Abstract

Standardized assessment measures are important for accurate diagnosis of mental health problems and for treatment planning and evaluation. However, little is known about youth mental health providers’ typical use of standardized measures across disciplines and outside the context of evidence-based practice initiatives. A multidisciplinary national survey examined the frequency with which 674 youth mental health providers administer standardized and unstandardized measures, and the extent to which organizational (i.e., implementation climate, rigid hierarchical organizational structure) and provider (i.e., attitudes toward standardized assessment measures, highest degree, practice setting) characteristics are associated with standardized measure use. Providers used unstandardized measures far more frequently than standardized measures. Providers’ perceptions (a) that standardized measures are practical or feasible, (b) that their organization supports and values evidence-based practices, and (c) that their organization has a rigid hierarchical structure predicted greater use of standardized measures. Working in schools predicted less frequent SMU, while working in higher education and other professional settings predicted more frequent SMU. Standardized measures were not routinely used in this community-based sample. A rigid hierarchical organizational structure may be conducive to more frequent administration of standardized measures, but it is unclear whether such providers actually utilize these measures for clinical decision-making. Alternative strategies to promote standardized measure use may include promoting organizational cultures that value empirical data and encouraging use of standardized measures and training providers to use pragmatic standardized measures for clinical decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Accurate assessment and identification of presenting concerns is the cornerstone of effective intervention; it is how we identify those in need of services, how we match them to treatments with demonstrated efficacy for their presenting concerns, and how we monitor the impact of treatment and make clinical decisions about ongoing care (Hunsley & Mash, 2007; Jensen-Doss & Hawley, 2010). Data obtained from standardized measures, with demonstrated reliability and validity for specific populations or settings, help supplement informal client report and provide an objective check on clinician judgment. Indeed, use of standardized assessments is critical to evidence-based assessment, the process by which providers use research to guide measure selection (i.e., for screening, diagnosis, ongoing monitoring), interpretation of results, and use of these results to guide clinical decision-making (Hunsley & Mash, 2007).

Standardized measures outperform unstandardized assessments on diagnostic accuracy and are less prone to the many biases of unstructured, informal approaches (e.g., Basco et al., 2000; Jenkins et al., 2011; Rettew et al., 2009). For example, compared to standardized diagnostic interviews and other standardized measures, unstandardized clinical interviews may underestimate both the number of diagnoses per child and the number of cases that do not meet criteria for any diagnosis (Jensen & Weisz, 2002). Indeed, extensive disagreement between diagnoses derived from standardized interviews and unstandardized approaches has been previously documented (e.g., Kramer et al., 2003; Lewczyk et al., 2003). Misdiagnoses and missed diagnoses have critical implications for treatment. Youths with undetected mental health problems are less likely to receive appropriate treatment (Geller et al., 2004; Kramer et al., 2003). Misdiagnosed youths show poorer treatment engagement (e.g., no-show rates, premature termination) and smaller reductions in symptoms during the course of treatment (Jensen-Doss & Weisz, 2008). Over time, repeated failure to accurately identify and target youth mental health problems may contribute significantly to the already substantial cost of treatment by delaying needed services until later adolescence or adulthood when the chronicity of disorders may require more intensive treatment.

Standardized measures also play a key role in progress monitoring during treatment. Progress monitoring is associated with improved client engagement and outcomes across a wide range of settings, populations, and treatment approaches (Scott & Lewis, 2015). It has been shown to facilitate identification of treatment failure in youths (Cannon et al., 2010; Warren et al., 2010) and is also associated with faster symptom improvement (Bickman et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2010). Consequently, there is growing interest in supporting progress monitoring in routine clinical practice settings (Lui et al., 2021).

Unfortunately, use of standardized measures may not be routine in many settings where youths receive mental health care. Discipline-specific (e.g., psychology, social work, psychiatry; Cashel, 2002; Gilbody et al., 2002; Hatfield & Ogles, 2004; Ventimiglia et al., 2000) surveys suggest that providers infrequently use standardized measures, instead relying more on unstandardized, informal assessment approaches. Similarly, surveys of providers’ use of treatment progress monitoring suggest that while providers generally hold favorable views of progress monitoring, they harbor less positive attitudes toward standardized measures (Bickman et al., 2000; Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b) and do not routinely use standardized measures to monitor progress (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b). Somewhat disheartening, even within evidence-based practice (EBP) initiatives to use standardized measures, providers may rely more on other assessment methods (e.g., clinical intuition) than standardized measures, and do not consistently use the information produced by these measures to inform or guide practice (Batty et al., 2013; Garland et al., 2003; Johnston & Gowers, 2005; Lui et al., 2021).

While it is important to understand what assessment methods child providers are using and with what frequency, this information alone is insufficient to inform understanding of why, or under what conditions, providers use standardized measures, information needed to enhance assessment practices in the community. Standardized measure use is embedded within multiple contextual levels. Individual providers conduct interviews and administer measures with specific clients within a particular practice setting or organization, which are embedded within the broader mental health system (Damschroder et al., 2009). At the provider level, providers’ attitudes toward standardized measures may be an important determinant of their use of these measures. Perceived burden on providers and clients, beliefs that outcome measurement is unhelpful or irrelevant to their practice, and negative perceptions about the feasibility of standardized measures are associated with less frequent use (Garland et al., 2003; Hatfield & Ogles, 2004; Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b; Jensen-Doss & Hawley, 2010). Provider background characteristics may also contribute to standardized measure use. For example, doctoral providers from psychology and psychiatry backgrounds may use standardized measures more frequently (Cook et al., 2017) and hold more positive attitudes toward standardized measures (Jensen-Doss & Hawley, 2010), which in turn predict actual use (Jensen-Doss & Hawley, 2010; Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b).

Organizational characteristics may also impact assessment practices as organizational context socializes providers on how they should behave and what work behaviors are most valued and supported (Glisson & James, 2002). Organizational culture reflects how things are done within an organization and the organization’s behavioral expectations for providers (Glisson et al., 2008). One element of organizational culture is rigidity, the extent to which providers have flexibility in making decisions and the degree to which their behaviors are regulated by organizational policies. Glisson et al. (2008) suggested that a rigid and centralized hierarchy of authority may be important to implementation of “routinized technologies” while a more flexible hierarchy may be important to implementation of more creative, procedural work technologies. Standardized measures can be conceptualized as a type of “routinized technology” because they are administered and scored in a consistent manner. Therefore, providers working within organizational structures characterized by a rigid hierarchy of authority (i.e., providers make few decisions, orders come from supervisors) may, if directed or required by their organization, use standardized measures more frequently (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b). While a rigid culture applies to expectations of providers’ behaviors broadly, characteristics of the organization that are specific to a targeted innovation being implemented also warrant attention (Weiner et al., 2011). In particular, positive implementation climate—the extent to which an organization supports, values, and expects use of EBPs—has been positively associated with providers’ EBP use and service quality (e.g., Aarons et al., 2009; Ehrhart et al., 2014; Glisson & James, 2002; Williams et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). Given that standardized measures are integral to evidence-based assessment which is a part of evidence-based practice, an organization that promotes positive perceptions specifically about evidence-based practices (including standardized measures) and establishes norms for their routine use may promote providers’ use of standardized measures. Indeed, in a recent survey of outpatient youth mental health providers, more favorable implementation climate for EBP was predictive of more frequent measurement based care implementation using standardized measures (Williams et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). Additionally, the type of practice setting has been shown to impact standardized measure use. Prior studies show that working in private practice settings is associated with less standardized measure use, but more research is needed in other practice settings where youths and families access mental health care (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b).

In the current study, we aim to expand on previous research by moving beyond discipline-specific (i.e., psychologists) or setting-specific (i.e., providers working within EBPIs who received training in standardized measures) samples to examine assessment practices including standardized and unstandardized measure use in a multidisciplinary, national sample of youth mental health providers (counseling, marriage and family therapy, psychiatry, psychology, and social work) independent of an EBPI. We also aim to identify provider- and organization-level factors that may promote providers’ use of standardized measures in these routine care settings. We hypothesized that (1) providers use unstandardized assessments more frequently than standardized measures; and (2) provider perceptions of a positive implementation climate, rigid hierarchical organizational structure, and positive provider attitudes toward standardized measures would each predict more frequent standardized measure use.

Method

Participants

The 674 surveyed providers included psychiatrists (26.11%), social workers (25.22%), counselors (23.74%), psychologists (22.11%), and marriage and family therapists (16.02%; providers could report more than one discipline). Providers were predominantly female (61.28%); had a mean age of 50.35 (SD = 10.66); were White (87.39%), Asian or Pacific Islander (3.71%), Black or African American (3.26%), other (1.48%), multiracial (0.59%), and American Indian and Alaska Native (0.15%); 3.56% were Latinx; split between master’s (48.66%) and doctoral/medical (50.74%) degrees. Providers primarily worked in private individual or group practice (21.07%), outpatient clinic/community mental health center (37.09%), and elementary, middle, or high school (21.66%); had an average youth caseload of 60.84 (SD = 118.49, median = 20, range = 1–1000); spent 7.97% (SD = 13.84) of their work week on assessment related activities.

Procedures

Survey procedures have been previously reported in some detail (Cho et al., 2019). The survey was developed using the Tailored Design Method (Dillman, 2000) and involved using a pilot survey and focus groups to inform survey development, a $2 bill incentive, and up to five separate, personalized contacts to maximize provider response rates. From 2007 to 2008, 1000 members were randomly selected from each of the five largest youth-serving mental health professional guilds (N = 5000): the American Counseling Association, the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists, the American Psychological Association, and the National Association of Social Workers. A total of 2751 surveys were returned for an unadjusted response rate of 55.02%. The adjusted response rate was 59.12% after accounting for 347 surveys that were undeliverable. Clinicians who reported conducting assessment with youths and working in an organizational setting (i.e., not working solely in individual or group private practice) were included in analyses (N = 674). All procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The survey was adapted from previous mental health provider surveys (Kazdin et al., 1990; Tuma & Pratt, 1982). Providers reported their demographic and professional characteristics, casemix demographics, individual provider perceptions of organizational characteristics (the survey design precluded assessment of organizational characteristics at the organizational level, i.e., aggregated across multiple clinicians in the same organization), assessment practices, attitude towards assessment, and treatment practices.

Provider Background and Practice Setting Characteristics

Providers reported their highest degree (bachelors, masters, doctoral) and discipline (counseling, marriage and family therapy, psychology, psychiatry, social work; could endorse multiple disciplines). Providers also reported all the settings in which they were currently employed: elementary, middle, or high school; college, university, medical, or professional school; outpatient clinic or community mental health center; private individual or group practice; day treatment facility or partial day hospital; residential treatment facility or group home; inpatient hospital or medical clinic; and HMO, PPO, or other managed care organization.

Perceptions of Rigid Hierarchy of Authority (RHA)

We created a latent variable measuring individual providers’ perceptions of how much their agency engaged in centralized decision-making, where individual providers have limited involvement in supervisor decisions that they are expected to follow. The five items were adapted from the Children’s Services Survey (Glisson & James, 2002). Items were rated on a one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) scale, with higher scores reflecting a more rigid hierarchy. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76 in our sample.

Perceptions of Implementation Climate

We created a latent variable measuring individual providers’ perceptions of how much their agency valued and supported EBPs, including standardized measure use. The three items were generated through a review of available measures of organizational culture and climate and provider attitudes that may support implementation of evidence-based practices (e.g., Aarons, 2004; Glisson, 2002; Glisson & James, 2002). Items were rated on a one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) scale; higher scores reflected more support for use of research supported practices. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.67 in our sample.

Attitudes Toward Standardized Assessment (ASA; Jensen-Doss & Hawley, 2010)

The Attitudes toward Standardized Assessment (ASA) is a 22-item measure of providers’ attitudes about using standardized assessment measures with three subscales: the Benefit Over Clinical Judgement subscale measures providers’ perceptions that standardized measures have utility beyond clinical judgment; the Psychometric Qualities subscale measures providers’ perceptions about the validity and reliability of standardized measures and how much they value these psychometric properties; and the Practicality subscale measures providers’ perceptions about how feasible it is to administer standardized measures in their practice. Items were rated on a one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) scale; higher scores reflect more positive attitudes. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.71 to 0.74 in our sample.

Assessment Practices

We created a latent variable consisting of providers’ use of five types of standardized measures use (SMU): structured diagnostic interview, formal mental status exam, formal observational coding system, standardized symptoms or functioning checklists, and formal clinician symptoms or functioning ratings. Items were generated from a review of studies of provider attitudes toward evidence-based assessment (Garland et al., 2003; Gilbody et al., 2002) and recommended assessment approaches for youth mental health problems (Hunsley & Mash, 2007). Items were rated from one (never or almost never) to five (all or most of the time). We also assessed providers’ use of three unstandardized measures using the same rating scale: unstructured clinical or intake interview, unstructured or informal mental status exam, and informal behavioral observation of child or family functioning. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.70 in our sample.

Data Analytic Plan

We present descriptive statistics and frequencies for all standardized and unstandardized measures. Rates of missing data were less than 7% for all variables (see sample size for all variables in Table 1), and no single missing data pattern was endorsed by more than 3% of the sample. Data were assumed to be missing at random (MAR) and analyses were conducted using pairwise deletion. We conducted paired sample t-tests to compare frequency of providers’ use of unstructured clinical interviews versus structured diagnostic interviews; informal mental status exams versus formal mental status exams; and informal behavioral observations versus formal observational coding systems.

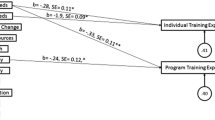

We then tested a structural equation model of the association between organizational and provider characteristics with SMU. Analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) with weighted least square parameter estimates (WLSMV) which uses a probit link function. The hypothesized model had SMU as a function of five latent variables (i.e., RHA, implementation climate, ASA Benefit Over Clinical Judgment, ASA Psychometric Qualities, ASA Practicality) and three provider background manifest variables, and estimated the correlations between all predictor variables. Due to skew in the manifest variables for all five latent variables, we transformed the manifest into categorical variables with two levels: ratings 1–3 (level 1) and ratings 4–5 (level 2). For RHA, the first level reflected a more flexible structure and the second level a rigid organizational structure. For implementation climate, the first level reflected implementation climate that placed little value on EBPs and the second level an implementation climate that placed high value on EBPs. For the ASA Benefit Over Clinical Judgment, the first level reflected perceptions that standardized measures provide little benefit beyond clinical judgment, and the second level that they offer utility beyond clinical judgment. For the ASA Psychometric Qualities, the first level reflected perceptions that standardized measures have limited psychometric support and the second level that they have psychometric support. For the ASA Practicality, the first level reflected perceptions that standardized measures are impractical and the second level that they are practical and feasible in the provider’s practice setting. For SMU, the first level reflected infrequent standardized measure use and the second level frequent use. For provider background characteristics (i.e., provider highest degree, discipline, and employment setting variables), their relationship with the SMU manifest indicators were first explored through chi square tests. The variables that were significantly associated with SMU were included in the SEM: highest degree (doctoral vs non-doctoral degree), provider background (psychology vs not psychology), provider practice setting (working in elementary, middle, or high school; working in college, university, medical, or professional school). Model fit was estimated using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). RMSEA values less than .06, and CFI and TLI values greater than .95 indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

On average, providers reported “often” to “all or most of the time” using informal behavioral observations (M = 4.54, SD = 0.76), unstructured clinical interviews (M = 4.48, SD = 0.95), and informal mental status exams (M = 4.47, SD = 0.91). Providers reported “never or almost never” to “sometimes” using standardized checklist (M = 3.33, SD = 1.40), formal clinician ratings (M = 2.55, SD = 1.52), structured diagnostic interviews (M = 2.06, SD = 1.27), formal mental status exams (M = 1.99, SD = 1.25), and formal observational coding systems (M = 1.50, SD = 0.89). Providers used unstructured clinical interviews more frequently than structured diagnostic interviews, t(628) = 35.98, p < 0.001, d = 1.71; informal mental status exams more frequently than formal mental status exams, t(657) = 41.43, p < 0.001, d = 1.53; and informal behavioral observations more frequently than formal observational coding systems, t(628) = 63.34, p < 0.001, d = 1.21.

Given the development of new measures for some of our predictors (i.e., RHA, IC), we first evaluated our measurement model. The measurement model demonstrated good fit: RMSEA = .028 (90% CI [.024, .032]), CFI = .951, TLI = .947. We then conducted the structural equation model which showed good fit: RMSEA = .030 (90% CI [.027, .033]), CFI = .935, and TLI = .927.Footnote 1 R-squared was .43. Factor loadings ranged from .53 to .95 for RHA, .69 to .88 for implementation climate, .33 to .86 for the ASA, and .40 to .86 for SMU; and all factor loadings were significant (p < .001). Rigid hierarchy (β = .26, p = .001), positive implementation climate (β = .24, p = .001), and positive attitudes on the ASA Practicality (β = .89, p < .001) increased the predicted probability of frequent SMU. Benefit Over Clinical Judgment (β = − .30, p = .251) and Psychometric Qualities (β = − .29, p = .091) subscales did not predict SMU. RHA was uncorrelated with all other latent variables. Implementation climate was positively correlated with all ASA subscales (p’s < .001). The ASA subscales were all correlated with each other (p’s < .001; see Table 2). While doctoral degree (β = − 0.03, p = .641) and psychology discipline (β = − 0.01, p = .838) did not predict SMU, they were correlated with practice setting (see all correlations in Table 2), which predicted SMU. Specifically, working in schools predicted less frequent SMU (β = − .16, p = .008) and working in universities predicted more frequent SMU (β = .13, p = .015). Interestingly, working in schools was uncorrelated with implementation climate and all the ASA subscales, while working in universities was positively associated with implementation climate and all ASA subscales, and both were negatively correlated with RHA (see all correlations in Table 2).

Discussion

Consistent with prior research on the assessment practices of youth mental health providers, we found that providers reported using unstandardized assessments often, but standardized measures rarely. Standardized checklists were the most frequently reported of the standardized measures assessed, perhaps because they are widely available in youth, parent, and teacher report versions (e.g., Beidas et al., 2015) and take a relatively short amount of time to complete and score compared to clinician administered diagnostic interviews, mental status exams, or observational coding systems. The general reliance on unstandardized assessment is disconcerting given prior research suggesting that these methods have poor agreement with standardized measures (e.g., Jensen & Weisz, 2002), and these discrepancies may have negative consequences for treatment matching and outcomes (Jensen-Doss & Weisz, 2008; Kramer et al., 2003). Fortunately, the current findings also indicate potential provider and organizational determinants that might be leveraged to enhance standardized measure use.

Addressing organizational factors that may impact standardized measure use may hold promise. Consistent with previous survey findings (e.g., Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b) and organizational theory (Glisson et al., 2008), providers who worked within organizations they characterized as having a rigid hierarchical structure reported more frequent standardized measure use. Given the nonsignificant relationship between rigid hierarchical structure and provider attitudes toward standardized assessment, it may be that structural demands to use standardized measures, irrespective of providers’ perceptions about standardized assessment, is a driving force behind standardized measure use (Garland et al., 2003; Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b; Lui et al., 2021). Should central decisions dictate standardized measure administration within an organization, special attention should be paid to how the measures are used by individual providers. When providers are required to use standardized measures by their organization, particularly if this occurs with little training or understanding of why such measures are worthwhile, they may administer these measures but not integrate the results to inform clinical decision-making (Garland et al., 2003). In other words, providers might follow the letter but not the spirit of the law, and complementary strategies to maximize the clinical impact of these standardized measures may be needed.

Fostering a positive implementation climate may be one promising avenue to support providers in following the spirit of the law. As in previous studies showing that organizational support for EBPs may be a primary facilitator of EBP adoption and implementation by frontline providers and agency leadership (Aarons & Palinkas, 2007; Aarons et al., 2009; Palinkas & Aarons, 2009), more positive implementation climate predicted more frequent standardized measure use in our sample. Targeted implementation strategies, such as organizational and leadership interventions (e.g., Aarons et al., 2015; Glisson et al., 2008; Proctor et al., 2019), to build an implementation climate conducive to standardized measure use and direct partnerships with agency leadership to garner support for standardized measure use may be helpful.

Provider attitudes toward standardized measures also deserve attention. While all ASA subscales were positively associated with each other, only perceptions about practicality predicted standardized measure use in this sample. These findings are similar to another study where attitudes about the practicality of measurement predicted progress monitoring using standardized measures over and above other attitudes including those about the general benefit of progress monitoring, their clinical benefit, and psychometric properties (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018a, 2018b). Another recent survey also found that perceptions about practicality, but not those related to clinical utility or treatment planning benefit, predicted measurement-based care use for progress monitoring, while perceptions about practicality and treatment planning benefit predicted measurement-based care use for treatment modification (Williams et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). This importance of practicality above and beyond other attitudinal factors appears to be a robust effect. If providers’ ultimate actions are largely driven by practicality and feasibility concerns, it will be critical to develop and disseminate practical (i.e., cost, time, training burden) measures that are useable in real world practice settings, and train providers to administer them and integrate them into their clinical practice (Connors et al., 2015; Whiteside et al., 2016). Consideration of the strategies providers have reported would increase their standardized measure use (e.g., automating scoring, administrative support) may also be helpful (Lui et al., 2021). One promising avenue is the dissemination and implementation of digital measurement feedback systems that allow for routine electronic collection of clients’ responses to standardized measures, automated and timely scoring of these measures, and easily interpretable presentation of outcomes to monitor progress and facilitate decision-making (Lyon & Lewis, 2016). Numerous systems have been developed (Lyon et al., 2016), and their use has been shown to improve providers’ use of standardized measures over time (Lyon et al., 2019) and to predict symptom improvement (e.g., Sale et al., 2021). Future research on how to support the successful uptake of such digital measurement feedback systems is needed for their widespread sustained use (e.g., Sichel & Connors, 2022).

The interplay between organizational factors and provider attitudes may also influence standardized measure use. Providers who perceived their organizations as valuing EBPs reported more positive attitudes toward standardized measures on all three ASA subscales, and also used standardized measures more frequently. In line with the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), it could be that an implementation climate that values EBPs may foster positive provider attitudes toward standardized measures, and these positive attitudes (regarding their feasibility, specifically) then influence providers’ intentions and actual use of standardized measures. While our cross-sectional design limits this interpretation, it is in line with that reported in longitudinal studies. Implementation climate in schools and outpatient clinics has prospectively predicted later EBP use (Williams et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c; Williams, et al., 2020). Interventions that target implementation climate show promise. For example, the ARC organizational intervention increases provider adoption and use of EBPs by first supporting the development of an organizational culture wherein providers are expected to prioritize client well-being and be competent in and knowledgeable of effective treatments; this culture in turn increases providers’ intentions to use EBPs, which leads to actual adoption and use (Williams et al., 2017). As such, further development, testing, and refinement of organizational interventions may be fruitful approaches to use of standardized measures. It may also be that organizations that value EBPs draw providers who also value research and whose training backgrounds align with those values, creating an “ideal fit” between organizations and providers who value standardized measures. However, this ideal fit may not always exist, and provider attitudes may play a greater role in their use of standardized measures in the absence of organizational support for these measures (Aarons et al., 2009). For these circumstances, the development and dissemination of practical measures may be most fruitful.

Our findings also suggest that further work is needed to better understand how different youth mental health care settings and prior training contribute to providers’ standardized measure use. The two practice settings included had different relationships with standardized measure use. Working in schools was not related to implementation climate or attitudes toward assessment and predicted less frequent standardized measure use. In contrast, working in universities, which was associated with more favorable implementation climate and attitudes, predicted greater standardized measure use. Discipline and degree were both correlated with practice setting and attitudes, but were nonsignificant predictors of SMU. It may be that prior training may contribute to post-training assessment practices by influencing providers’ attitudes and where providers ultimately practice. Future work on the barriers and facilitators of standardized measure in different types of practice settings, as well as research on how prior training may influence post-training assessment practices, are needed.

This study had several limitations. As noted previously, the survey did not assess the extent to which providers used the reported assessment practices as intended (i.e., routine integration of assessment results into clinical decision-making). Additionally, the use of idiographic assessment tools was not included. Our findings suggest that perceptions of the practicality of assessment tools impact their use, and these individualized assessment tools may provide an acceptable and practical complement to providers’ extant assessment practices and serve to inform treatment personalization (Jensen-Doss, Smith et al., 2018a, 2018b). Given the growing evidence for their psychometric properties and promise for clinical utility (e.g., Lloyd et al., 2019), future research is needed on providers’ use of idiographic assessments, their clinical utility, and barriers and facilitators to their use in community settings. Additionally, several of our measures were developed for this study at the time of survey development, though our measurement model suggested good fit. Measures of organizational characteristics including implementation climate (e.g., Implementation Climate Scale; Ehrhart et al., 2014) with strong psychometric properties are now available and should be used in future work (see also Powell et al., 2021). General limitations to survey data also include potentially unrepresentative samples, low response rates, response order effects, monomethod bias, and use of unreliable items which elicit social desirability biases (Krosnick, 1999). This study attempted to minimize some of these limitations by using a survey methodology that included pilot testing, focus groups, and multiple, personalized mailings to improve response rates (Dillman, 2000). However, clinicians in this study were selected based on their membership in a large national guild organization, and guild members may not be representative of non-guild members (e.g., guild members may have more access to resources that impact assessment practices and beliefs). Additionally, the sampling frame—a large national survey of randomly selected child-serving clinicians—required the measurement of organizational characteristics based on individual clinician perceptions. Research suggests that aggregating multiple individual clinician responses from a single organization may be important for accurately characterizing an organization’s structure and culture (Glisson, 2002). Of note, despite this limitation, our findings echo those in studies that measured these constructs at the organizational level, aggregating across multiple clinicians within an organization (Williams et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). Finally, we used a cross-sectional design, which prohibited evaluation of the process by which the provider attitude and organizational structure and culture variables interact across time.

Despite these limitations, the current study replicated previous survey findings on the frequency with which providers from the largest youth-serving mental health disciplines use unstandardized assessments and standardized measures. Additionally, to our knowledge, this is the largest survey of provider and organizational factors that influence youth providers’ use of standardized measures. To yield the most fruitful implementation strategies, further research investigating the outcomes associated with the multiple pathways through which providers may use standardized measures is needed. Comparative evaluations of different implementation strategies to improve standardized measure use may advance our understanding of which pathways and conditions are the most effective. Ultimately, these findings may inform the design of organizational and provider interventions to improve routine assessment practices.

Data Availability

Participants did not consent to the sharing of data at the time of informed consent, and thus, data are not available. Survey materials are available upon request.

Notes

Given the low factor loadings of the formal mental status exam and the formal clinician ratings, we reran the model without these two variables. Fit remained good (RMSEA = .031, CFI = .939, TLI = .931) and the pattern of results remained the same, with the exception that working in schools no longer predicted SMU.

References

Aarons, G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale. Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74.

Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., Farahnak, L. R., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2015). Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): A randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0192-y

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

Aarons, G. A., & Palinkas, L. A. (2007). Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: Service provider perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(4), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3

Aarons, G. A., Sommerfeld, D. H., & Walrath-Greene, C. M. (2009). Evidence-based practice implementation: The impact of public versus private sector organization type on organizational support, provider attitudes, and adoption of evidence-based practice. Implementation Science, 4(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-83

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Basco, M. R., Bostic, J. Q., Davies, D., Rush, A. J., Witte, B., Hendrickse, W., & Barnett, V. (2000). Methods to improve diagnostic accuracy in a community mental health setting. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(10), 1599–1605. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1599

Batty, M. J., Moldavsky, M., Foroushani, P. S., Pass, S., Marriott, M., Sayal, K., & Hollis, C. (2013). Implementing routine outcome measures in child and adolescent mental health services: From present to future practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(2), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00658.x

Beidas, R. S., Stewart, R. E., Walsh, L., Lucas, S., Downey, M. M., Jackson, K., Fernandez, T., & Mandell, D. S. (2015). Free, brief, and validated: Standardized instruments for low-resource mental health settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.02.002

Bickman, L., Kelley, S. D., Breda, C., de Andrade, A. R., & Riemer, M. (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1037/e530282011-001

Bickman, L., Rosof-Williams, J., Salzer, M. S., Summerfelt, W. T., Noser, K., Wilson, S. J., & Karver, M. S. (2000). What information do clinicians value for monitoring adolescent client progress and outcomes? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31, 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.31.1.70

Cannon, J. A., Warren, J. S., Nelson, P. L., & Burlingame, G. M. (2010). Change trajectories for the Youth Outcome Questionnaire Self-Report: Identifying youth at risk for treatment failure. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(3), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374411003691727

Cashel, M. L. (2002). Child and adolescent psychological assessment: Current clinical practices and the impact of managed care. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33, 446–453. https://doi.org/10.1037//0735-7028.33.5.446

Cho, E., Wood, P. K., Taylor, E. K., Hausman, E. M., Andrews, J. H., & Hawley, K. M. (2019). Evidence-based treatment strategies in youth mental health services: Results from a national survey of providers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0896-4

Connors, E. H., Arora, P., Curtis, L., & Stephan, S. H. (2015). Evidence-based assessment in school mental health. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.03.008

Cook, J. R., Hausman, E. M., Jensen-Doss, A., & Hawley, K. M. (2017). Assessment practices of child clinicians: Results from a national survey. Assessment, 24 (2), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115604353

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Ehrhart, M. G., Aarons, G. A., & Farahnak, L. R. (2014). Assessing the organizational context for EBP implementation: The development and validity testing of the Implementation Climate Scale (ICS). Implementation Science, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0157-1

Garland, A. F., Kruse, M., & Aarons, G. A. (2003). Clinicians and outcome measurements: What’s the use? Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 30, 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02287427

Geller, B., Tillman, R., Craney, J. L., & Bolhofner, K. (2004). Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in childrenwith a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(5), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.459

Gilbody, S. M., House, A. O., & Sheldon, T. A. (2002). Psychiatrists in the UK do not use outcomes measures: National survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(2), 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.2.101

Glisson, C., & James, L. R. (2002). The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 767–794. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.162

Glisson, C., & Schoenwald, S. K. (2005). The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research, 7(4), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1

Glisson, C., Schoenwald, S. K., Kelleher, K., Landsverk, J., Hoagwood, K. E., Mayberg, S., & Green, P. (2008). Therapist turnover and new program sustainability in mental health clinics as a function of organizational culture, climate, and service structure. Administrative Policy and Mental Health, 35, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0152-9

Hatfield, D. R., & Ogles, B. M. (2004). The use of outcome measures by psychologists in clinical practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35, 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.35.5.485

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hunsley, J., & Mash, E. J. (2007). Evidence-based assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091419

Jenkins, M. M., Youngstrom, E. A., Washburn, J. J., & Youngstrom, J. K. (2011). Evidence-based strategies improve assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder by community practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(2), 121. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022506

Jensen, A. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2002). Assessing match and mismatch between practitioner-generated and standardized interview-generated diagnoses for clinic-referred children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.70.1.158

Jensen-Doss, A., Haimes, E. M. B., Smith, A. M., Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C. F., & Hawley, K. M. (2018a). Monitoring treatment progress and providing feedback is viewed favorably but rarely used in practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0763-0

Jensen-Doss, A., & Hawley, K. M. (2010). Understanding barriers to evidence-based assessment: Clinician attitudes toward standardized assessment tools. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(6), 885–896. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2010.517169

Jensen-Doss, A., Smith, A. M., Becker-Haimes, E. M., Mora Ringle, V., Walsh, L. M., Nanda, M., Walsh, S. L., Maxwell, C. A., & Lyon, A. R. (2018). Individualized progress measures are more acceptable to clinicians than standardized measures: Results of a national survey. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(3), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-017-0833-y

Jensen-Doss, A., & Weisz, J. R. (2008). Diagnostic agreement predicts treatment process and outcomes in youth mental health clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.76.5.711

Johnston, C., & Gowers, S. (2005). Routine outcome measurement: A survey of UK child and adolescent mental health services. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 10(3), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00357.x

Kazdin, A. E., Siegal, T. C., & Bass, D. (1990). Drawing on clinical practice to inform research on child and adolescent psychotherapy: Survey of practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 21, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1037//0735-7028.21.3.189

Kramer, T. L., Robbins, J. M., Phillips, S. D., Miller, T. L., & Burns, B. J. (2003). Detection and outcomes of substance use disorders in adolescents seeking mental health treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 1318–1326. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000084833.67701.44

Krosnick, J. A. (1999). Survey research. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 537–567. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.537

Lewczyk, C. M., Garland, A. F., Hurlburt, M. S., Gearity, J., & Hough, R. L. (2003). Comparing DISC-IV and clinician diagnoses among youths receiving public mental health services. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200303000-00016

Lloyd, C. E., Duncan, C., & Cooper, M. (2019). Goal measures for psychotherapy: A systematic review of self-report, idiographic instruments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12281

Lui, J. H., Brookman-Frazee, L., Smith, A., Lind, T., Terrones, L., Rodriguez, A., Motamedi, M., Villodas, M., & Lau, A. S. (2021). Implementation facilitation strategies to promote routine progress monitoring among community therapists. Psychological Services, 19(2), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000456

Lyon, A. R., & Lewis, C. C. (2016). Designing health information technologies for uptake: Development and implementation of measurement feedback systems in mental health service delivery: Introduction to the special section. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0704-3

Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M. R., Hendrix, E., & Liu, F. (2016). Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: Results from a comprehensive review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 441–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

Lyon, A. R., Pullmann, M. D., Whitaker, K., Ludwig, K., Wasse, J. K., & McCauley, E. (2019). A digital feedback system to support implementation of measurement-based care by school-based mental health clinicians. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(sup1), S168–S179. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1280808

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide. Seventh edition. Muthén & Muthén.

Palinkas, L. A., & Aarons, G. A. (2009). A view from the top: Executive and management challenges in a statewide implementation of an evidence based practice to reduce child neglect. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development, 2(1), 47–55.

Powell, B. J., Mettert, K. D., Dorsey, C. N., Weiner, B. J., Stanick, C. F., Lengnick-Hall, R., & Lewis, C. C. (2021). Measures of organizational culture, organizational climate, and implementation climate in behavioral health: A systematic review. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895211018862

Proctor, E., Ramsey, A. T., Malone, M. T. S., Hooley, C., & McKay, V. (2019). Training in Implementation Practice Leadership (TRIPLE): Evaluation of a novel practice change strategy in behavioral health organizations. Implementation Science, 14, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0906-2

Rettew, D. C., Lynch, A. D., Achenbach, T. M., Dumenci, L., & Ivanova, M. Y. (2009). Meta-analyses of agreement between diagnoses made from clinical evaluations and standardized diagnostic interviews. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 18(3), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.289

Sale, R., Bearman, S. K., Woo, R., & Baker, N. (2021). Introducing a measurement feedback system for youth mental health: Predictors and impact of implementation in a community agency. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 48, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01076-5

Scott, K., & Lewis, C. C. (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010

Sichel, C. E., & Connors, E. H. (2022). Measurement feedback system implementation in public youth mental health treatment services: A mixed methods analysis. Implementation Science Communications, 3(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00356-5

Stein, B. D., Kogan, J. N., Hutchison, S. L., Magee, E. A., & Sorbero, M. J. (2010). Use of outcomes information in child mental health treatment: Results from a pilot study. Psychiatric Services, 61(12), 1211–1216. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.61.12.1211

Tuma, J. M., & Pratt, J. M. (1982). Clinical child psychology practice and training: A survey. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 11, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374418209533058

Ventimiglia, J. A., Marschke, J., Carmichael, P., & Loew, R. (2000). How do clinicians evaluate their practice effectiveness? A survey of clinical social workers. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 70(2), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377310009517593

Warren, J. S., Nelson, P. L., Mondragon, S. A., Baldwin, S. A., & Burlingame, G. M. (2010). Youth psychotherapy change trajectories and outcomes in usual care: Community mental health versus managed care settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018544

Weiner, B. J., Belden, C. M., Bergmire, D. M., & Johnston, M. (2011). The meaning and measurement of implementation climate. Implementation Science, 6, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-78

Whiteside, S. P., Sattler, A. F., Hathaway, J., & Douglas, K. V. (2016). Use of evidence-based assessment for childhood anxiety disorders in community practice. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.008

Williams, N. J., Becker-Haimes, E. M., Schriger, S., & Beidas, R. S. (2022a). Linking organizational climate for evidence-based practice implementation to observed clinician behavior in patient encounters: A lagged analysis. Implementation Science Communications, 3(64), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00309-y

Williams, N. J., Glisson, C., Hemmelgarn, A., & Green, P. (2017). Mechanisms of change in the ARC organizational strategy: Increasing mental health clinicians’ EBP adoption through improved organizational culture and capacity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0742-5

Williams, N. J., Hugh, M. L., Cooney, D. J., Worley, J., & Locke, J. (2022b). Testing a theory of implementation leadership and climate across autism evidence-based interventions of varying complexity. Behavior Therapy, 53(5), 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2022.03.001

Williams, N. J., Ramirez, N. V., Esp, S., Watts, A., & Marcus, S. C. (2022c). Organization-level variation in therapists’ attitudes toward and use of measurement-based care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 49(6), 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01206-1

Williams, N. J., Wolk, C. B., Becker-Haimes, E. M., & Beidas, R. S. (2020). Testing a theory of strategic implementation leadership, implementation climate, and clinicians’ use of evidence-based practice: a 5-year panel analysis. Implementation Science. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-0970-7

Funding

This research was supported in part by R03 MH077752 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Kristin M. Hawley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design, material preparation, and data collection were performed by JRC and KMH. Data analyses were performed by JRC and EC. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

This study was approved for a waiver of signed consent. All participants were provided with a consent statement.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, E., Cook, J.R. & Hawley, K.M. A Structural Model of Organization and Clinician Factors Associated with Standardized Measure Use in a National Survey of Youth Mental Health Providers. Adm Policy Ment Health 50, 876–887 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-023-01286-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-023-01286-7