Abstract

Clubhouses are recovery centers that help persons with serious mental illness obtain and maintain community-based employment, education, housing, social integration, and other services. Key informants from U.S. clubhouses were interviewed to create a conceptual framework for clubhouse sustainability. Survival analyses tested this model for 261 clubhouses. Clubhouses stayed open significantly longer if they had received full accreditation, had more administrative autonomy, and received funding from multiple rather than sole sources. Cox regression analyses showed that freestanding clubhouses which were accredited endured the longest. Budget size, clubhouse size, and access to managed care did not contribute significantly to sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“A program is a set of resources and activities directed toward one or more common goals…” (Wholey et al. 2010, p. 5). Without resources such as money, staff, and facilities, activities become impossible to maintain and programs close. Access to the variety of resources necessary to sustain program activities may depend on a variety of socio-political-economic factors. Sustainability has many definitions (Bamberger and Cheema 1990; Pluye et al. 2004; Yin and Quick 1979). Different definitions are frequently used to account for specialized content included in each evaluation (Scheirer and Dearing 2011). Scheirer (2005) noted that in 19 studies which measured program sustainability, most used different definitions. Five studies did not define program sustainability at all. The present study simply defined sustainability as the ability of a program to continue providing its services.

Clubhouse Model

We examined potential determinants of sustainability for clubhouse programs, an established evidence-based practice included in the National Registry of Evidence Based Practices and Programs maintained by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2015). Clubhouses are voluntary psychosocial rehabilitation programs for adults and young adults diagnosed with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) who may be in transition from halfway houses, day programs, or hospitals, or who already may be living in the community (Glickman 1992; Levin 2012). Members (participants) of a clubhouse not only use services but also collaborate with program staff to perform tasks essential to the operation of the clubhouse, such as cooking meals, tracking statistics, and providing services to other members (Mowbray et al. 2006). Clubhouses help members meet their needs for health, education, social connections, transportation, and housing (Macias et al. 2001). Clubhouses focus many resources on helping members enter into community-based employment (McKay et al. 2007).

The first clubhouse, Fountain House, began in 1948 (Aquila et al. 1999). Now there are over 325 clubhouse programs located in 33 countries and 36 states in the U.S. (Clubhouse International 2014). Clubhouses can operate as freestanding entities—independent clubhouses—or can be managed by another program—auspiced clubhouses. Auspiced clubhouses commonly function within community health centers, hospitals, municipal governments, county governments, and other agencies.

Both independent and auspiced clubhouses receive technical assistance and accreditation from Clubhouse International. Clubhouse International began in 1994 as the International Center for Clubhouse Development or ICCD. It evolved from a 1976 National Institute of Mental Health grant and the 1988 National Clubhouse Expansion Program (Clubhouse International 2015a). Clubhouse International now has ten bases in five countries that offer 3-week in vivo training in the clubhouse model (Clubhouse International 2015b). Clubhouse International also accredits clubhouses via site visits and collection of data on clubhouse operations (Macias et al. 1999). The Faculty for Clubhouse Development are staff and members of accredited clubhouses who participate in training and accreditation. We interviewed clubhouse faculty to isolate possible determinants of clubhouse sustainability. The structure of these interviews was based in part on the research literature on sustainability of human services.

Determinants of Program Sustainability

Meyer and Rowan (1977) suggested that sustainability might be enhanced by adherence of an organization to institutional policies, such as the standards developed by Clubhouse International and assessed in clubhouse training and accreditation. Crittenden (2000) examined additional potential determinants of sustainability in 31 nonprofit social service organizations, including their strategic processes (e.g., “emphasized marketing,” “competitively oriented,” “examined new funding opportunities”), strategy content (e.g., “grow client usage,” “grow offerings,” “increase donations”), and funding sources (e.g., “diversified funding,” “relied on an endowment,” “relied on government funds”). Crittenden found that the most enduring programs had (a) goals to increase the number of clients, (b) service offerings and strategic activities related to program goals, (c) fundraising efforts directed toward a specific market, and (d) diverse funding sources.

As detailed by McKay et al. (2007), funding varies considerably between clubhouses within the US and other countries. In US and other countries, the majority clubhouse funding is received from a mixture of state or provincial and local governments, followed by public health insurance. Private sources contribute the rest, with most being philanthropic foundations rather than direct payments from individuals or families.

Additional determinants of sustainability related to funding have been investigated. A threshold of resources may need to be reached before a program can begin operations, but the amount of initial funding does not always predict program survival. Savaya and Spiro (2012) tested a comprehensive model of sustainability for 197 social projects, finding that the amount of initial funding was not predictive of program continuation. Savaya and Spiro also found that project continuation was strongly and positively related to involvement of the initial primary funder, commitment and support of the auspice agency, and, again, diversity of funding.

We used qualitative as well as quantitative methods to understand what determines sustainability of clubhouses (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004). Grounded in the research literature summarized above, an interviewer allowed themes of sustainability to emerge from open-ended questioning of key informants (cf. Auerbach and Silverstein 2003). Variables in the Clubhouse International database that most closely represented determinants about which consensus had been achieved in the qualitative study were compared quantitatively and tested statistically for prediction of clubhouse endurance.

Method

This retrospective multi-site study was approved by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at all institutions involved. Qualitative data were collected from key informants via individual telephone interviews between December 2013 and March 2014. These data were analyzed to determine which potential quantitative determinants of sustainability to extract from data provided by clubhouses from 1994 to 2013.

Participants

Key Informants

Semi-structured one-on-one telephone interviews were conducted with seven key informants (2 women, 5 men) from the U.S. Clubhouse International faculty: six clubhouse directors and a member of a seventh clubhouse who served on its board of directors.

Clubhouses

Quantitative data were provided by 282 U.S. clubhouses responding to surveys between 1994 and 2013. Inclusion criteria were consistent with previous research (McKay et al. 2005, 2007): affiliation with Clubhouse International, declared use of the clubhouse model, serving more than 15 members, and providing data for one or more of the variables investigated, e.g., budget, accreditation level, start date, and other critical data. Only data from U.S. clubhouses were used because research by McKay et al. (2007) had found funding of clubhouses to be considerably different inside and outside the US, potentially obscuring some potential determinants of sustainability.

Measures

Clubhouse Faculty Interview (CFI)

Designed for the qualitative study by the first author, the CFI (Online Appendix A) was a seven-page guide to capturing opinions and experiences regarding sustainability from key informants from Clubhouse International faculty. The guide included an introduction, open interview questions, probing questions, and content inquiries.

Clubhouse Profile Questionnaire (CPQ)

Clubhouses provided data on operations to Clubhouse International via the 130-item CPQ. First appearing in paper format in 1994, the electronic version of the CPQ was developed at the University of Massachusetts Medical School with input from clubhouse members employed as research assistants in the Program for Clubhouse Research (PCR; Clubhouse International 2013). Clubhouse International uses the CPQ to assess quality, improve programs, monitor training and accreditation, and track development of the clubhouse model over time. The CPQ collected information from individual clubhouses on essential characteristics (e.g., number of members), accreditation status, management practices and governance (e.g., how decisions are made), staffing and staff credentials, funding sources and amounts, vocational supports and member employment, supported education activities, member housing, other services provided, participation in clubhouse training, and research activities at the clubhouse.

Procedure and Data Analysis Plan

Qualitative Study

Following approval by all IRBs, the PCR Director emailed a request for key informants (Online Appendix C) to all U.S. Clubhouse International faculty (Online Appendix D).

Interviews

Phone interviews were conducted for up to 90 min with individual faculty who had expressed interest to the first author and had provided informed consent. After interviewing the first faculty member, the first author and an advanced undergraduate research assistant refined the CFI and the codebook described below. The assistant then transcribed the first two interviews so as to omit all personal identifying information (e.g., informant name, clubhouse affiliation). Following each subsequent interview, the first author used NVivo 9 (QSR International 2010) to identify words, phrases, and themes expressed by each informant to describe determinants of clubhouse sustainability. Additional interviews were conducted until concept saturation was achieved, i.e., until no new information, themes, descriptions of a concept, or terms were presented by participants, as detailed in Leidy and Vernon (2008).

Coding and Intercoder Reliability

The codebook (Online Appendix E) was created by the first author to identify response patterns by associating specific words and phrases in transcripts with themes expressed by informants. Following recommendations of Miles and Huberman (1994, p. 56; see also MacQueen et al. 1998), the codebook included brief definitions of each theme code, guidelines for when to use each code, and examples of code use (Online Appendix F). Transcripts for 28 % of the informants were analyzed by both the first author and research assistant with significant agreement, i.e., a mean kappa coefficient of .78. This exceeded the .75 kappa threshold for coder agreement recommended by Cohen (1960), cf. Banerjee et al. (1999) and Hruschka et al. (2004) (Online Appendix G).

Quantitative Study

Quantitative variables were selected from the CPQ to best represent sustainability determinants identified by key informants. For example, informants reported that adherence to the clubhouse model was important for sustainability because clubhouse accreditation status signifies compliance with the International Clubhouse Standards and a commitment to clubhouse excellence (Clubhouse International 2015c). Accreditation levels reported in the CPQ were used in quantitative analyses of clubhouse longevity.

Following identification of quantitative variables that best represented themes found in the qualitative study, survival analyses of the most recent data for each clubhouse assessed the statistical significance of different candidate predictors of clubhouse “lifetime,” i.e., months between opening and closing dates of the clubhouse as of January 1, 2014 (SPSS; version 22, IBM Corp, 2013). Kaplan–Meier estimators (Kaplan and Meier 1958) quantified relationships between clubhouse lifetime and potential predictors (Collett 2003) using the log rank test (Mantel 1966). These analyses gave equal weight to each failure time (Mills 2011, p. 82; cf.; Rich et al. 2010). A Cox failure rate regression model incorporating these variables then assessed the contributions of each factor to clubhouse lifetime in a multivariable framework (Bellera et al. 2010).

As detailed by Wright (2000), survival analyses was chosen for this study because it was originally designed, and is uniquely suited, to deal with data from participants (clubhouses in this study) that continue to survive when the data collection period of a study comes to an end. This is analogous to cancer patients who continue to survive at the end of a clinical trial: survival analysis includes them in the analysis, projecting how long they would survive given the survival rates of other patients and the other factors included in the analysis.

Failure rate regression analysis, often termed Cox regression, compares the value of covariates within each risk period and then combines them over the time at risk periods. Clubhouses originating earlier had longer periods of observed risk, but the ones remaining open had attributes that, in each risk period, were negatively associated with termination for that time period. Earlier clubhouses allowed observation for more extended periods, providing information to the survival function and the regression analysis based on it. Their covariate pattern was evaluated at that risk point by the survival analysis and made part of the estimation of the final model, along with estimates for clubhouses that began later and thus had less time available to close. Essentially, Cox regression “controls” for this factor as a function of how its algorithm is constructed.

Results

Qualitative Findings

Informants

The key informants represented four geographic areas of the United States: continental Northeast, Midwest, and Mid-Atlantic as well as Pacific Islands. Key informants had been clubhouse members for a median 20 years (range: 1–25). Informants had served on the Clubhouse International faculty for a median 6 years (range: 2–20). Informants’ clubhouses varied considerably in size, from 24 to 350 active members (median: 270).

A concept saturation grid (Table 1) and quote table (Supplementary Table I) organized responses from key informants to show whether additional informants needed to be interviewed (cf. Brod et al. 2009). The sustainability concepts identified were: (a) accreditation, (b) a supportive auspice agency or board of directors, (c) diversity of funding, (d) clubhouse effectiveness, (e) advocacy, (f) renewable or steady funding, and (g) resilient and forward-thinking clubhouse director. As expected, several quantitative variables could not be found in the CPQ to represent the sustainability variables identified by qualitative analyses, i.e., the last four listed above (Online Appendix J).

Accreditation

Key informants reported that partial as well as complete accreditation indicated adherence to the clubhouse model. Accreditation was described as important for continued operation of and advocacy for the clubhouse, because accreditation legitimized the clubhouse and was a proxy for effective programming and employment services for clubhouse members.

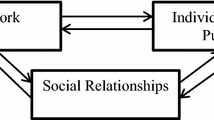

Management Structure: Supportive Auspice Agency or Supportive Board

Informants explained that clubhouses were auspiced, i.e., managed by another organization, or independent, i.e., operating autonomously and usually with oversight by a board of directors. All four informants from auspiced clubhouses suggested that if a clubhouse was auspiced, a supportive auspice agency was essential to sustainability. Informants associated unsupportive auspice agencies with difficulties involving membership, staff recruitment, and funding. Key informants described supportive auspice agencies as helping with funding, referrals, programming, training, and adapting to the unique structure and billing procedures of the clubhouse. Informants from independent clubhouses suggested that a supportive board of directors had access to funding opportunities, facilitated funding of the clubhouse, was politically active in the community, advocated for the clubhouse, and had community access that could help the clubhouse gain members.

Diversity and Type of Funding

Having a variety of funding sources, possibly managed care, was reported to be important for long-term sustainability. Key informants affirmed the dangers of relying too heavily on one funding source, e.g., state funds, Medicaid, or a single grant.

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative Characteristics of Clubhouses

The CPQ was completed by 282 clubhouses as of January 1, 2014, when the following analyses were performed. The median year for CPQs was 2006, ranging from 1994 to 2013. After adjusting inflation to 2013 levels (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014), the median annual clubhouse budget was $500,214. Table 2 provides details for these clubhouses.

Clubhouse Lifespan

The start date for a clubhouse was when it began operation; the end date was when it closed. Start dates ranged from 1961 to 2012. One clubhouse was 4.7 standard deviations above the mean in months of operation and 11 standard deviations above the mean for clubhouse budget: this outlier was excluded from further analyses (Online Appendix H). Months in operation was right-censored (Bagdonavicus et al. 2013) for the 166 (64 %) clubhouses that continued to operate after the cessation of data collection on January 1, 2014.

Sustainability concepts for which quantitative variables were found in the CPQ were (1) accreditation level, (2) clubhouse management structure, (3) diversity of funding, and (4) absence or presence of a managed care system that could be billed.

Accreditation

Following site visits and other accreditation activities, clubhouses were awarded an accreditation status by Clubhouse International. Clubhouses could remain unaccredited, or receive a 1-year, conditional 3-year, or full 3-year accreditation. We found that 1-year accredited clubhouses accounted for only 7 % (n = 20) of all clubhouses with CPQs (N = 281). We removed these clubhouses from further analyses because to retain them would have violated the proportionality assumption of survival analysis, i.e., that hazard between accreditation levels should remain proportional over time (Kleinbaum and Klein 2012). Because conditional 3-year accreditation indicated that only minor changes were needed to reach full 3-year accreditation, we combined these clubhouses for a total of 97 (37 %) accredited at 3-year levels and 164 (63 %) unaccredited. Survival analyses estimated that accredited clubhouses had significantly longer lifespans, i.e., from 463 to 572 versus 248 to 304 months (Fig. 1), Z = 30.83, N = 261, p < .001. Accredited clubhouses had a 0.89 probability of operating for the overall median of 229 months, whereas unaccredited clubhouses had a 0.57 probability of sustaining (Supplementary Table K1).

Management Structure

Of the 259 clubhouses that described their management structure, 129 (49.8 %) were auspiced. Survival analyses estimated that whereas auspiced clubhouses sustained from 227 to 286 months, independent clubhouses sustained significantly longer, i.e., from 455 to 574 months, Z = 47.83, N = 259, p < .001 (Fig. 2). Independent clubhouses were significantly more likely than auspiced clubhouses to endure, with probabilities of survival of 0.89 versus 0.52 for the overall median of 229 months (Supplementary Table K2).

Diversity of Funding, Managed Care

We set 6 % of a clubhouse budget as the minimum for a funding source to be considered distinct, because that was the percent of the median clubhouse budget that would fund one full-time direct-service employee (Gorman 2012). The 125 clubhouses (48 %) reporting sources for at least 80 % of their funding received money from one to six distinct sources. Survival analysis estimated that the 79 clubhouses with one funding source sustained 259 to 337 months, whereas the 46 clubhouses with multiple funding sources sustained a significantly longer 291 to 349 months (Fig. 3), Z = 6.89, N = 125, p = .009 (Supplementary Table K3). Clubhouses with a single funding source had a probability of 0.63 of operating for the overall median of 229 months, whereas clubhouses with multiple funding sources had a 0.85 probability of operating for the same duration.

Also, of the 261 clubhouses, 80 (31 %) had access to a managed care system, e.g., Medicaid. Survival analyses did not find a significant difference in longevity of clubhouses with or without access to managed care, Z = 2.24, N = 261, p = .135.

Multiple Determinants of Sustainability

Cox model regression analyses for clubhouse lifetime included clubhouse management structure, accreditation, diversity of funding, and annual clubhouse budget. Budget was added because McKay et al. (2007) had found a significant positive relationship between accreditation and clubhouse budget, and because we found annual budget to be significantly and positively related to the clubhouse longevity, r = .32, p < .001, N = 221. Adding clubhouse size (number of active members) to the model did not yield a significant relationship between size and clubhouse longevity, p = .141. The Cox model showed that of the four potential determinants in this model, auspiced versus independent clubhouse management structure and unaccredited versus 3-year accreditation status were significant, positive predictors of clubhouse sustainability (Table 3). Relative risk of clubhouse closure was reduced 77 % if clubhouse management was independent. Relative risk for clubhouse closure was reduced by 28 % when clubhouses held 3-year accreditation. This variable had the strongest effect on clubhouse survival of any variable in the model. Including clubhouse budget in this multivariate model did not contribute additional prediction of sustainability. Adding the outlier clubhouse with its high budget and longevity also did not change these findings (Online Appendix L).

Interaction of Accreditation and Management

Given the prominence of accreditation level and clubhouse management structure in the Cox analyses, we examined their possible interaction. It was significant, X 2 (1, N = 259) = 47.61, p < .001. More specifically, over 3.5 times as many clubhouses with a 3-year accreditation level were independent, n = 75, instead of being auspiced, n = 21. Of the independent clubhouses, 75 had a 3-year accreditation level but only 55 were unaccredited. Of the auspiced clubhouses, only 21 had a 3-year accreditation level and 108 were unaccredited. Kaplan–Meier estimates found that auspiced clubhouses without accreditation sustained between 209 and 274 months, whereas independent clubhouses with 3-year accreditation sustained significantly longer, i.e., between 486 and 615 months, both after adjusting for accreditation level, Z = 23.4, N = 259, p < .001, and after adjusting for clubhouse management structure, Z = 8.37, N = 259, p = .004. Put another way, whereas auspiced clubhouses without accreditation had less than an even chance (0.49 probability) of sustaining operations for the overall median of 229 months, independent clubhouses with 3-year accreditation had a much better than even change (0.95 probability) of sustaining operations (Table 4).

Discussion

Sustainability Models

Our mixed-methods (qualitative-then-quantitative) approach to understanding sustainability of community-based programs for persons with SMI suggested that both accreditation level and clubhouse management structure had substantial impacts on program sustainability, whereas size of clubhouse budget and diversity of funding did not. The Cox model showed independent clubhouses were 1.77 times more likely to sustain than auspiced clubhouses, and that 3-year accredited clubhouses were 1.28 times more likely to sustain than unaccredited clubhouses.

Clubhouse Accreditation

We also found that clubhouses accredited at 3-year levels stayed open 242 months longer than unaccredited clubhouses. This was not because Clubhouse International closed the unaccredited clubhouses: there was no financial or legal mechanism for Clubhouse International to close programs that did not pay dues and that remained unaffiliated, or that called themselves clubhouses but had not fully implemented the model and were not accredited. It does seem possible that meeting the expectations of the clubhouse model may have increased program credibility from the perspective of potential funders, improving advocacy, grants, member recruitment, and other factors that could in turn help clubhouses adapt to changes in community needs and funding. It also seems likely that accreditation indicates greater fidelity to the model that clubhouses have found to be effective (cf. Macias et al. 2001; Wang et al. 1999): one would hope and expect that the more a program adheres to a model developed over decades of trial and error, the longer it could continue operating (e.g., Swain et al. 2010). Certainly, fidelity to models seems positively correlated with effective programs that have goals overlapping with clubhouse goals (e.g., Bond et al. 2012).

Clubhouse Management Structure

We found that independent clubhouses sustained twice as long as auspiced clubhouses, i.e., 257 months longer. This was unanticipated: auspice agencies typically provide space, finances, and other resources, e.g., billing, supplies, agency van, payroll and employee benefits, for clubhouses. We conjecture that the oversight which often accompanies affiliation with an auspice agency reduced the ability of clubhouses to allocate resources to adapt to changes in local employment and funding circumstances, and to maintain a degree of administrative independence that may be integral to the clubhouse model. Also, it is possible that some of the auspice agencies were unwilling to pay for clubhouse training or the accreditation process as they may have had competing demands and interests.

Diversity of Funding, Access to Managed Care

According to Kaplan–Meier comparisons, clubhouses with two or more funding sources sustained somewhat longer, i.e., 22 months, than clubhouses with only one funding source. Multiple funding sources could protect a clubhouse from closing if its sole funding source lost its assets or decided to stop supporting the clubhouse. However, when accreditation and clubhouse management structure were included in Cox modeling, the positive contribution of more diversity of funding ceased to be significant. It is possible that the benefits of receiving funding from multiple sources were overshadowed by and possibly confounded with effects of clubhouse accreditation and management structure.

We were surprised that access to a managed care system did not significantly improve clubhouse sustainability. Several key informants had noted that steady, renewable funding was helpful for sustainability, yet managed care systems did not to contribute quantitatively to sustainability. This could be due to the variability of quality of managed care systems in the U.S.: some may make a substantial positive contribution to clubhouse longevity while others may not meet the somewhat unique needs of the clubhouse model. Supporting this interpretation, key informants had noted that paperwork required by medically-oriented billing systems of some managed care organizations could be particularly burdensome. Key informants also reported that specific billing codes available in some management care systems matched only a subset of services provided by clubhouses, which could impact clubhouse funding negatively rather than positively.

Limitations and Qualifications

We can and should note several limitations in our research. Because CPQ data were provided by clubhouses from 1994 to 2014, changing sociopolitical and economic factors probably added substantial “noise” to our findings. Also, this study used data provided by clubhouses for single years: data for multiyear periods might better represent the many potential determinants that could have maintained or closed clubhouses. For example, diversity of funding data were for the single year for which the clubhouse completed the CPQ. Furthermore, no information was available about whether funding was for 1 year or several.

In addition, clubhouses may be unaccredited for reasons other than inability to comply with Clubhouse International standards, e.g., a clubhouse may have been too new to have fully implemented the model. Also, a program may not have committed to completely implementing the clubhouse model. We further note that accreditation can take several years for a clubhouse to attain: more established clubhouses might be more likely to achieve and maintain accreditation. As a result, higher accreditation might reflect rather than predict longevity in more established clubhouses. However, we found that closed clubhouses in our study had operated for a mean of 197.13 (SD = 9.927) months (median = 208 months), more than enough time to become accredited. Clubhouse International provides new clubhouses with adequate time to establish a firm foundation and implement all aspects of the model prior to seeking accreditation. Typically, after about 2 years of initial operations, a new clubhouse can request accreditation. The accreditation process usually takes 6–9 months to complete (Joel Corcoran, personal communication).

A final limitation, common in community-based research, was missing data. Of the auspiced clubhouses, 72 had missing data. Including diversity of funding in our analyses reduced N from 219 to 117. Not providing data on diversity of funding cannot be interpreted as due to any one factor, however, prompting us to be less confident about positive or negative findings for this variable.

Future Directions

This research attempted to identify determinants that enable clubhouses to maintain operations over time via qualitative study which generated findings that were then tested quantitatively with archival data. The qualitative interviews were not designed to form a complete conceptual framework, but simply to identify sustainability predictor variables until saturation criteria were met. Future research could expand the qualitative work with more interviews, and by including staff and members of clubhouses that operated for different durations. Future studies also could interview directors and members of clubhouses that closed, to ask them about key determinants of clubhouse closure.

Although our informants identified sustainability determinants that were easily quantified with existing data, other determinants did not map well onto the quantitative variables available. For example, diversity of funding was quantified by simply counting the number of funding sources that produced the annual clubhouse budget, whereas quantifying level of support from an auspice agency was not represented by any specific CPQ item. Clubhouse effectiveness was similarly difficult to quantify.

Finally, we note that the CPQ was not designed to collect information about sustainability. Perhaps a revision of it could be! Potential quantitative representations of sustainability determinants might include the perceived relationship between a clubhouse and its board of directors or auspice agency, specific difficulties experienced by the clubhouses (e.g., recruiting members, billing services, training staff, transportation services), and advocacy indicators (e.g., number of flyers distributed, number community outreach events held). Completion of the CPQ annually by more clubhouses also could yield data for more comprehensive analyses of sustainability determinants. It is our hope that this and other research can better prepare clubhouses to navigate demanding, changing fiscal and political environments so they are available to serve more members for longer periods.

References

Aquila, R., Santos, G., Malamud, T. J., & McCrory, D. (1999). The rehabilitation alliance in practice: The clubhouse connection. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 23, 19–24. doi:10.1037/h0095199.

Auerbach, C., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York: New York University Press.

Bagdonavicus, V., Kruopis, J., & Nikulin, M. (2013). Nonparametric tests for censored data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Bamberger, M., & Cheema, S. (1990). Case studies of project sustainability: Implications for policy and operations from Asian experience. Washington, DC: Economic Development Institute, World Bank.

Banerjee, M., Capozzoli, M., McSweeney, L., & Sinha, D. (1999). Beyond kappa: A review of interrater agreement measures. Canadian Journal of Statistics, 27(1), 3–23.

Bellera, C. A., MacGrogan, G., Debled, M., de Lara, C. T., Brouste, V., & Mathoulin-Pélissier, S. (2010). Variables with time-varying effects and the Cox model: Some statistical concepts illustrated with a prognostic factor study in breast cancer. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10, 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-10-20.

Bond, G. R., Peterson, A. E., Becker, D. R., & Drake, R. E. (2012). Validation of the revised individual placement and support fidelity scale (IPS-25). Psychiatric Services, 63(8), 758–763. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100476.

Brod, M., Tesler, L. E., & Christensen, T. L. (2009). Qualitative research and content validity: Developing best practices based on science and experience. Quality of Life Research, 18, 1263–1278. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014). CPI inflation calculator. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

Clubhouse International. (2013). Clubhouse Profile Questionnaire (CPQ). Retrieved from CPQ database.

Clubhouse International (2014). International directory. Retrieved from http://www.iccd.org/clubhouseDirectory.php.

Clubhouse International. (2015a). About us. Retrieved from http://www.iccd.org/about.html.

Clubhouse International. (2015b). Training base clubhouses. Retrieved form http://www.iccd.org/training_base.html.

Clubhouse International. (2015c). Accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.iccd.org/certification.html.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. doi:10.1177/001316446002000104.

Collett, D. (2003). Modeling survival data in medical research (Vol. 57). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Crittenden, W. F. (2000). Spinning straw into gold: The tenuous strategy, funding, and financial performance linkage. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(Supplement 1), 164–182. doi:10.1177/089976400773746382.

Glickman, M. (1992). The voluntary nature of the clubhouse. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16, 39–40. doi:10.1037/h0095708.

Gorman, J. A. (2012). Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis of employment services offered by the clubhouse model (Master’s Thesis). Retrieved from http://aladinrc.wrlc.org/bitstream/handle/1961/14036/Gorman_american_0008N_10341display.pdf?sequence=1.

Hruschka, D. J., Schwartz, D., John, D. C. S., Picone-Decaro, E., Jenkins, R. A., & Carey, J. W. (2004). Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods, 16, 307–331. doi:10.1177/1525822X04266540.

IBM Corp. Released. (2013). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33, 14–26. Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3700093.

Kaplan, E. L., & Meier, P. (1958). Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 53, 457–481. doi:10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452.

Kleinbaum, D. G., & Klein, M. (2012). Survival analysis (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

Leidy, N. K., & Vernon, M. (2008). Perspectives on patient-reported outcomes: Content validity and qualitative research in a changing clinical trial environment. PharmacoEconomics, 26, 363–370. doi:10.2165/00019053-200826050-00002.

Levin, A. (2012). Clubhouse members check mental illness at the door. Psychiatric News. Retrieved Oct 10, 2012, from http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176%2Fpn.47.10.psychnews_47_10_6-a.

Macias, C., Barreira, P., Alden, M., & Boyd, J. (2001). The ICCD benchmarks for clubhouses: A practical approach to quality improvement in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services, 52, 207–213. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.207.

Macias, C., Harding, C., Alden, M., Geertsen, D., & Barreira, P. (1999). The value of program certification for performance contracting. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 26, 345–360. doi:10.1023/A:1021231217821.

Macias, C., Propst, R. N., Rodican, C., & Boyd, J. (2001). Strategic planning for ICCD clubhouse implementation: Development of the clubhouse research and evaluation screening survey (CRESS). Mental Health Services Research, 3, 155–167.

MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Kay, K., & Milstein, B. (1998). Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods, 10(2), 31–36. Available from http://www.sagepub.com/journals/Journal200810.

Mantel, N. (1966). Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemotherapy Reports. Part 1, 50(3), 163–170.

McKay, C. E., Johnsen, M., & Stein, R. (2005). Employment outcomes in Massachusetts Clubhouses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(1), 25. doi:10.2975/29.2005.25.33.

McKay, C. E., Yates, B. T., & Johnsen, M. (2007). Costs of clubhouses: An international perspective. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34, 62–72. doi:10.1007/s10488-005-0008-0.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83, 340–363. Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2778293.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Mills, M. (2011). Introducing survival and event history analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Mowbray, C. T., Lewandowski, L., Holter, M., & Bybee, D. (2006). The clubhouse as an empowering setting. Health & Social Work, 31, 167–179. doi:10.1093/hsw/31.3.167.

NVivo Qualitative Analysis Software. (2010). (Version 9) [Computer software]. Burlington, MA: QSR International.

Pluye, P., Potvin, L., & Denis, J. L. (2004). Making public health programs last: Conceptualizing sustainability. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27, 121–133. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.01.001.

Rich, J. T., Neely, J. G., Paniello, R. C., Voelker, C. C., Nussenbaum, B., & Wang, E. W. (2010). A practical guide to understanding Kaplan–Meier curves. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 143(3), 331–336. Available from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0194599810007102.

Savaya, R., & Spiro, S. E. (2012). Predictors of sustainability of social programs. American Journal of Evaluation, 33, 26–43. doi:10.1177/1098214011408066.

Scheirer, M. A. (2005). Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. American Journal of Evaluation, 26, 320–347. doi:10.1177/1098214005278752.

Scheirer, M. A., & Dearing, J. W. (2011). An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 101(11), 2059.

Swain, K., Whitley, R., McHugo, G. J., & Drake, R. E. (2010). The sustainability of evidence-based practices in routine mental health agencies. Community Mental Health Journal, 46, 119–129.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). ICCD clubhouse model. Retrieved from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=189.

Wang, Q., Macias, C., & Jackson, R. (1999). First step in the development of a clubhouse fidelity instrument: Content analysis of clubhouse certification reports. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 22, 294–301.

Wholey, J. S., Hatry, H. P., & Newcomer, K. E. (2010). Handbook of practical program evaluation (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wright, R. E. (2000). Survival analysis. In L. G. Grimm & P. R. Yarnold (Eds.), Reading and understanding more multivariate statistics (pp. 363–407). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Yin, R. K., & Quick, S. K. (1979). Changing urban bureaucracies: How new practices become routinized. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathleen Calcerano for her research assistance in the qualitative study, Clubhouse Faculty for their participation in interviews, and all U.S. clubhouses for their contributions to the CPQ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gorman, J.A., McKay, C.E., Yates, B.T. et al. Keeping Clubhouses Open: Toward a Roadmap for Sustainability. Adm Policy Ment Health 45, 81–90 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0766-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0766-x