Abstract

We evaluated individual grain-containing foods and whole and refined grain intake during adolescence, early adulthood, and premenopausal years in relation to breast cancer risk in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Grain-containing food intakes were reported on a baseline dietary questionnaire (1991) and every 4 years thereafter. Among 90,516 premenopausal women aged 27–44 years, we prospectively identified 3235 invasive breast cancer cases during follow-up to 2013. 44,263 women reported their diet during high school, and from 1998 to 2013, 1347 breast cancer cases were identified among these women. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate relative risks (RR) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) of breast cancer for individual, whole and refined grain foods. After adjusting for known breast cancer risk factors, adult intake of whole grain foods was associated with lower premenopausal breast cancer risk (highest vs. lowest quintile: RR 0.82; 95 % CI 0.70–0.97; P trend = 0.03), but not postmenopausal breast cancer. This association was no longer significant after further adjustment for fiber intake. The average of adolescent and early adulthood whole grain food intake was suggestively associated with lower premenopausal breast cancer risk (highest vs lowest quintile: RR 0.74; 95 % CI 0.56–0.99; P trend = 0.09). Total refined grain food intake was not associated with risk of breast cancer. Most individual grain-containing foods were not associated with breast cancer risk. The exceptions were adult brown rice which was associated with lower risk of overall and premenopausal breast cancer (for each 2 servings/week: RR 0.94; 95 % CI 0.89–0.99 and RR 0.91; 95 % CI 0.85–0.99, respectively) and adult white bread intake which was associated with increased overall breast cancer risk (for each 2 servings/week: RR 1.02; 95 % CI 1.01–1.04), as well as breast cancer before and after menopause. Further, pasta intake was inversely associated with overall breast cancer risk. Our results suggest that high whole grain food intake may be associated with lower breast cancer risk before menopause. Fiber in whole grain foods may mediate the association with whole grains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States [1]. The potential influence of dietary factors on breast cancer development has received considerable attention, because identification of potentially modifiable risk factors could contribute to the prevention of breast cancer. Grains are major components of the diet and contribute to daily intake of carbohydrate, protein, and dietary fiber [2]. Whole grains, in addition to fiber, contain many important nutrients that may influence breast cancer risk. While epidemiological evidence supports a protective effect of whole grain intake against type 2 diabetes [3, 4], cardiovascular diseases [4], and some cancers [5], the relation between whole grain food intake and breast cancer has been examined in only a few studies [6–8] and also no clear association has so far been observed. However, these studies generally evaluated grain intake during midlife and later. Studies of women who survived the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or who underwent radiation treatment for lymphoma, provide evidence that carcinogenic exposures in early life may be critical in subsequent breast cancer risk [9–11]. Consistent with this, in our previous work in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), high intake of fiber during adolescence and early adulthood was associated with lower risk of breast cancer [12]. Further, different grains may not equally be related to risk of breast cancer and an understanding of the role of each grain in breast carcinogenesis is needed. NHSII is a prospective cohort study in which we could evaluate the importance of timing of grain consumption, given the large sample size and validated data on dietary intake, as well as information on lifestyle and breast cancer risk factors during both adolescent and adult life.

The overall goal of this analysis was to investigate the intake of whole grain and refined grain foods as well as individual grain-containing foods during adolescence, early adulthood, and premenopausal periods in relation to subsequent risk of pre- and postmenopausal breast cancer in the NHSII. The analyses also included consideration of tumor hormone receptor status.

Subjects and methods

Study population

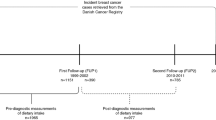

The NHSII was established in 1989 with a total enrollment of 116,430 female registered nurses aged 25–42 years. Our analyses included women who returned the 1991 self-reported food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (n = 97,813). We excluded participants with excess of total energy intake (<600 or >3500 kcal/day); more than 70 food items left blank in the FFQ; postmenopausal status in 1991 and missing information on age, or with a diagnosis of cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer) in 1991 or before. The primary analyses included 90,516 women. The follow-up rate was 96 % of total potential person-years from 1991 to 2013.

In 1997, participants were asked about their willingness to complete a supplemental FFQ about diet during high school (HS-FFQ). Among the 47,355 women who returned the HS-FFQ in 1998, we excluded women if they had cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer) before 1998, extreme total energy intake (<600 or ≥5000 kcal), or more than 70 food items left blank in the HS-FFQ. Thus, the adolescent diet analyses included 44,263 women. The follow-up rate exceeded 98 % of total potential person-years from 1998 to 2013.

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Boston, MA, United States).

Dietary assessment

In 1991 and every 4 years thereafter, validated semi-quantitative FFQs with approximately 130 items were sent to participants to report their usual dietary intake during the past year (available at http://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/participants/questionnaires). We asked women how often they consumed grain foods in nine categories ranging from “never or less than once per month” to “six or more times per day.” Whole and refined grain foods listed on the FFQ are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Validity of repeated questionnaires to measure long-term dietary intake was examined by comparison with multiple diet records collected over a 6-year period; the average de-attenuated correlation for dietary nutrient intakes was 0.83 [13]. Further, increased whole grain food intake assessed by this questionnaire has inversely been associated with risks of total mortality [14] and type 2 diabetes [15], indirectly supporting the validity of the FFQ.

Adolescent diet was evaluated using a 124-item FFQ that included foods usually consumed between 1960 and 1980 when participants were in high school (HS-FFQ, see Supplemental Table S2). Among 80 young women, the validity of the HS-FFQ was assessed. Women completed three 24-h dietary recalls and two FFQ during high school with the HS-FFQ administered over a period of 10 years; the mean of corrected correlation coefficients for energy-adjusted nutrient intakes was 0.45 for the HS-FFQ and the earlier 24-h dietary recalls and 0.58 for the HS-FFQ and the earlier FFQ’s [16]. The evidence of validity also came from comparisons of high school diet reported by 272 of NHSII participants with their high school diet reported by their mothers using the HS-FFQ; the mean correlation for nutrients was 0.40 [17].

Assessment of breast cancer cases

In the biennial follow-up questionnaires, participants reported diagnosis of breast cancer and the date of diagnosis. When a case of breast cancer was identified, we asked the participant (or next of kin for those who had died) for permission to review their medical records and pathology reports. Because accuracy of self-reported breast cancer was high in this cohort (99 %), diagnoses with unavailable medical records (n = 547) were included in the analysis. Information on estrogen and progesterone receptors status of tumors was extracted from medical records. Deaths were identified by reports of next of kin, the postal service in response to the follow-up questionnaires, or by searching the National Death Index.

Assessment of covariates

In the biennial NHSII questionnaires, we inquired about potential risk factors for breast cancer, including age, history of benign breast disease, family history of breast cancer, smoking, race, menopausal status, menopausal hormone use, oral contraceptive use, and weight. These data were updated to the most recent information, if available. Height, body mass index (BMI) at age 18 and adolescent alcohol consumption were reported on the 1989 questionnaire. Women were considered premenopausal if they still had periods. Women were considered postmenopausal if they reported natural menopause, or had undergone bilateral oophorectomy. We defined women of unknown menopausal status or who had hysterectomy without bilateral oophorectomy as premenopausal if they were younger than 46 years for smokers or younger than 48 years for nonsmokers and as postmenopausal if they were 54 years or older for smokers or 56 years or older for nonsmokers [18].

Statistical analysis

We calculated premenopausal cumulative average of dietary intakes by using the 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, and 2011 dietary intake data, and stopping updating after reporting menopause. Grain food intakes reported on the baseline FFQ (1991), when participants were 27–44 years of age, were considered early adulthood dietary intake. To evaluate adult diet and breast cancer, participants contributed person-years from the date of return of the 1991 questionnaire until the date of any cancer diagnosis (except nonmelanoma skin cancer), death, or end of follow-up period (June 1, 2013), whichever was earlier. For adolescent grain food intake, participants contributed person-years similarly except that follow-up began with return of the adolescent diet questionnaire in 1998. Participants were divided into quintiles according to their dietary intake. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to calculate relative risks (RR) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) for each category, using the lowest quintile of intake as the reference category. To control for confounding by age, calendar time, or any possible two-way interactions between these two time scales, we stratified by age in month and 2-year time periods. Multivariable models also simultaneously adjusted for various confounding factors including race, history of breast cancer in mother or sisters, history of benign breast disease, smoking, height, BMI at age 18, weight change since age 18, age at menarche, parity and age at first birth, oral contraceptive use, menopausal status, post menopausal hormone use, age at menopause, physical activity, and intakes of alcohol and energy. For adolescent grain food intake and breast cancer risk, multivariable models adjusted additionally for adolescent alcohol intake and adolescent energy intake, rather than adult energy intake. Test for trend was performed by assigning the median value for each quintile and modeling as a continuous variable. We also calculated the average of adolescent and early adulthood (1991) intakes of whole grain and refined grain foods among women with available information for both periods.

To identify whether the associations were independent of a generally healthy dietary pattern, we additionally controlled for a modified alternate healthy eating index (AHEI) [19] score that the score for whole grain foods was not included to avoid redundancy. We also evaluated the associations after additional adjustment for dietary fiber, total red meat or total fruit and vegetables intake, which were associated with risk of breast cancer in our prior studies [12, 20–22]. To determine whether the associations with adolescent dietary intakes were independent of adulthood dietary intakes, we adjusted for cumulative average of dietary intakes during adult life. To examine if the associations between whole grain food intake and breast cancer risk were modified by BMI at age 18 (<21 or ≥21 kg/m2), a cross-product interaction term for this variable and whole grain food intake was included in the multivariable model. Tests for interactions were obtained from a likelihood ratio test. We evaluated the effects of whole grain and refined grain food intake in relation to breast cancer risk by tumor hormone receptor status using Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression with a duplication method for competing risk data. This method allows estimation of separate associations of diet for tumors that are both estrogen and progesterone receptors positive (ER+/PR+) and both receptors negative (ER−/PR−), and is used to evaluate if a risk factor has statistically different regression coefficients for different tumor subtype [23]. All P values were two-sided. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

During 22 years of follow-up, 3235 women developed invasive breast cancers for the adult dietary analyses, among which there were 1347 invasive breast cancers for the adolescent dietary analyses. At the time of dietary assessment (1991 for adult and 1998 for adolescent diet), higher consumption of whole grain foods in adulthood and adolescence was associated with a lower prevalence of smoking, lower consumption of animal fat, and higher consumption of fiber, fruits, and vegetables (Tables 1, S3). Women with higher consumption of adolescent whole grain food were also less likely to drink alcohol. Higher intake of refined grain during adult life was associated with higher intake of fiber, total red meat, fruit and vegetables and, lower intake of animal fat (Table 1). Women with high intake of refined grain during adult life were also less likely to smoke, to use oral contraceptive pills, and to be nulliparous. Higher adolescent refined grain intake was associated with higher adolescent intake of alcohol, total red meat, fruit and vegetables, and lower intake of fiber and animal fat (Table S3).

Adult grain food intake and breast cancer risk

Cumulative average of premenopausal intake of whole grain foods was associated with lower risk of breast cancer before menopause (highest vs. lowest quintile RR 0.82; 95 % CI 0.70–0.97; P trend = 0.03), but not overall or postmenopausal breast cancer (Table 2). This association was attenuated after further adjustment for fiber intake (highest vs. lowest quintile RR 0.89; 95 % CI 0.73–1.07; P trend = 0.31), fruit and vegetables intake (highest vs. lowest quintile RR 0.84; 95 % CI 0.71–0.99; P trend = 0.06), total red meat intake (highest vs. lowest quintile RR 0.84; 95 % CI 0.71–1.00; P trend = 0.07), or AHEI (highest vs. lowest quintile RR 0.85; 95 % CI 0.72–1.01; P trend = 0.09). Cumulative average of premenopausal refined grain food intake was not significantly associated with risk of overall breast cancer (highest vs. lowest quintile RR 0.88; 95 % CI 0.76–1.01; P trend = 0.06), premenopausal breast cancer, or postmenopausal breast cancer (Table 2). With mutual adjustment for whole grain and refined grain foods, the association among refined grain food intake was not materially changed (for overall breast cancer RR 0.88; 95 % CI 0.77–1.02; P trend = 0.07).

Most individual grain-containing foods were not significantly associated with risk of breast cancer (Fig. 1). However, cumulative average of premenopausal white bread intake was associated with increased risk of overall breast cancer (for each 2 servings/week: RR 1.02; 95 % CI 1.01–1.04), as well as breast cancer before menopause (for each 2 servings/week: RR 1.03; 95 % CI 1.00–1.05) and after menopause (for each 2 servings/week: RR 1.03; 95 % CI 1.00–1.06). Cumulative average of brown rice intake during premenopausal adult life was inversely associated with risk of overall breast cancer (for each 2 servings/week: RR 0.94; 95 % CI 0.89–0.99) and premenopausal breast cancer (for each 2 servings/week: RR 0.91; 95 % CI 0.85–0.99), but not postmenopausal breast cancer (for each 2 servings/week: RR 0.98; 95 % CI 0.90–1.07) (Fig. 1). These associations were slightly attenuated after further adjustment for fiber intake (each 2 servings/week for overall breast cancer: RR 0.95; 95 % CI 0.90–1.01; for premenopausal breast cancer: RR 0.93; 95 % CI 0.86–1.01; for postmenopausal breast cancer: RR 0.99; 95 % CI 0.91–1.08). The associations were materially unchanged after additional adjustment for fruit and vegetable intake, total red meat intake, or AHEI (data not shown). Cumulative average of premenopausal white rice intake was not associated with premenopausal breast cancer risk. However, an inverse association between white rice and overall and postmenopausal breast cancer risk was noted (for each 2 servings/week for overall breast cancer: RR 0.97; 95 % CI 0.94–1.00; for postmenopausal breast cancer: RR 0.95; 95 % CI 0.90–1.00). A similar association was observed when Asian women (n = 1434) were excluded from analysis (data not shown). Cumulative average of pasta intake before menopause was also inversely associated with overall breast cancer risk (for each 2 servings/week: RR 0.97; 95 % CI 0.94–1.00), but not premenopausal or postmenopausal breast cancer (Fig. 1).

Multivariable relative risks (RRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) for every 2 servings/week specific grain-containing food intake during adulthood and adolescence and breast cancer risk. Multivariable model was stratified by age in months at start of follow-up and calendar year of the current questionnaire cycle and was simultaneously adjusted for smoking (never, past, current 1 to 14/day, current 15 to 24/day, current ≥25/day), race (white, nonwhite), parity and age at first birth (nulliparous, parity ≤2 and age at first birth <25 years, parity ≤2 and age at first birth 25 to <30 years, parity ≤2 and age at first birth ≥30 years, parity 3 to 4 and age at first birth <25 years, parity 3 to 4 and age at first birth 25 to <30 years, parity 3 to 4 and age at first birth ≥30 years, parity ≥5 and age at first birth <25 years, parity ≥5 and age at first birth ≥25 years), height (<62, 62 to <65, 65 to <68, ≥68 inches), BMI at age 18 years (<18.5, 18.5 to <22.5, 22.5 to <25, 25.0 to <30, ≥30.0 kg/m2), weight change since age 18 (continuous, missing indicator), age at menarche (<12, 12, 13, ≥14 years), family history of breast cancer (yes, no), history of benign breast disease (yes, no), oral contraceptive use (never, past, current), adult alcohol intake (nondrinker, <5, 5 to <15, ≥15 g/day), physical activity (quintile), and energy intake (quintile). In postmenopausal women, we additionally adjusted for hormone use (postmenopausal never users, postmenopausal past users, postmenopausal current users), and age at menopause (<45, 45–46, 47–48, 49–50, 51–52, ≥53 years). Among all women, we additionally adjusted for hormone use and menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal never users, postmenopausal past users, postmenopausal current users, unknown menopausal status), and age at menopause (premenopausal, unknown menopause, <45, 45–46, 47–48, 49–50, 51–52, ≥53 years). For adolescent grain intake, we additionally adjusted for adolescent alcohol intake (nondrinker, <5, ≥5 g/day) and adolescent energy intake (quintile) (instead of adult energy intake)

Grain food intakes reported on the baseline FFQ (1991) were considered early adulthood dietary intake. Early adulthood intakes of whole grain or refined grain foods were not associated with risk of breast cancer (Table 3). When early adulthood specific grain-containing food intake was examined, an inverse association was observed between brown rice intake and overall and premenopausal breast cancer, but not postmenopausal breast cancer. Early adulthood white bread intake was associated with higher risk of premenopausal breast cancer. Further, early adulthood white rice intake was associated with lower risk of overall and postmenopausal breast cancer and early adulthood cooked oatmeal intake was somewhat associated with lower risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (data not shown).

Adolescent grain food intake and breast cancer risk

Adolescent intakes of whole grain or refined grain foods were not associated with risk of breast cancer (Table 4). Results were similar after additional adjustment for adult intake of whole grain or refined grain foods (data not shown). Adolescent white bread, dark bread, or rice intake was not also associated with risk of breast cancer. Adolescent cold breakfast cereal intake was inversely associated with risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (for each 2 servings/week: RR 0.93; 95 % CI 0.87–0.99), but not premenopausal or overall breast cancer (Fig. 1). No other significant association was observed.

Average adolescence and early adulthood grain food intake and breast cancer risk

Adolescent and early adult (1991) whole grain food intakes were only modestly correlated (r = 0.28). Among women with both early adulthood and adolescent dietary data (n = 41,092), we observed an inverse association between average adolescent and early adulthood intake of whole grain food and premenopausal breast cancer (highest vs. lowest quintile: RR 0.74; 95 % CI 0.56–0.99; P trend = 0.09), but not overall breast cancer (highest vs. lowest quintile: RR 0.88; 95 % CI 0.73–1.06; P trend = 0.13), or postmenopausal breast cancer (highest vs. lowest quintile: RR 0.94; 95 % CI 0.71–1.23; P trend = 0.30). However, this association was no longer significant after further adjustment for fiber intake (data not shown). We observed inverse associations between average adolescent and early adulthood intake of refined grain food and postmenopausal breast cancer (highest vs. lowest quintile: RR 0.72; 95 % CI 0.53–0.98; P trend = 0.04), but not overall (RR 0.82; 95 % CI 0.66–1.01; P trend = 0.07) or premenopausal breast cancer risk (RR 0.97; 95 % CI 0.70–1.33; P trend = 0.84).

Breast cancer subtypes and subgroups

The inverse association with adolescent whole grain food intake was stronger for ER−/PR− cancers (HR 0.60; 95 % CI 0.38–0.96, each serving/day) compared to ER+/PR+ cancers before menopause (HR 0.97; 95 % CI 0.81–1.17) (P for difference by receptor status = 0.046). Adolescent refined grain food intake was suggestively associated with higher risk of ER+/PR+ cancers (HR 1.07; 95 % CI 0.95–1.20, each serving/day) and with lower risk of ER−/PR− cancers among premenopausal women (HR 0.80; 95 % CI 0.64–1.01, each serving/day) (P for difference by receptor status = 0.01) (Table S4). Associations between whole grain and refined grain food intake and breast cancer risk did not differ significantly by BMI at age 18 for either cumulative average, early adulthood, or adolescent diets (data not shown).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that higher adult whole grain food intake may be associated with lower premenopausal breast cancer risk. Further, an inverse association was observed between average adolescent and early adulthood intake of whole grain food and premenopausal breast cancer risk. However, these associations were somewhat mediated with fiber intake. No single food or type of grain appeared to account for these findings. The exceptions were consumption of brown rice during adulthood that was associated with lower risk of breast cancer and white bread consumption that was associated with higher risk. Further, pasta intake was inversely associated with overall breast cancer risk. We also noted that high whole grain intake during adolescence is associated with reduced premenopausal risk of both estrogen and progesterone receptors negative tumors.

The association between whole grain intake and breast cancer has been evaluated in few prospective studies [6–8]. Intake of whole grain foods was not associated with risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in Danish and the US women [6, 8]. High intake of high-fiber bread was associated with lower risk of breast cancer in Malmo Diet and Cancer cohort [7]. Compared with refined grain foods, whole grain foods have a high content of many nutrients and bioactive components as well as fiber that may offer significant health benefits. Our previous analysis within the NHSII indicated that high intake of fiber during adolescence and early adulthood was associated with decreased risk of breast cancer in later life [12]. We noted nonsignificant association between whole grain food intake and premenopausal breast cancer after additional adjustment for fiber, suggesting that fiber or correlated constituents of whole grains may account for the association with whole grain foods.

Rice is an important source of arsenic in the U.S. diet, and arsenic levels are higher in brown rice than in white rice [24, 25]. While concerns about arsenic in some rice products have been recently raised in the United States [26], we observed that adult brown rice was associated with lower risk of breast cancer. As we examined many relationships between specific foods and breast cancer, this inverse association could be due to chance and needs confirmation. However, this finding is reassuring regarding the health concerns over arsenic in brown rice. Only a few epidemiological studies have investigated whether a high intake of rice is associated with risk of breast cancer. We earlier reported a lower risk of breast cancer with high lifetime intake of rice in the same NHSII cohort [27]. In contrast, among women in Nurses’ Health Study cohort, high intake of total rice was not associated with risk of breast cancer [27]. However, it is unclear whether the significant findings in NHSII were as a result of early age at dietary assessment or the relatively young age of women at breast cancer diagnosis. Similarly, lower risk of breast cancer was also reported with high intake of brown rice in a cross-sectional study in South Korean postmenopausal women [28].

Potential limitations need to be considered. The participants were limited to predominantly white women that could reduce generalizability; however, it would be unlikely that the biology underlying these associations differs substantially according to race or ethnicity. Residual confounding is also of concern in observational studies. With the detailed NHSII questionnaires, we have tried to adjust for all known breast cancer risk factors. Adolescent diet may be misclassified because women recalled their dietary intake during adolescence when they were 33 to 52 years old. However, evidence of validity came from comparisons of diet recorded during adolescence and our questionnaire administered 10 years later [16, 17]. Further, because diet was assessed before breast cancer diagnosis, misclassification would tend to be nondifferential and may dilute the associations.

Our study has several strengths. The large sample size and dietary assessments during adolescence, early adulthood, and cumulatively over the premenopausal period allowed examination of exposures during specific periods of life. We were also able to examine breast cancers by menopausal and hormone receptor status.

In summary, our findings suggest that higher of whole grain foods may play a role in prevention of premenopausal breast cancer.

References

http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf

Seal CJ, Brownlee IA (2015) Whole-grain foods and chronic disease: evidence from epidemiological and intervention studies. Proc Nutr Soc 74:313–319

Aune D, Norat T, Romundstad P, Vatten LJ (2013) Whole grain and refined grain consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 28:845–858

Cho SS, Qi L, Fahey GC Jr, Klurfeld DM (2013) Consumption of cereal fiber, mixtures of whole grains and bran, and whole grains and risk reduction in type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 98:594–619

Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, Norat T (2011) Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 343:d6617

Egeberg R, Olsen A, Loft S, Christensen J, Johnsen NF, Overvad K, Tjønneland A (2009) Intake of whole grain products and risk of breast cancer by hormone receptor status and histology among postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer 124:745–750

Sonestedt E, Borgquist S, Ericson U, Gullberg B, Landberg G, Olsson H, Wirfält E (2008) Plant foods and oestrogen receptor alpha- and beta-defined breast cancer: observations from the Malmo Diet and Cancer cohort. Carcinogenesis 29:2203–2209

Nicodemus KK, Jacobs DR Jr, Folsom AR (2001) Whole and refined grain intake and risk of incident postmenopausal breast cancer (United States). Cancer Causes Control 12:917–925

Land CE, Tokunaga M, Koyama K, Soda M, Preston DL, Nishimori I, Tokuoka S (2003) Incidence of female breast cancer among atomic bomb survivors, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1950-1990. Radiat Res 160:707–717

Swerdlow AJ, Barber JA, Hudson GV, Cunningham D, Gupta RK, Hancock BW, Horwich A, Lister TA, Linch DC (2000) Risk of second malignancy after Hodgkin’s disease in a collaborative British cohort: the relation to age at treatment. J Clin Oncol 18:498–509

Wahner-Roedler DL, Nelson DF, Croghan IT, Achenbach SJ, Crowson CS, Hartmann LC, O’Fallon WM (2003) Risk of breast cancer and breast cancer characteristics in women treated with supradiaphragmatic radiation for Hodgkin lymphoma: Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc 78:708–715

Farvid MS, Eliassen AH, Cho E, Liao X, Chen WY, Willett WC (2016) Dietary fiber intake in young adults and breast cancer risk. Pediatrics 137:e20151226

Willett W, Lenart E (2013) Reproducibility and validity of food frequency questionnaires. Nutritional Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 96–141

Wu H, Flint AJ, Qi Q, van Dam RM, Sampson LA, Rimm EB, Holmes MD, Willett WC, Hu FB, Sun Q (2015) Association between dietary whole grain intake and risk of mortality: two large prospective studies in US men and women. JAMA Intern Med 175:373–384

de Munter JS, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Franz M, van Dam RM (2007) Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med 4:e261

Maruti SS, Feskanich D, Rockett HR, Colditz GA, Sampson LA, Willett WC (2006) Validation of adolescent diet recalled by adults. Epidemiology 17:226–229

Maruti SS, Feskanich D, Colditz GA, Frazier AL, Sampson LA, Michels KB, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Willett WC (2005) Adult recall of adolescent diet: reproducibility and comparison with maternal reporting. Am J Epidemiol 161:89–97

Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Stason WB, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE (1987) Reproducibility and validity of self-reported menopausal status in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 126:319–325

Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (2012) Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr 142:1009–1018

Farvid MS, Cho E, Chen WY, Eliassen AH, Willett WC (2015) Adolescent meat intake and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer 136:1909–1920

Farvid MS, Cho E, Chen WY, Eliassen AH, Willett WC (2014) Dietary protein sources in early adulthood and breast cancer incidence: results from a prospective cohort study. BMJ 348:g3437

Farvid MS, Chen WY, Michels KB, Cho E, Willett WC, Eliassen AH (2016) Fruit and vegetable consumption in adolescence and early adulthood and risk of breast cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ 353:i2343

Lunn M, McNeil D (1995) Applying Cox regression to competing risks. Biometrics 51:524–532

(2012) Arsenic in your food: our findings show a real need for federal standards for this toxin. Consum Rep 77:22–27

(2014) FDA data show arsenic in rice juice and beer. Consum Rep 79: 14–15

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Arsenic in Rice and Rice Products [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/Metals/ucm319870.htm

Zhang R, Zhang X, Wu K, Wu H, Sun Q, Hu FB, Han J, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL (2016) Rice consumption and cancer incidence in US men and women. Int J Cancer 138:555–564

Yun SH, Kim K, Nam SJ, Kong G, Kim MK (2010) The association of carbohydrate intake, glycemic load, glycemic index, and selected rice foods with breast cancer risk: a case-control study in South Korea. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 19:383–392

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants (R01 CA050385, UM1 CA176726) and a grant from The Breast Cancer Research Foundation. The study sponsors were not involved in the study design and collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of the article or the decision to submit it for publication. The authors were independent from study sponsors. We would like to thank the participants and staff of the NHSII for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors’ responsibility were as follows: MSF, EC, WYC, AHE, and WCW designed the research; MSF performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript; MSF and WCW had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript; and all authors provided critical input in the writing of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farvid, M.S., Cho, E., Eliassen, A.H. et al. Lifetime grain consumption and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 159, 335–345 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3910-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3910-0