Abstract

Despite a long history in eastern and western culture of defining leadership in terms of virtues and character, their significance for guiding leader behavior has largely been confined to the ethics literature. As such, agreement concerning the defining elements of virtuous leadership and their measurement is lacking. Drawing on both Confucian and Aristotelian concepts, we define virtuous leadership and distinguish it conceptually from several related perspectives, including virtues-based leadership in the Positive organizational behavior literature, and from ethical and value-laden (spiritual, servant, charismatic, transformational, and authentic) leadership. Then, two empirical studies are presented that develop and validate the Virtuous Leadership Questionnaire (VLQ), an 18-item behaviorally based assessment of the construct. Among other findings, we show that the VLQ accounts for variance in several outcome variables, even after self-assessed leader virtue and subordinate-rated social and personalized leader charisma are controlled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

If you lead with virtue and regulate with rules of propriety, people will develop a sense of shame and will form good character. (—Confucius, 551–479 BCE; Irwin 1999)

Though admittedly, as we have said, an excellent person is both pleasant and useful, he does not become a friend to a superior [in power and position] unless the superior is also superior in virtue. (—Aristotle, 384–322 BCE; Li 2009)

There is a long established history in both eastern and western culture of defining leadership in terms of virtues and character. As early as the sixth century BCE, in his discussion of “rulers”, the ancient Chinese thinker Confucius noted that leaders should be knowledgeable and virtuous in order to fulfill their roles well (Li 2009). In western culture, Aristotle noted that virtues are required of an “excellent” leader in both community (Dyck and Kleysen 2001) and business activities (Bragues 2006). The term “virtue” is derived from the Greek word “arête”, interpreted as “excellence” (Bunnin and Yu 2004) and expressed, in part, through conforming to morally “right” standards. The contemporary discussion of the significance of virtues in guiding leader behaviors appears mainly in the ethics literature, particularly under the umbrella of virtue ethics.

Virtue ethics, as one of the three leading moral philosophies (the others being deontology and teleology; Palanski and Vogelgesang 2011), has its roots in both the ancient Greek civilization, especially in Aristotelianism (MacIntyre 1984) and in Confucianism (Chan 2003). In general, virtue ethics is “a system of ethical thought which considers the development and nurture of moral character as the best way to affect moral behavior and a moral society” (Palanski and Yammarino 2009, p. 176). Over time, a rich systematic discussion of virtues has developed concerning the nature of virtue, how it is acquired and developed, and how it influences behavior. Nonetheless, only recently has virtues ethics begun to figure prominently in leadership research in the organizational and behavioral sciences (Flynn 2008; Juurikkala 2012; Manz et al. 2008; Neubert 2011; Riggio et al. 2010; Sosik and Cameron 2010; Sosik et al. 2012; Thun and Kelloway 2011) as part of a framework used to understand business ethics (Crossan et al. 2013; Flynn 2008; Palanski and Yammarino 2009). Unfortunately, as Hackett and Wang (2012) document, much of this scholarship is not well grounded in virtue ethics which has contributed to a lack of consensus concerning the core defining elements of virtuous leadership and their measurement.

The main goal of this research is to define and measure virtuous leadership based on virtue ethics, grounded in both Confucian and Aristotelian thinking (Hackett and Wang 2012). As it is commonly agreed that the concept of virtuousness varies somewhat by culture (Hursthourse 2007; Mele 2005), we follow Hackett and Wang (2012) to define virtuous leadership based on the commonalities between Aristotelianism and Confucianism, which dominate western and eastern societies, respectively. In doing so, we intend our work be applicable to both Western- and Eastern-based organizations. Moreover, we focus on a smaller, coherent set of virtues that are specifically pertinent to leadership and develop a reliable, valid instrument to measure them.

By role modeling virtuous behavior, leaders have the opportunity to enhance the overall ethical climate in their organizations while simultaneously enhancing overall well-being of employees. In comparison to the questionable efficacy of ethics codes (cf. Kish-Gephart et al. 2010), efforts to promote virtuous leadership appear quite promising. Given our view that virtue is character-based, the importance of who is selected for leadership positions is clear. Specifically, the Virtuous Leadership Questionnaire (VLQ) we develop and evaluate here could be incorporated into career development programs to help build a virtues-based culture (e.g., Southwest Airlines; Cameron 2011). The VLQ could also be administered to business school students to raise awareness of the importance of leader character and of character in general (Pearce 2007). Finally, as we will detail, our findings do not suggest a trade-off between virtuous leadership and leader effectiveness; that is, the practice of virtuous leadership should not be at odds with the pursuit of the traditional business values of profits and efficiency. Rather, there is reason to expect that virtuous leadership will facilitate the economic livelihood and longer term sustainability of the organization. Accordingly, by exemplifying virtues, leaders are “doing well by doing good.”

The overall structure of the paper is as follows. We begin by distinguishing virtuous leadership conceptually from existing perspectives with moral underpinnings, including virtues-based leadership as it is treated in the positive organizational behavior (POB) literature, as well as from ethical and value-laden (e.g., spiritual, servant, charismatic, transformational, and authentic) leadership. From an empirical perspective, two studies are then presented in which we develop and validate the VLQ, an 18-item behaviorally based assessment of the construct. Finally, the contributions and limitations of the studies are noted, along with possibilities for future research.

Virtuous Leadership: Concept, Theory, and Distinctions

Along with a resurgence of virtue ethics as a framework for business ethics (Crossan et al. 2013; Flynn 2008; Palanski and Yammarino 2007), there has been increasing research interest in virtues-based leadership. In this section, we critically review the literature concerning virtue and leadership culminating in a conceptualization of virtuous leadership that is grounded in both Aristotelian and Confucian thought. As detailed below, although our perspective reflects many of the character attributes portrayed as desirable in the leadership literature, it is nonetheless distinct from existing perspectives.

Assessments of Virtuous Leadership in Prior Research

Relatively, few scholars have defined virtuous leadership in a manner that is grounded in virtue ethics. For Pearce et al. (2006, p. 63) virtuous leadership is “distinguishing right from wrong in one’s leadership role, taking steps to ensure justice and honesty, influencing and enabling others to pursue righteous and moral goals for themselves and their organizations, and helping others to connect to a higher purpose.” For Kilburg (2012, p. 85) virtuous leadership is exemplified by leaders “who discern, decide, and enact the right things to do, and do them in the right ways, in the right time frames for the right reasons.” While these definitions capture certain aspects considered important by virtues ethicists (e.g., justice, honesty, moral behavior, “doing the right thing”), they are incomplete because they lack a philosophical foundation from the virtues ethics literature.

Cameron (2011, p. 451) suggested that “virtuous leadership focuses on the highest potentiality of human systems and is oriented toward being and doing good”; however, Cameron later equated this view with responsible leadership. Similarly, virtuous leadership has been considered conceptually synonymous with (or highly similar to) moral (Gao et al. 2011), ethical (Cameron et al. 2004; Riggio et al. 2010), servant and spiritual (Freeman 2011; Sendjaya et al. 2008), inclusive (Rayner 2009), transformative (Caldwell et al. 2012), transformational (Brown 2011), and paternalistic leadership (Wu and Tsai 2012). Still others have treated virtuous leadership as a component of ethical (Walker and Sackney 2007), servant (Lanctot and Irving 2010), charismatic (Juurikkala 2012), transformational/authentic (Hannah et al. 2005), and responsible (Pless and Maak 2011) leadership. Importantly, none of these conceptualizations are grounded in the virtues ethics literature.

In finding fifty-nine often ill-defined virtues/character traits and personal dispositions referenced across seven leadership perspectives, Hackett and Wang (2012) argued that a parsimonious, coherent, integrated theoretical framework was sorely needed. Based on a comparative analysis of the overlap between the Confucian and Aristotelian traditions in the virtues ethics literature, they proposed that six cardinal virtues (those that together determine all the other virtues; i.e., courage, temperance, justice, prudence, humanity, and truthfulness) could usefully guide research, much as the “big five” model has been used in the study of personality (e.g., Barrick and Mount 1990).

With respect to the measures of virtuous leadership, all but two are poorly aligned with the Hackett and Wang’s (2012) recommendations. For example, in developing a self-assessment of virtues, the Virtue Scale (VS), Cawley et al. (2000) followed the lexical tradition and searched the New Merriam-Webster Dictionary (1989) where 140 virtue terms were identified and used to develop items. Using a “formative approach” (cf. Sendjaya et al. 2008) in which the virtues were derived empirically rather than purely from theory, factor analysis of these items revealed four virtues: empathy, order, resourcefulness, and serenity (cf. Cawley et al. 2000). Perhaps not surprisingly, virtue ethicists question the meaningfulness of empirically driven approaches (Fowers 2008). Other self-instruments such as the Virtuous Leadership Scale (VLS; Sarros et al. 2006) focus on a single virtue only, as do many of the options for obtaining subordinate-based evaluations; for example, moral courage (Hannah and Avolio 2010), professional moral courage (Palanski and Vogelgesang 2011), behavioral integrity (Prottas 2013) or benevolence (Wu and Tsai 2012). Finally, the 34-item Virtue Ethical Character Scale (VECS; cf. Chun 2005) targets integrity, empathy, warmth, courage, conscientiousness, and zeal, though at the organizational level.

Moving now to the two measurement efforts that are more in line with the recommendations of Hackett and Wang (2012), Riggio et al. (2010) explicitly applied the virtues ethics literature to develop the subordinate-rated 19-item Leadership Virtues Questionnaire (LVQ). Specially, for Riggio et al. (2010), a virtuous leader is one whose characteristics and actions are consistent with four virtues (prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice). As will be seen, our work builds on theirs by, for example, incorporating both Aristotelian and Confucian virtues (see Hackett and Wang 2012) such as humanity and truthfulness. Further, in emphasizing the importance of leader behaviors reflective of virtuousness, we aim to minimize the inferential and/or judgmental nature of some of the LVQ content (e.g., “Does as he/she ought to in a given situation”; “May have difficulty standing up for his/her beliefs among friends who do not share the same views”; “Ignores his/her ‘inner voice’ when deciding how to proceed”), which may have contributed to the finding that the LVQ reflects a general factor only, as opposed to each of the four intended virtues (Riggio et al. 2010).

Finally, the Character Strengths in Leadership Scale (CSLS) developed by Thun and Kelloway (2011) is also somewhat consistent with Hackett and Wang’s (2012) approach. Although the subordinate-rated 14-item CSLS was initially based on Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) 24 character strengths rather than the virtues ethics literature, it does assess the two Aristotelian virtues of humanity and temperance. Further, in line with our orientation, most of the CSLS content is behavioral in nature (see Thun and Kelloway 2011, Table 1, p. 275).

To sum up, while there have been some efforts to distinguish virtues from personality (Cawley et al. 2000) and relate virtue ethics to the behavior of business people in general (e.g., Shanahan and Hyman 2003), most of the existing work concerning virtuous leadership lacks a strong philosophical grounding in virtue ethics and/or a psychometrically sound, multidimensional tool to measure the construct. Like Hackett and Wang (2012), we capitalize on the virtues ethics literature to develop a philosophically grounded conceptualization of virtuous leadership. Our interest is in a broader set of virtues as described below.

Six Cardinal Virtues Associated with Virtuous Leadership

Since the original Aristotelian texts (e.g., The Nicomachean Ethics) are Greek and the Confucian texts (e.g., The Analects, and The Mencius) are written in ancient Chinese, it is inevitable that the various English editions of these works contain inaccuracies and inconsistencies. Accordingly, we selected “The Nicomachean Ethics” translated by Irwin (1999), “The Analects” by Huang (1997), and “The Mencius” by Bobson (1963) for the definitions of Aristotelian and Confucian virtues (see Table 1). Nonetheless, it is important to note that both Aristotle and Confucius lived in a world quite different from ours. Thus, each leader virtue is defined and identified using behavioral indicators from the contemporary ethics and leadership literature.

The Aristotelian virtue of courage overlaps with the Confucian virtue of “Yong” (courage). In the contemporary literature, Messick (2006, p. 106) defined courage as “the conviction to do what one believes is the right thing despite the risk of unpleasant consequences”, while Yearley (2003, p. 144) defined “Yong” (courage) as a personal quality “that allows people to overcome or control fear, especially those fears that impede people from doing what they wish to do or think they should do.” Thus, courage is a disposition; a character trait enabling leaders to do without fear what they believe is “right.” Contextually, leaders exemplify courage when they take actions that may not be popular and/or may put them at personal risk.

The Aristotelian virtue of temperance overlaps with the Confucian virtue “Zhongyong” (moderation). In the Nicomachean Ethics (Irwin 1999), Aristotle stated: “In pleasures and pains—though not in all types, and in pains less than in pleasures—the mean is temperance and the excess intemperance” (1107b5-10); further, “if something is pleasant and conducive to health or fitness, he will desire this moderately and in the right way; and he will desire in the same way anything else that is pleasant, if it is no obstacle to health and fitness” (1119a10-20). “Hence the temperate person’s appetitive part must agree with reason; for both [his appetitive part and his reason] aim at the fine, and the temperate person’s appetites are for the right things, in the right ways, at the right times, which is just what reason also prescribes” (1119b15-20). While it could be argued that Aristotelian temperance concerns the bodily desires associated with self-health, fitness, and appetite only, we view it as relating to the control of emotional reactions to pleasure and pain generally, including the avoidance of personal tendencies toward the extreme, which, along with and guarding against objects of pleasure, overlaps with the Confucian virtue of “Zhongyong”, moderation (Kok and Chan 2008). In the contemporary literature, Sison (2003) defined temperance as a positive character trait reflecting control of the desire for instant gratification. Yearley (2003, p. 150) defined Zhongyong (moderation) as a personal quality “that enables people to control emotional reactions and, in some fashion, to modulate their normal desires for things that are attractive either for biological reasons (e.g., good) or cultural reasons (e.g., fame).” For us, temperance is a disposition; a character trait that helps leaders control their emotional reactions and desires for self-gratification. Contemporary scholars have suggested that leaders could demonstrate temperance in several ways, including: careful budgeting of financial, physical, and human resources to make the organization continually viable (Walton 1988); avoiding and resisting temptation to overindulge in hedonistic behaviors (Kanungo and Mendonca 1996); avoiding the pursuit of immediate short-term gains in sacrifice of long-term goals; and restricting one’s instincts and tendencies within the limits of what is honorable (Sison 2003). We thus contend that, contextually, leaders require temperance when opportunities for high profits come at high risk, and in the face of the urge to overindulge in hedonistic behaviors (e.g., the overuse of financial derivatives in 2008).

The Aristotelian virtue of justice overlaps with the Confucian virtue “Yi.” In the contemporary literature, MacIntyre (1984) viewed justice as a disposition that underlies the respectful treatment of others, while Sison (2003, p. 160) viewed it as a positive character trait that disposes a person to “respect the rights of others and to establish harmony in human relationships such that equity and the common good are promoted.” Yi (righteousness) is a form of justice in the Western tradition (Yearley 2003). For us, justice is a disposition; a character trait motivating respectful recognition and protection of the rights of others to be treated fairly, in accordance with uniform and objective standards. Contextually, justice is required of a leader in the face of conflicts of interest; when duties are assigned among subordinates (Kohlberg 1976); and/or when valued resources (e.g., money, property, offices, power, and status) are allocated (Bragues 2006).

The Aristotelian virtue of prudence overlaps with the Confucian virtue “Zhi.” In the contemporary literature, Sison (2003, p. 161) defined prudence as a positive character trait that “disposes practical reason to discern the true good in every circumstance and to choose the right means of achieving it.” The Confucian virtue Zhi (wisdom) is an intention or inclination of the mind, which can help guide the mind in the right direction (Gardner 2003). We define prudence as a disposition: a character trait enabling leaders to make “right” judgments and choose the “right” means to achieve the “right” goals. Contextually, leaders demonstrate prudence when opportunities are fully examined and evaluated in light of the likely consequences (Walton 1988) and when decisions are made carefully (Kanungo and Mendonca 1996; Sison 2003).

Humanity represents the Confucian virtue Ren (humanity) and the Aristotelian virtue friendliness. In the contemporary literature, Chan (2003) defined Ren (humanity) as a disposition to care for and sympathize with others, and to show concern for relationships with others. The Aristotelian virtue friendliness is defined as a good-natured disposition, motivating people to adjust their manners as appropriate to different people (e.g., a friend, an acquaintance, or a conversational partner); and desiring to please others and protect them from pain (Bragues 2006). We define humanity as a disposition; a character trait underlying leaders’ love, care, and respect of others. Contextually, leaders demonstrate humanity (friendliness) as required when interacting with others, such as customers, supervisors, peers, and subordinates (Bragues 2006) and community members.

The Aristotelian virtue truthfulness aligns with the Confucian virtue “Xin” (truthfulness). In the contemporary literature, Lau (1979) defined Xin (truthfulness) as the personal character that underlies “promise-keeping” and reliability. We define truthfulness as a disposition; a character trait reflected in leaders’ telling the truth and keeping promises. Contextually, leaders practice truthfulness in communicating honestly to others (e.g., no deception or falsehoods; Solomon 1999), honoring promises (Palanski and Yammarino 2007), and taking personal responsibility (Taylor 2006).

A Definition of Virtuous Leadership Grounded in Virtues Ethics

Like Hackett and Wang (2012), we define virtuous leadership as a leader–follower relationship wherein a leader’s situational appropriate expression of virtues triggers follower perceptions of leader virtuousness, worthy of emulation. In elaborating on the definition presented in Riggio et al. (2010), we consider not only the make-up or content of virtuous leadership, but also the contexts in which it operates, as well as a consideration of its associated underlying processes (Kanungo 1998). Accordingly, as detailed below, our view of virtuous leadership includes three essential elements: leader virtues, leader virtuous behaviors, and context. Moreover, perceptually-driven attributions and modeling are seen as the two fundamental processes by which leader virtue influences followers.

Virtues Exemplified by Virtuous Leaders

The six cardinal virtues we highlight have several characteristics in common such that they are all (1) dispositions encompassing “good” character traits that are philosophically distinct from actions and from the other personal traits, such as feelings, skills, capabilities, competencies, and values; (2) cross-culturally universal in the sense that they all reflect the commonalities between Aristotelian and Confucian cardinal virtues, which are embedded into Western and Eastern traditions, respectively; (3) interrelated and often demonstrated simultaneously where required; and, (4) seen as contributors to both ethical and effective leadership. We expect that these virtues will be expressed by leaders to varying degrees by voluntary actions (behaviors) in context relevant situations.

Behaviors of Virtuous Leaders

Leaders are thought to acquire virtues through learning and continuous practice, such that virtuous behavior becomes habitual (Bragues 2006). Of course, habits can be lost due to a lack of practice (Verplanken et al. 2005), which implies that once leaders acquire a virtue, it is sustained only through continuous practice; virtue is lost in the absence of practice.

Both Hart (2001) and Whetstone (2001) suggested that virtuous action is voluntary in three senses. Firstly, it is intentional; the actor is aware of the pertinent facts of a situation and the practical wisdom needed for this action. Secondly, the underlying motive of virtuous action is intrinsic; it is neither for personal advantage nor a result of external rules, controls, or compulsion. Thirdly, virtuous action is expressed consistently over time. In all, a virtuous leader is expected to display a virtue intentionally, consistently, and for intrinsic reasons.

Contexts in Which Virtuous Leadership is Embedded

As reflected in the definitions of the virtues provided earlier, we argue that the expression of virtue is somewhat context dependent, though this is a matter of ongoing debate. For example, both Alzóla (2012) and MacIntyre (1984) argued that holding a virtue entails expressing it across a broad range of situations, while Juurikkala (2012) and Whetstone (2005) suggested that virtuous behavior is at least partially context dependent. Our perspective is in line with their view. Using courage as an example, it is rarely if ever required in situations that do not involve fear (Hackett and Wang 2012). Further, we contend that although a virtuous leader is likely to act consistently across situations, the meaning attached to a behavior by an observer may vary, introducing an additional element of contextual dependence. Subordinate inferences and judgments concerning leader virtuousness will also depend on follower knowledge and beliefs concerning virtuousness.

Underlying Processes: Perceptual and Attributional Underpinnings to Virtuous Leadership

The overall leadership process can be summarized by “the leader’s dispositional characteristics and behaviors, follower perceptions and attributions of the leader, and the context in which the influencing process occurs” (Day and Antonakis 2012, p. 5). Hence, leaders influence followers through subordinate perceptions and attributions. For example, attribution theory (Kelley 1972) holds that people make judgments concerning the cause of a person’s behavior based on perceived behavioral consistency (the extent to which the person behaves in the same way in response to similar situations across time); distinctiveness (the extent to which the person behaves this way in this one situation, but not in different, though similar, situations); and consensus (the extent to which others behave this way in the same situation). Observers are most likely to attribute a behavior to internal (i.e., the person) as opposed to external (i.e., the situation) causes when consistency is high, but both distinctiveness and consensus are low. Since we define leader virtue as having a situational component, the attribution of virtue to a leader is most likely when followers observe (1) the leader expressing the virtue in repeated occurrences of the same situation (high consistency), (2) the leader expressing the virtue in similar (though different) situations (low distinctiveness), and (3) other leaders who do not behave virtuously in the same situation (low consensus). This is in line with the view of virtues ethicists who argue that people (leaders) do not possess a virtue by degree (MacIntyre 1984). That is, a leader who possesses a virtue is thought to be disposed to demonstrate it consistently, although followers may perceive virtuousness only to some extent given their restricted opportunities to observe and the nature of the attribution process. Thus, some leaders might be perceived by followers as more virtuous than others. Moreover, followers may perceive their leader as virtuous based on attributions concerning different subsets of virtues. Perceptions of virtuous leadership should be higher among leaders exemplifying a wider array of virtues.

Modeling of Virtuous Leadership

Consistent with social learning theory (SLT) in which role models are seen as an indispensable source of learning (Bandura 1976), leaders can potentially be a positive influence for followers by behaving in a virtuous manner that can be observed (Atkinson and Butler 2012). Importantly, subordinates are especially likely to look to their leaders as role models owing to their status and power (Brown et al. 2005). Further, since trust and respect can be acquired by practicing the virtues (Arjoon 2000), a virtuous leader may gain influence over their followers, for example, through referent power, which is grounded in respect and trust (Yukl 2010). Also consistent with SLT (Bandura 1976), virtuous leaders can be a source of indirect influence as a result of the intrinsic rewards followers are likely to experience by engaging in behavior learned from watching the leader (Yukl 2010). These rewards are grounded in internalization, in which a subordinate accepts influence because the behaviors modeled by the leader are (or gradually become) congruent with the values and belief system of the follower (Kelman 1958). Further, it is likely that this value congruence will be strengthened by others in the workplace since virtuous behavior is widely accepted in both Western and Eastern traditions as “good” for everyone (MacIntyre 1984) and reflective of desirable personal qualities (Sison 2003). Specifically, the social desirability of virtuous behavior is likely to become apparent to followers through informal everyday experience and formal moral education. Moreover, most people have strong intuitions about the moral sense of virtues at an early age (Kreps and Monin 2011). In any case, Neubert et al. (2009) argue that the follower internalization process amplifies the impact of leader virtuous behavior, while Gao et al. (2011) characterize the outcome as follower moral identification with the leader.

In summary, the modeling process associated with virtuous leadership can be described as a virtuous leader models virtuous behavior; followers observe and imitate it as it becomes perceived as increasingly congruent with their own values; followers continuously practice these behaviors because of the associated intrinsic rewards; and the behaviors become habitual through practice within a social context that is generally supportive.

Distinctions Between Virtuous Leadership and Virtues-Based Leadership in the POB Literature

As noted earlier, virtues have been invoked in the POB literature as foundational constructs in discussions of virtues-based/character-based leadership (Cameron et al. 2004), and in leadership generally (Bright et al. 2011; Sosik and Cameron 2010). Relative to our conceptualization, the focus of these perspectives is mainly on leaders’ roles in fostering unit-level virtuousness, expressed in “individuals’ actions, collective activities, cultural attributes, or processes that enable dissemination and perpetuation of virtuousness in an organization” (Cameron et al. 2004, p. 768). For POB scholars, leaders foster and enable virtuous practices and champion the creation of a shared distinctive culture of virtuousness (Cameron 2011; Manz et al. 2008) where virtue is variously treated as a multi-level construct crossing individual, group, and organization levels (Atkinson and Butler 2012; Barclay et al. 2012); a broadband, socially desirable attribute valued across time and cultures (Shryack et al. 2010); universal, “perhaps grounded in biology through an evolutionary process that selected for these aspects of excellence as a means of solving the important tasks necessary for survival of the species” (Peterson and Seligman 2004, p. 13); or as deep rooted values (Manz et al. 2008). These views have been criticized as reflecting “a superficial, colloquial understanding of virtue, serving as a reference point in defining what constitutes positive deviance” (Bright et al. 2011, p. 2), whereas our view is solidly grounded in Confucian and Aristotelian perspectives where leader virtues are seen as personal character traits that help form the “good character” (Hartman 1998). Relative to these other psychological/biological perspectives, our focus is on virtues as individual-level dispositions that are learned, which provide the substantive moral foundation for one’s actions, as well as a tendency to act or react in characteristic ways in certain situations.

The underlying processes we invoke concerning virtues-based leadership—perceptual-driven attributions modeling—also differ from the POB literature. For example, Sosik and Cameron (2010) proposed a framework around authentic transformational leadership, building on Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) model of character strengths and virtues. In their view, “leaders first create an ascetic self-construal that derives from character strengths and virtues and then project this self-image through idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration behavior” (Sosik and Cameron 2010, p. 251). Two processes—amplification and buffering—have been proposed in POB to account for how leader virtues (e.g., courage, hope, honesty, and forgiveness) influence others. With amplification, observing virtuous leader behavior is thought to enhance the positive emotions of peers and subordinates, encouraging prosocial behavior, building social capital, and offering protection (i.e., buffering) against stress and dysfunctional behavior (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). In the aggregate, “organizational virtuousness” is thought to be enhanced via self-reinforcing positive spirals (amplifying) that protect against traumas such as downsizing (Cameron et al. 2004).

Distinctions Between Virtuous Leadership and Ethical Leadership

Virtues have been noted for their significance in guiding ethical decision-making (Crossan et al. 2013). With regard to ethical leadership per se, Kanungo and Mendonca (1998) asserted that ethical leaders endeavor to cultivate virtues and abstain from vices, while Neubert et al. (2009) described ethical leaders as agents of virtue that help build employee perceptions of a virtuous, ethical organization. Indeed, while ethical leadership and virtue ethics both concern character and integrity, ethical leadership also has clear ties to the two other leading schools of moral philosophy (Resick et al. 2006; note, we treat moral and ethical leadership as equivalent or interchangeable, in line with Brown and Treviño 2006; Ciulla 2004; Kanungo and Mendonca 1998; and Yukl 2010). Indeed, our review of the representative definitions of ethical leadership suggests that they are based less on virtues ethics and more on deontology and teleology. For example, in both Rost (1991) and Brown et al. (2005), ethical leadership has a deontological focus on obligations to act (i.e., emphasizing leaders ought to freely agree with followers on the intended changes and to demonstrate normatively appropriate conduct), as well as a teleological focus on the consequences of actions (i.e., increasing followers’ autonomy and value without sacrificing leaders’ integrity, and promoting the normatively appropriate conduct in followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making). Fairholm and Fairholm’s (2009) view of ethical leadership is also best characterized as deontological in focus, in that it is a model of conduct that sets up the “right” set of rules.

That ethical leadership has ties to all three major moral philosophies might initially be seen as positive for the comprehensiveness of the concept, but it creates a difficulty in that each of the philosophical schools is based on a set of distinct assumptions that are often somewhat incompatible. For example, deontology assumes that rationality and reason are valued over pleasure, whereas teleology assumes humans are pleasure-seeking, and normally consider the consequences of their decisions before acting to maximize pleasure and minimize pain (Knights and O’Leary 2006). Importantly, virtue ethics, in contrast to deontology and teleology, assumes that virtues are embodied within character, predisposing people to do the “right” things (Resick et al. 2006); virtuous behaviors are chosen because they are virtuous (Flynn 2008). Thus, virtues ethics emphasizes the role of leader character, while deontology underscores duties, principles, norms, formal structures, in addition to rules and regulations, and teleology emphasizes consequences, such as the rewards and/or punishments expected, and the probability of goal attainment (Atkinson and Butler 2012; Shanahan and Hyman 2003). Not surprisingly, these differences in the fundamental assumptions oftentimes produce incompatible recommendations for action (Dawson 2005). Thus, our purposeful grounding of virtuous leadership solely in virtue ethics is intended to avoid much of the conflict among the philosophical underpinnings.

Finally, our view of virtuous leadership differs from ethical leadership in terms of the nature of the leader–follower interactions that are deemed to be of central interest. For example, Rhode (2006) suggested that ethical leaders explicitly urge followers to adopt ethical values important to accomplishing a moral purpose, while for Brown and Treviño (2006) the influence of ethical leadership comes by communicating ethical standards and expectations, intentionally role modeling normatively appropriate conduct, and through the explicit use of rewards and punishments. Both these views differ substantially from our perspective that a virtuous leader engages in virtuous leadership because it is virtuous, and that by observing and imitating, followers adopt virtuous behaviors for intrinsic reasons on their own as they become seen as virtuous and socially desirable.

Distinctions Between Virtuous Leadership and Values-Laden Leadership Concepts

As noted earlier, virtues have been tied to value-laden leadership concepts (Sendjaya et al. 2008), such as spiritual, servant, charismatic, transformational, and authentic leadership (cf. Hackett and Wang 2012). These conceptualizations are predicated on shared values advocated and exemplified by the leader (Fry 2003; Rhode 2006). Though there is the potential to inappropriately confuse virtues with values (Crossan et al. 2013; Hannah et al. 2005), there are important differences. For example, values can be held but not practiced but virtues are sustained only through practice (Ciulla 2004). Further, values “tend to define cultures or characteristics of roles within an organization or social construct, while virtues transcend cultures and other socially-embedded constructs” (Lanctot and Irving 2010, p. 11). Also, as explained earlier, our concept of virtuous leadership is purely character-based, emphasizing “good” leader traits.

Our character-based conceptualization also steers clear of the debates on the degree to which values-laden leadership is ethical. For example, spiritual leadership may lead to the abuse of power (Johnson 2007) and follower manipulation (Reave 2005), while servant leaders may inappropriately provide followers whatever they need to achieve goals (Winston and Patterson 2006). Finally, authentic leadership may not encompass moral resources (Pless and Maak 2011) and leave leaders unaware of their flaws (Diddams and Chang 2012), while the potential dark sides of charismatic and transformational leadership are well known (cf. Conger and Kanungo 1998). On the other hand, in our conceptualization, leaders engage in virtuous leadership because it is inherently ethical. Importantly, the behavior of virtuous leaders will likely differ from value-laden leaders who, for example, are primarily focused on meeting follower needs and/or who are concerned with elevating follower motivation (Bass and Riggio 2006; Fry and Slocum 2008; Greenleaf 2002). Virtuous leaders guide their followers by role modeling of virtues intentionally, consistently, and for intrinsic reasons; their primary focus is on the cultivation of character as opposed to serving or motivating followers.

Value-laden and virtuous leadership also differ fundamentally in their underlying constructs. For example, spiritual leadership is based on vision, hope/faith, spiritual well-being, and values of altruistic love (Fry and Slocum 2008), as well as spiritual motivation, qualities, and practices (Reave 2005), while the servant concept focuses on helping others to become healthier, wiser, freer, and more autonomous (Greenleaf 2002). Though there is considerable debate concerning the exact nature of the construct (Yukl 2010), charisma (Conger and Kanungo 1998) and self-concept (Shamir et al. 1993) are the foundations for charismatic leadership. Transformational leadership is seen as encompassing such root constructs as vision, end-values (liberty, justice, and equality), follower motives, and four leader behaviors—idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Bass and Riggio 2006)—whereas the root constructs of authentic leadership include leader positive psychological capital and positive moral perspective, self-awareness, and self-regulation; and organizational context characterized as turbulence, uncertainty, and/or challenge (Avolio and Gardner 2005; Walumbwa et al. 2008). In all, there is substantial construct variation within the realm of value-laden leadership. With the exception of Riggio et al. (2010) and Thun and Kelloway (2011), very little has been done to target the set of cardinal virtues of interest to us.

Method

Item Generation

We now describe the development of a behaviorally based scale intended to capture the six cardinal virtues (courage, temperance, justice, prudence, humanity, and truthfulness) that encompass our concept of virtuous leadership.

To generate behaviorally based items reflecting virtuous leadership, deductive and inductive approaches (DeVellis 2003; Hinkin 1998) were used as part of a three-phase process.

In Phase I, a comparative analysis of the Aristotelian and Confucian equivalents was conducted. A standard definition of virtuous leadership from On-line Oxford English Dictionary (Simpson 2009) was compared to views from the Aristotelian and Confucian traditions. At least 14 behavioral examples for each of the six cardinal virtues were found in the leadership and ethics literatures. A sample of them with our definition of each virtue is presented in Table 1. In total, we found 89 leadership behaviors that align well with one or another of the six cardinal virtues (available from the authors).

A focus group was formed consisting of five doctoral students from different business disciplines at a Canadian university. They all had various countries of origin, full-time non-academic work experience, and background in writing items for scale development. The group was asked to use their observations of leaders to provide six behaviors expressive of each of our targeted virtues. After removing duplicates, 78 of the behaviors were similar to the 89 found in our literature review of the leadership and ethics literatures. These were retained for translation into behaviorally based scale items which, consistent with our definitions, incorporated context appropriate to the expression of the virtue. For example, with regard to courage, “Does what is considered right to do, though risking negative career consequences”; and “Rejects directives of an unethical/immoral authority, despite risking discipline.”

In Phase II, a second focus group of five doctoral students (with background similar to those in Phase I) were given the definitions of the leadership virtues and the 78 behavioral items from Phase I and asked to independently assign them back to a given virtue. Fifty-four items were correctly reassigned at least 80 % of the time (a common threshold for item retention; cf. Sendjaya et al. 2008; Walumbwa et al. 2008) and therefore were retained for further analysis.

In Phase III, four business faculty members each independently reviewed and amended the 54 behavioral items (10 items each for courage, humanity, and truthfulness; eight each for temperance, justice, and prudence) for clarity and fluency.

The 54-item survey, using a 5-point Likert response format (1 = Not at all; 5 = frequently), was then distributed to 432 first-year undergraduates in a human resources management class. They were asked to complete it on a voluntary, anonymous basis, using a leader they had observed during paid or non-paid work as a referent. Twenty-five students declined to participate and 59 responses with incomplete data were dropped, resulting in a final sample of 348 (an 81 % response rate). An exploratory factor analyses (EFA) with an oblique rotation (i.e., direct oblimin; Kline 2010) was conducted using Amos 19.0 to examine the item loadings and item total-scale correlations. Many of the items in the initial set, including all 10 intended to reflect truthfulness, did not load cleanly on their intended factor and were therefore dropped from subsequent analysis. The lack of distinctiveness involving the truthfulness items is consistent with other empirical studies (e.g., Palanski and Yammarino 2009; Peterson and Seligman 2004), perhaps reflecting the Aristotelian view that truthfulness is an ordinary (as opposed to a cardinal) moral virtue (Irwin 1999). In any case, Study 1 focused on the remaining 29 items.

Study 1

Sample and Procedure

A questionnaire consisting of the reduced 29-item set was distributed using a web survey firm (cf. FluidSurveys 2013) to 503 MBA students at a North American university. Participants were asked to use a leader from their workplace experience as a referent when completing the scale and were entered into a random draw for one of five $100 bookstore gift certificates. The response rate was 38 % (102 males and 92 females).

Results

The 29-item VLQ was evaluated using maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to estimate a model consisting of five correlated factors. Based on commonly used indices of fit in scale development (cf. Worthington and Whittaker 2006), our initially hypothesized model was a poor fit. For example, both the CFI (.89) and the NFI (.79) were below the desired .90 benchmark. Accordingly, 11 items were removed based on an examination of the factor loadings and the modification indices. The resulting 18-item five-factor model was a good fit. For example, the χ 2/df, (164.49/125) ratio was well less than 3.00, both the CFI (.98) and NFI (.91) exceeded .90, while the RMSEA of .04 was less than .05, as desired (Meyers et al. 2006; Worthington and Whittaker 2006).

Table 2 shows the 18-items (four each for courage, temperance, and prudence; and three each for justice and humanity) and the factor loadings associated with them, which were all significant.

Study 2

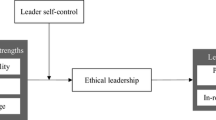

The aim of Study 2 was to further examine the fit of the 18-item VLQ, and to assess the convergent (Hypotheses 1–3), discriminant (Hypothesis 4), criterion-related (Hypotheses 5–9), and incremental validity (Hypothesis 10) of the measure.

The Convergent and Discriminant Validity of the VLQ

The overall rationale for the choice of variables regarding the assessment of convergent validity was to select pairs of measures reflecting (1) a positive and negative character trait; and (2) an ethical and unethical leadership style. Specifically, the relationship of the VLQ was examined both in relation to an overall self-assessment of leader virtue using the VLS (Sarros et al. 2006), and to Machiavellianism (i.e., positive versus negative character, respectively); and then to socialized and personalized charismatic leadership (i.e., ethical versus unethical leadership, respectively). The first three hypotheses, each associated with these pairings, are presented below.

The 7-item VLS (one item each for humility, courage, integrity, compassion, humor, passion, and wisdom) was used (cf. Sarros et al. 2006). As both the VLS and VLQ are intended measures of positive leader character, they should be positively related.

Hypothesis 1

Followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ are related positively to their leader’s self-assessment of virtues as measured by the VLS.

Machiavellianism, a negative character trait (Walter and Bruch 2009) reflecting a highly power-oriented personal disposition to use manipulation and deceit to maximize self-interest, at the expense of others (House and Howell 1992), was expected to relate negatively to leader virtue.

Hypothesis 2

Followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ are related negatively to their leader’s self-assessment of Machiavellianism.

Since virtues dispose people to behave ethically (Cavanagh and Bandsuch 2002), the VLQ should associate positively with socialized charismatic leadership, an ethical form of charismatic leadership (Howell and Avolio 1992; Shamir et al. 1993). Socialized charismatic leadership (a) is based on egalitarian behavior, (b) serves primarily collective interests rather than self-interests, and (c) develops and empowers others (House and Howell 1992, p. 84). In contrast, the VLQ should relate negatively to personalized charismatic leadership, (a) based on personal dominance and authoritarian behavior, (b) that serves the self-interest of the leader and is self-aggrandizing, and (c) is exploitive of others (House and Howell 1992, p. 84). It is widely viewed as an unethical form of charismatic leadership (Howell and Avolio 1992; Shamir et al. 1993).

Hypothesis 3

Followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ are related positively to their ratings of their leader’s socialized charismatic leadership (H3a) and negatively to their ratings of their leader’s personalized charismatic leadership (H3b).

To assess discriminant validity, analogous to Brown et al. (2005), we examined the leader demographics, of age, gender, and education as they should be unrelated to the VLQ.

Hypothesis 4

Followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ are unrelated to leader (H4a) age, (H4b) gender or (H4c) education.

The Criterion-Related Validity of the VLQ

As a type of trait associated with “good” character, virtues should influence people positively. Consistent with Hackett and Wang (2012), three positive impacts of virtuousness, namely, behaving ethically, personal happiness, and superior role performance, were anticipated. Further, as explained below, as a measure intended to gage leader virtues reflective of “good” character, the VLQ should positively associate with both leader and subordinate ethical behavior, as well as their happiness and overall life satisfaction.

In “The Nicomachean Ethics” (Irwin 1999), Aristotle suggested that virtuous actions are good and pleasant and that virtuous people are enduringly right. Cavanagh and Bandsuch (2002) expanded this view to argue that virtuous persons, including those in leadership positions, are naturally inclined to enjoy behaving ethically, which is aligned with the notion that they grasp and are especially sensitive to the morally salient features of situations (Alzóla 2012; Johnson 2009). Empirically, positive relationships between four Aristotelian cardinal virtues (prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice) and ethical leadership behaviors have been found among managers from a variety of industries (Riggio et al. 2010).

Hypothesis 5

Followers’ ratings of their leaders’ virtuousness as measured by the VLQ are related positively to their ratings of their leader’s ethicality.

As explained earlier, virtuous leaders, owing to their referent power, are likely to be role models for their followers (Brown et al. 2005; Yukl 2010). By observing and imitating their leader’s virtuousness, followers experience an intrinsically self-reinforcing inclination toward moral goodness (Cameron 2011) and develop a motivational disposition to behave ethically (Whetstone 2005). Indeed, supervisor role modeling of ethical behavior is positivity associated with follower ethical intentions (Ruiz-Palomino and Martinez-Canas 2011). Further, leaders’ virtuous behaviors nourish and reinforce an ethical climate (Hannah and Avolio 2010; Neubert et al. 2009) which in turn, is positively associated with ethical behavior among employees (cf. Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). Thus:

Hypothesis 6

Followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ are related positively to leaders’ ratings of their followers’ ethicality.

In “The Nicomachean Ethics” (Irwin 1999), Aristotle argued that practicing virtues provides happiness that amusement cannot; and that a happy life is one lived in accordance with virtues (also see Flynn 2008). As conceptualized in the psychological literature, Aristotelian happiness is reflected by affective happiness and life satisfaction as these are outcomes associated with the prompt satisfaction of individual needs and attainment of individual goals (Diener et al. 1999). Indeed, virtues have positive impacts on one’s happiness and life satisfaction (see Page and Vella-Brodrick 2009 for a review). Practicing virtues is thought to provide people with meaning, to help satisfy holistic needs (Bass and Steidlmeier 1999) and aid in achieving personally valued goals (Arjoon 2000; MacIntyre 1984). In all, the practice of virtuous leadership should be positively associated with the happiness and life satisfaction of the leader. Moreover, to the extent that leader virtues are imitated and amplified by followers (Cameron et al. 2004; Neubert et al. 2009), resulting in enhancements to their moral identity (Weaver 2006), follower happiness and life satisfaction should be positively impacted as well.

Hypothesis 7

Virtuousness leadership as assessed by followers is positively associated with leaders’ self-reported happiness (H7a) and life satisfaction (H7b), as well as their followers’ self-reported happiness (H7c) and life satisfaction (H7d).

In “The Nicomachean Ethics” (Irwin 1999, p. 25) Aristotle stated “It should be said, then, that every virtue causes its possessors to be in a good state and to perform their functions well.” Virtuous people should become excellent in performing their jobs, as they strive to be competent and fulfill requirements in the right way (Ciulla 2004). For leaders, good role performance entails demonstrating effective leadership, which virtues should foster in at least two ways. Firstly, effectiveness is enhanced by the amount of power the leader has and the manner in which it is exercised (Yukl 2010). Specifically, as explained earlier, practicing virtues should enhance a leader’s referent power—an especially impactful form of influence. Virtuousness should also guide leaders to exercise power prudently, judiciously, and humanely without self-aggrandizement (Alzóla 2012; Bass and Steidlmeier 1999). Secondly, leaders who are trusted and respected by those around them (Gao et al. 2011) gain idealized influence, enhancing their effectiveness (Bass and Riggio 2006). Empirically, leader virtuous behavior is positively associated with leadership effectiveness (Sosik et al. 2012) and with objective organizational performance (Cameron 2011).

Hypothesis 8

Virtuous leadership, as evaluated by followers, associates positively with followers’ perceptions of leader effectiveness.

For followers, there are at least three ways in which exposure to virtuous leadership should foster excellent job performance. Firstly, virtuous behaviors instill meaning in the work (Bass and Riggio 2006). Secondly, virtuous leadership conveys care for the well-being of followers and their community (MacIntyre 1984; Solomon 1999), nourishing perceived organizational support (Shanock and Eisenberger 2006). Thirdly, as noted earlier, virtuous leader behaviors garner followers’ trust (Gao et al. 2011). Empirically, the positive effects of inspirational motivation, perceptions of organizational support, and trust in the leader, on in-role and extra-role follower performance, are well documented (Bass 1985; Dirks and Ferrin 2002). More directly, the practice of virtues by leaders (e.g., integrity and humanity) associates positively with follower in-role (Hannah et al. 2005) and extra-role (Palanski and Yammarino 2009; Thun and Kelloway 2011) performance.

Hypothesis 9

Virtuous leadership, as evaluated by followers, positively predicts followers’ (H9a) in-role and (H9b) extra-role performance as rated by supervisors.

The Incremental Validity of the VLQ

It is of both theoretical and practical interest to examine whether the VLQ is related to important criteria after other forms of leadership are controlled. Thus, in line with Peus et al. (2013) we also assessed the utility of the VLQ by examining its incremental validity; that is, the degree to which it accounts for variance in valued outcomes beyond that of other leadership constructs. Specifically, we examined whether the VLQ related to important criteria after controlling for (a) the VLS (as completed by the leader; Sarros et al. 2006) and; (b) socialized charismatic leadership (Galvin et al. 2010), and/or (c) personalized charismatic leadership (Popper 2002)—both follower-assessed.

Hypothesis 10

The VLQ has explanatory power with regard to leader and subordinate ethical behavior, happiness and overall life satisfaction, beyond that of the VLS and socialized and personalized charismatic leadership.

Sample and Procedure

To test the hypotheses stated above, two surveys were made available on the FluidSurveys website. One was open to people holding a paid supervisor/manager position; the other was open to their direct subordinates. The StudyResponse Center for Online Research (Syracuse University) helped recruit 381 follower-leader pairs. The respective surveys were completed by 286 supervisor/managers and 300 subordinates, yielding 230 dyads, a 60 % response rate.

The sample consisted of 131 (57 %) male and 99 (43 %) female supervisor/managers and 129 male (56 %) and 101 female (44 %) subordinates. Almost all of the managers/supervisors (95 %) and subordinates (94 %) lived in the US, with the remainder residing in Canada or the UK. Among the leaders, 50 % were 31–40 years of age, 71 % had a graduate degree, and 57 % had fewer than 20 direct subordinates, while 64 % were in a working relationship with their follower for less than 15 years. Among subordinates, 52 % were 31–40 years of age, and 58 % had a graduate degree. Nearly half of the dyads (112, 49 %) worked in business services, 71 (31 %) in manufacturing, 39 (17 %) in public administration, and 8 (3 %) were in the mining, oil, and gas industries.

Measures

The scales below are five-point Likert-type (1 = Never; 5 = Always) unless noted otherwise.

Virtuous Leadership

Followers used the 18-item VLQ to evaluate their leader (α = .96) on each virtue. An overall score was also derived by summing the scores of each of the five virtues.

VLS

The seven-item VLS (Sarros et al. 2006; α = .84) was used to provide a self-assessment of leader character; e.g., “I consistently adhere to a moral or ethical code or standard” and “I invoke laughter and see the funny side of a painful predicament.”

Socialized Charismatic Leadership

Eight idealized influence and inspirational motivation subordinate-rated items from the short-form MLQ (cf. Galvin et al. 2010; α = .92) were used; e.g., “My supervisor talks about his/her most important values and beliefs,” and “My supervisor specifies the importance of having a strong sense of purpose.”

Personalized Charismatic Leadership

Subordinates completed the five-item scale in Popper (2002; α = .84); e.g., “My supervisor uses his/her influence for personal benefit,” and “My supervisor uses the team to promote his/her personal success.”

Leader Demographics

Five categories each reflecting increased years, were used to assess both leader and follower age and education. Gender was coded as 1 = Male; and 2 = Female.

Machiavellianism

Leaders completed the 20-item Machiavellianism IV Scale (Christie and Geis 1970; α = .80); e.g., “Never tell anyone the real reason you did something unless it is useful to do so,” and “The best way to handle people is to tell them what they want to hear.”

Leader Ethicality

Assessed by followers, the ten-item Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS Brown et al. 2005; α = .90–.94) was used; e.g., “Conducts his/her worklife in an ethical manner”; “Discusses success not just by results but also by the way that they are obtained.”

Leader Effectiveness

Followers completed four items from the MLQ (Bass and Avolio 1995; α = .87–.93); e.g., “Is effective in meeting others’ job related needs”; “Is effective in representing their group to higher authority.”

Follower Ethicality

Leaders rated their follower using six items adapted from Singer (2000; α = .84–.91); e.g., “Is honest”; “Can be trusted.”

Happiness

Both leaders and followers completed a five-item self-assessment adapted from the Personal State Questionnaire (Brebner et al. 1995; α = .93); e.g., “I always laugh these days”; “Things always work out the way I want them to.”

Life Satisfaction

Both leaders and followers completed the five-item self-assessment Satisfaction with Life Scale (Emmons and Diener 1985; α = .86–.90); e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”; “The conditions of my life are excellent.”

Follower In-Role Performance

Leaders used four items adapted from the scale in Lynch et al. (1999; α = .91); e.g., “Fulfills responsibilities specified in job description”; “Performs tasks that are expected of him/her.”

Follower Extra-Role Performance

Leaders used six items adapted from the scale in Lynch et al. (1999; α = .88); e.g., “Helps co-workers who have been absent”; “Helps co-workers who have heavy workloads.”

Control Variables

For the hypotheses concerning criterion-related validity, multiple regressions were used to control for follower/leader age, gender, education, and relationship tenure (in years). These variables may influence perceptions concerning ethical behavior (Brown et al. 2005), role effectiveness (Hooijberg et al. 2010; Neufeld et al. 2010), happiness, and life satisfaction (Becchetti et al. 2008; Kim and Kim 2009).

Results

CFA

The 18-item five correlated factors model from Study 1 was applied to the VLQ Study 2 subordinate sample (n = 230). The overall fit was good in that the χ 2/df, (199.71/125) ratio was less than 3.00, the RMSEA was .05, and both the CFI (.98) and NFI (.94) exceeded .90 (cf. Meyers et al. 2006; Worthington and Whittaker 2006). Also, as in Study 1, the standardized factor loadings associated with the items were all significant (see Table 2).

The correlations among the factors are shown in Table 3. Since the correlations were all quite high (.71 or above), a single-factor model was also considered, but many of the fit indices (e.g., χ 2/df, = 3.00; NFI = .88; RMSEA = .09) were not within their respective acceptable ranges (cf. Meyers et al. 2006; Worthington and Whittaker 2006).

The highest correlations among the factors involved justice with both prudence (r = .85) and humanity (r = .83); while the remaining values ranged from .71 to .79. The empirical evidence supporting these five highly related factors is an improvement over previous efforts to assess leader character. For example, the LVQ (cf. Riggio et al. 2010) reflects a single factor and the CSLS (cf. Thun and Kelloway 2011) reflects three dimensions. Finally, Table 3 shows Cronbach αs ranging from .84 to .96, reflecting good internal consistency reliability for each of the virtues and for the VLQ overall.

The Convergent and Discriminant Validity of the VLQ

Table 4 shows the correlations among the major variables in Study 2 required for testing a sub-set of the hypotheses. In line with Hypothesis 1, followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ correlated positively with their leader’s self-assessment of virtues as measured by the VLS (r = .64, p < .001). Hypothesis 2 was also supported; specifically followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ related negatively to their leader’s self-assessment of Machiavellianism (r = −.37, p < .001). Hypothesis 3a stipulated that followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ relate positively with their ratings of the leader’s socialized charismatic leadership, and this also was supported (r = .83, p < .001). Contrary to Hypothesis 3b, however, followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ were positively related to their ratings of their leader’s personalized charismatic leadership (r = .17, p < .05). Finally, consistent with our expectations, followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness (as measured by the VLQ) were unrelated to leader age (r = −.05), gender (r = −.03) or education (r = −.03). Hypothesis 4a, 4b and 4c were all supported.

In all, these findings support the convergent and discriminant validity of the VLQ. The only contrary finding, a relatively weak positive association between the VLQ and personalized charismatic leadership, might be explained by personalized charismatic leaders behaving ethically in crises situations (Fatt 2000), or when their self-interests and those of the collective coincide (Deluga 2001). Consistent with this possibility, but contrary to previous studies (Howell and Avolio 1992; Popper 2002), personalized and socialized charismatic leadership were positively correlated (r = .20, p < .01; see Table 4). This fuels the on-going debate concerning the degree to which the distinctions between personalized and socialized charismatic leadership are clear-cut (Brown et al. 2005; Howell and Avolio 1992).

The Criterion-Related Validity of the VLQ

The multiple regression findings in Table 5 support Hypothesis 5; followers’ ratings of their leaders’ virtuousness, as measured by the VLQ, related positively to their ratings of their leader’s ethicality (β = .79, p < .001), controlling for follower age, gender, education, and relationship tenure (years working with the supervisor). Hypothesis 6, that followers’ ratings of their leader’s virtuousness as measured by the VLQ are related positively to leaders’ ratings of their followers’ ethicality, was also supported (β = .49, p < .001). Importantly, this implies that leaders who were regarded by their followers as virtuous viewed their followers to be more ethical, controlling for leader age, gender, education, and relationship tenure (years working with the subordinate).

As anticipated, with leader age, gender, and education entered as controls, the subordinate-rated VLQ was positively associated with both leader happiness (β = .57, p < .001), and life satisfaction (β = .49, p < .001); whereas controlling subordinate age, gender, and education, the VLQ related positively to both follower happiness (β = .61, p < .001) and life satisfaction (β = .54, p < .001). These results support our hypotheses that virtuous leadership as assessed by followers is positively associated with leaders’ self-reported happiness (H7a) and life satisfaction (H7b), as well as followers’ self-reported happiness (H7c) and life satisfaction (H7d).

Hypothesis 8, that virtuous leadership, as evaluated by followers, associates positively with followers’ perceptions of leader effectiveness, was supported (β = .70, p < .001), with follower age, gender, education, and relationship tenure controlled. Finally, as anticipated, VLQ-based follower ratings of leader virtue were positively correlated with both follower in-role (β = .42, p < .001) and extra-role (β = .50, p < .001) performance as rated by the leader, supporting Hypotheses 9a and 9b, respectively.

The Incremental Validity of the VLQ

The hierarchical regression findings presented in Table 6 generally provide strong support for Hypothesis 10, that the VLQ has explanatory power with regard to leader and subordinate ethical behavior, happiness, and overall life satisfaction, beyond that of the VLS, and socialized and personalized charismatic leadership. For example, for each dependent variable, Model 1—Step 1 shows the variance accounted for by the VLS (a self-assessment of leader virtue) alone, compared to Step 2 in which the VLQ is added as a predictor. The increase in the variance accounted for in Step 2 is significant for all the dependent variables except follower in-role performance. Moreover, some of the increases are especially large and of theoretical interest. For example, as shown in the first column of Table 6, self-assessed virtue (i.e., as assessed by the VLS) predicts follower-rated leader ethicality (β = .52, p < .001), but adding the VLQ as a predictor (β = .74, p < .001) increases the variance accounted for by 32 %.

Model 2 in Table 6 shows socialized charismatic leadership entered in Step 1, followed by the VLQ in Step 2. Here, the incremental variance accounted for by the VLQ is significant for all the dependent variables. Similarly, Model 3, where personalized charismatic leadership is entered in Step 1, the entry of the VLQ in Step 2 is significant in all cases. Finally, in the most demanding test, Step 1 of Model 4 encompasses the VLQ, as well as both socialized and personalized charismatic leadership. Even here, adding VLQ in Step 2 results in significant increases in the variance accounted for in follower-rated leader ethicality (∆R 2 = .08, p < .001), leader effectiveness (∆R 2 = .05, p < .001), as well as both follower happiness (∆R 2 = .07, p < .001), and life satisfaction (∆R 2 = .04, p < .01) (See Table 6). Collectively, these findings strongly support the added, unique contribution of a behaviorally based multidimensional measure of leader virtues in predicting the criterion variables studied here.

A summary of the findings related to testing each hypothesis is provided in Table 7.

Discussion

We used a theoretically grounded, multi-study approach to propose and develop a measure of virtuous leadership based upon the virtues ethics literature. Findings from two studies lend empirical support for virtuous leadership (assessed by the 18-item VLQ) being conceptually and empirically distinct from other leadership concepts, and positively predictive of a range of desirable leader and follower outcomes, including ethical conduct, general happiness, life satisfaction, and job performance.

Theoretical Contributions

The VLQ is fully grounded in the virtues ethics literature, spanning Eastern and Western thinking and is distinguishable from other well-known leadership perspectives. It is character-based, ethical by nature, and entails three central elements—leader virtues, leader virtuous behaviors, and context—and emphasizes the intrinsically motivated self-cultivation of virtue. Building on Riggio et al. (2010) and models of character-based leadership (Hannah and Avolio 2010), perceptual and attributional processes were articulated through which followers are seen as receiving inspiration and intrinsic rewards by imitating the virtuous behaviors of their leaders. Ultimately, the happiness and life satisfaction of both the follower and leader are impacted, as are their ethical behaviors and workforce effectiveness. Our hypothesized processes, combined with the VLQ, should catalyze research on character-based leadership, including the identification of additional multi-level explanatory processes and influences, and the examination of mediators and moderators of various virtuous leadership-outcomes relationships.

Relative to existing assessments (e.g., Riggio et al. 2010; Thun and Kelloway 2011), the VLQ is heavily behavioral in content and taps five of the six, albeit highly correlated, cardinal leader virtues (courage, temperance, justice, prudence, and humanity) identified by Hackett and Wang (2012) as universally relevant. Convergent validity was demonstrated via CFA and by positive correlations with (a) the VLS (Sarros et al. 2006), a measure of leader virtue; (b) socialized charismatic leadership (Brown and Treviño 2009; Galvin et al. 2010); and by (c) a negative association with Machiavellianism, a negative character trait (cf. Christie and Geis 1970). Discriminant validity was shown by (a) CFA results indicating that the five-factor model was a better fit than a single-factor representation; and (b) the lack of association with leader age, gender, and education. Finally, evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity was shown by positive associations of the VLQ with follower and leader ethical behavior, life happiness and satisfaction, as well as workplace effectiveness.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

We offer seven directions for future research that address weaknesses in our study and/or advance the field. First, even though the empirical evidence supported a five-factor model, like Riggio et al. (2010), the magnitude of the correlations among the virtues was high, especially given that participants in the scale development process were readily able to appropriately categorize items as intended in the virtues ethics literature. We agree with Riggio et al. (2010) and others (e.g., Tsui 2013) that distinctions among the virtues are nonetheless likely to be important in management development contexts where their differential applicability to common business situations is clearly apparent. For example, temperance and humanity were clearly relevant in the suicide of Pierre Wauthier, the CFO at Zurich Insurance Group, which was attributed in large part to the “pressure cooker” atmosphere created by the company chairman (Enrich and Morse 2013). Stan Shih, the founder of Acer recently invoked concepts based upon Confucian teachings while lecturing senior management on the importance of practicing humane governance as a key to long-term success, even (if not especially) in the face of restructuring (Dou 2013). Further efforts to improve the level of empirical distinctiveness of the virtues may also be in order, for example, by considering a slightly modified set of virtues (cf. Crossan et al. 2013; Wright and Goodstein 2007).

Second, the VLQ should be used with other populations of employees. For example, the StudyResponse research pool we used may be biased with regard to the proportions of religious affiliations represented (see Walker 2013, p. 455). Also, although Study 2 participants were solicited from a variety of industries, the sample was based almost entirely in the U.S.; hence, any culture-specific leader behaviors and processes were likely missed. This is potentially important since, for example, The Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Project (GLOBE; House et al. 2004) found that people in eastern countries (e.g., China, Japan, and South Korea) consider humanity a more important leader attribute relative to courage, than do people from western countries (e.g., Germany, UK, and the US). Though we, as explained earlier, view the virtues assessed by the VLQ as culturally universal, others may not (Mele 2005). Thus, it would be of value to extend this research to a sample of employees with multicultural backgrounds, having them complete the VLQ on the same leader (e.g., the CEO).

Third, longitudinal research is needed to enhance the ability to make causal inferences and to address the temporal aspects of our model. For example, our cross-sectional design does not rule out the possibility that happy, life satisfied, ethical followers tend to see their leader as behaving virtuously. Also, our design was insensitive to the notion that time is required for the attributional and perceptual processes associated with the amplification effect to occur—so that the leader is perceived as virtuous and worthy of modeling, enabling followers to experience the intrinsic and career-related benefits of virtuous behaviors. Longitudinal designs are also required to evaluate whether virtues are acquired and sustained through practice and habituation.

Forth, studies concerning the VLQ and virtuous leadership generally would benefit from the use of a variety of measurement methods and sources. For example, we collected ratings of the independent variable (virtuous leadership) and four of the dependent variables (ethical leader, leader effectiveness, and follower happiness and life satisfaction) from the same source (subordinates), which could generate common method bias (Conway and Lance 2010). On the other hand, consistent with the Conway and Lance’s (2010) recommendations, it is important to emphasize that subordinates by definition, are the appropriate source for most of this information. Also in line with Conway and Lance (2010), a strong argument to counter method bias concerns, namely evidence of construct validity, was provided. Nonetheless, other approaches to measuring leader virtue that are less reliant on subordinate ratings are available, such as situational assessments (Dyck and Kleysen 2001), text analysis (Gao et al. 2011), and case studies (Cameron 2011). It would also be of value to collect VLQ assessments from other sources (e.g., peers and customers) and to examine their relationship to non-rating measures (e.g., financial indices) of performance. Of course, several of the relationships we reported involved multiple sources (i.e., ratings provided separately by followers and their leaders).

Fifth, though our efforts to develop and test a model of virtuous leadership were targeted solely at the individual level, multi-level research is called for as well. For example, as noted earlier, POB scholars have discussed the positive effects of virtues on the group and organization levels (e.g., Cameron et al. 2004). Thus, it is reasonable to expect that aggregated VLQ scores will associate positively with group and/or organizational ethics, well-being, and effectiveness.

Sixth, the incremental validity of virtues for predicting ethical behaviors, happiness, and effectiveness should be further assessed beyond the initial evidence presented here. Specifically, a new approach to leadership measurement should be justified both within and across leadership domains (Derue et al. 2011). Within-domain evidence would entail empirically comparing the VLQ to both the LVQ (Riggio et al. 2010) and the CSLS (Thun and Kelloway 2011). Indeed, we would have done so, but these assessments were published after we completed our studies. The incremental value of the VLQ and other character-based assessments need also to be evaluated across predictor domains (cf. Derue et al. 2011) since other classes of variables such as leader personality, values, and competencies are associated with leader ethical behavior (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010), happiness (DeNeve and Cooper 1998), and effectiveness (Bass 1985) as well. Further, since there are links between certain philosophical and religious beliefs concerning virtue (Walton 1988), it would also be of interest to include a religiously oriented scale (e.g., the Faith at Work Scale; Walker 2013) in any further examination of the incremental value of the VLQ for predicting leader life satisfaction and happiness.