Abstract

Using an extended definition of sexuality, this mixed-methods study builds on existing research into adolescents’ emergent sexual development by longitudinally examining adolescents’ sexual behavior trajectories (i.e., from less to more intimate sexual behavior). Over a 2-year period, 45 adolescents (M age = 15.9 years) reported on their sexual behavior using questionnaires and on their everyday expressions of sexuality in the form of semi-structured diaries. Cluster analysis using the questionnaire data identified three sexual behavior trajectories: a non-sexually active trajectory (meaning no or minor sexual behavior) (n = 29), a gradually sexually active trajectory (meaning step-by-step sexual behavior development) (n = 12), and a fast sexually active trajectory (meaning rapid sexual behavior development) (n = 4). Qualitative analysis using diaries revealed the following themes: romantic versus sex-related topics, desires, uncertainties, and references to the social context. In general, all adolescents reported more about romantic aspects of sexuality (than about sexual acts) in the diaries, regardless of their sexual behavior trajectory. Sexually active adolescents (i.e., gradual and fast) were more concerned with sexuality in their diaries, especially more with the physical aspects of sexuality, than non-active adolescents. Gradual adolescents experienced more desires about physical sexual contact and reported fewer references to their social network than non-active and fast adolescents. The findings suggest that sexual education that discusses the internal experiences of sexuality, such as feelings and thoughts, particularly the romantic aspects, may help adolescents process their preferences for different sexual and romantic acts and may contribute to healthy sexual development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The emergent development of sexuality is a normative transition during adolescence and a central aspect of human life (Smiler, Ward, Caruthers, & Merriwether, 2005; Tolman & McClelland, 2011; WHO, 2012). However, various sexual activities may affect adolescents’ psychological well-being. For instance, while some adolescents experience fulfillment of desires after sexual activities, others have feelings of regret or guilt. Real-life feelings and thoughts may explain how sexual behavior affects adolescents’ psychological well-being. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the development of sexual behavior across adolescence and to study what everyday expressions are associated with different trajectories of sexual development.

Little research has focused on the speed of progression of sexual developmental trajectories in terms of less to more intimate behaviors. To our knowledge, only one study has examined the speed of progression of sexual behaviors using a cross-sectional sample in the Netherlands (de Graaf, Vanwesenbeeck, Meijer, Woertman, & Meeus, 2009). However, cross-sectional studies are limited in terms of capturing the sequence of various sexual behaviors. In addition, little research has examined adolescents’ own expressions of their sexual development (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009; Russell, 2005). Researchers often study sexual development using a pre-established list of topics. Although these studies present interesting findings on sexual development, they do not provide insight into personal, often more complex, experiences in real life. A focus on everyday expressions of sexual behavior, such as thoughts, feelings, and desires, can provide more in-depth insights into a broad spectrum of young people’s sexual development.

An Extended Definition of Sexual Development

In addition to various sexual behaviors, emergent sexual development also encompasses internal experiences of (future) sexual encounters, such as fantasies, desires, and feelings of uncertainty (Edwards & Coleman, 2004; Lefkowitz, 2002; WHO, 2012). Research shows that adolescent girls’ sexual cognitions (i.e., their attitudes, expectations, beliefs, and values framing their sexual experiences) change before having their first sexual intercourse (O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005). In addition to physical aspects of sexuality (e.g., sexual fantasies and behaviors), sexuality also entails romantic aspects such as finding someone attractive, being in love, or experiences within the romantic relationship. In fact, Dutch adolescents have more romantic involvements than sexual encounters (de Graaf et al., 2012). Furthermore, adolescents spend a great deal of time discussing romantic experiences with their peers (Lefkowitz, Boone, & Shearer, 2004; Simon, Eder, & Evans, 1992).

This extended definition of sexuality ensures that, in addition to adolescents who perform sexual acts, our study will also include adolescents who are not yet involved in sexual behavior. Non-sexually active adolescents are not engaging in sexual acts with others, but they may have related thoughts, feelings, fantasies, and desires. A complete picture of emergent sexual development also encompasses adolescents who have not yet had explicit sexual contact with (potential) sexual partners. The majority of studies on sexual behavior, however, have exclusively focused on whether adolescents have had sexual intercourse (e.g., Schwartz, 1999; Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008).

Yet, sexual intercourse is only one component of the various sexual behaviors adolescents may engage in during the course of their sexual development. Other forms are, for example, French-kissing and fondling on top of and underneath clothing. By exclusively focusing on sexual intercourse, other sexually active adolescents are excluded from studies. Research focusing on various sexual behaviors has demonstrated that most adolescents follow a progression from kissing via fondling on top of and underneath clothing to actually having sexual intercourse (e.g., de Graaf et al., 2009; Halpern, Joyner, Udry, & Suchindran, 2000; Jakobsen, 1997; Lam, Shi, Ho, Stewart, & Fan, 2002; O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005; Shtarkshall, Carmel, Jaffe-Hirschfield, & Woloski-Wruble, 2009; Smiler, Frankel, & Savin-Williams, 2011; Wiegerink, Stam, Gorter, Cohen-Kettenis, & Roebroeck, 2010).

The research literature about adolescent romantic development shows that in the Western culture adolescents progress from less intimate to more intimate romantic behaviors (Connolly & McIsaac, 2011). In general, they start with solitary romantic fantasies and progress via unconstrained dating activities to a more intimate dyadic romantic relationship. Based on the research literature, our study explores the temporal sequence of Dutch adolescent sexual behaviors from less intimate to more intimate behaviors.

Adolescents’ Sexual Behavior Trajectories: Gradual and Fast

Adolescents may progress differently from less intimate to more intimate sexual behaviors. By incorporating a full description of sexual behavior, cross-sectional research in the Netherlands has shown two sexually active trajectories: gradual (or linear) and fast (or nonlinear) (de Graaf et al., 2009). The gradual sexual trajectory was more common (73%) and encompassed adolescents who gradually and linearly progressed from less to more intimate sexual behavior. They followed a step-by-step sequence from kissing via fondling to having sexual intercourse. In contrast, adolescents having a fast sexual trajectory (27%) rapidly develop from one sexual behavior to the next. Mostly immigrant and low-educatedFootnote 1 adolescents followed this rapid development into more intimate sexual behaviors (de Graaf et al., 2009). The gradual sexual trajectory is believed to be healthier (than fast), because it is linked to more consistent contraceptive use (de Graaf et al., 2009). Generally, boys in the USA, Canada, and the UK report an earlier and higher speed of progression for sexual activities than girls (Hansen, Paskett, & Carter, 1999; Williams, Connolly, & Cribbie, 2008; Waylen, Ness, McGovern, Wolke, & Low, 2010). In the Netherlands, however, boys and girls are equally likely to follow a gradual or a fast trajectory (de Graaf et al., 2009).

Some of the first in-depth qualitative studies on speed of progression of sexual behavior trajectories were done in the Netherlands and the USA (Rademakers & Straver, 1986; Thompson, 1990). These studies reported that fast trajectories appeared to be less healthy, since the shorter amount of time between the various sexual acts may limit opportunities to direct their sexual development in terms of their own needs. Adolescents with a gradual trajectory start with initial sexual behavior that fits their needs, such as the desire to kiss (Rademakers & Straver, 1986). Subsequently, adolescents experiment with this behavior; they explore their thoughts and feelings, and they gradually develop their preferences for new sexual behavior. In this way, adolescents have time to process the new information before proceeding to the next step of sexual behavior. They feel autonomous in performing sexual acts. Consequently, adolescents who gradually progress from less to more intimate sexual behavior view their sexual behavior development as positive (e.g., curiosity, desire, pleasure) (Thompson, 1990). In contrast, fast adolescents have less time to think and process previously performed acts. They experience their sexual development more negatively (e.g., painful, boring, disappointing) than gradual adolescents do (Thompson, 1990).

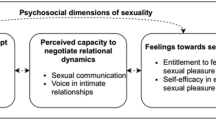

More recent research shows consistent results. A study in the USA has demonstrated that intentional (versus spontaneous) first sexual intercourse is one of the factors linked to a more positive first sexual intercourse experience (Smiler et al., 2005). One could imagine that a more intentional sexual intercourse experience is related to sufficient time for exploration of thoughts and feelings and subsequent autonomous engagement in this sexual activity. In addition, young women who feel empowered in having sexual desires and who reported greater sexual self-efficacy also reported fewer negative reactions to recent sexual intercourse (Zimmer-Gembeck, See, & O’Sullivan, 2014). Other research showed that girls with less sexual experience (not having experienced breast fondling) experienced lower sexual arousal, sexual agency, sexual self-esteem, and peer approval in having sex than did girls who initiated breast fondling over a 1-year period (O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005).

In general, these findings are from a heterosexual perspective, since sexual minorities are less likely to follow the expected sequence from kissing to sexual intercourse (Fish & Pasley, 2015; Smiler, Frankel, & Savin-Williams, 2011). A cross-sectional Dutch study showed that some gay men and lesbian women have opposite sex experiences, while others do not (de Graaf & Picavet, 2018). In addition, same sex behaving adolescents are more variable than opposite sex behaving adolescents in their sequence of sexual behaviors (for girls, see de Graaf & Picavet, 2018; Diamond, 2012; for boys, see Smiler, Frankel, & Savin-Williams, 2011).

The Netherlands is known for its pragmatic and liberal sex-positive governmental policy, which generally achieves better sexual health statistics than the USA or the UK (Parker, Wellings, & Lazarus, 2009; Weaver, Smith, & Kippax, 2005). Dutch culture is characterized by general acceptance of adolescent sexuality and by open communication about sexual development (De Looze, Constantine, Jerman, Vermeulen-Smit, & ter Bogt, 2014; Schalet, 2011). In the Netherlands, the focus of adolescent sexual development is not on delaying of sexual behavior but rather on the initiation of sexual activity with the guidance and support of adults and society as a whole (e.g., safe-sex public health campaigns, easy access to condoms) (Schalet, 2011). The Dutch society is not unique in their sex-positive governmental policy. For instance, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and Germany have also a liberal attitude toward sexuality education (Parker, Wellings, & Lazarus, 2009).

In line with the World Health Organization (2012), we view sexual development as a broadly defined concept. Sexual development is influenced by transactions of various factors within the social context (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994; van Geert, 2002; WHO, 2012): The social context influences the sexual development of the young person, and, likewise, the sexual development of the young person influences the social context. “Social context” is defined as the direct experience of interactions in real life, or the experiences within the home or school system, and, more indirectly, as the influences of the socioeconomic status of the parents or the society, in which the young person is living. In short, sexual development depends on the intertwining of biological, social, cultural, and individual factors. A young person’s actions and interactions with others in real life constitute a platform where these factors meet.

Current Study

Previous studies on adolescents’ sexual development were mostly retrospective cross-sectional and focused on a narrow definition of sexuality. In conformity with the concept of sexuality as a central aspect of human life, the focus of this study is an elaborated definition of sexuality that encompasses variations in sexual behavior, as well as private representations (Edwards & Coleman, 2004; Hilber & Colombini, 2002; WHO, 2012). This study extends existing research by exploring the speed of adolescents’ sexual behavior trajectories, and how this speed relates to the real-time everyday expression of sexual development prospectively over a 2-year period. In order to do so, we implemented a longitudinal qualitative diary study to examine Dutch adolescents’ temporal sequence of behavior trajectories from less to more intimate sexual activities and their everyday expression of their sexual development. This study aims to improve our understanding of adolescents’ perceptions of their sexual development from the unique viewpoint of the adolescents themselves. We studied adolescents’ expressions of their everyday sexual development qualitatively (important themes) and quantitatively (i.e., frequency). We also assessed differences between sexual behavior trajectories. Inspired by earlier research into sexual behavior trajectories, we explored (1) the non-sexual behavior trajectory, (2) the gradual sexual behavior trajectory, and (3) the fast sexual behavior trajectory (de Graaf et al., 2009).

Based on the research literature, we expected that non-sexually active adolescents would report fewer expressions of sexuality in their diaries than adolescents in gradual and fast sexual behavior trajectories. Furthermore, it was expected that the romantic aspects would be more profound than the physical aspects of sexuality, even though sexually active trajectories are thought to express more about the physical aspects (e.g., sexual intercourse, French-kissing) of sexuality than the trajectories of non-active adolescents. Additionally, we qualitatively and quantitatively explored whether it was possible to find overarching themes and, subsequently, to differentiate these themes in terms of sexual behavior trajectories.

Method

Participants

The main goal of the diary study was to describe emergent sexual development from the perspective of the adolescents themselves. Data for the current study were collected from 45 adolescents, who were asked to describe their everyday sexual experiences in a 2-year diary study. Initially, 123 adolescents (81 girls; 42 boys) participated in the study. Approximately half of the adolescents (53%) dropped out during the research period (Wave 1: n = 123; Wave 2: n = 98; Wave 3 n = 85; Wave 4 n = 75; Wave 5 n = 67; Wave 6 n = 65). Of the remaining 65 eligible participants, 20 adolescents were removed because of incomplete data or inconsistent answers (e.g., reporting fondling underneath clothing at Wave 1 but not at Wave 2). This left 45 adolescents (35 girls; 10 boys) who provided complete data.

The average age of the 45 participants was 15.9 years (SD= 1.6). Eighteen percent of the participants were enrolled in prevocational secondary education, 43% in senior general secondary education, and 39% in pre-university education. These are the three main types of high school education in the Netherlands. All participants had Dutch nationality and reported their sexual orientation as (predominantly) heterosexual.Footnote 2

The 45 participants consisted of significantly more girls and fewer boys than the initial n = 123 sample, χ2(1, N = 123) = 3.96, p = .047. There were no significant differences in age or educational level between the 45 participants of this study and the original sample.

Procedure

Six high schools known to the first author (via acquaintances and colleagues) were approached by e-mail, telephone, and through school visits. The schools were representative of the three main educational levels of high schools in the Netherlands. In addition to written and oral information about the research project, adolescents and their caregiver(s) received the invitation to voluntarily participate in the study and were asked to return a registration form. The goal of the study (to capture adolescents’ sexual development, broadly defined) was described, and it was explicitly mentioned that every adolescent between 12 and 18 years old could participate, including those who were not (yet) involved in sexual activities (e.g., sexual intercourse). It was important to recruit non-active adolescents, because we wanted to study the progression of sexual activity over a 2-year period. We explicitly mentioned that motivation was important, since the study design was time-consuming and intensive (i.e., regular reports over 2 years). An age range of 12 to 18 years was the selection criterion, because sexual development emerges during this period through exploring manifest experiences (e.g., de Graaf et al., 2012). The average age in the Netherlands for first sexual intercourse is 16.6 years (de Graaf et al., 2012). In addition, generally half of 12- to 14-year-old Dutch adolescents (boys: 48%; girls: 38%) have French-kissed someone (de Graaf et al., 2012). We had no exclusion criteria based on cognitive ability/delay, sexual attraction or orientation or physical health conditions. In the course of every diary period, we asked about life events. We explicitly asked for information about situations in the lives of the adolescents that could be of importance for our research. The participants in our study sample did not mention severe psychological or physical health conditions (although, for example, they did mention that they had the flu, bad grades or that their dog had died). In order to recruit adolescents for the diary study, we approached high schools in the Netherlands. We did not include schools for children with special needs. Permission from caregiver(s) was a requirement for participation in the study.

The study consisted of questionnaires and diaries. The data collection consisted of six waves of 6 weeks, separated by a 2-month break, over the course of 2 years. Six waves were chosen, because we did not want to overburden the participants. A weblog questionnaire assessing demographic information and sexual behavior was completed in the first week of the data collection period. In the weeks that followed, the participants completed a semi-structured weblog diary, assessing everyday experiences with sexuality. The questionnaires and diaries were maintained on a secure survey Web site. E-mail addresses and usernames were collected separately to guarantee anonymity.

Participants were allowed to ask questions and request advice or help after each diary entry, for ethical reasons. This support was provided in close collaboration with a mental health institution so e-health or referral to a support service could be offered if required. Those few participants (out of the initial sample of 123 participants) who asked questions were not included in our study’s 45-member sample because they dropped out during data collection or provided inconsistent or incomplete data. To increase participants’ motivation for the study, the main researcher remained in contact with the adolescent participants by e-mail. The main researcher sent out newsletters, Christmas greetings, and personally answered incoming e-mails. At the end of every data collection period, the adolescents were compensated for their participation by an increasing weekly reward starting with EUR 5 (W1) and ending with EUR 15 (W6). Prior to data collection, the study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Psychology.

Measures

Questionnaires: Sexual Behavior Trajectories

Participants assessed dichotomously whether or not (yes/no) they had experienced French-kissing (1), being fondled/fondling on top of clothing (2), being fondled/fondling underneath clothing (3), and going further than that (4). If they went further than fondling underneath clothing, they could write in an open-ended way what they had exactly done. Sexual behavior ranged from no sexual activity (0) to going further than fondling underneath clothing (4).

Because of ethical considerations, adolescents were protected against receiving information they were not ready for. This precaution was important, since the age range of adolescents who could participate in the study ranged from 12 to 18 years.

Repeated exposure to questions related to sexual activity may motivate adolescents to give a “yes” answer, despite not actually having performed the sexual act. Additionally, adolescents could be triggered to perform sexual acts that they had read about in the questionnaire. In order to overcome these problems, adolescents were exposed to the sexual activity questions adaptively. Only if adolescents wrote that they had been involved in kissing would they see the next question about fondling on top of clothing. In addition, adolescents reporting fondling on top of clothing would see the next question about fondling underneath clothing, etc.

The above-mentioned questionnaire items were used to calculate duration, progression, speed, and experience of sexual behavior over the 2-year period. First, duration was assessed for the sexual behavior that was reported with the longest duration during the research period. For example, a participant might report kissing at W1, and at W2, W3, and W4 fondling on top of clothing, and at W5 and W6 fondling underneath clothing. In this case, the duration was considered as fondling on top of clothing. Duration ranged from (0) no sexual activity to (4) going further than being fondled/fondling underneath clothing. Second, progression was assessed by subtracting the sexual behavior of W6 from the sexual behavior of W1. For example, from nothing (0) at W1 to going further (4) at W6, the progression was 4 (4 minus 0). Progression ranged from (0) no progression to (4) a progression within the research period from no sexual activity to going further than being fondled/fondling underneath clothing. Third, speed was computed if a participant skipped a sexual behavior from one point in time to the other (e.g., from W1 to W2). For instance, an adolescent could report (0) no sexual activity at W1 and (3) fondling underneath clothing at W2 resulting in a speed of 1 (i.e., skipping one sexual activity, namely fondling on top of clothing). Speed ranged from (0) skipping no sexual behavior to (3) skipping three sexual behaviors, within the research period. Finally, experience was assessed as the “highest” sexual behavior of all waves and could range from (0) no sexual activity to (4) going further than fondling underneath clothes.

In order to give more information about the intensiveness of adolescent sexual behaviors, the number of partners for each sexual behavior was assessed with the following question “How many people have you [sexual behavior]?” The participants could answer with an open answer option indicating in digits how many people they have French-kissed, etc.

Diaries: Everyday Expressions of Sexual Development

In order to capture everyday expressions of emergent sexual development, participants were invited to report everyday sexual experiencesFootnote 3: “The following questions are about what was most on your mind in the previous week regarding falling in love, flirting, going out, having sex, intimacy, having a romantic relationship, and/or everything related to that. So, write about something that’s on your mind, what you’re thinking about, and what you have strong feelings about.” The participants were given open-ended prompts and were stimulated to write elaborated reports by answering two more open-ended questions: what the adolescent wished for and did during the event, or wished for and wanted to do in case of an internal experience, such as a thought or desire.

Data Analysis

The 2-year quantitative questionnaire data distinguished participants based on their reports of sexual behavior. A two-step cluster analysis for duration, progression, speed, and experience was used to explore whether participants could be grouped into different sexual behavior trajectories. The two-step cluster analysis was chosen, because it can handle continuous and categorical variables. Cluster analysis is an exploratory statistical tool clustering participants into groups; it computes groups based on the degree of association between participants. In addition, the median, minimum, and maximum number of partners for every sexual behavior was calculated.

The 2-year qualitative diaries were used to find overarching themes in everyday experiences. The constant comparative method (CCM) compares the content of the diaries, involving three steps: open, axial, and selective coding (Boeije, 2010). Open coding was used to study every diary to determine what exactly was described by the participant, resulting in tentative codes. The tentative codes were applied to the rest of the sample: axial coding. By selective coding, the data were structured by focusing on the research questions. We identified the importance of the themes quantitatively by calculating the frequency of the codes. In addition, the everyday expressions of sexuality were compared among the sexual behavior trajectories.

Inter-observer reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa. Values > 0.70 were considered to be reliable. Quantitative analyses were done with the use of Excel and SPSS version 20.0. The frequency of participants reporting a topic at least once, as well as the number of diary reports, are presented in percentages in order to compare the relative number of reports between the sexually active and non-active trajectories. For example, “Ten percent of the non-active participants reported in 40% of the diary reports about uncertainties” means 10% of all the non-active participants reported about uncertainties and these non-active participants reported, as a whole, a total of 40% vis-a-vis uncertainties relative to all the diary reports that the non-active participants reported. Quantitative analyses were performed using t test and Fisher’s exact test to examine age and gender differences, respectively. A Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the clusters on the median number of diary reports. Quotations from individual participants are illustrated by numbers, from P01 for participant 01, to P45 for participant 45.

Results

Questionnaires: Sexual Behavior Trajectories

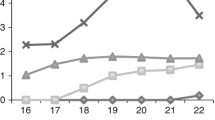

Two-step cluster analysis on duration, progression, speed, and experience identified three sexual trajectories, the characteristics of which are shown in Table 1.

The majority of the participants showed a non-active sexual behavior trajectory (n = 29; 64%). Although a few reported once having kissed someone, most participants in this trajectory reported no sexual activities during the 2-year period. The other participants were sexually active, resulting in two sexual behavior trajectories. About one-third of participants showed a gradual sexual behavior trajectory with participants developing more sexual activities step-by-step over the 2-year period (n = 12; 27%). A minority of the participants showed a fast trajectory, experiencing all new sexual behaviors in a short period of time (n = 4; 9%). Within a few months, they jumped from never kissed someone to going further than fondling underneath clothing, such as performing or receiving manual sex or having vaginal intercourse.

All participants in the non-active sexual behavior trajectory were participants who mentioned no (or minor) sexual behavior (from French-kissing to fondling underneath clothing) in the questionnaire. These participants were not sexually active, based on the items in the questionnaire. It should be mentioned, however, that, in the diary descriptions, these participants did report about sexual experiences. In this sense, the term “non-active” seems not quite right. Still, for reasons of clarity, we will call those participants, clustered together as having no (or minor) experiences with explicit sexual behavior (from French-kissing to fondling underneath clothing) based on the questionnaire, non-active participants.

The median, minimum, and maximum number of partners for every sexual behavior was calculated. On average, those adolescents experiencing more intimate sexual behavior reported fewer partners. The adolescents who had French-kissed had a median of three partners (range, 1–7). The adolescents who had fondled over clothing had a median of two partners (range, 1–4). Subsequently, those who had fondled underneath the clothing had a median of one partner (range, 1–3). Finally, adolescents who had gone further than fondling over clothing had a median of one partner (range, 1–2).

Participants having a non-sexually active trajectory (M age = 15.6) and gradual sexual behavior trajectory (M age = 16.6) did not significantly differ for gender or age (respectively, p = .694; t(39) = 1.56, p = .128). The fast sexual behavior trajectory consisted of girls only, who had a mean age of 16.4 years.

Diaries: Everyday Expressions of Sexual Development

Participants described a total of 347 sexual experiences. Participants in the non-active sexual trajectory (Mdn = 4) reported fewer sexual experiences in their diaries, when compared to the sexually active (Mdn = 9) trajectories (U = 335.5, p = .014). At the end of the research period, 5 out of the 28 non-active participants ended up reporting no sexual experience. They reported everyday issues about family, peers, school, and leisure-time activities, but nothing about sexuality. These five participants were excluded from further analyses, because their everyday expressions of sexual development could not be studied. Consequently, the study sample consisted of 40 participants, and the following analyses were based on 24 for the non-sexually active group of participants. The 40 remaining participants were 30 girls and 10 boys, and the average age was 15.7 years (SD= 1.5).

Qualitative analysis revealed the following themes in the diaries: (1) romantic versus physical aspects of sexuality; (2) desires; (3) uncertainties; and (4) social context (see Table 2 for an overview).

Romantic and Physical Aspects of Sexuality

All participants reported in 89% of the diaries about romantic aspects of sexuality, such as liking someone, romantic relationships, and being in love. Likewise, all participants within each sexual behavior trajectory reported at least once on the romantic aspects of sexuality (non-active 93% of the reports; gradual 79% of the reports; fast 97% of the reports).

Regarding the physical aspects of sexuality, 45% of all participants (n = 18) reported in 20% of the diaries about physical sexual activities. The sexually active participants (i.e., gradually and fast sexually active participants) reported in their diaries more about physical aspects of sexuality than did non-active participants (gradual 92% of sample, 39% of the reports; fast 26% of sample, 50% of the reports; non-active 5% of the sample, 22% of the reports).

Desires

Diary reports were coded as desires in any situation where the adolescent mentioned a desire, that is, where an adolescent explicitly referred to wanting, wishing, or desiring something. We will discuss the importance of desires quantitatively (number of desires) within the different sexual behavior trajectories and then focus on two main desires: the desire for contact with a (future) romantic partner and for physical contact.

In general, most of the participants (83%) expressed their desires and wishes in half of the diary entries (53%). Many of non-active (74%), gradual (92%), and fast (100%) participants reported their desires in approximately half of their diary reports: 54, 57, and 43%, respectively. As indicated, two main desires could be distinguished.

First, 60% of all participants reported the desire to make contact with a (future) romantic partner in 24% of their reports. For example, a 16-year-old sexually non-active boy reported (P02): “(…) I want her to like me. (…) Anyway, I want to talk to her (…).” Likewise, a 15-year-old girl with a gradual sexual trajectory reported (P04): “(…) I wanted to be with him so we could just talk about stuff with each other…Just to have fun being together, you know?” A 16-year-old girl with a fast trajectory showed that she desired contact with her potential romantic partner and wrote (P09): “(…) I wanted to see him as soon as possible.” About 60–70% of the non-active (57%), gradual (62%), and fast (75%) participants reported having a desire to make contact with a (future) romantic partner in approximately one-quarter of the diaries (non-active 26%, gradual 24%, fast 15%).

Second, less than half of the participants (40%) explicitly expressed their desire to have physical contact, broadly defined as ranging from less intimate to more intimate sexual behaviors (12% of the reports). Twenty-five percent of those participants, who wrote about their desire for physical contact, described their desire for French-kissing (6% of the reports), 18% for hugging (4% of the reports), and 13% for sexual intercourse (3% of the reports). Participants described their desire to have physical contact mostly in the context of longing for their (potential) romantic partner after not seeing each other for a while; there were some participants who desired to have sexual contact to make up for a previously negative situation. For example, a 17-year-old boy with a gradual trajectory reported (P07): “I had a fight with my girlfriend. It makes me feel a bit weird. I want to go to her, and hug her.”

Several participants desired physical contact in the context of celebrating a party, feeling attractive or desired, or having or starting a romantic relationship. For example, a 15-year-old girl with a gradual trajectory said (P25): “We went to the movies. During the movie, he asked me if I wanted to go steady with him. Then and there, I wanted to kiss and hug him.”

Except for one, all gradual participants reported the desire for sexual contact (92% of gradual participants, 23% of the reports). This was more than for non-active (17% of non-active participants, 4% of the reports) and fast (25% of fast participants, 13% of the reports) participants. Even though the fast participants developed rapidly from less to more intimate behaviors, most of them did not mention desiring physical contact in their everyday experiences.

Uncertainties

When participants referred to uncertainties, hesitations, or insecurities with respect to their sexual development, the report was coded as uncertainty. First, we will discuss the number of uncertainties in general and those relative to the three sexual trajectories. Second, two main uncertainties emerged from the data: uncertainty about liking (or being liked by) a significant other and uncertainty about physical contact.

In general, 60% of all participants expressed uncertainties in 28% of the diary entries. Uncertainties were significantly more profound within the active trajectories than the non-active trajectories. Fast participants (100% of fast, 46% of the reports) reported the most uncertainties compared to gradual participants (62% of the gradual, 34% of the reports) and non-active participants (52% of the non-actives, 19% of the reports).

First, 45% of all participants reported uncertainties about liking (or being liked by) a significant other in 10% of the diaries. Participants reported uncertainties about liking (or being liked by) a significant other in several contexts. The uncertainty could be because of a feeling that the other person did not like him/her (anymore). For example, a 15-year-old non-active girl mentioned her uncertainty about a boy (P05): “ (…) he likes me too… At least I thought he did. All of a sudden he was nasty, and I didn’t know why. One week went by, and I couldn’t deal with it anymore, so I asked him about it (…).”

In addition, the opinion of peers could serve as a source of uncertainty. For example, a 17-year-old non-active girl mentioned (P19): “Lately, I’ve been app-ing with a boy I used to know. (…) My friends keep talking me into doing it, so that’s why I have a lot of doubts about whether I like him or not.” Furthermore, liking a person who was already a “regular” friend served as a source of uncertainty. A 16-year-old non-active boy reported (P29): “I’m beginning to really like a close friend of mine, but I don’t know whether this is a good idea or not. I don’t want to ruin our friendship.”

With respect to uncertainties about liking (or being liked by) a significant other, more fast participants (75%) reported at least once about this uncertainty as opposed to non-active (35%) and gradual participants (33%). However, non-active, gradual, and fast participants mentioned uncertainties about liking (or being liked by) a significant other in 8, 12, and 16% of the reports, respectively. Therefore, in this sense, the participants did not substantially differ from each other.

Second, 18% of the participants reported uncertainties about engaging in physical contact in 5% of the diaries. A 16-year-old girl with a gradual trajectory mentioned that she wasn’t sure what her boundaries were (P03):

Well, actually, last time we went further than just kissing, and I haven’t figured out how far I want to go. It felt good; that wasn’t the problem. I just don’t know how far I want to go and when I’ll cross my line. I think about that a lot lately.

Another 15-year-old girl with a fast trajectory mentioned her doubts about whether or not to have sexual intercourse (P40): “Actually, he wants to do it already. I want to, too. Except that, well, I sort of don’t want to, because I’m afraid he won’t want me anymore after that.”

Gradually sexually active participants (50% of sample, 11% of reports) reported the most about uncertainties in the context of physical sexual behaviors. Only one participant of the fast cluster reported uncertainties about physical sexual behaviors. Non-actives reported the least about physical sexual behaviors. In fact, none of the non-active participants reported any uncertainties about physical sexual behaviors.

References to the Social Network

Diary reports referring to the social environment were coded as social network. First, we calculated the number of references to the social network, and we present differences between the sexual trajectories. Second, the content of the diaries referring to social networks was differentiated according to social context, that is, peer, family, or media. Third, the diary content revealed that the social network could function as a source of negativity as well as of social support or stimulation.

In general, a total of 63% reported at least once about their social network within the context of their sexual experiences. Fast participants reported most about their social network (100% of sample, 41% of reports), followed by non-active participants (65% of the sample, 23% of the reports), and then gradual participants (46% of the sample, 12% of the reports).

With respect to the reference group, participants mostly described peers (58% of the sample; 16% of the reports), followed by family (18% of the sample; 3% of the reports), and then media (5% of the sample; 1% of the reports). All fast participants (100%) reported about peers in 28% of the reports. A total of 70% of non-active participants reported about peers in 17% of the diaries. Gradual participants reported the least about peers. Thirty-three percent of the gradual participants reported in 12% of the reports about peers.

The social network may function as a source of negativity (40% of the sample; 13% of the reports), social support (25% of the sample; 3% of the reports), or stimulation (18% of the sample; 3% of the reports) in the context of sexual development. For example, a non-active 17-year-old girl (P19) reported that the peer group served as a source of negativity, in her case, insecurity: “There are a lot of people I know getting into a romantic relationship…And I’ve still never even kissed anyone yet. I really hate that. Seriously, isn’t there someone out there who likes me?” Further, a non-active 14-year-old boy (P37) described a friend as a source of support: “I talked with a friend of mine about girls and asked him about what you do.” Finally, a 16-year-old girl with a fast trajectory (P09) reported about stimulation from the environment vis-à-vis starting to date: “A friend made a list of boys to choose from. So I started dating one of them. I think I kind of like this one now.”

Discussion

Our study aimed at exploring everyday expressions of the trajectories of adolescents’ sexual behavior by using an elaborated definition of sexuality that incorporated sexual activities as well as internal experiences, such as thoughts and desires, along with romantic aspects without any explicit sexual goal. We examined adolescents’ temporal sequence of sexual behaviors from less to more intimate behaviors and explored the differences in daily sexual expression of sexual behavior trajectories with the use of diaries.

First, this study aimed to extend existing research by examining sexual behavior trajectories longitudinally over a 2-year period using questionnaires. Our longitudinal study showed three sexual trajectories: one non-active trajectory and two sexually active trajectories. Most of the adolescents (n = 29) were found grouped in the non-active sexual trajectory, which encompassed adolescents involved in no or minor sexual behavior. In addition, this study differentiated between two sexually active trajectories. One group of adolescents (n = 12) was clustered into a gradually sexually active trajectory, following a stepwise progression from kissing to fondling, when dressed and undressed, and then going further than that. Another small group of adolescents (n = 4) followed a fast sexual trajectory, rushing into sexual behaviors over a short period of time. These trajectory patterns of adolescents’ sexual development were also found in a previous representative Dutch sample (de Graaf et al., 2009). The percentages of sexually active adolescents (calculated without the non-active trajectory, because de Graaf et al. (2009) did not incorporate non-actives in their sample)—75% gradual and 25% fast trajectories—are approximately similar to 73% linear and 27% nonlinear sexual trajectories found in the previous large-scale Dutch study.Footnote 4 Consequently, this result provides our study with a foundation for possibly generalizing our own results as further support for the theory. Consequently, the results show initial insights into how adolescents with different trajectories experience their sexual development.

The second goal was to examine adolescents’ everyday expressions of their sexual development. Our research showed that sexually active adolescents were more occupied with sexuality in their everyday expressions than non-active adolescents. By analyzing diary descriptions, we gained several insights vis-à-vis the themes involved in how adolescents expressed their own sexual development in their everyday lives. Three global themes emerged from the diary data: everyday desires (83% of all diary reports), uncertainties (60% of all diary reports), and social networks (63% of all diary reports). Active and non-active adolescents differed in their expressions of these experiences: Overall, sexually non-active young people experienced their sexual development only on a romantic level, whereas sexually active young people experienced their sexual development on a romantic as well as on a physical sexual level. In addition, although there were a few sexually non-active young people who reported no everyday expressions about sexuality at all, most sexually non-active young people did experience romantic thoughts, feelings, and desires. These findings demonstrate that the emerging phase of sexual development (i.e., romantic topics) may go unnoticed in research that is solely based on questionnaires.

The finding that young people were, in general, more concerned with the romantic aspects of sexuality than with explicit sex-related topics confirms findings in previous studies (de Graaf et al., 2012; Miller et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1992; Thornton, 1990). Previous research on the romantic aspects of sexuality focused mainly on manifest romantic relationships (Collins et al., 2009). Our study showed that young people were also concerned with (initial) romantic fantasies and thoughts rather than just with actual romantic relationships per se.

The desire to make contact with a significant other occupied a central place in sexual development for sexually active as well as non-active adolescents. However, the desire for physical sexual contact did differ between the active and non-active trajectories. Gradually sexually active adolescents desired physical sexual contact, but non-active adolescents did not. It seems that sexual activities, once experienced, ensure the desire for sexual contact. Gradually sexually active adolescents experience sexual activity and have desires for sexual contact. Perhaps adolescents’ desires are simply realistic; in order to engage in sexual activities, adolescents first need to make contact with a future sexual partner. Consequently, non-active adolescents report a desire for contact but not (yet) for physical sexual activities.

In contrast to all but one of the gradual adolescents, only one of the fast adolescents reported desires for sexual contact. Previous research has shown that feelings of being more entitled to have desires were associated with fewer negative reactions to recent sexual intercourse (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2014). A relatively fast progression of sexual behaviors may not allow enough time for desires for physical sexual contact to develop. It is possible that fast adolescents experience more sexual activity than they actually wish for. Previous research showed that a short time interval between sexual acts limited adolescents’ opportunities to direct their sexual development vis-à-vis their own needs and desires (Rademakers & Straver, 1986; Thompson, 1990). Because of the small number of fast adolescents in this study, future research with more faster-developing adolescents could examine whether enough time to establish desires for physical sexual behavior is critical for healthy sexual development.

In addition to desires, adolescents frequently showed uncertainties in their everyday expressions. Uncertainties became more apparent when adolescents were sexually active. Sexually active adolescents engage in relatively unfamiliar situations, where they have to develop new skills to handle social situations, decide whether or not to engage in romantic or sexual encounters, and communicate their decisions effectively with (potential) romantic or sexual partners. Therefore, it is not surprising that, when compared to sexually non-active adolescents, sexually active adolescents described significantly more uncertainties about liking (or being liked by) a significant other and engaging in physical sexual behaviors. Uncertainties were the most profound within the fast trajectory. Future research could further examine whether high speed, from fewer to more sexual activities, goes hand in hand with more uncertainties about sexuality. More uncertainty in the fast trajectory is in line with earlier research showing that a gradual progression of sexual behaviors is associated with more positive evaluations of sexual experiences (Thompson, 1990). The vast number of uncertainties about romantic aspects of sexuality underscores the importance of incorporating this topic in sexual education programs.

In addition to desires and uncertainties, adolescents regularly referred to their social network in the diary reports. In agreement with the literature, adolescents reported mostly about peers (e.g., talking with peers about romantic experiences) within the context of their sexual experiences (Lefkowitz et al., 2004; Simon et al., 1992). They reported far less often about family (e.g., a conversation about sexuality with a parent) or media (e.g., a television program that mentioned sexuality). Our study showed that the social network, mainly peers, could either serve as a source of uncertainties or as a source of support or stimulation (e.g., a peer stimulating the adolescent to go on a date) in terms of everyday issues about sexual development. Apparently, the peer group does not always have a negative effect (e.g., peer pressure to have sex) on sexual development. In fact, our results showed that the peer group can serve as a support group in handling the relatively new situations accompanying emergent sexual development. These everyday experiences with peers are important in adolescent sexual development because research has shown that friendship experiences can serve as examples for later romantic relationships (Collins et al., 2009). In fact, a recent meta-analysis has shown that adolescents’ perceptions of peers’ sexual behaviors were strongly related to their own sexual activity (van de Bongardt, Yu, Deković, & Meeus, 2015).

The fast adolescents were more concerned with their peers than the gradual adolescents. It could be that a relatively fast progression in sexual activity within a short period of time serves as a source of uncertainties and results in a greater focus on the peer group than gradual adolescents’ experience. Indisputably, interactions with peers contribute to the development of adolescent heterosexual romantic relationships (Feiring, 1996; Furman, 1999; Furman & Shomaker, 2008; Furman, Simon, Shaffer, & Bouchey, 2002; Furman & Wehner, 1994). More insight into positive peer influences in the sense of providing support and advice to adolescents about their sexual development could offer direction for future research and sex education programs.

Strengths, Limitations, and Conclusions

Our findings need to be considered in light of the strengths and limitations of the study. First, our sample size was small and contained a very small number of fast sexually active adolescents. One reason could be that the need for the active permission of parents limited the participation of adolescents. Having a conversation with the parent about the research project was inevitable, since parental consent was needed in order to participate (for ethical reasons). The small number of fast sexually active adolescents could also be due to the fact that only adolescents with a native-Dutch background participated in the study. Previous research has shown that Dutch adolescents with a non-native background are more likely to follow a fast trajectory (de Graaf et al., 2009). However, the findings in our study contribute to sexual trajectories found in previous research. Research can make generalizations of study results to the population or to the theory (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Whereas our findings are fragile in generalization to the population, our study’s strength lies in making a generalization to the theory, and, in this way, the research findings have added to our insights into how adolescents develop sexually. Still, the results of this study should be interpreted in the context of Dutch society.

Second, it is possible that participants were primed to write about the sample topics presented in the diary question. However, participants had to write in an open-ended way about a recently experienced romantic and sexual topic, which makes the priming effect different from questionnaires about general topics with no explicit situation to refer to.

Third, because of ethical reasons, sexual behavior was assessed adaptively from a progression of less to more intimate sexual behaviors, making it impossible to skip one form of sexual behavior. This adaptive nature ignores those adolescents who experience more intimate behaviors before less intimate behaviors. Nevertheless, this sequential appearance of sexual behavior questions produces more reliable answers and less reactivity (i.e., repeated exposure may influence adolescents to answer “yes,” while actually not performing the sexual act, and may trigger adolescents to perform these sexual acts, while initially not having planned on doing so). Reactivity could be more important in our study (more than in other longitudinal studies) because of the very intensive nature of the data collection method (i.e., asking about sexual behaviors six times over a 2-year period). Furthermore, extensive research has shown that adolescents consistently follow trajectories from less to more intimate behaviors (e.g., de Graaf et al., 2009; Halpern et al., 2000; Jakobsen, 1997; Lam et al., 2002; O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005; Shtarkshall et al., 2009; Smiler et al., 2011; Wiegerink et al., 2010). In our study, however, one limitation is that a non-sexual behavior trajectory could include sexually experienced participants who did not follow a stepwise progression (i.e., who had not kissed anyone but had had experiences with fondling over and underneath clothing). Inspection of the diary and questionnaire data did not result in any contradictory information about sexual experiences (i.e., writing about more intense romantic or sexual experiences in the diaries, while at the same time reporting no sexual experiences in the questionnaires).

Fourth, following the preceding limitation, our study sample identified participants as (predominantly) heterosexual and so it does not take sexual minorities into account. Sexual minorities are less likely to follow the expected sequence from kissing to sexual intercourse (Fish & Pasley, 2015; Smiler et al., 2011). Future studies might include the sex of the partner when analyzing the temporal sequence of sexual behaviors.

Fifth, reliable answers are a challenge within research about adolescence and sexuality, regardless of the research method. The longitudinal character of this study made the results more reliable: Adolescents with inconsistent answers on the questionnaire over the six waves (i.e., 2 years) were excluded from the sample. It should be noted, however, that interesting information might be gained from studying adolescents who do not respond consistently. The different research methods made it also possible to compare the content of the diaries with the questionnaire data (i.e., whether both assessments were compatible with each other).

Sixth, only participants who were willing to reveal their personal lives for at least 2 years were included in the study. It is possible that the adolescents in our study are different from other adolescents. Nonetheless, the willingness of these participants to participate gave us the opportunity to capture rich, detailed data from everyday lives that cannot always be captured by pure observation or questionnaire data. Subsequently, information from other resources, such as the partner of the participant, may provide valuable information on adolescents’ sexual behavior.

Despite these limitations, our findings contribute to research on emergent sexual development as a normative transition within adolescence. The vast amount of romantic expressions in the diaries could guide future studies so as to incorporate romantic aspects in their research. In addition, adjusting information to adolescents’ personal interests is essential for sexual education programs to succeed. Therefore, the idiosyncratic expressions of the main themes, desires, uncertainties, and social context (especially peers) could be of importance in tailoring sexual education to the individual level. This research could help support formal (e.g., school) and informal (e.g., family) sexual education by including a reflection on the personal experiencing of current or future romantic relationships and sexuality, in addition to a narrow view of sexuality, which only includes the biology of the human body and safe sex. Sexual education that normalizes sexual exploration in adolescence and discusses internal experiences of sexual development, incorporating the romantic aspects, may help adolescents process and consider their preferences for different sexual and romantic acts and, as a consequence, contribute to healthy sexual development. Future research could examine further whether it is best for adolescents to take their time exploring and considering sexual acts one by one, and developing desires for physical sexual contact before actually performing these sexual activities.

Notes

In the Netherlands, the high school level educational system is roughly divided into three main types: prevocational secondary education (here designated “low-education”), senior general secondary education, and pre-university education (here designated “high-education”).

During the six waves of data collection, sexual attraction was studied using two questions. Five participants (one boy) mentioned at least once “yes” to the first question: “Some people are romantically and/or sexually attracted to someone of the same sex. A boy (man) is attracted to a boy (man). And a girl (woman) is attracted to a girl (woman). Do you feel romantically and/or sexually attracted to someone of the same sex?” In addition, we asked a second question “Right now, do you feel more romantically and/or sexually attracted to boys (men) or girls (women)?” The girls answered this question on a 5-point Likert scale with “only boys” or “mostly boys” and the boy reported “only girls.” Therefore, we describe the sample as predominantly heterosexual.

Because of the innovative nature of the diary study, a pilot study was conducted using a sample of 183 adolescents at a vocational training school, who filled in the diary once without any financial compensation for their participation. Results showed that the adolescents understood the questions well and were motivated to report on private personal experiences. Minimal revisions were made to the wording of questions as used in this study.

The participants included in the fast trajectory of our study have a rapid progression from less to more sexually intimate experiences and show similarities with one part of the “nonlinear” trajectories of the study by de Graaf et al. (2009). To be specific, de Graaf et al. identified “nonlinear” trajectories as either having all new sexual experiences in a fast progression from less to more sexually intimate experiences, or as having more sexually intimate experiences before less sexually intimate ones.

References

Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. London: Sage.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101, 568–586.

Collins, W. A., Welsh, D. P., & Furman, W. (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459.

Connolly, J., & McIsaac, C. (2011). Romantic relationships in adolescence. In M. K. Underwood & L. S. Rosen (Eds.), Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence (pp. 180–205). NewYork: Guilford Press.

de Graaf, H., Kruijer, H., Van Acker, J., & Meijer, S. (2012). Seks onder je 25e. Seksuele gezondheid van jongeren in Nederland anno 2012. [Sex under the age of 25. Sexual health of young people in 2012]. Delft: Eburon.

de Graaf, H., & Picavet, C. (2018). Sexual trajectories of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the Netherlands. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1209–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0981-x.

de Graaf, H., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Meijer, S., Woertman, L., & Meeus, W. (2009). Sexual trajectories during adolescence: Relation to demographic characteristics and sexual risk. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9281-1.

De Looze, M., Constantine, N. A., Jerman, P., Vermeulen-Smit, E., & Ter Bogt, T. (2014). Parent-adolescent sexual communication and its association with adolescent sexual behaviors: A nationally representative analysis in the Netherlands. Journal of Sex Research, 52, 257–268.

Diamond, L. M. (2012). The desire disorder in research on sexual orientation in women: Contributions of dynamical systems theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9909-7.

Edwards, W. M., & Coleman, E. (2004). Defining sexual health: A descriptive overview. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33, 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026619.95734.d5.

Feiring, C. (1996). Concept of romance in 15-year-old adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 181–200.

Fish, J. N., & Pasley, K. (2015). Sexual (minority) trajectories, mental health, and alcohol use: A longitudinal study of youth as they transition to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1508–1527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0280-6.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12, 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363.

Furman, W. (1999). Friends and lovers: The role of peer relationships in adolescent heterosexual romantic relationships. In W. A. Collins & B. Laursen (Eds.), Relationships as developmental contexts: The 30th Minnesota Symposium on Child Development (pp. 133–154). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Furman, W., & Shomaker, L. B. (2008). Patterns of interaction in adolescent romantic relationships: Distinct features and links to other close relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 771–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.007.

Furman, W., Simon, V. A., Shaffer, L., & Bouchey, H. A. (2002). Adolescents’ working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development, 73, 241–255.

Furman, W., & Wehner, E. A. (1994). Romantic views: Toward a theory of adolescent romantic relationships. In R. Montemayor, G. R. Adams, & G. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Relationships during adolescence: Advances in adolescent development (Vol. 6, pp. 168–175). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Halpern, C. T., Joyner, K., Udry, J. R., & Suchindran, C. (2000). Smart teens don’t have sex (or kiss much either). Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 213–225.

Hansen, W. B., Paskett, E. D., & Carter, L. J. (1999). The Adolescent Sexual Activity Index (ASAI): A standardized strategy for measuring interpersonal heterosexual behaviors among youth. Health Education Research, 14, 485–490.

Hilber, A. M., & Colombini, M. (2002). Promoting sexual health means promoting healthy approaches to sexuality. Sexual Health Exchange, 4, 1–2.

Jakobsen, R. (1997). Stages of progression in noncoital sexual interactions among young adolescents: An application of the Mokken Scale Analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 537–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502597384776.

Lam, T. H., Shi, H. J., Ho, L. M., Stewart, S. M., & Fan, S. (2002). Timing of pubertal maturation and heterosexual behavior among Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016228427210.

Lefkowitz, E. S. (2002). Beyond the yes-no question: Measuring parent-adolescent communication about sex. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 97, 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.49.

Lefkowitz, E. S., Boone, T. L., & Shearer, C. L. (2004). Communication with best friends about sex-related topics during emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000032642.27242.c1.

Miller, B. C., Norton, M. C., Curtis, T., Hill, E. J., Schvaneveldt, P., & Young, M. H. (1997). The timing of sexual intercourse among adolescents. Youth & Society, 29, 54–83.

O’Sullivan, L. F., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2005). The timing of changes in girls’ sexual cognitions and behaviors in early adolescence: A prospective, cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.019.

Parker, R., Wellings, K., & Lazarus, J. V. (2009). Sexuality education in Europe: An overview of current policies. Sex Education, 9, 227–242.

Rademakers, J., & Straver, C. (1986). Van fascinatie naar relatie. Het leren omgaan met relaties en seksualiteit in de jeugdperiode [From fascination to relationship. Learning to deal with romantic relationships and sexuality in the period of youth]. Zeist: Nisso.

Russell, S. T. (2005). Introduction to positive perspectives on adolescent sexuality: Part 1. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 2, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2005.2.4.1.

Schalet, A. T. (2011). Beyond abstinence and risk: A new paradigm for adolescent sexual health. Women’s Health Issues, 21, S5–S7.

Schwartz, I. M. (1999). Sexual activity prior to coital initiation: A comparison between males and females. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28, 63–69.

Shtarkshall, R. A., Carmel, S., Jaffe-Hirschfield, D., & Woloski-Wruble, A. (2009). Sexual milestones and factors associated with coitus initiation among Israeli high school students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 591–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9418-x.

Simon, R. W., Eder, D., & Evans, C. (1992). The development of feeling norms underlying romantic love among adolescent females. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55, 29–46.

Smiler, A. P., Frankel, L. B. W., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2011). From kissing to coitus? Sex-of-partner differences in the sexual milestone achievement of young men. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.08.009.

Smiler, A. P., Ward, L. M., Caruthers, A., & Merriwether, A. (2005). Pleasure, empowerment, and love: Factors associated with a positive first coitus. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 2, 41–55.

Thompson, S. (1990). Putting a big thing into a little hole: Teenage girls’ accounts of sexual initiation. Journal of Sex Research, 27, 341–361.

Thornton, A. (1990). The courtship process and adolescent sexuality. Journal of Family Issues, 11, 239–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251390011003002.

Tolman, D. L., & McClelland, S. I. (2011). Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 242–255.

van de Bongardt, D., Yu, R., Deković, M., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2015). Romantic relationships and sexuality in adolescence and young adulthood: The role of parents, peers, and partners. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 497–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2015.1068689.

van Geert, P. L. C. (2002). We almost had a great future behind us. The contribution of non-linear dynamics to developmental-science-in-the-making. Developmental Science, 1, 143–159.

Waylen, A. E., Ness, A., McGovern, P., Wolke, D., & Low, N. (2010). Romantic and sexual behavior in young adolescents: Repeated surveys in a population-based cohort. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30, 432–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609338179.

Weaver, H., Smith, G., & Kippax, S. (2005). School-based sex education policies and indicators of sexual health among young people: A comparison of the Netherlands, France, Australia and the United States. Sex Education, 5, 171–188.

Wiegerink, D. J., Stam, H. J., Gorter, J. W., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Roebroeck, M. E. (2010). Development of romantic relationships and sexual activity in young adults with cerebral palsy: A longitudinal study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91, 1423–1428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.011.

Williams, T., Connolly, J., & Cribbie, R. (2008). Light and heavy heterosexual activities of young Canadian adolescents: Normative patterns and differential predictors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 145–172.

World Health Organization. (2012). Health topics: Sexual health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/topics/sexual_health/en/.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Helfand, M. (2008). Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: Developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Developmental Review, 28, 153–224.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., See, L., & O’Sullivan, L. (2014). Young women’s satisfaction with sex and romance, and emotional reactions to sex: Associations with sexual entitlement, efficacy, and situational factors. Emerging Adulthood, 3, 113–122.

Acknowledgements

Data for the current study were collected as part of a larger project in the Netherlands called “Project STARS” (Studies on Trajectories of Adolescent Relationships and Sexuality), which is funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Fund for Scientific Research on Sexuality (FWOS) (NWO Grant No. 431-99-018).

Funding

This study was funded by Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research (NWO) and the Fund for Scientific Research on Sexuality (FWOS) (NWO Grant No. 431-99-018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dalenberg, W.G., Timmerman, M.C. & van Geert, P.L.C. Dutch Adolescents’ Everyday Expressions of Sexual Behavior Trajectories Over a 2-Year Period: A Mixed-Methods Study. Arch Sex Behav 47, 1811–1823 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1224-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1224-5