Abstract

In the current socioeconomic environment, brands increasingly need to portray societal and ethical commitments at a corporate level, in order to remain competitive and improve their reputation. However, studies that relate business ethics to corporate brands are either purely conceptual or have been empirically conducted in relation to the field of products/goods. This is surprising because corporate brands are even more relevant in the services sector, due to the different nature of services, and the subsequent need to provide a consistent high-quality customer experience across all the brand–customer interactions and touch-points. Thus, the purpose of this article is to study, at a corporate brand level and in the field of services, the effect of customer perceived ethicality of a brand on brand equity. The model is tested by structural equations, using data collected for eight service categories by means of a panel composed of 2179 customers. The test of measurement equivalence between these categories is conducted using generalizability theory. Confirmatory factor analysis marker technique is applied in order to check for common method variance. The results of the hypothesized model indicate that customer perceived ethicality has a positive, indirect impact on brand equity, through the mediators of brand affect and perceived quality. However, there is no empirical evidence for a direct effect of customer perceived ethicality on brand equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Companies operating in the services sector need strong corporate brands in order to build long-term trustworthy relationships with their customers (Dall’Olmo Riley and de Chernatony 2000). This need derives from the intangible nature of services, and the multiplicity of brand–customer touch-points and interactions that need to be carefully managed and supported at the corporate level if services brands want to deliver an outstanding customer brand experience (Iglesias et al. 2013). In addition, companies aspiring to build strong corporate brands should integrate ethics at the heart of these brands (Balmer 2001; Rindell et al. 2011). Surprisingly, however, despite the importance of corporate brands and their ethical reputation in the field of services, there is still a dearth of research in this area, demanding more attention from the academic community (Singh et al. 2012).

The growth of the services sector in developed countries (Lovelock 1999) has challenged the traditional approach to the conceptualization of brands (Berry 2000). Traditionally, brands were conceptualized from a product perspective (e.g., Aaker 1996). Accordingly, they were considered as bundles of functional and emotional perceptions (Christodoulides et al. 2006) that allowed customers to distinguish among the products of different companies (e.g., Aaker 1996). Thus, product brands made customer purchase decisions easier (Jacoby et al. 1977) and served as guarantors of product quality (Dawar and Parker 1994).

In the new approach, however, brands are defined from a services perspective as relationship partners (Fournier 1998) with own personality (Aaker 1997). According to this line of thought, customers actually pursue developing and maintaining relationships with those brands whose personalities provide them with a mean for self-expression, self-definition, and self-enhancement (Merz et al. 2009). Services brands are thus defined as relationship builders based on reciprocity and mutual exchange between the customers and the company’s employees (Dall’Olmo Riley and de Chernatony 2000). Hence, services brands provide the interfaces for customer–employee interactions, which largely influence the customer’s overall experience with the brand (Iglesias et al. 2013). When this brand experience is favorable, the customer–brand relationships will tend to be more endurable and long-term oriented (Brakus et al. 2009).

Parallel to the evolution of services brands, the literature on corporate brands has also gained attention since the 1990s (e.g., Balmer 1995, 2012a, b; Balmer and Gray 2003; Harris and de Chernatony 2001; Hatch and Schultz 2002) broadening the scope of branding to an organization level, and thereby contemplating the interactions between the brand and multiple stakeholders (Knox and Bickerton 2003). Apart from the customers and employees, these stakeholders also include suppliers, investors, citizens (Davies et al. 2010; Morsing and Kristensen 2001; Schultz et al. 2005), the environment, the local community, and economy, the business community, and the overseas community (Brunk 2010a, b). In fact, the essence of a corporate brand is an explicit covenant between these stakeholders and the firm (Balmer and Gray 2003). A strong corporate brand can lead companies to advantages such as the increase of profitability (Roberts and Dowling 2002), the decrease of costs (Deephouse 2000; Fombrun 1996), the formation of competitive barriers (Deephouse 2000; Fombrun 1996; Milgrom and Roberts 1982), the attraction of customers (Fombrun 1996) and investors (Srivastava et al. 1997), the possibility to charge premium prices (Deephouse 2000; Fombrun 1996; Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Rindova et al. 2005), and the increase of market share and stock market value (Fan 2005).

Corporate brands are more relevant in the services sector than in the field of products/goods, because of the different nature of services (Dall’Olmo Riley and de Chernatony 2000; Iglesias et al. 2013). Alike products/goods, services are intangible, heterogeneous, experiential and inseparable (Choudhury 2014; Zeithaml et al. 1985). A key difference is that while corporate product brands can offer tangible products with standardized levels of quality, the intangible nature of services makes it difficult to homogenize service quality (Berry 1980; Booms and Bitner 1981). Moreover, in the services sector, there are many more interactions and touch-points between brands and customers than in goods contexts (Grönroos 2006), where customers primarily interact with the tangible product. In the case of services, however, customers also interact with the brand employees, who are the ones able to make or break the brand (Roper and Davies 2007). Thus, the need to ensure a positive and consistent service quality across these interactions becomes essential for those corporate services brands that want to deliver a superior customer experience and build a strong brand equity (Berry 2000; Iglesias et al. 2011).

In the current socioeconomic environment, it has become relevant for brands to show societal and ethical commitment at a corporate level (Balmer 2001; Ind 1997), because an ethical brand improves corporate reputation (Fan 2005). Therefore, an increasing number of organizations have started to consider ethicality as a strategic factor for defining and promoting their brands. In the same line, morality has also become a relevant component of corporate brands (Morsing 2006). This has resulted in a growing importance of business ethics and corporate social responsibility (CSR). In fact, because they are linked in nature and objectives (see Brunk 2010a), business ethics and CSR have become strongly associated and therefore the two terms are often used in an interchangeable way (Fan 2005). There is a large body of literature focused on examining both the direct and indirect effects of CSR initiatives or ethicality on product evaluation (Brown and Dacin 1997), corporate/company evaluation (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), firm idiosyncratic risk (Luo and Bhattacharya 2009), market value and financial performance (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006), product purchase behavior or intentions (Carrigan and Attalla 2001; Luchs et al. 2010; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), and consumer trust toward the company (Swaen and Chumpitaz 2008).

Most of the previously mentioned studies have been conducted in the area of marketing, which is consistent with Fan’s (2005) observation that ethics are increasingly researched in the areas of marketing and business. However, despite the fact that ethics should be at the heart of corporate brands (e.g., Balmer 2001; Rindell et al. 2011), research on ethics in the area of branding is still scarce (Fan 2005). Among this limited research, there are a few studies at the crossroads of business ethics and corporate brand management. For example, Rindell et al. (2011) built a conceptual foundation of “conscientious corporate brands,” and defined them as those corporate brands where ethical concerns are rooted in the firm’s business strategy, value and supply chain, vision, and culture. Taking these ethical concerns as the main driver, Rindell et al. (2011) developed a model for “conscientious corporate brands,” which has been empirically validated by Hutchinson et al. (2013), and is composed of four dimensions: environmental impact, climate change, internal corporate codes of ethics, and external corporate codes of ethics. Considering ethics a key constituent of corporate brands, Hutchinson et al. (2013) suggested that “conscientious corporate brands” are so to the extent that they do not harm public good.

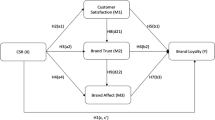

However, in spite of the above justified relevance of the corporate brands and their reputation in the field of services, the studies that link corporate brand management and business ethics are either purely conceptual (e.g., Brunk 2010b; Fan 2005; Gustafsson 2005) or have been empirically conducted in relation to the field of products/goods (e.g., Brown and Dacin 1997; Brunk 2010a; Hutchinson et al. 2013; Rindell et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2012). Accordingly, Singh et al. (2012) called for further empirical research at the crossroads of business ethics and corporate brand management in the services sector. Moreover, Singh et al. (2012) argued that in order to better comprehend whether investing in corporate brand ethics pays off, future research should empirically examine the impact of customer perceived ethicality (CPE) on brand equity. Therefore, this article aims at covering these gaps by studying, at a corporate brand level and in the field of services, the relationship between CPE and brand equity, considering the two mediating variables of brand affect and perceived quality. The model is tested with structural equations, using data collected for a wide variety of corporate services brands by means of an online customer panel.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

The Influence of CPE on Brand Affect and Perceived Quality, and the Influence of Perceived Quality on Brand Affect

The field of ethical branding represents an overlap of business ethics and brand management. An ethical brand is the one that avoids harming and promotes public good, as well as behaves with integrity, honesty, diversity, responsibility, quality, accountability, and respect (Fan 2005). Research has recurrently shown that it is in the best interest of brands to behave in an ethical way (e.g., Story and Hess 2010), because the customers increasingly expect brands to both embody and reflect their ethical interests (e.g., Maxfield 2008).

Brunk (2010a, 2012) presented a model of CPE, which can be defined as the aggregate perception that consumers have of the brand/company as acting in an ethical way. More specifically, Brunk (2012) suggested that an ethical brand/company attitude involves applying consequentialist and non-consequentialist evaluation principles, abiding by the law, respecting moral norms, being a good market actor, acting in a socially responsible way, avoiding any kind of damaging behavior, and weighing up positive and negative consequences. Furthermore, Brunk (2010a,b) identified six domains of CPE origins, which may influence the perceptions of a brand’s/company’s ethical behavior: consumer, employees, environment, local community and economy, overseas community, and business community.

In her commentary about Brunk’s (2010a) work, Shea (2010) acknowledged that, within the framework of CPE, Brunk (2010a) conceptualizes the cognitive component of the consumers’ attitude toward the ethical behavior of the companies very well. However, Shea (2010) argued that such CPE framework should be broadened to also contemplate the other two components of attitude: behavioral and affective. Singh et al. (2012) addressed this concern by including in their framework of CPE—brand loyalty as a behavioral, and brand affect as an affective component of consumers’ attitude.

Considering that the perceptions of ethical behavior include the company’s involvement in CSR campaigns/initiatives (e.g., Godfrey 2005; Vlachos et al. 2009), Lin et al. (2011) showed that when there is a low perceived CSR, customers’ affective identification with the brand is likely to be damaged by negative publicity. Apart from this moderating effect, Lin et al. (2011) found that perceived negative publicity is negatively related to customers’ affective identification, whereas perceived CSR is a positive antecedent of customers’ affective identification. Likewise, various scholars have provided evidence for a positive influence of CSR on customers’ identification with the brand/company (e.g., Du et al. 2007; He and Li 2011; Lichtenstein et al. 2004; Lii and Lee 2012; Marin et al. 2009; Martínez and Rodríguez del Bosque 2013).

If the CSR initiatives coincide with customers’ values and self-concept, customers’ identification with the company is likely to increase, and result in their commitment to the company (Lichtenstein et al. 2004). Accordingly, Currás (2009) found that the CSR-based customer–company identification has a positive impact on customer’s commitment to the company. However, various academics have provided evidence for a direct effect of CSR on organizational commitment (e.g., Brammer et al. 2007; Lacey and Kennett-Hensel 2010; Turker 2009). Commitment actually has three components—affective, continuance, and normative (Meyer and Allen 1991), among which affective commitment is the most closely associated with CSR, in accordance with the social identity theory (Turker 2009).

In the context of corporate brands, brand affect is defined as the “brand’s potential to elicit a positive emotional response in the average consumer as a result of its use” (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001, p. 82). This positive emotional response is more likely to emerge when the customer perceives the brand as behaving in an ethical manner (Singh et al. 2012). Accordingly, Poolthong and Mandhachitara (2009) showed that CSR has a positive effect on brand affect. Similarly, considering CSR a key component of CPE (see Brunk 2010a, b), Singh et al. (2012) showed that CPE at a corporate brand level has a positive impact on product brand affect. In line with this discussion, we hypothesize that

H1

CPE of a corporate services brand has a positive effect on brand affect.

CPE, however, is not just expected to generate brand affect in the services setting. Since more than two decades ago, both researchers and managers have become increasingly interested in examining the customers’ perceptions of service quality (e.g., Boulding et al. 1993; Parasuraman et al. 1985, 1988; Zeithaml et al. 1996). Service quality has recurrently been defined as the customers’ evaluations of the superiority or excellence of the service (e.g., Bateson and Hoffman 2002; Parasuraman et al. 1988). In the literature, it is widely acknowledged that these customers’ evaluations are actually influenced by their previous expectations regarding the quality of the service (e.g., Boulding et al. 1993; Brown and Swartz 1989; Parasuraman et al. 1985, 1988).

Moreover, scholars have also proposed that quality depends on perceptions of ethical behavior (e.g., Abdul-Rahman et al. 2014; Besterfield et al. 2003). Accordingly, Enquist et al. (2007) argued that ethics promote value-based service quality. Similarly, Dandy (1996) defended that a complete honesty in the operations and communications with the customers is a route to develop service quality. Considering honesty as part of integrity, Scheuing and Edvardsson (1994) argued that there is a close link between the integrity of the service provider and service quality. Likewise, Holjevac (2008) suggested that the lack of ethics, morality, and social responsibility is a fundamental reason for low service quality in the tourism industry. In line with the previous findings that suggest that there is a positive impact of CSR on customers’ perceptions of product or service quality (e.g., García de los Salmones et al. 2005; Poolthong and Mandhachitara 2009), we postulate that

H2

CPE of a corporate services brand has a positive effect on perceived quality.

Perceived quality has often been linked in the literature with the relational construct of affective commitment. Accordingly, in relationship marketing literature, Gruen et al. (2000) proposed that core services performance is positively related to affective commitment. Gruen et al. (2000, p. 38) defined core services performance as “the extent of the quantity and quality of the planning and delivery of the association’s primary services.” Regarding the quality of services, Fullerton (2005) found empirical evidence for a direct impact of service quality on customer’s affective commitment. Similarly, in an online setting, Hsiao et al. (2015) found that e-service quality positively impacts customer’s brand commitment. In a business-to-business context, Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) showed that technical service quality and relational service quality have an indirect effect on affective commitment, mediated by satisfaction. Moreover, Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) found a direct impact of relational service quality on affective commitment. In the field of branding, Xie et al. (2015) showed that brand quality is positively related to brand affect. Finally, in the services literature, Poolthong and Mandhachitara (2009) provided empirical evidence for an indirect impact of perceived service quality on brand affect. In line with this discussion, we hypothesize that

H3

In case of a corporate services brand, perceived quality has a positive effect on brand affect.

The Influences of Brand Affect, Perceived Quality, and CPE on Brand Equity

Brand affect has not only been studied as a consequence of perceived quality, but it has also been related to brand equity (e.g., Baumgarth and Schmidt 2010; Dwivedi and Johnson 2013). Brand equity has traditionally been defined as the incremental utility or value added to a product or service due to its brand name (Park and Srinivasan 1994; Rangaswamy et al. 1993). Similarly, Yoo et al. (2000) defined brand equity as the difference in customers’ choice between a branded and a nonbranded product, given that both have the same features and characteristics. More recently, however, brand equity has been conceptualized as a relational market-based asset that is built through the interactions between the brands and their customers (e.g., Davcik et al. 2015; Hooley et al. 2005; Srivastava et al. 2001). Thus, strong customer commitment is likely to be positively associated with brand equity (Fournier 1998; Rego et al. 2009). In this line, Dwivedi and Johnson (2013) showed a direct, positive effect of relationship commitment on brand equity. Similarly, Morgan and Hunt (1994) found a direct, negative influence of such relationship commitment on propensity to leave. Likewise, Fullerton (2005) found that an affective commitment to a brand decreases the switching intentions, and Gundlach et al. (1995) proposed that the positive affect toward a brand is likely to prevent the search for alternatives.

A customer who is not likely to leave the brand, has low switching intentions, and does not look for alternatives can be considered a brand loyal customer. Accordingly, brand loyalty can be conceptualized as the customers’ strong commitment to repurchase a product or service of a brand, in spite of any contextual influences or marketing efforts of the competing brands (e.g., Oliver 1997). Thus, brand loyalty entails customers’ willingness to maintain long-term affective relationships with a brand (e.g., Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001). A great body of literature actually recognizes brand loyalty as a dimension or component of brand equity (e.g., Aaker 1996; Biedenbach et al. 2011; Kim and Kim 2004; Pappu et al. 2005, 2006).

Apart from brand loyalty, scholars have also suggested that affect (Matthews et al. 2014), emotional connection (Christodoulides et al. 2006), identification/attachment (Lassar et al. 1995), and commitment (see Martin and Brown 1990) between the customers and the brand are dimensions or components of brand equity. For example, Burmann et al. (2009) proposed a brand equity model that integrates internal and external brand strength perspectives, where brand commitment is a component of the internal brand strength (Burmann and Zeplin 2005). Accordingly, Feldwick (1996, p. 11) argued that brand equity can also be defined as “a measure of the strength of consumers’ attachment to a brand.” However, there is still scarce empirical research examining the impact of brand attachment on brand equity (Park et al. 2010). This scarce research has mainly been conducted in the field of internal branding, where Baumgarth and Schmidt (2010) showed a direct, positive impact of internal brand commitment on internal brand equity, as well as in the organization context, where Allen et al. (2011) found an interaction effect between affective organizational commitment and equity sensitivity. With the aim of gaining insight about this relationship in the area of corporate services brands, we hypothesize that

H4

In case of a corporate services brand, brand affect has a positive effect on brand equity.

Academics have also widely acknowledged perceived quality as a dimension of brand equity (e.g., Aaker 1996; Cobb-Walgren et al. 1995; Kim and Kim 2004; Kimpakorn and Tocquer 2010; Martin and Brown 1990; Netemeyer et al. 2004; Pappu et al. 2005, 2006; Yoo et al. 2000). When customers perceive the overall quality of a product/service offered by a brand as superior, they are likely to assign more value to that brand (e.g., Jahanzeb et al. 2013). Accordingly, many researchers have found evidence for both indirect and direct impacts of perceived quality on brand equity.

On the one hand, Nella and Christou (2014) found that service quality has a positive effect on satisfaction, which in turn is a positive antecedent of consumer-based brand equity. Similarly, He and Li (2010) and Jahanzeb et al. (2013) showed that the impact of overall service quality on overall brand equity is partially mediated by perceived value.

On the other hand, most research studies examining the direct impact of perceived quality on brand equity have been conducted in the field of goods (Jahanzeb et al. 2013). For instance, in the beverage industry, Atilgan et al. (2005) found weak support for the direct impact of the brand equity’s dimension of perceived quality on brand equity. Similarly, considering three different product categories (i.e., athletic shoes, camera film, and color television sets), Yoo et al. (2000) showed that the brand equity’s dimension of perceived quality had a direct and positive effect on brand equity. Finally, regarding automotive products, Murtiasih et al. (2013) found that perceived quality influenced brand equity in a positive and significant manner.

Covering the subsequent research gap in the field of services, Correia (2014), He and Li (2011), and Tsao and Tseng (2011) have recently provided evidence for a direct and positive effect of perceived quality on brand equity. Based on this line, we hypothesize that

H5

In case of a corporate services brand, perceived quality has a positive effect on brand equity.

Apart from relating brand affect and perceived quality to brand equity, scholars have also argued that the company’s ethical and socially responsible behavior is linked with its brand equity (e.g., Brickley et al. 2002; Hur et al. 2014). Accordingly, Lai et al. (2010) proposed that customer’s perceptions of the company as engaging in socially responsible activities can enhance positive brand associations and brand awareness. Similarly, Keller (2003) suggested that CSR marketing is likely to increase brand awareness. In the literature, both brand associations and brand awareness are widely recognized as dimensions or components of brand equity (e.g., Aaker 1996; Lai et al. 2010; Pappu et al. 2005, 2006; Yoo et al. 2000). Recently, in a review of the previous body of literature on CSR, Malik (2015) concluded that the engagement in CSR activities improves brand equity. From an empirical standpoint, in the context of corporate brands, Hur et al. (2014) provided evidence for a positive impact of CSR on corporate brand equity. Likewise, in a services setting, Hsu (2012) empirically showed that CSR initiatives lead to higher levels of brand equity. Finally, in a small–medium enterprises context, Lai et al. (2010) found that buyer’s perceptions of the supplier’s engagement in CSR activities have a positive impact on supplier’s industrial brand equity. In accordance with this discussion, we postulate that

H6

CPE of a corporate services brand has a positive effect on brand equity.

Methodology

Questionnaire Design and Measures

The questionnaire was designed using and adapting existing scales from the marketing literature (see Table 1). All answers were rated using a seven-point Likert scale, which ranged from “completely disagree” to “completely agree.” The survey was subjected to a double-blind back translation process so as to translate the items into Spanish.

The questionnaire was pre-tested in two ways. First, experts from the areas of brand management and business ethics were requested to assess the questions and the manner in which they were asked to avoid possible misinterpretations for the respondents. Second, some respondents were asked to evaluate the comprehension level of the questionnaire.

Sampling and Data Collection

The data were collected for the services sector by means of an online customer panel, which took place in Spain. The sample was composed of 2179 customers, who were selected by using a series of filtering questions regarding their engagement in the purchase of different service categories. The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 65, with a median of 35, and they were 50.1 % females. Table 2 shows the distribution of the sample regarding the eight service categories that are presented in our study: financial institutions, insurance companies, telephone and internet service providers, supermarket and hypermarket chains, utility companies, clothing retail chains, gas stations, and hotel chains. Each respondent was randomly assigned to one of these categories, and asked to select their top habitual corporate services brand from an extensive list of brands.

Measurement Equivalence

The dataset used in this study was collected considering multiple service categories. Hence, measurement equivalence had to be addressed to assess whether the constructs via their related scale items were invariant across these categories (Malhotra and Sharma 2008). Two prevalent approaches to test measurement equivalence that have emerged from the literature are confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Steenkamp and Baumgartner 1998) and generalizability theory (G-theory) (Cronbach et al. 1972).

Following Malhotra and Sharma (2008), we assessed the structure invariance of the constructs across the different service categories using G-theory instead of CFA, because two of the categories did not have enough cases to support CFA. G-theory examines the generalizability of the scales developed to measure latent constructs across groups of interest (i.e., eight service categories). It is essentially an approach to the estimation of measurement precision in situations where measurements are subject to multiple sources of variation. In our design, we considered five different sources of variation: items in each scale (low variation indicates item redundancy); service categories (high variation suggests that brands differ compared to the construct means); subjects within service categories (high values indicate that there is variation among subjects within groups); the interaction between service categories and items (low variation indicates that the pattern of responses is the same across groups and increases generalizability); and finally, the error and other confounding sources (low variation enhances generalizability).

We used SPSS to calculate and assess the five sources of variation and the generalizability coefficient (GC) across the eight service categories. The results of the individual sources of variation can be accepted, with the GC ranging from .84 to .97—quite high values according to Rentz (1987)—providing support for the generalizability of the scales across the different service categories (see Table 3).

Results

Construct Validation

CFA was conducted in AMOS 23 to explore the factor structure using the maximum likelihood method. The initial assessments of absolute and incremental model fit are indicative of a good fitting measurement model (χ 2/df = 2.67, RMSEA = .028, 90 % CI for RMSEA = (.022; .033), NFI = .99, CFI = .99 and SRMR = .0106). All values are within their acceptable ranges (Bollen 1989; Gerbing and Anderson 1992). Convergent validity was evaluated using the average variance extracted (AVE). This common quality requirement was met by all four constructs, whose values were higher than the threshold value of .6. Individual item’s reliability was checked using Cronbach’s alpha (ranging from .885 to .948), whereas to test the reliability of the construct, composite reliability was used. The reliability of each construct was satisfactory with a composite reliability value of at least .80. All factor loadings were significant and varied from .84 to .91, satisfying the convergent validity criterion (see Table 4). These results provide evidence for the convergent validity of the constructs used in this study. Finally, discriminant validity was analyzed comparing the squared root AVE of each construct with the correlations that this construct has with the remaining constructs. Table 4 shows that the AVE of each construct is higher than its correlations, suggesting sufficient discriminant validity. Each of the four constructs has good psychometric properties.

Since one limitation of the data is that every single respondent has provided multiple response sets, it is essential to test for unacceptable levels of common method variance (CMV). In response to this inherent single-source effect risk, this research was conducted using some best practices widely proposed in the literature regarding questionnaire design and estimation to ensure that the effect of self-report perceptions has not introduced excessive variance so as to alter our findings. Focusing on CMV issues, we considered both ex-ante remedies during the survey design (Podsakoff et al. 2003) and ex-post statistical analysis via multiple analytic tools to study and detect the potential CMV effect.

There are different types of statistical techniques proposed in the extant literature to detect and correct CMV. One well-documented set of statistical remedies for CMV is classified as partial correlation techniques (Podsakoff et al. 2003). One particular partial correlation method is the Lindell and Whitney (2001) implementation, now referred to as the correlational marker technique (Richardson et al. 2009), which has received considerable attention from researchers (e.g., Becker et al. 2009; Frazier et al. 2009; Malhotra et al. 2006; Mathwick et al. 2008; Schaller et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2010).

Williams et al. (2010) conducted a flexible implementation of the marker variable technique. The procedure involves the execution of several structural equation models and then the comparison of these models by undertaking χ 2 difference tests. In addition to the traditional CFA-based measurement model with the marker variable, Williams’ procedure involves executing the baseline model (i.e., constructs correlated with one another but not with the marker variable, with substantive items not loading on the marker variable); the method-C model (i.e., constructs correlated with one another but not with the marker variable, and items of substantive variables loading on the marker variable with equal magnitudes); the method-U model (i.e., constructs correlated with one another but not with the marker variable, with construct items loading on the marker variable with unconstrained–unequal magnitudes); the method-R model (i.e., similar model to the method-C or method-U models, but the correlations across constructs are constrained to the values present in the baseline model); and finally, appropriate model comparisons.

Following Williams et al. (2010), we implemented the structural equation analysis with latent variables or CFA marker technique analysis. Specifically, three items related to the psychological risk construct included in the questionnaire were selected to generate the latent marker variable. The model-fit results of the analysis for each model are presented in Table 5, including the χ 2, degrees of freedom (df), and comparative fit index (CFI) values. We note that the CFI values were all above the .95 threshold value. The baseline model and method-C model were compared to test the null hypothesis that the method factor loadings (expected to be equal) associated with the marker variable were not related to each of the 13 substantive indicators. The χ 2 difference test showed a not significant value of 2.58 (df = 1). The comparison of these two models revealed no conclusive results for rejecting the restriction to 0 of the 13 method factor loadings in the baseline model.

The second model comparison was conducted between the method-U and method-C models to determine if the impact of the method marker variable was equal for all of the 13 items loading on the substantive items. The comparison of these two models tested the null hypothesis that the method factor loadings are equal. The χ 2 difference testing provided support for rejecting the restrictions in the method-C model. The comparison yielded a χ 2 difference of 230.3 (df = 12), which exceeds the .05 critical value of 21.03. The method-U model, therefore, represents the best model in terms of accounting for marker variance on substantive indicators.

The completely standardized factor loadings for the method-U model are shown in Table 6. The values range from .84 to .93, and all substantive indicators load significantly (p < .05) on the constructs they aim to measure. In terms of the method factor loadings from method-U model (marker variable column), 9 of the 13 were statistically significant at the p < .05 level, indicating that those items were contaminated by a source of method variance detected by the marker variable. The highest magnitude of factor loadings between significant values was .124. The square of this value indicates that the maximum amount of marker variance in each indicator was 1.5 %. Significant method factor loadings were associated with items related with the four substantive factors analyzed.

The last executed model was the restricted model or the method-R model. This model is exactly the same as the method-U model except for the substantive factor correlation parameters that we fixed using the values obtained in the baseline model. The comparison of the method-U and method-R models provides a statistical test to check whether the six correlations were significantly biased by the marker variable method effects. The χ 2 difference test resulted in a not significant difference of .28 (df = 5). Previous tests indicated that the marker variable effect was significant in the method-U model, but the result of the comparison between method-U and method-R models determined that the effects of the marker variable did not significantly bias factor correlation estimates. As presented in Table 7, there were no significant differences between the estimated correlations of the substantive constructs among the baseline and the method-U models. Finally, all the followed procedures did not suggest any significant common method bias.

Structural Model

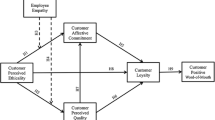

According to our hypotheses, a structural equation model was developed to assess the statistical significance of the proposed relationships between brand equity, brand affect, perceived quality, and CPE (see Fig. 1). All the fit measures indicated that the structural model is acceptable (χ2/df = 2.73, RMSEA = .028, 90 % CI for RMSEA = (.023; .034), NFI = .99, CFI = .99 and SRMR = .0104). Along with the model’s general fit for the data, its parameters were tested to decide whether to accept the proposed relationships between exogenous and endogenous constructs. The standardized regression weights (see Table 8) showed that five out of the six hypotheses proposed in our model were supported. CPE has significant and positive effects on both brand affect and perceived quality. Brand affect and perceived quality both have positive and significant impacts on brand equity. Perceived quality has a significant and positive effect on brand affect. Despite the fact that results provide strong support for the positive and direct effects associated with hypotheses H1 to H5, the direct effect of CPE on brand equity (H6) is not significant.

Indirect effects analysis was performed via bootstrapping procedure using 5000 samples. Cheung and Lau (2008) established that structural equation modeling provides unbiased estimates of mediation and suppression effects, and that the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals perform best in testing for mediation and suppression effects. Table 9 summarizes the results regarding the significance of the direct and indirect effects.

The standardized indirect effect of CPE on brand equity through perceived quality was .36. The 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval was between .51 and .64 with a p < .001 for two-tailed significance test. As the direct effect of CPE on brand equity controlling for the mediating variable of perceived quality was also significant, perceived quality is a partial mediator. Finally, the standardized indirect effect of CPE on brand equity through brand affect was .501 and significantly different from zero (p < .001; two-tailed). The bootstrap approximation obtained by constructing a two-sided bias-corrected 95 % confidence interval was between .461 and .542. As the direct path from CPE to brand equity controlling for brand affect was not significant, brand affect is a full mediator of the impact of CPE on brand equity.

Discussion and Conclusion

Theoretical Contributions

The findings from this study provide relevant contributions to the fields of brand management and business ethics, because to the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical research that has studied the effects of CPE in the context of corporate services brands, and thereby responds to the call from Singh et al. (2012) to conduct empirical work at the under-researched crossroads of business ethics and corporate services brands. Previous studies that link business ethics and corporate brand management are either purely conceptual (e.g., Brunk 2010b; Fan 2005; Gustafsson 2005) or have been empirically conducted in relation to the field of products/goods (e.g., Brown and Dacin 1997; Brunk 2010a; Hutchinson et al. 2013; Rindell et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2012). Hence, this article implies a novel and relevant contribution, because ethical corporate brands are especially relevant in the field of services, as they act as a guarantee that reduces the associated risk that customers perceive when purchasing services, due to their intangible nature (Berry 1983; Dall’Olmo Riley and de Chernatorny 2000). Moreover, if services companies want to deliver an outstanding customer experience, they need strong corporate brands capable of defining a valuable proposition and aligning the different stakeholders involved in the experience delivery (Iglesias et al. 2013).

Second, the results of our hypothesized structural model show that the direct effect of CPE on brand equity is not significant. This finding differs from prior research in the goods context, where a direct impact of the customer perceived ethical or socially responsible behaviors of a firm or a corporate brand on brand equity has been empirically shown (e.g., Hur et al. 2014; Lai et al. 2010). Thus, our result theoretically implies that, in the services sector, perceived quality and brand affect are crucial for translating CPE into brand equity.

In addition, the findings of the present research show that when customers have positive perceptions of service quality they develop brand affect, which in turn enhances brand equity. This highlights the central role of perceived quality in the context of corporate services brands in comparison to corporate product brands, where perceived quality plays a less relevant role. This is due to the fact that services are intangible and heterogeneous in nature (Zeithaml et al. 1985), and therefore, it is more difficult for corporate services brands to recurrently deliver a uniform level of quality (Berry 1980; Booms and Bitner 1981), as well as it is more difficult for customers to establish a clear quality-evaluation criterion (Athanassopoulos et al. 2001). Moreover, because of the greater number of interactions and touch-points that customers have with corporate services brands than it is the case in goods contexts (Grönroos 2006), assuring a positive and consistent perceived quality across these interactions and touch-points becomes crucial for building a superior customer experience with the brand (Iglesias et al. 2011). Hence, perceived quality should be a central concern for those corporate services brands willing to convert the CPE into brand equity. However, to our knowledge, no previous research has empirically examined this central position of perceived quality in the relationship between CPE of a corporate services brand and brand equity.

Our findings support the need to invest in high-quality service experiences (Lassar et al. 1995) and in developing the affective commitment of customers (Singh et al. 2012) if corporate services brands want to leverage on their investments in ethicality. Moreover, when customers are affectively committed to a brand, they are likely to attribute potential service failures to external factors or even to themselves, thereby becoming less sensitive to the poor service performance (Story and Hess 2010). Despite its subsequent importance in the area of services, to our knowledge, as it is the case with perceived quality, no previous research has studied brand affect as a mediator of the effect of CPE on brand equity. Thus, our study presents novel contributions showing that both perceived quality and brand affect are relevant mediators of the impact of CPE on brand equity, in the services sector. This further emphasizes the differences of corporate services brands and how they need to be managed compared to corporate product brands.

Managerial Implications

The findings from this research have important implications for the managers of services companies. First, the indirect impact of CPE on brand equity implies that there is a return on investment for those companies perceived by the customers to operate in an ethical manner, and that engage in ethical practices or CSR initiatives that match their customers’ moral identities and ethical concerns. Moreover, the current hyperconnected environment, where the different stakeholders easily detect an unreal or profit-seeking ethical behavior, and rapidly propagate this information through their multiple online and offline networks, pushes even more brands to embrace authentic ethical behaviors and practices.

Second, in the field of services, customers’ perceptions of a corporate brand’s ethicality are fundamentally built during the customer–brand touch-points, due to the inseparability of the production and consumption of a service. Hence, apart from conducting ethical and CSR campaigns, it becomes crucial for managers of corporate services brands to embed these ethical and CSR initiatives in every single customer–brand touch-point. Thus, managers should transfer these ethical and CSR concerns to the daily behavior of their employees, and ensure that they understand and embody this ethically oriented brand vision, because the employees are those who will interact with the customers during the service encounters, and thereby shape the customers’ brand experiences. Therefore, managers should put special focus on the training and alignment of the employees of the brand.

Finally, managers ought to work on developing and improving customers’ emotions and affect toward the brand, as well as customers’ perceptions of the quality of the services provided by the brand. This is a crucial condition that enables to turn customers’ perceptions of the brand’s ethicality into a higher level of brand equity.

Limitations and Future Research

This research has some limitations as well. First, the external validity of the findings is an issue, because the sample is only representative of the Spanish target population. Therefore, future research could replicate this study in different countries, so as to enhance the generalizability of the findings and examine whether customers’ perceptions of a corporate brand’s ethicality are more important in developed or emerging economies. Second, mono-method bias is an issue, because data were collected only through surveys, and the variables were measured using the already existent scales in the literature. Hence, future research could develop new measures and apply multiple methods. Third, although this study includes eight service categories, which provides a comprehensive view of the services sector, future research could extend this list of categories in order to obtain even more generalizable findings in the field of services. Fourth, this research only focuses on the attitudinal consequences of CPE. Future research could compare these results to more objective data from the sales/market share metrics.

Apart from dealing with the limitations of the current study, future research could also compare the effect of CPE in the fields of goods and services. In addition, it would also be interesting to examine other widely accepted brand equity dimensions (i.e., brand loyalty, brand awareness, and brand associations) as mediators of the relationship between CPE and brand equity. Moreover, brand attitude could be also an interesting mediator, because it is a behavioral construct, and therefore it would add on the affective one (i.e., brand affect) already used in this research. Namely, future research could investigate which brand attitudes does CPE generate, and how these behaviors impact brand equity.

Abbreviations

- AVE:

-

Average variance extracted

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- CMV:

-

Common method variance

- CPE:

-

Customer perceived ethicality

- CSR:

-

Corporate social responsibility

- df :

-

Degrees of freedom

- GC:

-

Generalizability coefficient

- G-theory:

-

Generalizability theory

References

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102–120.

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356.

Abdul-Rahman, H., Hanid, M., & Yap, X. W. (2014). Does professional ethics affect quality of construction—A case in a developing economy? Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 25(3–4), 235–248.

Allen, R. S., Evans, W. R., & White, C. S. (2011). Affective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior: Examining the relationship through the lens of equity sensitivity. Organization Management Journal, 8(4), 218–228.

Athanassopoulos, A., Gounaris, S., & Stathakopoulos, V. (2001). Behavioural responses to customer satisfaction: An empirical study. European Journal of Marketing, 35(5/6), 687–707.

Atilgan, E., Aksoy, S., & Akinci, S. (2005). Determinants of the brand equity: A verification approach in the beverage industry in Turkey. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 23(3), 237–248.

Balmer, J. M. T. (1995). Corporate branding and connoisseurship. Journal of General Management, 21(1), 24–46.

Balmer, J. M. T. (2001). The three virtues and seven deadly sins of corporate brand management. Journal of General Management, 27(1), 1–17.

Balmer, J. M. T. (2012a). Corporate brand management imperatives: Custodianship, credibility and calibration. California Management Review, 54(3), 6–33.

Balmer, J. M. T. (2012b). Strategic corporate brand alignment: Perspectives from identity based views of corporate brands. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7), 1064–1092.

Balmer, J. M. T., & Gray, E. R. (2003). Corporate brands: What are they? What of them? European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 972–997.

Bateson, J. E., & Hoffman, K. G. (2002). Essential of service marketing: Concepts, strategy, and cases. Harcourt, 19(4), 491–504.

Baumgarth, C., & Schmidt, M. (2010). How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically-tested model of ‘internal brand equity’ in a business-to-business setting. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(8), 1250–1260.

Becker, J. U., Greve, G., & Albers, S. (2009). The impact of technological and organizational implementation of CRM on customer acquisition, maintenance, and retention. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(3), 207–215.

Berry, L. L. (1980). Services marketing is different. Business, 30(3), 24–29.

Berry, L. L. (1983). Relationship marketing. In L. L. Berry, G. L. Shostack, & G. D. Upah (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on services marketing (pp. 25–28). Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Berry, L. L. (2000). Cultivating service brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 128–137.

Besterfield, D. H., Michna, C. B., Besterfield, G. H., & Sacre, M. B. (2003). Total quality management. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Biedenbach, G., Bengtsson, M., & Wincent, J. (2011). Brand equity in the professional service context: Analyzing the impact of employee role behavior and customer–employee rapport. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(7), 1093–1102.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.

Booms, B. H., & Bitner, M. J. (1981). Marketing strategies and organization structures for service firms. Marketing of Services, 25(3), 47–52.

Boulding, W., Kalar, A., Staelin, R., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1993). A dynamic process model of service quality: From expectation to behavioral intentions. Journal of Marketing Research, 30, 7–27.

Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719.

Brickley, J. A., Smith, C. W, Jr, & Zimmerman, J. L. (2002). Business ethics and organizational architecture. Journal of Banking & Finance, 26(9), 1821–1835.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. The Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Brown, S. W., & Swartz, T. A. (1989). A gap analysis of professional service quality. The Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 92–98.

Brunk, K. H. (2010a). Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 255–262.

Brunk, K. H. (2010b). Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—Reply to Shea and Cohn’s commentaries. Journal of Business Research, 63(12), 1364–1367.

Brunk, K. H. (2012). Un/ethical company and brand perceptions: Conceptualising and operationalising consumer meanings. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(4), 551–565.

Burmann, C., Jost-Benz, M., & Riley, N. (2009). Towards an identity-based brand equity model. Journal of Business Research, 62(3), 390–397.

Burmann, C., & Zeplin, S. (2005). Building brand commitment: A behavioural approach to internal brand management. The Journal of Brand Management, 12(4), 279–300.

Carrigan, M., & Attalla, A. (2001). The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(7), 560–578.

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93.

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11, 296–325.

Choudhury, K. (2014). Service quality and word of mouth: A study of the banking sector. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 32(7), 612–627.

Christodoulides, G., De Chernatony, L., Furrer, O., Shiu, E., & Abimbola, T. (2006). Conceptualising and measuring the equity of online brands. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(7–8), 799–825.

Cobb-Walgren, C. J., Ruble, C. A., & Donthu, N. (1995). Brand equity, brand preference, and purchase intent. Journal of Advertising, 24(3), 25–40.

Correia, S. M. (2014). The effect of perceived benefits, trust, quality, brand awareness/associations and brand loyalty on internet banking brand equity. International Journal of Electronic Commerce Studies, 4(2), 139–158.

Cronbach, L. J., Gleser, G. C., Nanda, H., & Rajaratnam, N. (1972). The dependability of behavioral measurements: Theory of generalizability for scores and profiles. New York: Wiley.

Currás, R. (2009). Effects of perceived identity based on corporate social responsibility: The role of consumer identification with the company. Corporate Reputation Review, 12(2), 177–191.

Dall’Olmo Riley, F., & de Chernatony, L. (2000). The service brand as relationships builder. British Journal of Management, 11(2), 137–150.

Dandy, J. (1996). The ethical route to service quality at John Lewis Partnership. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 6(5), 17–19.

Davcik, N. S., Da Silva, R. V., & Hair, J. F. (2015). Towards a unified theory of brand equity: Conceptualizations, taxonomy and avenues for future research. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 24(1), 3–17.

Davies, G., Chun, R., & Kamins, M. A. (2010). Reputation gaps and the performance of service organizations. Strategic Management Journal, 31(5), 530–546.

Davis-Sramek, B., Droge, C., Mentzer, J. T., & Myers, M. B. (2009). Creating commitment and loyalty behavior among retailers: What are the roles of service quality and satisfaction? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(4), 440–454.

Dawar, N., & Parker, P. (1994). Marketing universals: Consumers’ use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality. The Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 81–95.

Deephouse, D. L. (2000). Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1091–1112.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(3), 224–241.

Dwivedi, A., & Johnson, L. W. (2013). Trust–commitment as a mediator of the celebrity endorser–brand equity relationship in a service context. Australasian Marketing Journal, 21(1), 36–42.

Enquist, B., Edvardsson, B., & Petros Sebhatu, S. (2007). Values-based service quality for sustainable business. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 17(4), 385–403.

Fan, Y. (2005). Ethical branding and corporate reputation. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 10(4), 341–350.

Feldwick, P. (1996). Do we really need ‘brand equity’? Journal of Brand Management, 4(1), 9–28.

Fombrun, C. J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 343–373.

Frazier, G. L., Maltz, E., Antia, K. D., & Rindfleisch, A. (2009). Distributor sharing of strategic information with suppliers. Journal of Marketing, 73(4), 31–43.

Fullerton, G. (2005). How commitment both enables and undermines marketing relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 39(11/12), 1372–1388.

García de los Salmones, M., Herrero Crespo, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2005). Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(4), 369–385.

Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1992). Monte Carlo evaluations of goodness of fit indices for structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 132–160.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798.

Grönroos, C. (2006). Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 317–333.

Gruen, T., Summers, J., & Acito, F. (2000). Relationship marketing activities, commitment and membership behaviors in professional associations. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 34–49.

Gundlach, G. T., Achrol, R. S., & Mentzer, J. T. (1995). The structure of commitment in exchange. The Journal of Marketing, 59(1), 78–92.

Gustafsson, C. (2005). Trust as an instance of asymmetrical reciprocity: An ethics perspective on corporate brand management. Business Ethics: A European Review, 14(2), 142–150.

Harris, F., & De Chernatony, L. (2001). Corporate branding and corporate brand performance. European Journal of Marketing, 35(3/4), 441–456.

Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2002). The dynamics of organizational identity. Human Relations, 55(8), 989–1018.

He, H., & Li, Y. (2010). Key service drivers for high-tech service brand equity: The mediating role of overall service quality and perceived value. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(1–2), 77–99.

He, H., & Li, Y. (2011). CSR and service brand: The mediating effect of brand identification and moderating effect of service quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(4), 673–688.

Hightower, R., Brady, M. K., & Baker, T. L. (2002). Investigating the role of the physical environment in hedonic service consumption: An exploratory study of sporting events. Journal of Business Research, 55(9), 697–707.

Holjevac, I. A. (2008). Business ethics in tourism—As a dimension of TQM. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 19(10), 1029–1041.

Hooley, G. J., Greenley, G. E., Cadogan, J. W., & Fahy, J. (2005). The performance impact of marketing resources. Journal of Business Research, 58(1), 18–27.

Hsiao, C. H., Shen, G. C., & Chao, P. J. (2015). How does brand misconduct affect the brand–customer relationship? Journal of Business Research, 68(4), 862–866.

Hsu, K. T. (2012). The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: Evidence from the life insurance industry in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(2), 189–201.

Hur, W. M., Kim, H., & Woo, J. (2014). How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: Mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(1), 75–86.

Hutchinson, D., Singh, J., Svensson, G., & Mysen, T. (2013). Towards a model of conscientious corporate brands: A Canadian study. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 28(8), 687–695.

Iglesias, O., Ind, N., & Alfaro, M. (2013). The organic view of the brand: A brand value co-creation model. Journal of Brand Management, 20(8), 670–688.

Iglesias, O., Singh, J. J., & Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2011). The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. Journal of Brand Management, 18(8), 570–582.

Ind, N. (1997). The corporate brand. Oxford: Macmillan.

Jacoby, J., Chestnut, R. W., & Silberman, W. (1977). Consumer use and comprehension of nutrition information. Journal of Consumer Research, 4(2), 119–128.

Jahanzeb, S., Fatima, T., & Mohsin Butt, M. (2013). How service quality influences brand equity: The dual mediating role of perceived value and corporate credibility. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 31(2), 126–141.

Keller, K. L. (2003). Brand synthesis: The multidimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(4), 595–600.

Kim, W. G., & Kim, H. B. (2004). Measuring customer-based restaurant brand equity. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 45(2), 115–131.

Kimpakorn, N., & Tocquer, G. (2010). Service brand equity and employee brand commitment. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(5), 378–388.

Knox, S., & Bickerton, D. (2003). The six conventions of corporate branding. European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 998–1016.

Lacey, R. E., & Kennett-Hensel, P. A. (2010). Longitudinal effects of corporate social responsibility on customer relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(4), 581–597.

Lai, C. S., Chiu, C. J., Yang, C. F., & Pai, D. C. (2010). The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 457–469.

Lassar, W., Mittal, B., & Sharma, A. (1995). Measuring customer-based brand equity. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 11–19.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braig, B. M. (2004). The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 16–32.

Lii, Y. S., & Lee, M. (2012). Doing right leads to doing well: When the type of CSR and reputation interact to affect consumer evaluations of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(1), 69–81.

Lin, C. P., Chen, S. C., Chiu, C. K., & Lee, W. Y. (2011). Understanding purchase intention during product-harm crises: Moderating effects of perceived corporate ability and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(3), 455–471.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–124.

Lovelock, C. H. (1999). Developing marketing strategies for transnational service operations. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(4/5), 278–295.

Luchs, M. G., Naylor, R. W., Irwin, J. R., & Raghunathan, R. (2010). The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 18–31.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1–18.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2009). The debate over doing good: Corporate social performance, strategic marketing levers, and firm-idiosyncratic risk. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 198–213.

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Accounting for common method variance in IS research: Reanalysis of past studies using a marker-variable technique. Management Science, 52(12), 1865–1883.

Malhotra, M. K., & Sharma, S. (2008). Measurement equivalence using generalizability theory: An examination of manufacturing flexibility dimensions. Decision Science, 39(4), 643–669.

Malik, M. (2015). Value-enhancing capabilities of CSR: A brief review of contemporary literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 127, 419–438.

Marin, L., Ruiz, S., & Rubio, A. (2009). The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 65–78.

Martin, G. S., & Brown, T. J. (1990). In search of brand equity: The conceptualization and measurement of the brand impression construct. Marketing Theory and Applications, 2(1), 431–438.

Martínez, P., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2013). CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 89–99.

Mathwick, C., Wiertz, C., & De Ruyter, K. (2008). Social capital production in a virtual P3 community. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(6), 832–849.

Matthews, D. R., Son, J., & Watchravesringkan, K. (2014). An exploration of brand equity antecedents concerning brand loyalty: A cognitive, affective, and conative perspective. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 9(1), 26–39.

Maxfield, S. (2008). Reconciling corporate citizenship and competitive strategy: Insights from economic theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(2), 367–377.

Mende, M., & Bolton, R. N. (2011). Why attachment security matters how customers’ attachment styles influence their relationships with service firms and service employees. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 285–301.

Merz, M. A., He, Y., & Vargo, S. L. (2009). The evolving brand logic: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(3), 328–344.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89.

Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1982). Predation, reputation, and entry deterrence. Journal of Economic Theory, 27(2), 280–312.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Morsing, M. (2006). Corporate moral branding: Limits to aligning employees. Corporate Communications, 11(2), 97–108.

Morsing, M., & Kristensen, J. (2001). The question of coherence in corporate branding over time and across stakeholders. Journal of Communication Management, 6(1), 24–40.

Murtiasih, S., Sucherly, S., & Siringoringo, H. (2013). How word of mouth influence brand equity for automotive products in Indonesia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 81, 40–44.

Nella, A., & Christou, E. (2014). Linking service quality at the cellar door with brand equity building. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 23(7), 699–721.

Netemeyer, R. G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., et al. (2004). Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 57(2), 209–224.

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the customer. New York: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

Pappu, R., Quester, P. G., & Cooksey, R. W. (2005). Consumer-based brand equity: improving the measurement-empirical evidence. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 14(3), 143–154.

Pappu, R., Quester, P. G., & Cooksey, R. W. (2006). Consumer-based brand equity and country-of-origin relationships: Some empirical evidence. European Journal of Marketing, 40(5/6), 696–717.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. The Journal of Marketing, 49(Fall), 41–50.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple item scale for measuring customer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.

Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 1–17.

Park, C. S., & Srinivasan, V. (1994). A survey-based method for measuring and understanding brand equity and its extendibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2), 271–288.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Poolthong, Y., & Mandhachitara, R. (2009). Customer expectations of CSR, perceived service quality and brand effect in Thai retail banking. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 27(6), 408–427.

Rangaswamy, A., Burke, R., & Olive, T. A. (1993). Brand equity and the extendibility of brand names. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 10(1), 61–75.

Rego, L. L., Billett, M. T., & Morgan, N. A. (2009). Consumer-based brand equity and firm risk. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 47–60.

Rentz, J. O. (1987). Generalizability theory: A comprehensive method for assessing and improving the dependability of marketing measures. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(1), 19–28.

Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12, 762–800.

Rindell, A., Svensson, G., Mysen, T., Billström, A., & Wilén, K. (2011). Towards a conceptual foundation of ‘Conscientious Corporate Brands’. Journal of Brand Management, 18(9), 709–719.

Rindova, V. P., Williamson, I. O., Petkova, A. P., & Sever, J. M. (2005). Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1033–1049.

Roberts, P. W., & Dowling, G. R. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1077–1093.

Roper, S., & Davies, G. (2007). The corporate brand: Dealing with multiple stakeholders. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(1–2), 75–90.

Schaller, T. K., Patil, A., & Malhotra, N. K. (2015). Alternative techniques for assessing common method variance an analysis of the theory of planned behavior research. Organizational Research Methods, 18(2), 177–206.

Scheuing, E. E., & Edvardsson, B. (1994). Service integrity. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 4(4), 24–31.

Schultz, M., Antorini, Y. M., & Csaba, F. F. (2005). Corporate branding: Purpose/people/process. Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243.

Shea, L. J. (2010). Using consumer perceived ethicality as a guideline for corporate social responsibility strategy: A commentary essay. Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 263–264.

Singh, J. J., Iglesias, O., & Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2012). Does having an ethical brand matter? The influence of consumer perceived ethicality on trust, affect and loyalty. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(4), 541–549.

Srivastava, R. K., Fahey, L., & Christensen, H. K. (2001). The resource-based view and marketing: The role of market-based assets in gaining competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 27(6), 777–802.

Srivastava, R. K., McInnish, T. H., Wood, R. A., & Capraro, A. J. (1997). The value of corporate reputation: Evidence from the equity markets. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(1), 61–68.

Steenkamp, J. E. M., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(1), 78–90.

Story, J., & Hess, J. (2010). Ethical brand management: customer relationships and ethical duties. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 19(4), 240–249.

Swaen, V., & Chumpitaz, C. R. (2008). L’impact de la responsabilité sociétale de l’entreprise sur la confiance des consommateurs. Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 23(4), 7–35.

Tsao, W. C., & Tseng, Y. L. (2011). The impact of electronic-service quality on online shopping behaviour. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 22(9), 1007–1024.

Turker, D. (2009). How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(2), 189–204.

Vlachos, P. A., Tsamakos, A., Vrechopoulos, A. P., & Avramidis, P. K. (2009). Corporate social responsibility: Attributions, loyalty, and the mediating role of trust. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(2), 170–180.

Walsh, G., & Beatty, S. E. (2007). Customer-based corporate reputation of a service firm: Scale development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(1), 127–143.

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13, 477–514.

Xie, Y., Batra, R., & Peng, S. (2015). An extended model of preference formation between global and local brands: The roles of identity expressiveness, trust and affect. Journal of International Marketing, 23(1), 50–71.

Yasin, N. M., Noor, M. N., & Mohamad, O. (2012). Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity? Journal of Product and Brand Management, 16(1), 38–48.

Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lee, S. (2000). An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 195–211.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. The Journal of Marketing, 60(April), 31–46.

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). Problems and strategies in services marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 49(2), 33–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sierra, V., Iglesias, O., Markovic, S. et al. Does Ethical Image Build Equity in Corporate Services Brands? The Influence of Customer Perceived Ethicality on Affect, Perceived Quality, and Equity. J Bus Ethics 144, 661–676 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2855-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2855-2