Abstract

In this article I argue for rule-based, non-monotonic theories of common law judicial reasoning and improve upon one such theory offered by Horty and Bench-Capon. The improvements reveal some of the interconnections between formal theories of judicial reasoning and traditional issues within jurisprudence regarding the notions of the ratio decidendi and obiter dicta. Though I do not purport to resolve the long-standing jurisprudential issues here, it is beneficial for theorists both of legal philosophy and formalizing legal reasoning to see where the two projects interact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This article aims to motivate and implement expansions upon the factor based theory of precedential constraint offered by Horty (2011) and Horty and Bench-Capon (2012). These expansions improve upon the original theory. Further, they reveal some of the interconnections between formal theories of judicial reasoning and traditional issues within jurisprudence regarding the notions of the ratio decidendi and obiter dicta. I do not purport to resolve the jurisprudential issues here, but I think it is beneficial for theorists both of jurisprudence and formalizing legal reasoning to see where the two projects interact.

2 A brief case for using nonmonotonic logics to formalize legal reasoning

In common law systems, judges of inferior courts are bound by a doctrine of precedent. This requires, roughly, that they must follow the result or reasoning from a past case in deciding a present one, even if they disagree with that past case. These judges also have the power to distinguish past cases from a present one, which allows them to diverge from the result or reasoning in the past cases because the current case is different in some important respect. A number of theories modeling this sort of reasoning have been offered, such as those of Ashley (1990), Brewer (1996), Bench-Capon and Sartor (2003), Roth (2003), Horty and Bench-Capon (2012). It should be noted that much work in AI and Law is only partially focused on the constraining force of precedent. For example, in Prakken and Sartor (1998) cases where the judge is bound to follow the rule of precedent (case where the rule need not be “broadened” in their terminology), are only a small part of their focus. This is proper because the force of precedent extends well past instances where the judge is forced to follow a case she thinks is wrongly decided, including cases that the judge could distinguish from the past case. We might call this the “persuasive” rather than “constraining” force of precedent and it inarguably plays a large role in legal reasoning. Nonetheless, I will be focused on the constraining force of precedent in this article, not because I think its persuasive force is unimportant, but because I think the constraining force itself merits independent discussion.Footnote 1

Some of these, such as Horty and Bench-Capon (2012), make use of legal rules, while others, such as Roth (2003) do not. The latter are often called case-based. I think both sorts of approaches have their advantages, and the modifications I make in Sect. 4.2.3 attempt to import some of the insights of case-based systems into a rule based framework. A significant, though certainly not decisive, argument for adopting a rule based framework is that it recognizes the long-standing common law notions of ratio decidendi and obiter dicta.Footnote 2 The ratio decidendi (the ratio) is the “the principle or rule of law on which a court’s decision is founded…a general rule without which the case must have been decided differently”(Garner 2004, p. 582). Obiter dicta (dicta) refers to “a judicial comment made during the course of delivering a judicial opinion, but one that is unnecessary to the decision in the case and therefore not precedential (although it may be considered persuasive)”(Garner 2004, p. 490). It is not clear if there is any logical entity that can be identified as the ratio on the case based approach. Further, such approaches make it difficult to identify any non-trivial portion of the case as dicta.

Again, I stress that I do not think that problem for case-based approaches is insurmountable. Further, even if the problem did prove irresolvable, one might reasonably maintain a case-based theory and reject the ratio/dicta distinction. Still, I think the notions of ratio and dicta are venerable enough that we ought to try to retain them in our theorizing. The rule-based approach is able to do this most directly.

The importance of the notion of ratio in the context of AI and Law goes back to Branting (1991, 1993), the earlier of which informs one of my modifications. It received a thorough rule-based investigation in Prakken and Sartor (1998). Though the rule based approaches best capture the notions of ratio and dicta, they are most effective when combined with features originating in case-based approaches, namely, features that provide a tractable representation of the facts of a case. Ashley’s (1990, 1991) HYPO represented the facts of cases coupled with the idea of dimensions, which represented relevant legal issues as a spectrum spanning from most favorable to the plaintiff to the most favorable to the defendant. In HYPO, the facts determined which dimensions were relevant, e.g. dimensions related to negligence would be irrelevant in a strict liability case. Further, the facts determined where the case was located on the relevant dimensions, e.g. the facts determine whether a tort case is strongly pro-plaintiff or defendant with respect to the presence of injury or the foreseeability of that injury. Aleven’s (1997) CATO by-passed dimensions, instead representing the case in terms of factors, which can be thought of as particular points on the axis of a dimension. Factors are essentially facts with a polarity favoring one party or the other. They can be weighed to show that some are more influential than others. Indeed, the outcome of a case in CATO is a function of the weights of the factors: roughly, a pro-plaintiff outcome shows that the pro-plaintiff factors were “heavier” than the pro-defendant factors and vice versa. Further CATO introduced the notion of a factor-hierarchy, which established links by which lower level factors could determine high-level ones. For example, suppose the defendant in a negligence action had previously injured someone in the same manner as the plaintiff was injured. Then we can represent this as a factor, previousharmfulact, which favors a higher order factor for the foreseeability of the plaintiff’s injury. The idea of a factor-hierarchy has similarities with the modifications I advocate for frame-work cases.

With factors in hand, on can construct rules using them, representing inferences from a factor or set of factors to a conclusion either regarding the result in the case or the presence of a higher order factor, see (Prakken and Sartor 1998). Once such a rule-based framework is adopted, questions of what sort of logic should be used arise, including: Should the logic be monotonic or nonmonotonic? The argument for a nonmonotonic logic is fairly straight forward. Hart (1948) famously observed that legal rules are subject to seemingly many exceptions. In fact, he claims, they may be subject to exceptions incapable of exhaustive statement (Hart 1961, p. 136). To give a realistic example, consider the contract law rule (R1) that an oral agreement to perform a service in exchange for money is a valid contract. R1 does not apply if the service cannot be performed in less than a year [The Restatement (Second) of Contracts 1981, Section 130]. Nor does R1 apply if the service is an illegal act, such as a forging a document [The Restatement (Second) of Contracts 1981, Section 178]. Likewise, no valid contract arises if one of the parties is legally incapacitated at the time of the agreement [The Restatement (Second) of Contracts 1981, Section 12]. Even this does not exhaust the set of exceptions, let alone the exceptions to the exceptions [The Restatement (Second) of Contracts 1981, Section 130]. To give a simplified example that I will use throughout this article, consider Hart (1958)’s case of a law saying “vehicles are prohibited in the park.” This law would be (one hopes) subject to exception in the case of an ambulance driving to pick up an injured park-goer, or a fire truck driving to put out a fire in the park, or a military truck moving into position to fend off an invasion.

It is important to note that the issue of exceptions is not a matter of semantic ambiguity. A term like “vehicle” may have borderline cases—perhaps a skateboard is one. However, there is no question whether an ambulance is a vehicle, and likewise for fire trucks and military trucks. Each of the exceptional cases are clearly within the semantic content of the prohibition. Indeed, the cases could not be exceptions if they did not fall within the stated prohibition.

Hart’s observation applies to both statutory and common law rules, though only the common law context is my concern here. In that context, rules are extracted from the opinions in past cases. The judicial process of distinguishing a case is easily understood as determining that the present case is an exception to the rule from a past one. Given that common law reasoning involves rules with exceptions, it is natural to formalize it using a nonmonotonic logic as nonmonotonic logics were developed expressly to formalize rules with exceptions (see McCarthy 1980). Nonmonotonic logics allow for a non-destructive updating of theories to accommodate new information about exceptional cases. When a judge determines the present case is exceptional with respect to the rule from a past case and hence distinguishes the case, this information can be directly added into a nonmonotonic theory of legal rules. A monotonic theory would require either (1) that each rule has no “exceptions,” properly understood, and instead the negation of each have been calling “exceptions” is built into the rule as a precondition, or (2) that when a present case is distinguished from a past one, the rule from the past case is removed and replaced by a new rule which effectively excludes the present case from its scope.

Each alternative is deeply flawed. (1) is precisely the well-known “qualification problem” that spurred the development of nonmonotonic logics, and I won’t add anything to that literature here, though Thielscher’s (2000) offers a good summary for those interested. Besides formal difficulties, (1) is also at odds with the evidence and norms of common law judicial practice. Regarding the evidence, as one does not find cases involving rules with extensive lists of preconditions, though surely even very basic rules like the prohibition of ambulances have many preconditions. Regarding the norms, Schauer (2006) explains,

“It is the merit of the common law,” Oliver Wendell Holmes observed, “that it decides the case first and determines the principle afterwards.” That the decision of a particular case holds pride of place in common law methodology is largely uncontroversial. And indeed so too is the view that this feature of the common law is properly described as a “merit.” Treating the resolution of concrete disputes as the preferred context in which to make law—and making law is what Holmes meant in referring to “determin[ing] the principle”—is the hallmark of the common law approach.… Moreover, so it is said, making law in the context of deciding particular cases produces lawmaking superior to methods that ignore the importance of real litigants exemplifying the issues the law must resolve.

The common law’s intense (Schauer might say, “myopic”) focus on the facts of the case before it cautions against examining distant hypothetical circumstances. Yet such examination would be demanded if judges were to reason with legal rules of the sort envisioned by (1).

(2) yields bad jurisprudential consequences. For example, since the power to distinguish is held by all courts, inferior and superior, (1) entails that inferior courts have to the power remove a legal rule imposed by a superior one. Further, (2) has the jarring result that the past case was decided using the (in some sense) wrong rule, since that rule needed to be removed and replaced by the one imposed by the current court. This also means, as Lamond (2005) shows, that an individual rule cannot become entrenched in the law, since the rules themselves are very often changing.

Most troublingly, (2) posed the following dilemma: either we treat the distinguished past case as having been nullified and treat the present case as introducing the new rule or we treat the present case as changing the rule attributed to the past case and not introducing a new rule. The first alternative cannot be correct, because it demands that the past case loses its status as precedent. The past case should no longer be treated as binding in future cases, but this is not what happens to past cases that have been distinguished. They are still treated as precedent in future cases.

The second alternative is also incorrect, because it conflicts with legal practice. Suppose a past case, C1, initially involved the rule, R1, that no vehicles are permitted in the park. Suppose a later case, C2, involved an ambulance and distinguished C1. Let C2 distinguish C1 by changing the rule involved in C1 from R1 to R2, which states that no vehicles, except ambulances, are permitted in the park. It should then be permissible to cite C1 to invoke R2. But this is not permissible in legal practice. A judge (or attorney) cannot cite C1 to invoke the rule with the ambulance exception. Should another case with an ambulance come along, the most on point case is C2, not C1.

To give a realistic example, in Police Department v. Mosley (1972, p. 95) the United States Supreme Court reiterated the principle that “above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content [citations omitted].” Ten years later, this rule was found to be subject to an exception for visual depictions of child pornography in New York v. Ferber (1982). No sane attorney in case involving child pornographer will cite Mosley for the rule that the government cannot restrict expression because of its message, ideas, subject matter, or content, unless that expression is child pornography. If you want to invoke the exception for child pornography, you have to cite Ferber. Thus a rule-based approach built upon a nonmonotonic logic seems required to best capture the force of precedent in legal reasoning.

3 A factor based approach to precedent

Recently, Horty (2011) and Horty and Bench-Capon (2012) have offered an account of precedential rules using prioritized defaults involving sets of factors/reason. Call this theory “the HB-C Theory.” The HB-C Theory is closely related to those of Lamond (2005), and Prakken and Sartor (1996, 1998). In this section I will introduce the HB-C Theory and then implement improvements to deal with a wider range of common law cases.

For the purpose of reasoning with precedent, common law reasoners are concerned with the published opinions from past cases, which I will refer to just as “cases” for convenience. Following, generally, Ashley (1991), and more particularly Aleven (1997), the HB-C Theory divides a case into four components: (1) factors/reasons in favor of the plaintiff, which we will denote “R p n ” where n is a number used to differentiate multiple reasons for the plaintiff; (2) reasons in favor of the defendant, which we will denote “R d n ” where n is a number used to differentiate multiple reasons for the defendant; (3) an outcome, which we will denote with a “P☺” when it is a ruling in favor of the plaintiff and a “D☺” when it is in favor of the defendant; (4) a (only one) rule, which we will denote “Rule n ” where n is a number used to differentiate different rules from different cases.

The form of the rule is the most innovative aspect of the theory, as the rule is a conditional created using the other three components. The consequent of the conditional is the outcome from the case. The antecedent of the conditional is a subset of the reasons for the party that the outcome favors. For example, a rule may look like this: {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\), R p2 , R p3 } → P☺, which says “if these three reasons for the plaintiff obtain, then rule for the plaintiff.” A rule may not look like this: {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\), \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } → P☺, because not all the reasons in the antecedent are not reasons for the party that the ruling favors.Footnote 3 We will soon discuss what happens when these rules conflict and what role nonmonotonicity plays, but first an example is helpful.

Let’s briefly examine an example following the discussion of contract law in Sect. 2 to help illustrate this theory. Suppose there was an oral agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant that the defendant would provide 50 widgets on July 4th to the plaintiff in exchange for $50. The plaintiff pays the defendant and the defendant fails to deliver the widgets. The plaintiff sues for specific enforcement and prevails.Footnote 4 In this highly simplified case, we can say that the oral agreement is a reason in the plaintiff’s favor. From this case when then get the following rule in which \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) is the presence of an oral agreement:

-

Rule 1 : {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } → P☺.

The precedential import of this bare bones case is simply Rule1, saying that if there is an oral agreement, then rule for the plaintiff (enforce the contract). If this rule were understood monotonically we would run into obvious problems, as it would require future courts to enforce every oral agreement. The innovation is to understand Rule1 as a default, that is, a rule that can be overridden in exceptional cases.

The defaults can then be prioritized to deal with conflicts. For example, consider a default representing the prohibition on vehicles in the park: If D has a vehicle, and D’s vehicle is in the park, then rule for P. We can now add the default that makes an exception for ambulances, “If D has a vehicle, and D’s vehicle is in the park, and D’s vehicle is an ambulance, then rule for D.” The second default is given a higher priority than the first default, which means that only the second may be applied when both are triggered. Thus only the second may be used to infer from the premise that there is an ambulance in the park to the conclusion that the ambulance operator should not be punished. We can say that the first rule is overridden by the second in these situations. The first (lower priority) default remains within the theory; it is not destroyed. It is available to allow us to infer that a vehicle is not permitted in the park, provided we do not also know that that vehicle is an ambulance.Footnote 5

This naturally raises the question of when a default can be overridden. If Rule1 can be overridden at any time, it does not seem to constrain future judges and hence cannot be precedential. The genius of the theory lies in its answer. From each case we extract not only a rule but a weighing of reasons. Given the rule, which incorporates the outcome, we can see that those reasons for the prevailing party in the antecedent were deemed to outweigh all the reasons favoring the losing party. I’ll use “>” to denote this relation of outweighing. This weighing of reasons is binding, so future courts may not alter it. A rule may only be overridden if the current case involves a novel set of opposing reasons, i.e. a set of reasons that (1) favors the party that loses according to the rule and (2) is not a subset of the set of reasons previously outweighed by the reasons in the rule.

In our simple example, we can see that {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } outweighs the empty set of reasons for the defendant. That is, {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } > Ø. Its precedential force is thus very weak (trivial, in fact). Rule1 must be followed only when \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) obtains and there are no reasons in favor of the defendant. Now let’s make the example more complicated. Suppose that widget components greatly increase in price after the oral agreement. It will now cost the defendant $10,000 dollars to make the widgets. This is a reason (undue hardship) in the defendant’s favor, \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\). Suppose the outcome of the case remains in favor of the plaintiff. The rule in this example is still Rule1, but the precedential force is stronger than it was in the first example. This case tells us that {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } > {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) }. Given this case, Rule1 must be followed in a future cases where \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) obtains (there is an oral agreement) and either there are no reasons in favor of the defendant or the only reason in favor of the defendant is \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\).

Suppose later a new case comes along with the same facts, except in the interim between the previous case and the new agreement widgets were declared illegal. This novel reason in favor of the defendant (\({\text{R}}_{2}^{\text{d}}\)) means the judge in this case is not bound to follow Rule1. She may distinguish this case on the basis of this reason. If she does so, then she introduces the following new default rule:

-

Rule 2 : {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\), \({\text{R}}_{2}^{\text{d}}\) } → D☺.

Rule2 trumps Rule1, which is accommodated in the logic by assigning Rule2 a higher priority than Rule1. Note that Rule1 is not deleted and replaced by Rule2; it simply does not apply when Rule2 does. This is how the theory captures the difference between distinguishing a precedent and overruling it. Distinguishing occurs when a rule is trumped, while overruling occurs when the rule is deleted and replaced.

The judge’s decision to apply Rule2 introduces the weighing {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\), \({\text{R}}_{2}^{\text{d}}\) } > {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } corresponding to the preference for Rule2 over Rule1.Footnote 6 Judges in future cases now have to abide by this weighing, as well as the weighing from the older case, namely, {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } > {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) }. In this way more and more relative weights are established as cases are decided. As more relative weights are established the number of novel sets of reasons decreases and future judges become more constrained.Footnote 7

We now have, at last, an account of legal rules that does not require endless searching for exceptions before one can arrive at the rule. Horty’s account, building on Larmond’s (2005) theory, also explains how legal rules can become entrenched. The rule from a case need not involve all of the reasons for the prevailing party that obtain, so the same rule can be applied in a number of cases involving different reasons. As courts decide to apply the rule in the face of different novel sets of reasons, future courts are further limited in their ability to override (i.e. distinguish) the rule. Thus the rule becomes more deeply entrenched in the law.

4 Improving the HB-C theory

The HB-C theory has much to recommend it, but it can be improved upon to deal with more complex legal rules. Two types of cases pose problems to the theory as it stands. Horty’s theory requires the extraction of a single rule from each past case that favors the prevailing party. It also requires that the reasons involved in the rule and the weighings are present in the case, i.e. not merely hypothetical. In the next two sections I will examine cases that challenge these requirements. Both types of cases raise the jurisprudential difficulties associated with the scope of precedent. I return to this issue in Sect. 6.

4.1 Accommodating overdetermined cases

The first problematic sort of cases are those in which the court makes a decision on the basis of multiple legal rules, each of which would be sufficient for the decision. These are sometimes known as “cases with alternative holdings” (Lucas 1983) or “judgments on alternative grounds” (Siegler 1984). I think a less ambiguous term is “overdetermined cases” because it makes clear that the outcome of each of the alternative holdings is the same. Consider the case of The Newport Yacht Basin Ass’n v. Supreme Northwest Inc. (2012) (henceforth NYBA). Here the defendant prevailed and was awarded attorney’s fees “based upon a prevailing party provision of a purchase and sale agreement, a contractual indemnity provision, and principles of equitable indemnity” (NYBA 2012, p. 75). According to the trial court judge, each of these was sufficient to justify the awarding of attorney’s fees. The appellate court rejected each one of these justifications, but that does not matter for our purposes.

Horty’s theory cannot handle this case because it insists that each case have only one legal rule. It would combine all the reasons favoring the defendant regarding the prevailing party provision (PPP), the indemnity provision (IP), and equitable indemnity (EI) into one rule. But this does violence to the text of the opinion. Further, if that jumbled rule were the holding in the case, then the appellate court need not reject each basis separately because rejecting just one would be to reject the rule.

The natural solution is to allow cases to have multiple rulings. Assuming one reason in the antecedent for each rule, we could characterize the three rules from the trial court decision in NYBA as follows:

-

Rule1 (PPP): {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) } → D☺

-

Rule2 (IP): {\({\text{R}}_{2}^{\text{d}}\) } → D☺

-

Rule3 (EI): {R d3 } → D☺

Here \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) is the PPP of the contract, which favors the defendant. \({\text{R}}_{2}^{\text{d}}\) is the IP, which also favors the defendant. R d3 stands for the equitable reason in favor of finding indemnity, which favors the defendant.Footnote 8 Since all rules are understood as triggered and untrumped in this case, they all have a priority greater than the strongest pro-plaintiff rule (using all the pro-plaintiff factors in its antecedent) in the case.

The set of all reasons favoring the plaintiff can likewise be simplified, let’s call the result R p. With the aforementioned three rules we get the following three constraints on the weight of reasons: {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) } > R p, {\({\text{R}}_{2}^{\text{d}}\) } > R p, {R d3 } > R p. The reasons in each antecedent outweigh the all the reasons for the plaintiff. This seems proper since each rule was supposed to be sufficient to decide the case for the defendant.

Importantly, allowing overdetermined cases to have multiple rules does not significantly alter the underlying logic of the theory. An overdetermined case is equivalent to multiple regular cases involving the exact same reasons as the overdetermined case but each introducing a different legal rule. That is, NYBA understood as a case with multiple rules is equivalent to three cases, each involving {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\), \({\text{R}}_{2}^{\text{d}}\), R d3 } and R p, with one case using Rule1, another using Rule2, and the third using Rule3.

4.2 Accommodating framework cases

The second troubling sorts of cases are what I’ll call “framework cases.” These are cases, usually decided by higher courts, which establish a framework to deal with future cases that may have very different facts. These decisions seem to introduce rules that go beyond what is needed to decide the current case.

Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) offers a well-known example. In that case the US Supreme Court addressed the question of whether Pennsylvania’s and Rhode Island’s statutes that provided money to religious primary schools subject to state oversight violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The court introduced a three-pronged test and ultimately ruled that both programs did violate the Establishment Clause. The “Lemon Test” as it became known, was the following:

Three such tests may be gleaned from our cases. First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion [citing Board of Educ. v. Allen (1968)]…finally, the statute must not foster “an excessive government entanglement with religion [citing Walz v. Tax Comm’n of N.Y.(1970)].” (Lemon v. Kurtzman 1971, p. 613)

The Lemon court held that the statutes had a secular legislative purpose (they passed the first prong), but they fostered an excessive government entanglement with religion (they failed the third prong) due to the government oversight (Lemon v. Kurtzman 1971, p. 614–615). The court declined to determine whether each statute’s principal or primary effect was one that neither advances nor inhibits religion (ignoring the second prong), since failing the third prong meant the statutes were invalid anyway.

In cases like this, the HB-C theory will select only a rule corresponding to the third prong, because that is the rule which is used to get the pro-plaintiff outcome. If we follow the court in thinking that the third prong is just the rule from Walz, then Lemon is simply the application of a prior rule in a new context and the other two prongs are treated as dicta. Perhaps this is the best understanding of Lemon, but it’s not the most common. The Lemon Test was taken quite seriously, even if the court may have ultimately abandoned it.Footnote 9 This requires treating each prong as a ratio, because a single rule combining all three prongs would require too much to invalidate a statute.

I think the theory can be modified to accommodate the standard interpretation of the Lemon Test; I leave the question of whether it ought to be so modified for constitutional law scholars. The modification that first comes to mind is the previous one of allowing multiple rules in one case. Let \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) be the presence of a secular legislative purposeFootnote 10 (remember, the defendant wins on the first prong). Let \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) be the presences of excessive entanglement between the government and religion. The rules corresponding to the prongs are as follows:

-

Rule1 (1st prong, secular legislative purpose): {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) } → D☺

-

Rule2 (2nd prong, primary effect on religion): ??

-

Rule3 (3rd prong, excessive entanglement): {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } → P☺

This raises a number of problems. First, it tells us nothing about the second prong since there is no ruling with respect to that prong. There is no finding that the statutes have a primary effect of advancing or inhibiting religion, but also no finding that they lack that primary effect. Hence, within the confines of the current theory there is no rule for this prong. Second, Rule1 and Rule3 are in conflict. Both Rule1 and Rule3 are triggered in this case, since \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\) and \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) both obtain, and each demands a contrary outcome.

We can resolve the second problem by imposing a priority on Rule1 and Rule3, ensuring that Rule3 trumps Rule1. Still, this is an unattractive characterization of the test. It is not that the third prong is more important or more applicable than the first. Rather, it is that failure to meet the requirements of any prong results in the plaintiff’s victory (the statute is invalidated). We might try to capture this via the following:

-

Rule1 (1st prong, secular legislative purpose): {??} → P☺

-

Rule2 (2nd prong, no primary effect on religion): ??

-

Rule3 (3rd prong, no excessive entanglement): {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } → P☺

Now there is no need for prioritizing one rule over the other. The relation between the rules and their respective prongs is more systematic as each rule represents the conditions for failing the respective prong, whereas in the first attempt some rules characterized passing the respective prong while others characterized failing it.

Of course, the question marks still indicate a serious problem with Rule1. The court discusses reasons relevant to this prong, but ultimately determines that the weight of those reasons favor the defendant. Hence I cannot put the pro-plaintiff reasons regarding the second prong into the antecedent of Rule1 because the resulting weighing would favor those reasons over the pro-defendant reasons, which is exactly opposite the result reached by the court.

4.2.1 A first attempt

Three options are available at this point. One, close to the view discussed supra at Sect. 4.2, is to take the court’s citation to Allen seriously. Allen had a pro-defendant outcome, but the language of secular purposes and primary effects on religion therein is quoted from School Dist. v. Schempp (1963). Schempp had a pro-plaintiff outcome, so it contains a rule with a pro-plaintiff consequent. Actually, to get the two distinct prongs that the Lemon court derives, Schempp needs to be understood as an overdetermined case with two pro-plaintiff rules. I think such a reading is plausible.Footnote 11 The court in Allen is then understood as distinguishing the case there from Schempp. The citation to Allen is understood as an elliptical way of restating the rules from Schempp and those rules meet all the requirements of our theory.

In the end, the result is that Rule1 and Rule2 are simply imported from Schempp. Letting R p3 be the presence of a secular legislative purpose, and R p2 be the presence of excessive entanglement, we get the following rules from Schempp:

-

Rule1: {R p2 } → P☺

-

Rule2: {R p3 } → P☺

This is entirely unproblematic for our theory, because both R p2 and R p3 obtain in Schempp.

This strategy means the second prong receives no new precedential force as it is simply a reminder of the other rule in Schempp.Footnote 12 That seems correct. This strategy also treats the discussion of the first prong in Lemon as an explanation that the reason from one of the rules in Schempp does not obtain in the present circumstance. The rule does not receive any new precedential force. Some might think this is incorrect, since it makes a large portion of the opinion irrelevant to its precedential force. One may want to say that part of the precedential import of Lemon is that any statute with content and legislative history equivalent to that of the Pennsylvania or Rhode Island statutes will pass the first prong, i.e. such statutes must be deemed to have a secular legislative purpose. Further, this approach also makes it difficult to understand why the Lemon test was viewed as a novel three part test instead of a single new rule with a reminder of past rules.Footnote 13 Due to these concerns, I favor the approach in the next section.

4.2.2 A second attempt: hypothetical reasons

A second strategy is to say that we should forget about the citations and instead remove the requirement that the rule(s) in a case involve reasons found in that case.Footnote 14 This moves us away from the common law’s focus on the facts before it, but perhaps this is a feature of appellate court precedent. Allowing rules involving hypothetical reasons opens up a number of possibilities. First, it allows us characterize Rule2. Second, it allows us to characterize the prongs using rules that do not conflict. Let \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) be the absence of a secular purpose, R2 p be the presence of a primary effect of advancing or inhibiting religion, and R p3 be the presence of excessive entanglement. The resulting characterization of the Lemon test is this:

-

Rule1 (1st prong, absence of secular legislative purpose): {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) } → P☺

-

Rule2 (2nd prong, primary effect on religion): {R p2 } → P☺

-

Rule3 (3rd prong, excessive entanglement): {R p3 } → P☺

This gives a clean characterization of the test using three non-conflicting rules. It also does not depend on the understanding of any past cases, meaning Lemon could be read as introducing three new rules.

Yet, there is a problem with this strategy. The court finds that \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) does not obtain and refrains from determining whether or not R p2 obtains. How can we then assign weight to those reasons? If we confine ourselves assigning weight only to reasons found to obtain, the precedential force given Rule1 and Rule2 by Lemon is very weak.Footnote 15 The rules impose the weightings of \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) > Ø and R p2 > Ø.

This weighing is worrying because if \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) obtains, i.e. the statute lacks a secular legislative purpose, then it seems as if a very strong opposing reason should be required to outweigh that reason. One possibility is to make Rule1 a strict rule, which is a rule that is not a default and hence cannot be defeated by other rules.Footnote 16 The default logic underlying this system has no problem allowing such rules. The trouble is that such rules bring us all the way back to the problems of exceptions that we discussed at the start.Footnote 17

A better approach is to use the weight of R p3 to establish a weight for the hypothetical reasons, for courts do on occasion weigh hypothetical reasons.Footnote 18 The Lemon test is formulated such that failure on any prong is sufficient for a statute to be unconstitutional. “Sufficient” must be understood contextually here, because the rules which compose the test are defaults and hence can be defeated even if triggered. How should we then understand “sufficient” in this context? The answer is that “sufficient” here means “sufficient given the opposing reasons.” That is, if \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) or R p2 obtained, either would be sufficient to defeat the pro-defendant reasons (reasons for finding the statute constitutional). Therefore, \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) and R p2 should be weighed such that they defeat all the pro-defendant reasons. This gives \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\), R p2 , and R p3 equal weight with respect to the pro-defendant reasons (although it is possible they get differing weights in future cases) which comports with the treatment of each prong of the test as equally important.Footnote 19

This approach using hypothetical reasons with their weight established by the actual reason seems to resolve most of the difficulties in representing the Lemon Test. However the coarse-grain characterization of the reasons in each rule highlights a remaining objection. We seem to miss a great deal of the precedential import of the case with this characterization. The interesting and important question, the objection goes, seems to be what constitutes a statute’s having a secular legislative purpose, or having a primary effect of advancing or inhibiting religion, or creating an excessive entanglement between the government and religion. Our present theory by-passes all these issues as it begins with the presence or absence of these reasons already determined. The following section attempts to answer this objection.

4.2.3 A different kind of precedent? Rules that do not determine outcomes

The objection from the last section urges that we cannot ignore the step from a case to sets of opposing reasons. On this issue, Horty writes,

Of course, it must be noted also that the mere ability to understand a case in terms of the factors [i.e. reasons for one party or the other] it presents itself requires a significant degree of legal expertise, which is presupposed here. Our theory thus starts with cases to which we must imagine that this expertise has already been applied, so that they can be represented directly in terms of the factors involved; we are concerned here only with the subsequent reasoning. (2011, p. 5)

The theory starts with the case already converted into sets of reasons. It does not concern itself with this conversion. It is only concerned with only the second step of a two-step process: one going from facts to reasons (factors) and another going from reasons to outcomes.Footnote 20 The objection from last section suggests that precedent may play a role in the reasoning from facts to factors, and/or in reasoning from factors to other (more abstract) factors. It reminds us of the key insight in Branting (1991) that ratios involve not only reasoning with high level predicates (Branting’s terminology, these would be “abstract factors” in CATO) but also the reasoning that led the court to conclude that the high level predicates applied (that the abstract factors are present). CATO’s (Aleven 1997) hierarchy of factors, IBP’s (Bruninghaus and Ashley 2003) hierarchy of factors and issues, and the similar structure found in Roth’s (Roth 2003), address this point as well, though in a less rule based fashion. I will discuss the difference between these theories and my own in the next section. I first must explain my own view.

At this point it is important to make clear what my theory (and the HB-C theory it improves upon) purports to accomplish. It is not a complete theory of judicial reasoning. It does not purport to exhaust the many ways in which past cases may influence current judges. It is an attempt to explain the constraining force of precedent in judicial reasoning. Even past cases that are not relevant precedent may nonetheless be persuasive. They may not bind the current judge in any way, but nonetheless they influence how she decides the case. This influence might involve adopting the rule from a non-precedential case, but it need not. Instead, the past case may give the judge a helpful way of thinking about a problem, for example in terms of the costs imposed on rational actors. Or it may inspire her in more general ways. For example, recalling Justice Warren’s insistence that Brown v. Board of Education be a unanimous opinion may temper the judge’s tone in her own opinions (White 1987).

Additionally, past cases may influence how the judge proceeds from facts to reasons. Suppose she is hearing a nuisance action. She knows from past cases that a loud business operated close to a home is a reason favoring the homeowner. She knows the business is 15 feet from the home. But suppose she does not know whether that counts as “close” in a nuisance action. She is likely to review past cases to see what distances were previously counted as “close.” Suppose she finds a number of nuisance cases where businesses 15 feet from homes were deemed close.Footnote 21 This then influences her to treat the business in the current case as close to the home.

On the present theory this sort of influence is certainly permissible, but it is not precedential. To see this, note that the outcomes of the past cases the judge reviewed (and hence their rules) are irrelevant to her determination. The objection posed at the end of Sect. 4.2.2 and Branting (1991) essentially urge that this sort of influence be treated as precedential in at least some instances, such as the discussing in Lemon of the statutes’ secular legislative purpose.

To accommodate this within my theory I introduce two types of reasons: simple reasons and complex reasons.Footnote 22 Simple reasons are reasons that judges can readily (perhaps intuitively) discern such as “defendant killed the plaintiff,” “plaintiff signed the contract,” etc. These might be very thin reasons that fit tightly with facts, but they will still have a pro-defendant or pro-plaintiff polarity. Complex reasons are reasons that not readily apparent, such as, “the statute had a secular legislative purpose” (Lemon v. Kurtzman 1971, p. 625), “the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to a prurient interest in sex” (Miller v. California 1973, p. 15), “defendant was engaged in an inherently dangerous activity” [Restatement (Second) of Torts 1979, Section 520]. These are reasons that sit some distance from the bare facts of the case. I’ll call the first sort of reasons S-reasons and the second sort C-reasons. C-reasons will be denoted with an “R” and S-reasons will be denoted with an “R.” Mixed sets of reasons involving both sorts of rules are permitted and can be weighed just like any other set of reasons.

Sets of either sort of reason or a mixed set can serve as the antecedent of an outcome-determinative rule, i.e. a rule with a ruling favoring the plaintiff or defendant in the consequent. So outcome determinative rules can have any of the following forms (I only use the notation for pro-defendant rules, the conversion to pro-plaintiff rules is obvious):

-

Just S Reasons: {R d n ,…R d m } → D☺

-

Just C Reasons: {R d n ,…R d m } → D☺

-

Mixed Reasons: {R d n , R d n ,…R d m , R d m } → D☺

In addition to the familiar outcome-determinative rules, we introduce a new class of rules that go from a set of S-reasons to a set (likely a singleton) of C-reasons. Call these S-rules. They have the following form (again the conversion to pro-plaintiff is obvious):

-

S-Rule: {R d n ,…R d m } → R d n

Past cases are now composed of (1) a set of S-reasons, (2) a set of C-reasons, (3) a set of all reasons (both S- and C-reasons) favoring one party, (4) a set of all reasons favoring the other party, (5) a set of S-rules, and (6) a set of outcome determinative rules.

The theory explains how a judge decides a case as follows. First, he establishes the S-reasons present in the case. This process remains untheorized and it may be influenced by the content of the S-rules and outcome determinative rules from the past cases.Footnote 23 He then applies any S-rules from past precedential cases, yielding C-reasons. He then determines whether any other C-reasons are present in the case. This process is also untheorized. With all the reasons present in the case established, he applies any applicable outcome-determinative rules. The application of outcome determinative rules proceeds exactly as before, because all sets of reasons, regardless of the sort of reasons they contain, are weighed on a metric established from past cases.

The only troublesome step is the application of the S-rules. If they are to actually bind judges in some future cases, then they must be placed on some metric that establishes when they must be applied. The metric that establishing the weight of the sets of opposing reasons in a case will not work, because not all the opposing reasons will be involved in the determination of the presence of a C-reason. Consider Lemon again; the reasons involved in the determination of excessive entanglement are not identical with the reasons involved in the determination of secular legislative purpose. How could they be, if those two prongs are to be independent?Footnote 24 Further, pro-defendant reasons prevail on secular purpose but pro-plaintiff reasons prevail on excessive entanglement.

The solution is to create metrics indexed to each C-reason. Suppose a past case has only one C-reason. As part of the extraction of S-rules we now produce the S-reasons for and against the C-reason. Whatever party the C-reason favors, there will be S-reasons favoring that C-reason and hence that party. We could stipulate that S-reasons opposing that C-reason are reasons for the other party, but I worry that may let to undesirable results. My more cautious approach is to introduce a negation operator for reasons (¬) so ¬R p n means R p n does not obtain and likewise for ¬R d n . We allow S-reasons to support either a C-reason of the same polarity, or the negation of a C-reason of the opposite polarity. Thus the following sort of S-rule is permitted:

-

S-Rule’: {R d n ,…R d m } → ¬R p n .

The court’s determination of the presence of the C-reason or its negation establishes a weighing between the competing sets of S-reasons and this weighing is binding.

I will illustrate using the now familiar Lemon Test. The second prong was ignored by the court, so no changes are made to it here. The first prong of secular legislative purpose and the third prong of excessive entanglement are where this approach makes a difference. Let \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) be the absence of secular purpose. Let {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\),…R p n } be the set of simple reasons favoring a finding that there is no secular purpose found in the court’s discussion in Lemon. Let {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\),…R d m } be the set of simple reasons favoring a finding that there is a secular legislative purpose, i.e. in favor of ¬\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\), again from the court’s discussion in Lemon. Since the court ruled for the defendant on this issue, the first prong creates the following rule:

-

Prong 1 S-Rule: {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\),…R d m } → ¬\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\)

Further, it generates the following weighing of reasons: {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\),…R d m } > {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\),… R p n }. Should a case come up where \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) is at issue and {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{d}}\),…R d m } and {\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\),… R p n } exhaust the sets of relevant reasons, the judge is bound to hold that \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) does not obtain.

The third prong will have an S-Rule as well, for what constitutes an excessive entanglement of government and religion. Let R p3 stand for the presence of excessive entanglement, {R’ p1 ,…R’ p n } be the set of simple reasons favoring a finding that there is excessive entanglement in Lemon, and {R’ d1 ,…R’ d m } be the set of opposing simple reasons. We then get the following rule:

-

Prong 3 S-Rule: {R’ p1 ,…R’ p m } → R p3

Further, we get the following weighing of reasons: {R’ p1 ,…R’ p m } > {R’ d1 ,… R’ d n }. These S-rules thus allow for the construction of a precedential doctrine regarding what counts as a secular legislative purpose or an excessive entanglement of government and religion. In general, S-Rules can represent the development of a precedential doctrine regarding what constitutes other C-Reasons, such as what constitutes an inherently dangerous activity.

Another illustration without the triple-prong structure of Lemon will be helpful. In Terry v. Ohio (1968), the Supreme Court held that a police officer may perform a “reasonable search for weapons” if he reasonably believed that “he is dealing with an armed and dangerous individual” (1968, p. 27). I what follows I assume the defendant is the suspect. Letting R p1 be a reasonable search for weapons and R p2 be plaintiff believed defendant was armed and dangerous at the time of the search, we can cast the rule as follows:

-

Terry Rule: [R p1 , R p2 ] → P☺.

Subsequent cases applying the Terry Rule fleshed out what constituted “a reasonable search” and a reasonable belief that the individual is armed and dangerous.Footnote 25 These cases entrench the Terry Rule, but also introduce S-Rules that establish settings in which later courts must find that R p1 and R p2 obtain. For example, Pennsylvania v. Mimms (1977) states “the bulge in the jacket permitted the officer to conclude that Mimms was armed and thus posed a serious and present danger to the safety of the officer” (1977, p. 112). This can be captured by the following rule, where \({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\) is the presence of a visible bulge in the defendant’s jacket and R p2 is as before,

-

Mimms Rule: [\({\text{R}}_{1}^{\text{p}}\)] → R p2 .

Rules like this can then represent the doctrine built up around the Terry Rule.

5 My approach compared to previous theories

My approach differs from other theories in a variety of ways. Like the HB-C theory, my theory is rule based. This differentiates the approach from HYPO, CATO, and Roth (2003). My approach, like the HB-C theory allows for rules to become entrenched via their application in multiple cases. Further, my and allows rules which take a proper subset of the reasons favoring the side found in the rule’s consequent. This allows my account to go “beyond” a fortiori reasoning, which is unsurprising given that this motivated the account upon which mine is built (Horty and Bench-Capon 2012, pp. 183–186). This differentiates the approach from that of Prakken and Sartor (1998), and Horty (2004), although Branting (1993) has a similar insight. On these a fortiori theories, a rule of precedent favoring one party only constrains a judge when the current case has at most the same reasons for the other party and at least the same reasons for the favored party. On my theory, for example, the judge is bound by a pro-plaintiff case when the current case has at most the same reasons for the defendant and has the reasons for the plaintiff found in the antecedent of the rule from the past case.Footnote 26 Since the reasons in the antecedent need not encompass all the pro-plaintiff reasons in the past case, this means that my theory holds that the judge is bound in at least as many cases as the a fortiori theories, and likely more. This expands the scope of the constraining force of precedent.

The HB-C theory and my own would become a fortiori theories if they included a requirement that the rules from a past case include all the reasons in favor of the prevailing side. Although that difference may seem slight, it is important to the maintenance of a meaningful distinction between ratio and dicta. That distinction requires that some of the opinion be inessential to its force as precedent, but a fortiori approaches treats precedent as involving all the reasons for each party involved in the case. Thus, it is hard to see what is left in the opinion to play the role of dicta. Note that dicta is not meaningless or irrelevant, since it may be persuasive, but simply inessential to decide the case.Footnote 27 Further, and unsurprisingly, given its methodology, case based systems are not amenable to entrenching rules through multiple cases.

My theory shares similarities with Branting (1993), which involved a series of warrants (rules) from facts to higher and higher order factors until we reach a factor that resolved the case. Only the rules invoked in this chain are the ratio, the rest of opinion is dicta. However, Branting does not offer a way of determining when these rules are binding and when they may be distinguished by a judge. Indeed, there is no representation at all of the reasons opposing a particular conclusion in the chain of warrants that constitutes the ratio. My account and the HB-C theory offer an explanation of when precedent may be distinguished and when it constrains.

The aspects of my theory that deal with framework cases parallel much work in the case-based tradition, such as CATO’s factor hierarchy (Aleven 1997), Roth’s approach (Roth 2003), and IBP (Bruninghaus and Ashley 2003), as well as the rule-based work of Atkinson et al. (2013). I treat each of these in the following sub-sections.

5.1 CATO and Roth’s approach

I should say a bit more about how my theory differs from CATO and Roth’s theory beyond just its focus on rules. CATO and Roth’s approach make use intermediate factors and the relationship between these and higher-order factors. My S-Reasons are analogous to intermediate factors, while my C-Reasons are analogous to higher-order factors.

However, the view Aleven’s CATO and Roth’s theory give of precedent is more fine-grained than mine regarding the application of precedent to fact finding, as my approach more strongly parallels IBP. One can think of judicial determinations as spanning a spectrum from purely factual determinations (answers to “questions of fact”) to purely legal determinations (answers to “questions of law”). On the factual end are the determinations that a jury could be tasked with making, while the legal end is the sole providence of the judge. The distinction is of great importance given my concern for the constraining force of precedent. Determinations of fact are typically not subject to binding precedent. Indeed, juries are not presented with past case law at all. They are neither bound by nor able to create precedent (Weiner 1966, p. 1887). Approaches such as Roth (2003) seem to envision precedent as controlling more factual determinations as well, such as whether having punched a supervisor constitutes a serious act of violence (2003, Section 3.6.4).Footnote 28 I envision the complex reasons that my S-Rules flesh out as falling on the legal side of the spectrum, though not at the very end.

The distinction between S/C-Reasons and intermediate/high level factors is thus a matter of degree. But there is an overlooked and quite vexing issue regarding the distinction between matters of fact and matters of law that merits discussion. Rules establishing the presence of a C-Reason or high level factor must be judicially established, since the jury cannot create precedent. This means that at least some cases will have to be interpreted as involving only a rule going from a set of C-Reasons to the outcome, without the subsidiary rules which led to the establishment of the C-reason. Further, this can be required even when there is a precedential rule governing the establishment of the relevant C-Reason, as the following example illustrates.

Consider the question of negligence in accident tort cases and the corresponding factor of the defendant’s negligence, call it “Defneg.” On the one hand, Defneg looks like a higher-order factor, requiring a determination of what precautions would have been reasonable. Sometimes, when the defendant is negligent as a matter of law Defneg can be established by precedent. That is, “that the jury will also be prevented from deciding whether given conduct is negligent if appellate case law establishes how a reasonably prudent man would act under the very circumstances in question” (Weiner 1966, p. 1883). Such rules must, on my theory, be expressed as S-Rules, going from a set of factors favoring Defneg to the conclusion of Defneg. These are not, strictly speaking, rules of precedent governing the jury. Rather, they are rules that require the judge to prevent the jury from making a determination regarding negligence in certain cases.

However, courts are increasingly hesitant to take the issue of due care away from juries (Weiner 1966, p. 1886). Hence, “[e]ven when the historical facts are undisputed, the jury rather than the judge will normally decide whether they will be characterized as negligent” (Weiner 1966, pp. 1876–1877). Thus, in many cases none of the few S-Rules for Defneg will apply. In these cases the jury will determine whether Defneg obtains. But we ought not derive any S-Rules from these jury cases. Instead, we should only derive an outcome determinative rule involving the C-Reason Defneg (and whatever other C-Reasons are relevant) and the result of the case. To meet these requirements, we must implement a control preventing S-Rules from being extracted from certain cases involving C-Reasons. Put into CATO’s terminology, there are cases where we must ignore intermediate factors when expressing the ratio.Footnote 29 At present I have no suggestions on how to construct such a control.

5.2 Atkinson et al.’s theory (ASPIC +)

The work of Atkinson et al. (2013) offers a further point of comparison. That theory is rule based, contra CATO and Roth’s view, and its novelty lies in its focuses on the bottom level of the factor hierarchy, on the inference from bare facts to factors. The idea is that we begin with dimensions, each of which is an ordering of facts (not factors) relevant to the legal issue identified by the respective dimension. The ordering places the most pro-defendant on one end and the most pro-plaintiff on the other. For example, the dimension of “pursuit [of the animal]” was one relevant dimension of the famed Pierson v. Post decision and along that dimension one finds facts for full possession of the animal, inevitable capture of the animal, pursuit which had already wounded the animal, hot pursuit of the animal, pursuit just beginning, mere sight of the animal, and no pursuit at all (Atkinson et al. 2013). Given one of these facts, the parties will dispute whether that fact is sufficient evidence for the factor regarding whether the animal was caught (or not caught) (Atkinson et al. 2013). The theory allows for a method of expressing this dispute using default rules taken from various authorities.

Unsurprisingly, I do not adopt such a fine-grained approach to precedent because I think that these rules govern matters of fact and hence are not constraining precedent in common law systems. The theory of Atkinson et al. may capture essential elements of the persuasive force of precedent but I am not convinced that such low level inferences are essential to capture the constraining force of precedent, i.e. the ratio of a case. Essentially, I think the Atkinson et al. approach is too fine-grained to capture the notion of a binding ratio.

This raises a difficult jurisprudential question regarding the right level of granularity or abstraction with which to express the ratio. If the ratio is too abstract, for example, “if defendant was unjustly enriched, then rule for the plaintiff,” then it will not offer much constraint because it is too difficult to know when it is triggered. Yet, if it is not abstract enough, then it will not offer much constraint because it is too seldom triggered. Approaches like Branting’s (1991) and Atkinson et al’s (2013) catalog rules for nearly every conclusion reached in an opinion, making cases generate some abstract rules and many detailed one. All of these rules are then treated as part of the ratio. I have argued that only some of these rules are genuine precedents (ratios), but I have at present no explanation of which ones these are. I do, however, suggest that this difficulty is a jurisprudential one inherit in the concept of a ratio and not a flaw particular to my theory.

One might object to my failure to specify and justify an appropriate degree of granularity for ratios. I admit that my account would be better if I had. Nonetheless, I do not think this objection is fatal. After all, the alternative theories face it as well. For example, consider the Atkinson et al. theory. The authors are certainly right to note that legal parties often argue about the inferences from facts to factors. But they give no principled reason to stop there.Footnote 30 Parties also very often argue about the inferences from evidence, which is composed of facts about who said what, the results of laboratory testing and so on, to facts. So why not model these disputes too? A dispute about whether a piece of evidence is admissible for a particular purpose is a matter of law governed by precedent but the inferences made from admitted evidence are clearly not so governed. For example, there can be no precedent, persuasive or constraining, that directs a judge (or jury) to believe one witness over another. The reasoning in these inferences is certainly important to the result in the case; in criminal cases these inferences are often dispositive. But I doubt they are a distinctively legal form of reasoning as opposed to the everyday reasoning people use to make inferences from evidence.Footnote 31 Everyday reasoning is not governed by precedent and therefore is beyond the purview of a theory concerned with modeling precedential reasoning.

Some level of common sense reasoning is needed before legal reasoning can occur and the further one moves down a hierarchy of factors (or factors and facts) the closer one gets to the common-sense reasoning. Every theory of legal reasoning (as opposed to a complete theory of human reasoning) must draw a line somewhere separating the two types of reasoning. Determining just where this line ought to be drawn is an important and still unresolved question, despite receiving significant jurisprudential reflection, see (Alchourron 1996; Dworkin 1986; Goodhart 1930; Kelsen 1967; Schauer 2012; Simpson 1961).Footnote 32 It is important for theorists in AI and Law to be sensitive to this difficulty, but we can be forgiven (I hope!) if we do not solve it.

5.3 IBP

Brüninghaus and Ashley’s IBP comes closest to my own approach to framework cases. IBP divides cases into issues, which are then related truth functionally, i.e. non-defeasibly, with one another. The top issue resolves the case for the plaintiff or the defendant. The top issue is then split into necessary and/or sufficient sub-issues, which may have further sub-issues. For example, consider the domain of trade secret litigation for which IBP was designed. The top issue is whether a trade secret was misappropriated. If this issue is present, then the case must be decided for the plaintiff. This issue has two necessary conditions which are together a sufficient condition: (1) that the info was a trade secret, and (2) that the info was misappropriated. (1) and (2) have further necessary and jointly sufficient conditions which are their sub-issues. Within this logical framework, IBP uses case based reasoning involving factors that favor or oppose the lowest sub-issues. These factors are only the higher level ones as IBP “does not have CATO’s Factor Hierarchy’s detailed representation of intermediate level issues” (Bruninghaus and Ashley 2003, p. 236). IBP determines the strength of the factors using a case based system that searches for cases similar with respect to the pertinent issue. The strength of the relevant factors resolve these sub-issues, while sub-issues for which the case contains no relevant factors are ignored. The system then works up from the sub-issues to resolve the case. If a set of sub-issues sufficient for the top issue of trade secret misappropriation are resolved for the plaintiff (or ignored) then IBP predicts he will prevail. If any sub-issue necessary for the top issue is resolved for the defendant, then IBP predicts the defendant will prevail.

My theory and IBP differ, of course, in the use of case-based instead of rule based procedures for determining whether a sub-issue obtains. However, both approaches allow cases to be divided into units with their own relevant factors—my C-Reasons with S-Rules and S-Reasons and IBP’s sub-issues with factors. Further, both theories focus on high-level factors, contrary to the approaches found in Roth, CATO, and Atkinson et al.. These parallels and some remarks from Horty and Bench-Capon, discussed below, suggest an alternative to my theory’s approach to framework.

Horty and Bench-Capon write that their theory is supposed to apply only to stable periods within legal history and not to landmark cases which redefine the field (Horty and Bench-Capon 2012, p. 207). My exemplar framework case, Lemon, is thought by Kritzer and Richards (2003) to mark the beginning of an empirically measurable, distinct epoch in how the Supreme Court decided Establishment Clause cases. Thus, it might appear that the HB-C should not be modified to accommodate framework cases. Instead, we might follow the insight of IBP and treat framework cases as establishing the (truth functionally related) issues that future cases in this area must address. Given the issue structure imposed by framework cases, we then apply the HB-C theory to each issues. Essentially, the HB-C theory takes the place of IBP’s case-based reasoning module.

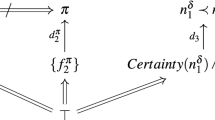

For example, consider the three prongs of the Lemon test. We can relate them as issues in the way shown in Fig. 1. For each of the lowest level issues there will be reasons and rules, corresponding to my S-Reasons and S-Rules, which interact in the typical HB-C manner. The issues are related via disjunction to the upper most issue of Establishment Clause Violation, which disposes of the case in favor of the plaintiff. There is no need to assign weight to the various prongs because each is simply sufficient to yield the top-most issue.Footnote 33

This proposal has the virtue of treating reasons as all falling within a single type. Since the C-Reasons in my treatment of Lemon are now issues, we no longer need a distinction between S and C-Reasons. Treating the C-Reasons as issues in effect turns my defeasible C-Rules from Lemon into strict rules. Given a finding that one of the sub-issues, such as excessive entanglement, obtains, the pro-plaintiff result (establishment clause violation) must follow.

I must acknowledge that this proposal strikes me as quite a good one, and a significant improvement upon the HB-C theory. However, let me offer a (perhaps unconvincing) defense of my approach. There appear to be instances in which the C-Rules from Lemon admit of exception, which is to say that they seem to be defeasible rather than strict. Though it purports to be a general test for establishment clause violations, in some circumstances the Supreme Court applies alternative tests. For example, in Cutter v. Wilkinson the Supreme Court acknowledged that the Lemon test was relied upon by the lower courts in find the relevant legislation unconstitutional and then found the legislation constitutional “on other grounds,” without overturning Lemon (2005, p. 718, n. 6). Similarly, the Supreme Court acknowledge the Lemon test relied upon by lower level courts but applied a different test focused on coercion in the school-prayer-case of Lee v. Weisman (1992, p. 586–589). Additionally, in Kiryas Joe the Supreme acknowledged the application of the Lemon test by the lower courts but decided the case using a test focused on the neutrality of the government action toward different religions (1994, pp. 695, 702–705).

These case show that parties (and Justices) will dispute the applicability of the Lemon Test to the case at hand. The results in these cases identify sets of reasons to which the Lemon Test has been deemed inapplicable, i.e. exceptions to the test. Using defeasible rules to construct the framework allows my theory to capture these exceptions. On the IBP view, these would be arguments about the appropriate structure of issues to be applied to the case. IBP has no way of representing the outcomes of such arguments, except by manually introducing a new issue structure for each new exception. Essentially IBP would treat each of the aforementioned cases as a landmark framework case, which seems contrary to their general interpretation.Footnote 34 My approach treats them as genuine exceptions.

6 Conclusion

I have argued that rule-based approaches best capture the distinction between ratio and dicta. This distinction is essential for modeling the constraining force of precedent, which compels judges to decide cases certain ways, because the ratio is the rule that constrains later judges. I understand the HB-C theory to be the best theory of ratios in AI and Law. I tried to improve the HB-C theory to account for overdetermined cases and framework cases. To account for overdetermined cases, I allowed the theory to extract multiple ratios from single case. To account for framework cases, I allowed the theory to extract rules which were not triggered in the case, that is, those involving hypothetical reasons, and to give those hypothetical reasons a weight. Further, framework cases required introducing a two-tiered hierarchy of reasons (and corresponding rules). This let us express the framework rule using the more abstract reasons (C-Reasons) while also treating as precedent rules regarding when future courts can infer the presence of these abstract reasons from some less abstract reasons (S-Reasons).

Both sorts of cases put pressure on the distinction between ratio and dicta. Acknowledging that cases can contain multiple rules sufficient to resolve the matter entails that some parts of the opinion which were strictly speaking “inessential” to the result are nonetheless ratio rather than dicta. The framework cases required extracting rules which were not triggered in the case. Since these rules are not even triggered in the case, they seem like obvious dicta. Yet their treatment by practicing lawyers and the legal academy suggests they are ratios.

Expanding the notion of ratio in this way effaces the distinction between ratio decidendi and obiter dicta. As discussed in Sect. 2, the more this distinction is effaced, the weaker the case is for adopting a rule based, nonmonotonic theory. Thus I am attempting something of a balancing act by accommodating the expansive notion of ratios found in framework and overdetermined case while also trying to maintain some clear demarcation between ratio and dicta.

The two-tiered hierarchy of reasons attempts a similar tight-rope walk. On the one hand, fine grain rules seem to govern matters of fact, not law. This favors a hierarchy with few, if any, tiers. On the other hand, coarse grain rules will not control or even greatly influence future cases. This favors a hierarchy with many tiers to model rules that govern every step in judicial decision making. These concerns are bound up with difficult jurisprudential questions regarding the extent of judicial discretion, the proper formulation of ratios, and the distinction between law and fact. I have only faintly gestured at answers to these questions in the course of opting for a two-tier hierarchy.

Despite these flaws, the article offers a theory of some importance. If one shares my intuitions on the jurisprudential issues, and I suspect some will, then the theory bests the alternatives. If one disagrees with these intuitions, I still think the theory illustrates how jurisprudential disagreement manifests itself in theories of legal reasoning. For example, if you believe in a sharp distinction between ratio and dicta, then you may want a theory with only highly abstract ratios, like HB-C, instead of something case based. If you believe ratios reach down into the fine details of judicial decisions, then you may want a theory with a many-tier hierarchy of reasons or factors. Identifying how different views of jurisprudence effect theories of legal reasoning is itself an important task that this article helps accomplish.

Notes

There is a controversy in legal philosophy regarding the possibility and nature of precedential constraint, see (Alexander and Sherwin 2008; Schauer 2008). In that realm I have argued that precedential constraint is possible and its nature is best understood through the prioritized defaults of (Horty and Bench-Capon 2012) in my (2014b).

More specifically, the notions of ratio and dicta favor an approach that extracts a rule or rules from an individual case, as the definitions in the text make clear.

In earlier formulations, such as Horty (2004), the antecedent of the rule was the set of all reasons for the prevailing party. The more recent and improved version allows the antecedent of the rule to be a proper subset of the reasons for the prevailing party, allowing the improved theory to go beyond a fortiori reasoning. The determination of which reasons compose the antecedent is part of the process of extracting a rule from a case. That process is independent of the theory.

I ignore the subtleties of contract law remedies in these examples for ease of exposition.

Notice that she can distinguish on the basis that R d2 combined with R d1 tilts the scale toward the defendant, which yields Rule2. She could also distinguish on the basis that R d2 is so potent that it alone outweighs R p1 . This would yield a different rule, namely, {R d2 } → D☺. The weighing introduced by the second option is {R d2 } > {R p1 }. The first approach is thus a more cautious method of distinguishing.

Some have argued against this theory on the grounds that there are always novel sets of reasons for both parties in each case. See (Rigoni 2014a) for a response. There are also questions about aggregating relative weights. For example the > relation is not transitive, so it does not follow from R d1 > R p1 , R p2 > R d1 , and R p1 > R d2 , that R p2 > R d2 . These issues are discussed in (Horty and Bench-Capon 2012, p. 199; Horty 2011, p. 17; Rigoni 2014b, Chapter 3).

R d3 is highly simplified, as equitable holdings typically involve weighing a number of facts. For simplification I compress all the pro-defendant reasons with respect to equitable indemnity into one reason.

For example, Kritzer and Richards (2003) argue that Lemon marked the beginning of an empirically measurable, distinct epoch in how the Supreme Court decided establishment-clause cases.

One might object that this and the following examples use too coarse-grained a characterization of the relevant reasons. Instead, the objection goes, we should adopt an approach that individuates facts that lead to the conclusion that there is a secular legislative purpose. I address this issue later in this section.

For explanation see (School Dist.of Abington Twp., Pa. v. Schempp 1963, p. 223–225).

It also raises the question of why not take the Walz citation seriously as well and then just make Lemon an entrenchment of that rule. But I am ignoring that question here. See supra at Sect. 4.2.

Once this is adopted, R p n and R d n will no longer represent reasons that obtain in the case. Instead, they will represent potential reasons. This is unproblematic since the theory assumes that the reasoner has already determined the sets of obtaining pro-plaintiff and pro-defendant reasons that obtain independently of her determination of the rules in the case. I refer to these potential reasons simply as “reasons” in what follows.

Rule3 imposes the familiar weighing where R p3 outweighs all the pro-defendant reasons present in Lemon.

This is basically the approach taken by the IBP + HB-C hybrid approach discussed in Sect. 5.3.

See infra, Sect. 5.3 for a discussion of exceptions to the Lemon rules.

See, for example, Marshall's dissent in Stencel Aero Eng’g Corp v. U.S. (1977).

One could go further and stipulate that the three prongs always have equal weight. I do not explore this possibility.

There is another issue lurking here, which I ignore in this chapter, namely, what if the past cases involve businesses that are between 20 and 30 feet from the respective homes? How do would we get from that to a conclusion about businesses 15 feet from homes? See (Rigoni 2014a) for further discussion.

I use this strategy because, as will be seen, it prevents S-rules from chaining. It might be best to allow S-Rules to chain, but I adopt the most conservative possible strategy here. I discuss loosening the reins in my (2014b, Chapter 3).

I am here thinking of instances where a past case causes one to notice a previously unnoticed reason, not anything involving the application of the rules.