Abstract

Forensic inpatients reside for long periods in restricted environments, which do not support the presence of sexual experiences or the expression of existing needs. However, sexuality and sexual health are important aspects in the overall recovery from mental illness. Given the lack of national policies, management decisions are bestowed upon individual institutions and staff members. This research aims to describe the current sexual policies in 32 forensic psychiatric wards in Flanders (the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium), varying from low to high security, and explore the perspective of forensic inpatients regarding such policies. The research questions were answered using a survey that questioned the different forensic units. Only 56% of the wards had a sexual policy at the hospital level. Results showed no significant differences in the applicable sexual policies between the security levels, but individual differences and inconsistencies exist in the rules and agreements applied among different wards. Subsequently, 15 semi-structured in-depth interviews with inpatients were conducted using a phenomenological approach. Most of the respondents were dissatisfied with their sexuality and experienced various barriers in meeting their sexual wants and needs. The results have an added value for clinical practice and lead to recommendations in the development of an integrated sexual policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Belgium, individuals who have committed crimes due to their mental illness may be considered lacking criminal responsibility. They are not punished but subjected to an internment measure, which mandates a transfer to (forensic) psychiatric facilities to meet their right to care. According to relational, environmental, and procedural security characteristics, forensic psychiatric facilities are divided in low, medium and high security (Kennedy, 2002). In Belgium, internees—referred as forensic patients—are assigned to these security levels by a juridical decision based on clinical judgment, as there are no objective criteria to determine the most appropriate setting for each type of patient (Jeandarme et al., 2019). While categorical forensic care is provided in high and medium security units established for internees, this is not always the case in low security units. In high security settings in Flanders, the mean duration of treatment of patients discharged to a lower security level amounted 2.9 years. After their treatment in a high security unit, more than half of the patients (53.5%) were transferred to a medium security facility (Jeandarme et al., 2022). The average duration of the initial forensic admission for medium-security internees was 1.3 years (Jeandarme et al., 2019). The internment measure can be applied to various offenses, including sexual offenses. However, since the law of May 2014, internment requires a criminal offense that infringes or threatens the physical or mental integrity of others. Despite expectations of reduced internment decisions, the total number of internees has risen from 3306 internees in 2004 to 4113 internees in 2022 (whereof 2387 in Flanders and the Flemish-speaking part of Brussels) within a Belgian population of around 11 million inhabitants (Seynnaeve et al., 2023; Vander Beken, 2017). Treatment of forensic patients is complex and requires finding the right balance between two main objectives: (1) treating individuals who suffer from a mental disorder and (2) rehabilitating offenders while reducing recidivism and avoiding harm to society (Barnao et al., 2016; Völlm et al., 2016). Accordingly, the literature distinguishes two treatment models: (1) the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model and (2) the Good Lives Model (GLM). While the RNR model primarily focuses on risk management and prevention of relapse in criminal offenses (Andrews et al., 1990), the GLM aims to foster individuals' personal goals and to enhance their motivation for treatment (Ward & Fortune, 2013). As such, the GLM shifts from a risk-reduction focus toward a broader focus where enhancing individuals’ well-being and quality of life plays a major role (Ward & Fortuna, 2013). This recovery-based approach to rehabilitation aims to support patients to achieve a fulfilling life, with a focus on various domains, including sexuality (Brand et al., 2021a, 2022).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality and not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity” (WHO, 2010). Sexuality can be experienced and expressed in values, attitudes, beliefs, fantasies, thoughts, desires, behavior, practices, roles, and relationships and does not necessarily involve explicit sexual acts (WHO, 2010). Sexuality and sexual health can no longer be viewed in isolation from certain human rights recognized in international and national laws and other consensus statements (WHO, 2015). To attain and maintain sexual health, the sexual rights of a person must be respected, protected, and fulfilled (WHO, 2010). Forensic psychiatry faces numerous challenges regarding sexuality and sexual rights, including safety concerns, vulnerability to physical sexual risks such as sexually transmissible diseases (STDs), ambiguities regarding patient consent, staff reluctance, court-imposed treatment restrictions, and the nature of the committed offenses (Brown et al., 2014; Dein et al., 2016; Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Perlin, 2008; Quinn & Happell, 2015a, 2015b). Residing in forensic facilities limits the opportunities of inpatients and their partners to exercise their rights to a private life, family life and the possibility to start a family as described under Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) (Dein et al., 2016). The limited capacity for expressing sexuality during admission may be especially problematic when patients are subject to residential treatment for extended periods during their adult lives (Dein et al., 2016). Patients residing in long-term forensic care are least happy on the domain of sexuality compared to the other quality of life domains (Schel et al., 2015).

A recent study on sexual policies within forensic psychiatry showed that none of the 14 European countries involved had national guidelines on this topic (Tiwana et al., 2016). Similarly, Belgium lacks a national policy and management decisions are left to individual hospitals. Access to conjugal suites, sexual intercourse or visits from prostitutes within the institution was only allowed in a limited number of European countries (Tiwana et al., 2016).

A study in 39 out of 60 English forensic psychiatric units regarding policies on sex, marriage, and relationships showed that all high security units had written policies, while medium and low security units relied on unwritten policies. In general, there were inconsistencies across all the institutions as to what is permitted or not. In some facilities, patients could obtain condoms with caregiver approval, while in others condoms were confiscated a contraband (Bartlett et al., 2010). Many policies were intrusive into what normally would be considered as private situations in broader society. Particularly at medium and low-security levels, attitudes toward sexual or emotional expression were very restrictive. For example, some forensic psychiatric units expressly prohibited holding hands, hugging, or kissing (Bartlett et al., 2010).

In the absence of national guidelines, forensic units adopt policies that are universally restrictive rather than based on individual risk assessments (Taylor & Whiting, 2022). However, considering the complexity of human sexuality, having a policy that forbids sexual expression seems unrealistic and may even harm individuals by obstructing the fulfillment of their human needs. Whether or not a policy forbids consensual sexual expression, sexual behavior occurs, and forensic inpatients continue to have sex(ual) relations (Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Quinn & Happell, 2016). Institutional rules create barriers for inpatients, forcing their intimacy and sexual relationships into secrecy (Bartlett et al., 2010; Quinn & Happell, 2015a, 2015b). Prohibiting sexual activity for patients residing in forensic units hinders the recovery process for several reasons (Tiwana et al., 2016). As deprivation of privacy and restriction on sexual relationships may be relevant factors in relationship failures, policies may be working against the individual well-being of patients (Bartlett et al., 2010). Furthermore, research has shown that strong interpersonal relationships reduce the likelihood of recidivism and improve successful reintegration (Sampson et al., 2006). So, encouraging patients to develop or maintain sustainable relationships may be a useful way to reduce re-offending (De Claire & Dixon, 2017). In a 2004 American study, 60% of responding psychiatric facilities nationwide established sexual polies, 69% provided sex education programs for staff, and 83% offered such programs for inpatients. The authors recommended that these education programs should contain knowledge pertaining to anatomy and physiology, contraception, STD prevention, effects of medication on sexuality, as well as guidance and exercises to improve social and communication skills necessary for building intimate connections with others. Staff members were advised not only to provide condoms but also to offer hands-on demonstrations and training on their use (Dobal & Torkelson, 2004).

The need for a consistent and integrated sexual policy within and across forensic institutions is not only recognized in existing literature but also acknowledged by an expert group working on the development of quality requirements for forensic psychiatric facilities in Flanders (Belgium), considering an integrated institutional policy on sexual expression as an essential part in improving the quality of care (Agency for Care & Health, 2018). This requires not only formation of an overall policy for institutions, but also including sexuality into individual care plans (Bartlett et al., 2010). Moreover, the Brothers of CharityFootnote 1 have included guidelines on relationships and sexuality in mental health care in their ethical framework, which has been in place for more than 20 years (Brothers of Charity, 2000). Despite these developments, it remains unclear how issues of relationships and sexuality are addressed within psychiatric facilities. Moreover, it seems to be a contradictory landscape, not only between different hospital policies but also within rules for individual service users (Bartlett et al., 2010). The absence of clear governance increases the likelihood that staff will rely on their own individual moral judgments and personal beliefs (Bartlett et al., 2010; Völlm et al., 2016). Consequently, the responsibility of decision-making regarding patients’ sexuality is bestowed upon individual institutions and their staff members (Tiwana et al., 2016). Studies on attitudes of caregivers show that sexuality is primarily discussed with a problematic viewpoint (Dein et al., 2016). Mental health workers play an important role in ensuring access to information and promoting a safe and accepting environment for optimal sexual health (Gascoyne et al., 2016). It is the responsibility of management to support staff in feeling more comfortable discussing sex and relationships and provide them with appropriate education to facilitate this process (Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Gascoyne et al., 2016; Di Lorito et al., 2020). Staff education at all professional levels is a crucial part in implementing sexual polices (Di Lorito et al., 2020).

Current Study

Although sexuality is a fundamental human right, research on sexual needs of forensic inpatients is lacking and the topic has been missed off the health agenda (Brand et al., 2021a, 2021b; Tiwana et al., 2016). In general, there is a reluctance by forensic practitioners to explore patients’ perspectives as treatment and management often mostly focus on imminent mental health care needs and the prevention of recidivism according to the RNR model (Bartlett et al., 2010; Huband et al., 2018). Sexuality within forensic psychiatry is frequently approached from a negative perspective and perceived as a risk that needs to be managed (Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Harden, 2014), which is contradictory to the human rights perspective. Especially when it comes to sex offenders within the view of the RNR model, sexuality is approached as a potential risk factor for recidivism due to the nature of the committed offenses (Andrews et al., 1990; Brown et al., 2014; Dein et al., 2016; Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Perlin, 2008; Quinn & Happell, 2015a, 2015b; Seeuws, 2020). However, several studies on long-stay forensic inpatients including sexual offenders indicate the importance of understanding sexual experiences and supporting sexual intimacy in decreasing the risk for potential mental or criminal relapse (Brand et al., 2021a, 2022; Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Huband et al., 2018; Seeuws, 2020). Paying attention to the examination of sexuality and sexual health into standard clinical assessments will contribute to holistic forensic mental health recovery and improved quality of life according to the GLM, which aligns with a sex-positive perspective (Brand et al., 2021a). In general, appropriate approaches to sexuality may differ between individuals, which suggests the desirability of a patient-centered approach. To date, the perspective of patients is not considered in policies on sexuality in forensic psychiatric settings in Belgium. However, their perspective is crucial when reforming policy as it will empower patients in voicing their needs and give them more autonomy within their care and treatment process (Tiwana et al., 2016; Seeuws, 2020). In conclusion, there is an urgent call to explore the sexual needs of forensic inpatients to identify areas where this population can be supported in achieving optimal sexual health (Brand et al., 2022).

Research Questions

Inspired by a sexual health perspective, a human rights perspective, the RNR model and the GLM, this study aims to focus on the following research questions in order to meet the gaps in the literature:

RQ1.What are the key features of current sexual policies in forensic psychiatric facilities, varying from low to high security, in Flanders (Belgium)?

RQ2.What are the experiences of inpatients regarding current sexual policies in forensic psychiatry?

RQ3.What are the unmet sexual wants and needs of inpatients that should be considered when developing an institutional sexual policy?

Method

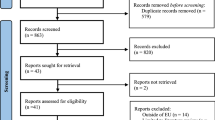

In this study, two different research designs were used in parallel stages, with the intent to form an overall interpretation of the phenomenon (Creswell, 2015): a quantitative approach for answering RQ1 and a qualitative approach for answering RQ2 and RQ3.

Quantitative Approach

Participants

The total population consisted of 40 forensic psychiatric medium and high security units, located within eight different facilities in Flanders (Belgium). Four of these facilities were managed by the Brothers of Charity. Within the population, three wards were specified for sex offenders as well as three wards for individuals with intellectual disabilities. The first author emailed the survey to board members of the facilities, requesting them to forward it to their department heads of forensic psychiatric wards. The final sample consisted of 32 forensic psychiatric units, each represented by their department heads holding a nursing degree. This equates to a response rate of 80% in total. For further information about the background characteristics of the units, we refer to Table 1.

Measures

The online survey (Appendix 1) was developed based upon a review of the literature by the first author. The first page of the survey consisted of an information letter on the study purpose, procedures, participant rights and contact details of the researchers. The department heads also received a no-obligation link to consult the study results. After identifying the background characteristics of the ward, patient demographics, and the existence of hospital-level sexual policies, some statements were used to explore the current (potentially informal) rules and agreements regarding sexuality. Example items include: “Patients/residents are allowed to have a relationship with an external partner” and “Patients/ residents have access to pornographic material within the private sphere of their room.” The items must be answered by “Under no circumstances,” “Under strict conditions,” “Under strict conditions, but not in case of a sex offender,” or “No restrictions.” To the content of existing sexual policies, statements such as “Within the ward, patients/ residents get information on the possible sexual side effects of medication on their sexuality” and “The sexual policy takes into account the committed offenses of patients/ residents” were used. Participants were asked to indicate to what extent the department’s policies agreed with the statements using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 4 (“Strongly disagree”) to 0 (“Totally agree”). Subsequently, the presence and content of current education programs for staff were questioned. Finally, the infrastructure of the bedrooms was explored by asking if patients had a single room and how they meet privacy issues in case of shared rooms. After each set of closed questions, an empty field for additional nuances was available.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using R, with the level of security as the independent variable. For most of the survey descriptive statistics were used to interpret the data. To discover differences between the security levels on the content and application of their sexual policy (cfr. statements on a four-point Likert scale) further statistical analysis was done. After calculating the mean and standard deviation on the statements within each level of security, the two groups were compared using a one-way ANOVA.

Qualitative Approach

Participants

The inpatients were recruited from two units for male internees located within the same psychiatric hospital in Flanders, organized by the Brothers of Charity. The first unit is a closed long-stay ward, categorized as high security according to the FOR-CARE project (Nicaise et al., 2022). It is home to patients without rehabilitation options due to their risk on re-offending. The central goal of this unit is striving for an optimal quality of life. In general, patients are only permitted to leave the ward under permanent escort by staff. The second unit is a forensic psychiatric nursing home classified as medium security (Nicaise et al., 2022). It consists of both open and closed sections where patients reside for a long period of time working on resocialization if indicated. Following the presentation of the research protocol during a patient meeting, a total of 60 patients were invited by the first author to participate. Patients with a lack of decision-making capacity (and thus unable to give informed consent) should be excluded in this study; however, none met these criteria according to the psychiatrists of the units. Initially, there were no questions or reactions on the proposal. When the interviewer positioned herself in a separate room next to the living quarter with the invitation for patients to freely enter and share their experiences, they gradually entered, one by one, to tell their stories. Previous research recommended a minimum sample size of at least 12 participants for qualitative studies to achieve or approach saturation. In case of a heterogeneous population, a larger sample size is needed to approach data saturation (Vasileiou, et al., 2018). A total of 15 white cismen between the age of 40 and 76 participated in this study, all subjected to an internment measure, with eight having committed sexual offenses. Ten respondents resided in a high security ward, while five lived in a medium security unit, with four of them residing in the open section of the ward. The admission duration ranged from 1 week to 7 years, with an average stay of 3.5 years. Participants were asked to describe their sexual orientation, with 12 identifying as heterosexual and three as homosexual. Only one patient was in a relationship at the time of the interview.

Measures and Procedure

As research on the perspective of forensic inpatients on sexual policies is lacking, qualitative research seems the most appropriate method. Data collection utilized a phenomenological approach, well-suited for describing the lived experiences of forensic psychiatric inpatients regarding sexual policies and exploring their wants and needs (Creswell & Poth, 2018). The conducted one-on-one in-depth interviews were semi-structured (Appendix 2), which is recommended for questioning feelings and describing personal experiences, wants and needs of individuals in depth. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines were followed to ensure the reliability of the study (Tong et al., 2007). The interviews were conducted in 2022 by a female criminologist (first author) with experience in interviewing and counseling forensic patients. Although the interviewer worked at another department within the psychiatric hospital, there was no prior relationship with the respondents. The interviews took place in a separate room at the hospital ward, lasted on average 37 min (range, 11–68), and were conducted in Dutch. The interviews started with an introduction followed by questions on respondent’s background characteristics, including year of birth, relationship status, sexual orientation, duration of admission, and whether they had committed sexual offenses. It then continued with questions on the content of the current sexual policy within the ward where they are residing. Subsequently, their satisfaction regarding their sexuality during admission and their unmet sexual wants and needs were questioned. Finally, participants were given the opportunity to provide recommendations regarding the development of an integrated sexual policy and its potential impact on their quality of life. Given the flexibility of the interview-guide, participants could introduce topics relevant to them at any point of the interview. All respondents gave permission to record the interviews on tape to minimize the risk of information distortion during reconstruction. One interview was interrupted by an unexpected family visit and consequently took place in two stages.

Data Analysis

The Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven was used for data analysis (Dierckx de Casterlé et al., 2012, 2021). This guide comprises two stages: a preparatory phase conducted with paper and pencil and an actual coding phase facilitated by qualitative software application NVivo. In the preparatory stage, all interviews were transcribed verbatim as soon as possible after the interviews. The transcriptions were numbered to guarantee the anonymity of the respondents. Audio recordings were securely erased after transcription, and no interviews were repeated. Two researchers (first author and third author) carefully (re)read the transcriptions, identifying meaningful themes and identifying patterns. Afterward, the first author compiled narrative reports for each interview, capturing essential themes and patterns. These reports served as a starting point of the actual coding process. Subsequently, similarities or discrepancies were discussed during regular meetings of the research team in view of creating a coding tree (Appendix 3). Initially, the coding tree was based on the categories of the semi-structured interview guide. As these codes were not exhaustive, additional codes were developed through discussions on the narrative reports and transcripts, consistent with the phenomenological approach. Finally, the transcripts were coded line by line into codes and themes to analyze, interpret and represent the data (Dierckx de Casterlé et al., 2012, 2021).

Results

RQ1. Key Features of Existing Sexual Policies (Quantitative Approach)

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 32 forensic psychiatric units within different psychiatric hospitals in Flanders (Belgium). Characteristics of the study population are shown in detail in Table 1.

Presence of Sexual Policies

In total, 56.3% of the wards had a sexual policy on hospital level, whereof half of them indicated that there were individual differences on the application of the policy between the wards within the hospital. Besides the wards specified for sex offenders, only one high security ward had a separate policy for that population. However, no ward had a separate policy for people with intellectual disabilities.

Rules and Agreements Applied in Practice

The rules and agreements regarding sexuality applied in practice are shown in Table 2.

The results show individual differences in the rules and agreements applied in practice among the wards. For example, in some wards, inpatients can use smartphones or explicit materials such as DVDs or journals in their own room, while in other wards, it was not allowed at all. In general, rules regarding relationships were more restrictive in case of patients from the same ward, while rules were milder on relationships with patients from different wards or external partners. Furthermore, in most of the units visits of prostitutes within the hospital were not allowed in any circumstance, while they were less restrictive on visits of AditiFootnote 2 within the hospital. These trends are similar between the security levels of the units. Except in case of use of internet and smartphones, high security units were less restrictive than medium security units on the use of explicit pornographic materials (e.g., DVD’s or magazines) and/or sex toys in patient’s own room. While in most of the medium security units undisturbed visits in patient’s own room were almost never allowed, most of the high security units agreed under strict conditions or even without restrictions. Subsequently, in most of the medium and high security wards, STD testing and access to contraception were available without restrictions. Finally, hospital departments used a different and more restrictive approach in case of a sex offender. For example, in some wards, inpatients may use smartphones, internet or pornography under strict conditions, but not in case of a sex offender.

Table 3 shows the applicable sexual policy within the different wards. The majority of the medium and high security wards did not conduct psychosexual anamneses for each patient. Furthermore, in 58.8% of the medium security units sexuality was not part of individual treatment plans while most of the high security units (totally) agreed on the statement that sexuality was incorporated in each treatment plan. Most of the medium and high security wards provided information on sexuality in general as well as the impact of psychiatric disorders and medication on sexuality. Most of the medium and high security wards agreed on having a written or non-written sexual policy on ward-level in which they take into account cultural differences, relationship status, sexual orientation, psychiatric disorders and committed offenses of patients. After calculating the mean and standard deviation on the statements within each security level, the two groups were compared using a one-way ANOVA which shows there were no significant differences in the applicable sexual policies between medium and high security levels (F (1, 30) = 2.74, p = 0.108).

Staff Education and Infrastructure

Only three wards (9.6%) had a staff education program on sexuality, whereof in two wards the curriculum consisted of staff guidelines to intervene in case of sexual unacceptable behavior. Furthermore, information provision regarding the effects of psychiatric disorders and medication on sexuality as well as the applicable rules and agreements within the forensic cluster was part of the training program. Additionally, it should be noted that in 25 wards (78.1%) each patient had a single room, while only half of the wards with shared rooms took privacy measures such as curtains or room dividers.

Within the empty field for additional nuances at the end of the survey, two department heads indicated that despite their sexual policy is still under development, decisions were made multidisciplinary on an individual level considering patients’ conditions imposed by the court as well as their criminal history.

RQ2. Experiences of Inpatients Regarding Current Sexual Policies (Qualitative Approach)

None of the respondents were aware of the current sexual policies within the ward, as they have never been discussed. Although they described sexuality as an essential part of their quality of life, rules on sexuality were perceived as very restrictive and sometimes unfair due to individual "ad hoc”-like differences. In some cases, this resulted in secretive paid homosexual contacts with fellow patients or transgressive behavior toward the staff. Respondents reported a lot of obstacles to meet a sexual partner, such as the restrictive living environment, the permanent presence of staff, their juridical conditions, and difficulties discussing their criminal history with future partners.

Starting a relationship will be extremely difficult because I’m here. […] If you live here, you need to tell about your past. […] I’ve closed my mind, that criminal hassle has passed. I’m over it. (P8)

Relationship with fellow patients are usually prohibited by staff. In one case, a patient filed a complaint to the court stating that the hospital had no right to interfere in his wish to establish a relationship with a former patient. The court agreed with him and decided it was not their task to judge on natural things such as love and stated that staff should support patients. However, other patients said they did not want a relationship anymore because of bad experiences in the past. They also felt that establishing a relationship with fellow patients would be a bad idea since people with psychiatric problems should be protected as they may not realize that some forensic patients have committed sexual offenses.

I don’t know if that’s a good idea, except in case of a sensible and assertive person. It’s not like you can start a relationship with someone with a serious intellectual disability. That wouldn’t be correct. (P6)

Furthermore, the possibilities regarding undisturbed visits within the wards were limited as no visitors are allowed in the private rooms due to security measures. After a thorough screening of their partner, patients of the high security ward can use a double bed on the top floor which is only shielded from the table tennis room by a curtain. Respondents of the medium security ward had no alternative options and were forced to look secretively for empty buildings or bushes within the grounds of hospital premises. Moreover, the lack of private and dignified undisturbed visits not only hindered sexuality, but also had an impact on private conversations with friends and family in general. Patients in high security felt restricted in their social contacts because they were not allowed to use smartphones and internet. Most of the respondents had access to pornography in their private room, but they had to ask permission first to staff to download the material in the living room (in case they had no internet access). The use of sex toys was allowed, although incoming mail orders were always checked by staff, which makes it factually unavoidable to discuss such purchases.

On the question whether it is allowed to visit a prostitute, the answers were diverse. Some had an appointment in their own room, while most indicated it was not allowed either in or outside the hospital, maybe due to legal issues or staff may feel uncomfortable accompanying a patient. Especially the respondents without a need for a relationship would like to have the opportunity to visit prostitutes outside the hospital.

My personal supervisor may not have a problem with accompanying me, but for me it is difficult out of respect for my personal supervisor. You’re not going to leave her at the counter in such a special environment. (P1)

Only one respondent was aware of the existence of Aditi. Finally, all the respondents indicated that they were very happy with the medical care services provided by the hospital. They were well aware of the possibilities provided regarding STD testing or purchasing contraception such as condoms.

RQ3. Unmet Sexual Wants and Needs of Inpatients (Qualitative Approach)

Most were dissatisfied with their sexuality due to various barriers in meeting their sexual wants and needs. According to them, the restrictive environment did not encourage sexual expression and made it difficult to discuss such topics. The respondents who committed sexual offenses described an ambiguous relationship with sexuality because it caused them a lot of problems. One respondent described that he never could fulfill his needs because of the prohibition of sexual contact with minors. Another respondent described how he avoids talking about the subject and considers undergoing surgical castration to prevent him from getting into trouble. Besides, other patients described that living together with sex offenders within the psychiatric hospital had an impact on their own sexuality as these people may abuse their transparency on sexuality or cross their boundaries.

The Need for Intimate Connection with Others

According to the respondents, sexuality was not only about making love or self-gratification but also about the need for intimacy, hugs, kisses, affection, fondness, and intimate connection with others. In general, the described ways of fulfilling those needs were individually different. Sexuality was described as an emotional process that fits within a sustainable and stable relationship. According to them, those relationships must be encouraged as they can support patients and prevent relapse. From this reasoning, one patient suggested that an individual relationship therapist, who works independently from the ward, might be a good idea to support patients in their relationships. Meeting a potential partner was difficult because of the background check requested by staff in order to ensure their prosocial and supportive impact on the inpatient. This screening was experienced as an interrogation and was seen as very intrusive as private topics were discussed, without any relationship of trust, which could discourage potential partners.

Other respondents indicated that they could even fulfill their needs by being able to hug caregivers or receive visits from friends or family within a private environment. All the high security respondents preferred to purchase a smartphone with internet access instead of their old cell phone in order to be able to video chat with friends and family. However, it must be noted that, of those who committed sexual offenses, three respondents were banned by their supervisors from using the internet at the moment of the interview in anticipation of the court hearing due to violation of their juridical conditions.

The Need for Privacy

Most patients mentioned privacy issues within the wards. Although all had a single room and entering another room was prohibited, some patients were disturbed by other patients while calling friends or family. In general, all patients described their wish for undisturbed visits, but the opinions diverged on whether these visits should take place in their own room or within a separate conjugal visit room. On the one hand, they would like to invite friends and family into their room for having private conversations. On the other hand, their own room seems to be unsuitable for making love due to the lack of comfort as well as the size and sound density of the room. In that case, a cozy decorated conjugal visit room with bathroom facilities would be more appropriate.

The walls are made of cardboard. If you have sex, the whole corridor can hear it. (P6)

Furthermore, during the night shift each room is subject to control for safety reasons, but it is unpredictable at what time supervisors will do their check-up. Patients indicated that caregivers always knock on the door before entering the room, but when they do not respond right away, they will immediately grab their key. When the interviewer suggested to use a sign with “please do not disturb,” respondents indicated it would be even more embarrassing. Finally, some respondents described the importance of informing prostitutes about the criminal history of patients due to safety reasons. However, other patients indicated this would be in breach of their privacy. For one respondent, this is one of the arguments to refuse Aditi because he suspected that they have a record of their customers.

The Need for Information

All patients experienced sexuality as a taboo and seldom discussed unless in case of incidents. If patients wished to discuss it, they had to initiate the conversation themselves. Moreover, several patients had experienced serious breaches by caregivers, which hindered discussing sensitive topics such as sexuality. For instance, their sexual needs were not taken seriously, the purchase of sex toys was ridiculed, and confidential talks were passed on. In general, inpatients experienced a feeling of lacking respect, sensitivity, and care.

It was humiliating to go to the doctor asking for medication because of erectile dysfunctions. While asking my supervisor to make an appointment, the whole nursing station was laughing. (P12)

These violations have a significant detrimental impact on their trust in healthcare providers regarding sexuality matters. Despite this, they express the need for more individualized information on how to fulfill their sexual needs, meet a sexual partner, use sex toys, or obtain information on organizations such as Aditi.

The Need for Policy

In conclusion, all participants indicated the need for a clear institutional policy but felt some restraint by the management. One patient questioned whether this restraint is driven by shame toward society. They cautioned against universal, overarching rules arguing that the forensic population is very heterogeneous. According to them, sexual policies should be adaptable to each individual situation, but the broader picture should be clear. Nevertheless, respondents felt that prohibiting sexual expression would lead to secretive behavior and frustrations and ultimately criminal relapse. Furthermore, according to one respondent, an institutional sexual policy should also include dress code rules for staff and trainees as inappropriate dressing could provoke sexual transgressive behavior. In summary, all patients unanimously agreed that their quality of life would increase, stress would be reduced, and their stay would be even more comfortable if management would consider their suggestions in the development of a sexual policy.

Discussion

As already stated in previous research (Bartlett et al., 2010; Tiwana et al., 2016), Belgium lacks a national policy on sexuality for forensic inpatients, leaving management decisions in the hands of individual hospitals. Only 56% of forensic wards in Flanders had institutional sexual policies at the hospital level, consistent with existing literature (Dobal & Torkelson, 2004). None of the interviewed patients were aware of the applicable sexual policy within the ward where they resided. Overall, differences and inconsistencies on the applicable rules and agreements between individual wards were indicated, but there were no significant differences in sexual policies between medium and high security levels, without explanations in international literature for this outcome. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that there is just one long-stay unit without short-term resocialization options in Flanders, resulting in a significant number of internees residing in high security units. Accordingly, some interviewed respondents experienced the applicable sexual policy as unfair due to varying decisions between patients. However, others indicated that implementing universal rules can be hazardous due to the diverse nature of the population. In their opinion sexual policies may differ between patients and should be adaptable to each individual situation while ensuring clarity in overarching principles, which is in line with a patient-centered approach (Bartlett et al., 2010).

Survey findings as well as experiences of the respondents confirm that many of the rules applied in practice were decisive into what would normally be considered as private situations within broader society, such as engaging in relationships, visits of prostitutes and the use of smartphones and internet (Bartlett et al., 2010). Results of this study demonstrate that compared to other European countries, the sexual policy in Flanders, Belgium, is rather restrictive in nature (Tiwana et al., 2016). Respondents felt that prohibiting sexual expression would lead to secretive behavior and frustrations and ultimately criminal relapse. Whether or not a policy forbids it, sexual behavior occurs, and forensic inpatients continue to have sexual needs and will search for other gateways, such as secretive behavior, homosexual contacts with fellow patients, or transgressive behavior toward the staff (Bartlett et al., 2010; Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Quinn and Happel, 2015a, 2015b, 2016). In general, policies regarding relationships were more restrictive when patients from the same ward are involved, while rules were milder on relationships with patients from different wards or external partners. Furthermore, in most of the wards, visits of prostitutes within the hospital were not allowed in any circumstances, which can be explained due to the lack of a legal framework. Psychiatric facilities are subjected to the Belgian Penal Code in which sex legislation was a legal gray area at the time of the study. Certain related activities such as exploitation of a house of fornication or pimping were illegal. Consequently, allowing prostitutes inside the hospital, facilitating visits to prostitutes, or working together with Aditi could be considered unlawful (art. 380 Sw.). Besides, survey results indicated that STD testing and access to contraception were available without restrictions. Accordingly, all interviewed respondents expressed that they were very happy with the medical care services provided by the hospital including possibilities regarding STD testing and the availability of contraception. Finally, it is remarkable that hospital departments used a different policy in case of a sex offender even though they are subjected to the same national and international human rights standards. This can be explained by the nature of the committed offenses or restrictions related to the court (Brown et al., 2014; Dein et al., 2016; Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Perlin, 2008; Quinn & Happell, 2015a, 2015b).

Consistent with existing literature, most of the respondents were unsatisfied with their sexuality due to various barriers in meeting their sexual wants and needs within an environment that does not encourage sexual expression (Dein et al., 2016; Schel et al., 2015). The described sexual needs were individually different, and sexuality was not only about making love or self-gratification but the need for intimacy, hugs, kisses, affection, fondness, and intimate connection with others. In line with the recovery-based approach of the GLM (Brand et al., 2021a; Huband et al., 2018; Seeuws, 2020; Ward & Fortune, 2013; WHO, 2010), respondents indicated that sexual expression and relationships must be supported as it will increase their quality of life, support them in hard times and prevent them from mental or criminal relapse. However, they experienced a lot of obstacles in meeting a sexual partner, including the restrictive living environment, their internment measure and its associated juridical conditions, their criminal history and the perpetual supervision of staff when leaving the ward. As described by Dein et al. (2016), the results of our study confirmed that residing in forensic facilities limits the actual opportunities of inpatients and their partners to utilize their rights to respect for a private life, family life and the possibility to start a family, which can be in breach with Article 8 of the ECHR. It must be marked that not all patients had a need for a relationship because of negative experiences in the past. In addition, some of the respondents would like to have the opportunity to visit prostitutes and to use their smartphone and internet within their own room to communicate with friends and family.

In line with previous research, patients stated that restrictive rules forbidding sexual expression harm individuals in developing a qualitative life, work against individual’s well-being and hinder the recovery process (Bartlett et al., 2010; Tiwana et al., 2016). Even though paying attention to the examination of sexuality and sexual health into standard clinical assessments will contribute to holistic forensic mental health recovery and quality of life (Brand et al., 2021a), most wards did not conduct psychosexual anamneses for each patient and sexuality was not consistently incorporated in treatment plans. Although most of the wards indicated to provide information on sexuality, patients indicated the topic remained taboo except in case of incidents, aligning with previous findings on staff attitudes (Dein et al., 2016; Quinn & Happell, 2015a, 2015b). Besides, several patients experienced serious breaches by caregivers that still have a major detrimental impact on their trust in healthcare providers, hindering discussions on sensitive topics like sexuality. Many respondents expressed a need for providing information on possible ways to fulfill their sexual needs within one-on-one contact as they experienced insufficient safety to talk about sexuality within group settings. Moreover, it must be noticed that only half of the wards with shared rooms took privacy measures such as curtains or room dividers. Also, the interviews indicated several privacy issues within the wards. The absence on undisturbed visits was not only unpleasant in terms of making love but also hinders patients in having private conversations with friends and family. These results confirm mental health professionals have an important role in ensuring access to information and creating a safe environment wherein sex education is necessary to prepare inpatients for resocialization (Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Gascoyne et al., 2016; Quinn & Happell, 2015a, 2015b). Although staff education is a crucial component in sexual policy implementation (Di Lorito et al., 2020; Dobal & Torkelson, 2004; Gascoyne et al., 2016), only 9.6% of the wards had a staff education program on sexuality.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, there is a need for an integrated and clear institutional sexual policy that supports psychiatric facilities in the field of tension between improving the quality of life of inpatients by meeting their sexual wants and needs on the one hand and following the law on the other. As patients can be placed involuntary within psychiatric institutions, it is recommended to create a sexual policy on national level to avoid individual differences and inconsistencies on the applicable rules and agreements between the hospitals. However, given the heterogeneousness of the forensic population, sexual policies should consider individual’s psychiatric vulnerability and criminal history. This suggests that appropriate approaches to sexual and emotional relationships may differ between individual patients, which implies the desirability of a patient-centered approach. Consequently, sexuality should be part of each treatment plan with attention to relapse prevention, individual well-being, and quality of life. The sexual needs of forensic inpatients differ and cannot be reduced to making love or self-gratification. In general, patients have a need for intimate connection with others. Consensual, sustainable and stable relationships can be seen as a human right and must be encouraged as prosocial contacts can prevent forensic patients from relapse. In line, it is recommended to offer a systemic therapist to support this process. In addition, the policy on the use of smartphones and internet should be proportional and present-day as a total ban hinders connection with others in our modern society. Furthermore, the reform of Belgian sexual criminal law in June 2022 is a positive development since sex work is decriminalized and psychiatric facilities are no longer operating in a legal gray area when accommodating sex workers, arranging visits to prostitutes, or collaborating with organizations like Aditi (Federal Public Service of Justice, 2023). Also, the updated ethical advice from the Brothers of Charity, which recognizes sexuality as a valuable dimension of life, is a step in the right direction (Brothers of Charity, 2023).

Besides, multiple privacy issues indicated the need for privacy in a physical and psychological way. To overcome these issues, it is recommended to create a private room for undisturbed visits and renew the infrastructure to create single rooms with soundproof walls. Subsequently, it is important to give inpatients the opportunity to indicate their need for privacy when caregivers knock on their door before grabbing their key for entering the room. In addition, rules on entering each other’s room should be clear and patients should have a person of trust to discuss sensitive topics. Moreover, there is a need for information and sex education. Information should be given one-on-one at the initiative of the caregiver and should contain psychoeducation on the influence of medication and psychiatric disorders on sexuality and potential risks such as STDs. Although nearly half of the interviewed patients were sex offenders, sexuality was still considered as taboo. Nonetheless, according to GLM, the presence of deviant sexual interests suggests necessary conditions required for healthy sexuality and relationships are missing or distorted in some way, such as knowledge on appropriate sexual practices or concerns regarding intimacy (Ward & Stewart, 2003). Therefore, addressing sexuality in general as well as sexuality as a potential risk factor should be an essential part of the treatment program. Furthermore, inpatients should receive information on possible ways to fulfill their sexual needs as well as information on the applicable rules and agreements within the ward. It is the responsibility of management to support caregivers to feel more comfortable in talking about these topics by providing an educational program. Finally, staff education is a crucial component in sexual policy implementation to avoid that decision making around patients’ sexuality will be guided by moral judgments and personal beliefs of individual staff.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study questioning forensic psychiatric facilities in Flanders (Belgium) on the existence and content of sexual policies. Moreover, this is the first study exploring the perspective of forensic inpatients themselves in current sexual policies and their unmet sexual wants and needs (Brand et al., 2021a, 2021b; Tiwana et al., 2016). Describing patients’ experiences in an empirical study gives them more autonomy, enhances their voice and provides new insights for policy makers, both on a national and institutional scale. To ensure trustworthiness of the findings, the following strategies were applied: (1) researcher triangulation: data analysis are performed by two researchers; (2) peer review: regular meetings with the research team to discuss the data and review the analysis; and (3) peer debriefings: frequent debriefings with external people with experience in policy making within forensic psychiatry.

However, the limitations of this study should not be ignored. As there is much going on about the topic of this study, the results of the surveys form only a snapshot of the current situation. As only categorized forensic psychiatric medium and high security units in Flanders have been questioned, the quantitative analyses cannot be generalized to lower security levels or to Belgium in general. Also, the authors did not define ‘sexuality’ as a concept in the introduction of the survey and did not check before sending out the questionnaire how sexuality was understood by the participants, which is a limitation of the quantitative part of the study. In addition, interviewer effects such as characteristics of the interviewer and the interpersonal interaction between the researcher and the respondents during the interviews may have influenced the responses. Through non-verbal signals and leading questions, the interviewer may have nudged the participants in a certain direction. Besides, sexuality is a sensitive topic which may hinder respondents to speak about their wants and needs with an unfamiliar researcher. Incidentally, there were factors that disrupted the interviews, such as background noise or an unexpected visit from a family member which forced to pause the interview. Furthermore, the transcripts of the interviews and research findings were not returned to the participants for corrections or feedback, although it would add validity to the researcher’s interpretations. Although data saturation has been reached, this study focuses on narratives of a heterogeneous population with individual wants and needs. As suggested by Levitt (2021), it has been indicated how and when findings vary. It is noteworthy that this study exclusively included cisgender white male patients, potentially introducing bias into the results. Consequently, these findings may not be applicable to non-Western cultures or female patients. Since experiences related to sexual policy may vary depending on the treatment center, future qualitative studies should encompass multiple healthcare facilities, with due consideration for gender and criminal history, and should include both treatment and long-stay units. Finally, collecting and analyzing the documents of actual sexual policies can add value to future research.

Availability of data and material/ code availability

Available upon request.

Notes

The Brothers of Charity are an international religious congregation with a strong commitment to the organization of mental health care in Belgium and worldwide.

In 2008, a non-profit organization named “Aditi” was established. Besides providing advice and information, Aditi is an authorized healthcare provider for sexual services for the elderly or patients with intellectual disabilities and psychiatric disorders.

References

Agency for Care and Health. (2018). Referentiekader forensische geestelijke gezondheidszorg. https://www.zorg-en-gezondheid.be/referentiekader-forensische-geestelijke-gezondheidszorg

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for Effective Rehabilitation: Rediscovering Psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17(1), 19–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854890017001004

Barnao, M., Ward, T., & Robertson, P. (2016). The Good Lives Model: A new paradigm for forensic mental health. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(2), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2015.1054923

Bartlett, P., Mantovani, N., Cratsley, K., Dillon, C., & Eastman, N. (2010). “You may kiss the bride, but you may not open your mouth when you do so”: Policies concerning sex, marriage and relationships in English forensic psychiatric facilities. Liverpool Law Review, 31(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10991-010-9078-5

Belgian Penal Code, Pub. L. No. 1867060850, Belgisch Staatsblad 3133 (1867). http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=N&table_name=wet&cn=1867060801

Brand, E., Ratsch, A., & Heffernan, E. (2021a). Case Report: The sexual experiences of forensic mental health patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 651834. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.651834

Brand, E., Ratsch, A., & Heffernan, E. (2021b). The sexual development, sexual health, sexual experiences, and sexual knowledge of forensic mental health patients: A research design and methodology protocol. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 651839. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.651839

Brand, E., Ratsch, A., Nagaraj, D., & Heffernan, E. (2022). The sexuality and sexual experiences of forensic mental health patients: An integrative review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 975577. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.975577

Brothers of Charity. (2000). Ethical advice: Relationships and sexuality in mental health care. https://broedersvanliefde.be/artikel/ethisch-advies-relaties-en-seksualiteit-de-geestelijke-gezondheidszorg

Brothers of Charity. (2023). Ethical advice: Ethical approach to sexuality in mental healthcare clients. https://broedersvanliefde.be/artikel/ethisch-omgaan-met-seksualiteit-bij-clienten-de-geestelijke-gezondheidszorg

Brown, S. D., Reavey, P., Kanyeredzi, A., & Batty, R. (2014). Transformations of self and sexuality: Psychologically modified experiences in the context of forensic mental health. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 18(3), 240–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459313497606

Creswell, J. W. (2015). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (Fourth edition). SAGE.

De Claire, K., & Dixon, L. (2017). The effects of prison visits from family members on prisoners’ well-being, prison rule breaking, and recidivism: A review of research since 1991. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 18(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015603209

Dein, K. E., Williams, P. S., Volkonskaia, I., Kanyeredzi, A., Reavey, P., & Leavey, G. (2016). Examining professionals’ perspectives on sexuality for service users of a forensic psychiatry unit. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 44, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.08.027

Di Lorito, C., Tore, M., Wernli Kaufmann, R. A., Needham, I., & Völlm, B. (2020). Staff views around sexual expression in forensic psychiatric settings: A comparison study between United Kingdom and German-speaking countries. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 31(2), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2019.1707264

Dierckx de Casterlé, B., Gastmans, C., Bryon, E., & Denier, Y. (2012). QUAGOL: A guide for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(3), 360–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.012

Dierckx De Casterlé, B., De Vliegher, K., Gastmans, C., & Mertens, E. (2021). Complex qualitative data analysis: Lessons learned from the experiences with the Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven. Qualitative Health Research, 31(6), 1083–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320966981

Dobal, M. T., & Torkelson, D. J. (2004). Making decisions about sexual rights in psychiatric facilities. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 18(2), 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.apnu.2004.01.005

Federal Public Service of Justice. (2023). Sekswerk. Geraadpleegd 16 oktober 2023, van https://justitie.belgium.be/nl/themas/veiligheid_en_criminaliteit/sekswerk

Gascoyne, S., Hughes, E., McCann, E., & Quinn, C. (2016). The sexual health and relationship needs of people with severe mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(5), 338–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12317

Huband, N., Furtado, V., Schel, S., Eckert, M., Cheung, N., Bulten, E., & Völlm, B. (2018). Characteristics and needs of long-stay forensic psychiatric inpatients: A rapid review of the literature. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 17(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2017.1405124

Jeandarme, I., Saloppé, X., Habets, P., & Pham, T. H. (2019). Not guilty by reason of insanity: Clinical and judicial profile of medium and high security patients in Belgium. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 30(2), 286–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2018.1544265

Jeandarme, I., Goktas, G., Boucké, J., Dekkers, I., De Boel, L., & Verbeke, G. (2022). High security settings in Flanders: An analysis of discharged and long-term forensic psychiatric patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 826406. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.826406

Kennedy, H. G. (2002). Therapeutic uses of security: Mapping forensic mental health services by stratifying risk. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8(6), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.8.6.433

Levitt, H. M. (2021). Qualitative generalization, not to the population but to the phenomenon: Reconceptualizing variation in qualitative research. Qualitative Psychology, 8(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000184

Nicaise, P., Lorant, V., Bourmorck, D., Vander Laenen, F., Vanderplasschen, W., De Pau, M., Rowaert, S., Mertens, A., Leys, M., Schoenaers, F., and Darcis, C. (2022). FOR-CARE project 2016–2019: A “realist evaluation” of a reform programme in a multisectoral framework. Final Report.. UCLL, UGent, VUB, ULiège.

Perlin, M. (2008). “Everybody is making love/or else expecting rain”: Considering the sexual autonomy rights of persons institutionalized because of mental disability in forensic hospitals and in Asia. Washington Law Review, 83(4), 481–512.

Quinn, C., & Happell, B. (2015a). Sex on show. Issues of privacy and dignity in a forensic mental health hospital: Nurse and patient views. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 2268–2276. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12860

Quinn, C., & Happell, B. (2015b). Exploring sexual risks in a forensic mental health hospital: Perspectives from patients and nurses. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(9), 669–677. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1033042

Quinn, C., & Happell, B. (2016). Supporting the sexual intimacy needs of patients in a longer stay inpatient forensic setting. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 52(4), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12123

Sampson, R. J., Laub, J. H., & Wimer, C. (2006). Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-individual causal effects. Criminology, 44(3), 465–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00055.x

Schel, S. H. H., Bouman, Y. H. A., & Bulten, B. H. (2015). Quality of life in long-term forensic psychiatric care: Comparison of self-report and proxy assessments. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(3), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.01.004

Seeuws, J. (2020). Visie en beleid rond seksualiteitsbeleving: Een blinde vlek in de behandeling van plegers van zedenfeiten? Dissertation, University of Antwerp, Ghent University, University of Brussels, Catholic University of Leuven. https://jantienseeuws.com/publicaties/

Seynnaeve, K., Goyens, M., Eens, I., & Dheedene, J. (2023). Internering: Recht op zorg? Panopticon, 6, 382–403.

Taylor, E., & Whiting, D. (2022). Is the prohibitive stance on sex and relationships in the UK forensic system justifiable? Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 33(5), 780–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2022.2115937

Tiwana, R., McDonald, S., & Völlm, B. (2016). Policies on sexual expression in forensic psychiatric settings in different European countries. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0037-y

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Vander Beken, T. (2017). De nieuwe interneringswetgeving. In P. Traest, A. Verhage, & G. Vermeulen (Eds.), Strafrecht en strafprocesrecht: Doel of middel in een veranderende samenleving? (pp. 341–403). Wolters Kluwer.

Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

Völlm, B., Bartlett, P., & McDonald, R. (2016). Ethical issues of long-term forensic psychiatric care. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 2(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2016.01.005

Ward, T., & Fortune, C.-A. (2013). The Good Lives Model: Aligning risk reduction with promoting offenders’ personal goals. European Journal of Probation, 5(2), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/206622031300500203

Ward, T., & Stewart, C. A. (2003). The treatment of sex offenders: Risk management and good lives. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.34.4.353

World Health Organization. (2010). Measuring sexual health: Conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-10.12

World Health Organization. (2015). Sexual health, human rights and the law. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564984

Funding

The authors received some financial support from the scientific research fund of the Brothers of Charity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Methodology, data collection and analyses were performed by Lena Boons under supervision of Inge Jeandarme and Yvonne Denier. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lena boons, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Compliance with ethical standards

In February-March 2022, ethical approval was obtained by the Ethics Committee Research UZ/ KU Leuven (S66386), by the ethical committee of Brothers of Charity (0G054-2021-048), and by the local ethical committees of participating psychiatric hospitals in this study. According to the qualitative part of this research, all respondents were given the opportunity to ask questions before signing the informed consent form indicating that they agreed to be part of this study. It was made clear to all respondents, both verbal and in writing, that there were no sanctions or consequences for their treatment when they should decide not to participate in this study or to withdraw at any point.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Online Survey

-

Background Information

-

How would you describe the department where you work? Multiple answer categories are possible.

-

Crisis unit/ admission unit

-

Treatment unit

-

Resocialization unit

-

Forensic psychiatric care facility

-

Long stay

-

-

Within which security level would you position the department where you work?

-

High security

-

Medium security – specialized program for sexual offenders

-

Medium security

-

Low security

-

Regular psychiatric unit

-

Don’t know

-

-

Are individuals who committed sexual offenses admitted to the department where you work?

-

No

-

Yes

-

-

Are individuals with intellectual disabilities admitted to the department where you work?

-

No

-

Yes

-

-

-

Sexual Policy within the Institution

-

Is there a written sexual policy within the institution where you work?

-

No, there is no written sexual policy within the institution. (Go to question 2.4)

-

Yes, there is a uniform sexual policy within the institution for all department (including non-forensic departments) (Go to question 2.3)

-

Yes, there is a sexual policy within the institution, but there are differences between the departments (Go to question 2.3)

-

-

Is there a separate sexual policy on your department for patients committed sexual offenses?

-

Yes

-

No

-

-

Is there a separate sexual policy on your department for patients with intellectual disabilities?

-

Yes

-

No

-

-

What agreements are in place regarding sexuality on the department where you work?

-

Under no circumstances | Under strict conditions | Under strict conditions, but not in case of a sex offender | No restrictions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Patients/residents staying on the same department are allowed to engage in a sexual relationship with each other | ||||

Patients/residents staying on different departments are allowed to engage in a sexual relationship with each other | ||||

Patients/residents are allowed to have a relationship with an external partner | ||||

It is allowed for patients/residents to receive a prostitute within the institution | ||||

Patients/residents are allowed to consult a prostitute outside the institution | ||||

It is allowed for patients/residents to receive a sexual service provider (e.g., Aditi n.p.o.) within the institution | ||||

Patients/residents are allowed to consult a sexual service provider (e.g., Aditi n.p.o.) outside the institution | ||||

Patients/residents can request explicit material to use within the privacy of their rooms (e.g., DVDs, magazines) | ||||

Patients/residents can use a smartphone within the privacy of their rooms | ||||

Patients/residents have access to internet within the privacy of their rooms | ||||

Patients have access to pornographic material within the private sphere of their room | ||||

Patients/residents are allowed to use sexual tools and toys | ||||

Patients/residents can undergo STD testing | ||||

Patients/residents have access to contraception (e.g., condoms) |

-

Wants and Needs of Forensic Patients

-

To what extent does the policy on the department where you work agree with the following statements? Choose from the following answer categories.

-

Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Totally agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

For each patient/resident, a psychosexual anamnesis is conducted | ||||

Sexuality is an integral part of the treatment plan/care plan | ||||

The organization provides written information for patients/residents regarding sexuality | ||||

Within the ward, patients/residents get information on the possible effects of their mental condition on their sexuality | ||||

Within the ward, patients/residents get information on the possible sexual side effects of medication on their sexuality | ||||

The sexual policy takes into account diverse cultural backgrounds and religious preferences of patients/residents | ||||

The sexual policy takes into account the relationship status of patients/residents | ||||

The sexual policy takes into account the sexual orientation of patients/residents | ||||

The sexual policy takes into account the psychiatric vulnerability of patients/residents | ||||

The sexual policy takes into account the committed offenses patients/residents |

-

Training and Education of Staff

-

Are training sessions regarding sexuality provided for staff?

-

Yes (Go to question 4.2)

-

No (Go to question 4.3)

-

-

What training sessions are provided? Please select all that apply, multiple answers are possible.

-

Managing sexually inappropriate behavior.

-

The impact of various psychiatric conditions on sexuality.

-

Sexual health, including sexually transmitted diseases and safe sex.

-

The specific side effects of certain medications on sexuality.

-

Guidelines from the organization for staff regarding acceptable/inappropriate expressions of sexual behavior in patients/residents (e.g., masturbating in the room versus in public).

-

Other, namely: …

-

-

Is there a protocol available for addressing incidents of sexually inappropriate behavior involving patients and staff?

-

Yes

-

No

-

-

Is there a protocol available for addressing incidents of sexually inappropriate behavior between patients themselves?

-

Yes

-

No

-

-

-

Information for Family Members

-

To what extent does the policy on the department where you work agree with the following statements? Choose from the following answer categories.

-

Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Totally agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Partners can seek assistance within the institution for questions regarding sexuality | ||||

Partners are informed about the impact of psychiatric conditions on sexuality | ||||

Partners are informed about the impact of medication on sexuality | ||||

Written information (e.g., books, protocols, guidelines) is provided to inform family members about the expression of sexuality within the institution |

-

Physical Environment

-

Do patients/residents on your department stay in single rooms?

-

Yes, everyone stays in a single room.

-

No, only specific patients/residents have a single room.

-

No, there are no single rooms available.

-

-

How is the policy implemented on the department where you work?

-

Under no circumstances | Under strict conditions | Under strict conditions, but not in case of a sex offender | No restrictions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

The institution provides private spaces for patients/residents within the ward | ||||

The institution provides a room for undisturbed visits | ||||

Privacy measures are taken for patients/residents who share a room (e.g., curtain, divider) |

-

End

Thank you very much for participating in this survey. If you would like to clarify or add anything, please feel free to do so in the space provided below. You can access the results of this study via the following link after its completion.

Appendix 2: Interview Guideline

Introduction

See informed consent.

Personal Characteristics

Before we proceed with the actual questions, I would like to inquire about some general information. We process these data in such a way that your identity can never be traced.

Open questions:

-

Year of birth

-

Relationship status

-

Sexual orientation

-

Unit

-

Duration of stay

-

Internment measure for sexual offenses

Sexual Policy

-

What rules and agreements apply to sexuality in the ward where you reside?

-

To what extent is it allowed to have a relationship (with another patient)?

-

To what extent are you allowed to use a smartphone?

-

To what extent do you have access to the internet?

-

To what extent do you have access to pornographic material?

-

To what extent do you have the opportunity to use explicit material in the privacy of your room (e.g., DVDs, magazines, etc.)?

-

To what extent is it allowed to have intimate contact within/outside the ward?

-

To what extent do you have access to the services of a prostitute?

-

To what extent do you have access to the services of sexual service providers (such as Aditi vzw)?

-

To what extent are you allowed to use sexual aids and sex toys?

-

To what extent do you have the opportunity to get tested for STDs?

-

To what extent do you have access to contraception such as condoms?

-

-

To what extent does the current sexuality policy take into account your wants and needs?

-

Age

-

Ethnicity

-

Religion

-

Relationship status

-

Sexual orientation

-

Psychological vulnerability

-

Duration of stay

-

Committed offense(s)

-

Impact Residential Admission

-

To what extent are you satisfied with your sexual life?

-

How do you experience your sexuality since your admission?

-

-

To what extent has your admission impacted your sexual life?

-

Rules and agreements

-

Privacy

-

Psychological vulnerability

-

Medication (also inquire about the medication being taken)

-

Committed offenses

-

Wants and Needs Sexual Policy

-

How should the sexuality policy within the ward where you reside look according to you?

-

To what extent should adjustments be made to the existing rules and agreements to meet your wants and needs regarding sexuality?

-

To what extent should adjustments be made to the physical environment to meet your wants and needs regarding sexuality?

-

Single rooms

-

Privacy measures (curtains/dividers/etc.)

-

Private spaces in the ward

-

Room for undisturbed visits

-

-

To what extent should adjustments be made to the existing rules and agreements to meet the wants and needs of your partner regarding sexuality?

-

To what extent do you receive sufficient information about sexuality?

-

-

To what extent do you receive sufficient information about the impact of your psychological vulnerability on your sexual life?

-

To what extent do you receive sufficient information about the medication you take on your sexual life?

-

To what extent is the topic of sexuality discussed in the ward?

-

To what extent can you approach the staff with questions about sexuality?

-

-

To what extent does your partner receive sufficient information about sexuality?

-

To what extent does your partner receive sufficient information about the impact of your psychological vulnerability on your sexual life?

-