Abstract

Chinese consumers comprise a unique subculture that exerts a considerable influence on the market and are treated as a collective group by researchers. However, few studies have examined the effects of collectivism and consumer attitudinal attributes on consumer ethics. Although the practice of religion was prohibited in China before economic reforms in the late 1970s, religion remains a major factor that affects the ethical judgment of consumers. The present study, based on the Hunt–Vitell model, examines the influence of culture (collectivism and religion) and personal characteristics (attitude toward business) on consumer ethics. A total of 284 Chinese consumers were surveyed. Structural equation modeling was used to test hypothesized relationships in the research model. The results indicate that collectivism had a significant explanatory power for four dimensions of consumer ethical beliefs: (a) actively benefiting from illegal activities; (b) passively benefiting from questionable activities; (c) actively benefiting from deceptive legal activities; and (d) engaging in no harm and no foul activities. However, consumer attitude toward business significantly explained only the passive dimension of consumer ethics, and religious beliefs significantly explained only the active dimension of consumer ethical beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

China has become more materialistic during its prosperous economic development (Swanson 1995). McGregor (1992) argued that the Chinese government is engaged in promoting materialism because it is correlated with a higher economic growth rate. However, previous studies have found that the excessive pursuit of materialism may increase unethical consumer behavior (Huang et al. 2012; Lu and Lu 2010). Whitcomb et al. (1998), comparing the business ethical values between Chinese and Americans, found that Chinese people were sometimes more motivated by profit and more likely than Americans to use informal and illegal means to achieve their profit objectives. Considerable research is required to more clearly understand the links among cultural values, the institutional environment, and ethical decision-making in China. It is crucial to understand why Chinese consumers engage in unethical behavior, because it could be helpful in ultimately curtailing questionable practices.

Over the past decade, the topics of culture and ethics in business have gained considerable attention. The general theory of marketing ethics developed by Hunt and Vitell (1986, 1993) has specifically been applied to all business situations. The Hunt–Vitell model proposes cultural and personal characteristics as two of the constructs that influence a person’s perceptions in ethical situations. Although the model recognizes the importance of culture, few studies have incorporated the cultural component in ethical situations. Thus, Singhapakdi et al. (1994) and Tavakoli et al. (2003) indicated that culture is a crucial variable that affects consumer ethical decision-making and behaviors.

Hofstede (1980, 1983, 1984) has argued that four relevant cultural typologies exist: power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. Although Hofstede’s model has been widely accepted for assessing the construct of culture, Vitell et al. (1993) were among the first researchers to develop propositions concerning the influence of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions on ethical decision-making. Thus far, with the exception of the propositions by Vitell et al. (1993), empirical examinations into Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and consumer ethics are lacking. Only Swaidan (2012) has examined the effect of culture on the consumer ethics of African-American consumers by using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Among the four dimensions, the individualism and collectivism dimension has been the most widely applied to the topic of cross-cultural management in social science research (Triandis and Bhawuk 1997). According to Husted and Allen (2008), individualism and collectivism affect ethical decision-making more than any other cultural dimension does. From Hofstede’s perspective, the Chinese are generally treated as a group characterized by collectivism. Similarly, Jenner et al. (2008) proposed that China has unique subcultural characteristics. Therefore, it is crucial for marketers to develop internal corporate policies and external marketing strategies geared toward Chinese consumers that recognize a collectivist mainstream culture.

In most studies, exploring the relationship between individual factors and consumer ethics, researchers have focused on the individual’s personal moral philosophy (e.g., idealism, relativism, materialism, and Machiavellianism) and how it influences his or her perceptions of the questionable behavior under consideration (Al-Khatib et al. 1995; Arli and Tjiptono 2014; Huang et al. 2012; Lu and Lu 2010; Swaidan et al. 2003). A critical but often neglected factor is the individual’s attitudinal attributes. Since the first study of consumer ethics by Vitell and Muncy (1992), subsequent investigations have seldom discussed the effect of consumer attitudinal attributes on consumer ethics, and examination of this construct’s role in consumer ethical decision-making is overdue (Vitell et al., 2007).

According to the Hunt–Vitell model, religion is both a personal and cultural characteristic, meaning that it is intrinsically linked to two factors that affect marketing ethics. However, research on religion and ethical outcomes has yielded inconsistent results (Weaver and Agle 2002; Longenecker et al. 2004; Parboteeah et al. 2008). Some studies have argued that there are negative relationships between religion and ethics (Clark and Dawson 1996), whereas others have found no relationship between the two (Parboteeah et al. 2008). Interestingly, several studies have found a positive impact of religion on ethical practices (Giacalone and Jurkiewicz 2003; Longenecker et al. 2004). It follows that individuals who are more religious can be expected to be more ethical.

Although religion and consumer attitudinal attributes have long been subjects of study, Vitell et al. (2007) and Vitell (2009) have identified the examination of these two variables as a relatively under-researched area in consumer ethics. Thus, the present study was based on the Hunt–Vitell model and examined the influence of culture dimensions (specifically, collectivism and religion) and certain personal characteristics (specifically, attitude toward business) on consumer ethics. The results contribute to the consumer ethics literature by shedding light on the roles of collectivism, attitude toward business, and religious beliefs. Furthermore, because this study was conducted in China, the results can be compared with the findings of studies concerning other collectivist cultures.

Theoretical Foundations and Hypotheses

Consumer Ethics

Muncy and Vitell (1992) published a pioneering article in which they defined and developed a scale for consumer ethics. Since then, numerous studies relating to consumer ethics have been published. Vitell and Muncy (1992) postulated the following dimensions of consumer behavior: (a) actively benefiting from illegal activities (ACTIVE); (b) passively benefiting from questionable activities (PASSIVE); (c) actively benefiting from deceptive legal activities (DECEPTIVE); and (d) engaging in no harm and no foul activities (NOHARM). The ACTIVE dimension refers to the profits obtained by consumers from sellers through direct behaviors that most consumers think are illegal (such as changing the labels of goods in a store). The PASSIVE dimension refers to consumers passively obtaining profits from seller mistakes (such as keeping change when a store clerk returns too much). The DECEPTIVE dimension refers to consumers actively partaking in problematic behaviors (such as purchasing goods by using expired coupons). Although the above behaviors are not illegal, they are controversial. The NOHARM dimension refers to insignificant behaviors that do not directly harm people (such as consumers returning goods that they do not like after using the goods). Many consumers believe that this type of behavior is acceptable.

Many studies have adopted the Muncy–Vitell consumer ethics scale to study consumer behavior in various countries, such as investigations focusing on the United States (Vitell et al. 1991; Muncy and Vitell 1992; Vitell and Muncy 1992), Egypt and Lebanon (Rawwas et al. 1994), Australia and the United States (Rawwas et al. 1996), Muslim immigrants in the United States (Swaidan 1999), Northern Ireland and Hong Kong (Rawwas et al. 1995), and Northern Ireland and Lebanon (Rawwas et al. 1998). To summarize, many cross-cultural studies on consumer ethics have demonstrated that consumer ethics varies among cultures. However, only a few researchers have examined consumer ethics in Asia, focusing on Hong Kong (Chan et al. 1998), Japan (Erffmeyer et al. 1999), Singapore (Ang et al. 2001), and Indonesia (Arli and Tjiptono 2014; Lu and Lu 2010). The present study applied the Muncy–Vitell consumer ethics scale to Chinese consumers to provide empirical evidence in support of the generalizability of the Muncy–Vitell consumer ethics model outside of North America.

Collectivism

Collectivism presents a unique problem with respect to the level of analysis because the construct has been conceptualized as both a societal-level (Hofstede 1984; House et al. 1997) and individual-level (Earley 1993; Husted and Allen 2008) variable and has been applied to countries or groups to examine ethical decision-making. Husted and Allen (2008) mentioned, in particular, a lack of research into the micro-level effect of collectivism on ethical behavior. Hence, the present study operationalized this dimension at the individual level to explore the role of individual perceptions of collectivism on consumer ethical decision-making.

According to Hofstede (1997), collectivism refers to valuing group beliefs instead of individual beliefs. A society oriented toward collectivism is typically characterized by strong social networks such as large families, patriarchal clans, and groups composed of colleagues. In a collectivist culture, people believe in group decision-making (Hofstede 1980) and treat the group interest as the priority throughout their lives to maintain loyalty-based ties (Hofstede 1997; Hofstede and Bond 1988; Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck 1961; Hofstede et al. 2010).

In a collectivist culture, the concept of fairness exists only with respect to those outside the group (such as strangers). Concerning those inside the group, equality is the guiding principle (Triandis 1994a, b). Hence, in such a culture, the ingroup emphasizes sharing (Hofstede 1997; Swinyard et al. 1990) as well as following the ethical regulations and standards constructed by the society (Vitell et al. 1993).

Few studies have directly discussed the effect of collectivism on consumer ethics; thus, the relationship between the two can only be inferred. Yoo and Donthu (2002) suggested that collectivists are more likely to adhere to marketing ethics than individualists. More recently, Paul et al. (2006) found a direct relationship between collectivism and marketing ethics. They suggested that managers with a stronger sense of collectivism are more ethical. Swaidan (2012) also found that consumers who score high in collectivism are more likely to reject questionable activities than consumers who score low in collectivism. On the basis of the empirical findings, we expect a positive relationship between collectivism and consumer ethics. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1

Collectivism is a positive determinant of consumer ethical beliefs regarding the (a) ACTIVE; (b) PASSIVE; (c) DECEPTIVE; and (d) NOHARM dimensions.

Attitude Toward Business

People’s behaviors are the outcomes of their attitudes. An original study conducted by Vitell and Muncy (1992) suggested that individual attitudes are critical to understanding consumer ethical decision-making. On the basis of various dimensions found in real life, they divided general attitudes into attitudes toward business, salespeople, government, mankind, and illegal acts. However, only a few researchers have considered these consumer attitudinal attributes since the original Vitell and Muncy (1992) study.

Among the various consumer attitudinal attributes, attitude toward business was the one most frequently examined in consumer ethics studies. Vitell et al. (2007) used consumer attitude toward business as an independent variable and found that it is a significant determinant of the passive dimension of ethical dilemmas in consumption situations. The authors suggested that a person’s attitude toward business is related to his or her ethical beliefs regarding questionable consumer situations. However, consumers whose attitude toward business was more negative were less likely to regard various questionable practices as unethical. In a later study, Patwardhan et al. (2012) found that attitude toward business was a significant predictor of PASSIVE consumer behaviors for Anglo-Americans, but not for Hispanics. Furthermore, attitude toward business was a significant predictor of the NOHARM dimension of consumer behavior for Hispanics, but not for Anglo-Americans. Hence, studies on the influence of attitude toward business on consumer ethics have produced mixed results, suggesting a need for further investigation. In the present study, consistent with Vitell and Muncy (1992), we expected that consumers with a more positive attitude toward business are more likely to reject questionable consumer activities. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2

Attitude toward business is a positive determinant of consumer ethical beliefs regarding the (a) ACTIVE; (b) PASSIVE; (c) DECEPTIVE; and (d) NOHARM dimensions.

Religious Beliefs

Previous research concerning the effects of religion on ethical behavior tended to rely on limited sample sizes based on convenience sampling, and in particular on undergraduate and MBA student samples (Parboteeah et al. 2008; Vitell et al. 2007). Sedikides (2010) observed that religion is a crucial matter worldwide. Many studies have demonstrated that religion influences a person’s ethical judgments, ethical intentions, and behaviors (Terpstra et al. 1993; Vitell 2009). Singhapakdi et al. (2013) found that religiosity has a significant effect on ethical intentions in marketing situations.

According to the Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism survey conducted by WIN-Gallup International (2012) using data from a sample of more than 50,000 people in 57 countries, China has the highest percentage of atheists (47 %) in the world. According to the survey results, only 14 % of Chinese respondents reported that they consider themselves religious, and among these people, most were Buddhist and Taoist. According to these findings, it might be inappropriate to measure Chinese religious beliefs by using the two facets of religious motivation referred to as intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity.

Smith (1998) indicated that there are two types of religion surveys in the United States: one that gathers data from church attendance numbers to measure the status of religion, and one that relies on asking respondents directly about their religious beliefs. The present study examined religion by determining how individuals perceive themselves vis-a-vis the religious beliefs that they hold instead of considering the concept in terms of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity. Thus, we expect that self-identification as a religious believer has a positive relationship with consumer ethical beliefs. According to the theoretical and empirical literature, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3

Religion is a positive determinant of consumer ethical beliefs regarding the (a) ACTIVE; (b) PASSIVE; (c) DECEPTIVE; and (d) NOHARM dimensions.

Methodology

Sample

Tuncalp (1988) found that convenience sampling is appropriate for research that is designed to gain an understanding of final consumers and their behavior. Previous studies on consumer ethics have also used convenience samples (e.g., Al-Khatib et al. 1997; Lu and Lu 2010; Rawwas 1996; Rawwas et al. 1994). Given the lack of a dependable postal service in China, data were collected through convenience sampling from 10 Taiwan-based small and medium enterprises located in Guangdong and Fujian provinces, China. Guangdong and Fujian are the main provinces where Taiwan-based enterprises have investments in China. Questionnaires were forwarded to executives of Taiwan-based companies with favorable guanxi (i.e., personal networking connections) with the authors to distribute the questionnaires. A total of 450 questionnaires (including an explanation letter and a return envelope) were hand-delivered to Chinese office workers by company managers.

The original questionnaire items were in English. A back translation technique was applied. Specifically, constructs with multi-item measures were translated into Chinese by one of the researchers, and the Chinese version was then translated back into English by another researcher who was fluent in both Chinese and English. The two English versions were discussed and compared. Any variation in the meanings of the original items resulted in rewording and refining the Chinese questionnaire. Several iterations were performed to ensure the authenticity of the translation.

The completed questionnaires (in sealed envelopes) were returned to the management departments of the enterprises. After 166 invalid questionnaires with incomplete responses were eliminated, a total of 284 valid samples remained, producing a valid return rate of 63.11 %. The majority of the respondents were female (63.4 %), were under 35 years old (89.1 %), had no religious beliefs (72.9 %), had an educational level of college or higher (53.2 %), and had an average personal income per month of less than RMB 2,500 (70.1 %). Table 1 lists the detailed demographic information of the respondents.

Measurement of the Constructs

The questionnaire contained four parts. The first part was the Muncy–Vitell Questionnaire (MVQ), which is used to explore consumer decision-making in controversial ethical situations. The MVQ measures consumer beliefs by using 22 consumer descriptions that have potential ethical implications (Muncy and Vitell 1992). The MVQ has been applied in many ethical studies, which have demonstrated its reliability and validity. Moreover, past research has supported the four factors validated by the MVQ (Al-Khatib et al. 1995, 2005; Ang et al. 2001; Chan et al. 1998; Dodge et al. 1996; Erffmeyer et al. 1999; Fullerton et al. 1996; Gardner 1999; Lascu 1993; Muncy and Vitell 1992; Rawwas 1996, 2001). A 5-point Likert scale was used for measurement, with a higher score indicating a higher level of ethical beliefs.

The second part of the questionnaire measured the respondents’ degree of collectivism. This measurement scale was developed by Hofstede (1984, 1997) and modified by Blodgett et al. (2001). The respondents rated their level of agreement with given statements on a 5-point scale, with a higher score indicating a higher degree of collectivism.

The third part of the questionnaire measured the respondents’ general attitude toward business, a variable that was included in the original Muncy and Vitell (1992) study; however, no related study has examined the reliability of the scale. All statements were adopted directly from the Muncy and Vitell (1992) study. Three statements were used to evaluate the respondents’ attitude toward business. The respondents rated their level of agreement with the statements on a 5-point scale, with a higher score indicating a more positive consumer attitude toward business.

The fourth part of the questionnaire measured the respondents’ demographic information, including their religious affiliation (Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, Catholicism, or other).

Data Analysis and Results

Reliability and Validity of Research Constructs

Data analysis was conducted using a two-stage methodology involving a measurement model and a structural model, as recommended by McDonald and Ho (2002). The first step in the data analysis was to assess the construct validity for the six measurement elements (i.e., ACTIVE, PASSIVE, DECEPTIVE, NOHARM, collectivism, and attitude toward business) by performing LISREL confirmatory factor analysis. The adequacy of the measurement model was evaluated according to the criteria of reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Reliability assesses the extent to which varying approaches construct measurements and yield the same results (Campbell and Fiske 1959), and composite reliability (CR) is used to examine the reliability. As shown in Table 2, all of the CR values were greater than the common acceptance level of 0.60 (Bagozzi and Yi 1988), except that for the attitude toward business scale (CR = 0.56).

The convergent validity of the measurement scales was evaluated using two criteria suggested by Jöreskog and Sörbom (1989): (a) all indicator factor loadings (λ) should be significant and exceed 0.45, and (b) the average variance extracted (AVE) by each construct should exceed 0.50. All λ values were higher than the 0.45 benchmark in this study. As shown in Table 2, most AVEs were greater than 0.5, except those for the collectivism and attitude toward business scales, both of which had AVE values (0.44 and 0.41, respectively) slightly below the required minimum criterion of 0.5. Hatcher (1998) proposed that even if the AVE of one or two of the constructs is less than 0.5, the convergent validity can still be considered acceptable. Therefore, the convergent validity was deemed acceptable in the present study.

Discriminant validity assesses the extent to which a concept and its indicator differ from another concept and its indicators (Bagozzi and Phillips 1991). The discriminant validity of the measures was assessed using the guidelines suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981); namely, the square root of the AVE for each construct should exceed the correlation between that and any other construct. Table 2 lists the correlation matrix, with the correlations among the constructs and the square root of the AVE on the diagonals. The diagonal values exceeded the inter-construct correlations; hence, the measures met the standard for discriminant validity.

Model Testing Results

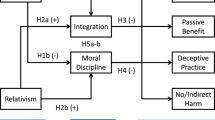

Four separate models were tested to examine the relationships among the three independent variables (collectivism, attitude toward business, and religious beliefs) and the four dimensions of consumer ethics (ACTIVE, PASSIVE, DECEPTIVE, and NOHARM) as the dependent variables. Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypothesized relationships in the research model. For models with a good fit, the Chi-square normalized by degrees of freedom (χ 2/df) should not exceed 5, and the non-normed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and goodness-of-fit index (GFI) should exceed 0.9 (Bentler 1983, 1988; Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hayduk 1987). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be less than 0.8 (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993). For the four structural models (see Table 3), χ 2/df was 1.555, 1.556, 1.472, and 1.869; the NNFI was 0.955, 0.956, 0.933, and 0.916; the CFI was 0.968, 0.973, 0.964, and 0.949; the GFI was 0.964, 0.973, 0.981, and 0.969; and the RMSEA was 0.044, 0.044, 0.041, and 0.055. In summary, the overall results suggest that the research model provided an adequate fit to the data.

Table 4 shows the standardized LISREL path coefficients. All paths were significant between collectivism and the four dimensions of consumer ethical beliefs (β = 0.308, 0.522, 0.248, 0.255; t = 2.813, 4.185, 1.963, 2.490). The signs of the beta weights were all in the expected direction. Therefore, H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d were supported.

As shown in Table 4, the paths between attitude toward business and the four dimensions of consumer ethics were significant for one of the four dimensions. The path between attitude toward business and PASSIVE was significant (β = 0.522; t = 2.813). Thus, H2b was supported. The paths between attitude toward business and ACTIVE (β = −0.004, t = −0.026), attitude toward business and DECEPTIVE (β = −0.160, t = −0.985), and attitude toward business and NOHARM (β = 0.022, t = 0.132) were not significant. Hence, H2a, H2c, and H2d were not supported.

Furthermore, the paths between religious beliefs and the four dimensions of consumer ethics were significant for one of the four dimensions. The path between religious beliefs and ACTIVE was significant (β = 0.263, t = 2.734). Thus, H3a was supported. The paths between religious beliefs and PASSIVE (β = −0.007, t = −0.284), religious beliefs and DECEPTIVE (β = 0.041, t = 1.538), and religious beliefs and NOHARM (β = -0.052, t = −1.898) were not significant. Hence, H3b, H3c, and H3d were not supported. The results of the hypothesis testing are shown in Table 4.

Conclusions and Implications

This study makes several contributions to the understanding of the relationships among collectivism, attitude toward business, religious beliefs, and consumer ethics. The present empirical survey demonstrates four major results. First, the four dimensions of consumer ethics ranked according to the mean from the highest to lowest are ACTIVE, DECEPTIVE, PASSIVE, and NOHARM. This suggests that Chinese consumers perceived actively benefiting from an illegal activity as unethical and unacceptable behavior. This result is consistent with previous studies suggesting that actively benefiting from an illegal activity is generally considered unethical and wrong. In addition, the Chinese consumers considered DECEPTIVE activities to be more unethical or wrong than PASSIVE activities. This is not surprising, considering that actively benefiting from deceptive legal activities entails active deception, even if the activity in question is not illegal per se. PASSIVE activities were generally considered to be ethical. The NOHARM dimension was the most acceptable to Chinese consumers among the four dimensions considered. This result is consistent with previous research that found that NOHARM activities were generally perceived to not be harmful to others (Vitell 2009). In summary, Chinese people maintain high ethical standards in relation to obviously illegal behaviors, but may relax their standards regarding less readily observable behaviors.

Second, collectivism was a significant factor in determining consumer ethical beliefs for all four dimensions. As anticipated, the results revealed that consumers with a stronger collectivist orientation were more likely to regard questionable consumer activities as wrong or unethical. This result is consistent with the findings of Swaidan (2012), who suggested that consumers high in collectivism are more sensitive to questionable consumer activities than those who demonstrate low collectivism. This is probably because collectivists pay attention to other perspectives and treat group norms as the standard by which to measure behavior. Apparently, Chinese consumers who are highly collectivist are more likely to reject questionable consumer practices. In the context of collectivism, people feel that they are members of an extended family, and the welfare of the group is more crucial than personal benefit (Hofstede et al. 2010). Swaidan (2012) proposed that socially responsible companies are more readily accepted by collectivists, because they are suited to collectivist cultural traits. If international marketers in China were to establish a positive corporate image with group interests as the foundation, Chinese consumers would be attracted because of their highly collectivist nature; thus, these companies can gain regarding consumer recognition. Consequently, the results of this study suggest that multinational corporations in China should take the initiative to contribute to the community and consider how well their corporate reputation corresponds to collectivist cultural traits to reduce unethical consumer behaviors and to develop better strategies.

Third, attitude toward business was significant only in determining consumer ethical beliefs regarding the PASSIVE dimension. This is consistent with Vitell et al. (2007) and Patwardhan et al. (2012), who found that attitude toward business was only significantly associated with the PASSIVE dimension of the consumer ethics scale. The mean of the attitude toward business dimension (2.90) indicates that Chinese consumers have a slightly negative attitude toward business in general. This may explain why attitude toward business was generally unrelated to the various consumer practices. As Tian and Keep (2002) observed, consumers engage in unethical behavior not only because of their individual ethical beliefs but also because they are affected by instances of corporate misconduct such as a company providing poor quality products, information asymmetry, or unfair pricing. When customers trust a specific company, they are less likely to abuse and undermine the long-term relationship that exists between them and the company and are more likely to refrain from unethical consumer behavior.

Finally, Chinese consumers’ religious beliefs significantly explained only their ethical beliefs for the ACTIVE dimension, as almost all survey respondents regarded these activities as being wrong. However, religious beliefs were not a determinant of the three other consumer ethics dimensions (i.e., PASSIVE, DECEPTIVE, NOHARM). Apparently, religious orientation had very little influence on respondent perceptions of various questionable consumer practices. The Chinese government advocated atheism and outlawed the practice of religion before the economic reforms of the late 1970s. Although the government permitted the practice of religion after the reforms, various restrictions such as banning free missionary work were established and enforced. According to the Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism survey conducted by WIN-Gallup International (2012), only 14 % of Chinese respondents reported that they consider themselves religious. The high percentage of atheists in China may explain why the dimension of religious beliefs was generally unrelated to the various consumer behaviors. Yao and Zhao (2010) explained that Chinese culture has been molded by three philosophical traditions: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. For Chinese people, Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism are not religions but philosophical teachings. Most scholars believe that Chinese people are less concerned with religion than people of other countries are (Adler 2014; Yao and Zhao 2010). In particular, Confucian culture attaches great importance to the basic goodness of people, and this has some bearing on Chinese consumers making ethical decisions (Yao 2000). It might be worthwhile for future studies to examine the effect of Confucianism on various questionable consumer practices.

Limitations are inevitable in any study on cross-cultural ethics. First, concerns related to self-reporting are a common problem in the questionnaire survey process and were inevitable in this study. Future studies can introduce additional variances to the results to address this methodological concern. By contrast, some respondents may have provided what they perceived to be socially desirable responses to appear more ethical (Al-Khatib et al. 2005). As Hofstede (1980) reported, the Chinese have a strong cultural motivation toward group conformity and a concern with “saving face.” To save face, Chinese people may make decisions according to peer pressure and group norms. The social desirability bias may have thus been a factor in the responses to some questions about ethical judgments. To control for such a bias, future studies should examine the inclusion of social desirability measures. The sample size of this study also limited the generalizability of the findings. Before the economic reforms in China, religious beliefs were forbidden, and most Chinese are therefore atheists. Among the sample of this study, only 27.1 % of the respondents reported having religious beliefs; hence, sampling such a small proportion of the population might have resulted in a statistical bias. Future studies should investigate larger random samples in China. Finally, only a small percentage of the variance was explained for some of the consumer ethics dimensions. Further studies should determine additional variables to facilitate explaining more of the variance in consumer ethics dimensions.

References

Adler, J. A. (2014). Confucianism as a religious tradition: Linguistic and methodological problems. Ohio: Kenyon College Gambier.

Al-Khatib, J., Dobie, K., & Vitell, S. J. (1995). Consumer ethics in developing countries: An empirical investigation. Journal of Euro-Marketing, 4, 87–105.

Al-Khatib, J., Rawwas, M. Y. A., Swaidan, Z., & Rexeisen, R. J. (2005). The ethical challenges of global business to business negotiations: An empirical investigation of developing countries, marketing managers’. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 13(4), 46–60.

Al-Khatib, J. A., Vitell, S. J., & Rawwas, M. Y. A. (1997). Consumer ethics: A Cross-cultural investigation. European Journal of Marketing, 31(11/12), 750–767.

Ang, S. H., Cheng, P. S., Lim, E. A. C., & Tambyah, S. K. (2001). Spot the difference: Consumer responses towards counterfeits. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(3), 219–235.

Arli, D., & Tjiptono, F. (2014). The end of religion? Examining the role of religiousness, materialism and long-term orientation on consumer ethics in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(3), 385–400.

Bagozzi, R., & Phillips, L. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421–458.

Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal Academy Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94.

Bentler, P. M. (1983). Some contributions to efficient statistics in structural models: Specification and estimation of moment structures. Psychometrika, 48, 493–517.

Bentler, P. M. (1988). Theory and implementation of EQS: A structural equations program. Newbury Park: Sage.

Blodgett, J. G., Lu, L., Rose, G. M., & Vitell, S. J. (2001). Ethical sensitivity to stakeholder interests: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(2), 190–202.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Ling (Eds.), Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park: Sage.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychology Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105.

Chan, A., Wong, S., & Leung, P. (1998). Ethical beliefs of Chinese consumers in Hong Kong. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(1), 1163–1170.

Clark, J. W., & Dawson, L. E. (1996). Personal religiousness and ethical judgments: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(3), 359–372.

Dodge, H. R., Edwards, E. A., & Fullerton, S. (1996). Consumer transgression in the marketplace: Consumers. Perspectives’, Psychology and Marketing, 13(8), 821–835.

Earley, P. C. (1993). East meets west meets mideast: Further explorations of collectivistic and individualistic work groups. Academy of Management Journal, 36(2), 319–348.

Erffmeyer, R. C., Keillor, B. D., & LeClair, D. T. (1999). An empirical investigation of Japanese consumer ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(1), 35–50.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fullerton, S., Kerch, K. B., & Dodge, H. R. (1996). Consumer ethics: An assessment of individual behavior in the market place. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(7), 805–814.

Gardner, D. M., Harris, J. & Kim, J. 1999. The Fraudulent Consumer. In G. Gundlach, W. Wilkie & P. Murphy (Eds.), Marketing and Public Policy Conference Proceedings, pp. 48–54.

Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2003). Right from wrong: The influence of spirituality on perceptions of unethical business activities. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(1), 85–97.

Global Index of Religion and Atheism, Winn-Gallup International (July 25, 2012) available at: http://redcresearch.ie/wp-‐content/uploads/2012/08/RED-C-press-release-Religion-and-Atheism-25-7-12.pdf.

Hatcher, L. (1998). A Step-by-step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (3rd Printing ed.). Carry: SAS Institute Inc.

Hayduk, L. A. (1987). Structural equation modeling with LISREL: Essentials and advances. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. London: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2), 75–89.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1(2), 81–99.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill Publication.

Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1988). The confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 5–21.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

House, R. J., Wright, N. S., & Aditya, R. N. (1997). Cross-cultural research on organizational leadership: A critical analysis and a proposed theory. In P. C. Earley & M. Erez (Eds.), New perspectives in international industrial organizational psychology (pp. 535–625). San Francisco: New Lexington.

Huang, C. C., Lu, L. C., You, C. S., & Yen, S. W. (2012). The impacts of ethical ideology, materialism, and selected demographics on consumer ethics: An empirical study in China. Ethics and Behavior, 22(4), 315–331.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6(Spring), 5–15.

Hunt, D., & Vitell, J. (1993). A general theory of marketing ethics. In N. Craig Smith & J. A. Quelch (Eds.), Ethics in marketing. Homewood: Irwin.

Husted, B. W., & Allen, D. B. (2008). Toward a model of cross-cultural business ethics: The impact of individualism and collectivism on the ethical decision-making process. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(2), 293–305.

Jenner, S., MacNab, B., Briley, D., Brislin, R., & Worthley, R. (2008). Cultural change and marketing. Journal of Global Marketing, 21(2), 161–172.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1989). LISREL 7: A guide to the program and applications (2nd ed.). Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Kluckhohn, E. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Lascu, D. N. 1993, Assessing consumer ethics: Scale development considerations for international marketing. In R. Varadarajan & B. Jaworski (Eds.) Proceedings of the American Marketing Association Winter Educators Conference.

Longenecker, J. G., McKinney, J. A., & Moore, C. W. (2004). Religious intensity evangelical christianity, and business ethics: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 55, 373–386.

Lu, L. C., & Lu, C. J. (2010). Moral philosophy, materialism, and consumer ethics: An exploratory study in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(2), 193–210.

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychology Methods, 7(1), 64–82.

McGregor, J. 1992, China’s cadres bank on consumerism; to save the party, materialism is added to list of ideals. The Wall Street Journal, A6.

Muncy, J. A., & Vitell, S. J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An investigation of the ethical beliefs of the final consumer. Journal of Business Research, 24, 297–311.

Parboteeah, K. P., Hoegl, M., & CullenL, J. B. (2008). Ethics and religion: An empirical test of a multidimensional model. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(2), 387–398.

Patwardhan, A. M., Keith, M. E., & Vitell, S. J. (2012). Religiosity, attitude toward business, and ethical beliefs: Hispanic consumers in the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(1), 61–70.

Paul, P., Roy, A., & Mukhopadhyay, K. (2006). The impact of cultural values on marketing ethical norms: A study in India and the United States. Journal of International Marketing, 14(4), 28–56.

Rawwas, M. Y. A. (1996). Consumer ethics: An empirical investigation of the ethical beliefs of Austrian consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(9), 1009–1019.

Rawwas, M. Y. A. (2001). Culture, personality and morality: A typology of international consumers. Ethical Beliefs’, International Marketing Reviews, 18(2), 188–209.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., Patzer, G., & Klassen, M. (1995). Consumer ethics in cross cultural settings. European Journal of Marketing, 29(7), 62–78.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., Patzer, G., & Vitell, S. J. (1998). A cross cultural investigation of the ethical values of consumers: The potential effect of war and civil disruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(3), 435–448.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., Rajendran, K. N., & Wuehrer, G. A. (1996). The influence of world mindedness and nationalism on consumer evaluation of domestic and foreign products. International Marketing Review, 13(2), 20–38.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., Vitell, S. J., & Al-Khatib, J. (1994). Consumer ethics: The possible effects of terrorism and civil unrest on the ethical values of consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(3), 223–231.

Sedikides, C. (2010). Why does religiosity persist? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 3–6.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., Lee, D. J., Nisius, A. M., & Yu, G. B. (2013). The influence of love of money and religiosity on ethical decision-making in marketing. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 183–191.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., & Leelakulthanit, O. (1994). A cross-cultural study of moral philosophies, ethical perceptions and judgments: A comparison of American and Thai marketers. International Marketing Review, 11(6), 65–78.

Smith, C. (1998). American evangelicalism: Embattled and thriving. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Swaidan, Z. 1999, Consumer ethics and acculturation: The case of the muslim minority in the U.S. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), University of Mississippi, University. MS.

Swaidan, Z. (2012). Culture and consumer ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(2), 201–213.

Swaidan, Z., Vitell, S. J., & Rawwas, M. Y. A. (2003). Consumer ethics: Determinants of ethical beliefs of African Americans. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(2), 175–186.

Swanson, M. 1995. China Puts on a New Face. In The China business review, September–October, pp. 34–37.

Swinyard, W. R., Rinne, H., & Kau, A. K. (1990). The morality of software piracy: A Cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(8), 655–664.

Tavakoli, A. A., Keenan, J. P., & Crnjak-Karanovic, B. (2003). Culture and whistleblowing an empirical study of Croatian and United States managers utilizing Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1/2), 49–64.

Terpstra, D. E., Rozell, E. J., & Robinson, R. K. (1993). The influence of personality and demographic variables on ethical decisions related to insider trading. The Journal of Psychology, 127(4), 375–389.

Tian, K., & Keep, B. (2002). Customer fraud and business responses: Let the marketer beware. Westport: Quorum Books, Greenwood Publishing Group Inc.

Triandis, H. C. (1994a). Cross-cultural industrial and organizational psychology. In H. C. Triandis, M. D. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 4, pp. 103–172). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Triandis, H. C. (1994b). Culture and social behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Triandis, H. C., & Bhawuk, D. P. S. (1997). Culture theory and the meaning of relatedness. San Francisco: The New Lexington Press.

Tuncalp, S. (1988). The marketing research scene in Saudi Arabia. European Journal of Marketing, 5, 15–22.

Vitell, S. J. (2009). The role of religiosity in business and consumer ethics: A review of the literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 155–167.

Vitell, S. J., Lumpkin, J. R., & Rawwas, M. Y. A. (1991). Consumer ethics: An investigation of the ethical beliefs of elderly consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(5), 365–375.

Vitell, S. J., & Muncy, J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An empirical investigation of factors influencing ethical judgments of the final consumer. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(8), 585–597.

Vitell, S. J., Nwachukwu, S. L., & Barnes, J. H. (1993). The effects of culture on ethical decision-making: An application of Hofstede’s typology. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(10), 753–760.

Vitell, S. J., Singh, J. J., & Paolillo, J. G. P. (2007). Consumers Ethical beliefs: The roles of money, religiosity, and attitude toward business. Journal of Business Ethics, 73(4), 369–379.

Weaver, G. R., & Agle, B. R. (2002). Religiosity and ethical behavior in organizations: A symbolic interactionist perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 77–97.

Whitcomb, L. L., Erdener, C. B., & Li, C. (1998). Business ethical values in China and the U.S. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 839–852.

Yao, X. (2000). An introduction to confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yao, X., & Zhao, Y. (2010). Chinese religion: A contextual approach. New Your: Continuum Internation Publishing Group.

Yoo, B., & Donthu, N. (2002). The effects of marketing education and individual cultural values on marketing ethics of students. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(2), 92–103.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, CC., Lu, LC. Examining the Roles of Collectivism, Attitude Toward Business, and Religious Beliefs on Consumer Ethics in China. J Bus Ethics 146, 505–514 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2910-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2910-z