Abstract

Although advances have been made in facilitating the implementation of evidence-based treatments, little is known about the most effective way to sustain their use over time. The current study examined the sustainability of one evidence-based treatment, Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), following a statewide implementation trial testing three training methods: Cascading Model, Learning Collaborative, and Distance Education. Participants included 100 clinicians and 50 administrators from 50 organizations across Pennsylvania. Clinicians and administrators reported on sustainability at 24-months, as measured by the number of clients receiving PCIT and the continued use of the PCIT protocol. Multi-level path analysis was utilized to examine the role of training on sustainability. Clinicians and administrators reported high levels of sustainability at 24-months. Clinicians in the Cascading Model reported greater average PCIT caseloads at 24-months, whereas clinicians in the Learning Collaborative reported greater full use of the PCIT protocol at 24-months. Attending consultation calls was associated with delivering PCIT to fewer families. Implications for the sustainable delivery of PCIT beyond the training year as well as for the broader field of implementation science are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Within the field of implementation science, there has been an increased understanding of factors that contribute to the initial implementation of evidence-based treatments (EBTs), but less is known about strategies that increase the sustainability of EBTs (Shelton et al., 2018). Sustainability has been defined as the “extent to which a newly implemented treatment is maintained or institutionalized within a service setting’s ongoing, stable operations” (Proctor et al., 2011, p. 70). It has been conceptualized as a multi-faceted concept, measured by whether an organization continues to provide a treatment, as well as the number of clients receiving a treatment; however, there is considerable variability in definitions of sustainability (Stirman et al., 2012). Sustainability is essential to optimize public health goals, as it is important for a treatment to be in place for an extended amount of time to reach a broad population (Schell et al., 2013; Stirman et al., 2012). Despite the importance of sustainability, a review of sustainability studies found that only five of twenty programs (25%) achieved full sustainability in which clinicians continued to utilize all initially implemented program or intervention components (Stirman et al., 2012).

There have been several studies which examine the impact of implementation strategies on sustainability. For example, Glisson et al. (2008) found that organizations with more positive organizational climates sustained programs for twice as long, suggesting the importance of identifying organizational barriers to sustainability. Developing implementation teams has also been suggested as a strategy to increase the sustainability of screening for trauma symptoms in child welfare systems (Lang et al., 2017). While these studies focused on organizational factors, additional research has examined other implementation strategies.

Conducting ongoing training has been suggested as an implementation strategy to improve initial implementation and sustainability (Powell, Mcmillen, et al., 2013; Powell, McMillen, et al., 2013). Similarly, a lack of training has been identified as a barrier to sustainability (Loman et al., 2010). Despite the knowledge that training may impact sustainability, little is known about the types of training that lead to higher levels of sustainability. Within the field of behavioral health, brief workshops and reading treatment manuals are commonly utilized methods; however, they have been shown to be largely ineffective at improving clinician knowledge and skill (Bearman et al., 2017; Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Beidas et al., 2012; Herschell et al., 2010). Several other training models are commonly used to train clinicians, with the Cascading Model (CM), Learning Collaborative (LC), and Distance Education (DE) being the most frequently used methods according to one systematic review (Herschell et al., 2010).

The CM is a hierarchical training method where one clinician is initially trained, and is subsequently able to train other clinicians within their organization (Herschell et al., 2015). This approach may be appealing to clinicians who can be trained within their organization and reduce some of the costs incurred by trainings delivered by expert trainers (Zandberg & Wilson, 2013). The CM strongly focuses training on two clinicians within an organization, and utilizes extensive in vivo modeling, skill observation, and feedback within the organization (Herschell et al., 2015). Few empirical studies have examined the efficacy of the CM, and the results have led to variable conclusions (Herschell et al., 2010; Martino et al., 2010). Several studies have found that the CM model is related to initial improvements in clinician skill and fidelity (Martino et al., 2010, 2011; Shore et al., 1995). In contrast, one of these studies also found that despite initial gains, improvements in clinician skill were not maintained at 12-week follow-up (Martino et al., 2010). While the CM has the advantage of being able to increase the number of clinicians trained in an EBT in a setting without the cost of expert trainers, there has been limited empirical evidence to support its use.

The LC was developed after the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Breakthrough Series Collaborative Model and focuses on training multiple levels within an organization, including clinicians, supervisors, and administrators (i.e., senior leaders; American Diabetes Association, 2004; Markiewicz et al., 2006). The LC is unique in that it focuses on creating a learning organization, emphasizes cross-site sharing among teams, and organizes workgroups within each organization (Herschell et al., 2015). LC models have been found to be effective in improving clinicians’ networks of advice and serving as a means of informal support throughout implementation (Bunger et al., 2016), improving clinician adherence (Dopp et al., 2017; Hanson et al., 2019), and increasing clinician fidelity (Deblinger et al., 2020). With regards to sustainability, another study found that an LC model did not result in higher rates of initial implementation or sustainability at 1- to 6-years for Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (Brown et al., 2014); however, one study found that clinicians reported greater use and perceived organizational support for TF-CBT at 2- 4-years (Helseth et al., 2020).

DE training models involve clinicians independently studying training materials, often through an online platform or reviewing training videos. Similar to CM, DE methods have the potential to be cost-effective and reach a large number of clinicians (McMillen et al., 2016). DE models can be self-paced and easily accessible to users (Herschell et al., 2015). Clinicians have also expressed satisfaction with DE methods, as they can be completed at the clinician’s pace and are an alternative to more expensive training options (Powell, Mcmillen, et al., 2013; Powell, McMillen, et al., 2013). Several systematic reviews have been conducted on the effectiveness of DE methods for behavioral health clinicians (Calder et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2018). Together, these reviews concluded that DE methods may be effective in facilitating clinician knowledge and skill, with ranges of small to large effect sizes, dependent on the type of DE method utilized. Serial instruction methods, like the one included in this study, were found to have moderate to large effect sizes for knowledge and skill (Calder et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2018). However, the included studies were limited by numerous methodological concerns making it difficult to draw broad conclusions (Calder et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2018). While there has been increased interest in the use of DE methods, additional research is needed to understand their effectiveness, particularly for long-term sustainment.

Providing ongoing consultation is commonly utilized in addition to training (Edmunds et al., 2013; Nadeem et al., 2013). Ongoing consultation provides extended training, skill-building, and direct case application through contact with an expert, supervisor, or peer (Nadeem et al., 2013). Participating in more consultation calls has been linked to greater clinician fidelity (Beidas et al., 2012), higher clinician skill (Beidas et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2017), and positive client outcomes (Schoenwald et al., 2003); however, additional research has not supported its effect on client outcomes (Funderburk et al., 2015). Despite the growing body of literature supporting consultation as an implementation strategy, little is known about how it affects sustainability.

The current study sought to contribute to a growing body of literature by examining the impact of training design on the sustainability of PCIT at 24-months (i.e., 12-month post-training), utilizing data from a statewide implementation trial. The first aim of the study was to describe the extent to which clinicians and administrators sustained the use of PCIT at 24-months. It was hypothesized that approximately 60% of clinicians would still be utilizing PCIT, similar to previous reviews (Scheirer, 2005; Stirman et al., 2012). The second aim of the study was to test the direct effects of training design and consultation call attendance on clinician-reported sustainability. It was hypothesized that participating in the LC and CM model and more consultation calls would be associated with higher self-reported sustainability, given previous literature has acknowledged the limitations of brief trainings (e.g., DE) and a lack of ongoing support (Herschell et al., 2010).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of a statewide implementation, cluster randomized-controlled trial of PCIT training following CONSORT guidelines (Herschell et al., 2015). Of the 508 licensed psychiatric outpatient organizations across Pennsylvania identified at the beginning of the study, 94 organizations were eligible to participate once excluding agencies that functioned across multiple counties, did not treat young children, had prior PCIT experience, or served a restricted service population. County administrators from each of the 67 counties were then asked to attend a required informational meeting about the study; ultimately, 50 organizations enrolled in the study.

Each organization selected one administrator, one supervisor, and two clinicians to participate in the study. Administrators eligible to participate had to be employed as an Executive Director, Chief Financial Officer, or be responsible for the organization’s daily operations. Clinicians eligible to participate had to: (a) hold a master’s or doctoral-level degree, (b) be licensed or license-eligible, (c) see a caseload of appropriate PCIT families, (d) have no former PCIT training, and (e) be willing to complete various study tasks. Clinicians were still able to participate in the study if they left their organization over the course of the study. Within the current study, participants included 50 administrators and 100 clinicians from 50 organizations across Pennsylvania. Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Procedure

Design

Enrolled organizations were randomized at the county-level to one of the three training conditions (Herschell et al., 2015). Randomization was balanced based on two covariates (i.e., population density and poverty level), comparable to prior studies that also utilized county-level randomized controlled designs (Aarons et al., 2009; Chamberlain et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010).

Enrollment, randomization, and training occurred in four waves from 2012 through 2015. Five organizations were trained in the first wave, 18 in the second wave, 13 in the third wave, and 14 in the fourth wave. Trainers with expertise in PCIT and disruptive behavior disorders conducted training and consultation calls. Trainers were balanced across training condition and consultation call groups.

Training fidelity checklists were completed at each face-to-face training and consultation calls were structured in order to increase consistency across training waves and conditions. A majority (N = 24; 70.6%) of DE clinicians submitted documentation confirming they completed the online training. Training fidelity checklists were completed for 22 of 30 LC training days, with fidelity ranging from 84 to 100% (M = 96.9%). Training fidelity checklists were completed for 21 of 28 CM training days, with fidelity ranging from 62 to 100% (M = 96.1%).

Training Conditions

The three training conditions included the CM, LC, and DE. All training and consultation calls were completed in 18-months across conditions. Please see Table 2 for more information on each training design and timeline.

As noted above, the CM, commonly referred to as a “Train-the-Trainer” model, is a hierarchical model that involved training two clinicians within an organization as “in-house trainers,” who were then able to train other clinicians within their organization. Clinicians in the CM model attended a 40-h workshop, followed by 16-h of advanced training 6-months later, and ongoing feedback and video review of sessions with a trainer. After 12-months of intensive training, clinicians participated in 6-months of consultation, and were then able to train others within their organization. The CM model aligns with PCIT International’s Training Guidelines and emphasizes clinician-led fidelity to the treatment. An examination of this CM model’s effects on training clinicians within the organization has been published (Brabson et al., 2020).

Clinicians in the LC model began training with a pre-work phase, which involved readings, material review, and conference class. Clinicians then completed three 2-day face-to-face workshops (48 h) over the course of 9 months, with action periods between the workshops involving use of improvement data, technology, and team meetings to facilitate implementation. Within the LC model, team member roles are identified within each organization and cross-site sharing among teams is encouraged. The LC model promotes developing a learning organization that is prepared to implement an intervention.

The DE condition, a web-based training model, involved clinicians completing a 10-h, 11-module online course that utilizes a combination of instruction, video examples, and interactive exercises to train clinicians in the fundamentals of PCIT (University of California, Davis, 2014). Clinicians in this condition did not receive any face-to-face training.

Consultation Calls

Following initial training completion, clinicians in each condition attended up to 24 1-h consultation calls. Consistent with PCIT International training guidelines, clinicians were recommended to attend at least 80% (N = 20) of all consultation calls.

Treatment

Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010) is an EBT for children ages 2.5 to 7-years-old presenting with disruptive behaviors (e.g., oppositional defiance, noncompliance). PCIT has two phases of treatment. The Child-Directed Interaction phase focuses on improving the parent–child relationship. The second phase of treatment, Parent-Directed Interaction, involves teaching developmentally appropriate discipline skills (e.g., effective commands, time-out) to increase compliance.

Compensation

Clinicians received free training, Continued Education Credits, and a monetary incentive for completion of study assessments ($25 for baseline and 6-months, $30 for 12-months, and $40 for 24-months). Organizations received the choice of a PCIT starter kit or a comparable initial stipend ($1000) to cover equipment necessary for providing PCIT within their organization. The University of Pittsburgh and West Virginia University Institutional Review Boards approved all study procedures.

Measures

Sustainability

Clinician sustainability was measured according to three items from the Treatment Implementation Feedback Form (Kolko et al., 2006) and Your Experience-Treatment form at 24-months. Clinicians provided an open-ended response to “Approximately what percentage of your caseload have you used PCIT with?” and “How many families have you yourself provided PCIT for since beginning training?” Clinicians also reported, “How much of the standard PCIT protocol are you still using?” with response options of “Full,” “Parts of it,” and “I am not using it any longer.”

Administrators reported on the sustainability of PCIT within their organization by completing three items from the study-developed EBP Sustaining Telephone Survey at 24-months. Administrators answered an open-ended question “Approximately what percentage of young children (aged 2.5- to 7-years) referred to your agency received PCIT in the last 6 months?” Administrators also responded to a dichotomous question, “Are you still offering PCIT?” with response options of yes or no. Administrators completed a third question that asked, “Are you serving ______ clients with this practice compared to the end of the project” with response options: “considerably fewer,” “about the same,” “a lot more.”

Training and Consultation

Training condition was included as a categorical variable that was dummy-coded. Trainers documented clinician consultation call attendance at each consultation call.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences or Mplus. To examine aim one, rates of sustainability of PCIT according to administrators and clinicians, descriptive statistics (e.g., means, correlations) were conducted on sustainability outcomes.

For aim two, multi-level structural equation modeling with full information maximum likelihood using Mplus was utilized. Clinicians were nested within agencies; therefore, organization was utilized as a clustering variable in aim two. Sustainability was measured as a latent variable using the three individual items of clinician-reported sustainability at 24-months. First, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess measurement fit of sustainability as a latent variable. Model fit was assessed using the χ2/df ratio (CMIN) with values less than three demonstrating good fit, comparative fit index (CFI) with values above 0.95 signifying good fit, Tucker-Lewis Coefficient (TLI), with values close to 1.0 indicating good fit, and root-mean-square-error of approximation (RMSEA) with values less than 0.05 signifying good fit. A path analysis was then conducted with sustainability regressed onto training condition and consultation call attendance. Training condition was dummy coded with DE as the reference condition. Effect sizes were reported using R2 as the coefficient of determination.

Results

Missing Data

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine the amount and patterns of missing data. Missingness on each sustainability item ranged from 39.0 to 55.0% of cases. Little’s MCAR test was statistically significant (p = 0.044), indicating data were not missing completely at random. Separate variance t-tests were conducted to determine patterns of missing data. There were significant t-tests for the number of families enrolled in PCIT and number of EBTs used at baseline as predictors of missingness; therefore, these variables were included within the model as auxiliary variables to strengthen measurement.

Measurement of Sustainability

A CFA was conducted to assess measurement of sustainability as a latent variable. Resulting model fit was poor, χ2 = 182.83, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.84, TLI = 0.77, and RMSEA = 0.17. The CFA also was positive definite, suggesting inadequate power to conduct the analyses. To increase power, the three sustainability items were analyzed as observed variables.

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC’s) were calculated with organization as the between-groups clustering variable. ICC’s ranged from 0.02 to 0.16 on sustainability outcomes. The inclusion of organization as a clustering variable resulted in improved model fit (ΔCFI = 0.08, ΔRMSEA = 0.07).

Rates of Sustainability at 24-Months

A majority (n = 37; 74%) of administrators reported they were still offering PCIT at their organization at 24-months. Administrators stated approximately 10% (SD = 17.31) of young children referred to their organization received PCIT in the last 6 months. Most administrators (n = 21; 57%) noted their organization was serving approximately the same number of clients appropriate for PCIT at 24-months as when training ended. 8 (22%) administrators indicated their organizations were serving considerably fewer clients with PCIT, while 8 (22%) other administrators reported their organization was serving considerably more clients with PCIT. Several administrators (n = 6) reported that although their organization was still offering PCIT, they had not served any families with PCIT in the past year.

On average, individual clinicians reportedly delivered PCIT to 8.3 families (SD = 7.4) and graduated (i.e., met criteria for termination according to the PCIT protocol) 1.3 (SD = 1.7) families since the beginning of training. Clinicians reported using PCIT with approximately 16% (SD = 21.6) of their caseload of young children at 24-months. At 24-months, 73% (n = 41) of clinicians who responded reported they were still using the full PCIT protocol, while 18% (n = 10) of clinicians were using parts of it, and 9% (n = 5) were no longer using it. Table 3 displays the breakdown of clinician-reported sustainability by training condition.

Correlations between clinician- and administrator- reports of sustainability within their organization are displayed in Table 4. There was a moderate positive correlation between administrator and clinicians report of the percentage of eligible children referred to their organization that received PCIT, r (49) = 0.44, p = 0.006. Most correlations were in the low to moderate range, suggesting that there was minimal overlap among these items.

Direct Effects of Training and Consultation on Sustainability

Model Fit

All three sustainability outcomes (24-months) were regressed onto training condition and consultation call attendance. Model fit was good: χ2 = 0.26, p = 0.88, CFI = 1.00 and RMSEA = 0.00.

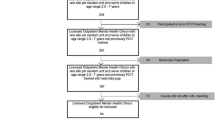

Direct Effects of Training

Figure 1 displays the direct effects of training condition and consultation calls on sustainability. Clinicians in the CM were more likely to have a higher average PCIT caseload at 24-months (β = 0.34, SE = 0.15, p = 0.03) than clinicians in the DE or LC condition; however, there were no statistically significant differences in average PCIT caseload between clinicians in the LC and DE condition at 24-months (p = 0.79). Training conditions did not significantly differ in clinician-reported number of families that received PCIT since beginning training (p = 0.53). Clinicians in the LC were more likely to report using the full PCIT protocol at 24-months than the CM and DE (β = 0.28, SE = 0.11, p = 0.01); however, there were no significant differences in reported PCIT protocol use between the CM and DE (p = 0.70).

Direct Effects of Consultation

Across all training conditions, attending more consultation calls was significantly associated with having delivered PCIT to fewer families since beginning training (β = − 0.25, SE = 0.10, p = 0.009), but not average PCIT caseload (p = 0.75) or reported use of PCIT protocol (p = 0.34) at 24-months.

Effect Size

The overall model accounted for 6% of the variance in average PCIT caseload, 27% of the variance in number of families that received PCIT since beginning training, and 57% of the variance in reported protocol use at 24-months.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the sustainability of PCIT following a statewide training initiative. This study was one of the first, to our knowledge, to empirically examine the effects of training condition in a randomized controlled trial on the sustainability of PCIT within a large-scale service system. This study had two primary aims: (1) to describe rates of sustainability for clinicians and administrators, (2) and to identify the direct effects of training condition and consultation call attendance on sustainability.

Rates of Sustainability

The first aim of this study was to describe the extent to which clinicians and administrators were still using PCIT at 24-months. Most clinicians and administrators believed they were still providing PCIT within their organization and were delivering PCIT to a similar number of clients as when training ended; however, clinicians only graduated an average of 1.3 families after two years. Across training conditions, administrator (74%) and clinician (73%) reported sustainability of PCIT were comparable to previous studies examining sustainability at the same time-point (Bond et al., 2014; Cooper et al., 2015; Scheirer, 2005) as well as past studies of reported sustainability following large-scale rollouts of PCIT (Scudder et al., 2017). While general rates of sustainability for other interventions have been reported to decrease over time (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2016), other large-scale PCIT initiatives have reported that most clinicians provided PCIT 2–3 years after training, with 83.0% of initiatives reporting mid to high levels of overall sustainment (Scudder et al., 2017). It is also important to note that within the current study, approximately one-quarter of clinicians and administrators did not endorse full sustainability of PCIT. While it is possible that these clinicians may have discontinued PCIT, they also could have changed jobs (e.g., promotion to clinical supervisor role) which led to them no longer providing PCIT. Despite these overall high rates of sustainability, it is noteworthy that on average, only 1.3 families completed therapy per clinician. Although clinicians reported high rates of sustainability, levels of attrition and lack of treatment completion within this study are important to consider within future research.

Within the current study, there were small to moderate correlations between clinician and administrator reports of sustainability. These findings are similar to previous studies finding low rates of concordance between administrators and frontline workers (Aarons et al., 2017; Beidas et al., 2018), although these prior studies have focused on perceptions of organizational climate. These low rates of concordance may be due to actual differences in perceptions of sustainability within organizations. For example, while an administrator may report that PCIT is still being offered as an intervention, clinicians within the same organization may not be delivering PCIT. Similarly, administrators may have been reporting on several clinicians, potentially leading to these discrepancies. Therefore, future studies should attempt to identify the most reliable and accurate reporters of sustainability. Furthermore, given that this study measured sustainability 12-months after the completion of training and 6-months after completion of consultation calls, it is also possible that there will be greater variability in sustainability after a longer time-period.

Direct Effects of Training on Sustainability

The second aim of this study focused on the direct effects of training design and consultation call attendance on sustainability outcomes. Clinicians within the CM reported having more PCIT clients at 24-months relative to clinicians in the DE or LC conditions; however, there were no differences across conditions in total number of PCIT cases seen since the beginning of training. This finding that clinicians randomized to the CM design have more PCIT clients at 24-months builds upon previous research suggesting that specific training types may be related to increased sustainability (Herschell et al., 2010). Unique to the CM design, clinicians have within-organization trainers who may be able to help clinicians identify appropriate PCIT cases and provide ongoing supervision. The discrepant finding that clinicians in the CM model may have a greater PCIT caseload at 24-months although no differences in total number of cases seen since beginning training may reflect less dropout in cases seen by CM condition clinicians, a delay in clinicians in the CM condition taking on PCIT client referrals, or possibly measurement error.

This study also found that clinicians in the LC condition were more likely to report using the full PCIT protocol at 24-months in comparison to clinicians in the CM and DE conditions. It was expected that clinicians within the CM condition would demonstrate higher reported use of the PCIT protocol given that clinicians were required to submit videotapes for review; however, this finding was not supported. Given that the LC model emphasizes building core teams that assist in supporting learning, regular team meetings, and emphasizes cross-site collaborations, these strategies could have served as supports that facilitated clinician adherence to the PCIT protocol.

However, this finding is based on self-reported protocol use, and it should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, it is unclear if clinicians in the CM and DE conditions were no longer using PCIT, if they modified the PCIT protocol, or if these differences are due to clinicians’ perspectives as to whether they were fully sustaining the intervention. If they were no longer using the PCIT protocol at all, it is unlikely that these organizations sustained the use of PCIT. On the other hand, if these clinicians were modifying the PCIT protocol based upon client needs, this may lead to greater sustainability given that clinicians who modify a treatment protocol may be more likely to sustain its use for greater periods of time (Stirman et al., 2012). It is important to consider, however, that the extent to which treatment protocols are adapted may alter the efficacy of these interventions (Amaya-Collyer et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 2017; Martinez, 2020).

Clinicians who attended more consultation calls delivered PCIT to a fewer overall number of clients since beginning training. This contrasts with previous research suggesting the importance of consultation as a training component for promoting implementation (Beidas et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2017). Few empirical studies on consultation have examined it in relation to actual use of an intervention and have instead focused on its relation to knowledge and skill (Beidas et al., 2012; Schoenwald et al., 2003). Given that this study did not find consultation calls influenced clinician reported use of PCIT, it is possible that other variables influenced the amount of PCIT provided by clinicians. For example, clinicians who were able to attend more consultation calls may have had a lower overall caseload, were part-time or contractors, and therefore had more time to attend consultation calls. The current study did not measure this directly, so it will be important to consider in future research.

Strengths

This study has several notable strengths that enhance the current body of literature on sustainability. Importantly, this is one of first studies to our knowledge to conduct an experimental manipulation of training design as an implementation strategy to understand sustainability within a large-scale service system. This study also utilized multiple informants within an organization and multiple questions to assess sustainability. This contrasts with previous studies which have primarily relied on a single question from administrators to determine an organization’s sustainability (Stirman et al., 2012). Assessing sustainability through multiple reporters may help refine sustainability research and have greater clinical implications to the field of implementation science.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should also be taken into consideration. Although steps were taken to increase completion of study assessments (e.g., incentives), a large amount of missing data was present at 24-months and the data were not missing completely at random. While the researchers attempted to reduce the effect of missingness through statistical analyses, the results of the current study may have still been impacted by missingness. Similarly, latent variables were unable to be utilized in the current study due to the amount of missing data which resulted in poor model fit of latent variables. The use of latent variables would have strengthened this study due to its ability to increase the robustness of measurement of constructs and its ability to estimate measurement error. Another limitation of the current study was the reliance on self-report and study-developed measures. As has been noted previously, self-report measures may not accurately reflect a clinician’s behavior (Hogue et al., 2014). Therefore, the conclusions drawn from the current study should be interpreted with caution as documented service billing data or behavioral observations were not used to assess use of PCIT. These limitations should be addressed in future research.

Future Directions

Future research can build upon the current study in several ways. While this study was an important step in understanding sustainability’s effect on clinician-reported sustainability, it will be important to link these findings to their effect on client outcomes. This study also revealed that training condition can influence sustainability in varying ways depending upon how sustainability is measured. Further research should continue to understand sustainability as a construct and refine it through additional measurement studies. Within the current study, correlations between administrator and clinician-report were highest among data collected as part of routine practice, suggesting that this type of data may be more accurate. This study’s utilization of both administrator- and clinician-reports of sustainability suggests an important area of research. This study revealed that administrators and clinicians have moderate concordance in their reports of sustainability, and it is unclear whether this is due to the measurement of the construct or differences in reporting bias. Future research should attempt to disentangle this question, and identify which stakeholders are the most accurate reporters of sustainability. Importantly, structural equation modeling approaches should be utilized in future studies to reduce the impact of measurement error on these analyses.

Conclusions

As there are increased efforts to disseminate and implement EBTs, implementation strategies must be refined to enhance the transportability of EBTs into community settings. Understanding factors that improve the sustainability of EBTs is particularly important to increase the public health impact of mental health interventions. Findings from this study suggest that training may significantly influence the extent to which a clinician sustains an intervention; however, this finding is nuanced in that it is dependent on how sustainability is defined and measured. Therefore, organizations seeking to train their clinicians should carefully consider the type of training they decide to pursue based upon their organizational needs and long-term goals for training (i.e., scalability, fidelity). The type of training an organization is involved in may play a significant role in the number of families that ultimately have access to empirically supported treatments.

References

Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., Torres, E. M., Finn, N. K., & Beidas, R. S. (2017). The humble leader: association of discrepancies in leader and follower ratings of implementation leadership with organizational climate in mental health. Psychiatric Services, 68(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600062

Aarons, G. A., Wells, R. S., Zagursky, K., Fettes, D. L., & Palinkas, L. A. (2009). Implementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: A multiple stakeholder analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 99(11), 2087–2095. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.161711

American Diabetes Association. (2004). The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. Diabetes Spectrum, 17(2), 97–101.

Bearman, S. K., Schneiderman, R. L., & Zoloth, E. (2017). Building an evidence base for effective supervision practices: An analogue experiment of supervision to increase EBT fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0723-8

Beidas, R. S., Edmunds, J. M., Marcus, S. C., & Kendall, P. C. (2012). Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 63(7), 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100401

Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x

Beidas, R. S., Williams, N. J., Green, P. D., Aarons, G. A., Becker-Haimes, E. M., Evans, A. C.,...Marcus, S. C. (2018). Concordance between administrator and clinician ratings of organizational culture and climate. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(1), 142-151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0776-8

Bond, G. R., Drake, R. E., McHugo, G. J., Peterson, A. E., Jones, A. M., & Williams, J. (2014). Long-term sustainability of evidence-based practices in community mental health agencies. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0461-5

Brabson, L. A., Herschell, A. D., Snider, M. D., Jackson, C. B., Schaffner, K. F., Scudder, A. T.,...Mrozowski, S. J. (2020). Understanding the effectiveness of the cascading model to implement parent-child interaction therapy. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-020-09732-2

Brookman-Frazee, L., Stadnick, N., Roesch, S., Regan, J., Barnett, M., Bando, L.,…Lau, A. (2016). Measuring sustainment of multiple practices fiscally mandated in children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 1009–1022.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0731-8

Brown, C. H., Chamberlain, P., Saldana, L., Padgett, C., Wang, W., & Cruden, G. (2014). Evaluation of two implementation strategies in 51 child county public service systems in two states: Results of a cluster randomized head-to-head implementation trial. Implementation Science, 9(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0134-8

Bunger, A. C., Hanson, R. F., Doogan, N. J., Powell, B. J., Cao, Y., & Dunn, J. (2016). Can learning collaboratives support implementation by rewiring professional networks? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0621-x

Calder, R., Ainscough, T., Kimergard, A., Witton, J., & Dyer, K. R. (2017). Online training for substance misuse workers: A systematic review. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 24, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2017.1318113

Chamberlain, P., Brown, C. H., Saldana, L., Reid, J., Wang, W., Marsenich, L.,...Bouwman, G. (2008). Engaging and recruiting counties in an experiment on implementing evidence-based practice in California. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(4), 250–260.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0167-x

Collyer, H., Eisler, I., & Woolgar, M. (2019). Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the relationship between adherence, competence and outcome in psychotherapy for children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1265-2

Cooper, B. R., Bumbarger, B. K., & Moore, J. E. (2015). Sustaining evidence-based prevention programs: Correlates in a large-scale dissemination initiative. Prevention Science, 16(1), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0427-1

Deblinger, E., Pollio, E., Cooper, B., & Steer, R. A. (2020). Disseminating trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with a systematic self-care approach to addressing secondary traumatic stress: PRACTICE what you preach. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(8), 1531–1543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00602-x

Dopp, A. R., Hanson, R. F., Saunders, B. E., Dismuke, C. E., & Moreland, A. D. (2017). Community-based implementation of trauma-focused interventions for youth: Economic impact of the learning collaborative model. Psychological Services, 14(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000131

Edmunds, J. M., Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2013). Dissemination and implementation of evidence–based practices: Training and consultation as implementation strategies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(2), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12031

Eyberg, S. M., & Funderburk, B. (2011). Parent-child interaction therapy protocol. PCIT International.

Funderburk, B., Chaffin, M., Bard, E., Shanley, J., Bard, D., & Berliner, L. (2015). Comparing client outcomes for two evidence-based treatment consultation strategies. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(5), 730–741.

Glisson, C., Schoenwald, S. K., Kelleher, K., Landsverk, J., Hoagwood, K. E., Mayberg, S.,...Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2008). Therapist turnover and new program sustainability in mental health clinics as a function of organizational culture, climate, and service structure. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1–2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0152-9

Hanson, R. F., Saunders, B. E., Ralston, E., Moreland, A. D., Peer, S. O., & Fitzgerald, M. M. (2019). Statewide implementation of child trauma-focused practices using the community-based learning collaborative model. Psychological Services, 16(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000319

Helseth, S. A., Peer, S. O., Are, F., Korell, A. M., Saunders, B. E., Schoenwald, S. K.,...Hanson, R. F. (2020). Sustainment of trauma-focused and evidence-based practices following learning collaborative implementation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01024-3

Herschell, A. D., Kolko, D. J., Baumann, B. L., & Davis, A. C. (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005

Herschell, A. D., Kolko, D. J., Scudder, A. T., Taber-Thomas, S., Schaffner, K. F., Hiegel, S. A.,…Mrozowski, S. (2015). Protocol for a statewide randomized controlled trial to compare three training models for implementing an evidence-based treatment. Implementation Science, 10(1), 133.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0324-z

Hogue, A., Dauber, S., Henderson, C. E., & Liddle, H. A. (2014). Reliability of therapist self-report on treatment targets and focus in family-based intervention. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(5), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0520-6

Jackson, C. B., Herschell, A. D., Schaffne, K. F., Turiano, N. A., & McNeil, C. B. (2017). Training community-based clinicians in parent-child interaction therapy: The interaction between expert consultation and caseload. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(6), 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000149

Jackson, C. B., Quetsch, L. B., Brabson, L. A., & Herschell, A. D. (2018). Web-based training methods for behavioral health providers: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0847-0

Kolko, D. J., Herschell, A. D., & Baumann, B. L. (2006). Treatment implementation feedback form. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Lang, J. M., Ake, G., Barto, B., Caringi, J., Little, C., Baldwin, M. J.,...Stevens, K. (2017). Trauma screening in child welfare: Lessons learned from five states. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10(4), 405–416.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0155-y

Loman, S. L., Rodriguez, B. J., & Horner, R. H. (2010). Sustainability of a targeted intervention package: First step to success in Oregon. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 18(3), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426610362899

Markiewicz, J., Ebert, L., Ling, D., Amaya-Jackson, L., & Kisiel, C. (2006). Learning collaborative toolkit. National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Martinez, R. G. (2020). A meta-analysis investigating the correlation between treatment integrity and youth client outcomes. (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA). Retrieved from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6345/

Martino, S., Ball, S. A., Nich, C., Canning-Ball, M., Rounsaville, B. J., & Carroll, K. M. (2011). Teaching community program clinicians motivational interviewing using expert and train-the-trainer strategies. Addiction, 106(2), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03135.x

Martino, S., Brigham, G. S., Higgins, C., Gallon, S., Freese, T. E., Albright, L. M., … Condon, T. P. (2010). Partnerships and pathways of dissemination: The National Institute on drug abuse—Substance abuse and mental health services administration blending initiative in the clinical trials network. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 38(Suppl 1), S31–S43.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.013

McMillen, J. C., Hawley, K. M., & Proctor, E. K. (2016). Mental health clinicians’ participation in web-based training for an evidence supported intervention: Signs of encouragement and trouble ahead. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(4), 592–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0645-x

McNeil, C. B., & Hembree-Kigin, T. L. (2010). Parent-child interaction therapy. Springer.

Nadeem, E., Gleacher, A., & Beidas, R. S. (2013). Consultation as an implementation strategy for evidence-based practices across multiple contexts: Unpacking the black box. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(6), 439–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0502-8

Powell, B. J., McMillen, J. C., Hawley, K. M., & Proctor, E. K. (2013). Mental health clinicians’ motivation to invest in training: Results from a practice-based research network survey. Psychiatric Services, 64(8), 816–818. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.003602012

Powell, B. J., Mcmillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., Christopher, R., Griffey, R. T., Bunger, A. C.,…York, J. L. (2013). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical Care Research and Revieware Research and Review, 69(2), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558711430690.A

Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M.,…Kirchner, J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A.,…Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

Scheirer, M. A. (2005). Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. American Journal of Evaluation, 26(3), 320–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005278752

Schell, S. F., Luke, D. A., Schooley, M. W., Elliott, M. B., Herbers, S. H., Mueller, N. B., & Bunger, A. C. (2013). Public health program capacity for sustainability: A new framework. Implementation Science, 8, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-15

Schoenwald, S. K., Sheidow, A. J., & Letourneau, E. J. (2003). Toward effective quality assurance in evidence-based practice: Links between expert consultation, therapist fidelity, and child outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33(1), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_10

Scudder, A. T., Taber-Thomas, S. M., Schaffner, K., Pemberton, J. R., Hunter, L., & Herschell, A. D. (2017). A mixed-methods study of system-level sustainability of evidence-based practices in 12 large-scale implementation initiatives. Health Research Policy and Systems, 15(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0230-8

Shelton, R. C., Cooper, B. R., & Stirman, S. W. (2018). The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annual Review of Public Health, 39, 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731

Shore, B. A., Iwata, B. A., Vollmer, T. R., Lerman, D. C., & Zarcone, J. R. (1995). Pyramidal staff training in the extension of treatment for severe behavior disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1995.28-323

Stirman, S., Kimberly, J., Cook, N., Calloway, A., Castro, F., & Charns, M. (2012). The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-17

University of California, Davis. (2014). PCIT Web Course. Retrieved from https://pcit.ucdavis.edu/pcit-web-course/

Wang, W., Saldana, L., Brown, C. H., & Chamberlain, P. (2010). Factors that influenced county system leaders to implement an evidence-based program: A baseline survey within a randomized controlled trial. Implementation Science, 5(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-72

Zandberg, L. J., & Wilson, G. T. (2013). Train-the-trainer: Implementation of cognitive behavioural guided self-help for recurrent binge eating in a naturalistic setting. European Eating Disorders Review, 21(3), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2210

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, C.B., Herschell, A.D., Scudder, A.T. et al. Making Implementation Last: The Impact of Training Design on the Sustainability of an Evidence-Based Treatment in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Adm Policy Ment Health 48, 757–767 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01126-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01126-6