Abstract

Purpose

The prognostic role of primary tumor surgery in women with metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis is contentious. A subset of patients who will benefit from aggressive local treatment is needed to be identified. Using a nationwide database, we developed and validated a predictive model to identify long-term survivors among patients who had undergone primary tumor surgery.

Methods

A total of 150,043 patients were enrolled in the Korean Breast Cancer Registry between January 1990 and December 2014. Of these, 2332 (1.6%) presented with distant metastasis at diagnosis. Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we developed and validated a model that predicts survival in patients who undergo primary tumor surgery, based on the clinicopathological features of the primary tumor.

Results

A total of 2232 metastatic breast cancer patients were reviewed. Of these, 1541 (69.0%) patients had undergone primary tumor surgery. The 3-year survival rate was 62.6% in this subgroup. Among these patients, advanced T-stage, high-grade tumor, lymphovascular invasion, negative estrogen receptor status, high Ki-67 expression, and abnormal CA 15-3 and alkaline phosphatase levels were associated with poor survival. A prediction model was developed based on these factors, which successfully identified patients with remarkable survival (score 0–3, 3-year survival rate 87.3%). The clinical significance of the model was also validated with an independent dataset.

Conclusions

We have developed a predictive model to identify long-term survivors among women who undergo primary tumor surgery. This model will provide guidance to patients and physicians when considering surgery as a treatment modality for metastatic breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Surgical treatment of the primary tumor is not usually recommended for women who present with metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis because the disease is already systemic. National cancer guidelines do not encourage surgical treatment, but only recommend consideration of surgery for local symptoms control after initial systemic treatment [1]. However, recent studies of the prognostic role of primary tumor surgery have suggested that local therapy may prolong survival [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The possibility of selection bias in these retrospective studies is a limitation that is not easily resolved.

Regardless of the possibility of selection bias, the positive results of numerous retrospective studies imply that there is probably a subset of patients who will benefit from surgery. This subset of patients can expect local treatment to have a positive effect, including local control, potential seed source removal, reduced tumor burden, and a possible immunomodulatory response [12, 13]. In long-term survivors, primary tumor surgery also has the advantage of preventing potential local complications of the breast tumor. However, surgical complications can occur, threatening a patient’s quality of life and delaying systemic therapy, the primary therapeutic modality. The possibility of accelerated metastatic lesion growth after the removal of the primary tumor is also a concern.

To clarify the role of primary tumor surgery in metastatic breast cancer, several randomized controlled trials are ongoing [14,15,16,17,18]. Recently, two of these studies presented survival analysis results, but with conflicting ones [15, 17, 19]. In a trial in India, Badwe et al. demonstrated no survival benefit of primary tumor surgery after systemic therapy, including in all subgroups [15], whereas in a Turkish trial, an increase of 9 months in median overall survival was shown in the surgically treated group [19]. However, the lack of stratification factors resulted in potential imbalance between the two groups. These conflicting results bring along doubt that it is possible to define the role of surgery in metastatic breast cancer. Moreover, the heterogeneous biology of breast cancer implies that the role of local therapy cannot be universally defined, and a randomized controlled trial is limited in its ability to distinguish the subset of patients who might benefit from local therapy. In this regard, we undertook to identify the characteristics of long-term survivors among patients who underwent primary tumor surgery.

In this study, we compared the clinicopathological features and survival outcomes after primary tumor surgery of patients with metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis, using the Korean Breast Cancer Registry (KBCR) cohort data. Our ultimate aim was to develop a model that predicts survival in patients who undergo primary tumor surgery, to identify potential long-term survivors who might benefit from local treatment.

Methods

Korean Breast Cancer Registry

The KBCR is a prospectively maintained, web-based database of the Korean Breast Cancer Society [20,21,22]. Breast surgeons from >100 teaching hospitals throughout the Republic of Korea voluntarily participated in this program. The registry is estimated to include >65% of all newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in Korea in 2013 [23]. Patients’ sex, age, surgical method, and cancer stage (based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification) are collected as essential items. Pathological findings, laboratory, and imaging findings, and treatment modality are optional factors. Survival data were obtained from the Korean Central Cancer Registry, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea, and were recently updated on December 31, 2014. The KBCR does not provide data on the metastatic sites in stage IV patients.

Study cohort

This study includes all the patients with metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis enrolled in the KBCR between January 1990 and December 2014. During this period, 150,043 patients were enrolled and 2332 (1.6%) presented with distant metastasis at diagnosis. Patients with a previous history of breast cancer, a diagnosis of phyllodes tumor or sarcoma, or who had undergone the excision of a metastatic lesion were excluded. After exclusion, 2232 patients were reviewed for the study. The total study cohort was divided into three groups according to the type of primary tumor surgery undertaken: surgery group, non-surgery group, and partial surgery group. The partial surgery group consisted of patients who had undergone only breast or only axilla surgery, with no definite surgery of the primary tumor. In the surgery group, the patients were randomly divided into two cohorts, in a ratio of 2:1, for the development and validation of the survival prediction scoring system, respectively.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB number: KC16RISI0837) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of each group, established according to the primary tumor surgery, were compared using χ2 tests and t tests. The survival analysis was performed with the Kaplan–Meier method and the groups were compared using the log-rank test. A multivariate analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazards ratio model to estimate the adjusted hazards ratio for each factor. The primary endpoint was overall survival, defined as the time from the first diagnosis of breast cancer to death from any cause, which was censored at December 31, 2014. All analyses were performed with SPSS (version 24.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was assumed at p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 2232 patients with metastatic breast cancer were reviewed. Among them, 1541 (69.0%) patients had undergone primary tumor surgery (surgery group), 588 (26.3%) patients had not undergone any surgery (non-surgery group), and 103 (4.6%) patients had undergone only breast or only axilla surgery (partial surgery group). A comparison of the clinicopathological features of each group is shown in Table 1. Age did not differ between the three groups. Smaller tumor, less axillary nodal involvement, lower grade, and ductal carcinoma correlated with primary tumor surgery. Patients with low-Ki-67 tumors were more likely to undergo surgery, whereas estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) status were not associated with surgery. Patients with clinical factors suggesting a lower tumor burden, such as asymptomatic disease, normal tumor marker levels (CEA and CA15-3), and normal alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels, were also more likely to undergo surgery.

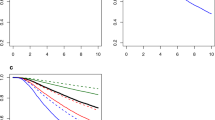

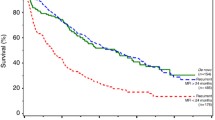

Survival by time and receipt of surgery

The 3-year survival rate for the entire cohort was 56.4%, with a median survival of 44 months. The survival trend changed significantly over the 24-year period, with a substantial improvement in overall survival (Fig. 1a). The 3-year survival rate increased from 38.7% in the 1990s to 50.5% in 2000–2004, 57.3% in 2005–2009, and 70.1% in patients diagnosed during 2010–2014. This trend was identified in both the surgery and non-surgery groups (Fig. 1b, c).

When comparing by receipt of surgery, patients who underwent primary tumor surgery had significantly improved survival, with a median survival of 53 months, compared to the non-surgery group (31 months; log-rank test p < 0.001). However, the survival of patients who did not undergo definite surgery (partial surgery group, median survival of 37 months) did not differ from that of the non-surgery group (log-rank test p = 0.113) (Fig. 2).

Prediction of long-term survivors in the surgery group

To develop a survival prediction scoring system, the surgery group was randomly divided into discovery and validation cohorts (ratio 2:1). The characteristics of each cohort are described in Supplementary Material (eTable 1), and did not differ significantly. A univariate analysis and multivariate analysis of the discovery cohort were performed to identify the prognostic factors affecting overall survival (Table 2). Advanced T-stage, high-grade tumor, lymphovascular invasion, ER negativity, high or unknown Ki-67 expression, abnormal ALP level, and abnormal or unknown CA15-3 level were significantly associated with poor prognosis in the multivariate analysis.

A scoring system was developed based on the hazard ratios to estimate the likelihood of long-term survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer who undergo primary tumor surgery (Fig. 3a). The surgery survival scores ranged from 0 to 10, and patients were categorized into four groups by their scores. Different survival outcomes were clearly separated by these four groups (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3b). The 3-year survival rates of the groups were 87.3% (scores 0–3), 68.4% (scores 4–5), 48.2% (scores 6–7), and 35.3% (scores 8–10). The patients with scores of 0–3 showed significantly better 3-year survival compared to the whole surgery group (p < 0.001).

The scoring system was applied to the validation cohort to investigate its clinical usefulness. As shown in Fig. 3c, the scoring system successfully divided patient survival according to the four groups, showing significantly better survival in the group with scores of 0–3 (3-year survival rate, 85.9%).

Discussion

Although practice guidelines do not recommend primary tumor surgery for patients with metastatic breast cancer, many retrospective studies have demonstrated improved survival among patients who undergo surgery [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, 24,25,26,27]. This study also presented with similar results, however with substantial selection bias. The possibility of selection bias has not been easily resolved by statistical adjustment methods in previous studies. Therefore, to clarify this issue, several randomized controlled trials are in progress [14,15,16,17,18], but the recent conflicting results of two of these trials [15, 19] have failed to ease this controversy.

The influence of selection bias on patient survival in previous studies demonstrates the possibility that a subgroup of patients will benefit from local treatment. Metastatic breast cancer is a very heterogeneous disease and survival depends on various factors, including tumor subtype, metastatic site, and numbers of and responses to systemic treatments. It may not be possible to define the role of surgery uniformly in all patients with metastatic breast cancer, but a subset of long-term survivors who might benefit from surgery should be identifiable. However, randomized controlled trials are limited in identifying these potential long-term survivors. Within this context, we retrospectively reviewed a nationwide database to construct and validate a predictive model that can identify long-term survivors among metastatic breast cancer patients who undergo surgery. Primary tumor characteristics, such as tumor size, grade, lymphovascular invasion, ER status, Ki-67 level, and tumor marker levels at diagnosis, were related to patient survival. A predictive model was developed using these factors, which identified a subgroup (scores of 0–3) with a significantly longer 3-year survival rate (>85%) compared to that of the total surgery group (62.6%).

More metastatic breast cancer patients are expected to have prolonged survival, as patient survival improves by time. This trend has been demonstrated in this study and other nationwide studies too [7, 8, 28]. The increase in survival over time is the result of advances in treatment modalities and in modern imaging techniques. The development of targeted therapies has increased the survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer [29, 30], and hormone-receptor-positive and HER2-positive tumors are expected to benefit most from these advances. With the progress in imaging techniques, the profiles of metastatic breast cancer are also evolving. Smaller metastatic lesions are being identified earlier, greatly reducing the tumor burden at diagnosis compared to that in earlier years. These recent changes in the spectrum of metastatic breast cancer emphasize the need to identify potential long-term survivors.

Patient selection is a requirement noted in much of the literature [24, 27, 31] and efforts to identify appropriate surgical candidates have been reported. Our predictive model, which identifies long-term survivors, is mainly based on the clinicopathological features of the primary tumor, which are well-recognized prognostic factors in metastatic breast cancer [6]. Soran et al. described the pattern of distant metastasis as a selection factor in the Turkish study, suggesting that patients with a solitary bone metastasis benefited from complete excision of the primary tumor [17]. In a prospective registry study, King et al. also demonstrated the prognostic value of a 21-gene recurrence score in ER-positive, HER2-negative stage IV breast cancer [32], introducing a role for genomic diagnostic tools in the treatment of advanced breast cancer.

There are some limitations of this study. The KBCR does not record variables such as tumor burden, timing of diagnosis of metastasis, comorbidities, and response to systemic treatment. Moreover, because of the retrospective and voluntary nature of the KBCR, a large portion of data was missing, especially in the non-surgery group. The KBCR is primarily maintained by breast surgeons nationwide, and compared with other retrospective studies, the proportion of patients not undergoing surgery in this study was relatively small, causing further potential selection bias.

However, this study has several strengths. Previous studies mainly focused on the prognostic role of local treatment, whereas in this study, we concentrated on identifying long-term survivors, to identify those patients who could be considered for primary tumor surgery. Moreover, the predictive model constructed in this study is simple and easily applicable in the clinical context. Also, the KBCR is a prospectively maintained nationwide database with a high enrollment rate (over 65%) and is representative of all women with a diagnosis of breast cancer in Korea.

In conclusion, we have developed and validated a predictive model to identify long-term survivors among women who undergo primary tumor surgery. The paradigm of metastatic breast cancer is gradually shifting from a terminal event to a chronic disease, which anticipates an increasing role for surgery. This predictive model provides insight into the prognostic value of primary tumor surgery in individual patients and guidance to patients and physicians considering the option of primary tumor surgery.

References

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) (2016) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer. http://www.nccn.org website. Accessed 31 Aug 2016

Blanchard DK, Shetty PB, Hilsenbeck SG, Elledge RM (2008) Association of surgery with improved survival in stage IV breast cancer patients. Ann Surg 247(5):732–738. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656d32

Gnerlich J, Jeffe DB, Deshpande AD, Beers C, Zander C, Margenthaler JA (2007) Surgical removal of the primary tumor increases overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: analysis of the 1988–2003 SEER data. Ann Surg Oncol 14(8):2187–2194. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9438-0

Olson JA Jr, Marcom PK (2008) Benefit or bias? The role of surgery to remove the primary tumor in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Surg 247(5):739–740. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181706140

Perez-Fidalgo JA, Pimentel P, Caballero A et al (2011) Removal of primary tumor improves survival in metastatic breast cancer. Does timing of surgery influence outcomes? Breast 20(6):548–554. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2011.06.005

Rashaan ZM, Bastiaannet E, Portielje JE et al (2012) Surgery in metastatic breast cancer: patients with a favorable profile seem to have the most benefit from surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 38(1):52–56. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2011.10.004

Thomas A, Khan SA, Chrischilles EA, Schroeder MC (2016) Initial surgery and survival in stage IV breast cancer in the United States, 1988–2011. JAMA Surg 151(5):424–431. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4539

Warschkow R, Guller U, Tarantino I et al (2016) Improved survival after primary tumor surgery in metastatic breast cancer: a propensity-adjusted, population-based SEER trend analysis. Ann Surg 263(6):1188–1198. doi:10.1097/sla.0000000000001302

Babiera GV, Rao R, Feng L et al (2006) Effect of primary tumor extirpation in breast cancer patients who present with stage IV disease and an intact primary tumor. Ann Surg Oncol 13(6):776–782. doi:10.1245/aso.2006.03.033

Bafford AC, Burstein HJ, Barkley CR et al (2009) Breast surgery in stage IV breast cancer: impact of staging and patient selection on overall survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat 115(1):7–12. doi:10.1007/s10549-008-0101-7

Neuman HB, Morrogh M, Gonen M, Van Zee KJ, Morrow M, King TA (2010) Stage IV breast cancer in the era of targeted therapy: does surgery of the primary tumor matter? Cancer 116(5):1226–1233. doi:10.1002/cncr.24873

Danna EA, Sinha P, Gilbert M, Clements VK, Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S (2004) Surgical removal of primary tumor reverses tumor-induced immunosuppression despite the presence of metastatic disease. Cancer Res 64(6):2205–2211

Norton L, Massague J (2006) Is cancer a disease of self-seeding? Nat Med 12(8):875–878. doi:10.1038/nm0806-875

Ruiterkamp J, Voogd AC, Tjan-Heijnen VC et al (2012) Systemic therapy with or without up front surgery of the primary tumor in breast cancer patients with distant metastases at initial presentation. BMC Surg 12:5. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-12-5

Badwe R, Hawaldar R, Nair N et al (2015) Locoregional treatment versus no treatment of the primary tumour in metastatic breast cancer: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 16(13):1380–1388. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00135-7

Shien T, Nakamura K, Shibata T et al (2012) A randomized controlled trial comparing primary tumour resection plus systemic therapy with systemic therapy alone in metastatic breast cancer (PRIM-BC): Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG1017. Jpn J Clin Oncol 42(10):970–973. doi:10.1093/jjco/hys120

Soran A, Ozmen V, Ozbas S et al (2013) Abstract S2–03: early follow up of a randomized trial evaluating resection of the primary breast tumor in women presenting with de novo stage IV breast cancer; Turkish study (protocol MF07-01). Cancer Res 73(24 Supplement):S2–03. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.sabcs13-s2-03

Mittendorf EA (2010) Early surgery or standard palliative therapy in treating patients with stage IV breast cancer (ECOG 2108). NCT01242800

Soran A, Ozbas S, Karanlik H et al (2016) A randomized controlled trial evaluating resection of the primary breast tumor in women presenting with de novo stage IV breast cancer: Turkish Study (Protocol MF07-01). J Clin Oncol 34:suppl; abstr 1005

Moon HG, Han W, Noh DY (2009) Underweight and breast cancer recurrence and death: a report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. J Clin Oncol 27(35):5899–5905. doi:10.1200/jco.2009.22.4436

Moon HG, Han W, Noh DY (2010) Comparable survival between pN0 breast cancer patients undergoing sentinel node biopsy and extensive axillary dissection: a report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. J Clin Oncol 28(10):1692–1699. doi:10.1200/jco.2009.25.9226

You JM, Kim YG, Moon HG et al (2015) Survival improvement in Korean Breast Cancer patients due to increases in early-stage cancers and hormone receptor positive/HER2 negative subtypes: a Nationwide Registry-Based Study. J Breast Cancer 18(1):8–15. doi:10.4048/jbc.2015.18.1.8

Min SY, Kim Z, Hur MH, Yoon CS, Park EH, Jung KW (2016) The basic facts of Korean Breast Cancer in 2013: results of a Nationwide Survey and Breast Cancer Registry Database. J Breast Cancer 19(1):1–7. doi:10.4048/jbc.2016.19.1.1

Criscitiello C, Giuliano M, Curigliano G et al (2015) Surgery of the primary tumor in de novo metastatic breast cancer: to do or not to do? Eur J Surg Oncol 41(10):1288–1292. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.013

Pathy NB, Verkooijen HM, Taib NA, Hartman M, Yip CH (2011) Impact of breast surgery on survival in women presenting with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Surg 98(11):1566–1572. doi:10.1002/bjs.7650

Petrelli F, Barni S (2012) Surgery of primary tumors in stage IV breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis of published studies with meta-regression. Med Oncol 29(5):3282–3290. doi:10.1007/s12032-012-0310-0

Harris E, Barry M, Kell MR (2013) Meta-analysis to determine if surgical resection of the primary tumour in the setting of stage IV breast cancer impacts on survival. Ann Surg Oncol 20(9):2828–2834. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-2998-2

Andre F, Slimane K, Bachelot T et al (2004) Breast cancer with synchronous metastases: trends in survival during a 14-year period. J Clin Oncol 22(16):3302–3308. doi:10.1200/jco.2004.08.095

Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I et al (2015) The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 16(1):25–35. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(14)71159-3

Swain SM, Kim SB, Cortes J et al (2013) Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA study): overall survival results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 14(6):461–471. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70130-x

Patrick J, Khan SA (2015) Surgical management of de novo stage IV breast cancer. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 13(4):487–493 (quiz 493)

King TA, Lyman JP, Gonen M et al (2016) Prognostic impact of 21-gene recurrence score in patients with stage IV breast cancer: TBCRC 013. J Clin Oncol 34(20):2359–2365. doi:10.1200/jco.2015.63.1960

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Korean Breast Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, TK., Chae, B.J., Kim, S.J. et al. Identifying long-term survivors among metastatic breast cancer patients undergoing primary tumor surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 165, 109–118 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4309-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4309-2