Abstract

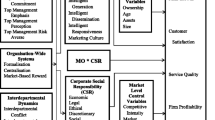

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become of great interest to both researchers and practitioners alike with much discussion on whether the costs outweigh the performance implications. CSR has become a firm strategic tool (not only an ethical concept) as firms recognize that the customer value proposition and CSR is integrated with the focus on how to differentiate the firm from the view of the customer. We utilized market orientation (MO) theory as our foundation for our research as it explains how organizations adapt to their customer environment to develop competitive advantages. With the current customer focus on CSR, MO assists the field in identifying a possible firm differentiation. Our research found that firms that ranked high on CSR correlated positively to performance. We also found our theoretically developed constructs of firm customer orientation (CO) and firm market orientation correlated with the firm adopting CSR. The results also indicated that CSR positively mediates CO and MO to firm performance. As past research had mixed results over the direct relation of MO to performance, our research suggests that CSR may be the missing variable to explain the MO/Performance relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s globalized marketplace, firms are faced with more complex and diverse interactions of multiple stakeholders simultaneously. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has now become increasingly important due to global pressures from these various stakeholders (Öberseder et al. 2011). Firms now need to apply a broader market approach that extends outside its traditional boundaries to better serve firm objectives (Kang 2009; Lopez et al. 2007; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009) as customers are increasingly better organized, more informed and more demanding and now have included an interest in CSR (Appiah-Adu and Singh 1998; KPMG 2011). But researchers are still exploring whether CSR is a cost or a benefit, with mixed results.

CSR research suggests that new efforts should be directed toward how firms create mutual value with their customers (Bondy et al. 2012; Harrison et al. 2010), how to increase the interaction between firms and their customers (Du et al. 2010) and how CSR can provide mutual benefits (Nielsen and Thomsen 2010; Ziek 2009). It is thus important to focus directly on customers and not on stakeholders in general (Wood 2010). Few studies explore the interaction of CSR with customers (Lee 2008) as customers have in general been ignored in the CSR research field (Gadenne et al. 2009). Our research therefore intends to assist in the field by exploring aspects of CSR/customer and the resultant impact on firm performance.

The emergence of internet based social networks (ex. Twitter, Facebook, etc.) have increased pressure on firm behavior and on how businesses present themselves to the community (Gebhardt et al. 2006; Hill et al. 2007; Kang 2009; Lopez et al. 2007). As such, firms now assess and apply CSR as a key determinant for firm long-term performance (Ramchander et al. 2012; Stainer 2006), and reputational effects (Carroll and Shabana 2010; Freeman et al. 2004; KPMG 2011; Melo and Garrido-Morgado 2012; Miller 2004). Further, research now suggests that prioritization of CSR is crucial for firms globally (Porter and Kramer 2006). A recent study found 70 % of global chief executives (CEO’s) claimed CSR to be vital to their company’s profitability (Carroll and Shabana 2010). CSR has transformed from being a ‘good-will’ concept into becoming a business function, a strategic marketing component of central importance to firm level success (Carroll and Shabana 2010; KPMG 2011; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009), and a vital part of a firm’s marketing strategy (Bondy et al. 2012; McWilliams and Siegel 2011; Noland and Phillips 2010).

Unfortunately, CSR research has mixed results in regard to its relationship to performance. Some current CSR research suggests positive long-term effects such as differentiation effects from a customer perspective where firms gain competitive advantages from CSR (Carroll and Shabana 2010) and improved reputation (Fombrun 2000; Jackson 2004; Melo and Garrido-Morgado 2012). Other performance measures that have been used by researchers to assess the CSR/performance relationship are employee commitment to work, sales performance (Kang 2009; Porter 2008; Wieseke et al. 2009) as well as levels of employee turnover (Carroll and Shabana 2010; DeTienne et al. 2012).

A key theoretical foundation for firms in regard to the focus on the customer is market orientation (MO) which consists of intelligence gathering, dissemination and then a firm’s management’s subsequent tactics to implement this new market knowledge (Kohli and Jaworski 1990). Similar to CSR, MOs direct correlation to performance has mixed results and may be contingent upon other variables (Augusto and Coelho 2009). We combine both streams of research and suggest that the theoretical foundation of MO in today’s marketplace suggests that customers want firms to be CSR-centric and when MO focused firms gather this knowledge they will implement CSR. Therefore we include CSR as a mediator to firm performance as it will be a successful tactic that will satisfy the needs and wants of the target customers.

Our research assists and contributes in several ways. We utilized market orientation theory (MO) as a foundational setting which explains how organizations adapt to their customer environment and focus on serving customers to develop competitive advantages. There is a dearth of research utilizing MO in past research in regard to CSR, yet we argue from that theory that the customer has the greatest impact on firm performance. Customers have the ability to switch to another firm; customers are now more than ever concerned about the environment; and are well informed through social media. MO suggests that firms focus on the current and future value proposition of their customers and those that do so will differentiate themselves from their competitors and will reap economic benefits. Utilizing the MO literature we focus on its constructs of customer orientation, customer interaction and market orientation to determine if firms with this focus will also then develop CSR.

Our empirical research targeted the top 100 publicly traded firms (of which we had 82 % return rate for our survey) of the Swedish stock market. Our results suggest that firms that are customer oriented and are market oriented will correlate positively with CSR programs, and that firms with CSR programs will have higher performance. Our results indicate a mediating effect of CSR to customer orientation and market orientation to performance.

Review of the Corporate Social Responsibility Literature (CSR)

CSR is defined as a commitment to improve societal well-being through discretionary business practices and contributions of corporate resources (Du et al., 2010; Kotler and Lee 2005). Examples of CSR internal to the workplace are on-site child-care provision for employees, developing non-animal testing procedures, re-cycling or implementation of internal environmental improvement programs (McWilliams and Siegel 2001a). CSR external to the workplace can be the support of local businesses, fighting deforestation and global warming, supporting minorities, implementing external environmental improvement programs, or provide disaster relief.

There is a stream of research that suggests firms should not be involved in CSR. This research argues that firms do not have the capabilities necessary for the allocation of firm resources for the good of society, and those firms should not waste resources on CSR but instead should focus on the owners (stockholders). The argument continues that firms should not be assisting in society, as social or environmental issues should be addressed by individuals through donations or by governments via tax revenue and not by firms unless legislated (Friedman 1970). Friedman’s research suggested that firms should focus on profit maximization for its shareholders within the framework of the society’s norms. A firm should not be spending firm money and resources at furthering social objectives but should be directed at improving the efficiency of strategic operations. This line of thought continues as a major argument against CSR.

Contrary research suggest profit should not be the only social responsibility of a firm and that firms ‘must do good to do well’ and that firms, not governments, are best suited to deal with social improvements as firms are faster and can more easily commit resources (Drucker 1984). Freeman (1984) suggests that a firm’s success is partially a function of how managers allocate resources to further social performance objectives. That research suggests that it is an unavoidable cost of business to address the demands of several constituent groups at the risk of destroying shareholder value. Other research suggests that CSR creates corporate identities, reputations, and images that gain and maintain competitive advantage (Hosmer 1994). CSR may develop perceptions of trust and cooperation among stakeholders which can be sources of long-term value creation (Barney and Hansen 1994).

Current research now focuses on CSR not targeting societal well-being only, but how it assists firm performance. Hence, the focus has advanced CSR to being a strategic tool (from being only an ethical concept) with the organization as unit of analysis (instead of the society at large). One such example is where R&D efforts target socially preferable product attributes such as pesticide free produce (KPMG 2011), process attributes (for example organic cultivation) (McWilliams and Siegel 2001a) or green marketing (Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). Firm specific examples are Marriott Hotel’s training program for chronically unemployed people. This training program focus is for higher retainment for low level entry positions. Another example is Microsoft’s community college education program which improves IT education standards to increase their future recruitment pool (Porter and Kramer 2006).

Three core problems hinders CSR success: managers have ‘too little knowledge about the overall concept’ (38.6 % of respondents), ‘too little knowledge of the CSR implementation process’ (43.2 % of respondents) and that 56.8 % of the responding managers lack ‘a clear action plan’ (Moratis and Cochius 2011). Implementation issues typically arise for the same reasons. For example, as CSR needs to be aligned with overall firm level objectives and strategies, CSR-related organizational adjustments and changes can be a challenge (Kang 2009). Thus CSR needs to be strategic in order to create and capture value (McWilliams and Siegel 2011).

Theoretical Foundation: Market Orientation Theory

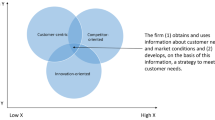

The market orientation (MO) theory is a business philosophy or a policy statement which addresses how organizations adapt to their customer environment to develop competitive advantages (Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Hurley and Hult 1998; Liao et al. 2010; Slater and Narver 2000). MO-related competitive advantages can arise from closer ties (Hyvönen and Tuominen 2007) or increased loyalty (Kirca et al. 2005) which is crucial in an ever-changing business environment (Alhakimi and Baharun 2010; Aziz and Yassin 2010; Liao et al. 2010).

MO assists firms as organizations and environments interact causing organizations to develop their own contextual strategy (Pinto and Curto 2007). MO firms obtain knowledge about their customers’ current and future needs and then act upon this knowledge to supply superior offerings (Slator and Narver 2000), this will differ per firm per environment (Ellis 2010), and the antecedents and outcomes of a MO will vary per marketplace (ex. Atuahene-Gime and Ko 2001).

MO as a theoretical foundation to explore CSR assists as both focus on obtaining firm competitive advantage through knowledge received from the customer. In detail, CSR and MO: (a) entail some organizational function that actively develops an understanding of customers’ current and future needs and the factors affecting them; (b) design activities or programs targeting a selection of customer needs, and (c) communicate these internally and externally (Kohli and Jaworski 1990). In other words, both CSR and MO refer to organization wide generation, dissemination, and responsiveness to market intelligence (Kohli and Jaworski 1990). It is further suggested by both the CSR literature and the MO literature to not only look for direct financial performance but for indirect (and sometimes less quantifiable) results as well, for instance improved brand image, increased quality perceptions and customer loyalty and stronger stakeholder relationships (Du et al. 2010; Kirca et al. 2005).

MO and CSR also have other similarities. MO has two distinctive viewpoints, that of being responsive and proactive (Narver et al. 2004). The proactive MO attempts to identify potential future needs that customers may not know they have and to identify and satisfy these latent needs. Proactive opportunities may be firm idiosyncratic or industry wide, or both (Song et al. 2010). CSR also functions as both a responsive and proactive tactic: reactive if the industry has adopted CSR and competitors are implementing for differentiation and customer attraction/retention, and proactive if the firm is on the first mover advantage in adopting CSR to differentiate their brand from their competitors or has identified a superior way of applying CSR.

An organization that utilizes MO: (a) obtains and uses information from customers; (b) develops a strategy which will meet customer needs; and (c) implements that strategy by being responsive to customers’ current and latent future needs and wants (Ruekert 1992). This means that to gain some benefits from MO application a firm must implement and use it to gain trust and credibility from its buyers (Kohli and Jaworski 1990). This is also the underlying traits for CSR. The application of quantitative research questions is also suitable as much of the MO research up to date have been qualitative in nature (Kirca et al. 2005).

Hypothesis Development

Customer Orientation and CSR

MO is a “customer-centric approach” (Day and Moorman 2013, p. 21), the customer should be viewed as a co-creator of value in the relationship (Vargo and Lusch 2004), and is the foundation for the customer orientation (CO) variable. CO requires firms to determine the current needs of the consumer through market information. CO is more focused in line with service dominant logic where current customers’ needs and wishes are identified for further augmentation.

CO is not focused on either B2B or B2C but is a marketing concept that can be successfully utilized in both relationships. Sellers of generic products may experience difficulty in developing a deep relationship, but where services are complex or uncertainty is involved, the greater the potential for relationship development (Berry 1983). By developing relationships, customers have a reason to remain loyal and ways to differentiate (Day and Wensley 1983), such as CSR, may be the causal link. Organizations are continuing to develop ongoing relationships spurring the concept of one-off transactions as markets have become more competitive with good service alone insufficient (Palmer and Bejou 1994).

Trends in the B2B illustrate the importance of CO and co-creators of value as firms have reduced their suppliers significantly to only a few (“shrinking the supplier base”) leading to long-term cooperative relationships. These relationships require communication, empathizing, and keeping promises (Berry and Parasuraman 1991) with the goal of long-term relationship satisfaction (Ramani and Kumar 2008). The concept of customer segmentation, promotion and distributed to, is being replaced with relational exchanges (Lusch et al. 2007).

CO focuses on current customer preferences, needs, and satisfaction. CO is much narrower than MO (which focuses resources on the broad marketplace, competitors and all stakeholders), and focuses on customers: their needs, expectations and complaints. The strength of this is making sure the current customer value proposition is correct, but is myopic and often fails to anticipate future marketplace changes or customer needs (Hamel and Prahalad 1994). The customer perspective often focus on metrics such as customer-perceived quality and value, customer-perceived levels of service and customer based order-to-delivery times (Kaplan and Norton 1992).

CO firms’ often survey their customers to find out the products and services they would like to see in the future and work with them to understand their long term goals utilizing a problem solving approach in the sales of their services/products (Lam et al. 2010). As such, firms that apply CSR initiatives prove to some extent to be willing to assess, change, adjust or develop their business activities to achieve some benefits in consideration of their customers. For example, firms interact with different types of customers to gain CSR-related cost reductions or to increase positive reputation (Moon and deLeon 2007; Naffziger et al. 2003). Since it could be vastly expensive to tend to every stakeholder need, firms apply CSR in a cost effective and efficient manner (Delmas and Toffel 2008; Donaldson and Preston 1995) and realize ‘good deeds’ in one area spill-over and create reputational effects in other areas (Kolk and Pinske 2006).

For example, McDonald’s contribution to children’s hospitals makes the overall firm appear socially responsible even though it is unrelated to their core business. Since stakeholder importance to firms also increases in general (Carroll and Shabana 2010; KPMG 2011) more firms are attempting to design their CSR agenda not only to provide some value to the market place but also to gain from it (Bansal and Roth 2000; Bondy et al. 2012; Kang 2009; Lev et al. 2011; Porter 2008).

When firms are customer oriented their CSR program can support the development of value in economic and societal terms (Drucker 1984; Murray and Montanari 1986; Wood 2010). This leads to an increasing demand that CSR should incorporate some specific strategic purpose, for example to enhance customer relationships or to build brand value (Gadenne et al. 2009) and not only provide some general benefits for the society at large (Drucker 1984). The above discussion regarding CO components provides our first hypothesis:

H1

Customer orientation is positively related to CSR.

Customer Interaction and CSR

MO is a customer-centric approach (Day 1999) as the firm needs to have an active interaction and dialog with its customers (Chen et al. 2012) and is the foundation of the customer interaction (CI) variable. This interaction can develop a dialog and deliver undiscovered market information about the customer, marketplace, and trends. The CI component of our research is an action oriented component of MO where meetings, coordinated interactions, and conversations are instigated by the firm with the customer to ascertain market knowledge and relationship development.

The CI variable is a formal component of direct interaction with the customer, such as sharing projects, having formal written procedures, strategic alliances of functional departments, and scheduled regular meetings together (Peloza and Papania 2008). If a firm intends to develop some CSR derived value they should include representatives of the customers in their CSR dialogues and if there is a formal component of their relationship, CSR can be part of the agenda (Murray and Mo ntanari 1986). Firm level CSR activities that have no support from their customers will not provide beneficial results (Carroll and Shabana 2010). This is important as customers have the ability to reward or punish a firm for their societal behavior should it not be satisfactory (Neilsen and Rao 1987; Peloza and Papania 2008; Ramchander et al. 2012).

Explicit knowledge that is not embodied in specific products or services may not be efficiently transferred. However, firm/customer relationships will identify, transfer and integrate of this implicit knowledge (Liebeskind 1996). Another consideration is the speed to which this knowledge is transferred. Direct customer interaction permits knowledge to be transferred more quickly than relying purely on the market (Grant 1996; Eisenhardt and Galunic 2000). Customer value is constantly changing as their expectations are dynamic providing challenges that only direct interaction and feedback can ascertain (Eggert et al. 2006). Ignoring or missing shifts in customer needs could cause customer dissatisfaction and at the extreme, termination of the relationship (Beverland et al. 2004).

Thus, firms should realize that various customers’ needs and wants might be aligned with, or in conflict with, a firm’s CSR actions (Lev, et al. 2011). This contributes to the business environment complexity in that firms need to apply an extended market approach that goes beyond their customers (toward society at large) to better serve firm level objectives (Kang 2009; Lopez et al. 2007; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). Such extended market approach can in turn increase the firm-customer interdependency and bring organizational adjustments to better cater for them in regards to their needs and wants (Porter and Kramer 2006).

While it is common that firms choose to engage in CSR, it is equally common that it is initiated by some stakeholder category directly or indirectly via applied pressure from them. Customers for example (and to a large extent other stakeholder groups such as potential customers, suppliers, legislators, environmental groups and financial institutions) today call for firms to adapt environmental measures or standards and, or, to implement some CSR activities (Gadenne et al. 2009; Gummesson 2008). The review regarding customer interaction leads to our second hypothesis:

H2

Customer Interaction is positively related to CSR.

Market Orientation and CSR

The market orientation (MO) variable is broader and more future focused than the customer orientation (CO) focus and relies less on direct customer interaction (CI), as it attempts to predict trends and new value latent propositions for old customers while attempting to attract new customers. These firms include a focus on competition and their strategic moves, and the development of strategic tactics for future products/services. They also focus on the customer value proposition by understanding customer satisfaction, what the value of their products and services are to the customer, and the subsequent creation of new value for the customer (Ellis 2010).

Responsiveness to acquired market information is essential for MO to be successful. MO is the cultural foundation of the learning organization which is the successful instilling of a corporate culture for a sustained focus for acquisition and utilization of market knowledge (Dickson 1992). This market intelligence can consist of factors such as governmental regulations, competitors, technology, economics, customer trends, and environmental factors such as CSR (Oudan 2012). As firms are seeking both long term relationship development with customers, as well as a way to seek differentiation, the latest trends for customers seeking firms with high CSR will affect both.

Firms’ that have a stronger external orientation and actively monitor and manage their customers, also allocate more resources (to satisfy their needs and wants) to attract and keep them (Harrison et al. 2010). MO addresses how organizations adapt to their customer environment and apply a strict focus on serving customers to develop competitive advantages (Hurley and Hult 1998; Liao et al. 2010; Slater and Narver 2000). MO-related competitive advantages can arise from closer ties to customers (Hyvönen and Tuominen 2007) or increased customer loyalty (Kirca et al. 2005).

MO firms deploy the three pillars of the marketing concept (customer orientation, coordinated market interaction and profitability) and ensure these are manifested in its operations (Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Mulyanegara 2010). The proposition of the MO theory is that the success of a firm depends on how successful the top management team and individual managers are in managing their customer relationships (Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Ruekert 1992). The theory further calls for managers to communicate intended value creation to highlight what brings their customers together. It thus forces managers to clearly communicate how they want to do business and what type of relationships they want with their customers (Freeman et al. 2004; Kohli and Jaworski 1990).

H3

Market orientation is positively related to CSR.

Firm Performance and CSR

Opponents to CSR claim CSR to be outside the shareholders best interest and that the only social responsibility a firm has is to maximize profit for its owners (Friedman 1970). CSR opponents continue to repeat the view that firms should not engage in CSR due to uncertain financial effects or as a potential distraction from a firm’s business focus (KPMG 2011; Wood 2010). One area that the opponents and proponents agree upon is that profit arises from successful interactions with their primary market stakeholder—their customers. However, CSR proponents both address the economic argument and lack of business focus by arguing that immediate impact should not be sought (Carroll and Shabana 2010) as reputation just like branding takes considerable time to create and achieve. Research suggests that CSR instead should be viewed in a broader, holistic and long term perspective covering more than immediate financial performance (Carroll and Shabana 2010; KPMG 2011).

Other research suggests that while a direct financial performance enhancement is definitively possible (Ramchander et al. 2012), CSR-related financial performance can be unclear (Orlitzky et al. 2003). CSR is a holistic management philosophy that recognizes the existence of interdependency with society, and that CSR provides direct and indirect relationships with firm performance (Carroll and Shabana 2010). Conclusively, CSR can yield direct and indirect enhancements of performance financial or otherwise (Lev et al. 2011) through integration of market- and non-market strategies (Baron 1995).

A number of studies have also investigated the link between CSR and firm performance making the link well established with the causality from CSR to firm performance and not firm performance to CSR (Wood 2010). Yet, while it is possible that causation is a virtuous circle (simultaneous and interactive), the impact seems to be that improved CSR contribute to improved financial performance, ceteris paribus (Waddock and Graves 1997). Researchers are now recommended to leave the firm performance domain and instead focus on other CSR components and research questions (Carroll and Shabana 2010; Wood 2010). Although researchers have found positive, negative or neutral impact from CSR on firm performance (Orlitzky et al. 2003), the common view today is that the empirical findings support the link to be overall positive (Hill et al. 2007; Hull and Rothenberg 2008; McWilliams and Siegel 2000; Orlitzky et al. 2003; Wood 2010).

However, the relationship between CSR and firm performance is not always directly favorable as CSR brings added costs and mostly evolve around intangible asset creation like brand image and reputation (Carroll and Shabana 2010), and is therefore difficult to isolate using common evaluation and accounting techniques (Semenova et al. 2008). Despite potential measurement problems, it is claimed that a firm’s marke value can be increased by addressing the various needs of stakeholders (Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). The discussion regarding firm performance leads to our fourth hypothesis:

H4

CSR is positively related to Firm Performance.

Mediation of CSR to CO, CI, MO to Firm Performance

The impact of MO on performance has seen studied with the results suggesting a meditating role of other variables, for example that of relational capabilities (Smirnova et al. 2011). Although MO is an important antecedent to business success (Han et al. 1998) there potentially can be mediating factors associated with firm performance (Sivadas and Dwyer 2000). As MO’s primary objective is to deliver superior customer value, the current market trend of customers’ interest in CSR will cause MO focused firms to implement these programs for greater firm performance (Day 1994). Incorporation of the customers’ voice into the firm’s routines and strategies will improve both customer retention and profitability (Kumar et al. 2011).

Past research has shown MO to have a “strong positive”, “positive”, and “weak” relationship to firm performance although no research has included CSR as a mediating variable (see Liao et al. 2011 for a review). Mediating variables in prior MO research include: innovation, learning orientation, TQM implementation, and relationship commitment (Taylor et al. 2008; Demirbag et al. 2006; Menguc and Auh 2006; Wang and Wei 2005). As MO is a value creation technique for customers (Ulaga 2003) and CSR is of current value to customers, MO firms will implement CSR attracting new customers and retaining present customers. Recent research suggests that consumers’ willingness to purchase is largely based upon the perception of the firm in general and that CSR plays a large role in that perception (Smith 2012).

CSR has a positive correlation for customers on corporate brand and reputation (Hur et al. 2013) as customers prefer socially responsible firms and also prefer to be associated with these types of firms (Heikkurinen 2010). Market oriented firms are continuously assessing the needs and wants of customers for competitive advantage and will implement CSR as the strategic tool directly affecting their sales as CSR has been shown to develop favorable responses from consumers (Groza et al. 2011). As such, MO is the acquisition of information that will then utilize “tools” such as CSR to achieve greater firm performance.

Our model suggests a mediation of CSR to customer orientation, customer interaction, market performance to firm performance. Although some research has suggested that CO, CI and MO may lead to higher firm performance in the past, our research explores a CSR mediation effect. For example, although a majority of research suggests that market orientation is positively associated with performance several researchers have reported non-significant or negative effects with this association (Agarwal et al. 2003; Sandvik and Sandvik 2003). Perhaps the research on these variables is confounded by the lack of a mediation variable such as CSR. As the new emphasis is on CSR, firms will be required to have many competencies and CSR will be a key component. Hence we hypothesize:

H4a

CSR has a positive mediating effect on customer orientation to Firm Performance.

H4b

CSR has a positive mediating effect on customer Interaction to Firm Performance.

H4c

CSR has a positive mediating effect on market orientation to Firm Performance.

Sample description

Measurement of the CSR Construct

CSR has been argued to be difficult to measure and that valid and reliable measures may not be developed (Carroll 2000). We utilize Sweden’s CSR index, called the OMX-GES index. The first step to be on the OMX-GES index is that the top one hundred “most publicly traded” firms are selected. Secondly, the firms are then are rated in three key areas: rating of environment, rating of human rights and rating of corporate governance. These scores are calculated by NASDAQ OMX in cooperation with GES Investment Services, Northern Europe’s leading research and service provider for Responsible Investment. The criteria are based upon international guidelines for ESG issues and supports investor considerations to the UN Principles for Responsible Investments. GES Investment Service conducts the sustainability assessment by rating the companies according to their model “GES Risk Rating”. The analysis is based on international norms on ESG issues in accordance with the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI). GES Risk Rating evaluates both the companies’ preparedness (through management systems, etc.) as well as performance through a number of criteria and sub-criteria.

The companies obtain a rating from a Likert scale of 7 for each of the areas environment, human rights and corporate governance, and then a total score is calculated from an average of all three scores. The top 40 on the list is then published by greatest to least. We were able to attain the entire 100 firm list however. As an example of the scoring of the firms, the poorest performing firm, company 100, had a rating of the average of the three indexes of 0.62 out of 7, while the number one firm was 5.67 out of 7.

Sample

We were able to obtain the entire population of the 100 firms on the index for 2011. The top 100 firms have between $11.7 million USD to $33.3 billion USD in annual revenue, between 1,217 and 281,145 employees and an average MNE level of 81.9 % international sales versus 18.1 % domestic sales. The sample included industries of: Manufacturing 14, Retail 9, Banking 10, Real Estate and Hotel Management 10, Mining and Construction 15, Pharmaceutical and Biotech 11, Telecommunications and IT 8, Other (aerospace/defence/distribution/trading/airlines) 5, for a total of 82.

In total, there are 215 firms traded on the NASDAQ-OMX Stock Exchange, but only the top 100 highest traded firms are represented on the index. In turn this translates into an Index representation of 46.51 % of all the listed firms traded by NASDAQ-OMX. An additional 310 firms are also traded in Sweden outside NASDAQ-OMX’s operations. These are typically smaller firms in emerging industries that do not have sufficient firm level characteristics to qualify to the types of indexes of interest for research in CSR. In total we managed to collect completed questionnaire answers reaching a sample size of N = 88 for the quantitative research component, or 88 % from the 100 provided. We had to delete six questionnaires as they had left too many key questions unanswered, producing 82 usable surveys.

Our sample size success was collected due to an inordinate amount of time in personally contacting managers. We contacted each firm ranked on the complete Index (N = 100) separately. We personally called each firm’s switchboard asking for the executive manager in charge of CSR activities. In many cases the contact person was found on corporate websites or in annual reports. Where the switchboard operators hesitated to whom to connect us to, we asked for varying titles such as Vice President (VP) of CSR, the VP of Sustainability, the VP of Strategy or Business Development, the Chief Operating Officer (COO) or Chief Executive Officer (CEO) in that order. To reach each respondent we needed 2.4 calls on average where each phone call lasted for an average of 9 min. In total we made 247 calls and spent 37 h on the phone for this initial data collection phase. We further offered to provide an executive summary in return for their cooperation once the research is completed.

Non-response bias

Among the top 100 most traded firms on the Index we had only twelve firms that declined to participate (12 %). To test for nonresponse bias of the 12 firms that did not respond, we identified early to late responders per Armstrong and Overton (1977). Research has shown that late responders are similar to non-respondents so late responders can be used as a proxy for non-respondents. Actual survey responses are compared to determine if there are differences between the two groups. We found no significant differences.

Variable: Firm Performance

Return on Assets (ROA) is a firm performance measure that addresses earnings generated from invested capital (assets) independent from firm size. The reason is that it represents firms’ profitability in respect to total set of resources, that is, all assets in its control (Hull & Rothenberg 2008; Marcel 2009; Waddock and Graves 1997). ROA for public companies can vary substantially and be dependent on the industry they belong to. The assets in question are further the sort that is valued on the balance sheet, that is, fixed assets and not intangible assets like people, ideas or in this case CSR derived reputation. ROA has been widely used by CSR researchers to measure the impact from CSR on firm performance (Hull and Rothenberg 2008; Marcel 2009; Waddock and Graves 1997; Walls et al. 2012). Measure: ROA fiscal year earnings divided by total assets expressed as a percentage (Hull and Rothenberg 2008; Waddock and Graves 1997).

Variable: Customer Orientation

In order to develop an appropriate CSR program it is necessary to have sufficient understanding of a firm’s customer orientation (Mulyanegara 2010). To assess this external orientation component we applied Lam et al. (2010) set of questions. These questions measure the level of customer orientation on a seven-point Likert scale. The questions were developed to explore the extent a firm will see customer preferences as an important success factor; goal alignment with customer satisfaction and problem solving approaches in selling to customers. We applied six of their nine instruments. The questions were rephrased for our unit of analysis so they were not from an individual respondent’s perspective but to an organizational respondent’s perspective (i.e. questions were changed from ‘I focus on customer solutions’ to ‘we focus on customer solutions’). The three questions we did not use were specifically tailored for B2C not B2B as they addressed specific products for Lam et al. (2010) research, were in regard to salespeople directly, and are not appropriate for our purposes. The degree of Customer Orientation measurement was confirmed as valid by the reliability (consistency) test (Cronbach’s Alpha 0.854).

Variable: Customer Interaction

To receive feedback and customer suggestions about the CSR program we examined firm customer interaction. We applied 3 of Peloza’s (2006) set of four questions that measure the level of structured interaction with customers and suppliers and are measured on a Likert scale. These questions evolve around if firms have for example formal written procedures how to interact with the key market stakeholder (customers); regular scheduled meetings with customers or occasionally shared project organizations with their customers. The degree of Customer Interaction measurement was confirmed as valid by the reliability (consistency) test (Cronbach’s Alpha 0.653).

Variable: Market Orientation

To develop a CSR program based upon the theoretical foundation of market orientation we applied 6 of Ellis (2010) set of eight questions that measure the level of market orientation on a seven-point Likert scale. These questions evolve around firms’ view on for example knowledge of how customers value a firm’s products; how well they know their competitors or if various managers do field visits to customers to learn from them first hand. The degree of Market Orientation measurement was confirmed as valid by the reliability (consistency) test (Cronbach’s Alpha 0.766).

Control Variables

Control Variable: Industry Affiliation

Controlling for Industry affiliation is important in CSR research. CSR can for example be more common in mature industries like food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, financial services, utilities and automobile industry (McWilliams and Siegel 2001a; Simpson and Kohers 2002) than in more infant industries like ICT or on-line gaming. The type of CSR applied also differs across industries. Firms that prefer project specific contributions (i.e. random contributions) are more common in retailing and financial services (Lev et al. 2011). Firms with commodity type- or heavy industrial products are also more likely to engage in CSR efforts (Hult et al. 2007; McWilliams and Siegel 2001a). Industry affiliation is generally measured as a general industry coding practice applicable for a specific country (Siegel and Vitaliano 2007). We used the given MSCI index for each industry. The MSCI Global Sector Indexes are constructed using the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®), a widely accepted industry analysis framework for investment research, portfolio management and asset allocation jointly developed and maintained by MSCI and Standard & Poor’s. The MSCI Global Sector Indexes comprise regional and country sector, industry group and industry indexes based on the MSCI Global Investable Market Indexes.

Control Variable: Firm Size

The literature review reveals that Firm Size is frequently used as a control variable. One reason why researchers should control for size is that performance varies substantially across industries and larger firms may have more resources to utilize in CSR programs (Hull and Rothenberg 2008; Marcel 2009; Waddock and Graves 1997). One earlier calculation for Firm Size is total assets and total sales deployed in the firm (Waddock and Graves 1997). More recent research suggests to instead using the weighted average of a firm’s total assets (Hull and Rothenberg 2008). The weighted average was calculated over a three year period with a cumulative weight of 0.5. The full weight (1.0) was given to the value of the most recent year Y1 while a 0.5 weight were given to the value of each year Y−1, and a 0.25 weight were given to each year Y−2 (Hull 2011). We then take log of firm size since firm size shows a high variability and we needed to control for heteroskedasticity (McCulloch and Huston 1985).

Control Variable: Customer Categories

Since CSR differ across industries their customers will differ also (consumers (B2C), other businesses (B2B) or government customers (B2G) or combinations thereof). The cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, banking and utilities industries for example, all focus on different customer categories (McWilliams and Siegel 2001a; Simpson and Kohers 2002). The three customer categories consumers- (B2C), business- (B2B) or government customers (B2G) can affect firm willingness to undertake CSR differently (Naffziger et al. 2003). To exemplify, food and cosmetics firms are likely to focus on consumers (B2C) while pharmaceutical firms focus on their business customers (B2B). Banking and utilities are likely to focus on all three categories (B2C, B2B and B2G) given the nature of their business’ (for example supplying financial resources, electricity or water). In turn, the customer categories and the way firms orient their activities around them, can lead to formalized organizational structures which in turn can increase CSR efforts (Berkhout and Rowlands 2007). We therefore applied Delma and Toffel (2008) measure assessing to what extent firms’ have B2C customers (consumers); B2B customers (other firms); or B2G government or municipal customers (Delmas and Toffel 2008; McWilliams and Siegel 2001a).

Control Variable: Market Intensity

Previous research has recommended assessing the market intensity when researching firm performance in CSR research (Luo and Bhattacharya 2009; McWilliams and Siegel 2001a). The ratio of advertising spending to sales revenue (in monetary values) has been used as a measure to assess the market intensity expressed as a percentage (McWilliams and Siegel 2001a; Walls et al. 2012). Since the advertising expenditures were not retrievable in the annual reports in satisfying quantity we used the ratio of sales cost to sales revenue. This alteration of McWilliams measure maintain the purpose of assessing whether market-related costs affect firm performance in CSR research contexts (Table 1).

Methodology and Results

This section focuses on the analysis of our hypotheses discussed in the prior section. We used regression analysis to measure the impact of our variables of interest, customer orientation, customer interaction and market orientation on CSR. We run three different regressions to explore the relation of each variable to CSR. In each regression, we include the control variables of industry, size, customer categories, and market intensity.

\(Index_{f}\) is the CSR index level for each firm f in the sample.

\(CO_{f}\) is the level of customer orientation for firm f in the sample.

\(CI_{f}\) is the level of customer Interaction for firm f in the sample.

\(MO_{f}\) is the level of market orientation for firm f in the sample.

\(Controls_{f}\) include \(Industry_{f}\), the general industry coding,\(Size_{f}\), the size, \(B2C_{f} , B2B_{f} , B2G_{f}\), customer categories and \(MI_{f} ,\) the market intensity of firm f in the sample.

Given that some of our variables are highly correlated, we test for the presence of multicollinearity in our models by inspecting the variance inflation factors (VIF). None of the VIFs are greater than 5 and multicollinearity is not a concern as they far below the common cut-off threshold of 5–10 (Kleinbaum et al. 1998). We also test for normality and the Jarque–Bera test statistics show that our sample data comes from a normal distribution (Mardia 1970; Thadewald and Buning 2007). Finally we implement Newey-West Correction to all our models and report only heteroskedasticity consistent estimates of the standard errors (Newey and West 1987).

For all three hypothesis (see Table 2), we controlled for industry affiliation, firm size, customer categories and market intensity. Hypothesis one (H1) states customer orientation (CO) is positively related to CSR, which we found significant (F = 7.767; p = 0.001). Hence, the more customer oriented the firm is, the higher a firm will rank on the CSR Index. This empirical result suggests that since the current marketplace has an emphasis on CSR, CO focused firms will also determine the current needs of the consumer and have a strong CSR program. Hypothesis two states customer Interaction (CI) is positively related to CSR and was found to be insignificant (F = 1.248; p = 0.288). The results suggest that an action oriented component of MO where meetings, coordinated interactions, and conversations are instigated by the firm with the customer to ascertain market knowledge and relationship development is not required for CSR. Hypothesis three states market orientation (MO) is positively related to CSR and was found significant (F = 4.299; p = 0.001). The MO variable is broader and more future focused, as it attempts to predict trends and new value latent propositions for old customers while attempting to attract new customers, with CSR as a critical component.

Hypothesis four states CSR is positively related to Firm Performance and was found significant (F-stat = 2.625; p = 0.05) (see Table 3 which includes firm controls of industry affiliation, firm size, customer categories and market intensity). The results suggest that these firms’ level of financial performance is improved by their CSR efforts. As CSR is a customer focused tactic, firms with strong CSR are rewarded for their efforts by higher performance from customers.

Mediation Analysis

In this section we seek to determine whether CSR acts as a mediator between CI, CO and MO and financial performance. The path diagram is illustrated in Fig. 1. We did not run mediation tests for Hypothesis 4B which states that CSR will mediate the relationship between CI and financial performance. Hypothesis 2 was found insignificant and that CI is not positively correlated to CSR.

To further test H4a and H4c, we employed Preacher and Hayes’s (2004, 2008) INDIRECT macro for SPSS. Preacher and Hayes’s non-parametric resampling procedures for testing mediated moderation hypotheses generate bootstrap confidence intervals. Bootstrapping is a preferred method for testing mediation because it does not rely on the assumption of normality of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect (Preacher and Hayes 2004, 2008). As none of the confidence intervals produced contained zero, bootstrapping results showed that Customer Orientation (95 % CI 0.0262 to 0.2344) and Market Orientation (95 % CI 0.0541 to 0.4251) were meditated by CSR to performance. Further, for both independent variables the paths “a”, “b”, and “c” were significant, while “c-prime” is insignificant, suggesting a mediation effect. The model summary F-statistic for Customer Orientation was 11.970 (p > 0.001) and for Market Orientation the F-statistic was 13.079 (p > 0.001). Therefore, the data support H4a and H4c. See Table 4.

Conclusions and Implications

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has become of great interest to both researchers and practitioners alike with much discussion on whether the costs outweigh the performance implications. CSR has become a firm strategic tool (not only an ethical concept) as firms recognize that the customer value proposition and CSR is integrated with the focus on how to differentiate the firm from the view of the customer. We utilized market orientation (MO) theory as our foundation for our research as it explains how organizations adapt to their customer environment and focus on serving customers to develop competitive advantages. MO is both proactive and reactive with a focus on the current customer and an estimation of their needs in the future. With the current customer focus on CSR, MO assists the field in identifying a possible firm differentiation for success.

The market orientation (MO) theory is a business philosophy or a policy statement which addresses how organizations adapt to their customer environment and focus on serving customers to develop competitive advantages. MO-related competitive advantages can arise from closer customer ties or increased customer loyalty which is crucial in an ever-changing business environment. Customers are now focusing on the environment and are more socially conscious and have relayed these feelings to the marketplace. Firms are now implementing CSR programs in response to customers’ demands to differentiate themselves from their competitors, to maintain current customers, and to attract new ones.

We used CSR as a mediator in our model with MO as our theoretical foundation. MO and CSR both have had mixed results in the past in regard to their correlation to performance. The MO research stream primarily utilized in the marketing field has suggested that perhaps the relationship is either moderated or mediated to performance. We included CSR as the mediating variable to further the literature streams and our results indicate that CSR could be one of the mediating variables in today’s marketplace that MO-oriented firms need to consider in regard to firm performance.

CSR has now become a focus for most firms and customers in today’s marketplace with Fortune 500 firms including a section in their annual report on the topic, and being rated by independent firms of their CSR performance. The MO research literature suggests that MO is proactive and responsive to customers. That CSR is a mediator to MO/performance suggests that CSR is a proactive opportunity to meet customers’ needs, and reactive if the industry has already adopted CSR. Firms that do not focus on their customers and are not responsive to the current market trend of implementing CSR, will have worse performance. Our results indicate that CSR as a mediator is an important gateway to performance between CO and MO.

Managerial Implications

Our research assists the practitioners as a large portion of executives do not have enough knowledge of CSR to either implement or have a developed action plan. Our theoretical foundation suggests that firms can create mutual value with their customers by understanding customers’ current and future needs. CSR programs that are strategically aligned with overall firm level objectives should create competitive advantage for a firm.

Many practitioners still are reluctant to implement CSR due to the potential impact on firm performance. Our research suggests contrarily, that CSR will increase firm performance. Other previous research has suggested CSR will decrease employee turnover and employee commitment to work, as these findings together should assist to assuage top executives fears of implementing CSR.

From our theoretical foundation of market orientation theory we identified three key constructs that were found significant in previous research to firm performance: Customer orientation (CO), customer Interaction (CI) and market orientation (MO). MO is a customer-centric approach and the customer should be viewed as a co-creator of value in the relationship. The CO component of our research is more focused in line with service dominant logic of MO, where current customers’ needs and wishes are identified for further augmentation. The CI component of our research is an action oriented component of MO where meetings, coordinated interactions, and conversations are instigated by the firm with the customer to ascertain market knowledge and relationship development. The MO variable is broader and more future focused than the CO focus and relies less on direct CI, as it attempts to predict trends and new value latent propositions for old customers while attempting to attract new customers.

For managers we have at least two strong recommendations in regard to CSR. CSR mediates both CO and MO variables to performance suggesting MO-focused firms should also include a focus on CSR. CO requires firms to determine the current needs of the consumer through market information, with CSR as the current major demand by customers. Market information comes from a variety of sources, and target markets are also varied, but in general, research into CSR has effectively identified broad areas that firms may focus, i.e. environment, human rights, and corporate governance. Firms may wish to be proactive as the current marketplace has an emphasis on CSR, and firms that include programs to address these areas before competitors could gain a first mover advantage. Inclusion of CSR programs will positively affect firm performance, so managers must overcome the fear of the cost.

A second key recommendation is that the market orientation (MO) variable is broader and more future focused than CO as it attempts to predict trends, include a focus on competition and their strategic moves, and the development of strategic tactics for future products/services. Currently, CSR is generally used as a tactic by most firms in the marketplace, and as such those firms that ignore this trend will find their performance less than those implementing CSR. Similar to brand image, CSR is considered a long-term tactic and CSR can be a strategic tool instead of only being an ethical concept. CSR needs to be a business function, a strategic marketing component of central importance to firm level success, and a vital part of a firm’s marketing strategy.

Future Research

One of the major issues repeated throughout CSR research is the lack of distinct CSR measures. Future measures need to be developed to assess the level of CSR among a sample of firms regardless if they are present on the same Index or not. Comparability among indices, as well as over time, will assist researchers. This measure would aid in comparative, global, and cross cultural research. Other measures to enable measurements of specific CSR initiatives or portfolios of CSR efforts at the firm level could be goals of future research. The variable CSR has lacked a strong definition in the research and in practice and continues to change over time. This may be a phenomena that may not change, as social norms are always evolving as well.

Limitations of the Research

As with all research, there are limitations to this research. Some limitations of our research are that we used a one country sample, our research used data covering one fiscal year, and how CSR was measured. One of the limitations regarding using one country was the difficulties in locating and gaining access to a representative index suitable for our CSR research context. This is frequently voiced as a common problem in CSR research. Hence generalizability to all countries is in question.

Another limitation is whether varying ownership structures potentially affect CSR and firm performance, for example the level of institutional ownership. In this aspect Sweden is considered to have high levels of institutional ownership where approximately 63 % of the listed companies traded on the OMX-Stockholm stock exchange have institutional shareholders as larger shareholders or being majority owner (Jakobson 2012).

Other country level limitations regard differences in national culture. The relationship between market orientation and performance (or between customer satisfaction and performance) is claimed to be stronger in cultures with low power-distance and low uncertainty-avoidance. In this aspect, Sweden is ranked among the top ten for lowest power distance and among the top five for lowest uncertainty avoidance. Since these cultural aspects potentially affect for example, customer satisfaction or contributes to firm level enactment of voluntary CSR initiatives, a research extension toward other countries would benefit practitioner and academics understanding of voluntary CSR.

Summary

From the market orientation theoretical perspective firms that ranked high on CSR should have better performance which our results indicate. The results for CSR have been contradictory in the past, but recent research seems to see a movement toward CSR and greater performance, perhaps due to the global nature of the marketplace, importance of branding in this type of global marketplace, and the availability of copious and instant knowledge to consumers. Also past research suggests that the correlation, similar to the MO research, is from CSR to performance, although there may be a virtuous circle.

Some past research has suggested mixed results of CO, CI, and MO to higher firm performance. To assist in explaining these mixed results, our research explores a CSR mediation effect. Our research suggests that CSR provides a mediation of both CO and MO to performance. Perhaps the past MO research on these variables is confounded by the lack of a mediation variable such as CSR. As the new emphasis is on CSR, firms will be required to have many competencies and CSR will be a key component.

The results from our empirical study suggest that firms with a customer orientation (CO) employing CSR will have higher performance. The customer orientation seeks to focus on current customer needs, preferences and to provide them the appropriate service or product. CSR will enhance customer relationships and build brand value through differentiation. Our research also found significance with market orientation and CSR to performance. The market orientation is more of market scanning than customer orientation by focusing on market changes and competitor moves to ascertain the changing value proposition of the entire market.

Market oriented firms focus on developing competitive advantages within the whole marketplace and CSR enables this, especially in light of the global marketplace where product changes may come quickly. A large number of firms are implementing CSR with the knowledge that current and future customers will identify their brand favorably. We did not find significance for customer interaction and CSR, although customer interaction would be a normal occurrence for firms with either a customer orientation or market orientation.

The strategy and management field often discount primary data in regard to firm performance from managers due to hubris, self-report bias, etc. We were able to triangulate the firms’ top managers’ primary data responses (82 % response rate) to publicly traded financial statements and found that they had responded accurately as to their performance. Our research strengthens the argument that managers can, and will, correctly respond to questionnaires in regard to their firm performance.

References

Agarwal, S., Erramilli, M., & Dev, C. (2003). Market orientation and performance in service firms: Role of innovation. Journal of Services Marketing, 17(1), 68–82.

Alhakimi, W., & Baharun, R. (2010). An integrative model of market orientation constructs in consumer goods industry: An empirical evidence. International Management Review, 6(2), 40–54.

Appiah-Adu, K., & Singh, S. (1998). Customer orientation and performance: A study of SMEs. (small and medium-sized businesses). Management Decision, 36(5–6), 385(310).

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–412.

Atuahene-Gima, K., & Ko, A. (2001). An empirical investigation of the effect of market orientation and entrepreneurship orientation alignment on product innovation. Organization Science, 12(1), 54–74.

Augusto, M., & Coelho, F. (2009). Market orientation and new-to-the-world products: Exploring the moderating effects of innovativeness, competitive strength, and environmental forces. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(1), 94–108.

Aziz, N. A., & Yassin, N. M. (2010). How will market orientation and external environment influence the performance among SMEs in the agro-food sector in Malaysia?(Report). International Business Research, 3(3), 154(111).

Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736.

Barney, J. B., & Hansen, M. H. (1994). Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 175–190.

Baron, D. P. (1995). Integrated strategy—Market and nonmarket components. California Management Review, 37(2), 47–65.

Berkhout, T., & Rowlands, I. H. (2007). The voluntary adoption of green electricity by ontario-based companies: The importance of organizational values and organizational context. Organization Environment, 20(3), 281–303. doi:10.1177/1086026607306464.

Berry, L. (1983). Relationship marketing in emerging perspectives on servcies marketing. Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Berry, L., & Parasuraman, A. (1991). Marketing service. Competing through quality. New York: The Free Press.

Beverland, M., Farrelly, F., & Woodhatch, Z. (2004). The role of value change management in relationship dissolution: Hygiene and motivational factors. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(9–10), 927–939.

Bondy, K., Moon, J., & Matten, D. (2012). An Institution of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in multi-national corporations (MNCs): Form and implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–19. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1208-7.

Carroll, A. (2000). Ethical challenges for business in the new millennium: Coporate social responsibility and models of management morality. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(1), 33–42.

Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 85–105.

Chen, Y., Li, P., & Evans, K. (2012). Effects of interaction and entrepreneurial orientation on organizational performance: Insights into market driven and market driving. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(6), 1019–1034.

Day, G. S. (1994). The capabilities of market-driven organizations. The Journal of Marketing, 58, 37–52.

Day, G. (1999). Misconceptions about market orientation. Journal of Market-Focused Management, 4(1), 5–16.

Day, G., & Moorman, C. (2013). Regaining customer relevance: The outside-in turnaround. Strategy & Leadership, 41(4), 17–23.

Day, G., & Wensley, R. (1983). Marketing theory with a strategic orientation. The Journal of Marketing, 47, 79–89.

Delmas, M. A., & Toffel, M. W. (2008). Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategic Management Journal, 29(10), 1027–1055.

Demirbag, M., Koh, C. L., Tatoglu, E., & Zaim, S. (2006). TQM and market orientation’s impact on SMEs’ performance. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 106(8), 1206–1228.

DeTienne, K., Agle, B., Phillips, J., & Ingerson, M.-C. (2012). The impact of moral stress compared to other stressors on employee fatigue, job satisfaction, and turnover: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1197-y.

Dickson, P. (1992). Toward a general theory of competitive rationality. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 69–83.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation—Concepts, evidence and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91.

Drucker, P. F. (1984). The new meaning of corporate social responsibility. California Management Review, 26, 53–63.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 8–19.

Eggert, A., Ulaga, W., & Schultz, F. (2006). Value creation in the relationship life cycle: A quasi-longitudinal analysis. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(1), 20–27.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Galunic, D. C. (2000). Coevolving: At last, a way to make synergies work. Harvard Business Review, 78, 91–101.

Ellis, P. D. (2010). Is market orientation affected by the size and diversity of customer networks? Management International Review, 50(3), 325(321).

Fombrun, C. J. (2000). Opportunity platforms and safety nets: Corporate citizenship and reputational risk. Business and Society Review, 105(1), 85.

Freeman, R. E. (Ed.). (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder perspective. Boston: Pitman.

Freeman, R. E., Wicks, A. C., & Parmar, B. (2004). Stakeholder theory and “The corporate objective revisited”. Organization Science, 15(3), 364–369.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits., New York Times Magazine, September 13.

Gadenne, D., Kennedy, J., & McKeiver, C. (2009). An empirical study of environmental awareness and practices in SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 45–63.

Gebhardt, G. F., Carpenter, G. S., & Sherry, J. F. (2006). Creating a market orientation: A longitudinal, multifirm, grounded analysis of cultural transformation. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 37–55.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the organization. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 108–122.

Groza, M. D., Pronschinske, M. R., & Walker, M. (2011). Perceived organizational motives and consumer responses to proactive and reactive CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(4), 639–652.

Gummesson, E. (2008). Extending the service-dominant logic: From customer centricity to balanced centricity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 15–17.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1994). Competing for the future: Breakthrough strategies for seizing control of your industry and creating the markets of tomorrow. Boston: Harvard business school press.

Han, J. K., Kim, N., & Srivastava, R. K. (1998). Market orientation and organizational performance: Is innovation a missing link? The Journal of marketing, 62, 30–45.

Harrison, J. S., Bosse, D. A., & Phillips, R. A. (2010). Managing for stakeholders, stakeholder utility functions, and competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 31(1), 58–74.

Heikkurinen, P. (2010). Image differentiation with corporate environmental responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 17, 142–152 Hill, Griffith, & Lim. (2008). Principles of econometrics (3rd edition ed.): Wiley & Sons.

Hill, R. P., Ainscough, T., Shank, T., & Manullang, D. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and socially responsible investing: A global perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 70, 165–174.

Hosmer, L. (1994). Strategic planning as if ethics mattered. Strategic Management Journal, 15(2), 17–34.

Hull, C. E., & Rothenberg, S. (2008). Firm performance: The interactions of corporate social performance with innovation and industry differentiation. Strategic Management Journal, 29(7), 781–789.

Hult, G. T. M., Kethcen, D. J., & Arrfelt, M. (2007). Strategic supply chain management: Improving performance through a culture of competitiveness and knowledge development. Strategic Management Journal, 28(10), 1035–1052.

Hur, W. M., Kim, H., & Woo, J. (2013). How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: Mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–12.

Hurley, R. F., & Hult, G. T. M. (1998). Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing, 62(3), 42–54.

Hyvönen, S., & Tuominen, M. (2007). Channel collaboration, market orientation and performance advantages: Discovering developed and emerging markets. International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, 17(5), 423–445. doi:10.1080/09593960701631482.

Jackson, K. T. (2004). Building Reputational Capital, Strategies for Integrity and Fair Play that Improve the Bottom Line. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jacobson, K. “Whose corporations? Our corporations!” Huffington Post, April 5, 2012 from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ken-jacobson/whose-corporations-our-co_b_1405832.html.

Kang, J. (2009). Corporate social responsibility? Not my business any more: The CEO horizon problem in corporate social performance. Academy of Management Perspectives, 2009, 1–6.

Kaplan, R and D. Norton. (1992) The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, January–February, 71 & 80.

Kirca, A. H., Jayachandran, S., & Bearden, W. O. (2005). Market orientation: A meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 24–41.

Kleinbaum, D. G., Kupper, L. L., & Muller, K. E. (1988). Applied regression analysis and other multivariate analysis methods. Boston: PWS-Kent Publishing Company.

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 1–18.

Kolk, A., & Pinske, J. (2006). Stakeholder mismanagement and corporate social responsibility crises. European Management Journal, 24(1), 59(14).

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (Eds.). (2005). Corporate social responsibility. Hoboken: Wiley.

KPMG. (2011). KPMG International survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2011. KPMG, 1(1).

Kumar, V., Jones, E., Venkatesan, R., & Leone, R. P. (2011). Is market orientation a source of sustainable competitive advantage or simply the cost of competing? Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 16–30.

Lam, S. K., Kraus, F., & Ahearne, M. (2010). The diffusion of market orientation throughout the organization: A social learning theory perspective. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 61–79.

Lee, S.-Y. (2008). Drivers for the participation of small and medium-sized suppliers in green supply chain initiatives (p. 3). Supply Chain Management: An International Journal.

Lev, B., Petrovits, C., & Radhakrishnan, S. (2011). Is doing good good for you? How corporate charitable contributions enhance revenue growth. Strategic Management Journal, 31(2), 182–200.

Liao, S.-H., Chang, W.-J., Wu, C.-C., & Katrichis, J. M. (2010). A survey of market orientation research (1995–2008). doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.09.003. Industrial Marketing Management, (in press), Corrected Proof.

Liao, S. H., Chang, W. J., Wu, C. C., & Katrichis, J. M. (2011). A survey of market orientation research (1995–2008). Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 301–310.

Liebeskind, J. P. (1996). Knowledge, strategy, and the theory of organization. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 93–107.

Lopez, M. V., Garcia, A., & Rodriguez, L. (2007). Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the dow jones sustainability index. Journal of Business Ethics, 75, 285–300.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2009). The debate over doing good: Corporate social performance, strategic marketing levers, and firm-idiosyncratic risk. Journal of Marketing, 73, 198–213.

Lusch, R., Vargo, S., & O’Brien, M. (2007). Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. Journal of Retailing, 83(1), 5–18.

Marcel, J. (2009). Why top management team characteristics matter when employing a chief operating officer: A strategic contingency perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 30(6), 647–658.

Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika, 57, 519–530.

McCulloch, J., & Huston, M. (1985). Miscellanea: On heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 53(2), 483.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2000). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 603–609.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 26, 117–127.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. S. (2011). Creating and capturing value. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1480–1495. doi:10.1177/0149206310385696.

Melo, T., & Garrido-Morgado, A. (2012). Corporate reputation: A combination of social responsibility and industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 19(1), 11–31. doi:10.1002/csr.260.

Menguc, B., & Auh, S. (2006). Creating a firm-level dynamic capability through capitalizing on market orientation and innovativeness. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(1), 63–73.

Miller, D. J. (2004). Firms’ technological resources and the performance effects of diversification: a longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 25(11), 1097–1119.

Moon, S.-G., & deLeon, P. (2007). Contexts and corporate voluntary environmental behaviors: Examining the EPA’s green lights voluntary program. Organization Environment, 20(4), 480–496. doi:10.1177/1086026607309395.

Moratis, L., & Cochius, T. (2011). What is social responsibility (according to ISO 26000)? ISO 26000: The business guide to the new standard on social responsibility, 9(26), 18.

Mulyanegara, R. C. (2010). Market orientation and brand orientation from customer perspective an empirical examination in the non-profit sector (Report). International Journal of Business and Management, 5(7), 14(10).

Murray, K. B., & Montanari, J. R. (1986). Strategic management of the socially responsible Firm: Integrating management and marketing theory. The Academy of Management Review, 11, 815–827.

Naffziger, D. W., Ahmed, N. U., & Montagno, R. V. (2003). Perceptions of environmental consciousness in U.S. small business: An empirical study. SAM Advanced Management Journal (07497075), 68(2), 23.

Narver, J., Slater, S., & MacLachlan, D. (2004). Responsive and proactive market orientation and new-product success. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21(5), 334–347.

Neilsen, E. H., & Rao, M. V. H. (1987). The strategy-legitimacy nexus: A thick description. The Academy of Management Review, 12(3), 523–533.

Newey, W. K., & West, K. D. (1987). A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica, 55(3), 703–708.

Nielsen, A. E., & Thomsen, C. (2010). Sustainable development: The role of network communication. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 9999(9999), n/a.

Noland, J., & Phillips, R. (2010). Stakeholder engagement, discourse ethics and strategic management. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 39–49.

Öberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B., & Gruber, V. (2011). Why don’t consumers care about CSR?: A qualitative study exploring the role of CSR in consumption decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(4), 449–460. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-0925-7.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies (01708406), 24(3), 403–441.

Oudan, T. (2012). Market orientation -transforming trade and firm performance. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 4(2), 3–8.

Palmer, A., & Bejou, D. (1994). Buyer-seller relationships: A conceptual model and empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing Management, 10(6), 495–512.

Peloza, J. (2006). Using corporate social responsibility as insurance for financial performance. Management Review, 48(2), 52–72.

Peloza, J., & Papania, L. (2008). The missing link between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Stakeholder salience and identification. Corporate Reputation Review, 11, 169–181.

Pinto, J., & Curto, J. (2007). The organizational configuration concept as a contribution to the performance explanation: The case of the pharmaceutical industry in Portugal. European Management Journal, 25(1), 60–78.

Porter, T. B. (2008). Managerial applications of corporate social responsibility and systems thinking for achieving sustainability outcomes. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 25(3), 397–411.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (Eds.). (2006). Strategy & Society. The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. (Vol. December): Harvard Business Review.

Ramani, G., & Kumar, V. (2008). Interaction orientation and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 72(1), 27–45.

Ramchander, S., Schwebach, R. G., & Staking, K. I. M. (2012). The informational relevance of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from DS400 index reconstitutions. Strategic Management Journal, 33(3), 303–314. doi:10.1002/smj.952.

Ruekert, R. W. (1992). Developing a market orientation: An organizational strategy perspective. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 9(3), 225–245. doi:10.1016/0167-8116(92)90019-H.

Sandvik, I., & Sandvik, K. (2003). The impact of market orientation on product innovativeness and business performance. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 20(4), 355–376.

Semenova, N., Hassel, L. G., & Nilsson, H. (2008). The Value Relevance of Environmental and Social Performance. Paper presented at the Global Conference on Business and Finance 2008, Costa Rica. http://www.pwc.com/sv_SE/se/hallbar-utveckling/assets/sammanfattning_six300.pdf.

Siegel, D. S., & Vitaliano, D. F. (2007). An empirical analysis of the strategic use of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Economics Management Strategy, 16(3), 773(720).