Abstract

Sexual and romantic orientations are often considered one and the same, and attitudes about engaging in sexual behavior are assumed to be predominantly positive. The current study explored the concordance between sexual and romantic orientations among allosexual and asexual adults as well as the frequency with which they identify as having a sex-positive, sex-neutral, or sex-averse attitude. As expected, allosexual adults were largely sex-positive (82%) and almost all (89%) had a romantic orientation that matched their sexual orientation. In contrast, we found that only 37% of asexual adults had concordant sexual and romantic orientations and that most asexual adults self-identify as either sex-neutral (41%) or sex-averse (54%). Further, we used a semantic differential task to assess sexual intimacy attitudes and how they varied for adults based on sexual attitude. Asexual adults, regardless of sexual attitude, had less positive attitudes overall than allosexual adults. Interestingly, aromantic asexual adults did not have more negative attitudes about sexual intimacy than romantic asexual participants. Although asexual adults held less positive attitudes about sex than allosexual adults, there was considerable heterogeneity within our asexual sample. The current study provides further insight into the concordance between romantic and sexual orientation, and the associations among sexual and intimacy attitudes for both allosexual and asexual adults. These findings will have implications for future research on how asexual adults navigate romantic relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Asexuality has become a recognized sexual orientation and topic of research interest in several disciplines (e.g., Bogaert, 2015), yet less is known about how asexual people identify romantically, or what attitudes asexual people hold about engaging in sex, especially in comparison to allosexual individuals. Within the allosexual population (e.g., heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual, pansexual), sexual and romantic orientations are often considered one and the same (Diamond, 2003; Thompson & Morgan, 2008), and personal attitudes about engaging in sexual behavior are assumed to be predominantly positive. However, as researchers are only beginning to document the variability within the asexual population, there is a need for research that addresses the concordance between sexual and romantic orientations for asexual people and how they negotiate aspects of sexuality and romantic partner relationships.

Someone who identifies as asexual typically experiences a lack of sexual attraction in a manner that is distinct from individuals who experience hypoactive sexual desire disorder (Bogaert, 2015; Brotto et al., 2015; Decker, 2015). Asexuality is considered a valid sexual orientation (Brotto & Yule, 2017), and asexual people experience a wealth of richly heterogeneous relationship experiences (e.g., Haefner, 2012). Bogaert (2004) first used the term asexuality to describe someone who did not experience sexual attraction, and asexuality is now conceptualized as a spectrum or an “umbrella” term (Carrigan, 2011; Przybylo, 2016). The asexuality spectrum includes identities such as gray-A (a person whose experience of sexual attraction falls between asexual and sexual), demisexual (a person who only experiences sexual attraction after forming a deep, emotional bond), and A-fluid identities (a person whose experience of sexual attraction is fluid; Carrigan, 2011; Przybylo, 2016). Common definitions of identity labels shift with time and individual usage, again highlighting the heterogeneous experiences of asexual individuals (Vares, 2018).

Previous research comparing allosexual and asexual adults has examined physiological characteristics (Bogaert, 2004, 2015) and psychological measures (Borgogna et al., 2019; Carvalho et al., 2017). Additionally, researchers examining solely asexual samples have studied romantic relationship navigation (Carrigan, 2012; Haefner, 2012; Scherrer, 2010), coming-out (Robbins et al., 2016; Van Houdenhove et al., 2015b), and sexual experiences (Carrigan, 2012; Dawson et al., 2016; Prause & Graham, 2007). Yet, few studies have compared more nuanced aspects of sexuality among allosexual and asexual adults, such as romantic orientation or attitudes about engaging in sex, which may differentially influence how asexual and allosexual adults navigate engaging in sexual behaviors or romantic partner relationships (Antonsen et al., 2020; Carrigan, 2011; Lund et al., 2016).

A person’s romantic orientation can be defined as whom they experience romantic attraction toward and is considered distinct from sexual orientation (Diamond, 2003). However, romantic and sexual orientations are commonly expected or assumed to be concordant, despite evidence that these constructs are separate (Diamond, 2003; Thompson & Morgan, 2008). For example, someone who identifies as heterosexual is expected to be romantically attracted exclusively to those of the opposite sex. In one of the few studies to examine concordance rates, Lund et al. (2016) compared adults’ sexual and romantic attractions and found that 89.4% of adults reported concordant sexual and romantic attractions. However, Lund et al. did not allow participants to self-identify with a specific romantic or sexual orientation label; rather, participants had to select romantic and sexual attraction based on sex using a list of provided categories (e.g., opposite-sex, same-sex). It is an open question what the concordance rates would be if participants were allowed to self-identify, although concordance rates for allosexual adults would be expected to be high.

In contrast, asexual adults are more likely to experience discordant romantic and sexual orientations. Many asexual people identify as having a romantic orientation such as heteroromantic, homoromantic, or biromantic, in comparison with what would be considered a concordant romantic orientation (i.e., aromantic; Brotto et al., 2010; Chasin, 2011; Ginoza et al., 2014). For example, the Asexuality Visibility and Education Network (AVEN, 2017) conducted a large-scale community census of asexual people and found that only 19% identified as aromantic (Ginoza et al., 2014). Discordant romantic and sexual orientations were more common; 81% identified with a romantic orientation. Further, 22% identified as heteroromantic, 32.2% as biromantic or panromantic, 5.1% as homoromantic, and 21.7% as other. Zheng and Su (2018) found discordant orientations in the majority of their asexual participants (n = 227), with 31.7% identifying as heteroromantic, 14.1% homoromantic, and 26.0% biromantic. In this sample, 28.2% identified as aromantic. In a recent examination of a merged dataset that included 1,475 asexual participants, Antonsen et al. (2020) found that 74.7% of asexual adults had discordant sexual and romantic orientations. Across these studies, asexual identification with discordant (non-aromantic) sexual and romantic orientations ranged from 71.8 to 81%, indicating that asexual people are more likely to identify as having discordant sexual and romantic orientations compared to allosexual individuals. However, there are few studies that make direct comparisons between allosexual and asexual identification with respect to concordance between sexual and romantic orientations. What does exist is based on varying methods of determining concordance and so further exploration is warranted.

Understanding concordant and discordant sexual and romantic identifications would allow researchers to explore diversity within asexual samples, especially when considering the characterization of asexuality as a spectrum. That is, for asexual people, the intersection between romantic and sexual orientation is complex, and those who identify as aromantic likely have vastly different experiences than those who identify as one of many possible romantic orientations. For example, Antonsen et al. (2020) indicated that romantic asexual people were more likely to currently be in a relationship, to report more romantic and sexual partners, and to report more frequent kissing than aromantic asexual people. However, quantitative asexual research does not always make a distinction between romantic and aromantic asexual people (e.g., Brotto et al., 2010). The concordance between sexual and romantic orientation may serve as an additional source of variability within asexuality research. Thus, in the same way that researchers make comparisons within allosexual samples (e.g., heterosexual vs. gay/lesbian vs. bisexual), comparisons within asexual samples may be necessary to capture a clearer picture of the heterogeneity within these samples, and what implications concordance rates may hold for experiences of human sexuality and romantic partner relationships.

Another aspect of sexuality that must be considered is the idea that asexual people may experience differing attitudes toward engaging in sex. Some studies have examined how asexual people describe experiences of sex (e.g., Dawson et al., 2016; Van Houdenhove et al., 2015b), yet only one study has actively categorized the sexual experiences of asexual adults (Carrigan, 2011). Carrigan proposed a typological model of qualitative commonalities about engaging in sex within an asexual sample. The model classified sexual attitudes into four categories: sex-positive, sex-neutral, sex-averse, and anti-sex. Sex-positive describes an asexual person without the sexual drive to seek out intercourse, but who may have an interest in or enjoy sex. Sex-neutral indicates a lack of interest in or indifference toward sex. Sex-averse describes an asexual person who feels distressed or disgusted by sex, and, in the case of anti-sex attitudes, may be disgusted by the thought of another person (or other people) engaging in sex (Carrigan, 2011).

Carrigan’s (2011) typology aligns with subsequent qualitative and quantitative research that indicates asexual people often describe sexual experiences in either a neutral or negative manner (Chasin, 2015; Dawson et al., 2016; Haefner, 2012; Van Houdenhove et al., 2015b). Although, it is important to note that not all asexual people describe negative sexual experiences. Interestingly, although Carrigan (2011) theorizes sex-positive as a distinct category, it seems counterintuitive that an asexual person would identify as such. Indeed, only one asexual person identified as sex-positive in Carrigan’s study. It may be the case that sex-positive asexual people exist but are not very common, or, alternatively, they might be hesitant to identify as such because they already face disbelief from family, friends, and romantic partners (Gupta, 2017; Haefner, 2012; Robbins et al., 2016; Vares, 2018). Thus, identifying as sex-positive might be further misinterpreted as a negation of one’s asexuality.

Understanding an asexual person’s sexual attitude may provide a novel understanding of how asexual people navigate sexual behaviors and romantic partner relationships. For asexual individuals who desire romantic relationships, this type of navigation may be particularly important because frequency of sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction have been shown to be correlated with relationship satisfaction (e.g., Byers & Wang, 2004; Sprecher et al., 2018), and varying levels of attitudes toward engaging in sex may differentially impact a person’s sexual and relationship satisfaction within a romantic relationship. Overall, a focus on sexual attitudes is a novel approach to understanding asexuality. However, it is still unclear at what rates asexual people can be categorized as sex-positive, sex-neutral, or sex-averse. Additionally, it is not common to explicitly ask allosexual people to identify with different sexual attitudes, possibly because the default assumption is that allosexual people have a generally positive attitude toward sex, barring traumatic circumstances (e.g., sexual assault, childhood sexual abuse) or sexual dysfunction.

The Current Study

The goal of the current study was to further our understanding of the concordance between romantic and sexual orientations. We also examined how asexual and allosexual adults self-identify with respect to their attitudes about engaging in sex and the differences that exist in how people with these different identity labels feel about sexual intimacy. Understanding how sexual intimacy attitudes vary within asexual people will add to the research literature on the heterogeneity within asexual experiences with implications for understanding how asexual people navigate sexual behaviors and romantic relationships. Our research hypotheses were as follows:

-

1.

Allosexual adults will be more likely to have concordant sexual and romantic orientations than asexual adults.

-

2.

Allosexual adults will more likely identify with a sex-positive sexual attitude, whereas asexual adults will more likely identify as either sex-neutral or sex-averse.

-

3.

Allosexual adults will have more positive sexual intimacy attitudes than asexual adults, and this difference will be evident for all three attitudes (i.e., sex-positive, sex-neutral, and sex-averse).

-

4.

Romantic asexual adults will report more positive sexual intimacy attitudes than aromantic asexual adults, and this difference will be evident for asexual adults who identify as sex-neutral or sex-averse.

Method

Participants

A total of 616 participants were recruited through a combination of targeted websites (asexuality.org, asexuality.livejournal.com), general social media sites (Tumblr, Facebook), and a Midwestern university’s school-wide e-mail system. We excluded 104 participants who did not provide consent or did not answer the sexual orientation question.

Because heterosexual women were over-represented in our comparison group of sexual participants, we randomly sampled 121 of the 182 heterosexual women who responded to match the sample size of 121 heterosexual men who responded to the survey. We retained 449 participants for the current study’s analyses. Descriptive statistics for the demographic characteristics of the sample of 109 asexual and 340 allosexual participants are shown in Table 1.

Measures

Sexual and Romantic Orientation

Sexual and romantic orientations were assessed with two separate single-item questions that asked participants to self-identify with various identities. For sexual orientation, participants were asked, “With respect to sexual orientation, how do you self-identify? (As in, who are you physically attracted to?).” Participants could respond with Heterosexual, Homosexual (Gay), Homosexual (Lesbian), Bi-sexual, Pansexual, Asexual, Asexual (Gray-A), Asexual (Demi-sexual), Asexual (A-Fluid), or Other. For analyses, Homosexual (Gay) and Homosexual (Lesbian) were combined into one category, Gay/Lesbian. Asexual participants were categorized as anyone who responded with a sexual orientation of Asexual, Asexual (Gray-A), Asexual (Demi-sexual), or Asexual (A-Fluid), using a methodology similar to Rothblum et al. (2020). All other participants were categorized as allosexual.

For romantic orientation, participants were asked, “With respect to romantic orientation, how do you self-identify? (As in, who are you romantically attracted to?).” Participants could respond with Heteroromantic, Homoromantic (Gay), Homoromantic (Lesbian), Bi-romantic, Panromantic, Aromantic, Other, or Prefer not to answer. Participants were considered to have a concordant sexual and romantic orientation if their sexual orientation and romantic orientation aligned (e.g., heterosexual and heteroromantic).

Sexual Attitude

To measure general attitude toward engaging in sexual intercourse, one question directly asked participants, “What is your general attitude about engaging in sexual intercourse?” Four response choices were provided: positive, neutral, averse, or none of these apply to me. Note that we assumed that the positive, neutral, and averse categories refer to how someone feels about themself participating in sex. The term anti-sex has been used to refer to someone who is against sex regardless of who is engaging in it (Carrigan, 2011); however, anti-sex was not used as a distinct category in the current study. This decision was not intended to diminish the variability within an asexual sample, but to assess sexual attitudes that relate to personal feelings about engaging in sex, as opposed to an inherent universal dislike.

Sexual Intimacy Semantic Differential Task

To measure sexual intimacy attitudes, a semantic differential task was employed. The semantic differential task created for the current study used word pairs that relate to constructs associated with asexuality and its defining features, such as attraction, desire, interest, avoidance, arousal, and disgust (e.g., Carrigan, 2011; Van Houdenhove et al., 2015a; Yule et al., 2015). Participants were presented with six dichotomous antonym pairs: negative/positive, disgusted/pleased, uninterested/interested, not aroused/aroused, averse/not averse, and unwilling/willing. For each pair, they were asked, “How would you label your attitude or feelings about engaging in sexual intimacy?” They were provided with a sliding scale of 0 to 100, with the lower bound consisting of the more aversive word in each pair (e.g., negative = 0, positive = 100). The internal consistency for these items was α = 0.96.

Demographics

Participants were asked to respond to demographic questions about age, biological sex, gender identity, and current relationship status. To measure previous relationship experience, participants were asked, “Have you previously been in a romantic relationship?”. To assess previous sexual experience, participants were asked, “Have you previously engaged in any consensual sexual experiences?”.

Procedure

The current study was approved by the lead researcher’s institutional review board. The questionnaire was administered through an online survey using Qualtrics. Participants answered questions about their attitudes toward engaging in sexual intimacy and sexual intercourse. After this, participants were asked demographic and other open-ended questions not reported here. Upon completion of the survey, participants were thanked for their time, debriefed, and given the opportunity to provide an e-mail address if they wished to be entered into a gift card raffle. The raffle was for one $20 Amazon gift card. Participant e-mails were stored separately from their surveys, and no other identifying information was collected.

Results

Associations Between Sexual Identity and Sexual-Romantic Concordance

Within our sample of allosexual participants, 99.1% selected a romantic orientation (three identified as aromantic). There was a clear trend for allosexual participants to choose a romantic orientation that matched their sexual orientation. Overall, 89% of allosexual participants had a concordant sexual and romantic orientation. Almost all heterosexual participants (96%) identified as heteroromantic; the majority of gay/lesbian participants (81%) identified as homoromantic. Most pansexual participants (71%) reported being panromantic. For bisexual participants, 64% identified as biromantic (23% identified as heteroromantic).

Within the asexual sample, of the 105 asexual participants who selected a romantic orientation, 37% had a concordant aromantic orientation. For Hypothesis 1, we predicted that allosexual adults would be more likely to have concordant sexual and romantic orientations than asexual adults. We examined the association between Sexual Identity (allosexual, asexual) and Concordance (concordant, discordant) and found support for Hypothesis 1, χ2(1, N = 440) = 39.4, p < 0.001. As a follow-up, we examined the two common categories of sexual attitude for asexual participants to determine if there was an association between Attitude and Concordance; 36% of sex-neutral and 40% of sex-averse individuals had concordant sexual and romantic orientations, χ2(1, N = 91) = 0.91, p = 0.66. The six asexual participants who identified as sex-positive (two concordant) were not included in this analysis because of a violation of the minimum expected cell size assumption of the χ2 test.

Sexual Attitudes

For our second hypothesis, we predicted that allosexual adults would more likely identify with a sex-positive sexual attitude, whereas asexual adults would be more likely identify as either sex-neutral or sex-averse. Participants were asked a forced-choice question to identify as sex-positive, sex-neutral, sex-averse, or none of these apply to me. Fourteen participants selected none of these apply to me and were excluded from subsequent analyses. The majority of allosexual participants identified as sex-positive (82%; n = 274), with 15% (n = 50) identifying as sex-neutral, and only 3% (n = 10) as sex-averse. In contrast, asexual participants identified as either sex-averse (53.5%, n = 54) or sex-neutral (40.6%; n = 41), with only six participants (5.9%) identifying as sex-positive. A chi-square analysis confirmed an association between Sexual Identity (allosexual vs. asexual) and identification with sexual attitude sub-categories, χ2(2, N = 435) = 228.37, p < 0.001. This pattern was consistent with our prediction for Hypothesis 2.

Sexual Intimacy Attitudes

For Hypothesis 3, we predicted that allosexual adults would have more positive sexual intimacy attitudes on the semantic differential task when compared to asexual adults and that this difference would be evident across all three Sexual Attitudes (i.e., sex-positive, sex-neutral, and sex-averse). Descriptive statistics for the six word pairs for the sexual intimacy semantic differential task are given in Appendix A for allosexual participants and in Appendix B for asexual participants.

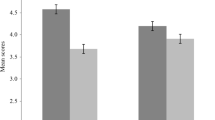

For the sake of parsimony and because the internal consistency was so high (α = 0.96), we computed an overall semantic differential score across the six pairs. We conducted a 2 (Sexual Identity: allosexual vs. asexual) × 3 (Sexual Attitude: positive, neutral, averse) ANOVA on overall mean scores. For Hypothesis 3, the expected main effect of Sexual Identity was evident, F(1, 429) = 55.4, p < 0.001, ηρ2 = 0.11. Allosexual adults (M = 81.97, SD = 19.24) had more positive sexual intimacy attitudes than asexual adults (M = 27.23, SD = 22.98). The expected main effect for Sexual Attitude was also evident, F(2, 429) = 97.5, p < 0.001, ηρ2 = 0.31. Sex-positive adults (M = 87.03, SD = 14.43) had the most positive sexual intimacy attitudes, followed by sex-neutral (M = 52.58, SD = 19.70) and then sex-averse (M = 15.24, SD = 15.39) adults. As shown in Fig. 1, there was no interaction between Attitude and Identity, F(2, 429) = 0.26, p = 0.77. Simple effects analyses indicated that adults with sex-positive attitudes had intimacy scores that were significantly more positive than sex-neutral (p < 0.001) or sex-averse (p < 0.001) adults, and intimacy attitudes for sex-neutral adults were significantly more positive than those of sex-averse adults (p < 0.001).

Asexual Romantic Orientation and Sexual Attitudes

When considering only our asexual participants, we predicted that romantic asexual adults would report more positive sexual intimacy attitudes than aromantic asexual adults and that this difference would be evident for those who identify as sex-neutral or sex-averse. That is, we predicted that aromantic sex-averse individuals would have the lowest scores on the sexual intimacy semantic differential task. We conducted a 2 (Sexual Attitude: neutral vs. averse) × 2 (Romantic Orientation: romantic vs. aromantic) ANOVA on mean scores on the semantic differential task. For this analysis, we did not include two sex-positive aromantic and four sex-positive romantic asexual participants. As expected, the main effect of Sexual Attitude was significant, F(1, 87) = 76.3, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.47. Sex-neutral adults (M = 41.31, SD = 17.33) had more positive sexual intimacy attitudes than sex-averse adults (M = 12.69, SD = 12.00). However, we did not find the expected main effect of Romantic Orientation, F(1, 87) = 0.72, p = 0.40, and the interaction term was not significant, F(1, 87) = 0.73, p = 0.39 (Fig. 2). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was only partially supported.

Overall mean scores for the sexual intimacy semantic differential task for asexual participants as a Function of Sexual Identity and Romantic Orientation. Note. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error. Four asexual participants identified as sex-positive with a romantic orientation (M = 76.21, SD = 13.6); two asexual participants identified as sex-positive, but aromantic (M = 37.42, SD = 51.5)

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to examine and compare allosexual and asexual adults’ sexual and romantic orientation concordance. An additional goal was to better understand how allosexual and asexual adults identify with respect to sexual attitudes, as well as how people with different sexual attitudes feel about sexual intimacy. For our first hypothesis, we explored concordance rates in a sample of allosexual and asexual adults and our results supported our prediction that allosexual adults would be more likely to select a concordant romantic and sexual orientation. Our findings mirror previous research on the concordance between sexual and romantic orientation among allosexual people (Lund et al., 2016), but in our methodology, participants were free to self-identity with respect to their sexual and romantic orientations separately. Although allosexual people reported higher concordance rates, concordance differed based on sexual orientation. That is, heterosexual adults had the highest concordance rate, whereas bisexual adults had the lowest concordance rate. Considering that people typically experience romantic feelings toward those whom they are sexually attracted to (Diamond, 2003), it is particularly interesting that bisexual people were less likely to report romantic attraction to both sexes. In the Lund et al. (2016) sample, most individuals who had discordant romantic and sexual identities identified as bisexual. Very few allosexual adults in our sample reported an aromantic identity, in contrast to over one-third of asexual people. It is possible that experiencing any form of sexual attraction intuits experiencing romantic attraction; however, considering the inverse is experienced by a majority of asexual people (i.e., experiencing romantic, but not sexual attraction), it is remarkable that more allosexual individuals did not choose an aromantic identity. That is, given the current Western cultural milieu that supports “friends with benefits” or “hooking up,” it is interesting that more allosexual people in our sample did not self-identify as aromantic. However, it is also possible that despite aromanticism being commonly understood in the asexual community (e.g., Vares, 2018), the term may be unfamiliar to allosexual individuals, and more allosexual people might self-classify as aromantic if they were familiar with the concept and the term for it.

As predicted, asexual people in our sample reported more discordant orientations; thus, supporting previous research that discordant orientations are more common among asexual people (e.g., Antonsen et al., 2020; Brotto et al., 2010; Ginoza et al., 2014; Scherrer, 2008; Zheng & Su, 2018). That is, asexual people may identify with discordant orientations in an effort to understand their attractions based on the romantic feelings they do have instead of the sexual feelings they lack. Especially for individuals who desire a romantic partnership, the dissonance between their sexual feelings and romantic desire may impel them to consider various romantic orientations, similar to how allosexual people may explore different sexual orientations. Interestingly, the concordance rate within our sample (37%) was greater than that found in other samples (i.e., 19–28%), but it is unclear why this difference occurred.

We examined the frequencies with which allosexual and asexual adults identify as sex-positive, sex-neutral, or sex-averse. We hypothesized that allosexual adults would be more likely to identify as sex-positive, whereas asexual adults would be more likely to identify as sex-neutral or sex-averse. As predicted, our allosexual participants were more likely to identify as sex-positive, whereas the majority of asexual people identified as either sex-neutral or sex-averse. Of note, there were very few allosexual people who identified as sex-averse. It is possible allosexual people who identify as sex-averse do so due to negative sexual experiences or trauma, although, as discussed in more detail below, we did not assess trauma history. The discrepancy in sexual attitudes between allosexual and asexual individuals is enlightening, but at the same time, it is still unclear why there may be such a fundamental difference in how allosexual and asexual people experience and perceive sexual intercourse. For example, attraction or lack of attraction may have biological or physiological underpinnings, but it is not clear what may cause these physiological differences to be expressed in levels of desire or attraction.

Most of our asexual sample identified as sex-neutral or sex-averse, which aligns with previous qualitative research (Carrigan, 2011; Dawson et al., 2016; Van Houdenhove et al., 2015b). More specifically, asexual people identified as sex-neutral and sex-averse in similar frequencies, at around half of the asexual sample. Both identities are prevalent, but it is unclear why asexual people appear to be equally likely to identify as sex-neutral or sex-averse, at least within our sample. Additionally, it is unclear whether identifying as sex-neutral or sex-averse equally is a pattern more indicative in the asexual population overall. Future research exploring the distinctions between these two identities in asexual samples would help to better understand why an asexual person identifies as sex-neutral or sex-averse and how common identifying with either sexual attitude is. The commonality of either sexual attitude likely holds implications for asexual adults engaging in romantic partner relationships, where navigation of sexual behavior might drastically vary based on identifying as sex-neutral or sex-averse.

Interestingly, approximately 6% of our asexual sample identified as sex-positive. Although sex-positive asexual people were not common within our sample, the fact that a few asexual adults self-identified as such denotes that this category likely exists as a small, but legitimate self-identity category. Granted, the idea of a sex-positive asexual identity may seem counterintuitive; however, there may be more complicated mechanisms to explain the relation between sexual attitudes and sexual orientation. That is, because one does not experience sexual attraction does not mean one will not enjoy engaging in sexual intercourse. Clearly, more research is needed to understand more about the relationship experiences of people who self-identify as sex-positive asexual to better understand how their sex-positive attitudes might interact with their asexuality in relation to sexual behavior and experiences.

For our third hypothesis, we predicted that allosexual adults would have more positive sexual intimacy attitudes regardless of sexual attitude (i.e., sex-positive, sex-neutral, and sex-averse). We found support for our hypothesis, in that semantic differential scores for sexual intimacy attitudes were, on average, more positive for allosexual people than for asexual people. Additionally, allosexual people—regardless of sexual attitude—had higher scores than asexual people. It is important to highlight that allosexual and asexual people within the same sexual attitude sub-group in our sample did not score similarly on the semantic differential task. For example, sex-neutral allosexual people reported more positive intimacy attitudes than sex-neutral asexual people. Despite both groups identifying as sex-neutral, the discrepancy between them indicates that for asexual people, there might be an underlying difference in how they perceive sexual intimacy that is reflected in their more negative sexual intimacy attitudes. Future research should attempt to understand these differences, and whether they stem from physiological reactions, subjective opinions, or a combination of the two. A better understanding of the underpinnings of these differences might hold implications for relationship functioning and satisfaction in asexual–allosexual couples and may better explain how these couples negotiate sexual intimacy discrepancies.

Given that our asexual participants did make a distinction between their sexual and romantic orientations, we further explored the sexual intimacy attitudes of our asexual sample. Our final hypothesis predicted that romantic asexual people would have more positive sexual intimacy scores than aromantic asexual people, regardless of whether they identify as sex-neutral or sex-averse. Interestingly, our hypothesis was only partially supported. Asexual people who identified as sex-neutral held more positive views of sexual intimacy than those who identified as sex-averse. However, there were no significant differences between romantic and aromantic asexual people. It is possible that the lack of relation between romantic orientation and sexual attitude may indicate there are factors that influence both orientations separately. Regardless, that in our sample aromantic asexual people did not experience more negative attitudes about sexual intimacy has implications for future asexual research. Although romantic and aromantic asexual adults have been found to differ in relation to a variety of characteristics (e.g., Antonsen et al., 2020), our results indicate that in certain cases, both subgroups may be similar enough to warrant them being combined. More specifically, no differences or distinctions between the subgroups appear to be lost when considering sexual attitudes. Although, future research should further endeavor to replicate and expand upon these findings to better understand similarities and dissimilarities between romantic and aromantic asexual people within larger and more diverse samples.

Limitations

In the current study, because we were interested in the experiences of asexual people, we did not ask questions pertaining to childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, or trauma. This was a deliberate decision made to avoid the implication that these events may be a cause of one's asexuality or to potentially pathologize asexuality in any way. We consider the decision to avoid this topic both a strength and a limitation of the current study. Asexual people often face the assumption their lack of attraction was caused by previous trauma (e.g., Gupta, 2017), and although previous trauma has been considered, researchers have not found a relation between trauma and asexuality (e.g., Brotto et al., 2010). However, for our allosexual participants, it may have been useful to know if these factors were more common among those who identify as sex-neutral or sex-averse. As this was an initial exploratory study about identification and attitudes, we recognize this limitation.

Our measure of sexual attitude was based on interest in sexual intercourse, specifically, as opposed to sexual behavior in general. Some asexual people might hold more favorable attitudes toward sexual behaviors (broadly defined) than to sexual intercourse. A more nuanced examination of attitudes toward the range of sexual experiences within a romantic partnership is a beneficial avenue for future research. Similarly, we did not assess participants’ degree of interest in romantic relationships. An item to assess level of romantic interest would have provided additional insight into the concordance of attitudes between allosexual and asexual adults. It is possible, for example, that individuals who identify as heterosexual and heteroromantic may vary in the amount of interested in pursuing a romantic relationship. Allosexual individuals (regardless of orientations) with lower interest in romantic relationships may hold attitudes similar to those of aromantic individuals. Future relationship research, especially with asexual individuals, would benefit from including a measure of future interest in romantic relationships to help understand possible similarities or differences within these orientations.

Given that 14 participants did not identify as sex-positive, sex-neutral, or sex-averse, we were curious as to why none of these labels applied. For example, these participants were not all in one identity group; six were allosexual and eight were asexual. We then theorized that not having any past consensual sexual experience may explain not having an opinion about one’s sexual attitude. However, there were no clear patterns; half of the allosexual participants and one asexual participant had previous sexual experience. Thus, we have insufficient evidence to determine why these participants were not able to identify with a sexual attitude.

Lastly, our sample overall was predominately White, and our allosexual sample was predominantly heterosexual. It is possible that discordance in sexual and romantic orientations is more apparent for non-heterosexual people or that there is more variation within certain subgroups of allosexual people (e.g., bisexual and pansexual adults). Similarly, our mostly White sample does not reflect current population statistics of race within the USA, and there may be more within-group variance in non-White samples that we failed to capture within our current sample.

Conclusion

The current study highlights how allosexual and asexual people vary with respect to the concordance (or discordance) between romantic and sexual orientation. We provide supporting evidence for heterogeneity in the asexual population, with only a third of our sample identifying as both asexual and aromantic. We also see variability within the allosexual population, with the highest concordance rates for heterosexual participants and the lowest concordance rates among bisexual participants. Further, we explored self-identification with respect to sexual attitudes and differences in attitudes about sexual intimacy. The current study contributes to the literature on relationships and sexuality by providing a more nuanced examination of within-group and between-group variations and their implications for romantic partner relationships.

Data Availability

Data files are available upon request.

References

Antonsen, A. N., Zdaniuk, B., Yule, M., & Brotto, L. A. (2020). Ace and aro: Understanding differences in romantic attractions among persons identifying as asexual. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 1615–1630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01600-1

Asexuality Visibility and Education Network (AVEN). (2017). Overview. Retrieved from http://www.asexuality.org/home/overview.html

Bogaert, A. F. (2004). Asexuality: Prevalence and associated factors in a national probability sample. Journal of Sex Research, 41(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552235

Bogaert, A. F. (2015). Asexuality: What it is and why it matters. Journal of Sex Research, 52(4), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1015713

Borgogna, N. C., McDermott, R. C., Aita, S. L., & Kridel, M. M. (2019). Anxiety and depression across gender and sexual minorities: Implications for transgender, gender nonconforming, pansexual, demisexual, asexual, queer, and questioning individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000306

Brotto, L. A., Knudson, G., Inskip, J., Rhodes, K., & Erskine, Y. (2010). Asexuality: A mixed-methods approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(3), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9434-x

Brotto, L. A., & Yule, M. (2017). Asexuality: Sexual orientation, paraphilia, sexual dysfunction, or none of the above? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0802-7

Brotto, L. A., Yule, M. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2015). Asexuality: An extreme variant of sexual desire disorder? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(3), 646–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12806

Byers, E. S., & Wang, A. (2004). Understanding sexuality in close relationships from the social exchange perspective. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 203–234). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Carrigan, M. (2011). There’s more to life than sex? Difference and commonality within the asexual community. Sexualities, 14(4), 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460711406462

Carrigan, M. A. (2012). “How do you know you don’t like it if you haven’t tried it?” Asexual agency and the sexual assumption. In T. G. Morrison, M. A. Morrison, M. A. Carrigan, & D. T. McDermott (Eds.), Sexual minority research in the new millennium (pp. 3–20). Nova Science Publishers.

Carvalho, J., Lemos, D., & Nobre, P. J. (2017). Psychological features and sexual beliefs characterizing self-labeled asexual individuals. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(6), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1208696

Chasin, C. D. (2015). Making sense in and of the asexual community: Navigating relationships and identities in a context of resistance. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2203

Dawson, M., McDonnell, L., & Scott, S. (2016). Negotiating the boundaries of intimacy: The personal lives of asexual people. Sociological Review, 64(2), 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12362

Decker, J. S. (2015). The invisible orientation: An introduction to asexuality. Skyhorse Publishing.

Diamond, L. M. (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110(1), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.173

Ginoza, M. K., Miller, T., & AVEN Survey Team. (2014). The 2014 AVEN community census: Preliminary findings. Retrieved November 25, 2020 from https://asexualcensus.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/2014censuspreliminaryreport.pdf

Gupta, K. (2017). “And now I’m just different, but there’s nothing actually wrong with me”: Asexual marginalization and resistance. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(8), 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1236590

Haefner, C. (2012). Asexual scripts: A grounded theory inquiry into the intrapsychic scripts asexuals use to negotiate romantic relationships. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section b. Sciences and Engineering, 72(8B), 5025.

Lund, E. M., Thomas, K. B., Sias, C. M., & Bradley, A. R. (2016). Examining concordant and discordant sexual and romantic attraction in American adults: Implications for counselors. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 10(4), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2016.1233840

Prause, N., & Graham, C. A. (2007). Asexuality: Classification and characterization. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9142-3

Przybylo, E. (2016). Introducing asexuality, unthinking sex. In N. L. Fischer & S. Seidman (Eds.), Introducing the new sexuality studies (pp. 181–191). Routledge Taylor.

Robbins, N. K., Low, K. G., & Query, A. N. (2016). A qualitative exploration of the “coming out” process for asexual individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0561-x

Rothblum, E. D., Krueger, E. A., Kittle, K. R., & Meyer, I. H. (2020). Asexual and non-asexual respondents from a U.S. population-based study of sexual minorities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 757–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01485-0

Scherrer, K. S. (2008). Coming to an asexual identity: Negotiating identity, negotiating desire. Sexualities, 11(5), 621–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460708094269

Scherrer, K. S. (2010). What does asexuality have to do with polyamory? In M. Baker & D. Langdridge (Eds.), Understanding non-monogamies (pp. 154–159). Routledge.

Sprecher, S., Christopher, F. S., Regan, P., Orbuch, T., & Cate, R. M. (2018). Sexuality in personal relationships. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (2nd ed., pp. 311–326). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316417867.025

Thompson, E., & Morgan, E. M. (2008). “Mostly straight” young women: Variations in sexual behavior and identity development. Developmental Psychology, 44, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.15

Van Houdenhove, E., Gijs, L., T’Sjoen, G., & Enzlin, P. (2015a). Asexuality: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Sex Research, 52(6), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.898015

Van Houdenhove, E., Gijs, L., T’Sjoen, G., & Enzlin, P. (2015b). Stories about asexuality: A qualitative study on asexual women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(3), 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2014.889053

Vares, T. (2018). ‘My [asexuality] is playing hell with my dating life’: Romantic identified asexuals negotiate the dating game. Sexualities, 21(4), 520–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460717716400

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2015). A validated measure of no sexual attraction: The asexuality identification scale. Psychological Assessment, 27, 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038196

Zheng, L., & Su, Y. (2018). Patterns of asexuality in China: Sexual activity, sexual and romantic attraction, and sexual desire. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1265–1276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1158-y

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study or to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article and certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Illinois State University (ethics approval number: 2018-277).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Means, standard deviations, range, and median for the engagement in intimacy attitude semantic differential task for sex-positive, sex-neutral, and sex-averse allosexual participants.

Sex attitude | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sex-positive (n = 274) | Sex-neutral (n = 50) | Sex-averse (n = 10) | ||||

M (SD) | Range (median) | M (SD) | Range (median) | M (SD) | Range (median) | |

Negative/positive | 90.00 (12.27) | 20–100 (92) | 61.00 (19.76) | 18–100 (65) | 28.70 (25.00) | 0–85 (27.5) |

Disgusted/pleased | 88.57 (16.48) | 3–100 (92) | 61.44 (23.41) | 10–100 (60.5) | 38.90 (25.87) | 0–85 (45) |

Uninterested/interested | 88.14 (17.14) | 2–100 (93) | 59.88 (22.44) | 1–100 (59.5) | 26.90 (29.76) | 0–83 (20) |

Not aroused/aroused | 85.17 (18.03) | 3–100 (90) | 63.94 (24.25) | 1–100 (69.5) | 44.10 (37.36) | 0–90 (45) |

Averse/not averse | 84.31 (21.68) | 1–100 (91) | 60.31 (23.46) | 0–100 (60) | 25.10 (23.38) | 0–53 (24.5) |

Unwilling/willing | 88.61 (17.40) | 1–100 (95) | 62.76 (21.36) | 15–100 (60.5) | 23.40 (18.83) | 0–50 (23) |

Appendix B

Means, standard deviations, range, and medians for the engagement in intimacy attitude scale semantic differential task for sex-positive, sex-neutral, and sex-averse asexual participants.

Sex attitude | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sex-positive (n = 6) | Sex-neutral (n = 41) | Sex-averse (n = 54) | ||||

M (SD) | Range (median) | M (SD) | Range (median) | M (SD) | Range (median) | |

Negative/positive | 65.33 (35.09) | 1–92 (79.5) | 48.46 (20.89) | 0–85 (50) | 20.09 (20.36) | 0–83 (15.5) |

Disgusted/pleased | 66.33 (33.68) | 1–92 (75) | 47.41 (18.99) | 0–100 (50) | 17.65 (17.16) | 0–60 (15.5) |

Uninterested/interested | 52.83 (38.61) | 1–90 (65) | 25.88 (23.62) | 0–80 (20) | 4.65 (7.62) | 0–30 (1) |

Not aroused/aroused | 61.67 (31.30) | 1–85 (74) | 27.61 (24.56) | 0–80 (20) | 9.52 (16.02) | 0–70 (1.5) |

Averse/not averse | 71.33 (36.56) | 1–100 (81) | 51.05 (25.93) | 0–100 (50) | 10.17 (14.87) | 0–60 (5) |

Unwilling/willing | 62.17 (35.03) | 1–100 (65.5) | 49.37 (24.61) | 0–91 (50) | 11.63 (18.76) | 0–75 (1) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, A.N., Zimmerman, C. Concordance Between Romantic Orientations and Sexual Attitudes: Comparing Allosexual and Asexual Adults. Arch Sex Behav 51, 2147–2157 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02194-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02194-3