Abstract

In this paper, we have fabricated 3D carbon nanofiber microelectrode arrays (MEAs) with highly reproducible and rich chemical surface areas for fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV). Carbon nanofibers are created from negative photoresist by a new process called dual O2 plasma-assisted pyrolysis. The proposed approach significantly improves film adhesion and increases surface reactivity. We showcase our sensor’s compatibility with FSCV analysis by demonstrating highly sensitive and stable FSCV dopamine measurements on a prototype 4-channel array. We envision with proper surface fuctionalization the 3D carbon nanofiber MEA enable sensitive and reliable detection of multiple neurotransmitters simultaneously.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There are growing interests in integrating electrochemical detection into microsensor platforms for neurochemical analyses (Nyholm 2005; Sinkala et al. 2012). Fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) provides quantitative chemical information in real-time, making this method a desirable electroanalytical tool for neurochemistry. However, the majority of FSCV experiments have been performed using carbon-fiber microelectrodes (CFM), which only allows single measurement. For multi-unit FSCV analysis, it is necessary to increase the sensitivity of the carbon electrodes when the diffusion of analyte to electrode is more restricted due to reduced electrode surfaces. Researchers are have explored novel microfabrication methods to facilitate multi-unit FSCV detection (Sinkala et al. 2012).

A microfabrication process involving pyrolysis of a patterned photoresist has been developed to form pyrolyzed photoresist film (PPF) microelectrode arrays (MEAs) (Wang et al. 2005; Niwa and Tabei 1994; Song et al. 2014; Kostecki et al. 2002; VanDersarl et al. 2015; Moretto et al. 2015; Dengler and McCarty 2013; Zachek et al. 2008; Zachek et al. 2010; Zachek et al. 2009; Penmatsa et al. 2012; Penmatsa et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2008; Xi et al. 2013). Photoresist, as a starting material for microelectrode fabrication, is especially advantageous because it can be patterned by lithographic techniques with high resolution reproducibly (Kim et al. 1998). PPF electrodes have been demonstrated to sense molecules such as neurotransmitters (VanDersarl et al. 2015; Dengler and McCarty 2013; Zachek et al. 2008; Zachek et al. 2010; Zachek et al. 2009), O2 (Zachek et al. 2009), glucose (Xu et al. 2008; Xi et al. 2013), H2O2 (Penmatsa et al. 2012), DNA (Donner et al. 2006), mercury (Sánchez-Molas et al. 2013), and nickel (Moretto et al. 2015). It is well accepted that increasing the reactive surface area of a sensing device is an effective way to improve electrode sensitivity and to enhance the limit of detection (LOD) (Song et al. 2014). Because it is desirable to maintain the miniaturized geometry of sensing surfaces, a number of approaches have been used to increase the physical reaction sites, including 3D architecture (Song et al. 2014; VanDersarl et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2008), nanomaterial coatings (Penmatsa et al. 2012; Xi et al. 2013), flame etching (Strand and Venton 2008), laser activation (Poon and McCreery 1986), and electrochemical treatments (Heien et al. 2003; Gonon et al. 1981; Roberts et al. 2010; Takmakov et al. 2010). These methods either generate new surface area or refresh the surfaces by removing adsorbed, interfering reactants. Among these methods, creating 3D geometries is particularly effective for increasing surface area. Traditionally, this process involves depositing and patterning the photoresist into 3D cylinders (microns in diameter), followed by pyrolysis (Song et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2008). This process still produces limited surface areas.

Our research focuses on pairing FSCV to carbon nanofiber MEAs for real-time, sub-second measurements of dopamine (DA) at multiple surfaces with high selectivity and sensitivity. We achieve this by a novel method to fabricate carbon nanofiber MEAs from pyrolyzed negative photoresist. We employ dual O2 plasma including a primary plasma before and a secondary plasma after pyrolysis, a process called plasma-assisted pyrolysis. Our MEAs contain nanostructures formed on 3D cylinders from pyrolzed photoresist due to the oxygen plasma treatments. Nanostructures facilitate higher surface area than micro-sized structures because of their diminished sizes. The surface morphology is characterized by atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The chemical groups and structures are characterized by Raman and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). We characterize the electrodes’ performances to assess their suitability for FSCV analysis and show highly sensitive, stable and reproducible FSCV measurements on prototype 4-channel array. The high sensitivity, stability and reproducibility on confined substrate geometry make our 3D carbon nanofiber MEAs very attractive for real-time electrochemical monitoring.

2 Experimental

2.1 Chemicals

Dopamine solutions were prepared by dissolving dopamine HClO into Tris-buffer prior to each experiment. Tris-buffer constituents (15 mM H2NC(CH2)OH)3·HCl, 140 mM NaCl, 3.25 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4·H2O, 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 2.0 mM Na2SO4 with the pH adjusted to 7.4) were purchased from EMD Chemicals Inc., USA. All aqueous solutions were made with deionized water.

2.2 Electrode fabrication

The process flow of the electrode fabrication is shown in Fig. 1. After standard RCA cleaning, 1 μm low-stress silicon nitride was grown on a silicon substrate by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD). Ti/Pt (20 nm/200 nm) was deposited by e-beam evaporation and patterned by lift-off to serve as electrode pads and interconnections. 2 μm silicon oxide was deposited by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) and patterned to expose electrodes and contact pads. SU-8 photoresist was patterned onto the electrode area. Next, the sample was treated by primary O2 plasma (8 min, 300 W, 30 sccm O2, 160 mTorr) in order to create filament-like nanostructures in SU-8.

A two-step pyrolysis was performed to convert the SU-8 polymer to carbon. The samples were first heated in a nitrogen environment (500 sccm, 80 Torr) at 300 °C for 30 min. Then the temperature was risen to 900 °C in 20 min. The nitrogen gas was turned off and a mixture of H2 (2 %)/Ar (500 sccm, 80 Torr) was introduced for 1 h. The furnace was then slowly cooled down to room temperature. The wafer was diced to release the devices. A secondary O2 plasma step was applied to the obtained electrodes (30 s, 100 W, 30 sccm O2, 160 mTorr) in order to enhance sensitivity.

The samples with different treatments were labelled as included in Table 1.

2.3 Electrode characterization

The morphology of the fabricated electrodes was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FIB/SEM GAIA TESCAN). The surface roughness of the electrodes was assessed using a NanoScope AFM with silicon TESP probe tips (Nanosensors). The degree of graphitization was measured using the E-Z Raman spectroscopy system excited by a 532 nm laser. The chemical composition of the treated surface was investigated by X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) on a Kratos Axis Ultra spectrometer that was equipped with a monochromatic Al X-ray source (hν = 1486.6 eV). The measurements were carried out at 150 W power (15 kV, 10 mA) in an analysis chamber at a pressure of <5 × 10−9 mbar.

2.4 Electrochemical instrumentation and data acquisition

All electrochemical experiments were performed using a Dagan ChemClamp potentiostat (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN). Custom-built software, WCCV (Knowmad Technologies, AZ), written in LABVIEW2012 (National Instruments, Austin, TX), was used for background subtraction, data analysis and signal processing. A two-electrode system was employed. The fabricated MEA served as a working electrode. A Ag/AgCl reference electrode was fabricated by electroplating Cl− ions onto a silver wire (A-M systems, WA) for 5 s. All color plots and cyclic voltammograms (CVs) were collected and averaged across 12 different electrodes of 3 devices. Pooled data was presented with error bars signifying the standard error of the mean (SEM). Student’s t tests were performed on paired data sets; p < 0.05 was taken as significant.

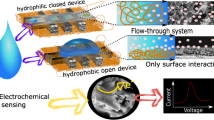

2.5 Flow injection system

A MEA was fixed in a HPLC union (Elbow, PEEK 3432, IDEX, Middleboro, MA), and connected by the output of a flow injection apparatus. The apparatus consisted of a six-port HPLC loop injector affixed to a two-position actuator (Rheodyne model 7010 valve and 5701 actuator) and an infusion syringe pump (kd Scientific, model KDS-410, Holliston, MA). A rectangular pulse of analyte was introduced to the MEA’s surface at a flow rate of 2 mL min−1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Electrode design and fabrication

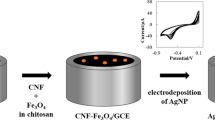

Microlithography using photoresist is a well-developed technique in the semiconductor industry. Pyrolysis of photoresist in an oxygen-free atmosphere is known to form carbon structures via depletion of volatile materials. Therefore, we have employed the photoresist as a structural material to create a carbon electrode array that is integratable into microdevices. The novelty in our work is incorporation of a two-step pyrolysis procedure (different temperatures) and a dual O2 plasma treatment (different powers and durations) and two-step pyrolysis procedure (different temperatures). The schematic demonstration of the process is shown in Fig. 2a.

In our electrode design and fabrication, there are three aspects to address:

-

a)

Electrode geometry and dimensions: Our interests lie in biological analysis, and it is desirable for electrode dimensions to be minimized. As a starting point, an active geometric area ranging from 3000 μm2 (30 × 100 um) was chosen, which was comparable to that of cylindrical CFMs used in previous studies (Yang et al. 2015). As shown in Fig. 2b, c, four electrodes were fashioned in parallel as an array to form the tip of a single device with a spacing of 30 μm to minimize tissue damage when used in-vivo (Khan and Michael 2003) and to prevent cross-talk (Zachek et al. 2009).

-

b)

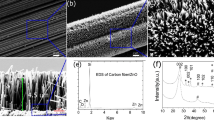

Control of surfaces and structures: Producing an active carbon surface with sufficient reaction sites over a fixed geometric area is important for electrochemistry. An O2 plasma pre-treatment plus pyrolysis created a forest of highly reactive carbon nanofibers, with abundant edge planes. These carbon nanofibers had greatly augmented surface area compared with flat carbon film electrodes. PPF without pretreatments resembled a flat plane as shown in Fig. 3a-c while the pretreated PPF consisted of carbon nanofiber structures in Fig. 3d-f. The mechanisms of nanofiber formation have been described in the literature (De Volder et al. 2011). The SU-8 polymer chain is composed of both aromatic and linear sections and the etching rates of these two sections are different. This phenomenon results in a faster growth rate in a vertical direction, and promotes the formation of nano-filaments, a precursor for nanofibers. The crystallization temperature for SU-8 is generally higher than positive photoresists due to high numbers of ringed hexagons. Thus at the same pyrolysis temperature, more defect sites will be formed on SU-8 than positive photoresists (Singh et al. 2002), an auspicious surface effect for electrochemical applications (Roberts et al. 2010).

-

c)

Stability: One of the issues for FSCV using pyrolyzed photoresist is its poor adhesion to the substrate. SU-8 is a negative photoresist and is known to have better adhesion after pyrolysis compared with positive photoresists (Singh et al. 2002; Ranganathan and McCreery 2001). The negative photoresists typically have lower glass transition temperatures and lower molecular weights, which is in favor of thermal softening and rounding (reflow) during pyrolysis. This property results in fewer pores and cracks (Singh et al. 2002; Ranganathan and McCreery 2001). Because pores and cracks are usually the cause of poor adhesion, negative photoresists tend to display better stability (Singh et al. 2002; Ranganathan and McCreery 2001). Nevertheless, we and others still experienced peeling-off of carbon patterns when using the traditional one-step pyrolysis of SU-8 (data not shown) (De Volder et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2002). This problem was addressed by employing a two-steps heating process. The process involved an initial step of heating at lower temperature (300 °C for 30 min) before utilizing 1000 °C. The additional low temperature led to better adhesion and allowed devices with stable performance in an aqueous environment. The two-step heating alleviated intrinsic stress that was caused by the difference in thermal expansion coefficient between the photoresist and the substrate. Similarly, less dramatic degassing occurred during pyrolysis, which reduced the formation of micro-crack. Both of these effects improved the adhesion of the carbon film. Finally, we postulated that the primary O2 plasma itself also contributed to the adhesion improvement, and tested this notion at the following section.

SEM images of electrode CMEA 100 (a) and CMEA 200 (d). AFM images with associated line plots collect at electrodes CMEA 100 (b), CMEA 102 (c), CMEA 200 (e), and CMEA 202 (f). The primary oxygen plasma pre-treatment does contribute to increase the surface roughness, while the secondary oxygen plasma treatment does not

3.2 Characterization of carbon nanofiber MEAs

Having designed our electrodes with the correct dimensions, and to have a suitable surface area and stability for our applications, we next characterized our electrodes by employing a host of surface and microstructure analysis methods.

To ensure that a dual O2 plasma treatment did not negatively influence surface structures of carbon-nanofiber electrodes, AFM with a tapping mode was used to characterize surface morphology. Images (5 × 5 μm) are presented in Fig. 3. The surface features of pyrolyzed photoresist after primary O2 plasma were greatly enhanced (Fig. 3e and f) compared to that without plasma treatment (Fig. 3b and c). For both pyrolyzed photoresist MEAs with and without primary O2 plasma, there were no significant topology changes after the secondary plasma (Fig. 3c and f), showing that a dual plasma process did not unfavorably impact the surfaces.

To verify that carbon nanofibers prepared by the dual O2 plasma treatment and pyrolysis were suitable for electrochemistry, Raman spectroscopy was used to indicate the presence of more reaction sites (defects and edge planes) on the surfaces. The D band at 1350 cm−1 is associated with disordered carbon while the G band at 1590 cm−1 can be assigned to crystallized graphitic structure (Kachoosangi and Compton 2007). The ratio of intensity of D band over G band (ID/IG) has been frequently used as an indicator of the fraction of disordered sp2 C-C bonding present in the graphitic structure. The higher ID/IG of graphitic structure is indicative of presence of more defects or edge planes (Roberts et al. 2011). Fig. 4 shows Raman spectra of SU-8 before pyrolysis (CMEA 001/002), after pyrolysis and no O2 plasma (CMEA 100), after pyrolysis and the secondary plasma (CMEA 103), after pyrolysis and the primary plasma (CMEA 200) and after pyrolysis and dual plasma (CMEA 203).

Raman spectra of the photoresist derived electrodes with different treatments. Before pyrolysis, both pre-treated and un-pretreated samples (CMEA001/002) exhibit no characteristic peaks because of high fluorescence of SU8. After pyrolysis, primary plasma-treated samples (CMEA 200) show a bigger ID/IG ratio than un-treated ones (CMEA 100), indicating more defects and more edge planes. The later application of secondary oxygen plasma results in no significant change of ID/IG on both primary plasma-treated (CMEA 203) and un-treated samples (CMEA 103)

Before pyrolysis, no characteristic peak was present. However, after pyrolysis, two broad peaks centered on D band and G band cm−1 were observed. The Raman ID/IG ratios, as well as the XPS O/C ratios for the different samples are summarized in Table 1. The samples treated with primary plasma had a higher ID/IG ratio (~ 1.1) compared to the untreated samples (ID/IG ~ 0.9) showing presence of more edge planes/defects. The samples treated with primary plasma had lower peak intensity than the untreated one, possibly due to the change of morphology and the formation of nanostructures (Zestos et al. 2013). Interestingly, CMEA 100 and CMEA 103 had the same ID/IG ratio, indicating the secondary O2 plasma did not introduce significant amount of defects to the structures.

On conventional CFMs, the electrochemical signals are inherently regulated by adsorption of analytes, which itself is controlled by the presence of oxygen moieties on the carbon surface. Thus to verify that our electrodes contain sufficient oxygen groups, XPS was utilized to analyze chemical groups on the surfaces. The samples were vacuum-sealed immediately upon removal from the furnace or plasma chambers for XPS experiments. Although a short-time exposure to air may result in slight oxidation of the surfaces, the oxidation of pyrolyzed photoresist in air has been shown to be negligible within the time frame during sample transfer (Ranganathan et al. 2000). Therefore, the changes in the XPS spectra were considered to be caused by different fabrication parameters and treatments. The ratio of atomic concentration of oxygen to carbon (O/C) (see Table 2) was determined from the C1s and O1s spectra (Fig. 5). As expected, primary O2 plasma introduced more oxygen containing groups to the surfaces. After pyrolysis, the O1s peak diminished drastically for both samples with and without O2 plasma. Previous studies on the pyrolysis of photoresist have indicated that oxygen and nitrogen were removed at 300 ~ 500 °C (Jenkins and Kawamura 1976). In our experiment, the pyrolysis was carried out at 900 °C, which led to the reduction of the O1s peak. In fact, the reductive atmosphere used for pyrolysis was expected to generate a hydrogen terminated surface (Ranganathan and McCreery 2001), which may interfere with electrochemical performance of carbon surfaces. The increase in O/C after secondary plasma treatment implies the elimination of hydrogen and subsequent surface occupation of oxygen groups, which was consistent with other’s work (Hirabayashi et al. 2013). It is worth noting that the increase of O/C in the samples treated with primary plasma was greater than that without, which may be attributed to the increased defects (binding sites for oxygen groups) after the primary plasma treatment. These data suggests that primary O2 plasma was responsible for creating more reaction sites while the secondary O2 plasma increased O containing chemical groups to the surfaces.

XPS comparison of photoresist derived MEAs with different treatments. Before pyrolysis, primary oxygen plasma treatment caused higher O/C ratio (CMEA 002) compared to un-treated sample (CMEA 001). After pyrolysis in a reductive environment, the O/C ratio decreased to a similar level for both primary plasma treated (CMEA 200) and un-treated samples (CMEA 100). Then secondary oxygen plasma treatment was applied and led to an increased O/C ratio. Dual plasma treated samples (CMEA 203) showed bigger increase of O/C compared to secondary plasma treated only samples (CMEA 103), due to larger surface areas thus more oxygen binding sites

These surface analyses illustrate that the two-step pyrolysis and the dual O2 plasma treatment created a rich carbon surface for electrochemistry; we next explored the suitability of this surface for FSCV analysis.

3.3 FSCV characterization

3.3.1 Electrochemical effects of dual O2 plasma treatments on MEAs

FSCV utilizes scan rates typically between 400 and 1000 V s-1 and acquires one cyclic voltammogram in approximately 2 ms every 100 ms. The fast scan rate renders the method highly sensitive but also generates a large charging current. Background subtraction eliminates the charging current, resulting in cyclic voltammogram characteristic of redox active species that can be used as a “fingerprint” for identification. Dopamine (DA), as a biologically important and well-characterized molecule, was chosen as a standard analyte herein to compare with related studies. A typical FSCV characterization for our MEAs is shown in Fig. 6. Cyclic voltammograms were collected for 30 s during a flow injection analysis (FIA) of 1.0 M DA onto CMEA 202. A traditional triangular waveform for DA detection was employed where the potential ramped from −0.4 V to +1.3 V and back at a scan rate of 400 V s-1 and application frequency of 10 Hz. Color plots illustrate this 30 s FIA event with an injection of DA between 5 and 15 s (interpretation of a color plot can be found in Michael et al. (Michael et al. 1998)). Figure 6a shows cyclic voltammograms taken during the DA injections at 4 channels of CMEA 202, indicated by the vertical white dashed line in the color plots from Fig. 6b. The redox peaks of DA on all channels were highly reproducible and were in accord with values reported for conventional CFMs under the same experimental conditions (Faridbod et al. 2008). Fig. 6c displays the current vs. time profiles at the maximum oxidation potential taken from the horizontal white dashed line in the color plots. Our optimized MEAs were highly sensitive, yielding 76.6 ± 4.9 nA (n = 12 ± SEM) for a 1.0 M DA injection, (compared with prior studies showing 10 nA for conventional CFMs with surface areas ~1000 μm2) (Zachek et al. 2009).

The vast improvement in sensitivity was attributed to the O2 plasma treatments for three reasons:

-

a)

Our primary plasma treatment led to formation of nanostructures on the MEAs and increased physical surface areas within equivalent geometric surfaces. It reduced FSCV response time because the flux of analytes was increased.

-

b)

The formation of the carbon nanofiber structure also introduced more edge planes (indicated by the Raman spectra). Prior studies on pyrolytic graphite have shown that edge planes are the primary reaction sites in electrochemistry (Kachoosangi and Compton 2007; Roberts et al. 2011).

-

c)

Previous studies using conventional CFMs have shown that the DA’s FSCV response was adsorption-controlled at physiological pH (Zachek et al. 2008; Zestos et al. 2013). Different methods have been used to enhance surface adsorption, including over-oxidation (to induce oxygen moieties on the carbon surface) (Zachek et al. 2008; Zachek et al. 2009) and a negative resting potential between scans (Zachek et al. 2008; Zachek et al. 2009). Our O2 plasma treatment induced many oxygen containing functional groups to the reactive sites (indicated by XPS data). As a result, DA’s adsorption, and hence sensitivity, on the electrode surface was greatly enhanced.

Next the processing parameters in dual O2 plasma treatments were optimized for better electrode performances. 12 electrodes (3 devices) were selected for a primary plasma treated (green) and untreated (purple) group. Figure 7 compares the average current responses at the maximum DA oxidation potential for both groups under secondary O2 plasma for 0, 10, 20, and 30 s. In general, the green group showed more current response than the purple group. When the treatment time of secondary plasma increased, the current response for both groups showed an overall increasing trend and reached plateau at 20 s. The plateaued response of the green group (~ 80 nA) was almost 3 times that of the purple group (~ 27 nA).

3.3.2 Calibration and limit of quantification

A standard calibration of the optimized MEAs for DA is presented in Fig. 8 (n = 12 ± SEM). The calibration was conducted within a concentration range from 0.10 μM to 10 μM. The limit of quantification (LOQ) was 0.10 μM, which was significantly lower than the reported values for PPF electrodes (Zachek et al. 2009). A linear calibration range up to 5.0 μM is appropriate for biological analyses. The sensitivity (slope) in this range was 80 nA/ μM as shown in the inset.

3.3.3 Stability

As previously discussed, the primary reason for conventional PPF electrodes to fail is peeling-off of the carbon film from the substrate. In this paper, the issue was addressed by a negative photoresist and optimized heating profiles in pyrolysis. Successive injection tests were performed for the samples with and without the primary O2 plasma treatment. 1.0 μM DA was successively injected to the flow cell 50 times, and the peak oxidation peak currents were recorded each time (n = 12 ± SEM). In Fig. 9, the normalized currents (observed current / average current) are plotted versus injection number. Both groups showed consistent responses with 50 successive injections. However, the untreated electrodes displayed a greater standard deviation (SD), likely because the primary O2 plasma can cause certain compressive stress that further enhances the adhesion of the generated carbon films.

The minimal SD of carbon nanofibers fabricated by oxygen plasma assisted pyrolysis also implies good reproducibility. Microfabrication processing offers reliable manufacturing in controlling electrode surface areas, thus improving the capability for electrochemical detection. In contrast, the CFMs made by conventional machining show a lot of variation, and may be not suitable for accurate multi-site and multi-analyte detection, even though they could be bundled up to create a compact unit.

4 Conclusions

In this paper, we described the development of novel carbon nanofiber MEAs that give highly reproducible, sensitive and stable responses when applied to FSCV. These desirable characteristics are due to carbon nanofiber formation via a novel strategy, application of a plasma-assisted pyrolysis process and a dual O2 plasma treatment. We utilized a host of analytical methods to show that our strategy greatly improves film adhesion and surface reactivity. These devices represent an important step towards dynamic, simultaneous and sensitive multi-platform FSCV detection.

References

M. F. De Volder, R. Vansweevelt, P. Wagner, D. Reynaerts, C. Van Hoof, A. J. Hart, Hierarchical carbon nanowire microarchitectures made by plasma-assisted pyrolysis of photoresist. ACS Nano 5(8), 6593–6600 (2011)

A. K. Dengler, G. S. McCarty, Microfabricated microelectrode sensor for measuring background and slowly changing dopamine concentrations. J. Electroanal. Chem. 693, 28–33 (2013)

S. Donner, H.-W. Li, E. S. Yeung, M. D. Porter, Fabrication of optically transparent carbon electrodes by the pyrolysis of photoresist films: approach to single-molecule spectroelectrochemistry. Anal. Chem. 78(8), 2816–2822 (2006)

F. Faridbod, M. R. Ganjali, R. Dinarvand, P. Norouzi, Developments in the field of conducting and non-conducting polymer based potentiometric membrane sensors for ions over the past decade. Sensors 8(4), 2331–2412 (2008)

F. Gonon, C. Fombarlet, M. Buda, J. F. Pujol, Electrochemical treatment of pyrolytic carbon fiber electrodes. Anal. Chem. 53(9), 1386–1389 (1981)

M. L. Heien, P. E. Phillips, G. D. Stuber, A. T. Seipel, R. M. Wightman, Overoxidation of carbon-fiber microelectrodes enhances dopamine adsorption and increases sensitivity. Analyst 128(12), 1413–1419 (2003)

M. Hirabayashi, B. Mehta, N. W. Vahidi, A. Khosla, S. Kassegne, Functionalization and characterization of pyrolyzed polymer based carbon microstructures for bionanoelectronics platforms. J. Micromech. Microeng. 23(11), 115001 (2013)

Jenkins, G. M.; Kawamura, K., Polymeric carbons--carbon fibre, glass and char. Cambridge University Press 1976.

R. T. Kachoosangi, R. G. Compton, A simple electroanalytical methodology for the simultaneous determination of dopamine, serotonin and ascorbic acid using an unmodified edge plane pyrolytic graphite electrode. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387(8), 2793–2800 (2007)

A. S. Khan, A. C. Michael, Invasive consequences of using micro-electrodes and microdialysis probes in the brain. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 22(8), 503–508 (2003)

J. Kim, X. Song, K. Kinoshita, M. Madou, R. White, Electrochemical studies of carbon films from pyrolyzed photoresist. J. Electrochem. Soc. 145(7), 2314–2319 (1998)

R. Kostecki, X. Song, K. Kinoshita, Fabrication of interdigitated carbon structures by laser pyrolysis of photoresist. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 5(6), E29–E31 (2002)

D. Michael, E. R. Travis, R. M. Wightman, Peer reviewed: color images for fast-scan CV measurements in biological systems. Anal. Chem. 70(17), 586A–592A (1998)

L. M. Moretto, A. Mardegan, M. Cettolin, P. Scopece, Pyrolyzed photoresist carbon electrodes for trace Electroanalysis of nickel (II). Chemosensors 3(2), 157–168 (2015)

O. Niwa, H. Tabei, Voltammetric measurements of reversible and quasi-reversible redox species using carbon film based interdigitated array microelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 66(2), 285–289 (1994)

L. Nyholm, Electrochemical techniques for lab-on-a-chip applications. Analyst 130(5), 599–605 (2005)

V. Penmatsa, T. Kim, M. Beidaghi, H. Kawarada, L. Gu, Z. Wang, C. Wang, Three-dimensional graphene nanosheet encrusted carbon micropillar arrays for electrochemical sensing. Nanoscale 4(12), 3673–3678 (2012)

V. Penmatsa, A. R. Ruslinda, M. Beidaghi, H. Kawarada, C. Wang, Platelet-derived growth factor oncoprotein detection using three-dimensional carbon microarrays. Biosens. Bioelectron. 39(1), 118–123 (2013)

M. Poon, R. L. McCreery, In situ laser activation of glassy carbon electrodes. Anal. Chem. 58(13), 2745–2750 (1986)

S. Ranganathan, R. L. McCreery, Electroanalytical performance of carbon films with near-atomic flatness. Anal. Chem. 73(5), 893–900 (2001)

S. Ranganathan, R. Mccreery, S. M. Majji, M. Madou, Photoresist-derived carbon for microelectromechanical systems and electrochemical applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 147(1), 277–282 (2000)

J. G. Roberts, B. P. Moody, G. S. McCarty, L. A. Sombers, Specific oxygen-containing functional groups on the carbon surface underlie an enhanced sensitivity to dopamine at electrochemically pretreated carbon fiber microelectrodes. Langmuir 26(11), 9116–9122 (2010)

J. G. Roberts, K. L. Hamilton, L. A. Sombers, Comparison of electrode materials for the detection of rapid hydrogen peroxide fluctuations using background-subtracted fast scan cyclic voltammetry. Analyst 136(17), 3550–3556 (2011)

D. Sánchez-Molas, J. Cases-Utrera, P. Godignon, F. J. del Campo, Mercury detection at microfabricated pyrolyzed photoresist film (PPF) disk electrodes. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 186, 293–299 (2013)

A. Singh, J. Jayaram, M. Madou, S. Akbar, Pyrolysis of negative photoresists to fabricate carbon structures for microelectromechanical systems and electrochemical applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149(3), E78–E83 (2002)

E. Sinkala, J. E. McCutcheon, M. J. Schuck, E. Schmidt, M. F. Roitman, D. T. Eddington, Electrode calibration with a microfluidic flow cell for fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. Lab Chip 12(13), 2403–2408 (2012)

Y. Song, R. Agrawal, Y. Hao, C. Chen, C. Wang, C-MEMS based microsupercapacitors and microsensors. ECS Trans. 61(7), 55–64 (2014)

A. M. Strand, B. J. Venton, Flame etching enhances the sensitivity of carbon-fiber microelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 80(10), 3708–3715 (2008)

P. Takmakov, M. K. Zachek, R. B. Keithley, P. L. Walsh, C. Donley, G. S. McCarty, R. M. Wightman, Carbon microelectrodes with a renewable surface. Anal. Chem. 82(5), 2020–2028 (2010)

J. J. VanDersarl, A. Mercanzini, P. Renaud, Integration of 2D and 3D thin film glassy carbon electrode arrays for electrochemical dopamine sensing in flexible Neuroelectronic implants. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25(1), 78–84 (2015)

C. Wang, G. Jia, L. H. Taherabadi, M. J. Madou, A novel method for the fabrication of high-aspect ratio C-MEMS structures. Microelectromechanical Systems, Journal of 14(2), 348–358 (2005)

S. Xi, T. Shi, D. Liu, L. Xu, H. Long, W. Lai, Z. Tang, Integration of carbon nanotubes to three-dimensional C-MEMS for glucose sensors. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 198, 15–20 (2013)

H. Xu, K. Malladi, C. Wang, L. Kulinsky, M. Song, M. Madou, Carbon post-microarrays for glucose sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 23(11), 1637–1644 (2008)

Y. Yang, A. A. Ibrahim, J. L. Stockdill, P. Hashemi, A density-controlled scaffolding strategy for covalent functionalization of carbon-fiber microelectrodes. Anal. Methods 7(17), 7352–7357 (2015)

M. K. Zachek, A. Hermans, R. M. Wightman, G. S. McCarty, Electrochemical dopamine detection: comparing gold and carbon fiber microelectrodes using background subtracted fast scan cyclic voltammetry. J. Electroanal. Chem. 614(1), 113–120 (2008)

M. K. Zachek, P. Takmakov, B. Moody, R. M. Wightman, G. S. McCarty, Simultaneous decoupled detection of dopamine and oxygen using pyrolyzed carbon microarrays and fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. Anal. Chem. 81(15), 6258–6265 (2009)

M. K. Zachek, J. Park, P. Takmakov, R. M. Wightman, G. S. McCarty, Microfabricated FSCV-compatible microelectrode array for real-time monitoring of heterogeneous dopamine release. Analyst 135(7), 1556–1563 (2010)

A. G. Zestos, M. D. Nguyen, B. L. Poe, C. B. Jacobs, B. J. Venton, Epoxy insulated carbon fiber and carbon nanotube fiber microelectrodes. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 182, 652–658 (2013)

Acknowledgments

The device was fabricated using Nano Fabrication Core (nFab) at Wayne State University. We acknowledge the staff support during the device fabrication. This work was supported by NSF CAREER Award (1055932).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Wenwen Yi and Yuanyuan Yang contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yi, W., Yang, Y., Hashemi, P. et al. 3D carbon nanofiber microelectrode arrays fabricated by plasma-assisted pyrolysis to enhance sensitivity and stability of real-time dopamine detection. Biomed Microdevices 18, 112 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-016-0136-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-016-0136-1