Abstract

Many barriers to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing among Black people exist. This study analysed the association between race/skin colour and lifetime HIV testing among adolescent men who have sex with men (AMSM) and transgender women (ATGW) in three Brazilian cities. This cross-sectional study was nested within the PrEP1519 cohort, a multicentre study of AMSM and ATGW aged 15–19 years in Belo Horizonte, Salvador, and São Paulo, Brazil. The outcome variable was the lifetime HIV testing (no or yes). The main exposure variable was self-reported race/skin colour as White and a unique Black group (composed of Pardo–mixed colour and Black, according to the Brazilian classification). Descriptive statistics and bivariate and multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to estimate the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) to determine the association between the main exposure and outcome, adjusted for covariates. White adolescents were tested more frequently than the unique Black group (64.0% vs. 53.7%, respectively; Ρ = 0.001). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the unique Black group of AMSM and ATGW had 26% (adjusted OR [aOR], 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55–0.98) and 38% (aOR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.45–0.87) lower odds of being tested for HIV in a lifetime than Whites in model 1 and 2, respectively. Our findings highlight the role of racism in lifetime HIV testing among AMSM and ATGW. Therefore, an urgent need for advances exists in public policies to combat racism in Brazil.

Resumen

Existen numerosas barreras para la realización de las pruebas del virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) entre la población negra. Este estudio analizó la asociación entre la raza/color de piel y haber realizado pruebas de VIH a lo largo de la vida entre hombres adolescentes que tienen sexo con hombres (AHSH) y mujeres transgénero (AMTG) en tres ciudades brasileñas. Este estudio transversal es parte de la cohorte PrEP1519, un estudio multicéntrico de AHSH y AMTG de 15 a 19 años en Belo Horizonte, Salvador y São Paulo, Brasil. La variable de resultado fue haber realizado la prueba del VIH a lo largo de la vida (no o sí). La variable de exposición principal fue la raza/color de piel autoinformada, categorizada como blanca y un grupo negro único (compuesto por color pardo/mixto y negro, según la clasificación brasileña). Se realizaron estadísticas descriptivas y análisis de regresión logística bivariada y multivariada para estimar los odds ratios (OR) ajustados y los intervalos de confianza del 95% (IC del 95%) con el fin de determinar la asociación entre la exposición principal y el resultado, ajustado por covariables. Los adolescentes blancos se hicieron la prueba del VIH con más frecuencia que el grupo negro único (64,0% frente a 53,7%, respectivamente; Ρ = 0,001). El análisis de regresión logística múltiple reveló que el grupo negro único de AHSH y AMTG tenía 26% (OR ajustado [aOR], 0,74; IC 95%, 0,55–0,98) y 38% (aOR, 0,62; IC 95%, 0,45–0,87) menores probabilidades de realizarse la prueba del VIH a lo largo de su vida que los blancos en los modelos 1 y 2, respectivamente. Nuestros hallazgos resaltan la influencia del racismo en la realización de pruebas de VIH a lo largo de la vida entre AHSH y AMTG. Por lo tanto, es urgente avanzar en la implementación de políticas públicas para combatir el racismo en Brasil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic has affected several key populations. In Brazil, these populations include men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW), who have disproportionately higher HIV prevalence rates than the general population [1]. Recently, the incidence of HIV infection in male adolescents has increased in Brazil [2], with studies reporting a high prevalence of HIV infection among adolescent MSM (AMSM) and adolescent TGW (ATGW) [3, 4].

In this context, combination prevention has been adopted as a strategy that includes biomedical, behavioural, and programmatic prevention methods that prioritise a person’s autonomy in different social contexts to prevent HIV [1, 5]. Periodic HIV testing is an important combination of prevention measures as the first step toward timely prevention, diagnosis, and treatment [6].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) reported a reduction in the proportion of people living with HIV who did not know their serological status from 50% in 2013 to 16% in 2020 [7], indicating advances in HIV testing strategies. However, in specific populations, such as MSM and TGW, HIV testing remains a challenge, especially because of stigma and discrimination related to HIV/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), sexual orientation and gender identity, distrust of providers’ secrecy, insufficient social support, lack of knowledge regarding the accuracy of the testing method, and lack of professional training [8, 9]. In addition, sociostructural aspects, such as the social markers of race/skin colour and adolescence, are associated with low HIV testing rates in MSM and TGW [10,11,12].

Regarding HIV testing in Brazil, adolescents have the right to confidentiality according to the bioethical principles of autonomy, justice, beneficence, and non-maleficence guaranteed in the Brazilian Child and Adolescent Statute Low [13]. However, adolescents face barriers to testing because of the uncertain need for parental consent, which is widespread among health professionals [13], and some health units require parental consent [9]. Moreover, adolescents and young people tend to delay HIV testing for fear of rejection in society and the negative opinions of their peers [14].

In 2021, the proportion of reported AIDS cases among homosexual and bisexual Brazilian adolescents aged 13–19 years was 64.1% [1]. Furthermore, the proportion of HIV cases increased from 2012 to 2022 in Black (8.7–12.2%) and Pardo men (i.e., mixed-race people, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística {IBGE}] [15] classification for race) (from 32.7 to 51.7%) and decreased in White men (from 49.4 to 29.4%, respectively) [1]. In 2020, the AIDS mortality rate was higher among Black people [2]. Nonetheless, very few studies exist on HIV testing in AMSM and ATGW populations according to race/skin colour [16].

Health inequalities are unnecessary, avoidable, and determined by how society is structured, including social and economic factors and social determinants of health, making certain people vulnerable [17, 18]. Racism negatively affects morbidity and mortality indicators among Black people and racial inequities in health services [19, 20]. Studies on HIV testing have reported a negative impact of racism on the use of this technology. For example, a study on adolescents and young MSM in South Africa showed that they were afraid of being tested because of discrimination by race in institutions, breaches of confidentiality, and lack of knowledge regarding HIV [21]. Similarly, in the United States of America (USA), young Black MSM who experienced racism and discrimination based on sexual orientation had lower odds of being tested for HIV in their lifetime than those who did not fear being discriminated against [22]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to analyse the association between race/skin colour and lifetime HIV testing among AMSM and ATGW in three Brazilian cities. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that Black adolescents were less likely to have been tested for HIV in their lifetime compared to White adolescents.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the PrEP1519 cohort. The inclusion criteria were ages 15–19 years; self-declared cisgender MSM (reported sex with men in a lifetime) or TGW; substantial risk of HIV infection; and living, studying, or working in Belo Horizonte, Salvador, or São Paulo. Being under the influence of substances that compromised the level of cognition necessary to participate in interviews and appointments at the time of screening was an exclusion criterion [23].

Recruitment and Data Collection

Cohort participants were recruited from lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people (LGBT+) social venues, and online social networks. Participants who visited the clinics in the three study cities were recruited in two arms: PrEP (i.e., those who chose to initiate PrEP and return for quarterly follow-up) and non-PrEP (i.e., those who chose to use other prevention methods) [24]. All participants were offered testing for HIV; hepatitis A, B, and C; syphilis; and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) at the initial and subsequent visits. The participants also answered a sociobehavioural questionnaire administered by the health team, peer educators, or trained researchers.

Study Variables

The outcome variable was ‘lifetime HIV testing’, analysed using the question, ‘Have you ever been tested for HIV before this study?’ (no, yes), and the main exposure variable was the self-reported race/skin colour defined as White and a unique Black group (composed by Pardo – mixed colour – and Black, according to the Brazilian classification). In Brazil, there are five options to self-report as race/skin colour or ethnicity: White, Asian, Indigenous, Black, and Pardo, according to the Brazilian IBGE. Furthermore, researchers, social movements, and activists have considered Black and Pardo together as a unique Black group [15]. For this analysis, other races/ethnicities (i.e., Asian and Indigenous) were excluded because of the small sample size.

The following covariates were classified as socioeconomic, behavioural, and discriminatory based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity. The first variable included the study site (São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, and Salvador), age (15–17 and 18–19 years), study population (cisgender AMSM and ATGW), education (elementary, high school, higher), working (no, yes), person they lived with (alone, with partner or friends, and family), and having private health insurance (no, yes). Behavioural covariates were inconsistent condom use owing to alcohol use (when alcohol intake interfered with condom use), group sex in the previous 3 months, self-declaration as a sex worker, condom use at first sexual intercourse, and anal sex without a condom in the previous 6 months. Furthermore, fathers’ acceptance was related to sexual orientation and/or gender identity (accepts, does not know/ignores, disapproves), experience of discrimination in one’s lifetime (no, yes), and discrimination in health services (no, yes).

Data Analysis

The participants recruited in the PrEP1519 cohort between February 2019 and November 2021 who answered the question about lifetime HIV testing were included in this analysis. First, we performed a descriptive analysis of the overall population characteristics and stratification by race/skin colour, considering two subgroups: a unique Black group and White group. Second, we conducted a descriptive analysis of lifetime HIV testing by race/skin colour considering three categories: Black, Pardo and White for AMSM and for ATGW, which were presented graphically. Third, bivariate analysis of lifetime HIV testing and sociodemographic, behavioural, and discrimination covariables was performed, stratified by race/skin colour, considering two subgroups: a unique Black group and a White group. Statistically significant differences between the proportions of the variables in the race/skin colour strata were analysed using Pearson’s or Fisher’s exact chi-square tests at a significance level of P < 0.05. Subsequently, the variables that presented Ρ < 0.05 in all strata were used in the multiple logistic regression in the Model 1 as an adjusting variable. In addition, the variables that presented Ρ < 0.10 for at least one stratum in bivariate analysis were used to compare the differences between the proportions of odds ratios (ORs) in the unadjusted (i.e., only the outcome and main exposure variable) and adjusted models (i.e., covariates added one by one). Variables with > 10% difference in OR were used as adjustment variables in Model 2. We also estimated the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve area were used to analyse the goodness of fit. The STATA (Statistics Data Analysis) software (version 14.0; StataCorp. 2015; College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis.

Ethical Aspects

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Resolution 466/2012 of Brazilian National Ethics Research Council and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the University of São Paulo (#70798017.3.0000.0065), Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) (#01691718.1.0000.5030), and Federal University of Minas Gerais (#17750313.0.0000.5149) — and by the REC from the WHO (protocol identification: ‘Fiotec-PrEP Adolescent study’). Participants were instructed regarding the study, and those who agreed to participate signed a written informed consent (WIC) form when they were aged ≥ 18 years or an informed written assent (WA) form when they were aged < 18 years. For those aged < 18 years, a different protocol was used in each city, as per the local court decisions: in Belo Horizonte, the WIC had to be signed by the parents or guardian, followed by the WA form signed by the adolescents; in Salvador, there were two possibilities: (i) WIC had to be signed by a parent or guardian and WA by the adolescent; or (ii) just WA had to be signed by the adolescent, in which case the team’s psychologist and social worker judged that their family ties had been broken or that they were at risk of physical, psychological, or moral violence owing to their sexual orientation; in São Paulo a judicial decision allowed a waiver of parental consent, indicating that the WA signed by the adolescents was enough to enable them participate in the study [23].

Results

A total of 1,243 adolescents were included, with a higher proportion self-reported as Black (42.2%), from São Paulo (44.3%), cisgender AMSM (91.6%), aged 18–19 years (78.1%), with high school education (68.0%), not working (55.6%), living with family (82.2%), and without private health insurance (74.1%). Furthermore, 22.9% of the adolescents reported that alcohol use led to inconsistent condom use, 24.6% had group sex, and 5.6% self-declared themselves as sex workers. Most declared not having used a condom during the first sexual intercourse (54.3%) and engaging in anal sex without a condom in the previous 6 months (80.3%). Regarding accepting sexual orientation and/or gender identity, almost half of the participants reported that their fathers did not know or ignored them (58.8%) and their mothers approved (46.0%). Furthermore, 31.7% reported that they had experienced discrimination based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity in their lifetime, and 12.1% in health services (Table 1).

The comparison of the population characteristics by race/skin colour showed that the unique Black group presented statistically significant differences (Ρ < 0.05) related to worse socioeconomics and risk behaviours for HIV infection than the White group, including elementary school education (10.1% vs. 5.2%) and higher education (20.3 vs. 30.8%), not having private health insurance (78.5% vs. 62.8%), and not using a condom at first sexual intercourse (57.2% vs. 47.2%). Moreover, the unique Black group had a higher proportion in the Salvador site (41.0%) than in São Paulo (36.9%) and Belo Horizonte (22.1%) sites (Table 1).

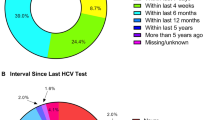

Most participants reported having undergone HIV testing in their lifetime (56.6%), and of these, most reported having undergone the test in the previous 6 months (64.0%). Statistically significant differences were observed between lifetime HIV testing in the unique Black and White groups (53.7% vs. 64.0%, P = 0.001) (Table 2). The disaggregation of the unique Black group into Black and Pardo (i.e., mixed colour) showed that White had a higher lifetime HIV testing rate (63.2%) than Pardo participants (55.8%) and Black participants (51.1%) (P = 0.003) in AMSM (Fig. 1). In addition, Black ATGW showed a higher testing proportion (62.3%) than Pardo (i.e., mixed colour) (56.7%) and lower than White participants (76.2%), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.4) (Fig. 2).

Bivariate analysis stratified by race/skin colour showed that for the unique Black group, lifetime HIV testing was higher among those who lived in São Paulo (60.7%), were aged 18–19 years (56.1%), had reported higher education (62.1%), lived alone (75.0%), self-declared as a sex worker (76.0%), had anal sex without a condom in previous 6 months (56.6%), had father’s disapproval of sexual orientation and/or gender identity (62.6%), and had reported discrimination in health services (66.7%). Among White group, lifetime HIV testing was higher among those who lived in São Paulo (69.4%), were aged 18–19 years (67.6%), had reported higher education (76.4%), were working (71.7%), had private health insurance (73.2%), had group sex (80.7%), self-declared as a sex worker (88.2%), had mother’s approval of sexual orientation and/or gender identity (71.0%), and had reported discrimination in lifetime (72.2%) and in health services (85.0%) owing to sexual orientation and/or gender identity (Table 3).

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the unique Black group of AMSM and ATGW had 26% (adjusted OR [aOR], 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55–0.98) and 38% (aOR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.45–0.87) lower odds of being tested for HIV in a lifetime than Whites in model 1 and 2, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

This study identified racial inequities in lifetime HIV testing in a unique Black group of AMSM and ATGW. Other studies have corroborated these results and shown that Black people, especially the unique Black AMSM and ATGW, are less frequently tested for HIV in their lifetime [10,11,12]. In addition, our study showed a gradual reduction in the rates of HIV testing during the lifetime from White to Pardo and from Pardo to Black. These differences may result from “colourism” in Brazilian society, constituting a hierarchical system among Black people based on their skin tone: the lighter the skin tone (e.g. Pardo), the lower the exposure to racism [25]. Thus, the higher proportion of testing in the Pardo population may be related to their increased phenotypic proximity to White individuals. This phenomenon was not observed in the ATGW subgroup, possibly owing to the small sample size.

Moreover, the current study presented a higher socioeconomic and behavioural vulnerability profile in the unique Black group than in White (e.g., a higher proportion of low education and non-use of condoms during the first sexual intercourse). The social vulnerability of this sample follows the reality of the Brazilian Black population, which has a lower average monthly income and lower access to social rights than the White population [26,27,28]. The Black population also has lower educational levels and more difficulty accessing health services and information [27, 28] and HIV prevention and testing [10, 28, 29].

Lifetime HIV testing was higher in older participants (aged 18–19 years) in both racial/skin colour subgroups, demonstrating the importance of age in testing. Studies in other countries and contexts also showed an association between older age and testing among MSM [30,31,32,33,34] and TGW [31, 32, 35]; however, the age groups in these cited studies are different of our present study. These findings reflect the distancing from health services generally experienced by adolescents, who are often exposed to healthcare permeated by stereotyped, discriminatory, normative, and non-specific views of this phase of life. In addition, a lack of privacy and provision for subjective moral intervention exists [35, 36]. However, our study showed that even older Black participants had a lower lifetime HIV testing rate than older White participants.

In this context, a Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) report stated the need for prevention programs for young people and adolescents, considering the diversity within this group and key populations such as AMSM and ATGW [37, 38]. According to the Brazilian Child and Adolescent Statute Law [39], autonomy and confidentiality in healthcare for adolescents and young people must be preserved, except in situations of risk to their health [39, 40]. The exception included in this Statute Law can only be used sparingly and with extreme care, as it can create several situations of breach of confidentiality. Focus groups with South African adolescents identified distrust regarding the confidentiality of HIV and other STIs screening appointments, fear of loss of autonomy, and a lack of prevention programs for this age group [21, 40]. Hence, autonomy must be encouraged and respected as a form of accountability and exercise of individual rights [33], with education programs focused on adolescent autonomy and the specificities of the Black population.

We also observed specific patterns in lifetime HIV testing based on race/skin colour. Black people with higher school education had fewer lifetime HIV tests than White people with the same characteristics. Caucasian participants had the highest proportion of tests among those who reported father and mother approval, health insurance, and employment. A low education level was associated with low odds of HIV testing in other contexts, especially in the USA. For example, a cross-sectional study of adult Black MSM conducted between 2014 and 2017 showed that the odds of previous HIV testing were higher among those with higher educational levels [41].

Social vulnerability linked to racism reinforces racial inequalities [42]. Racial exclusion negatively influenced the overall health of Black people. In addition, social ascension does not always result in better health conditions [43], showing a more significant positive effect on the health of White people than that of Black people [43]. For example, we found a higher rate of lifetime HIV testing among employed White adolescents than among Blacks (a unique Black group). In this sense, racism hinders testing [44], even among Black people with high economic and social standing.

This study also showed that Black adolescents who reported living with their families had a lower proportion of testing than those who lived alone. Concerns regarding the confidentiality and secrecy of HIV test results [9] may explain this association. Despite the autonomy of adolescents aged 12–17 years, as stated in a document of the Ministry of Health and the Brazilian Child and Adolescent Statute Law [39], the decision to care for this population without the presence of parents or guardians often results in a subjective analysis by health professionals [45, 46]. A qualitative Brazilian study of adolescents aged 13–19 years conducted between 2010 and 2011 identified that adolescents have difficulty in disclosing the test results to their families [9].

Despite the specificities found between Black and White participants, this study showed that race/skin colour was the primary variable associated with lifetime HIV testing when the analyses were adjusted for other covariates. These racial differences may be associated with structural racism, resulting in the dehumanisation and exclusion of Black people to maintain the privileges of the White [26, 29, 47]. Among systematic racism [26], institutional racism [26, 29, 47, 48] increases health-related racial vulnerabilities and inequities for unique Black AMSM and ATGW. This dimension of racism refers to the failure of institutions to provide high-quality services to different citizens regardless of race/colour [29, 47, 49], constituting an essential component of the vulnerability of Black people to HIV [29, 41, 42, 44, 47]. Institutional racism increases socioeconomic and educational inequalities, creating barriers to accessing health services [15, 29, 49, 50], such as HIV testing [8, 22, 46, 49]. Thus, racism against Black people distances them from health services, hindering their access to necessary healthcare [22, 27, 29, 51].

UNAIDS (2022) [37] reports that the Black population is subject to HIV-related racial health inequalities in large countries with irregular income distribution, such as Brazil. Thus, racial inclusion and integrated HIV prevention and care policies, including testing, are necessary for Black populations. Additionally, HIV testing and other combination prevention methods should be expanded, particularly for key and vulnerable populations. The 95-95-95 target for 2030 proposes that 95% of people living with HIV should be tested for their serological status [37]. This goal requires urgent collective efforts against stigma and discrimination with unequivocal respect for human rights, including sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/skin colour, which disproportionately and intensely affect Black AMSM and ATGW.

Investments in public policies for HIV prevention among AMSM and ATGW are necessary, specifically for Black people, to expand testing in this population and reduce the stigma and taboos associated with adolescent healthcare [9, 46]. In addition, media campaigns and messages focusing on this population should highlight various situations [52] and must also represent the Black population to increase the use of HIV testing [51]. The specificities of this population should also be considered when these actions are planned [53], as shown in a previous study on TGW care in São Paulo [54]. Latin America has several examples of enhanced services for minorities, such as LGBT-friendly clinics in Argentina, services adapted for transgender people in Mexico, mobile testing units, and anti-transphobic laws in several countries [54]. Additionally, HIV prevention and testing should be expanded in the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) according to the profiles and specificities of adolescents, considering their sexual vulnerabilities and particularities [51, 52], with options such as self-testing [55, 56], mail testing, and mobile units [57]. For this purpose, we highly recommend health services dedicated to adolescents and the intensification of health activities in schools by health teams, especially those related to sexuality, diversity, and violence.

This study had some limitations. First, the sample was non-probabilistic and may not have represented the AMSM and ATGW populations in the cities included in this study. Most variables were self-reported; therefore, social desirability bias should be considered. Moreover, other forms of structural oppression that may be intersectionally associated with HIV testing have not been considered. Therefore, future studies should analyse the markers of intersectional social differences in HIV diagnosis and prevention. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this study is the most extensive survey on lifetime HIV testing in the AMSM and ATGW groups in Brazil, providing helpful information for planning health programs.

Conclusions

This study observed a lower rate of lifetime HIV testing among Black adolescents, suggesting racial inequalities in the use of this technology in health, determined by institutional racism in health in Brazil. Therefore, an urgent need for advances in public policies to combat racism in Brazil exists. In addition, creating specific lines of care for AMSM and ATGW with respect to autonomy, confidentiality, and secrecy is necessary.

Data Availability

The informed consent process prior to participation ensured confidentiality and anonymity, and only investigators of the PrEP 1519 study were allowed access to the data collected. With these conditions assured, ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Review Committees of the Universidade de São Paulo (protocol number 70798017.3.0000.0065), Universidade Federal da Bahia (protocol number 01691718.1.0000.5030) and Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (protocol number 17750313.0.0000.5149). In the best interest of protecting participants’ confidentiality and anonymity, researchers may contact the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade de São Paulo, (Comissão de Ética para Análise de Projetos de Pesquisa, email: cappesq.adm@hc.fm.usp.br), to make requests related to access to the data used for the analyses in this manuscript. Therefore, the data cannot be shared publicly because of the sensitive content.

References

Ministério da Saúde (BR), Brasil. Secretaria De Vigilância em Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico HIV/AIDS [Internet]. MS; 2022. https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/boletins-epidemiologicos/2022/hiv-aids/boletim_hiv_aids_-2022_internet_31-01-23.pdf/@@download/file/Boletim_HIV_aids_%202022_internet_31.01.23.pdf.

Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria De Vigilância em Saúde. Prevenção combinada do HIV: bases conceituais para profissionais, trabalhadores e gestores da Saúde. [Internet]. Brasil: MS; 2017. https://apsredes.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/prevencao_combinada_-_bases_conceituais_web.pdf.

Kerr L, Kendall C, Guimarães MD, Mota RS, Veras MA, Dourado I, et al. HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Brazil: results of the 2nd national survey using respondent-driven sampling. Medicine. 2018;97:9–15.

Magno L, Medeiros DS, Soares F, Grangeiro A, Caires P, Fonseca T, et al. Factors associated to HIV prevalence among adolescent men who have sex with men in Salvador, Bahia State, Brazil: baseline data from the PrEP1519 cohort. Cad Saúde Pública. 2023;39:e00154021.

Coelho LE, Torres TS, Veloso VG, Grinsztejn B, Jalil EM, Wilson EC, et al. Prevalence of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) and Young MSM in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:3223–37.

Montaner JS, Lima VD, Harrigan PR, Lourenço L, Yip B, Nosyk B, et al. Expansion of HAART coverage is associated with sustained decreases in HIV/AIDS morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission: the HIV Treatment as Prevention experience in a Canadian setting. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87872.

Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Confronting inequalities: lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of aid. [Internet]. Geneva. ; 2021. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2021-global-aids-update_en.pdf.

Cota VL, Cruz MM. Access barriers for men who have sex with men for HIV testing and treatment in Curitiba (PR). Saúde em Debate. 2021;45:393–405.

Taquette SR, Rodrigues AD, Bortolotti LR. Perception of pre-and post-HIV test counseling among patients diagnosed with aids in adolescence HIV test counseling for adolescents. Ciênc saúde Coletiva. 2017;22:23–30.

Mdodo R, Thomas PE, Walker A, Chavez P, Ethridge S, Oraka E, et al. Rapid HIV testing at gay-pride events to reach previously untested MSM: U.S., 2009–2010. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:328–34.

Knox J, Sandfort T, Yi H, Reddy V, Maimane S. Social vulnerability and HIV testing among South African men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:709–13.

Magno L, Pereira M, de Castro CT, Rossi TA, Azevedo LMG, Guimarães NS, et al. HIV testing strategies, types of tests, and uptake by men who have sex with men and transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2023;27:678–707.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Recomendações para a Atenção Integral a Adolescentes e Jovens Vivendo com HIV/Aids / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2013. 116 p. il. SBN 978-85-334-2000-7. Available at: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/recomendacoes_atencao_integral_hiv.pdf.

Urbano AZR. Percepções e práticas de profissionais de saúde no atendimento a adolescentes e jovens gays, homens que fazem sexo com homens, travestis e mulheres transexuais que usam a profilaxia pré-exposição ao hiv (PreP) [master’s thesis]. Santos: Universidade Católica de Santos; 2022.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Política Nacional de Saúde Integral da População Negra. Basília: Ministério da Saúde, 2017, 11p. ISBN 978-85-334-2515-6. Available at: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/politica_nacional_saude_populacao_negra_3d.pdf.

Villela Wilza Vieira and Doreto Daniella Tech. Sobre a experiência sexual dos jovens. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2006;22:2467–72.

Buss PM, Pellegrini Filho A. Iniqüidades em saúde no Brasil, nossa mais grave doença: comentários sobre o documento de referência e os trabalhos da Comissão Nacional sobre Determinantes Sociais da Saúde. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2006;22 (Cad. Saúde Pública, 2006 22(9)):2005–8. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2006000900033.

Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22:429–45.

Camelo LV, Coelho CG, Chor D, Griep RH, Almeida M da, de Giatti CC. L, Racismo e iniquidade racial na autoavaliação de saúde ruim: o papel da mobilidade social intergeracional no Estudo Longitudinal de Saúde do Adulto (ELSA-Brasil). Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2022;38.

Jeremiah R, Taylor B, Castillo A, Garcia V. A qualitative community assessment of racial/ethnic sexual minority young adults: principles for strategies to Motivate Action(s) for realistic tasks (SMART thinking) addressing HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, mental health, and substance abuse. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14:1–10.

MacPhail CL, Pettifor A, Coates T, Rees H. Attitudes toward HIV voluntary counselling and testing for adolescents among South African youth and parents. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35:87–104.

Scott HM, Pollack L, Rebchook GM, Huebner DM, Peterson J, Kegeles SM. Peer social support has been associated with recent HIV testing among young black men who have sex with them. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:913–20.

Dourado I, Magno L, Greco DB, Zucchi EM, Ferraz D, Westin MR, et al. Interdisciplinarity in HIV prevention research: experience of the PrEP1519 study protocol among adolescent MSM and TGW in Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2023;39:e00143221.

Magno L, Soares F, Zucchi EM, Eustórgio M, Grangeiro A, Ferraz D, et al. Reaching out to adolescents at a high risk of HIV infection in Brazil: demand-creation strategies for PrEP and other HIV combination prevention methods. Arch Sex Behav. 2023;52:703–19.

DEVULSKY, Alessandra. Colorismo. São Paulo: Jandaíra, 2021.

ALMEIDA S. Racismo Estrutural. São Paulo: Pólen; 2019.

Neto JA, Fonseca GM, Brum IV, dos Santos JL, Rodrigues TC, Paulino KR, et al. The National Comprehensive Health Policy for the Black Population: implementation, awareness and socioeconomic aspects from the perspective of this ethnic group. Ciênc saúde Coletiva. 2015;20:1909.

Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria De Gestão Estratégica E Participativa. Departamento De Apoio à Gestão Participativa. Política Nacional De Saúde Integral De Lésbicas. Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis E Transexuais / Ministério Da Saúde, Secretaria De Gestão Estratégica E Participativa, Departamento De Apoio à Gestão Participativa. Brasília: 1. ed., 1. Reimp. Ministério da Saúde; 2013.

Werneck J. Racismo institucional e saúde da população negra. Saúde E Sociedade. 2016;25:535–49.

Willard N, Chutuape K, Stines S, Ellen JM. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS interventions. Bridging the gap between individual-level risk for HIV and structural determinants: using root cause analysis in strategic planning. J Prev Interv Community. 2012;40:103–17.

Crowell TA, Nitayaphan S, Sirisopana N, Wansom T, Kitsiripornchai S, Francisco L, et al. Factors associated with testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with other men and women in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Res Ther. 2022;19:25.

Fernandez-Balbuena S, de la Fuente L, Hoyos J, Rosales-Statkus ME, Barrio G, Belza MJ, et al. Highly visible street-based rapid HIV testing: is this an attractive option for a previously untested population? This is a cross-sectional study. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:112–8.

Green K, Vu Ngoc B, Phan Thi Thu H, Vo Hai S, Tran Hung M, Vu Song H et al. AIDS. Is HIV self-testing acceptable in key populations in Vietnam? Results of a cross-sectional study on men who have sex with men, female sex workers, and people who inject drugs. In: 21th International AIDS Conference (2016) Durban, South Africa, 18–22.

Krueger EA, Chiu CJ, Menacho LA, Young SD. HIV testing among Peruvian men who have sex with men on social media: correlates and social context. AIDS Care. 2016;28:1301–5.

Stromdahl S, Hoijer J, Eriksen J. Uptake of peer-led venue-based HIV testing sites in Sweden aimed at men who have sex with men (MSM) and trans-persons: a cross-sectional survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95:575–9.

Salvadori M, Hahn GV. Confidencialidade médica no cuidado ao paciente com HIV/aids. Rev Bioét. 2019;27:153–63.

UNAIDS, In. DANGER: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update, 2022. Geneva: Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, 2022.

Silva AT, Rosa CA, Gagliotti DA. LGBTQIA + fobia institucional na área da saúde. IN: Saúde LGBTQIA+: práticas de cuidado transdisciplinar. Santana de Parnaíba [SP]: Manole. 2021.

Ministério da mulher, família e direitos humanos (BR). Secretaria Nacional dos Direitos Da Criança E do Adolescente. Estatuto Da Criança E do Adolescente. Brasília: Brasil; 2022.

Silva RF, Engstrom EM. Comprehensive health care of teenagers by the Primary Health Care in the Brazilian territory: an integrative review. Volume 24. Saúde, Educação: Interface-Comunicação; 2020.

Matthews DD, Sang JM, Chandler CJ, Bukowski LA, Friedman MR, Eaton LA, et al. Black men who have sex with men and lifetime HIV testing: characterising the reasons and consequences of having never tested for HIV. Prev Sci. 2019;20:1098–102.

Batista LE, Monteiro RB, Medeiros RA. Iniquidades raciais e saúde: o ciclo da política de saúde da população negra. Saúde em Debate. 2013;37:681–90.

Assari S. Race, intergenerational social mobility and stressful life events. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8:86.

Millett GA, Ding H, Marks G, Jeffries IVWL, Bingham T, Lauby J, Murrill C, Flores S, Stueve A. Mistaken assumptions and missed opportunities: correlates of undiagnosed HIV infection among black and latino men who have sex with men. JAIDS. 2011;58:64–71.

da Costa Oliveira A. Participação social nos conselhos de políticas públicas na era Bolsonaro: o caso do Conselho Nacional dos Direitos Da Criança E do Adolescente. Volume 24. Interseções: Revista de Estudos Interdisciplinares; 2022.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Recomendações para a Atenção Integral a Adolescentes e Jovens Vivendo com HIV/Aids / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2013. 116 p. : il. ISBN 978-85-334-2000-7. Available at: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/recomendacoes_atencao_integral_hiv.pdf.

Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:13–24.

Ture K, Hamilton CV. Black power: the politics of liberation in America. Vintage Books; 1967.

Peterson JL, Jones KT. HIV prevention in black men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:976–80.

Guimarães MDC, Magno L, Ceccato M, das GB, Gomes RR, de FM, Leal AF, Knauth DR, et al. HIV/AIDS knowledge among MSM in Brazil: a challenge for public policy. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2019;22:e190005.

Ravenell JE, Whitaker EE, Johnson WE. According to him, there are barriers to healthcare among African American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1153–60.

Carballo-Diéguez A, Balán IC, Dolezal C, Ibitoye M, Pando MA, Marone R, et al. HIV status disclosure among infected men who have sex with men (MSM) in Bueno Aires, Argentina. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25:457–67.

Rocha ABMD, Barros C, Generoso IP, Bastos FI, Veras MA. HIV continuum of care among transgender women and travestis living in São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2020;54:118.

Silva-Santisteban A, Eng S, de la Iglesia G, Falistocco C, Mazin R. HIV prevention among transgender women in Latin America: implementation, gaps, and challenges. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:20799.

Bustamante MJ, Konda KA, Joseph Davey D, León SR, Calvo GM, Salvatierra J, et al. HIV self-testing in Peru: questionable availability, high acceptability, but potentially low linkage to care among men who have sex with men and transgender women. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28:133–7.

Lippman SA, Moran L, Sevelius J, Castillo LS, Ventura A, Treves-Kagan S, Buchbinder S. Acceptability and feasibility of HIV self-testing among transgender women in San Francisco: a mixed methods pilot study. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:928–38.

Manuto T, Hilzman S, Kubeka G, Hoffmann CJ, Mobile. HIV testing in South Africa: maximizing yield through data-guided site selection. Public Health Action. 2021;11(3):155–61.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants who voluntarily collaborated during all phases of this research. We also thank the PrEP1519 Project team at all sites; the non-governmental organisations and public universities involved in the project; the Ministry of Health through the Health Secretariat; and the Department of HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Viral Hepatitis, and STIs.

Funding

This project was funded and supported by the UNITAID (2017-15-FIOTECPrEP). UNITAID aims to increase access to innovative health products and lay the groundwork for expansion across countries and partners. UNITAID is a WHO-hosted partnership.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF acquired the study data, assisted in analysing and interpreting the data, searched the literature, and drafted the manuscript. LM was responsible for data interpretation, provided important comments on data interpretation, drafted parts of the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript. ID, DG, and AG assisted in interpreting the data; helped design, conceptualise, and obtain funding for the PrEP1519 study; coordinated the data collection; and drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Research Involving Human Participants

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Resolution 466/2012 of Brazilian National Ethics Research Council and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the University of São Paulo (#70798017.3.0000.0065), Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) (#01691718.1.0000.5030), and Federal University of Minas Gerais (#17750313.0.0000.5149) — and by the REC from the WHO (protocol identification: ‘Fiotec-PrEP Adolescent study’).

Informed Consent

Participants were instructed regarding the study, and those who agreed to participate signed a written informed consent (WIC) form when they were aged ≥ 18 years or an informed written assent (WA) form when they were aged < 18 years. For those aged < 18 years, a different protocol was used in each city, as per the local court decisions: in Belo Horizonte, the WIC had to be signed by the parents or guardian, followed by the WA form signed by the adolescents; in Salvador, there were two possibilities: (i) WIC had to be signed by a parent or guardian and WA by the adolescent; or (ii) just WA had to be signed by the adolescent, in which case the team’s psychologist and social worker judged that their family ties had been broken or that they were at risk of physical, psychological, or moral violence owing to their sexual orientation; in São Paulo a judicial decision allowed a waiver of parental consent, indicating that the WA signed by the adolescents was enough to enable them participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

França, M., Dourado, I., Grangeiro, A. et al. Racial HIV Testing Inequalities in Adolescent Men who have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Three Brazilian Cities. AIDS Behav 28, 1966–1977 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04297-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04297-z