Abstract

Drawing on the proactive motivation model, this study aims to investigate how entrepreneurial leadership at the organizational level influences employees’ taking charge at the individual level, as mediated by thriving at work and moderated by employees’ autonomy orientation. Through a two-wave questionnaire survey of 356 employees from high-tech enterprises in China, this study uses multilevel structural equation modeling to test the proposed hypotheses. The results show that organizational entrepreneurial leadership has a positive impact on individual employee taking charge and thriving at work partially mediates this relationship across levels. Additionally, employees’ autonomy orientation positively moderates not only the effect of thriving at work on employees’ taking charge but also the mediation of thriving at work in the aforementioned relationship. This study advances knowledge about entrepreneurial leadership stimulating employees’ intrinsic motivation to drive their taking charge. The psychological perspective and cross-level process deepen the research on entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness and employees’ proactive behavior, and further provide empirical evidence for executives to prompt employees to take charge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Confronted with the accelerated progression of advanced technology and the high uncertainty in the business environment, enterprises have to explore and seize market opportunities in response to environmental dynamics (Duarte Alonso et al., 2023). This imperative has prompted enterprises to focus more on the subjective initiative and change ability of their workforce, so they require employees to observe opportunities and challenges at work and proactively transform work patterns to enhance organizational adaptability and creativity (Albrecht et al., 2020). Employees’ taking charge refers to their change-oriented, spontaneous and constructive efforts to improve the way individuals, teams or organizations work and optimize organizational functions (Morrison & Phelps, 1999). Such behavior goes beyond employees’ own work with self-initiative, which contributes to organizational competitiveness and high-quality development in the uncertain environment (Ren et al., 2023). To this end, it has become the focus of managers to make employees willing to take charge so that the management mode alters from supervised command by leaders to autonomous change by employees. As a typically proactive extra-role behavior, however, taking charge is challenging and risky. Especially considering interrelationships and avoiding conflicts, employees may prefer in-role tasks to maintain the status quo rather than taking charge (Zhang et al., 2021). Therefore, in the current uncertain context of entrepreneurship and innovation, it is particularly important to explore a leadership style that can support employees’ adventure and change to enable them to take charge.

Research has recognized the significance of organizational leadership as the driver to motivate employees’ taking charge, since scholarship identified the influence of various leadership styles on this behavior such as transformational leadership, empowering leadership, inclusive leadership, authentic leadership and benevolent leadership (Du & Yan, 2022; Kim et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018). Entrepreneurial leadership, as an emerging leadership under the background of entrepreneurship and innovation, is characterized by adventure and reform, where the leader guides followers to develop entrepreneurial opportunities, take innovative actions and create business value to adapt to the dynamic environment (Lingo, 2020; Renko et al., 2015). While employees’ taking charge involves changing work procedures or business patterns and challenging the status quo with certain risk, which depends largely on the support from organizational leadership (Burnett et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2022). In this vein, entrepreneurial leadership helps to trigger employees’ taking charge because such leadership can lead organizational members to explore potential opportunities, optimize organizational processes and transform business models to cope with environmental uncertainty and achieve enterprise growth (Koryak et al., 2015; Simba & Thai, 2019). In other words, entrepreneurial leadership is likely to be particularly effective for employees’ taking charge in the current context. Nevertheless, little research pays attention to the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge and investigates its underlying mechanisms. To address these gaps, this study attempts to discuss why and how organizational entrepreneurial leadership affects individual employee taking charge.

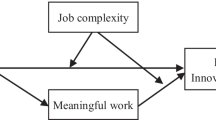

The proactive motivation model can be used to elucidate the mechanisms where entrepreneurial leadership influences employees’ taking charge. As previously mentioned, employees’ taking charge is a proactive behavior driven by intrinsic motivation, which is mainly impacted by organizational leadership and individual internal elements. According to the proactive motivation model, leadership is a major stimulus of employees’ proactive behavior and individuals need to have strong intrinsic motivation to take charge beyond their own work (Parker et al., 2010). While good mental state of employees can positively predict individual work behavior (Luthans et al., 2016). Thriving at work reflects employees’ mental state of great vitality and active learning at work, which enables them to experience continuous progress and self-realization so that they have strong internal incentives to spontaneously and actively engage in reform activities (Spreitzer et al., 2005). Under the guidance of entrepreneurial leadership, employees are sensitive to the leader’s performance expectations and risk-taking and innovative spirit, thereby arousing their work vitality and learning enthusiasm. Thriving at work stimulates employees to take charge, where they embrace challenges or uncertainties, create novel solutions and enact change. Thus, this study takes thriving at work as a mediator to discuss the psychological mechanism of entrepreneurial leadership affecting employees’ taking charge. Besides, the proactive motivation model points out that individual trait differences would strengthen or weaken the impact of leadership on employees’ proactive behavior (Parker et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2018). As an important personality trait, employees’ autonomy orientation can explain the differences of individual proactive behavior to some extent. Highly autonomy-oriented employees are inclined to challenges, innovation and proactive work driven by intrinsic motivation (Liu & Fu, 2011). Accordingly, employees with different degrees of autonomy orientation may differ apparently in their responses to entrepreneurial leadership, feelings of thriving at work and actions of taking charge. Hence, this study takes employees’ autonomy orientation as a moderator to examine the boundary condition of entrepreneurial leadership affecting employees’ taking charge. Taken together, based on the proactive motivation model, this study explores how entrepreneurial leadership at the organizational level mobilizes thriving at work of individual employees to boost their taking charge, as well as the role of employees’ autonomy orientation in this process (see Fig. 1), in order to reveal the cross-level impact of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ taking charge from the psychological perspective.

This study makes several contributions. First, it broadens the research on entrepreneurial leadership and taking charge by theorizing and demonstrating the relationship between the two. Despite the literature linking certain types of leadership to employees’ taking charge (e.g. Du & Yan, 2022; Wang et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2021), research has yet to investigate the effect of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ taking charge. This study examines the role of entrepreneurial leadership in driving employees to take charge, so it can contribute to the research area of entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness and employees’ proactive behavior. Second, it provides valuable insights into the black box of how entrepreneurial leadership impacts employees’ taking charge by focusing on individual intrinsic motivation. This study utilizes the proactive motivation model to illuminate the mediation of thriving at work in such linkage, which advances the understanding about how to transfer the influence of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ taking charge. Third, it reveals the contingency factor that causes the differentiated strength of the above relationship in terms of individual personality traits. This study looks into the moderating effect of employees’ autonomy orientation as an important boundary condition that can exacerbate or mitigate the role of entrepreneurial leadership in employees’ taking charge. In doing so, it interprets that entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness toward employees’ taking charge is contingent upon the degree of employees’ autonomy orientation within their work. Fourth, it increases the robustness of the linkage between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge via the analytical method. Given that extant empirical studies on entrepreneurial leadership and taking charge primarily rely on single-level analysis (e.g. Kim et al., 2023; Li et al., 2020; Pu et al., 2022), this study collects multilevel data and adopts cross-level analysis for nuanced findings about the association of entrepreneurial leadership at the organizational level with employees’ taking charge at the individual level. Also, this study offers some enlightenment for executives to play entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness and lead staff to achieve organizational change and innovation.

Theory and hypotheses

Entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge

Entrepreneurial leadership is defined as leadership that creates organizational vision to gain recognition and support from subordinates and then encourages them to explore strategic value creation (Gupta et al., 2004). Through identifying and exploiting opportunities, this leadership helps organizations respond to the dynamic and competitive business environment (Hussain & Li, 2022). Employees’ taking charge is a proactive behavior voluntarily taken by employees to optimize organizational functions and processes beyond their general roles, which is forward-looking, challenging and change-oriented (Kumar et al., 2022). The proactive motivation model holds that leadership would influence an individual’s proactive motivation and behavior (Parker et al., 2010). Entrepreneurial leadership outlines a bright development prospect to inspire organizational recognition for entrepreneurial goals. To seize entrepreneurial opportunities, it timely observes environmental dynamics and fully integrates resources to lead followers’ constant reform and innovation (Bagheri, 2017; Iqbal et al., 2022). As such, entrepreneurial leadership can mobilize employees’ initiative to take charge so that they pursue improvement, transformation and creative solutions at work (Du & Yan, 2022).

According to the proactive motivation model, individuals perform proactive behavior driven by three motivations of capability, reason and energy. These motivations are derived from individual self-efficacy, internal causes and positive emotions, respectively, which prompt individuals to take charge (Parker et al., 2010). Burnett et al. (2015) pointed out that whether employees take charge mainly relies on organizational support. Entrepreneurial leadership at the organizational level entails five core competencies: framing challenges, absorbing uncertainty, clearing paths, building commitment and specifying limits (Gupta et al., 2004), which serve as the incentive and catalyst of employees’ intrinsic motivation and then have a beneficial impact on their taking charge.

Specifically, entrepreneurial leadership inspires employees’ entrepreneurial passion and innovative enthusiasm by establishing attractive organizational vision and commitment (Mehmood et al., 2020). Such positive emotions make individuals have a strong energy motivation to actively work for self-realization, thus triggering employees’ taking charge. Meanwhile, due to pursuing challenges and advocating innovation, entrepreneurial leadership creates a work environment that encourages reform, shares knowledge and tolerates failure via reasonable empowerment and risk taking, which elevates employees’ self-efficacy of innovation and entrepreneurship (Cai et al., 2019a, b; Wu et al., 2021). With the stimulation of capability motivation, employees are willing to identify and develop opportunities to create value for the organization. When personalized needs and creative attempts are supported by the organization, employees reduce their risk perception and negative expectations of behavioral consequences (Hirak et al., 2012), so that they have a powerful reason motivation to challenge the status quo and take the initiative to change. Moreover, entrepreneurial leadership clears effective paths of entrepreneurship and innovation and clarifies specific constraints of the organization, which can guide employees to organically integrate, reorganize and utilize various resources following organizational strategic development direction (Haim Faridian, 2023; Mehmood et al., 2019). The resulting capability motivation pushes employees to actively optimize workflows and ameliorate techniques to favor organizational strategic resource management. To sum up, entrepreneurial leadership can trigger the energy, capability and reason motivations of employees to take charge. Therefore, we predict the following hypothesis:

H1

Entrepreneurial leadership has a positive effect on employees’ taking charge.

The mediating role of thriving at work

Thriving at work is a psychological state where employees are energetic and actively learning at work. Vitality and learning are its two core elements, reflecting the emotional and cognitive aspects of employee growth. Vitality refers to individual enthusiasm, energy and ambition toward work, while learning refers to the acquisition of knowledge and skills at work to establish confidence and reinforce ability (Porath et al., 2012; Spreitzer et al., 2005). It can be seen that the two major elements of thriving at work are closely related to the energy and capability motivations involved in the proactive motivation model. Strong thriving at work may better activate employees’ initiative and boost their proactive behavior such as taking charge to get a higher sense of achievement (Alikaj et al., 2020). Paterson et al. (2014) argued that leadership support plays a crucial role in employees’ thriving at work.

The core competency manifestations of entrepreneurial leadership make employees perceive organizational encouragement and support for opportunity exploration and value creation (Supartha & Saraswaty, 2019), which motivates employees’ change vitality and learning intention and then augments their thriving at work. Specifically, the capabilities of framing challenges and building commitment enable staff to deeply understand organizational vision and performance expectations for entrepreneurship and innovation (Gupta et al., 2004). The ability to absorb uncertainty makes employees aware of organizational risk taking, which relieves their concerns about reform and prompts them to reshape work and implement novel ideas (Akbari et al., 2021). The competencies of clearing paths and specifying limits help subordinates clarify approaches and constraints of organizational transformation and then efficiently carry out corresponding activities (Huang et al., 2014). Hence, the positive and supportive atmosphere created by entrepreneurial leadership can arouse employees’ work passion, meet their independent needs and increase individual self-efficacy, which strengthens employees’ work vitality and learning orientation so that they experience thriving at work.

Thriving at work pushes employees to improve their work for personal growth (Spreitzer et al., 2005), which is likely to trigger their taking charge. This is because work vitality and learning orientation provide an endogenous driver for individual creative behavior (Paterson et al., 2014), employees would proactively discover problems, identify opportunities and challenge the status quo. Moreover, work vitality is conducive to individual positive emotions, while learning is useful to reduce work uncertainty (Wang et al., 2022). Consequently, thriving at work actives employees’ energy and capability motivations, makes them confident and brave to encounter challenges at work and then leads to their taking charge. As mentioned above, entrepreneurial leadership can create flexible and autonomous work circumstances where employees are self-determined, self-inspired and self-adjusted to keep their high work enthusiasm and learning desire (Sawaean & Ali, 2020), so it results in strong thriving at work of employees. Learning is a major way for individuals to facilitate self-efficacy (Bandura, 2012), which helps to stimulate the capability motivation of their proactive behavior. Through learning, employees continuously acquire knowledge required for reform and deepen their cognition of work significance and self-worth, thereby enhancing individual reason motivation to take the initiative to change (Parker et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2021). Therefore, according to the proactive motivation model, entrepreneurial leadership reinforces employees’ thriving at work to inspire their energy, capability and reason motivations of proactive behavior, further driving them to take charge. Taken together, we formulate this hypothesis:

H2

Thriving at work mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge.

The moderating role of employees’ autonomy orientation

Autonomy orientation is a type of causality orientation based on the differences in individual motivation orientation and autonomous support preference. Causality orientation emphasizes that the essential cause of individual behavior is a stable motivation orientation. On this basis, autonomy orientation refers to the tendency of individuals to adopt selective behavior because of their self-perception and value cognition, who with this salient trait have great self-determination and initiative consciousness (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Employees’ autonomy orientation is a persistent personality trait of employees, they are self-determined and driven by intrinsic motivation to choose highly autonomous work and seek opportunities for self-realization (Liu & Fu, 2011; Olesen et al., 2010).

According to the proactive motivation model, personality traits would affect individuals’ proactive motivation and behavior (Parker et al., 2010). As stated above, thriving at work can arouse employees’ proactive motivation and then boost their taking charge. Thereby, the differences of employees’ autonomy orientation may impact the effect of thriving at work on employees’ taking charge. Employees with high autonomy orientation have strong intrinsic motivation, independent awareness and innovative spirit, pay attention to ability improvement and engage in challenging or interesting activities (Gagne & Deci, 2005; Liu et al., 2011). When thriving at work, highly autonomy-oriented employees possess strong capability, energy and reason motivations to take charge. These employees actively perform and learn at work with a high level of autonomy orientation, so they have powerful self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. In this case, employees are confident of reform to change the status quo and realize personal value, thus inspiring them to take charge. In contrast, employees with low autonomy orientation tend to be conservative and maintain the status quo at work. Even if such employees encounter thriving at work, they are less likely to efficiently turn their work vitality and learning tendency into taking charge. Overall, high autonomy orientation of employees helps to strengthen the positive effect of thriving at work on employees’ taking charge. Hence, we expect the following hypothesis:

H3

Employees’ autonomy orientation moderates the relationship between thriving at work and employees’ taking charge, such that this positive relationship is stronger when employees’ autonomy orientation is high.

In addition, the proactive motivation model suggests that leadership as a vital organizational factor can activate employees’ intrinsic motivation to conduct proactive extra-role behavior and individual personality traits impact the role of leadership in such behavior (Parker et al., 2010). Accordingly, it can be argued that employees’ autonomy orientation may influence the process of entrepreneurial leadership affecting their taking charge via thriving at work. That is, the mediating effect of thriving at work in this process is moderated by employees’ autonomy orientation. Entrepreneurial leadership enables to set challenges, absorb uncertainty and exploit opportunities (Gupta et al., 2004; Renko et al., 2015). Influenced by these leadership demonstrations, organizational members are full of thriving at work and then proactively take change actions to break rigidity, optimize processes and improve organizational functions beyond their general roles (Yan et al., 2021). In this situation, employees with high autonomy orientation are more likely to arouse their proactive motivation to take charge. Therefore, we further propose a hypothesis:

H4

Employees’ autonomy orientation moderates the mediating effect of thriving at work on the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge, such that this mediating effect is stronger when employees’ autonomy orientation is high.

Method

Sample and procedure

Data was collected from high-tech enterprises located in Shanghai, Zhejiang and Jiangsu in the Yangtze River Delta of China. We chose this sample because of the vitality of entrepreneurship and innovation in the Yangtze River Delta and the strength of high-tech enterprises in technological innovation. Specifically, entrepreneurship and innovation in the Yangtze River Delta are the leading one in China with the support of national strategies and local policies, whereas high-tech enterprises become crucial entrepreneurial and innovative subjects under the country’s strong promotion of technological innovation (Dai et al., 2023; Wan et al., 2022). In the Yangtze River Delta, various measures have been implemented to favor entrepreneurship and innovation for the construction of a global science and technology innovation center, primarily prompting the technological innovation of high-tech enterprises so that this region has gradually established technology innovation parks and many high-tech ventures have emerged (Ye et al., 2023). These enterprises in the region are thus extremely representative for studying entrepreneurial leadership and employee change behavior that we investigated. We asked executives for permission to conduct this questionnaire survey within their enterprises, and then contacted human resources managers to obtain work group information to find appropriate and voluntary participants. With the help of human resources departments, we randomly selected employees from different functional work groups in each targeted enterprise to distribute questionnaires online and on site. Before filling in the questionnaire, we concretely explained this survey purpose to the participants and carefully answered their questions to ensure their understanding of the questionnaire content. At the same time, we guaranteed the anonymity and confidentiality of this survey to relieve the concerns of these respondents, and concealed variable names in the questionnaire to avoid psychological hints to them.

To reduce common method variance and strengthen causal inference, we gathered data from different time periods via nested questionnaires. In the first phase, participants reported demographic information and assessed entrepreneurial leadership of executives. Two months later, in the second phase, respondents who had completed the first survey rated their own thriving at work, autonomy orientation and taking charge. Notably, given that employees’ taking charge reflects individual inherent initiative, we applied employee self-evaluation to accurately measure this construct. Through the above two stages, questionnaires were distributed, recovered and matched. A total of 412 nested questionnaires were delivered to 85 work groups, and sample data was strictly screened to eliminate invalid questionnaires. Finally, 356 valid nested questionnaires were received, with a response rate of 86.41%. Among the 356 employees, 55.10% were male and 44.90% were female, 96.07% got a bachelor’s degree or above, and their average age and work tenure were 26.77 and 2.63 years, respectively.

Measures

All mature measures were taken from prior studies with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). These measures were converted from original English into Chinese version using the translation and back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1980).

Entrepreneurial leadership

This was measured by Huang et al. (2014) derived from Gupta et al. (2004), with 5 dimensions and 26 items. Sample items are “Executives undertake business risk to reduce the uncertainty in employees’ work” and “Executives encourages followers to think and use their minds, and challenge stereotypes”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale is .92.

Thriving at work

It was measured by Porath et al. (2012), with 2 dimensions and 10 items. Sample items are “I find myself learning often at work” and “I feel alive and vital at work”. Each dimension contains a reverse scoring item, namely “I am not learning at work” and “I do not feel very energetic at work”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale is .86.

Employees’ taking charge

This was measured by a 10-item scale from Morrison and Phelps (1999). Sample items are “I often try to adopt improved procedures for doing my work” and “I often make constructive suggestions for improving how things operate within the organization”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale is .92.

Employees’ autonomy orientation

It was measured by the causality orientation scale from Deci and Ryan (1985). The scale covers twelve hypothetical situations and three different types of causality orientation including autonomy orientation. For the purpose of this study, only five hypothetical situations related to employees’ work and corresponding items of autonomy orientation were selected. The Cronbach’s α of this scale is .79.

Control variables

Following previous research (Burnett et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019; Morrison & Phelps, 1999), due to the potential impact of demographic characteristics on employees’ taking charge, we controlled for employees’ gender (1 = male, 2 = female), age (in years), education (1 = college or below, 2 = bachelor, 3 = master, 4 = doctor) and work tenure (in years).

Results

Data aggregation

The research model in this study contains variables at the organizational and individual levels. As an organizational variable, entrepreneurial leadership was evaluated by individual employees, so it is necessary to examine the intra-group homogeneity and intergroup differences of the variable data to judge whether data from the individual level can be aggregated to the organizational level. Intergroup correlation coefficients ICC(1), ICC(2) and intra-group consistency coefficient Rwg are indicators to measure the feasibility of data aggregation. In general, Rwg should be greater than .70, and ICC(1), ICC(2) should be greater than .05 and .50, respectively. Among the data aggregation indicators of entrepreneurial leadership, ICC(1) is .15, ICC(2) is .54, and the mean of Rwg is .93. Therefore, the variable data reaches the aggregation requirements, that is, the data of entrepreneurial leadership measured at the individual level can be aggregated to the organizational level for cross-level analysis.

Confirmatory factor analysis

This study employed Harman’s single factor test and confirmatory factor analysis to assess the common method variance and discriminant validity. Involving all items together for principal component analysis without rotation, the results reveal that total variance explained by the first unrotated factor is 24.05%, which does not account for half of the total variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Moreover, as shown in Table 1, the results reflect that the one-factor model combining the four variables yields a poor fit (χ2/df = 9.296, RMSEA = .171, SRMR = .141, CFI = .586, TLI = .527). Hence, there is no serious common method variance in this study. Besides, the hypothesized four-factor model fits the data well (χ2/df = 1.773, RMSEA = .052, SRMR = .040, CFI = .963, TLI = .956) and is superior to other alternative models, indicating that four focal variables in the research model have adequate discriminant validity.

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 reports the means, standard deviations and correlations for all variables in this study. As expected, entrepreneurial leadership is positively related to thriving at work (r = .478, p < .01) and employees’ taking charge (r = .306, p < .01). Thriving at work is positively correlated with employees’ taking charge (r = .582, p < .01). Additionally, employees’ autonomy orientation has significantly positive associations with thriving at work (r = .431, p < .01) and employees’ taking charge (r = .548, p < .01).

Hypothesis testing

This study applied multilevel structural equation modeling with path analysis and Monte Carlo simulation procedures to test the proposed hypotheses using Mplus software (Preacher et al., 2010). As presented in Fig. 2 regarding path coefficients and their significance of the research model, entrepreneurial leadership is a positive predictor of thriving at work (β = .416, p < .01), and both entrepreneurial leadership (β = .274, p < .01) and thriving at work (β = .391, p < .01) have a positive impact on employees’ taking charge. On this basis, Monte Carlo simulation results show that the mediating effect of thriving at work is significant (indirect effect = .225, 95% CI = [.046, .293]). This demonstrates that entrepreneurial leadership can not only directly influence employees’ taking charge but also indirectly affect such behavior through thriving at work. In other words, thriving at work plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge. Thus, H1 and H2 are supported.

From the results of path analysis, employees’ autonomy orientation is found to positively moderate the relationship between thriving at work and employees’ taking charge (β = .298, p < .05). Simple slopes were plotted with the moderator mean above and below one standard deviation to further qualify the moderating effect (Aiken & West, 1991). As illustrated in Fig. 3, the simple slope relating thriving at work to employees’ taking charge at employees’ high autonomy orientation (β = .658) is much greater than that at employees’ low autonomy orientation (β = .195). It can be seen that the positive impact of thriving at work on taking charge of employees with high autonomy orientation is stronger compared with low autonomy orientation. Therefore, H3 is supported.

In addition, Monte Carlo simulation (repeated for 5000 times) was run to estimate the conditional indirect effects of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ taking charge via thriving at work, in order to prove the moderating effect of employees’ autonomy orientation on the mediation of thriving at work. The results are displayed in Table 3. When employees’ autonomy orientation is high, entrepreneurial leadership has a significant indirect effect on their taking charge (effect = .174, 95% CI = [.046, .295]), while this indirect effect is not significant when employees’ autonomy orientation is low (effect = .043, 95% CI = [-.037, .122]). Meanwhile, the indirect effects of the two conditions are significantly different (difference = .131, 95% CI = [.052, .263]). This indicates that employees’ autonomy orientation positively moderates the indirect relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge via thriving at work. Such relationship is stronger at employees’ high autonomy orientation than at low autonomy orientation, offering support for H4.

Discussion

This study develops a cross-level moderated mediation model to explore how entrepreneurial leadership at the organizational level influences employees’ taking charge at the individual level, taking the proactive motivation model as the theoretical basis to discuss the mediating role of thriving at work and the moderating effect of employees’ autonomy orientation in this process. Through empirical analysis, this study supports the research model and hypotheses, leading to several crucial findings. Specifically, the direct effect results demonstrate that entrepreneurial leadership can promote employees’ taking charge. Framing challenges, absorbing uncertainty, clearing paths, building commitment and specifying limits, as five salient characteristics of entrepreneurial leadership (Gupta et al., 2004), make employees perceive organizational entrepreneurial orientation, risk-taking spirit and reform preference and determine individual action directions (Haim Faridian, 2023; Lingo, 2020), thereby impelling them to take charge. Furthermore, the mediation results show that entrepreneurial leadership inspires employees’ taking charge by strengthening their thriving at work. Entrepreneurial leadership can set challenging goals, construct entrepreneurial vision and encourage adventure and creation within the organization, this keeps employees energetic and actively learning for organizational change and innovation (Sawaean & Ali, 2020; Yan et al., 2021), which activates their strong thriving at work to take charge. Besides, according to the moderation results, employees’ autonomy orientation exacerbates the direct effect of thriving at work on employees’ taking charge as well as the indirect effect of entrepreneurial leadership on such behavior via thriving at work. For employees with high autonomy orientation, thriving at work is more likely to stimulate their taking charge, and entrepreneurial leadership plays a more prominent role in augmenting thriving at work of employees to take charge. This is because highly autonomy-oriented employees have great independent consciousness and intrinsic motivation and tend to engage in challenging or innovative work (Liu & Fu, 2011), which thus amplifies the positive influence of entrepreneurial leadership on thriving at work and subsequent taking charge of employees.

Theoretical implications

These findings yield important theoretical contributions. First, this study provides insights into the drivers of taking charge and the effectiveness of entrepreneurial leadership toward individual proactive behavior through revealing the underlying connection of entrepreneurial leadership with employees’ taking charge. On the one hand, scholars have identified the antecedents of taking charge from organizational leadership and individual internal factors (e.g. Cai et al., 2019b; Liu et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2023), especially studying various types of leadership (e.g. Du & Yan, 2022; Wang et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2018), but neglecting entrepreneurial leadership that has great potential to cultivate employees’ taking charge. On the other hand, the existing research has confirmed the positive effect of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ innovation behavior, organizational commitment and job satisfaction (e.g. Iqbal et al., 2022; Pu et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2019), yet there is little discussion on their taking charge. It is significant to investigate the linkage between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge, as this leadership particularly encompasses adventure and change characteristics that favor such proactive behavior in the current uncertain environment of entrepreneurship and innovation. Hence, this study fills up the research gap by connecting the two constructs theoretically and empirically to establish the pivotal role of entrepreneurial leadership in facilitating employees’ taking charge. It adds to the stream of literature that looks at the driving forces of taking charge from the leadership perspective and the effectiveness of entrepreneurial leadership toward employee proactive behavior.

Second, this study sheds light on the influencing mechanism of entrepreneurial leadership toward employees’ taking charge with a psychological lens by adopting the proactive motivation model. Previous studies examined how entrepreneurial leadership prompts employees’ creative self-efficacy for their innovation behavior and creativity based on social cognitive theory (e.g. Akbari et al., 2021; Cai et al., 2019a), or explained the mediating role of employees’ psychological safety in the association between entrepreneurial leadership and individual job performance (e.g. Miao et al., 2019). In contrast, since taking charge is self-initiated and driven by intrinsic motivation, this study takes the proactive motivation model as the basic theory to develop a theoretical framework that combines entrepreneurial leadership, thriving at work and employees’ taking charge. It discusses how thriving at work among employees is inspired by entrepreneurial leadership and further translated into their taking charge. Underscoring the transmission role of thriving at work, this framework excavates the underlying psychological mechanism of entrepreneurial leadership fostering employees’ taking charge, which advances knowledge about how organizational leadership spreads its effect to the proactive behavior of individual employees. Also, the proactive motivation model is extended because of its unique application in this research field.

Third, this study highlights the importance of individual differences in altering the impact of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ proactive extra-role behavior through focusing on the contingency of personality traits. Findings about the moderating effect of employees’ autonomy orientation demonstrate this boundary condition of the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge, and indicate that the magnitude of such connection depends on employees’ autonomy orientation. In other words, the impact of thriving at work on employees’ taking charge and the influence of entrepreneurial leadership on this behavior via thriving at work, vary with the degree of employees’ autonomy orientation. Highly autonomy-oriented employees are more likely to take charge in a state of thriving at work, whereas entrepreneurial leadership has a stronger effect on thriving at work and taking charge of such employees. Overall, the validation of the moderator in this study uncovers the potential benefit of employees’ autonomy orientation, responding to the demand for examining whether individual proactive personality affects entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness (Miao et al., 2019).

Finally, this study expands the cross-level research on entrepreneurial leadership and taking charge by expounding how entrepreneurial leadership permeates the hierarchy throughout the organization to drive individual employees to take charge. Current studies on entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness pay little attention to its cross-level influence (e.g. Li et al., 2020; Sani et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019). Although the widely recognized measure of entrepreneurial leadership is targeted at the organizational level (Gupta et al., 2004), a few cross-level studies only concentrate on team entrepreneurial leadership affecting individual outcomes (e.g. Cai et al., 2019a; Miao et al., 2019). Constructing a cross-level moderated mediation model, this study empirically analyzes the influence process of organizational entrepreneurial leadership on individual employee taking charge, and confirms the cross-level partial mediating role of thriving at work and the moderating effect of employees’ autonomy orientation as well as the cross-level moderated mediation in this process. These findings are consistent with the essence about multilevel influence of leadership (Yammarino & Dansereau, 2011). Moreover, the method of this study echoes the call for more leadership studies to be conducted in Asia (Lythreatis et al., 2022), and also answers the call for longitudinal empirical research design regarding entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness by taking two time periods to define model causality (Yang et al., 2019).

Practical implications

This study is of great practical significance for executives to perform effective leadership to activate employees’ proactive motivation to take charge. First, executives need to adopt the holistic approach of entrepreneurial leadership to exploit opportunities and implement change to maintain enterprise sustainable development. Entrepreneurial leadership is conducive to modern enterprises dealing with environmental dynamics by developing entrepreneurial opportunities and carrying out innovative activities. The findings suggest that entrepreneurial leadership is useful in employees’ taking charge. Thus, executives should leverage the core competencies of entrepreneurial leadership including framing challenges, absorbing uncertainty, clearing paths, building commitment and specifying limits to spur employees to take charge. Specifically, executives can establish an inspiring organizational vision to gain the recognition and commitment from employees, signal that enterprises encourage reform and innovation and take the initiative to bear risk, determine business scope and provide role clarity for employees, and create favorable work environment to empower employees, which triggers their engagement in taking charge such as changing workflows, introducing new techniques and designing novel products or services.

Second, executives should take essential measures to augment employees’ thriving at work, stimulate their proactive motivation of reform or creation and then motivate them to take charge. This study verifies the mediating role of thriving at work in entrepreneurial leadership facilitating employees’ taking charge. Thriving at work is employees’ positive psychological state, where work vitality and learning tendency make employees raise their self-efficacy and creativity. Therefore, executives are supposed to manifest entrepreneurial leadership, take appropriate incentives and offer supportive conditions to reinforce employees’ thriving at work, in order to mobilize their intrinsic motivation for proactive extra-role behavior. For example, executives can infect employees by conveying strong positive emotions, give staff courage, confidence or hope through communicating an attractive vision, setting challenging goals and clarifying specific directions, and acquire their approval for organizational change, which enhances employees’ work vitality and learning tendency so that they spontaneously challenge stereotypes and initiate reform.

Third, executives should pay attention to the impact of employees’ autonomy orientation on enterprise activities. This study highlights the moderating role of employees’ autonomy orientation in the connection between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge. Autonomy orientation influences individual intrinsic motivation and proactive behavior. Highly autonomy-oriented employees have relatively complete modern personality, who possess a strong sense of self-determination and self-realization. Thereby, executives need to advocate individual autonomy orientation, meet employees’ independent and personalized demand, and provide an autonomous work environment to display their strengths, so that they are driven by intrinsic incentives to take charge for self-worth pursuit and organizational value creation. Moreover, since this personality trait of employees would affect entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness, human resources departments can conduct certain training programs to cultivate employees’ autonomy and initiative, and adopt some psychological tests to seek talents with proactive personality and autonomy orientation.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the theoretical and practical importance of this study, there are several limitations to be addressed in the future. First, this study validates the partial mediating role of thriving at work between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ taking charge from the psychological perspective, which implies the existence of other mediators in this relationship. More studies should explore additional potential mediators from diverse perspectives and determine which one can better transmit the impact of entrepreneurial leadership. Second, this study examines the moderator linking thriving at work to employees’ taking charge, future research might consider other possible contingency factors that interact with entrepreneurial leadership to foster thriving at work and taking charge of employees. For instance, environmental dynamism and ambiguity may be important boundary conditions regarding entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness. Third, this study only focuses on employees’ taking charge as the outcome variable concerning employees’ proactive behavior, more outcomes about such behavior are recommended to be covered. Fourth, this study sampled Chinese high-tech enterprises to verify the hypothesized research model. Given that different business domains and cultural contexts may affect entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness as well as employees’ state, personality and proactive behavior, future research should involve cross-industry and cross-cultural samples to investigate whether this influence exists for broader applicability of the findings. Besides, although this study collected data in two waves to reduce common method bias and reflect model causality, the data was self-reported by employees, and the mediation variable and dependent variable were measured at the same time point. In the future, research is supposed to employ a more rigorous longitudinal design with multiple time points and different sources to assess variables, which can replicate the research model to better remove common method bias and claim causal relationship.

Conclusion

This study examines how organizational entrepreneurial leadership affects individual employee taking charge and when this influence is more effective based on the proactive motivation model. It confirms that entrepreneurial leadership could promote employees’ taking charge by raising thriving at work and employees’ autonomy orientation would amplify this effectiveness. These empirical findings reveal the psychological mechanism and boundary condition of entrepreneurial leadership toward employees’ taking charge, extend the knowledge of entrepreneurial leadership effectiveness and employee proactive behavior, and provide some valuable recommendations that executives can adopt to foster organizational change and innovation.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Akbari, M., Bagheri, A., Imani, S., & Asadnezhad, M. (2021). Does entrepreneurial leadership encourage innovation work behavior? The mediating role of creativity self-efficacy and support for innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(1), 1–22.

Albrecht, S. L., Connaughton, S., Foster, K., Furlong, S., & Yeow, C. J. L. (2020). Change engagement, change resources, and change demands: A model for positive employee orientations to organizational change. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 531944.

Alikaj, A., Ning, W., & Wu, B. (2020). Proactive personality and creative behavior: Examining the role of thriving at work and high-involvement HR practices. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(5), 857–869.

Bagheri, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurial leadership on innovation work behavior and opportunity recognition in high-technology SMEs. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 28(2), 159–166.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology. Allyn and Bacon.

Burnett, M. F., Chiaburu, D. S., Shapiro, D. L., & Li, N. (2015). Revisiting how and when perceived organizational support enhances taking charge: An inverted U-shaped perspective. Journal of Management, 41(7), 1805–1826.

Cai, W., Lysova, E. I., Khapova, S. N., & Bossink, B. A. G. (2019a). Does entrepreneurial leadership foster creativity among employees and teams? The mediating role of creative efficacy beliefs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 203–217.

Cai, Z. Y., Huo, Y. Y., Lan, J. B., Chen, Z. G., & Lam, W. (2019b). When do frontline hospitality employees take charge? Prosocial motivation, taking charge, and job performance: The moderating role of job autonomy. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 60(3), 237–248.

Dai, X., Tang, J., Huang, Q., & Cui, W. (2023). Knowledge spillover and spatial innovation growth: Evidence from China’s Yangtze River Delta. Sustainability, 15(19), 14370.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134.

Du, Y., & Yan, M. (2022). Green transformational leadership and employees’ taking charge behavior: The mediating role of personal initiative and the moderating role of green organizational identity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4172.

Duarte Alonso, A., Vu, O. T. K., Kok, S. K., & O’Shea, M. (2023). Adapting to dynamic business environments: A comparative study of family and non-family firms operating in Western Australia. Management Research Review, 46(5), 755–775.

Gagne, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362.

Gupta, V., MacMillan, I. C., & Surie, G. (2004). Entrepreneurial leadership: Developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 241–260.

Haim Faridian, P. (2023). Leading open innovation: The role of strategic entrepreneurial leadership in orchestration of value creation and capture in GitHub open source communities. Technovation, 119, 102546.

Hirak, R., Peng, A. C., Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 107–117.

Huang, S., Ding, D., & Chen, Z. (2014). Entrepreneurial leadership and performance in Chinese new ventures: A moderated mediation model of exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation and environmental dynamism. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(4), 453–471.

Hussain, N., & Li, B. (2022). Entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success: The role of knowledge management processes and knowledge entrepreneurship. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 829959.

Iqbal, A., Nazir, T., & Ahmad, M. S. (2022). Entrepreneurial leadership and employee innovative behavior: An examination through multiple theoretical lenses. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(1), 173–190.

Kim, S. L., Yun, S., & Cheong, M. (2023). Empowering and directive leadership and taking charge: A moderating role of employee intrinsic motivation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(6), 389–403.

Koryak, O., Mole, K. F., Lockett, A., Hayton, J. C., Ucbasaran, D., & Hodgkinson, G. P. (2015). Entrepreneurial leadership, capabilities and firm growth. International Small Business Journal, 33(1), 89–105.

Kumar, N., Liu, Z., & Jin, Y. (2022). Evaluation of employee empowerment on taking charge behaviour: An application of perceived organizational support as a moderator. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1055–1066.

Li, C., Makhdoom, H. U. R., & Asim, S. (2020). Impact of entrepreneurial leadership on innovative work behavior: Examining mediation and moderation mechanisms. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 105–118.

Li, S., Sun, F., & Li, M. (2019). Sustainable human resource management nurtures change-oriented employees: Relationship between high-commitment work systems and employees’ taking charge behaviors. Sustainability, 11(13), 3550–3564.

Lingo, E. L. (2020). Entrepreneurial leadership as creative brokering: The process and practice of co-creating and advancing opportunity. Journal of Management Studies, 57(5), 962–1001.

Liu, D., Chen, X., & Yao, X. (2011). From autonomy to creativity: A multilevel investigation of the mediating role of harmonious passion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 294–309.

Liu, D., & Fu, P. (2011). Motivating protégés’ personal learning in teams: A multilevel investigation of autonomy support and autonomy orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1195–1208.

Liu, M., Zhang, P., Zhu, Y., & Li, Y. (2022). How and when does Visionary leadership promote followers’ taking charge? The roles of inclusion of leader in self and future orientation. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1917–1929.

Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Lester, P. B. (2016). Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Human Resource Development Review, 5(1), 25–44.

Lythreatis, S., El-Kassar, A. N., Smart, P., & Ferraris, A. (2022). Participative leadership, ethical climate and responsible innovation perceptions: Evidence from South Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09856-3

Mehmood, M. S., Jian, Z., Akram, U., & Tariq, A. (2020). Entrepreneurial leadership: The key to develop creativity in organizations. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(3), 434–452.

Mehmood, M. S., Jian, Z., & Waheed, A. (2019). The influence of entrepreneurial leadership on organizational innovation: Mediating role of innovation climate. International Journal of Information Systems and Change Management, 11(1), 70–89.

Miao, Q., Eva, N., Newman, A., & Cooper, B. (2019). CEO entrepreneurial leadership and performance outcomes of top management teams in entrepreneurial ventures: The mediating effects of psychological safety. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(3), 1119–1135.

Morrison, E. W., & Phelps, C. C. (1999). Taking charge at work: Extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 403–419.

Olesen, M. H., Thomsen, D. K., Schnieber, A., & Tønnesvang, J. (2010). Distinguishing general causality orientations from personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 538–543.

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856.

Paterson, T. A., Luthans, F., & Jeung, W. (2014). Thriving at work: Impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 434–446.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. G. (2012). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250–275.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233.

Pu, B., Sang, W., Yang, J., Ji, S., & Tang, Z. (2022). The effect of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ tacit knowledge sharing in start-ups: A moderated mediation model. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 137–149.

Ren, L., Liu, Y., & Yin, Y. (2023). Do grateful employees take charge more in China? A joint moderating effect model. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(1), 70–88.

Renko, M., El Tarabishy, A., Carsrud, A. L., & Brännback, M. (2015). Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 54–74.

Sani, A., Ekowati, V. M., Wekke, I. S., & Idris, I. (2018). Respective contribution of entrepreneurial leadership through organizational citizenship behaviour in creating employee’s performance. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 24(4), 1–11.

Sawaean, F. A. A., & Ali, K. A. M. (2020). The impact of entrepreneurial leadership and learning orientation on organizational performance of SMEs: The mediating role of innovation capacity. Management Science Letters, 10(2), 369–380.

Simba, A., & Thai, M. T. T. (2019). Advancing entrepreneurial leadership as a practice in MSME management and development. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(S2), 397–416.

Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., & Dutton, J. (2005). A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organizational Science, 16(5), 537–550.

Supartha, W. G., & Saraswaty, A. N. (2019). Entrepreneurial leadership on organizational performance: A case of credit cooperatives in Bali Indonesia. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 14(1), 233–241.

Wan, Q., Chen, J., Yao, Z., & Yuan, L. (2022). Preferential tax policy and R&D personnel flow for technological innovation efficiency of China’s high-tech industry in an emerging economy. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 174, 121228.

Wang, Q., Wang, J., Zhou, X., Li, F., & Wang, M. (2020). How inclusive leadership enhances follower taking charge: The mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of traditionality. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 1103–1114.

Wang, T., Wang, D., & Liu, Z. (2022). Feedback-seeking from team members increases employee creativity: The roles of thriving at work and mindfulness. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39(4), 1321–1340.

Wen, Q., Liu, R., & Long, J. (2021). Influence of authentic leadership on employees’ taking charge behavior: The roles of subordinates’ moqi and perspective taking. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 626877.

Wu, T., Chen, B., Shao, Y., & Lu, H. (2021). Enable digital transformation: Entrepreneurial leadership, ambidextrous learning and organisational performance. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 33(12), 1389–1403.

Wu, X. F., Kwan, H. K., Wu, L. Z., & Ma, J. (2018). The effect of workplace negative gossip on employee proactive behavior in China: The moderating role of traditionality. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 801–815.

Xu, Q., Zhao, Y., Xi, M., & Zhao, S. (2018). Impact of benevolent leadership on follower taking charge: Roles of work engagement and role-breadth self-efficacy. Chinese Management Studies, 12(4), 741–755.

Yammarino, F. J., & Dansereau, F. (2011). Multi-level issues in evolutionary theory, organization science, and leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1042–1057.

Yan, A., Tang, L., & Hao, Y. (2021). Can corporate social responsibility promote employees’ taking charge? The mediating role of thriving at work and the moderating role of task significance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 613676.

Yang, J., Pu, B., & Guan, Z. (2019). Entrepreneurial leadership and turnover intention in startups: Mediating roles of employees’ job embeddedness, job satisfaction and affective commitment. Sustainability, 11(4), 1101–1115.

Ye, J., Jiang, Y., Hao, B., & Feng, Y. (2023). Knowledge search strategies and corporate entrepreneurship: Evidence from China’s high-tech firms. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(2), 564–587.

Zhang, M. J., Law, K. S., & Wang, L. (2021). The risks and benefits of initiating change at work: Social consequences for proactive employees who take charge. Personnel Psychology, 74(4), 721–750.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71972074) and the Research Program of Guangdong University of Foreign Studies (No. 2022RC084).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Q., Yi, L. How does entrepreneurial leadership affect employees’ taking charge? A cross-level moderated mediation process. Asia Pac J Manag (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09943-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09943-z