Abstract

We examined the interplay between husbands’ and wives’ positive and negative nonsexual interpersonal behaviors, frequency of sexual intercourse, sexual satisfaction, and feelings of marital satisfaction. To do this, we conducted an in-depth face-to-face interview and completed a series of telephone diaries with 105 couples during their second, third, and fourteenth years of marriage. Consistent with the argument that women’s sexual response is tied to intimacy (Basson, 2000), multilevel analyses revealed that husbands’ positive interpersonal behaviors directed toward their wives—but not wives’ positivity nor spouses’ negative behaviors (regardless of gender)—predicted the frequency with which couples engaged in intercourse. The frequency of sexual intercourse and interpersonal negativity predicted both husbands’ and wives’ sexual satisfaction; wives’ positive behaviors were also tied to husbands’ sexual satisfaction. When spouses’ interpersonal behaviors, frequency of sexual intercourse, and sexual satisfaction were considered in tandem, all but the frequency of sexual intercourse were associated with marital satisfaction. When it comes to feelings of marital satisfaction, therefore, a satisfying sex life and a warm interpersonal climate appear to matter more than does a greater frequency of sexual intercourse. Collectively, these findings shed much-needed light on the interplay between the nonsexual interpersonal climate of marriage and spouses’ sexual relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In his 1954 address to the American Psychiatric Association, Kinsey argued that “when there are adequate sexual relationships, marriages become emotionally richer; when sexual relationships do not involve sufficient emotional interchange, then marriages are threatened” (as quoted in Gathorne-Hardy, 2000, p. 70). This idea that the emotional tenor of marriage and attributes of spouses’ sexual relationships are inextricably linked has been embraced by social scientists, clinical practitioners, and the general public alike. The frequency with which couples engage in sexual intercourse and the extent to which sex is gratifying are believed to reflect the depth of a couple’s entire physical and emotional bond (Schnarch, 1997) and are viewed as a barometer of marital health (Schwartz & Rutter, 1998).

Despite these widespread beliefs, the link between sexual relationships and the broader, nonsexual interpersonal climate of marriage has received little empirical attention. As a result, “we still have only a limited view of how sexuality is integrated into the normal flow of married life” (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000, p. 232, emphasis added). Using data gathered from 105 couples whose marriages were followed for more than 13 years and who provided extensive information on both the sexual and nonsexual aspects of their relationships, the present study is among the first to examine spouses’ positive and negative nonsexual interpersonal behaviors (referred to interchangeably as “the interpersonal climate of marriage”) in connection with both the frequency of sexual intercourse (or, more simply, “sexual frequency”) and sexual satisfaction. Specifically, we sought to answer three questions: (1) Does the frequency with which couples have sex depend, in part, on the broader interpersonal climate of their marriages? (2) Is sex more gratifying in marriages characterized by favorable interpersonal climates and more frequent sex? and (3) Do sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction predict marital satisfaction over and above spouses’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors?

The Interpersonal Climate of Marriage and the Sexual Relationship

Sexual Frequency

In their classic survey involving approximately 3600 married couples, Blumstein and Schwartz (1983) were among the first to connect sexual frequency to the broader interpersonal climate of marriage. They concluded that spouses who showed more spontaneous affection were more eager to have sex, whereas couples who reported more nonsexual conflict found their sex lives to be wanting. Although this work has contributed to the widespread belief that highly affectionate spouses have more sex and those who criticize or otherwise behave antagonistically toward one another have less sex, few empirical studies have examined how partners’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors are tied to the frequency of sexual intercourse.

After repeated calls to action from both scholars and clinicians alike (e.g., Aubin & Heiman, 2004; Diamond & Huebner, 2012), however, researchers have begun considering partners’ sexual relationship in connection with broader relationship dynamics. In a recent study utilizing a daily diary framework to examine the association between romantic partners’ positivity and sexual frequency, H. Rubin and Campbell (2012) found that, on days when either partner reported increased intimacy—as characterized by self-disclosure, feelings of closeness, and affection outside of intercourse—couples were more likely to report that they also engaged in sex. Despite the strength of this methodological approach, these findings cast only a sliver of light on how sexual frequency is connected to partners’ positive behaviors in general, as the researchers limited their investigation to couple members’ daily levels of intimacy and did not assess a broader class of positive behaviors.

Just as partners who characterize themselves as displaying more affection indicate that they enjoy more active sex lives, spouses who engage in more antagonistic behaviors may find themselves having less sex. However, only a few studies link interpersonal negativity to a reduced incidence of sex, and most work centers on interpersonal conflict as opposed to antagonism more generally (which could take place outside of a conflict episode). Although some research indicates that couples who report a greater number of arguments or problems in their relationships do not necessarily have less sex (e.g., Russell & McNulty, 2011)—and oftentimes have more sex (e.g., Hetherington, 2003)—most clinicians and scholars agree that marital conflict undermines sexual relationships (see Metz & Epstein, 2002). For instance, Rao and DeMaris (1995) found that men (but not women) who perceived their relationships as troubled or plagued by open disagreement reported having less sex with their partners. However, because the researchers required the participants in this study to recall how often they had disagreements with their partner during the prior year as well as the number of times they had sex with their partner during the previous month, these findings may paint a somewhat biased picture of the association between interpersonal negativity and the frequency of sex. By asking individuals to report on their partner’s positive and negative behaviors during the prior 24-h period, we were able to sidestep the issues of poor recall and state-congruent memory that often plague retrospective methods and more accurately capture the frequency with which spouses engage in specific interpersonal and sexual behaviors (see Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003).

In a unique investigation examining whether partners’ day-to-day positive and negative interpersonal exchanges, considered in tandem, are connected to sexual behavior, Ridley, Cate, Collins, Reesing, and Lucero (2008) found that partners who felt more positively toward one another reported engaging in more sexual behaviors. Unexpectedly, those who reported more negative feelings about their partners also reported participating in more sexual activities. However, as these results reflect how the sexual relationship is connected to partners’ positive and negative feelings, it is unclear if such feelings translate into displays of affection or antagonism, respectively. Because sexual activities occur within the context of relationships in which both partners’ overt behaviors are presumed to influence one another (e.g., Sprecher, 1998), it is important to determine whether these findings on partners’ intrapsychic experiences extend to their interpersonal behaviors.

Sexual Satisfaction

Early studies of marital sexuality often treated sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction as the same phenomenon, suggesting that individuals who had more sex must be more satisfied with their sex lives. In line with this perspective, the amount of sex individuals report having with their partners is consistently tied to how positively individuals view their sex lives (e.g., Edwards & Booth, 1976; Henderson-King & Veroff, 1994; Yucel & Gassanov, 2010). However, researchers now generally agree that the sheer number of times couples have sex is not as strongly tied to the quality of their sexual relationships as initially believed (Christopher & Kisler, 2004).

In particular, the broader interpersonal climate of marriage may also contribute to spouses’ sexual satisfaction. Just as partners’ displays of affection and antagonism may contribute to how often couples have sex, these behaviors may also color whether or not partners perceive their sex lives as satisfying. Clinicians have long suspected that partners who express less affection toward one another become emotionally distant and, in turn, less satisfied with their sex lives (e.g., Leiblum, 1998; Tiefer, 1991; see also Aubin & Heiman, 2004). A survey of Chinese spouses lends support to this notion: Even after accounting for individuals’ reported frequency of sexual activities, spouses who indicated they hugged, kissed, and cuddled with their partners more often reported greater sexual satisfaction (Renaud, Byers, & Pan, 1997).

Whereas spouses who report showing a lot of affection for their partners also report greater sexual satisfaction, those who engage in more antagonistic behaviors generally find their sexual relationships to be less satisfying (Haning et al., 2007). However, much of the empirical work on the connection between interpersonal negativity and the quality of sexual relationships has been limited to comparisons between sexually dysfunctional couples and non-clinical control groups (see Metz & Epstein, 2002), and thus the impact that negative exchanges may have on the sexual relationships of couples who are not suffering from sexual or marital distress has been largely overlooked. In a notable exception, Ridley et al. (2006) found that, on days when husbands and wives reported feeling more angry or irritated with their partners, their spouses experienced dampened feelings of lust. Because negative affect can translate into negative interpersonal behaviors (Caughlin, Huston, & Houts, 2000), and feelings of lust (or sexual desire) have been linked to greater sexual satisfaction (Hurlbert, Apt, & Rabehl, 1993), these findings support the notion that interpersonal negativity can erode sexual satisfaction.

In a rare study considering how the sexual relationship—in combination with the interpersonal climate—is tied to sexual satisfaction, Haning et al. (2007) asked a sample of sexually active individuals to indicate their feelings of intimacy and the level of conflict in their relationships, as well as their likelihood of orgasm and the extent to which they were satisfied with their sexual relationships. Individuals who reported greater intimacy and a greater likelihood of orgasm felt more sexually satisfied on average; additionally, for women—but not for men—conflict was inversely associated with feelings of sexual satisfaction. Although this study examined positively and negatively valenced partnership issues alongside features of the participants’ sexual relationships, it is unclear whether this pattern of results extends to individuals’ actual day-to-day behaviors, as the measures for intimacy and conflict intermixed attitudinal and behavioral items, and the researchers examined the likelihood of orgasm instead of sexual frequency. What’s more, because participation was open to all sexually active adults, these findings may not reflect the ways in which the sexual and nonsexual aspects of partners’ relationships are connected to sexual satisfaction among those in established relationships. The present investigation builds on the research described above and examines whether spouses’ sexual frequency, together with their positive and negative interpersonal behaviors, uniquely contributes to husbands’ and wives’ feelings of sexual satisfaction.

Marital Satisfaction

The quantity and quality of sex reported by husbands and wives, as well as the positive and negative behaviors that define the broader interpersonal climate of their relationships, has been consistently linked to spouses’ overall evaluations of their marriages. Indeed, couples who have more sex feel more satisfied with their relationships in general (e.g., Call, Sprecher, & Schwartz, 1995), as do husbands and wives who find their sex lives to be particularly fulfilling (e.g., Yeh, Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006). Yet, until recently, researchers paid little attention to the ways in which sexual activity and sexual satisfaction translate into marital satisfaction. In a notable exception, Meltzer and McNulty (2010) found that, although self-reported sexual frequency over a prior 30-day period was directly tied to marital satisfaction, spouses’ reports of sexual satisfaction fully mediated this association. However, because researchers have yet to account for spouses’ nonsexual interpersonal dynamics when examining the impact of sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction on marital satisfaction, it remains unclear whether any associations between the sexual relationship and marital satisfaction are superseded by the positive and negative behaviors that partners engage in on a day-to-day basis.

Compared to the sexual aspects of couples’ relationships, the ways in which husbands and wives behave toward one another, apart from the sex act itself, have a greater influence on spouses’ overall assessments of marital satisfaction (Hassebrauck & Fehr, 2002; Huston & Vangelisti, 1991). Both affection and antagonism have been independently linked to partners’ feelings of marital satisfaction, such that spouses who receive more affection from their partners report greater satisfaction with their relationships (e.g., Horan & Booth-Butterfield, 2010; Miller, Caughlin, & Huston, 2003), and those who are the target of their partner’s antagonistic behaviors generally report lower levels of marital satisfaction (e.g., Caughlin et al., 2000; Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Although few studies have concurrently examined spouses’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors outside of a conflict interaction task, those that have typically find that both types of interpersonal behaviors uniquely contribute to husbands’ and wives’ feelings of marital satisfaction (e.g., Caughlin & Huston, 2002; Feeney, 2002).

Thus, although sexual satisfaction, affection, and antagonism have been independently tied to husbands’ and wives’ feelings of marital satisfaction, and recent work suggests that the link between sexual frequency and marital satisfaction is mediated by sexual satisfaction, it remains to be seen whether these associations will persist when considered simultaneously.

Overview of the Current Study

To accomplish our objectives, we asked husbands and wives to report on the quantity and quality of sex they were having with their partners, their day-to-day positive and negative interpersonal behaviors, and their feelings of marital satisfaction at three points in time over the course of 13 years of marriage.

The first set of analyses tested whether the interpersonal climate of marriage—characterized by partners’ positive and negative behaviors—is tied to how often couples had sex. Specifically, we hypothesized that the interpersonal climate of marriage will predict how often couples have sex, such that when positive and negative interpersonal behaviors are considered simultaneously (1) the more often spouses behave positively toward one another, the more often the couple will have sex, and (2) the more negatively spouses behave toward one another, the less often the couple will have sex.

The second set of analyses examined whether sexual frequency, when considered in tandem with the interpersonal climate of marriage, is associated with spouses’ sexual satisfaction. We hypothesized that sexual frequency and the interpersonal climate of marriages will be associated with husbands’ and wives’ sexual satisfaction, such that (1) partners who have more sex will report greater sexual satisfaction, after accounting for spouses’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors. In addition, after controlling for sexual frequency, we expected that (2) positive behaviors will be tied to increased sexual satisfaction, whereas (3) negative behaviors will be inversely associated with sexual satisfaction.

In our final set of analyses, we sought to determine the ways in which sex matters in marriage by simultaneously examining sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and spouses’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors in relation to their feelings of marital satisfaction. More precisely, we hypothesized whether (1) after accounting for spouses’ positive and negative interpersonal exchanges, the association between sexual frequency and marital satisfaction will be mediated by sexual satisfaction, and (2) after controlling for couples’ sexual frequency and spouses’ sexual satisfaction, husbands’ and wives’ displays of positivity will be positively tied to their reported marital satisfaction, while partners’ negative behaviors will be inversely associated with feelings of marital satisfaction.

Through these three sets of analyses, we can determine whether having an active sex life, a satisfying sex life, or both is independently associated with husbands’ and wives’ reports of marital satisfaction. If sexual frequency or sexual satisfaction fails to be associated with spouses’ marital satisfaction after their positive and negative interpersonal behaviors are taken into account, then such findings would indicate that sex matters less in marriage than previously suggested.

Method

Participants

Couples were recruited using marriage license records from four counties in central Pennsylvania. In order to be eligible to participate, couples had to be in their first marriages, speak English fluently, and have no plans to move from the area within 2 years. Of the 400 couples that were solicited to participate in the current study, 42 % (168 couples) agreed. According to information reported in the marriage license records, the couples that chose to participate did not significantly differ from those who declined in terms of their educational level, age, or fathers’ occupational status (see Robins, 1985). The majority of participants married at an early age (average age = 21.09 years for wives, 23.60 years for husbands), were White (98.81 %), had a high school education or less (58.04 %), and came from working-class backgrounds (61.90 %).

Procedure

The data used in the current study were collected as part of a larger project involving four phases of data collection, beginning when the couples were newlyweds.Footnote 1 However, only the final three time periods (Phases 2–4) were included in the current study, as spouses’ sexual satisfaction was not assessed during Phase 1 of the study (given the central role that sexual satisfaction plays in the current study, we elected to exclude the first phase of data). Phase 2 took place in 1982, after the couples had been married for, on average, 14 months, and Phase 3 took place in 1983, 2 months after couples’ second anniversaries. The final phase of data collection occurred over a decade later (in 1994 and 1995), when the couples had been married between 13 and 14 years. At the completion of the study, we were able to determine the marital status of 164 of the 168 couples: 105 couples remained married, 56 divorced, three were widowed, and four were unable to be located. As the current study captures the associations between spouses’ positive and negative behaviors, sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction over time, only the 105 couples that remained married throughout all phases of data collection were included in the final sample. However, follow-up analyses utilizing the entire sample (i.e., couples who remained continuously married and those who divorced) produced the same basic pattern of results (with the exception of one finding, which is highlighted in the “Results” section).Footnote 2

At each phase, couples took part in an extensive interview designed to paint a comprehensive picture of couples’ day-to-day lives together, as well as capture the quality of their marital and sexual relationships. Each spouse was interviewed independently by same-sex interviewers, and the interview procedure typically lasted for about 90 min. Data collected during these interviews included information about spouses’ feelings of sexual and marital satisfaction, as well as detailed information about their personal and family backgrounds.

In the two- to three-week period following this initial interview, couples participated in a series of telephone diaries designed to obtain information about the day-to-day life of each couple. During each telephone interview, spouses (separately) indicated how often their partner engaged in a variety of positive and negative behaviors—as well as the number of times, if any, they had sex with their partner—during the prior 24-h period, ending at 5:00 p.m. the evening of the call. Participants completed nine telephone interviews during both Phase 2 and Phase 3, and they completed six telephone interviews during Phase 4. Couples were contacted approximately every other day, and the vast majority of calls took place between 5 p.m. and 11 p.m. Spouses who worked evenings or were otherwise occupied at the time of the call were interviewed the following morning; however, regardless of whether both spouses could be interviewed in the evening or not, husbands and wives reported on the same 24-h period. The aggregate of these diary-type interviews made it possible to create portraits of each individual marriage, allowing us to characterize how positively the spouses behaved toward one another, how much antagonism they showed, and how often they had sex. For more information regarding the diary procedure, see Huston (2009) and Huston, Robins, Atkinson, and McHale (1987).

Measures

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all study variables are shown in Table 1.

Positive and Negative Behaviors

To assess spouses’ positive and negative behaviors, husbands and wives were asked to indicate how often their partner engaged in an array of positive and negative behaviors during the 24-h period ending at 5 p.m. the day of the call. Spouses reported the number of times their partner enacted seven positive or prosocial behaviors (such as saying I love you, engaging in physical affection outside of intercourse, and expressing approval or offering compliments), as well as seven negative or antagonistic behaviors (such as dominating conversations, showing anger or impatience, and purposefully doing something to annoy one’s partner). Spouses’ positive and negative behaviors were aggregated across days to create two indices, one for each class of behaviors (see Huston & Vangelisti, 1991, for a complete list of the positive and negative behaviors).

Sexual Frequency

During each telephone diary, husbands and wives reported whether they had sexual intercourse during the prior 24-h period and, if so, the number of times. As with the positivity and negativity items, husbands’ and wives’ reported sexual frequency was aggregated across days. Although both spouses reported the number of times that they had sex with their partner, because their reports were highly correlated (the average correlation was .88; all ps < .001), and due to the dyadic nature of the behavior, husbands’ and wives’ reports of sexual frequency were averaged together within each phase. In Phase 2, couples’ sexual frequency ranged from 0 to 12; in Phase 3, the range was 0–15 and in Phase 4 the range was 0–10.67. Couples had sex an average of 0.40 times per day during Phase 2 (SD = .31), 0.34 times per day during Phase 3 (SD = .31), and 0.27 times per day during Phase 4 (SD = .29). The frequency of sexual intercourse ranged from 0 to 10 times per day during Phase 2, 0 to 4 times per day during Phase 3, and 0 to 3 times per day during Phase 4.

Sexual Satisfaction

Husbands and wives reported on their feelings of sexual satisfaction during the initial interviews using a global item, which asked about their personal sexual satisfaction over the last 2 months. Specifically, spouses were asked, “How satisfied or dissatisfied have you been with your sexual relationship?” Answers were anchored on a nine-item scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 9 (very satisfied).

Marital Satisfaction

Spouses’ overall satisfaction with their marriages was measured using the Marital Opinion Questionnaire, which was adapted from a life satisfaction measure (A. Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976). The measure had two parts. In the first part, participants were asked to characterize their marriages on a 7-point scale using a set of 10 bipolar adjectives (e.g., “Sad v. Happy” and “Brings out the worst in me v. Brings out the best in me”). Factor analyses revealed that eight of these items loaded together on a single factor (see Huston & Vangelisti, 1991; Miller et al., 2003). In the second part of the measure, participants rated their overall satisfaction with their marriages on a scale ranging from 1 (completely dissatisfied) to 7 (completely satisfied). For both of these parts, spouses were asked to base their ratings on the quality of their marriages during the prior 2 months. Following A. Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers (1976), the ratings of the eight semantic differential items were averaged together with spouses’ overall rating of marital satisfaction to produce a single index of marital satisfaction with possible scores ranging from 1 (low) to 7 (high). Alpha coefficients for the semantic differential items were high across all phases, ranging from .88 to .93 for husbands and .91 to .94 for wives, and the correlations between the totals of the semantic differential scores and the global assessment of marital satisfaction ranged from .69 to .78 and .61 to .85 for husbands and wives, respectively (all ps < .001; for more information about the marital satisfaction scale, see Huston & Vangelisti, 1991).

Analytic Strategy

For all analyses, multilevel modeling procedures with SAS Proc Mixed were used. To examine whether spouses’ propensity to behave in a positive or antagonistic manner predicted the frequency of sexual intercourse, multilevel modeling techniques were employed, in which the data were analyzed at the level of the dyad. Because the outcome variable, sexual frequency, was measured at the level of the dyad (i.e., the couple either did or did not have sex a certain number of times), the issue of the non-independence of the residuals between dyad members was irrelevant (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Sexual frequency was modeled as a function of husbands’ and wives’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors; time of the assessment (coded as 0, 1, or 12) was also included in the analysis in order to model the linear slope associated with time across the three phases of the study and to account for issues commonly associated with longitudinal designs, such as autocorrelation (e.g., Lyons & Sayer, 2005).

For the analyses predicting sexual satisfaction and marital satisfaction, multilevel modeling procedures were used to estimate these effects separately for husbands and wives using a single analysis (Kenny et al., 2006; Raudenbush, Brennan, & Barnett, 1995). The models accounted for the fact that our outcome variables were clustered within spouses, who were clustered within couples. Thus, the models consisted of a within-individual (over time) and a between-individual level.

For the within-individual equations, two dichotomous variables were created to distinguish between husbands (husbands = 1, wives = 0) and wives (husbands = 0, wives = 1). All relevant variables were then entered into the model twice: First, they were interacted with the “husband” variable, and then they were interacted with the “wife” variable in order to reveal the unique effects of each variable for both spouses. For our analysis examining sexual satisfaction, these variables included the timing of the assessment, as well as spouses’ affection, antagonism, and frequency of sexual intercourse; our model for marital satisfaction included all of the variables listed above and also spouses’ feelings of sexual satisfaction.

At the between-individual level of the analysis, each of the parameters at the within-individual level was treated as an outcome variable and was determined by its grand mean. In both models, the intercepts and phase effects were allowed to vary randomly for husbands and wives, but the remaining between-individual equations (for husbands’ and wives’ reported sexual frequency, as well as each partner’s positive and negative behaviors) did not include an error term, thus constraining these effects to be constant across couples (L. Campbell, Martin, & Ward, 2008; Kenny et al., 2006). To provide separate (but correlated) estimates of error variances for husbands and wives, we specified that the covariance structure be modeled using heterogeneous compound symmetry.

It is important to point out that the current analyses examined contemporaneous rather than time-lagged associations among our variables of interest, and thus our findings can solely be interpreted as correlational. Because a substantial period of time passed between the first two assessments, and the second and third assessments were separated by more than a decade, it is unlikely that spouses’ positive and negative behaviors that occurred at least a year prior would affect their sexual frequency over and above the concurrent climate. Indeed, even time lags of 1 day are often not significant when there is a firm theoretical reason to suspect otherwise (e.g., Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989). Because the period of time in which husbands’ and wives’ positive and negative behaviors affect the sexual relationship is likely to be less than the length of time that passed between the observations (i.e., potentially less than 1 day versus a minimum of 1 year), we felt it theoretically prudent to examine concurrent rather than time-lagged associations between spouses’ positive and negative behaviors and their sexual relationships (see Finkel, 1995).

Results

Do Positive and Negative Interpersonal Behaviors Predict Sexual Frequency?

The hypothesis that spouses’ positive behaviors would be tied to a greater frequency of sex received only partial support. Specifically, husbands’ positivity—but not wives’—was significantly associated with how often couples reported having sex (see Table 2). However, given the strong correlation between husbands’ and wives’ affectionate behaviors across the three phases of data collection (rs ranged from .58 to .78), it should not be inferred that wives’ positivity was unrelated to spouses’ sexual frequency. Indeed, follow-up analyses revealed that when husbands’ positivity was dropped from the model, wives’ positivity predicted how often couples had sex (b = .006, p = .03). Similarly, when husbands’ and wives’ positivity were averaged together, the aggregated variable was significantly associated with sexual frequency (b = .010, p < .001). Counter to expectations, neither husbands’ nor wives’ negativity was associated with sexual frequency (see Table 2).

Finally, we tested whether spouses’ affection and negativity interacted to predict the frequency of sexual intercourse. To do this, we included in the model all possible two-way interaction terms involving spouses’ interpersonal behaviors (e.g., Husband’s Negativity × Wife’s Positivity; Wife’s Negativity × Wife’s Positivity). Of the four interactions tested, only one was significant. Specifically, husbands’ positivity interacted with wives’ negativity to predict how often couples had sex, such that more affectionate husbands paired with more antagonistic wives reported the highest levels of sexual activity, t(156) = 2.01, p < .05. For the remaining analyses in the current study, we tested additional models that included the full range of possible interaction terms (e.g., Husband’s Positivity × Husband’s Negativity; Husband’s Negativity × Sexual Frequency). Because none of these interactions were significant, for the remaining analyses, we present the results of the models that included only the main effects.

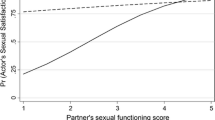

Do Sexual Frequency, Positivity, and Negativity Predict Sexual Satisfaction?

The effects of sexual frequency, as well as partners’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors, on sexual satisfaction are shown in Table 3. As predicted, there was a strong, positive association between sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction for both husbands and wives, even after accounting for partners’ positive and negative behaviors. The link between spouses’ interpersonal behaviors and their levels of sexual satisfaction was also in line with expectations. With respect to positivity, husbands’ expressions of positivity were only marginally associated with wives’ feelings of sexual satisfaction (follow-up analyses utilizing the full sample—i.e., those who remained continuously married and those who divorced—revealed a significant link between husbands’ positive behaviors and wives’ feelings of sexual satisfaction, b = .004, t(220) = 2.17, p = .03), but wives’ displays of positivity were strongly tied to husbands’ sexual satisfaction. Partners’ negative behaviors, on the other hand, were inversely connected to feelings of sexual satisfaction for both spouses, such that husbands and wives felt less satisfied sexually when their partners behaved in a negative or antagonistic manner.

Do Sexual Frequency, Sexual Satisfaction, and Partners’ Positive and Negative Interpersonal Behaviors Predict Marital Satisfaction?

Table 4 shows the results for the multilevel model predicting marital satisfaction. Counter to expectations, sexual frequency was not associated with marital satisfaction for either husbands or wives once spouses’ sexual satisfaction and the interpersonal climate of marriage were taken into account; sexual satisfaction, on the other hand, was significantly and positively tied to feelings of marital satisfaction for both husbands and wives, and this effect persisted above and beyond the influence of sexual frequency and the interpersonal climate of marriage.

Because sexual frequency is generally tied to feelings of marital satisfaction for both husbands and wives (e.g., Call et al., 1995), we were curious if the inclusion of sexual satisfaction in the model obscured this expected association. Dropping spouses’ reports of sexual satisfaction did, in fact, result in sexual frequency being positively tied to marital satisfaction for both husbands and wives (ps = .04). Formal tests for mediation indicated that spouses’ satisfaction with their sexual relationship fully mediated the association between sexual frequency and marital satisfaction for both spouses (husbands’ Sobel: t = 3.81, p < .001; wives’ Sobel: t = 2.27, p < .01).Footnote 3

With respect to spouses’ positive and negative interpersonal behaviors, we found that husbands’ and wives’ positive and negative behaviors were tied to their partners’ feelings of marital satisfaction, after accounting for sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction. Consistent with expectations, spouses who reported that their partners engaged in more positive behaviors also reported higher levels of marital satisfaction, and spouses who perceived their partners as being particularly negative reported also lower levels of marital satisfaction.

Discussion

Whereas a large number of studies have established that sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and spouses’ positive and negative behaviors independently contribute to marital satisfaction (e.g., Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Byers, 2005; Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Huston & Vangelisti, 1991; Sprecher, 2002), the current investigation was among the first to consider these factors in tandem. Using data collected at three time points over 13 years of marriage, we first demonstrated that husbands’ positive behaviors were a key predictor of how often couples had sex. The frequency of sexual intercourse, in turn, was tied to spouses’ feelings of sexual satisfaction (as were features of the interpersonal climate of marriage). With the exception of sexual frequency, all of these factors were significantly associated with spouses’ feelings of marital satisfaction. Although it is popularly believed that more sex yields more satisfying marriages, our findings suggest that the quality of sex matters more than the quantity, at least once the broader interpersonal climate of the relationship is taken into account.

The Interpersonal Climate of Marriage and Sexual Frequency

Our first set of analyses revealed that the extent to which husbands—but not wives—behaved positively toward their partners predicted how often couples had sexual intercourse. It is possible that sex and affection outside of intercourse are more closely connected in the minds of men than women, as husbands (but not wives) who are more in love both engage in a greater number of affectionate behaviors and initiate sex more often (Schoenfeld, Bredow, & Huston, 2012). Alternatively, men may believe their partners require a warm or affectionate marital climate before agreeing to have sex. Indeed, qualitative work suggests that, for women, sex is integrally tied to the broader dynamics of their relationships (e.g., Elliot & Umberson, 2008; Sims & Meana, 2010). By displaying affection, or helping out around the house, men may effectively pique their partners’ sexual interest. Thus, husbands may engage in more affectionate or positive behaviors to “earn” sexual access to their wives (see Baumeister & Vohs, 2004).

The finding seems fully compatible with the circular model of human sexual response (Basson, 2000, 2001; Brotto, 2010; Hayes, 2011), which was developed mostly to account for the frequently observed lack of “spontaneous” sexual desire observed among women in long-term relationships. According to Basson (2000, 2001), female desire usually follows rather than precedes sexual arousal, which is triggered by external erotic stimuli. Within this model of female sexual response, the importance of partners’ positive behaviors can hardly be overstated—as such behaviors often trigger (either directly or indirectly) a transition from sexual “neutrality” to sexual arousal (Basson, 2000, 2001; Carvalheira, Brotto, & Leal, 2010).

Contrary to what was expected, negativity was unrelated to how often couples had sex. Perhaps couples react to negativity differently, with some couples abstaining from sex when there is a lot of hostility or conflict in their marriage (e.g., B. McCarthy, 2003; Metz & Epstein, 2002), and other couples using sex as a way to apologize or make a repair after a conflict episode (Davis, Shaver, & Vernon, 2004; Impett, Strachman, Finkel, & Gable, 2008). It is also worth noting that the most sexually active couples were the ones in which the husband displayed more positivity despite the wife engaging in more antagonistic behaviors. Men (but not women) report feeling more attracted to their romantic partners in the face of dyadic conflict (Birnbaum, Mikulincer, & Austerlitz, 2013), and such attraction may translate into more attempts at initiating sex and, in turn, increased sexual activity. Because husbands tend to show affection and initiate sex more often when they are more in love, and wives are more likely to behave antagonistically and initiate sex when they are less in love (Schoenfeld et al., 2012), this pattern may typify couples in which the husbands are more emotionally invested in the relationship than the wives.

Predicting Sexual Satisfaction

Turning to sexual satisfaction, we found that, consistent with prior research (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Peplau, Fingerhut, & Beals, 2004), the more often couples had sex, the more satisfied husbands and wives were with their sexual relationships. In addition to sexual frequency, the interpersonal climate of marriage was also tied to spouses’ assessments of their sexual relationships. As expected, the more negatively spouses behaved toward one another, the less satisfied husbands and wives were with their sexual relationships. Negativity and conflict have consistently been linked to dampened sexual satisfaction (e.g., Haning et al., 2007; Metz & Epstein, 2002). For instance, Theiss and Nagy (2010) found that individuals who perceived their partners as interfering with or undermining their personal objectives—perceptions which, in turn, are tied to feeling as though one’s relationship is tumultuous or unstable (Knobloch, 2007)—reported lower levels of sexual satisfaction.

Interestingly, men who were married to particularly affectionate women reported significantly greater satisfaction with their sex lives, but wives’ sexual satisfaction was only marginally related to husbands’ displays of positivity. Social scientists have traditionally believed that women—more so than men—enjoy sex more when it occurs within the context of an intimate and affectionate relationship (e.g., DeLamater, 1987), but perhaps women are better able to separate affection occurring outside of sex from their assessment of the sexual experience itself than previously suggested. Although women may require a certain degree of affection from their partners to have sex in the first place (as discussed above), such affection may not necessarily contribute to the pleasure or sense of intimacy they derive from intercourse. Orgasm is less certain for women than for men (e.g., Laumann et al., 1994), and thus women’s sexual satisfaction may depend more on whether their sexual needs are met than on whether their affectional needs are met. Because most men experience orgasm during sex (e.g., Richters, de Visser, Rissel, & Smith, 2006), their partners’ tendency to behave positively in general may add to their sense of sexual intimacy. If men do not clearly distinguish between affection and sex, as previously suggested, then the affection that takes place outside the bedroom may color their evaluation of their overall sex life. This is not to suggest that sexual satisfaction depends exclusively (or even primarily) on the achievement of an orgasm; rather, we use this research to illustrate that positive behaviors and sex may be more connected in the minds of men than women.

Correlates of Marital Satisfaction

As anticipated, spouses who perceived their partners as particularly affectionate reported higher levels of marital satisfaction; conversely, those married to individuals who were more antagonistic reported being less satisfied with their marriages. Although these findings are not new—indeed, both affection (see Caughlin & Huston, 2010; Floyd et al., 2005; Horan & Booth-Butterfield, 2010; Huston & Vangelisti, 1991) and antagonism (see Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000; Huston & Vangelisti, 1991; Johnson et al., 2005) have been consistently linked to marital quality—it is interesting to note that these associations persist even after accounting for spouses’ sexual satisfaction and reported frequency of intercourse.

Of greater interest were the associations between sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and overall marital satisfaction. When sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and the interpersonal climate of marriage are considered in tandem, the frequency with which partners have sex is unrelated to how satisfied they are with their marriages in general. Sexual satisfaction, on the other hand, continued to be tied to spouses’ evaluations of their marriages, such that those who reported greater satisfaction with their sex lives tended to view their marriages in a more positive light. Thus, it is not how often couples have sex, but rather the quality of the sexual relationship that seems to matter. These results are consistent with work by McNulty, Wenner, and Fisher (2014), who documented that, controlling for spouses’ sexual satisfaction, sexual frequency was unrelated to their later reports of marital satisfaction. Also in line with recent research (Meltzer & McNulty, 2010), sexual satisfaction fully accounted for the connection between spouses’ frequency of intercourse and their reported levels of marital satisfaction, suggesting that having an active sex life increased spouses’ sexual satisfaction, which, in turn, improved the overall quality of marriage.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the study of sexuality in intimate relationships has a long history—indeed, the earliest studies of the interconnections between sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and marital quality date back to the 1930s (Terman, 1938)—the scope of research has remained limited. In their comprehensive review detailing the state of research on sexuality, DeLamater and Hyde (2004) called for an expanded definition of sexuality, one that “directly implicates relationship processes in the study of sexuality” (p. 8), and more research that accounts for the dyadic processes inherent to most sexual activity (and, in turn, less reliance on individualistic explanatory models). The current study was able to respond to both of these calls, albeit with some limitations.

Perhaps most importantly, the correlational nature of our analyses prevented us from conclusively determining the direction of causality. Indeed, follow-up analyses indicated that the majority of the significant relations observed in the current study operate bidirectionally.Footnote 4 For instance, our original findings demonstrated that husbands’ positive interpersonal behaviors (but not wives’) were tied to sexual frequency, and our supplemental analyses revealed that sexual frequency was significantly associated with husbands’ positive interpersonal behaviors as well. Thus, although husbands who shower their wives with compliments and kisses might “get lucky” more often, it appears that husbands who have sex more often also feel more inclined to show affection outside of the bedroom. To offer another example, our primary analyses showed that husbands’ and wives’ sexual satisfaction was positively tied to their satisfaction with their marriages as a whole, but—consistent with the notion that these connections are reciprocal—a significant positive association was also observed in our follow-up analyses between husbands’ and wives’ marital satisfaction and their feelings of sexual satisfaction (for a similar pattern of results, see McNulty et al., 2014).

Although only a handful of studies have attempted to tease apart the nature of these associations, cross-lagged analyses suggest that the strength of the association between sexual feelings early in marriage and later marital quality does not differ from that between earlier marital quality and later sexual feelings (Henderson-King & Veroff, 1994). The growing use of lagged (e.g., Birnbaum, Reis, Mikulincer, Gilliath, & Orpaz, 2006; Yeh et al., 2006) and meditational models (e.g., Byers & Demmons, 1999; Fisher & McNulty, 2008; Meltzer & McNulty, 2010) among those researching sexuality promises to shed additional light on the complex interconnections between sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, overall relationship quality, and other nonsexual features of relationships. We encourage researchers to continue to use such approaches in order to foster a better understanding of the directionality of the associations between these important facets of couples’ relationships.

Theorists have long considered the sexual aspects of couples’ relationships to be part of a broader interpersonal and behavioral landscape, and future research would benefit from examining whether other behaviors (such as the performance of household tasks, the provision and receipt of support, or general communication patterns) are linked to how often couples have sex and how satisfying they find that sex—and their relationship more generally—to be. Before such understanding can be attained, however, one must recognize that the meaning of “sex” or what makes sex “satisfying” may vary from one person to another. To some, the pinnacle of sexual satisfaction could simply be achieving an orgasm; for others to feel sexually satisfied, they may need to feel appreciated by their partner during sex (see Pascoal, Narciso, & Pereia, 2014). Future studies should employ multi-item sexual satisfaction scales (e.g., Štulhofer, Buško, & Brouillard, 2010; Whitley, 1998) in order to capture a fuller picture of sexual satisfaction and its connection to the broader climate of marriage.

It is also worth noting that, although the first two waves of data collection took place in the early 1980s, the patterns reported here are by no means outdated. Despite changes in adolescents’ and young adults’ sexual attitudes, preferences, and behaviors over the last few decades (e.g., Heldman & Wade, 2010; Wells & Twenge, 2005), the quantity and quality of sex reported by married couples has remained remarkably stable over time. For instance, in Blumenstein and Schwartz’s (1983) groundbreaking study, they concluded that, “When the nonsexual parts of couples’ lives are going badly, their sex life suffers” (p. 202). Nearly 20 years later, Metz and Epstein (2002) reported “conflict…can play a direct or indirect negative role in sexual dysfunction through its injurious effect on the emotional environment of sexual activity as well as on the couple’s general relationship” (p. 143). The connection between affection and intimacy taking place outside of the bedroom in relation to feelings of sexual satisfaction has also been consistently documented (cf. L.B. Rubin, 1976; H. Rubin & Campbell, 2012).

A final consideration is the relative homogeneity of the sample. Specifically, participants were recruited from a largely rural area of the United States, and the majority of the sample was White, high school educated, and from a working-class background. Although theory suggests that individuals’ social identities shape their beliefs about normative sexuality (Fahs & Swank, 2011), some researchers have detected significant differences across social identities (e.g., Henderson-King & Veroff, 1994; Rao & DeMaris, 1995; Sassler, Addo, & Lichter, 2012), whereas others report less variation (e.g., Call et al., 1995; Christopher & Sprecher, 2000). Given these inconsistent findings, future studies should examine whether the current pattern of results is consistent across ethnic, educational, and class lines.

Conclusions

By most standards, a “satisfying” relationship is replete with affection, low in negativity, and complemented by a reasonably active and satisfying sex life. Although men and women who “behave badly” toward their partners outside of the bedroom do not necessarily have less sex, they often find their sex lives to be less satisfying. Perhaps more interestingly, whereas wives’ positive behaviors were associated with heightened feelings of sexual satisfaction among husbands (but not vice versa), husbands’—but not wives’—displays of positivity were tied to an increased incidence of sex. This latter finding lends credence to the proposed model of female sexual response and the notion that broader relationship dynamics may function as a sexual trigger (Basson, 2000). Clinicians focused on helping couples improve their sex lives often encourage husbands to cultivate more intimacy and show more affection inside of the bedroom (see B.W. McCarthy, Bodnar, & Handal, 2004); our findings lend support to the notion that such techniques may be effective outside of the bedroom as well (see, e.g., B.W. McCarthy, 1999). Those interested in bolstering spouses’ feelings of marital satisfaction, however, may want to emphasize that good sex appears to outshine plentiful sex. Indeed, when it comes to overall marital satisfaction, having a satisfying sex life and a warm emotional life appears to matter more than does having an active sex life.

Notes

Although other articles have been published using these data (e.g., Caughlin et al., 2000; Huston, Caughlin, Houts, Smith, & George, 2001; Miller et al., 2003), this is the only study that examines the interplay between sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, partners’ interpersonal behaviors, and spouses’ feelings of marital satisfaction. In their seminal paper involving a handful of the same variables considered in the present study, Huston and Vangelisti (1991) examined the extent to which partners’ positive behaviors, negative behaviors, and “sexual interest” were tied to marital satisfaction; their overall goal was to identify, and then subsequently connect, different types of socioemotional behaviors to feelings of marital satisfaction. The current study, on the other hand, examined spouses’ interpersonal behaviors in connection with the sexual aspects of their relationship, and then assessed whether those factors (specifically, spouses’ positive behaviors, negative behaviors, sexual frequency, and sexual satisfaction), considered in tandem, predicted marital satisfaction across 13 years of marriage. Thus, the focus of this article—and its specific hypotheses—is distinct from the ideas examined in other studies involving this data.

Although the general pattern of results does not change when both those who remained continuously married and those who ultimately divorced were included in the model, we also tested whether these two groups significantly differed across several of our variables of interest, as well as a number of sociodemographic characteristics (all of which were reported when couples had been married for approximately 1 year). Compared to their counterparts who ultimately divorced, wives who remained continuously married reported higher levels of sexual satisfaction and marital satisfaction, and couples who remained married reported lower levels of sexual frequency. The only other significant difference that was detected was that a greater proportion of husbands who remained married were employed during Phase 2, relative to the proportion observed among husbands who ultimately divorced. Spouses who remained married did not differ from those who divorced with respect to their positive and negative interpersonal behaviors, age at marriage, years of education, race, or total income.

Because random effects were not estimated for sexual frequency or sexual satisfaction, we were able to decompose the mediational effects using the traditional methods used in single-level models (see Kenny, Korchmaros, & Bolger, 2003).

All follow-up analyses are available from the first author upon request.

References

Aubin, S., & Heiman, J. R. (2004). Sexual dysfunction from a relationship perspective. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 477–517). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Basson, R. (2000). The female sexual response: A different model. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 51–65.

Basson, R. (2001). Human sex-response cycles. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 27, 33–43.

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2004). Sexual economics: Sex as female resource for social exchange in heterosexual interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 339–363.

Birnbaum, G. E., Mikulincer, M., & Austerlitz, M. (2013). A fiery conflict: Attachment orientations and the effects of relational conflict on sexual motivation. Personal Relationships, 20, 294–310.

Birnbaum, G. E., Reis, H. T., Mikulincer, M., Gillath, O., & Orpaz, A. (2006). When sex is more than just sex: Attachment orientations, sexual experience, and relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 929–943.

Blumstein, P., & Schwartz, P. (1983). American couples: Money, work, sex. New York: William Morrow.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616.

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 808–818.

Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 964–980.

Brotto, L. A. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 221–239.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141–154.

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 113–118.

Byers, E. S., & Demmons, S. (1999). Sexual satisfaction and sexual self-disclosure within dating relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 36, 180–189.

Call, V., Sprecher, S., & Schwartz, P. (1995). The incidence and frequency of marital sex in a national sample. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 639–652.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., & Rodgers, W. (1976). Quality of American life: Perception, evaluation, and satisfaction. New York: Russell Sage.

Campbell, L., Martin, R. A., & Ward, J. R. (2008). An observational study of humor use while resolving conflict in dating couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 41–55.

Carvalheira, A., Brotto, L. A., & Leal, I. (2010). Women’s motivations for sex: Exploring the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition, text revision criteria for hypoactive sexual desire and female sexual arousal disorders. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 1454–1463.

Caughlin, J. P., & Huston, T. L. (2002). A contextual analysis of the association between demand/withdraw and marital satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 9, 95–119.

Caughlin, J. P., & Huston, T. L. (2010). The flourishing field of flourishing relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2, 25–35.

Caughlin, J. P., Huston, T. L., & Houts, R. M. (2000). How does personality matter in marriage? An examination of trait anxiety, interpersonal negativity, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 326–336.

Christopher, F. S., & Kisler, T. S. (2004). Exploring marital sexuality: Peeking inside the bedroom and discovering what we don’t know—but should! In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 371–384). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Christopher, F. S., & Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 999–1017.

Davis, D., Shaver, P. R., & Vernon, M. L. (2004). Attachment style and subjective motivations for sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1076–1090.

DeLamater, J. (1987). Gender differences in sexual scenarios. In K. Kelley (Ed.), Females, males and sexuality: Theories and research (pp. 127–129). Albany: State University of New York Press.

DeLamater, J., & Hyde, J. (2004). Conceptual and theoretical issues in studying sexuality in close relationships. In J. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 7–30). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Diamond, L. M., & Huebner, D. M. (2012). Is good sex good for you? Rethinking sexuality and health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 54–69.

Edwards, J. N., & Booth, A. (1976). Sexual behavior in and out of marriage: An assessment of correlates. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 38, 73–81.

Elliott, S., & Umberson, D. (2008). The performance of desire: Gender and sexual negotiation in long-term marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 391–406.

Fahs, B., & Swank, E. (2011). Social identities as predictors of women’s sexual satisfaction and sexual activity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 903–914.

Feeney, J. A. (2002). Attachment, marital interaction, and relationship satisfaction: A diary study. Personal Relationships, 9, 39–55.

Finkel, S. E. (1995). Causal analysis with panel data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fisher, T. D., & McNulty, J. K. (2008). Neuroticism and marital satisfaction: The mediating role played by the sexual relationship. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 112–122.

Floyd, K., Hess, J. A., Miczo, L. A., Halone, K. K., Mikkelson, A. C., & Tusing, K. J. (2005). Human affection exchange: VIII. Further evidence of the benefits of expressed affection. Communication Quarterly, 53, 285–303.

Gathome-Hardy, J. (2000). Alfred C. Kinsey: Sex the measure of all things. A biography. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press (Originally published, 1998).

Haning, R. V., O’Keefe, S. L., Randall, E. J., Kommor, M. J., Baker, E., & Wilson, R. (2007). Intimacy, orgasm likelihood, and conflict predict sexual satisfaction in heterosexual male and female respondents. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 33, 93–113.

Hassebrauck, M., & Fehr, B. (2002). Dimensions of relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 9, 253–270.

Hayes, R. D. (2011). Circular and linear modeling of female sexual desire and arousal. Journal of Sex Research, 48, 130–141.

Heldman, C., & Wade, L. (2010). Hook-up culture: Setting a new research agenda. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7, 323–333.

Henderson-King, D. H., & Veroff, J. (1994). Sexual satisfaction and marital well-being in the first years of marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 509–534.

Hetherington, E. M. (2003). Intimate pathways: Changing patterns in close personal relationships across time. Family Relations, 52, 318–331.

Horan, S. M., & Booth-Butterfield, M. (2010). Investing in affection: An investigation of affection exchange theory and relational qualities. Communication Quarterly, 58, 394–413.

Hurlbert, D. F., Apt, C., & Rabehl, S. M. (1993). Key variables to understanding female sexual satisfaction: An examination of women in nondistressed marriages. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 19, 154–165.

Huston, T. L. (2009). What’s love got to do with it? Why some marriages succeed and others fail. Personal Relationships, 16, 301–327.

Huston, T. L., Caughlin, J. P., Houts, R. M., Smith, S., & George, L. J. (2001). The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 237–252.

Huston, T. L., Robins, E., Atkinson, J., & McHale, S. M. (1987). Surveying the landscape of marital behavior: A behavioral self-report approach to studying marriage. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Family processes and problems: Social psychological aspects (pp. 45–72). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Huston, T. L., & Vangelisti, A. L. (1991). Socioemotional behavior and satisfaction in marital relationships: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 721–733.

Impett, E. A., Strachman, A., Finkel, E. J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Maintaining sexual desire in intimate relationships: The importance of approach goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 808–823.

Johnson, M. D., Cohan, C. L., Davila, J., Lawrence, E., Rogge, R. D., Karney, B. R., … Bradbury, T. N. (2005). Problem-solving skills and affective expressions as predictors of change in marital satisfaction. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 73, 15–27.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 3–34.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Kenny, D. A., Korchmaros, J. D., & Bolger, N. (2003). Lower level mediation in multilevel models. Psychological Methods, 8, 115–128.

Knobloch, L. K. (2007). Perceptions of turmoil within courtship: Associations with intimacy, relational uncertainty, and interference from partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 363–384.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Leiblum, S. R. (1998). Definition and classification of female sexual disorders. International Journal of Impotence Research, 10, S104–106.

Lyons, K., & Sayer, A. G. (2005). Longitudinal dyad models in family research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1048–1060.

McCarthy, B. (2003). Marital sex as it ought to be. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 14, 1–12.

McCarthy, B. W. (1999). Relapse prevention strategies and techniques for inhibited sexual desire. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 25, 297–303.

McCarthy, B. W., Bodnar, L., & Handal, M. (2004). Integrating sex therapy and couple therapy. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 573–593). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McNulty, J. K., Wenner, C. A., & Fisher, T. D. (2014). Longitudinal associations among relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and frequency of sex in early marriage. Archives of Sexual Behavior. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0444-6.

Meltzer, A. L., & McNulty, J. K. (2010). Body image and marital satisfaction: Evidence for the mediating role of sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 156–164.

Metz, M. E., & Epstein, N. (2002). Assessing the role of relationship conflict in sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28, 139–164.

Miller, P. J. E., Caughlin, J. P., & Huston, T. L. (2003). Trait expressiveness and marital satisfaction: The role idealization processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 65, 978–995.

Pascoal, P. M., Narisco, I. S. B., & Pereira, N. M. (2014). What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 22–30.

Peplau, L. A., Fingerhut, A., & Beals, K. P. (2004). Sexuality in the relationships of lesbians and gay men. In J. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 350–369). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rao, K. V., & DeMaris, A. (1995). Coital frequency among married and cohabiting couples in the United States. Journal of Biosocial Science, 27, 135–150.

Raudenbush, S. W., Brennan, R. T., & Barnett, R. C. (1995). A multivariate hierarchical model for studying psychological change within married couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 9, 161–174.

Renaud, C., Byers, E. S., & Pan, S. (1997). Sexual and relationship satisfaction in mainland China. Journal of Sex Research, 34, 399–410.

Richters, J., de Visser, R., Rissel, C., & Smith, A. (2006). Sexual practices at last heterosexual encounter and occurrence of orgasm in a national survey. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 217–226.

Ridley, C. A., Cate, R. M., Collins, D. M., Reesing, A. L., & Lucero, A. A. (2006). The ebb and flow of marital lust: A relational approach. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 144–153.

Ridley, C., Ogolsky, B., Payne, P., Totenhagen, C., & Cate, R. (2008). Sexual expression: Its emotional context in heterosexual, gay, and lesbian couples. Journal of Sex Research, 45, 305–314.

Robins, E. R. (1985). A theoretical and empirical investigation of compatibility testing in marital choice. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

Rubin, H., & Campbell, L. (2012). Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction: A dyadic diary analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 224–231.

Rubin, L. B. (1976). Worlds of pain: Life in the working-class family. New York: Basic Books.

Russell, V. M., & McNulty, J. K. (2011). Frequent sex protects intimates from the negative implications of their neuroticism. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2, 220–227.

Sassler, S., Addo, F. R., & Lichter, D. T. (2012). The tempo of sexual activity and later relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 708–725.

Schnarch, D. M. (1997). Passionate marriage: Sex, love, and intimacy in emotionally committed relationships. New York: Owl Books.

Schoenfeld, E. A., Bredow, C. A., & Huston, T. L. (2012). Do men and women show love differently in marriage? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 1396–1409.

Schwartz, P., & Rutter, V. (1998). The gender of sexuality. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

Sims, K. E., & Meana, M. (2010). Why did passion wane? A qualitative study of married women’s attributes for declines in desire. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 36, 360–380.

Sprecher, S. (1998). Social exchange theories and sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 32–43.

Sprecher, S. (2002). Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment and stability. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 190–196.

Štulhofer, A., Buško, V., & Brouillard, P. (2010). Development and bicultural validation of the New Sexual Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Sex Research, 47, 257–268.

Terman, L. M. (1938). Psychological factors in marital happiness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Theiss, J. A., & Nagy, M. E. (2010). Actor-partner effects in the associations of between relationship characteristics and reactions to marital sexual intimacy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 1089–1109.

Tiefer, L. (1991). Historical, scientific, clinical, and feminist criticisms of “The human sexual response cycle” model. Annual Review of Sex Research, 2, 1–23.

Wells, B. E., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Changes in young people’s sexual behavior and attitudes, 1943–1999: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 9, 249–261.

Whitley, M. P. (1998). Sexual satisfaction inventory. In C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Schreer, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 519–521). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yeh, H.-C., Lorenz, F. O., Wickrama, K. A. S., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H. (2006). Relationships among sexual satisfaction, marital quality, and marital instability at midlife. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 339–343.

Yucel, D., & Gassanov, M. A. (2010). Exploring actor and partner correlates of sexual satisfaction among married couples. Social Science Research, 39, 725–738.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (SBR-9311846) and the National Institute of Mental Health (MH-33938).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schoenfeld, E.A., Loving, T.J., Pope, M.T. et al. Does Sex Really Matter? Examining the Connections Between Spouses’ Nonsexual Behaviors, Sexual Frequency, Sexual Satisfaction, and Marital Satisfaction. Arch Sex Behav 46, 489–501 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0672-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0672-4