Abstract

Although team diversity is a focal research topic in mainstream organizational behavior research (Harrison & Klein, 2007; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998), only a limited number of team diversity studies from non-North American or European communities have been published in English-language journals. Through a review in Study 1, we noticed this puzzling lack of research on team diversity in China (see the statistics in Table 1), and we wonder whether team diversity is a salient and meaningful topic in Chinese organizations, and if it is, what diversity attributes are important for Chinese employees. In Study 2, we interviewed 92 employees working in 38 teams from nine companies in China and found that many employees experienced diversity (72.13%) in working groups, and considered diversity to be important and desirable (45.9%). The list of salient diversity attributes shared by Chinese employees often overlap with attributes studied in the extant literature, yet Chinese employees also articulated attributes that were rarely examined by researchers. In addition, we discovered how Chinese employees sometimes associate conflicts, one of the major working mechanisms of team diversity, with team dysfunctions and leadership incompetence, which makes team diversity a taboo topic in the workplace. We discussed the theoretical implications of our findings to team diversity research in Asia and practical implications for team diversity management in Chinese organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Countries in Southeast Asia are leading growth engines in the world economy, mainly because of their labor force advantage (OECD Development Centre, 2020). When teams are widely employed to enhance organizational performance, team diversity, the distribution of differences among team members on a given attribute, has consistently been demonstrated to have a significant impact on various aspects of team functioning, including team conflict, decision making quality, team integration, creativity, and ultimately on performance (Harrison & Klein, 2007; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). Robust results from reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., Bell et al., 2011; Guillaume et al., 2017; Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007) together with the prevalence of diverse teams in different parts of the world seem to indicate that team diversity is a universal phenomenon and its impact on team functioning could be generalized across different cultures and economic systems (Jackson & Joshi, 2011). Meanwhile, Jackson & Joshi (2011) found that most of the research published in English-language journals was conducted in North American or European organizations, but rarely in Asian organizations. Therefore, we are interested to know whether diversity is important to organizational employees in Asia, if it is, what diversity attributes are salient to them, and how these attributes impact employees working in teams. In this paper, we focused on China because of its vast population in Asia and its cultural differences from North America and Europe.

We began our research with a background update on the prominence of diversity research, including team diversity research, conducted in Chinese organizations, given that Jackson and Joshi’s (2011) observation was made 10 years ago. In Study 1, we searched within two groups of major management journals—global and Asian regional management journals—to count studies published in these journals with Chinese samples that examined diversity as their focal topic from 1998 (the year when the review from Williams and O’Reilly was published) to 2021. Studies that investigated differences in demographics, personalities, cultures, and values were identified. For comparison, we also counted the number of journal articles with a focal topic on leadership and team conflict. Leadership is generally considered important in Chinese organizations (Lam et al., 2012) and team management (Zhao et al., 2019), as China has a culture with high power distance, and leaders are authorized with high power to manage teams (Hofstede et al., 2010), whereas team conflict has important implications on team performance (De Wit et al., 2012) and is always associated with team diversity (Bell et al., 2011; Guillaume et al., 2017; Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007). As shown in Table 1, we found only 23 articles on diversity and 14 articles on team conflict in top-tiered management journals while, within the same time period, 180 articles on leadership. Among the regional journals, articles on diversity, team conflict, and leadership were 20, 17, and 61 respectively. The ratios of articles on diversity and conflict to those on leadership were small, reflecting a relative lack of emphasis on diversity. Furthermore, we differentiated whether these diversity studies focused on team diversity or not. As shown in the final column of Table 2, only 14 studies out of 43 were on team diversity, further reflecting the lack of emphasis on team diversity.

Based on the above intriguing observations, we question whether team diversity is important to Chinese teams. The outstanding puzzle is why team diversity has been a fundamental and important input for team outcomes in organizations in North America and Europe (e.g., Williams & O’Reilly identified 89 articles of diversity research from 1958 to 1997; Bell et al. identified 92 articles from 1980 to 2009) but was less examined in China (14 articles from 1998 to 2021 as shown in Table 2). Taking into consideration a series of social and cultural differences between the Chinese community and the North American and European communities (Chatman et al., 1998), we propose two potential explanations that may account for the lack of research interest in team diversity in Chinese organizations. First, we speculate that diversity attributes salient in China may be different from those salient in North America and Europe. Second, we wonder whether team diversity has a different or limited impact on Chinese organizations due to Chinese unique cultural factors. If the diversity attributes or the impact of team diversity widely discussed in the Western literature are perceived to be of low relevance to China, then it may explain why scholars would lack interest in studying team diversity in Chinese organizations.

To test these two conjectures, in Study 2, we conducted a series of interviews with 92 Chinese employees who are from various function teams (38 in total) of different industries and we summarized their responses to identify diversity attributes that are salient to them and the working mechanisms of these diversity attributes on team outcomes. “Qualitative research is well-suited for describing, interpreting, and explaining” a phenomenon but not “for examining issues of prevalence, generalizability, or calibration” (Lee, 1999, p. 38). The data collected from interviews allow us to understand the contextualized meaning of team diversity in Chinese organizations and provide richness in the description of interpersonal and team processes, as well as their corresponding outcomes.

In this research, we aim to contribute to team diversity research in three ways. First, while the extant literature generally assumes that team diversity is important for team performance, few studies have explored the generalizability of this belief across regions and cultures. Countries in Asia, especially in East Asia, such as China, Japan, and South Korea, are important economic entities (OECD Development Centre, 2020), however, our knowledge of how team diversity works in these regions is limited (Chen et al., in press). Through interviewing Chinese employees working in teams, we hope to gain more insights regarding how team diversity works in this understudied cultural region. Second, rather than assuming equal significance of diversity attributes, we examine team members’ subjective evaluation of the importance and meanings of various diversity attributes during team processes. Our exploratory qualitative research design enables us to explore contextually unique diversity attributes that are meaningful to Chinese team workers, as well as the relative significance of each diversity attribute in Chinese organizations. Third, we explore the mechanisms through which team diversity impacts teams. Compared with North America and Europe where racial/ethnic diversity is common among teams, racial diversity is not a highly salient surface-level attribute in Asia, especially in East Asia, such as China, Japan, and South Korea. In North America and Europe, people of different races may have different skin colors, yet people in Asia have rather similar skin colors. At the same time, unique cultures such as harmony have significant influences on interaction norms between employees (Chen et al., 2015, 2016), but we know less about the working mechanisms of team diversity in these cultures (Chatman et al., 1998). Thus, we respond to calls for understanding how context affects the salience and meaning of diversity attributes (Joshi & Neely, 2018; Roberson, 2019). We also explore the possibility of ‘new’ diversity attributes and corresponding working mechanisms that are rarely studied in the extant literature.

Theory

Diversity refers to individual differences in any attribute that may lead to the perception that another person is different from self (Harrison & Klein, 2007; van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). Team diversity has been a focal topic in mainstream organizational behavior research for decades, as extant literature shows that team compositions of characteristics are essential inputs of team processes and outcomes (Mathieu et al., 2008). Diversity attributes are one of the core foundations of diversity research, as they define what diversity is. The characteristics team members used to differentiate themselves include surface-level attributes, such as gender, age, and race, and deep-level attributes, such as personality and values in extant research (Harrison et al., 1998, 2002). However, the lack of team diversity research in Chinese organizations (as shown in Table 1) makes us doubt whether team diversity is viewed as important in Chinese organizations, whether the diversity attributes widely studied in the extant literature are important in China, and whether the corresponding working mechanisms of team diversity can be generalized to this region. In the next section, we will review related theories and findings that address these questions, and propose how this research complements existing studies.

Demographic diversity in the Chinese population and workforce

Reviewing 88 studies with 487 reported effects, Jackson & Joshi (2011) found that gender and race/ethnicity were the most often reported attributes in diversity research. In the North American and European communities, race or ethnicity is an important topic rooted in their histories (Sy et al., 2010). Together with gender, they are the most salient attributes that are readily detectable in social interactions. This may partly explain their popularity in team diversity research. Other than race/ethnicity and gender, research has recognized the existence of other diversity attributes, including relationship-oriented attributes such as age, nationality, religion, personality, attitudes, and values; and task-oriented attributes such as organizational tenure, functional background, and cognitive abilities. Jackson and Joshi (2011) also found that most of the research published in English-language journals was conducted in North American or European organizations. Does it mean that diversity is not an important management issue in regions with less salient racial differences?

Compared to the North American and European regions in which racial diversity has been a thorny issue, over 90% of the population in China is Han Chinese (i.e., an ethnic group, Major Figures on 2020 Population Census of China, National Bureau of Statistics), therefore, non-Han employees are usually numerical minorities in China. Besides, many ethnic minorities in China are not easy to distinguish from Han Chinese in appearance. When race is not a highly salient surface-level diversity attribute in China, it is less likely to trigger identity differentiation among acquaintances, even though it can be a significant deep-level attribute. This may be one of the reasons why race-related concerns such as discrimination, perceptual biases, and workplace fairness have often been reported in the North American workplace (Sy et al., 2010), but are less mentioned in Chinese organizations. Nevertheless, other diversity attributes commonly investigated in North American and European communities such as gender, age, and educational diversity exist in the Chinese workforce. For instance, among the Chinese workforce, the ratio of males to females is 51:49, which indicates the existence of gender diversity. The age of the workforce is evenly distributed in China (the ratio of age 16–19 = 1.0%, 20–24 = 6.6%, age 25–29 = 12.1%, age 30–34 = 13.9%, age 35–39 = 11.7%; age 40–44 = 11.5%, age 45–49 = 13.7%, age 50–54 = 11.7%, age 55–59 = 7.7%, age 60–64 = 4.6%, and age above 65 = 5.7%, China Population & Employment Statistical Yearbook 2020, National Bureau of Statistics), which indicates the presence of age diversity. And among Chinese workforces, around 40.6% had completed middle school, 18.7% had completed high school, 12.0% had a degree from college, 9.7% had a bachelor’s degree, and 1.1% had a master’s or above degree (China Population & Employment Statistical Yearbook 2020, National Bureau of Statistics). These statistics show that even though lacking the driving force of race diversity, as compared with research in North American and European organizations, diversity in surface-level attributes, such as gender, age, and education are common in Chinese organizations, which deserves more research attention.

Team diversity and its impact on teams

Various theories have been proposed to predict how diversity relates to performance, yet they lead to competing predictions that oppose each other. According to social identity (Tajfel, 1978) and social categorization theory (Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1987), similar individuals are more likely to categorize themselves into groups (Byrne, 1971), and they could receive mutual understanding and social support from team members when needed. Thus, lower diversity within the team could enhance the belongingness of members, which could be beneficial to team performance. However, the information elaboration perspective (van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998) points out that different individuals could bring diverse knowledge, skills, and perspectives into the team and which could stimulate the generation of new ideas and alternatives in problem-solving. That is to say, the higher the team diversity, the better the team performance. Both perspectives received support from empirical studies, which lead to the more integrative categorization-elaboration model (CEM) of diversity research (van Knippenberg et al., 2004). Based on CEM, diversity could increase group performance through boosting the elaboration of task-relevant information and perspective, however, differences in diversity attributes could also lead to social categorization and relationship conflict, which weaken the beneficial effect of diversity on information elaboration. Despite these advancements in theoretical development, empirical findings suggest that the directions of diversity effect are mixed (Roberson, 2019) and the effect size is small (Joshi & Roh, 2009). A meta-analysis from Bell and colleagues (2011) pointed out the necessity to get specific about the demographic attribute when examining the relationship between team diversity and team performance. For instance, they found that race (ρ = − 0.14) and sex (ρ = − 0.06) diversity were negatively related to team performance; age (ρ = 0.01), organizational tenure (ρ = 0.06), team tenure (ρ = − 0.01), and educational background (ρ = − 0.03) diversity were unrelated to team performance; whereas functional background (ρ = 0.12) was positively related to team performance (Bell et al., 2011).

Given the weak linkage between diversity and organizational outcomes, several studies have been devoted to uncovering potential contingent factors. For instance, Joshi & Roh (2009) reviewed 39 organizational team studies and found that industry (service vs. high-technology), occupation (gender, race, and age balanced vs. unbalanced), and team-level factors (team interdependence and team type) could moderate the relationships between team diversity and team performance. However, only a few exceptional studies have revealed that the importance of diversity differed in different locations or different cultures. For instance, Van der Vegt et al. (2005) found that locational level differences in power distance cultural values could moderate the relationship between demographic diversity and team outcomes. Nevertheless, the over-concentration of empirical studies conducted in North American and European regions limits our understanding regarding how diversity affects team or organizational performance in other regions or cultures, such as China, South Korea, and Japan (Hofstede et al., 2010; Hofestede & Minkov, 2010).

Even though diversity exists in the Chinese workforce, we need more studies to discover whether such differences are subjectively significant to team members in this specific context, and to find out the meaningful differences they used to categorize themselves (Turner et al., 1987). Extant workplace diversity research examines mostly demographic attributes, such as gender, race, age, educational background, and tenure, etc. (Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). Some, but relatively few, studies examine deep-level attributes such as personality and values (Harrison et al., 2002). Furthermore, only a few studies have investigated unique attributes that may be influential to employees in a specific context, such as ‘language fluency’ in globally distributed teams (Hinds et al., 2014) and ‘prior start-up experience’ in new venture teams (Vissa & Chacar, 2009). Therefore, despite a lack of research on team diversity in Chinese organizations, team diversity may be important to Chinese employees, and the key is to identify contextually relevant diversity attributes that are influential and significant to Chinese employees. Using Chinese organizations as examples, we engage in qualitative research to explore whether team diversity matters in Chinese organizations and if it does, what attributes are important to team members.

Furthermore, we are interested in investigating how team diversity will impact team performance in Chinese organizations. Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) has been the major perspective to examine the impact of team diversity on team performance, and based on this theory, conflict among different social identity groups has been proposed to be the major mechanism through which team diversity impact team performance (Jehn et al., 1999). Meanwhile, harmony (Wei & Li, 2013), “the ambient relationship concord as manifested in the affect, cognition, and behavior of group members” (Chen et al., 2016, p. 907), is a valued component of Chinese culture. Confucianism highlights harmony as a cardinal value for society and it has an immense influence on social interactions (Leung et al., 2002; Wright & Twitchett, 1962). Chinese are socialized to maintain harmony and to avoid conflict in their interaction with others (Chen et al., 2015). Meanwhile, Chinese employees are usually high in the collectivism cultural dimension (Hofstede et al., 2010), which means that they may treat team conflict as a potential threat to reaching collective goals, therefore, avoiding bringing up conflicts in the team. If team diversity can potentially increase conflict within groups (van Knippenberg et al., 2004), Chinese employees may perceive the topic of team diversity as taboo and may avoid discussing team diversity in fear of triggering conflict among team members (Chen et al., 2015, 2016). The limited research on team conflict conducted in Chinese organizations as compared with research on leadership (shown in Table 1) hints that research topics that threaten harmony may not appeal to Chinese organizations. The comparison also showed that leadership is widely accepted as an important factor in Chinese organizations, therefore, we also explore the role of leaders in team diversity management (Zhao et al., 2019).

Overview of studies

In the following sections, we will introduce our two studies and show our main findings in addressing our research questions. In Study 1, we counted the number of journal articles on team diversity, team conflict, and leadership respectively. In the earlier section, we have shared the results of the count, as shown in Table 1. Next, we focused on team diversity journal articles and summarized the diversity attributes that have been examined with Chinese samples to illustrate what attributes have been considered important by team diversity researchers. In Study 2, we conducted a qualitative study to explore what diversity attributes are perceived as important by Chinese employees and how team diversity impacts team performance in their organizations, especially diversity attributes that are unique in Chinese organizations.

Study 1: A review of diversity attributes in Chinese management research samples

In Study 1, we reviewed diversity studies with Chinese samples published in global and regional management journals, from 1998 (the year when the review from Williams and O’Reilly was published) to 2021. We found a total number of 43 articles and we categorized them by diversity attributes.

As shown in Tables 2 and 19 studies examined the effect of demographics (44.2%), including 12 studies (27.9%) that focused on gender diversity, suggesting that diversity attributes that are commonly examined in North America and Europe may be important to Chinese employees too. We found that 13 studies examined values and cultural diversity (30.2%), whereas only four studies examined context-specific attributes, such as dialect (Gong et al., 2012), rural-urban migratory experience (Hao & Liang, 2016), and returnees with overseas education or work experience (Lin et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2021), indicating that both common and unique attributes seem salient to Chinese employees. To explore what attributes Chinese employees perceive to be important and the reasons behind that, we conducted qualitative research and interviewed team workers in Chinese organizations in Study 2.

Study 2: A qualitative study

Methods

Sample and data collection

Because our goal was to explore the importance and the mechanism of team diversity in Chinese organizations, rather than test theory, we selected sampling teams that varied in type and characteristics to maximize the variance of diversity effects (Joshi & Roh, 2009). Based on the findings from Joshi and Roh (2012), we purposefully selected teams from companies that differ in industry (manufacturing, service, and high-technology), occupational composition (male-dominated such as mining vs. female-dominated such as media), and team type (small newly formed vs. large established). At the same time, we considered other dimensions that are salient to differentiate Chinese organizations, such as ownership (private, state-owned, publicly listed, and foreign-invested) and location (Beijing vs. Shanghai). As shown in Table 3, our final sample consisted of 38 teams in nine companies located in two megacities of China, Beijing and Shanghai. Five companies were in the finance industry but in different businesses, including banking, insurance, private equity, and technological finance. Two companies were in the information technology industry, one was in the multi-media industry, and the remaining one was in the mining industry. The scale of these companies, in terms of employee numbers, ranged from 30 to more than 100 thousand employees. Among these companies, one was state-owned, two were publicly listed, two were foreign-invested, and the remaining four were private.

We recruited participants through convenient sampling, including alumni and collaborators of the first and second authors, as well as friends and colleagues of these alumni and collaborators. Our focus is on team diversity, therefore, we selected participants who are working in a team, have worked in a team before the current position, or who have observed or heard about the experience of working in teams. Based on existing team research, we defined that work teams were composed of two or more members, worked towards a common goal, and had a certain degree of interdependence (Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006). Though we expected teams to, at least, have variations on surface-level attributes, such as gender, age, and province, we interviewed participants we could access and reported answers based on their own experience or observations. We invited all members of the interviewed teams to participate in our interviews whenever possible. We retained data from interviewees who shared third-party observations of other teams, even if the interviewees’ current working team has only one member. As shown in Table 4, we interviewed a total of 92 employees from 38 teams. On average, we interviewed about 10 individuals from four teams in each company. Interviewees were between 22 and 49 years old, with an average of 30.87 years old; 43.48% were male; 60.87% had a bachelor’s degree, 30.43% had a master’s degree, and 11.96% received their highest degree from overseas educational institutions. Interviewees came from 26 out of 34 provinces, municipalities, and special administrative regions in China. Most interviewees (66.30%) grew up in cities. All participants spoke Putonghua and 36 (39.13%) of them indicated that they could speak one more Chinese dialect other than Putonghua.

Four interviewers conducted these interviews. One of them is from Hong Kong, one is from the United States, and the other two are from Mainland China. To facilitate the communication between interviewers and interviewees, these four interviewers were grouped into two groups of two and at least one interviewer from Mainland China was involved in each interview. All interviews were conducted on-site at the participating companies. To encourage participants to speak freely and to minimize concerns of peer judgment, we arranged individual interviews whenever possible. Interviews were conducted in closed rooms and we assured confidentiality. We had the interviewees’ consent to tape-record before we started the interview. For interviewees who have concerns about recording, interviewers took notes on site. In total, we had 55 interviews that were tape-recorded with permission, lasting from 25 to 95 min (mean of 52), and six interviews that were recorded based on interviewers’ notes. With a total of 61 interviews, 46 (75.41%) interviews were conducted individually, while the remaining 15 (24.59%) interviews involved two or more participants. We numbered these 61 interviews and cited them when direct quotations were provided in the following sections.

We collected data through semi-structured interviews and the list of questions could be found in the APPENDIX. During the interviews, we asked open-ended questions and invited interviewees to respond based on their own experiences or those of their friends. We adopted two interviewing approaches. The first approach was inductive, through which we asked interviewees to describe “important events”, especially “conflict” or “disagreement” (分歧/不同意见/冲突) that had influenced the communications and collaborations among team members and to describe the attributes of fellow team members involved in these events. We asked questions such as “can you think of a time when there was a disagreement in your team?” and “who is against whom in the conflict?” Not surprisingly, when interviewees were required to describe conflict or disagreement in their current team, no matter whether they are alone or with one or more team members, they only shared cases related to tasks rather than people. Therefore, we also encouraged them to share examples that happened in their previous companies or that they heard from others. This method effectively reduced interviewees’ concerns and made them more willing to share cases related to team diversity. The second approach was deductive, through which we told participants the definition of team diversity (多样性/多元化/差异) and asked interviewees to directly describe the types of diversity in their teams and how they perceive the effect of team diversity on team processes and outcomes.

After identifying diversity attributes that are salient to Chinese employees, we further investigated the mechanisms through which these attributes impact teams. Specifically, we explored whether team diversity could also relate to group conflicts among Chinese employees because extant diversity research has documented that diverse teams are more likely to experience conflicts, including both task and relationship conflict, due to identity differences and information heterogeneity (e.g. van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). We expected that when interviewees talked about conflicts, we could ask them to identify the causes of these conflicts and determine whether these causes are related to diversity. We specifically tried to understand whether team diversity relates to conflicts, how conflicts appear in work teams, and the impact of team diversity and conflicts on team outcomes. Simultaneously, we tried to understand the role of leaders in handling team diversity and managing the team.

Data analysis

Upon transcribing the interview recordings and translating them into English, our analysis unfolded in two stages. In the first stage, we extracted, coded, and counted the team diversity attributes mentioned by interviewees when they responded to questions. Diversity attributes that are frequently articulated by interviewees are considered to be of high importance to the participants. We also asked interviewees whether they think diversity could influence their collaborations in the team and whether team diversity is an advantage or a disadvantage. We summarized the interviewees’ answers to these questions to address our research questions.

In the second stage, we first read and coded one or two interviews independently, then met to compare codes line by line, resolved discrepancies, and refined the themes. We iterated the reading, coding, and discussing process on 10 interviews and generated a preliminary coding scheme that we used to code the remaining 51 interviews separately. We used NVivo to code participants’ expressions into themes and to organize the relationships of themes (Langley & Abdallah, 2015; Locke, 2001). Following the grounded theory coding procedure, we coded interviewees’ answers to questions related to the influence of diversity on performance through team processes, mainly team conflict, as well as the role of leaders in each stage, then summarized the main themes and discovered the relationships between these themes (Gioia et al., 2012).

Results

Team diversity in Chinese organizations

Does team diversity exist in Chinese organizations?

In our interviews, we defined team diversity as any differences that interviewees could recognize between employees, including surface- and deep-level attributes. Our interview data showed that most of the interviewees (72.13%) noticed a presence of team diversity in organizations, a small percentage of them (4.92%) reported no team diversity, and the remaining (22.95%) did not directly comment on this issue. In other words, even though race may not be a salient diversity attribute in the Chinese workforce, as compared with North America and Europe, Chinese employees still perceive team diversity in their organizations.

Is team diversity important in Chinese organizations?

We found that a sizable proportion (45.90%) of interviewees considered team diversity to be desirable. Some interviewees (9.84%) had a neutral view toward team diversity, and only a small percentage evaluated team diversity negatively (3.28%). The remaining did not comment on this issue. Among those with a positive view of team diversity, a sizable proportion (39.34% of the total) wanted to see a greater level of diversity in the team. For instance, Chinese employees in our study commonly believed in the benefit of diversity in facilitating new idea generation and learning.

“It’s good to have some differences because in this case, the members might think differently. And they might come up with different ideas sometimes.” [29]

“I think diversity can bring us into contact with something we don’t usually have contact with. Then we can know more, or perhaps we can learn more.” [49]

They thought that the team as a whole benefited more when the diversity attributes were balanced, which is consistent with the Chinese philosophy that values balance and longevity.

“They (diverse employees) can learn from each other. (It is) good for the collective performance.” [41]

“As your team rolls, diversity is good because it’s like an ecosystem and it actually balances itself.” [53]

Some interviewees considered team diversity neutral or considered its effect to be contingent upon the context of the team, such as task characteristics or goal alignment.

“In this team, the operation is only policy execution. In this circumstance, we are trying to keep people with the same idea with the same view.” [25]

“Everyone complements each other. When people work in a good direction, this kind of diversity is good. At this moment, I think we are not working towards the same goal. It’s not a very good thing.” [22]

As a whole, our findings showed that almost half of the interviewees did think that team diversity is important to the team and organizational performance.

Salient team diversity attributes in Chinese organizations.

One of our research questions is whether diversity attributes commonly examined in existing studies are important to Chinese employees. Our interviews provided us with rich information on salient diversity attributes among Chinese employees. Consistent with the extant literature on diversity (Harrison & Klein, 2007), we found that demographics, such as gender, age, education, and work tenure were salient diversity attributes among Chinese employees. Besides surface-level attributes, interviewees emphasized the importance of deep-level attributes, such as personality and working experience. These deep-level attributes received relatively less focus in the extant literature, despite their importance (Harrison et al., 1998, 2002). Besides, we discovered several unique diversity attributes that are important to Chinese employees, for instance, provincial background, dialect (Gong et al., 2011, 2012), and local versus overseas education. Also, we investigated interviewees’ perceptions of the importance of each diversity attribute. In specific, we counted the percentage of interviewees who articulated the presence of the diversity attribute and also considered the attribute to be important. As shown in Table 5, we found that personality (39.34%), age (22.95%), professional background (21.31%), work experience (16.39%), and provincial background (11.48%) were most likely considered important by interviewees. Surprisingly, these interviewees tended not to consider gender diversity to be important (6.56%), even though this attribute was the most often examined one in extant studies as shown in Table 2.

Next, we will discuss in detail the salient and important diversity attributes among Chinese employees and provide related citations in Table 6. They include both surface-level and deep-level diversity attributes.

Personality.

Personality is the most prominent and widely mentioned diversity attribute among our Chinese interviewees. More than half of the interviewees (63.93%) commented on this diversity attribute; many of them (50.82% of the total) reported personality differences in the work team, while some (13.11% of the total) reported having little personality differences in the team. However, interviewees used personality as a broad term to describe individual characteristics other than surface-level attributes. Some interviewees’ definitions of “personality” matched the dimensions of the Big Five Personality, but some were referring to work-related behaviors or motivations. For instance, one interviewee said:

“The first type of person is more reliable. However, the second type has its own thought, and at the same time, they are willing to follow the ideas of leaders. The third type refers to people who have their own thought but don’t take the opinion of leaders.” [12]

Among various personality dimensions, conscientiousness was the most salient one among the interviewees. The salience of conscientiousness as a diversity attribute in the work context resembles existing meta-analytical research findings which showed that conscientiousness is a consistent predictor of job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1991). In our study, interviewees often commented on others’ reliability at work and conformity to rules, which are related to conscientiousness [refer to Table 6, Personality Diversity, Conscientiousness]. Many interviewees also differentiated people who were attentive to details from those who were not [refer to Table 6, Personality Diversity, Detail Oriented]. Beyond conscientiousness, interviewees also noticed other aspects of differences in personality, such as extraversion, openness to experience, and agreeableness [refer to Table 6, Personality Diversity, Other Types of Personality].

Age.

Age difference and generation gap were the second most commonly mentioned diversity attributes among interviewees. Many interviewees (60.66%) commented on age diversity in their team, 47.54% of them reported having age diversity in their team, 22.95% thought age diversity was important, and 13.11% reported having little or no age diversity.

While age diversity is prominent to both Chinese and their counterparts in Western societies, interviewees in our sample can be surprisingly precise when discussing age differences. Quite a number of interviewees can quote the exact year of birth of their colleagues. For example, one interviewee mentioned that

“team members in retail banking are even younger. Some are 1987, 1988, from 1985 to 1989. The oldest team member in corporate banking is 1963” [13].

Such precision in discussing age diversity is feasible partly because the Chinese generally place a lower emphasis on the privacy of personal information relative to some Western counterparts. One interviewee explained that

“in China, we don’t hide candidates’ personal information when we see their CV or their application forms” [25].

Experiencing a rapid economic and societal change in China in the recent decade, many interviewees mentioned how differences in age and generation are associated with individuals’ upbringing and values. Among interviewees who reported having age diversity in the team, nearly half of them considered age diversity in the work team to be important [refer to Table 6, Age Diversity, Age and Generation]. At times, the combination of age and gender effects may single out certain team members, such as female employees who are at the age of giving birth [refer to Table 6, Age Diversity, Age and Gender], which was considered to be related to employees’ behaviors and motivations in the workplace.

Province.

The provincial background is a unique diversity attribute in China. Provinces in China are the highest level of administrative divisions in China. The concept of ‘province’ in the People’s Republic of China has some resemblance to the concept of ‘states’ in the United States. Each province has some degree of autonomy in local administration and financing, and each of them has non-overlapping geographical boundaries. In Western diversity research, the birth and upbringing from a different administrative division within a country were seldom considered to be a key attribute of diversity. Meanwhile, in our study, 42.62% of interviewees considered provincial background to be a source of diversity in the work team. Only 3.28% of interviewees reported having little to no provincial diversity in the team. The remaining 54.10% of interviewees did not comment on this attribute. For example, one interviewee said,

“Because people are from different locations in China. China is big itself. If you come from different provinces, you can come with your characteristics there.” [25]

The People’s Republic of China consists of 34 provincial-level administrative units, and the provincial diversity in the population of each provincial-level administrative unit differs. When analyzing the statistics of the Chinese workforce, we suggested that diversity is an important topic for Chinese organizations. Based on available data from the 2020 Population Census of China, National Bureau of Statistics, we also compared provincial workforce population diversity in gender and education. As shown in Fig.1a and b, diversity in gender and education varies across different provinces and regions. Megacities like Beijing and Shanghai attract people from all over the nation to explore job opportunities, thus having high provincial diversity. As an increasing number of immigrants move into the big cities, the difference between local citizens and immigrants becomes salient. Since people who are born in and grow up in top-tier cities and provinces in China enjoy a much higher standard of living in the recent decade, differences in social-economic status may underlie provincial differences.

“There is a problem with people from Beijing, local ones. They don’t have much pressure on earning a living. They have their own house. They have a home. Then maybe they are not so determined to work.” [013]

Interviewees often intertwined local versus non-local with social-economic status in their description, which led to only 8.20% of interviewees mentioning differences in socio-economic status directly when discussing team diversity.

We believe that provincial background is particularly salient in China due to a couple of reasons. First, people who grow up in different provinces in China can sometimes have different dialects and cuisine. Such differences in the way of living can flourish the growth of sub-cultures, and this can be the underlying roots that make the province a salient diversity attribute. Second, income inequality across provinces is a significant problem in China in the last decades. People growing up in coastal provinces in the East enjoy a much higher standard of living partly due to the geographic advantage of staying near the coast and partly due to the Chinese government’s strategic decision to boost the economic growth and advancement in those regions. As such, differences in the provincial background can also be associated with large differences in earnings and wealth (Gong et al., 2011).

Interestingly, we observed that provincial diversity was more salient in Shanghai than in Beijing. In China, Shanghainese is commonly considered to have a strong sense of identity, partly because of Shanghai’s long history of being a prosperous city, and its strong prevalence of a local dialect that is different from the official language of Putonghua.

“From my point of view, if all people are from Shanghai, one thing is not that good is that if most of the people from a local place and other people will feel isolated when they talk in the Shanghai dialect. And then they talk in the same way, or they think in the same way because I heard some stories from some friends. Maybe they (Shanghainesses) don’t do this on purpose, but it makes people think in that way.” [60]

Education.

Education is a diversity attribute that has both common and unique features in China as compared with Western studies. The salience of this attribute in China is reflected in both the quantity and quality of comments shared by interviewees. In terms of quantity, over half of the interviewees (52.46%) commented on team diversity in education; many of them reported having education differences in a team (40.98%) and the remaining (11.48%) reported having similar educational backgrounds among members in a team. In terms of quality, Chinese interviewees in our study differentiated the educational background of their colleagues in great detail, which is unique in China. Studies on demographic diversity conducted in Western culture typically investigated the difference in the educational background (e.g. major or degree) and education level (e.g. Ph.D., master’s degree) (Bell et al., 2011). Differently, our Chinese interviewees commonly quote colleagues’ educational background (e.g. accounting, economics), level of education, location of school (e.g. local versus overseas), and prestige of school (e.g. famous or not) [refer to Table 6, Education Diversity, Prestige of School, and Location of School].

The location of the school is uniquely salient to the Chinese. The strong emphasis on education and schooling in the Chinese culture might have contributed to the Chinese’s attention to colleagues’ educational backgrounds. Moreover, the Chinese seem to consider studying in a local school to be categorically and practically different from studying in overseas schools. The local Chinese versus the overseas education system was often associated with differences in knowledge structure, the logic of thinking, and attitudes towards work. Extant studies have discovered that returnees from abroad could bring changes in enterprise norms and practices (i.e., Lin et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2020), but few studies have investigated how they could work in teams with employees who graduated from local schools.

Gender.

Gender is a commonly discussed attribute in the interview, as we proactively ask interviewees “what diversity do you have in your work team”. Nearly half of the interviewees (49.18%) talked about gender diversity in the team, and 37.70% (of the total) reported diversity in their current team. However, only 6.56% of Chinese interviewees consider this attribute important. This is surprising as people in Western societies tended to pay attention to gender diversity. In addition, when gender difference was being discussed, many Chinese interviewees confounded it with other dispositional characteristics or behavioral differences, which appeared consistent with prejudice towards gender roles in Chinese society [refer to Table 6, Gender Diversity, Gender Difference]. A few Chinese interviewees experienced no gender diversity in the team and they seemed to seek a higher level of gender diversity [refer to Table 6, Gender Diversity, Seek Gender Diversity].

Work experience.

Work experience is another attribute with some unique features in China. The differentiation between working in local or state-owned companies versus working in foreign companies was particularly salient for the Chinese, and this diversity attribute was not studied in Western societies. Not only work experience outside China was considered to be different from work experience inside China. Many interviewees clearly differentiate work experience at local state-owned enterprises versus work experience at foreign companies located in China. An interesting implication is that the difference in work experience is in kind rather than in degree and this is likely due to different organizational cultures, human resource management systems, and leadership styles in China [refer to Table 6, Work Experience Diversity, Organization Type]. On the other hand, consistent with extant literature in western societies, the Chinese would also differentiate individuals by years of work experience. The difference in years of work experience can also be considered to indicate differences in work capability [refer to Table 6, Work Experience Diversity, Have Work Experience or Not]. Overall, work experience is a moderately salient diversity attribute in China. Around 38% (37.70%) of interviewees mentioned this attribute. Some of them (34.43% of the total) noted a difference in work experience within the team, while a small amount of them (3.28% of the total) did not report work experience differences in their teams.

Work tenure.

Work tenure is found to be a moderately salient diversity attribute among Chinese employees. In our interviews, 32.79% of interviewees mentioned this attribute, and all of those who articulated tenure as a diversity attribute acknowledged its presence in their team.

“They are different. The one has worked here for about 6 years as I have. And the intern has just started working here.” [41]

When the team is new, some interviewees would also differentiate tenure by months rather than by years.

“The member who stayed the longest joined last February, but there was only one person. Later in March, I was not the first member, but I took him to our team. Right now, the members are those who have worked here for about 8 months or above.” [38]

As a whole, we found that diversity attributes commonly examined in Western studies were most important to Chinese employees (except gender diversity), while we also identified unique diversity attributes (e.g. province) and subdivisions within an attribute (e.g. local versus overseas school in education diversity) in China.

Working mechanisms of team diversity on team outcomes

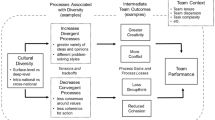

As a sizable number of interviewees considered team diversity to be desirable and some even prefer to have more team diversity, we have no evidence suggesting that discussing team diversity is taboo among Chinese employees. Therefore, we asked interviewees to describe team conflicts and then identified whether the causes of these conflicts are related to diversity. This strategy was proven useful and we discovered diversity attributes that significantly influenced employees. Even from interviewees who were willing to share group conflict, we found that they avoided discussing the negative influences of team diversity on their teams or organizations. Diversity attributes that were related to conflict have been identified and shown in the previous sections of Salient Diversity Attributes in Chinese Organizations. Here based on interviewees’ reports, we identified four major themes related to conflicts and leadership in Chinese work groups and clarified the links between these themes, as depicted in Fig.2, and we will discuss the main findings and theoretical implications for team diversity management in Chinese organizations.

Conflict is common but not in my team.

We explicitly asked participants whether they have experienced conflicts or different opinions in their workgroups. Most participants (49 out of 61 interviewees, 80.33%) mentioned that conflicts happened in their own team or their previous organization. Participants were quite comfortable talking about task conflict. For instance, one interviewee said,

“Yes, we often have different opinions. Because we are in charge of different works, something I understand, but others can’t understand. So when we work together we might have different opinions” [03], and another one said, “We use different methods. When we exchanged our perspectives, we had arguments before.” [06]

However, participants were less willing to talk about relationship conflict. For instance, they may frame the conflict as task-based and avoid making personal judgments, or they may talk over differences in opinion, but are less willing to mention relationship conflicts they have experienced. For instance, one interviewee mentioned,

“There is no personal right and wrong. There is just what these things should be done.” [25]

Rather, they are more willing to talk about relationship conflict they observed in others,

“There are two people, one is male, one is female. They have not been in a really good relationship. They usually argue about work or a lot of issues. Everyone knows that they both are not in good relationships.” [27]

Prevent conflicts from happening.

Sometimes interviewees tried to prevent conflicts from happening from the very beginning because they assume conflicts will damage their relationships with their counterparts and negatively impact team performance. Some interviewees said,

“Usually I would speak out too, but I might not be so straightforward at the beginning, I might, but I believe he understands what I meant, I usually take a gentler approach to talk about it. If I feel like he doesn’t quite get what I’ve said, then I will speak out directly.” [19] Or “If we have any problems, we have to solve them as early as possible. The longer we delay it, the worse it is to everyone.” [22]

Team conflict avoidance.

Although participants mentioned that they experienced or observed team conflicts, they were uncomfortable talking about “conflict”, as they interpreted team conflict mainly as relationship conflict and attributed it as a word with strong negative implications—it is personal judgment toward coworkers and harmful to team collaboration and performance. When we asked them to give us some examples of conflicts, interviewees typically avoid sharing their current experiences, instead, they would rather talk about cases that happened in their previous working companies or were experienced by their friends. For example,

“Interviewer: Have ever you encountered this in this company? Interviewee: I had in my previous company. Interviewer: So you haven’t this in this company? Interviewee: That’s right.” [48]

After realizing this tendency among interviewees, we tried to use more neutral terms, such as disagree (分歧/不同意见) to describe conflict and encouraged interviewees to share more cases that they have experienced, especially those related to diversity. Despite so, some participants still avoided talking about the potential negative impact of conflict on teams.

“I have not encountered that (different opinions) at work. If we do have some cases, then, in fact, the solution of our team is that everyone has to work together.” [31]

Once conflicts happened, one of the strategies interviewees adopted to deal with conflict is to avoid talking about or dealing with conflict but to maintain distance from their counterparts. Just as some interviewees mentioned,

“They have not been in a really good relationship. They never talked, they never communicated. Never, they don’t want to make an effort on this. So in the end, avoid each other.” [27]

Our interview experience coupled with the interview data informed us that conflict, especially relationship conflict, can be a taboo topic to Chinese employees, as it is usually accompanied by negative relationships between members and negative implications to the group or even the organization. Accordingly, diversity attributes that caused relationship conflicts were less mentioned by interviewees. It also implies that diversity attributes that are associated with relationship conflict are taboo topics among Chinese employees.

Leaders in diversity management.

From interviews, we found that even though interviewees thought team diversity is important, they explained that interpersonal dynamics rooted in team diversity can easily be overridden by leadership influence. Interviewees considered leadership to be more important than team diversity because leaders could determine the compositions of team members, in terms of surface-level attributes, such as age, gender, and education, as well as some deep-level attributes, such as personalities and behavioral tendencies, through recruitment procedures, and leaders could take into consideration the relational dynamics among members before allocating them to different positions to work on specific tasks. As such, leaders can influence the likelihood of conflicts by controlling the level of task interdependence among members.

“Although team members have the right to choose who they want to work with, the final decision will be made by Xu and Wang, as they are leaders.” [16]

Leaders’ influence on diverse teams’ processes will be amplified if the leaders prefer dominating rather than empowering team decision makings, thus, members will have little discretion to dispute with others.

“I (as the team leader) will not put team members who have conflicts with each other in the same service area. If I put two team members who always have a diverse opinion on everything or even have a conflict with each other before, the outcome will be much worse.” [12]

Furthermore, group leaders may set detailed task procedures and require strict obedience from members.

Leaders in conflict management.

At the same time, we found that a large proportion of interviewed teams were centralized in decision making, therefore, members were used to deferring to leaders to resolve ambiguities in group tasks, decision making, or collaboration procedures. For example, two interviewees said,

“We don’t have huge conflicts. In fact, our department is small. Basically, the leader will first make the plan and then we just follow it. Basically, the direction is confirmed at first so we don’t have much disagreement.” [10] Or “Normally we discuss first, and then we will explain why we think our ideas are good (to the leader), but normally we will follow what the leader says. He can always give a very valid explanation for his views.” [08]

If leaders provide limited autonomy to team members, members may become demotivated to participate in team decision-making. This prevents conflicts from happening but also inhibits members from contributing their information and knowledge to teams.

“We need to first consider the case and think of a way to solve the problem. Then we can go and report it to the leader. Of course, we need to get approval from the leader first before we can start.” [18] Or “For example, if we all feel that a particular method is good, then we will surely do it according to everyone’s opinions. But if we have quite different opinions, then I (as the group leader) will probably make the decision.” [57]

Leadership and team diversity.

Since members habitually defer to their leaders for decision making and since group conflict is minimized through top-down decision making, we speculate that members may have limited experience in resolving group conflict by themselves even if they belong to a team with a high level of team diversity. Overemphasizing leadership influence while neglecting other factors on team outcomes might be one of the reasons why the topic of team diversity is undervalued in Chinese organizations. We speculate that centralized leadership in Chinese organizations does not only weaken the effect of team diversity on group conflict but also potentially slow down the development of diversity management capability within the team.

To conclude, we found that the conflicts arising from team diversity rather than team diversity itself are taboo topics among Chinese employees. Interviewees were reluctant to talk about the destructive group dynamics within their work teams, such as relationship conflict. Meanwhile, conflict is one of the most common and important mechanisms through which team diversity impacts team outcomes (De Wit et al., 2012). Interviewees’ reluctance towards talking about team conflict might explain why we did not gather much data on the negative influences of team diversity through interviews. Our interview data also revealed that Chinese employees are inclined to take leadership as omnipotent in preventing and in dealing with team conflict. If Chinese employees attribute team conflict to poor leadership rather than to team diversity, they may underscore the importance of team diversity. As such, we speculate that the importance of team diversity may be overshadowed by the importance of leadership in Chinese organizations.

Discussion

We initiated this study from the observation that team diversity research in Chinese organizations has attracted very little research attention (as shown in Table 1). To understand why this happens, we initiated a qualitative study to explore whether diversity is an important topic in Chinese organizations and if it is, what diversity attributes are significant to Chinese employees working in teams and how team diversity could impact teams. Results from our interviews showed that most interviewees reported that they observed or experienced team diversity (72.13%) in their work teams, and a sizable proportion (45.90%) of participants considered team diversity to be important and desirable. Studying diversity attributes that were salient to Chinese employees, we found attributes similar to those in Western studies as well as unique ones in Chinese organizations. We also found that interviewees avoided talking about the potentially detrimental effects of team diversity, especially relationship conflicts, but they emphasized the role of leaders in managing team diversity and team conflict. In the following sections, we will discuss the contributions of our study to the team diversity literature, as well as the limitations and directions for future research.

Contributions to team diversity research

Our research adopts a new approach to studying team diversity. Although team diversity study has a long history in North American and European communities and has attracted much attention from scholars, team diversity is often treated as an objective phenomenon grounded in team composition and measured through composite indices (Harrison & Klein, 2007). Few studies have systematically examined the importance of each diversity attribute from the team members’ point of view, nor contextualized the relevant importance of attributes in different cultures and economic systems. In recent reviews of diversity literature, scholars repeatedly emphasize the importance of “context”, and call for research on understanding how context affects the salience, meaning-making, and content of diversity attributes (Joshi & Neely, 2018; Roberson, 2019). Responding to these calls, our study takes an inductive approach to generate a map of diversity attributes in work teams of Chinese organizations, which enables us to understand the meaning of team diversity and the relative importance of each diversity attribute in the eyes of Chinese employees.

We found some support for the generalizability of diversity attributes to the Chinese cultural context. We found that demographic attributes commonly studied in current diversity literature applied to Chinese employees too, such as gender, age, educational level, work tenure, and functional background. However, to our surprise, very few interviewees considered gender diversity as important. We believe that local societal and work contexts could have partly shaped the salience of gender diversity. Despite that traditional Confucianism culture favors males over females, the one-child policy carried out in the last 30 years provides females more opportunities for higher education. The statistics from the Census Bureau in China (2020) showed that the population of males versus females with College or above education is around 51–49%. In this study, interviewees are mostly knowledge workers in the entry to middle levels, in which gender diversity is common and gender distribution is balanced. This may have reduced the importance of gender as a diversity attribute.

While context can influence the salience of diversity attributes, we found that context itself can also serve as the content of diversity attributes. Our findings revealed that local versus overseas education (Lin et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2020) and work experience were salient among Chinese employees, because such differences were associated with underlying differences in personal values, cognitions, and behaviors. As discussed earlier, interviewees informed us that people who were educated in Western countries or exposed to Western-style working environments differ from people educated in China in terms of knowledge structure, way of thinking, and attitudes towards work. People who have received education from overseas institutions or were exposed to Western-style ideas were more open to expressing different ideas and believed in meritocracy, while people who received education in local institutions were concerned more about collective goals and group harmony (Chen et al., 2016).

Existing literature seldom highlights local versus overseas influences on education and work experience as diversity attributes, yet such distinction might be salient to people in rapidly growing or developing countries. In these countries, an increasing number of people study abroad and return to their home country for work (i.e. overseas returnees), in which some may experience reverse culture shock when they find that existing company practices in the home country are different from those overseas. Researchers interested in studying team diversity in rapidly growing or developing countries may consider exploring how such factors can influence group dynamics and work outcomes when overseas returners worked with locally trained employees in the same team. Besides, further research will be needed to tease out the effect of local versus overseas differentiation in education and work experience from the effect of income differences. In Chinese organizations, overseas returnees often enjoy better compensation packages than their local counterparts. At the same time, people who studied overseas usually come from families with higher socioeconomic status as compared with those who studied locally. Such confounding impacts need to be investigated in future studies.

Our study discovered a new diversity attribute, “province”, that is unique in Chinese employees. Such a within-country institutional geographic-related attribute was rarely studied in extant team diversity research. For example, despite the fact that the United States has a large landmass and is made up of numerous states with rather independent state governments and local legislatures, the place of birth or upbringing by states was seldom examined as a salient diversity attribute. Meanwhile, we found that province can be a salient diversity attribute in Chinese employees, and we believe this can be related to provincial differences in dialect, cuisine, and living standard. We speculate that regional division may also be a salient diversity attribute in countries that have clear differences in regional culture, language, and the standard of living across regions. Findings from our study contribute to the existing literature by indicating that sub-cultural and institutional differences can be unique and salient diversity attributes.

In addition to identifying new diversity attributes, our study offers new insight into how employees make sense of diversity attributes, and how they relate surface-level attributes with deep-level attributes (Harrison et al., 1998). For instance, we found that Chinese employees believe that surface-level diversity in local versus non-local life experiences is associated with deep-level diversity in values and ways of thinking. Moreover, although previous studies have pointed out the importance of deep-level diversity attributes, few studies have explored these attributes (for an exception, see Harrison et al., 2002). We found that Chinese employees consider personality, a deep-level attribute, to be most important. This resonates with meta-analytical research indicating that deep-level attributes, as compared with surface-level attributes, have a stronger relationship with team performance (Bell, 2007; Bell et al., 2011). We also noticed that interviewees in our study attended to tiny details of surface attributes, such as year of birth and prestige of schools, to be salient and meaningful. All these findings reinforce the value of studying deep-level diversity, as well as understanding how employees make sense of diversity in their own eyes.

Fourth, we found that participants treated the negative impact of group diversity (specifically group conflict) as taboo and avoided talking about them in the interviews. The categorization-elaboration model (CEM, van Knippenberg et al., 2004) proposed that diversity could influence group performance mainly through two paths: The beneficial one is the elaboration of task-relevant information, and the detrimental one is the social categorization and identity conflicts between subgroups. Interviewees in our study emphasized the information benefits of diverse employees but avoided conflicts with others or even were hesitant to talk about conflicts in their teams. It implied that other than the two main working mechanisms that have been identified in existing diversity research, new mechanisms may exist in Chinese employees, such as avoidance of communication and biased information sharing. Therefore, future research needs to examine other potential mechanisms through which diversity influences team performance.

Furthermore, we found that centralized leadership can potentially serve as a contextual factor influencing the impact of team diversity in the Chinese work context via altering the salience of team diversity and changing team dynamics. On one hand, Chinese leaders could determine team compositions, especially compositions of surface-level demographic attributes, which means that they could intentionally design the type and extent of group diversity. On the other hand, their managerial behaviors could manage or suppress conflicts that occur due to diversity, especially when these leaders have been socialized with a cultural emphasis on harmony (Chen et al., 2015, 2016). When leaders dominate group decision processes, there is less space for group members to express different opinions or have conflicts with each other. In other words, strong centralized leadership can potentially weaken both the positive and negative effects of team diversity on team processes. When team members have little power to make any critical decision within the team, “team diversity” may become a less salient and important issue for them.

Limitations and future research

We examine team diversity in Chinese organizations through reviews and in-depth interviews, which has limitations too. First, our study takes an inductive approach to generate a map of diversity attributes in Chinese organizations to understand the meaning and relative importance of diversity attributes as perceived by Chinese employees. Although team diversity study has a long history in North American and European communities and has attracted much attention from scholars, few studies have justified the importance of each diversity attribute systematically, nor contextualized the relevant importance of attributes in different cultures and economic systems. Using an inductive approach in our study enables us to help fill this gap by investigating an original phenomenon from scratch. However, this study is only a first step to providing preliminary answers, and we call for future research, including both well-designed qualitative and quantitative studies to leverage the advantages of different research methods to demonstrate the “prevalence, generalizability and calibration” (Lee, 1999, p. 38) of our findings.

Second, while interviews may potentially be biased by the social desirability effect (Ones et al., 1996), we minimized this bias through following recommended practices, such as using enclosed rooms, assuring confidentiality, and asking neutrally-phrased questions. Research on the effect of social desirability pointed out that participants were more likely to introduce the good side of their organization but hide or beautify the negative side (Ones et al., 1996). During the interview, we noticed that interviewees were less likely to talk about negative influences of group diversity or to disclose relationship conflicts among group members compared with positive influences. In our study, we noticed the presence of the social desirability effect by comparing interviewees’ disclosure of team conflict in their own team with conflict in other teams or organizations. Future studies could consider using other research designs, such as off-site and strictly one-on-one interviews, to further weaken the influence of social desirability from participants.

Third, an observation from the review in Study 1 is that only a third of studies on diversity (32.6%, 14 out of 43) investigated diversity in the team context, but others focused on the attributes of individuals, such as leaders’ Confucianism (Ji et al., 2021) and communism (Marquis & Qiao, 2020), or the leader-follower dyads, such as dyadic similarity in growth need (Huang & Iun, 2006) and dialect (Gong et al., 2012), indicating that the attributes of important individuals, such as team leaders, have been recognized in existing studies, but less attention has been paid to the team-level configuration of all team members. This finding is consistent with the findings from Chen and colleagues (in press) who reviewed diversity research in the Asia-Pacific region. The reasons behind this could be an interesting question for future research. At the same time, though we tried our best to invite all members of the interviewed teams to participate in our interviews, we did not make it because some team members are out on business trips or are in important tasks at the time we visited the company. Therefore, we cannot calculate the diversity strength for each interviewed work team (as shown in the fourth column of Table 4), which prevents us from making a comparison of interviewees from different teams, but is worth more studies in the future.

Finally, generalizability may be a limitation of our study. Our study examined companies located in Beijing and Shanghai. More than 90% of our interviewees had a bachelor’s or above degree, and they were only from Beijing and Shanghai, but the statistics from the Census Bureau in China 2020 suggest that only 15.5% of the Chinese workforce have a college or above degree. It means these companies may not reflect the real employment situations in Chinese organizations located in small cities or villages. As shown in Fig.1a and b, the strengths of diversity in gender and education vary across provinces within the country. Future research may enlarge the geographical scope of samples to decrease potential range restrictions. Nevertheless, our samples include companies diverse in scale, ownership, and industry. Besides, participants in our sample were mostly knowledge workers. Future research may include other categories of laborers, such as blue-collar workers, semi-skilled, or clerical workers, to increase the generalizability of their findings.

Conclusion

We conducted a qualitative study to explore whether diversity is an important topic in Chinese organizations and if it is, what diversity attributes are significant to Chinese employees working in teams and how team diversity could impact teams. Responses from interviewees showed that team diversity was salient to Chinese employees, and that diversity attributes prevalent in Western studies (e.g. gender, age, and professional background) were salient and meaningful in Chinese organizations. Meanwhile, our findings also revealed a few major unique contextual effects on team diversity. First, we identified unique diversity attributes in Chinese organizations, such as province, dialect, and overseas experience. Second, we noticed that talking about the potentially detrimental effects of team diversity, especially relationship conflict, could be taboo in China. We speculate that such taboo might create challenges for researching the negative impact of team diversity. Third, we found that centralized leadership in Chinese organizations could alter the salience of team diversity and change team dynamics. As a whole, our study responded to the call for examining how contextual factors influence the content, salience, and meaning-making of diversity attributes (Joshi & Neely, 2018; Roberson, 2019). Our interview-based study examined Chinese employees’ subjective views on the salience and meanings of diversity attributes, thus complementing extant literature that often mathematically assumed equal salience among diversity attributes. We hope our inductive research can help encourage scholars to attend to the local perspectives and experiences of team members in team diversity research.

References

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26.

Bell, S. T. (2007). Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 595–615.

Bell, S. T., Villado, A. J., Lukasik, M. A., Belau, L., & Briggs, A. L. (2011). Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: a meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3), 709–743.

Byrne, D. (1971). The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic Press.

Chatman, J. A., Polzer, J. T., Barsade, S. G., & Neale, M. A. (1998). Being different yet feeling similar: The influence of demographic composition and organizational culture on work processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4), 749–780.

*Chen, S., Fang, H. C., MacKenzie, N. G., Carter, S., Chen, L., & Wu, B. (2018). Female leadership in contemporary Chinese family firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(1), 181–211.

Chen, T., Leung, K., Li, F., & Ou, Z. (2015). Interpersonal harmony and creativity in China. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, 648–672.

Chen, C. C., Ünal, A. F., Leung, K., & Xin, K. R. (2016). Group harmony in the workplace: Conception, measurement, and validation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33, 903–934.

Chen, X., Zhu, L., Liu, C., Chen, C., Liu, J., & Huo, D. (In press). Workplace diversity in the Asia-Pacific region: A review of literature and directions for future research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management.

*Cheung, G. W., & Chow, I. H. S. (1999). Subcultures in Greater China: A comparison of managerial values in the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 16(3), 369–387.

*Cumming, D., Leung, T. Y., & Rui, O. (2015). Gender diversity and securities fraud. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1572–1593.

De Wit, F. R. C., Greer, L., & Jehn, K. A. (2012). The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta–analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 360–390.