Abstract

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) model is the gold standard in community psychiatry serving people with severe mental illness. With its outreach-based design, the pandemic has profoundly affected the operations and functioning of ACT. The Dartmouth ACT Scale (DACTS) provides a standardized comprehensive and quantitative way to evaluate ACT quality. Results could inform nature of impact and identify areas for improvement. Current online survey used DACTS during the pandemic in April-May 2021. Clinical and administrative leadership of the 80 ACT teams in Ontario, Canada cross-sectionally rated ACT quality one-year pre-Covid (2018–2019) and one-year post the start of Covid (2020–2021). The overall pre-Covid Ontario ACT DACTS fidelity was 3.65. The pandemic led to decreases in all domains of DACTS (Human Resources: −4.92%, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.08–0.27]; Organizational Boundary: −1.03%, p < 0.013,95%CI [0.01–0.07]; and Nature of Services: −6.18%, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.16–0.26]). These changes were accounted by expected lower face-to-face encounters, time spent with clients, reduction in psychosocial services, less interactions with hospitals and diminished workforces. The magnitude of change was modest (−3.84%, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.09–0.19]). However, the Ontario ACT pre-Covid DACTS was substantially lower (−13.5%) when compared to that from a similar survey 15 years ago (4.22), suggestive of insidious systemic level loss of fidelity. Quantitative fidelity evaluation helped to ascertain specific pandemic impact. Changes were significant and specific, but overall relatively modest when compared to the larger system level drop over the last decade. There is both evidence for model adaptability and resilience during Covid disruption, and concerns over larger downward drift in ACT fidelity and quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is a well-established, evidence-based treatment model for people with serious mental illnesses (SMI) in a community setting (Bond et al., 2001; Stein & Test, 1980). As part of the community mental health services, ACT is highly effective in reducing illness burden, and is often described as the “gold standard” of treatment in community psychiatry (Dixon, 2000). One of its key innovations as a model is delivering treatment and care through outreach and active engagement in the community. Social distancing and minimizing personal contact as mandated by the Covid-19 pandemic has had fundamental impact on how ACT services were delivered. Few specific guidelines existed to guide ACT teams in responding to disruptions at this large scale (Druss, 2020), putting the already highly vulnerable SMI populations at further risk (Kozloff et al., 2020).

Although there are some general and early reports of the pandemic’s impact on ACT and community psychiatry (Couser et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2021; Neda et al., 2022), relatively little is known regarding how and to what extent the quality of community treatment models like ACT have been affected. ACT utilizes a highly coordinated multi-disciplinary team, involving psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, addictions workers, peer support workers, and others. Regular daily team meetings, after-hours on call system, and serving patients in their milieu, using outreach, community and home visits, and providing intensive psychosocial services are at the core of its service model (Bond et al., 2001). There are various aspects of this complex service model that benefit from standardization, which in turn helps to gauge its service quality and level of functioning. The health of the ACT model is also a reflection of the quality of the community psychiatry sector as a whole. Historically, ACT has utilized model fidelity instruments such as the Dartmouth ACT Scale (DACTS), which outlines in detail the structures and functions of this service model, and sets the standard (Teague et al., 1998). Research also shows good correlation between high program fidelity and patient outcomes (Bond & Salyers, 2004). DACTS has three main domains: Human Resources (i.e., caseload ratios, clinician composition, turnover rates, etc.), Organizational Boundaries (i.e. intake and discharge criteria, scope and division of clinical responsibilities, responsibility for crisis services, 24-hour on call system, etc.), and Nature of Services provided (i.e. engagement approaches, medication adherence monitoring, and peer support) (George et al., 2009). Studying these domains provides a good opportunity to understand the impact of the pandemic on community psychiatry and operations of ACT in a comprehensive, standardized and quantitative way.

Since 1998, the province of Ontario, Canada, with a population of 14.8 million, has developed over 80 ACT teams, forming the core of the most intensive services for people with SMI (George et al., 2009). Most Ontario ACT teams were considered mature, stable, and with good fidelity (George et al., 2010). During the pandemic, Ontario has registered 1,616,240 Covid-19 cases and 16,488 deaths as of April 29, 2023 (Public Health Ontario, 2023). While the current pandemic is easing to a substantial degree, future recurrence remains a real challenge (Moore et al., 2020). Using DACTS, we surveyed the ACT teams in Ontario to understand the level of ACT quality before and after the pandemic. We aimed to learn the impact of the pandemic on ACT, and the timely evaluation could inform current quality of the provincial ACT teams, pandemic related program adaptations, areas of concern, and help to prepare for future major disruptions.

Methods

The current study on the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on team structures and functioning of Ontario ACT teams is part of a larger study that examined Covid-19 related adaptations and innovations in community psychiatry in Ontario. The research team developed the current ACT fidelity survey modeled on a previous study by George and colleagues in 2007–2008, who surveyed ACT team clinical and administrative leaders in Ontario using DACTS through a self-report approach (George et al., 2010). While the standard of fidelity evaluation using DACTS is done on-site by trained assessors, research shows self-reported DACTS assessment could produce reasonably reliable results (McGrew et al., 2013). Other successful self-reported fidelity surveys are found in measuring Individual Placement and Support Program (IPS) (Margolies et al., 2018), and Dual Diagnosis Capability in Mental Health Treatment (DDCMHT) (Covell et al., 2021). While non-ideal, experts also see a role for self-reported DACTS in some circumstances and for quality improvement purposes (Bond, 2013). Beyond these, the current study’s self-reporting approach is also related to the restrictions placed on time, budget, and in-person contact related to the pandemic. The original published version of DACTS was used for the survey using an online platform hosted by SimpleSurvey (SimpleSurvey.com).

The DACTS is a 28-item measurement, where each item is rated on a 5-point scale, with 1 being not implemented to 5 being fully implemented (Bond & Salyers, 2004). The 28 items are organized into three domains: Human Resources (11 items), Organizational Boundaries (7 Items), and Nature of Services (10 items) (Bond & Salyers, 2004). We modified 3 relevant questions (i.e. Human resources, question 2; Nature of services questions 4 & 5) to include “virtual” care in clinical contact time to capture adaptations made during the pandemic. (See Table 1 for details of the 28 items and the 3 domains of DACTS). The survey took typically 20–40 min to complete.

The study targeted the clinical and administrative leaders of the 80 ACT teams in Ontario, who belong to the Ontario Association of ACT and FACT (Flexible ACT) (OAAF, 2022), the sole provincial organization that engages in standard and quality improvement, professional education, and political advocacy. The OAAF maintains an active mailing list that reaches 232 individuals, who are made up of 2 to 4 members from each of the 80 ACT teams in Ontario. The mailing list members are typically team leaders, team managers, or senior members. Each potential participant was sent a copy of the study information and consent form, and a link to the SimpleSurvey on April 12, 2021. Participants were those who have worked on the team for at least 3 or more years and were asked to use their best recall and judgment, and any relevant objective information available to rate the fidelity of the team during the one-year period before the pandemic (i.e. 2018–2019), and the most recent one-year period post-pandemic (i.e. 2020–2021). Four reminder emails followed over the course of five weeks. Response collection closed on May 31, 2021; the surveyed period included part of the height of the Delta variant “third wave” Covid-19 pandemic (Public Health Ontario, 2023). All questions on the survey were optional, and responses were collected anonymously. To encourage fuller disclosure, except for one question that asked for the geographical type (e.g. small, medium or large population centres) in which the respondent’s ACT team was located, no information was collected that would link the respondent’s response to the name of the team, or clinical position of the respondent on the team. Only completed and submitted responses are included in this analysis. We use descriptive information and 2-sample t-tests statistical analysis for the comparisons of before- and after-Covid DACTS scores.

Results

The final data set consisted of 144 completed surveys for an estimated completion rate of 62.1%. We received 32 responses from Metro Toronto (population 5.4 million), 57 from other large centres (population > 100,000), 29 from medium (population 30,000–99,999), 20 from small (population < 30,000), 4 from rural regions, and 2 unknowns. The proportions of responses from each geographical region matched well with the actual distribution and proportion the ACT teams in those geographical centres.

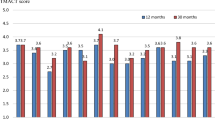

As outlined in Table 1, our study shows the overall mean DACTS score - by combing all participants’ answers across Ontario - from one-year pre-Covid (2018–2019) was 3.65 (Human resources 3.66, Organization boundary 3.89, Nature of Services 3.40). This score corresponds to a medium fidelity by DACTS standards (between 3.0 and 3.9). The item-specific fidelity scores show low fidelities in attendance in substance abuse treatment (1.39), and team’s approach in addictions (2.91). The high fidelity areas were numerous - some highlights include staff to client ratio (4.34), team approach in patient contacts (4.19), low turnover (4.24), having full nursing staff (4.41), regular new intake (4.84), full range of services (4.21), appropriate discharges (4.57), community milieu contacts (4.42), case retention (4.51) and active engagement (4.74).

When compared to the year pre-Covid – using 2-sample t-tests, the overall post-Covid DACTS scores declined by 3.84% (p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.09–0.19]) across the province. The subcategory of DACTS fidelity scores all declined during the pandemic: Human Resources (HR) dropped by 4.92% (p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.078–0.27]), Organization Boundaries (OB) by 1.03% (p < 0.013, 95%CI [0.01–0.07]), and Nature of Services (NoS) by 6.18% (p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.16–0.26]) (see Table 1 for details). The regional differences were notable: regarding HR: Small centres and Rural area combined declined (−0.31%, p < 0.97, 95%CI [−0.37–0.39]), and Metro Toronto (−3.46%, p < 0.29, 95%CI [−0.12–0.39]) had the least impact, while medium (−6.06%, p < 0.025, 95%CI [0.03–0.41]) and large centres (−6.49%, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.17–0.32]) were more affected. For OB, the impact was minimal, with all regional changes being under 2% and only metro Toronto had a significant decline (−1.20%, p < 0.017, 95%CI [0.008–0.078]). For NoS, the magnitude of change in this domain was the largest overall, with all regions experiencing significant changes between 5 and 7%, with the highest being in large centres.

More specifically, the most prominent DACTS changes were under HR, where the 3 most significant changes were (1) reduced face-to-face interactions with more than one clinician (-27.92%, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.94–1.40]), (2) more staff turnover (−2.36%, p < 0.0088, 95%CI [0.024–0.16]), and (3) less full complement of staff (−2.36%, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.063–0.21]).

For OB, there were also 3 significant changes: (1) reduced admission (−1.25%, p < 0.014, 95%CI [0.0089–0.077]), (2) reduced services (−1.19%, p < 0.019, 95%CI [0.0083–0.092]), and (3) less involvement in client hospital discharges (−2.62%, p < 0.033, 95%CI [0.0068–0.16]).

For NoS, where most of the impact occurred, there were 6 significant findings. These included (1) decreased community visits (−9.73%, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.18–0.68]), (2) less time spent in interactions (−17.50%, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.47–0.79]), (3) lowered face-to-face contacts (−17.82%, p < 0.001, 95%CI: [0.40–0.68]), (4) decreased contacts with client’s support network (−4.29%, p < 0.050, 95%CI [0.00032–0.29]), (5) less services for addictions (−1.93%, p < 0.011, 95%CI [0.013–0.10]), and (6) less attendance of addictions treatment groups (−14.39%, p < 0.0043, 95%CI [0.064–0.34])

Overall, out of the 28 DACTS items, 12 items were affected, while the remainder remained relatively unchanged and intact. Highlights of the unaffected areas (all under 3% change, and all p > 0.05) were staff to client ratio, team meetings, availability of psychiatrist, nurses, addictions specialists, vocational specialists, and full-time staff, after-hours crisis response, hospital admissions assistance, client retainment, team approach in substance misuse issues, and peer support workers providing direct services.

(Of note: Compared to the similar survey conducted in 2008 (George et al., 2010), where the overall fidelity was 4.22 (considered a high fidelity score; specifically: Human resources 4.25, Organizational boundaries 4.61, Nature of services 3.92), the current pre-Covid score of 3.65 showed an overall decrease of 13.5%.)

Discussion

Using the well-researched DACTS, the current quantitative study shows a number of significant specific changes in ACT services in Ontario, Canada during the pandemic. These involved, not surprisingly given the limited person-to-person contact by public health mandates, reduction in number of face-to-face time with clients, community visits, and psychosocial programs and support, including access to substance use groups, ACT being less involved in discharge planning, and reduction in clinician and psychiatrist staff. On the positive side, the results also show numerous higher fidelity fields pre-Covid in areas such as caseload, overall staff stability, range of services and outreach engagement, among others. However, there are notable areas of low fidelity such as a lack in addictions treatment, vocational specialists, and low after-hour care, making the overall fidelity wanting even before the pandemic, with substantial drop from a decade ago.

Regarding pandemic related changes to team quality, the most affected, as expected, were related to the Nature of Services domain, with loss of face-to-face contacts and appointments, time spent, community visits, and psychosocial and addictions support. To compensate, studies have shown that many ACT services resorted to alternative ways such as virtual care, using different (e.g. longer acting injection) medications, collaborations with allied professionals and families, etc. during the pandemic (Couser et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2021). These adaptations were not likely captured by the DACTS. However, incorporating the positive adaptations and preserving the strengths of person-to person contact should be a priority in post-pandemic recovery for ACT services. Research has consistently shown that community outreach is a key ingredient of ACT effectiveness (Bond & Drake, 2015), and most clinicians value the depth and quality of in-person care (McGrew et al., 2003). Regarding virtual care, while there are some benefits to such, its quality and desirability are still uncertain, and client access to technology is also a barrier (Tse et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020). Further research to optimize a hybrid model that includes in-person and telehealth options is warranted (Rosenheck et al., 2021; Zulfic et al., 2020).

The findings of higher staff turnover and lowered availability of workforce are of note. Whether these changes were temporary, reflecting the known disruptions from infectious illness, and staff burnout, or something longer lasting, is a potential area of concern. ACT services rely on a sub-specialized and dedicated work force to offer a full range of services. Such threat of attrition or staff shortage may differentially affect provisions such as peer support, employment, and housing services, as reported by a recent pre-pandemic survey (Spivak et al., 2019). The current study may highlight where future services planning need to monitor.

The current study also found regional differences in Ontario. Of note, the impact on rural areas and small centres were generally smaller when compared to those of the larger centres. This was possibly reflecting the pandemic’s lower impact in less densely populated areas, allowing the core of ACT services to be relatively preserved, despite their less resourced pre-existing condition that are typical of rural North American ACT teams (George et al., 2010; Meyer & Morrissey, 2007; Stefancic et al., 2013).

In terms of Organizational Boundaries, the changes were relatively minor. However, as expected, the rates of admission to ACT were affected. Responsibility for client care was also affected as the front-line, in-home services happened less frequently. Some of these impacts may have been felt by allied professionals as there are reports that suggest Emergency Room, ambulance services, or even police were more likely to be involved in servicing people with SMI during the pandemic (Laufs & Waseem, 2020; Tuczyńska et al., 2021). Being less involved for clients’ hospital discharge was also a significant finding. While this may be related to pandemic hospital protocol changes, close monitoring of this key ACT service and function should be done to ensure high quality, seamless services at a highly vulnerable time for clients (Cutcliffe et al., 2012; Goldacre et al., 1993).

Overall, despite a very disruptive crisis at a global level, the magnitude of changes to the ACT services as monitored by DACTS was relatively modest – mostly under 3%, with pandemic related exceptions. These are modest changes when compared to those areas of medicine that have experienced more extreme disruptions, including primary care, general psychiatry, orthopedics, cardiology, neurosurgery, and others according to a recent review (Tuczyńska et al., 2021). Relatedly, the ACT model may have advantages in its design and philosophical approach that emphasizes strong professional dedication, quick decision-making capacity, positive problem-solving attitudes, task and burden sharing, a relative horizontal organizational hierarchical structure, and mutual support (Bond et al., 2001). These attributes may ultimately support resilience and adaptability in the service model at a time of a major disruption (Bommersbach et al., 2021; Dixon, 2000). In other words, ACT is set up and trained to manage crises, including the likes of a global pandemic. The relative modest change may also be related to the fact that ACT is created with a robust range of resources and scope of services, allowing it to be flexible and adaptable (Bond & Salyers, 2004; Schöttle et al., 2014). The key ingredients are also wide ranging, with multiple, likely additive and interactive ways to address the complex needs of people with SMI (Bond & Drake, 2015).

Last but not least, a surprising and important finding was that at a larger picture level, our study shows the overall one-year pre-Covid (2018–2019) fidelity of ACT teams in Ontario were on average of medium fidelity (3.0-3.9). Compared to the previous similar survey in 2007–2008 (George et al., 2010), which found Ontario ACT with an overall fidelity score of 4.22 (high fidelity), the current results show a substantial decline in the last decade, by about 13.5%, a drop much higher than that related to the pandemic. Some changes in fidelity scores over 13 years are expected, but given that the two surveys used the same DACTS instrument and very similar survey methods, the consistent downward trend and large differences are worth pondering. The areas that showed the lower fidelity were in addition services, vocational support, and after-hours care, among others – all related to some of the areas that ACT needed to do to increase high quality wrap-around care. Reasons for such an insidious drop may be complex, likely related to a relative global funding decline in the community psychiatry sector in Ontario, and or a lack of commensurate increase in resources as client populations and demand for services increased (Bartram, 2017). This disquiet about a lack of resources is not unique, as it echoes concerns in other North American jurisdictions (Moser et al., 2004; Spivak et al., 2019). The differences between the current study and the 2007–2008 one could also be due to slight differences in methodologies - the earlier survey was recorded in real time, and the current study relied on recall about a period 2 years ago, the overall magnitude of deterioration was large and unmistakable, and attention must be paid to address this downward drift in quality of ACT teams in Ontario. This is particularly salient as the pandemic related negative changes are more easily ameliorated, as in-person contacts and time spent with patients are rebounding when the pandemic recedes. The historical changes in the last 13 years in terms of loss of addictions and vocational support would require a closer examination and may require system level intervention.

While having in-house capacity to address addictions and vocational challenge are likely part of the key ingredients of ACT’s success (McGrew & Bond, 1995), one possible explanations of the current study findings of their loss from ACT teams could be that these services have been “out-sourced” to other community providers. From a front-line community service providers’ perspective, we have witnessed development of more addictions services such as detoxification beds, assessments and counselling resources, and opioid replacement therapy, etc., in some regions of the province. How well these are integrated into the community mental health system, and how much of these services are accessed by ACT clients are not well known, and deserve additional research. What research does show is a large up-tick of addictions problems, particularly those related to opioid and stimulant use in the province at large, overwhelming existing services (Gomes et al., 2023; Kourgiantakis et al., 2023). Other challenges include a shortage of residential treatment, gaps in program types, barriers to access, and regional imbalance in services (Government of Canada, 2018; Mandal & Burella, 2021; Rush et al., 2021). Reliance on Emergency Room for addictions treatment is common (Matsumoto et al., 2017). These system and social level realities make the lack of addictions services on ACT more troubling overall. The picture on vocational support is likely worse, as little to no employment support programs for people with mental disabilities have been developed in the province at large (Rebeiro Gruhl, 2012; Latimer et al., 2020; Menear et al., 2011). In summary, the decline in both addictions and vocational support on ACT teams likely have direct negative impact on the quality of ACT services.

Lastly, little research is available to inform the field how some of the pandemic related adaptations (e.g. Guan et al., 2021; Couser et al., 2021; Law et al., 2021) have impacted on the quality of ACT services. There are some preliminary reports that highlight a mixture of negative clinical impacts, increased addictions issues, emergency service involvement, and positive adaptations and resilience in ACT settings in Ontario and elsewhere (Kassam et al., 2023a, b; Motamedi et al., 2022). Based on the current DACTS survey, the magnitude of negative DACTS changes over the pandemic seem limited. In addition, there may be aspects of positive changes that were not captured by the DACTS instrument. Case in point, researchers have found that the pandemic has had relatively minor impact on the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) programs - another fidelity based service - in New York state and elsewhere as they shifted to virtual or remote form of services (Margolies et al., 2022; Wittlund et al., 2023). Moreover, when researchers adapted the fidelity instrument to accommodate pandemic adaptations such as remote services, the pandemic related changes were minimal (Margolies et al., 2022). In the current study, despite the inclusion of virtual care, DACTS scores still registered a decrease in quality, suggesting the pandemic has had more substantial impact on the out-reach oriented and more complex ACT services.

Limitations of the current study include the use of self-reported DACTS, which may not be as reliable as on-site evaluation by trained assessors (e.g. Lee & Cameron, 2009). This less-than-ideal but real-world adaptation may be better understood through the lens of a quality improvement or monitoring – which DACTS is also known to be suitable (Bond, 2013) - during the crisis of a pandemic. The Ontario teams surveyed are experienced ACT teams that have typically been in existence for more than 20 years, so the DACTS was used less for establishing whether they qualify to be an ACT - as standard DACTS assessment are meant to be, but evaluating how well they function as a ACT team (Salyers et al., 2003). Another limitation is the fact that some ACT teams were over-represented in the current survey that used the average DACTS scores (144 responses for 80 teams). Given the nature of the anonymous survey, we did not track the exact teams from which the respondents came. This could have introduced a bias of the data in either direction. Similarly, inter-rater reliability test was not feasible. The cross-sectional survey for assessors to recall two separate time periods may also introduce recall bias and the direction of bias is unclear from the data. As research shows, a prolonged recall period likely will lead to recall biases and negatively affect data quality (Te Braak et al., 2023). Future studies should aim to reduce the recall periods, encourage the use of memory aids, use standard instruments and objective, validated, and time stamped materials to substantiate the responses, and evaluate the agreements between responses from self-reporting surveys and gold-standard evaluations to check reliability and validity (Biemer et al., 2013; Althubaiti, 2016). Noting our study’s limitation, one would have anticipated some bias in the direction of overestimating the negative impact of the pandemic based on the dread and frustration with the pandemic, and possibly rosier recall bias for the “normal” and better times in the pre-Covid period. However, contrary to these anticipated directions of biases, the study results showed consistency in the trends and a relative small difference between the pre- and-post Covid DACTS scores, making the study results quite remarkable. More interestingly, the bigger difference was the historical drop from the previous provincial study. There is also a lack of qualitative information to contextualize the quantitative findings. The Ontario based setting may limit the representativeness and generalizability of the study. While it may be counter-intuitive to measure fidelity during a time of a major –hopefully temporary - disruption, the current results do provide a quick sentinel survey of the recent past and pandemic related changes, and inform on areas to improve for the future, as well as provide some reassurance on the resilience and stability of the sector and ACT as a service model. Lessons learned from the current study could be useful to prepare for future disruptions, and to sound alarm for the current state of its overall fidelity compared historically. How these changes have already affected client stability, clinical outcome, and recovery remains to be seen.

Implications for Behavioral Health

This timely measure of the impact of the pandemic on the team quality of a major service sector that services people with severe mental illness shows specific loss of services related to public health mandates, which were predictable. There were some areas that were more insidious and would require close monitoring lest the erosion from the pandemic is more permanently set and affect the overall quality of care from this crucial sector. The overall fidelity of Ontario ACT teams were medium pre-pandemic, and showed a decline from similar survey a decade ago. This notable change suggests possible decrease in resource support and the trend is alarming and deserve strong advocacy and prioritizing for a sector that serves one of the most marginalized and vulnerable populations. The overall relatively modest change in team quality suggests ACT model resilience and design advantage in coping with large-scale disruption. Quantitative evaluations to ascertain disruptions and their historical changes and impact are well warranted,

References

Althubaiti, A. (2016). Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 211–217.

Bartram, M. (2017). Making the most of the federal investment of $5 billion for mental health. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189(44), E1360–E1363. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170738.

Biemer, P. P., Groves, R. M., Lyberg, L. E., Mathiowetz, N. A., & Sudman, S. (Eds.). (2013). Measurement errors in surveys (Vol. 548). Wiley.

Bommersbach, T., Dube, L., & Li, L. (2021). Mental health staff perceptions of improvement opportunities around COVID-19: A mixed-methods analysis. Psychiatric Quarterly, 92(3), 1079–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-021-09890-2.

Bond, G. R. (2013). Self-assessed fidelity: Proceed with caution. Psychiatric Services, 64(4), 393–394.

Bond, G. R., & Drake, R. E. (2015). The critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 240–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20234.

Bond, G. R., & Salyers, M. P. (2004). Prediction of outcome from the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Fidelity Scale. CNS Spectrums, 9(12), 937–942. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900009792.

Bond, G. R., Drake, R. E., Mueser, K. T., & Latimer, E. (2001). Assertive Community Treatment for people with severe mental illness. Disease Management and Health Outcomes, 9(3), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200109030-00003.

Couser, G. P., Taylor-Desir, M., Lewis, S., & Griesbach, T. J. (2021). Further adaptations and reflections by an Assertive Community Treatment Team to serve clients with severe mental illness during COVID-19. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(7), 1217–1226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00860-3.

Covell, N. H., Foster, F., McGovern, M., Lopez, L. O., Shaw, R., & Dixon, L. B. (2021). Intermediary organizations can support integration of fidelity self-assessment and quality improvement. Global Implementation Research and Applications, 1, 30–37.

Cutcliffe, J. R., Links, P. S., Harder, H. G., Balderson, K., Bergmans, Y., Eynan, R., Ambreen, M., & Nisenbaum, R. (2012). Understanding the risks of recent discharge. Crisis, 33(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000096.

Dixon, L. (2000). Assertive Community Treatment: Twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services, 51(6), 759–765. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.51.6.759.

Druss, B. G. (2020). Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in populations with serious mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(9), 891. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0894.

George, L., Durbin, J., & Koegl, C. J. (2009). System-wide implementation of ACT in Ontario: An ongoing improvement effort. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 36(3), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-008-9131-5.

George, L., Kidd, S., Wong, M., Harvey, R., & Browne, G. (2010). ACT fidelity in Ontario: Measuring adherence to the model. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 29(S5), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2010-0036.

Goldacre, M., Seagroatt, V., & Hawton, K. (1993). Suicide after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care. The Lancet, 342(8866), 283–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(93)91822-4.

Gomes, T., Leece, P., Iacono, A., Yang, J., Kolla, G., Cheng, C., et al. (2023). Characteristics of substance-related toxicity deaths in Ontario: Stimulant, opioid, benzodiazepine, and alcohol-related deaths. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network.

Government of Canada. Background document: public consultation on strengthening Canada’s approach to substance use issues. Published (September 2018). Accessed Jan 18, 2024.https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/substance-use/canadian-drugs-substances-strategy/strengthening-canada-approach-substance-use-issue/strengthening-canada-approach-substance-use-issue.pdf.

Guan, I., Kirwan, N., Beder, M., Levy, M., & Law, S. (2021). Adaptations and innovations to minimize service disruption for patients with severe mental illness during COVID-19: Perspectives and reflections from an Assertive Community Psychiatry program. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00710-8.

Kassam, A., Beder, M., Maher, J., Sediqzadah, S., Kirwan, N., Ritts, M., & Law, S. (2023a). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on Assertive Community Treatment Team Functions, Clinical services, and observable Outcomes—A Provincial Survey in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 42(2), 53–65.

Kassam, A., Beder, M., Sediqzadah, S., Levy, M., Ritts, M., Maher, J., & Law, S. (2023b). Impact of COVID-19 on the lives of people with severe mental illness—front-line community psychiatry workers observation from a provincial survey of assertive community treatment teams in Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 17(1), 1–11.

Kourgiantakis, T., Markoualkis, R., Lee, E., Hussain, A., Lau, C., Ashcroft, R. (2023). Access to mental health and addiction services for youth and their families in Ontario: Perspectives of parents, youth, and service providers. Int J Ment Heal Syst. ;17(4).

Kozloff, N., Mulsant, B. H., Stergiopoulos, V., & Voineskos, A. N. (2020). The COVID-19 global pandemic: Implications for people with schizophrenia and related disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(4), 752–757. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa051.

Latimer, E., Bordeleau, F., Méthot, C., Barrie, T., Ferkranus, A., Lurie, S., & Whitley, R. (2020). Implementation of supported employment in the context of a national Canadian program: Facilitators, barriers and strategies. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 43(1), 2.

Laufs, J., & Waseem, Z. (2020). Policing in pandemics: A systematic review and best practices for police response to COVID-19. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101812.

Law, S., Guan, I., Beder, M., Ritts, M., Sediqzadah, S., Levy, M., & Kirwan, N. (2021). Further adaptations and reflections by an assertive community treatment team to serve clients with severe mental illness during COVID-19. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(7), 1227–1229.

Lee, N., & Cameron, J. (2009). Differences in self and independent ratings on an organisational dual diagnosis capacity measure. Drug and Alcohol Review, 28(6), 682–684.

Mandal, A., & Burella, M. (2021). Inadequate mental health supports in rural and northern Ontario communities. Ontario Medical Students Association.

Margolies, P. J., Humensky, J. L., Chiang, I. C., Covell, N. H., Jewell, T. C., Broadway-Wilson, K., & Dixon, L. B. (2018). Relationship between self-assessed fidelity and self-reported employment in the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Services, 69(5), 609–612.

Margolies, P. J., Chiang, I., Jewell, T. C., Broadway-Wilson, K., Gregory, R., Scannevin, G., & Dixon, L. B. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a statewide Individual Placement and Support employment initiative. Psychiatric Services, 73, 705–708. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100120.

Matsumoto, C. L., O’Driscoll, T., Lawrance, J., Jakubow, A., Madden, S., & Kelly, L. (2017). A 5-year retrospective study of emergency department use in Northwest Ontario: A measure of mental health and addictions needs. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 19(5), 381–385.

McGrew, J. H., & Bond, G. R. (1995). Critical ingredients of assertive community treatment: Judgments of the experts. The Journal of Mental Health Administration, 22, 113–125.

McGrew, J. H., Pescosolido, B., & Wright, E. (2003). Case managers’ perspectives on critical ingredients of Assertive Community Treatment and on its implementation. Psychiatric Services, 54(3), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.370.

McGrew, J. H., White, L. M., Stull, L. G., & Wright-Berryman, J. (2013). A comparison of self-reported and phone-administered methods of ACT fidelity assessment: A pilot study in Indiana. Psychiatric Services, 64(3), 272–276.

Menear, M., Reinharz, D., Corbière, M., Houle, N., Lanctôt, N., Goering, P., & Lecomte, T. (2011). Organizational analysis of Canadian supported employment programs for people with psychiatric disabilities. Social Science & Medicine, 72(7), 1028–1035.

Meyer, P. S., & Morrissey, J. P. (2007). A comparison of Assertive Community Treatment and Intensive Case Management for patients in rural areas. Psychiatric Services, 58(1), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.121.

Moore, K., Lipsitch, M., Barry, J., & Osterholm, M. (2020). The future of the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from pandemic influenza. COVID-19: the CIDRAP viewpoint (Vol. 1).

Moser, L. L., DeLuca, N. L., Bond, G. R., & Rollins, A. L. (2004). Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: Lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectrums, 9(12), 926–936942. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900009780.

Motamedi, N., Gunturu, S., & Tabor, E. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) from March 2020 to February 2021 in Bronx, NY. Arch Community Med, 4(1), 40–44.

Neda, M., Sasidhar, G., Ellen, T., Louisa, C., & Alexis, A. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) from March 2020 to February 2021 in Bronx, NY. Archives of Community Medicine, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.36959/547/650.

OAAF. (2022). Directory. OntarioACTassociation.com.

Public Health Ontario (2023). -. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/infectious-disease/covid-19-data-surveillance/covid-19-data-tool?tab=summary.

Rebeiro Gruhl, K. (2012). Transitions to work for persons with serious mental illness in northeastern Ontario, Canada: Examining barriers to employment. Work (Reading, Mass.), 41(4), 379–389.

Rosenheck, R., Johnson, B., Deegan, D., & Stefanovics, E. (2021). Impact of COVID-19–related social distancing on delivery of intensive case management. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 209(8), 543–546. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001358.

Rush, B., Talbot, A., Ali, F., Giang, V., Imtiaz, S., Elton-Marshall, T. (2021). Environmental scan of withdrawal management practices and Services in Canada: response to opioid use disorder. Toronto, Ontario: Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse; June 4; 2021.

Salyers, M. P., Bond, G. R., Teague, G. B., Cox, J. F., Smith, M. E., Hicks, M. L., & Koop, J. I. (2003). Is it ACT yet? Real-world examples of evaluating the degree of implementation for assertive community treatment. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 30, 304–320.

Schöttle, D., Schimmelmann, B. G., Karow, A., Ruppelt, F., Sauerbier, A. L., Bussopulos, A., Frieling, M., Golks, D., Kerstan, A., Nika, E., Schödlbauer, M., Daubmann, A., Wegscheider, K., Lange, M., Ohm, G., Lange, B., Meigel-Schleiff, C., Naber, D., Wiedemann, K., & Lambert, M. (2014). Effectiveness of integrated care including therapeutic Assertive Community Treatment in severe schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar I disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(12), 1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08817.

Spivak, S., Mojtabai, R., Green, C., Firth, T., Sater, H., & Cullen, B. A. (2019). Distribution and correlates of Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) and ACT-like programs: Results from the 2015 N-MHSS. Psychiatric Services, 70(4), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700561.

Stefancic, A., Henwood, B. F., Melton, H., Shin, S. M., Lawrence-Gomez, R., & Tsemberis, S. (2013). Implementing Housing First in rural areas: Pathways Vermont. American Journal of Public Health, 103(S2), S206–S209. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301606.

Stein, L. I., & Test, M. A. (1980). Alternative to mental hospital treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37(4), 392. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003.

Te Braak, P., van Tienoven, T. P., Minnen, J., & Glorieux, I. (2023). Data quality and recall bias in time-diary research: The effects of prolonged recall periods in self-administered online time-use surveys. Sociological Methodology, 53(1), 115–138.

Teague, G. B., Bond, G. R., & Drake, R. E. (1998). Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: Development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(2), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080331.

Tse, J., LaStella, D., Chow, E., Kingman, E., Pearlman, S., Valeri, L., Wang, H., & Dixon, L. B. (2021). Telehealth acceptability and feasibility among people served in a community behavioral health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatric Services, 72(6), 654–660. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000623.

Tuczyńska, M., Matthews-Kozanecka, M., & Baum, E. (2021). Accessibility to non-COVID health services in the world during the COVID-19 pandemic: Review. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.760795.

Wittlund, S., Butenko, D., Brandseth, O. L., Brinchmann, B., Killackey, E., McDaid, D., Rinaldi, M., & Mykletun, A. (2023). Impact of Covid-19 restrictions on Individual Placement and support service delivery in northern Norway. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 10, 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-022-00304-5.

Zhou, X., Snoswell, C. L., Harding, L. E., Bambling, M., Edirippulige, S., Bai, X., & Smith, A. C. (2020). The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemedicine and E-Health, 26(4), 377–379. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0068.

Zulfic, Z., Liu, D., Lloyd, C., Rowan, J., & Schubert, K. O. (2020). Is telepsychiatry care a realistic option for community mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 54(12), 1228–1228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420937788.

Acknowledgements

The research team wishes to thank Ontario ACT and FACT Association members for supporting the survey. the research was supported by Alternative Funding Plan (AFP) COVID research grant from St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health, Toronto, Ontario, and Academic Scholar Award, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto.

Funding

The study was approved by the St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Research and Ethics Board. The study was supported by the Ontario Academic Health Science Centre Alternative Funding Plan Innovations Funds; and in part by an Academic Scholars Award from the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, design and writing of this study. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Aly Kassam and Samuel Law. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Samuel Law and Aly Kassam, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest was involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Law, S., Kassam, A., Beder, M. et al. Impact of the Pandemic was Minor Compared to Systemic Decrease in Fidelity of Assertive Community Treatment Services- A Provincial Study in Ontario, Canada. Adm Policy Ment Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-024-01375-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-024-01375-1