk management system should (Australian Securities Exchange 2013, p. 27):

identify and address all material business risks it faces. These risks may include strategic, operational, governance, legal, regulatory, environmental, sustainability, ethical, reputation or brand, technological, product or service quality, human capital, financial reporting and market-related risks.

Principle 7.4 specifically states that “A listed entity should disclose whether, and if so how, it has regard to economic, environmental and social sustainability risks” (Australian Securities Exchange 2013, p. 28).

Another voluntary approach is promoted by The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). ASIC released Regulatory Guide 247 (RG247) for listed entities to provide guidance to directors on useful and meaningful information for shareholders when preparing an operating and financial review (OFR) in a directors’ report (ASIC 2013). Clause 63 states that (p. 19):

An OFR should include a discussion of environmental and other sustainability risks where those risks could affect the entity’s achievement of its financial performance or outcomes disclosed, taking into account the nature and business of the entity and its business strategy. For example, environmental risks that may affect an entity’s achievement of its financial prospects would be more likely for an industrial entity than for a financial services entity.

The ASX CGPR are considered to form the best framework available for reporting requirements as companies are already comfortable with the current regime of “comply or explain” and annual reports are made available for the public, not just to their shareholders, giving greater transparency to their actions (Overland 2007; Thirarungrueang 2013).

Growth of Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Frameworks and Standards

As mentioned earlier, voluntary sustainability reporting is supported by companies, international organisations and developed states, which has spurred a significant increase in sustainability reporting frameworks since the 1980s. Brown et al. (2009b) estimate there are over 30 that address the three aspects of sustainability (environmental, economic and social), while there are hundreds of domestic sustainability reporting guidelines, principles and standards that address some aspects (Tschopp and Huefner 2015). Waddock (2008) refers to this myriad of reporting guidance as a ‘new institutional global CSR infrastructure’. This CSR infrastructure supports a soft-regulatory approach (Albareda 2013). Within this CSR infrastructure, there are a number of multi-industry standards with a global scope such as the UN Global Compact (UNGC), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), ISO 26000, SA8000, the AA1000 standards series, and the Carbon Disclosure Project, as well as industry-specific standards. More recently, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (2015) has been developing industry-specific sustainability accounting standards for US publicly listed companies “that help public corporations disclose material, decision-useful information to investors”. The proliferation of codes and standards can be confusing for organisations and increases costs (Doane 2002).

With over 7400 organisations using the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative 2015b), it is the most widely used guidance for sustainability reporting (Brown et al. 2009b; Hess 2014; Tschopp and Huefner 2015) and considered to be the de-facto sustainability reporting standard (Dumay et al. 2010; Levy et al. 2010; Milne and Gray 2013; Turner et al. 2006). The GRI framework aims to provide for sustainability reporting what generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) provides for financial reporting (Sherman 2009) and to harmonise the confusing field of sustainability reporting standards and frameworks (Brown et al. 2009b).

The GRI was formed in 1997 by the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES) in collaboration with the Tellus Institute and released its first framework in 2000. Its mission is “to make sustainability reporting standard practice” (Global Reporting Initiative 2015a). In response to criticism of the GRI one-size-fits-all approach, Sector Supplements were introduced in 2004 for a number of industry sectors, not as a replacement for the more general GRI framework but to fill the gap (Dumay et al. 2010) and address the more specific issues encountered by companies in particular industries (Sherman 2009). In 2013, GRI released the fourth generation of its Guidelines—G4.

Tschopp and Nastanski (2014) believe that the GRI’s standards are the most likely candidate to become an agreed upon standard as they more closely resemble a financial accounting standard in terms of content and depth and the same rigour (Alonso-Almeida et al. 2014). While the GRI has enhanced the legitimacy of sustainability reporting through a common language and assumptions (Levy et al. 2010), scholars criticise the GRI for its failure to harmonise the multitude of sustainability reporting standards and frameworks, and to unify the social reporting field around a single set of standards (Brown et al. 2009b; Sherman 2009). They argue that instead of harmonising the sustainability reporting standards field, the GRI appears to have contributed to the competition among reporting guidelines for legitimacy and visibility. It also has not resulted in the generation of data that are of high and consistent quality and that can be easily compared across companies. Tschopp and Nastanski (2014, p. 148) argue that if sustainability reporting is to be used as a “market based mechanism on a macro-scale to improve social and environmental performance” then comparable and consistent standards are required. However, there is considerable variability in the form of disclosures in reports using the GRI, even in companies operating in the same industry, and “disturbing” inconsistencies in how economic, social and environmental performance is reported (Sherman 2009). In addition, there are systemic problems with the GRI due to its seemingly contradictory goals to achieve: comprehensiveness and simplicity; meet all individual needs and continuously evolve; efficiency/streamlining and inclusiveness (Brown et al. 2009a).

Unlike Tschopp and Nastanski (2014), Brown et al. (2009b) believe that the GRI falls far short of being equivalent to a financial accounting standard. There is little pressure among companies to issue GRI reports and be accountable for their content if they do issue them. While the GRI has successfully become institutionalised, its instrumental value for private regulation is modest (Brown et al. 2009b; Levy et al. 2010) and it is considered by some as a failure of the ‘soft’ approach to regulation (Buhr et al. 2014; Levy et al. 2010). In efforts to shape GRI as complementary to corporate and financial market needs, GRI has instead been “co-opted and assimilated within these structures rather than transforming” the broader power structures (Levy et al. 2010, p. 111). While companies are willing to provide a level of accountability and transparency for their social and environmental impacts, they are less willing to “tolerate a system that provides clear measures and rankings of their social and environmental performance” (Levy et al. 2010, p. 111). Buhr et al. (2014) further argue that the set of GRI indicators does not demonstrate that substantial accountability is being discharged. The failure of the GRI’s voluntary approach to increase accountability and more substantive disclosure supports the case for introducing mandatory reporting requirements, or at least a path of “authoritative leadership” (Buhr et al. 2014, p. 65).

Methods

As integrated reporting is a recent reporting phenomenon, the research study utilised an exploratory approach. Exploratory studies (developing a rough description or an understanding of some social phenomenon) are useful where little knowledge exists in the literature (Blaikie 2000). The research study employed an interpretivist mode of inquiry using a qualitative research design. Interpretivism views the social world as the world interpreted and experienced by its members from the ‘inside’. Qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or to interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings that ‘insiders’ bring to them (Blaikie 2000). As the research is exploratory in nature, a qualitative approach is more appropriate to emerging areas of research (Marshall and Rossman 1999). An interpretivist approach lends itself to engaging actors with qualitative research tools, such as interviews, to draw out the views and meanings actors ascribe to their social realities.

The primary IR stakeholders come from the corporate, investment, accounting, securities, regulatory, academic, civil society and standard-setting sectors (IIRC 2011). The IIRC states that the target audience for integrated reporting is providers of financial capitalFootnote 1 (the users), referred to as the Investment Supply Chain by participants in our study (see Appendix 1). This study involved 22 in-depth semi-structured interviews, focussing on Australian users of integrated reporting (providers of financial capital) and non-corporate stakeholders, as their perspectives are largely absent from previous IR studies. Australia is a relevant site for investigating IR due to the interest shown by stakeholders, as evidenced by the participation in the IIRC’s pilot programmes and submissions to the IIRC’s 2013 Consultation Draft of the <IR> Framework.

Data Selection and Collection

Potential participants were identified from a number of sources: (1) the regulatory and standard setting bodies with oversight of corporate reporting in Australia; (2) submissions by Australian organisations to the IIRC’s Draft International <IR> Framework; (3) Australian participants in the investor network pilot programme; (4) Industry and professional bodies representing the financial and investment community; (5) the academic and practitioner literature (for e.g., Adams and Simnett 2011; Frías-Aceituno et al. 2013a; Strong 2014); and, (6) through snowballing techniques. Snowball sampling involves using a “group of informants with whom the researcher has made initial contact and asking them to put the researcher in touch with people in their networks, then asking those people to be informants and in turn asking them to put the researcher in touch with people in their networks and so on as long as they fit the criteria for the research project” (Minichiello et al. 1995, p. 161). 32 organisations were identified through this process and approached for an interview, with 22 accepting. 21 interviews were face-to-face and one was via phone. The sample of stakeholders included three regulators, two standard setters, six industry bodies and professional associations, three accounting firms, and eight investment and investment research organisations (see Table 1). The financial investment stakeholders represent six of the seven stakeholder groups in the investment supply chain (see Appendix 1). We sought representatives who were familiar with sustainability and/or integrated reporting. However, the sample is not representative of all IR stakeholders, and in particular, does not include civil society. The sample is strongly weighted toward stakeholders who were actively engaging with the IIRC at the time of the interviews, either through the pilot networks, submissions to the IIRC and/or meetings with IIRC representatives (18 of the 22 participants). As we were interested in seeking the users’ perspectives (providers of financial capital), the sample is also strongly weighted toward financial stakeholders (financial regulators, accounting firms and standard setters, industry bodies representing financial and accounting stakeholders, and the investment supply chain). We acknowledge that this sample represents a bias of participants that are representative of financial capital, and not necessarily of the other five capitals referred to in the <IR> Framework (manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural). The other five capitals may be more aligned with the interests of civil society interest groups (IIRC 2011).

The interviews were 35–65 min duration and were recorded and transcribed (with permission). The interviews were guided by the following prompts to explore the participants’ perspectives on the role of regulation, standards and guidelines in the spread of integrated reporting:

-

Shortcomings in prevailing corporate reporting practice;

-

The type of information that is necessary to ensure the ‘decision-usefulness’ of an integrated report, and in what form it should be presented;

-

Minimum requirements for a useful integrated report, and why should these be required;

-

The extent to which regulation is necessary to ensure the effectiveness of an integrated report;

-

The influence of standards in meeting users’ information requirements or whether these are best met through voluntary guidelines;

-

Elements that can/should be ‘discretionary’ or ‘regulated’ and what role do these elements play in ensuring the effectiveness of an integrated report to meet users’ information requirements?; and,

-

Which organisations/institutions should be involved in the regulatory and standard setting process?

Data Analysis

The transcript of the interview and a summary of the findings were emailed to each participant inviting them to provide comments and/or corrections. This process enhanced the reliability and validity of the research study (Minichiello et al. 1995; Yin 2009). A content analysis of each interview was undertaken using qualitative coding techniques (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Using the NVIVO software package, the transcribed interviews were analysed and coded to draw out key themes. A three-stage coding process was employed: open coding, axial coding and selective coding. Open coding identifies and annotates concepts and their properties; axial coding groups codes together into categories to form more complete explanations of the data; and selective coding integrates and refines the categories into themes as patterns emerge (Patton 2002; Strauss and Corbin 1998). Codes were derived from the interview data based on the actual words or terms used by the interviewees (in vivo codes) or by summarising the concepts discussed by the interviewees (constructed codes). Through coding at the word, phrase, sentence and paragraph level, patterns emerged within the data (Neuman 2003; Patton 2002) resulting in the key themes discussed in “Findings” section. An interpretivist approach, utilising qualitative data collection and analysis methods, is an appropriate methodological approach in exploratory research of this nature (Crane 1999).

To retain confidentiality of participants, codes are used to report the findings (see Table 1). The paper makes liberal use of quotes to allow, as much as possible, the participants to speak for themselves “to reveal the patterns of meaning by which they understood their own experiences” (Lawrence 2002, p. 73).

Findings

IIRC’s premise for IR is that current corporate reporting doesn’t meet the needs of the investment community. The information available in corporate reports is inadequate for decision-making (Simnett and Huggins 2015) as it is confusing, cluttered, fragmented and disconnected (IIRC 2011). Furthermore, reports are too long and complex, there is inadequate information on non-financial factors, and current reporting focuses on compliance rather than communication. While the research study sought to explore stakeholders’ perspectives on mandatory and voluntary approaches to IR, we first wanted to understand if the various actors in the IR field thought there were issues with the current corporate reporting system that required a solution. While 18 participants agreed with the IIRC that there were issues with the current reporting regime, four were “not convinced that there is a problem that needs fixing” as the “reporting regime is a well-defined framework” [Reg3]. One didn’t “really see the point” [FS3] of IR as the information is already available from existing websites and by talking directly to companies. In contrast, a financial stakeholder thought that corporate reporting is not “fit-for-purpose today” and while IR is “not a panacea in our view”, it will enable companies to “focus their intention on what the long-term value creation story is as opposed to getting lost in the cacophony of other stuff that’s being pushed out of companies” [FS5]. This suggests that current reporting fulfils the needs of a small group of stakeholders, but the majority of stakeholders think there is a problem that needs addressing.

However, there was not consensus that IR was the solution to the problem. Three urged caution because they didn’t think that the exact nature of the problem was well articulated. Only two participants thought that “it’s all in there” [FS8], while ten thought IR could “steer companies in the right direction” [FS7]. The remaining seven participants were more neutral about whether IR can address perceived issues with the current corporate reporting regime.

In light of this, it is not surprising that there is little appetite for mandatory integrated reporting (see Table 1). Only five interviewees held a strong view that integrated reporting should be mandatory. Six felt that some level of regulation may be necessary, while eleven interviewees—including all the regulators and standard setters, two of the three accounting firms, half of the industry bodies and one financial stakeholder—believe that integrated reporting should remain a voluntary principles-based approach. The perspectives of those supporting regulation are first discussed, followed by the perspectives of those supporting a voluntary approach. Finally, we discuss participants’ views on what should be mandatory and what is possible to be addressed through voluntary standards or guidelines.

Regulation is Necessary to Drive Change

Five participants, including four of the eight financial stakeholders and an industry body representing shareholders, support mandatory integrated reporting because it is seen as a way “to keep the pressure on” to improve companies’ reporting “with a greater investment focus around value and materiality” [FS2]. Otherwise, IR “won’t happen any time soon” [FS4]. The financial stakeholders already ask companies to report on their ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) issues and suggest that mandatory IR will “get companies to dedicate the resources to it” as “the disclosure is the basis for the conversation” [FS8] that investors have with organisations to understand their material ESG risks.

If IR is voluntary, as per the ‘if not, why not’ principles-based approach taken by ASX and ASIC, it encourages companies to not treat it as a priority and therefore use the ‘why not’ option. For example, one financial stakeholder talked about their experience with product disclosure statements: “everyone decided that they wouldn’t disclose because it was too hard, so they just explained” [FS6]. Another was concerned that “you will never catch the recalcitrant or the laggards because they just wouldn’t do it” [FS4]. This has occurred with sustainability reporting. While there have been improvements in reporting in the past few years, some listed companies claim “we’re too small … ESG issues aren’t really relevant for our business” [FS4], even though investors are asking for this information. Participants continue to see “poor standards in reporting or lack of reporting” of ESG issues. They cited recent examples where “ESG issues have been causing material problems” [FS2] but these issues have not been disclosed in sustainability reports. These participants were concerned that leaving IR as voluntary would lead to the same outcomes. This raises concerns that, like voluntary sustainability reporting, voluntary IR will reinforce the lack of accountability by companies for their impacts on society and the environment (Buhr et al. 2014).

While there was considerable support for ASIC’s approach of utilising the operating and financial review (OFR) rather than IR (see next section), an industry body representing shareholders believes that mandatory IR would provide “better information than we get out of the OFR because that’s all a bit vague. It doesn’t tell me a lot if I want to make an investment decision” [IB2]. Two participants compared voluntary IR to the voluntary GRI guidelines, which they see little value in because “there’s no GRI police, there’s no-one checking that the disclosures are robust, and the quality of a GRI report” [FS8]. These views echo Sherman’s (2009) criticisms of GRI and support arguments that regulation is necessary to enable investors to make more informed decisions (Overland 2007).

Strengthening this argument, one regulator who supported voluntary IR suggested that if it was left as an ‘if not, why not’ voluntary approach, then in Australia “95 % of listed companies would say, ‘We’re not doing it and here’s our reason why’”. This person pointed to the IIRC’s preference for voluntary adoption of IR rather than legislation, as “they think that over time, if it becomes the norm, then it’s much harder for reporters to ‘if not why not’ explain their way out of it” [Reg3]. They suggested that IR is an “idea well before its time” and there is “little appetite” from companies to adopt IR, let alone to regulate it.

The views of the pro-regulation participants support arguments that regulation makes companies more accountable for their material social and environmental impacts (Larrinaga et al. 2002; Thirarungrueang 2013). However, the financial stakeholders’ focus is on value creation for investors and not value for society (Flower 2015). They are focused on ESG impacts and risks and not necessarily interested in stewardship of environmental and social capital unless it impacts the value of the firm. As a result, IR regulation sought by these financial stakeholders may not be effective in enhancing accountability for environmental outcomes nor in providing substantive disclosures that will lead to increased levels of sustainability (Hess 2014). This brings into question whether the dual aims of IR are achievable: that of communicating to providers of financial capital the factors that impact the ability for organisations to create value, and that of enhancing accountability and stewardship of the six capitals.

One argument against regulation is that it can lead to a ‘tick-the-box’ culture of compliance (Overland 2007). Two participants did acknowledge the risk that IR regulation could result in companies “just doing that sort of boilerplate reporting and that we obviously don’t want” [FS7]. While they support IR regulation these two financial stakeholders don’t want to be too prescriptive about what companies should report, and how much they should report:

it really is up to the companies because we know the risks to some extent but they’re living and breathing it. They know what the risks are that face their company and how these things impact their company so we really do want the companies to take the lead on it. [FS7]

Voluntary Approaches are More Effective

Eleven participants were not convinced that there is a case to be made for mandatory integrated reporting as there isn’t “a pressing market failure or regulatory problem at the moment that requires an urgent need to introduce integrated reporting” [Reg 2]. Nor do the participants believe that there is any groundswell of support in Australia. While there are “one or two directors and former CFOs who are strong proponents” the other proponents are “the accountants and they’re rather self-interested; it’s another source of revenue” [Reg3], which adds weight to concerns that integrated reporting is captured by accountants and the market discourse (Flower 2015; van Bommel and Rinaldi 2014). Similar criticisms are directed at the GRI where the four largest accountancy firms are significant actors in the GRI field and are strong promoters of sustainability reporting, which provides a significant part of their business (Brown et al. 2009b). While the strong representation by accountants may enhance financial accountability, it is questionable whether it advances social and environmental justice as called for by van Bommel and Rinaldi (2014), or leads to increased levels of sustainability (Hess 2014). One accounting firm suggested that IR is “effectively just about getting [financial] capital to the right companies” [AF2], not about accountability and stewardship for the broad base of capitals as presented by the IIRC (2013).

Four people suggested it was too early to consider a regulatory approach as the IIRC framework was only released in December 2013. A regulator, for example, stated that the framework has “a long way to go before it’s going to be appropriate to recommend that listed companies across the board adopt it” [Reg3] and an industry body argued that “if you regulated around it at this stage, you’re setting something in concrete that is actually still a quite malleable beast” [IB5].

Participants felt, especially given its early stage of development, that mandatory reporting would increase the reporting burden and could result in a ‘tick-the-box’ mentality. They talked about the cost of reporting, another overlay of reporting, the extra work, additional complexity, additional requirements, and reporting becoming quite burdensome—similar to arguments raised against mandatory sustainability reporting (Fallan and Fallan 2009; Maltby 1997; Overland 2007; Thirarungrueang 2013). According to an industry association, the outcome is that directors would question the value of IR, so it should remain voluntary:

I think directors consider where the value proposition is. I think it takes a commitment that would probably be a lot greater than many companies are prepared to make at this point in time. I think a lot of them would struggle to see the value today. [IB1]

There were doubts that IR is the “cure for corporate reporting” [IB6], especially if it adds “an extra reporting layer on top of an incredibly onerous statutory reporting layer” [Reg3] and mandating it would inhibit potential benefits of IR:

we feel that the very thing that you want to achieve with it—which is in a sense integrated thinking, that’s a cultural shift—if you impose it as a compliance burden at this point, you won’t get that benefit of people talking through how we approach this. [a pilot company] say that it’s been the greatest benefit; that it had all these disparate internal stakeholders having to talk to each other for the first time and we see that as one of the greatest benefits and we think if you mandate it, that gets lost. [IB5]

Six participants were concerned that mandatory IR would mirror the experience of mandated remuneration reporting that resulted in “what is seen as largely incomprehensible 30 page remuneration reports” [IB5].

A lack of appetite for regulatory reform also rests on differing views about how to bring about change in reporting activity. Regulation was seen as politically difficult—it would be counterproductive as it would just get companies and directors off-side [SS2]. It was better, in the view of one industry body, to let the process unfold [IB5]. Aligned to this view, three participants referred to the market-based approach as the best way forward. The best chance for IR to become the reporting norm is “to stay voluntary now and just let the market take this up rather than having a backlash, which is what we would have certainly in this jurisdiction” [SS2], which lends credence to van Bommel’s and Rinaldi’s (2014) argument that IR privileges the powerful discourse of the market. However, if it remains as a principles-based framework, there is “inherent flexibility” [SS2] to tailor it to a company, particularly regarding materiality, which will reduce complexity. One positive outcome of the process of developing the principles-based International <IR> Framework is a “commonality of language” [IB5] due to stakeholders agreeing on key concepts, as GRI did for sustainability reporting (Levy et al. 2010).

While the arguments against mandatory IR reflect the arguments against mandatory sustainability reporting—high costs due to the increased reporting burden and complexity to comply with regulation; the potential for a ‘tick-the-box’ culture; and the potential for an antagonistic mentality (Overland 2007; Thirarungrueang 2013)—one major issue raised with voluntary sustainability reporting is the difficulty of comparing data across companies (Doane 2002; Overland 2007; Thirarungrueang 2013). Participants did not regard this as an issue for voluntary IR. Transparency, “a meaningful discussion around materiality” [FS7] and “how each individual company is managing what’s relevant to it” [FS3] are more important than comparability because even “within a sector, there’s a lot of difference” [FS4]. For example, “Rio Tinto and BHP, big mining companies, have different risk profiles based on what resources, what countries, and different strategies” [AF3], so therefore may have different material issues. The financial stakeholders in particular were more interested in comparability of data within a company—how issues are “trending within a company over time” [FS4]—rather than cross-company comparability.

Those advocating a voluntary approach placed faith in letting things take their course—a lot more companies would be using the framework “5 years down the track” [SS2]. IR “needs to be seen in practice” [FS7] before legislation could be considered. Three participants discussed leaving open the possibility for some subsequent regulatory reform, supporting an approach that uses ‘soft measures’ before introducing mandatory regulation (Thirarungrueang 2013).

I mean the framework is still so new and probably everyone is finding their feet. So it wouldn’t surprise me if once the pilot is finished there could be changes anyway to the framework. Longer-term there could be a role for regulation. [IB6]

Four participants support a voluntary approach to regulation (Hess 2014; Parker 2007; Schwindenhammer 2013), or civil-private regulation (Brown et al. 2009b) where civil society groups are empowered to play a more active role in corporate reporting reform. They thought the best way forward was to adopt the approach taken by the UK government, which formed the Financial Reporting Lab. The Lab brought together key stakeholders to develop market-based solutions to “bring about change in corporate reporting” [IB1]:

where the Financial Reporting Lab in the UK has its value is it knows that if it develops a workable solution that the government department that is responsible will make the necessary changes so there is the sort of tacit agreement that there will be change. [FS3]

The UK government took on the role of “orchestrator”, rather than regulator, and this encouraged firms to experiment on solutions (Hess 2014).

There were, however, some caveats raised with the voluntary approach. The inherent flexibility can lead to different interpretations of the concepts: “you will end up with each and every organisation coming up with what they feel value is” which “makes it complicated” [AF2]. As Larrinaga et al. (2002) suggest, this could convey a misleading view of how an organisation has performed. Four participants questioned whether the six capitals created more complexity or resulted in more effective corporate reporting. A regulator thought the IIRC “just went down the wrong path on that issue” as “no business is going to say for example well, our people aren’t material to our business. So what are we then reporting about in terms of human capital?” [Reg3]. A financial stakeholder argued that the six capitals are “just restating what we already know” and concluded that “it’s just form over substance” [FS3]. However, an industry body reinforced that “it’s up to you to decide of the six capitals what’s material and how you’re going to report” [IB5] so a voluntary approach can reduce complexity and the volume of information. However, a potential downside of this approach is that it can result in a lack of substantive disclosure (Cho et al. 2015a), as one financial industry stakeholder alluded to. She reviewed the integrated report of a company participating in the IIRC Pilot Programme and “based on my own desktop analysis of what I would consider to be the key risks, I then looked at the integrated report to see if they were commented on in that report, and some of them weren’t” [FS3].

Of the eleven participants supporting a voluntary approach, nine proposed that regulation around integrated reporting is not required because the operating and financial review (OFR) has it covered:

I actually think ASIC [RG247] probably got 95 % of what an integrated report seeks to address in terms of prospects and risks. ASIC has done a lot of the hard work there and if it starts to enforce its regulatory guide in that area and it starts to make companies make more open disclosures on those issues, I think that actually addresses a lot of the problems. [Reg3]

ASIC’s consultation process for RG247 included discussion of whether it should provide any guidance on integrated reporting and the conclusion was that “it was too early, it wasn’t a legislative requirement set out anywhere, and the concept was still evolving” [Reg2]. The OFR is “a much better way of approaching IR than someone imposing a new law when you’ve got a lot of reporting fatigue” [IB5]. It was suggested that ASIC’s guidance on the OFR was already working, as there was “quite a degree of improvement around the operating and financial review … we’ve seen the level of compliance with the legal provisions lift quite substantially” [Reg2], and thus there is little incentive to change the regulatory framework. However, in an accounting firm’s experience, the OFR “hasn’t really driven much focus in the non-financial area… it hasn’t really resulted in a lot of extra disclosure” [AF1]. Another five participants supported this view. They believe that the OFR only covers certain aspects of IR “and the less contentious aspects… but getting some really intelligent thought about things like social and relationship capital, that’s not going to come from those changes [to the OFR]” [FS8]. The OFR was too weak, particularly around discussing a company’s “strategic business model”, and its focus was too narrowly focused on ESG issues.

Two participants suggested that the OFR and ASX Corporate Governance Principles could be replaced by an IR framework as “the OFR isn’t enough to do a good integrated report, so I see that as a stepping stone” [SS2]. Furthermore, one financial stakeholder suggested that ASIC and the ASX bin the OFR guidance note and the ASX Corporate Governance Principles:

and build a new thing around the integrated reporting framework, I think that would be a sensible thing to do. A collaborative stakeholder approach to build a new standard, and picking up some of the bits from the old that were helpful and useful but recognising that actually this is a step change, it’s not an incremental change… I mean this is the potential danger with integrated reporting where we just wind up with yet another bandaid solution that just adds more confusion and noise and is seen as just another burden by companies rather than being seen as an opportunity to better communicate with their stakeholders and particularly their investor stakeholders. [FS5]

Middle Ground: A Combination of Regulatory and Voluntary Approaches

Six participants view the relationship between mandatory and voluntary IR as complementary (KPMG et al. 2010; Thirarungrueang 2013), as suggested by Fallan and Fallan (2009). They referred to a middle ground that has a “combination of regulatory change and guidelines” [AF1] but leaves “as much to discretion as is possible” [FS5]:

I think it’s appropriate for it to be regulated but it needs to be done carefully and in a principles-based way, as opposed to being a hard letter regulation that companies just look to get around in some way or cover themselves by introducing a more boilerplate disclosure that’s developed by legal for the purpose of diminishing risks around liabilities … the way investors allocate capital is such that we need to get something like integrated reporting in place quickly, which sort of demands regulation. But then I know from history that that has tended to have unintended consequences and not got the outcomes that are desired so yeah, if we could find a nice middle ground. [FS5]

No-one could provide a clear view of how this would occur at this stage as “it’s really hard to nail down what should be rules and what should be principles” [FS6]. There were differing views about what should be mandatory and what is possible to be addressed through “soft measures” (Thirarungrueang 2013), but discussion coalesced around four key areas: materiality, standards, assurance, and board sign-off.

Regulatory reform was seen as desirable for providing some clarity around materiality. A financial stakeholder maintains that while they “don’t want to be prescriptive in what companies should report or how much they should report; [it is necessary to ensure companies] know what the risks are that face their company and how these things impact their company” [FS7]. They proposed that regulation be considered around the materiality process.

Regulation had not kept pace with reporting changes underway and reform was necessary where existing standards were proving to be inadequate. A standard-setter argued that it is:

reasonably well accepted I think that the current standards don’t go far enough in terms of dealing with things [such as] the narrative information, forward-looking information, a combination of financial and non-financial … so there is a need to actually put some rigour into how you go about doing these kind of assignments. [SS2]

One regulator suggested that until there were standards that can guide people, there was little benefit in integrated reporting.

There was strong support from half the participants for an assurance standard, but only six thought that there should be some form of regulation. An industry body argued that directors and boards would be looking for “some form of rigour” [IB 1] to be able to sign off an integrated report, which requires a level of assurance. Independent external assurance is a key mechanism to help ensure integrated reports are, and are seen to be, credible. 81 per cent of respondents to the IIRC’s Consultation Draft agreed that there was “a need for external assurance of an integrated report and that independent, external assurance was a fundamental mechanism for ensuring reliability and enhancing credibility” (Simnett and Huggins 2015, p. 44). The IIRC released assurance discussion papers in July 2014 to seek input on whether assurance is necessary and to consider its benefits and challenges (IIRC 2014a, b). The International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) has set up a formal <IR> Assurance Working Group to monitor the developing interest in integrated reporting and the demand for assurance on integrated reports. One accounting firm suggested that:

at that moment the voluntary nature of assurance means that you probably aren’t getting the sort of coverage you need to accurately reflect whether or not a company is talking about the right things… there should be mandated assurance over information if it’s fundamental to the value creation story and it’s fundamental to information which boards are signing off on and reporting on an at least an annual basis so it should be no different to the financial. [AF2]

This perspective is supported by Ackers’ and Eccles’ (2015, p. 517) research into the impact of the “de facto regulatory requirement” for assurance on sustainability disclosure in South Africa. The King III principles require companies listed on the Johannesburg stock exchange (JSE) to provide independent assurance of sustainability on an ‘apply or explain’ basis. They found that while there had been steady growth, independent sustainability assurance for JSE-list companies was “disappointingly low” (p. 531) and there were inconsistencies in sustainability assurance practices. In addition, Buhr et al. (2014) argue that the lack of external assurance of sustainability reports signals the failure of these reports to provide confidence in their accuracy and reliability. These findings provide weight for AF2’s call for regulation on IR assurance. However, this is in contrast to Fallan’s and Fallan’s (2009, p. 487) conclusion that while regulation can ensure a minimum standard of disclosure, “comprehensive voluntary reporting underlines the need for auditing, review, and enforcement to improve accountability rather than more regulations”.

Participants did point to the complexity in creating regulation around assurance, particularly on assessing “the quality of the narrative” [AF3]. Issues were raised about what the assurance would cover:

so materiality; the boundary of the report; does the framework constitute suitable criteria to form the basis of the assurance engagement; forward-looking information; and the ability and willingness of practitioners to provide assurance on that. Do they come back and just talk about assurance on the process of preparing the report, which is pretty meaningless in my view? If you’re not going to do it on the report itself then I’m not sure why you’d bother. [SS 2]

On the issue whether assurance should be on the content of integrated reports and/or the process, one participant suggested that it should be focused on the process rather than the data, to ensure that “the statements that they’re making and the risk management frameworks and materiality assessment frameworks that they’ve used are there and exist and that there’s rigour around them” [FS5].

With respect to narrative information, a regulator pointed out, “it’s a lot easier to audit numbers than it is to audit narrative” [Reg2], which was reinforced by an investor who argued that “descriptions of how a company’s managing a particular risk, I don’t know how that could be audited” [FS4]. A standard setter floated the idea that had been raised in an industry forum, that “rather than launching into an assurance standard on integrated reporting, we look at standards on narrative reporting, forward-looking information and combined financial and non-financial information” [SS2]. Similar issues were raised by Ackers and Eccles (2015) with respect to assurance on sustainability disclosure. They recommended mandatory sustainability assurance to regulate the quality of assurance practices, the type of assurance provider (including their qualifications and expertise), the assurance engagement scope and procedures.

There were also mixed views on whether it should be mandatory that Boards of Directors sign off integrated reports. One financial stakeholder was less interested in mandating assurance than mandating Board sign-off of IR because:

integrated reporting is meant to support integrated thinking. If that’s not happening at the highest level of the business, how is that going to enhance sustainability or financial system stability, all the other things that integrated reporting wants, and this is one of the problems with sustainability reports. They’re done at too low a level without an understanding of the strategic picture. [FS8]

They further argued that Boards will “get the assurance they think they need” to get the “level of comfort they require”. However, other participants were concerned about mandating Board sign-off. In particular, six participants raised the issue of directors’ liability for forward-looking statements in integrated reports, an issue highlighted by Simnett and Huggins (2015) particularly in countries where there is no safe harbour provision for directors making forward-looking statements that turn out to be inaccurate. However, another six participants thought the issue was overstated as it “simply requires a narrative discussion about what the future prospects of the company are” [Reg2] and ASIC had already addressed this by providing some guidance on making statements about future prospects in OFRs to avoid liability issues.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to explore the perspectives of users of IR on regulatory and voluntary approaches to IR, as their voices have largely remained silent in the literature. Overall, we found more support for voluntary approaches to IR as the majority of participants thought that it was too early for regulatory reform. This is consistent with companies’ support for voluntary approaches. The supporters of voluntary IR suggest that IR will become the reporting norm over time if left to market forces as more and more companies adopt the IR practice. This perspective feeds into van Bommel and Rinaldi’s (2014) concerns that integrated reporting will privilege the powerful discourse of the market over advancing social and environmental justice. According to the supporters of voluntary IR, the inherent flexibility in a voluntary approach will encourage experimentation and enable organisations to learn from others’ IR practices. Over time IR will be perceived as a legitimate practice, where the actions of integrated reporters are seen as “desirable, proper, or appropriate” (Suchman 1995, p. 574). As one regulator concluded, companies will find it harder to “‘if not why not’ explain their way out of it” [Reg3]. While voluntary IR will encourage the spread of IR, the participants do not rule out a regulatory response in the future, and about one-third already support a combination of voluntary and regulatory mechanisms, particularly to address the issues of materiality and assurance.

This path (combination of voluntary and regulatory mechanisms) requires the support of standards that can guide reporters, as current standards aren’t adequate to address non-financial information. Tschopp and Nastanski (2014) argued that financial reporting did not meet the needs of stakeholders until reliable standards were established in the US by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in 1973 and globally by IASB in 2001. Developing standards for IR will take time, as “there’s so much work to do in terms of settings standards, working through what are the difficulties in practice… we think about financial reporting, that’s all quite sophisticated and proper systems and processes and controls” [SS2]. The broader remit of IR of value creation rather than sustainability impacts, and the failure of the GRI to provide an equivalent of a financial accounting standard (Brown et al. 2009b), suggests that the accounting standard setters “should be in this space” [SS2] to align IR standards with the next generation of accounting standards, to include “narrative reporting, forward-looking information and combined financial and non-financial information” [SS2]. SASB appears to be positioning itself in this space by extending “accounting infrastructure to material sustainability factors … such that financial fundamentals and sustainability fundamentals can be evaluated side by side to provide a complete view of a corporation’s performance” (SASB 2015). While SASB is considered as complementing FASB, it is too early to evaluate the impact of SASB (Tschopp and Nastanski 2014) and whether it facilitates the more holistic approach intended by IR rather than the narrower sustainability impact focus of the GRI.

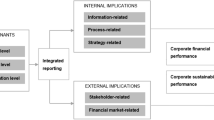

While there is little appetite for regulatory reform, it is interesting to note that half of the financial stakeholders did support mandatory IR, with another three supporting some level of regulation. Their arguments, based on their experience of reviewing companies’ sustainability reports, lend support to scholars’ criticisms of voluntary sustainability reporting; that it does not necessarily lead to more substantive disclosures and accountability (Cho et al. 2015a) nor increase the quality of reporting (Milne and Gray 2013). The findings raise concerns about whether IR can achieve the IIRC’s vision that IR will enhance accountability and stewardship of the broad base of capitals. The findings provide some insights into whether IR, at this formative stage, is following the same path as sustainability reporting or whether it has the potential to lead to more substantive disclosures and enhance accountability and stewardship, as envisioned by the IIRC. We conclude this paper by providing some reflections on this.