Abstract

Children’s toy play is at the foundation of child development. However, gender differentiation in early play experiences may result in gender differences in cognitive abilities, social interactions, and vocational choices. We investigated gender-typing of toys and toys’ propulsive properties (e.g., wheels, forward motion) as possible factors impacting children’s toy interests, perceptions of other children’s interests, and children’s actual toy choices during free play. In Studies 1 and 2, 82 preschool children (42 boys, 40 girls; mean age = 4.90 years) were asked to report their interest and perceptions of other children’s interests in toys. In Study 1, masculine, feminine, and neutral toys with and without propulsive properties were presented. Children reported greater interest in gender-typed toys and neutral toys compared to cross-gender-typed toys. In Study 2, unfamiliar, neutral toys with and without propulsive properties were presented. Propulsive properties did not affect children’s interest across both studies. Study 3 was an observational study that assessed toy preferences among 42 preschool children (21 males, 21 females, mean age = 4.49 years) during a play session with masculine, feminine, and neutral toys with and without propulsive properties. Gender-typed toy preferences were less apparent than expected, with children showing high interest in neutral toys, and girls playing with a wide variety of masculine, feminine, and neutral toys. Gender differences in interest for toys with propulsion properties were not evident. Overall, gender differences in children’s interest in toys as a function of propulsion properties were not found in the three experiments within this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children’s toy play is an integral aspect of their childhood and their development. Gender differences in play appear to be large (d = 2.0, Davis & Hines, 2015), with boys and girls engaging in different play styles and playing with different toys (Campenni, 1999; Carter & Levy, 1988; Martin, Eisenbud, & Rose, 1995; Miller, 1987). Masculine and feminine toys (i.e., toys culturally associated with boys and girls, respectively) often have different characteristics (Alexander & Hines, 2002). Masculine toys include toys vehicles, building toys, sports equipment, and weapons and are associated with competition, violence, movement, and excitement (Blakemore & Centers, 2005). Feminine toys include baby and fashion dolls, domestic role play toys, and princess paraphernalia and are associated with a focus on one’s appearance, social roles, and caretaking duties. Gender-typed toy play, which is especially pronounced for boys (Cherney, Kelly-Vance, Glover, Ruane, & Ryalls, 2003; Cherney & London, 2006), has been confirmed to elicit different cognitive skills during play. For example, children use higher levels of cognitive complexity when playing with feminine toys than with masculine toys (Cherney et al., 2003). Moreover, gender differences in toy play have been linked to gender differentiation in the development of children’s spatial skills (De Lisi & Wolford, 2002; Levine, Ratliff, Huttenlocher, & Cannon, 2012), literacy (Wolter, Glüer, & Hannover, 2014), gross and fine motor skill (Pellegrini & Smith, 1998), activity levels (Eaton, Von Bargen & Keats, 1981), social skills (Hei Li & Wong, 2016), and occupational aspirations (Sherman & Zurbriggen, 2014). Frequently, toy preference studies include masculine toys that have propulsive properties which encourage vigorous forward movement. Thus, propulsion may be a feature of masculine toys that make them more attractive to boys than to girls. The primary aim of this study was to disentangle the impact of the gender-type and propulsive characteristics of toys in their attractiveness to children.

Children develop a preference for gender-typed toys at a young age, and these differences become more pronounced through development. At 6 months, although both boys and girls show a visual preference for dolls over trucks, boys looked longer at trucks than did girls (Alexander, Wilcox, & Woods, 2009; Woods, Wilcox, Armstrong, & Alexander, 2010). These looking time differences continue through infancy into toddlerhood (Jadva, Hines, & Golombok, 2010). In the first 2 years of life, girls spend more play time with feminine toys than do boys and boys spend more play time with masculine toys than do girls (Alexander & Saenz, 2012; Servin, Bohlin, & Berlin, 1999). During preschool, boys increased their play with masculine toys and decreased dramatically their play with feminine toys, whereas girls’ play preferences changed little (Davis & Hines, 2015). These patterns of boys choosing gender-typed activities and girls having more variation in their play are found even when neutral toys are included as toy choices (Cherney et al., 2003; Doering, Zucker, Bradley, & MacIntyre, 1989; Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). It may be the propulsive characteristics of toys that underlie findings of boys’ interest in masculine toys.

There are multiple perspectives concerning the mechanisms by which this early gender differentiation of toy play occurs. Social theorists posit that socializing agents such as parents, peers, media, and marketing link certain toys to each gender, and they note the impact of the reinforcement and punishment that children receive for engaging in gender-typed toy play and cross-gender-typed toy play (Leaper & Friedman, 2007; Lindsey & Mize, 2001). Parents are likely to provide gendered environments, buy gender stereotyped toys, and encourage gender-typed play (Idle, Wood, and Desmarais, 1993; Leaper, 2002; Sutfin, Fulcher, Bowles, & Patterson, 2008). Gender segregated peer groups may initially be a result of gender-typed toy and play interests, in that children with similar interests begin to play together and form friendships (Maccoby, 1998; Martin, Fabes, & Hanish, 2014; Martin et al., 2013). In addition, media may be playing an increasing role in shaping gender-typed toy preferences as the number of toys marketed to one gender or another has increased dramatically since the 1980s (Sweet, 2013).

Cognitive explanations for gender-typed toy play acknowledge the associations between gender and toys constructed by society and socializing agents, but also that children cognitively construct gender stereotypes about toys (Bigler & Liben, 2007; Liben & Bigler, 2002; Martin & Halverson, 1981). Recent work stemming from this constructivist perspective determined that cultural appropriateness of toys, explicit verbal labels, and implicit color labels are influential and that children cognitively process these social cues when constructing personal interests in toys (Weisgram, 2016; Weisgram, Fulcher, & Dinella, 2014; Wong & Hines, 2014).

Other research suggests the possibility that hormonal or genetic influences could impact toy choice and play preferences (Jadva et al., 2010). For example, girls who were exposed to elevated levels of androgens in the womb have an increased level of masculine toy play (Berenbaum & Hines, 1992), male playmates, and masculine occupational aspirations (Servin, Nordenstöm, Larsson, & Bohlin, 2003) than did their unaffected sisters. However, boys with CAH toy preferences did not differ from boys without CAH (Pasterski et al., 2005). Recent attempts to disentangle the role of biology versus parental socialization in toy choices made by girls with CAH have mixed findings about the prevalence of parents encouraging gender-typical versus cross-typed toy play (Pasterski et al., 2005; Wong, Pasterski, Hindmarsh, Geffner, & Hines, 2013). This can be a result of the different assessment methods used in the studies, such that the former observed children in a laboratory setting using a designated set of toys, while the latter used a questionnaire assessing daily play behaviors. However, findings consistently suggest that parental socialization cannot fully explain these girls’ increased interest in masculine toy. Empirical investigations also suggest that male and female non-human primates choose to play with toys that are deemed by human culture to be associated with males and females, respectively (Alexander & Hines, 2002). Thus, it has been hypothesized that gender-typed toy preferences may reflect hormonally influenced behavioral and cognitive biases (Hassett, Siebert, & Wallen, 2008).

Across these perspectives, studies of children’s and non-human primates’ gendered toy choices consistently include masculine toys that encourage propulsive movement, such as trucks (Alexander & Hines, 2002; Berenbaum & Hines, 1992; Jadva et al., 2010). For example, male vervet monkeys more than female monkeys played more with a vehicle, even moving it along the ground similar to the way children play with vehicles (Alexander & Hines, 2002). Female monkeys played more often with a human doll more than males did (although both males and females played with a stuffed animal doll). In a study with rhesus monkeys, the monkeys were presented with masculine toys (wheeled toys) and feminine toys (a combination of plush toys, which are often considered to be neutral, and dolls which are feminine toys) (Hassett et al., 2008). Male monkeys were more interested in the wheeled toys than in the plush toys, and female monkeys showed more variability in their toy preferences. These findings have been interpreted as evidence that males’ interests in masculine toys are a result of their predisposed interest in propulsion movements, a characteristic inherent in wheeled toys and vehicles (Benenson, Tennyson, & Wrangham, 2011).

Research with infants suggests that propulsive motion is more common in males than in females and could be biologically based (Benenson, Liroff, Pascal, & Cioppa, 1997). For example, after observing a model who hit a balloon (an action that includes a forward thrusting motion) infant boys were more likely than were girls to move their arms to also hit the balloon (Benenson et al., 2011). It is true that vehicles are considered strongly masculine toys (Blakemore & Centers, 2005), and these toys require propulsion in order for them to move. Thus, it may be that boys show greater interest in vehicles and other masculine toys because such toys encourage propulsive actions.

The Present Studies

In the current studies, we systematically investigated two possible factors impacting children’s toy interests and choices: (1) gender-typing of toys and (2) toys’ propulsive properties. In all three studies, we controlled the color of the toys to remove the potential impact of color as an implicit gender label.

In Study 1, we presented children with familiar masculine, feminine, and neutral toys that either afford propulsion or do not afford propulsion and assessed their interest in each toy via an interview. We also asked them to predict other girls’ and boys’ interests. We expected that children would be more interested in gender-typed toys that were congruent with their gender group than in cross-gender-typed toys. If flexibility in gender-typed interests were to be present, we would expect it to be true for girls more than boys. Further, we expected that children would predict other girls and boys would have this same congruent pattern of interest. We also expected that boys, more than girls, would prefer toys with propulsion properties than toys with non-propulsion properties. Thus, we expected an interaction would exist between the child’s gender, the gender-type of the toy, and whether the toy had propulsive or non-propulsive properties.

In Study 2, we presented children with unfamiliar gender-neutral toys that either afford propulsion or do not afford propulsion, thus isolating the causal role of propulsion properties in determining children’s interests, and their predictions of other boys’ and girls’ interests. Here, we also expected that boys, more than girls, would prefer toys with propulsion properties than toys with non-propulsion properties.

Lastly, in Study 3, we presented children with masculine, feminine, and neutral toys that either afford or do not afford propulsion and observed their length of play in a free-play situation. This methodology allows for an assessment of children’s preferences through their actual behaviors. We expected that the same pattern of toy interest hypothesized in Study 1 would be found in Study 3.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Participants for both Study 1 and Study 2 were recruited from two preschools on the East Coast of the United States. The sample included 82 preschool children (42 boys, 40 girls) ranging in age from 4 to 6 years (mean age = 4.90). Children were primarily European American (73.5%) with African American (4.8%), Hispanic American (3.6%), Asian American (4.8%), and Indian American (2.4%) ethnic groups also represented (ethnicity was not reported for 10.8% of the sample). Parent consent was obtained for all participants. Children were individually invited to participate in the study, and verbal assent was obtained prior to the onset of the study protocol. All of the children approached agreed to participate.

Procedure

Based on procedures standardized by Weisgram et al. (2014), children were presented with one of two sets of 10 different toys including masculine-typed toys, feminine-typed toys, and gender-neutral toys. Half of the toys of each type had propulsive properties and half did not. Children had the chance to examine and explore each toy for 30 s, and then, with the toy in front of them, indicated their interest in the toy, their perception of other boys’ interests, and their perception of other girls’ interests. Each interview took place in a quiet space without the presence of other children.

Materials

Twenty different toys (divided into two sets of 10) were used in this study. All toys were painted white to remove any implicit gender label provided by toy color. Four toys within each of the following gender-typed categories (drawn from Blakemore & Centers, 2005) were selected: strongly feminine, moderately feminine, neutral, moderately masculine, strongly masculine. Within each of those five categories, half of the toys had propulsive properties (e.g., princess carriage and baby stroller for strongly feminine, Matchbox car and Tonka truck for strongly masculine) and the other half did not have propulsive properties (e.g., tea set and princess costume for strongly feminine, tool bench and superhero costume for strongly masculine). See Table 1 for the complete set of toys by gender-typed category and propulsion. For the purpose of data analysis, we collapsed the data across toy type such that results for the moderately feminine toy and strongly feminine toy were averaged to create a composite score as were results for the moderately masculine and strongly masculine toys. In this way, we could ensure that the masculine toys and feminine toys were approximately the same level of gender-typing.

Measures

Personal interest was assessed by asking the child “How much do you like to play with this toy?” Perception of others’ interest was assessed by asking the child “How much do other boys [girls] like to play with this toy?” All questions were assessed on a four-point scale ranging from “Not at all” (1) to “Very Much” (4). Children’s responses were obtained using methods based on Weisgram et al. (2014) and Martin et al. (1995), which include providing children with notecards with words and schematics that represent the answer options, and thus children can reply verbally or through pointing manually.

Results

For each dependent variable, a 2 (Gender) × 3 (Toy Type: Masculine, Feminine, Neutral) × 2 (Propulsion Condition: Propulsion, No Propulsion) mixed effects ANOVA was conducted.

Personal Interest

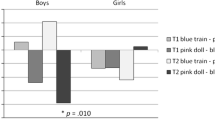

Figure 1 shows the mean ratings as a function of Gender, Propulsion Condition, and Toy Type. The ANOVA revealed a significant Gender × Toy Type interaction, F(2, 152) = 19.63, p < .001. Contrasts indicated that, for boys, personal interest was significantly higher for masculine and neutral toys (which did not differ from one another, p = .90) than for feminine toys (p < .001 for both significant contrasts). Among girls, contrasts indicated that their personal interest was significantly higher for feminine and neutral toys (which did not differ from one another, p = .90) than for masculine toys (p = .001 for both contrasts) (see Fig. 1).

Perception of Others’ Interest

Rating of Boys’ Interests

Table 2 shows the boys’ interest ratings as a function of Gender, Propulsion Condition, and Toy Type. The ANOVA revealed a significant Toy Type × Propulsion interaction, F(2, 148) = 7.13, p = .001 and a Gender × Propulsion interaction, F(1, 74) = 6.47, p = .01. Paired sample t tests were performed within toy type category with Bonferroni correction to correct for the number of tests that are performed (n = 3) to examine these simple effects without increasing the probability of a Type 1 error. Thus, rather than the standard alpha level of .05, a more stringent alpha level of .017 was used to determine significance (i.e., .05/3). For masculine toys, children perceived that boys would like toys with propulsion more than toys without propulsion, t(79) = 2.95, p = .004. For feminine and neutral toys, no significant effect of propulsion was found (p = .50 and p = .024 for feminine and neutral toys, respectively). Subsumed by this interaction is a significant effect of toy type, F(2, 148) = 32.32, p < .001. Contrasts indicated significant differences between each type of toy with masculine toys rated as of highest interest to boys, then neutral toys, and neutral toys were rated of higher interest to boys than feminine toys (all ps < .001). Among girls, but not boys, a significant main effect of propulsion was found, F(1, 37) = 6.23, p = .02, indicating that girls perceived boys to be more interested in toys with propulsion (across all toy gender types) than toys without propulsion.

Rating of Girls’ Interests

Table 2 also shows the girls’ interest ratings as a function of Gender, Propulsion Condition, and Toy Type. The ANOVA revealed significant main effects for Gender, F(1, 75) = 20.65, p < .001, with girls indicating more than did boys that girls would have higher interest in all toys, and Toy Type, F(2, 150) = 35.27, p = .001, where contrasts revealed that children perceived girls to be less interested in masculine toys compared to feminine (p < .001) and neutral toys (p < .001) (ratings for feminine and neutral toys did not differ from one another p = .73).

Discussion

As expected, in Study 1, children were more interested in gender-typed toys than in cross-gender-typed toys. In addition, both boys and girls said they liked neutral toys as much as toys that were gender-typed for their own gender. This finding differs from other studies that offered children gender-typed and neutral toys (Doering et al., 1989; Pasterski et al., 2005), but did look similar to the patterns of children’s play noted in at least one other observational toy choice study (Cherney et al., 2003). It is possible that children’s interest in neutral toys reflects that these toys are culturally stereotyped as appropriate for both genders and thus congruent with their gender (Weisgram, 2016). The study should be replicated with similar and different samples of children to discern whether the increased interest in neutral toys represents a recent shift in children’s interest in neutral toys or whether this finding was unique to this sample. As in previous research using similar procedures (Martin et al., 1995; Weisgram et al., 2014), children predicted other girls and boys to have congruent patterns of gender-typed interest, such that children would choose toys that were in agreement with what is stereotypically appropriate for their own gender.

Contrary to our expectations, propulsion was not a significant factor in whether or not children reported personal interest in toys. Children were interested in toys with propulsion properties as much as they were interested in toys with non-propulsion properties, and no interaction existed between child gender, gender-type of toys, and whether the toy had propulsion movements or not.

Although propulsion was not a factor impacting children’s personal interest in toys, children were aware of the belief that boys like toys that require propulsive movements more than girls. This was specifically true when investigating masculine toys (rather than feminine toys), and girls perceived boys to be more interested in toys with propulsion (across all toy gender types) than toys without propulsion. Girls have been found to have higher rates of stereotype knowledge than boys (Miller, Lurye, Zosuls, & Ruble, 2009; O’Brien et al., 2000), which may explain why girls more than boys reported these stereotypical expectations of other children. In both the current study and a prior study using similar procedures, girls reported higher interest than boys in toys overall (e.g., Weisgram et al., 2014).

Taken together, these findings suggest that gender-typing of toys significantly influences children’s personal interests in toys, but propulsion properties did not have a significant effect. Gender-typing of toys was also a driving force in children’s perceptions of others’ interests, but propulsion only influenced girls’ perceptions of boys’ interests. Demand characteristics and social desirability should be considered when interpreting these findings, because children may be reporting their own interests are more in line with what they believe to be the desired response.

This study allowed us to investigate the combination of a toy’s gender-type and its level of propulsion properties. However, because we used popular toys, this study did not control for children’s previous experiences with the toys or their existing knowledge about them. To remove these sources of potential influence, and further isolate the role that propulsive properties have on children’s interest in toys, in Study 2 we presented children with only gender-neutral toys that were either propulsive or non-propulsive.

Study 2

Method

Procedure and Measures

Participants from Study 1 also took part in Study 2. Children were presented with six gender-neutral toys created for this study. Three of the toys had wheels and three did not. Children had the chance to examine and explore each toy for 30 s and were then asked to indicate whether they were familiar with each toy. None of the children reported that the toys were familiar to them. Then with the toy in front of them, they were asked to indicate their personal interest in the toy, perception of other boys’ interest in the toy, and perception of other girls’ interest in the toy. Children’s responses were obtained using procedures standardized by Weisgram et al. (2014) and Martin et al. (1995), which include providing children with notecards with words and schematics that represent the answer options. Children can reply verbally or through pointing manually.

Materials

Six custom-made unpainted wooden animal-shaped toys resembling animals (elephant, horse, pig, duck, rabbit, and giraffe) were used as gender-neutral novel toys. A second set of identical toys were created with wheels attached to each toy animal, thus adding a propulsive quality to six of the 12 toys. Two sets of toys were created from the 12 toys, each set having three propulsive toys and three non-propulsive toys (see Fig. 2).

Results

For each dependent variable, a 2 (Propulsion: Wheels, No Wheels) × 2 (Gender) mixed effects ANOVA was performed with propulsion as a repeated measures variable.

Personal Interest in Toys

Table 3 shows the mean ratings of personal interest in toys as a function of Gender and Propulsion Condition. The ANOVA revealed a main effect of gender, F(1, 79) = 8.00, p = .006, such that girls were more interested in the presented toys than were boys.

Perception of Others’ Interest

Rating of Boys’ Interests

Table 3 shows the mean ratings of other boys’ interests as a function of Gender and Propulsion Condition. The ANOVA revealed no significant main effects or interactions.

Rating of Girls’ Interests

Table 3 also shows the mean ratings of other girls’ interests as a function Gender and Propulsion Condition. The ANOVA revealed a main effect of gender, F(1, 77) = 15.17, p < .001. Girls perceived other girls to have higher interest in all toy types compared to boys’ perceptions of girls’ interest.

Discussion

Contrary to our expectations, in Study 2 propulsive properties did not impact boys’ or girls’ interest in the toys. Unlike the findings in Study 1, the children did not expect a gender difference in other children’s interest in propulsive versus non-propulsive toys. One explanation for this different pattern of results is that, in Study 1, children only expected a gender difference in interest in propulsion toys when they were considering masculine toys (not when they were considering feminine toys). Thus, this finding emphasizes the importance of the considering the gender-type of the toys when trying to determine whether a gender difference exists in children’s interest in toys with propulsive properties.

It is also possible that the addition of wheels to these toys was not enough to lead the children to identify these toys as propulsive toys. It may be that the toys need to be presented to the children in motion or that there are other operational definitions of propulsive properties that would have resulted in a gender difference.

Both Study 1 and Study 2 asked children to report their perceptions to researchers, which allows for the possibility that children were attempting to answer researchers’ questions in a socially desirable manner, and requires children to introspect and verbally describe their interests and potential behaviors. Particularly given children’s young ages, observing children’s actual play behaviors may provide a more accurate assessment of children’s toy choices.

Study 3

Method

Participants

Participants included 42 preschool children (21 boys, 21 girls) ranging in age from 4 to 6 years (mean age = 4.49, SD = .55). Children were predominately White (78.6%), with representation from Asian American (2.4%), Indian American (7.1%), and multiethnic groups (11.9%). Students were recruited from a preschool setting on the East Coast of the United States. Parent permission was obtained for each child as well as his or her verbal assent to participate. All children asked to participate agreed to be in the study.

Procedure

This was an observational study of children’s free-play behaviors when given a range of toys with which to play. Using procedures modeled after Berenbaum and Hines (1992), we assessed the amount of time children played with a selection of toys from Study 1. Specifically, two toys from each of the following categories were selected: strongly masculine-typed, moderately masculine-typed, gender neutral, moderately feminine-typed, and strongly feminine-typed toys (Blakemore & Centers, 2005). Of the two toys in each category, one of the toys in each category afforded propulsion and one did not. All of the toys were painted white (see Table 1 for information about toys used).

The current study took place in a quiet area of a preschool classroom, offset from the view of the rest of the children in the room. As in Berenbaum and Hines (1992), toys were arranged in a standard order mixed by gender-type and propulsive properties on the floor and were positioned in a circle with an approximate 8-foot diameter. Each child was brought into the play area individually and given the opportunity to play with the toys however he or she desired. In the current study, two research assistants observed the child from a distance. Each of the research assistants had been trained by the principal investigator on the observation process prior to the commencement of the study, and scoring was practiced until inter-rater reliability was confirmed (α = .98). Each child was observed for 12 min, with one research assistant attending to half of the toys, and the other research assistant attending to the other half. A running stopwatch was started when the child began the 12 min of play, and the start time and end time were noted for each toy with which the child played. If a child played with two toys simultaneously, play with both toys was timed. The first 10 min of the play session’s codes was used, unless there was a period of time that was deemed unscorable (e.g., child attempting to interact with a classroom teacher across the room). In these cases, time from the remaining 2 min was used to make up for the unusable portion of the 10 min. Approximately 10% of the children were also observed by the principal investigator to confirm inter-rater reliability was being maintained (α = .96). For the purpose of data analysis, we first computed the proportion of time the child spent playing with each toy. We then collapsed the data across toy type such that time spent playing with the moderately feminine toy and strongly feminine toy were averaged to create a composite score, as was the proportion of time spent playing with the moderately masculine and strongly masculine toys.

Results

A 2 (Gender) × 3 (Toy Type: Masculine, Feminine, Neutral) × 2 (Propulsion: Propulsion, No Propulsion) mixed effects ANOVA was conducted with toy type and propulsion as repeated-measure variables. The amount of time spent playing with each toy type in seconds was the dependent variable.

Figure 3 shows the proportion of time spent playing with toys as a function of Gender, Toy Type, and Propulsion. There was a significant interaction between Toy Type and Propulsion, F(2, 78) = 6.86, p = .002. Paired sample t tests were performed within each toy type to investigate the role of propulsion. A Bonferroni correction, used to correct for the number of tests that are performed (n = 3), was used to examine these simple effects without increasing the probability of a type 1 error. Thus, rather than the standard alpha level of .05, a more stringent alpha level of .017 was used to determine significance (i.e., .05/3). The paired sample t test revealed no significant effect of propulsion on children’s toy play with masculine or feminine toys, t(40) = .43, p = .67, and t(40) = 2.02, p = .06, respectively, but did show an effect of propulsion on children’s toy play with neutral toys, t(41) = −3.15, p = .003. Children were significantly more interested in playing with neutral toys that did not include propulsion than neutral toys that did include propulsion.

Discussion

In Study 3, propulsion did not impact boys’ or girls’ interest in playing with masculine or feminine toys. Unexpectedly, children showed higher interest in playing with neutral non-propulsion toys than neutral toys that required propulsion movements, with no significant gender difference for this preference. These findings did not support the notion that males’ propensity for propulsive movements impacted their toy choice; boys did not spend the majority of their time playing with propulsion toys. The unexpected high interest in the non-propulsive neutral toy (Play-Doh) should be considered as potentially impacting the pattern of findings, and future studies examining different types of non-propulsive neutral toys are needed. Finally, replications of this study with even larger sample sizes would increase the statistical power and verify the pattern of results are consistent and representative.

General Discussion

In the current studies, we investigated gender-typing of toys and toys’ propulsive properties as possible factors impacting children’s toy interests and choices. Guided by previous empirical findings (Davis & Hines, 2015; Weisgram et al., 2014), we expected that children would be more interested in gender-typed toys. Our studies confirmed that toy type was a factor in determining children’s interests, with boys reporting more interest in masculine toys than feminine toys, and girls expressing more interest in feminine toys than masculine toys. However, children also reported that they liked neutral toys the same amount as they liked the toys stereotyped for their own gender group. In Study 3, gender-typed toy preference was less apparent when children were given a variety of toys to play with freely; the Gender × Toy Type interaction was not significant. Patterns in boys’ versus girls’ play preferences showed that boys’ play was more gender-typed than girls’ play.

We expected that boys more than girls would be interested in toys that encouraged propulsive movements. Both non-human primate research and infant studies suggest that males have a propensity for masculine toys, and this propensity has been posited as underlying males’ increased interest in toys or play activities that afford propulsive movements (Alexander & Hines, 2002; Benenson et al., 1997; Hassett et al., 2008). These findings have been interpreted as indications that gender-typed toy preferences reflect hormonally influenced behavioral and cognitive biases (Hassett et al., 2008). In all three studies, propulsion did not drive children’s interests in toys.

It is possible that the particular toys being used to identify interest in propulsive movements played a role in whether or not gender differences are found. In the current study, the majority of the toys considered to have propulsive properties were those that had wheels. This is particularly true for Study 2, where we added wheels to one of two identical sets of novel toys to isolate propulsive properties. Different definitions of propulsive properties may have resulted in different findings. Studying the actual movements children use when playing with toys, such as whether they are pushing, pulling, or throwing a toy, may be a better indicator of interest in propulsive play.

There are other ways that the particular toys used in studying propulsion could impact findings. In research with children and non-human primates (Alexander & Hines, 2002; Benenson et al., 1997; Hassett et al., 2008), males preferred vehicles (which have propulsive properties) over dolls (which have no propulsive properties). It may be that the gender difference in boys’ toy choices occurs more dramatically when forced to choose either a masculine or feminine toy (Bussey & Perry, 1982). The use of novel toys in Study 2 and a variety of toys in Studies 1 and 3 may help reconcile why the gender difference seen in other studies was not evident in the current studies.

In Study 3, it was children’s play patterns with neutral toys, with and without propulsive characteristics, that revealed that propulsive properties of toys did not drive gender differences in children’s toy choices. Boys were not choosing propulsive toys more than non-propulsive toys. In fact, children chose to play with the neutral toy that was non-propulsive more than the propulsive toy. This may be a result of high interest in the particular toy, Play-Doh, or may also suggest that other characteristics of toys (e.g., the ability to be creative, the sensory/tactile nature of a toy) may be more compelling than propulsive properties. These findings also suggest the need to consider toys’ gender-type when studying gender and propulsion, because different patterns of interest in propulsive toys may be found when children are given access to a wider array of toys.

In Study 3, children spent the majority of their free-play time engaging with neutral toys, and although boys played with masculine toys more than feminine toys, girls did not differentiate between toy types and there was much overlap in boys’ and girls’ toy choices. This gendered play pattern is similar to some past (Cherney et al., 2003), and it contradicts others (e.g., Doering et al., 1989; Pasterski et al., 2005). Some study design factors may have influenced flexibility in children’s toy play: all the toys were white (thus eliminating some gender information), children were allowed to play alone uninfluenced by their peers, parents or teachers (Doering et al., 1989; Pasterski et al., 2005), or by a researcher during an interview, and the toys were all made available equally rather than being organized by gender-type. Although these are strengths of the study, it does not reflect the environment in which children make play decisions. Future studies should continue to examine the differences in toy choices in a variety of settings, with various levels of environmental factors that potential shape children’s actual play choices.

It is important to differentiate between children’s perceptions of own and others’ interest in contrast to their own behaviors. While children expected other children’s toy interests to be gender-typed, paralleling their own self-reported toy interests, this pattern was not reflected in children’s actual play behaviors. It may be that children’s self-reported preferences are sensitive to social desirability and demand characteristic bias, more than their play behaviors. Children’s own schemas and superordinate schemas can differ (see Martin & Dinella, 2001), as children’s self-reported interests may represent stereotype knowledge and actual play behaviors may represent their own schemas. The current series of studies should be replicated with larger sample sizes to increase the statistical power, in order to confirm the pattern of findings for children’s interests in propulsion. Also, conducting the study with a wider array of toys in each category would reduce the possibility of some toys being more attractive than other toys for reasons not controlled for in this study. In Study 3, children played with the neutral non-propulsion toy (Play-Doh) a lot, and it would be helpful for additional toys in each category to be added to the study. Further, the samples across the three current studies were all comparable to one another, but it is possible that children from more diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds would have different perspectives on the gender associations of toys, given the known impact of cultural influences such as media, advertising, and life experiences on the creation of own and superordinate schemas (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli, 1980, 1994; Leaper, 2000). Children’s toy interests evolve as children move out of early childhood and into more mature stages; thus, longitudinal and cross-sectional replications may provide helpful insights into children’s toy preferences.

Propulsive properties of toys may not significantly contribute to the gender differences in children’s toy choices. Similarly, research indicates that boy infants visually attend to trucks even though the vehicle was not in motion, and potentially before the infant had the physical development to play with the truck via propulsion (Alexander et al., 2009; Woods et al., 2010). Additionally, gender differences in activity levels do not relate to children’s early toy choices as one would expect if boys preferred propulsion-based play (Alexander & Saenz, 2012). Further, the current results differ from results of non-human primate research, a foundation for the hypotheses that gender-typed toy preferences reflect hormonally influenced behavioral and cognitive biases (Hassett et al., 2008). It is possible that a biological predisposition for certain aspects of toys, such as propulsive properties, do underlie non-human primates’ interests, but that this process differs in children. Systematic investigation similar to that which was conducted in this investigation for children and propulsive properties should be conducted with non-human primates to determine the role of propulsive properties in their toy choices. Should propulsive properties not underlie non-human primates’ toy choices, other toy properties could then be systematic investigated as well.

An expanded examination of the interaction of biological and social factors is needed to understand gender differences in toy choice. The current studies exemplify the value in highly controlled, experimental studies being used to study specific toys and specific properties of toys when attempting to understand gender differences in toy preference, and the benefit of using novel toys to control previous experiences and broader stereotypes that accompany existing toys. Propulsive properties of toys may not significantly contribute to the gender differences in children’s toy choices. A better understanding of the factors that do underlie boys’ and girls’ toy interests is needed so adults can help provide enjoyable and useful learning experiences to children via toys.

References

Alexander, G. M., & Hines, M. (2002). Sex differences in response to children’s toys in nonhuman primates (Cercopithecus aethiops sabaeus). Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 467–479. doi:10.1016/s1090-5138(02)00107-1.

Alexander, G. M., & Saenz, J. (2012). Early androgens, activity levels and toy choices in the second year of life. Hormones and Behavior, 62, 500–504. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.08.008.

Alexander, G. M., Wilcox, T., & Woods, R. (2009). Sex differences in infants’ visual interest in toys. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 427–433. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9430-1.

Benenson, J. F., Liroff, E. R., Pascal, S. J., & Cioppa, G. D. (1997). Propulsion: A behavioural expression of masculinity. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15, 37–50. doi:10.1111/j.2044-835X.1997.tb00723.x.

Benenson, J. F., Tennyson, R., & Wrangham, R. W. (2011). Male more than female infants imitate propulsive motion. Cognition, 121, 262–267. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2011.07.006.

Berenbaum, S. A., & Hines, M. (1992). Early androgens are related to childhood sex-typed toy preferences. Psychological Science, 3, 203–206. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00028.x.

Bigler, R. S., & Liben, L. S. (2007). Developmental intergroup theory: Explaining and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 162–166. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00496.x.

Blakemore, J. E. O., & Centers, R. E. (2005). Characteristics of boys’ and girls’ toys. Sex Roles, 53, 619–633. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-7729-0.

Bussey, K., & Perry, D. G. (1982). Same-sex imitation: The avoidance of cross-sex models or the acceptance of same-sex models? Sex Roles, 8, 773–784. doi:10.1007/BF00287572.

Campenni, C. E. (1999). Gender stereotyping of children’s toys: A comparison of parents and nonparents. Sex Roles, 40, 121–138. doi:10.1023/A:1018886518834.

Carter, D. B., & Levy, G. D. (1988). Cognitive aspects of early sex-role development: The influence of gender schemas on preschoolers’ memories and preferences for sex-typed toys and activities. Child Development, 59, 782–792. doi:10.2307/1130576.

Cherney, I. D., Kelly-Vance, L., Glover, K. G., Ruane, A., & Ryalls, B. O. (2003). The effects of stereotyped toys and gender on play assessment in children aged 18–47 months. Educational Psychology, 23, 95–106. doi:10.1080/01443410303222.

Cherney, I. D., & London, K. (2006). Gender-linked differences in the toys, television shows, computer games, and outdoor activities of 5- to 13-year-old children. Sex Roles, 54, 717–729. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9037-8.

Davis, J., & Hines, M. (2015, March). Gender differences in children’s play: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Paper presented at the biennial conference for the Society for Research in Child Development, Philadelphia, PA.

De Lisi, R., & Wolford, J. (2002). Improving children’s mental rotation accuracy with computer game playing. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 163, 272–282. doi:10.1080/00221320209598683.

Doering, R. W., Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J., & MacIntyre, R. B. (1989). Effects of neutral toys on sex-typed play in children with gender identity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 17, 563–574. doi:10.1007/BF00916514.

Eaton, W. O., Von Bargen, D., & Keats, J. G. (1981). Gender understanding and dimensions of preschooler toy choice: Sex stereotype versus activity level. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 13, 203–209. doi:10.1037/h0081181.

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1980). The “mainstreaming” of America: Violence profile no. 11. Journal of Communication, 30, 10–29. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01987.x.

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1994). Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 17–42). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hassett, J. M., Siebert, E. R., & Wallen, K. (2008). Sex differences in rhesus monkey toy preferences parallel those of children. Hormones and Behavior, 54, 359–364. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.03.008.

Hei Li, R. Y., & Wong, W. I. (2016). Gender-typed play and social abilities in boys and girls: Are they related? Sex Roles, 74, 399–410. doi:10.1007/s11199-016-0580-7.

Idle, T., Wood, E., & Desmarais, S. (1993). Gender role socialization in toy play situations: Mothers and fathers with their sons and daughters. Gender Roles, 28, 679–691. doi:10.1007/bf00289987.

Jadva, V., Hines, M., & Golombok, S. (2010). Infants’ preferences for toys, colors, and shapes: Sex differences and similarities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 1261–1273. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9618-z.

Leaper, C. (2000). The social construction and socialization of gender. In P. H. Miller & E. K. Scholnick (Eds.), Towards a feminist developmental psychology (pp. 127–152). New York: Routledge Press. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.34.

Leaper, C. (2002). Parenting boys and girls. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting (Vol. 1, pp. 189–225). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Leaper, C., & Friedman, C. K. (2007). The socialization of gender. In J. E. Grusec & P. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 561–587). New York: Guilford.

Levine, S. C., Ratliff, K. R., Huttenlocher, J., & Cannon, J. (2012). Early puzzle play: A predictor of preschoolers’ spatial transformation skill. Developmental Psychology, 48, 530–542. doi:10.1037/a0025913.

Liben, L. S., & Bigler, R. S. (2002). The developmental course of gender differentiation: Conceptualizing, measuring, and evaluating constructs and pathways. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 67, i–viii, 1–147. doi:10.1111/1540-5834.t01-1-00187.

Lindsey, E. W., & Mize, J. (2001). Contextual differences in parent–child play: Implications for children’s gender role development. Sex Roles, 44, 155–176. doi:10.1023/A:1010950919451.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Martin, C. L., & Dinella, L. M. (2001). Gender related development. In N. Smelser & P. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences. New York: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b0-08-043076-7/01684-3.

Martin, C. L., Eisenbud, L., & Rose, H. A. (1995). Children’s gender-based reasoning about toys. Child Development, 66, 1453–1471. doi:10.2307/1131657.

Martin, C. L., Fabes, R. A., & Hanish, L. D. (2014). Gendered-peer relationships in educational contexts. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 47, 151–187. doi:10.1016/bs.acdb.2014.04.002.

Martin, C. L., & Halverson, C. F. (1981). A schematic processing model of sex typing and stereotyping in children. Child Development, 52, 1119–1134. doi:10.2307/1129498.

Martin, C. L., Kornienko, O., Schaefer, D. R., Hanish, L. D., Fabes, R. A., & Goble, P. (2013). The role of sex of peers and gender-typed activities in young children’s peer affiliative networks: A longitudinal analysis of selection and influence. Child Development, 84, 921–937. doi:10.1111/cdev.12032.

Miller, C. L. (1987). Qualitative differences among gender-stereotyped toys: Implications for cognitive and social development in girls and boys. Sex Roles, 16, 473–487. doi:10.1007/BF00292482.

Miller, C. F., Lurye, L. E., Zosuls, K. M., & Ruble, D. N. (2009). Accessibility of gender stereotype domains: Developmental and gender differences in children. Sex Roles, 60, 870–881. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9584-x.

O’Brien, M. H., Peyton, V., Mistry, R., Hruda, L., Jacobs, A., Caldera, Y., … Roy, C. (2000). Gender-role cognition in three-year-old boys and girls. Sex Roles, 42, 1007–1025. doi:10.1023/a:1007036600980.

Pasterski, V. L., Geffner, M. E., Brain, C., Hindmarsh, P. C., Brook, C., & Hines, M. (2005). Prenatal hormones and postnatal socialization by parents as determinants of male-typical toy play in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Child Development, 76, 264–278. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00843.x.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Smith, P. K. (1998). Physical activity play: The nature and function of a neglected aspect of play. Child Development, 69, 577–598. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.00577.x.

Ruble, D. N., Martin, C. L., & Berenbaum, S. A. (2006). Gender development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 858–932). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Servin, A., Bohlin, G., & Berlin, L. (1999). Sex differences in 1-, 3-, and 5-year-olds’ toy-choice in a structured play-session. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40, 43–48. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00096.

Servin, A., Nordenström, A., Larsson, A., & Bohlin, G. (2003). Prenatal androgens and gender-typed behavior: A study of girls with mild and severe forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Developmental Psychology, 39, 440–450. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.440.

Sherman, A. M., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2014). “Boys can be anything”: Effect of Barbie play on girls’ career cognitions. Sex Roles, 70, 195–208. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0347-y.

Sutfin, E. L., Fulcher, M., Bowles, R. P., & Patterson, C. J. (2008). How lesbian and heterosexual parents convey attitudes about gender to their children: The role of gendered environments. Sex Roles, 58, 501–513. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9368-0.

Sweet, E. V. (2013, August). Same as it ever was? Gender and children’s toys over the 20th century. Presented at the American Sociological Association meeting, New York, NY.

Weisgram, E. S. (2016). The cognitive construction of gender stereotypes: Evidence for the dual pathways model of gender differentiation. Sex Roles, 75, 301–313. doi:10.1007/s11199-016-0624-z.

Weisgram, E. S., Fulcher, M., & Dinella, L. M. (2014). Pink gives girls permission: Exploring the roles of explicit gender labels and gender-typed colors on preschool children’s toy preferences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35, 401–409. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2014.06.004.

Wolter, I., Glüer, M., & Hannover, B. (2014). Gender-typicality of activity offerings and child–teacher relationship closeness in German “kindergarten”: Influences on the development of spelling competence as an indicator of early basic literacy in boys and girls. Learning and Individual Differences, 31, 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2013.12.008.

Wong, W. I., & Hines, M. (2014). Effects of gender color-coding on toddlers’ gender-typical toy play. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1233–1242. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0400-5.

Wong, W. I., Pasterski, V., Hindmarsh, P. C., Geffner, M. E., & Hines, M. (2013). Are there parental socialization effects on the sex-typed behavior of individuals with congenital adrenal hyperplasia? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 381–391. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9997-4.

Woods, R. J., Wilcox, T., Armstrong, J., & Alexander, G. (2010). Infants’ representation of three-dimensional occluded objects. Infant Behavior & Development, 33, 663–671. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.09.002.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the children who participated in the studies for their time and attention. We also thank the child care staff and teachers for always supporting the effort to understand children’s lives via scientific investigation. The authors also acknowledge the skilled efforts of the following research assistants: Morgan Lalevee, Jordan Levinson, Courtney Medina, Jennifer Pacheco, Lindsey Pieschl, and Deanna Williams, and Maryam Srouji. Lisa M. Dinella would also like to thank Elizabeth Beldowicz for her contribution to this scientific investigation. She attended research team meetings, even when she had the flu. Elizabeth helped remind the research team what it is like to be a child and the importance of meeting kids’ needs during the research process. The team is grateful for Ellie’s assistance and flexibility.

Funding

This study was partially funded by an internal Grant in Aid of Creativity awarded to the first author by Monmouth University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Lisa M. Dinella, Erica S. Weisgram, and Megan Fulcher declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dinella, L.M., Weisgram, E.S. & Fulcher, M. Children’s Gender-Typed Toy Interests: Does Propulsion Matter?. Arch Sex Behav 46, 1295–1305 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0901-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0901-5